Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

This is where it all began, both the massive, months-long protests in 2013, which stopped the kleptocratic, Russophile president, Viktor Yanukovych, and started what can be called Ukraine’s renaissance, and the escalatory overreaction. After the killing of over 100 protestors didn’t stop the movement, Russia's President Vladimir Putin ordered the invasion of Crimea and Ukraine’s eastern provinces and, eight years later, the entire country, which is now Europe's worst war since World War Two. Putin had to attack the democracy developing on his doorstep simply because, if Ukrainians and Russians are so alike and integrated, as he keeps saying, Russians will want democracy, too.

Ukraine isn’t releasing casualty figures for security reasons, and the Russian Federation’s are unreliable, but total deaths have probably passed 400,000, according to recent estimates, notably by the renown historian, Yale professor and Ukraine expert and language speaker, Timothy Snyder. Ukraine may have suffered as many as 200,000 casualties, around half civilian, some of whom were also victims of torture. Almost a third of all Ukrainians have taken refuge, some four million abroad and eight million internally, with up to four million deported involuntarily into Russia. On October 10th, Russia began a strategic bombing campaign against infrastructure, which will kill many more civilians during the winter.

As it happens, the Russian tanks barreling down Ukraine’s highway M-07 toward Kyiv on February 24th, 2022, were also trying to get to the Maidan.

It is bigger than I expect, over two football pitches, with 19th century buildings on one side and modern ones on the other. This being Sunday—September 11th, oddly enough—and with the sky still full of dark clouds, the Maidan is empty save a smattering of soldiers on leave, tight-skirted women sipping Ukraine’s ubiquitous strong coffee, and vendors of patriotic, yellow-blue wrist bands with sad eyes. There are no soldiers on guard, as far as I can see, but scattered around like overgrown toy jacks are tank barriers, the so-called “hedgehogs,” or “yizhaky” in Ukrainian, some painted like child toys, others stacked like modern art. They are the only indicator of the war raging 250 miles to the east or south.

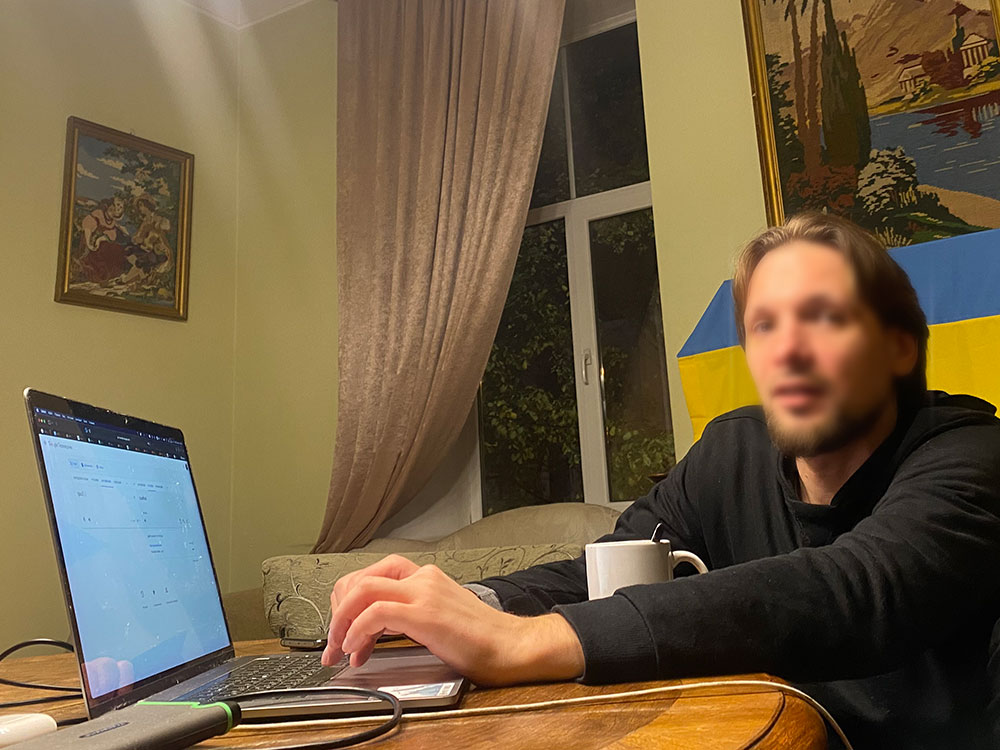

“There were many business people on Maidan,” I was told by Kirill, a handsome, bearded and genial 34-year-old, who directs and edits television commercials and is writing a romantic comedy—he loves old Woody Allen movies. I met Kirill a week earlier in Lviv, the quaint, cobblestoned café city in Ukraine’s west which serves as its San Francisco and is somewhat shielded from the war in the east. I’m omitting last names in the nightmarish event of a Russian takeover.

Kirill invited me to his place with a cordial “I have wine, beer and cannabis” and recounted his many days and couple of nights on the Maidan in 2014, to which he commuted from the south-eastern city of Dnipro, now under Russian bombardment. “I saw head of Ukraine’s Microsoft on Maidan. There were many older people,” he said.

Ukrainian doesn’t have articles of grammar, so Ukrainians often omit them in English, including the “the” in their country’s former name, The Ukraine. “I still translate from Russian to Ukrainian to English,” admitted Kirill, who was raised speaking Russian, as were a third of his compatriots, including President Volodymyr Zelensky, part of Ukraine’s long tradition of being bilingual, trilingual or quadrilingual. Middle class Ukrainians often speak some or decent English, which they start studying in high school and continue while listening to rock. Kirill is a fan of Creedence Clearwater Revival, to which he was introduced by his father on cassette tape.

“There were even babushkas,” grandmothers in Ukrainian and Russian but also Yiddish, added Alena, Kirill’s girlfriend, who is in her early 20s, paints and is studying web design but could side hustle modeling. There were also priests, doctors, lawyers, teachers and entrepreneurs, although the vast majority were young people, not as many women as men, workers and students (including high schoolers), nationalists and anarchists, skinheads and hipsters.

Ukraine has a large cohort of tattooed-pierced, who wear their story on their skin: men with significant neck or face work, often referencing girlfriends, women with colorful “sleeve” murals and multiple piercings. A 40-something cashier at a small supermarket near where I lived for six weeks in Lviv, who had a ready smile when ringing me up, had a Chinese character on her neck.

“It was like a big family,” I was told by Artur, 22, whom I met on the Maidan six days later. Artur is a graphic designer, skater and fan of all things Californian, including the spiky hairstyle he sports. After two weeks battling baton-wielding police, the Maidan protestors settled into a few months of occupation, punctuated by marches, rallies and more police attacks. “There were big pots of tea cooking everywhere, people playing football, playing music, discussing politics, which I did not understand,” Artur explained, “I was only 14.”

“Then fighting started again. Yanukovych started shooting people. That really shocked us. We weren’t used to Ukrainians killing Ukrainians. That building was set on fire,” he said, pointing at a government office which protestors occupied and turned into a community center. “They restored it last year. Then Russia invaded Crimea.”

“Before Maidan, there was no Ukraine. After Maidan, there is a real Ukraine,” Artur concluded. “Most Ukrainians had friends on Maidan. Everyone knew we were no longer part of Russia, and we were a real country, a real democracy.”

It was called the Maidan Revolution or Euro-Maidan Revolution, because protestors gathered on the Maidan on November 21st, 2013, the very day Yanukovych cancelled Ukraine’s Association Agreement with the European Union in order to pivot to Russia, and they flew E.U. flags. The call to protest on the Maidan was first made by an Afghan-Ukrainian journalist, Mustafa Masi Nayyem, in a heartfelt Facebook post, which he closed with “Likes do not count.” After the killings, it became known as the Revolution of Dignity or simply the Revolution.

I saw photos of the martyred Maidanites on the fence of the National Art Museum. Called the “Heavenly Hundred,” they were a near even mix of youth and middle aged, working class and intellectual, albeit over 95% men.

Ukraine already had three democracy movements or revolutions, as they like to call them. The Granite Revolution of 1991 helped get out the 90% vote to secede from the Soviet Union. The less successful Ukraine Without Kuchma tried to oust Leonid Kuchma, the corrupt ex-communist, but he remained president until 2005, when he declined to stand for a third term. The 2004 Orange Revolution started after Yanukovych or his cronies tried to poison his opponent and steal the election but were stopped by Ukraine’s supreme court as well as the protests.

Kirill also participated in the Orange Revolution, when he was 16, which also involved fighting the police and camping on the Maidan in winter, but “It was not same,” he said.

Ukrainians continued to use mostly Russian in school, watch Russian television, and support Russophile candidates, including Yanukovych, whom they elected president in 2010, fair and square, even though he was a convicted criminal and notoriously corrupt—his son, a dentist, was one of the country's richest men. But Ukrainian politicians were often mired in corruption scandals; Ukrainians are understanding; and Yanukovych reinvented himself by hiring a hot-shot political consultant for a decade. That would be Paul Manafort, eventually Donald Trump’s campaign manager, a Russia security risk and a convicted fraudster.

“We have victim mentality from so much suffering,” Kirill told me, referring to Ukraine’s annihilation by the Germans during World War Two, when six and a half million people died, about a fifth of the population, but also by the Soviets. Nine million Ukrainians and perhaps many more died during the Russian Civil War (1917-22), the Great Terror (1936-38), and the Holodomor, when Soviet authorities starved to death about four million people to punish supposed counter-revolutionaries. Denied to this day by some Russians and Russophiles, the forced famine of 1932 to ’33 had two more iterations, in 1945 and ‘47, I was surprised to learn from a young intellectual I met working in a Lviv coffeeshop, Andrii.

“After Maidan, all that changes,” Kirill said, his voice rising slightly. “We understand we can change our life, and our life is in our hands. It is not what some people do to us—we can do what we want!” No wonder Putin was petrified.

As I pondered their incredible achievement on the Maidan, I recalled that many Ukrainians revere Stepan Bandera, a 1940s-era independence fighter and the leader of the more violent wing of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, who is controversial but widely considered Ukraine's political founding father.

“Bandera? We love him,” replied Kirill, the first Ukrainian with whom I felt comfortable enough to ask about him, which precipitated an argument. As the son of a Polish-Jewish Holocaust survivor, I was painfully aware that some O.U.N. members had mass murdered Jews, Poles and Russians, the kernel of truth in Putin’s “Ukraine is controlled by Nazis” conspiracy theory. In fact, O.U.N. members brazenly slaughtered a few thousand Jews right on the streets of Lviv, some not far from where Kirill and I were sitting, the day the German Army entered the city, June 30th, 1941.

Kirill and I parted even closer friends, however, able to discuss difficult subjects. The genocideers numbered around 12,000, I later learned, from one of Professor Snyder’s Yale lectures uploaded to YouTube, while almost seven million Ukrainians were in the Red Army fighting the Nazis, a ratio of almost 600 to one. Two and half million of them died.

Contradicting another Russian conspiracy theory—that "Ukraine is not a real country and never existed”—they've been fighting for independence since the end of World War One, over a century ago, when they declared a state. Unfortunately, World War One morphed into the Russian Civil War, which swamped Ukraine in a ferocious free-for-all between the nationalists, czarists, anarchists, peasants and three foreign armies as well as the communists, who had to invade three times and use extreme violence to prevail (for this author's survey of that history go here).

Given that sanguineous, two-part slaughter and then the Holodomor, the Great Terror and World War Two, 1914 to ‘45 in Ukraine was the bloodiest period in one of the bloodiest regions in history. In a desperate bid to carve out a country, the O.U.N. planned to expel the Soviets by siding with the Nazis, on whom they would eventually turn, while some members murdered Jews, Poles and Russians, in keeping with the eliminationist nationalism then popular across Europe.

As the war's outcome became obvious, however, much of the O.U.N. had a change of heart. Driven by a rank and file devastated by fascism, totalitarianism and the resulting wars, the leadership whitewashed that history and liberalized their platform, while their guerrillas kept fighting the Soviets into the 1950s. After the Soviet Union ended in 1991, the O.U.N. reemerged, supported right-wing parties, and remained central to Ukrainian culture, including through songs, street names and posters celebrating Bandera. Indeed, their greeting, “Slava Ukraini, heroyam slava,” glory to Ukraine, glory to the heroes, is still popular, and the army made it their official salutation in 2018.

Nevertheless, after the fall of the wall, when hard-right parties became popular across Eastern Europe, not much in Ukraine. In fact, only the Svoboda party passed the required five percent vote, and only in 2012, to take seats in the Rada, or parliament, a half mile from the Maidan. Although Svoboda has a Nazi-like insignia and started as an extreme ultranationalist party, it moderated some of its positions by then and won 38 seats, eight percent of the Rada.

“There were not that many on Maidan who were extremists,” Artur told me. “And they were not that extreme, like extremists in U.S. or Germany. I know one.” Ukrainians often have friends across ideological divides, which can be fungible, I learned, and some O.U.N. officials were friends with, married to, or themselves Jews.

There were a few neo-Nazi skinheads on the Maidan, mostly part of the punk movement popular across the ex-Soviet bloc for its ability to express anger. The founders of Right Sector, a hard-right party, met on the Maidan, where they helped lead its defense against the police. Republican Senator John McCain and Victoria Nuland, the U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs, visited the Maidan and met with Svoboda and Right Sector leaders—Nuland famously handing out cookies. Although Nuland was supposedly managing American manipulation of the Maidan, the scandal surrounding her leaked phone call was mostly about her saying, “Fuck the E.U.,” and wanting to work around the institution so beloved on the Maidan.

Despite the Maidan’s diverse and vocal right-wing, however, they were vastly outnumbered and overshadowed by its liberals, leftists and anarchists, which is a powerful faction in Ukraine, one of the few countries where anarchists have mounted major parties or armies. Indeed, Svoboda lost all of its seats in the fall 2014 elections, despite its high-profile participation on the Maidan.

“There were a lot of poets on Maidan,” interjected Roman, Artur’s friend and fellow skater, who hadn’t said much until then. There were also many hippies, replete with long hair and colorful clothing, a movement dating to the late-‘60s in Ukraine, especially in Lviv.

During the Soviet dark ages, Lviv’s hippies lived underground, sometimes literally. They hid out in Lichakiv, the enormous cemetery for World War One soldiers but also politicians, authors and artists, who were often honored with large tombs and sculptures. I toured Lichakiv with Yarema, a photographer and artist with a gentle manner and shoulder-length hair, who wanted his photo taken next to the tomb of the sculptor Mykhailo Dzyndra, with its impressive abstract piece. Lviv’s most famous son is arguably Leopold Sacher-Masoch (1836-1895), a respected writer on Ukrainian and Jewish life as well as romance and eroticism (his name was borrowed for “masochism,” oddly enough, considering the longsuffering Ukrainians), but he is buried in Germany.

Yarema and I dined at the nearby Jerusalem, one of two Jewish restaurants in Lviv, which was almost a third Jewish until 1942, on a tasty mushroom-barley soup and gefilte fish, served by an interesting woman of color. I thought she might be Roma, given Jews and Roma sometimes ally on the edge of European societies, but Yarema learned her mother is Ukrainian and father Nigerian.

Yarema appears younger than his 31 years but has had gallery shows, teaches life drawing, does web development and carpentry, and recently produced a “jam festival” with friends, cooking kettles of fruit over a bonfire at his family’s run-down property outside Lviv, which he’s fixing into a small artists’ retreat.

Lviv’s hippie history was also recounted to me by Bhodan, a 24-year-old artist and illustrator, who has read Jack Kerouac and Carlos Castaneda but also Amnesia.in.ua, a Ukrainian website run by “enthusiastic ethnologists,” and discussed it with his elders, like the director of Lviv’s Artists Guild.

During the ‘70s and ‘80s, people involved in "samizdat," the Soviet bloc’s clandestine free-expression movement, used tapes to share music, and they held small, illegal performances. Lviv had its first music festival after glasnost in 1989, Chervona Ruta, named for a popular love song and meaning a species of flowers or perhaps "red regret." It featured punk, pop and communist-era acts and became biennial, while the city became known for festivals. A well-respected jazz festival, originally called Alfa, now Leopolis, has been mounted every June since 2011, although this year’s was postponed “until immediately after victory,” according to its website. There are some great local jazz players, notably pianist Igor Yusupov.

The hippies took over Virmenka Street, in Lviv’s closed-to-cars Old Town, where they still preside in cafes like the homey Facet, which fills the street with tables in summer, or the massive, multi-roomed Dzyga, built into the city’s mediaeval walls and now one of its premier jazz venues and art galleries as well as cafes. Yarema had a show there of photos from his Turkey road trip. Hippies also started going to the Carpathian Mountains, 250 miles south of Lviv, especially a waterfall called Shypit, meaning to whisper, “to camp out, play music and run around naked,” according to Bhodan, who hitchhiked there with his girlfriend a few years ago, for the summer solstice celebration.

“Up to one thousand people… gather and make a big fire and celebrate life, or whatever, using psychedelics, marijuana and music… There are little customs. No matter of the time, if you meet someone, they tell you ‘Good morning.’ Some people wake up in the evening because they were partying all night… You can join any small conversation with people you never met before—you can have heartwarming discussions.”

Considering the Maidan protesters' dedication to freedom and their months of street fighting, which culminated with police snipers shooting about 100 of their comrades, Yanukovych fleeing to Russia, and the Roda voting unanimously for fresh elections, they were enraged when Russia attacked Crimea on February 20th, 2014. Insignia-less and masked soldiers poured out of the Russian naval base in Sevastopol, which dates to 1772 and was being rented from Ukraine. Evidently, two pro-democracy revolutions in one decade was too much for a Kremlin turning autocratic under Putin. Crimea’s governor chose not to fight, since the state had become almost entirely Russian-speaking after the Muslim Tatars were deported to Siberia in 1944, and it had substantial autonomy from Kyiv.

Sanctions were levied and the ruble collapsed, but President Barack Obama, Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany and other western leaders accepted the conquest of Crimea as a real politic fait accompli. Citing its Russian-speaking population and Russia's lingering superpower status, they rationalized it was not worth significant protest or an escalatory arming of Ukraine, especially so soon after the disastrous Iraq War, and that stable relations would encourage Russian democracy.

Across Ukraine, there were also Ukrainian speakers, generally older and male, who opposed the Maidan and its related protests nationwide and supported Russophile politics. Some Russian speakers claimed discrimination by a Ukraino-centric establishment, but it's hard to distinguish valid complaints from opportunism or corruption by Russian patronage and conspiracy theories. In the eastern states of Donetsk and Luhansk, Russian language speakers and some paid agents started separatist rebellions in April 2014, using small squads of ragtag fighters. But they soon obtained weapons from the Russian army, which quietly invaded four months later, even as Putin categorically denied to Obama’s face any involvement with the “little green men.”

Militant Maidanites ran to the army or the paramilitary outfits organized on the Maidan by older veterans of the Soviet-Afghan War or younger Russian speakers, which belies allegations of widespread oppression. The latter were often soccer hooligans, also called “ultras,” or, to a lesser degree, white nationalists or punk intellectuals. The first commander of the now notorious-famous Azov Battalion, Andriy Biletsky, had a degree in history and decade experience organizing those three groups. The Azov debuted as a lightly-armed militia to oppose the separatists threatening Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second city and next to Russia, but came of age in the large city of Mariupol on the Azov Sea, off the Black Sea, hence their name. After Ukrainian Army units in Mariupol proved poorly equipped and commanded, Biletsky led his fighters south and defeated separatists in open battle, in the summer of 2014.

More pacifist Maidanites often supported their friends and relatives who were fighting with supplies, equipment, medical or cyber services, or money. A journalist, Miriam Dragina, started a flea market, Kyiv Market, specifically to donate its profits to the army, which recalls the old joke: What if the library got funding and the army had to do a bake sale? Some simply bought sport rifles and drove to the front. The Azov and other independent brigades were integrated into army command by the end of 2014, but the war is still a very popular, anti-imperialist insurgency, much like the American Revolutionary War or Vietnam-America War, involving people from all walks of life and political persuasions. Almost everyone I met was helping supply a unit with food, automobiles, ammunition and more.

Another testament to Ukrainian democracy is the 2019 election of President Volodymyr Zelensky, who is Jewish—as were two of Ukraine’s six other presidents—in a landslide 73% of the vote, due to his anti-corruption stance but also charmed life-follows-art story. Four years earlier, the accomplished comic, actor, writer, dancer and producer had created and starred in a hit television series, a combination sit-com and political satire with surrealist touches, “Servant of the People” (2015-19, available on Netflix). Zelensky plays a bumbling high school history teacher, living at home with his taxi-driving father and professor mother, whose students film him ranting against corruption. After it goes viral, they file the papers for his presidential run, which everyone regards as a joke until—spoiler alert—he wins and takes on the establishment with the help of family and friends.

Also appointing friends as ministers, the real-life President Zelensky, whose political party is called Servant of the People, had a shaky start. Despite successes countering corruption, he was accused of nepotism and favoring the oligarchs backing his large media company, and he made egregious accusations against his predecessor, which earned him low approval ratings. Doing his fictional character one better, however, Zelensky matured into a charismatic commander who refused to flee, rallied his constituents amid catastrophe, staved off defeat, and assumed a starring role in the ancient contest between democracy and fascism.

Also determined to stop Russian expansion are the 20,000 or so foreign fighters, notably the Georgians, whose nearby nation Putin invaded in 2008, due to their Rose Revolution five years earlier, and who have their own brigade, and the much more brutalized Chechens. Indeed, the Chechens endured not one but two vicious wars with Russia (1994-96 and 2000-01), which killed over 100,000 people, fully seven percent of their population. There are also fighters from America, Scandinavia, Britain and other regions, including an increasing number of Russians.

A small cadre of foreign volunteers covers the gaps in citizen care left by governmental and international agencies and Ukrainian self-help networks, often focusing on communities with emergency needs, helping disabled refugees and delivering lost pets, which can be considered therapy animals. Dirk and I met eight of them for beers at an upscale pizzeria, in the park next to Kyiv’s urban velodrome, a lighthearted but dedicated crew of Australians, Canadians, Europeans and one American.

Another democratic indicator is that the ultranationalists haven’t held a Rada seat since 2019, when Biletsky lost his, and Zhan Beleniuk became its first African-Ukrainian representative. A wrestler who took gold at the 2020 Summer Olympics, Beleniuk was number ten on the list for the Servant of the People party, which won 125 seats. The Azov, meanwhile, received funding from a Jewish oligarch, sacked a commander for antisemitic speech, and accepted Jewish fighters. Most importantly, they’re fighting to defend Ukraine against an imperialist invader committing genocide.

Genocide, as defined by the United Nations, is the attempt to eliminate a culture, language or nation as well as people. Russian intentions are clear, from their officials' overt references—“Ukraine is not a country”—to military actions: the bombing of civilian infrastructure and cultural institutions, the destruction of monuments, including to the Holodomor, the use of rape as a weapon of war, the deportation of children and young women into Russia to be Russified and estranged from their families, and the sadistic torture of civilians, using amputation and castration.

No wonder the Azov enjoy nationwide adulation, notably the big banners honoring the “Azovstal Defenders” in downtown Kyiv, Lviv and other cities, for their second defense of Mariupol, from March 1st to May 20th, 2022, when they fought the Russians to the death.

“They are like gods!” I was told by Oksana, an effervescent woman of about 22, whom I met in Lviv, after offering to take her selfie in front of the city’s display of destroyed Russian tanks. Oksana studied computer programming but much prefers working as a recruiter for the Georgian Brigade.

The Stalingrad-like siege of Mariupol destroyed or damaged over 90% of the city’s structures and may have killed up to 85,000 civilians, according to recent reports, including almost 600 sheltering in a theater marked “children” in large letters on March 24th. About 3,000 fighters, some foreign, and 1,000 civilians, including children, retreated to the massive, Cold-War-era bomb shelters beneath the city-sized Azovstal Iron and Steel Works, which is owned by a Muslim-Ukrainian oligarch. As gangrene, black mold and starvation set in, under constant bombardment, including by thermobaric bombs, with only a few helicopters flying supplies in and wounded out, 20 feet above the water to evade Russian radar, the mostly Azov fighters endured for 11 weeks.

Mariupol’s Thermopylae cum “Blade Runner” cum reality TV show was watched by many Ukrainians on videos uploaded thru the Starlink satellite system, which was largely donated by Elon Musk and is also essential for operating drones and artillery. The siege ended when the surviving defenders received safe passage in exchange for a few high-profile Russian prisoners, although 53 Azov were murdered in a Donetsk P.O.W. camp on July 28th. They were killed by Ukrainian shelling, according to Russian officials.

“How did you grow up so healthy in such an environment?” I asked Kirill, the next time we hung out. “Was your father an optimist?” “Yes,” he said. “He was a good man, nice man. He liked rock music and was devout Christian. And he was Jewish.” Kirill only learned that fact after his father died and, just last year, that his mother is as well, a secret they kept iron clad due to Soviet and Ukrainian antisemitism.

Nevertheless, the secret Jewish parent or grandparent story is fairly common in Ukraine. I met many Ukrainians with Jewish heritage, and Kirill once joked, “Half of Lviv is half Jewish.” And Jews date to the eighth century, when the elites of the Khazar Empire converted to Judaism, over a century before the birth of either Ukrainian or Russian culture. Despite the many gruesome pogroms—by the Cossacks in the 17th century, which included extensive rape, the czarists in 1920, and the Nazi genocide of one and a half million Ukrainian Jews—and today’s small number of publicly professing Jews, about half a percent, they remained somewhat integrated and represented throughout the country. Indeed, Ukraine still has Europe’s second largest Jewish population: coming after Poland before World War Two, now following France.

President Zelensky, 45, hails from a modest city in central Ukraine and studied law before going into entertainment. Natan Khazin, a 50-ish rabbi from Odessa, Ukraine’s third largest city and historically Jewish, was on the Maidan and helped its fighters with his experience in the Israel Defense Forces. Khazin even calls himself a “Zhido-Bandera,” a Jewish follower of Stepan Bandera. Nayyem, the Maidan organizer of Afghan extraction, married a Jewish woman and is raising his children Jewish. Meanwhile, the annual number of antisemitic incidents in Ukraine is often less than in France or England.

Kirill adores his mother, as becomes obvious when he takes her calls with a dulcet “Yes, Mama?” In fact, he moved her to Lviv, and her own apartment, when he and Alena evacuated Kyiv in December 2021, two months before the war. “I was listening to BBC and your president,” he explained. Kirill thinks Zelensky may have to answer for why Ukraine was so unprepared for the invasion: “They were building roads, when they should have been building rockets.” “But only after the war,” he added.

Ukrainian women seem extra loving, as is often the case in oppressed communities. I noticed on the streets of Lviv and Kyiv how they cared for children, who often clutch stuffed animals, due to the anxiety of war, or walk with beaus, holding hands and laughing, or girlfriends, in pairs or groups, also holding hands and laughing or chatting animatedly while out for coffee. Or when they cry and hug. Many seem to be Eastern European romantics, cautiously hopeful in the face of adversity, a worldview I learned about from my Polish mother and on four trips to Poland, Ukraine’s sibling society (Lviv was Polish until the Soviet invasion of 1939).

Their literary romanticism, meanwhile, dates to the poet, painter and folklorist Taras Shevchenko (1814-1861), who was born an enslaved serf near Kyiv but secretly read books and studied art and became the country’s cultural founding father, honored many times more than Bandera with street names, statues or on the currency, the hryvnia (pronounced “ravinia”). Other luminary local authors include Nikolai Gogol (1809-1852), who became a titan of Russian literature by inventing “the grotesque," an essential genre for understanding Eastern Europe, Sholem Aleichem (1859-1916), whose tales of Jewish life inspired “Fiddler on the Roof” and Mark Twain, and Isaac Babel (1894-1940), also from Odessa and also Jewish, one of the Soviet Union’s most respected authors and journalists as well as modern stylists, until the secret police murdered him, in keeping with their grotesque tradition of killing people to solve problems.

As Dirk and I walk out on the Maidan that glorious September 11th morning, I am struck by its large, open space but also strange structures, like the glass domes or comedic sculptures at its north end, where we entered, or the tall column capped by a figure in the distance. Despite the storm clouds, a wan sun shines, people are smiling, and there’s an eerie peace.

Unbeknownst to us on the Maidan at that moment, 250 miles to the east, around Ukraine’s second city of Kharkiv, Ukrainian Davids are on the march. Indeed, they retook more territory in days than the Russian Goliath conquered in months, driving the invaders into a panicked retreat and to abandon immense amounts of equipment and ammunition. President Zelensky announces this battlefield success that very evening, in his nightly national address, the first good news Ukrainians have heard since their storied defense of Kyiv, six months earlier.

“They used special forces, drones and ‘maneuverable warfare’ to get behind the Russians and spook them into running,” a military analyst on CNN explained on September 13th, although he forgot to mention their masterful military feint. For weeks, President Zelensky had been talking up a counterattack in the south on Kherson, the only regional capitol conquered in Russia’s most recent invasion, which tricked them into withdrawing troops from the north near Kharkiv. Already known as a brave and funny commander in chief, Zelensky was proving to be a brilliant one.

“We love our president,” Alena had told me with a smile, which suggested a romantic-sexual side to national struggle.

Zelensky pushed his generals to attack, even though the Americans kept vetoing their battle plans, as the two militaries computer war-gamed during the summer in Ramstein, Germany. They had to break the entrenched front lines before winter, obviously, as a frozen war of attrition would benefit better-armed Russians. But they also had to prove to citizens and allies alike that the cornucopia of donated war materiel was being put to good use. As of September 11th, the U.S. had provided about $19 billion worth, five times the annual allotment to Israel, including advanced HIMAR missiles and promises of much more, although that could be reduced or decimated by a Republican-controlled Congress.

Dirk and I thread our way across the six lanes of Khreshchatyk Avenue, Kyiv’s main shopping street, which intersects the Maidan, since we neglected to notice the pedestrian tunnel for that purpose. We ascend the Maidan’s block-wide steps and approach its centerpiece, the gold-plated column crowned by Berehynia, the Slavic fertility goddess. Only then do we see, in the middle of the square’s proscenium, the dance troupe. It consists of a dozen women, including one of color (Ukraine has a substantial Roma population as well as some African immigrants), two men and a camera crew. Between takes of turning, jumping and gesticulating, the dancers goof off and giggle, although still well aware of the fierce battles raging five hours drive east or south. Each one probably has a cousin or friend under shellfire, at the front or already in the earth.

Kyiv seems normal, except for the passport control on the roads entering town and at the train station, the sandbags and plywood around important buildings and statues, the machine gun nests at official entrances, and the occasional air raid sirens, which oblige museums to evacuate, but everyone else ignores. People laugh in the streets, and the restaurants are full—up to a 30-minute wait at the most popular—but few openly celebrated Zelensky’s announcement of battlefield success on September 11th, as was reported in the American press. Almost everyone I met was still nervous, some were traumatized, and a few were having panic attacks.

Fifteen miles north of the Maidan is Bucha, whose residents reported the first Russian war crimes spree. Bucha bore the brunt of Russian bloodlust because it was where their once-vaunted armor was ambushed by Ukrainian regulars but also townspeople tossing Molotov cocktails. The Ukrainians destroyed up to a dozen tanks and vehicles which triggered a 25-mile-long military traffic jam and ruined Putin’s plans for a one-week war. Amazingly, the Russian soldiers carried dress uniforms for a victory parade, while many officers booked reservations at Kyiv’s premier hotels and restaurants.

Dirk Grosser is of medium height, strong build and open demeanor. He favors plaid shirts and hiking boots, perhaps in deference to his practical people from the once-East German city of Dresden, where he lives in a three-story townhouse he renovated himself. On our deluge drive from Lviv to Kyiv, Dirk told me how he raced all night from Germany to Ukraine, after a late start due to house guests, to attend a seminar he organized about what artists should do during a war. A performance artist and filmmaker by profession, Dirk started doing small conferences in this vein after learning some of his leftist friends supported the Russian invasion. In addition, he was shooting a related documentary, tentatively titled “Exile”.

Amazed by Dirk’s ambition and hard work as well as interested in the cause, I volunteered to production assist: find translators, do second camera and the like. Three days after our first Maidan visit, we drove the M-07 north to the once-bucolic commuter town of Bucha. We set up next to its verdant central walkway in the outdoor tables of a fast-food joint, which had umbrellas to ward off the light rain.

Every person we asked had had harrowing experiences. “I was in a basement for weeks,” a towheaded, ten-year-old boy, riding around on his scooter, told us, “I was very scared.” After calling his mother on his smart phone, which almost all middleclass kids have, he said, “She doesn’t want me filmed.”

Between wiping her eyes, a thin, expressive, perhaps 50-year-old Roma woman named Nadia told us about the rapes, including of underage girls, the men trying to remove their military tattoos, a death sentence under Russian occupation, the summary executions, which sometimes included torture or amputation, and the often audible screaming. The interviews were conducted in Ukrainian, which neither Dirk nor I understand, but our translator, an aid organizer from Kyiv also named Nadia, provided periodic summaries in English. At the end of the interview, most of us were crying, and we all hugged Bucha Nadia.

Bucha’s streets were littered with bodies for weeks, since the residents were too fearful to collect them. The kill count now exceeds 450, almost 2% of the population but will probably go much higher. Mass graves full of civilians, some showing signs of torture, amputation and even castration, have been uncovered in the liberated towns around Kharkiv like Izium.

“We were given orders to kill everyone we see,” a Russian soldier told his girlfriend by phone from Bucha, according to call transcripts published by the New York Times on September 28th.

Evidently, the Kremlin intends to terrorize the Ukrainians into submission, including the ethnic Russians they're supposedly saving, and escape recrimination through propaganda and conspiracy theories. This strategy will work, they assume, by virtue of their long expertise with such subterfuges but also the current popularity of conspiracism worldwide and cyberspace's capacity for disinformation. Hence, the Russians keep claiming they're fighting Nazis, even as they become like Nazis. Despite the obvious hypocrisy, their repetition of big lies allows them to not only dodge the bad press but transfer it to their enemies.

As if on cue, when the Bucha story broke on April 1st, Russian diplomats and media figures began accusing the Ukrainians of lying and fabricating evidence, using actors, ketchup and Photoshop, a gaslighting calumny that many Russians and Russophiles continue to repeat ad nauseam today.

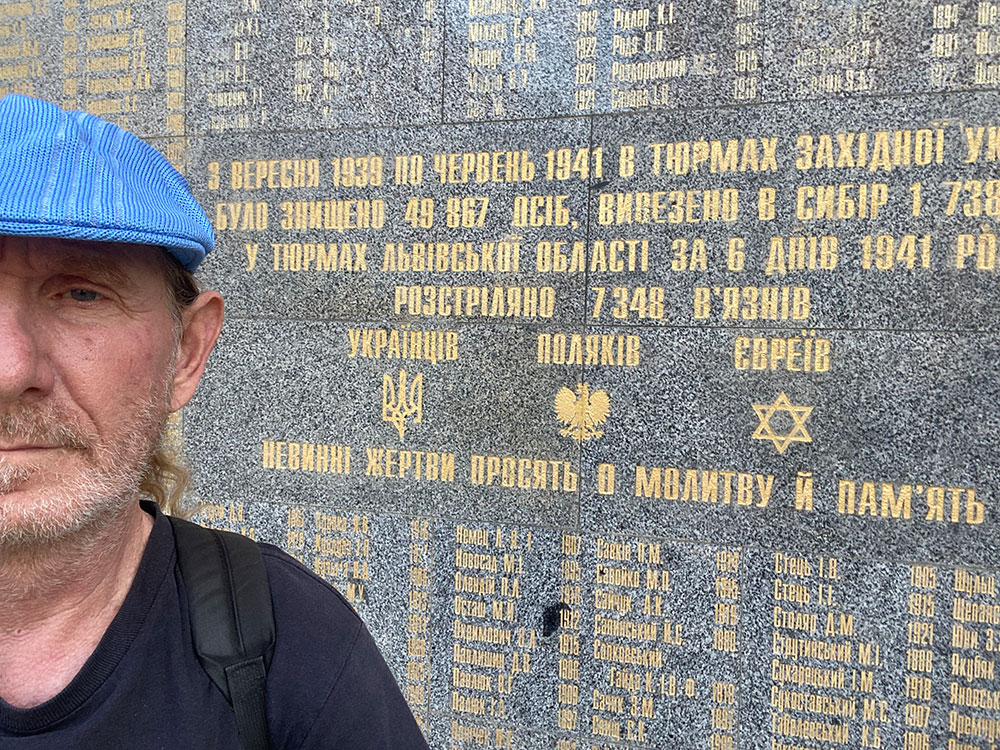

On our way back from filming in Bucha, to complete our atrocity tour, we stopped by Babyn Yar, the ravine four miles north of the Maidan better known by its Russian name, Babi Yar. This is where the Nazis, also compulsive conspiracy theorists, slaughtered some 33,700 Jews in two days, still considered a record. Now located in a large, popular city park, Babyn Yar features an imaginative, multifaceted memorial. Right on the ravine’s edge, in fact, is a two-sided synagogue adorned with colorful animals, clouds and Hebrew phrases, a fantasy version of a traditional Ukrainian synagogue. The walls are hinged and there is an oversized hand-crank, the guard showed me, which folds the entire structure into a 20-foot-tall wooden case, suggesting children’s theater or the Jewish need for portability.

Some people were probably offended when the Babyn Yar Memorial foundation—formed in 2017, after the Soviets downplayed the Holocaust for decades, with an all-star board chaired by the Russian-Israeli scientist and dissident Nathan Sharansky and featuring rabbis, artists and politicians—decided to build a psychedelic, fold-up synagogue to commemorate what is traditionally marked by dark stone memorials or anguished sculptures. I myself was confused. But as I walked around and mulled it over, I realized: This is where Ukrainian middle schoolers are brought to look down into that monstrous death hole and, if you want to get metaphorical about it, what the souls there see looking up. Surely a positive image of Ukraine’s millennia-old Judaism provides some solace.

Dirk and I hiked down the path behind the synagogue into the ravine, which must have been deep, given it now holds around 90,000 Jewish bodies, almost all of Kyiv’s pre-war Jewish population, and a similar total of Roma, Russian and Ukrainian nationalist bodies, an irony not lost on some Ukrainians. Dirk can be contrarian, but he readily joined me in a meditative “om” chant. As a Holocaust survivor’s son, who has long grappled with this apocalyptic nightmare, I felt a certain peace in Babyn Yar’s death hole: Ukrainians were finally healing from that national trauma using sophisticated art and psychology. Tragically, it was just in time for the next atrocity.

Babyn Yar’s memorial complex also has an eight-foot, dark stone menorah, which serves as its centerpiece, and a large, black stone wall, although unlike anything I’ve seen at other Holocaust memorials. Titled “Crystal Wall of Crying” and installed in 2021, it was designed by Marina Abramović, the legendary Serbian performance artist, and has dozens of large crystals, which glow with light and are embedded in the wall. A football pitch away, there is a large, circular, silver platform with a dozen silver pillars, each fitted with an eyepiece for viewing archival Holocaust footage—everything riddled with bullet holes. The Holocaust in Ukraine was largely by bullets. Neither “Psychedelic Synagogue” nor “Riddled Silver Pillars” are listed on the Memorial’s Wikipedia page, and I’ve yet to find their creators’ names or installation dates.

“When Bucha happened, we were all crying,” I was told by Marina, a 20-something woman who works in the arts, including promoting her reserved painter boyfriend, and has an irrepressible laugh. “But we can’t stay that way. If we let them depress us, they will win.” Many Ukrainians told me they were depressed for a week or a month after February 24th but were energized by friends, the exigencies of war or Ukraine’s stoic tradition.

Marina, whom I met in Lviv but is also a refugee from Dnipro, which is half way between Kharkiv and Kherson and was being shelled as we spoke, just returned from the U.S., where she visited her mother in Minneapolis and could have applied for refugee status. “I saw only a few Ukrainian flags or signs of solidarity,” she said. “At a club, the singer said she wanted to dedicate the next song to those who have suffered. I thought she meant us, but she was referring to George Floyd.” Marina also spends all her earnings to support Ukraine’s economy.

“Some people say this being happy is wrong,” Kirill told me. “But my friends who are soldiers say, ‘We have to protect this. You must do your normal life because we are in stress, and sometimes we need to go enjoy this.’” Kirill’s friends reminded me of the Babyn Yar installations, which I came to see as suggesting we appreciate life even as we mourn mass death, learn about horrific history and fight fascism, which I also learned from my mother's experiences in the Holocaust. The Ukrainians perfected this philosophy, evidently, over a century of being butchered mercilessly by the Soviets, Germans and now Russians.

“Some people outside the Maidan were angry with us, saying, ‘It was like a festival, not a protest,’” said the Ukrainian popstar Ruslana Lyzhychko in “Winter on Fire” (2015), an excellent documentary about the Maidan Revolution (available on Netflix). Ruslana, as she is known, was also a center-right Rada representative but fell in love with the kids of Maidan and became their celebrity spokesperson.

As the Maidan dancers prance and gambol across Ukraine’s main stage, with no official minders and only Dirk, myself and four or five others watching or filming, I realize I’m witnessing a minor miracle: Ukrainians expressing freedom, fancy and joy in the shadow of a gruesome, genocidal war. When they take a water break, however, I continue my exploration and wander up the steps to Berehynia, standing resplendent in the slight sun, gold leaf gleaming off her column and the foliage she holds above her head.

That’s when I notice, behind Berehynia’s column, the art show: two dozen, ten-foot-tall, artistic iron easels with pages from a graphic novel, "Dad" by Oleksandr Komiakhov, I find out by Google Translating a photo of the credit. The title page surprises me. It has a man and woman seemingly straight from the Burning Man festival: him heavily bearded, wearing a motorcycle helmet and holding a baseball bat; her with pierced lips and a furry cat hat and cradling a box of Molotov cocktails.

“If these are the mythical heroes of Ukraine,” I think, or something along those lines, “They really have achieved a certain free speech absolutism, and freedom in general, a democracy which enshrines art and ideas, which many Ukrainians have been enjoying for almost a decade… Many of the kids of Maidan must be in government by now.”

“They are all phonies, patsies and spies!” would the rebuttal of many Russophiles and hard rightwingers but also some leftists, including friends of mine. Sandy Sanders, a neighbor, artist and seemingly decent guy, whom I’ve known for 20 years, denounced one of my heartfelt Facebook posts from Ukraine by insisting the Maidan Revolution was a “U.S.-financed coup” and the separatist struggle in the Donbas was a “neo-Nazi civil war.” Since he doesn’t seem like a Machiavellian manipulator, Sandy must be utterly unaware that he’s parroting Putin’s conspiracy theories, that people power is organic and hard to manipulate, or that fascist societies can't be paragons of liberty.

In fact, there’s precious little police presence in Ukraine, although martial law was declared on day one and they’re in a duel to the death with an adversary thrice their size and with a long resume of atrocity and spy craft. Indeed, three teams of pro-Russia Chechens tried to kill President Zelensky early in the war, the attack on Kyiv's secondary airport by Russian paratroopers and over 100 helicopters delivered special forces to decapitate the government, and they continue attempting to infiltrate spies, saboteurs and assassins, or to enlist them in sitio.

Nevertheless, in all of downtown Lviv, I saw only two soldiers standing guard (the 24-hour sentries at the central bank), while the nationwide curfew of 11 p.m., widely adhered to by Ukrainians, was barely enforced. On my many walks home at midnight or later, I saw few police patrols and no stops.

Five days after my first Maidan visit, I was stopped by a soldier who saw me take a selfie near a trainyard and demanded my phone and passport. I braced myself. “There is still a lot of corruption,” a few Ukrainians had warned me. Fifteen minutes later, however, I was chatting amicably in English with his commanding officer, who asked me to delete the photo and dismissed me with “Have a fun visit to Kyiv.”

Also defending Ukraine from Russian espionage is their “safe city” system, using surveillance cameras and artificial intelligence, Kirill told me. Amazingly, at the start of the war, Ukrainian cyber security held off the onslaught of Russia’s notorious hacker army. Others referred to their long, painful learning curve with Kremlin agents. “The K.G.B. killed my grandfather,” a long-haired Lviv waiter told me with a laugh, “It’s a sad story.”

As I review the Maidan's graphic novel, I am struck by the quality of Komiakhov’s drawings and visual storytelling but also that I’ll need a translator to make sense of it, so I circle back to Berehynia. Sitting next to her majestic column, surveying her sacred domain, the quarter-mile oval of Maidan Nezalezhnosti, or Independence Square, the name it was given after the 1991 Granite Revolution, I think about what Kirill, Artur and the others said, or I have read or viewed. Bit by bit, I begin to imagine how the Maidan looked eight years ago: teaming with tens of thousands of demonstrators—up to a million on some marches—waving signs and E.U. flags and chanting, “Ukraine is part of Europe!” “Together to the end!” and, after the police attacks, “Convict out!” directly at Yanukovych.

They also carried plastic sheets for the torrential rains. Within a few weeks, that plastic was woven into a sea of tents, barricades, lean-tos and kitchens, inhabited by a vast cross-section of Ukrainians, from tech workers and academics to dirty, young men carrying bats. One young man told me his dad went to the Maidan because “he always had to be in middle of everything,” while another said his dad promised to take him, but his mother intervened—he was only 14. The protesters discussed and debated, played guitars and drums, and DJed and danced, even though there was almost no alcohol on the Maidan. When temperatures plummeted and snow blanketed the vast encampment, they gathered around 50-gallon-drum fires.

As I ponder this critical history, about which I knew little before entering Ukraine on August 23rd (its Independence Day from the Soviet Union, coincidentally), a moving moment from the Maidan Revolution—one I just learned about from the documentary “Fire in Winter”—comes to my mind.

After two weeks of protests, the Berkut riot police tried to clear the Maidan a second time. Their first attempt, on November 30th, 2013, merely shocked the protestors, who fought back fiercely or called their parents, some of whom joined them on the Maidan. The night of December 10th would be different, they realized, as they watched police buses pull up on Khreshchatyk Avenue and spit out hundreds of officers with helmets, shields and cement truncheons. As the women went to the proscenium for protection, some of the men—some wearing helmets, many carrying bats—went to face the Berkut. Meanwhile, a lone figure sprinted away, a theology student named Ivan Sydor.

As it happened, the official bell ringer for the 11th century Cathedral of St. Michael, on the hill north of the Maidan, was Sydor. Undoubtedly gasping for breath as he topped the belfry stairs around 1 a.m., he began ringing St. Michael’s bells furiously, as had his forbears during the Mongol invasion. Sydor rang for four hours and roused thousands, who ran to the Maidan, surrounded the Berkut and scared them off.

Thinking about Sydor’s desperate appeal, the Kyivers’ stalwart response and the bravery of the Maidan fighters, I pull my cap over my eyes, lest one of the dancers or Dirk see I’m crying.

Ukraine was much like Russia in the 1990s, devastated by “perestroika," the switch from central planning to a market economy, and plagued by bribery, mafias, assassinations and oligarchs, whose acquisition of immense wealth was inevitable. Whoever learned the tricks of post-Soviet capitalism first, from using armed gangs to seize industries to leveraging loans, manipulating laws or simply providing a decent product or service, made millions or billions. As Russia kept turning more authoritarian, corrupt and kleptocratic, however, Ukraine had three democratic revolutions, each of which increased to some degree political representation and economic opportunity and decreased corruption but especially the last.

As well as being pro -democracy and -Europe and anti -corruption and -authoritarian, the Maidan Revolution was sophisticated and centrist enough to galvanize a majority of Ukrainians. Indeed, it stimulated civic responsibility and cultural creativity, from governmental reform and motivated soldiers to music, fashion and art, and it unified Ukraine’s left, right and center. So much so, I took to remarking, “The Maidan is where Ukrainians fell in love with each other,” often to approving nods from Ukrainians.

I met another Maidan offspring extraordinaire at a bookstall in a Kyiv park, after its proprietor waved her over to translate. Clad in a camouflage uniform and cap, Diana, 22, seemed like a scout or soldier, if perhaps an officer, given her poise and long, single braid, in the Ukrainian fashion. Also from Odessa, a town laurelled for its multiculturalism and intellectuals as well as Jewish heritage, Diana and I were soon discussing current events.

“You get inspired to do something when your neighbor goes…” Diana said, gesturing wildly. “Boom?” I said. “Yes,” she said, “We learned a lot from our revolution.” “You mean Maidan?” “Yes,” she said, “We learned we can do great things. We learned that if a president doesn’t do what we want, we can take him out.”

After I invited Diana and her camo-ed colleagues, Margherita, Maria and Christina, to tea, she explained they were studying to become military lawyers. “Soon to be a growth industry,” I said, “In light of Russian war crimes,” to which Diana laughed loudly but her friends smiled politely. The Ukrainian Army is around one fifth women, some serving in combat.

“Ukraine is building a digital state,” I was told by Varvara, or Barbara, since the Ukrainian “v” is the western “b.” “It is more advanced than most of Europe—and I’ve been to Europe.” I met Varvara as she photographed food for the website of Cukor Black, a restaurant in Kryva Lypa, one of Lviv’s many courtyards or closed streets full of restaurants, bars and especially coffee shops. I was wolfing down a dish of their waffles, poached eggs, fish balls and arugula, all drizzled with crème fresh and accompanied by a delicious double cappuccino.

In fact, Lviv’s downtown and Old Town have more coffee shops per capita than any city I’ve ever seen, and a great cappuccino can be had from a kiosk on the streets of Kyiv for under a buck, thanks to the coffee craze that swept the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the early 1800s. Middleclass Ukrainians can be quite foodie, with tastes ranging from sushi and stir fry to pizza and pesto or borscht, pierogi and herring, which is also traditional Jewish food.

“I have many friends who are programmers for German companies,” continued Varvara, whose half-dreadlocked, blonde bob gives her round face an idiosyncratic beauty. “All good restaurants have this,” she added, tapping my table’s QR code, which brings up the menu on a phone. Most patrons also pay by phone, I noticed.

Another burgeoning Ukrainian business is modelling, I was told by Hanna, whom I also met in Kryva Lypa, at the record and DJ equipment shop Vinyl Club. Two days before, I saw three fashion shoots in Old Town, when it was bathed in golden afternoon light, before the onslaught of autumn rains. Hanna, who is petit and favors the blond-but-approachable look, recently returned from a shoot in Portugal but has modeled all over Europe. “Ukrainian models are popular,” she said, “Because we work hard.” Also playing a part, I suspect, is that Ukrainians are romantic, select for beauty and intermarry.

******

Reader Supported News is the Publication of Origin for this work. Permission to republish is freely granted with credit and a link back to Reader Supported News.

READ MORE  Three ambulances are parked in front of the emergency room at Children's Health of Orange County in California, November 1, 2022. (photo: Allen J. Schaben/LA Times)

Three ambulances are parked in front of the emergency room at Children's Health of Orange County in California, November 1, 2022. (photo: Allen J. Schaben/LA Times)

The typical measure of Americans without health insurance underreports how many people are going without coverage. Examining how many people go without insurance in a given year reveals that over 20 percent of Americans have gone uninsured in recent years.

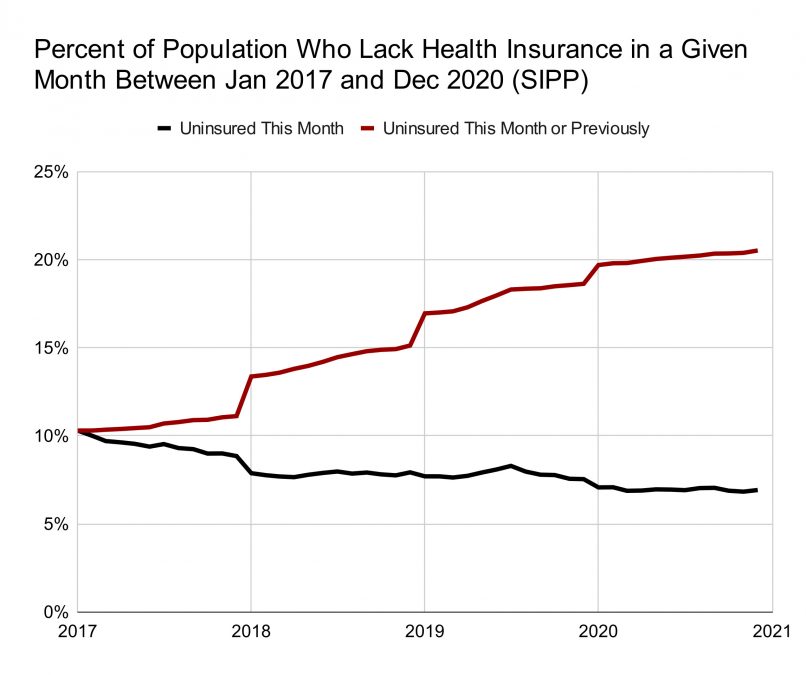

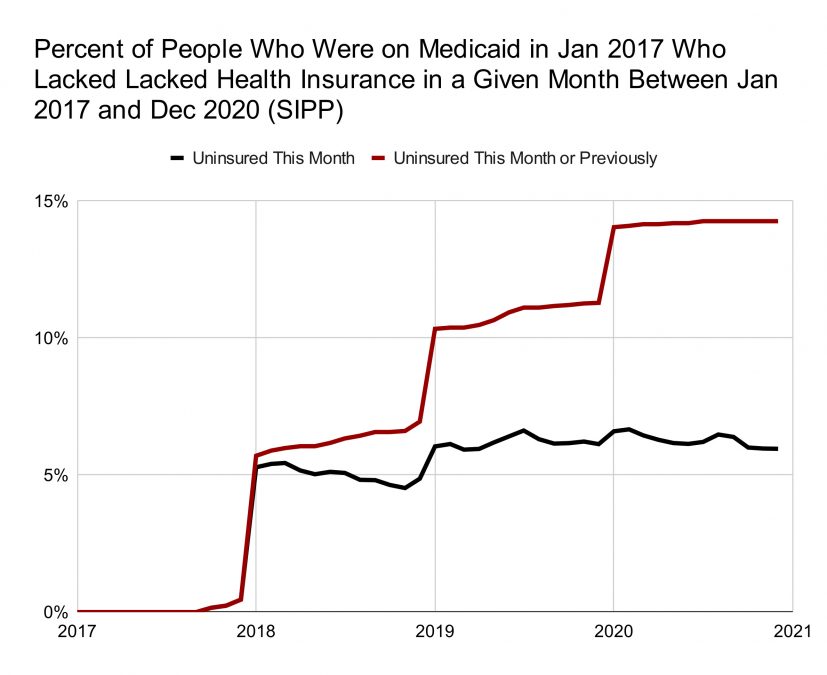

To illustrate this problem with PIT measures, I used the longitudinal Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) to determine what percent of the population was uninsured in any given month between January 2017 and December 2020 and what percent of the population was uninsured at any point between January 2017 and December 2020.

The black line is the PIT measurement that is most commonly reported. It shows that in a typical month, around 7 percent of the population is uninsured. The red line is the longitudinal measure and it shows that, over these four years, around 21 percent of the population was uninsured for at least one month. New uninsurance spells are most common in January of each year, which is what you would expect as health insurance plan years typically end in December.

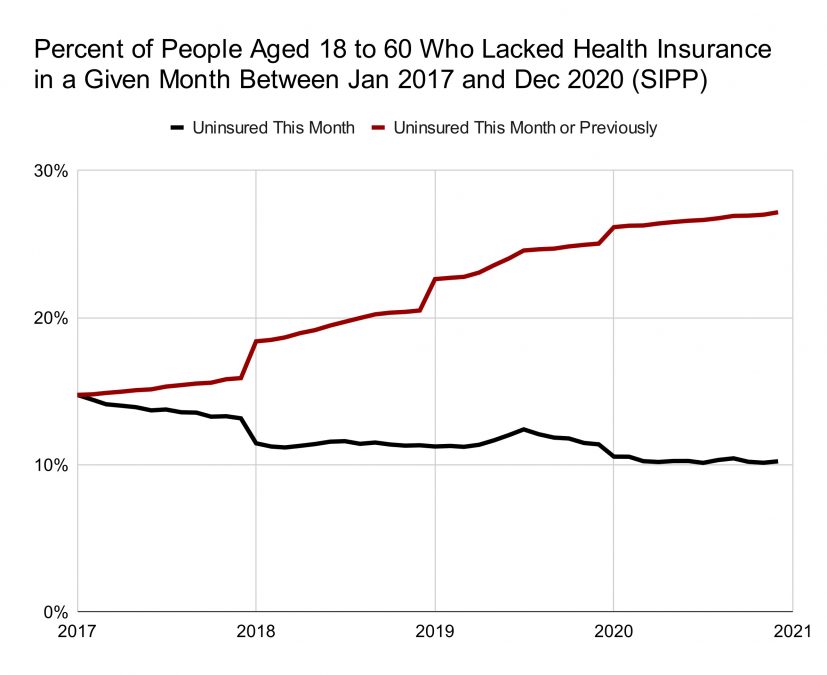

Here is the same graph but for non-elderly adults.

For non-elderly adults, around 27 percent were uninsured for at least one month between January 2017 and December 2020.

Finally, here is the same graph but for people who were on Medicaid in January 2017. Initially, this group has a 0 percent uninsurance rate because they are all on Medicaid. But over time, we can see that they also frequently experience uninsurance.

The Medicaid case is an interesting one because, in the health insurance discourse, you frequently hear people say that people on Medicaid are already covered and so various reform efforts would not be beneficial to them. But, as we can see above, this is not true. Today’s Medicaid recipient is tomorrow’s uninsured person. In fact, today’s Medicaid recipient goes on to hold all kinds of insurance statuses in the future.

In general, policy makers and policy commentators frequently fall into the trap of looking at cross-sectional data and assuming that population categories are much more static than they really are. Yesterday’s uninsured are not today’s uninsured and today’s uninsured are not tomorrow’s uninsured. The same is true for the unemployed, the poor, and many other similar groups.

When you patch up the overall system so as to reduce, eliminate, or ameliorate certain economic statuses, the number of people this helps is not the number of people who are in that status at any given point in time. It’s vastly larger than that.

READ MORE  Breonna Taylor. (photo: Breonna Taylor’s Family/AP)

Breonna Taylor. (photo: Breonna Taylor’s Family/AP)

For many, Garland’s announcement and the brutalities uncovered in the investigation are likely to be met with myriad emotions. On one hand, the immediate response is one of anger and frustration that after all of the body cam footage, all of the marches, the hashtags, and harrowing cell phone footage we are again reminded of just how broken American policing is at the systemic level. At the same time, the investigation results may be unsurprising to many who have been paying attention to the LMPD in the years following Taylor’s death. Of greatest concern, however, might be a sense of apathy for many about what happens next. Garland’s press conference also announced that LMPD will enter into a court-enforceable consent decree containing various provisions and mandates for LMPD to be overseen by an independent monitor to ensure compliance. During Democratic administrations, these consent decrees have been a typical federal response to pattern and practice abuses, which raises questions around whether this latest one will yield any sustainable culture change within a police department littered with systemic problems.

We’ve seen this movie before and the results of police department consent decrees remain mixed. In New Orleans, for example, a DOJ investigation resulted in a similar consent decree after a series of officer-involved shootings and dubious investigations. The consent decree created a degree of accountability where none had previously existed and led to legitimate more legitimacy in investigations of officer-involved shootings. Likewise, following the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, a DOJ investigation into the police also found widespread abuse and patterns of racial discrimination against Blacks. Again, a consent decree was entered and six-years later the once all-white police department has a greater number of Black officers within its force, more training, and a greater level of accountability through new vehicles to process citizen complaints. But, there have also been less successful stories involving consent decrees and police departments. For example, in the years following a similar agreement in Albuquerque entered n 2014 community members remain critical of a lack of progress and skeptical of the cost to the city.

The truth is consent decrees can only go as far as the mandates contained within and only as long as the duration of the agreement itself. Success is often measured by the benchmarks of how much more training is offered, increased percentages of minority hires, and new systems for complaint review and investigations. It is difficult to actually bring down the number of citizen complaints, and equally as challenging to gauge whether the increased training results in the culture change it intends to affect. While consent decrees often impose hard boundaries for improvement, addressing the mindset of officers in a way that helps to chart real culture change is a much harder task. Critically, the Trump administration—and particularly Jeff Sessions’ Department of Justice—showed how easy it is for adversarial Republican presidents to block the progress of new consent decrees and short-circuit existing ones. All it will take is for Ron DeSantis or Donald Trump to win the presidency in 20 months and Louisville could be right back where it started.

Ultimately, an essential element of culture change within any organization is accountability. Even as consent decrees can be effective in creating accountability where none may have previously existed, the judge-concocted doctrine of qualified immunity still remains a significant barrier in holding officers responsible for wrongdoing and providing individual victims in communities substantive redress when their rights have been violated. In Louisville, for example, even as systemic racism was found to exist, the DOJ report was silent on identifying specific officers who would be held liable for various civil rights offenses, including calling Black people in the city “monkey” and “boy.” Such outrages are not issues that result from a lack of training and are indicative of a mindset that is hard to uproot. If this feels familiar, it is because it is. The pattern or practice determination in Garland’s report is the most significant declaration of its kind, but falls short in this familiar way. Even in Ferguson, the DOJ failed to identify any individual actors as responsible, ultimately leaving community members to try to figure out how to transform a declaration of system-wide abuse into tangible remedies.

Three years after the horrific killing of Breonna Taylor, the problem of systemic abuses in policing in America remain a fundamental threat to our democracy and must be corrected. Beyond increased training and citizen complaint boards, this imperative beckons a shift from the current police culture of violence and aggression to a true public safety model. Culture change, in any organization, occurs first through leadership and is then maintained through accountability. The penchant to rely on consent decrees as a catalyst in stimulating that culture change is a step in the right direction, but doesn’t go nearly far enough.

READ MORE Contractors cleaning up and testing Sulphur Run, a creek that runs from the derailment site through the center of East Palestine, Ohio, March 3, 2023. (photo: Rebecca Kiger/WP)

Contractors cleaning up and testing Sulphur Run, a creek that runs from the derailment site through the center of East Palestine, Ohio, March 3, 2023. (photo: Rebecca Kiger/WP)

Rather than linking the East Palestine, Ohio, train derailment disaster to a national culture of impunity for corporations and disregard for working-class people, the Right is stoking racial animosity.

But they’ve got it backward. In reality, the abandonment of East Palestine residents is something with which black and brown working-class communities across the country are all too familiar. Rather than accentuating their differences, the story actually highlights an experience that working-class people have in common: when profit-hungry and unscrupulous corporations dump toxic waste into communities, nobody comes to their rescue, harm is never fully redressed, and the perpetrators are rarely held accountable.

On February 14, Tucker Carlson told his viewers that because East Palestine is “overwhelmingly white and politically conservative” the federal government and the media don’t have much concern for the health of the people living there. “Imagine if this happened in, well, the favored cities of Philadelphia and Detroit,” he opined, “In both cases, had it affected the rich or the favored poor, it would be the lead of every news channel in the world.”

Turning Point USA founder Charlie Kirk went a bit further and, flirting with the white nationalist “Great Replacement” theory, implied that Democrats actually prefer for white working-class people to be made sick by industrial pollution:

For the last couple of years, I have been warning about this crusade against white people. And people shrug their shoulders, say, oh, Charlie, why does that matter? I could tell you why it matters — when there is a crisis now and the leaders hate working-class whites, they’re not going to scramble to save your life. They’ll lie to you and tell you to go back home while you’re poisoned.

There was some media coverage when Norfolk Southern’s train first derailed in East Palestine, but it wasn’t until it became a story of corporate malfeasance and environmental harm that national outlets paid real attention. The state and federal government’s response was also a bit underwhelming, with residents complaining about a lack of information and resources, insufficient coordination between agencies, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) not sending aid until two weeks after the derailment.

Carlson, Kirk, and others claim that federal aid and media attention would have come quicker if the victims had been black. Kirk proclaimed that if the train had derailed in a black neighborhood, “It would be Flint water crisis 2.0.” But that’s just it: the disaster in Flint, Michigan didn’t get national media coverage until nearly a year after residents found lead in their water. FEMA didn’t get involved until almost two years had passed.

East Palestine is not a victim of reverse racism. It’s a victim of corporate greed and politicians’ complicity in railroad companies offloading the human cost of their profits onto people who can’t fight back. Working-class black and brown people don’t get special treatment when this happens in their communities. In fact, the tune of abandonment in the face of environmental injustice is one they know by heart.

A Product of Their Environment

Apparently, Kirk and Carlson aren’t aware that Flint 2.0 has been happening in the majority-black city of Jackson, Mississippi since August of last year, when heavy rain and flooding knocked pumps offline, leaving 150,000 residents without running water. A year prior, a severe winter storm had done the same. The media response to Jackson has been pretty similar to East Palestine — both got some, and both deserved far more.

Jackson’s water system has endured serious neglect for nearly a century. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) first reported elevated lead levels in the drinking water in 2015, and since then officials have issued constant boil notices and warnings for pregnant people and children not to drink tap water. After this recent disruption in service, federal and state aid was delivered and faucets started flowing again, but the water remains unsafe.

Lead poisoning does not discriminate based on race, but decades of discriminatory housing practices have created a situation in which black children in poverty are twice as likely to have elevated lead levels than poor white children. Conservatives have long blamed the racial disparities in educational and economic outcomes on a “culture of poverty,” when issues like lead poisoning make it clear that political choices concentrate minorities in environments that are harmful to childhood development. With the exception of high-profile cases like Flint and to a lesser extent Jackson, there has been little attention toward addressing this problem.

The state of Jackson’s water system troubles are a direct result of white flight from the majority-black city driving disinvestment, a Republican-controlled state legislature seemingly hell-bent on preventing the city from accessing federal relief funds, and Wall Street and private companies looking to extract profit from calamity. The result of this combination is often called environmental racism, and there’s no question that it is — though as East Palestine shows, sometimes working-class white communities end up in similar circumstances.

Down in the Dumps

Environmental racism refers to the disproportionate concentration of man-made environmental hazards in non-white communities, as well as indifference toward those communities when natural disaster strikes. Lead poisoning from dilapidated water infrastructure isn’t the only way that working-class people of color pay for company profits with their health. Last year, for example, three executives from Gold Coast Commodities were charged with illegally dumping industrial waste into the Jackson sewer system from processing used cooking oil and animal fat.

In Cheraw, South Carolina, where 53 percent of residents are black, a textile plant routinely dumped cancer-causing chemicals until the 1970s, with no public knowledge of the practice until a hurricane brought toxic water from the rivers into people’s homes and public spaces. Cheraw remains an EPA superfund site to this day.

In St Gabriel, Louisiana, chemical companies have been setting up shop for decades, creating the stretch of land now known as cancer alley — so-called because the majority-black population there is 50 percent more likely to develop cancer than the rest of the nation.

Sugarcane producers in Pahokee, Florida create “black snow” every October when they burn their crops before harvest. The practice makes harvesting easier for growers, as they can burn away everything but the valuable sugar cane. It also leaves the majority-black population of Pahokee to contend with heavily polluted air and water that cause respiratory illnesses and other ailments, as well as harming local wildlife.

Corporations tend to concentrate their hazardous industrial activities in poor neighborhoods, where residents have little means to fight back. Because racial segregation and marginalization have concentrated poverty in majority-minority areas, these hazards are disproportionately felt by people of color. But that doesn’t mean that industrial accidents never occur in majority-white municipalities.

In the majority-white town of Kingston, Tennessee, billions of gallons of extremely toxic coal ash burst from containment and spilled into a river channel. The responders who cleaned up the site experienced horrific health effects. Two years later the Tennessee Valley Authority decided to move the collected toxic material to the predominantly black city of Uniontown, Alabama, where under some legal maneuvering the coal ash was magically declared nontoxic.

Storing toxic waste from industrial accidents in low-income black communities is something of a tradition. When a company dumped cancer-causing chemicals along 240 miles of North Carolina highway in 1978, the state chose the poverty-stricken city of Warren to house the toxic material. This led to the Warren protests of 1982, which were ultimately unsuccessful in keeping the toxic dump away from residents but have since been seen as the birth of the environmental justice movement.

Toxic Divisions

Conservative punditry aside, there is growing evidence that federal aid for natural and man-made disasters has been disproportionately dispensed to white communities. But the prevalence of environmental racism and the preferential treatment of white disaster survivors does not mean the people of East Palestine don’t also deserve attention and help — far from it. They are victims of corporate greed, much like the victims of environmental racism. The task is for working-class people of all racial backgrounds to recognize their common vulnerability in the face of corporate pollution and government inaction.

Conservative commentators have blamed East Palestine on the Biden administration’s perceived deference to wokeness, but have said next to nothing about the administration’s deference to rail companies. In truth, the White House’s meager efforts to address environmental racism didn’t cause aid and media attention to be delayed to East Palestine. But its lax regulatory hand with rail companies, along with breaking a potential worker strike earlier this year, certainly helped create the conditions for such an industrial accident to happen.

The people of East Palestine shouldn’t view the victims of environmental racism as competition for a limited amount of aid and attention, but rather as fellow working-class people suffering from corporations prioritizing profit over the safety of those living near industrial operations. To really mount a serious challenge to the status quo, we must reject conservatives’ attempts to sow division and choose solidarity instead.

READ MORE  Plaintiffs Amanda Zurawski, Lauren Hall, Anna Zargarian, CRR President & CEO Nancy Northup, and CRR Media Relations Director Kelly Krause at the Texas State Capitol after filing a lawsuit on behalf of Texans harmed by the state’s abortion ban, on March 7, 2023 in Austin, Texas. (photo: Rick Kern/Center for Reproductive Rights)

Plaintiffs Amanda Zurawski, Lauren Hall, Anna Zargarian, CRR President & CEO Nancy Northup, and CRR Media Relations Director Kelly Krause at the Texas State Capitol after filing a lawsuit on behalf of Texans harmed by the state’s abortion ban, on March 7, 2023 in Austin, Texas. (photo: Rick Kern/Center for Reproductive Rights)

Doctors in red states across the country are too scared to perform legal abortions. A Texas lawsuit seeks to fix that in the biggest red state.

Texas is famously one of the most anti-abortion states in the country — you may remember the Supreme Court fight over the 2021 Texas law that sics litigious bounty hunters on abortion providers — but even in Texas, it is legal for doctors to perform an abortion when one is necessary to protect the health or life of a patient.

Or, at least, it is supposed to be legal.

Before the new lawsuit was filed, stories about patients who suffered because they were unable to obtain abortions were already common. One Texas woman had a nonviable pregnancy that risked giving her a life-threatening infection, and was told she had to wait, as her body discharged blood clots and a strange-smelling yellow liquid, until she became sick enough to have an abortion. Her doctors eventually agreed to induce labor after her vagina started to emit a dark, foul-smelling fluid.

Another Texas woman, whose fetus had multiple defects that would prevent it from living more than a few minutes after birth, says she had to flee to New Mexico to receive an abortion that would protect her from blood clots, cancer, and a potentially fatal condition known as preeclampsia. Her doctor later warned her not to get pregnant again in the state of Texas.

Nor are these kinds of stories limited to Texas. Similar stories abound in states like Tennessee, Louisiana, and Idaho, which also have very strict abortion laws.

In theory, even after the Supreme Court’s anti-abortion decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022), medically necessary abortions remain legal in all 50 states. Texas law, for example, is supposed to permit abortions when a patient is “at risk of death” or if they face “a serious risk of substantial impairment of a major bodily function.”

There’s also a federal law, the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA), which requires most hospitals to perform emergency abortions to prevent “serious impairment to bodily functions” or “serious dysfunction of any bodily organ or part.” (Though, notably, Texas’s GOP attorney general, Ken Paxton, convinced a Trump-appointed judge to issue an opinion claiming that this federal abortion protection does not exist.)

But in practice, the new lawsuit claims, Texas physicians are often too terrified to perform likely legal abortions because the consequences of performing an abortion that the courts later deem to be illegal are catastrophic. The maximum penalty for performing an illegal abortion in Texas is life in prison.

This lawsuit, known as Zurawski v. Texas, asks the state courts to clarify when medically necessary abortions are legal within the state so that doctors can know when they can treat their patients without risking a prison sentence or a lawsuit.

Represented by lawyers from private firms and the Center for Reproductive Rights, an abortion-rights litigation powerhouse, the Zurawski plaintiffs ask the courts to clarify that Texas law “permits physicians to provide a pregnant person with abortion care when the physician determines, in their good faith judgment and in consultation with the pregnant person, that the pregnant person has a physical emergent medical condition that poses a risk of death or a risk to their health (including their fertility).”

The suit, in other words, asks the courts to lift a cloud of uncertainty that hangs over Texas doctors, preventing them from treating their patients even when that treatment is legal.

The Zurawski lawsuit, briefly explained

The plaintiffs in Zurawski are five women who, because they struggled to find abortion care in Texas, say that they suffered harrowing and unnecessary medical crises.

Amanda Zurawski, for example, alleges that she was forced to continue a pregnancy until she developed sepsis, a life-threatening medical condition, even though her doctors determined days earlier that her fetus would not survive. At one point, Zurawski’s family flew to Austin to be by her side because they were unsure if she would survive.

Though she eventually received an abortion, Zurawski developed severe scar tissue on her uterus and fallopian tubes. One of her fallopian tubes is now permanently closed.

Another plaintiff, Anna Zargarian, says she was forced to fly to Colorado to obtain an abortion after her water broke prematurely and her doctors told her the fetus could not survive. A third plaintiff, Lauren Hall, alleges she had to fly to Seattle to see a specialist, at great cost to her family, after she learned that her fetus had not developed a skull and would not survive. Her doctors told her that, if she did not terminate the pregnancy, she was at risk for many medical conditions, including hemorrhage.