Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The Inflation Reduction Act finally offers a chance for widespread change.

So far, the climate debate has gone on mostly in people’s heads and hearts. It took thirty years to get elected leaders to take it seriously: first, to just get them to say that the planet was warming, and then to allow that humans were causing it. But this year Congress finally passed serious legislation—the Inflation Reduction Act—that allocates hundreds of billions of dollars to the task of transforming the nation so that it burns far less fossil fuel. So now the battle moves from hearts and heads to houses. “Emissions come from physical things,” Tom Steyer, the businessman and investment-firm manager, who, after a Presidential run in 2020, is focussing on investing in climate solutions, told me. “Emissions come from buildings, from power plants, from cars, from stuff you can touch. It’s not like information technology, which is infinitely replicable. This is one object at a time.”

So the big question is: How do you move from exhortation and demonstration to execution and deployment? Engineers have provided relatively cheap and incredibly elegant technology: the most cost-effective way to produce power is to point a sheet of glass at the sun. The federal government is providing the biggest infusion of clean-money capital in its history. But can it actually be done? Or is it simply too big a task, especially in the face of ongoing opposition from the fossil-fuel industry?

“So many of us are tired,” Leah Stokes, an energy expert at the University of California, Santa Barbara, told me. Stokes was an architect of key parts of the I.R.A. during its tortured twenty-month trek through the Senate; at one point, she found herself drafting bill text while in a neonatal intensive-care unit, with her newborn twins. “But we’re at an inflection point in the fight against dirty energy. We can solve the climate crisis.”

“Now is the time for the doers, the implementers, the people ready to roll up their sleeves and dig,” Donnel Baird, the founder and C.E.O. of BlocPower, a heat-pump startup, said. Even before the I.R.A. passed, Baird, the son of Guyanese immigrants who once heated their home in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, by turning on the gas oven and leaving the door open, had raised a hundred million dollars to work on electrifying whole communities across the country. “If we can green a building, we can green a block,” he told me. “If we can green a block, we can green a neighborhood, and a city. So we should do that, and show everyone it can be done.”

“We’re in head-down, drive-deployment mode,” Billy Parish told me last month. Parish runs a company, Mosaic, that has raised half a billion dollars in financing to become one of the largest lenders to solar projects in the country; it is one of the companies, along with Airbnb and the real-estate broker Redfin, that last month joined the White House to announce plans for educating homeowners on how to access I.R.A. money. “There’s so much clean energy that wants to be built,” he said.

These people have been working on the climate crisis for years. (I first met Parish a few years after he dropped out of Yale, in 2002, to start the Energy Action Coalition, one of the first big campus climate-action groups in this country; Steyer and I have long been involved in campaigns against pipelines and investing in fossil fuels.) But, for all their enthusiasm, they are worried. “If we don’t get implementation right, then it’s catastrophic for carbon, and it also teaches politicians it’s not a winning issue,” Stokes told me. Baird advised the Department of Energy on the creation of green jobs under the Obama Administration, which also set aside money—albeit, considerably less—for renewable energy. “The part I worked on was greening buildings, and we had $6.5 billion, and that attracted another ninety billion dollars in private-sector capital,” he told me. “And, even with that, we couldn’t really pull it off. We weren’t able to invest the private capital. There’s still a ton of work to be done implementing the I.R.A., and if we don’t do it well the politicians will say, ‘We tried, this didn’t work, and we don’t know why.’ And it will be two or three times harder next time.” Parish warned, “There’s a more coördinated effort against clean energy now. It’s still very popular, but it’s becoming more polarized.”

The fear is not that nothing will get done; it’s that not enough will get done, because meeting the climate challenge means, essentially, changing everything. And in America that includes changing a hundred and forty million homes. Essentially, that means replacing furnaces, gas burners, and internal-combustion engines with heat pumps, induction cooktops, and electric cars. “We estimate that there are a billion machines in American homes that have to be switched out,” Ari Matusiak, the C.E.O. of Rewiring America, a nonprofit that is educating communities about electrification funds that are available to them through the I.R.A., told me. Success depends on making sure that those machines are clean. “The market won’t do it on its own, because the market of goods and labor—the market of machines—is a fossil-fuel market,” Matusiak said. “My house has gas pipes in it. If my furnace goes out, or my water heater goes out, the contractor is not going to sell me a heat pump, even though it’s better. They’re going to sell me a replacement for what I already have.”

The scale of the task somehow looks more enormous the closer you get to the ground. Consider Boston, the home town of Varshini Prakash, the executive director of the Sunrise Movement, whose push for the Green New Deal was instrumental in getting the I.R.A. passed, and the city whose mayor, Michelle Wu, has been as outspoken an advocate of environmental politics as any civic leader in the country. And, as of next month, the governor of Massachusetts will be Maura Healey, who made her name, in part, as the state’s attorney general, by suing the fossil-fuel industry for having misled the public about climate change. In 2020, Massachusetts voted for Biden by better than two to one; Boston did by nearly five to one. But Boston has almost three hundred thousand housing units, and Massachusetts, in all, has three million. And even getting new construction to go electric is a trial—as attorney general, Healey had no choice but to rule that state law prohibited town ordinances from banning gas hookups in new buildings. And getting homeowners (and landlords) to switch out gas-powered appliances is just part of the problem. You also have to come up with a stream of clean electricity—solar panels and wind turbines and batteries—to power the new electric ones.

A renewable-energy engineer based in Massachusetts pointed out to me that his state needs close to ten gigawatts’ worth of electrical power to meet current demand. Construction on the state’s first big offshore wind farm, Vineyard Wind, is just now beginning, after a decade of bureaucratic battles, and when it’s done it will supply less than half a gigawatt of power. “Can Massachusetts really build the needed twenty-five offshore wind farms in a decade?” he asked. At least Massachusetts has something. Sam Evans-Brown, who heads Clean Energy New Hampshire, says that his state has just five per cent of the installed solar capacity that Massachusetts has. “Renewables are cheap, and everyone wants them, but there are big gaps in our ability to get it done,” he told me.

Some of those gaps are of the kind that come with any big new industry challenge. For instance, Rewiring America estimates that the country needs a million new electricians just to do the new wiring that will be needed. According to Evans-Brown, the largest solar company in New Hampshire has “taken their entire marketing team and said, ‘Stop selling solar panels, they’re selling themselves.’ Instead, the whole marketing team is now devoted to recruiting electricians.” That shouldn’t be an impossible task. Evans-Brown said that, the previous weekend, he and his wife, Aubrey Nelson, had been in the northern part of the state, where she spoke “with a bunch of kids from a technical high school, working on a house being renovated. They were doing blower-door tests, pulling out the thermal cameras to see where the house was leaking. And the teacher was saying, ‘These dudes are going to be able to make six figures working construction.’ That’s a success story, but it’s not getting out there enough.” Eugene Kirpichov, who runs a new nonprofit called Work on Climate, points out the scale of the challenge. “Compare this to a mainstream industry like software,” he said. “Every school teaches it, everybody knows who the main employers are, and sees it as cool. There are thousands of bootcamps, tens of thousands of recruiting agencies.” At the moment, he says, “There are tens of thousands people in our climate-jobs community, while we need millions.”

There are, of course, other obstacles to working on this scale. Some thirty-five per cent of American homes are rental units, and they usually come with what economists call “split incentives.” As the veteran energy analyst Hal Harvey and the former Times climate reporter Justin Gillis explain in “The Big Fix,” an important book published earlier this year, “The people who design and build buildings almost never occupy them, which means they are not going to pay the utility bills,” something that applies to homes as well as to apartments. “If the architect can save time by not thinking through solar heat loads or overhang angles, she will. If the developer can save money by skipping insulation, which is invisible to potential buyers, he may do just that. And if the builder is not fastidious about insulating the heating ducts, buried deep in the walls, who is to know?”

A conscientious landlord can overcome some of that conundrum. Evans-Brown and Nelson own a small rental unit in Concord, the state capitol, and they just took over their tenants’ energy bills, which means that the incentive to make the energy supply cleaner and more efficient is now theirs alone. But, when they went to install a heat pump, they immediately ran into another problem: big bottlenecks in the clean-energy supply chain. He told me, “We looked to install a whole-house heat pump, which was partly about saving carbon, and partly about me not wanting to lug the window A.C. units up every summer.” (Heat pumps, despite their name, also cool homes.) They had hoped to install it by June, but no condenser units were available, so it didn’t happen until October. Tight supplies and labor force and heightened demand all mean that “I believe that we’re in a period of ‘greenflation,’ when contractors can charge more than they should,” Evans-Brown said. “Right now, they can quote thirty per cent above what they should, because they only have to land one job in five to fill their book, and I worry about that, too. There are going to be some consumer horror stories that get shared.”

Such problems mostly get filed under “growing pains,” and financial incentive eventually overcomes them: if there’s enough demand for electricians, community colleges will start producing them; and if there’s enough demand for condensers, factories will start producing them. When economists talk about the I.R.A. “priming the pump,” this is what they mean.

But, beyond inertia, vested interest also presents a challenge. According to an analysis of World Bank data conducted earlier this year, the oil industry has averaged the equivalent of $3.2 billion, adjusting for inflation, in profits a day for the past fifty years. That’s both a prize worth fighting for and a war chest ample enough to make the fight prolonged and bitter. And we don’t have much time—the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says that the United States must cut emissions in half by 2030 in order to keep on track to meet the targets set in the 2016 Paris climate accords. “We’re in a knockdown, drag-out fight,” Stokes told me. “Because our opponents, every day they delay us, they make money.”

So the battle will be fought at the global level. At last month’s COP27 climate talks, in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, there were six hundred and thirty-six official fossil-fuel lobbyists in attendance, and the largest national delegation—more than a thousand people—came from the United Arab Emirates, which produces more oil per capita than all other countries except for Kuwait and Qatar, and which will host next year’s climate summit. Saudi Arabia and China tried to block any mention of phasing out fossil fuels in the final text of this year’s agreement; a recent analysis of academic research databases revealed that Saudi Aramco, the state-owned petroleum company, had financed “almost 500 studies over the past five years, including research aimed at keeping gasoline cars competitive or casting doubt on electric vehicles.”

And the battle will be fought at the national level. In this country, even before the G.O.P. won back control of the House in the midterms, Eric Lipton reported in the Times, fossil-fuel lobbyists were boasting that they could undercut much of the I.R.A. funding for energy transitions. The head lobbyist of the American Gas Association told an industry conference in Minneapolis that Republicans are “champing at the bit to do some oversight to try to change the law where they can.” They aim, for example, gut a $4.5-billion section of the bill that would give rebates worth as much as fourteen thousand dollars to low- and moderate-income households that install heat pumps, induction stoves, or other appliances that use electricity instead of gas. Lipton notes that “there is almost glee” in the lobbyists’ voices “when they discuss the possibility of helping draft questions for Biden Administration officials, such as Interior Secretary Deb Haaland.” According to Kathleen Sgamma, the president of the Western Energy Alliance, an oil-industry trade association, Haaland “has managed to dodge questions when she’s before a Democrat committee chair. I don’t think she’ll get that same treatment when the Republicans are in charge.”

The most damaging campaigns, however, are aimed at the local level—at the places where those millions of houses sit, or where those arrays of solar panels will have to be built. BlocPower’s Baird told me, “I just spent a week with state energy officers in a hotel in Florida for a conference. There’s energy and excitement about the I.R.A. money, but there’s more confusion and concern. And more than that, risk aversion.”

If you want to see this fight playing out in all its hard particulars, you can pick almost any state. North Carolina, for example, is a purplish state that’s home to a powerful utility, Duke Energy, but also to a lot of sunshine, and a vibrant small-scale-solar legacy. Tyler H. Norris, who grew up in the mountains twenty miles southeast of Asheville, earned a degree in public policy at Stanford and, when he was twenty-three, started working for the Obama Administration, advising on clean-energy investments initiated by the recovery plan for the 2008 financial crisis. In 2017, Norris returned to North Carolina, to help run a division of Cypress Creek Renewables, a solar-development company.

Five years later, the state’s Democratic governor managed to pass what Norris called “the first ambitious decarbonization mandate in the Southeast.” Under the legislation, statewide emissions are supposed to drop seventy per cent by 2030, and to net zero by 2050. “It kicked off a new wave of development, and you’d think the I.R.A. and its money would be gasoline on that spark,” Norris said. But the law also gives “big amounts of discretion” to the state’s Utilities Commission, and their plan remains unclear. Duke Energy “has been pretty oppositional to accelerating the pace of solar deployment,” Norris said, and they’ve “proposed a hard, fixed cap on the amount of renewables that can be added in any given year.” According to Norris, under those rules, the state can’t add more solar capacity than it did in the twenty-tens until 2028.

Duke, for its part, is reportedly hoping to incorporate small modular nuclear reactors in time to meet much of North Carolina’s decarbonization goal. In fact, Norris told me, “We work a lot with the environmentalists here—with the Sierra Club, and the Southern Environmental Law Center and so on—and there’s generally an openness to investing in nuclear research and technology.” He added, however, that “the attitude is ‘Let’s see how far it gets’ ” and, if “it comes down the cost curve and it’s available, then let’s take that into serious consideration. But we have no idea if it’s going to be available, and at what cost. It’s incredibly speculative.”

Also at issue, Norris says, is slow-walking the number of “interconnects”—upgrades to transmission lines to accommodate new power generation—that utility companies are offering to solar developers. In essence, utilities have to provide a path for the new electrons to flow–until they do, the solar panels are just pricy sheets of black glass. As Norris and Gillis put it in a Times Op-Ed earlier this month, “Huge backlogs of renewable energy projects have built up around the world as developers are refused permission to pump their power into the grid."

Battles over transmission upgrades will be a major sticking point in the years ahead in many places—and even from opposing sides. Sometimes, the issue involves building new corridors for electric power lines, and local environmentalists have often moved to block such projects. Jigar Shah, who is the director of the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office, pointed to a referendum in Maine last year, backed by local green groups, that killed a major new transmission corridor in that state. “These advocates are not really serious about giving people access to modern energy,” he told me. But, as Gillis points out, more often it’s the almost invisible local upgrades to transmission lines that become a bottleneck. “You want to develop a solar project somewhere, and you get control of the site—you sign a lease option with a farmer, say. And then you put your project in what’s called the ‘interconnect queue’ with the local utility. And then, depending on the state, you wait years to see whether you can build the thing or not. Nationwide, there are nearly enough solar and wind projects already in the interconnection queue to meet Biden’s goal”—of reducing emissions forty per cent by 2035—“but they’re not going to get built, because people can’t get answers. The power companies are still resisting upgrading the lines.”

And now the industry and its allies are going after projects before local authorities grant them permits, enlisting putative concern for the environment and ginning up NIMBY battles. Offshore wind, for instance, will have to be a large part of the energy mix, and in some ways it’s easier to site projects out at sea, especially now that new technology allows turbines to be built in deeper water, farther from the coasts and their vista-loving homeowners. But, as Emily Atkin and Michael Thomas recently reported in the newsletter Heated, groups such as the right-leaning Texas Public Policy Foundation have gone to court to block all offshore-wind development, not just in the Gulf of Mexico, on the ground that it could harm marine mammals—particularly the three hundred and fifty right whales that remain in the North Atlantic. It’s clearly possible to take protective measures to safeguard whales, such as by limiting underwater construction noise, and timing the work to avoid collisions between vessels and migrating whales; the Natural Resources Defense Council signed off on one such plan in June. And it’s just as clear that the T.P.P.F.—whose largest donors have included Koch Industries and the Koch family foundations—is not acting in good faith. Among other things, it has previously attacked environmental groups for trying to block oil drilling that endangered lizards in the Permian Basin. The group also supplied a series of officials for jobs in the Trump Administration who, in the words of one trade journal, “overwhelmingly reject climate science” and “promote more fossil fuel consumption.”

The same kind of manufactured opposition is shaping up on land. For many years, surveys found that solar energy was incredibly popular across political groups—Republicans, independents, and Democrats all favored far more public support for photovoltaics. But front groups sponsored by the fossil-fuel industry have begun sponsoring efforts to spread misinformation, crisscrossing the country with slide shows claiming that wind turbines routinely catch on fire, or lower property values, and that solar farms shed toxic chemicals into the water supply. “There’s always been some run-of-the-mill NIMBYism,” Norris, the North Carolina solar developer, said. “But there’s an increasingly organized opposition effort, and some of it is Astro-Turf stuff, no doubt.” He mentioned Robert Bryce, who was formerly a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, which has taken millions of dollars from various Koch entities in the past decade. Bryce is now the custodian of the Renewable Rejection Database, which tracks defeats for clean energy across the country. A recent entry, from Seneca County, Ohio, reads: “The County Commission passed a resolution on November 23 banning large wind and solar projects.” (Bryce described the database as a “journalistic document,” and said, “Astro-Turfing? I don’t even know what that is.” He added, “I’m not an opponent of solar—I’m a critic of it.”)

“Based on the way that project approvals work, it’s going to come down to a county-by-county basis,” Norris told me. “I thought solar energy was insulated from the culture wars until relatively recently, but it’s getting worrying.” Nationally, Billy Parish said, “We used to be able to say solar polled in the low nineties for popularity. But I think that’s probably begun to trail off a bit, become a little more polarized. It’s still very popular, but there’s definitely slippage.” And that slippage could mean a thousand different fights, each one delaying change past the point where the climate crisis slips irretrievably out of control. “Thanks to the I.R.A., money is not the chief obstacle,” Gillis said. “What Congress did was change the economics of the technologies we’re talking about. But what they did not do was remove all the other barriers slowing us down. Really, economics was the tailwind for renewables already. It just got better with the I.R.A. But the other friction remains.”

Which means that the task for those who want to see quick climate progress is to help smooth that friction. Some of that work will be familiar to activists, such as testifying at public-utility commissions or running for posts on zoning boards. “We need people who are willing to actually do the legwork,” Shah said. “To go to a city-council meeting and get in people’s faces. To say, ‘I have a turn to speak here, I understand the procedure.’ And there needs to be people behind that person who can write up the talking points and prepare the slide deck.” America consists, Shah notes, of almost twenty thousand cities and towns. “Five people in each, that’s a hundred thousand people. Which is doable. But there has to be an intentionality behind it.”

But other work will seem less familiar to people whose focus has been fighting pipelines or battling for congressional legislation, in part because it’s less confrontational. To understand the new imperative, Shah, who, before he went to the Department of Energy, worked for SunEdison—which is now defunct, but in the early twenty-tens was one of the biggest renewable developers in the nation—offered a lesson on the economics of transitioning to renewables. “If you want to put solar on your roof right now, it would cost about four dollars a watt,” he told me. “That’s not because of the equipment—the equipment is only $1.20 a watt. But it’s really expensive to acquire customers. The salesman has to go to your house, like, four times.” Environmentalists have been “so focussed on stopping things that they haven’t really focussed on building things,” Shah said. “They thought the private sector would focus on that. The private sector can do the first five per cent, the first eight per cent—it can find the early adopters. But the mid mass market, the late mass market—they’re really expensive to market to. That’s why solar is still four dollars a watt. If you want it at $1.85, then people have to work together. Cities, utilities—they have to aggregate demand together.”

You can see the difference in other countries. About three per cent of single-family homes in America have solar panels installed, compared with about thirty per cent in Australia, where “soft costs,” such as acquiring customers, are much lower. Anya Schoolman has been trying to close that gap. She runs the nonprofit group Solar United Neighbors, which started in 2007, when her son Walter and his best friend, Diego, then in middle school, watched Al Gore’s movie “An Inconvenient Truth” and decided that they wanted solar panels on their homes, in the Mount Pleasant neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Installing them was complicated and expensive, but Schoolman figured that bulk purchasing would make it easier and more affordable. The boys signed up forty-five neighbors in the first week, and the Mount Pleasant Solar Cooperative was born. “It took us two years, and that included a lot of politics,” Schoolman told me. With funding from foundations and donations, she organized SUN to take the work national. SUN has now helped organize three hundred and fifty group purchases across the country, and the process now generally takes about eight months to complete.

As Schoolman explained it, “First, we get invited into the community by local groups: environmental organizations or churches or maybe the League of Women Voters.” SUN then conducts about three months of sessions in the community, explaining “the technology, what it costs, the policies that can make it more or less affordable.” (Those policies vary widely across the country, Schoolman says; in D.C., thanks to more generous subsidies, the payback time for a solar project can be three years; in Indiana, it’s eleven.) Once people sign up, the group screens their roofs to insure that solar will work for them. “We’re about consumer protection,” she said. “If they’ve got a north-facing roof with a pine tree, we try to find an off-site community solar project for them to buy into instead.”

Once a couple of dozen households have committed, SUN sends out requests for bids from local contractors, and then members of the homeowners sort through them. Because Schoolman’s campaign finds the clients, saving contractors about three thousand dollars per customer in marketing costs, they can bid much lower for the job. “And now they can do all the work in one neighborhood at the same time. They can take the paperwork for ten rooftops to the permitting office at a time.” Before long, she said, the power is flowing, and “to close the cycle at the end, we have a big party, and we invite the media, we invite local elected officials to participate and take credit, and that gets on the wheel for the next cycle.”

The initiative for Rewiring America, which was founded two years ago, came from Saul Griffith, an Australian engineer who, at M.I.T., built the most thorough flow chart of American energy use ever assembled. (Lighting billboards requires 0.005 per cent of American power, if you were wondering, compared with flying military jets, which takes up 0.5 per cent.) He says that much environmental thinking—persuading people to buy smaller cars, or to turn down the thermostat—can’t scale quickly enough to meet the climate crisis. In his book “Electrify,” Griffith writes that a lot of Americans “won’t agree to anything if they believe it will make them uncomfortable or take away their stuff.” When Ari Matusiak, who was a special adviser to President Barack Obama before building a large nonprofit, signed on with the group, he brought in advisers including Leah Stokes and Donnel Baird.

With the passage of the I.R.A., Matusiak says, the organization is set to go to work. As he put it, “We’re launching a national consumer-awareness campaign, with the core thesis that the I.R.A. created an ‘electric bank account’ for every household in America. It’s just that people don’t know they have this bank account. It’s money that they can claim by accessing machines that are going to save them on their energy bill.” (The Congressional Budget Office estimated that the I.R.A. would cost about three hundred and seventy-nine billion dollars, but the funding is essentially uncapped for the next ten years—it will pay out for any qualifying project.)

The group is scheduled to launch a big program, called Rewiring Community, in the new year. It will partner with civic and local leaders to help people secure I.R.A. funding. Converting oil furnaces to heat pumps, and installing insulation and other efficiency measures covered under the I.R.A., Matusiak told me, would save homeowners almost two thousand dollars a year in energy bills, and the process would create thousands of new jobs in a midsize city. If a lot of people raise their hands and say, ‘I want a heat pump,’ it’s a clear signal to the contracting community: ‘We should train our people on that machine so we can get the business.’ But, to get that hand raised in the first place, you have to organize the organizers, everyone from the mayor on down.” Or, as Justin Gillis put it, “Gloomism has gotten us where we are so far. But now let’s take these carrots that Congress has created and dangle them in front of every freaking rabbit out there.”

It’s hard to handicap the outcome of this fight. You’d think that the Saudis and the oil companies would have the better of it. But electric cars are quieter, and easier and cheaper to maintain, than cars that run on gas. Heat pumps beat furnaces in cost and ease of operation. A magnetic induction range can cook food without triggering a child’s asthma. Lots of farmers are eager to build solar projects, especially now that we’re learning how to graze animals and grow specialty crops between the panels. Eventually, these advantages will win out. Eventually, though, is too far away. This is the next phase of the fight, and we have to win it fast, which means that the need for mass movements hasn’t gone away, just begun to shift in focus.

READ MORE  A man holding a sign with Medical debt is unjust written on it, gathers near the Capitol as he takes part in the March for Medicare for All in Washington D.C. (photo: Probal Rashid/Getty)

A man holding a sign with Medical debt is unjust written on it, gathers near the Capitol as he takes part in the March for Medicare for All in Washington D.C. (photo: Probal Rashid/Getty)

Cook County, Ill., and Toledo, Ohio, are turning to the American Rescue Plan to wipe out residents’ medical debt. Experts caution it is a short-term solution.

Officials in New Orleans and Toledo, Ohio, are finalizing contracts so that tens of thousands of residents can receive a similar letter in the coming year. In Pittsburgh on Dec. 19, the City Council approved a budget that would include $1 million for medical debt relief.

More local governments are likely to follow as county executives and city councils embrace a new strategy to address the high cost of health care. They are partnering with RIP Medical Debt, a nonprofit that aims to abolish medical debt by buying it from hospitals, health systems and collections agencies at a steep discount.

“What we need in this country is universal health care, clearly,” Toni Preckwinkle, the president of the Board of Commissioners in Cook County, said. “But we’re not there as a nation yet, and so those of us who are responsible for local units of government have to do everything we can to make health care available, accessible to people.”

About 18 percent of Americans have medical debt that has been turned over to a third party for collection, according to a report published in July 2021 in the medical journal JAMA. That figure does not account for medical debt that is carried on credit cards or all medical bills owed to providers. Research shows that people with medical debt are less likely to seek needed care and that medical debt can damage people’s credit and make it more difficult for them to secure employment.

Cook County plans to spend $12 million on medical debt relief and expects to erase debt for the first batch of beneficiaries by early January. In Lucas County, Ohio, and its largest city, Toledo, up to $240 million in medical debt could be paid off at a cost of $1.6 million. New Orleans is looking to spend $1.3 million to clear $130 million in medical debt. The $1 million in Pittsburgh’s budget could wipe out $115 million in debt, officials said.

These initiatives are all being funded by President Biden’s trillion-dollar American Rescue Plan, which infused local governments with cash to spend on infrastructure, public services and economic relief programs. Health policy experts say that while medical debt relief provides an immediate benefit to people, it does not address the root causes of medical debt, which is almost nonexistent outside the United States.

To be eligible for debt relief through RIP Medical Debt, people must have a household income up to 400 percent of the federal poverty level, or about $111,000 for a family of four, or have medical debts that exceed 5 percent of their annual income. People cannot apply to be considered for debt relief, and they do not pay taxes on the purchase of their debt. RIP Medical Debt analyzes debt portfolios to determine who qualifies.

Wendy Pestrue, the chief executive of the United Way of Greater Toledo, said debt relief could remove a source of economic stress for the 43 percent of families who either were living in poverty or were unable to afford housing, child care, food, transportation or health care in Toledo, which has a population of nearly 269,000.

“It puts some of this economic strength back in the hands of those who are having debt exonerated and really helps them plan for their stability,” she said.

Michele Grim, who joined Toledo’s City Council in January 2022, pushed for some of the city’s $180 million in American Rescue Plan funds to be used for medical debt relief after she read about the Cook County initiative.

“Here’s something so simple that local governments can do, maybe even state governments can do, to really help ease that burden on people, because we really need an overhaul in our system, and that’s going to take years,” said Ms. Grim, who is leaving the council at the end of the year because she was elected in November to be a Democratic state representative.

Toledo’s City Council voted 7-5 on Nov. 9 to provide $800,000 to pay off the debts. Its contribution was matched by Lucas County, resulting in $1.6 million for medical debt relief. The city, the county and RIP Medical Debt are now working out a contract.

One council member who opposed the plan was George Sarantou, who said that he voted against it because his top funding priority was public safety, including upgrading city fire stations and police vehicles. While Mr. Sarantou said he was not opposed to medical debt relief, he was concerned about state funding for cities and villages, which is expected to be 1.66 percent of Ohio’s 2022-23 budget. “Ohio has the money,” he said. “Toledo does not.”

Medical debt relief appears to be popular. A poll by Tulchin Research found that 71 percent of respondents supported it. Fifty percent supported relieving student loan debt, 65 percent supported “Medicare for all” and 68 percent supported expanding Medicaid. The national poll of 1,500 people was conducted online from Nov. 14 to 20, after the Toledo vote, and had a margin of sampling error of plus or minus three percentage points. (Ms. Grim’s husband works for the polling company.)

This debt relief comes as states change how medical debt is treated.

In November, Gov. Kathy Hochul of New York signed legislation that blocked health care providers from using property liens or garnishing wages to collect medical debt. The day before the Toledo City Council vote, 72 percent of Arizona voters chose to lower interest rates for medical debt and to increase protections for people who owe debt, though a judge has since halted part of the measure.

Wesley Yin, an associate professor of economics at the University of California, Los Angeles, said medical debt relief could be a “game changer” for some people, but governments should also be addressing the causes of medical debt, including high costs and limited access to good health insurance.

In partnership with RIP Medical Debt, Professor Yin is studying how the group’s work affects people’s livelihoods. “I believe there are some positive effects economically, but it might be more muted compared to the face value of the debt that is being forgiven,” he said.

Daniel Skinner, a health policy professor at Ohio University in Athens, said that debt relief was “low-hanging fruit,” considering that the mean amount of medical debt people carry is in the hundreds, not tens of thousands, of dollars.

“We need to get the cost of medicine under control, ultimately,” Professor Skinner said. “I’m all for what Toledo is doing, I’m all for what Cook County and now New Orleans are doing, but, ultimately, we can’t come back every couple of years and do this. It’s not good policy, it’s not efficient.”

Supporters of debt relief measures agree that there is more to be done.

RIP Medical Debt’s chief executive, Allison Sesso, said that a key part of the group’s work was to further discussions about changing the health care system.

In the past two years, RIP Medical Debt has placed more of an emphasis on buying debt directly from hospitals and health systems, before it reaches collectors. Ms. Sesso said that this gave the group a direct channel to talk with hospitals about how their own health repayment plans for low-income patients work. Some of the people whose debt RIP Medical Debt buys should have qualified for these programs in the first place, but they were not enrolled, she said.

“I do this job every day, and I appreciate that what we’re doing is really important and helpful for the individuals that we are helping and it’s resolving this problem for them,” Ms. Sesso said. “At the same time, I can’t help but wonder and question why my existence as an institution is needed in the first place.”

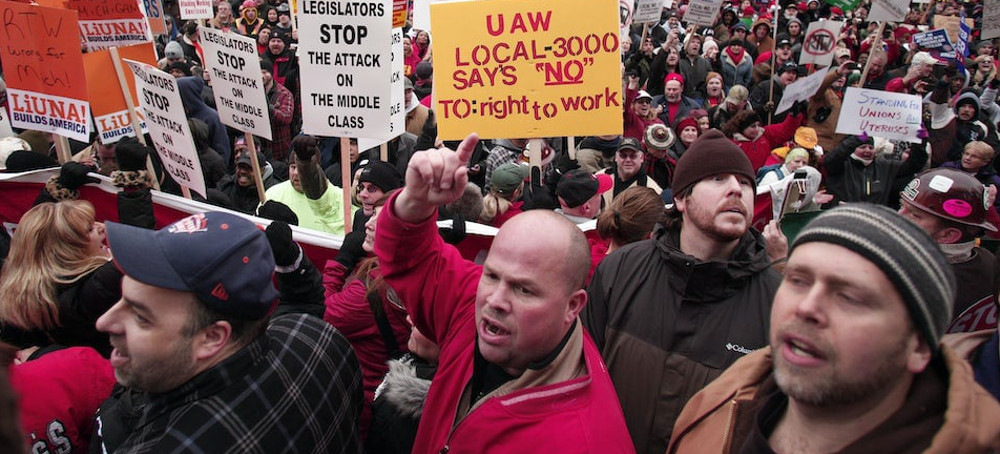

READ MORE  Union members protesting a vote on right-to-work legislation in Lansing, Michigan, in 2012. (photo: Bill Pugliano/Getty)

Union members protesting a vote on right-to-work legislation in Lansing, Michigan, in 2012. (photo: Bill Pugliano/Getty)

The party now has complete control in Lansing. Time to repeal the state’s anti-union right-to-work law.

Such laws are deliberately anti-union and divisive. They let workers opt out of paying any dues or fees to their union while still enjoying the benefits their union provides them: winning better pay and benefits and fighting to protect them if they’re fired. Pushed by corporations and billionaire donors, Republican lawmakers have enacted these laws in state after state because they weaken labor unions by sapping their treasuries and undercutting their power—both in the workplace and in politics.

In an era when Republicans have repeatedly prevented Congress from enacting pro-union legislation like the Protecting the Right Organize Act, the Michigan legislature—as soon as Democrats take control in January—will be in position to take a momentous step to strengthen unions. Repealing right-to-work in Michigan would be a big symbolic and substantive shot in the arm for labor across the U.S. It would also be a powerful way for Governor Gretchen Whitmer to prove her labor bona fides if she runs for president one day.

Republicans repeatedly claim that right-to-work laws are pro-worker because they let a company’s employees opt out of paying any union dues or fees. But supporters of these anti-union laws ignore the other side of the coin: These laws harm the many workers who are strong union supporters by weakening their unions and by forcing those workers to pick up the financial slack from their free-riding co-workers. In this way, these laws divide workers against each other—and undermine worker solidarity.

Sowing division among workers was what motivated the biggest, early champion of right-to-work laws: Vance Muse, an antisemite and white supremacist from Texas who saw these laws as a way to prevent African American and white workers in the South from joining together to demand higher pay and better treatment. Muse pushed the right-to-work idea hard in the 1930s and 1940s, viewing it as a way to enable racist white workers to opt out of being in unions alongside Black workers.

Not only do right-to-work laws undermine unions, they also hurt workers’ wages. The Economic Policy Institute found that workers in right-to-work states earn 3.1 percent less than comparable workers in states without such laws, after adjusting for differences in the cost of living. That means a worker’s pay is on average around $1,600 less per year.

One study found that the portion of workers in right-to-work states who opt out of paying union dues or fees ranged from 9 percent in Georgia to as high as 27 percent in Louisiana, 31 percent in Florida, and 39 percent in South Dakota. This translates into a sharp decline in dues payments, and that weakens union treasuries and hampers unions’ ability to do organizing and other work.

Another study found that in the five years after states enacted right-to-work, the number of organizing drives dropped by 28 percent, and in the following five years by an additional 12 percent. Unionization victories fell by 46 percent in the first five years and 30 percent the next five.

There’s one other thing that Republican supporters of these anti-dues laws will never admit in public: They like these laws because they reduce organized labor’s voice and strength in politics, and that hurts the Democratic Party. In a recent study, three scholars found that “when right-to-work laws are in place, Democrats up and down the ballot do worse.” They concluded that in “right-to-work counties,” Democrats perform about 3.5 percentage points worse in presidential elections, with “similar effects in Senate, House, and Gubernatorial races, as well as on state legislative control.” That study also found a 2 percent drop in voter turnout in “right-to-work counties.” Let’s not forget that in 2016, Hillary Clinton lost Wisconsin and Michigan by less than 1 percent of the vote.

There’s no denying right-to-work’s negative effects on unions. In the years since Michigan enacted right-to-work in 2012, union membership in that state has fallen 15 percent, far greater than the 3.5 percent nationwide drop in membership over the same period.

Republicans know that right-to-work laws weaken unions, and that’s why they love them. In early 2017, right after Republicans won control of both legislative chambers in Kentucky for the first time since 1920, GOP leaders made right-to-work the very first law the new legislature passed. Similarly, in 2016, as soon as Republicans in West Virginia won control of both legislature houses for the first time since the 1930s, that state enacted right-to-work. The Koch brothers’ political arm, Americans for Prosperity, backed by a network of right-wing billionaires, pushed behind the scenes for Kentucky and West Virginia to enact these laws. They did so not just to undermine organized labor, but to make the statement that those states were now officially proclaiming themselves anti-union—and, yes, that helps lure some low-road, union-hating corporations to those states.

Conservative operatives know that once a state passes right-to-work and other anti-union measures, it’s easier for Republicans to enact other conservative legislation, like restricting voting rights, cutting Medicaid, and giving tax breaks to corporations and the rich. In his book State Capture: How Conservative Activists, Big Business, and Wealthy Donors Reshaped the American States—and the Nation, Alexander Hertel-Fernandez wrote, “State policy moves sharply to the right after the passage of anti-union right-to-work laws—with real consequences for ordinary Americans on issues like minimum wage and labor market standards.”

When Republican-dominated legislatures in Indiana, Missouri, Wisconsin, and Michigan passed right-to-work laws between 2012 and 2017, they too wanted to make a strong anti-union statement—one that stirred considerable anger in the Midwest industrial belt, where labor unions have played a huge, historic role since the 1930s and where union contracts with General Motors, Ford, Chrysler, and U.S. Steel played a pivotal role in building the world’s largest and richest middle class. If Michigan repeals right-to-work, it will make an important statement to counter red state, anti-union legislatures.

With 71 percent of all Americans, including 56 percent of Republicans, voicing approval of unions in an August Gallup poll, it is clear that red state legislatures—pushed by corporations and wealthy donors—are often far more anti-union than the public at large. In 2018, Missourians voted 67 to 33 percent to repeal a year-old right-to-work law enacted by the state legislature.

Over the past year, the U.S. has seen exciting unionization efforts at Starbucks, Amazon, Trader Joe’s, Chipotle, and Apple, but these efforts have faced a fierce counterattack from corporate America. Starbucks and other companies are trying their hardest to slow, even strangle, these organizing drives. Unions need all the help they can get to sustain their recent momentum and grow. Repealing right-to-work in Michigan—a cradle of American unionism—could be just the jolt the labor movement needs.

READ MORE  The Daily Beast tracked down a teen girl who was sold into sex slavery via a Facebook account—even though the Silicon Valley giant was warned about the ad showing her picture. (photo: Philip Obaji Jr.)

The Daily Beast tracked down a teen girl who was sold into sex slavery via a Facebook account—even though the Silicon Valley giant was warned about the ad showing her picture. (photo: Philip Obaji Jr.)

The Daily Beast tracked down a teen girl who was sold into sex slavery via a Facebook account—even though the Silicon Valley giant was warned about the ad showing her picture.

How could she? After all, her aunt was expecting them.

Their leather shoes were caked in mud from the narrow path that leads up behind the house. Agnes recalls the men, who both looked as though they were in their thirties, asked her if she was ready to go.

“Who are you people?” she replied. “And what are you talking about?”

Aunt Helen—who had looked after Agnes since the girl’s mother died in a car crash on Valentine’s Day 2015—smiled and explained that she had good news.

She had found Agnes a job that would mean she could finally return to school. Agnes had stopped going to class in the eighth grade when intense fighting between Cameroon’s government forces and local separatists broke out. Since then, they had been sharing a small hut in a refugee settlement just over the border in Nigeria. She dreamed of returning to school in Cameroon.

It took Agnes ten minutes to pack her belongings into a zip-up woven nylon bag. She climbed into a waiting Volkswagen Passat.

That was two years ago.

Agnes was not taken back to school. She was being smuggled into a hellish existence of rape and slavery.

But this story did not really begin in a cramped and under-resourced United Nations-funded refugee encampment in Sub-Saharan Africa. It began on Facebook.

Unbeknownst to her, a photograph of Agnes had been posted to the pages of the U.S. social media giant in December 2019 by an account in the name of Stan Wantama. He asked for people wishing to take Agnes and two other girls as maids to send him a private message.

“She’s young and 16. Want her as a house maid? Inbox me,” wrote the man calling himself Wantama, who included an email provided by the Russian company Yandex.

It is unclear if Stan Wantama is his real identity; the profile image was a drawing of a young man of African origin in black and white although people in Adagom who saw him in person told The Daily Beast he did not closely resemble the man in the picture. On the Facebook page, he claimed that he lived in Abuja, Nigeria’s capital city.

I came across Wantama’s Facebook posts on the afternoon of Dec. 29, 2019—at which point she was still for sale—and at 5 p.m. Nigerian time, I emailed the company's spokeswoman Sarah Pollack and policy director Andrea Saul to alert them to the posts that I suspected may be linked to people trafficking.

For about 29 hours, Facebook took no action.

We did not know it at the time, but according to internal Facebook documents shared by the whistleblower Frances Haugen last year, the company had just introduced new measures because its platform was rife with advertisements that may have enabled human trafficking. In the weeks before Agnes was allegedly put up for sale, leaked internal documents reveal that Facebook found and disabled nearly 130,000 pieces of content and over 1,000 accounts as part of a search for content that sought to trade and sell domestic servants in the Middle East and North Africa. The problem was so big that earlier that year they had already expanded their “Human Exploitation Policy” which was supposed to ban the recruitment, facilitation, or exploitation of domestic servitude on their platforms with improved technology to detect the messages.

None of these brand new policies did anything to prevent the post about Agnes.

It wasn’t as if the Wantama account was being subtle. Not only did the first post clearly introduce him as someone who could “help connect people to young house maids”—the girls he posted about were clearly young and vulnerable. He also started to negotiate with people right there in the open comment threads. “Check your inbox” he told one Facebook user who commented “I’m interested.”

The alleged trafficker was telling Facebook’s algorithms so much about his business and his intentions and yet the company—which changed its corporate name to Meta after last year’s whistleblower emerged—still couldn’t stop him in time.

Facebook finally responded to my email at 10:02 p.m.. Kezia Anim-Addo, head of communications for Facebook in Africa, said the company was “currently looking into this at the moment.”

Shortly after, Wantama’s account was suspended.

But it was too late. Someone had allegedly bought Agnes.

It took me 18 months to track her down.

The first hint that Agnes could have come from the refugee settlement where I would eventually find her family came via another of the girls being advertised on Facebook. With that tip-off, I set out for Adagom in December 2019 armed with downloaded photos of the girls.

The community is located in Ogoja in Cross River State, which is regarded as one of the most peaceful parts of a region where clashes are common. Thousands of people fleeing the conflict in Cameroon’s northwest and southwest Anglophone regions have flooded here.

The photos led to a carpenter, known as Clemwood, who said he was the father of one of the girls, Glory*, 13. He said Wantama had befriended him in a local carpentry workshop and offered to connect his daughters to families who would help them return to school.

“All he said was that he knew families who could assist my daughters complete their secondary education provided they work for them as house maids,” said Clemwood, who fled with his family from the southwestern Cameroonian town of Akwaya in early 2018 after soldiers stormed their compound and began to burn houses. “He never told me he was going to find a home for any of my children through Facebook and that he was going to get money from anyone willing to take any of my children.”

Having spoken to Clemwood, who maintained that his very young daughter was advertised on Facebook as a maid without the consent of the family, I went back to Facebook. They confirmed that Wantama’s post was “removed” and his account “permanently disabled” as a result of “various violations.”

Even though it had now been disabled, I posted another warning about the Wantama account on Facebook.

Then, on Jan. 11, 2020, I received an email from an account in the same name threatening to teach me a lesson. “You think you’re smart to report me for human trafficking,” wrote Wantama, claiming he had hacked into my phone and obtained personal information. “Let me warn you, we’ll deal with you and you’ll be silenced.”

He did not reply to follow-up emails about the whereabouts of Glory, Agnes, or any of the others.

Clemwood continued to call and call the numbers he had for Wantama and Glory with no response for a year. The trail had gone cold.

That was until July 2020, when Helen, Agnes’s aunt, happened to walk into Clemwood’s workshop to buy a kitchen stool. She overheard him talking to an elderly man about what had happened to his daughter. Helen recognized the story and soon came to believe that her niece had been taken by the same man. Again, no-one had heard from Agnes since.

Next time I was in Adagom, Clemwood took me to Helen, who he believed would be able to describe Wantama better than he could. “She has had a longer conversation with Wantama than me,” he said.

At Helen’s small two-room home, built with mud and covered with corrugated iron sheets, a photograph of Agnes lay on the head of a six-spring mattress. Helen, a devoted Christian, looks at the photograph closely every morning and says a prayer for her niece, believing that she’ll return home one day. But she is full of regret for letting her leave with someone she hardly knew.

“He [Wantama] said he had noticed my niece from afar and was convinced she was a brilliant girl and so he wanted to ensure that she worked for somebody who would make sure she completes her secondary education,” Helen said. “It now feels as if he deceived me and absconded with her.”

Helen has been Agnes’s guardian since she was 12. Her sister—Agnes’ mother—died in a car crash on Feb. 14, 2015. Agnes never met her father. The family says her mother was raped and impregnated by a man who fled. Agnes’ mother raised her daughter alone—often working as a domestic servant for families in Yaounde to be able to raise money to care for her only child.

“After her mother died, I went to Yaounde and brought her back to Akwaya to stay with me,” said Helen. “But the Anglophone war began a few years later and so we fled to Nigeria.”

The conflict erupted after Cameroon’s French-speaking government cracked down on English-speakers, who make up 20 percent of the population and were trying to safeguard their own enclave in the country’s northwest. Since a referendum in 1961, when Anglophone Cameroonians—then under British rule—voted to rejoin Francophone Cameroon, relations between the two groups have been difficult, especially as the central government pared back regional autonomy.

Security forces began a brutal crackdown on protesters in 2017, killing people and burning communities. A number of armed Anglophone groups began to retaliate, worsening the situation and contributing to the displacement of hundreds of thousands of English-speakers. More than 71,000 Cameroonians are now registered in Nigeria as refugees.

A report by the UNHCR (PDF) released the same year Wantama is alleged to have exploited the refugees, found that three in four Cameroonian refugee households do not have adequate access to food. Up to 82 percent of Cameroonian refugees in Nigeria are adopting what the UN refers to as “negative coping strategies” which include labor exploitation and survival sex. Many, especially teenagers, end up in the hands of persons with a history of exploiting vulnerable people.

A call came through to Helen totally out of the blue after almost a year and half of silence. It was Agnes, and she said she had just escaped from the home of the man Wantama handed her over to.

She said she was safe, and staying with an old school friend in Eyumojok in southwest Cameroon which was about 10 miles from the border town of Ekok, close to Nigeria. The story of what had happened to her there during that long period away from home was shocking.

Helen let me know that she had received word, and I set off to meet Agnes who wanted to tell the full story.

Ekok is a notorious town where all kinds of contraband pass through—smuggled oil, foreign rice, arms, and the trafficking of kids. The United States Embassy in Cameroon noted in a report this year that Nigerian traffickers increasingly bring children from the country “to major Cameroonian cities for forced labor.”

There is a lawless atmosphere in this region, partly because the authorities are more concerned about rebel groups. Following the Anglophone crisis, Cameroonian security agencies along the Nigerian border have been on the lookout for separatists and their sympathizers. You could be arrested for wearing an unshaved beard or dressing in tattered clothes, as officials will assume you’ve spent days in the bush fighting government forces. The smuggling, however, continues virtually unchecked.

When I arrived, Agnes emerged from the front door of a small two-room apartment on the outskirts of Eyumojok wearing a long gown that nearly covered her feet. She looked very different to the kid Wantama had advertised on Facebook. Her hair had grown out and was woven back, her face more mature than the one that appeared on Wantama’s Facebook feed. She greeted me with a huge smile.

The softly-spoken teenager said she was taken to Ekok on New Year's Day 2020 along with two other girls about her age after Wantama picked them up from the Nigerian border town of Ikom. On arrival in Cameroon, she said the girls were taken to a compound filled with single-room houses built by a local importer to shelter the drivers and store goods brought in from Nigeria. She said the three girls spent the night sleeping on the floor of an empty room with no bathroom and no mattress.

At this point, Agnes still believed they were on their way to meet their new employers who would allow the girls to return to school.

“Throughout the journey, and even when we got to Ekok, he spoke nicely to us and even apologized for keeping us in a very poor room,” Agnes said of Wantama, whom she believes to be in his forties. “But he often made comments about our bodies, telling us how cute our breasts appeared or how big our buttocks were.”

Agnes says Wantama disappeared and then returned to the compound the following morning with a “very huge man” known as Jimmy who drove a white Toyota Hilux pickup truck.

Agnes says Wantama came straight into the room and spoke directly into her ear, telling her that her new boss had arrived and she needed to get into the waiting vehicle immediately.

It was at this point that Agnes became alarmed.

“While I was heading to the vehicle, he held my wrist and whispered, ‘Jimmy likes you, so make sure you give him everything he wants or else he would be very angry,’” said Agnes, who says Jimmy was middle-aged. “I immediately began to think they wanted me for something else, not the housemaid job they initially claimed.”

As they drove off, Agnes said Jimmy told her she looked prettier in real life than in the photograph.

She had no idea what he was talking about.

“He said he saw the post on Facebook on his birthday on December 30, 2019 and quickly indicated interest,” said Agnes. Dec. 30 was the day after I had alerted Facebook to the post advertizing the teenager.

When she saw the photo she realized it had been taken without her knowledge when she was waiting with friends at the refugee settlement to receive sanitary pads from a group of humanitarian workers. “I was shocked because I never told anyone I wanted to become a maid, not to talk of giving anyone my photograph,” she said.

When Agnes arrived at Jimmy’s home in Ekok, “There was no work to do," she said. Jimmy's modest three-bed apartment already had a housemaid, who did the cooking and cleaning of the property, which also housed two of Jimmy's male cousins. On her first night in the house, Agnes says Jimmy called her into his room and began to touch her inappropriately. She says she told him she was uninterested and demanded that he stop but claims he said he was going to throw her out of the house if she didn't comply. She finally succumbed.

“He forced me to have sex for the first time in my life,” Agnes said. “I was scared he’d harm me if I didn’t do what he asked me to do.”

The next morning, Agnes said she woke up feeling terrible about the previous night. She told Jimmy, who is a Nigerian national, that she had become traumatized and wanted to return home. In response, he asked her to pack her belongings and move them into the vehicle so they could leave Ekok. But rather than return to Nigeria, Jimmy drove her straight to Mamfe, where she says he kept her in a one-room servants’ quarters, behind a three-bedroom apartment where he stayed. He also arranged for her to work as a waitress in a bar he owns in the city. She said Jimmy had told security men at the bar and at her makeshift home not to allow her to step out of either property.

At Jimmy’s bar, Agnes said she worked from 10 a.m. until past midnight everyday except Sundays. She says she wasn’t paid for her work, neither was she enrolled into secondary school as she was promised before leaving Nigeria. Instead, Jimmy kept introducing her to his friends who visited the bar and, on many occasions, insisted she follow one of them to where they stayed—often in hotels and guest houses—after the bar closes in the early hours of the morning.

“He would insist that I accompany one of his friends to his home because he was going to spend the night elsewhere and so he wouldn’t be able to drop me at home,” said Agnes. “I knew I couldn’t sleep in the bar because of the high crime rate in the area, so I had to do as Jimmy said.”

But Agnes says many of those nights were “terrible.” She explained that the men would often force her into having sex with them. On other occasions, she was cajoled into the act by friends of Jimmy who promised they were going to assist her get a decent job and support her return to secondary school. In the end, Agnes received no assistance from anyone.

“You hardly get to hear from these men again after they leave,” Agnes said. “They take your phone number and promise they’ll call you when they get to Nigeria but they never do.”

Mamfe has been a people trafficking hotspot for almost 100 years. The British linked Cameroon and Nigeria by road in the 1930s by creating the Ikom-Mamfe road. Soon after, the road became the main path used by traffickers to transport women and children to the Gold Coast (now part of Ghana), where a booming economy attracted people from across Central Africa. The trafficking of girls through Mamfe became so notorious that it was being publicly denounced by 1943.

After being exploited in Mamfe, Agnes began to look for ways to escape. She had been saving the little money she got from customers who left their change as a tip, but didn’t find the chance to run away for five months.

The opportunity eventually came one Sunday morning in early June 2021 when she accompanied Jimmy to Ekok to pick up drinks for the bar. When he went into a busy motorpark to pick up the beverages, the teenager jumped out of the vehicle and ran as far as she could. She spent the rest of the day hiding before returning to the transport hub that evening and heading to Eyumojok, where she knew her best friend from secondary school lives with her aunt.

“Leaving Jimmy feels like getting out of prison,” Agnes told The Daily Beast last summer. “I’m very happy I have my freedom again and can’t wait to return to school.”

With her dream so close, Agnes soon ran into another hurdle. She discovered that she had been impregnated by one of her attackers, which further delayed her enrollment in school particularly after the young child developed persistent respiratory problems.

“I don’t want to live my life worrying about who could be my child’s father,” Agnes said in October. “I just want to live freely.”

Agnes believes Facebook played a huge role in her ordeal.

If Facebook had acted more quickly in taking down Wantama’s posts and disabling his account, it is possible that Agnes’s nightmare could have been avoided. When asked if the company had learned lessons from Wantama’s posts or adapted new policies following his action, the company said that it has not found any other Facebook account in either Nigeria or Cameroon “acting in a similar way.”

"Any form of human trafficking—whether posts, pages, ads or groups—are not allowed on Meta’s platforms, and will continue to be removed when reported to us,” said Jeanne Moran, a policy communications manager at Meta, Facebook’s parent company.

Agnes has never had a Facebook account and is not about to sign up. The thought of the social media platform will always remind her of what is the “saddest moment” of her life.

“Many people talk about how Facebook helped them promote their businesses and connected them to new friends, but that isn't the same story for me,” said Agnes. “When I think about Facebook, I remember where I was put up for sale.”

Agnes eventually found freedom, but Clemwood is still searching for his missing daughter, Glory, who would soon be celebrating her 16th birthday, the last few years of her childhood snatched away.

READ MORE  Maxwell Frost wants to put pressure on Republicans ‘who sweep the deaths of children under the rug’. (photo: Tom Williams/Getty)

Maxwell Frost wants to put pressure on Republicans ‘who sweep the deaths of children under the rug’. (photo: Tom Williams/Getty)

Maxwell Frost places curbing gun violence at the top of his political agenda, along with addressing the housing crisis

Frost expected there would be a fair amount of negative reaction after he became the first member of Gen Z to be voted into Congress in last month’s midterm elections.

But a heavy campaign focus on gun safety measures has made the 25-year-old Democrat from Orlando, Florida, a marked man. The issue couldn’t be more important to Frost, who calls Gen Z “the mass shooting generation”.

“It feels like I’ve been through more mass shooting drills than fire drills,” he says.

Frost not only came of age with many of the survivors of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas 2018 high school shooting, but barnstormed the country with them to advocate for tougher gun controls.

Shortly after Frost beat Republican rival Calvin Wimbish by a considerable margin in Florida’s 10th congressional district in November (which includes Frost’s Orlando home town and many of its surrounding theme parks), the gun-saturated country was rocked by seven more mass shootings in as many days.

It’s why passing more substantive measures to curb gun violence is at the top of his list of priorities for his first six months in office.

“I think we have an opportunity, even in a Republican Congress, to pass legislation that can help get money for community violence intervention programs that help end gun violence before it even happens,” he said.

He further insists that any prospective legislation needs to have a mental health component.

“Folks with serious mental health issues are often scapegoated as the reason why there’s gun violence,” Frost says. “But as someone who’s been doing the work, when you look into the numbers, having a serious mental health issue doesn’t make you more likely to shoot someone. It actually makes you more likely to be shot.”

Frost intends to keep the pressure on both Republicans “who sweep the deaths of children under the rug” and on members of his own party who have been otherwise disinclined to take bold action. “I’d venture to say that gun control is the slowest-moving issue in the federal government that has the most media coverage when something happens,” he says. “I have to be the consistent voice.”

You’d be hard-pressed to take in Frost’s sudden emergence on the national scene without harking back to the rise of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AKA AOC) who, at age 29 in 2019, became the youngest woman ever elected to Congress. Like Frost, she boasts Latino heritage, has a working-class background, counts Bernie Sanders as a close mentor and espouses politics that lean left of most fellow Democrats. All of that has made AOC an easy enemy of the right as she joined up with Ilhan Omar, Ayanna Pressley and other young liberals since to alloy the informal progressive caucus known as the Squad.

Frost would be a natural fit on that team. But he’s not in much hurry to join forces with them or any other groups right now. “You’re gonna have different allies in different battles and I think it’s really important,” says Frost, who still has plenty of love and admiration for the Squad. “I mean, Cori Bush slept on the Capitol steps and as a result of that, people weren’t evicted from their homes. That is a case study in how working-class people and organizers in Congress are good for our country.”

Housing will be another focus of Frost’s first 100 days – one that his own situation, a limbo complicated by bad credit and a $174,000 (£143,687) federal salary that he won’t begin drawing until February, has thrust into the spotlight.

“We have the worst affordable housing crisis in the country, per capita in central Florida as of a few months ago,” he says.

“We need to do work to increase the power of renters in the marketplace and ensure that renting is actually accessible for people. It’s really hard right now and I know this personally not just from being houseless in DC, but also from being houseless for a month in central Florida and not having enough capital to move into a place.”

He also thinks he can make a credible pitch for more funding for the arts, the cherished avocation that initially got him and his high school band to Washington DC to play in Barack Obama’s 2013 inauguration parade.

“The arts are a huge part of my life,” he says. “I went to [an] arts middle school and high school. I work on music festivals and have my own here in Orlando, and I really believe in the power of the arts – and it’s not equitable for everybody right now.”

All the while he intends to use his time in Congress to inspire young people to get involved in the political process, starting with making the federal government more approachable. “I want to do a kids’ day on the Hill,” he says. “I want to do concerts on the Hill – with young artists, so we can get young people super excited. I’ve been doing these blogs about what’s going on on the Hill. So just little things like that. I’m just really focused on stretching what it means to be a member of Congress.”

READ MORE  More than 400 statues, paintings and other artworks in the U.S. Capitol honor enslavers and Confederates. (photo: Katherine Frey/The Washington Post)

More than 400 statues, paintings and other artworks in the U.S. Capitol honor enslavers and Confederates. (photo: Katherine Frey/The Washington Post)

The Post examined more than 400 statues, paintings and other artworks in the U.S. Capitol. This is what we found.

As part of a year-long investigation into Congress’s relationship with slavery, The Washington Post analyzed more than 400 artworks in the U.S. Capitol building, from the Crypt to the ceiling of the Capitol Rotunda, and found that one-third honor enslavers or Confederates. Another six honor possible enslavers — people whose slaveholding status is in dispute.

Congress has made some efforts to address the legacy of slavery since the 2020 protests that followed the death of George Floyd. The 117th Congress — the most diverse in history — established Juneteenth as a national holiday. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) had portraits of speakers who participated in the Confederacy removed. Florida replaced a Confederate statue representing the state with one honoring Mary McLeod Bethune, the first African American chosen for the National Statuary Hall Collection.

And on Tuesday, President Biden signed a bill to remove and replace a bust of Supreme Court justice and enslaver Roger B. Taney — infamous for the Dred Scott decision denying Black people citizenship — with one of Thurgood Marshall, the first African American justice.

But a House effort to remove statues honoring Confederates stalled in the Senate. One of those Confederate statues stands in front of the office of the House majority whip, currently occupied by Rep. James E. Clyburn (D-S.C.), the first Black person to serve multiple terms in that role.

Clyburn and several other Black members of Congress did not respond to requests for comment about the art in the Capitol. Del. Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-D.C.), a civil rights activist who has worked in the Capitol for 32 years, called the Confederate statues “very anachronistic.”

Just as governments and institutions across the country struggle with the complex and contradictory legacies of celebrated historical figures with troubling racial records, so too does any effort to catalogue the role of the Capitol artworks’ subjects in the institution of slavery. This analysis, for example, includes at least four enslavers – Benjamin Franklin, John Dickinson, Rufus King and Bartolomé de las Casas – who voluntarily freed the people they enslaved and publicly disavowed slavery while they were living. Other people, such as Daniel Webster and Samuel Morse, were vocal defenders of slavery but did not themselves enslave people; artworks honoring them are not counted in The Post’s tally.

The Capitol Rotunda, at the heart of the building, is particularly replete with enslavers. More than two dozen artworks there depict enslavers, from statues on its marble floors and paintings on the walls to friezes and murals overhead. It also includes the only known depiction of a female enslaver in the building: Martha Washington, who inherited 84 enslaved people from her first husband.

Some of the artworks reflect the reality that most of the nation’s prominent founders were also enslavers; there are 17 depictions of George Washington, nine of Thomas Jefferson and five of James Madison. But there are also 15 depictions of Christopher Columbus, who never set foot in North America and enslaved Indigenous people in the Caribbean. The majority of the artworks honor lesser-known figures who were deeply involved in the African slave trade, the enslavement of Indigenous people, forced plantation labor and the war fought to preserve slavery. Two statues portray physicians who experimented on enslaved people.

None of the works are accompanied by any acknowledgment that their subjects enslaved people.

A total of 141 enslavers, 13 Confederates and six possible enslavers are depicted in 139 artworks in the Capitol. There is some overlap; most of the Confederates were also enslavers.

Since 2009, three sculptures and four paintings depicting Confederates have been removed from the Capitol; another, depicting the Confederate attorney Uriah Milton Rose, is slated for removal. The remaining Confederates honored are Alexander Stephens, Crawford W. Long, Edward Douglass White, James Zachariah George, Jefferson Davis, John Bell, John C. Breckinridge, John E. Kenna, John Tyler, Joseph Wheeler, Wade Hampton and Zebulon Vance.

Thirty-two of the depictions of enslavers and Confederates, plus another two depictions of possible enslavers, are part of the National Statuary Hall Collection, created in 1864. Each state can contribute two statues depicting notable deceased residents for display in the Capitol as part of the collection. A 2000 law allowed states to remove and replace statues with the approval of the state’s legislature and governor. Neither Congress nor the office of the Architect of the Capitol, which maintains the statues, has the power to remove them. (The collection is distinct from the Capitol’s National Statuary Hall room, though most — but not all — of the statues in the room are also part of the National Statuary Hall Collection.)

Twenty-three states have at least one statue depicting an enslaver or Confederate. Another two have statues depicting possible enslavers. For nine states, both of their statues honor men in these categories.

All 11 states that joined the Confederacy have at least one statue depicting an enslaver or Confederate. But the homages to enslavers are by no means restricted to these states: Except for New Hampshire, all of the original 13 states have statues depicting enslavers or possible enslavers.

Massachusetts, for example, is represented by John Winthrop, who is best known for proclaiming a “shining city on a hill” but who also enslaved at least three Pequot people and, as colonial governor, helped legalize the enslavement of Africans.

Both of New York’s statues honor enslavers. One is Declaration of Independence co-writer Robert R. Livingston, who came from a prominent slave-trading family and personally enslaved 15 people in 1790. He also owned brothels that housed Black women who may have been enslaved. The other is former vice president George Clinton, who served under Jefferson and Madison and enslaved at least eight people in his lifetime.

Even some states where slavery was never legal are represented in the Capitol by enslavers or possible enslavers. One of Michigan’s statues depicts Lewis Cass, an enslaver who was also involved in the Trail of Tears. (The state legislature voted this month to replace it.) Vermont, the first state to outlaw slavery in its constitution, sent a statue of Ethan Allen, whose brother and daughter both enslaved people illegally, and who had Black servants in his household. Historians have not been able to determine whether those servants were enslaved. California is represented by Junípero Serra, a Catholic missionary who some historians say enslaved Indigenous people in his missions, forcing them to work and punishing them with whippings if they tried to escape. Others deny that he was an enslaver and emphasize his work to improve the lives of Indigenous people.