Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

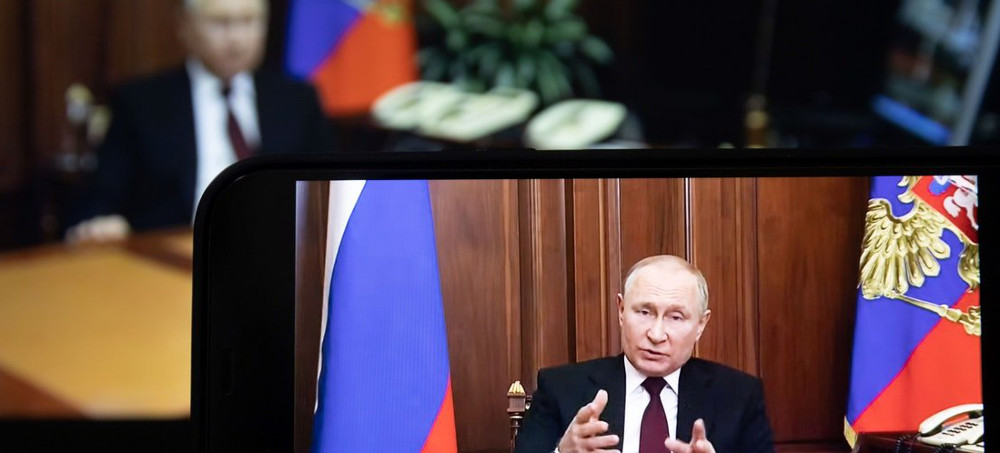

Putin’s regime spares no effort in distracting and propagandizing the citizenry. But it’s the lies of omission that do the most damage.

The current clash over truth, fiction, and everything in between has expanded the thousands of miles that physically divide parts of my family, so much so that these days, it often feels as if we reside on different planets. I’ve lived in the U.S. since the age of 4; I decided to become a citizen and build my life here. My mother and brother moved back to Moscow when I was in my late teens. Over the years, we’ve grown used to relying on technology to keep in touch. But while it’s never been easier to stay connected, I no longer know how much of the conversations we have with one another is real.

Does my mother truly believe that the images of a bombed maternity ward in Mariupol are fake? Is she too afraid to openly say otherwise, or is she lying to herself because the gruesome reality is too hard to swallow? These questions circle endlessly in my mind as the paranoia and the hurt between us on the war lead to our own clashes and long, discomfiting pauses. The war is the elephant in the room even when we try to avoid it for the sake of savoring a few minutes watching my toddler’s FaceTime antics with her grandmother.

Our family is hardly the only one experiencing this surreal and destructive divergence. There have been heartbreaking accounts of people living in Ukrainian cities under siege, whose loved ones in Russia refuse to recognize that their government is the aggressor responsible for the attack. For many other Russians living overseas, speaking to their relatives back home is akin to what millions of Americans encounter when dealing with a conspiracy-minded uncle or parent who believes the 2020 election was stolen, or that Covid-19 doesn’t exist. The assorted shades of denial are baffling, anger-inducing, and utterly depressing.

What makes people believe in lies? I’m hardly the only one seeking an answer. Conferences are being convened to analyze the scourge of disinformation in the digital age; former President Barack Obama just announced that he would be launching a campaign to fight it. But if my time at RT America taught me anything, it’s this: Omission can be just as powerful a tool as telling brazen lies or sowing suspicion.

Putin has made an art of strategic omission; during the conflict, he has only taken this to new extremes through heavy-footed censorship. As a result of a new law that makes spreading false information (which in practice means going against the government’s preferred narrative) punishable by up to 15 years in prison and other media supression, independent outlets have been shuttered, Western journalists have fled, and many social media platforms have been blocked. The Kremlin-controlled story is the only one most people see, leaving nothing and no one to contend with its narrative of Russian heroism in the face of Western oppression and Nazism in Ukraine.

As the brutal conflict has dragged on, requiring further justification for Russia’s losses, both the official narrative and the rants of commentators on the country’s state-run media outlets have become increasingly barbaric, bizarre, and contradictory. One version of events says the civilian massacre in Bucha was a result of Ukrainians shelling the area and then vilifying Russian soldiers, but another claims the atrocity was an entirely staged event. Some reports blame the sinking of the Russian warship Moskva on an accidental munitions explosion, yet others argue that its damage was caused by Ukrainian missiles, therefore justifying retaliation. The confusing swirl of analysis makes truth impossible to pinpoint and any public responsibility harder to enforce.

But exclusion and omission exist everywhere to varying degrees in the media. When I worked at RT America, from 2009 to 2012, I hosted a political talk show, covering all manner of stories with a liberal slant—from the environment and social justice to the war on terror, surveillance, and conservative attacks on voting access and women’s rights. These issues were and still are glaringly real, but while I was righteously expounding on them here at home, I convinced myself it was acceptable to ignore them in Russia. This contradiction was obvious to any casual observer, but my colleagues and I shielded ourselves in the fiction that RT America’s purpose was to focus on domestic news. I bought into the internal ideology that we weren’t compromising ourselves because our work showed American audiences critical news that other channels chose to avoid. This made it easier not to worry about who was writing the checks.

How could I have engaged in this cognitive dissonance? How could I participate in this game of omission? In the 10 years since I quit the network, I’ve repeatedly asked myself that question; I’ve tried to step back into the frame of mind that led me to those comfortable rationalizations. There are plenty of them: It was my first job out of college; they gave me an opportunity that no other network would bestow upon a 23-year-old; and, quite simply, it was a different time—one that offered hope to an immigrant who wanted to see the two cultures that shaped her find common ground. The “reset” in relations that Presidents Obama and Dmitri Medvedev heralded as their diplomatic mission had created an opening, and lent us a shred of legitimacy, leading respected journalists to be guests on my program or inviting me onto theirs.

/ In honor of Earth Day, TNR’s climate coverage is free to registered users until April 29. Start reading now.

As the political mood changed in response to Putin’s increasing authoritarianism and global aggression, and as Trump’s presidency heightened suspicion back to Cold War levels, my career prospects withered. I went from being on the Forbes “30 Under 30” list to becoming completely unhirable because of that first entry on my résumé. One network executive, I learned, would only refer to me as the “Russian Spy.”

I write all of this not to justify my lack of judgment—reconciling with my choices has meant that I have had to face consequences. But the mistakes that I made didn’t happen in a vacuum: My story is just one example of how the normalization of omission feeds collective denial and makes it easier to deem it culturally acceptable. We see these discrepancies everywhere, whether it be in the unspoken bias toward empathizing with white, European refugees over those from places like Syria or Central America or allowing figures like Condoleezza Rice, an architect of the war in Iraq, to comment on Russia’s invasion of a sovereign nation without any confrontation of her own past actions.

To choose to avoid uncomfortable truths only fuels the distrust that feeds the fire of disinformation. The failure to engage with hypocrisy doesn’t mean it never happened. The mental gymnastics that many Russians are performing right now in the hope that they might successfully skirt around the gaping hole about the war’s truth create a sense of disassociation from the violence being carried out in their name. It’s a temporary comfort that eventually ends in facing the stark reality some hope to avoid: that nothing will bring back the lives lost in this senseless, bloody conflict.

While most Russians get their news from the brainwashing machine of state-run television, not all of them buy into the farce of Putin’s war. Tens of thousands have fled the country; many of those who remain behind are digitally savvy enough to find ways to bypass the censorship of Western platforms through VPNs. Teenagers are still getting on Instagram and pirating Netflix content, the same way my father bought Beatles records on the black market or spent nights listening to scrambled broadcasts of Voice of America under his blanket during his youth in the Soviet Union. Culture and information will get through to those who want it, and this drastic reversal of a plugged-in society into total isolation will be widely felt.

But how do we actually break through the cracks and reach those on the other side of the veil? How do you convince a country that their patriotism and pride is being manipulated? Unfortunately, the antidote to lies isn’t as simple as flooding the zone with better information or funding Russian journalism—these are vital ingredients of a free society but won’t be sufficient on their own to transform the public psyche. And let’s face it: Having options and access hasn’t solved the disinformation dilemma in the U.S. or anywhere else in the world. Without context, history, and accountability, the water won’t reach the roots.

Fighting disinformation means confronting inconvenient truths, rather than eluding them. It’s a difficult endeavor, and one we’re often better at demanding of others than practicing ourselves. Russians know that their country didn’t just slip back into totalitarianism overnight, but as the founder of the recently shut-down independent Russian news channel TV Rain opined, they may not grasp that it’s a consequence of never reckoning with the Soviet Union’s repression after it collapsed.

Putin has instead nurtured Russia’s sense of national superiority with an agreeable version of history, dwelling on the collective courage the nation displayed in World War II, while distracting from the state’s return to despotic power with relative economic opportunity and promises of global respect. I tell you plainly: I didn’t want to admit what was happening. For years, when reporting on Russia or providing analysis in my career post-RT, I struggled to reconcile the increasingly hostile environment for political opposition with the bustling sights and sounds of what seemed like a thoroughly modern Moscow, where my friends took risks to attend protests by day and then brought me to amazing restaurants and bars by night or where I gathered with spectators from all over the world to watch the World Cup. As The New York Times’ Sabrina Tavernise described it, the city was full of contradictions, “happy, but unfree.”

Ultimately, there will be no real change in Russia until its people can partake in a period of collective reflection, in which the past and the truth of this war are fully laid on the table, no more omissions. These kinds of reckonings can be painful, but the fruits born from this discomfort help make democracy possible. This is the spirit that Putin has worked so very hard to quash. Sadly, I’m not sure how soon it might be restored: Most prominent activists at the core of any democracy movement have been imprisoned or have fled, along with young professionals primed to expect progressive change. This brain drain echoes multiple prior periods in the Russian people’s troubled history. Everyone else is inhabiting a country with two options: Be permeated by fear, frozen in an environment where people are reverting back to some of the darkest days of Soviet history and turning one another in to the authorities for saying the wrong thing or go on with life as usual, pretending nothing is wrong—maybe even buying into the delusion of wartime patriotic fervor.

At various times over the past few weeks, I’ve found myself on those calls with my mother, shocked and baffled by her ability to act as though things are normal. But this phenomenon has thoroughly penetrated the daily lives of the Russian people, even as they go on working and supporting their families. The thousands of parents and wives receiving their sons’ or husbands’ remains in body bags have to believe their loved ones died for something, some kind of worthy cause. How else can one live through such a tragic unraveling without pretending it isn’t happening? This is the diabolical comfort that lies by omission, large and small, offer: It’s easier to believe the deceit than face the pain of being eaten away by guilt.

Special Coverage: Ukraine, A Historic Resistance

READ MORE

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611