LOTS OF POSTS IGNORED BY BLOGGER.....

ALL POSTS ARE AVAILABLE ON

|

208. The Fifth Circuit Jumps the Immigration Detention Shark

Late Friday, two of the nation's most right-wing circuit judges adopted an odious legal claim that district court judges from across the country (and ideological spectrum) have overwhelmingly rejected

I’ve written before about the deeply contested (and contestable) reinterpretation of federal immigration law that the Trump administration adopted last summer, under which any non-citizen who was never lawfully admitted to the United States is subject not just to arrest, but to mandatory detention with no opportunity for release on bond for the duration of their removal proceedings.

This argument, which applies even to those who have lived in the United States (lawfully)¹ for decades; even to those who at one point had “Temporary Protected Status”; even to those who have an asylum application pending, is based on the analytically and linguistically flawed claim that such individuals are “arriving aliens” who are “seeking admission” to the United States. (As one district judge put it last August, “someone who enters a movie theater without purchasing a ticket and then proceeds to sit through the first few minutes of a film would not ordinarily then be described as ‘seeking admission’ to the theater.”)

As I explained back in December, the Trump administration’s novel interpretation of a 29-year-old statute that five previous presidents (including Trump) had interpreted differently is not just the putative basis for so much of the controversial behavior in which ICE, CBP, and other federal agencies have been engaged over the last six months; it has been overwhelmingly rejected by federal district judges from across the geographic and ideological spectrum. According to Politico’s Kyle Cheney (who’s done truly exceptional work tracking these cases) reports, “at least 360 judges [have] rejected the expanded detention strategy—in more than 3,000 cases—while just 27 backed it in about 130 cases.” (Yes, this is the same issue that has caused the backlog and mess in the federal district court in Minneapolis in which Chief Judge Schiltz recently accused ICE of violating nearly 100 court orders—all of which ordered the release of individuals the government was purporting to hold under this interpretation—and that led a government lawyer to have a widely noted public breakdown in court last week.)

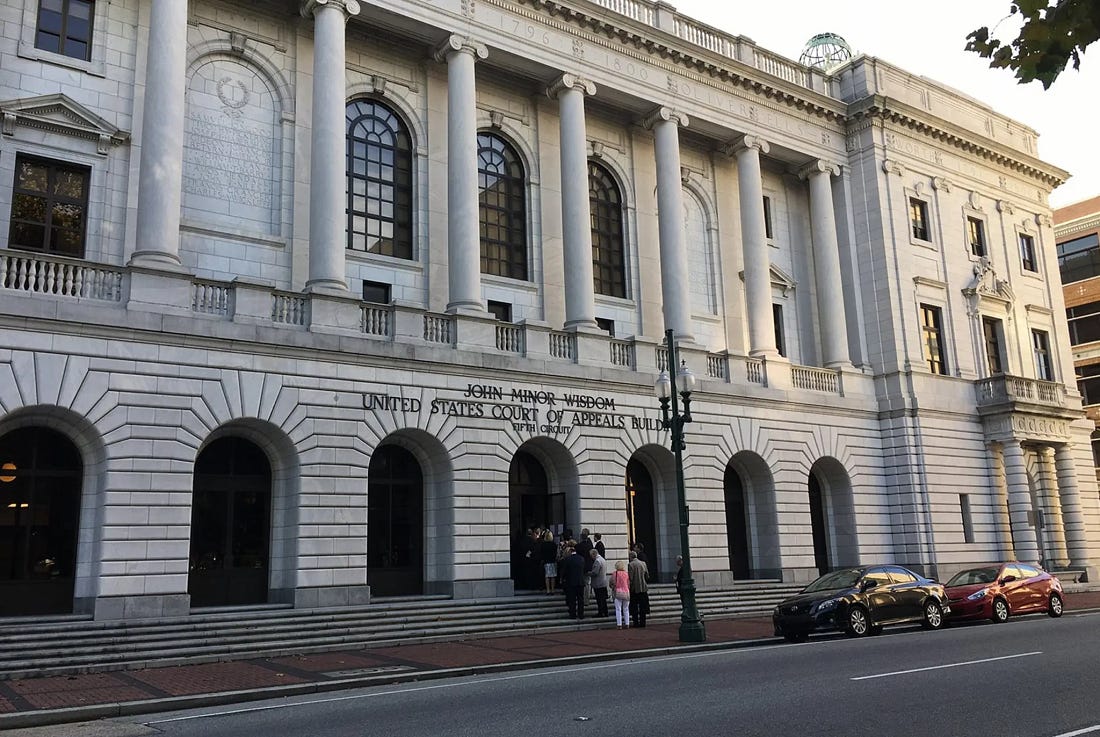

Well, late Friday night, in a ruling handed down just two days after oral argument, a divided panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit adopted the extreme minority view—holding that, yes, the government can indefinitely detain without bond millions of non-citizens who have been here for generations; who have never committed a crime; and who pose neither a risk of flight nor any threat to public safety. The Fifth Circuit’s opinion was written by Judge Edith Jones and joined in full by Judge Kyle Duncan—two of the most reactionary, right-wing federal appellate judges in the country (newsletter readers may recall my November 2024 run-in with Judge Jones; perhaps she’ll add this issue of the newsletter to her folder of my work).

But it’s not just about these two judges; as I’ve suggested before, right-wing litigants have been remarkably successful in steering cases to the New Orleans-based federal appeals court—which has been, at least by the total number of reversals, the court that even this Supreme Court has overruled the most in each of the last two terms, almost always in ideologically charged cases in which the court of appeals ended up (sometimes far) to the justices’ right.

On the substantive legal question these cases present, I don’t have much to add to what I wrote in December; to Judge Douglas’s dissent in the Fifth Circuit; or to the myriad district court opinions that have also rejected the Trump administration’s position, two especially compelling examples of which are this opinion by Judge Dale Ho; and this one by Judge Lewis Kaplan.

Instead, I wanted to write a quick post this morning not to rehash the bavkground and legal arguments (which I covered in detail back in December), but to briefly explain two points that you may not see in a lot of the other coverage of last night’s ruling: How the Trump administration was able to get this nationwide issue before the Fifth Circuit, specifically; and what happens next. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Supreme Court figures prominently in both of these answers.

How Did These Cases End Up in the Fifth Circuit?

Although it’s super-technical, let’s start with the critically important procedural point: The reason why there have been (and have had to be) more than 3000 individual cases challenging the Trump administration’s new mandatory detention policy is because of a pair of Supreme Court decisions—the Court’s 1999 ruling in Reno v. American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (AADC); and last April’s emergency docket ruling in the Alien Enemies Act case, Trump v. J.G.G. In AADC, the Court, in an opinion by Justice Scalia for a 5-3-1 majority, affirmed that part of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA) categorically “prohibits federal courts from granting classwide injunctive relief against the operation of [the immigration detention statutes],” even though “this ban does not extend to individual cases.” (To be fair to the Court, that result may well be what the 1996 statute requires; AADC reversed a Ninth Circuit ruling that had read the statute differently.)

And in J.G.G., a 5-4 majority rejected an attempt by individuals who the Trump administration was seeking to remove under the Alien Enemies Act to challenge their detention and removal through a nationwide class action under the Administrative Procedure Act—holding that they had to proceed through habeas petitions filed in the district(s) in which they were confined. (As Justice Sotomayor pointed out in her dissent, which was joined in these respects not just by Justices Kagan and Jackson, but also by Justice Barrett), this reading was “dubious,” all the more so given the Supreme Court’s 2020 conclusion that challenges to removal orders are not within the historical “core” of habeas corpus protected by the Constitution’s Suspension Clause.)

The upshot is that AADC closed the door to injunctive relief on behalf of a nationwide—or even district-wide—class of litigants in challenges to the government’s application and interpretation of the 1996 immigration detention statutes; and J.G.G. certainly appears to have closed the door to any other nationwide relief under the APA in these cases (like vacatur or a declaratory judgment), channeling all of these cases into individual habeas petitions filed in the district court in which the petitioning immigrant was arrested and/or detained.²

In practice, that meant that, even as it was losing literally thousands of these cases, the Trump administration could cherry-pick which of the losses it wanted to appeal.³ And so instead of appealing the very first batch of losses last summer (when speedy resolution might have provided clarity on the answer to the legal question and, if the administration was wrong, might have thwarted a lot of its subsequent immigration efforts and the burden those efforts have imposed on … everybody), the government waited to appeal until it had lost in courts of appeals in which it wanted to appeal—including the two cases it chose to appeal to the Fifth Circuit. (As Judge Douglas notes in footnote 1 of her dissent, the government also made a series of unusual procedural moves to try to make sure that the Fifth Circuit ruled before any other federal appeals court; Judges Jones and Duncan were, apparently, only too happy to oblige.)

To be clear, the Trump administration’s procedural behavior in these cases didn’t violate any rules, and, frankly, was quite savvy from the perspective of minimizing its chances of losing on appeal. But in my view, that’s exactly the problem. Two of the great advantages of nationwide relief against federal policies are (1) the ability to streamline what might otherwise be thousands of challenges to the same policy when all them turn on the exact same legal question; and (2) a baked-in limitation on the government’s ability to selectively appeal defeats so as to manipulate which appellate courts get the issue first. Those advantages are, and ought to be, especially significant when we’re not just talking about a random federal economic regulation, but rather a policy that has direct implications for whether millions of people can or cannot be held in government custody.

Indeed, this is the exact concern that came up repeatedly during the oral argument last May on the Trump administration’s emergency applications in the birthright citizenship cases—in which Justices Kagan and Jackson, in particular, raised the specter of the government losing over and over again in the district courts, and just not appealing (or only appealing in some circuits) as a way of frustrating, or at least dragging out, effective judicial review. Although nationwide class actions have, to this point, mitigated those concerns in most cases (including the birthright citizenship cases), they’re not available here—again, because of the 1996 statute, AADC, and J.G.G. Immigration lawyers and advocates have been warning about this possibility for decades; Friday night’s Fifth Circuit ruling finally drove that warning home.

What Happens Next?

That leads directly to the second point, which is what happens next. The appellees in these cases, who were released on bond after they won their habeas petitions, have two options: They can petition for rehearing before the full Fifth Circuit, or they can go right to the Supreme Court. For what it’s worth, I think the answer ought to be the latter. (For the very nerdy question of what happens with the Fifth Circuit’s “mandate,” see the footnote at the end of this parenthetical.)⁴

With regard to the full Fifth Circuit, the indispensable Chris Geidner has already done some back-of-the-envelope math on the chances of the full Fifth Circuit rehearing this case. I agree with Chris that the odds are better than one might think at first blush—because, as we saw with the SB4 Texas immigration case in 2024, the “middle” of the Fifth Circuit, although still to the right of the Supreme Court, includes a quartet of George W. Bush appointees who don’t always go along with the judges closer to Jones and Duncan in these kinds of extreme immigration cases. There isn’t much of a margin here, but it’s at least possible to count to nine (the number of active Fifth Circuit judges who’d need to support rehearing for it to succeed). And, as a matter of procedure, as soon as the Fifth Circuit were to agree to rehear the case (assuming those votes can be secured, at least for purposes of rehearing), the panel opinion would be vacated—no matter how long it took the full court of appeals to come to a final decision. From that perspective, there’s an entirely plausible case for pursuing that avenue, first.

But I think one could argue just as strongly for going right to the Supreme Court—and for seeking expedited review there. There’s a reason why district judges from across the ideological spectrum, including plenty of dyed-in-the-wool conservative stalwarts, have rejected the Trump administration’s position in these cases; the best that can be said about these statutes is that they’re a mess, and there are lots of reasons why (1) the better reading is that one who has lived in the United States for a long time is no longer an “arriving alien”; and (2) ambiguities should in any event be resolved in favor of case-specific judicial review, not categorical detention without hearings. Indeed, that was the one point on which all nine justices agreed in J.G.G.

More than that, as last week’s developments in Minneapolis have made abundantly clear, these cases are putting an inordinate strain not just on those directly affected by the Trump administration’s behavior, but on federal district courts and the lawyers litigating them on both sides—especially in jurisdictions in which the federal government has ramped up its “enforcement” efforts. The sooner the Supreme Court resolves this question one way or the other, the sooner those pressures dissipate—all the more so if, as I suspect, there are not five votes on the current Court for the Trump/Jones/Duncan reading of the statute.

But whichever avenue the litigants pursue, here’s hoping they move quickly. As Aaron Reichlin-Melnick from the American Immigration Council noted last night, the Fifth Circuit’s decision will “fuel ICE’s push to transfer people to Texas immediately,” and it will put “even more pressure on plaintiffs and district courts outside the 5th Circuit. Unless the habeas is filed before a person is transferred to the 5th Circuit, a person may remain locked in appalling conditions, never even allowed to ask for bond.” All of that can be traced to another procedural technicality—the principle that a district court gains jurisdiction over a habeas petition if, but only if, it is filed while the petitioner is physically in that court’s jurisdiction. In other words, to avoid being subject to the Fifth Circuit’s decision (while it remains on the books), detainees arrested elsewhere would have to have someone file on their behalf before they’re physically transferred into the Fifth Circuit.

The chaos that’s likely to get even worse in the coming days and weeks will be problematic enough if the Fifth Circuit’s endorsement of the Trump administration’s reinterpretation of 29-year old statutes is ultimately affirmed by the Supreme Court; it will be truly indefensible if, as the overwhelming majority of federal judges to consider the question have concluded since last summer, the government—and, now, the Fifth Circuit—is wrong.

We’ll be back Monday with our regular coverage of the Supreme Court and related developments. If you found this extra issue useful and are not already a subscriber, I sure hope you’ll consider becoming one—and upgrading to a paid subscription if you have the wherewithal:

Stay safe out there.

It is not a crime to be undocumented. Although federal law does criminalize unlawful entry by a non-citizen, it does not criminalize unlawful presence. And, for a host of reasons, there are a large number of non-citizens who entered the country legally, but who lack permanent immigration status (two common examples are individuals who overstayed their visas, or who had a form of temporary protected status that subsequently expired or was rescinded).

Since J.G.G., we’ve still seen district-wide habeas class actions in the Alien Enemies Act cases—because the limitations on class-wide injunctive relief that were at issue in AADC don’t apply to detention and removal under the Alien Enemies Act, specifically (the AEA isn’t listed in 8 U.S.C. § 1252(f)). It’s only in these cases that AADC and J.G.G. overlap.

As I wrote right after J.G.G., “trading APA review for habeas, even if the remedies were otherwise commensurate, is trading the ideologically diverse (and national security-experienced) D.C. federal courts for the most right-leaning federal courts in the country. And the justices know that, too.”

Under Rule 41 of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure and the Fifth Circuit’s local rules, the Fifth Circuit’s “mandate” issues seven days after the time for seeking rehearing en banc has expired, or, if a timely rehearing petition is filed, seven days after that petition is denied. In other words, if the appellees don’t seek rehearing en banc, or if they seek it but don’t get it, the mandate will issue unless they seek a stay of the mandate pending a petition for certiorari to the Supreme Court. I put all of this in a footnote because this detail is of especial relevance only to the two immigrants at issue in these cases, specifically; the precedential effects of the panel opinion in other cases are immediate, and will persist until and unless that ruling is vacated by a grant of rehearing en banc, or vacated or reversed by the Supreme Court.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.