15 March 22

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

TIME TO THINK ABOUT WHAT RSN MEANS — Time is short, it’s the 15th day of the month and only 170 Readers have donated so far. Those are some of the worst numbers we have ever seen. You come here for a reason. Is it to be entertained or to be a part of something? What brings you to Reader Supported News? What is that worth to you? What will you do?

Marc Ash • Founder, Reader Supported News

Sure, I'll make a donation!

Kremlin Memos Urged Russian Media to Use Tucker Carlson Clips - Report

Martin Pengelly, Guardian UK

Pengelly writes: "The Fox News primetime host Tucker Carlson has been widely accused of echoing Russian propaganda about the invasion of Ukraine."

READ MORE

Over 160 Private Vehicles Leave Mariupol in Humanitarian Corridor Convoy

DPA, Tribune News Service and Agence France-Presse

Excerpt: "A large number of civilians have managed to get out of the besieged Ukrainian city of Mariupol using a humanitarian corridor, the first time in more than a week that such a corridor has been employed successfully and not been disrupted by attacks."

READ MORE

Russia Facing 'Outright Defeat' and 'Sudden' Collapse in Ukraine, Author Says

Ed Mazza, HuffPost

Excerpt: "'The army in the field will reach a point where it can neither be supplied nor withdrawn, and morale will vaporize.'"

READ MORE

Ginni Thomas, Wife of Clarence Thomas, Attended Rally Preceding Capitol Attack

Joan E. Greve, Guardian UK

Greve writes: "In an interview with the Washington Free Beacon, Thomas, a conservative activist who runs a political lobbying firm, said she briefly attended the rally near the White House on 6 January 2021."

READ MORE

Officer Who Shot and Killed 16-Year-Old Ma'Khia Bryant Cleared From Criminal Charges

Kalyn Womack, The Root

Womack writes: "Bryant's family believed there should have been another way to deescalate the situation, reported AP."

READ MORE

Soldiers in Myanmar stand next to military vehicles. (photo: Reuters)

Soldiers in Myanmar stand next to military vehicles. (photo: Reuters)

Witness: Army Attacks in Eastern Myanmar Worst in Decades

Jerry Harmer, Associated Press

Harmer writes: "While Russia's war in Ukraine dominates global attention, Myanmar's military is targeting civilians in air and ground attacks on a scale unmatched in the country since World War II, according to a longtime relief worker who spent almost three months in a combat zone in the Southeast Asian nation."

While Russia's war in Ukraine dominates global attention, Myanmar's military is targeting civilians in air and ground attacks on a scale unmatched in the country since World War II, according to a longtime relief worker who spent almost three months in a combat zone in the Southeast Asian nation.

David Eubank, director of the Free Burma Rangers, a humanitarian relief organization, told The Associated Press that the military’s jets and helicopters stage frequent attacks in the areas of eastern Myanmar where he and his volunteers operate, bringing medical and food aid to civilians caught in conflict.

Ground forces are also firing artillery — indiscriminately, he said — causing thousands to flee their homes.

Video shot by his group’s members includes rare images of repeated air strikes by Myanmar military aircraft in Kayah State – also known as Karenni State — causing a number of civilian deaths.

An analyst for New York-based Human Rights Watch said the air attacks constitute “war crimes.”

Myanmar’s military seized power last year, overthrowing the democratically elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi. After security forces cracked down violently on large, peaceful street demonstrations opposing the takeover, thousands of ordinary people formed militia units, dubbed People’s Defense Forces, to fight back.

Many are loosely allied with well-established ethnic minority armed groups — such as the Karenni, the Karen and the Kachin — that have been fighting the central government for more than half a century, seeking greater autonomy in the frontier regions.

Despite overwhelming superiority in numbers and weaponry, the military has failed to crush this grassroots resistance movement. The army has now stepped up attacks, taking advantage of the dry, summer conditions.

Eubank described the fighting he had seen as probably the worst in Myanmar since World War II, when the country was a British colony still known as Burma and largely occupied by the Japanese.

There has been serious but sporadic fighting in Kachin State in northern Myanmar for a few years, he said, “but what I saw in Karenni I had not seen in Burma before.”

“Air strikes, not like one or two a day like they do in Karen State, but like two MiGs coming one after the other, these Yak fighters, it was one after the other,” said Eubank. “Hind helicopter gunships, these Russian planes, and then just brought hundreds of rounds of 120mm mortar. Just boom, boom, boom, boom.”

Russia is a top arms supplier to Myanmar’s military, keeping up supplies even as many other nations have maintained an embargo since the army’s takeover to promote peace and a return to democratic rule.

Eubank knows whereof he speaks. He was a U.S. Army Special Forces and Ranger officer before he and some ethnic minority leaders from Myanmar founded the faith-based Free Burma Rangers in 1997. Two of its members have been killed in Kayah state since late February: one in an air strike, the other in a mortar barrage.

Drone footage shot by the group shows the impact of the army’s offensive on Karenni settlements, with buildings on fire and smoke drifting thick in the sky. In a Feb. 24 report in the state-run Myanma Alinn Daily newspaper, the military acknowledged using air strikes and heavy artillery in order to clear out what it called “terrorist groups” near the state capital, Loikaw.

As casualties mount, people have to scramble for their lives, cowering in crude underground shelters topped with bamboo. A nighttime air raid on Feb. 23 that struck northwest of Loikaw left two villagers dead, three wounded and several buildings destroyed.

“These are war crimes,” Manny Maung, the Myanmar researcher for Human Rights Watch, told AP. “These attacks by military on civilians, civilian buildings, killings of civilians, public buildings like religious buildings, yes, they are no less than war crimes that are happening right now in that particular area and this is because they are indiscriminately targeting civilians.”

As well as in Kayah, the military is currently hitting hard in Sagaing, in upper central Myanmar, burning villages and heavily engaging with poorly armed militia units.

The United Nations refugee agency says 52,000 people countrywide fled their homes in the last week of February. It puts the total figure of internally displaced since the military takeover at just over half a million. Casualty figures are unclear, given the government's control of information and the remoteness of the war zones.

More than 1,670 civilians have been killed by the security forces since the army seized power in February last year, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, an advocacy group that monitors arrests and deaths. But its tallies are mainly from Myanmar's cities and generally lack casualties from combat in the countryside.

“In the middle of all this we have Ukraine, which is a tragedy, and I’m really grateful for the help the world has galvanized behind Ukraine," Eubank said. “But the Karenni people ask me ‘Don’t we count? ... And of course, the people of Ukraine need help. But so do we. Why? Why isn’t anybody helping us?’”

READ MORE

"Carbon emissions due to tropical deforestation are accelerating, a new study has found." (photo: Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

"Carbon emissions due to tropical deforestation are accelerating, a new study has found." (photo: Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

Tropical Deforestation Emitting Far More Carbon Than Previously Thought: Study

John C. Cannon, Mongabay

Cannon writes: "The rate at which carbon escaped from the deforestation of tropical forests more than doubled in the first two decades of the 21st century, according to new research."

The rate at which carbon escaped from the deforestation of tropical forests more than doubled in the first two decades of the 21st century, according to new research.

Earlier assessments relied primarily on government statistics on the land, which “painted a much different picture,” Paul Elsen, a climate adaptation scientist with the Wildlife Conservation Society and a co-author of the paper, said in an interview. That picture was one in which tropical deforestation is still a serious problem, with each razed hectare of quality forest representing the loss of wildlife habitat, ecosystem services and the ability to continue siphoning carbon from the air. But the calculations of the amount of carbon lost from deforestation around the world suggested the emissions from this major source of atmospheric carbon had stabilized or even started dropping.

At the same time, members of the team had previously documented the worrisome expansion of deforestation into mountainous forests in Southeast Asia. Their analyses showed these higher-elevation forests had a “massive carbon stock,” said lead author Yu Feng, a doctoral student at the Southern University of Science and Technology (SUSTech) in China. They found that the annual figures for the amount of carbon emitted when cleared were “unprecedented,” which they reported in a 2021 study published in the journal Nature Sustainability.

Surprised to find such a little-known source of substantial carbon emissions, the team decided to take a global look at the problem and determine whether these high rates were confined just to Southeast Asia.

To do that, though, they needed a more detailed understanding than that provided by the “bookkeeping” studies used by countries to ballpark forest carbon loss, Elsen said.

“[These studies] don’t locate in space [via satellites] where the forest loss is occurring and how much carbon is there,” he said. Improvements in satellite technology and the monitoring work that remote-sensing scientists such as Matt Hansen and his colleagues are doing at the University of Maryland have put more detailed information at the fingertips of researchers around the world, Elsen added.

“We’re in sort of a golden era of data sets that enables us to look at this very, very precisely,” he said.

The maps and data that Hansen and his team make available can tease apart what has happened to forests since the turn of the century. The data set has a resolution of 30 square meters (323 square feet), making it much “more reliable” than tabulations based on government-gathered statistics, Feng told Mongabay.

Elsen, Feng and their colleagues then used several other maps that plot out forest and soil biomass to estimate the amount of carbon held by the deforested areas mapped by Hansen’s team. The carbon found below the ground — in root systems and the soil, for example — typically takes longer to bleed into the atmosphere after deforestation than the carbon in aboveground sources, such as the trees’ trunks. But the team concluded this discrepancy wouldn’t change the overall trend in the amount of carbon lost, so they bundled the above- and below-ground carbon into a single statistic known as “committed loss.”

The researchers found that the world’s tropical forests emitted nearly 2 billion metric tons of carbon per year between 2015 and 2019, the final five years of the study period. That’s roughly equivalent to the annual emissions of 1,900 coal-fired power plants and more than twice the yearly tabulated forest carbon loss between 2001 and 2005.

The team reported their findings online Feb. 28 in the journal Nature Sustainability.

“It’s definitely concerning that their findings are that there’s a doubling of carbon loss just in two decades,” said Giuseppe Molinario, a geographer with the World Bank who was not involved in the research. Molinario said the study will likely confirm what many researchers suspected — that there’s been “an underestimation of the carbon loss.”

“It would follow that it’s somehow in sync with how much forest cover loss we’re seeing,” he added.

As the team drilled into the data, they uncovered regional patterns in where — and when — forest carbon loss occurred. For example, a lot of the carbon emissions in the early 2000s came from parts of the Brazilian Amazon and the dry forests of the Cerrado. But later on, in the 2010s, those hotspots of carbon loss were deeper in the Amazon and parts of the Congo Basin and those montane jungles in Southeast Asia.

The 20-year data set also revealed that more than two-thirds of the areas cleared for agriculture during the study period remained cleared in 2020.

“That’s a huge amount of area where, once you lose that carbon, you’re not returning it back,” Elsen said. “The fact that the cleared lands are staying cleared and the carbon is gone is definitely problematic.”

Molinario echoed that sentiment. But, he said, that statistic includes everything from forest that had been converted to agriculture nearly for two decades to land that had been cleared just a few years ago.

“What I would like to know is how many of the 2000 to 2005 clearings are still agriculture in 2020,” he added. “I wouldn’t assume that a farmer leaves the field that he just spent a half a year clearing … in just two years.”

Around the world, subsistence farmers employ shifting agriculture, clearing and usually burning the vegetation on a plot of land to prepare it for farming for a year or two. Then, farmers let the field lay fallow, often for years at a time, while moving on to cultivate another plot. The fallow period allows the land to recover and the forest to regrow — if it sits unused by humans for long enough.

But in some parts of the world, such as the Congo Basin, conflict, growing populations, and other pressures appear to have forced a shorter rotational cycle. That change means that forests haven’t been able to return as robustly as they once did. Molinario, who has worked on mapping forest loss in Central Africa, said there’s often more intensive farming with less time for the land to recover near the region’s larger towns, roads, mines and plantations.

“If we want to stop this issue, and we have to help those people living there to find [other ways] to increase their living standards … so they can they can better live with the forest,” said Zhenzhong Zeng, an associate professor and Earth systems scientists at SUSTech and a co-author of the study.

The fact that an area remains cleared of forest may indicate that the agriculture is more “intense” than it once was, said Alan Ziegler, a professor in fisheries and aquatic resources at Thailand’s Mae Jo University and a co-author of the study. In the Amazon and Southeast Asia, that can often mean industrial-scale agriculture or livestock ranching.

Feng said the team’s study serves as a warning that more effort needs to be put into protecting forests. The accelerating forest carbon loss uncovered by the study demonstrates that forest loss has not been reversed or even halted, the authors write. In 2020, the world missed a key deadline to halve rates of deforestation, a key goal of the 2014 New York Declaration on Forests.

This type of evidence also suggests global climate goals may be slipping out of reach, such as the effort to keep global warming under 1.5° Celsius (2.7° Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels. Scientists say a rise of 1.5°C or perhaps 2°C (3.6°F) could lead to dangerous and potentially irreversible impacts as a result of warming, triggered by sea-level rise, increasing drought and intensifying storms. World leaders committed to keeping warming to under 2°C in the 2015 Paris climate change agreement, and they reaffirmed the pledge, along with promised cuts in deforestation by 2030, at the 2021 U.N. climate conference in Glasgow.

Ziegler said the changes at these high-level meetings aren’t translating into action that will address the problem.

“We get together and shake hands, we make a pact, and then it really doesn’t make a change,” he said.

Forests play “a huge role in our ability to fight climate change” because of the massive amount of carbon they emit when they’re degraded or cleared, Elsen said. “This increasing acceleration of forest loss goes right in the face of a lot of the national commitments to help [stop] emissions.”

This study, however, does provide pathways to stem carbon emissions, the authors say, notably through forest protection and restoration.

“We know that just because we’re seeing a lot of deforestation … doesn’t mean that actions can’t be taken to restore healthy forests and restore some of that carbon,” Elsen said. “It does take time, but it is something that we should be investing in.”

This article was originally published on Mongabay.

READ MORE

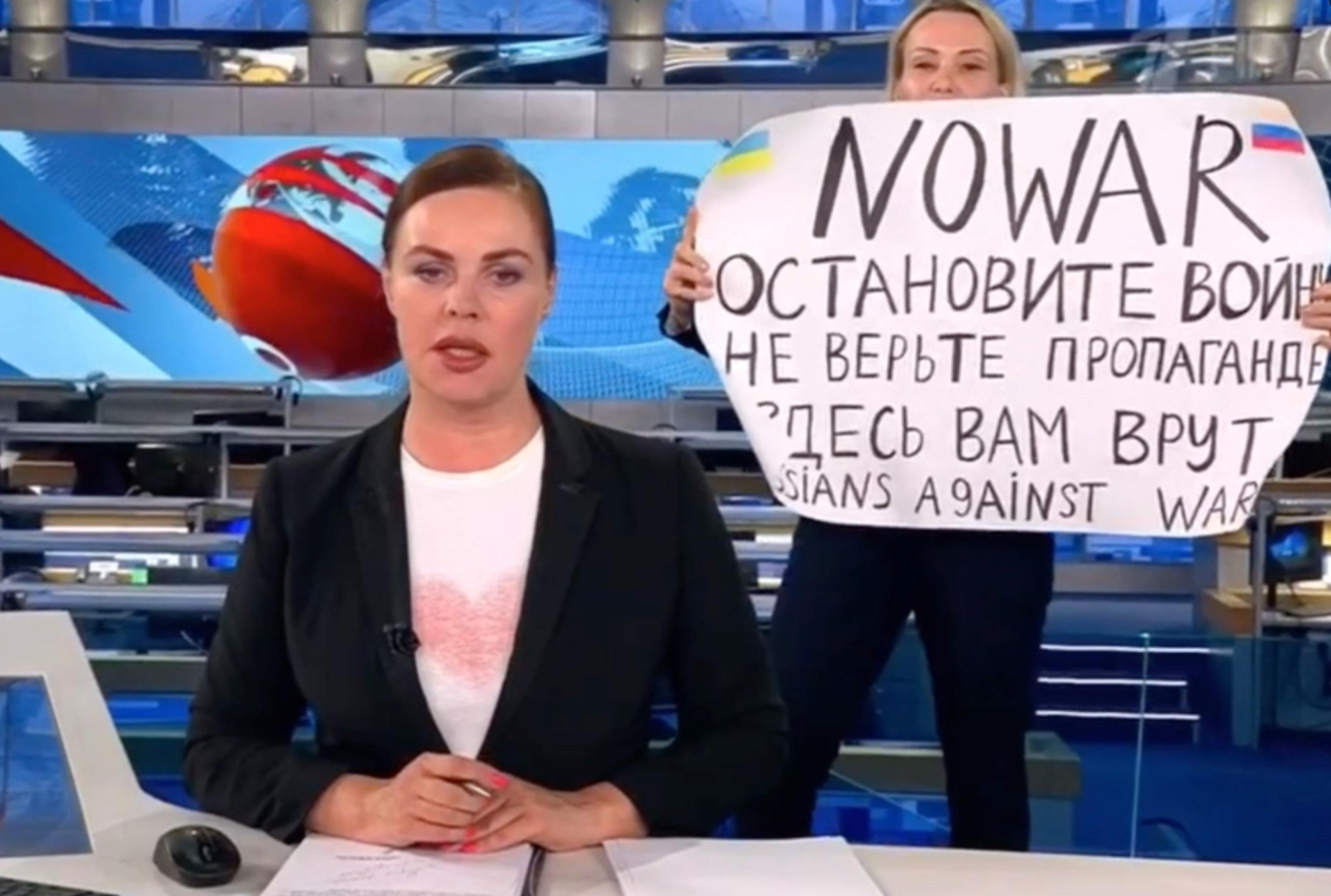

Special Coverage: Ukraine, A Historic Resistance

https://www.rsn.org/001/ukraine-a-historic-resistance.html

Contribute to RSN

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

Update My Monthly Donation

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611