My friend Bernard Avishai sent me this wonderfully thoughtful piece, which he wrote, and which I am sharing with you with his permission.

FOR THE PAST TWO YEARS, at Dartmouth College, I have been co-teaching a course called The Politics of Israel and Palestine with Ezzedine Fishere, a former Egyptian diplomat who served under the United Nations Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process.

Our work in the class—a civil, exploratory dialogue sustained over eighteen sessions—anchored a series of public forums at the college in the aftermath of the horrors of October 7th. These drew several hundred students and faculty into the college halls, and were watched by two thousand more online; they proved sufficiently helpful in preëmpting the polarization that has afflicted other Ivy League campuses to gain the attention of various national media. I spend half the year in Israel, and have since returned to a country at war. I’ve been thinking more about our miniature peace process, about how a university might organize for difficult subjects—and about what, after all, universities are.

Ezzedine and I had been teaching versions of our course separately; I started in 2011, he in 2016. We had a mutual friend in Álvaro de Soto, the former U.N. Special Coordinator under whom he served, and Ezzedine did his doctorate in Montreal, my home town, so our relations were warm from the start. But it was only after the eleven-day Gaza conflict in May, 2021, when I returned to campus from Jerusalem, that we determined that we would team up.

The catalyst was a statement put out by some faculty members who had organized into the Consortium of Studies in Race, Migration, and Sexuality, or R.M.S. Their statement was in solidarity with Gazans but was infused with viscous rhetoric (“For RMS, this means ensuring that our shared epistemologies and ethics of anticolonial relations are capacious”) and seemed rather hypothetical about attitudes toward sexuality in Gaza under Hamas rule; it also called for “supporting Jewish scholars who have vowed that their future teaching of the Holocaust will be in dialogue with the Naqba, Black scholars who have put Ferguson next to Gaza,” and similar notions in this vein.

Ezzedine and I feared that this statement would prompt a counter-statement from other faculty members who might accuse pro-Palestinian activists of antisemitism. “If this became a thing,” Ezzedine recalled recently, “it would have undermined the spirit in which we’d been operating.”

HE WAS REFERRING TO EFFORTS BE THE HEAD OF DARTMOUTH’S JEWISH-STUDIES PROGRAM, Susannah Heschel, and the head of the Middle East-studies program, Tarek El-Ariss, to organize curricula coöperatively, aligning and cross-listing courses and including the faculty of both programs in seminars.

Dartmouth is isolated and nested in an almost unnervingly lovely New Hampshire river valley, so faculty tend to think that friendships derive from shared academic interests and that, even when those interests might lead to disagreement, the friendships should not be fouled by intemperance. The government-and-economics department had already sponsored a course called The Future of Capitalism, team-taught by colleagues whose views range from social-democratic to laissez-faire. The dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, the biologist Elizabeth Smith, allocated special funds to support Ezzedine’s and my proposal based on a single e-mail to her.

Whatever the catalyst, joint teaching immediately felt like a relief to both of us. There were moments when I had felt queasy purporting to represent the evolution of Palestinian nationalism, or the influence of Nasserism, the state socialism of Egypt’s second President, Gamal Abdel Nasser.

I did not doubt my sources, or even my general claims, but I worried that they would land with some students as unreliable. Ezzedine felt much the same teaching about current Israeli political divisions. “I thought, and still think,” he told me, “that having both an Israeli and an Arab would offer students more safety to be open-minded—would reduce the likelihood of them shutting themselves down when they hear something they don’t like.”

I had publicly asked foundational questions about my own, well, side, and Ezzedine had raised corresponding questions about his. We hoped our students would find the symmetry stimulating. In past years, I had assigned parts of my 1985 book, “The Tragedy of Zionism,” in which I ask whether Israel’s democracy was fettered not only by the occupation of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, since 1967, but also by residual Zionist and theocratic institutions, since 1948.

I decided to continue to assign the book and various other articles about, say, the prospects for a two-state confederation, or the economic impact of occupation. Ezzedine, more scrupulous than I was in separating the roles of teacher and analyst, assigned none of his own political writings (he’d contributed regularly to the Washington Post), yet he was equally frank about his political journey: after leaving the diplomatic world, he had become a liberal columnist in Egypt, and had participated in the Tahrir uprising, which, in 2011, ended the thirty-year rule of Hosni Mubarak. Mohamed Morsi, of the Muslim Brotherhood, briefly replaced Mubarak, until he, too, was toppled by Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, who proved no more respectful of human rights.

Ezzedine came to New Hampshire, in 2016, feeling the years of frustration. “You would talk about the horrors of living under occupation, and I about my consternation about Arab dictatorships,” he said, recalling this point of collaboration. “When students see us voicing criticism to the communities we identify with, it encourages them to adopt a more critical view of their own community.”

Yet the prospect of merging our courses excited me for a kind of parochial reason, as well—the converse of the reason for my past queasiness. I would be able to teach Zionist origins to students I might not otherwise have reached, and in a way that Arab-studies scholars without a command of the Hebrew language likely would not.

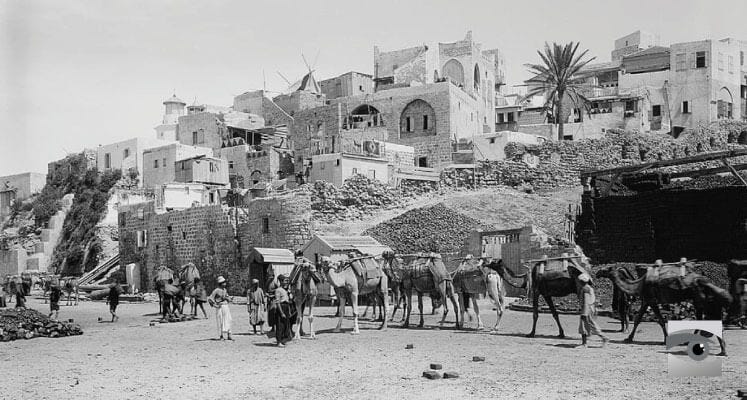

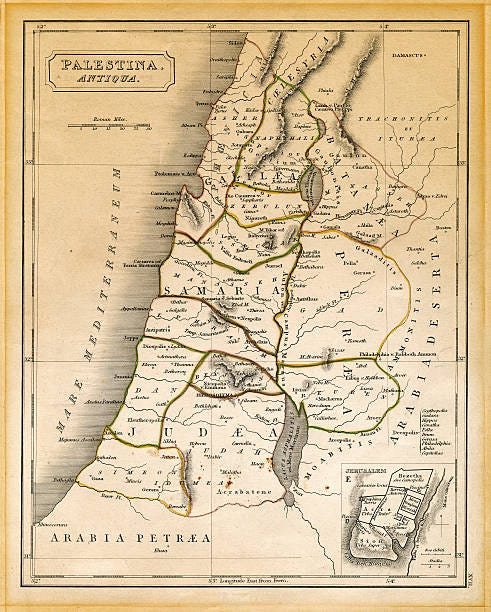

In most standard accounts of that history, in the late nineteenth century Jews needed refuge from persecution, so they became determined to build a state in their Biblical land. A book we assigned, the late Ian Black’s “Enemies and Neighbors: Arabs and Jews in Palestine and Israel, 1917-2017,” put the Zionist narrative this way: as a “quest” to build a “sovereign and independent Jewish state in their ancient homeland, finally achieved in the wake of the extermination of 6 million Jews by the Nazis.”

But this was not the idea that brought the original Zionist pioneers to the land in the early decades of the twentieth century—most Jews seeking safety then went to the U.S.—or that explained how, though Hebrew was nobody’s mother tongue at the time, Israel became a Hebrew-speaking country that had, indeed, a “politics,” a multigenerational culture war pitting liberals against theocrats.

IN FACT, ZIONIST PIONEERS, the precursors of Israel’s liberals, were secular modernizers who were appalled by the rabbinic strictures that alienated Jews in Eastern European cities. They wanted to reëstablish Hebrew as not just a language of scholastic debate and liturgical ritual but the means by which Jews might preserve the materials of the traditional culture yet cultivate their individual scientific and aesthetic imaginations in a new, emancipated Jewish nation. This would be something which diaspora Jews, assimilated into the English or German language and culture, could not aspire to.

Zionism, in short, was a labor of love before it became a defensive crouch. The standard version is the projection onto the past from Zionism’s post-Second World War dilemmas and self-justifying rhetoric.

Crucially, Ezzedine and I agreed to complement, if not challenge, each other’s teaching on the topics that we knew best. He would present the evolution of Palestinian national consciousness with nuances and affections that would have escaped me, lacking Arabic. I would show how in the early nineteen-twenties—when the Jewish National Fund bought land for Zionist farming collectives, often from absentee landlords in Beirut and other cities—pioneers reasoned that the resulting displacement of indebted Palestinian leasehold farmers seemed an inevitable price, similar to what was happening at the time to poor farmers in every modernizing economy, including the United States.

We assigned, as if in response, large portions of Rashid Khalidi’s “Palestinian Identity” and “The Iron Cage.” And Ezzedine would show that the Naqba of 1948 was the culmination of a colonial project that had thwarted Palestinian leaders ever since Britain betrayed them by carving Palestine out of the promised pan-Arab country, and also with the Balfour Declaration, of 1917, which committed to a “national home” for Jews. Palestinian identity was a mounting grievance against Zionist incursion and imperial fiat—an interrupted, frustrated modernizing project in its own right.

Finally, we realized that such competing narratives required a Socratic atmosphere. We met for two hours, twice a week, and for every class there were readings or films assigned, as well as questions to guide discovery. (“What was the ‘Jewish problem’ in 1881—physical and ideological—and how did the two major streams of Zionism define this problem and aim to solve it?”; “What were the roots of the 1936 revolt? How did it affect Palestinian national movement—both in the short and long terms? Was there a different path open to the Palestinians?”) By turns, one of us lectured for the first hour, and the other served as commentator during the class discussion for the second.

We wanted students coming in having already raised preliminary questions, however, so we split them into five study groups that posted a comment about each assignment on the course Web site. (One group, working through competing claims, posted, “A huge focus by the cultural Zionist leaders at the time was to propagate a predominantly Hebrew speaking state. One of the ways this would be done is by pushing out Arab labor which was mostly turning Jews into Arab speakers defeating the purpose of creating a Hebrew culture.”) We conducted written exams by distributing various questions in advance and, on the day of the test, pulling one from a hat that everyone answered. The key was to insure some give-and-take before students were called to defend an opinion.

.

EZZEDINE WROTE ME RECENTLY, with his usual cordiality, that he was never quite convinced that my “take on cultural Zionism” explained enough. And we disagreed on how long to dwell on the formation of national narratives and how quickly to get to the present. He wanted to devote whole classes to subjects that he felt, from casual conversations with students, were on their minds: Was Israel an apartheid state? Was terrorism not just freedom fighting? I resisted at first, concerned at how such epithets would encourage stereotypical views, but he proved more prescient.

Students found the pieces of truth that the epithets obscured outweighed the pieces they exposed. “The mission of faculty is to coach students how to learn, not tell them what to think,” Ezzedine wrote, “so we needed a more emancipated understanding of the ‘political’—a suspecting approach, not an orthodoxy of radical thought.”

Yet our disagreements paled beside the big thing we agreed on, which is that the conflict should be approached with a sense of tragedy. I mean this pedantically. Our job was to construct as best we could Israelis’ and Palestinians’ evolving narratives. But it was also to present the acolytes of national narratives as inevitably tragic figures, limited by perception, experience, idiosyncrasy, fear, ambition, narcissism—hubris.

Students pressed us on the long-term implications of some historical events (say, the 1939 White Paper, with which the British severely restricted Jewish immigration) that most were encountering for the first time. Ezzedine turned the crystal one way, I another. In time, a kind of ironic distance settled on us, and students, too, began poking at the myopia and the hypocrisies of various leaders. People get things wrong, and that’s “living,” as Philip Roth put it, in “American Pastoral”: “getting them wrong and wrong and wrong and then, on careful reconsideration, getting them wrong again.”

So we began the course by urging students to reckon how the people we studied could not have known all the consequences of their actions, and certainly not as we know them, looking back. We ought not to project onto either Israelis or Palestinians some implicit ideological commitment owing to the way things turned out: given Israel’s current hold on the occupied territories, one should not assume that all Zionists, deep down, must have wanted the whole land for the Jews, nor that all Palestinians, given that Hamas won the 2006 election for the Palestinian legislature, must have all along harbored a desire for an Islamist state.

Rather, students might try to put themselves in the minds of people in their time and place. “For protracted conflicts like the Arab-Israeli one,” Ezzedine reflected, “blame is a waste of time. The key is to understand, not justify, why people behave the way they do—their motivations, concerns and world views—to understand the complexity of this conflict and its tragic nature.”

Not coincidentally, this sense of tragedy seemed to us of a piece with the principles of a liberal commonwealth to which the modern university is a tribute. It is because of our “wrongness” that universities must foster tolerance, not just as an act of magnanimity but as institutional architecture, as a protected way of life: individual freedoms, rules of debate, rules of evidence, and so forth. An open society sees truth as process and method—more verb than noun.

But here is where the university ought to know limits. Ezzedine and I never pressed the point in class (our exchanges seldom became quite that pedantic), but the course did model the restraints entailed by institutional tolerance: the patience to hear criticism, the demand that opinions be informed, the care to let others finish their sentences.

These norms, of an open society, seemed especially urgent to convey in a class about places where individual freedoms are routinely subordinated to religious or tribal solidarity. Strident defenders of Israel and Palestine both accuse the other side of genocide while also questioning that side’s right to exist. This kind of language can defeat a university—and a democracy. An institution committed to tolerance has no obligation to tolerate intolerant people; an open society will close off threats to the terms of debate themselves.

At the end of the course, one student—a Palestinian woman who had often appeared to signal impatience when it was my turn to lecture—asked for an appointment. We spoke for an hour and a half. She told me in the end that, although the class did not change her mind about various injustices, her “life had become a discussion.” I called Ezzedine to tell him what she had said. In a cruel time, a moment of grace.