Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Joe Biden will soon sign a criminal justice bill introduced by a member of Congress most famous for saying the Jan. 6 riots resembled a “normal tourist visit.”

The District, lamented Kansas Sen. Roger Marshall, “no longer belongs to the people. The city now belongs to the criminals.” Iowa Sen. Joni Ernst explained that the “sad reality is no one is off-limits to the criminals running rampant in our capital.”

“No one is safe,” Ernst warned.

On Thursday, these arguments won, big. The Senate voted 81–14, with Georgia Sen. Raphael Warnock voting present, to block the D.C. government’s revised criminal code, a years-in-the-making initiative that has been subject to substantial distortion by pundits about what it actually does. The floodgates had opened after President Biden made a surprise announcement that he wouldn’t veto the bill—effectively freeing Congress to squash the product of 16 years of work to reform outdated, confusing, and often arbitrary laws.

[Read about what was actually going to change under D.C.’s revised criminal code.]

This effort by Republicans, who organized to block the code, was a wild success. We are looking at a situation where Joe Biden will soon sign a criminal justice bill introduced in the House by Georgia Rep. Andrew Clyde, who is most famous for having said in 2021 that the Jan. 6 riots resembled a “normal tourist visit.”

How did this get so far?

It’s simple: Democrats’ fear of looking “soft on crime” runs deep.

First it was the House Republicans who wanted to put their Democratic counterparts in a tough spot. To do so, they used a disapproval mechanism under the Home Rule Act that gives Congress a window of time to nullify recently passed laws in D.C. It was a bit of a setup: This scenario would force Democrats to choose between their commitment to D.C. self-government and their fear of being tagged as crime-loving criminals in campaign ads. (There’s been an almost obsessive focus in the media on the revised criminal code’s lowering of maximum penalties on armed carjacking—a serious problem in D.C. these days—even though the “lower” number would be 24 years, which is still substantially longer than the longest carjacking sentences that judges mete out today.)

Thirty-one House Democrats, many of them in vulnerable districts, eschewed looking “soft on crime” and voted for the bill in early February. But Democratic leaders whipped against the measure to make sure it didn’t hit a veto-proof majority. They had reason to believe Biden would veto it, after all. Three days before the vote, the White House released an official Statement of Administration Policy, which stated that Biden opposed the Republican measure. (It did not say, flat-out, that Biden would veto it.)

When the resolution reached the Senate, its passage was likely there, too. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer couldn’t refuse to give it a vote, procedurally, and it wasn’t subject to a 60-vote filibuster. All it needed to pass was all of the Republicans and a couple of Democratic votes from the pool of the many, many Senate Democrats facing difficult reelection fights. But as long as there weren’t 67 votes, Biden’s eventual veto could be sustained.

Then, last week, Biden told Senate Democrats during a weekly lunch that he would not veto it—indeed, he would sign it. The reason he highlighted? Carjackings.

And as soon as Biden made that announcement, Senate Democrats looking for cover rushed to take Biden’s side. (And House Democrats, who are deeply unhappy, wondered where this cover was when they could’ve used it.) Sen. Patty Murray, a liberal representing Washington state who just won a fresh term in 2016, told reporters, “I’ll be voting the same way the president is.” Montana Sen. Jon Tester, who is also quite vulnerable, used the same phrase. Out and out they kept coming. On Monday, the D.C. Council said it would withdraw the crime bill. And on Tuesday, Schumer announced that he, too, would vote to squash D.C.’s criminal code.

“I’m going to vote yes,” Schumer said. “It was a close question, but on balance I’m voting yes.”

A reporter began a follow-up question.

“Next!” Schumer said.

Democrats don’t love to talk about this issue, as Republicans are successfully wielding it to cleave them apart. During Wednesday’s debate, few if any Democrats voting with those Republicans came to defend their position. A few of the Democrats who did vote against the resolution, though, came to defend theirs.

Maryland Sen. Chris Van Hollen noted that the revised D.C. code would have higher maximum sentences for attempted murder, among other crimes, than Republican Leader Mitch McConnell’s own state of Kentucky.

New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker made a similar point, noting that D.C.’s armed carjacking convictions would have “a maximum penalty higher than Georgia, Kansas, North Dakota, Kentucky.”

“Maybe,” Booker added, “we should do a unanimous consent right now saying that Kentucky is too soft on crime, because D.C. wants higher maximum penalties?”

I tried to ask both Booker and Van Hollen after their speeches why their view hadn’t prevailed among so many of their fellow Democrats. Is it just 2024 politics? They didn’t love the question.

“I don’t want to speak to my colleagues’ position on this vote,” Van Hollen told me.

“You guys are focusing on the political analysis,” Booker told me. “I’m focused on the actual law, and I hope more people will start writing about a bill that literally does more to protect police officers, victims of sexual assault, children who are victims of sexual assault. My prayer is that people will start looking at the facts of this bill and not let it be so distorted without very many people writing the truth.”

But did he think his fellow Democratic senators hadn’t been looking at the facts?

“I’m not saying that at all,” he said.

READ MORE  Defend the Atlanta Forest and Stop Cop City protesters march to Weelaunee People's Park from Gresham Park in Atlanta, Saturday, March 4, 2023. (photo: Steve Schaefer)

Defend the Atlanta Forest and Stop Cop City protesters march to Weelaunee People's Park from Gresham Park in Atlanta, Saturday, March 4, 2023. (photo: Steve Schaefer)

The police’s guilt-by-association allegations aren’t designed to get convictions, but to break up a movement.

The protesters are alleged to have participated in acts of vandalism and arson at a Cop City construction site over a mile away from the music festival location and over an hour before the arrest raid took place. They have all been charged under Georgia’s domestic terror statute, though none of the arrest warrants tie any of the defendants directly to any illegal acts.

The probable cause stated in the warrants against the activists is extremely weak. Police cited arrestees having mud on their shoes — in a forest. The warrants alleged they had written a legal support phone number on their arms, as is common during mass protests. And, in a few cases, police alleged protesters were holding shields — hardly proof of illegal activity — which a number of defendants even deny.

This is just the latest incident of law enforcement and prosecutorial overreach against the abolitionist, environmentalist movement in Atlanta, an absurd attempt to establish guilt by association, as the flimsy arrest warrants make clear.

At a hearing for arrestees on Tuesday, 22 activists were denied bond outright. One defendant, a Georgia-based attorney who was arrested while acting as a designated legal observer for the National Lawyers Guild during Sunday’s events, was released on $5,000 bond.

“We haven’t seen a charge for arson or interference with government property,” said Eli Bennett, the attorney for several defendants, describing the arrest warrants during Tuesday’s bond hearing. “The state has no evidence,” he said, adding that Georgia’s domestic terrorism statute is “laughably unconstitutional.”

A total of 42 participants in the Stop Cop City struggle now face state domestic terror charges, as 19 individuals were previously hit with the same charges in the last two months on equally weak grounds. At the end of January, during a multi-agency police raid on the forest encampment, cops shot dead 26-year-old Manuel “Tortuguita” Terán, marking a grim escalation in repression against a movement that has shown impressive resilience in its two years of mobilizing against Cop City.

Now, on the most tenuous claims of vicarious liability, multiple forest defenders face up to 35 years in prison if found guilty of domestic terrorism.

“It’s collective punishment. The police are trying to establish a de-facto norm that anyone who associates with a political movement will be attacked and charged for the actions of any other supporter of that movement,” said Marlon Kautz, an Atlanta-based organizer with the Atlanta Solidarity Fund, which provides bail funds and legal support to protesters targeted for involvement in social movements, including against Cop City.

“As a law enforcement strategy, it’s utterly incompetent and ignorant of how the law works. But as a strategy for repressing a political movement it makes a lot of sense,” Kautz told me. “Convincing activists and prospective activists that they will be held criminally responsible for the actions of other supporters of their movement can have the effect of pitting activists against each other.”

The music festival on Sunday, where the arrests took place, marked the beginning of an ongoing “week of action” organized by forest defenders. In line with the movement’s diverse deployment of tactics over the last two years, its semiregular weeks of action involve peaceful rallies, arts and music events, child-friendly educational and cultural activities in the forest, and Indigenous-led knowledge sharing and prayer, alongside targeted protests and direct actions against Cop City’s supporters and funders.

“Roughly 1,500 people attended over the weekend; to dance, to commune, and to take a stand against Cop City,” organizers of the music festival, the Sonic Defense Committee, told me. “There is no excuse for the police violence that festival attendees were subjected to.”

The week of action brought together locals and supporters from around the country and world to raise awareness of the Atlanta forest’s importance and Cop City’s profound threat — which reaches far beyond the state of Georgia.

The $90 million training center aims to train cops in militarized urban warfare. The Atlanta Police Department told the Atlanta City Council that it intends to recruit 43 percent of the planned facility’s trainees from out-of-state police departments. Numerous multinational corporations, including Coca-Cola and Bank of America, are funding the project.

There’s a certain irony, then, that in statements on Sunday’s arrests, Atlanta police officials have made a point of blaming “outside agitators” for taking up militant action. Out of 44 people originally detained in Sunday’s forest raid, the 11 people released without charge all had Atlanta addresses. Twenty-one of the 23 activists charged with domestic terrorism are from out of state.

Bennett, the defense attorney, noted during Tuesday’s bond hearing that the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, the agency responsible for the domestic terrorism charges, appeared to “split detainees up into local people and out of towners.” He told the court, “The right to freedom of association does not stop at state lines.”

That the fight against Cop City, like the encampments at Standing Rock before it, has drawn supporters from far afield is a testament to its strength and a growing understanding that the anti-racist, environmentalist struggle is a shared, international one. Meanwhile, the tired “outside agitator” trope has long been used to divide social justice movements and was popular among segregationists attempting to discredit historic anti-racist struggles. As Martin Luther King Jr. said, “Never again can we afford to live with the narrow, provincial ‘outside agitator’ idea.”

“Think of the freedom riders,” said Lauren Regan, executive director of the Civil Liberties Defense Center, which is working with numerous Atlanta arrestees. “If people didn’t travel to Southern states from all around the country during the civil rights struggle, this country might have had a very different history,” she told me. “The civil rights struggle impacted the entire country and the world — outside scrutiny, attention, and action forced change. Cop City also impacts everyone. The forced construction sets dangerous precedent on many levels, particularly in the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter uprisings and the national call to focus more on community needs and root causes and less on militarized police who are terrorizing many people in this country.”

Regan called Georgia’s deployment of the “outside agitator” trope “deplorable and ignorant of our history.”

Meanwhile, a diverse, multiracial collective of Atlanta residents have been organizing tirelessly against Cop City since it was first proposed and will continue leading the fight on the ground. Hundreds of people remain in the forest as the “week of action” continues.

“As the movement grows and city and state officials refuse to see the reality of what they are dealing with, their own authority is being brought into question,” noted a statement from the Sonic Defense Committee, released on Wednesday. “If they are not careful, the stakes of the movement will soon exceed the bounds of the forest and Cop City. In fact, that process may already have begun.”

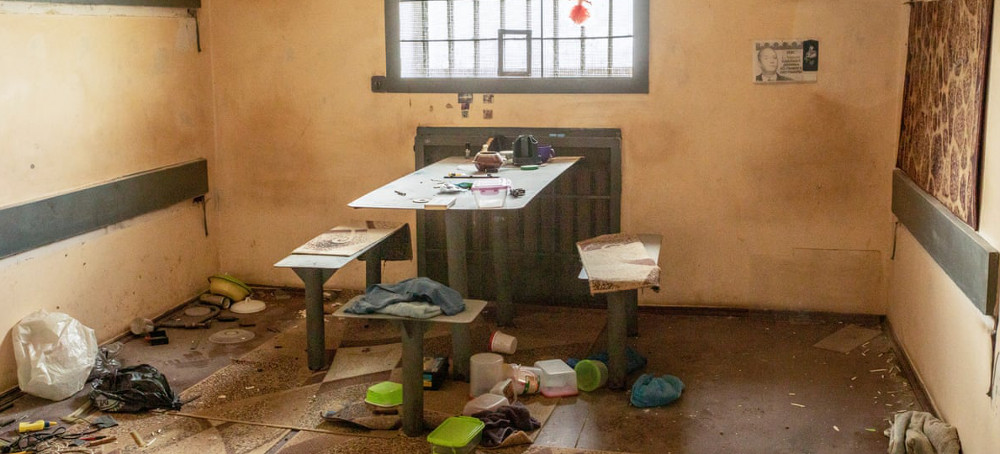

READ MORE  Inside a youth detention facility in Kherson that Ukrainian investigators said was used as a 'torture room' by occupying Russian forces, in November 2022. (photo: Alessio Mamo/The Guardian)

Inside a youth detention facility in Kherson that Ukrainian investigators said was used as a 'torture room' by occupying Russian forces, in November 2022. (photo: Alessio Mamo/The Guardian)

Investigators say sites set up during occupation of Ukrainian city were part of ‘calculated plan to terrorise’ locals

The city was under Russian control for eight months, from 2 March last year until Ukrainian forces entered the city on 11 November.

The lawyers, called the Mobile Justice Team, said on Thursday they had investigated 20 torture chambers in Kherson and concluded they were part of a “calculated plan to terrorise, subjugate and eliminate Ukrainian resistance and destroy Ukrainian identity”.

The evidence collected by Ukrainian prosecutors and analysed by the Mobile Justice Team includes plans used by Vladimir Putin’s occupying forces to establish, manage and finance the 20 torture centres in Kherson.

“The mass torture chambers, financed by the Russian state, are not random but rather part of a carefully thought-out and financed blueprint with a clear objective to eliminate Ukrainian national and cultural identity,” said the British barrister Wayne Jordash, who is leading the team.

More than 1,000 survivors have submitted evidence and more than 400 people have vanished from Kherson, the lawyers say.

The centres were run by the Russian security services, the FSB, as well as the Russian prison service and local collaborators, according to the lawyers, and were designed to subjugate, re-educate or kill Ukrainian civic leaders and ordinary dissenters.

The prisoners included anyone who had a connection to the Ukrainian state or Ukrainian civil society, such as activists, journalists, civil servants and teachers. Other victims said they were stopped randomly on the street and then detained for allegedly having “pro-Ukrainian” material on their phones.

The prisoners – male and female – were subject to physical beatings, electric shock torture and waterboarding. They were forced to learn and recite pro-Russian slogans, poems and songs, say the team.

It is unclear whether the more than 400 people who have disappeared were killed during the occupation or have been taken to Russia.

“Putin’s plan is to occupy Ukraine, subjugate the Ukrainian population to Russian rule and destroy Ukrainian identity. This plan is becoming clearer as the evidence of war crimes proliferates and as our investigations progress,” Jordash said.

He set up the Mobile Justice Team in May to help the Ukrainian prosecutor general’s office investigate and prosecute alleged Russian war criminals. It is funded by the UK Foreign Office, the EU and the US state department and aims to fill a void in Ukraine’s national prosecution service through training and mentorship. Before the invasion, Ukraine had 8,000 prosecutors, but only the war crimes department and two units had expertise in investigating war crimes.

One of the torture facilities that the team examined was in the basement of an office block, and others were repurposed detention facilities, according to the team.

Reporters for the Guardian were among dozens of journalists who saw and heard evidence of torture immediately after the city was freed.

In November, the Guardian visited one juvenile detention centre and spoke to victims who had been kept there. The victims and witnesses who lived around the centre said they never saw the faces of the men who ran the centre as they wore balaclavas, and they dressed head to toe in black.

Three neighbours and two local shopkeepers outside the repurposed juvenile detention centre said they started hearing screams about six weeks after they saw Russian soldiers take over the building. The witnesses said they started to see people being taken in with bags on their heads, and some bodies being removed.

“They only beat me a little, I was lucky, but my cellmates were heavily beaten,” said Zhenia Dremo in November. Dremo described how Russian soldiers “attached one electro-rod to his [cellmate’s] balls and the other to his penis. Then for two hours I would sit there and listen to him scream.”

Another man, Roma, whom the Guardian also interviewed, was accused by the Russians of taking part in underground resistance activities during the occupation. Roma said the Russians attached rods to his testicles but then decided not to switch on the electrical charge.

But he said his cellmates, some of whom were kept in detention for the entire eight months of occupation, were subjected to electric shocks. “There was no life in their eyes, these were broken people,” Roma said.

READ MORE  A Brazilian man claims Santos spearheaded the scheme he was jailed for, threatened his friends, and stole his bail money, Politico reports. (photo: Alex Brandon/AP)

A Brazilian man claims Santos spearheaded the scheme he was jailed for, threatened his friends, and stole his bail money, Politico reports. (photo: Alex Brandon/AP)

A Brazilian man claims Santos spearheaded the scheme he was jailed for, threatened his friends, and stole his bail money, Politico reports.

In a letter, obtained by Politico, Gustavo Ribeiro Trelha describes meeting Santos in 2016 when he rented a spare room in his Florida apartment. At the time, Ribeiro says Santos was going by the name Anthony Devolder. Santos reportedly instructed Trelha on the use of credit card cloning material and flew him to Seattle to begin stealing financial information. “My deal with Santos was 50% for him, 50% for me,” Trelha wrote.

Trelha stated to the FBI that following his 2017 arrest, Santos visited him in jail and instructed him “not to say anything about him,” and threatened his friends in Florida. “I no longer have contact with my friends in Florida because they were all afraid of something happening to them,” he wrote.

In an interview with Politico, Trelha elaborated that he agreed to cover for Santos after the now-congressman threatened to have his friends deported, and instead told authorities that he had been working with Brazil-based accomplices. Santos did in fact appear before Trelha’s judge at his arraignment, and even told the judge his now infamous lie that he was an employee at Goldman Sachs.

Trelha also accused Santos of stealing his bail funds. Before coming to visit Trelha, Santos allegedly took $20,000 in cash from a safe with the promise to help hire him a lawyer (El Chapo’s lawyer, to be specific) and then reportedly ghosted Trelha and their other roommate.

Santos is facing multiple criminal investigations by federal authorities, including a probe into whether he stole thousands of fundraising dollars from a disabled veteran, and a check fraud case stemming from his time living in Brazil.

The Department of Justice is also probing the possibility that Santos may have committed campaign finance violations in the course of his two runs for congress.

Last week, the House Ethics Committee announced that it would establish an investigative subcommittee tasked with determining “whether Representative George Santos may have: engaged in unlawful activity with respect to his 2022 congressional campaign; failed to properly disclose required information on statements filed with the House; violated federal conflict of interest laws in connection with his role in a firm providing fiduciary services; and/or engaged in sexual misconduct towards an individual seeking employment in his congressional office.”

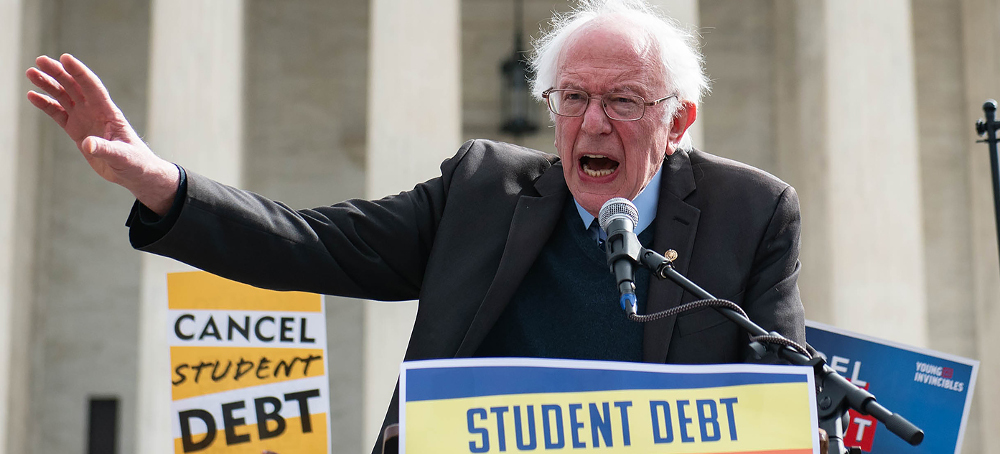

READ MORE  Sen. Bernie Sanders speaks at a Student Debt Cancellation rally in front of the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., on Tuesday, February 28, 2023, as the court hears the Department of Education v. Brown and Biden v. Nebraska in Washington. (photo: Annabelle Gordon)

Sen. Bernie Sanders speaks at a Student Debt Cancellation rally in front of the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., on Tuesday, February 28, 2023, as the court hears the Department of Education v. Brown and Biden v. Nebraska in Washington. (photo: Annabelle Gordon)

The Pay Teachers Act of 2023, co-sponsored by a number of lawmakers including Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Ed Markey (D-Mass.), would provide states with federal funds to establish minimum teacher salaries of at least $60,000 a year. It would also triple the funding of the Title I-A program, which provides funding to schools with a high percentage of students that come from low income backgrounds.

“It is simply unacceptable that, in the richest country in the history of the world, many teachers are having to work two or three extra jobs just to make ends meet,” Sanders said in a statement. “No public school teacher in America should make less than $60,000 a year.”

The bill would also triple funding for rural education programs and prop up programs to diversify the teacher workforce.

The push from Sanders to boost public teacher pay comes after Biden included a call for raises for public educators in his State of the Union address last month.

“Any nation that out-educates is going to out-compete us,” Biden said in the speech. “Let’s give public school teachers a raise.”

Sanders has blasted the pay of public school teachers in the U.S. in the past, and cited rising levels of stress and increasing trends of teachers quitting as the reason why the federal government needed to support them.

The legislative push by Sanders has garnered the support of the National Education Association, the largest labor union in the country.

Lawmakers in the House introduced legislation late last year to increase the minimum wage of teachers in the U.S. to $60,000. The American Teacher Act, sponsored by Reps. Frederica Wilson (D-Fla.) and Jamaal Bowman (D-N.Y.), would encourage states to raise their minimum salaries for teachers through a federal grant program.

READ MORE  Ghassan Abdullah al-Sharbi was held at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, for more than two decades without being put on trial has been released by the U.S. military. (photo: Erin Schaff/The New York Times)

Ghassan Abdullah al-Sharbi was held at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, for more than two decades without being put on trial has been released by the U.S. military. (photo: Erin Schaff/The New York Times)

This week's release of 48-year-old Ghassan Abdullah al-Sharbi to Saudi Arabia — and last month's release of two detainees to Pakistan and one to Belize — indicates that the Biden administration is accelerating its efforts to close Guantánamo, or at least reduce its inmate population to only those facing criminal charges.

Approximately 780 prisoners have passed through Guantánamo's military prison since 2002, and it currently holds 31 men. Of those, 17 have never been charged and are approved for release, but remain behind bars while the U.S. searches for countries to take them. In some cases, they may be repatriated to their native countries. In others, they may be resettled in new ones.

Al-Sharbi had been cleared for release for more than a year, but the U.S. continued to hold him for another 13 months without explanation.

A fluent English speaker with a degree in electrical engineering, al-Sharbi was a "skilled bomb maker" who attended a U.S. flight school, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Arizona, where he "associated with two 9/11 hijackers," according to the Defense Department.

In March 2002 he was captured during a raid of an al-Qaeda guest house in Pakistan and in June 2002 he was sent to Guantánamo, where the military court tried unsuccessfully to prosecute him.

Al-Sharbi remained there in indefinite detention — one of Guantánamo's so-called forever prisoners — for the next 21 years.

In 2016, a parole-like board described al-Sharbi as "mostly non-compliant and hostile with the guards." It also said he "espouses a strong dislike for the U.S." and "has told interrogators that he will re-engage in terrorist activity" if released. Based on that assessment, the U.S. continued to hold him.

But in February 2022, the board determined that al-Sharbi was no longer a significant security threat and could be released with security monitoring and travel restrictions. The board based its decision in part on "the detainee's lack of a leadership or facilitator position in al-Qaeda or the Taliban" and "improved record of compliance in detention."

Al-Sharbi may ultimately be admitted to a Saudi Arabian rehabilitation and deradicalization center for jihadists and Muslim extremists.

Al-Sharbi's transfer to Saudi Arabia suggests that the Biden administration is quietly ramping up its work to find countries willing to accept Guantánamo inmates who have been cleared for release. The State Department office that negotiates those prisoner transfers — a complicated process — was eliminated by the Trump administration, but restored by President Biden.

Guantánamo held 40 prisoners when Biden entered office.

READ MORE  Fishermen drift by the John E. Amos coal-fired power plant operating on the banks of the Kanawha River, Virginia. (photo: Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times)

Fishermen drift by the John E. Amos coal-fired power plant operating on the banks of the Kanawha River, Virginia. (photo: Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times)

That’s why the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) moved on Wednesday to propose the country’s toughest standards yet for controlling this type of pollution.

“Ensuring the health and safety of all people is EPA’s top priority, and this proposed rule represents an ambitious step toward protecting communities from harmful pollution while providing greater certainty for industry,” EPA Administrator Michael S. Regan said in a press release. “EPA’s proposed science-based limits will reduce water contamination from coal-fired power plants and help deliver clean air, clean water, and healthy land for all.”

Regan further told the press that the proposed standards were the “strongest ever,” as E…E News reported.

The proposed rule targets three types of water discharges from coal plants, according to the EPA website:

- Flue gas desulfurization wastewater, which is wastewater generated from the “scrubbers” used to reduce plant air pollution.

- Bottom ash transport water, which comes from plant waste ash.

- Combustion residual leachate, which is the water that seeps out from coal ash landfills.

These wastewaters can also include the pollutants selenium, nickel, iodide, excess nutrients and total dissolved solids. As a class, pollutants from coal plants can also cause cognitive impairment in young children and deformities in animals. They can persist in the environment for several years.

The rule would set zero-discharge standards for both flue gas and bottom ash wastewater, which are the two largest sources of coal plant wastewater, the Environmental Integrity Project told EcoWatch in an email. The newly proposed rule also creates new definitions for wastewaters that may still exist near a plant before stronger regulations came into effect, according to the EPA. All told, the EPA estimates that it will prevent around 584 million pounds of coal-plant water pollution from entering the environment each year.

Currently, the coal power industry is largely operating based on regulations from the 1980s, the Environmental Integrity Project said. Attempts to update the rules have been subject to a political tug-of-war, with the Obama administration proposing tougher standards in 2015 that the Trump administration rolled back in 2020.

The Biden administration has largely returned to the Obama-era rules, but changed the compliance date from 2023 or 2025 to 2029. Overall, the administration estimates that between 69 and 93 plants will need to spend extra money to follow the tougher regulations. The EPA said one plant would likely have to close because of the tougher rule, as CNN reported, but it did not say which.

“The coal industry has benefited from lax pollution controls for decades, and we are pleased that the EPA is finally requiring the industry to stop dumping toxic pollutants into our waterways,” Environmental Integrity Project senior attorney Abel Russ said in a statement emailed to EcoWatch. “This is all required by law and should have happened years ago. The goal of the Clean Water Act is to eliminate water pollution. When the industry has access to technology capable of eliminating pollution, EPA must require the use of that technology.”

The rule will now be open to public comment for 60 days, with a final rule expected in 2024, The Hill reported. Public hearings will be held on April 20 and 25, the EPA said.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611