UNDER CONSTRUCTION - MOVED TO MIDDLEBORO REVIEW AND SO ON https://middlebororeviewandsoon.blogspot.com/

Friday, December 30, 2022

BALLOT INITIATIVES, ABORTION RIGHTS

FOCUS: Elaine Godfrey | Sudden Russian Death Syndrome

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

It’s not a great time to be an oligarch who’s unenthusiastic about Putin’s war in Ukraine.

Over the weekend, Pavel Antov, the aforementioned sausage executive, a man who had reportedly expressed a dangerous lack of enthusiasm for Vladimir Putin’s war against Ukraine, was found dead at a hotel in India, just two days after one of his Russian travel companions died at the same hotel. Antov was reported to have fallen to his death from a hotel window. The meat millionaire and his also-deceased friend are the most recent additions to a macabre list of people who have succumbed to Sudden Russian Death Syndrome, a phenomenon that has claimed the lives of a flabbergastingly large number of businessmen, bureaucrats, oligarchs, and journalists. The catalog of these deaths—which includes alleged defenestrations, suspected poisonings, suspicious heart attacks, and supposed suicides—is remarkable for the variety of unnatural deaths contained within as well as its Russian-novel length.

Some two dozen notable Russians have died in 2022 in mysterious ways, some gruesomely. The bodies of the gas-industry leaders Leonid Shulman and Alexander Tyulakov were found with suicide notes at the beginning of the year. Then, in the span of one month, three more Russian executives—Vasily Melnikov, Vladislav Avayev, and Sergey Protosenya—were found dead, in apparent murder-suicides, with their wives and children. In May, Russian authorities found the body of the Sochi resort owner Andrei Krukovsky at the bottom of a cliff; a week later, Aleksandr Subbotin, a manager of a Russian gas company, died in a home belonging to a Moscow shaman, after he was allegedly poisoned with toad venom.

The list goes on. In July, the energy executive Yuri Voronov was found floating in his suburban St. Petersburg swimming pool with a bullet wound in his head. Think Gatsby by the Neva. In August, the Latvia-born Putin critic Dan Rapoport apparently fell from the window of his Washington, D.C., apartment, a mile from the White House—right before Ravil Maganov, the chairman of a Russian oil company, fell six stories from a window in Moscow. Earlier this month, the IT-company director Grigory Kochenov toppled off a balcony. Ten days ago, in the French Riviera, a Russian real-estate tycoon took a fatal tumble down a flight of stairs.

To reiterate: All of these deaths occurred this year.

One could argue that, given Russia’s exceptionally low life expectancy and unchecked rate of alcoholism, at least some of these fatalities were natural or accidental. Just because you’re Russian doesn’t mean you can’t accidentally fall out of an upper-story window. Sometimes, people kill themselves—and the suicide rate among Russian men is one of the highest recorded in the world. For Edward Luttwak, a historian and military-strategy expert, that’s at least part of what’s happening: an outbreak of mass despair among Russia’s connected and privileged elite. “Imagine what happens to a globalized country when sanctions kick in,” he told me. “Some of them will commit suicide.” But the sheer proliferation of these untimely deaths warrants a closer look.

After all, this is what the Kremlin does. There is precedent for this phenomenon. In 2020, Russian agents poisoned—but failed to kill—the Putin critic Alexei Navalny with a nerve agent; a decade earlier, they succeeded in a similar attempt on the Russian-security-services defector Alexander Litvinenko. In 2004, when Viktor Yushchenko ran against a Kremlin-backed opponent for Ukraine’s presidency, he was poisoned with dioxin and left disfigured. Thirty years earlier, the Bulgarian secret service, reportedly with the help of the Soviet KGB, killed the dissident Georgi Markov by stabbing him on the Waterloo Bridge in London with a ricin-laced umbrella tip. Russian agents often “turn to the most exotic,” Luttwak told me. “People who do assassinations for commercial purposes look at [their methods] and laugh.”

Suicides are more difficult to decipher. For oligarchs who have failed to show sufficient loyalty to Putin, coaxed suicide is not an implausible scenario. “It is not uncommon to be told, ‘We can come to you or you can do the manly thing and commit suicide, take yourself off the chess board. At least you’ll have the agency of your own undoing,’” Michael Weiss, a journalist and the author of a forthcoming book on the GRU, the Russian military-intelligence agency, told me. Did Antov really fall out his window in India? Was he pushed by a Kremlin agent? Or did he get a call that threatened his family and made him feel he had no option but to leap? “All of these things are possible,” Weiss told me.

In the Kremlin’s Gothic murderverse, imagination is key.

Defenestration has been a favorite method of removing political opponents since the early days of multistory buildings, but in the modern era, Russia has monopolized the practice. Like Tosca’s climactic exit from the battlements of Castel Sant’Angelo, death by falling from a great height has a performative, even moral aspect.

In Russian, this business of assassination is known as mokroye delo, or “wet work.” Sometimes, the main purpose is to send a message to others: We’ll kill you and your family if you’re disloyal. Sometimes, the goal is to simply remove a troublesome individual.

A few years after the Russian whistleblower Alexander Perepilichny died while jogging outside London in 2012, at least one autopsy detected chemical residue in his stomach linked to the rare—and highly toxic—flowering plant gelsemium. “These are the clues of evidence that the Russians are fond of using,” Weiss told me. A calling card, if you will. “They want us to know that it was murder, but they don’t want us to be able to definitely conclude it was murder.”

Poisoning has that ambiguity. It is literally covert, concealed, sometimes hard to detect. Defenestration is a bit less ambiguous. Yes, it could be an accident. But it’s a lot easier to conclude it was murder—an overt assassination.

“Things that mimic natural causes of death like a heart attack or a stroke, the Russians can be quite good at doing that,” Weiss said. The deaths range in their showiness, but they’re all part of the same overarching scheme: to perpetuate the idea that the Russian state is a deadly, all-powerful octopus, whose slimy tentacles can search out and seize any dissident, anywhere. As the Bond franchise had it, the world is not enough.

The war in Ukraine is not universally popular among Russia’s ruling elite. Since the conflict began, sanctions on oligarchs and businessmen have constrained their profligate and peripatetic lifestyles. Some are, understandably, said to be unhappy about this. High-level Russian elites feel as if Putin “has essentially wound the clock backwards,” Weiss said, to the bad old days of Cold War isolation.

This year’s spate of deaths—so brazen in their number and method as to suggest a lack of concern about plausible, or even implausible, deniability—is quite possibly Putin’s way of warning Russia’s elites that he is that deadly octopus. The point of eliminating critics, after all, isn’t necessarily to eliminate criticism. It is to remind the critics—with as much flair as possible—what the price of voicing that criticism can be.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

Kelly Rissman | Meadows Goes Up in Flames: Hutchinson Claims She Watched Him Burn Documents "Roughly a Dozen Times"

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The former aide's testimony details meetings with Rep. Scott Perry before records were burned.

Hutchinson testified on May 17 to the January 6 committee; the fiery revelation was found in the House panel’s newly released transcripts of the former aide’s deposition.

When Rep. Liz Cheney (R-Wyo.) asked if Hutchinson saw Meadows use the fireplace to burn records, she replied:

“The Presidential Records Act only asks that you keep the original copy of a document. So, yes. However, I don’t know if they were the first or original copies of anything. It’s entirely possible that he had put things in his fireplace that he also would have put into a burn bag that there were duplicates of or that there was an electronic copy of.”

Hutchinson added that she estimated watching Meadows burn documents “roughly a dozen times.”

Although the New York Times and Politico had previously reported the accusation, the transcripts were just released publicly, adding fuel to the fire, so to speak.

The former aide also insinuated that Meadows tried to keep meetings off official records. Hutchinson testified that she remembered Meadows telling Oval Office staffers in either the end of November or early December 2020: “Let’s keep some meetings close hold. We will talk about what that means, but for now we will keep things real tight and private so things don’t start to leak out.” She said there “were certain things that had potentially been left off” the Oval Office diary, although she said she didn’t know the specific documents.

She did, however, remember one specific name: Rep. Scott Perry (R-Pa.). She said that she recalled at least two burnings following Meadows’ meetings with Perry.

The House panel in May said the Pennsylvania congressman was “directly involved” with efforts to instate Jeffrey Clark as acting Attorney General, as Clark had indicated that he would support the plan to encourage states to appoint Trump-supporting electors.

Hutchinson said Meadows and Perry discussed “election issues.” during their meeting. More specifically, Hutchinson said, “The Vice President's role on January 6th….Mr. Perry started coming to meet with Mr. Meadows about what he believed could happen on January 6th, and they were preparing various PowerPoints and he would bring physical material.”

The release of this transcript comes in the wake of bombshell news from last week: claims that Trump’s former ethics attorney, Stefan Passantino, advised Hutchinson to give misleading testimony to the January 6 committee.

Passantino is taking a leave of absence from his firm following the revelation; his name was also removed from Michael Best … Friedrich’s firm website.

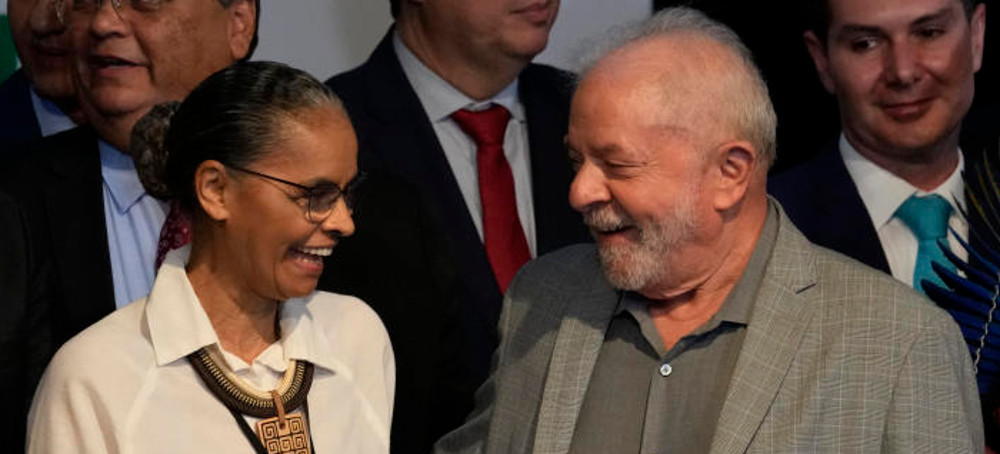

READ MORE  Brazil's President-elect Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva and newly-named Environment Minister Marina Silva, smile during a meeting where he announced the ministers for his incoming government, in Brasilia, Brazil, Thursday, Dec. 29, 2022. Lula will be sworn-in on Jan. 1, 2023. (photo: Eraldo Peres/AP)

Brazil's President-elect Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva and newly-named Environment Minister Marina Silva, smile during a meeting where he announced the ministers for his incoming government, in Brasilia, Brazil, Thursday, Dec. 29, 2022. Lula will be sworn-in on Jan. 1, 2023. (photo: Eraldo Peres/AP)

Both attended the recent U.N. climate conference in Egypt, where Lula promised cheering crowds “zero deforestation” in the Amazon, the world's largest rainforest and a key to fighting climate change, by 2030. “There will be no climate security if the Amazon isn't protected,” he said.

Silva told the news network Globo TV shortly after the announcement that the name of the ministry she will lead will be changed to the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change.

Many agribusiness players and associated lawmakers resent Silva. That stems from her time as environment minister during most of Lula's prior presidency, from 2003 to 2010.

Lula also named Sonia Guajajara, an Indigenous woman, as Brazil’s first minister of Indigenous peoples, and Carlos Fávaro, a soybean producer, as agriculture minister.

Silva was born in the Amazon and worked as a rubber tapper as an adolescent. As environment minister she oversaw the creation of dozens of conservation areas and a sophisticated strategy against deforestation, with major operations against environmental criminals and new satellite surveillance. She also helped design the largest international effort to preserve the rainforest, the mostly Norway-backed Amazon Fund. Deforestation dropped dramatically.

But Lula and Silva fell out as he began catering to farmers during his second term and Silva resigned in 2008.

Lula appears to have convinced her that he has changed tack, and she joined his campaign after he embraced her proposals for preservation.

“Brazil will return to the protagonist role it previously had when it comes to climate, to biodiversity,” Silva told reporters during her own appearance at the U.N. summit.

This would be a sharp turnabout from the policies of the outgoing president, Jair Bolsonaro, who pushed for development in the Amazon and whose environment minister resigned after national police began investigating whether he was aiding the export of illegally cut timber.

Bolsonaro froze the creation of protected areas, weakened environmental agencies and placed forest management under control of the agriculture ministry. He also championed agribusiness, which opposes the creation of protected areas such as Indigenous territories and pushes for the legalization of land grabbing. Deforestation in Brazil’s Amazon reached a 15-year high in the year ending in July 2021, though the devastation slowed somewhat in the following 12 months.

In Egypt, Lula committed to prosecuting all crimes in the forest, from illegal logging to mining. He also said he would press rich countries to make good on promises to help developing nations adapt to climate change. And he pledged to work with other nations home to large tropical forests — the Congo and Indonesia — in what could be coordinated negotiating positions on forest management and biodiversity protection.

As environment minister, Silva would be charged with carrying out much of that agenda.

Silva is also likely to face resistance from Congress, where the farm caucus next year will account for more than one-third of the Lower House and Senate.

Two lawmakers allied with Lula who come from the nation’s agriculture sector told The Associated Press before the announcements they disagree with Silva’s nomination given the conflict of her prior tenure. They spoke on condition of anonymity due to fear of reprisals.

Others were more hopeful. Neri Geller, a lawmaker of the agribusiness caucus who acted as a bridge to Lula during the campaign, said things had changed since Silva's departure in 2008.

“At the time, Marina Silva was perhaps a little too extremist, but people from the agro sector also had some extremists," he said, citing a strengthened legal framework around environmental protection as well. “I think she matured and we matured. We can make progress on important agenda items for the sector while preserving (the environment) at the same time."

Silva and Brazil stand to benefit from a rejuvenated Amazon Fund, which took a hit in 2019 when Norway and Germany froze new cash transfers after Bolsonaro excluded state governments and civil society from decision-making. The Norwegian Embassy in Brazil praised “the clear signals” from Lula about addressing deforestation.

“We think the Amazon Fund can be opened quickly to support the government’s action plan once the Brazilian government reinstates the governing structure of the fund,” the embassy said in a statement to the AP.

The split between Lula and Marina in his last administration came as the president was increasingly kowtowing to agribusiness, encouraged by voracious demand for soy from China. Tension within the administration grew when Mato Grosso state’s Gov. Blairo Maggi, one of the world’s largest soybean producers, and others lobbied against some of the anti-deforestation measures.

Lula and Silva were also at odds over the mammoth Belo Monte Dam, a project that displaced some 40,000 people and dried up stretches of the Xingu River that Indigenous and other communities depended upon for fish. Silva opposed the project; Lula said it was necessary to meet the nation’s growing energy needs and hasn’t expressed any regret since, despite the plant’s impact and the fact it is generating far below installed capacity.

After Silva resigned, she quit Lula’s Workers’ Party and became a fierce critic of him and his successor, Dilma Rousseff. Silva and Lula didn’t begin to reconcile until this year’s presidential campaign, finding common cause in defeating Bolsonaro, whom they deemed an environmental villain and would-be authoritarian.

Caetano Scannavino, coordinator of Health and Happiness, an Amazon nonprofit that supports sustainable projects, said Silva “grew to become someone larger than only an environment minister.”

“This is important, as the challenges in the environmental area are even greater than two decades ago,” Scannavino said, citing growing criminal activities in the Amazon and increasing pressure from agribusiness eager to export to China and Europe. "Silva’s success is Brazil’s success in the world, too. She deserves all support.”

READ MORE  Trailers sit in the yard of the Logan County compound where, officials say, authorities found what they believe are human remains. (photo: Nick Oxford/Washington Post)

Trailers sit in the yard of the Logan County compound where, officials say, authorities found what they believe are human remains. (photo: Nick Oxford/Washington Post)

A high-stakes criminal investigation is a window into the often unseen threat of white-supremacist prison gangs

Harris’s son, 33-year-old Nathan Smith, had vanished along a dirt road in Oklahoma one freezing night more than two years earlier. Detectives had long stopped checking in with her, and Harris could feel her search growing lonelier with each passing month.

The call in April, from an advocate for families of the missing, wasn’t encouraging, but it was a lead: Authorities in rural Logan County, just north of here, had discovered human remains belonging to more than one person. Also, the caller added delicately, the remains weren’t intact.

Harris, 58, sat down to steady herself. She listened, then hung up to tell her daughter.

“I said, ‘Lou, they found these bodies,’ ” Harris recalled. “ ‘They’ve been burned and cut.’ ”

Smith is among a dozen or more people who have disappeared in recent years from the wooded, unincorporated terrain outside the Oklahoma City metro area, a rural haven for drug traffickers. Some families said they’re scared to call police or even to put up “missing person” signs because they suspect the involvement of violent white-supremacist prison gangs.

In April, authorities acting on a tip said they found charred piles of wood and bone on a five-acre patch of Logan County, opening one of the grisliest and most sensitive criminal investigations in Oklahoma’s recent history.

Behind the 10-foot metal walls of a compound with links to the Universal Aryan Brotherhood, a white-supremacist prison gang, officers found what they believe to be a body dumping ground where multiple people ended up dismembered and burned, according to four Oklahoma officials with knowledge of the investigation. They spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the extraordinary security precautions around the case.

The Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation, or OSBI, which is leading the multiagency state and federal probe, confirms that remains have been found but will not say how many. An April 29 report in the Oklahoman newspaper — the first news of the discovery — quoted the state medical examiner and other sources as saying agents were investigating “whether a white supremacist prison gang is behind nine or more disappearances” after the discovery of “the comingled remains of possibly three people.” The report said remains also were found at a second site, near an oil well about 18 miles away in the tiny town of Luther.

Four months later, the scope of the case remains murky. A law enforcement official, who, like others, spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss an ongoing investigation, said they were informed the count was up to “12 different DNA profiles.” One family of a missing person said they were told of eight; another heard about three.

The OSBI has taken significant steps to keep the investigation opaque, including advising families of the missing to stay quiet.

“We’re just trying to keep some people alive at this point,” a second official said, describing the struggle to protect potential witnesses.

That level of danger is a jarring reminder of the unseen threat of white-supremacist prison gangs, whose leaders run crime syndicates from behind bars through a network of “enforcers” on the outside, according to extremism monitors and Justice Department court filings.

The gangs have carried out hate-fueled attacks both in and out of prison, with the bulk of their free-world violence targeting rivals and informants, authorities say. Because the gangs typically keep their business within the criminal underground, the attacks go largely undiscussed in the broader national conversation about rising violence by far-right groups.

Oklahoma is a “problem state,” with at least five significant white-supremacist prison gangs, said Mark Pitcavage, an Anti-Defamation League researcher who has monitored the groups for decades. He co-authored a 2016 study that called prison gangs the fastest-growing and deadliest sector of the U.S. white-supremacist movement, noting that they “combine the criminal intent and know-how of organized crime with the racism and hate of white supremacy, making them twice as dangerous.”

The Logan County investigation, authorities say, involves one of the most ruthless of the gangs: the Universal Aryan Brotherhood, also known as the UAB.

One of the main UAB “shot-callers,” authorities say, is 57-year-old Mikell “Bulldog” Smith, an inmate so violent that an Oklahoma prison report once called him “the most dangerous man in the penitentiary” and corrections officials built a special cell for him in 1989. Smith is serving life without parole for the 1985 killing of a math teacher in a robbery. Soon after arriving in prison in 1987, he stabbed a fellow inmate. Two years later, he nearly killed a prison guard by stabbing him in the heart with a blade attached to a broom handle. In 2014, Smith was convicted of choking a cellmate to death with a sheet.

Members of Smith’s extended family own various parts of the five-acre area where remains were found in Logan County. Smith’s wife, Robin, was listed as owner of the fortified compound; his brother Charles owns an adjacent property, according to sale records. Another brother, Phillip, disappeared from the county in 2020, one of the long list of cases authorities say are under review.

On Aug. 19, according to state investigators, another Smith relative, David, was arrested at the compound on charges related to a stolen vehicle and possession of a firearm by a felon.

In the OSBI’s few public statements about the remains, there is no mention of the alleged ties to one of Oklahoma’s bloodiest prison gangs or reference to the site in Luther. The statement said only that “law enforcement from multiple agencies recovered bone fragments” in Logan County and were working to identify them and determine the cause of death.

The medical examiner’s office and law enforcement agencies involved either declined to comment on the record or never responded to queries. The OSBI declined to comment beyond its news releases.

“The investigation is very fluid and very active,” said an OSBI release dated Aug. 8. “Because of that, the volume of rumors and speculation is high. The OSBI will not comment on rumors as that can jeopardize the ongoing investigation.”

The statement said state investigators and sheriff’s offices in three counties “have been working closely with the families of the missing persons,” including collecting DNA samples to help with identification. That work will take time, the release said, because of “the physical condition of the remains recovered.”

Buried secrets

On a scorching recent afternoon, Carol Knight looked out over her 20-acre plot in rural Choctaw, about half an hour’s drive from where the remains in Logan County were found. A successful bail bond agent, Knight bought the property in 2020 with plans to build a country dream home.

“Instead, I got a chop shop,” she said.

As Knight began clearing the land, she and her husband uncovered jaw-dropping surprises buried underground: “We dug up a car, we dug up a motorcycle. We hauled three boats off the property.” She carted off about 300 tires, apparent leftovers from cars that were “chopped” and sold for parts. Knight said she almost broke her ankle falling in a “hidey hole,” one of several camouflaged pits.

The previous residents had extensive criminal records and hung with a crowd that included known UAB associates, according to authorities and public records.

Knight said she saw the buried junk as an expensive nuisance — until she received a tip last year that a body also might be hidden on her land. Unsettled, Knight halted work and sought help from fellow bondsman Jathan Hunt, a licensed private detective who brings his specially trained German shepherds on searches for missing people.

“I said, ‘J, why don’t y’all bring your dogs out here and see if I got a dead body,’ ” she recalled.

The rumors were tied to the disappearance of 43-year-old David Anthony Orr, a Hispanic man from the Oklahoma City area who struggled with a methamphetamine addiction and ran in the same drug circles as UAB associates, according to one of Orr’s family members and public information compiled by Hunt.

In January, Hunt searched Knight’s property as part of a team of about two dozen volunteers using five dogs with training on “clandestine grave detection.” When the dogs “alerted” to two areas — near a large pit and a pond — the searchers called Oklahoma County investigators. The authorities left with a bone that Hunt thought resembled a metatarsal, part of the foot, but he said he never heard back on whether it was determined to be human.

After the search, Hunt said, he kept thinking about Orr and added the case to volunteer work he was doing with Oklahoma City Metro Search and Rescue, a nonprofit group that helps families of missing relatives.

In most cases he’d worked on, Hunt said, families were eager to hang posters or appear on local news. Not so with Orr, who was last seen on Jan. 16, 2021.

“This was the first one where I was like, ‘Man, no one is looking for this guy, not even his family or friends,’ ” Hunt said. “I thought, ‘That’s weird.’ ”

Hunt made inquiries and discovered that Orr does indeed have relatives who are desperate to find him — it’s just too dangerous, he said, for them to publicly seek information on his whereabouts.

One of Orr’s relatives, speaking on the condition of anonymity because of the risks, said they were advised by people they described as Orr’s associates to stop searching or else they’d “end up like him.” On the street, the relative said, Orr’s death is accepted as fact, but the family can’t acknowledge it or mourn without confirmation.

“You have to live with the anxiety, you have to live with the fear that these people are still out there,” the relative said. “You’ve got to be careful who you talk to.”

Using the tips he was picking up, Hunt said, he found overlapping social connections among at least five missing people, including Orr, and UAB associates. Last spring, Hunt said, he received a tip that Orr’s body was burned and buried on a property in Logan County, possibly along with three others. Hunt said he tried to share the information with investigators, only to get the brush-off.

Finally, Hunt said, he reached a lead detective on the case, who told him to “sit on it” because “we’ve got something in the works.”

Two days later, authorities carried out the raid in which they found remains. The Logan County property matched the description Hunt had heard about in the search for Orr.

Hunt called Knight, whose response was: “Oh, s---.”

A risky raid

At daybreak on April 13, dozens of law enforcement officers massed outside the Logan County compound with a search warrant, prepared to face an ambush.

Given the reputation of the UAB, planners had gone over all the worst-case scenarios, law enforcement officials recalled. They had taken into account the possibility of booby traps and explosives. They wondered if cages could be opened remotely for the simultaneous release of the more than 25 pit bulls on the property.

Above all, they worried about a potential shootout as they entered through what Logan County Sheriff Damon Devereaux called the “fatal funnel,” a narrow, metal-sided driveway entrance.

“We were prepared for the worst day of our lives,” he said.

Instead, authorities easily swept onto the empty site. Devereaux said he counted 28 dogs in cages; they looked healthy and well-fed. He recalled it was the second day of the search when a text arrived from an OSBI investigator saying: “Just confirming that we have found some human remains.”

“Holy cow, this is a big deal,” the sheriff recalled thinking.

Devereaux agreed to address only parts of the investigation that are already public knowledge. He declined to give details on the remains or any possible suspects, deferring to the OSBI.

Before he became sheriff in 2017, Devereaux, 52, had served as police chief in his hometown, Guthrie, the Logan County seat. He dealt with college parties and garden-variety crime, he said, but nothing like the violent characters he’s encountered as sheriff.

The county jail, Devereaux said, regularly holds associates of white-supremacist prison gangs, people facing hits from Mexican cartels, and a host of others charged in connection with the drug rings that operate in the backwoods of middle America.

“They’re introducing me to the Irish Mob and the UAB and it’s just like, ‘Excuse me?’ ” Devereaux said, referring to white-supremacist prison gangs in the state. “I had no idea until I became the sheriff, because it’s confined in these walls.”

Devereaux considers himself a stickler for policing that prioritizes constitutional rights. So, he said, when he first noticed the compound “getting fortified with metal 10-foot fencing and iron gates,” he was suspicious but had no probable cause to investigate.

“We’re a county that likes to burn our trash, shoot our guns and drink our beer. And that’s kind of what we embrace in Oklahoma, the freedom to do all that,” he said. “There’s a lot of people who move out there to be left alone.”

But then, maybe six months ago, he said, his deputies started hearing rumors about a missing man whose body was hidden in Logan County. Other law enforcement officers started looking into the tips, too, Devereaux said, and soon the investigation ballooned into a mammoth effort with about half a dozen agencies involved.

“This puzzle had a lot of lost pieces,” Devereaux said. “And now all of a sudden we’re putting some pieces together and starting to see the picture.”

An agonizing wait

Harris, the mother of Nathan Smith, who is no relation to Mikell Smith, said she calls the medical examiner’s office almost weekly to make sure investigators are still looking for her son among the remains.

When Harris heard the latest twist — a possible connection to a white-supremacist prison gang — her heart sank. Early in her search, she said, a family friend had helped her go through her son’s social media contacts looking for clues about his disappearance. “She says, ‘They’re Aryan Brotherhood, look! All these people — a lot of them — are doing the signal,’ ” Harris said, alluding to gang hand signs. “I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, what has my son got into?’ ”

As with other missing people, Nathan Smith’s intersection with suspected prison-gang associates stemmed from drugs, specifically methamphetamines, his mother said. The UAB is known to be a major player in Oklahoma meth trafficking, according to authorities and a 2018 federal indictment of 18 members on racketeering charges.

The indictment, one of the most detailed public accounts of UAB operations, accused the gang of distributing an estimated 2,500 kilos of meth annually in Oklahoma, and laid out related crimes such as “murder, kidnapping, witness intimidation, home invasions.” As part of a plea agreement, one member described how he and others kidnapped suspected informants and “used tarps, shovels, blow torches and other items in an attempt to scare and intimidate the victims.”

Today, the UAB remains active, still tied to gruesome homicides and big drug cases, according to court papers and news reports. In August, nine UAB-linked suspects were charged in the killing of a rival gang member who prosecutors say was lured out of his motel room, tortured and dumped in a ditch.

The missing people authorities have mentioned in connection with the Logan County case are mostly men with long histories of drug arrests and prison stints. One exception is 21-year-old newlywed Audrey Slack, who hasn’t been seen since Jan. 11.

That morning, Slack called her family from a motel outside Oklahoma City while on a road trip with her husband, Stephen Walker, who is more than twice her age and whose tattoos signal membership in another white-supremacist prison gang.

Slack said to expect the couple home by 8 p.m., but they never arrived. Their black pickup truck was found with a bullet hole and traces of blood and bleach on the interior, according to a search warrant filed Aug. 2.

Slack’s relatives, who asked that their names and other identifying details be withheld, said investigators had called out of the blue in April to ask for dental records. The family, which had already submitted DNA samples, refused unless the detective told them what was going on. That’s when the family learned that multiple human remains had been found about a 15-minute drive from where the missing couple were last seen.

Since that day, they’ve been stuck in the same excruciating limbo as the other families, waiting for identifications that could take many more months.

“I need to know,” said one of Slack’s relatives. “I need to settle my heart.”

READ MORE  Volunteer Olena Bila poses for a photograph with her dog Baron and cages with animals rescued from one of Ukraine's front-line settlements in Kharkiv Oblast in October. (photo: Olena Bila)

Volunteer Olena Bila poses for a photograph with her dog Baron and cages with animals rescued from one of Ukraine's front-line settlements in Kharkiv Oblast in October. (photo: Olena Bila)

Dozens of animal corpses, either killed by Russian troops or dead of starvation, were lying throughout the zoo’s territory. But in one locked cage, they noticed an animal that was still fighting for its life.

"(The bear) was in terrible condition. Five more days and we wouldn't have saved him," says Olena Bila, a volunteer who came to the bear’s rescue in late September, shortly after Ukrainian soldiers called for volunteers to help.

When Bila arrived at the site, she saw the bodies of killed wolves, foxes, and empty cages that she believed had belonged to lions. She found the bear locked in a tiny cell, neglected, thin, and "drowning in his excrement."

"He was concussed," Bila says, adding that a shell had exploded near his cage. "It was hard to look at."

Bila and her team had to act quickly to move the animal, since Russian troops could open fire against the liberated village at any moment. Luckily, the mission was successful. Bila says the bear now lives in "good conditions" at a zoo in the Polish city of Poznan and feels better.

They named him Yampil after the village he was found in.

According to the United Nations, over 13 million Ukrainians have been forced to flee their homes since the beginning of Russia's all-out war, including 7 million refugees and 6.5 million internally displaced. Countless animals were left behind, forced to fight for survival amid Russian attacks and cold weather.

For many of them, the only chance to survive is to be rescued by Ukrainian volunteers, who risk their lives traveling to front-line settlements and liberated territories to save abandoned cats and dogs, farm animals, and wild ones.

"Most humanitarian missions and charities are aimed at helping people, and I can understand that," says volunteer Kateryna Arisoy.

"But I believe that all creatures deserve to live," she adds.

"(Animals) suffer no less than people, and in some cases — even more."

'Ukrainians who care'

For Arisoy, the battle to save animals started over a decade before Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. In 2011, she co-founded a small animal shelter in her home town of Bakhmut, Donetsk Oblast.

"I was so naive to think that we had already survived the hardest times (the Russian invasion of Donbas in 2014-2022)," Arisoy says, adding that she had never expected the all-out war to hit Bakhmut so hard.

She fled Bakhmut in April amid non-stop Russian attacks but well before it became the focus of some of the heaviest fighting along the entire front line. Since then, she has returned to the city multiple times to help animals, “those who can't ask for help."

In the city of Dnipro, where Arisoy temporarily found a new home, she joined the Vetmarket Pluriton, a team of volunteers that help and rescue animals affected by the war. Arisoy says volunteers often get calls from locals telling them where the help is needed.

The volunteers started by rescuing animals from the liberated towns of Irpin and Bucha outside Kyiv. When fighting intensified in the east of Ukraine, they began traveling to Bakhmut and other settlements in the area.

Bila, on the other hand, was "far from volunteering" before the full-scale invasion: In the early days of the war, she and her husband had to shut down their small business in Kyiv Oblast and "devote themselves to helping others" by joining the team of UAnimals, a nonprofit that advocates for animal rights.

On March 8, during one of their missions near the capital, Ukrainian soldiers showed them a small wounded puppy that had recently come to them.

"We took him and started treating his wounds," Bila says. "When you look into his eyes, you can drown. We decided to keep him."

The puppy turned out to be a Bernese Mountain Dog. They named him Baron. He has accompanied them during every "evacuation, under shelling, and in all the front-line hot spots."

"He goes ahead of us during rescue missions," Bila says. "He is always on alert. When we are loading animals (into their mini-bus), and he hears (shells) flying towards us, he starts barking, warning us to hide."

During another mission, they once stopped at a gas station, where a Ukrainian family with a little daughter spotted a cute puppy the couple had just rescued from a war-torn settlement.

"We offered for them to take that puppy, but they refused, saying it was too big of a responsibility," Bila says.

After they had driven 100 kilometers from the gas station, a car appeared behind them and honked for them to stop in the middle of the highway.

"It was the same family we had offered the puppy," Bila says. "When we left, the girl started crying, persuading her parents to keep it. So they chased us for more than 100 kilometers to get this puppy. It was adorable," she adds.

In September, Bila went to the liberated city of Izium in Kharkiv Oblast. She says Ukrainian soldiers rescued 10 dogs there and decided to adopt all of them into their families.

"We brought the dogs to their new families, not shelters," Bila says. "They are happy now, waiting for the soldiers to return."

"There are many Ukrainians who care about animals, even despite the horrors of the war," Bila adds.

Striking difference

Seeing Ukrainian soldiers treat animals kindly and rescue them amid heavy fighting touches Bila's heart deeply.

"Our soldiers are humane, kind-hearted, and brave. If they see that an animal needs help, even if it's in a dangerous place, they will still try to save it," she says.

"That distinguishes our soldiers (from the Russian troops)," she adds.

Volunteers say that the difference is especially striking in the settlements liberated from the Russian occupation.

When Arisoy visited the Yampil zoo and the nearby nature reserve shortly after the area’s liberation, she was shocked to see what Russians left of the place she used to enjoy.

"Russian soldiers were based there during the occupation. Most of the animals died of hunger or from shelling," she says.

"But Russians also ate many animals," she says, adding that they learned about that from locals.

Upon arrival at the reserve, Arisoy saw "skins, torn-off heads, and bones" of a deer, ostrich, and bison. There, she also saw the remains of her "favorite alpaca."

"As soon as I saw the skin, I immediately recognized who it was and almost fainted," she says.

Out of nearly 200 animals at the zoo and the reserve, only two horses, four donkeys, a couple of pigs and six piglets, a lama, a wild bear, a goat, a duck, and a cat survived the Russian occupation. Arisoy says volunteers evacuated them all.

At the zoo, she says they also found a corpse of a camel that died of starvation: "Only bones remained," Arisoy says.

Bila assumes Russian soldiers were also "killing animals for fun," as volunteers found wild animals "shot dead in their cages" at the zoo. She says it was the first time she saw animals that had been shot dead.

Though most of the animals they rescue have been abandoned by their owners escaping the war, there are some whose owners had been killed. From one of the liberated half-ruined settlements of Kharkiv Oblast, Bila rescued a dog with a litter of small puppies.

The dog's owner, a local veterinarian, was killed in a Russian airstrike on the village, she says. His house was destroyed, but his pets somehow survived the attack. Now, other volunteers take care of the pets and look for new homes for them.

There are countless similar stories all over Ukraine, Bila says. That's why she and her husband work almost non-stop to rescue as many as possible, often putting their lives in danger.

Risking lives

Arosoy says animal rescue missions during war mean constant threats to their lives.

"We come under fire all the time," she says, adding that a rocket fell in front of their car when they were driving near Bakhmut recently.

Bila agrees, saying that recently they evacuated five horses from a farm in liberated Kherson under the heavy shelling. When they were on a mission to rescue a bear from Bakhmut, a projectile fell nearly 10 meters away from them, Bila says. Luckily, it didn't explode.

"Something protects, perhaps, because we are on such a good mission — saving the lives of our animals," Bila says.

But Russian attacks are not the only threats the volunteers face.

"Three members of our team were taken prisoner by the Russian troops when they went to Lysychansk to evacuate children and a local animal shelter," Arisoy says.

Russian forces captured Lysychansk, the last Ukrainian holdout in Luhansk Oblast, after heavy fighting, in early July. Arisoy says their volunteers were in the city at that time. She can not disclose details but says they are still in captivity.

Despite the many challenges and risks they are facing, Bila says there "was not a second she regretted becoming a volunteer."

"It is so heartwarming when you save a life and see an animal that is grateful to you," she says.

"They can't say anything, but how they look at you shows gratitude for being saved."

READ MORE  Police advance on demonstrators protesting the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, May 30, 2020. (photo: Scott Olson/Getty)

Police advance on demonstrators protesting the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, May 30, 2020. (photo: Scott Olson/Getty)

Justin Stetson, 34, faces a felony count of third-degree assault in connection with the May 30, 2020, beating of Jaleel Stallings and up to five years in prison if convicted.

Justin Stetson, 34, faces one felony count of third-degree assault in connection with the May 30, 2020, beating of Jaleel Stallings. He would face up to five years in prison if convicted.

It wasn’t immediately clear whether Stetson has an attorney. A Minneapolis city attorney who represented him and other officers in a federal lawsuit Stallings filed against them didn’t immediately respond to an email inquiring if she knew if Stetson has a criminal defense attorney.

According to the criminal complaint, Stetson was among a group of officers enforcing a city-wide curfew that night when his group spotted four people in a parking lot. One of them was Stallings.

The officers opened fire on the group with rubber bullets. One hit Stallings in the chest, causing him severe pain, according to the complaint. Stallings fired three live rounds at the officers’ unmarked van but didn’t hurt anyone.

He argued that he thought civilians had attacked him, and he fired in self-defense. He was acquitted in September 2021 of a second-degree attempted murder charge related to that shooting.

The officers rushed the civilians. When Stallings realized they were police, he dropped his gun and lay on the ground. Stetson then kicked him in the face and in the head, according to the complaint. He also punched Stallings multiple times and slammed his head into the pavement, the complaint said.

Stetson went on hitting him even after he had obeyed Stetson’s command to place his hands behind his back. A sergeant finally told Stetson to stop.

Stallings suffered a fracture of his eye bone.

Ian Adams, a former law enforcement officer who is now a criminology professor at the University of South Carolina, reviewed the case and concluded that Stetson’s use of force was unreasonable and excessive and “violated the most basic norms of policing,” the complaint said.

The complaint noted that Stetson had been a Minneapolis police officer since at least 2011 and had received about 1,200 hours of training, including training on how to de-escalate situations.

The city of Minneapolis paid Stallings $1.5 million this past May to settle his federal lawsuit. He alleged Stetson and other officers violated his constitutional rights.

READ MORE  Trump supporters on the lawn of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., January 6, 2021. (photo: Lenin Nolly/Reuters)

Trump supporters on the lawn of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., January 6, 2021. (photo: Lenin Nolly/Reuters)

Republican attempts to minimize far-right violence hampers government efforts to combat the threat, extremism analysts say

Nevertheless, at a congressional hearing this month on the threat of violent white supremacy, two Republican lawmakers cherry-picked a word in the Buffalo killer’s screed — “socialist” — to cast him as a radical leftist. They did not note that the shooter was referring to National Socialism, the ideology of the German Nazi Party, as Democrats and witnesses on the panel pointedly clarified.

“Any sober look” at the Buffalo shooter’s hate-filled manifesto, Oren Segal of the Anti-Defamation League told the lawmakers, “would recognize that attack as clearly a white-supremacist attack.”

The exchange shows the tricky role of language in the politically charged struggle over how to talk about domestic terrorism. Republican leaders portray the far left and far right as equally dangerous, an assertion contradicted by White House assessments that “the most persistent and lethal threats” to the country come from the violent right.

But “far right” also is an imperfect term, analysts say, and does not capture the complex ideologies, including some that overlap with the anarchist left, that have fueled recent attacks.

That fuzziness leaves room for bad-faith arguments and misinformation, miring an urgent threat in partisan point-scoring. Terrorism researchers said they had hoped that rising political violence culminating in the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol would jolt leaders into action. Instead, they say, efforts to address violent extremism have stalled over semantics and an eagerness to blame “the other side.”

This month, just before the House Jan. 6 committee released a final report on its probe of the Capitol insurrection, Republican lawmakers released their own version, which blamed Democratic leaders for security lapses and did not mention President Donald Trump’s fiery remarks or that Trump waited hours before urging the mob to leave.

Also this month, as first reported by Roll Call, lawmakers who wrote the final defense authorization bill “deleted or diluted” all seven House-passed provisions related to extremism in the U.S. military or broader society.

Outside the government, extremism researchers are increasingly vocal with claims that the Department of Homeland Security is blocking their federally funded projects out of unspecified privacy concerns they believe are linked in part to the politics around domestic terrorism.

Analysts predict an even more contested discourse once Republicans assume control of the House. They expect that GOP leaders will mute domestic-terrorism talk and steer the focus of inquiries toward “radical leftists,” who are nowhere near as lethal or active, according to attack data.

Heidi Beirich, co-founder of the nonprofit Global Project Against Hate and Extremism, said Republicans not only “try to bury the problem” but have fielded dozens of candidates who ran on platforms that invoked far-right, conspiratorial ideas such as the engineered “replacement” of White people, a theme expressed by men accused in the mass killings of Jewish worshipers at a Pittsburgh synagogue and Latinos at a Walmart in El Paso, among other attacks.

An Anti-Defamation League report, “Extremism on the Ballot,” counted at least a dozen candidates in the 2022 midterms with explicit ties to extremist movements, and around 100 others had been linked in varying degrees to extremist ideologies. They were almost exclusively Republicans.

“The party itself has candidates who are running on the same idea as what inspires domestic terrorism,” Beirich said with an incredulous chuckle. “I’m laughing because it’s hard to believe I’m saying this. There will be no will for Republicans to look at any of this. Once again, terrorism — just like January 6 — ends up being a completely partisan issue that stymies any efforts to address it.”

Republicans generally have opposed government-funded attempts to study domestic terrorism, joined by influential right-wing outlets in portraying the issue as a “thought police” exercise designed to vilify conservatives and, ultimately, disarm gun-owning Americans.

GOP officials also complain of a double standard, arguing that mainstream news outlets and Democratic leaders disproportionately focus on the right-wing threat and give a pass to “antifa rioters” and left-wing extremists such as the gunman who shot six people, including then-House Majority Whip Steve Scalise (R-La.), during a congressional baseball practice in 2017.

One striking example of how deeply the partisan divide runs on this issue was in Republican reactions to the news that a violent attacker targeting House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) had bludgeoned her husband, Paul Pelosi, with a hammer, according to authorities.

Some Republicans, including Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin and Rep. Andy Biggs of Arizona, were criticized for remarks seen as minimizing or mocking the assault. Influential right-wing figures tried to portray the suspect as a leftist because he had a history of dabbling in all sorts of extremism before becoming fixated on Democrats, Nancy Pelosi in particular, according to court documents and a social media trail. Within the GOP, there was little appetite for introspection on how the party’s relentless demonization of Pelosi might have contributed to the mobilization of a violent fringe.

Pelosi has described Republican reactions as “disgraceful.”

Language has always played a fraught role in debates over which ideologies are labeled threats to national security. After the 9/11 attacks, Muslim advocacy groups spent years protesting that counterterrorism officials used stigmatizing rhetoric that led to civil-liberties violations and Islamophobic backlash.

Republican demands for more-nuanced language on domestic terrorism emerged as the threat evolved and FBI attack data made clear that the biggest threat now comes from far-right movements such as those involved in the Capitol attack. Soon, the surveillance and profiling that were staples of the government’s fight against Islamist militancy — and which were broadly supported by Republican leaders — were reframed in conservative outlets as part of an unconstitutional witch hunt against Christian “patriots.”

During the Trump years, Republicans typically avoided dwelling on the far-right threat unless far-left “antifa” militants were mentioned as equally concerning, a notion that took hold across wide swaths of the right.

In early 2019, during the Trump administration, Elizabeth Neumann was serving as a senior DHS counterterrorism official. A gunman had just attacked the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, Neumann recalled, and the FBI and National Counterterrorism Center began rethinking domestic-terrorism strategies.

More than six months later, “well after a whole bunch of other attacks had happened,” Neumann said, officials finally arranged a conference on domestic threats. When the teams briefed her on the work, Neumann said, she was floored to hear a fixation on definitions — finding a balance between categories that were precise enough for researchers and not too polarizing for politicians.

“I felt like we were so focused on definitions that we were kind of missing the point that we were not organized or structured [and didn’t] have any programs that are actually going to address the threat,” said Neumann, now chief strategy officer at Moonshot, a company that combats online extremism.

In that era, federal authorities started using phrases such as “RMVE,” for “racially motivated violent extremism,” which was criticized as a euphemism for deadly white supremacists. The term was also vague enough that it allowed officials pushing a “both sides” agenda to introduce a sub-category on “black identity violent extremism,” drawing outrage from civil rights groups who called it an attempt to equate Black Lives Matter protesters with far-right militants.

At a hearing in 2019, in response to questioning by Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.), FBI Director Christopher A. Wray said the controversial category had been retired: “We don’t use the term ‘black identity extremism’ anymore.”

“Despite this announcement, serious concerns about the FBI’s obfuscation of the threat posed by white supremacists remain,” Booker said in a statement at the time, noting that the majority of domestic terrorist attacks in recent years had come from far-right assailants. He added, “The FBI should not be in the business of using phrases and categories that confuses this point.”

The change in administration when Joe Biden came to office introduced yet another round of confusion for researchers trying to keep up with the federal government’s shifting, acronym-filled language on domestic terrorism.

They had just gotten used to calling the DHS office overseeing counterextremism strategies the “TVTP,” for Targeted Violence and Terrorism Prevention, when it was re-branded in 2021 as CP3, the Center for Prevention Programs and Partnerships. The Trump administration’s labels such as “anarcho-Marxist violent revolutionaries” were retired. Ditto for “ethno-violence,” a softening of “white-supremacist violence,” analysts recalled.

But there was also an acknowledgment in and out of government that the old left-right terrorism spectrum was outdated, incapable of reflecting how online radicalization grabs from various ideologies and defies simple categorization. White-supremacist attackers sometimes espouse environmental extremism or misogynistic incel rhetoric. Anti-government “boogaloo” militants march alongside black-nationalist gun groups. Neo-Nazis invoke language and tactics from Islamist militants.

That blending of ideologies led to terms such as “salad-bar extremism” or “fringe fluidity” entering the lexicon of domestic terrorism studies. But where analysts saw nuance that better captures the complexity of attacks, conservative influencers saw wiggle room to further confuse public understanding of the problem and its links to right-wing politics.

The lingering confusion has hampered even DHS’s ability to identify red flags within department ranks, according to a 2022 DHS report on insider threats that found information gaps based on “a lack of an official definition of ‘domestic violence extremist’” or guidance on what constitutes extremist activity.

“It’s very much a contextual term that’s in the eye of the beholder,” Neumann said. “It’s kind of funny — we’ve now, for 21 years, spent all sorts of money on countering violent extremism and yet we don’t have a definition for what that is.”

If the government’s classifications are confusing to its own professional analysts, they are probably indecipherable to Americans trying to understand the rise in extremist violence. “RMVE” is still in use, as a subset of “DVE,” or “domestic violent extremism.” And “domestic” refers to, say, armed anti-government groups or militant anarchists, not to be confused with “homegrown,” which is reserved for U.S. operatives of foreign militant groups such as the Islamic State.

“It sounds like gobbledygook,” Beirich said. “For an average person, you have no idea what they’re talking about. The definitions keep shifting.”

In its first report on the international far-right threat, the United Nations in October introduced yet another category, for attacks fueled by xenophobia, racism and other forms of intolerance, or in the name of religion or belief — XRIRB, an acronym that has “broken my brain,” tweeted Anna Meier, a U.K.-based scholar of white-supremacist violence.

Cynthia Miller-Idriss, who leads the Polarization and Extremism Research and Innovation Lab (PERIL) at American University, said: “All these labels have been attempts not to use the words ‘right’ or ‘left’ in any of this. But then it gets confusing because they’re using these awful acronyms, and no one’s using the same ones. It just becomes this alphabet soup.”

In recent months, the Biden administration has used the catchall “hate-fueled violence,” which encompasses bias-motivated crimes as well as mass-casualty terrorist attacks. Miller-Idriss praised the term for its inclusivity but said she worries that it, too, could be used to avoid the tougher conversation that unequivocally recognizes far-right movements — namely neo-Nazi groups and armed anti-government groups — as the main drivers of political violence.

“There are deep-rooted things like misogyny, antisemitism and different forms of racism that cut across the spectrum,” Miller-Idriss said. “However, the organized terroristic domestic extremist violence is coming from the far right.”

READ MORE  The Colorado River in Fruita, Colorado. The river system is in a state of collapse hastened by climate change and a crisis of management. (photo: Matt McClain/Washington Post)

The Colorado River in Fruita, Colorado. The river system is in a state of collapse hastened by climate change and a crisis of management. (photo: Matt McClain/Washington Post)

Diminished by climate change and overuse, the river can no longer provide the water states try to take from it.

The Uncompahgre Valley, stretching 34 miles from Delta through the town of Montrose, is, and always has been, an arid place. Most of the water comes from the Gunnison River, a major tributary of the Colorado, which courses out of the peaks of the Elk Range through the cavernous and sun-starved depths of the Black Canyon, one rocky and inaccessible valley to the east. In 1903, the federal government backed a plan hatched by Uncompahgre farmers to breach the ridge with an enormous tunnel and then in the 1960s to build one of Colorado’s largest reservoirs above the Black Canyon called Blue Mesa. Now that tunnel feeds a neural system of water: 782 miles worth of successively smaller canals and then dirt ditches, laterals and drains that turn 83,000 Western Colorado acres into farmland. Today, the farm association in this valley is one of the largest single users of Colorado River water outside of California.

I came to this place because the Colorado River system is in a state of collapse. It is a collapse hastened by climate change but also a crisis of management. In 1922, the seven states in the river basin signed a compact splitting the Colorado equally between its upper and lower halves; later, they promised additional water to Mexico, too. Near the middle, they put Lake Powell, a reserve for the northern states, and Lake Mead, a storage node for the south. Over time, as an overheating environment has collided with overuse, the lower half — primarily Arizona and California — has taken its water as if everything were normal, straining both the logic and the legal interpretations of the compact. They have also drawn extra releases from Lake Powell, effectively borrowing straight out of whatever meager reserves the Upper Basin has managed to save there.

This much has become a matter of great, vitriolic dispute. What is undeniable is that the river flows as a much-diminished version of its historical might. When the original compact gave each half the rights to 7.5 million acre-feet of water, the river is estimated to have flowed with as much as 18 million acre-feet each year. Over the 20th century, it averaged closer to 15. Over the past two decades, the flow has dropped to a little more than 12. In recent years, it has trickled at times with as little as 8.5. All the while the Lower Basin deliveries have remained roughly the same. And those reservoirs? They are fast becoming obsolete. Now the states must finally face the consequential question of which regions will make their sacrifice first. There are few places that reveal how difficult it will be to arrive at an answer than the Western Slope of Colorado.

In Montrose, I found the manager of the Uncompahgre Valley Water Users Association, Steve Pope, in his office atop the squeaky stairs of the same Foursquare that the group had built at the turn of the last century. Pope, bald, with a trimmed white beard, sat amid stacks of plat maps and paper diagrams of the canals, surrounded by LCD screens with spreadsheets marking volumes of water and their destinations. On the wall, a historic map showed the farms, wedged between the Uncompahgre River and where it joins the Gunnison in Delta, before descending to their confluence with the Colorado in Grand Junction. “I’m sorry for the mess,” he said, plowing loose papers aside.

What Pope wanted to impress upon me most despite the enormousness of the infrastructure all around the valley was that in the Upper Basin of the Colorado River system, there are no mammoth dams that can simply be opened to meter out a steady release of water. Here, only natural precipitation and temperature dictate how much is available. Conservation isn’t a management decision, he said. It was forced upon them by the hydrological conditions of the moment. The average amount of water flowing in the system has dropped by nearly 20%. The snowpack melts and evaporates faster than it used to, and the rainfall is unpredictable. In fact, the Colorado River District, an influential water conservancy for the western part of the state, had described its negotiating position with the Lower Basin states by claiming Colorado has already conserved about 28% of its water by making do with the recent conditions brought by drought.

You get what you get, Pope tells me, and for 15 of the past 20 years, unlike the farmers in California and Arizona, the people in this valley have gotten less than what they are due. “We don’t have that luxury of just making a phone call and having water show up,” he said, not veiling his contempt for the Lower Basin states’ reliance on lakes Mead and Powell. “We’ve not been insulated from this climate change by having a big reservoir above our heads.”

He didn’t have to point further back than the previous winter. In 2021, the rain and snow fell heavily across the Rocky Mountains and the plateau of the Grand Mesa, almost as if it were normal times. Precipitation was 80% of average — not bad in the midst of an epochal drought. But little made it into the Colorado River. Instead, soils parched by the lack of rain and rising temperatures soaked up every ounce of moisture. By the time water reached the rivers around Montrose and then the gauges above Lake Powell, the flow was less than 30% of normal. The Upper Basin states used just 3.5 million acre-feet last year, less than half their legal right under the 1922 compact. The Lower Basin states took nearly their full amount, 7 million acre-feet.

All of this matters now not just because the river, an unwieldy network of human-controlled plumbing, is approaching a threshold where it could become inoperable, but because much of the recent legal basis for the system is about to dissolve. In 2026, the Interim Guidelines the states rely on, a Drought Contingency Plan and agreements with Mexico will all expire. At the very least, this will require new agreements. It also demands a new way of thinking that matches the reality of the heating climate and the scale of human need. But before that can happen, the states will need to restore something that has become even more scarce than the water: trust.

The northern states see California and Arizona reveling in profligate use, made possible by the anachronistic rules of the compact that effectively promise them water when others have none. It’s enabled by the mechanistic controls at the Hoover Dam, which releases the same steady flow no matter how little snow falls across the Rocky Mountains. California flood-irrigates alfalfa crops destined for cattle markets in the Middle East, while Arizona takes water it does not need and pumps it underground to build up its own reserves. In 2018, an Arizona water agency admitted it was gaming the timing of its orders to avoid rations from the river (though it characterized the moves as smart use of the rules). In 2021, in a sign of the growing wariness, at least one Colorado water official alleged California was repeating the scheme. California water officials say this is a misunderstanding. Yet to this day, because California holds the most senior legal rights on the river, the state has avoided having a single gallon of reductions imposed on it.

By this spring, Lake Powell shrank to 24% of its capacity, its lowest levels since the reservoir filled in the 1960s. Cathedral-like sandstone canyons were resurrected, and sunlight reached the silt-clogged floors for the first time in generations. The Glen Canyon Dam itself towered more than 150 feet above the waterline. The water was just a few dozen feet above the last intake pipe that feeds the hydropower generators. If it dropped much lower, the system would no longer be able to produce the power it distributes across six states. After that, it would approach the point where no water at all could flow into the Grand Canyon and further downstream. All the savings that the Upper Basin states had banked there were as good as gone.

In Western Colorado, meanwhile, people have been suffering. South of the Uncompahgre Valley, the Ute Mountain Ute tribe subsists off agriculture, but over the past 12 months it has seen its water deliveries cut by 90%; the tribe laid off half of its farmworkers. McPhee Reservoir, near the town of Cortez, has teetered on failure, and other communities in Southwestern Colorado that also depend on it have been rationed to 10% of their normal water.

Across the Upper Basin, the small reservoirs that provide the region’s only buffer against bad years are also emptying out. Flaming Gorge, on the Wyoming-Utah border, is the largest, and it is 68% full. The second largest, Navajo Reservoir in New Mexico, is at 50% of its capacity. Blue Mesa Reservoir, on the Gunnison, is just 34% full. Each represents savings accounts that have been slowly pilfered to supplement Lake Powell as it declines, preserving the federal government’s ability to generate power there and obscuring the scope of the losses. Last summer, facing the latest emergency at the Glen Canyon Dam, the Department of Interior ordered huge releases from Flaming Gorge, Blue Mesa and other Upper Basin reservoirs. At Blue Mesa, the water levels dropped 8 feet in a matter of days, and boaters there were given a little more than a week to get their equipment off the water. Soon after, the reservoir’s marinas, which are vital to that part of Colorado’s summer economy, closed. They did not reopen in 2022.

As the Blue Mesa Reservoir was being emptied last fall, Steve Pope kept the Gunnison Tunnel open at its full capacity, diverting as much water as he possibly could. He says this was legal, well within his water rights and normal practice, and the state’s chief engineer agrees. Pope’s water is accounted for out of another reservoir higher in the system. But in the twin takings, it’s hard not to see the bare-knuckled competition between urgent needs. Over the past few years, as water has become scarcer and conservation more important, Uncompahgre Valley water diversions from the Gunnison River have remained steady and at times even increased. The growing season has gotten longer and the alternative sources, including the Uncompahgre River, less reliable. And Pope leans more than ever on the Gunnison to maintain his 3,500 shareholders’ supply. “Oh, we are taking it,” he told me, “and there’s still just not enough.”

On June 14, Camille Touton, the commissioner of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the Department of Interior division that runs Western water infrastructure, testified before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources and delivered a stunning ultimatum: Western states had 60 days to figure out how to conserve as much as 4 million acre-feet of “additional” water from the Colorado River or the federal government would, acting unilaterally, do it for them. The West’s system of water rights, which guarantees the greatest amount of water to the settlers who arrived in the West and claimed it first, has been a sacrosanct pillar of law and states’ rights both — and so her statement came as a shock.

Would the department impose restrictions “without regard to river priority?” Mark Kelly,, the Democratic senator from Arizona, asked her.

“Yes,” Touton responded.

For Colorado, this was tantamount to a declaration of war. “The feds have no ability to restrict our state decree and privately owned ditches,” the general manager of the Colorado River District, Andy Mueller, told me. “They can’t go after that.” Mueller watches over much of the state.Pope faces different stakes. His system depends on the tunnel, a federal project, and his water rights are technically leased from the Bureau of Reclamation, too. Touton’s threat raised the possibility that she could shut the Uncompahgre Valley’s water off. Even if it was legal, the demands seemed fundamentally unfair to Pope. “The first steps need to come in the Lower Basin,” he insisted.

Each state retreated to its corners, where they remain. The 60-day deadline came and went, with no commitments toward any specific reductions in water use and no consequences. The Bureau of Reclamation has since set a new deadline: Jan. 31. Touton, who has publicly said little since her testimony to Congress, declined to be interviewed for this story. In October, California finally offered a plan to surrender roughly 9% of the water it used, albeit with expensive conditions. Some Colorado officials dismissed the gesture as a non-starter. Ever since, Colorado has become more defiant, enacting policies that seem aimed at defending the water the state already has — perhaps even its right to use more.

For one, Colorado has long had to contend with the inefficiencies that come with a “use it or lose it” culture. State water law threatens to confiscate water rights that don’t get utilized, so landowners have long maximized the water they put on their fields just to prove up their long-term standing in the system. This same reflexive instinct is now evident among policymakers and water managers across the state, as they seek to establish the baseline for where negotiated cuts might begin. Would cuts be imposed by the federal government based on Pope’s full allocation of water or on the lesser amount with which he’s been forced to make do? Would the proportion be adjusted down in a year with no snow? “We don’t have a starting point,” he told me. And so the higher the use now, the more affordable the conservation later.

Colorado and other Upper Basin states have also long hid behind the complexity of accurately accounting for their water among infinite tributaries and interconnected soils. The state’s ranchers like to say their water is recycled five times over, because water poured over fields in one place invariably seeps underground down to the next. In the Uncompahgre Valley, it can take months for the land at its tail to dry out after ditches that flood the head of the valley are turned off. The measure of what’s been consumed and what has transpired from plants or been absorbed by soils is frustratingly elusive. That, too, leaves the final number open to argument and interpretation.

All the while, the Upper Basin states are all attempting to store more water within their boundaries. Colorado has at least 10 new dams and reservoirs either being built or planned. Across the Upper Basin, an additional 15 projects are being considered, including Utah’s audacious $2.4 billion plan to run a new pipeline from Lake Powell, which would allow it to transport something closer to its full legal right to Colorado River water to its growing southern cities. Some of these projects are aimed at securing existing water and making its timing more predictable. But they are also part of the Upper Colorado River Commission’s vision to expand the Upper Basin states’ Colorado River usage to 5.4 million acre-feet a year by 2060.

It is fair to say few people in the state are trying hard to send more of their water downstream. In our conversation, Mueller would not offer any specific conservation savings Colorado might make. The state’s chief engineer and director of its Division of Water Resources, Kevin Rein, who oversees water rights, made a similar sentiment clear to the Colorado River District board last July. “There’s nothing telling me that I should encourage people to conserve,” Rein said. “It’s a public resource. It’s a property right. It’s part of our economy.”

In November, Democratic Gov. Jared Polis proposed the creation of a new state task force that would help him capture every drop of water it can before it crosses the state line. It would direct money and staff to make Colorado’s water governance more sophisticated, defensive and influential.

I called Polis’ chief water confidante, Rebecca Mitchell, who is also the director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board and the state’s representative on the Upper Colorado River Commission. If the mood was set by the idea that California was taking too much from the river, Mitchell thought that it had shifted now to a more personal grievance — they are taking from us.

Last month, Mitchell flew to California for a tour of its large irrigation districts. She stood beside a wide canal brimming with more water than ever flows through the Uncompahgre River, and the executive of the farming company beside her explained that he uses whatever he wants because he holds the highest priority rights to the water. She thought about the Ute Mountain Ute communities and the ranchers of Cortez: “It was like: ‘Wouldn’t we love to be able to count on something? Wouldn’t we love to be feel so entitled that no matter what, we get what we get?’” she told me.

What if Touton followed through, curtailing Colorado’s water? I asked. Mitchell’s voice steadied, and then she essentially leveled a threat. “We would be very responsive. I’m not saying that in a positive way,” she said. “I think everybody that’s about to go through pain wants others to feel pain also.”

Here’s the terrible truth: There is no such thing as a return to normal on the Colorado River, or to anything that resembles the volumes of water its users are accustomed to taking from it. With each degree Celsius of warming to come, modelers estimate that the river’s flow will decrease further, by an additional 9%. At current rates of global warming, the basin is likely to sustain at least an additional 18% drop in its water supplies over the next several decades, if not far more. Pain, as Mitchell puts it, is inevitable.

The thing about 4 million acre-feet of cuts is that it’s merely the amount already gone, an adjustment that should have been made 20 years ago. Colorado’s argument makes sense on paper and perhaps through the lens of fairness. But the motivation behind the decades of delay was to protect against the very argument that is unfolding now — that the reductions should be split equally, and that they may one day be imposed against the Upper Basin’s will. It was to preserve the northern states’ inalienable birthright to growth, the promise made to them 100 years ago. At some point, though, circumstances change, and a century-old promise, unfulfilled, might no longer be worth much at all. Meanwhile, the politics of holding out are colliding with climate change in a terrifying crash, because while the parties fight, the supply continues to dwindle.

Recently, Brad Udall, a leading and longtime analyst of the Colorado River and now a senior water and climate scientist at Colorado State University, teamed with colleagues to game out what they thought it would take to bring the river and the twin reservoirs of Mead and Powell into balance. Their findings, published in July in the journal Science, show that stability could be within reach but will require sacrifice.