15 February 23

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

WHAT’S IN IT FOR ME, WILL NOT GET IT DONE: Reader Supported News could absolutely, without a doubt be a game changing organization. If in fact news supported by the community it serves really got traction, the implications would be vast. We continue to be saddled with a community that wants to know what’s in it for them before they will consider tossing in a donation. What’s in it for you? Your country back.

Marc Ash • Founder, Reader Supported News

Sure, I'll make a donation!

Jane Ferguson | How Assad Blocked Aid to Syrian Earthquake Victims

Jane Ferguson, The New Yorker

Ferguson writes: "In the country’s rebel-held northwest, none of the assistance delivered so far has included rescue equipment."

In the country’s rebel-held northwest, none of the assistance delivered so far has included rescue equipment.

Two small boys lay in adjacent beds on the ground floor of the main public hospital in Afrin, a small, rebel-held city in northern Syria. The dimly lit room had the sombre silence of an intensive-care unit, punctuated by the soft beeping of heart monitors. A female nurse with a grave look on her face whispered that the mother and father of each child were dead. “They don’t know their parents are dead yet,” she said in broken English. “We tell them they have been taken to a different hospital.” The boy on the left was five years old and was unconscious, his tiny head appearing above the sheet that covered him, his body dwarfed by the hospital bed. His right hand had been broken, and his right foot was bandaged from surgery; both had been operated on. In the bed next to him, a fourteen-year-old boy, slight for his age, was still, with only his eyes moving as he watched me talk to a group of doctors and nurses. His left leg had been operated on as well. I smiled at him, and he stared blankly back. A medical tube was inserted in his nose and taped to his cheek.

Ibrahim Al Yousef, a nurse in pink scrubs, told me that he was pessimistic about the younger boy’s chance of survival. “Before they arrived here, they were in bad condition,” he said. “The rescue teams in the field went to great efforts to save them.” The older boy, he added, was recovering. “This kid is doing well, but the other one is not good,” he said, pausing. “God willing, we hope he will pass this critical condition.”

Both the boys are from Jindires, a small town about twelve miles away dotted with dilapidated cinder-block apartment buildings and small shops. Between rows of olive trees, tents had been erected for survivors of last week’s earthquake. The boys’ homes had collapsed, killing their parents and most of their siblings. Growing up in rebel-held Syria during the country’s brutal, twelve-year civil war, they lived in poverty, were largely cut off from the rest of the world, and faced little chance of anything resembling a stable life. Now the earthquake had turned their futures even grimmer.

Jindires and Afrin were among the worst hit in Syria by the earthquake. Buildings in rebel-controlled parts of the country collapsed on sleeping families just as they had across the border in Turkey, but, in Syria, virtually no one from the outside world came to help. The White Helmets, a volunteer rescue service that has been pulling civilians out of the rubble of homes bombed by Russian and Syrian government air strikes for years, did their best to rescue survivors. But they had none of the advanced rescue equipment brought to Turkey, where teams from around the world flew in with sniffer dogs, sensitive microphones, and seismic sensors. Syrians mostly dug with backhoes, shovels, and bare hands. People told us that there were some buildings, filled with families, from which no survivors had emerged.

They said that the Assad regime and its ally, Russia, are preventing international aid from entering rebel-held areas. Several border crossings with Turkey are within a half hour’s drive from Syria’s disaster zone. So far, though, Assad has only permitted U.N.-distributed aid through one of them, and none of the assistance has included earthquake relief or rescue equipment. In response to criticism, Assad promised to open three border crossings on Monday. Meanwhile, those trapped under the rubble have slowly perished in places like Jindires, and their deaths are a microcosm of what has been happening in northwest Syria for years. Martin Griffiths, the U.N.’s head of emergency relief, tweeted on Sunday, “We have so far failed the people in north-west Syria. They rightly feel abandoned. Looking for international help that hasn’t arrived.”

Though the number of dead remains uncertain, the Mayor of Jindires told us that the death toll stands at twelve hundred. With more aid, it likely could have been lower. After the earthquake struck, just after 4 A.M., survivors overwhelmed the hospital in Afrin. About eight hundred injured people arrived in the first three days, doctors and nurses told me, with another hundred and nine declared dead on arrival. With little ability to pull trapped survivors from collapsed buildings, the number of injured people arriving at the hospital, which is ringed by olive trees, quickly dropped off.

Hospital staffers have developed a grim expertise in treating blunt-force trauma and responding to mass-casualty events after more than a decade of war. They have become experts in keeping people alive. Few places in the world today have endured as much violence for as long a period as rebel-held Syria. Of its almost five million residents, 2.8 million fled there for safety from the Assad regime’s forces. Dr. Yusuf Idris, a surgeon at the hospital in Afrin, told me that, despite years of putting people back together following bombings and artillery stikes, he struggled with the wounds inflicted by the quake. A tall man with a short beard, clad in scrubs, he described the decisions he faced. “Most of the wounded with broken bones can be saved, but smashed bones mean the leg or arm must be amputated, especially if there was a delay of twenty-four or forty-eight hours before they arrived with us,” he said, looking exhausted as he sat in an office chair. “With the war injured, we can easily locate the wound, but with this kind of injury it’s hard; we have to do a full body examination. . . . It could be kidneys or the abdomen.”

Citing the sudden arrival of journalists in the area, he and other hospital staffers bitterly noted that the world seemed more interested in their experiences treating children killed in an earthquake than in their years of fighting to keep children alive during war. They said that they were astounded by the lack of response by the outside world in Syria, compared with Turkey.

International media coverage of the war in Syria, which has killed hundreds of thousands of people and displaced millions, has faded since the Assad regime regained control of large parts of the country with the backing of Russian President Vladimir Putin. But a low-level conflict, with persistently high levels of suffering, continues, as various countries vie for influence in Syria. The Turkish government, which controls entry into the area, has restricted journalists’ access to rebel-held northern Syria in recent years. In the wake of the earthquake, Turkey’s President, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, whose government has been criticized for its slow response to the earthquake inside Turkey, granted foreign journalists permission to cross the border and provided them with escorts.

Afrin’s main hospital is funded by the Turkish government and Qatari charity organizations. It is staffed by a mix of Turkish and Syrian medical professionals. “We are here to extend the compassionate hand of the State of Turkey to the local people,” a hospital manager, Kenan Karcalar, told a group of reporters, as an official from Erdoğan’s office stood nearby. Residents and hospital patients find themselves caught between the various factions competing for influence in Syria, who fight over areas that millions of displaced children now call home. Afrin is currently controlled by a group of rebels that are backed by the Turkish government. Just a few miles to the south of the Afrin hospital is the province of Idlib, which is controlled by a Sunni rebel group called Hayat Tahrir al-Sham that was formerly allied with Al Qaeda.

Upstairs in the hospital, seven-year-old Mohammed defied the chaos surrounding him. In his short life, he has survived years of war and then, after the earthquake, three days beneath the rubble, beside his family members. Of the ten family members in the house, only Mohammed was pulled from the rubble. He, like the two boys on the floor below, stared out at us from under a gray blanket on a metal-framed hospital bed, not saying a word. On the bed next to him sat Yasmine Marjan, an elderly widow. A distant relative, Yasmine is now Mohammed’s only living family member. She showed me photos on her phone of Mohammed in his parents’ arms, beside their two other children—a little girl and baby boy. All of them smiled. Mohammed gazed into the space in front of him, a bruise across his left temple and an I.V. drip in his hand. Salahuddin Hawa, a comparative-literature professor, blamed the Assad regime and its allies in Moscow and Tehran for the lack of aid reaching rebel-held areas. “How can we explain why many airplanes taking aid to Bashar al-Assad could arrive very peacefully in the Assad area, and we find none here?” he asked. “Imagine that this earthquake happened anywhere else around the world. What would the situation be?”

READ MORE

Ukrainian soldiers loading a howitzer in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine on Tuesday. (photo: Tyler Hicks/NYT)

Ukrainian soldiers loading a howitzer in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine on Tuesday. (photo: Tyler Hicks/NYT)

NATO’s Chief Says the Alliance Is Meeting at a ‘Critical Time’ for Its Security

Steven Erlanger and Matthew Mpoke Bigg, The New York Times

Excerpt: "While NATO countries try to ramp up manufacturing, waiting times to secure new large-caliber ammunition have grown from 12 months to 28 months, even if contracts are signed immediately, Mr. Stoltenberg said."

"EDITOR'S NOTE: Two articles here, the first from the NY Times illustrating the understandable alarm on the part of NATO countries closest to the conflict in Ukraine and their urgency to confront it.

The second from the Washington Post painting a portrait of a Biden administration as somewhat detached and feeling less urgency than their NATO counterparts. The Post leans heavily on “confidential sources” warning of a US commitment with a limited shelf-life. The Post account would appear to suggest that the Biden Administration is pressuring Ukraine to produce on the battlefield quickly, because future assistance cannot be guaranteed.

The two narratives are starkly at odds. Is Europe’s alarm over Russia’s aggression warranted? What will Biden and the US do if the situation deteriorates? The Biden Administration seems to be taking the perspective that the US is doing Ukraine a favor by supporting its defense. What if it’s the other way around, what if Ukraine is doing NATO and the US a favor by standing up to Russia?

The Post appears to have dropped the ball here. — MA/RSN"

With Russia bearing down on a strategically important city in eastern Ukraine, NATO defense ministers promised continued military support to Kyiv, whose forces are expending ammunition faster than allies can produce it.

As Russia continues to make gains — particularly around the fiercely contested eastern city of Bakhmut — and the war nears its first anniversary, the U.S. defense secretary, Lloyd J. Austin III, said Western nations were focusing on Kyiv’s “most pressing needs,” including tactical training that could reduce Ukraine’s dependence on artillery fire.

“They have used a lot of artillery ammunition,” he said after meeting with fellow NATO defense officials and the U.S.-led Ukraine Defense Contact Group, a larger group of nations that has pledged military and financial support to Kyiv. “We’re going to do everything we can working with our international partners to ensure that we give them as much ammunition as quickly as possible.”

READ MORE

_______________________ALSO SEE: US Warns Ukraine It Faces a Pivotal Moment in War

President Biden and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky on the White House grounds in December. (photo: Demetrius Freeman/WP)

As the first anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine nears, U.S. officials are telling Ukrainian leaders they face a critical moment to change the trajectory of the war, raising the pressure on Kyiv to make significant gains on the battlefield while weapons and aid from the United States and its allies are surging.

Despite promises to back Ukraine “as long as it takes,” Biden officials say recent aid packages from Congress and America’s allies represent Kyiv’s best chance to decisively change the course of the war. Many conservatives in the Republican-led House have vowed to pull back support, and Europe’s long-term appetite for funding the war effort remains unclear.

Several officials noted the strong bipartisan support that has accompanied every Ukraine package, adding that Congress gave the White House more than it asked for, but they acknowledged that was under a Democratic-led House and Senate.

“We will continue to try to impress upon them that we can’t do anything and everything forever,” said one senior administration official, referring to Ukraine’s leaders. The official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive diplomatic matters, added that it was the administration’s “very strong view” that it will be hard to keep getting the same level of security and economic assistance from Congress.

“'As long as it takes’ pertains to the amount of conflict,” the official added. “It doesn’t pertain to the amount of assistance.”

A senior administration official said the Biden administration will continue to request as much funding as it believes Ukraine needs — as it has done throughout the war — but that there are no guarantees Congress will approve those requests. Republicans took control of the House in January and while many key lawmakers have expressed support for continued funding, the party must also contend with a hard-right flank that has expressed skepticism or opposition to more money for the war.

The war in recent months has become a slow grind in eastern Ukraine, with neither side gaining the upper hand. Biden officials believe the critical juncture will come this spring, when Russia is expected to launch an offensive and Ukraine mounts a counteroffensive in an effort to reclaim lost territory.

Underlining the importance of the moment for the administration, Vice President Harris, Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas are heading to a major security summit in Germany this week and President Biden is traveling to Poland next week for a speech and meetings on the first anniversary.

The Biden administration is also working with Congress to approve another $10 billion in direct budget assistance to Kyiv and is expected to announce another large military assistance package in the next week and the imposition of more sanctions on the Kremlin around the same time.

The critical nature of the next few months has already been conveyed to Kyiv in blunt terms by top Biden officials — including deputy national security adviser Jon Finer, deputy secretary of state Wendy Sherman and undersecretary of defense Colin Kahl, all of whom visited Ukraine last month.

CIA Director William J. Burns traveled to the country one week ahead of those officials, where he briefed Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky on his expectations for what Russia is planning militarily in the coming months and emphasized the urgency of the moment.

At the same time, Biden and his aides are eager to avoid any sign of defection or weakening resolve by Western allies ahead of the Feb. 24 anniversary, hoping to signal to Russian President Vladimir Putin that support for Ukraine is not waning.

But some analysts warned that neither Russia nor Ukraine is likely to seize a decisive military advantage in the foreseeable future.

“It feels like we are playing for a long war,” said Andrea Kendall-Taylor, director of the Transatlantic Security Program at the Center for a New American Security. “I think it’s at odds with what so many people would hope for, that we’re actually trying to help Ukraine win militarily.”

She added, “It feels like a moment of really high uncertainty.”

Biden and his top aides say they are determined to back Ukraine as long and as fully as possible. But they warn that the political path will get tougher once Ukraine has exhausted the current congressional package, which could happen as early as this summer.

Some Western leaders have harbored reservations about sending certain types of heavy weaponry to Ukraine, worried about a direct confrontation with Russia, especially after Putin signaled a willingness to use nuclear weapons.

But loud public lobbying by Zelensky, followed by quiet behind-the-scenes dealmaking by U.S. officials, has changed the dynamic. Biden and Blinken spent much of December and January working to convince allies to help provide Ukraine with the tanks and missiles that his administration had resisted sending for months.

Biden aides encouraged the Netherlands, for example, to help the United States provide critical air defense systems. On Dec. 20, officials at the National Security Council met with senior Dutch officials and stressed the importance the United States was placing on air defense, according to a senior administration official familiar with the meeting, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to reveal details of private discussions.

What the Dutch officials did not know was that the United States was working to bring Zelensky to Washington the next day, where Biden would announce that he was approving a Patriot Missile battery, Zelensky’s top request to help defend against Russian attacks on civilian infrastructure.

The battery needed a launcher — ideally one already in Europe — so Dutch officials worked through the holidays to see how they could assist the United States, the official said. In January, Biden invited the Dutch prime minister, Mark Rutte, to visit the White House, and the Dutch came up with a solution. When Rutte visited on Jan. 17, he said the Netherlands would provide two Patriot Missile launchers and missiles to Ukraine.

But Biden faced challenges on other fronts as well. While Britain had announced it would supply tanks to Ukraine, Germany refused to send its own Leopard 2 tanks or to authorize other countries to transfer their own Leopards — unless the United States agreed to send its prized M1 Abrams tanks to Ukraine.

For much of January, Pentagon and White House officials insisted the M1 Abrams tanks were not well-suited for Ukrainian troops because they are so complicated to operate and maintain. But Biden wanted to avoid the appearance of a fissure in the Western alliance.

In late January, Biden’s Cabinet came up with a plan for the United States to announce the provision of M1 Abrams tanks, which would placate Germany even though the U.S. tanks would not arrive for several months at the earliest. The following the day, Biden gave the go-ahead.

Now, as the United States prepares to send 31 of the premier tanks in the medium term, Europe is quickly assembling two Leopard tank battalions in the near term — the equivalent of at least 70 tanks — in a move that could significantly shift the balance of power on the battlefield.

Yet the public show of unity belies underlying tensions over how Ukraine should focus its resources in the coming months.

The frank discussions in Kyiv last month reflected an effort by the Biden administration to bring Ukraine’s goals in line with what the West can sustain as the war approaches its one-year mark. Getting Ukraine on the same page has not always been easy, according to people familiar with the discussions, speaking on the condition of anonymity to describe private talks.

For months, Ukraine has expended significant resources and troops defending Bakhmut in the eastern Donbas region. American military analysts and planners have argued that it is unrealistic to simultaneously defend Bakhmut and launch a spring counteroffensive to retake what the United States views as more critical territory.

Zelensky, however, attaches symbolic importance to Bakhmut, two senior administration officials said, and believes it would be a blow to Ukrainian morale to lose the city. On Friday, Zelensky said his country’s forces would “fight as long as we can” to hold the embattled city that Russia is on the brink of capturing.

While U.S. officials said they respect that Zelensky knows how best to rally his country, they have expressed concerns that if Ukraine keeps fighting everywhere Russia sends troops, it will work to Moscow’s advantage. Instead, they have urged Ukraine to prioritize the timing and execution of the spring counteroffensive, particularly as the United States and Europe train Ukrainian fighters on some of the more complex weaponry making its way to the battlefield.

“Generally, our view is they should take enough time that they can benefit from what we’ve provided in material and training,” a senior administration official said. If Russia takes Bakhmut, the official said, it “will not result in any significant strategic shift in the battlefield. Russians will try to claim it as such, [but] it’s a dot on the map for which they have expended an extraordinary amount of blood and treasure.”

Beyond Bakhmut, Zelensky has repeatedly rallied his country behind a military campaign to retake all of Russian-occupied Ukraine, including Crimea, the peninsula that Russia annexed in 2014.

Last month, Zelensky’s top aide, Andriy Yermak, reiterated that victory against Russia means restoring Ukraine’s internationally recognized borders, “including Donbas and Crimea.” Anything less is “absolutely unacceptable,” he said at the World Economic Forum in Davos.

U.S. intelligence officials have concluded, however, that retaking the heavily fortified peninsula is beyond the capability of Ukraine’s army right now, according to officials familiar with the matter, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive issues. That sobering assessment has been reiterated to multiple committees on Capitol Hill over the last several weeks.

That discrepancy between aims and capabilities has raised concerns in Europe that the Ukraine conflict will persist indefinitely, overburdening the West as it grapples with other challenges including stubbornly high inflation and unstable energy prices.

Against that backdrop, Biden’s aides say they are pursuing the best course of action: empowering Ukraine to retake as much territory as possible in coming months before sitting down with Putin at the negotiating table.

That effort will benefit from an influx of Patriot missiles, HIMARS launchers and an array of armored vehicles. Optimists see a path for Ukraine to stave off further Russian incursions in the east, retake territory in the south and force Russia to negotiate an end to the war by year’s end.

But skeptics worry that time is not on Ukraine’s side as Russia throws hundreds of thousands of new troops onto the battlefield, including convicts, in advance of the expected spring offensive.

Western and Ukrainian intelligence officials estimate that Russia currently has over 300,000 forces in Ukraine, up from 150,000 initially, with plans to add hundreds of thousands more. The Russian campaign in the spring could see forces pouring over the Belarusian border and cutting off supply lines in western Ukraine that Kyiv has used to bolster its military.

Even seasoned military experts see a wide range of possible outcomes in coming months, underscoring how tenuous the situation is.

“It’s not clear how this ends. Will it end with a negotiated settlement? Will it just be protracted and we’ll see some version of the frozen conflicts we see elsewhere?” said Seth Jones, director of the International Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“You have sufficient support now and the Ukrainians are willing to fight, so there’s strong logic to getting Ukraine as much as you can,” Jones said. “How long you can continue to do that for is an open question.”

READ MORE

"Consider this report a gigantic amber alert that we are issuing on Ukraine’s children," Nathaniel Raymond, executive director of Yale’s Humanitarian Research Lab, said. (photo: Genya Savilov/AFP/Getty Images)

"Consider this report a gigantic amber alert that we are issuing on Ukraine’s children," Nathaniel Raymond, executive director of Yale’s Humanitarian Research Lab, said. (photo: Genya Savilov/AFP/Getty Images)

Thousands of Ukrainian Children Forced Into Vast Russian Network of Russian Camps, Study Finds

Abigail Williams, NBC News

Williams writes: "Russia is running a sprawling network of camps as part of a systematic effort to relocate and re-educate thousands of children from Ukraine, according to a United States government-sponsored study released Tuesday."

“The level of mass re-education is a very clear systematic attempt to erase the history, culture and language of Ukraine,” said one of the report's authors.

Russia is running a sprawling network of camps as part of a systematic effort to relocate and re-educate thousands of children from Ukraine, according to a United States government-sponsored study released Tuesday.

The independent study by the Conflict Observatory, part of the Yale School of Public Health’s Humanitarian Research Lab and established by the State Department to gather evidence of human rights violations in Ukraine after Russia’s invasion, said it had definitively documented around 6,000 Ukrainian children being taken from their homes.

However, the total number of minors “potentially forcibly transferred” to Russia and Russian-occupied territories is likely much higher, even in the several hundred thousand, said Caitlin Howarth, the Conflict Observatory's director of operations.

The Russian program is a “systematic whole-of-government approach to the relocation, reeducation in some cases, adoption and forced adoption of Ukrainian children” involving at least 43 facilities in Russia and spanning all levels of the Russian government, said Nathaniel Raymond, one of the report’s authors and executive director of Yale’s Humanitarian Research Lab.

The age of the children documented in the report ranged from 4 months to 17 years, the study's authors said.

“The level of mass re-education is a very clear systematic attempt to erase the history, culture and language of Ukraine,” she told reporters in Washington during a presentation of the report.

Some children were sent to military training camps in the Russian republic of Chechnya and Russia-occupied Crimea, according to the report. One camp near the Chechen capital, Grozny, was organized at the initiative of Russia’s federal government and was for boys designated to be at risk, including those with criminal records, the study added.

This program has links to the highest levels of government, added Howarth, citing names of senior officials listed and photographed on the camp’s website.

“These are some of the people who have the highest access to people who go straight to the top, to President Vladimir Putin himself and of course to the top of the Chechen Republic,” she said.

Ukraine's government did not immediately respond to requests for comment on the report's findings, but from the early days of the invasion, Kyiv has accused Russia of forcibly transferring children and adults.

Russian officials have consistently denied the accusations, calling them a “fantasy.” In August, the Russian Department of Information and Press said in a statement to NBC News that the allegations were “groundless and are conjectures aimed at discrediting Russia.”

Russia's embassy to the United States said on Wednesday that the country had taken in children who were forced to flee the fighting."

"Russia accepted children who had been forced to flee with their families from the shelling," the embassy said on the Telegram messaging platform. "We do our best to keep minors in families, and in case of absence or death of parents and relatives — to transfer orphans under guardianship. We ensure the protection of their lives and well-being."

But Raymond, the study co-author and a lecturer in the Department of Epidemiology of Microbial Diseases at the Yale School of Public Health, said, “All levels of Russia’s government are involved. ... This is not just a federal operation — it involves … at least four regional governors and local officials, including in some cases, civil society.”

“Basically consider this report a gigantic amber alert that we are issuing on Ukraine’s children,” Raymond added.

At least 12 people in the chain of command headed up by Russia’s commissioner for child rights, Maria Lvova-Belova, are not on the U.S.’s international sanctions list, according to the authors of the report.

The study’s authors added that the actions described in the report are a violation of the Geneva Convention — which prohibits the change of a child’s personal status, including nationality — and may constitute a war crime or crimes against humanity.

International human rights groups like Amnesty International have also documented the forced relocation of thousands of Ukrainian civilians. In November, Amnesty highlighted the “plight of unaccompanied, separated or orphaned children,” deeming the cases as “particularly concerning.”

In August, the U.S. said at the U.N. Security Council that it had evidence that “hundreds of thousands” of Ukrainian citizens had been interrogated, detained and forcibly deported to Russia in “a series of horrors” overseen by officials from Russia’s presidency.

The charge came during a meeting to discuss Russian so-called filtration operations, which involve Ukrainians who are fleeing the war being forcibly moved to Russia and passing through a series of “filtration points.”

At the time, U.S. Ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield said estimates indicated that thousands of children had been subjected to filtration.

READ MORE

Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan visits the city center destroyed by last the Feb. 6 earthquake in Kahramanmaras, southern Turkey, on Feb. 8. (photo: Turkish Presidency/AP)

Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan visits the city center destroyed by last the Feb. 6 earthquake in Kahramanmaras, southern Turkey, on Feb. 8. (photo: Turkish Presidency/AP)

Videos Show Turkey's Erdogan Boasted Letting Builders Avoid Earthquake Codes

Peter Kenyon, NPR

Kenyon writes: "As Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan struggles to defend his response to last Monday's devastating 7.8 magnitude earthquake, videos from a few years back have emerged showing him hailing some of the housing projects that crumbled, killing thousands of people."

As Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan struggles to defend his response to last Monday's devastating 7.8 magnitude earthquake, videos from a few years back have emerged showing him hailing some of the housing projects that crumbled, killing thousands of people.

Critics say contractors were allowed to skip crucial safety regulations, increasing their profits but putting residents at risk.

The videos have fueled public outrage over slow efforts to help residents in the aftermath of the massive earthquake — the world's deadliest in over a decade — that killed more than 35,000 people in Turkey and neighboring Syria, and left many injured and without a home, food or heating in the middle of winter.

In one video, taken during a campaign stop ahead of Turkey's March 2019 local elections, Erdogan listed some of his government's top achievements — including new housing for the city of Kahramanmaras, also known as Maras, near the epicenter of last week's quake.

"We solved the problem of 144,156 citizens of Maras with zoning amnesty," Erdogan said, using his term for the construction amnesties handed out to allow contractors to ignore the safety codes that had been put on the books specifically to make apartment blocks, houses and office buildings more resistant to earthquakes.

Engineers and architects say the lack of safety features designed to absorb the shock of earthquakes likely contributed to the soaring death toll.

In another 2019 campaign stop, in southern Turkey's Hatay province, Erdogan was again eager to tout the housing his government was creating.

"We have solved the problems of 205,000 citizens of Hatay with zoning peace," he said, using another name for the amnesties being used to facilitate construction practices that could leave buildings unable to withstand earthquakes.

The videos were reported by Turkish news sites such as Duvar and Diken, and have circulated widely.

Duvar cited a senior Istanbul city official, Bugra Gokce, who gave a breakdown of the tens of thousands of building amnesty certificates granted before the 2018 general election in 10 provinces struck by the earthquake. They included more than 40,000 amnesty certificates in the hard-hit Gaziantep province, the official said.

The amnesty meant that some builders had to pay a fine but their construction projects could go forward if they didn't meet code restrictions, according to Turkish media reports.

Erdogan has acknowledged some initial problems with the country's response to the earthquake, but he has said no government could be ready for a disaster of this magnitude.

However, Turkey's main opposition leader, Kemal Kilicdaroglu, said that "If there is one person responsible for this, it is Erdogan."

And the country's main association of engineers and architects weighed in with a scathing attack on the practice of amnesties for builders, saying, "Zoning amnesty is an invitation to death."

The association added, "In our country, zoning amnesties have been one of the most important incentives for illegal construction and have made it uncertain for the society to live in healthy and safe houses." The group said the practice is used "for the sake of political gain," and must be stopped.

Turkey's Duvar news site posted a tweet from Erdogan from 2013, marking the anniversary of the 1999 Marmara earthquake that killed more than 17,000 people. It said: "Buildings kill, not earthquakes. We need to learn to live with earthquakes and take measures accordingly."

READ MORE

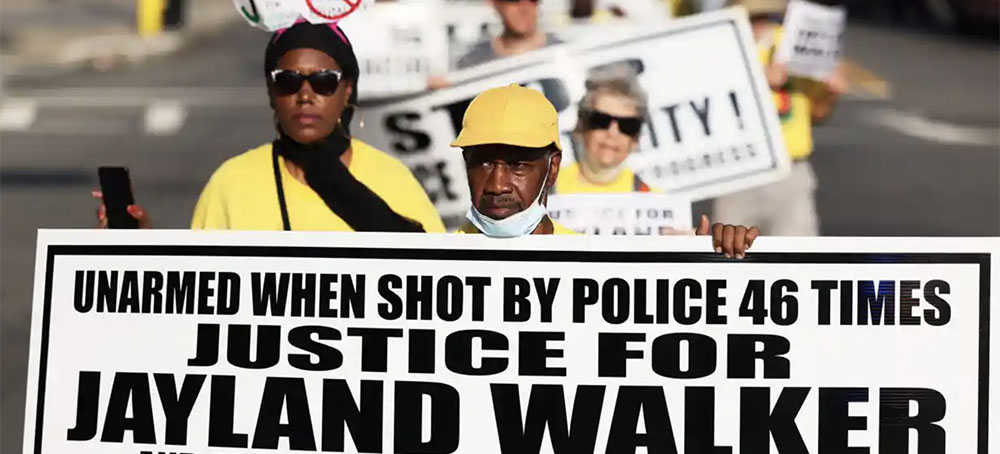

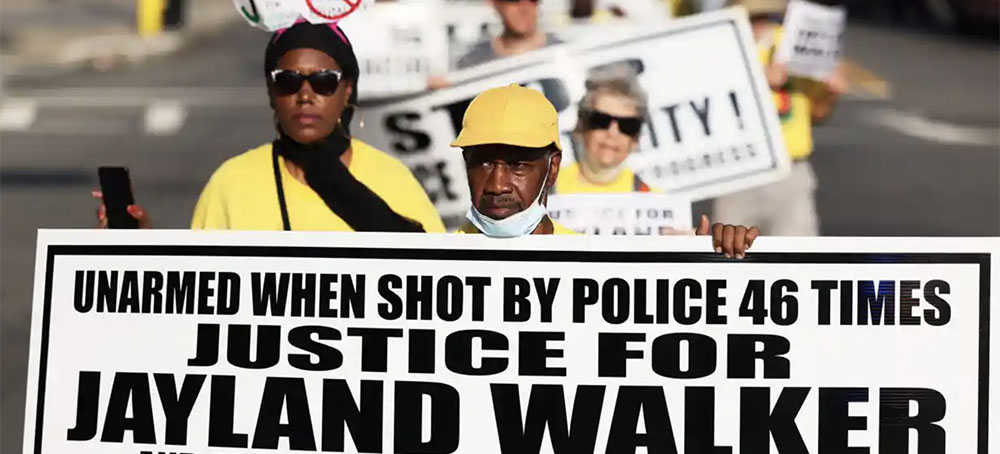

A protest in Newark, New Jersey, on 15 July 2022, demanding justice for Jayland Walker who was killed by police in Akron, Ohio, a month earlier. (photo: Michael M Santiago/Getty Images)

A protest in Newark, New Jersey, on 15 July 2022, demanding justice for Jayland Walker who was killed by police in Akron, Ohio, a month earlier. (photo: Michael M Santiago/Getty Images)

One in 20 US Homicides Are Committed by Police – and the Numbers Aren’t Falling

Lois Beckett, Guardian UK

Beckett writes: "In the US, an estimated one in 20 gun homicides are committed by police, as law enforcement killings have failed to decrease despite years of nationwide protests."

Police killings of any sort account for nearly 5% of all homicides, with at least 1,192 people killed by law enforcement in 2022

In the US, an estimated one in 20 gun homicides are committed by police, as law enforcement killings have failed to decrease despite years of nationwide protests.

Law enforcement officers killed at least 1,192 people in 2022, the highest number recorded in a decade, according to Mapping Police Violence, a prominent non-profit database of police killings. More than 1,100 people were killed by the police in both 2020 and 2021. The vast majority of these deaths were police shootings.

There were more than 25,000 total homicides in the US in 2020 and 26,000 in 2021, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National data for 2022 is not yet available.

Police shooting deaths represented 5% of all gun homicides in 2020 and 2021, and total police killings represented nearly 5% of all homicides, according to the best available public data.

Because only a small number of deadly incidents each year receive wide media attention, many Americans may not realize that “a meaningful fraction of homicides in the US are police killings”, said Justin Feldman, a researcher at the Center for Policing Equity.

The number of US homicide victims who die in mass shootings each year, for instance, is smaller than the number killed by police. While definitions of “mass shooting” vary, the estimated number of people killed in these incidents have ranged from a few dozen to 700 people a year in recent years.

“There is a lot of fear, with mass shootings and gun violence in general, that some stranger will show up wherever you are and kill you,” said Samuel Sinyangwe, the founder of Mapping Police Violence. “But police contribute a large part to those numbers.”

The circumstances for many murders are listed as unknown in the FBI’s incomplete national crime statistics database, but in 2020 nearly 4,000 people were listed as being killed by a friend or an acquaintance, and about 1,800 were known to be killed by a stranger.

Some police departments have much higher rates of police killings than others. In Vallejo, California, which is known for police violence, the police department was responsible for 30% of the city’s homicides in 2012. Police killed six people that year; a single officer killed three people in three different incidents, and was later promoted.

More than 32,000 Americans have been killed by police since 1980, but official public health statistics have undercounted the number of killings for decades, according to a 2021 study from University of Washington researchers published in the Lancet, a prominent medical journal. Over the past four decades, US police have killed Black people at a rate 3.5 times higher than white people, and have also killed Hispanic and Indigenous people at higher rates, the study estimated.

The rate of fatalities from police violence rose even when the nation’s overall homicide rate sharply declined, with the rate of deaths from police violence rising 38% from the 1980s to the 2010s, the study found.

The US has much higher rates of both police killings and overall homicides than other wealthy countries. In Europe, the combined number of police killings and state executions remains in the single digits each year in many countries, according to data from the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). The US’s annual rate of police killings and state executions, with more than 1,000 deaths a year, is more comparable to Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, Cameroon, Libya and Sudan, according to IHME data.

At least one international study has found the rate of police killings “strongly correlates” with overall homicide rates across multiple countries, but also noted that data on police violence is likely to be less reliable in countries where police kill more frequently.

A 2018 paper published in the American Journal of Public Health found that “police were responsible for about 8% of all homicides with adult male victims between 2012 and 2018”, or about one in 12. Frank Edwards, a Rutgers University sociologist and the lead author of that study, said it was not surprising that the current percentage of police homicides would be somewhat lower than 8% when factoring in the killings of women and well as men, and as the national total number of homicides had also increased sharply since 2020.

Public databases from news outlets and non-profits still offer more complete and reliable data on police killings than the US government, more than seven years after the nation’s FBI director called it “embarrassing and ridiculous” that newspapers produced a more accurate national count of US police shootings than the Department of Justice. Mapping Police Violence, for instance, tracks police killings using a combination of state law enforcement data and incident data drawn from media reports and public records requests.

It’s not only national crime data that’s flawed when it comes to homicides by police. For decades, more than half of police killings have been mislabeled as generic homicides or suicides in the CDC’s official death statistics database, said Eve Wool and Mohsen Naghavi, two of the authors of the Lancet paper on police killings.

The undercounting of police killings in public health data is a result of coding failures by coroners, medical examiners and other public health officials, many of whom “work for or are embedded within police departments”, the researchers found.

Because of the lack of official statistics, Feldman and Edwards said, comparing the count of police killings in non-profit databases like Mapping Police Violence with the CDC’s total homicide numbers is the most accurate way to estimate the percentage of homicides committed by police.

READ MORE

Gharidah Farooqi prepares Wednesday in the TV studio of News One in Islamabad, Pakistan, for her live evening show. (photo: Saiyna Bashir/WP)

Gharidah Farooqi prepares Wednesday in the TV studio of News One in Islamabad, Pakistan, for her live evening show. (photo: Saiyna Bashir/WP)

These Women Journalists Were Doing Their Jobs. That Made Them Targets.

Taylor Lorenz, The Washington Post

Lorenz writes: "Tackling difficult subjects and holding powerful people accountable often triggers online attacks that torment and humiliate women journalists. Some even lose their jobs as news organizations struggle to respond to the hate."

Tackling difficult subjects and holding powerful people accountable often triggers online attacks that torment and humiliate women journalists. Some even lose their jobs as news organizations struggle to respond to the hate.

When Gharidah Farooqi interviews a male politician for television, she does research and plans out her questions, as any journalist would. She is professional, well-dressed and asks pertinent follow-up questions.

But every move she makes, every gesture and expression, is scrutinized by mobs of observers online. Everything — the clothing she wears, the questions she asks while interviewing someone — is fuel for an avalanche of mostly anonymous online abuse that for years has ridiculed her and her work.

“I see my male counterparts — they’re also abused, but not abused for their bodies, their genital parts,” she said. “If they’re attacked, they’re just targeted for their political views. When a woman is attacked, she’s attacked about her body parts.”

The ordeal of Farooqi, who covers politics and national news for News One in Pakistan, exemplifies a global epidemic of online harassment whose costs go well beyond the grief and humiliation suffered by its victims. The voices of thousands of women journalists worldwide have been muffled and, in some cases, stolen entirely as they struggle to conduct interviews, attend public events and keep their jobs in the face of relentless online smear campaigns.

Stories that might have been told — or perspectives that might have been shared — stay untold and unshared. The pattern of abuse is remarkably consistent, no matter the continent or country where the journalists operate.

Farooqi says she’s been harassed, stalked and threatened with rape and murder. Faked images of her have appeared repeatedly on pornographic websites and across social media. Some depict her holding a penis in the place of her microphone. Others purport to show her naked or having sex. Similar accounts of abuse are heard from women journalists throughout the world.

A non-scientific survey of 714 women journalists in 215 countries for a 2021 report by the nonprofit, Washington-based International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) found that nearly 3 of 4 had suffered online abuse in their work. And nearly 4 of 10 said they became less visible as a result — losing airtime, bylines or professional opportunities.

“Online violence against women journalists is one of the most serious contemporary threats to press freedom internationally,” the report declared. “It aids and abets impunity for crimes against journalists, including physical assault and murder. It is designed to silence, humiliate, and discredit. It inflicts very real psychological injury, chills public interest journalism, kills women’s careers and deprives society of important voices and perspectives.”

In many countries, women who are targeted in these campaigns are doing some of the most crucial journalistic work in their regions: investigating powerful cultural leaders, exposing government wrongdoing and revealing corruption. Many who are targeted report on the internet itself and how it is being used to bolster extremists.

Social media platforms that optimize for engagement and a media landscape that rewards outrage and hyperbole fuel digital attacks. Online abusers manufacture controversy about specific women, stalking and harassing them and their families. Time and again, research shows, the news organizations that employ women journalists who are under assault turn against them, depriving them of career opportunities and driving them from the profession.

Farooqi dealt with an especially bad attack in 2019, after she tweeted a news story reporting that the man who gunned down 51 Muslims at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand — and live-streamed the attack on Facebook — had visited Pakistan the year before.

The internet erupted with allegations that Farooqi was trying to malign Pakistan by unfairly linking it with a terrorist attack thousands of miles away. People online called for her abduction, rape and murder. In response, the Committee to Protect Journalists, the International Federation of Journalists, the Digital Rights Foundation, the Freedom Network and Amnesty International all issued statements of support for Farooqi.

The onslaught of harassment became so unrelenting and the threats so constant that for nearly four months, Farooqi rarely left her house, skipping trips to shop or visit friends. She left her house only to travel to and from the office. Each time she stepped out of a car, she nervously scanned her surroundings to see if anyone appeared to be watching her too intently.

Online attacks are amplified in mainstream news coverage.

In October, former Pakistani prime minister Imran Khan was asked about Farooqi while speaking to a delegation from Pakistan’s National Press Club and the Rawalpindi Islamabad Union of Journalists.

Khan responded, “If she would invade male-dominated spaces, then she is bound to be harassed.”

Killing of Indian editor sparks an investigation

This article is part of “Story Killers,” a reporting project led by the Paris-based journalism nonprofit Forbidden Stories, which seeks to complete the work of journalists who have been killed. The inspiration for this project, which involves The Washington Post and more than two dozen other news organizations in more than 20 countries, was the 2017 killing of the Indian journalist Gauri Lankesh, a Bangalore editor who was gunned down at a time when she was reporting on Hindu extremism and the rise of online disinformation in her country.

New reporting by Forbidden Stories found that shortly before her slaying, Lankesh was the subject of relentless online attacks on social media platforms in a campaign that depicted her as an enemy of Hinduism. Her final article, “In the Age of False News,” was published after her death.

Even when threats do not escalate to physical attacks, they can be debilitating for women journalists and their ability to report.

The Post spoke to five major journalism advocacy groups that have tracked incidents of online abuse against women journalists around the world, as well as researchers who study disinformation and online hate campaigns. The Post also interviewed 13 women journalists from a wide variety of regions about the effect hate and smear campaigns have had on their careers.

The playbook typically unfolds like this: Powerful people, usually popular online figures or government officials, target a woman journalist who is subjecting them to public scrutiny, often over allegations of wrongdoing. Journalists who have declared themselves feminists or have advocated for more diversity and inclusion in the news industry are particularly popular targets for online hate, experts in online harassment say.

The attacks follow a pattern that is consistent across countries and regions, generating controversy over everything a woman does and says. The endless stream of headlines brands the woman as controversial and difficult, which discourages news outlets from hiring or promoting her. A common tactic is to investigate and speculate on a woman’s personal life and relationship status to create controversy.

The result frequently is that the target is pushed out of her job or forced to quit. Others fade away, staying in the business but in less prominent roles. Very few women are able to navigate these waters successfully, experts found in their research.

Aryee Davis, 35, a Liberian journalist, faced a crushing backlash after she reported that a powerful lawmaker had lied about his university degree. The lawmaker claimed to have attended a university in Nigeria that had no record of him as a student.

Since the incident, most of her stories no longer carry bylines. For safety reasons, they describe Davis, instead, as a “contributing writer.”

“People felt that I was behaving more like a man than a woman,” she said. “They say that story should have come from a man. The media in Liberia is dominated by men. The women who have the courage to join them are harassed, bullied. … People think a woman should just write human interest stories, maybe a kid in the streets selling something, or a man abandoning his wife.”

The attacks against Davis and threats against her family became so intense after her scoop on the politician’s university degree that she pulled her children out of school for several weeks for their safety. The Committee to Protect Journalists, which researched her claims, condemned the attacks.

Women journalists around the world report that their employers punish them for speaking about their experiences of online abuse or engaging with those attacking them. The women who are targeted are told to avoid posting on social media, thereby silencing them and taking away their platform, career opportunities and ability to define their own narrative, interviews show.

Maria Ressa, a Nobel Peace Prize recipient and co-founder and chief executive of Rappler, an online news outlet in the Philippines, who herself has been harassed online and threatened with violence, said that telling women who are targeted not to respond fails to recognize how the internet has transformed the media landscape into a place where anyone with a computer or smartphone can further a smear campaign. “If you don’t respond to [the smears and online attacks], the lie told a million times becomes a fact,” she said. “It’s about power. And the people who held power in the old world [legacy institutions] don’t understand the power of the new world.”

The 2021 report by the ICFJ and UNESCO found that several women lost their jobs or were punished by their news organizations after becoming a target of online attacks. Women who took steps to protect children and other family members reported being punished by their employers, who treated their efforts as a public relations problem.

“It’s extremely troubling when you see women journalists being penalized, whether they’re being suspended or sometimes even sacked, in the middle of an online violence campaign, and we see this happen to journalists around the world,” said Julie Posetti, the ICFJ’s global research director. “Heavily partisan pseudo-journalists and disinformation agents trigger pile-ons against particular journalists and lace attacks with disinformation with the view to discredit them. Ultimately, they discredit the journalist not just with their audience but also to their employers, who in the worst cases have pushed them out of their jobs.”

“A corporate PR approach to managing what a journalist says in response to their abuse is deeply problematic,” Posetti added. “It removes the sense of autonomy, it removes the sense of empowerment from a journalist deciding to address online violence.”

Attacks in Turkey, Nigeria, Brazil

The Turkish journalist Amberin Zaman has received a stream of death threats and threats of sexual violence — many of them visible to the public on social media — for reporting on the Turkish government and Syria. People manipulate images to depict her being beheaded or hit with a drone strike.

“Social media is the perfect medium for this,” Zaman said. “In the past, when the government wanted to go after me, they’d use the print press or TV. But a news article or TV segment maligning me had nowhere near the reach of social media. It amplifies all the smears.”

Articles about Zaman are circulated by partisan influencers online. What she posts online is monitored and dissected, and has prompted dubious legal claims against her. She says the harassment has robbed her of the ability to speak freely and to express herself on the internet. Her coverage of a U.S.-allied Kurdish group in northern Syria that Turkey considers a terrorist organization makes her especially vulnerable.

“Let’s say I tweet out an interview with a [Kurdish] general who’s a U.S. ally against ISIS [and] who Turkey says is a terrorist,” she said. “I tweet that out, and they construe that as terrorist propaganda, and a ‘concerned Turkish citizen’ will file a criminal complaint against me in Turkish court.”

Several terrorism investigations are pending against Zaman, including one in which an arrest warrant has been issued. She has not returned to her home country in six years. She fled to London and was unable to return even to attend her mother’s funeral in 2020 for fear of being arrested.

“The psychological impact is undeniable,” Zaman said. “On one hand, you’re desensitized — with each new battle, your skin grows thicker — but it takes a toll on you. In the worst instances, sometimes you begin questioning yourself and wondering whether what they’re saying about you is true. And, of course, it’s horrible to have so much violence and hatred directed at you.”

She added, “Nobody wants to be hated. Emotionally, it takes a toll on you. It’s exhausting. It robs time and energy that would be better deployed researching my stories. I feel physically vulnerable.”

In 2022, the Association of European Journalists, an independent professional network of those reporting on European and international affairs, condemned the attacks against Zaman.

The Nigerian journalist Kiki Mordi fled her home country after becoming a target of online abuse. After producing a documentary in 2019 for the BBC on the sexual harassment and abuse of women in the country’s university system, she was met with a wave of vicious online attacks.

The smear campaign has irrevocably damaged her ability to speak freely and do her job, she says. Her social media posts are scrutinized and misrepresented. She has been the subject of multiple conspiracy theories about her work that have cast doubt on her credibility as a journalist. The campaign to discredit her investigation has played out on YouTube, Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and across the mainstream Nigerian media.

She has changed her residence multiple times after trolls threatened her on social media and published identifying personal details, including her home address, phone numbers and information about her family members and friends.

Attacking women journalists is a fast, easy way to generate engagement on social media, experts say. Platforms reward outrage, and cottage industries have formed around attacking certain prominent women journalists. According to a 2021 study by Yale University, “social media platforms amplify expressions of moral outrage because users learn such language gets rewarded with an increased number of ‘likes’ and ‘shares.’”

“The polarizing algorithms that pull us apart and radicalize us work at a psychological level, at a sociological level, and literally change emergent human behavior,” said Ressa, the Rappler co-founder.

Ressa has been threatened with rape and murder, and relentless online abuse is promoted with hashtags like #ArrestMariaRessa. “Online violence inevitably becomes real-world violence, which is why the tech platforms shouldn’t be allowing this,” she said. “Women, and our countries in the Global South have borne the brunt of it, and the evidence is clear.”

YouTubers and partisan media figures know that posting about certain women is an effective way to get attention and clicks, and so these women’s images are used in YouTube thumbnails to draw attention to full videos, experts say. The journalists are posted about frequently and are turned into characters on the internet. Nearly everything they do is framed as a controversy. A report issued last year by the Center for Countering Digital Hate declared that “misogyny is alive and well on YouTube” and “videos pushing misinformation, hate and outright conspiracies targeting women are often monetized.”

Searching Mordi’s name on YouTube, for instance, reveals several videos promoting lies about her personal life and career. She said internet trolls have used online tools to swap her head onto pornographic imagery, and they virtually stalk those associated with her. Mordi says this has caused her to back away from the internet.

“I can be searching for something random and I find someone saying something hurtful about me in the results,” she said. “I’ve stopped doing that. I’ve been grounded with anxiety for days, not being able to work, not being able to focus. The time I was doxed I had to turn off my phone; no one could reach me and I couldn’t properly get work done.” (Doxing is publishing a person’s private information on the internet, usually maliciously.)

She moved to London last year to distance herself from the relentless online attacks. But the internet has no geographic boundaries, and the move failed to separate her from the onslaught. She has stopped focusing so heavily on her own reporting, instead producing documentary films for clients, but the online attacks have made landing jobs difficult.

“Every day I look in the mirror and try to convince myself I’m not silenced, I’m just choosing peace,” she said. “But the reality is that I am silenced.”

Juliana Dal Piva, 36, has been a journalist in Brazil for nearly 15 years, reporting on political corruption, misinformation, and the rise of far-right political leader Jair Bolsonaro. In 2015, she began to see how Facebook was being leveraged to promote misinformation.

“We understood that people were reading news feed as a media outlet,” she said. “They weren’t able to understand that anybody can publish anything on the news feed.”

The next year, one of Bolsonaro’s sons, Flávio Bolsonaro, was running for mayor of Rio de Janeiro. Dal Piva fact-checked a number of his claims on Agência Lupa, an outlet that assesses the accuracy of text, audio and video reports, and the hate rolled in. Far-right influencers and politicians began spreading lies about her work and her personal life. Someone created a dossier on her with detailed information — including where she worked, where she studied, a photo of her — and distributed it online.

“I remember it was like one comment at each minute, thousands of comments in a few hours, and only on that post about the fact-checking on Bolsonaro’s son,” Dal Piva recalled. “A lot of comments with hate speech.”

She tried to protect her family, asking them to change their names on social media and remove her as a friend. Things calmed down for a while, but when Bolsonaro came to power in 2019, the attacks escalated.

As in other cases of women being targeted, there was a fixation on Dal Piva’s relationship status and sexuality. Many right-wing detractors tried to hunt down her personal connections, including whether she had a romantic partner and if she was a member of the LGBTQ community.

Dal Piva’s life has shrunk because of the threats. She has fled her residence and is on her guard when she is around people she doesn’t know. People monitor her social media posts, she said, and seek to generate controversy around her opinions and reporting. Anyone associated with her, she said, is targeted, including her family, friends and news sources.

She feels that her work has been overshadowed by the smear campaign. “I felt marked,” she said. “I don’t like to feel that this threat and what happened was bigger than my work. My work is what should be known.”

The attacks also have made doing her job more difficult, she says. She no longer feels safe reporting on certain major events. Dal Piva said she was unable to cover the attack on Brazilian government buildings last month because of the level of credible threats against her online.

After the harassment and threats began, “it took me sometimes days to write something I used to do in a few minutes,” she said. “It was difficult to concentrate. I was feeling that if I broke other important stories, everything would happen again.”

When Dal Piva goes out in public, she wears a mask and glasses to be more inconspicuous. She avoids crowds, and she did not cover any campaign events during last year’s election season out of concern for her safety.

She wrote a book about Bolsonaro, but the normal events that go with launching a book became difficult. She had to have security, and gatherings had to be smaller and more tightly controlled. She couldn’t have the large parties and public readings that other authors enjoy.

The need for security guards has made it harder for her to attract and retain sources. “How am I going to meet sources like that, with security all around me? I felt like I was losing something for not being able to be there at these events,” she said. “But my sources have to be safe, too.”

Nine years of online abuse

Farooqi’s troubles began in 2014 when she began covering the Pakistani politician Imran Khan and the rise of the political party he founded, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, or Movement for Justice. Khan, who would become prime minister four years later, showed a rare knack for exploiting Twitter.

Pakistan is a particularly hostile environment for women journalists. Only 5 percent of journalists in the country are women, according to the Digital Rights Foundation, a press freedom group, and Pakistan is the second-most-hazardous country for journalists in general, according to the Press Freedom Index.

When Khan took to the streets that summer to lead a long march against the government, Farooqi was thrust into the online spotlight. She did extensive interviews with members of Khan’s party and with ordinary voters, as well. She reported on the rallies and marches, and more and more people began following her work.

“Not many women journalists were out there. I was perhaps the only [woman] journalist out covering that political protest,” she recalled.

That national attention triggered the first, relentless wave of online abuse, largely from supporters of Khan’s political party, some of whom were party members. They instigated an aggressive campaign to discredit her, she said.

People began taking photos of her interviewing powerful political leaders and altering them to make them profane or pornographic. People began accusing her of fabricating stories, of being dishonest and biased, of abusing children and betraying the country. They said she was in journalism only so that she could have sex with powerful men and become famous. The Digital Rights Foundation condemned the abuse.

“Farooqi was facing harassment mainly because she was a journalist, but the kind of engendered harassment she was facing was because she was a woman,” Nighat Dad, a Pakistani lawyer who heads the DRF, said in a statement. “It is highly condemnable that women journalists are frequently subjected to online violence and rape threats, which affect their ability to conduct unbiased journalism, and are tools for their self-censorship, and to silence them.”

Said Farooqi of the abuse: “I tried to ignore it, but it kept worsening and worsening, and there was no stop to it.”

In 2016, Zartaj Gul Wazir, a female political leader in Khan’s party, recorded a video in which she falsely accused Farooqi of having affairs with certain politicians to further her career. She posted it across social media platforms including Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. The video remains online to this day.

At times, Farooqi has tried to seek legal recourse against her online attackers. She filed a report with the cybercrime wing of the FIA, Pakistan’s federal investigation agency. The complaint went nowhere, as did subsequent complaints, she said.

In 2018, when Khan was elected prime minister and his political party gained more power, the attacks on Farooqi intensified. With Khan’s party in control, she said, seeking help from the authorities became an even more fruitless pursuit. Meanwhile, the groups attacking her became more powerful.

Farooqi wrote to Khan and the opposition leader in Parliament seeking help, she said. She wrote to the Pakistani Senate and informed members about the threats and harassment, but the abuse never stopped.

After she suggested online that people should not sacrifice animals to celebrate the Islamic festival of Eid al-Adha, two petitions were lodged against her in Pakistan’s high court accusing her of blasphemy — a serious charge in Pakistan, where it can be punishable by death and where such accusations can lead to fatal vigilante attacks. The investigations against her are still active, and two major TV channels ran segments denouncing her.

Farooqi’s personal relationship status is a particular fixation for online trolls. YouTube videos and tweets speculating on Farooqi’s “secret marriage” went viral online from 2016 to 2018.

Farooqi said that the endless speculation over a woman’s personal life is part of the abuse women endure simply for doing their jobs. “Men are really obsessed with if a woman journalist is single or if she’s married,” she said, “and if she’s married, what’s the status of her marriage, and if she’s divorced, then what’s the reason, and if she’s single, then it’s a crime. In the field of journalism, you can’t be a single woman; you’re suspected with all kinds of nasty ideas. If she’s still single, that means she’s having multiple affairs.”

The ICFJ’s Posetti said the response of a woman’s news organization is critical to protecting her from such harassment. Women journalists should never be compelled by their news organizations or their attackers to reveal or confirm intimate details of their personal relationships, she said, especially when highly credible threats of violence are involved and family members are under attack.

“You do not have to subject yourself to any kind of perceived right to exposure, as though [the way a woman speaks about her personal life] is somehow going to reflect the transparency or accountability of a news organization,” she said. “Women need to be given the autonomy to determine, when they are targeted, how they respond, and specifically with reference to trying to protect their family members who have nothing to do with the operation of the news organization they work for.”

Until news organizations recognize the purpose of harassment campaigns and learn to navigate them appropriately, experts say, women will continue to be forced from the profession and the stories they would have reported will go untold.

“This is about terrifying female journalists into silence and retreat; a way of discrediting and ultimately disappearing critical female voices,” Posetti said. “But it’s not just the journalists whose careers are destroyed who pay the price. If you allow online violence to push female reporters out of your newsroom, countless other voices and stories will be muted in the process.”

“This gender-based violence against women has started to become normal,” Farooqi said. “I talk to counterparts in the U.S., U.K., Russia, Turkey, even in China. Women everywhere, Iran, our neighbor, everywhere, women journalists are complaining of the same thing. It’s become a new weapon to silence and censor women journalists, and it’s not being taken seriously.”

READ MORE

Smoke rises from a derailed cargo train in East Palestine, Ohio, on Feb. 4. (photo: Dustin Franz/AFP/Getty Images)

Smoke rises from a derailed cargo train in East Palestine, Ohio, on Feb. 4. (photo: Dustin Franz/AFP/Getty Images)

Health Concerns Grow in East Palestine, Ohio, After Train Derailment

Juliana Kim, NPR

Kim writes: "Health and environmental concerns are mounting in East Palestine, Ohio, after several derailed train cars released toxic fumes last week."

Health and environmental concerns are mounting in East Palestine, Ohio, after several derailed train cars released toxic fumes last week.

On Feb. 3, about 50 cars of a Norfolk Southern train went off track in Ohio, causing a days-long fire in the area. Ten of the 50 derailed cars contained hazardous chemicals including butyl acrylate and vinyl chloride, which were among combustible liquids that authorities feared could set off a major explosion.

Residents of East Palestine were later asked to evacuate out of precaution. On Monday, Feb. 6, crews conducted what officials called a "controlled release" of the hazardous chemicals, which caused a large plume of black smoke.

The evacuation order was lifted on Wednesday and since then, there have been a growing number of reports about people experiencing a burning sensation in their eyes, animals falling ill and a strong odor lingering in the town.

Some business owners and East Palestine residents have filed lawsuits against Norfolk Southern, saying the company was negligent and demanding the company fund court-supervised medical screenings for serious illnesses that may be caused by exposure to those chemicals.

Air quality continues to be monitored indoors and outdoors

Local officials have insisted that the air is safe to breathe and the water is safe to drink in East Palestine.

The Environmental Protection Agency, which has been monitoring the air quality, said it has not detected "any levels of concern" in East Palestine as of Sunday.

The agency added that vinyl chloride and hydrogen chloride have not been detected in the 291 homes that have been screened as of Monday. There are 181 homes left to be evaluated in the voluntary indoor air screening program.

Released toxic fumes have short and long-term side effects

On Sunday, the EPA released a list, written by Norfolk Southern, of the toxic chemicals that were in the derailed cars. In addition to vinyl chloride and butyl acrylate, it mentions ethylhexyl acrylate, which can cause headaches, nausea, and respiratory problems in people exposed to it; as well as isobutylene, which can make people dizzy and drowsy.

Of particular concern is the vinyl chloride, which was loaded on five cars — a carcinogen that becomes a gas at room temperature. It it commonly used to make polyvinyl chloride or PVC, which is a kind of plastic used for pipes, wire and cable coatings and car parts.

When vinyl chloride is exposed in the environment, it breaks down from sunlight within a few days and changes into other chemicals such as formaldehyde. When it is spilled in soil or surface water, the chemical evaporates into the air quickly, according to the Ohio Department of Health.

Breathing or drinking vinyl chloride can cause a number of health risks including dizziness and headaches. People who breathe the chemical over many years may also experience liver damage.

The EPA has been monitoring for several other hazardous chemicals, including phosgene and hydrogen chloride, which are released by burning vinyl chloride. Exposure to phosgene can cause eye irritation, dry burning throat and vomiting; while hydrogen chloride can irritate the skin, nose, eyes and throat, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The Columbiana County Health Department told residents to reach out to their medical provider if they experience symptoms.

An expert recommends cleaning surfaces and vacuuming carefully

The harmful effects of these toxic chemicals largely depend on the concentration and exposure.

"Now that we are entering into a longer-term phase of this, people are going to be concerned about the long-term chronic exposure that comes at lower levels," said Karen Dannemiller, a professor at Ohio State University who studies indoor air quality.

She added that indoor spaces can be an important point of exposure, which is why she urges East Palestine residents to take part in the EPA's at-home air screening.

Dannemiller recommends that residents wipe down surfaces, especially areas that collect dust, and wash items that absorb smells, such as bedsheets and curtains. She also advises vacuuming carefully in short bursts to try to prevent contaminants from moving into the air.

Air cleaners and masks are likely no match for hazardous chemicals like vinyl chloride because of their tiny molecules, Dannemiller told NPR.

READ MORE

Contribute to RSN

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

Update My Monthly Donation

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611