Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Some are said to be fleeing the country, while others reportedly came extremely close to ousting him this week.

A human rights group that works closely with Russian inmates and investigates abuses by the security services has reportedly received a flood of calls from members of those same security services desperately trying to flee.

Gulagu.net, founded by Vladimir Osechkin, reports that the final straw appears to have been the brutal sledgehammer-execution video released by Russia’s private army last week—a stomach-churning extrajudicial killing that the Kremlin politely averted its eyes from while the Putin-linked businessman thought to be behind it uses it for his own PR campaign.

“The reprisal with the use of a sledgehammer and the cruelty of [Wagner Group founder Yevgeny] Prigozhin, with the tacit consent of Putin, had an unexpected effect: for the third day, there is a steady stream of messages to the Gulagu.net hotline from employees of the Interior Ministry, the [Investigative Committee], the FSB and the [Federal Protective Service], the Federal Bailiff Service, etc., who want to leave the territory of lawlessness and cruelty,” Gulagu.net reported.

While rumblings of discontent among the Russian security services have been reported throughout the war, frustrations have reportedly boiled over as Putin is increasingly seen as losing all control.

In less than two weeks, there was Russia’s humiliating retreat from Kherson—the Ukrainian territory that Putin and so many of his mouthpieces had vowed would be part of Russia “forever.” Then came the brutal execution video by members of the Wagner Group, the same private army that, by all accounts, has been entrusted with bringing victory to Putin by any means necessary.

(Despite mounting calls for an investigation into the execution, the Kremlin has dismissed it as “not our business,” leaving it to Wagner Group overlord Yevgeny Prigozhin to offer a flurry of fantastical explanations for the murder clearly aimed at trolling.)

And then came the Russian-made missile that landed in Poland this week, killing two farmers there shortly after similar missiles fired by Russia cut down Ukrainian civilians in the latest bombardment. While Western officials have since walked back their claims that the Polish farmers were killed by a missile fired by Russia, the incident initially seemed likely to trigger a direct confrontation between Russia’s military and NATO forces.

And that reportedly left some within the Russian security services so shaken they were prepared to remove Putin from power entirely.

That’s according to unconfirmed reporting by the Telegram channel General SVR, an anonymous channel that claims to be run by a former member of the security services.

“The incident with a missile hitting Poland on Tuesday almost became a prologue to the seizure of power in Russia,” the channel reported Thursday, claiming that high-ranking security officials had gathered in the immediate aftermath of the strike for “informal consultations.”

“Knowing Putin's penchant for raising the stakes through escalation… this group of security officials quickly became convinced that in response to a Russian strike on a country included in NATO there could be both a retaliatory strike and an ultimatum.”

So, according to the channel, they decided that “if the U.S. leadership and the adjoining countries show readiness for a harsh response, then the best way out would be to remove the current Russian president, Vladimir Putin, from power and create a collegial council of security officials to ‘temporarily’ take control of the country into their own hands … blaming all the problems on either a seriously ill or law-breaking president.”

Noting that Putin has brought tension “to almost the limit,” the channel warned: “This time, the critical situation turned out to be illusory and it made no sense for the security forces to take risks, but next time, and there will be a next time, Putin may not have a chance.”

While panic over the missile incident has largely fizzled out, the same cannot be said for Prigozhin’s growing influence in the war and role in the spotlight. A former member of the security services who fled the country told Deutsche Welle late last month that concerns were growing inside federal agencies about the power given to some figures within Putin’s inner circle.

“The state is not thinking about its people, it’s only thinking about itself and its close associates,” she said, describing them as “gangsters.”

Perhaps in a sign of things to come, Putin on Thursday seemed to signal he has no plans to listen to any of the more moderate figures who might caution him against escalation. Instead, he purged the Kremlin’s Human Rights Council of all the experts who raised questions about the war and the public execution of defector Yevgeny Nuzhin, replacing them with a hardliner war reporter and other Kremlin loyalists.

According to RTVI, citing a source in the human rights council, the head of the council is unlikely to seek an investigation into the sledgehammer killing or get involved in any way because he said that in times of war “anything can happen.”

READ MORE Russian soldiers. (photo: Creative Commons)

Russian soldiers. (photo: Creative Commons)

Residents and workers say occupying forces used site to burn bodies of fallen Russian soldiers

As the Russian occupation of the region was on its last legs over the summer, the site, once a mundane place where residents disposed of their rubbish, became a no-go area, according to Kherson’s inhabitants, fiercely sealed off by the invading forces from presumed prying eyes.

The reason for the jittery secrecy, several residents and workers at the site told the Guardian, was that the occupying forces had a gruesome new purpose there: dumping the bodies of their fallen brethren, and then burning them.

The residents report seeing Russian open trucks arriving to the site carrying black bags that were then set on fire, filling the air with a large cloud of smoke and a terrifying stench of burning flesh.

They believe the Russians were disposing of the bodies of its soldiers killed during the heavy fighting of those summer days.

“Every time our army shelled the Russians there, they moved the remains to the landfill and burned them,” says Iryna, 40, a Kherson resident.

Ukraine’s attempts to gain momentum and retake the southern city began at the end of June when long-awaited US-made Himars long-range rockets finally reached one the frontlines there. Kyiv was making good use of them to badly damage bridges across the Dnipro, destroy Russian ammunition dumps and strike enemy artillery and forces.

It was around this time, the residents said, that they first started to fear a new use for the site.

It is not possible to independently verify the claims, and Ukrainian authorities said they could not comment on whether the allegations were being investigated. The Guardian visited the landfill, located on the north-western outskirts of the town, five days after Kherson’s liberation and spoke to employees of the site as well as several more of the town’s residents, who backed up the claims made by others in the summer.

“The Russians drove a Kamaz full of rubbish and corpses all together and unloaded,” said a rubbish collector from Kherson who asked not to be named. “Do you think someone was gonna bury them? They dumped them and then dumped the trash over them, and that’s it.”

He said he did not see if bodies belonged to soldiers or civilians. “I didn’t see. I’ve said enough. I’m not scared, I’ve been fighting this war since 2014. Been to Donbas.

“But the less you know, the better you sleep,” he added, citing a Ukrainian saying. Fear is still alive among the residents who lived for eight months under a police state, in which the Russian authorities did not tolerate the slightest hint of dissent. The price was arrest, or worse: death.

Svitlana Viktorivna, 45, who together with her husband, Oleksandr, has been bringing waste to the landfill for years in their truck, said a Russian checkpoint had been set up at its entrance.

“We were not allowed anywhere near the area of the landfill where they were burning the bodies,” she says. “So let me tell you how it was: they came here, they left some of their soldier-guards, and unloaded and burned. One day my husband and I arrived at the wrong time. We came here while they were doing their ‘business’ and they gave my husband a hard blow in the face with a club.”

“I didn’t see the remains,” she adds. “They buried whatever was left.”

Russia’s defence minister, Sergei Shoigu, has said that nearly 6,000 soldiers have died in Ukraine, but the Pentagon in late summer estimated that about 80,000 Russian soldiers had been killed or injured.

The workers at the landfill said the Russians had chosen an area on the most isolated side of the landfill. For security reasons, it is not possible to visit. A truck driver working in the landfill said he did not rule out that the Russians may have mined the area or left unexploded devices.

“I heard the story, but I didn’t go that far with my truck to unload rubbish. But I can guarantee you that, whatever they were doing, it smelled so bad, like [rotten] meat” says the truck driver. “And the smoke … the smoke was thick.”

Residents of a large Soviet-era apartment block facing the landfill said that when the Russians had started burning, a large cloud of smoke had risen up filling the air with an unbearable smell of decay, to the point that it had felt impossible to breathe.

“I felt nauseous when I smelled that smoke,” says Olesia Kokorina, 60, who lives on the eighth floor. “And it was scary, too, because it smelled like burnt hair, and you know, it also smelled like at the dentist’s when they drill your tooth before placing a filling. And the smoke was so thick, you couldn’t see the building next door.”

“It just never smelled like this before,” says Natalia, 65. “There were lots of dump trucks and they were all covered with bags. I don’t know what was in them, but the stench from the smoke in the landfill was so bad we couldn’t even open the balcony door. There were days when you couldn’t breathe because of the smell.”

Some believe that burning bodies of their own soldiers was the easiest way to get rid of the corpses as bridges over the Dnipro River when Russians were virtually cut off on its western bank were too fragile to hold trucks.

Dozens of other Kherson residents corroborated the reports of their neighbours, but Ukrainian authorities have not so far spoken. A local official who requested anonymity said: “We are not interested in the burial sites of the enemy. What interests us is to find the bodies of Ukrainians, tortured, killed and buried in mass graves here in the Kherson region.”

Ukraine’s security service believe the bodies of thousands of dead Russian soldiers are being informally disposed of as the Kremlin is logging them as “missing in action” in an attempt to cover up its losses in the war in Ukraine.

An intercepted phone call from a Russian soldier in May said that his comrades had been buried in “a dump the height of a man” just outside occupied Donetsk. “There’s so much Cargo 200 [military code for dead soldiers] that the mountains of corpses are 2 metres high,” he said in the call. “It’s not a morgue, it’s a dump. It’s massive.”

“They just toss them there,” a Russian soldier said in another intercepted call. “And then later it’s easier to make it as if they disappeared without a trace. It’s easier for them to pretend they are just missing, and that’s it.”

READ MORE "The government's audits uncovered about $12 million in net overpayments for the care of 18,090 patients sampled." (image: Eric Harkleroad/KHN/Getty Images/Unsplash/Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Data)

"The government's audits uncovered about $12 million in net overpayments for the care of 18,090 patients sampled." (image: Eric Harkleroad/KHN/Getty Images/Unsplash/Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Data)

Summaries of the 90 audits, which examined billings from 2011 through 2013 and are the most recent reviews completed, were obtained exclusively by KHN through a three-year Freedom of Information Act lawsuit, which was settled in late September.

The government's audits uncovered about $12 million in net overpayments for the care of 18,090 patients sampled, though the actual losses to taxpayers are likely much higher. Medicare Advantage, a fast-growing alternative to original Medicare, is run primarily by major insurance companies.

Officials at the Centers for Medicare … Medicaid Services have said they intend to extrapolate the payment error rates from those samples across the total membership of each plan — and recoup an estimated $650 million from insurers as a result.

But after nearly a decade, that has yet to happen. CMS was set to unveil a final extrapolation rule Nov. 1 but recently put that decision off until February.

Ted Doolittle, a former deputy director of CMS' Center for Program Integrity, which oversees Medicare's efforts to fight fraud and billing abuse, said the agency has failed to hold Medicare Advantage plans accountable. "I think CMS fell down on the job on this," said Doolittle, now the health care advocate for the state of Connecticut.

Doolittle said CMS appears to be "carrying water" for the insurance industry, which is "making money hand over fist" off Medicare Advantage plans. "From the outside, it seems pretty smelly," he said.

In an email response to written questions posed by KHN, Dara Corrigan, a CMS deputy administrator, said the agency hasn't told health plans how much they owe because the calculations "have not been finalized."

Corrigan declined to say when the agency would finish its work. "We have a fiduciary and statutory duty to address improper payments in all of our programs," she said.

Enrollment in Medicare Advantage plans has more than doubled in the last decade

The 90 audits are the only ones CMS has completed over the past decade, a time when Medicare Advantage has grown explosively. Enrollment in the plans more than doubled during that period, passing 28 million in 2022, at a cost to the government of $427 billion.

Seventy-one of the 90 audits uncovered net overpayments, which topped $1,000 per patient on average in 23 audits, according to the government's records. Humana, one of the largest Medicare Advantage sponsors, had overpayments exceeding that $1,000 average in 10 of 11 audits, according to the records.

CMS paid the remaining plans too little on average, anywhere from $8 to $773 per patient.

What constitutes an overpayment?

Auditors flag overpayments when a patient's records fail to document that the person had the medical condition the government paid the health plan to treat, or if medical reviewers judge the illness is less severe than claimed.

That happened on average for just over 20% of medical conditions examined over the three-year period; rates of unconfirmed diseases were higher in some plans.

As Medicare Advantage's popularity among seniors has grown, CMS has fought to keep its audit procedures, and the mounting losses to the government, largely under wraps.

That approach has frustrated both the industry, which has blasted the audit process as "fatally flawed" and hopes to torpedo it, and Medicare advocates, who worry some insurers are getting away with ripping off the government.

"At the end of the day, it's taxpayer dollars that were spent," said David Lipschutz, a senior policy attorney with the Center for Medicare Advocacy. "The public deserves more information about that."

At least three parties, including KHN, have sued CMS under the Freedom of Information Act to shake loose details about the overpayment audits, which CMS calls Risk Adjustment Data Validation, or RADV.

KHN sued CMS in September 2019 after the agency failed to respond to a FOIA request for the audits. Under the settlement, CMS agreed to hand over the audit summaries and other documents and pay $63,000 in legal fees to Davis Wright Tremaine, the law firm that represented KHN. CMS did not admit to wrongfully withholding the records.

Some insurers often claimed patients were sicker than average, without proper evidence

Most of the audited plans fell into what CMS calls a "high coding intensity group." That means they were among the most aggressive in seeking extra payments for patients they claimed were sicker than average. The government pays the health plans using a formula called a "risk score" that is supposed to render higher rates for sicker patients and lower ones for healthier ones.

But often medical records supplied by the health plans failed to support those claims. Unsupported conditions ranged from diabetes to congestive heart failure.

Overall, average overpayments to health plans ranged from a low of $10 to a high of $5,888 per patient collected by Touchstone Health HMO, a New York health plan whose contract was terminated "by mutual consent" in 2015, according to CMS records.

Two big insurers that overcharged Medicare, according to audits: United Healthcare and Humana

Most of the audited health plans had 10,000 members or more, which sharply boosts the overpayment amount when the rates are extrapolated. UnitedHealthcare and Humana, the two biggest Medicare Advantage insurers, accounted for 26 of the 90 contract audits over the three years.

In all, the 90 audits found plans that received $22.5 million in overpayments, though these were offset by underpayments of $10.5 million.

Auditors scrutinize 30 contracts a year, a small sample of about 1,000 Medicare Advantage contracts nationwide.

Eight audits of UnitedHealthcare plans found overpayments, while seven others found the government had underpaid.

UnitedHealthcare spokesperson Heather Soule said the company welcomes "the program oversight that RADV audits provide." But she said the audit process needs to compare Medicare Advantage to original Medicare to provide a "complete picture" of overpayments. "Three years ago we made a recommendation to CMS suggesting that they conduct RADV audits on every plan, every year," Soule said.

Humana's 11 audits with overpayments included plans in Florida and Puerto Rico that CMS had audited twice in three years.

The Florida Humana plan also was the target of an unrelated audit in April 2021 by the Health and Human Services inspector general. That audit, which covered billings in 2015, concluded Humana improperly collected nearly $200 million that year by overstating how sick some patients in its Medicare Advantage plans were. Officials have yet to recoup any of that money, either.

In an email, Humana spokesperson Jahna Lindsay-Jones called the CMS audit findings "preliminary" and noted they were based on a sampling of years-old claims.

"While we continue to have substantive concerns with how CMS audits are conducted, Humana remains committed to working closely with regulators to improve the Medicare Advantage program in ways that increase seniors' access to high-quality, lower cost care," she wrote.

A billing showdown looms

Results of the 90 audits, though years old, mirror more recent findings of a slew of other government reports and whistleblower lawsuits — many released over the past year — alleging that Medicare Advantage plans routinely have inflated patient risk scores to overcharge the government by billions of dollars.

Brian Murphy, an expert in medical record documentation, said collectively the reviews show that the problem continues to be "absolutely endemic" in the industry.

Auditors are finding the same inflated charges "over and over again," he said, adding: "I don't think there is enough oversight."

When it comes to getting money back from the health plans, extrapolation is the big sticking point.

Although extrapolation is routinely used as a tool in most Medicare audits, CMS officials have never applied it to Medicare Advantage audits because of fierce opposition from the insurance industry.

"While this data is more than a decade old, more recent research demonstrates Medicare Advantage's affordability and responsible stewardship of Medicare dollars," said Mary Beth Donahue, president of the Better Medicare Alliance, a group that advocates for Medicare Advantage. She said the industry "delivers better care and better outcomes" for patients.

But critics argue that CMS audits only a tiny percentage of Medicare Advantage contracts nationwide and should do more to protect tax dollars.

Doolittle, the former CMS official, said the agency needs to "start keeping up with the times and doing these audits on an annual basis and extrapolating the results."

But Kathy Poppitt, a Texas health care attorney, questioned the fairness of demanding huge refunds from insurers so many years later. "The health plans are going to fight tooth and nail and not make this easy for CMS," she said.

READ MORE Wild bison. (photo: Joel Sartore/National Geographic)

Wild bison. (photo: Joel Sartore/National Geographic)

Descendants of bison that once roamed North America's Great Plains by the tens of millions, the animals would soon thunder up a chute, take a truck ride across South Dakota and join one of many burgeoning herds Heinert has helped reestablish on Native American lands.

Heinert nodded in satisfaction to a park service employee as the animals stomped their hooves and kicked up dust in the cold wind. He took a brief call from Iowa about another herd being transferred to tribes in Minnesota and Oklahoma, then spoke with a fellow trucker about yet more bison destined for Wisconsin.

By nightfall, the last of the American buffalo shipped from Badlands were being unloaded at the Rosebud reservation, where Heinert lives. The next day, he was on the road back to Badlands to load 200 bison for another tribe, the Cheyenne River Sioux.

Most bison in North America are in commercial herds, treated no differently than cattle.

“Buffalo, they walk in two worlds,” Heinert said. ”Are they commercial or are they wildlife? From the tribal perspective, we've always deemed them as wildlife, or to take it a step further, as a relative.”

Some 82 tribes across the U.S. — from New York to Alaska — now have more than 20,000 bison in 65 herds — and that’s been growing in recent years along with the desire among Native Americans to reclaim stewardship of an animal their ancestors lived alongside and depended upon for millennia.

European settlers destroyed that balance when they slaughtered the great herds. Bison almost went extinct until conservationists including Teddy Roosevelt intervened to reestablish a small number of herds largely on federal lands. Native Americans were sometimes excluded from those early efforts carried out by conservation groups.

Such groups more recently partnered with tribes, and some are now stepping aside. The long-term dream for some Native Americans: return bison on a scale rivaling herds that roamed the continent in numbers that shaped the landscape itself.

Heinert, 50, a South Dakota state senator and director of the InterTribal Buffalo Council, views his job in practical terms: Get bison to tribes that want them, whether two animals or 200. He helps them rekindle long-neglected cultural connections, increase food security, reclaim sovereignty and improve land management. This fall, Heinert's group has moved 2,041 bison to 22 tribes in 10 states.

“All of these tribes relied on them at some point, whether that was for food or shelter or ceremonies. The stories that come from those tribes are unique to those tribes,” he said. “Those tribes are trying to go back to that, reestablishing that connection that was once there and was once very strong.”

HERDS SLAUGHTERED

Bison for centuries set rhythms of life for the Lakota Sioux and many other nomadic tribes that followed their annual migrations. Hides for clothing and teepees, bones for tools and weapons, horns for ladles, hair for rope — a steady supply of bison was fundamental.

At so-called “buffalo jumps,” herds would be run off cliffs, then butchered over days and weeks. Archaeologists have found immense volumes of bones buried at some sites, suggesting processing on a major scale.

European settlers and firearms brought a new level of industry to the enterprise as hunters, U.S. troops and tourists shot bison and a growing commercial market used their parts in machinery, fertilizer and clothing. By 1889, few bison remained: 10 animals in central Montana, 20 each in central Colorado and southern Wyoming, 200 in Yellowstone National Park, some 550 in northern Alberta and about 250 in zoos and private herds.

Piles of buffalo skulls seen in haunting photos from that era illustrate an ecological and cultural disaster.

“We wanted to populate the western half of the United States because there were so many people in the East,” U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American cabinet member, said in an interview. “They wanted all of the Indians dead so they could take their land away.”

The thinking at the time, she added, was “‘if we kill off the buffalo, the Indians will die. They won’t have anything to eat.’”

HARVESTING A BULL

The day after the bison transfer from the Badlands, Heinert's son T.J. sprawled flat on the ground, his rifle scope fixed on a large bull bison at the Wolakota Buffalo Range. The tribal enterprise in just two years has restored about 1,000 bison to 28,000 acres (11,300 hectares) of rolling, scrub-covered hills near the Nebraska-South Dakota border.

Pausing to pull a cactus paddle from the back of his hand, Heinert looked back through the scope. The 28-year-old had been talking all morning about the need for a perfect shot and the difficulty in 40-mile (64-kilometer) an hour winds. The first bullet went into the animal's ear, but it lumbered away a couple hundred yards to join a larger group of bison, with the hunter following in an all-terrain vehicle.

Two more shots, then after the animal finally went down, Heinert drove up close and put the rifle behind its ear for a final shot that stopped its thrashing. “Definitely not how it's supposed to go,” Heinert kept repeating, disappointed it wasn't an instant kill. “But we got him down. That's all that matters at this point."

BUFFALO DREAMS

Coinciding with widespread extermination of bison, tribes such as the Lakota were robbed of land through broken treaties that by 1889 whittled down the “Great Sioux Reservation” established in 1851 to several much smaller ones across the Dakotas. Without bison, tribal members relied on government “beef stations” that distributed meat from cattle ranches.

The program was a boon for white ranchers. Today, Cherry County, Nebraska — along Rosebud reservation’s southern border — boasts more cattle than any other U.S. county.

Removing fences that crisscross ranches there and opening them to bison is unlikely, but Rosebud Sioux are intent on expanding the reservation's herds as a reliable food source.

Others have grander visions: The Blackfeet of Montana and tribes in Alberta want to establish a “transboundary herd” ranging over the Canada border near Glacier National Park. Other tribes propose a “buffalo commons” on federal lands in central Montana where the region's tribes could harvest animals.

“What would it look like to have 30 million buffalo in North America again?” said Cristina Mormorunni, a Métis Indian who's worked with the Blackfeet to restore bison.

With so many people, houses and fences now, Haaland said there's no going back completely. But her agency has emerged as a primary bison source, transferring more than 20,000 to tribes and tribal organizations over 20 years, typically to thin government-controlled herds so they don't outgrow their land.

“It’s wonderful tribes are working together on something as important as bison, that were almost lost,” Haaland said.

Transfers sometimes draw objections from cattle ranchers who worry bison carry disease and compete for grass. Such fears long inhibited efforts to transfer Yellowstone National Park bison.

Interior officials work with state officials make sure relocated bison meet local veterinary health requirements. But they generally don't vaccinate the animals and handle them as little as possible.

Bison demand from the tribes is growing, and Haaland said transfers will continue. That includes up to 1,000 being trucked this year from Badlands, Grand Canyon National Park and several national wildlife refuges. Others come from conservation groups and tribes that share surplus bison.

“WAY OF LIFE"

Back at Wolakota range, Daniel Eagle Road approached the bison shot by T.J. Heinert. Eagle Road rested a hand on the animal's head. Heinert got out some chewing tobacco, tucked some behind his lip and passed the tin to Eagle Road who did the same. Heinert sprinkled tobacco along the bison's back and prayed.

Chains fastened around the front and hind legs, the half-ton animal was hoisted onto a flatbed truck for the bouncy ride to ranch headquarters. About 20 adults and children gathered as the bison was lowered onto a tarp, then listened solemnly to tribal elder Duane Hollow Horn Bear.

“This relative gave of itself to us, for our livelihood, our way or life," Horn Bear said.

Soon the tarp was covered with bloody footprints from people butchering the animal. They quartered it, sawing through bone, then sliced meat from the legs, rump, and the animal's huge hump. Children, some only 6, were given knives to cut away skin and fat.

The adults took turns dipping pieces of kidney in the animal's gall bladder bile. “Like salsa,” someone called out as others laughed.

The stomach was washed out for use in soup. The pelt was scraped and spread on a railing to dry. The skull was cleaned and the tongue, a delicacy, cut out.

Then came an assembly line of slicing, grinding and packaging of meat distributed to families through a food program run by the tribal agency that operates the ranch. The work lasted into the night.

A first for many, the harvest illustrates a challenge for the Rosebud Sioux and other tribes: few people have butchering skills and cultural knowledge to establish a personal connection with bison.

Katrina Fuller, who helped guide the butchering, dreams of training others so the reservation’s 20 communities can come to Wolakota for their own harvest. “Maybe not now, but in my lifetime," she said. “That’s what I want for everyone.”

Horn Bear, 73, said when he was very young his grandparents told him creation stories revolving around bison. But then he was forcibly enrolled in an Indian boarding school — government-backed institutions where tribal traditions were stamped out with beatings and other cruelties. The bison were already gone, and the schools sought to erase the stories of them too.

Standing on the blood-spattered tarp, Horn Bear said the harvest brings back what was almost totally taken away — his people's culture, economy, social fabric.

“It's like coming home to a way of life,” he said.

READ MORE Donald Trump, search warrant photo montage. (image: The New Yorker)

Donald Trump, search warrant photo montage. (image: The New Yorker)

Prosecutor Jack Smith must assemble a team, find office space and catch up on the long-running cases involving Donald Trump

Smith, a war crimes prosecutor at the International Criminal Court at The Hague, injured his leg in a recent bicycle accident and is recovering from surgery. He was tapped Friday to assume control over Justice Department investigations into Trump’s role in efforts to undo the results of the 2020 election, as well the department’s investigation into possible mishandling of national defense secrets at Trump’s Mar-a-Lago residence and private club, where more than 300 classified documents were recovered months after he left the White House.

Attorney General Merrick Garland said it was in the public interest to put a special counsel in charge of the cases, rather than Justice Department officials, to avoid a perceived conflict as Trump launches his 2024 presidential campaign and President Biden — who defeated Trump in 2020 — says he will run as well.

Garland and Smith have both vowed that the appointment of a special counsel will not slow the work in either case, and Smith has already become involved, albeit from the Netherlands. For example, a court filing Monday said Smith has reviewed arguments in a months-long court fight between the Justice Department and Trump’s lawyers over papers seized in the FBI’s Aug. 8 search of Mar-a-Lago.

A panel of federal appeals court judges in Atlanta is set to hear arguments Tuesday over whether a federal judge was right to appoint an outside legal expert known as a special master to review most of those documents.

Justice Department officials declined to answer questions Monday about the mechanics of the special counsel’s start. Nor would they say whether some senior officials who have been intimately involved with investigating Trump will now step back from that work, or temporarily leave their agency roles to work at the special counsel office.

Mary McCord, a former senior national security official at the Justice Department, said in this case she does not expect political appointees to work in the special counsel office, though career prosecutors could continue on the case in that new structure.

The Justice Department may have to make key personnel decisions to decide which career employees will move over to work on the special counsel team. For example, Jay Bratt, who heads the Justice Department’s counterintelligence section, has played a large role in the Mar-a-Lago investigation so far, but is likely working on other major investigations within the department that are not related to Trump.

If Bratt is detailed to the special counsel, he would not remain in his current role, McCord said.

That means the Justice Department must determine whether it makes more sense for Bratt to forgo his other responsibilities and work on the special counsel full-time. McCord said if Bratt remains in his current role, the special counsel could still seek advice from him.

Beyond those types of decisions, she said, she wouldn’t expect the course of the Mar-a-Lago investigation to change much because of Smith’s appointment — primarily because the criminal probe is well underway, with prosecutors and federal agents having secured key evidence.

“The idea is that Smith will be leading the day-to-day of the investigation,” McCord said, noting that federal regulations state that Garland can veto Smith’s charging decisions if he deems them to be “inappropriate and unwarranted.”

Checking off the boxes

Most of Smith’s former colleagues at the Justice Department generally praised him as a dedicated prosecutor who never flinched from tough cases, though one investigator who worked with him on public corruption cases was less complimentary.

“I think he’s very talented, enthusiastic, fearless, and truly dedicated to the prosecutor’s mission,” said Alan Vinegrad, a former federal prosecutor in New York who worked with Smith in the early 2000s. “He will be enthusiastic and throw himself into it.”

In contrast, Jeffrey Cortese, who served as the acting chief of the FBI’s public corruption unit in 2011 when Smith was his Justice Department counterpart supervising the Public Integrity Section, said he did not see Smith as quick-acting or effective in prosecuting public officials.

“At that time, it was understood that the fastest way for a case to die was to give it to PIN,” Cortese said, using the common nickname for the Public Integrity Section. “The frequency with which they declined investigative techniques and prosecutions was often a point of conflict between the FBI and the Justice Department.”

It is not unusual for tensions to flare up between FBI agents and Justice Department officials in corruption investigations, and Smith took over the Public Integrity Section at a fraught time for both agencies.

“When Jack was in charge, assuming a similar series of facts or a similar situation, I’d be surprised that PIN would even allow the case to be opened,” Cortese said. “So it makes me wonder why he’d want anything to do with the case today.”

Dana Boente, a former senior Justice Department official, said that when he heard Friday that there would be a special counsel, he immediately started trying to think about who would be selected, given all the political and practical complexities of the choice. It wasn’t easy.

Boente said the person would need to have both public corruption and national security experience, not be perceived as a partisan — and be willing to take the assignment, which could mean giving up a lucrative private sector job.

“I was rolling through names, and I really came up with nobody,” he said. “I had nobody.”

Boente said Smith, who he knows professionally, did not make his list of possible candidates. But when he heard later in the day that Garland had appointed him, Boente said, he immediately concluded Smith was a good choice who ticked all necessary boxes.

A matter of time

The speed and duration of special counsel investigations has been the subject of intense debate in recent years. The 2017 appointment of Robert S. Mueller III as special counsel ended up lasting two years as he probed possible links between Russian election interference and the Trump campaign, and whether as president, Trump sought to obstruct justice. Mueller’s investigation led to a number of charges, including against people in Trump’s orbit, but no charges against Trump. Mueller also produced a lengthy report of his findings.

Garland inherited a different special counsel probe from his predecessor, one that continues but is expected to wind down in the coming months. Special counsel John Durham, appointed two years ago during the Trump administration to continue probing how intelligence agencies investigated the alleged Russian election interference and the Trump campaign resulted in two acquittals at trial, and a guilty plea by a former FBI lawyer. Durham’s work is also expected to produce a written report.

While a special counsel has more freedom to manage cases and make decisions on their own, that person still works for the Justice Department and ultimately reports to the attorney general.

Brandon Van Grack, a former federal prosecutor who worked on Mueller’s special counsel, said he suspects Smith will not require as much time as Mueller did to get his operation up and running.

Unlike the Russia probe when the Mueller special counsel was announced, Van Grack said, both the Mar-a-Lago and Jan. 6 investigations appear to already have significant resources and personnel dedicated to them. Mueller assembled a team that included a number of people who did not work at the Justice Department; Van Grack said he doesn’t think Smith will need to hire as many outside people as the Mueller special counsel did.

“Some of the most remarkable people in the Mueller investigation were the people who were able to make the office space and logistics happen in a seemingly seamless fashion,” Van Grack said. “It was an incredibly burdensome process, and it’s unclear if special counsel Smith will or will need to take it on.”

READ MORE Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner. (photo: Filippo Monteforte/AFP/Getty Images)

Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner. (photo: Filippo Monteforte/AFP/Getty Images)

The Trumps were all appointed a court monitor to supervise their finances. Only Ivanka tried to get out of it.

In private letters, Ivanka’s attorneys tried to exclude her—and only her—from a New York state judge’s order that laid out how the family company is going to be overseen in the coming months, this source said.

On Thursday, Justice Arthur F. Engoron took the boldest move yet against the former president’s company. He gave the Trump Organization two weeks to give retired federal judge Barbara S. Jones "a full and accurate description of the corporate structure,” empowering her to review "all financial disclosures to any persons or entities" by the company. The Trumps must also inform the judge 30 days in advance of shifting any assets, ensuring they cannot outrun the New York attorney general's $250 million lawsuit.

AG Letitia James’ three-year investigation exposed how the family-run company routinely inflated the value of the properties it owns to snag better bank loans or maximize tax-write offs for donated land. She filed a lawsuit in September against the company’s various entities, some of its top brass, former President Donald Trump, and the offspring he made executives there: Don Jr., Ivanka, and Eric.

Despite Ivanka Trump’s strong, last-minute plea to escape scrutiny, Engoron was unmoved. The final order does not give her preferential treatment or even name her, meaning she too must abide by the rules.

Ivanka was, notably, the only defendant in the lawsuit who tried to negotiate for a better deal on her own, according to the source who spoke to The Daily Beast.

The Trump Organization is currently on appeal trying to fight off Engoron’s appointment of a monitor, who has special powers to keep the firm in check. As a former federal judge, Jones has taken on special assignments in high-profile cases in need of an independent arbiter. In this case, she is specifically tasked with ensuring the Trump Organization no longer files fake documents to banks and insurance companies. However, she is not allowed to oversee “normal, day-to-day business operations,” according to Engoron’s order last week.

Engoron was prompted to take such a decisive step after Trump indicated he intends to dodge the AG as best he can. Prosecutors worry that might include shifting business assets out of the AG’s reach. In court on the day he made his decision, the judge pointed out the way Trump comically started a company called Trump Organization II on the same day James filed her quarter-billion dollar lawsuit–basing it in Delaware no less, the shell company capital of the country.

Ivanka Trump has not been mentioned in court in recent hearings, but she’s still a defendant in the lawsuit, given her close involvement in the company’s dealmaking over the years.

Ivanka’s attorney on this matter, Reid M. Figel in Washington, D.C., did not respond to questions on Friday.

Her failed bid here is the latest sign that Trump’s eldest daughter continues to try to distance herself from his shameful legacy, which included separating migrant children from their parents at the U.S.-Mexico border, two presidential impeachments, and his unconstitutional attempt to remain in power after losing the 2020 election.

Last Tuesday, she refused to show up at her father’s long-awaited announcement that he is launching his 2024 presidential campaign.

“I love my father very much. This time around, I am choosing to prioritize my young children and the private life we are creating as a family,” Ivanka Trump said in a statement to Fox News. “I do not plan to be involved in politics.”

It didn’t start out this way. Ivanka Trump campaigned alongside her father in 2016, eventually falling under scrutiny over the way she used his 2017 inauguration to enrich the family company. She later raised all kinds of ethics red flags when he used his unchecked power to appoint her as a White House adviser. In that role, she violated federal rules by using a personal email account to communicate with Cabinet officials about government matters. Later, she was exposed over the way Secret Service agents tasked with protecting her and her husband, Jared Kushner, were prohibited from using bathrooms at the couple’s home, forcing them to spend $3,000 a month in taxpayer funds to rent a space nearby.

Ivanka has been engaged in a disappearing act ever since her father, as president, incited an attack on Congress in an attempt to halt the peaceful transfer of power for the first time in American history. Former President Trump’s political strategizing in the months after leaving the White House rarely, if ever, involved his daughter, sources previously told The Daily Beast. And while she did eventually submit to a “voluntary” interview with the Jan. 6 Committee, her testimony glossed over his unhinged allegations of election fraud and proved anything but damning against her father.

But that public relations strategy might not work in New York court. While she’s largely ghosted the political scene for the past two years, the AG’s lawsuit is squarely focused on holding her accountable for what she did a decade ago in her pivotal role as a company executive.

Much of those details are found in court filings. When she refused to sit down with investigators in January, the AG responded by publicly filing court papers closely documenting her exact role in exacerbating the Trump Organization’s long track record of lying about its properties’ market values.

The AG’s office identified her as “a key player in many of the transactions” under investigation, given how she was involved in cutting deals that relied on faked documents. Investigators said “she was responsible for securing loan terms” from Deutsche Bank for the company’s golf course in Doral, Florida, which involved turning over her father’s personal guarantee and statement of financial condition—documents that relied on a mountain of dubious property valuations.

Investigators also pointed out that she “played similar roles” in obtaining financing for the company’s projects in Chicago and Washington, D.C.

Despite that history, Ivanka Trump’s attorneys are now leaning hard on the idea that she hasn’t officially been at the Trump Organization since she joined her father in the White House. While the company has asked New York’s state appellate court to freeze the use of a monitor to surveil the firm’s business practices, Ivanka Trump went on her own and made a separate argument: that she should be let off scot-free.

“Ms. Trump has had no involvement for more than five years… Ms. Trump has had no role as an officer, director, or employee of the Trump Organization or any of its affiliates since at least January 2017,” her lawyers said in an appeal filed Nov. 7 alongside the company’s efforts to block the appointment of a court monitor.

“NY AG never intended to impose an injunction against Ms. Trump,” her lawyers wrote, noting that Judge Engoron did not specifically name her in court when he was discussing the company’s actions on the day he ordered the monitor.

In court papers, the AG’s office did not address Ivanka’s arguments. Instead, prosecutors merely supported the use of a court monitor to continue as planned.

The AG’s office did not respond to a request for comment about Ivanka Trump’s last-minute intervention directly with Judge Engoron.

This fight is scheduled to be back in court on Tuesday, when state investigators and Trump Organization lawyers are expected to discuss the ongoing lawsuit, which could go to trial next year.

The Trump Organization is already dealing with a firestorm, as the company is simultaneously on trial for dodging taxes in Manhattan criminal court. Last week, the public discovered that its disgraced chief financial officer—who seemed to have been fired after being indicted on tax fraud—is actually still on the payroll. In that case, jurors have heard about how executives regularly paid themselves as “independent contractors” and diverted pay for personal expenses to reduce their taxable income.

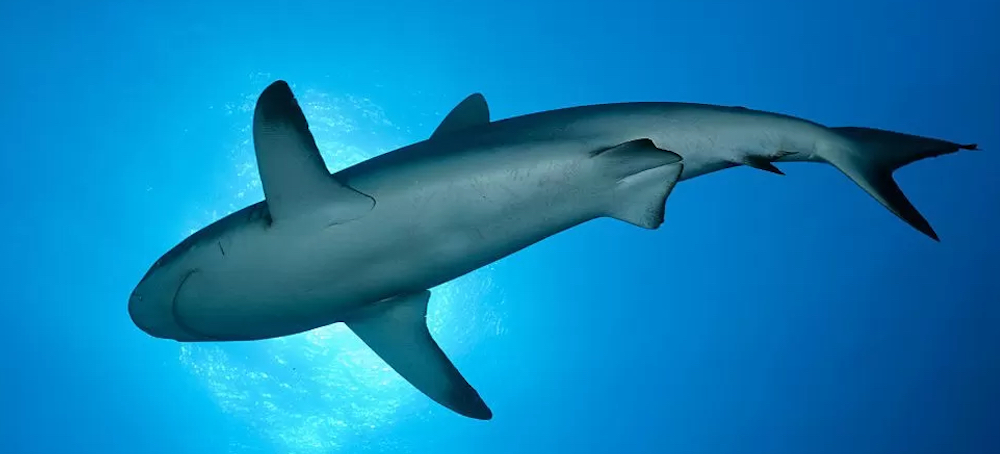

READ MORE A requiem shark swims underwater in the ocean. (photo: Getty Images)

A requiem shark swims underwater in the ocean. (photo: Getty Images)

More than 50 species of sharks are to be given protection from over-exploitation in what's being seen as a milestone for shark conservation.

The measures apply to the requiem shark family which includes tiger sharks, as well as to six small hammerhead sharks.

The sharks are being pushed to the edge of extinction by the trade in fins to make shark fin soup.

This "landmark" vote will give these two shark families "a fighting chance" of survival, said Sue Lieberman of the New York-based Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS).

"We know that there's a biodiversity crisis," she said. "One of the major threats to species in the wild is over-exploitation for trade."

Cross-border trade in wild plants and animals is regulated by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (Cites), which is designed to lower demand for threatened wildlife, allowing populations to recover.

Countries are meeting over two weeks to debate new proposals to protect sharks, turtles, songbirds and other species.

Thursday's vote at the 19th Conference of the Parties in Panama will bring most unsustainable global shark fin trade under regulation.

"The proposals adopted today for the requiem and hammerhead sharks, championed by the government of Panama, will forever change how the world's ocean predators are managed and protected," said Luke Warwick, director of shark and ray conservation at the WCS.

The two shark families make up over 50% of the trade in shark fins with many species threatened with extinction.

Listing them on Cites means that a country wishing to trade products has to issue a permit to exporters and produce a document which certifies that scientists have shown the permitted trade does not damage wild populations.

The decision has to be signed off at the end of the meeting, but is thought highly unlikely to be overturned.

The UK was among countries pushing for sharks to be listed at Cites. It has announced £4m of funding to help fight wildlife crime.

Conservation groups have long sounded alarm bells over the plight of sharks and rays. A quarter are classified as threatened, with commercial fishing for shark fins and meat a big factor in their demise.

Most sharks are at the top of the food chain, which makes them crucial to the health of the oceans. Losing them would have a big impact on other fish populations and, ultimately, human livelihoods.

The Cites Cop 19 runs from November 14-25 in Panama.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611