The World Wildlife Foundation, in collaboration with the Zoological Society of London, recently issued an eye-popping description of the forces of humanity versus life in nature, the Living Planet Report 2020, but the report should really be entitled the Dying Planet Report 2020 because that’s what’s happening in the real world. Not much remains alive.

The report, released September 10th, describes how the over-exploitation of ecological resources by humanity from 1970 to 2016 has contributed to a 68% plunge in wild vertebrate populations, inclusive of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles and fish.

The report offers a fix-it: “Bending the Curve Initiative,” described in more detail to follow. The causes of collapse are found in human recklessness and/or neglect of ecosystems. It’s partially fixable (maybe) but don’t hold your breath.

What if stocks plunged 68%? What then? Why, of course, that is an all-hands-on-deck panic scenario with the Federal Reserve Bank repeatedly pressing “a white hot printing press button,” hopefully, avoiding destructive deflationary forces looming in the background. But, an astounding jaw-dropping 68% loss of vertebrates doesn’t seem to budge the panic needle nearly enough to count.

Of special note, according to the Report, tropical sub-regions were clobbered, hit hard with 94% loss of vertebrate life, which is essentially total extinction. For comparison purposes, the worst extinction event in history, the Permian-Triassic, aka: the Great Dying, of 252 million years ago took down 96% of marine life and has been classified as “global annihilation.”

According to the Report, on a worldwide basis, two-thirds (2/3rds) of wild vertebrate life has vanished in only 46 years or within one-half a human lifetime. That is mind-boggling, and it is indicative of misguided mindlessness, prompting a query of what the next 46 years will bring. What remains is an operative question?

According to the report: “Until 1970, humanity’s Ecological Footprint was smaller than the Earth’s rate of regeneration. To feed and fuel our 21st century, we are overusing the Earth’s biocapacity by at least 56%.” (Report, page 6) Meaning, we’ve gone from equilibrium to a huge deficit of 50% in less than 50 years. Putting it mildly, that’s terrifying!

As stated in the Report, we’re effectively using and abusing and trampling the equivalence of one and one-half planets. How long does that last? The experience of the past 46 years provides an answer, which is: Not much longer.

The denuding, destructing of natural biodiversity is almost beyond description, certainly beyond human comprehension, which may be a big part of the problem of recognition. Still, by and large, people read the World Wildlife Foundation report and continue on with business as usual. This lackadaisical behavior by the public has been ongoing for decades and not likely to end anytime soon. Therefore, an eureka moment of radical change in farming practices and ecosystem husbandry is almost too much to wish for after years, and years, of preaching by environmentalists about the ills associated with the anthropogenic growth machine.

In all, with ever-faster approaching finality, and worldwide failure to act to save the planet, the answer may be that people must learn to adapt to a deteriorating world.

More to the point, the Report is “an extermination report.” Consider the opening sentence: “At a time when the world is reeling from the deepest global disruption and health crisis of a lifetime, this year’s Living Planet Report provides unequivocal and alarming evidence that nature is unraveling and that our planet is flashing red warning signs of vital natural systems failure.” (Report, page 4)

Accordingly, unequivocally “nature is unraveling.” And, the planet is “flashing red warning signs of vital natural systems failure.”

Why repeat that disheartening info? Simply put, it demands repeating over and over again. Yes, “nature is unraveling.” And, by all indications, time is short as “flashing red warning signs” are crying for help. But, will it happen? Or, does biz as usual rattle onwards towards total extinction of life way ahead of anybody’s best guess, which, based upon how rapidly the forces of the anthropocene are gobbling up the countryside, could be within current lifetimes. But, honestly, who knows when?

Still, with great hope but not enough fanfare, the Report proposes a new research initiative called “Bending the Curve Initiative” to reverse biodiversity loss via (1) unprecedented conservation measures and (2) a total remake of food production techniques.

One of the upshots of the breakdown in nature is the issue of “adequate food for humanity.” Accordingly: “Where and how we produce food is one of the biggest human-caused threats to nature and to our ecosystems, making the transformation of our global food system more important than ever,” Ibid

Which implies the end of rainforests obliteration, the end of industrial farming, full stop, eliminating mono-crop farming, and “stopping dead in its tracks” the use of toxic, deadly insecticides, which kill crucial life-originating ecosystems by bucketloads, as for example, 75% loss of flying insects over 27 years in nature reserves in portions of Europe (Source: Krefeld Entomological Society, est. 1905).

What kills 75% of flying insects?

Additionally, the Report recognizes the necessity of “transformation of the prevailing economic system.” Meaning, a transformation away from the radical infinite growth hormones that are attached to the world’s lowest offshore wages and lowest offshore regulations as an outgrowth of neoliberalism, which is rapidly destroying the world. It’s a terminal illness that’s fully recognized around the world as “progress.” But, its unrelenting disregard for the health of ecosystems and for workers’ rights makes it a serial killer.

The wonderful world of nature is not part of the neoliberal capitalistic formula for success. In fact, nature with its life-sourcing ecosystems is treated like an adversary or like one more prop to use and abuse on the way to infinite progress. Really?

The Report alerts to the dangers of a “business as usual world,” an epithet that is also found throughout climate change literature. These warnings of impending loss of ecosystems, and by extension survival of Homo sapiens, depict a biosphere on a hot seat never before seen throughout human history. In fact, there is no time in recorded history that compares to the dangers immediately ahead. The most common watchword used by scientists is “unprecedented.” The change happens so rapidly, so powerfully. It’s unprecedented.

Meanwhile, people are shielded from the complexities, and heartaches, of collapsing ecosystems in today’s world by the artificiality of living a life of steel, glass, wood, cement, as the surrounding world collapses in a virtual sea of untested chemicals.

In the end, humans are the last vertebrates on the planet to directly feel and experience the impact of climate change and ecosystems collapsing. All of the other vertebrates are first in line. Maybe that’s for the best.

Still, how many more 68% plunges in wild vertebrate populations can civilized society handle and remain sane and well fed?

Robert Hunziker, MA, economic history DePaul University, awarded membership in Pi Gamma Mu International Academic Honor Society in Social Sciences is a freelance writer and environmental journalist who has over 200 articles published, including several translated into foreign languages, appearing in over 50 journals, magazines, and sites worldwide. He has been interviewed on numerous FM radio programs, as well as television.

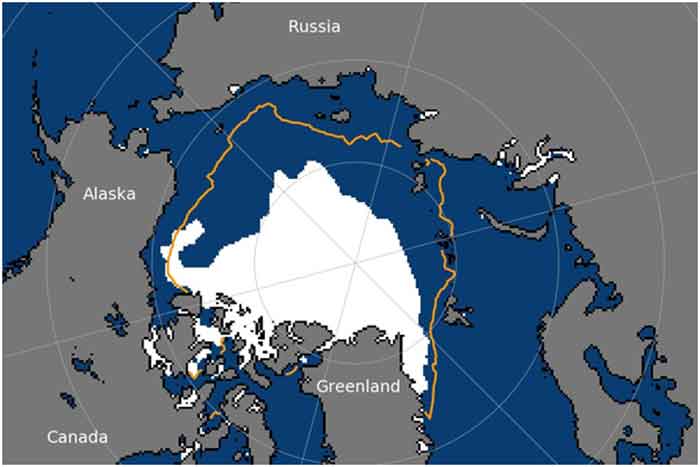

Arctic sea ice reached a minimum extent of 3.74 million square kilometers on September 15, likely the annual low, and the second lowest minimum on record. The orange line represents average extent of sea ice from 1981 to 2010 on that day. (NSIDC)

Arctic sea ice extent fell to the second-lowest annual minimum on record last week, a status that followed a summer of extreme heat in Siberia and accelerated melt even after summer’s end, the National Snow and Ice Data Center announced on Monday.

A report by Yereth Rosen said (Arctic Today, September 21, 2020):

Arctic sea ice extent bottomed out at 3.74 million square kilometers (1.44 million square miles) on September 15. It was only the second time in the satellite record that the minimum was below 4 million square kilometers; the record-low sea ice minimum was measured in 2012, when mid-September ice extent fell to 3.39 million square kilometers (1.13 million square miles).

Breaking that 4 million-square-kilometer threshold is likely to get attention, said Mark Serreze, director of the Colorado-based NSIDC.

“It’s only a number, but it’s only the second time it’s happened,” he said.

This year’s minimum was 2.51 million square kilometers (969,000 square miles) lower than the average annual minimums calculated from 1981 to 2010, the Colorado-based NSIDC said.

Extent is defined as the area of the ocean where there is at least 15 percent ice cover.

The 2020 ice retreat was part of a well-defined pattern. The 14 lowest minimums for sea ice extent have occurred in the last 14 years, according to NSIDC information.

“That is rather telling,” Serreze said. “The story is, we are in this new age.”

The “strong downward trend” in Arctic sea ice, despite some year-to-year variation, will ultimately result in an Arctic with no more summer ice, he said. That is expected to happen sometime in the next 10 to 20 years, he said.

Among the year-to-year variations is the changing location of extreme annual melt. Siberia turned out to be the hotspot this year, Serreze said; in other years different parts of the Arctic have the most extreme melt.

The Siberian heatwave, with temperatures hitting the first-recorded 100-degree Fahrenheit mark and massive Arctic wildfires burning, was part of a feedback cycle. Itself a product of Arctic climate change, according to scientists, it also contributed to Arctic climate change.

To some extent, this year’s extreme melt off Siberia was set up by winter conditions there, which made the ice there thin, Serreze said. “Once the melt started going, it had those self-perpetuating tendencies,” he said.

Those winter conditions were set up in part by a persistent positive Arctic Oscillation pattern that pushed ice from the Siberian coast, Serreze said.

The Arctic Oscillation is in a positive phase when there is lower-than-average air pressure over the Arctic. Recent research by an international team of scientists links a positive Arctic Oscillation to late-winter heat in Siberia — and increased risk of Siberian wildfires.

The Siberian Arctic was not the only place where ice melt was extreme.

In the Chukchi Sea, where early summer ice extent was not unusually low by recent years’ standards, melt was dramatic in late summer. That resulted in the earliest ice-free state in the Chukchi in the satellite record.

Retreat in the Chukchi was pushed along by a late-July storm that chewed up whatever freeze remained at the time, said Rick Thoman of the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy. “I don’t think we would have been that precipitous decline without the end-of-July storm,” he said.

Having so much open water there will again make it more difficult for the winter freeze to set in, Thoman said, though sea-surface temperatures are not as warm as they had been in the past. “It’s going to be a late freeze up in the Chukchi,” he said. “If the weather was to cooperate, it might not be super-late.”

That large amount of open water is also expected to continue a pattern of increasingly warm autumns off Alaska, he said.

The declaration of a minimum is preliminary, the NSIDC said. A shift in wind patterns or some sort of late melt could reduce the total ice extent again, the center said.

A green Arctic

Earth’s northern landscapes are greening.

Using satellite images to track global tundra ecosystems over decades, a new study found the Arctic region has become greener, as warmer air and soil temperatures lead to increased plant growth.

“The Arctic tundra is one of the coldest biomes on Earth, and it’s also one of the most rapidly warming,” said Logan Berner, a global change ecologist with Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, who led the recent research. “This Arctic greening we see is really a bellwether of global climatic change – it’s a biome-scale response to rising air temperatures.”

The study (Logan T. Berner, Richard Massey, Patrick Jantz, Bruce C. Forbes, Marc Macias-Fauria, Isla Myers-Smith, Timo Kumpula, Gilles Gauthier, Laia Andreu-Hayles, Benjamin V. Gaglioti, Patrick Burns, Pentti Zetterberg, Rosanne D’Arrigo, Scott J. Goetz, Summer warming explains widespread but not uniform greening in the Arctic tundra biome, Nature Communications, 2020; 11 (1) DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-18479-5), published this week in Nature Communications, is the first to measure vegetation changes spanning the entire Arctic tundra, from Alaska and Canada to Siberia, using satellite data from Landsat, a joint mission of NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Other studies have used the satellite data to look at smaller regions, since Landsat data can be used to determine how much actively growing vegetation is on the ground. Greening can represent plants growing more, becoming denser, and/or shrubs encroaching on typical tundra grasses and moss.

When the tundra vegetation changes, it impacts not only the wildlife that depend on certain plants, but also the people who live in the region and depend on local ecosystems for food. While active plants will absorb more carbon from the atmosphere, the warming temperatures could also be thawing permafrost, thereby releasing greenhouse gasses. The research is part of NASA’s Arctic Boreal Vulnerability Experiment (ABoVE), which aims to better understand how ecosystems are responding in these warming environments and the broader social implications.

Berner and his colleagues used the Landsat data and additional calculations to estimate the peak greenness for a given year for each of 50,000 randomly selected sites across the tundra. Between 1985 and 2016, about 38% of the tundra sites across Alaska, Canada, and western Eurasia showed greening. Only 3% showed the opposite browning effect, which would mean fewer actively growing plants. To include eastern Eurasian sites, they compared data starting in 2000, when Landsat satellites began regularly collecting images of that region. With this global view, 22% of sites greened between 2000 and 2016, while 4% browned.

“Whether it’s since 1985 or 2000, we see this greening of the Arctic evident in the Landsat record,” Berner said. “And we see this biome-scale greening at the same time and over the same period as we see really rapid increases in summer air temperatures.”

The scientists compared these greening patterns with other factors, and found that it’s also associated with higher soil temperatures and higher soil moisture. They confirmed these findings with plant growth measurements from field sites around the Arctic.

“Landsat is key for these kinds of measurements because it gathers data on a much finer scale than what was previously used,” said Scott Goetz, a professor at Northern Arizona University who also worked on the study and leads the ABoVE Science Team. This allows the researchers to investigate what is driving the changes to the tundra. “There’s a lot of microscale variability in the Arctic, so it’s important to work at finer resolution while also having a long data record,” Goetz said. “That’s why Landsat is so valuable.”

The study report said:

Arctic warming can influence tundra ecosystem function with consequences for climate feedbacks, wildlife and human communities. Yet ecological change across the Arctic tundra biome remains poorly quantified due to field measurement limitations and reliance on coarse-resolution satellite data. Here, we assess decadal changes in Arctic tundra greenness using time series from the 30 m resolution Landsat satellites. From 1985 to 2016 tundra greenness increased (greening) at ~37.3% of sampling sites and decreased (browning) at ~4.7% of sampling sites. Greening occurred most often at warm sampling sites with increased summer air temperature, soil temperature, and soil moisture, while browning occurred most often at cold sampling sites that cooled and dried. Tundra greenness was positively correlated with graminoid, shrub, and ecosystem productivity measured at field sites. Our results support the hypothesis that summer warming stimulated plant productivity across much, but not all, of the Arctic tundra biome during recent decades.

The scientists specifically asked:

- To what extent did tundra greenness change during recent decades in the Arctic?

- How closely did inter-annual variation in tundra greenness track summer temperatures?

- Were tundra greenness trends linked with climate, permafrost, topography, and/or fire?

- How closely did satellite observations of tundra greenness relate to temporal and spatial variation in plant productivity measured at field sites?

The report said:

Our analysis showed strong increases in average tundra greenness and summer air temperatures during the past three decades in the Arctic and constituent Arctic zones.

The scientists found widespread greening in recent decades that was linked with increasing summer air temperatures, annual soil temperatures, and summer soil moisture; however, tundra greenness had no significant trend in many areas and even declined in others.

The study and prior regional Landsat assessments show pronounced greening in northern Quebec.

Their analysis also indicated recent browning along the rugged southwestern coast of Greenland that is consistent with local declines in shrub growth.

The study report said:

Overall, satellites images show extensive greening and modest browning in the Arctic tundra biome during recent decades; however, regional discrepancies in greening and browning highlight the need for rigorous comparisons among satellites and between satellite and field measurements.

The report said:

We found no trend in tundra greenness at most locations, despite pervasive increases in summer air temperatures. It is possible that indirect drivers of vegetation change, such as permafrost thaw and nutrient release, are accumulating in response to warming of summer air temperatures, or that plants are limited by other environmental constrains. Low soil temperatures, nutrients, and moisture can limit plant response to rising air temperatures, as can strong genetic adaptation to prevailing environmental conditions. In other cases, warming might have stimulated plant growth, but led to no change in tundra greenness due to grazing, browsing, and trampling by herbivores. Field and modeling studies show that herbivory can significantly suppress tundra response to warming, although effects of vertebrate and invertebrate herbivores on Arctic greening and browning remain unclear. Last, tundra greenness could, in some areas, be confounded by patchy vegetation being interspersed with bare ground, surface water, or snow.

It said:

“Our results indicate Arctic plants did not universally benefit from warming in recent decades, highlighting diverse plant community responses to warming likely mediated by a combination of biotic and abiotic factors.”

“Our analysis showed that tundra browning occurred at a small percentage (~5%) of sampling sites during recent decades, and although uncommon, it was widely distributed in the Arctic.”

“Our analysis suggests that warming tended to promote rather than suppress plant productivity and biomass in the Arctic during recent decades, but increasing frequency of permafrost degradation, extreme weather events, pest outbreaks, and industrial development could contribute to future browning.”

“Tundra fires are another contributor to greening and browning in the Arctic; however, our results indicate that their contribution is currently quite small at a pan-Arctic extent due to their infrequent occurrence.”

“We found that 1.1% of sampling sites burned over the 16 years period, which suggests a current fire rotation of ~1450 years for the Arctic tundra biome. Regional fire rotation within the biome is strongly governed by summer climate and is considerably shorter (~425 years) in the warmest and driest tundra regions (e.g., Noatak and Seward, Alaska).”

“Our analysis further showed that fires recently occurred at ~1.0% of sampling sites that greened and ~2.4% of sampling sites that browned. Tundra fires can emit large amounts of carbon into the atmosphere and lead to temporary browning by burning off green plants, while subsequent increases in soil temperature and permafrost active layer depth can stimulate a long-term increase in plant growth and shrub dominance in some but not all cases. Continued warming will likely increase annual area burned in the tundra biome; thus, fires could become a more important driver of tundra greening and browning in the Arctic over the twenty-first century.”

“Our analysis contributes to a growing body of evidence showing recent widespread changes in the Arctic environment that can impact climate feedbacks. Rising temperatures are likely stimulating carbon uptake and storage by plants in areas that are greening (negative climate feedback), but also leading to soil carbon loss by thawing permafrost and enhancing microbial decomposition (positive climate feedback). Moreover, greening can reduce surface albedo as plants grow taller and leafier (positive climate feedback) while also affecting soil carbon release from permafrost thaw by altering canopy shading and snow-trapping (mixed climate feedbacks). The net climate feedback of these processes is currently uncertain; thus, our findings underscore the importance of future assessments with Earth system models that couple simulations of permafrost, vegetation, and atmospheric dynamics at moderately high spatial resolution.”

“Widespread tundra greening can also affect habitat suitability for wildlife and semi-domesticated reindeer, with consequences for northern subsistence and pastoral communities. As an example, moose and beavers recently colonized, or recolonized, increasingly shrubby riparian habitats in tundra ecosystems of northern Alaska and thus appear to be benefiting from recent tundra greening. Conversely, caribou populations in the North American Arctic could be adversely affected if warming stimulates vascular plant growth at the expense of lichens, an important winter forage. In the western Eurasian Arctic, indigenous herders (e.g., Sami, Nenets) manage about two million semi-domesticated reindeer on tundra rangelands. Shrub growth, height, and biomass significantly increased on these rangelands in recent decades, while lichen cover and biomass declined mostly due to trampling during the snow-free period.”

“Our analysis showed tundra greening in regions with potential moose, beaver, caribou, and reindeer habitat and demonstrated that variability in tundra greenness was often associated with annual shrub growth in these regions. Many northern communities rely on subsistence hunting or herding and thus changes in wildlife or herd populations can influence food security and dietary exposure to environmental contaminants. By documenting the extent of recent greening, analyses such as ours can help identify where wildlife and northern communities might be most impacted by ongoing changes in vegetation.”

“In summary, we assessed pan-Arctic changes in tundra greenness, and found evidence to support the hypothesis that recent summer warming contributed to increasing plant productivity and biomass across substantial portions of the Arctic tundra biome during the past three decades.”

“We also document summer warming in many areas that did not become greener. The lack of greening in these areas points towards lags in vegetation response and/or to the importance of other factors in mediating ecosystem response to warming. Sustained warming may not drive persistent greening in the Arctic over the twenty-first century for several reasons, particularly hydrological changes associated with permafrost thaw, drought, and fire. Overall, our high spatial resolution pan-Arctic assessment highlights tundra greening as a bellwether of global climatic change that has wide-ranging consequences for life in northern high-latitude ecosystems and beyond.”

September 22. Central Criminal Court, London: Today, the prosecutors in the Julian Assange case did their show trial predecessors from other legal traditions proud. The ghosts of such figures as Soviet state prosecutor Andrey Vyshinsky, would have approved of the line of questioning taken by James Lewis QC: suggest that Assange, accused of 17 counts of violating the US Espionage Act and one count of conspiracy to commit a computer crime, reads medical literature to exaggerate his condition.

Additionally to the political hook the defence is hanging its case on – political offences being a bar to extradition in the United Kingdom’s 2003 Extradition Act) – a medical one has been fashioned. Section 91 makes it clear that the judge in the extradition hearing must order the discharge of a person or adjourn the extradition hearing if “the physical or mental condition of the person is such that it would be unjust or oppressive to extradite him.” This can be read alongside the application of the European Convention of Human Rights, which stipulates under Article 3 that, “No one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”

Dr. Michael Kopelman, Emeritus Professor of Neuropsychiatry at the Institute of Psychiatry at King’s College London, took the stand at the Old Bailey to delve into Assange’s medical condition. His visits to Assange had yielded a man deprived of sleep, suffering “loss of weight, a sense of pre-occupation and helplessness as a result of threats to his life, the concealment of a razor blade as a means to self-harm and obsessive ruminations of ways of killing himself.” Kopelman was, he stated in submissions to the court, “as certain as a psychiatrist ever can be that, in the event of imminent extradition, Mr Assange would indeed find a way to commit suicide.”

The cross-examination by Lewis was in the worst traditions of the law. Non sequiturs were aplenty; baseless assessments on expertise generously made. Kopelman was, claimed the prosecutor, an expert in brain disease and its link with mental health, making him ill-suited to comment on Assange’s health. Kopelman, rather put out at this, reminded Lewis that he had previously called upon his services in a difference case. It was “a bit rich” for the prosecutor to now be challenging his qualifications. The prosecution also suggested that Kopelman’s psychiatric credentials were somehow shaded, if not rendered inconsequential, by him being “more of an advocate”. The defence witness snapped, suggesting he would respond to that assertion with an “unparliamentary word”.

The prosecution focused on Kopelman’s summaries of days in April and May 2019, when Assange was evaluated by psychiatrists. This gave Lewis a chance to accuse the witness of omissions unsuitable to the defence. Kopelman had to constantly remind Lewis that he only started to attend such sessions in person at the end of May.

In another feeble sortie, the prosecution suggested that Assange was medically sound because his performance at the extradition trial over the previous days had indicated no signs of depression. He was attentive to proceedings; he could answer the judge. To even the most untrained and untutored in the field of mental health, this should be regarded as an amateurish presumption: a competent performance hardly suggests the absence of depression or cognitive disturbance.

Kopelman duly made that point, referring to the transcripts Lewis had used. “I cannot evaluate his mental and cognitive state from what’s in here.” Assange had “made a few comments”; he had “some long-standing semantic knowledge”; he “replied appropriately”. None of this need suggest that his “cognitive state is normal.” If anything, they lent credibility to a diagnosis of Asperger’s syndrome.

In Kopelman’s testimony, Assange is reported to have experienced “auditory hallucinations” featuring “derogatory and persecutory” voices: “you are dust, you are dead, we are coming to get you”. In assertions that were verging on the preposterous, even by the standards of this prosecution, Lewis attempted to erect an edifice of illusion. Assange was taking everyone for a joy ride in a fantasy of mental ill-health that had no foundation. He had been surely “malingering” about his symptoms. His hallucinations had been “self-reported”. Kopelman reminded Lewis of an elementary lesson: psychiatry tended to rely on self-reporting. “I don’t believe he’s got delusions. He’s very worried about whether discussions are recorded.” Given the “experiences in the embassy, that was a rational anxiety.”

Another sally followed, this time using Assange’s family as crude props for psychobabble. In the course of the extradition proceedings, it had become clear that Assange had formed a relationship with Stella Morris, having had two children with her during his stay at the Ecuadorean embassy in London. Two reports prepared by Kopelman included quotes from a visit with Morris. The failure to mention Morris in his first report peeved Lewis. Kopelman’s explanation: “This was not in the public domain at that point, and she was very concerned about privacy so we decided not to put it in.” Once knowledge of her existence became public, “I included it.”

Lewis would have none of it: the duty to the court overrode any matters of embarrassment to Assange, and sensitivity to Morris’ privacy was of no consequence. Knowledge to the court of Morris and the children’s existence was vital, suggested Lewis, as it might be a “protective factor against suicide.” Charmingly, Lewis seemed to ignore the point that having a young family would hardly be a deterrent against self-harm when facing a promise of being locked up for life in solitary confinement in another country notorious for its lugubrious prison conditions. Death could well prove a desperate consolation. Kopelman was on to this: married people do not resist the pathway to suicide.

The psychiatric picture of Assange drawn by Kopelman was one of regression and severity, made worse by the likelihood of harm that can arise to those with Asperger’s syndrome. He had an “intense suicidal preoccupation.” Findings from autism specialist Dr Simon Baron-Cohen – that suicide is nine times more likely in patients with Asperger’s “than in the general population in England” – were mentioned. That study also found that people with Asperger’s syndrome “were significantly more likely to report suicidal ideation or plans or attempts at suicide if they also had depression.” Assange, Kopelman reasoned, faced “an abundance of known risk factors”.

In December 2019, conditions proved acute; in February and March, moderately severe. The lockdown at the Belmarsh prison facility precipitated by the coronavirus pandemic did its share of harm. Assange had sought confession with a Catholic priest, “who granted him absolution”. He had drawn up a will, scribbled farewell letters to family and friends. All signs of a man possibly readying for the other side.

As appalling as his conditions in Belmarsh had been, including a stint in confined isolation, the conditions “he would experience in North America would be far worse than anything experienced in the embassy or Belmarsh.” The imminence of extradition would “trigger a suicide attempt.” Assange’s most probable pre-trial accommodation would also encourage this. It was at the Alexandria Detention Center where Chelsea Manning attempted suicide while being held refusing to relent to a grand jury subpoena to answer questions on WikiLeaks. According to Kopelman, “It just shows how awful conditions must be.”

Attention turned to the prevalence of depression during Assange’s time in the Ecuadorean embassy, starting around 2015. This had caught the attention of Nils Melzer, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture. Melzer has taken the long view on Assange: that the combined effort of several states – Ecuador, the United Kingdom, United States, Sweden – had created conditions of “psychological torture”, part of a deliberate, progressively cruel effort. There had been, he claimed in May 2019, “a relentless and unrestrained campaign of public mobbing, intimidation and defamation against Mr Assange, not only in the United States, but also in the United Kingdom, Sweden, and more recently, Ecuador.”

In company with two medical experts experienced in examining potential victims of torture and ill-treatment, Melzer’s May 9, 2019 visit to Assange confirmed that his “health has been seriously affected by the extreme hostile and arbitrary environment he has been exposed to for many years.” Assange, “in addition to physical ailments … showed all symptoms typical for prolonged exposure to psychological torture, including extreme stress, chronic anxiety and intense psychological trauma.”

In November 2019, Melzer reiterated his concerns in the face of tardiness on the part of the British authorities. “Despite the medical urgency of my [May] appeal, and the seriousness of the alleged violations, the UK has not undertaken any measures of investigation, prevention and redress required under international law.”

Melzer’s views did not impress Lewis. His labours on the Assange case were “palpable nonsense”, lacking in balance and accuracy. Kopelman was asked to distance himself from such conclusions, despite them not being an “important factor” in his work. Lewis remains comfortably deaf, not merely to Melzer’s work, but the findings of such eminent groups as Doctors for Assange, an initial collective of 60 medical doctors, growing to 117 spanning 18 countries. The Assange case, they argued in February in The Lancet, “highlights several concerning aspects that warrant the medical profession’s close attention and concerted action”. In June, the group noted that, “Isolation and under-stimulation are key psychological torture tactics, capable of inducing severe despair, disorientation, destabilisation, and disintegration of crucial mental functions.” The psychological torture of a publisher and journalist in a climate already hostile to journalism “sets a precedent of international concern.”

In a crude, somewhat farcical manoeuvre typical of the day’s proceedings, Lewis went just that bit lower in wondering whether Assange’s depression would have made a difference in soliciting or leaking “material from the US government.” Would such a tormented mind have been able to meet his media commitments (“doing a chat show” for Russia Today), or conduct public speaking engagements? Such views of depression, that great tormenter and killer, do not merely show this prosecution to be venal; they show it to be profoundly ignorant of history and medicine.

Assange’s defence team have a bright precedent to rely on. British computer scientist Lauri Love, who was also diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome, was arrested in 2015 in the UK at the request of the United States for allegedly hacking various government entities. These included the Federal Reserve, the Environmental Protection Agency, NASA and the US Army. Initially losing his case to avoid extradition on September 16, 2016, and facing the approval to do so by then Secretary of State Amber Rudd, Love successfully appealed to the High Court. It was accepted that the US was an inappropriate forum to try Love; and that prison conditions awaiting him “would be oppressive by reason of his physical and mental condition.”

The High Court also accepted that “the fact of extradition would bring on severe depression, and that Mr Love would probably be determined to commit suicide, here or in America.” Being put on suicide watch would hardly have been adequate – it did not constitute a “form of treatment; there was no evidence that treatment would or could be made available on suicide watch for the very conditions which suicide watch itself exacerbates.”

This was strikingly appropriate and relevant. Kopelman, who also testified in Love’s case, had also been given reassurances at the time that the US prison system was up to scratch in guarding against suicide. Since then, the US prison system had been marked by the prominent suicide of Jeffrey Epstein and the attempted suicide by Manning. “Those reassurances were not very reassuring.”

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: bkampmark@gmail.com

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER

Julian Assange is not on trial simply for his liberty and his life. He is fighting for the right of every journalist to do hard-hitting investigative journalism without fear of arrest and extradition to the United States. Assange faces 175 years in a US super-max prison on the basis of claims by Donald Trump’s administration that his exposure of US war crimes in Iraq and Afghanistan amounts to “espionage”.

The charges against Assange rewrite the meaning of “espionage” in unmistakably dangerous ways. Publishing evidence of state crimes, as Assange’s Wikileaks organisation has done, is covered by both free speech and public interest defences. Publishing evidence furnished by whistleblowers is at the heart of any journalism that aspires to hold power to account and in check. Whistleblowers typically emerge in reaction to parts of the executive turning rogue, when the state itself starts breaking its own laws. That is why journalism is protected in the US by the First Amendment. Jettison that and one can no longer claim to live in a free society.

Aware that journalists might understand this threat and rally in solidarity with Assange, US officials initially pretended that they were not seeking to prosecute the Wikileaks founder for journalism – in fact, they denied he was a journalist. That was why they preferred to charge him under the arcane, highly repressive Espionage Act of 1917. The goal was to isolate Assange and persuade other journalists that they would not share his fate.

Assange explained this US strategy way back in 2011, in a fascinating interview he gave to Australian journalist Mark Davis. (The relevant section occurs from minute 24 to 43.) This was when the Obama administration first began seeking a way to distinguish Assange from liberal media organisations, such as the New York Times and Guardian that had been working with him, so that only he would be charged with espionage.

Assange warned then that the New York Times and its editor Bill Keller had already set a terrible precedent on legitimising the administration’s redefinition of espionage by assuring the Justice Department – falsely, as it happens – that they had been simply passive recipients of Wikileaks’ documents. Assange noted (40.00 mins):

“If I am a conspirator to commit espionage, then all these other media organisations and the principal journalists in them are also conspirators to commit espionage. What needs to be done is to have a united face in this.”

During the course of the current extradition hearings, US officials have found it much harder to make plausible this distinction principle than they may have assumed.

Journalism is an activity, and anyone who regularly engages in that activity qualifies as a journalist. It is not the same as being a doctor or a lawyer, where you need a specific professional qualification to practice. You are a journalist if you do journalism – and you are an investigative journalist if, like Assange, you publish information the powerful want concealed. Which is why in the current extradition hearings at the Old Bailey in London, the arguments made by lawyers for the US that Assange is not a journalist but rather someone engaged in espionage are coming unstuck.

My dictionary defines “espionage” as “the practice of spying or of using spies, typically by governments to obtain political and military information”. A spy is defined as someone who “secretly obtains information on an enemy or competitor”.

Very obviously the work of Wikileaks, a transparency organisation, is not secret. By publishing the Afghan and Iraq war diaries, Wikileaks exposed crimes the United States wished to keep secret.

Assange did not help a rival state to gain an advantage, he helped all of us become better informed about the crimes our own states commit in our names. He is on trial not because he traded in secrets, but because he blew up the business of secrets – the very kind of secrets that have enabled the west to pursue permanent, resource-grabbing wars and are pushing our species to the verge of extinction.

In other words, Assange was doing exactly what journalists claim to do every day in a democracy: monitor power for the public good. Which is why ultimately the Obama administration abandoned the idea of issuing an indictment against Assange. There was simply no way to charge him without also putting journalists at the New York Times, the Washington Post and the Guardian on trial too. And doing that would have made explicit that the press is not free but works on licence from those in power.

Media indifference

For that reason alone, one might have imagined that the entire media – from rightwing to liberal-left outlets – would be up in arms about Assange’s current predicament. After all, the practice of journalism as we have known it for at least 100 years is at stake.

But in fact, as Assange feared nine years ago, the media have chosen not to adopt a “united face” – or at least, not a united face with Wikileaks. They have remained all but silent. They have ignored – apart from occasionally to ridicule – Assange’s terrifying ordeal, even though he has been locked up for many months in Belmarsh high-security prison awaiting efforts to extradite him as a spy. Assange’s very visible and prolonged physical and mental abuse – both in Belmarsh and, before that, in the Ecuadorian embassy, where he was given political asylum – have already served part of their purpose: to deter young journalists from contemplating following in his footsteps.

Even more astounding is the fact that the media have taken no more than a cursory interest in the events of the extradition hearing itself. What reporting there has been has given no sense of the gravity of the proceedings or the threat they pose to the public’s right to know what crimes are being committed in their name. Instead, serious, detailed coverage has been restricted to a handful of independent outlets and bloggers.

Most troubling of all, the media have not reported the fact that during the hearing lawyers for the US have abandoned the implausible premise of their main argument that Assange’s work did not constitute journalism. Now they appear to accept that Assange did indeed do journalism, and that other journalists could suffer his fate. What was once implicit has become explicit, as Assange warned: any journalist who exposes serious state crimes now risks the threat of being locked away for the rest of their lives under the draconian Espionage Act.

This glaring indifference to the case and its outcome is extremely revealing about what we usually refer to as the “mainstream” media. In truth, there is nothing mainstream or popular about this kind of media. It is in reality a media elite, a corporate media, owned by and answerable to billionaire owners – or in the case of the BBC, ultimately to the state – whose interests it really serves.

The corporate media’s indifference to Assange’s trial hints at the fact that it is actually doing very little of the sort of journalism that threatens corporate and state interests and that challenges real power. It won’t suffer Assange’s fate because, as we shall see, it doesn’t attempt to do the kind of journalism Assange and his Wikileaks organisation specialise in.

The indifference suggests rather starkly that the primary role of the corporate media – aside from its roles in selling us advertising and keeping us pacified through entertainment and consumerism – is to serve as an arena in which rival centres of power within the establishment fight for their narrow interests, settling scores with each other, reinforcing narratives that benefit them, and spreading disinformation against their competitors. On this battlefield, the public are mostly spectators, with our interests only marginally affected by the outcome.

Gauntlet thrown down

The corporate media in the US and UK is no more diverse and pluralistic than the major corporate-funded political parties they identify with. This kind of media mirrors the same flaws as the Republican and Democratic parties in the US: they cheerlead consumption-based, globalised capitalism; they favour a policy of unsustainable, infinite growth on a finite planet; and they invariably support colonial, profit-driven, resource-grabbing wars, nowadays often dressed up as humanitarian intervention. The corporate media and the corporate political parties serve the interests of the same power establishment because they are equally embedded in that establishment.

(In this context, it was revealing that when Assange’s lawyers argued earlier this year that he could not be extradited to the US because extradition for political work is barred under its treaty with the UK, the US insisted that Assange be denied this defence. They argued that “political” referred narrowly to “party political” – that is, politics that served the interests of a recognised party.)

From the outset, the work of Assange and Wikileaks threatened to disrupt the cosy relationship between the media elite and the political elite. Assange threw down a gauntlet to journalists, especially those in the liberal parts of the media, who present themselves as fearless muckrakers and watchdogs on power.

Unlike the corporate media, Wikileaks doesn’t depend on access to those in power for its revelations, or on the subsidies of billionaires, or on income from corporate advertisers. Wikileaks receives secret documents direct from whistleblowers, giving the public an unvarnished, unmediated perspective on what the powerful are doing – and what they want us to think they are doing.

Wikileaks has allowed us to see raw, naked power before it puts on a suit and tie, slicks back its hair and conceals the knife.

But as much as this has been an empowering development for the general public, it is at best a very mixed blessing for the corporate media.

In early 2010, the fledgling Wikileaks organisation received its first tranche of documents from US army whistleblower Chelsea Manning: hundreds of thousands of classified files exposing US crimes in Iraq and Afghanistan. Assange and “liberal” elements of the corporate media were briefly and uncomfortably thrown into each others’ arms.

On the one hand, Assange needed the manpower and expertise provided by big-hitting newspapers like the New York Times, the Guardian and Der Spiegel to help Wikileaks sift through vast trove to find important, hidden disclosures. He also needed the mass audiences those papers could secure for the revelations, as well as those outlets’ ability to set the news agenda in other media.

Liberal media, on the other hand, needed to court Assange and Wikileaks to avoid being left behind in the media war for big, Pulitzer Prize-winning stories, for audience share and for revenues. Each worried that, were it not to do a deal with Wikileaks, a rival would publish those world-shattering exclusives instead and erode its market share.

Gatekeeper role under threat

For a brief while, this mutual dependency just about worked. But only for a short time. In truth, the liberal corporate media is far from committed to a model of unmediated, whole-truth journalism. The Wikileaks model undermined the corporate media’s relationship to the power establishment and threatened its access. It introduced a tension and division between the functions of the political elite and the media elite.

Those intimate and self-serving ties are illustrated in the most famous example of corporate media working with a “whistleblower”: the use of a source, known as Deep Throat, who exposed the crimes of President Richard Nixon to Washington Post reporters Woodward and Bernstein back in the early 1970s, in what became known as Watergate. That source, it emerged much later, was actually the associate director of the FBI, Mark Felt.

Far from being driven to bring down Nixon out of principle, Felt wished to settle a score with the administration after he was passed over for promotion. Later, and quite separately, Felt was convicted of authorising his own Watergate-style crimes on behalf of the FBI. In the period before it was known that Felt had been Deep Throat, President Ronald Reagan pardoned him for those crimes. It is perhaps not surprising that this less than glorious context is never mentioned in the self-congratulatory coverage of Watergate by the corporate media.

But worse than the potential rupture between the media elite and the political elite, the Wikileaks model implied an imminent redundancy for the corporate media. In publishing Wikileaks’ revelations, the corporate media feared it was being reduced to the role of a platform – one that could be discarded later – for the publication of truths sourced elsewhere.

The undeclared role of the corporate media, dependent on corporate owners and corporate advertising, is to serve as gatekeeper, deciding which truths should be revealed in the “public interest”, and which whistleblowers will be allowed to disseminate which secrets in their possession. The Wikileaks model threatened to expose that gatekeeping role, and make clearer that the criterion used by corporate media for publication was less “public interest” than “corporate interest”.

In other words, from the start the relationship between Assange and “liberal” elements of the corporate media was fraught with instability and antagonism.

The corporate media had two possible responses to the promised Wikileaks revolution.

One was to get behind it. But that was not straightforward. As we have noted, Wikileaks’ goal of transparency was fundamentally at odds both with the corporate media’s need for access to members of the power elite and with its embedded role, representing one side in the “competition” between rival power centres.

The corporate media’s other possible response was to get behind the political elite’s efforts to destroy Wikileaks. Once Wikileaks and Assange were disabled, there could be a return to media business as usual. Outlets would once again chase tidbits of information from the corridors of power, getting “exclusives” from the power centres they were allied with.

Put in simple terms, Fox News would continue to get self-serving exclusives against the Democratic party, and MSNBC would get self-serving exclusives against Trump and the Republican Party. That way, everyone would get a slice of editorial action and advertising revenue – and nothing significant would change. The power elite in its two flavours, Democrat and Republican, would continue to run the show unchallenged, switching chairs occasionally as elections required.

From dependency to hostility

Typifying the media’s fraught, early relationship with Assange and Wikileaks – sliding rapidly from initial dependency to outright hostility – was the Guardian. It was a major beneficiary of the Afghan and Iraq war diaries, but very quickly turned its guns on Assange. (Notably, the Guardian would also lead the attack in the UK on the former leader of the Labour party, Jeremy Corbyn, who was seen as threatening a “populist” political insurgency in parallel to Assange’s “populist” media insurgency.)

Despite being widely viewed as a bastion of liberal-left journalism, the Guardian has been actively complicit in rationalising Assange’s confinement and abuse over the past decade and in trivialising the threat posed to him and the future of real journalism by Washington’s long-term efforts to permanently lock him away.

There is not enough space on this page to highlight all the appalling examples of the Guardian’s ridiculing of Assange (a few illustrative tweets scattered through this post will have to suffice) and disparaging of renowned experts in international law who have tried to focus attention on his arbitrary detention and torture. But the compilation of headlines in the tweet below conveys an impression of the antipathy the Guardian has long harboured for Assange, most of it – such as James Ball’s article – now exposed as journalistic malpractice.

The Guardian’s failings have extended too to the current extradition hearings, which have stripped away years of media noise and character assassination to make plain why Assange has been deprived of his liberty for the past 10 years: because the US wants revenge on him for publishing evidence of its crimes and seeks to deter others from following in his footsteps.

In its pages, the Guardian has barely bothered to cover the case, running superficial, repackaged agency copy. This week it belatedly ran a solitary opinion piece from Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Brazil’s former leftwing president, to mark the fact that many dozens of former world leaders have called on the UK to halt the extradition proceedings. They appear to appreciate the gravity of the case much more clearly than the Guardian and most other corporate media outlets.

But among the Guardian’s own columnists, even its supposedly leftwing ones like Gorge Monbiot and Owen Jones, there has been blanket silence about the hearings. In familiar style, the only in-house commentary on the case so far is yet another snide hit-piece – this one in the fashion section written by Hadley Freeman. It simply ignores the terrifying developments for journalism taking place at the Old Bailey, close by the Guardian’s offices. Instead Freeman mocks the credible fears of Assange’s partner, Stella Moris, that, if Assange is extradited, his two young children may not be allowed contact with their father again.

Freeman’s goal, as has been typical of the Guardian’s modus operandi, is not to raise an issue of substance about what is happening to Assange but to score hollow points in a distracting culture war the paper has become so well-versed in monetising. In her piece, entitled “Ask Hadley: ‘Politicising’ and ‘weaponising’ are becoming rather convenient arguments”, Freeman exploits Assange and Moris’s suffering to advance her own convenient argument that the word “politicised” is much misused – especially, it seems, when criticising the Guardian for its treatment of Assange and Corbyn.

The paper could not make it any plainer. It dismisses the idea that it is a “political” act for the most militarised state on the planet to put on trial a journalist for publishing evidence of its systematic war crimes, with the aim of locking him up permanently.

Password divulged

The Guardian may be largely ignoring the hearings, but the Old Bailey is far from ignoring the Guardian. The paper’s name has been cited over and over again in court by lawyers for the US. They have regularly quoted from a 2011 book on Assange by two Guardian reporters, David Leigh and Luke Harding, to bolster the Trump administration’s increasingly frantic arguments for extraditing Assange.

When Leigh worked with Assange, back in 2010, he was the Guardian’s investigations editor and, it should be noted, the brother-in-law of the then-editor, Alan Rusbridger. Harding, meanwhile, is a long-time reporter whose main talent appears to be churning out Guardian books at high speed that closely track the main concerns of the UK and US security services. In the interests of full disclosure, I should note that I had underwhelming experiences dealing with both of them during my years working at the Guardian.

Normally a newspaper would not hesitate to put on its front page reports of the most momentous trial of recent times, and especially one on which the future of journalism depends. That imperative would be all the stronger were its own reporters’ testimony likely to be critical in determining the outcome of the trial. For the Guardian, detailed and prominent reporting of, and commentary on, the Assange extradition hearings should be a double priority.

So how to explain the Guardian’s silence?

The book by Leigh and Harding, WikiLeaks: Inside Julian Assange’s War on Secrecy, made a lot of money for the Guardian and its authors by hurriedly cashing in on the early notoriety around Assange and Wikileaks. But the problem today is that the Guardian has precisely no interest in drawing attention to the book outside the confines of a repressive courtroom. Indeed, were the book to be subjected to any serious scrutiny, it might now look like an embarrassing, journalistic fraud.

The two authors used the book not only to vent their personal animosity towards Assange – in part because he refused to let them write his official biography – but also to divulge a complex password entrusted to Leigh by Assange that provided access to an online cache of encrypted documents. That egregious mistake by the Guardian opened the door for every security service in the world to break into the file, as well as other files once they could crack Assange’s sophisticated formula for devising passwords.

Much of the furore about Assange’s supposed failure to protect names in the leaked documents published by Assange – now at the heart of the extradition case – stems from Leigh’s much-obscured role in sabotaging Wikileaks’ work. Assange was forced into a damage limitation operation because of Leigh’s incompetence, forcing him to hurriedly publish files so that anyone worried they had been named in the documents could know before hostile security services identified them.

This week at the Assange hearings, Professor Christian Grothoff, a computer expert at Bern University, noted that Leigh had recounted in his 2011 book how he pressured a reluctant Assange into giving him the password. In his testimony, Grothoff referred to Leigh as a “bad faith actor”.

‘Not a reliable source’

Nearly a decade ago Leigh and Harding could not have imagined what would be at stake all these years later – for Assange and for other journalists – because of an accusation in their book that the Wikileaks founder recklessly failed to redact names before publishing the Afghan and Iraq war diaries.

The basis of the accusation rests on Leigh’s highly contentious recollection of a discussion with three other journalists and Assange at a restaurant near the Guardian’s former offices in July 2010, shortly before publication of the Afghan revelations.

According to Leigh, during a conversation about the risks of publication to those who had worked with the US, Assange said: “They’re informants, they deserve to die.” Lawyers for the US have repeatedly cited this line as proof that Assange was indifferent to the fate of those identified in the documents and so did not expend care in redacting names. (Let us note, as an aside, that the US has failed to show that anyone was actually put in harm’s way from publication, and in the Manning trial a US official admitted that no one had been harmed.)

The problem is that Leigh’s recollection of the dinner has not been confirmed by anyone else, and is hotly disputed by another participant, John Goetz of Der Spiegel. He has sworn an affidavit saying Leigh is wrong. He gave testimony at the Old Bailey for the defence last week. Extraordinarily the judge, Vanessa Baraitser, refused to allow him to contest Leigh’s claim, even though lawyers for the US have repeatedly cited that claim.

Further, Goetz, as well as Nicky Hager, an investigative journalist from New Zealand, and Professor John Sloboda, of Iraq Body Count, all of whom worked with Wikileaks to redact names at different times, have testified that Assange was meticulous about the redaction process. Goetz admitted that he had been personally exasperated by the delays imposed by Assange to carry out redactions:

“At that time, I remember being very, very irritated by the constant, unending reminders by Assange that we needed to be secure, that we needed to encrypt things, that we needed to use encrypted chats. … The amount of precautions around the safety of the material were enormous. I thought it was paranoid and crazy but it later became standard journalistic practice.”

Prof Sloboda noted that, as Goetz had implied in his testimony, the pressure to cut corners on redaction came not from Assange but from Wikileaks’ “media partners”, who were desperate to get on with publication. One of the most prominent of those partners, of course, was the Guardian. According to the account of proceedings at the Old Bailey by former UK ambassador Craig Murray:

“Goetz [of Der Spiegel] recalled an email from David Leigh of The Guardian stating that publication of some stories was delayed because of the amount of time WikiLeaks were devoting to the redaction process to get rid of the ‘bad stuff’.”

When confronted by US counsel with Leigh’s claim in the book about the restaurant conversation, Hager observed witheringly: “I would not regard that [Leigh and Harding’s book] as a reliable source.” Under oath, he ascribed Leigh’s account of the events of that time to “animosity”.

Scoop exposed as fabrication

Harding is hardly a dispassionate observer either. His most recent “scoop” on Assange, published in the Guardian two years ago, has been exposed as an entirely fabricated smear. It claimed that Assange secretly met a Trump aide, Paul Manafort, and unnamed “Russians” while he was confined to the Ecuadorian embassy in 2016.

Harding’s transparent aim in making this false claim was to revive a so-called “Russiagate” smear suggesting that, in the run-up to the 2016 US presidential election, Assange conspired with the Trump camp and Russian president Vladimir Putin to help get Trump elected. These allegations proved pivotal in alienating Democrats who might otherwise have rallied to Assange’s side, and have helped forge bipartisan support for Trump’s current efforts to extradite Assange and jail him.

The now forgotten context for these claims was Wikileaks’ publication shortly before the election of a stash of internal Democratic party emails. They exposed corruption, including efforts by Democratic officials to sabotage the party’s primaries to undermine Bernie Sanders, Hillary Clinton’s rival for the party’s presidential nomination.

Those closest to the release of the emails have maintained that they were leaked by a Democratic party insider. But the Democratic leadership had a pressing need to deflect attention from what the emails revealed. Instead they actively sought to warm up a Cold War-style narrative that the emails had been hacked by Russia to foil the US democratic process and get Trump into power.

No evidence was ever produced for this allegation. Harding, however, was one of the leading proponents of the Russiagate narrative, producing another of his famously fast turnaround books on the subject, Collusion. The complete absence of any supporting evidence for Harding’s claims was exposed in dramatic fashion when he was questioned by journalist Aaron Mate.

Harding’s 2018 story about Manafort was meant to add another layer of confusing mischief to an already tawdry smear campaign. But problematically for Harding, the Ecuadorian embassy at the time of Manafort’s supposed visit was probably the most heavily surveilled building in London. The CIA, as we would later learn, had even illegally installed cameras inside Assange’s quarters to spy on him. There was no way that Manafort and various “Russians” could have visited Assange without leaving a trail of video evidence. And yet none exists. Rather than retract the story, the Guardian has gone to ground, simply refusing to engage with critics.

Most likely, either Harding or a source were fed the story by a security service in a further bid to damage Assange. Harding made not even the most cursory checks to ensure that his “exclusive” was true.

Unwilling to speak in court

Despite both Leigh and Harding’s dismal track record in their dealings with Assange, one might imagine that at this critical point – as Assange faces extradition and jail for doing journalism – the pair would want to have their voices heard directly in court rather than allow lawyers to speak for them or allow other journalists to suggest unchallenged that they are “unreliable” or “bad faith” actors.

Leigh could testify at the Old Bailey that he stands by his claims that Assange was indifferent to the dangers posed to informants; or he could concede that his recollection of events may have been mistaken; or clarify that, whatever Assange said at the infamous dinner, he did in fact work scrupulously to redact names – as other witnesses have testified.

Given the grave stakes, for Assange and for journalism, that would be the only honourable thing for Leigh to do: to give his testimony and submit to cross-examination. Instead he shelters behind the US counsel’s interpretation of his words and Judge Baraitser’s refusal to allow anyone else to challenge it, as though Leigh brought his claim down from the mountain top.

The Guardian too, given it central role in the Assange saga, might have been expected to insist on appearing in court, or at the very least to be publishing editorials furiously defending Assange from the concerted legal assault on his rights and journalism’s future. The Guardian’s “star” leftwing columnists, figures like George Monbiot and Owen Jones, might similarly be expected to be rallying readers’ concerns, both in the paper’s pages and on their own social media accounts. Instead they have barely raised their voices above a whisper, as though fearful for their jobs.

These failings are not about the behaviour of any single journalist. They reflect a culture at the Guardian, and by extension in the wider corporate media, that abhors the kind of journalism Assange promoted: a journalism that is open, genuinely truth-seeking, non-aligned and collaborative rather than competitive. The Guardian wants journalism as a closed club, one where journalists are once again treated as high priests by their flock of readers, who know only what the corporate media is willing to disclose to them.

Assange understood the problem back in 2011, as he explained in his interview with Mark Davis (38.00mins):

“There is a point I want to make about perceived moral institutions, such as the Guardian and New York Times. The Guardian has good people in it. It also has a coterie of people at the top who have other interests. … What drives a paper like the Guardian or New York Times is not their inner moral values. It is simply that they have a market. In the UK, there is a market called “educated liberals”. Educated liberals want to buy a newspaper like the Guardian and therefore an institution arises to fulfil that market. … What is in the newspaper is not a reflection of the values of the people in that institution, it is a reflection of the market demand.”

That market demand, in turn, is shaped not by moral values but by economic forces – forces that need a media elite, just as they do a political elite, to shore up an ideological worldview that keeps those elites in power. Assange threatened to bring that whole edifice crashing down. That is why the institutions of the Guardian and the New York Times will shed no more tears than Donald Trump and Joe Biden if Assange ends up spending the rest of his life behind bars.

This essay first appeared on Jonathan Cook’s blog: https://www.jonathan-cook.net/blog/

Jonathan Cook won the Martha Gellhorn Special Prize for Journalism. His books include “Israel and the Clash of Civilisations: Iraq, Iran and the Plan to Remake the Middle East” (Pluto Press) and “Disappearing Palestine: Israel’s Experiments in Human Despair” (Zed Books). His website is www.jonathan-cook.net.