|

|

UNDER CONSTRUCTION - MOVED TO MIDDLEBORO REVIEW AND SO ON https://middlebororeviewandsoon.blogspot.com/

|

|

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The West Virginia senator just sold out not only his political party, but also the privacy rights of 51 percent of the population.

The Women’s Health Protection Act, which was introduced in 2013, would enshrine the right to abortion in federal law, while blocking many of the abortion restrictions that have passed in several states. The House passed the bill last September, largely along party lines. The bill would eliminate a list of what proponents describe as “medically unnecessary” antiabortion restrictions, including mandatory waiting periods, antiabortion counseling, telemedicine bans and various regulations on the layout, structure and staffing policies at abortion clinics, which have forced many clinics to shutter.

This, of course, was set up in reaction to the surge in anti-choice legislation out in the states, but it also gained increased urgency as the realization set in that the Supreme Court likely will gut Roe v. Wade later this year. The House passed the WHPA last fall. At which point it moved into the Senate, where, as we know, almost nothing moves at all. Enter Joe Manchin, forever ready for his close-up.

The measure, introduced by Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) and Sen. Tammy Baldwin (D-Wis.), was co-sponsored by all but two Democratic senators, Joe Manchin III of West Virginia and Robert P. Casey Jr. of Pennsylvania, who are both opposed to abortion. “This vote will be a rallying cry in November,” said Blumenthal at a news conference before the vote. “This vote is going to awaken a lot of people, men and women, who grew up taking reproductive rights for granted.”

Maybe so. But Joe Manchin won’t care. Remember, he voted on Monday not against the WHPA, but rather, against the idea of debating the bill at all. No matter how fervently anti-choice you are, there is no coherent moral position in refusing to debate the issue. (This is exactly the fight waged for eight years by Rep. John Quincy Adams against the congressional “gag rule,” by which the House would automatically table any petitions regarding slavery.) It also renders false all the arguments against the filibuster based on the Senate’s alleged right to virtually unlimited debate. If you vote against debate, it can be fairly said, you are voting to limit debate. And there is no point any longer to Joe Manchin. None at all.

Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky. (photo: Presidency of Ukraine/Handout/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky. (photo: Presidency of Ukraine/Handout/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

Why it matters: Zelensky has said since the start of Russia's unprovoked invasion of Ukraine that he would be a prime target for assassination. Last Thursday, he warned that Russian "sabotage groups" had entered Kyiv and were hunting for him and his family.

The big picture: According to the Telegram message, Danilov said that a unit of elite Chechen special forces, known as Kadyrovites, had been behind the plot and had subsequently been "eliminated."

Go deeper: What to know about Ukraine's wartime president

Heavily-armed National Guard troops exit Leona Vicario, a federally-run shelter, in Juarez, Mex., on Feb. 2, 2022. (photo: John Washington/Intercept)

Heavily-armed National Guard troops exit Leona Vicario, a federally-run shelter, in Juarez, Mex., on Feb. 2, 2022. (photo: John Washington/Intercept)

Migrants are being detained in squalid conditions in Juárez, Mexico, amid the Biden administration’s court-ordered reboot of the program.

The El Paso, Texas, immigration court where the Migrant Protection Protocols hearings took place was beset, on the day I visited in early February, by a series of logistical and legal hitches. One of the missing asylum-seekers was out because of chicken pox, two had Covid-19, and one was simply MIA. The judge ruled that the last one be ordered deported in absentia (that is, deported from a country he was not in to a country he feared returning to), but then she received word that he’d shown up at the port of entry; she retracted his deportation order and retired to her chamber. The court has no way to contact asylum-seekers enrolled in the program, and there was nothing to do but wait.

The judge and the government prosecutor were also repeatedly confused about who was scheduled for the hearings and what their status was. The single MPP enrollee who was actually in court that day said he was scared of being returned to Mexico. The judge scheduled his non-refoulement interview — designed as a safeguard for people who would be in danger of waiting out their cases in Mexico — for later in the day. It was already nearly 2 p.m., and migrants are supposed to have at least 24 hours to prepare for the interview and look for an attorney. The Executive Office for Immigration Review, the Justice Department agency that runs immigration courts, did not respond to requests for comment.

The U.S. Supreme Court is now set to decide whether to standardize such proceedings and vastly expand MPP, which, critics claim, continues to be a catastrophe for due process and protecting migrants. Introduced by President Donald Trump in 2018, the program, also known as “Remain in Mexico,” returns asylum-seekers south of the border to wait for an immigration court date — a chance to make their case for asylum. In practice, MPP thrusts asylum-seekers into the hands of criminal networks and corrupt government agents in notoriously dangerous Mexican border cities.

The high court recently granted the Biden administration’s request to review a decision by the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals in Biden v. Texas, a case brought by Texas and Missouri challenging the administration’s termination of the Migrant Protection Protocols.

Shortly after taking office, President Joe Biden sought to end the program — his administration issued two memos citing its numerous pitfalls and dangers — but Texas and Missouri sued, saying that because they had to offer driver’s licenses to immigrants allowed into the country, they had been “actually injured” by the termination.

Last summer, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas ruled that the government had to return asylum-seekers to Mexico if it didn’t have sufficient resources to detain them. In response, the Biden administration asked the Supreme Court to intervene, but the court refused to block the ruling, and the Biden administration was forced to restore the program in early December. But instead of a simple restart, it expanded the program — while Trump’s MPP impacted asylum-seekers from Spanish-speaking countries and Brazil, Biden extended its reach to include asylum-seekers from throughout the Western Hemisphere — though actual reimplementation has been slow.

Most asylum-seekers who cross into the United States from Mexico today are summarily expelled under a widely criticized public health policy known as Title 42, which is based on a debunked claim that migrants pose a health threat to the United States. Begun by Trump and continued by Biden, Title 42 is one of the largest restrictions on access to asylum in U.S. history. Those who make it past Title 42’s few exceptions can be paroled into the United States, temporarily allowed into the country and given court dates to continue their asylum claims, while others are detained.

As of February 22, nearly three months into MPP’s restart, the Department of Homeland Security had returned less than 800 migrants to Mexico. Despite the program currently being applied to only a small percentage of asylum-seekers in three border cities, the Supreme Court ruling could have enormous consequences.

The legal statute that Texas and Missouri are trying to force the federal government to abide by comes from a 1996 law that requires mandatory detention of migrants not legally admissible to the country. Prior administrations have worked around the mandatory detention requirement, relying on congressional carveouts as well as submitting to the reality that the government has never had anywhere near the capacity to detain all inadmissible migrants. If the Supreme Court rules in favor of the states this summer, the government would have to detain as many migrants as it can — currently over 100,000 people a month are crossing the U.S.-Mexico border without permission or proper documentation — and push the rest of them back into Mexico, either enrolled into MPP or summarily expelled without any legal recourse for requesting asylum, which would not only put them in danger but also further rattle U.S.-Mexico relations.

A ruling in the states’ favor, as Yael Schacher, deputy director for the Americas and Europe at Refugees International, told me, “would be a huge boon for the private prison companies,” which run detention centers that house about 80 percent of all detained immigrants and annually rake in billions of dollars from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement contracts. It would also further eviscerate current U.S. asylum procedures and set a stark example for the undermining of refugee protocols throughout the world. As Schacher put it, summarizing Texas and Missouri’s lawsuit: “They want to kill asylum.”

A cold snap had set into West Texas and northern Chihuahua, and asylum-seekers in Juárez, Mexico, were crammed into roof-leaking shelters throughout the city.

In Juárez, the largest federally run migrant shelter is Leona Vicario, which first opened in 2019 to temporarily house migrants from the first iteration of MPP. Today it’s where most migrants enrolled in the program in courts in El Paso — which is separated from Juárez by the Rio Grande — are forced to wait.

Outside the shelter, the Mexican National Guard, whose core mission includes a mandate to “stop all migration,” keeps tight perimeter security. The security force has been repeatedly implicated in serious human rights abuses, and its combat-ready troops busied themselves jumping in and out of machine gun-mounted trucks just outside the entrance.

I was denied entrance to the shelter by guards out front and by an official with Mexico’s Secretariat of Labor and Social Welfare, the agency that runs the shelter, but I tracked down a few asylum-seekers who were staying or had recently stayed there. One Central American man, who I’ll call Mateo, was enrolled in MPP in December and has been staying in Leona Vicario ever since. (Along with all the other asylum-seekers I spoke with for this article, he feared retaliation and asked for his name and nationality not to be used.) Mateo described the shelter’s prison-like conditions, bad and insufficient food, filthy bathrooms, excessive cold, and lack of Covid precautions, including not quarantining people who were infected and guards not using masks. One of the guards, Mateo said to me, has repeatedly told some of the migrants, “You don’t belong here. You’re worth shit.” Another guard with a reputation for being a martinet told a Venezuelan man enrolled in MPP that he would disappear him if he didn’t comply with the rules.

Those rules are exacting. All the migrants are required to hand over their cellphones every night at 8 p.m. The phones are returned to the migrants the next morning between 6:30 and 8 a.m. Those who are late have their phones confiscated for three days. Migrants are allowed to leave, but only for two hours a week and only if they have a specific reason, such as receiving a wire transfer. “It’s a nightmare in here,” Mateo said. The Mexican Secretariat of Labor and Social Welfare didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Mateo’s path to Leona Vicario is emblematic of the various obstacles blocking access to asylum in the United States today. He had first tried to cross into the United States outside Yuma, Arizona, in early December but was expelled under Title 42. Shortly afterward, he tried again outside Juárez, where he turned himself over to Border Patrol agents and told them he wanted to apply for asylum. They enrolled him in MPP, and he attended his first hearing in early January. He was sent for a non-refoulement interview, during which he described having been robbed multiple times on his trip through Mexico, including by state police and in the presence of the National Guard. Still, he failed the interview and was sent back to the shelter. He is due to appear in court again later this month.

“The situation, what can I say, you have to be here to understand,” Mateo said. “We are miserable. They know what they’re doing to us, sending us back to a country as corrupt as Mexico.”

Another MPP enrollee at the shelter, Andrés, told me that he suffered what he suspects was a severe PTSD-induced panic attack after being previously kidnapped for over a month in southern Mexico. His heart began beating painfully fast, his left arm swelled, and he felt an intense and unrelenting itch in his hand. As the pain in his arm and chest increased, he asked officials repeatedly to be taken to the hospital but was ignored. “Not until I defecated in my pants, the pain was so bad, did they listen to me,” he said.

Later, Andrés told me, guards confiscated his Bible because he was using it to preach. The explanation the guards gave him, he said, amounted to: “If you don’t like the rules, there’s the door.” Out that door, however, lurked police and criminal groups — both of which are known to prey on migrants.

A 2021 report from Human Rights First found hundreds of cases of kidnappings or other forms of attacks targeted at expelled asylum-seekers. Another report from Human Rights Watch found that half of the asylum-seekers who were enrolled in MPP and surveyed by researchers reported that Mexican officials targeted them for extortion. In some cases, Mexican officials threatened to turn them over to cartels if they didn’t pay.

“It is functionally impossible for shelters in Mexico to work without cooperating with and paying the cartels,” immigration attorney Taylor Levy told me. Levy described such shelters as “kidnapping magnets” and explained that Mexican National Guard members are known to accept money from migrant smugglers. Nicolas Palazzo, an attorney at Las Americas, an immigrant advocacy center in El Paso, put it to me bluntly: “There’s no humane version of MPP.”

There is a smattering of other shelters in Juárez, where hundreds of asylum-seekers — both MPP enrollees and people expelled by Title 42 — wait in precarious limbo. At one church-run shelter, when some of the migrants saw me conducting an interview, they assumed that I was a lawyer and began to form a line to speak with me. I explained that I was a journalist, not an attorney, and couldn’t offer legal advice. The line didn’t dissipate.

As I was leaving another shelter, a woman stepped in front of me and began breathlessly telling me a story about a series of awful sexual assaults she had experienced, explaining how she was certain that if she ever returned to Honduras she would be immediately murdered by her ex-boyfriend or his fellow gang members. When I began to react, she cut me off: “I know you can’t help me,” she said. “I just needed to tell someone I could trust.” We hadn’t even exchanged names.

Hannah Hollandbyrd, a policy specialist at Hope Border Institute, described how Mexico was simply not equipped to deal with the number of asylum-seekers being pushed back from the United States.

“We don’t have a policy right now,” Hollandbyrd said. “We have a scattershot approach. And it’s really about the U.S. putting people in danger. MPP is denying asylum access to extremely vulnerable people.”

It’s now up to the Supreme Court to decide whether pushing asylum-seekers into danger will become standard policy.

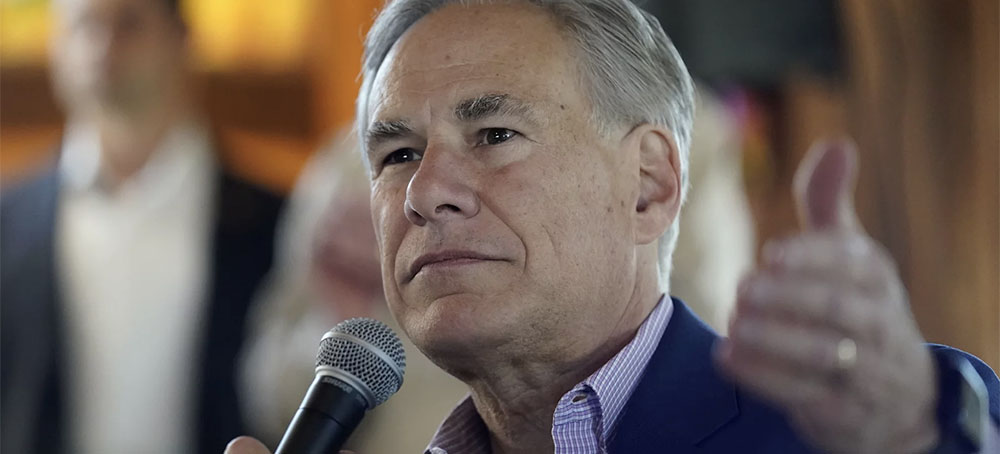

The ACLU of Texas argues that Gov. Greg Abbott's instructions to investigate parents of transgender adolescents were issued without proper authority, in violation of a Texas law and the state constitution and violate the constitutional rights of transgender youth and their parents. (photo: Eric Gay/AP)

The ACLU of Texas argues that Gov. Greg Abbott's instructions to investigate parents of transgender adolescents were issued without proper authority, in violation of a Texas law and the state constitution and violate the constitutional rights of transgender youth and their parents. (photo: Eric Gay/AP)

The suit, filed on Tuesday, is aimed at stopping the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services from enacting Gov. Greg Abbott's orders to investigate parents and doctors who provide trans children with gender-affirming care.

Abbott has also suggested parents should be prosecuted. His order follows Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton's nonbinding opinion last month that providing access to sex reassignment surgery, puberty blockers, testosterone and estrogen treatments all constitute child abuse.

"No family should have to fear being torn apart because they are supporting their trans child," Adri Pérez, policy and advocacy strategist at the ACLU of Texas, said in a statement.

The ACLU argues that the governor's instructions were issued without proper authority, in violation of a Texas law and the state constitution, and violate the constitutional rights of transgender youth and their parents. The complaint names Abbott, DFPS Commissioner Jaime Masters and the DFPS as defendants.

Medical organizations including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Pediatric Endocrine Society, the American Medical Association and the American Psychological Association have condemned state government efforts to restrict access to gender-affirming care for minors, saying it dangerously interferes with necessary medical care.

The lawsuit was filed on behalf of a DFPS employee called Jane Doe, who "works on the review of reports of abuse and neglect"; the woman's husband, John Doe; and their 16-year-old transgender daughter, Mary Doe.

Lawyers say Jane Doe has been placed on leave from her job because her daughter is undergoing a transition and that the family has already had an investigator show up at their door and interview the parents and Mary. The investigator also sought access to Mary's medical records, the plaintiffs say.

Abbott's order, Paxton's opinion and the investigation have "terrorized the Doe family and inflicted ongoing and irreparable harm," their lawyers say.

The ACLU is also representing Houston-based psychologist Megan Mooney, who works with youth who have gender dysphoria. According to the complaint, Abbott's directive has put Mooney in an "untenable position."

Under Texas law, she is a mandatory reporter, which means she could lose her license and face civil and criminal penalties if she ignores Abbott's directive. However, by following them, the ACLU of Texas says she "would be violating her professional standards of ethics and inflict serious harm and trauma on her clients."

Some district attorneys in Texas have already said they will not investigate or prosecute cases of gender-affirming care for trans children.

Harris County District Attorney Kim Ogg is among those defying the order. "I will not prosecute any parent, any facility, or anyone else for providing medically appropriate care to transgender children," Ogg said, as reported by Texas Public Radio.

People vote at the Brooklyn Museum in New York City. (photo: Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

People vote at the Brooklyn Museum in New York City. (photo: Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

About 800,000 green card holders and others authorized to work in the country will become eligible to vote for mayor, City Council and other local offices.

Like most school board elections in America, turnout was low, producing opportunities for small voting blocs to shape the outcome. One group of concerned parents saw the opening: immigrants.

New York’s school board races stood out among American elections because they allowed noncitizen parents to vote, and Dominicans in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Manhattan helped mobilize 10,000 parents to register. Among those they installed: Guillermo Linares, who went on to become the first Dominican-born elected official in the United States, serving on the City Council and state Assembly.

“People were voting to make a difference in the education system,” said Maria Luna, a longtime community activist and a Democratic district leader, who said the benefits of the effort extended beyond the immigrant community. “The priority was to get better education and to build more schools for everybody. … It was really, really important for the benefit of children.”

New York put its mayor in charge of schools in 2002, shuttering the local boards and ending noncitizen voting with them.

Now, two decades later, a national movement to give voting rights to legal noncitizens has found its way to the country’s most populous city and, pending court battles, will soon give those immigrants the chance to shape local elections.

About 800,000 green card holders and others authorized to work in the country will become eligible to vote for mayor, City Council and other local offices. New York is by far the largest city to make such a move.

The impact on local elections could potentially be far-reaching. The city’s electorate consists of just under 5 million active registered voters, meaning a major push to register immigrants and get them to the polls could reshape politics in New York. Voting blocs like the one that elected Linares could have the power to affect the outcome of not just City Council races but even the next mayoral race.

Proponents say noncitizen voting will give more political clout to communities whose concerns have often been overlooked, and force candidates and elected officials to be responsive to a broader swath of the population. Opponents — who are challenging the law in court — predict it could be a logistical nightmare, and charge the increased influence for immigrant voters could come at the expense of U.S.-born Black voters.

Noncitizens will be able to register to vote in December, and participate in elections starting in 2023. The first big test will be a City Council primary set for June of next year. All Council members will be up for reelection after just two years because of redistricting. And Mayor Eric Adams, who signed the law despite some reservations, will have to build his 2025 reelection strategy around a changed voting demographic should he seek another term.

“Every voter who’s able to turn out is good for our democracy,” said Nora Moran, director of policy and advocacy at United Neighborhood Houses, a progressive nonprofit group that supported the bill. “One of the whole purposes of the bill is not only to bring people’s voices in, but make elected leaders more accountable to their neighborhoods and push them in a direction of being more responsive.”

Noncitizen voting, then and now

New York wasn’t alone in allowing some form of noncitizen voting in years past: as many as 40 states practiced it at some point from the 18th century through the early 20th century, according to research by Ron Hayduk, a professor at San Francisco State University who has studied noncitizen voting, including the New York school board election. The practice was abolished in the last of those states nearly a hundred years ago.

A handful of states have explicitly banned noncitizen voting in recent years even though they already restricted voting to U.S. citizens.

Today, 11 cities and towns in Maryland allow noncitizens to vote in local elections, and two jurisdictions in Vermont have voted to authorize it. San Francisco allows noncitizens to vote in school board elections only.

Takoma Park in Maryland has 13,000 registered voters, a few hundred of whom are noncitizens. Turnout among noncitizens has ranged from single digits to over a third.

“When people find out they’re eligible to register and vote, they’re often pleasantly surprised to learn that and appreciate the opportunity. We really view ourselves as an inclusive community, and want to make sure everyone feels welcome here,” said Jessie Carpenter, Takoma Park’s city clerk.

But given the demographics, the impact on local races has been limited. “It doesn’t necessarily have an effect on our elections. The numbers are pretty small, compared to our total voter population,” Carpenter said.

In New York City, which has been a magnet for immigrants from around the world since its inception, the change could be further reaching.

Dominicans are the largest group of immigrants in the city, numbering nearly 400,000, of all immigration statuses. China is the second biggest country of origin, followed by Jamaica, Mexico, Guyana, Ecuador and Bangladesh.

In an overwhelmingly Democratic metropolis, their political preferences are diverse.

“South Asians seem to be relatively progressive in their voting, while East Asians this year moved a little to the right. And Dominicans, I think, are still relatively progressive while South Americans are somewhat more moderate,” said Jerry Skurnik, a political consultant who focuses on demographic analysis. “If it turns out a significant number of noncitizens are voting, those differences will matter.”

New York City estimates just under 10 percent of its population consists of green card holders and immigrants with other legal statuses, roughly the group covered by the noncitizen voting legislation, according to data gathered by the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs.

The city is home to some 3 million immigrants, most of whom are already naturalized citizens. Another 476,000 are undocoumented immigrants who will not be eligible to vote under the new law.

Noncitizens could influence a citywide race — especially a close election under the city’s new ranked choice voting system, which saw Adams triumph by just a few thousand votes over his nearest challenger in the final round. But the biggest changes are likely to occur in local races in immigrant-rich neighborhoods.

In the 1980s, when New York had its local school board system, the efforts to organize noncitizen voters and other immigrants “elevated the plight of their students and these families, including out of date school books, overcrowded schools,” Hayduk said. That meant the school system and the city spent more money to improve those issues.

Now, he said, noncitizen voting will lead to changes at City Hall.

“The greatest impact is going to be on the City Council,” Hayduk said. “That’s where I think you’ll see the greatest potential for immigrant communities to organize.”

City statistics suggest that places like Flushing and Jackson Heights, both in Queens, will see the most shake-up in their voter base.

While the city does not measure the precise population covered by the voting legislation, it has tracked lawful permanent residents who are eligible to become citizens but have not done so.

Flushing in Queens — home to many Chinese and Korean immigrants — topped the list for that population, followed by Jackson Heights and north Corona. Then came Washington Heights and Inwood in Manhattan, where there is still a large population of Dominican immigrants, Sunnyside and Woodside in Queens, Bensonhurst and Bath Beach in Brooklyn, and Elmhurst and south Corona in Queens.

Each of the top ten districts is home to 15,000 or more immigrants eligible for naturalization, the city’s data show.

When City Council Member Shekar Krishnan was campaigning for his seat last year in Jackson Heights and Elmhurst, he made a point of reaching out to constituents with roots around the world in a mostly Latino and Asian district.

“Residents would come up to me when I was out door knocking and out on Election Day and say, ‘We support all of your policies, but we aren’t able to vote for you,’” Krishnan, a Democrat and former civil rights lawyer, said.

Krishnan said the lack of voting rights has translated into less attention from city government for issues including debt-laden taxi drivers and pandemic aid for immigrant workers ineligible for federal help.

“I don’t think it was any accident that the city, throughout this pandemic, ignored the needs of our most essential workers,” he said. “It was the biggest failure of city government during this pandemic, but it was no accident.”

‘I don’t think it ever goes into effect’

Opposition to the noncitizen voting law has come from Republicans and some Democrats.

Laurie Cumbo, a Democrat who was City Council majority leader at the time, argued during the debate on the law at a Council meeting that introducing hundreds of thousands of new immigrant voters would dilute the power of Black voters.

In areas like upper Manhattan — home to large Black and Latino communities as well as an influx of newer white residents — she said the bill could shift the balance of power against Black voters. She cited an increase in votes for former President Donald Trump in immigrant neighborhoods in the 2020 election.

“This particular legislation is going to shift the power dynamics in New York City in a major way,” Cumbo said. “The only thing that many African American communities have left are their Black representatives and representation.”

Republicans quickly sued to stop the noncitizen voting law, arguing it is illegal under the state constitution and state election law. More recently, a conservative legal group filed a lawsuit on behalf of a group of Black voters, charging that the law is racially discriminatory.

New York’s constitution says that every citizen is entitled to vote as long as they are at least 18 years old and have lived in the jurisdiction for 30 days. The Republicans’ suit also cites a state election law that says no one shall be qualified to register to vote unless they are a citizen of the United States. The city filed a response on Friday, denying any violations of the law.

The court battle could get more complicated, depending on how the city Board of Elections moves to implement the law. The city law requires the board to produce a report on its plans by July, but the city Board of Elections recently punted and sent a letter to the state Board of Elections asking how to proceed. The board is evenly split between Democrats and Republicans.

“I don’t think it ever goes into effect,” City Council Republican minority leader Joe Borelli said of the noncitizen voting law. “I can tell you with certainty, none of the five Republicans [BOE commissioners] will be voting to take any action on this. And their rationale is state law prohibits us.”

BOE has not heard back from the state board but expects to meet the July deadline, a spokesperson said.

John Ketcham, a fellow with the conservative think tank the Manhattan Institute, warned of unintended consequences if the new voting system does proceed.

The BOE, which has become notorious for a history of election flubs, would be charged with maintaining voter lists distinguishing who is eligible to vote in which elections, and making sure voters are given the correct ballots. (City elections are held on odd years, but there are cases like district attorney races where state elections are held at the same time.)

“The Board of Elections has chronic and systemic problems that will certainly contribute to their difficulty in administering this,” Ketcham said.

Noncitizens who erroneously vote in federal or state elections could face legal consequences — and even those who vote legally at the municipal level will be required to explain themselves when applying for U.S. citizenship, Ketcham said.

“It’s not worth putting our noncitizen voters at that risk of jeopardy,” he said.

'These comments point to a pernicious racism that permeates today's war coverage and seeps into its fabric like a stain that won't go away.' (photo: Peter Lazar/AFP/Getty Images)

'These comments point to a pernicious racism that permeates today's war coverage and seeps into its fabric like a stain that won't go away.' (photo: Peter Lazar/AFP/Getty Images)

Are Ukrainians more deserving of sympathy than Afghans and Iraqis? Many seem to think so

If this is D’Agata choosing his words carefully, I shudder to think about his impromptu utterances. After all, by describing Ukraine as “civilized”, isn’t he really telling us that Ukrainians, unlike Afghans and Iraqis, are more deserving of our sympathy than Iraqis or Afghans?

Righteous outrage immediately mounted online, as it should have in this case, and the veteran correspondent quickly apologized, but since Russia began its large-scale invasion on 24 February, D’Agata has hardly been the only journalist to see the plight of Ukrainians in decidedly chauvinistic terms.

The BBC interviewed a former deputy prosecutor general of Ukraine, who told the network: “It’s very emotional for me because I see European people with blue eyes and blond hair … being killed every day.” Rather than question or challenge the comment, the BBC host flatly replied, “I understand and respect the emotion.” On France’s BFM TV, journalist Phillipe Corbé stated this about Ukraine: “We’re not talking here about Syrians fleeing the bombing of the Syrian regime backed by Putin. We’re talking about Europeans leaving in cars that look like ours to save their lives.”

In other words, not only do Ukrainians look like “us”; even their cars look like “our” cars. And that trite observation is seriously being trotted out as a reason for why we should care about Ukrainians.

There’s more, unfortunately. An ITV journalist reporting from Poland said: “Now the unthinkable has happened to them. And this is not a developing, third world nation. This is Europe!” As if war is always and forever an ordinary routine limited to developing, third world nations. (By the way, there’s also been a hot war in Ukraine since 2014. Also, the first world war and second world war.) Referring to refugee seekers, an Al Jazeera anchor chimed in with this: “Looking at them, the way they are dressed, these are prosperous … I’m loath to use the expression … middle-class people. These are not obviously refugees looking to get away from areas in the Middle East that are still in a big state of war. These are not people trying to get away from areas in North Africa. They look like any.” Apparently looking “middle class” equals “the European family living next door”.

And writing in the Telegraph, Daniel Hannan explained: “They seem so like us. That is what makes it so shocking. Ukraine is a European country. Its people watch Netflix and have Instagram accounts, vote in free elections and read uncensored newspapers. War is no longer something visited upon impoverished and remote populations.”

What all these petty, superficial differences – from owning cars and clothes to having Netflix and Instagram accounts – add up to is not real human solidarity for an oppressed people. In fact, it’s the opposite. It’s tribalism. These comments point to a pernicious racism that permeates today’s war coverage and seeps into its fabric like a stain that won’t go away. The implication is clear: war is a natural state for people of color, while white people naturally gravitate toward peace.

It’s not just me who found these clips disturbing. The US-based Arab and Middle Eastern Journalists Association was also deeply troubled by the coverage, recently issuing a statement on the matter: “Ameja condemns and categorically rejects orientalist and racist implications that any population or country is ‘uncivilized’ or bears economic factors that make it worthy of conflict,” reads the statement. “This type of commentary reflects the pervasive mentality in western journalism of normalizing tragedy in parts of the world such as the Middle East, Africa, south Asia, and Latin America.” Such coverage, the report correctly noted, “dehumanizes and renders their experience with war as somehow normal and expected”.

More troubling still is that this kind of slanted and racist media coverage extends beyond our screens and newspapers and easily bleeds and blends into our politics. Consider how Ukraine’s neighbors are now opening their doors to refugee flows, after demonizing and abusing refugees, especially Muslim and African refugees, for years. “Anyone fleeing from bombs, from Russian rifles, can count on the support of the Polish state,” the Polish interior minister, Mariusz Kaminski, recently stated. Meanwhile, multiple reports indicate that Polish border guards are actively and forcibly turning away African students who were studying in Ukraine, thereby preventing them from crossing into safety.

In Austria, Chancellor Karl Nehammer stated that “of course we will take in refugees, if necessary”. Meanwhile, just last fall and in his then-role as interior minister, Nehammer was known as a hardliner against resettling Afghan refugees in Austria and as a politician who insisted on Austria’s right to forcibly deport rejected Afghan asylum seekers, even if that meant returning them to the Taliban. “It’s different in Ukraine than in countries like Afghanistan,” he told Austrian TV. “We’re talking about neighborhood help.”

Yes, that makes sense, you might say. Neighbor helping neighbor. But what these journalists and politicians all seem to want to miss is that the very concept of providing refuge is not and should not be based on factors such as physical proximity or skin color, and for a very good reason. If our sympathy is activated only for welcoming people who look like us or pray like us, then we are doomed to replicate the very sort of narrow, ignorant nationalism that war promotes in the first place.

The idea of granting asylum, of providing someone with a life free from political persecution, must never be founded on anything but helping innocent people who need protection. That’s where the core principle of asylum is located. Today, Ukrainians are living under a credible threat of violence and death coming directly from Russia’s criminal invasion, and we absolutely should be providing Ukrainians with life-saving security wherever and whenever we can. (Though let’s also recognize that it’s always easier to provide asylum to people who are victims of another’s aggression rather than of our own policies.)

But if we decide to help Ukrainians in their desperate time of need because they happen to look like “us” or dress like “us” or pray like “us,” or if we reserve our help exclusively for them while denying the same help to others, then we have not only chosen the wrong reasons to support another human being. We have also, and I’m choosing these words carefully, shown ourselves as giving up on civilization and opting for barbarism instead.

A harvester gathers wheat from a field near the Krasne village in Ukraine's Chernihiv area. (photo: Anatolii Stepanov/FAO/AFP)

A harvester gathers wheat from a field near the Krasne village in Ukraine's Chernihiv area. (photo: Anatolii Stepanov/FAO/AFP)

The near future looks grim for the countries in the Middle East and North Africa that depend on the Russian and Ukrainian wheat imports due to the war between the two, experts warn.

Russia is the world’s number-one wheat exporter – and largest producer after China and India – Ukraine is among the top five wheat exporters worldwide.

“The wheat harvest starts in July and this year’s yield is expected to be a healthy one, meaning abundant supply for global markets in normal conditions. But a protracted war in Ukraine can affect the harvest in that country, and therefore global supplies,” Karabekir Akkoyunlu, a lecturer in politics of the Middle East at SOAS, University of London, told Al Jazeera.

In addition, the planned expulsion of some Russian banks from the international SWIFT banking system in retaliation for Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine is expected to hit the country’s exports.

“At a time of global food crisis and supply chain disruptions due to the coronavirus pandemic, this is a real concern and it is already pushing prices up to record levels,” he said.

Rising prices, insufficient supply

Though Turkey domestically produces about half of the wheat it consumes, it has become increasingly reliant on imports, 85 percent of which come from Russia and Ukraine.

Ankara’s wheat imports from Ukraine reached record levels in 2021, according to official data from the Turkish Statistics Institute.

“The Turkish government says the country has the production capacity to make up for the loss in wheat imports, but even so, this will push up the costs significantly,” Akkoyunlu said.

“A protracted war will make a difficult year worse for the average Turkish citizen, who have already seen their bread get lighter but more expensive, and are having to pay record electricity bills.”

“Nearing an election year, this will increase the pressure on the [President Recep Tayyip] Erdogan government, which is losing ground to the opposition in most opinion polls,” he said.

In recent months, huge queues of people waiting to buy subsidised bread have popped up in different districts of Istanbul, as cash-strapped citizens trade their time to save a few lira on bread as soaring inflation and the battered Turkish currency have driven up costs and dealt a severe blow to purchasing power.

Rising prices and insufficient supply have already affected economically-depressed countries in the Middle East and North Africa that buy the bulk of their wheat from Russia and Ukraine, bringing them to the brink of crisis.

“Ukraine supplies a huge amount of the grain to most of these countries and a lot of these places are already on a knife’s edge. The least little thing that disturbs bread prices even more could really kick off a lot of turmoil,” Monica Marks, a professor of Middle East politics at New York University Abu Dhabi, told Al Jazeera.

“Unlike Turkey, most economies in the Arab world are heavily dependent on wheat imports. Egypt is far out on the dependent end of the spectrum. Egypt relies on Russia and Ukraine for 85 percent of its wheat imports, Tunisia relies on Ukraine for between 50 and 60 percent of its wheat imports,” she said.

Marks said that Tunisia is already “absolutely up against a wall economically … a lot of people in Tunisia talk about the potential for a Lebanon scenario, and they are not crazy”.

She cited reports that the Tunisian government has already been unable to pay for incoming wheat shipments, and said there have been widespread shortages of grain products such as pasta and couscous, which constitute a significant portion of the Tunisian diet.

Akkoyunlu also noted that Egypt, Tunisia and Lebanon, in addition to Yemen and Sudan are at great risk from a surge in prices and a spike in demand.

While war between Russia and Ukraine intensifies, a potential decrease in wheat exports from their fertile lands will be felt in vulnerable countries all the way from the edge of North Africa to the Levant.

Marks said that while Morocco is not as dependent on some of its neighbours on wheat imports, it is currently experiencing its worst drought in 30 years, resulting in a surge in food prices that will eventually force the government to raise grain imports and subsidies.

“There is also a lot of heavy dependency, even in countries that are flush with hydrocarbon resources that we assume because of that would be in a better position to weather the storm, like Algeria or Libya,” Marks said.

Given bread’s role as a politically-charged commodity in this part of the world, further strain on wheat supply and escalating prices could even spark revolt.

“Bread has been a key cause and symbol of popular uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia going back to the 1970s and 80s. The Egyptian revolution in 2011 was preceded by a major drought in Eurasia and a corresponding rise in bread prices,” Akkoyunlu said.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

LOTS OF POSTS IGNORED BY BLOGGER..... ALL POSTS ARE AVAILABLE ON MIDDLEBORO REVIEW AND SO ON DOJ Deleted an Epstei...