06 November 22

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

TRUTH: WE CAN FINISH ANY FUNDING-DRIVE IN ONE DAY: Based on the amount of money we need at this point and the the size of our community, we could — easily — finish any fundraising drive in one day. It’s a massive source of frustration.

Marc Ash • Founder, Reader Supported News

Sure, I'll make a donation!

Nate Silver | The Case for a Democratic Surprise on Election Night

Nate Silver, FiveThirtyEight

Excerpt: "If I can put on my concerned citizen hat for a moment, there’s good reason to be worried."

Earlier this week, I spoke with Nathan Redd, a “friend” of mine (actually, a fragment of my alter ego) who attempted to convince me that Republicans will do even better than the FiveThirtyEight forecast suggests. Today, you’ll meet Nathaniel Bleu, another figment of my imagination who I spoke with at a wine bar in Cobble Hill, Brooklyn, where he lives with his husband and two French bulldogs. Bleu, an ad sales executive with a major New York publishing company, expressed confidence that Democrats will win, although as you’ll see his confidence was easily shaken. An abbreviated transcript of our conversation follows.

Bleu: Happy election season, Nate. I’ve never seen everyone so terrified.

Silver: Well, if I can put on my concerned citizen hat for a moment —

Bleu: That looks more like a Detroit Tigers hat.

Silver: Very funny. If I can put on my concerned citizen hat for a moment, there’s good reason to be worried. All those election deniers on the ballot. The attack on Paul Pelosi. I’m not sure where this leads, but it doesn’t seem like it’s a good place.

Bleu: That’s not what I’m talking about. I’ve never seen everyone so terrified to admit that Democrats are going to win.

Silver: Ummmmm —

Bleu: Even you, Nate. You know I have the utmost respect for you and FiveThirtyEight. Why, I’d have a whole menagerie of Fivey Fox plush dolls if I could. But your forecast has Democrats winning and you’re terrified to admit it.

Silver: It very much does not have Democrats winning. Are you reading those fake FiveThirtyEight alerts from the DCCC?

Bleu: The Deluxe forecast has Republicans ahead. But I don’t trust all the subjectivity it introduces —

Silver: For the record, I’m going to object to that characterization of the Deluxe forecast —

Bleu: The Lite forecast has Democrats winning. That’s the one I trust.

Silver: Lite has them barely ahead in the Senate. And Republicans are closing so quickly, that lead might disappear by the time we get to Tuesday. And that’s to say nothing of the House, where Republicans are heavy favorites. Besides, Deluxe is the better, more accurate product.

Bleu: I could almost see the grin on your face when Republicans went ahead in Deluxe the other day. It’s just so much safer for you that way.

Silver: You think of me as risk-averse? You’re the one who still refuses to eat dinner indoors.

Bleu: Not true. Only during that Omicron surge last winter. Was that the last time we saw each other? Besides, it’s a lovely evening.

Silver: I can barely feel my toes.

Bleu: To be fair, it’s not just you. It’s everybody. You and me and everyone in the media. Everybody is terrified of predicting that anything good happens for Democrats, having a replay of 2016 and looking foolish again.

Silver: You don’t work in “the media.” You work in ad sales for a media company. Just because you see David Remnick in the Condé Nast cafeteria doesn’t make you Maggie Haberman.

Bleu: Somebody needs another glass of wine. The truth is, nobody knows how this election is going to turn out. It’s just people groping around trying to sound smart. It’s the supply of takes meeting the demand for takes. And right now, the take everyone wants is “Republicans are going to win.”

Silver: I don’t really buy that at all. Turn on MSNBC, and you’ll see plenty of hopium for Democrats about early voting and turnout and whatever else. People like takes that flatter their sensibilities. But I’m not interested in the psychology of your brunchmates. I’m interested in why you think our forecast might be wrong, and you haven’t said a word about that yet. Besides, I expected you to be on Team Gloom. I thought you’d be apoplectic by this point.

Bleu: I was on Team Gloom. Why, I might as well have been the quarterback. And then I went to Kansas.

Silver: What the hell were you doing in Kansas? I know you and Corey were talking about buying a country home, but that’s a long —

Bleu: Well, Corey grew up in Topeka. So we were out there for “No on 2” — you know, the abortion referendum. We were even doing a little canvassing. I knew that No was going to win, I knew in particular how strongly younger women felt about it. But even I didn’t expect it to win by, what was it, 18 percentage points?

Silver: It was impressive, no doubt. And if Tuesday was some sort of national referendum on Roe, I’m sure Democrats would do pretty well. But —

Bleu: Let me stop you right there. Because it wasn’t just Kansas. There were a bunch of special elections, too. Are you familiar with the website FiveThirtyEight dot com? Here, I’m going to pull my phone out because I bookmarked the page just to make sure I got this right. According to Mr. Nathaniel Rakich — lovely first name, by the way — things changed after Roe was overturned. “Since that decision … Democrats have outperformed their expected margins in [four special House elections] by an average of 9 points.” And that doesn’t even count Alaska! You’re telling me Democrats are going to have a bad year when they’re winning elections in Kansas and Alaska?

Silver: I’m telling you that we’re not in Kansas anymore.

I’m telling you that Democrats’ position has deteriorated since then. You hold this election in August, and yeah, I think Democrats keep the Senate and maybe even the House. But the polls have been pretty clear in showing a Republican rebound.

Bleu: So now we come full circle. Have the polls shifted, or has there been more of a vibe shift? And is the vibe shift real, or is it just an artifact of media coverage? Because I don’t see what’s so different now compared with August.

Nate: Oh boy, this is starting to sound conspiratorial. And there’s a lot that’s changed since August. Bad news on inflation. About a zillion Fox News segments on crime and “defund the police.” And it’s not really even that Democrats are losing ground so much as that Republicans are adding undecided voters— people who were probably going to vote for them all along. It’s all been very normal in some sense.

Bleu: I’m certainly not alleging any conspiracy, or connivance, or cabal. I’m saying that pollsters have incentives, and those incentives run toward giving Republicans the most optimistic numbers they can, because they’ll get a ton of grief if they miss high on Democrats again, but nobody will care if they overestimate Republicans by a point or two.

Silver: Well, a few things here, because this is quite the claim you’re making. Number one, you could have made exactly the same argument in 2020, and yet the polls had an even bigger Democratic bias than in 2016! Number two, I’m not sure the incentives are so obvious, and the clearest incentive is that you just want to be accurate. Number three, I think you’re underestimating the pollsters. Sure, some of them are cynical and partisan, but most of them see what they do as a public service —

Bleu: Why how lovely! Let’s send a fruit basket to the Pew Research Center to thank them for their service! Do you think Trafalgar and Rasmussen care about public service? They’re flooding the zone with partisan polls!

Silver: Actually, they were some of the most accurate pollsters in 2020.

Bleu: I don’t care. A broken clock is right twice a day. You have tons of Republican polls, and no Democratic ones. It’s going to skew the averages.

Silver: I’m not so sure that’s true, at least for FiveThirtyEight. Our model has a house-effects adjustment, so if a pollster consistently shows overly rosy results for Republicans — or for Democrats, for that matter — it takes that into account. And besides, to your point about incentives, it’s a free market. If there’s a firm with a turnout model that shows great results for Democrats, they can publish those numbers if they have confidence in them.

Bleu: I can tell this whole discussion is making you uneasy. You’ve looked uncomfortable all night.

Silver: I’m just a little chilly. Indoors next time?

Look, it’s not a great situation. As America gets more partisan, and trust in institutions erodes, there are a lot of downstream, negative consequences for pollsters. To start with, most people basically don’t answer phone calls from unknown numbers anymore. So people who do answer polls are weird in some sense, and they may not be representative of the electorate. You used to be able to default to more of a gold standard in polling — it was expensive, but you could do it. Now, there are a lot more choices to make. On top of that, trust in the media is about as low as it’s ever been. Does that make pollsters more likely to stick with the herd instead of publishing numbers that could cause them a lot of grief? Maybe, but I’m not going to make too many assumptions about that until Tuesday.

Bleu: So if we can’t trust the polls, maybe we should look at early voting data instead —

Silver: Oh, no no no no no. Let me stop you right there. It’s a trap. There are rarely reliable benchmarks to use, and the analysis inevitably reflects people’s partisan priors. About the only person I trust to any degree at all on early voting is Jon Ralston in Nevada, and he thinks the numbers there look pretty bad for Democrats.

Bleu: Have you agreed with a single thing I’ve had to say, Nate? I could once count on you to defy conventional wisdom. Now you sound just like everybody else. What do you really think?

Silver: My least favorite question! I don’t have some private set of beliefs that I keep to myself! I trust our forecast, which is based on a computer program I wrote four years ago and not my mood as I’m sitting here with a glass of pinot! Our forecast says that the Senate is a toss-up at best for Democrats, and the momentum has been with Republicans. But I’m not sure what we’re really arguing about. I agree that the special elections were good for Democrats. And I very much agree that Democrats could beat their polls. It’s an entirely realistic scenario. But it’s not the likeliest scenario. Besides, the president’s party doing poorly in the midterms would be about the most normal thing imaginable, especially with inflation at 8 percent.

Bleu: You keep using that word “normal,” but we’re not in normal times anymore. This country is going to hell.

Silver: So you’re on Team Gloom after all!

Bleu: Just tell me there’s a chance, a chance that Democrats keep the Senate.

Silver: There’s a 45 percent chance.

Bleu: I’ll take it.

READ MORE

President Volodymyr Zelensky's refusal to talk with Russia's leader, Vladimir Putin, has fueled concern in parts of Europe, Africa and Latin America, where the war’s disruptive effects have been severe. (photo: Heidi Levine/WP)

President Volodymyr Zelensky's refusal to talk with Russia's leader, Vladimir Putin, has fueled concern in parts of Europe, Africa and Latin America, where the war’s disruptive effects have been severe. (photo: Heidi Levine/WP)

US Privately Asks Ukraine to Show It’s Open to Negotiate With Russia

Missy Ryan, John Hudson and Paul Sonne, The Washington Post

Excerpt: "The encouragement is aimed not at pushing Ukraine to the negotiating table, but ensuring it maintains a moral high ground in the eyes of its international backers"

The encouragement is aimed not at pushing Ukraine to the negotiating table, but ensuring it maintains a moral high ground in the eyes of its international backers

The Biden administration is privately encouraging Ukraine’s leaders to signal an openness to negotiate with Russia and drop their public refusal to engage in peace talks unless President Vladimir Putin is removed from power, according to people familiar with the discussions.

The request by American officials is not aimed at pushing Ukraine to the negotiating table, these people said. Rather, they called it a calculated attempt to ensure the government in Kyiv maintains the support of other nations facing constituencies wary of fueling a war for many years to come.

The discussions illustrate how complex the Biden administration’s position on Ukraine has become, as U.S. officials publicly vow to support Kyiv with massive sums of aid “for as long as it takes” while hoping for a resolution to the conflict that over the past eight months has taken a punishing toll on the world economy and triggered fears of nuclear war.

While U.S. officials share their Ukrainian counterparts’ assessment that Putin, for now, isn’t serious about negotiations, they acknowledge that President Volodymyr Zelensky’s ban on talks with him has generated concern in parts of Europe, Africa and Latin America, where the war’s disruptive effects on the availability and cost of food and fuel are felt most sharply.

“Ukraine fatigue is a real thing for some of our partners,” said one U.S. official who, like others interviewed for this report, spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive conversations between Washington and Kyiv.

Serhiy Nikiforov, a spokesman for Zelensky, did not respond to a request for comment.

In the United States, polls show eroding support among Republicans for continuing to finance Ukraine’s military at current levels, suggesting the White House may face resistance following Tuesday’s midterm elections as it seeks to continue a security assistance program that has delivered Ukraine the largest such annual sum since the end of the Cold War.

In a trip to Kyiv on Friday, White House national security adviser Jake Sullivan said the United States supported a just and lasting peace for Ukraine and said U.S. support would continue regardless of domestic politics. “We fully intend to ensure that the resources are there as necessary and that we’ll get votes from both sides of the aisle to make that happen,” he said during a briefing.

Eagerness for a potential resolution to the war has intensified as Ukrainian forces recapture occupied territory, pushing closer to areas prized by Putin. Those begin with Crimea, which Russia illegally annexed in 2014, and include cities along the Azov Sea that now provide him a “land bridge” to the Ukrainian peninsula. Zelensky has vowed to fight for every inch of Ukrainian territory.

Veteran diplomat Alexander Vershbow, who served as U.S. ambassador to Russia and deputy secretary general of NATO, said the United States could not afford to be completely “agnostic” about how and when the war is concluded, given the U.S. interest in ensuring European security and deterring further Kremlin aggression beyond Russia’s borders.

“If the conditions become more propitious for negotiations, I don’t think the administration is going to be passive,” Vershbow said. “But it is ultimately the Ukrainians doing the fighting, so we’ve got to be careful not to second-guess them.”

While Zelensky laid out proposals for a negotiated peace in the weeks following Putin’s Feb. 24 invasion, including Ukrainian neutrality and a return of areas occupied by Russia since that date, Ukrainian officials have hardened their stance in recent months.

In late September, following Putin’s annexation of four additional Ukrainian regions in the east and in the south, Zelensky issued a decree declaring it “impossible” to negotiate with the Russian leader. “We will negotiate with the new president,” he said in a video address.

That shift has been fueled by systematic atrocities in areas under Russian control, including rape and torture, along with regular airstrikes on Kyiv and other cities, and the Kremlin’s annexation decree.

Ukrainians have responded with outrage when foreigners have suggested they yield areas of their country as part of a peace deal, as they did last month when billionaire Elon Musk, who has helped supply Ukraine’s military with satellite communication devices, announced a proposal on Twitter that could allow Russia to cement its control of parts of Ukraine via referendum and give the Kremlin Crimea.

In recent weeks Ukrainian criticism of proposed concessions has grown more pointed, as officials decry “useful idiots” in the West whom they’ve accused of serving Kremlin interests.

“If Russia wins, we will get a period of chaos: flowering of tyranny, wars, genocides, nuclear races,” presidential adviser Mykhailo Podolyak said Friday. “Any ‘concessions’ to Putin today — a deal with the Devil. You won’t like its price.”

Ukrainian officials point out that a 2015 peace deal in the country’s eastern Donbas region — where Moscow backed a separatist campaign — only provided Russia time before Putin launched his full-scale invasion this year. They question why any new peace deal would be different, arguing that the only way Russia will be prevented from returning for further attacks is vanquishing its military on the battlefield.

Russia, facing a poor position on the battlefield, has proposed negotiations but in the past has proved unwilling to accept much other than Ukrainian capitulation.

“Cynically, Russia and its Western supporters are holding out an olive branch. Please do not be fooled: An aggressor cannot be a peacemaker,” Andriy Yermak, head of the Ukrainian presidential administration, wrote in a recent op-ed published by The Washington Post.

Ukrainian officials also question how they can conduct negotiations with Russian leaders who fundamentally believe in Moscow’s right to hegemony over Kyiv.

Putin has continued to undermine the notion of a sovereign and independent Ukraine, including in remarks last month when he once again asserted that Russians and Ukrainians were one people, and argued that Russia could be “the only real and serious guarantor of Ukraine’s statehood, sovereignty and territorial integrity.”

While Western officials also hold profound skepticism of Russia’s aims, they have chafed at Ukraine’s harsh public rebukes as Kyiv remains entirely dependent on Western assistance. Swiping at donors and ruling out talks could hurt Kyiv in the long run, officials say.

The maximalist remarks on both sides have increased global fears of a years-long conflict spanning the life of Russia’s 70-year-old leader, whose grip on power has only tightened in recent years. Already the war has deepened global economic woes, helping to send energy prices soaring for European consumers and causing a surge in commodity prices that worsened hunger in nations including Somalia, Yemen and Afghanistan.

In the United States, rising inflation partially linked to the war has stiffened head winds for President Biden and his party ahead of the Nov. 8 midterms and raised new questions about the future of U.S. security assistance, which has amounted to $18.2 billion since the war began. According to a poll published Nov. 3 by the Wall Street Journal, 48 percent of Republicans said the United States was doing “too much” to support Ukraine, up from 6 percent in March.

Progressives within the Democratic Party are calling for diplomacy to avoid a protracted war, releasing but later retracting a letter calling on Biden to redouble efforts to seek “a realistic framework” for a halt to the fighting.

Speaking in Kyiv, Sullivan said the war could end easily. “Russia chose to start it,” he said. “Russia could choose to end it by ceasing its attack on Ukraine, ceasing its occupation of Ukraine, and that’s precisely what it should do from our perspective.”

The concerns about a longer conflict are particularly salient in nations that were already hesitant to throw their weight behind the U.S.-led coalition in support of Ukraine, either because of ties with Moscow or reluctance to fall in line behind Washington.

South Africa abstained from a recent U.N. vote that condemned Russia’s annexation decrees, saying the world must instead focus on facilitating a cease-fire and political resolution. Brazil’s new president-elect, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, has said Zelensky is as responsible for the war as Putin.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who has tried to maintain good relations with Moscow and Kyiv, offered assistance on peace talks in a call with Zelensky last month. He was spurned by the Ukrainian leader.

Zelensky told him Ukraine would not conduct any negotiations with Putin but said Ukraine was “committed to peaceful settlement through dialogue,” according to a statement released by Zelensky’s office. The statement noted that Russia had deliberately undermined efforts at dialogue.

Despite Ukrainian leaders’ refusal to talk to Putin and their vow to fight to retake all of Ukraine, U.S. officials say they believe that Zelensky would probably endorse negotiations and eventually accept concessions, as he suggested he would early in the war. They believe that Kyiv is attempting to lock in as many military gains as it can before winter sets in, when there might be a window for diplomacy.

Zelensky faces the challenge of appealing both to a domestic constituency that has suffered immensely at the hands of Russian invaders and a foreign audience providing his forces with the weapons they need to fight. To motivate Ukrainians domestically, Zelensky has promoted victory rather than settlement and become a symbol of defiance that has motivated Ukrainian forces on the battlefield.

While members of the Group of Seven industrialized bloc of nations seemingly threw their weight behind a Ukrainian vision of victory last month, endorsing a plan for a “just peace” including potential Russian reparation payments and security guarantees for Ukraine, some of those same countries see a potential turning point if Ukrainian forces approach Crimea.

Reports of a Russian withdrawal from the southern city of Kherson have raised the question of whether Ukrainian forces could eventually march on the strategic peninsula, which U.S. and NATO officials believe Putin views differently than other areas of Ukraine under Russian control, and what a likely all-out fight for Crimea would mean for Kyiv’s backers in the West.

Not only has Crimea been under direct Russian control for longer than areas seized since February, but it has long been the site of a Russian naval base and is home to many retired Russian military personnel.

Illustrating Russia’s elevation of Crimea, the Kremlin responded to an explosion last month on a bridge linking the region to mainland Russia — a symbol of Moscow’s grip of the peninsula — by launching a barrage of missiles on Ukrainian cities, including Kyiv, ending a long period of peace in the capital.

In the meantime, Ukrainian leaders continue to telegraph their intention to pursue total victory, not only to their beleaguered citizens but also to Moscow.

Zelensky told an interviewer on Wednesday that the first thing he would do after Ukraine prevails in the war would be to visit a recaptured Crimea. “I really want to see the sea,” he said.

READ MORE

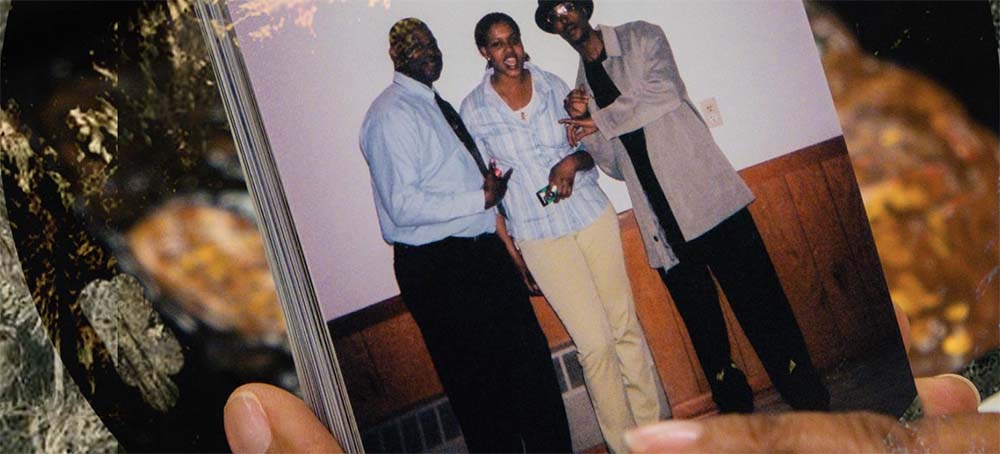

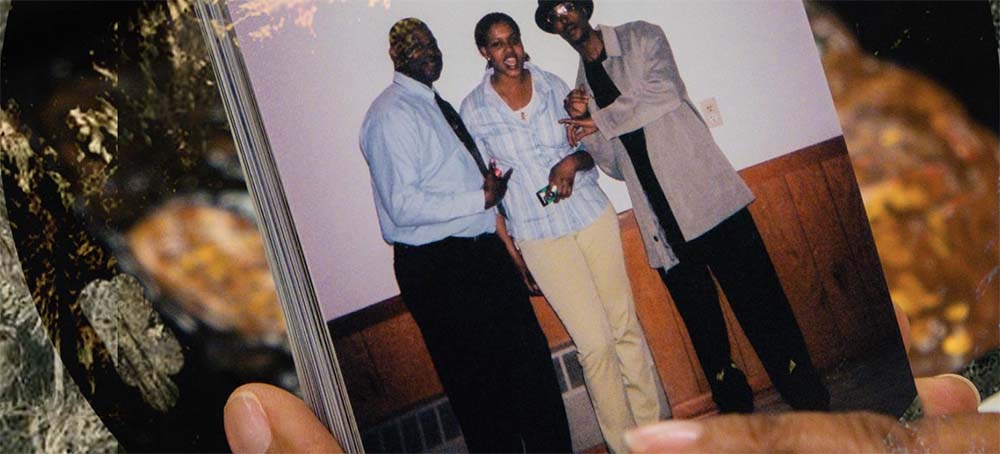

An image of Micheal, left, his sister Jamila, and his brother James. (photo: Malik Rainey/Khaleelah Harris)

An image of Micheal, left, his sister Jamila, and his brother James. (photo: Malik Rainey/Khaleelah Harris)

When Is a Lynching a Lynching?

Jordan Michael Smith, Guardian UK

Smith writes: "A Black man was hanged, then a group of white people burned his body by a US roadside. His family want police and prosecutors to acknowledge race was a factor, but they still deny it."

A Black man was hanged, then a group of white people burned his body by a US roadside. His family want police and prosecutors to acknowledge race was a factor, but they still deny it

It definitely was a lynching. It definitely wasn’t a lynching.

Smoke from the fire surged into the clear sky. Giant gray puffs were spiraling out of the ditch, but discerning their source was impossible from afar in the late-afternoon hours.

Destiny Andersen and her brother were driving on a nearby bridge when they saw it. Destiny, just over 20 years old, walked to the ditch and thought she saw a human body amid the flames. They called their mother, who figured a cow carcass was being burned. They weren’t too concerned but their mother mentioned it in a phone call to Nancy, Destiny’s grandmother.

Nancy knew that in this part of Jasper county, in rural central Iowa, nobody owns cows any more. The partial drought of September 2020 made fires particularly dangerous.

After supper, she and her husband drove the quarter-mile to the bridge. “I took a few minutes looking at it and figured out that it was a human being and not an animal,” she recalls. She hoped it was some twisted practical joke but called 911.

A deputy sheriff arrived at the scene and handed first responders a fire extinguisher. The flames withered. In front of them were the charred remnants of a human body.

Authorities swiftly called the death a homicide. The victim was 44-year-old Michael Williams, who lived in nearby Grinnell.

Days later, law enforcement agencies announced they had arrested and charged a 31-year-old army veteran, Steven Vogel, with murder. Williams had been strangled, according to the medical examiner’s office. Authorities arrested and charged three others with helping Vogel move the body.

The case attracted national attention. Michael Williams was Black, and his body was burned and dumped in an almost-exclusively white part of Iowa. The four people arrested were white. These events occurred 15 weeks after Minneapolis police publicly murdered George Floyd, and massive civil rights protests were under way nationwide.

And yet, law enforcement immediately declared that no evidence suggested the murder had been motivated by racism.

Williams’s family and other members of central Iowa’s Black community weren’t convinced. The simple fact a white man hanged a Black man with a rope and then set him on fire in an easily visible spot – with three other white people helping cover up the murder – was telling.

Data analyzed by the Guardian reveals this to be common: victims’ loved ones clearly see racist motives, while law agencies often don’t.

The life of Michael’s father, James Byrd-Williams Sr, has been punctuated by tragedies steeped in racism. But he knows he’s not alone. “We’re Black people, we know what lynchings are,” he says. “We’re the ones getting lynched.”

People who knew Michael Williams remember his infectious laugh and his fun-loving, loyal personality. His skills in Dungeons and Dragons were legendary, and he was known to break into songs and dances to entertain his co-workers.

He was a loving father and grandfather who went to great lengths to care for his extended family. On the day he died, he had called his cousin to check in – they had talked about his back pain.

He believed in reinventing himself, and he had moved on his own from his native Syracuse to Nebraska when he was about 19 before settling in Iowa in 2008. He talked about going back to school to become a nurse.

But Williams also had his troubles. His diabetes had made working in fast food too painful, so he wasn’t working. He was among the handful of Black people in Grinnell, a town of 9,500 that is more than 90% white. That’s where he met Steve Vogel and Crystal Cavegn, a white couple Williams became friendly with; the three of them sometimes used recreational drugs together.

Vogel lived in the basement of his mother’s home. Records show he had been convicted of numerous crimes over the years, including burglary and assault. Cavegn, 23, was a former fast-food worker with a history of mental illness, according to her Facebook pages. In the preceding few years, she had overdosed, been homeless and gotten arrested for public intoxication and assault.

Both frequently posted on Facebook about their troubled relationship, which began in 2018. They soon got engaged and moved in together, but Vogel repeatedly hinted at being betrayed by Cavegn and he described himself as separated. Nevertheless, he continued to profess his love for her. According to Vogel’s former friend Nathaniel Haines’s later court testimony, Cavegn decided to enter rehab at some point, probably in the summer of 2020. But, according to prosecutors, Vogel was concerned that Cavegn was cheating on him with Williams.

On 12 September, Vogel invited Williams to smoke marijuana at his parents’ house, a mere block from the Grinnell police department. The pair headed towards the basement, which was unfinished and had concrete walls and floors, with some carpet laid out. Near the stairs was a single window covered with a wooden door.

Vogel suddenly hit Williams in the back of a head with a baseball bat repeatedly, according to prosecutors. He then tied a rope around Williams’s neck and threw it around the basement rafters until Williams, begging for his life, stopped moving.

Not long after, Vogel called his friend Cody Johnson to help him move “Black Mike”, as he called him. (Johnson says that Vogel threatened to hurt him if he didn’t cooperate.) They moved Williams’s body from the basement floor to underneath a nearby futon bed. But Johnson says he refused to help any further and left.

Vogel then called on a friend named Nathaniel Haines to join him. They made some pizza rolls and headed to the basement, where Williams lay lifeless on the ground wrapped in plastic in a bed frame under Vogel’s air mattress. Vogel showed Williams’s body to Haines, confessed to killing him, and asked for help in disposing of the corpse. Haines was hesitant, so they ate the rest of the pizza rolls, smoked some wax and passed out. After waking up, Haines left.

Next, Vogel solicited the help of his mother, Julia Cox, and her boyfriend, Roy Garner. They loaded the body into Garner’s green Dodge truck and they drove to the ditch, which is next to a fairly busy country road, surrounded by open fields and farmland. They were seen by a passerby.

One of them poured an accelerant on Williams’s body and set him on fire.

Garner then dropped Vogel off at his sister’s, where he told her he had killed someone. Garner and Cox proceeded to dump supplies – rope, carpet, bleach bottles, rubber gloves and a receipt with Vogel’s name on it – at a rural spot, where they were again spotted by a witness.

The whole process was sloppy – as if they couldn’t imagine getting caught.

“They really took a chance in the middle of the day,” says Nancy Andersen, the grandmother who called 911. Had Vogel and his family just left Williams’s body without setting it on fire, it might never have been found.

Soon, social media was abuzz with rumors concerning Williams’s murder, who had done it, and why. Law enforcement officers interviewed 77 people. Cox and Garner soon confessed to their roles in covering up Vogel’s murder, as did Cody Johnson.

Within a single week, with determination and competence, the more than 50 law enforcement members who worked on the case had opened and closed a brutal murder case.

So it seemed, anyway.

From the outset, authorities rejected a racial motive. “They never pursued it,” says Paula Terrell, Williams’s aunt. “They just kept saying ‘it’s a love triangle.’”

At the press conference held six days after Williams’s body was discovered, law enforcement swiftly stamped out any flickering concerns about racial motives. Adam DeCamp, special agent in charge at the Iowa department of public safety, said that the investigation hadn’t been completed but hastened to declare that race was immaterial to the crime.

Dennis Reilly, Grinnell’s chief of police, spoke next. “This terrible act is not representative of, nor does it reflect upon, the welcoming community that Grinnell is,” he said.

The next day’s headline in the Des Moines Register read, “Four charged in slaying of Grinnell man remembered as gentle, loving; no racial motive seen.”

In fact, Williams’s murder was one of several incidents in central Iowa that targeted Black people in short sequence. Months before Williams was killed, two white men allegedly assaulted 22-year-old DarQuan Jones in Des Moines, breaking bones in his face and wrist as they hurled racial slurs at him. In August 2020, Stephanie Hinton said she was pulled from her car in Des Moines, attacked and robbed by multiple white men hissing racist insults.

After Williams’s death, the Des Moines Black Lives Matter chapter declared a state of emergency in Iowa. The organization suggested Black Iowans travel in parties of two or more; avoid traveling at night; and be prepared to escape, hide or defend themselves in worst-case scenarios.

“Especially in rural Iowa, ‘sundown towns’ are a real thing here,” says the activist Jaylen Cavil, using a term referring to all-white communities that are dangerous for Black people.

Janalee Boldt, Williams’s ex-wife, a white woman with whom he had three children, has no doubt about the nature of the murder. “He was hung – that’s called lynching,” she says.

She noted that the killing happened “over a woman – a white woman”, referring to the history of lynchings involving white mobs that perceived Black men as sexually transgressing.

In Grinnell, she says, her biracial children were sometimes subjected to racism in the virtually all-white town. During the vigil for Williams put on by Grinnell College, someone conspicuously drove by with a Confederate flag.

Boldt thinks that Cavegn left Vogel for several other men before she had her alleged affair with Williams, but that those relationships hadn’t inspired Vogel to murder. “They’re white, and they’re still alive.”

James Byrd-Williams, Michael’s father, was a deputy sheriff in upstate New York for 10 years. That’s one reason he rejects authorities’ claims about his son’s murder resulting from colorblind passions. “They can’t fool me because I know how they investigate stuff,” he says.

At 6ft 8in and with a professional wrestler’s build, he looked imposing when he confronted the man who killed his son and disposed of the body in Jasper county.

He asked the court to record Vogel’s good fortune that he was resisting the urge to jump over the table, leap across the room and snap his son’s killer’s neck.

“I could do it, and nothing in here could stop me,” he said. “That’s a fact.”

Byrd-Williams saw Vogel through the prism of other events in his life. That day in court, he talked about something that happened decades earlier to his relative in a Texas county also named Jasper.

“I had a cousin murdered in Jasper City right there in Texas 22 years ago by two, three white boys,” he told Vogel and the court. “Jasper and Jasper. Two Jaspers in my life. He knew them too, just like you knew my son. But he was torn apart and drug behind a truck, and he was alive when they did that to him.”

While walking home from a family gathering in June 1998, 49-year-old James Byrd Jr took a ride from three white men, one of whom he recognized. Within 30 minutes, the three white supremacists took Byrd to an isolated spot, beat him badly, covered his face with black spray paint, chained his ankles to the back of a pickup truck, and dragged him down a road, decapitating him.

Two family members. Two different states. Both killed by white people.

After the 1998 murder, Texas’s then-governor, George W Bush, opposed a hate crimes law proposed in response, saying the sentences handed to Byrd’s three killers were punishment enough. Two of them were executed, one given life in prison.

Bush’s successor signed a law that strengthened penalties for crimes motivated by bigotry, and in 2009, Congress passed a law named partly for James Byrd that gave the federal government broader abilities to prosecute hate crimes.

In 2017, Dylann Roof, the young white supremacist who was convicted of shooting to death nine Black people in a South Carolina church, became the first person to face the death penalty under the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr Hate Crimes Prevention Act.

The first legislation targeting hate crimes in the US was arguably the Civil Rights Act, passed in 1871 after the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist organizations terrorized Black Americans following the civil war.

Under President Ulysses S Grant the law was used to prosecute and fine Klansmen, but the act’s use declined as Reconstruction was deconstructed. It was an early lesson: legislation is only as good as its enforcement. According to the Equal Justice Initiative, there were more than 4,400 lynchings between Reconstruction and 1950. The Civil Rights Act of 1968 allowed for the prosecution of anyone injuring or intimidating another person based on the victim’s race, color, religion or national origin.

“The classic Tuskegee definition of lynching agreed by anti-lynching activists in 1940 is that a lynching involves an illegal killing by three or more persons in service to ‘justice, race, or tradition’,” says the John Jay College of Criminal Justice historian Michael Pfeifer, the author of several books on the subject. “What is called a hate crime today – language that dates to the 1980s and 90s – was sometimes in earlier eras called a lynching.”

Federal laws subsequently added sexual orientation and gender identity to this list of protected classes, and strengthened penalties for violations. In addition, 46 states and the District of Colombia have their own hate crime laws.

A hate crime can be perpetrated by just one or two people, while lynching was usually understood as a more collective act. But while some lynchings involved hundreds of people, some were done by small mobs.

By these definitions, lynching is alive and well in the US. In March, a white man and a white woman allegedly shot and killed a Black man at a California gas station and have been charged with a hate crime. In February 2020, three white men were captured on video chasing down Ahmaud Arbery in trucks and shooting him to death; all three were found guilty of hate crimes and murder. In Mississippi alone, there have been at least eight lynchings of Black people since 2000, according to one analysis by Julian, a civil rights organization.

Joe Biden recently signed into law an anti-lynching bill, named after Emmett Till, the 14-year-old boy kidnapped and murdered in 1955 in Mississippi for allegedly whistling at or flirting with a white woman.

Iowa’s laws don’t list murder as a hate crime, however. Some activists believe that Till’s murderers would be guilty of a hate crime for assaulting him and violating his civil rights but the murder itself would not count as one. For this reason, there need to be more and better laws on the books.

James Byrd-Williams was cautiously optimistic when Steven Vogel’s trial commenced in November 2021. He knew the evidence was overwhelming.

The county attorney, Bart Klaver, outlined a simple case: Vogel was dating Cavegn and “began getting concerned that Michael Williams was interfering with that relationship, and it bothered him”, he said. This approach focused on the crime itself and sidestepped any discussions of racism that might have made an all-white jury uncomfortable.

Klaver called Steven’s sister to the stand, as well as Cody Johnson, the friend who moved Williams’s body across the room of Vogel’s basement, and Nathan Haines, the friend who Vogel also asked for help. All three said that Vogel had confessed to them.

Vogel’s lawyers argued that Vogel killed Williams spontaneously, perhaps in self-defense, rather than with foresight. They didn’t call a single witness, and he never took the stand.

After less than four hours, the jury found Vogel guilty on all counts. The judge sentenced him to a life sentence without chance of parole.

After pleading guilty for their parts in the crimes, his mother, Julia Cox, was sentenced to seven years in prison, and her partner, Roy Garner, to nine. Cody Johnson pleaded guilty to accessory after the fact and was sentenced to two years in prison after a judge rejected an earlier plea deal that had allowed him to avoid jail time.

For the Williams family, a sense of unfairness prevails. They say authorities neglected them during parts of the investigation, some court proceedings and Cody’s plea deals.

Paula Tyrell, Michael’s aunt, is particularly troubled that the eyewitness who spotted Garner’s truck testified in court that she saw a second silver truck carrying a fourth person, but only three people were charged with disposing of the body at the spot. The identity of the silver truck’s owner is a mystery. (Capt Dan Johnson of the Grinnell police department referred questions concerning the case to prosecutors, who didn’t respond to the Guardian’s requests for comments.)

Tyrell is also disturbed that authorities didn’t initially inform her family that Capt Johnson is Cody Johnson’s cousin. “He is the lead detective and he did not recuse himself from a case involving a family member,” she said in an email. Capt Johnson told the Guardian that he wasn’t involved in investigating Cody, but he testified in court that he was “co-lead investigator” in the Williams case.

More broadly, Williams’s family, and other members of Iowa’s Black community, argue that partial justice is no justice at all.

When officials decline to file hate crimes charges in appropriate cases, they mislead and endanger communities, says Luana Nelson-Brown, executive director of the Iowa Coalition for Collective Change. “If we don’t talk about the racial implications in a crime, we don’t give the community a chance to employ their own safety mechanisms,” she says.

Immediately after Vogel’s conviction, Scott Brown, assistant Iowa attorney general, told reporters the evidence suggested that Williams was killed over Cavegn (he didn’t respond to numerous requests for comment).

Special Agent DeCamp told the Guardian, “that’s still my belief based on the information as I know it.”

But Byrd-Williams argues that the particular disrespect that Vogel showed to Williams, by hanging him with a rope and burning him in a noticeable area, illustrated a race-based hatred. He is pushing for Iowa to stiffen its hate crime penalties – and he wants the legislation named after his son. He also wants the federal government to bring hate crime charges.

“I want his name to always be remembered in Grinnell, that he was murdered and his body was destroyed and burned in a ditch,” he says.

For Byrd-Williams, Michael’s murder compounds the pain of his cousin James Byrd’s killing.

And then there was Terry Maddox. He was another of Byrd-Williams’s sons, and Michael’s half-brother.

“He was shot in the back by a Syracuse police officer,” Byrd-Williams says.

In 2016, Maddox was attending a party in central New York when someone complained to authorities about the noise. Police and the district attorney said Maddox, 41, was firing a gun when Kelsey Francemone, a 22-year-old rookie white police officer, arrived at the party and ordered him to put it down. Maddox instead turned toward Francemone and kept firing, she later said. She returned fire and killed him.

Officials said the shooting was justified and Maddox had gun residue on his hands. No gun was ever found, however. A grand jury declined to press charges against Francemone, whose actions were lauded by state and county authorities. Seven individuals pleaded guilty to rioting, but six others charged with similar crimes decided to go to trial. All were acquitted.

The next year, Kathy Hochul, now the New York governor, honored Francemone as the state’s officer of the year.

Byrd-Williams feels differently. “My son was murdered,” he says.

Maddox left behind five children and a pregnant fiancee. He died 18 years after James Byrd and four years before Michael Williams.

Three family members. Three different states. All killed by white people.

If confirmed as a hate crime, Michael Williams’s murder would count as one of the nearly 2,900 anti-Black incidents reported in the US in 2020, a 49% increase over the year prior.

Virtually all experts believe this drastically understates the number of hate crimes, as the Guardian’s analysis shows.

“Is the hate crime data underreported? Absolutely,” says Michael Lieberman, a lawyer at the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC).

Although the FBI collects data on hate crimes, cities and police departments are not mandated to hand over any information about these crimes. Consequently, most local law enforcement agencies – about 80% – declined to share any information about hate crimes with the FBI in 2020, according to justice department numbers. And those that participated weren’t always thorough: many cities reported not a single hate crime, according to the SPLC.

“If you live in a big city where they haven’t reported a [hate] crime in a few years,” Lieberman says, “why would you call the police and report it? You have no expectation they’re either ready, willing or able to do anything about it.”

Even worse, of the approximately 200,000 incidents a year reported in the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ National Crime Victimization Survey, US attorneys investigated fewer than 0.1%. Those rarely lead to prosecutions, which is why just 0.001% of the hate crimes Americans say they experience annually are prosecuted, according to the Guardian’s analysis of federal data.

The justice department’s own data show that it declined to prosecute an astounding 82% of hate crimes investigated between 2005 and 2019.

In May 2021, the attorney general, Merrick Garland, announced steps the department would take to improve its record. Prosecutors and other officials regularly cite the difficulty of convincing judges and juries that incidents are motivated by bigotry. Some experts say that proving a motive of hatred is difficult.

But prosecutors are hesitant because they are risk-averse, says former federal prosecutor Shanlon Wu. “They want slam-dunk cases,” he says. But in reality, proving hate is no harder than proving other criminal intent. Instead, refraining from bringing such cases means prosecutors fail to develop skills to persuade juries. “It’s sort of a self-fulfilling prophecy,” he says.

Williams’s father was dismayed that prosecutors refused to charge Vogel with hate crimes.

Here is his truth: the decision to forgo hate crime charges in Michael’s case is only the latest example of the bigotry that has imposed itself on his world. It’s a form of racism he believes will never be absent from this life.

“The law is not made for Black people,” Byrd-Williams says.

American racism has disfigured Byrd-Williams’s life too forcefully for him to trust it can ever be eradicated. But he believes robust and well-enforced hate crimes laws can honor the victims of hatred. For that to happen, however, authorities must stop insisting certain actions are colorblind when traces of color are present.

Men like Byrd-Williams know that where there’s smoke, there’s usually fire – and sometimes, in that fire, lies a man killed for being Black.

READ MORE

Chris Carver sits for a photo at Compassionate Addiction Treatment in Spokane, Washington. (photo: Guardian UK)

Chris Carver sits for a photo at Compassionate Addiction Treatment in Spokane, Washington. (photo: Guardian UK)

Why Unhoused People in the US Are Choosing to Go to Jail: 'I Kept Reoffending'

Wilson Criscione, Guardian UK and InvestigateWest

Criscione writes: "People on the street who are resistant to shelters face a cruel choice: living rough in the cold or spending time behind bars."

People on the street who are resistant to shelters face a cruel choice: living rough in the cold or spending time behind bars

Chris Carver waits in the courtroom for two hours before his name is called. Spokane municipal judge Mary Logan tells him to stand: “We’re dealing with your case now.” He struggles to his feet. His beard is shabby. Branch-like tattoos wind around his eyes. He flashes a boyish grin through weary eyes.

Judge Logan faces him from the bench, an American flag draped behind her: “So, Mr Carver, you want to waive your right to have an attorney represent you?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“So that is your right, Mr Carver, to do that,” the judge says. “I always wonder why, when you … qualify to have counsel assigned at no expense to you–”

Carver interrupts: “Because it’s a maximum penalty of a year in jail, and that ain’t nothing to me, ma’am.”

“I’m sorry, what?” the judge asks.

Carver continues: “I’m homeless, out there on the streets and everything. A year is nothing to me … I don’t know what else to do.”

The judge presses: “I would hate for you to think that jail is your home away from home.”

Carver shrugs: “I’m homeless out there, so … ”

It was early February of a particularly cold winter in Spokane, in eastern Washington state, when Chris Carver decided he would rather go to jail than ride out the next couple of months on the streets. The charges against him were serious enough: criminal trespass, defecating in a church stairwell, malicious mischief for throwing a skateboard at a car that drove through the alley where he was sleeping. A public defender probably could have helped him avoid extended jail time.

But Carver’s choice – purposefully, knowingly torpedoing his chance at freedom – fails to shock those who regularly work with the chronically homeless. They say they have seen it many, many times. Only occasionally does it make the news. In January 2021, an Indiana man refused to leave a hospital until police booked him. In Mississippi, right before Christmas in 2019, a homeless man broke windows so he could spend the night in jail. And in 2018, a Washington man robbed his fourth bank in search of a long prison sentence.

Still, even assuming these are outlier cases in the spectrum of homelessness, people like Carver represent an urgent policy challenge increasingly facing communities across the country: how do cities deal with shelter-resistant, street-hardened people, the ones often demonized by politicians as living proof that US cities are dying?

No one believes that employing jails as temporary housing is smart or humane; nor does it make economic sense, as it is more expensive than other options. The fact that it is happening at all proves that something has gone horribly wrong, housing advocates say.

“It’s a national climate that has deprioritized housing, and it’s created incredibly cruel choices for folks who are experiencing any form of instability,” says Marc Dones, head of the King County Regional Homelessness Authority in Seattle.

It’s not just unfolding in places like Seattle and San Francisco. It is now an issue confronting small and mid-size cities like Spokane (pop. 220,000), a place that had long been marketed – until recently – as an affordable city to raise a family. That is no longer the case. Housing prices have soared by 60% in the last two years, and the community is divided over how to manage the sudden appearance of unhoused people occupying corners of its small, revitalized downtown.

The left-leaning city council has pushed for more shelter space and housing that doesn’t require sobriety or treatment. Meanwhile, the city’s mayor, Nadine Woodward, a former local TV anchor and conservative, narrowly won office in 2019 after a tough-on-homeless campaign, in which she was critical of policies that she perceived as giving the unhoused handouts with no accountability, pushing against merely “warehousing people and handing out sandwiches”.

And then there is Carver, who lives the homelessness-to-jail cycle. He boasts that he is the “second-longest-homeless man in Spokane”, having survived on these streets for 25 years. He’s been constantly ticketed, arrested and jailed. Many of his claims are impossible to verify. But records show 16 convictions in Spokane alone; since his 18th birthday, he has been charged with 43 crimes here and elsewhere. Most were non-violent offenses: possession of marijuana, theft, panhandling. A few were for more violent crimes, like misdemeanor battery and fourth-degree assault. In 1999, he was sentenced to three months in jail for a misdemeanor charge of assaulting law enforcement personnel in Idaho. He spent a year in jail for a 2007 felony charge of riot with a deadly weapon.

Clearly, jail is not a deterrent in his case. And while the societal tussle over homelessness drones on, Carver and those like him get by any way they can – huddled under bridges, camped on sidewalks or, increasingly, locked behind bars.

I first meet Carver last March, about a month after that day in Logan’s courtroom. He’s walking along the sidewalk in front of a gas station. He wears tan, insulated bib overalls and a coat stuffed with blankets. He lists to one side, the result of a debilitating leg injury. He collapses as I approach and then needs help to get back up.

I introduce myself and explain that I heard about him from Judge Logan. (I would later listen to audio of the court hearing.) Carver and I make our way to a warm place to talk – a local recovery center where he can get free food. He scoops peanut butter from a jar with a plastic spoon.

With food and warmth, he becomes talkative and grins: that February day in the courtroom, in which he accepted a month behind bars on top of the one he had already served, was far from the first time he sabotaged his own case. Jail, Carver tells me, is a logical choice during freezing winter months. When I ask him about shelters, he says he hates being crowded in with other people and doesn’t feel safe there. Social service workers say that is a common complaint among those experiencing homelessness.

As we talk, Carver speaks casually about his criminal record, taking pride in the fact that most cops know him by his first name. But he says he wants to live his street life unbothered; police prevent him from doing that.

“I’m on one side”, he says, “and they’re on the other.”

He admits that life on the streets is lonely. Family? He says he hasn’t seen them in 30 years: “I wouldn’t even recognize them.”

Then he offers an explanation for his solitary life: he suffers from bipolar disorder, a mental health condition that causes extreme mood swings. And it’s so bad, he says, that he will black out only to realize he has left someone lying in a pool of blood. He claims to have killed people like this, and says the state of Idaho once “tried to put him away for life” before it was determined he acted in self-defense.

Jail works, he says. He gets reliable meals and a cell to himself, and is at no risk of hurting anyone else.

What about stable housing? A job?

Carver says there was a time when things were coming together. Five years ago, a pastor in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho – a 40-minute drive east from Spokane – helped Carver get a job at a steel beam factory and an apartment. Then one day he was hit by a car driven by a teenager being chased by police. Carver was hospitalized for months and has been homeless again ever since.

At least that’s the story he tells. Later, I discover that these stories – killing people, never seeing his family, being hit by a car during a police chase – are almost entirely untrue. It’s a persona he has built to explain his circumstances to judges and service providers who wonder why he is on the streets, and why he willingly gives up his freedom for a warm bed.

The story of a man voluntarily surrendering his own freedom to get off the streets is nothing new to Dones, the head of the King County Regional Homelessness Authority in Seattle. It’s just another illustration of how this country fails to help the most vulnerable, street-hardened among us.

“I’ve heard this story many, many, many times,” Dones says. “I’m not aware of any academic paper on it. But those of us who work in housing and homelessness and public health know about it.”

The research that does exist on the issue comes from the UK. In 2010, a Sheffield Hallam University survey of 400 people living on the streets found that 30% had committed a minor crime with the intention of being taken into custody for the night. In 2020, a UK-funded watchdog – originally intending to study recidivism among those released into homelessness – discovered that many of the homeless people who were arrested voluntarily went back to jail.

“I kept reoffending to get put back inside as I couldn’t get accommodation,” one man quoted in the report said.

It’s not hard to find examples of people committing crimes just to get into jail.

Last Halloween, a homeless man in Longview, Washington, went vehicle prowling, trying to get police to throw him in jail. When they took him to a shelter instead, he left and committed a more serious crime: stealing a gun from a car. When police arrested him, he seemed relieved and told officers, “I’ve been trying to go to jail” to get warm, according to a police report obtained by InvestigateWest. He has been there ever since on charges of vehicle prowling and theft of a firearm.

“It happens more than people admit it’s happening,” says Longview police captain Branden McNew. “We as police are familiar with that phenomenon.”

The longer someone is out on the streets, the more likely they are to end up in jail, whether they choose to or not.

In Seattle, for example, homeless people before the pandemic made up an estimated 1% of the city’s population but nearly 20% of its jail bookings, mostly for non-violent crimes. National research from the Prison Policy Initiative shows that a person with a criminal history is up to 10 times more likely to experience homelessness than a member of the general public is. Being unsheltered, too, increases contacts with the police and the chances of being jailed.

That is due in part to city policies that make basic acts of living on the street illegal: lying on a sidewalk, loitering, panhandling. Cities justify laws criminalizing homelessness by adding shelter space, arguing that anyone can choose to be off the streets and in shelter if they want.

But shelter beds seldom keep pace with need. And some people, like Carver, avoid shelters even when they are available. They say they feel unsafe and uncomfortable in the shelters, or they impose rules they can’t follow. During the Covid pandemic, sharing air space with that many other people became even more dangerous.

Homeless reform advocates say that understanding how often a person chooses jail is less important than understanding why it happens. In a basic sense, it isn’t a hard question to answer.

“Have you tried sleeping outside with nothing?” says Dones, the King county homelessness official. “It’s very possible to lose your extremities during a spring night outside, let alone a winter night.”

Truly understanding why someone would choose jail, however, means understanding how they arrived at that choice to begin with. That conversation, Dones says, must start with the recognition that the country is in a housing crisis that has priced people out of stable homes and forced them on to the streets.

“Homelessness is a housing problem,” Dones says. “It is not a problem of criminality or substance use or behavioral health.”

McNew, the Longview police captain, has mixed feelings about granting someone’s wish to be jailed. “You can’t arrest your way out of the homeless issue,” he says. Arresting the unhoused only serves to “perpetuate the behaviors by criminalizing these poor people”.

Yet sometimes, a homeless person commits a crime so serious that it cannot be ignored.

McNew was a detective four years ago when a call crackled over the police radio: a bank robbery was in progress just a half block away from the police station in Longview, a city of 37,000 tucked along the Columbia River in south-west Washington.

McNew rushed over prepared for the worst – hostages, gunshots, a chase. Instead, he found a 68-year-old man, bald and wearing thick glasses, waiting outside the bank. His name was Richard Gorton.

“It was so immediately apparent there was something unusual about it,” McNew says.

Gorton wanted to be arrested. And, as McNew quickly learned, he had robbed three banks in Bellingham, Washington, about 200 miles to the north, a few years earlier, all in hopes of going to prison. Each time, Gorton was calm, offering himself up to police willingly.

Today, Gorton is at the Stafford Creek corrections center in Aberdeen, where he’s serving a seven-year sentence for the 2018 robbery in Longview. He tells me he robbed the first bank in Bellingham back in 2014 because he thought he was going to lose his apartment at a public housing complex, which he paid for using money from social security. He was sentenced to three months behind bars and ordered into transitional housing. But as a convicted felon, it became harder to secure permanent housing. So he robbed another bank, then another – until he got three years in prison.

After the third robbery, he tried life on the streets. He sought help at the Union Gospel Mission in Spokane, but he couldn’t comply with the religious requirements. The same thing happened in Portland. So, just 10 days after his release from prison, he went to Longview to rob a bank again – this time getting the longer prison sentence he was seeking.

He says he feels bad about all of this. Not because he put any burden on the criminal justice system – that’s something he hadn’t considered – but because he was told that the last bank teller he robbed was distraught over the situation.

“I’ve come to be aware that hurt people often turn around and hurt other people,” Gorton says. “So this bank teller, who knows what road she goes down?”

Gorton grew up an only child in Golden, Colorado, in an upper-middle-class neighborhood. He attended a state college and over the years held a series of low-paying, clerical-type jobs. But he had trouble getting along with other people. In 2000, he says, he was diagnosed with autism and began receiving disability benefits. He says he received $700 a month, which allowed him to live in public housing until 2014, when he began to fear he would lose those accommodations. He never considered seeking help with a social service organization, though, and he no longer had family to rely on. Once he robbed the first bank, his friends “disowned” him as well, he says.

“They couldn’t understand it,” he says. “They didn’t want anything to do with me.”

Gorton doesn’t know how he will live when he gets out of prison. He says he doesn’t want to commit more crimes or hurt more people, so he is preparing for the scenario he has been trying to avoid this entire time:

“I think I’m going to try my best to endure homelessness.”

On a cold but sunny April morning, Carver wakes up under the shadow of Spokane’s tallest buildings, in an alley behind the Davenport Hotel Tower, part of the city’s flagship luxury hotel collection. He slumps against a wall at his camp, a cement loading area under a covered staircase, tucked behind a “No Trespassing” sign. Trains rattle along tracks two blocks away. He’s surrounded by his own feces. A blanket and a piece of cardboard cushion him from the cement. He has no tent.

“Tents,” he says, “are targets for cops.”

As a city street-cleanup crew pulls up nearby, he rolls up his blankets and packs them into a torn-up trash bag, pressing the air out so he can stuff it under his coat and insulated overalls. But his hands – already cracked and bleeding from the dry, cold air – are stiff with pain. Once the blankets are secure, he takes wincing steps down to the alley, whimpering.

He’s headed a few blocks south, where Shalom Ministries gives him three to-go boxes of pancakes and oatmeal. After passing other homeless people, he complains about the new generation of those living rough. Carver doesn’t understand how they rip each other off, beat each other up, even kill each other – but still sometimes get high together.

Carver gets high on his own and sticks to weed – meth only “once in a blue moon” – because he’s afraid of needles. He says he is careful to avoid eye contact with anyone on the street for fear they might attack or rob him. He says it has been years since he has had a relationship with a woman; they come crying to him when their boyfriends beat them up, he says, but always end up going back to them.

It’s a typical morning for Carver. He wakes up miserable. He searches for food, a bathroom, a place to rest in peace. It seems that everywhere he goes, “No Trespassing” signs remind him that he’s not supposed to be there. Some days, like today, he ends up at Compassionate Addiction Treatment, a local recovery center that lets him inside even though he’s not a patient. He limps there with his to-go boxes, bending to pick up any penny he sees on the sidewalk.

Out front, a woman asks around for a lighter. She sees Carver.

“Oh, Chris, I know you have a lighter,” she says.

“Here you go,” Carver says.

She hands Carver a cigarette in exchange. He is polite and friendly, but when she leaves he sticks out his tongue in disgust.

“Ugh, menthols.”

Inside the treatment center, he takes a chair at a dining table used for group therapy and opens his boxes of food. The oatmeal is so sticky it almost breaks his plastic fork. The pancakes are burned. He tosses out the little boxes of raisins that came with the meal.

He gets up to grab some cookies and coffee, loading up as much as he can. A woman named Rebecca is in his seat when he comes back.

“Excuse me, Rebecca, you’re in my seat,” he says.

She moves. But when he gets up for another cookie, she takes his seat again, even though every other chair at the table is empty. He remains polite.

“Rebecca, you’re in my seat,” he says. “Can you please move?”

She moves again. Finally settled, Carver smothers his pancakes with syrup, his head bent low, studying how the syrup drips over the cakes. He takes a sugar cookie and dips it in his coffee, leaving it in a long time until he deems it ready to take out. He ignores the people shuffling in and out around him. It takes him 30 minutes to finish his food. When he is done, he trades with another homeless man the cigarette he got earlier for a half carton of milk to wash it all down.

A group session is about to start and Carver leaves, back out into the freezing weather. It’s cold days like this that make jail an appealing option, he says. There, at least, he doesn’t have to trek across town to have a meal in peace.

I ask which he prefers in the winter: jail, or life on the streets.

He thinks about it.

“Jail,” he says. Then, a qualifier: “If I was able to smoke weed inside.”

Sarah Gillespie, an associate vice-president at the Urban Institute, a DC-based thinktank, cautions care when using the word “choice” when it comes to people who are homeless. As someone who studies the issue, Gillespie finds herself in a constant battle with what she calls the “myth” that living on the streets or landing in jail is a choice. If given the chance to have housing or not, the vast majority of people would choose housing, her studies have found.

“We do know what the solutions are,” Gillespie says. “It’s really about, what is it going to take to get communities onboard, to scale the solution to the level needed?”

She says the most effective way to end the homelessness-to-jail cycle is also the most obvious: give people housing. An ambitious “housing first” approach, a research-backed practice of giving people a free or affordable place to live without requiring sobriety, is what has helped Houston make great strides in addressing homelessness. Housing advocates say that option can be a money saver compared with the cost of shelters, police services and jail.

There is no widely accepted estimate on how much it would cost to provide stable housing for every person in the US who needs assistance. But an Urban Institute analysis of the federal housing voucher program, which assists low-income households struggling with rent, found that only one in five renters who qualify for assistance receive it. Expanding it to assist all who qualify – an additional 19.7 million people – would cost the US an estimated $62bn a year.

Gillespie cites a Denver-based program that provided free or heavily subsidized housing to chronically homeless people who had the most extended time on the streets and most frequent contact with police – people like Chris Carver. Renters could still use drugs or alcohol and keep their housing, but there were mental health and drug addiction services available for them.

After three years, nearly 80% of people in the Denver program remained in stable housing. That’s proof, Gillespie argues, that even most chronically homeless people would accept a home if it were available. Most notably, arrests for people who were provided housing through the program dropped by 40% compared with a control group.

As for cost, such direct housing could actually save money. Housing through the program cost about $15,000-$16,000 per person per year. But the Urban Institute found that half of those costs were offset by less need for other services such as street sweeps, shelters, police response and emergency room visits. That makes housing a better investment than the current patchwork of services, Gillespie argues: “It’s just a huge cost to allow this cycle of jail, homelessness and emergency services to continue.”

Dones, with the homelessness authority in King county, agrees that providing housing is the best way to help people like Carver. Adequate emergency shelter space is vital, but many people simply will not use it. Some of the dollars spent on adding shelters could be put to better use by investing in housing. Even providing services to so-called tent cities can get expensive. In San Francisco, a homeless encampment run by the city cost an estimated $60,000 per year per tent.

Dones advocates the public purchase of buildings, such as former hotels that can be quickly transformed into affordable housing.

“It doesn’t make sense to me that we would spend the amount of money that we do on some of these other solutions,” Dones says. “And the argument that we need something for people to be in for five years while the housing gets built to me simply doesn’t pass a good sniff test.”

Meanwhile, what is far more costly than providing housing is allowing people who are homeless to go to jail. It costs an average of $47,057 nationwide to jail a person for a year, or $33,274 to put a person in prison for a year, according to the non-profit Vera Institute of Justice.

That’s why experts like Cathy Alderman, public policy officer for the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless, argue that programs like Denver’s need to be scaled up to fit the need. Each time a person chooses jail, it highlights a broken system, she says.

“It’s a policy, a political and a funding failure,” Alderman says.

As those policy debates stall any real progress, people like Carver continue to churn through sorry cycles.

Betty Arford’s home in Post Falls, Idaho, is painted off-white and the front lawn shines a bright green. The tidy home is surrounded by the sound of neighborhood kids playing basketball outside, dogs barking, lawnmowers humming. It is a stark contrast from the life of Chris Carver, Arford’s middle child, 25 miles away on the streets of Spokane.

Arford, 70, says she last talked to her son five years ago, when he was admitted to the hospital with a broken right hip and femur that required emergency surgery. But he hadn’t been hit by a teenager trying to evade police, as he now tells people. Instead, he fell off a bicycle while swerving around a bush, snapping his leg. Soon after the surgery, against medical advice, Carver left the hospital with fresh staples in his skin, taking a wheelchair with him. The reason he gave her? He couldn’t smoke weed there.

That reality also runs contrary to Carver’s oft-repeated claim that he hasn’t seen his family in 30 years. In fact, Arford – who ran a mental health clinic with her husband for seven years – says she spent years trying to help her son, to no end. Now she keeps tabs on where he is by checking the local jail logs.

“We don’t know what to do for him,” she says. “My dread is that some day we’ll get a call that he’s been killed.”

Carver grew up in a Christian family, with an older sister and younger brother in a big house on two acres of land in nearby Kellogg, a small town that is home to a popular ski resort. His father, Gary Carver, was an electrician at the nearby Bunker Hill mine. On weekends, the family went camping.

Carver always had problems in school, the likely result of severe ADHD, Arford says. He would annoy the other kids who, in turn, would bully him. He would often run away from school and not come home until dinner. She home-schooled him for a couple of years of elementary school before enrolling him in middle school. But her son just “couldn’t function” in that environment, and Arford couldn’t get the special education support he needed. She went to the district superintendent. She wrote her US senators. She tried an alternative school. For about six months, Carver had a full-time teacher working exclusively with him until he went back to a traditional school. None of it worked.

As a teenager, Carver was in trouble more and more often. He broke into homes. He stole. He lied. The bullying from other kids also grew worse. When he was 14, Arford says, a few neighborhood kids decided to give him a “hot foot”, dousing his feet with lighter fluid and setting fire to them. It left bad burns on his legs.

Arford doesn’t know if her son has ever been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, as Carver claims, but it would not surprise her. She’s convinced he is not a violent person. He just has trouble with the truth. “He would tell a lie when the truth would suit him better,” she says. “It starts as a lie and then he says it so often that it becomes real.”

Carver, his mom says, acted on impulse, never considering consequences. If he had any money, he would blow it right away. The one thing she remembers her son enjoying was fishing – something he liked to do alone. But she couldn’t trust what he would do on his way back home.

He turned 18, and the arrests started racking up: burglary, theft, misdemeanor battery. He was frequently busted for possession of marijuana, although Arford says he never got into hard drugs. She helped him get social security based on his ADHD diagnosis to pay rent on his own apartments. But he accused her of stealing his money when she managed it; in his own hands, it was soon spent on other things.

“He has no concept of money,” Alford says. “He’d go out and spend all of it and be out within the first couple days. He’s had a lot of people offer him housing or treatment. He either doesn’t follow through, or he does and then gets in trouble where he’s at.”

Arford doesn’t know how to help her son. She still wonders if things would have been different if there was more understanding of a child like him when he was in school. He’s almost 50 now, and has lived most of his life on the streets or in jail. She thinks he needs institutional mental health treatment. Legally, he can’t be institutionalized unless he were deemed a threat to himself or others, and America long ago decided it is cruel to institutionalize someone who is not a threat against their will. Still, Arford believes her son had been happiest when he was in a mental hospital, or in an extended stay behind bars. He thrives in a more restrictive, regulated environment.

Maybe, she wonders, her son knows that about himself.

Sitting on the front steps of a church in downtown Spokane, I ask Carver what he wants for himself. If he could shape the next few years of his life, what would it look like?

“This,” he replies. “Until something comes up.”

“What would come up?” I ask.

He doesn’t know.

He mentions that a friend is in housing where he can smoke weed and not be bothered. We’re sitting across the street from an apartment complex run by Catholic Charities Eastern Washington. It’s part of the organization’s “housing first” strategy in Spokane, which has drawn debate locally over the idea of giving housing away with no accountability.

“Do you want housing?” I ask.

“It depends on what it is,” he says.

He suddenly changes the subject: “Do you mind if I smoke weed?”

He’s not allowed to smoke on the grounds of the treatment center, so he goes across the block to the steps of a church. He ignores the “No Trespassing” sign posted there. After his third hit, he exhales the smoke, and his world seems to slow down and focus. Even his speech – usually a slurred mumble – is clearer.

Unprompted, he tells a story about how it snowed on his 13th birthday – 9 July 1986. It’s another reflection on his place in an unforgiving world: snow fell on his birthday, when it was supposed to be warm and sunny. It’s also untrue, according to weather records.

As the story goes, Carver sees the snow, and he goes into his mom’s room and tells her.

“Mom, it’s snowing in July,” he says.

She doesn’t believe him.

“No, look,” he begs.

Then, as Carver recalls it, his mom looks outside and sees that he’s right. She’s just as shocked as he is. It’s snowing on his birthday, of all days.

“It’s snowing,” she agrees. “In July.”

Carver smiles as he finishes this story, and, with police cruisers circling the area, he gathers his coat and drags himself into an alley.

READ MORE

Trump with Kari Lake. (photo: Mario Tama/Getty Images)

Trump with Kari Lake. (photo: Mario Tama/Getty Images)

The GOP's 'Terrifying' Embrace of Violence Pre-Election

Todd Zwillich, Vice

Zwillich writes: "The callousness about the Paul Pelosi attack just shows how low they'll go."

The callousness about the Paul Pelosi attack just shows how low they'll go.