Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

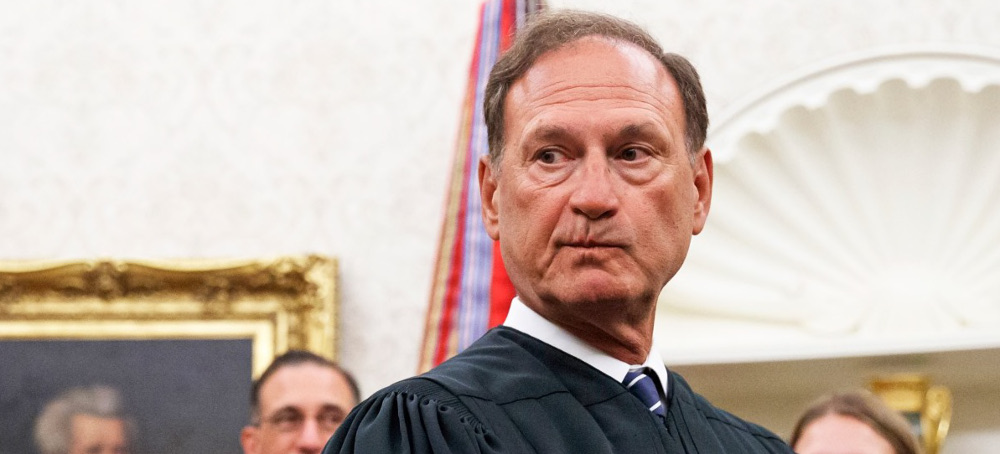

It took Justice Samuel Alito barely a month to violate them.

In the court’s orders list on Tuesday, Alito noted his recusal from BG Gulf Coast and Phillips 66 v. Sabine-Neches Navigation District—a case about two energy companies shirking their obligation to help fund improvement of a waterway that they use for shipping. (The court declined to take up the case, leaving in place a lower court decision against the companies.) But the justice did not explain his reason for recusing, one of Roberts’ promised “practices.” To obtain that information, you must dig through his financial disclosures, which reveal that he holds up to $50,000 of stock in Phillips 66, one of the parties. Alito is one of two sitting justices who still holds individual stocks (as opposed to conflict-free assets like mutual funds). The only other sitting justice who maintains investments in individual stock is Roberts himself.

For years, Alito has periodically recused from cases involving energy companies without explaining why. This spring, however, that practice was supposed to change. Roberts’ ethics “statement” explained that justices “may provide a summary explanation of a recusal decision” with a citation to the relevant provision of the Judicial Code of Conduct. (That code is binding on lower court judges but voluntary for the justices.) The “statement” offered this example: “Justice X took no part in the consideration or decision of this petition. See Code of Conduct, Canon 3C(1)(c) (financial interest).”

In Philips 66, it appears that Alito should have cited his “financial interest” in a party to explain his “recusal decision.” (In other words, he should have been “Justice X.”) This could have been a textbook example of the new rule in action; indeed, it was literally the example that the court offered the Senate Judiciary Committee. Instead, Alito refused to adhere to this new procedure.

His decision is all the more brazen given that Justice Elena Kagan debuted the new rule just last week. In recusing from a case, Kagan cited her “prior government employment,” a shorter way of saying that she participated in the proceedings while serving as solicitor general. This move provided some basis to hope that the court really had begun to embrace a modicum of transparency (albeit by doing the bare minimum). As Leah Litman pointed out on the Strict Scrutiny podcast, though, Kagan was never the problem: She has long complied voluntarily with the Judicial Code of Conduct, so much so that she once turned away a gift of free bagels and lox from high school friends. The real question was whether any justices at the center of the ethics maelstrom would follow through on the promises of the court’s “statement.” It seems the answer is no.

Which is, of course, the entire problem with the unenforceable ethics guidelines that the chief justice offered up to the Senate Judiciary Committee in place of an actual code. The “statement” declares at the outset that it contains “foundational ethics principles and practices”; you might assume that if an ethics principle is “foundational,” then every justice should feel compelled to follow it. Yet the guidelines use voluntary language throughout, hedging at every turn to avoid committing the justices to any explicit mandate. For example, the recusal provision at issue in Phillips 66 contains a hazy qualification that “in some cases, public disclosure of the basis for recusal would be ill-advised,” giving the example of “circumstances that might encourage strategic behavior by lawyers who may seek to prompt recusals in future cases.”

Whatever that hedge means, it surely does not apply here. Alito either owns stock in a party or he doesn’t, making recusals straightforward and difficult to game. But the justice’s defenders might cite that qualification—which is ambiguous to the point of meaninglessness—in his defense.

That leads to a deeper problem: The justices who commit the most ethics violations are also the least likely to follow voluntary ethics guidelines. Alito has made it clear that he thinks ethics are for chumps. The justice stands accused of leaking the decision in 2014’s Hobby Lobby to anti-abortion activists who infiltrated the Supreme Court Historical Society. Alito has delivered inappropriate public remarks swinging back at critics in the press and academia. And his track record on recusal has been spotty at best, with the justice either overlooking conflicts of interest or changing his mind about them: In 2014, for instance, the justice recused then un-recused himself from two cases without offering a word of explanation, and has failed to recuse in several cases since, despite owning stock in a party.

An ethics “statement” that does not bind Alito—or Clarence Thomas, or any other justice who holds the arrogant conviction that they have a right to do anything they want in total secrecy—is worse than useless. It creates the false impression that every member of the court is committed to the same rulebook, which in turn suggests that Congress has no need to impose an actual, enforceable code of ethics on SCOTUS. Roberts’ “statement” was designed to persuade us that the court could be trusted to keep its own affairs aboveboard. Barely a month later, it is already proving the opposite.

READ MORE  The Mountain Valley Pipeline would stretch 303 miles, from West Virginia to North Carolina. This 2018 file photo shows a section of downed trees on a ridge near homes along the pipeline's route in Lindside, W.Va. (photo: Steve Helber/AP)

The Mountain Valley Pipeline would stretch 303 miles, from West Virginia to North Carolina. This 2018 file photo shows a section of downed trees on a ridge near homes along the pipeline's route in Lindside, W.Va. (photo: Steve Helber/AP)

The Fiscal Responsibility Act orders expedited approval of all permits needed to complete the pipeline, which has been opposed by climate and conservation groups as well as local residents along its path. Backers of the plan say it would boost U.S. energy infrastructure and jobs in Appalachia and the Southeast.

The Mountain Valley Pipeline would stretch 303 miles, from West Virginia to North Carolina. But it would cut through the Jefferson National Forest and cross hundreds of waterways and wetlands — and legal battles have held up those crucial sections of the pipeline have been held up for years.

In an extraordinary move, the federal measure would also quash lawsuits against the pipeline project and send any new appeals to the D.C. Circuit rather than the Fourth Circuit, which has regional jurisdiction and which has blocked numerous permits.

The House approved the legislation Wednesday; it now heads to the Senate.

Here's a quick recap of where things stand with the pipeline:

Pipeline approval would fulfill Biden's promise to Manchin

The Fiscal Responsibility Act devotes fewer pages to the debt ceiling than it does to the pipeline, a longtime cause for Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia — who holds a critical vote in a closely divided Senate — and Republicans from his state.

Manchin receives three times as much money from pipeline companies as any other member of Congress, according to Open Secrets.

Last year, Manchin secured a promise from the Biden administration to fast-track the pipeline's completion in exchange for his support of President Biden's climate spending bill.

The Equitrans Midstream Corporation, which is managing the pipeline's development and would operate it, recently told shareholders it would likely get all permits approved and have the pipeline ready for operation by the end of 2023, with a total cost of some $6.6 billion.

Manchin says the pipeline also means big money for his state.

"I've been told it's about $40 million a year in tax revenues to the state of West Virginia," he said, according to West Virginia Public Broadcasting. "And about $300 million a year in revenue to the royalty owners."

The act shifts legal jurisdiction for court approval

When Manchin brokered the 2022 deal with the White House, his office said it planned to "give the D.C. Circuit jurisdiction over any further litigation," rather than the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Richmond, Va., where judges have repeatedly ruled against the pipeline.

The debt ceiling deal would fulfill that plan. The act states, "no court shall have jurisdiction to review any action taken by the Secretary of the Army, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the Secretary of Agriculture, the Secretary of the Interior," or any state agency, if the action authorizes or permits building and operating the pipeline at full capacity.

The legislation also says the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit "shall have original and exclusive jurisdiction over any claim alleging the invalidity of this section or that an action is beyond the scope of authority conferred by this section."

Rep. Garret Graves of Louisiana, who led Republicans' negotiations with the White House over the debt ceiling, called the deal a GOP victory, saying Democrats are now on the record "supporting a conventional energy project that removes or ties the hands of the judiciary," according to The Washington Post, citing a conference call with reporters.

Climate groups say pipeline isn't needed and is harmful

By approving the Fiscal Responsibility Act, Congress would declare that "the timely completion of construction and operation of the Mountain Valley Pipeline is required in the national interest."

The American Exploration and Production Council, a lobbying group for oil and gas producers, hailed the deal, with CEO Anne Bradbury saying in an email to NPR that by approving the pipeline and promising changes to the permitting system, a bureaucratic process will become more streamlined.

But the Natural Resources Defense Council disagrees, saying the new deal would remove key avenues for legal and environmental review. It also says that much of the official narrative about the pipeline is false — despite claims by Manchin and others, the group says, the pipeline isn't needed and still faces important legal hurdles.

The League of Conservation Voters is also against the pipeline's inclusion in the debt deal. In an email to NPR, the group's Tiernan Sittenfeld, senior vice president of government affairs, said that by forcing approval of the pipeline, the debt deal "locks in decades of climate pollution, threatens water quality, and jeopardizes communities in West Virginia, Virginia, and North Carolina, especially low-income, elderly, Indigenous, and Black communities."

The debt deal has critics on the left and right

Some of the most conservative House members are furious with House Speaker Kevin McCarthy over the the debt ceiling deal, saying it gives Democrats too many concessions and doesn't go far enough in reaching Republican goals.

Some progressive Democrats are also unhappy, saying the Biden administration isn't delivering on its promises to support clean energy rather than fossil fuels, along with allowing cuts or restrictions to food programs and other assistance for vulnerable Americans.

Critics are also asking why the debt deal legislation, which runs to 99 pages, devotes so much space to other matters, like revamping the federal permitting process under the National Environmental Policy Act.

When asked about those concerns, Office of Management and Budget Director Shalanda Young said on Tuesday, "I've worked in many divided government situations. I think this is where you would expect a bipartisan agreement to land. It's just the reality."

READ MORE  Guarani Indigenous block Bandeirantes highway to protest proposed legislation that would change the policy that demarcates Indigenous lands on the outskirts of Sao Paulo. (photo: Ettore Chiereguini/AP)

Guarani Indigenous block Bandeirantes highway to protest proposed legislation that would change the policy that demarcates Indigenous lands on the outskirts of Sao Paulo. (photo: Ettore Chiereguini/AP)

The fast-track approval highlights the strength of Brazil's powerful agriculture industry. Indigenous leaders vow more protests.

The law sailed through Brazil's lower house of Congress late Tuesday and is expected to pass the Senate. Among its provisions, it will limit the creation of new Indigenous reserves to lands that were only occupied by native people in 1988. That's the promulgation date of Brazil's latest constitution.

Indigenous leaders blocked a major highway in protest of the proposed legislation. Many held signs saying "we existed before 1988." They clashed with police, using bows and arrows at security forces, who dispersed the crowd with water cannons and tear gas.

Opponents of the law say many tribes were expelled from their lands during Brazil's military dictatorship, which ended in 1985, and they hadn't returned to lands until years later.

There are 764 Indigenous territories located in Brazil, but more than 300 have yet to be officially demarcated and remain in legal limbo. Most are located in the Amazon and are considered key buffers against deforestation.

President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva recognized six new territories back in April. He has vowed to protect Indigenous rights and reverse years of rainforest destruction. Under the previous far-right administration of President Jair Bolsonaro, Indigenous land demarcation had stalled.

Lula created a new Ministry of Indigenous Peoples. Its minister, Sonia Guajarara, called the new bill a "genocide against Indigenous peoples" as well as an "attack on the environment."

Brazil's critical agricultural industry made big gains in last year's election and the sector's allied conservative lawmakers are backing the proposal. The bill now goes to the Senate for a vote where the agriculture lobby has strong support and possibly could override a presidential veto.

READ MORE  The eye of a hippopotamus seen at Bioparque Wakata in Jaime Duque park, near Bogota, Colombia. (photo: Raul Arboleda/AFP)

The eye of a hippopotamus seen at Bioparque Wakata in Jaime Duque park, near Bogota, Colombia. (photo: Raul Arboleda/AFP)

A flood of new research is overturning old assumptions about what animal minds are and aren’t capable of – and changing how we think about our own species

In repeated trials, the four test giraffes reliably chose the hand that had reached into the container with more carrots, showing they understood that the more carrots were in the container, the more likely it was that a carrot had been picked. Monkeys have passed similar tests, and human babies can do it at 12 months old. But giraffes’ brains are much smaller than primates’ relative to body size, so it was notable to see how well they grasped the concept.

Such discoveries are becoming less surprising every year, however, as a flood of new research overturns longstanding assumptions about what animal minds are and aren’t capable of. A recent wave of popular books on animal cognition argue that skills long assumed to be humanity’s prerogative, from planning for the future to a sense of fairness, actually exist throughout the animal kingdom – and not just in primates or other mammals, but in birds, octopuses and beyond. In 2018, for instance, a team at the University of Buenos Aires found evidence that zebra finches, whose brains weigh half a gram, have dreams. Monitors attached to the birds’ throats found that when they were asleep, their muscles sometimes moved in exactly the same pattern as when they were singing out loud; in other words, they seemed to be dreaming about singing.

In the 21st century, findings such as these are helping to drive a major shift in the way human beings think about animals – and about ourselves. Humanity has traditionally justified its supremacy over all other animals – the fact that we breed them and keep them in cages, rather than vice versa – by our intellectual superiority. According to Aristotle, humans are distinguished from other living things because only we possess a rational soul. We know our species as Homo sapiens, “wise man”.

Yet at a time when humanity’s self-image is largely shaped by fears of environmental devastation and nuclear war, combined with memories of historical atrocity, it is no longer so easy to say, with Hamlet, that man is “the paragon of animals” – the ideal that other creatures would imitate, if only they could. Nature may be “red in tooth and claw”, but creatures whose weapons are teeth and claws can only kill each other one at a time. Only humans commit atrocities such as war, genocide and slavery – and what allows us to conceive and carry out such crimes is the very power of reason that we boast about.

In his 2022 book If Nietzsche Were a Narwhal, Justin Gregg, a specialist in dolphin communication, takes this mistrust of human reason to an extreme. The book’s title encapsulates Gregg’s argument: if Friedrich Nietzsche had been born a narwhal instead of a German philosopher, he would have been much better off, and given his intellectual influence on fascism, so would the world. By extension, the same is true of our whole species. “The planet does not love us as much as we love our intellect,” Gregg writes. “We have generated more death and destruction for life on this planet than any other animal, past and present. Our many intellectual accomplishments are currently on track to produce our own extinction.”

If human minds are incapable of solving the problems they create, then perhaps our salvation lies in encountering very different types of minds. The global popularity of the documentary My Octopus Teacher, released by Netflix in 2020, is just one example of the growing hunger for such encounters. In the film, the South African diver Craig Foster spends months filming a female octopus in an underwater kelp forest, observing most of her lifecycle. Foster presents himself as the anti-Jacques Cousteau; he doesn’t go underwater to study the non-human, but to learn from it.

Humility is a traditional religious discipline, and there is a spiritual dimension to Foster’s quest and to the film’s success. On YouTube, where the trailer has been viewed 3.7m times, thousands of people testify that My Octopus Teacher made them weep, changed their understanding of the world and made them resolve to lead better lives. It’s clear that, for modern people who seldom encounter animals except for pet cats and dogs, entering into a close relationship with a non-human mind can be a sacred experience.

The idea of the octopus as the nonhuman mind par excellence was popularised by the 2016 bestseller Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness, by Peter Godfrey-Smith. A philosopher rather than a marine biologist, Godfrey-Smith got an opportunity to see the creatures in action at a site off eastern Australia known to researchers as Octopolis. There he discovered that octopuses are “smart in the sense of being curious and flexible; they are adventurous, opportunistic”, prone to making off with items such as tape measures and measuring stakes.

The fascination of the octopus is that while its behaviour seems recognisable in human terms as mischief or curiosity, its neural architecture is immensely different from ours. Since Darwin, humans have grown used to recognising ourselves in our fellow primates, whose brains and body plans are similar to our own. After all, humans and chimpanzees share a common ape ancestor that lived in Africa as recently as 6m years ago. Our most recent common ancestor with the octopus, by contrast, is a worm-like creature thought to have lived 500-600m years ago.

Because the mind of the octopus evolved in a completely different fashion from ours, it makes sense of the world in ways we can barely imagine. An octopus has 500m neurons, about as many as a dog, but most of these neurons are located not in the brain but in its eight arms, each of which can move, smell and perhaps even remember on its own. In Godfrey-Smith’s words, an octopus is “probably the closest we will come to meeting an intelligent alien”. When such a being encounters a human at the bottom of the ocean, what could it possibly make of us?

For most of the 20th century, animal researchers wouldn’t even have asked such a question, much less attempted to answer it. Under the influence of the American psychologist BF Skinner, scientific orthodoxy held that it was neither legitimate nor necessary to talk about what was going on in an animal’s mind. Science, he argued, only deals with things that can be observed and measured, and we can’t directly observe mental faculties even in ourselves, much less in animals. What we can observe is action and behaviour, and Skinner was able to modify the behaviour of rats using positive reinforcement, such as rewards of food, and negative reinforcement, such as electric shocks.

When Jane Goodall first went to study chimpanzees in Tanzania in the 1960s, the very notion of animal subjectivity was taboo. Her practice of giving names to the individual chimps she observed – such as David Greybeard, who her studies made famous – was frowned on as unscientific, since it suggested that they might be humanlike in other ways. The standard practice was to number them. “You cannot share your life with a dog or a cat,” Goodall later observed, “and not know perfectly well that animals have personalities and minds and feelings. You know it and I think every single one of those scientists knew it, too, but because they couldn’t prove it, they didn’t talk about it.”

Today, the pendulum has swung in the other direction. Scientists speak without embarrassment about animal minds and consciousness. In popular writing on the subject, Skinner appears only as a villain. In his 2016 book Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are?, primatologist Frans de Waal discusses a mid-20th-century experiment in which researchers at a primate centre in Florida, educated in Skinner’s methods, tried to train chimps the way he had trained rats, by withholding food. “Expressing no interest in cognition – the existence of which they didn’t even acknowledge,” De Waal writes, the researchers “investigated reinforcement schedules and the punitive effect of time-outs.” The staff of the primate centre rebelled and started feeding the chimps in secret, causing Skinner to lament that “tender-hearted colleagues frustrated efforts to reduce chimpanzees to a satisfactory state of deprivation”. You could hardly ask for a better example of how the arrogance of reason leads to cruelty.

Meanwhile, animals without “rational souls” are capable of demonstrating admirable qualities such as patience and self-restraint. Among humans, the ability to sacrifice immediate pleasure for future gain is called resisting temptation, and is taken as a sign of maturity. But De Waal shows that even birds are capable of it. In one experiment, an African grey parrot named Griffin was taught that if he resisted the urge to eat a serving of cereal, he would be rewarded after an unpredictable interval with food he liked better, such as cashew nuts. The bird was able to hold out 90% of the time, devising ways to distract himself by talking, preening his feathers, or simply throwing the cup of cereal across the room. Such behaviours, De Waal notes, are quite similar to what human children do in the face of temptation.

More intriguing than the convergences between human and animal behaviour, however, are the profound differences in the way we perceive and experience the world. The reason why an encounter with an octopus can be awe-inspiring is that two species endowed with different senses and brains inhabit the same planet but very different realities.

Take the sense of smell. As humans, we learn about our surroundings primarily by seeing and hearing, while our ability to detect odours is fairly undeveloped. For many animals, the reverse is true. In his 2022 book An Immense World, the science journalist Ed Yong writes about an experiment by researcher Lucy Bates involving African elephants. Bates found that if she took urine from an elephant in the rear of a herd and spread it on the ground in front of the herd, the elephants reacted with bewilderment and curiosity, knowing that the individual’s distinctive odour was coming from the wrong place. For them, a smell out of place was as fundamental a violation of reality as a ghostly apparition would be for us.

Animals that perceive the world through scent, such as dogs, even have a different sense of time. We often talk about the importance of “living in the moment”, but in fact we have no other choice; since visual information reaches us at the speed of light, what we see around us are things as they existed an infinitesimal fraction of a second ago. When a dog smells, however, “he is not merely assessing the present but also reading the past and divining the future”, Yong writes. Odour molecules from a person or another dog can linger in a room long after the source is gone, or waft ahead before it appears. When a dog perks up long before its owner walks through the front door, smell can seem like a psychic power.

If giraffes can do statistical reasoning and parrots understand the concept of the future, then where does the distinctiveness of the human mind really lie? One favourite candidate is what psychologists call “theory of mind” – the ability to infer that each person is their own “I”, with independent experiences and private mental states. In The Book of Minds, the science writer Philip Ball describes the classic experiment that tests the development of this ability in children. A child and an adult watch as an object is hidden under one of three cups. Then the adult leaves the room and the child sees a second adult come in and move the object so it’s under a different cup.

When the first adult returns, where does the child expect she will look for the object? Very young children assume that she will know its new location, just as they do. Starting around age four, however, children start to understand that the adult only knows what she has seen herself, so they expect her to look under the original, now empty cup. “Indeed,” Ball writes, “they will often delight in the deception: in their knowing what others don’t.”

Developing a theory of mind is necessary because we can never know what is going on inside other people in the same immediate way we know ourselves. Sane adults take for granted that other people have the same kind of inner life they do, but this remains a kind of assumption. René Descartes was one of the first philosophers to wrestle with this problem, in the 17th century. “What do I see from the window but hats and coats which may cover automatic machines?” he asked. “Yet I judge these to be men.” But Descartes didn’t extend the same benefit of the doubt to animals. Even more than Skinner, he saw them as automata without any inner experience, “bêtes-machines”. Ball notes that Descartes dissected live animals to study the circulation of the blood, “and dismissed any cries of pain that procedure elicited as a mere mechanical response, not unlike the screech of a poorly oiled axle”.

Four centuries later, De Waal complains that science still hasn’t overcome the tendency to draw a dividing line between the inner lives of humans and those of other creatures. The reason that scientists have focused on theory of mind, De Waal believes, is because no animal has been shown to possess it. Such “interspecific bragging contests”, he writes, are designed to flatter our sense of superiority. In fact, it seems that even here we’re not clear winners. According to Ball, recent attempts to replicate the theory-of-mind experiment with chimps and bonobos suggest that the majority of them pass the test, though the evidence is ambiguous: since the subjects can’t talk, researchers gauge their expectations by tracking their eye movements.

Even if other species were conclusively found to possess a theory of mind, of course, it would not challenge our monopoly on the kind of “rational soul” that produced the pyramids and monotheism, the theory of evolution and the intercontinental ballistic missile. As long as these quintessentially human accomplishments remain our standard for intellectual capacity, our place at the top of the mental ladder is assured.

But are we right to think of intelligence as a ladder in the first place? Maybe we should think, instead, in terms of what Ball calls “the space of possible minds” – the countless potential ways of understanding the world, some of which we may not even be able to imagine. In mapping this space, which could theoretically include computer and extraterrestrial minds as well as animal ones, “we are currently no better placed than the pre-Copernican astronomers who installed the Earth at the centre of the cosmos and arranged everything else in relation to it”, Ball observes. Until we know more about what kinds of minds are possible, it is sheer hubris to set up our own as the standard of excellence.

Xenophanes, a pre-Socratic philosopher, observed that if horses and oxen could draw pictures, they would make the gods look like horses and oxen. Similarly, if non-human beings could devise a test of intelligence, they might rank species according to, say, their ability to find their way home from a distance unaided. Bees do this by detecting magnetic fields, and dogs by following odours, while most modern humans would be helpless without a map or a GPS. “Earth is bursting with animal species that have hit on solutions for how to live a good life in ways that put the human species to shame,” Gregg says.

But if human and animal minds are so essentially different that we can never truly understand one another, then a troubling thought arises: we would be less like neighbours than inmates who occupy separate cells in the same prison. The kind of understanding Foster achieved with his octopus, or Goodall with her chimpanzees, would have to be written off as an anthropomorphising illusion, just as Skinner warned.

The possibility of true interspecies understanding is the subject of Thomas Nagel’s landmark 1974 essay What Is It Like to Be a Bat?, to which every writer on animal cognition pays their respects, sometimes wearily. Nagel, an American philosopher, concluded that humans can never really understand a bat’s inner experience. Even if I try to picture what it’s like to fly on webbed wings and spend most of my time hanging upside down, all I can imagine is what it would be like for me to be a bat, not what it’s like for a bat to be a bat.

For Nagel, this conclusion has implications beyond animal psychology. It proves that mental life can never be reduced to things we can observe from the outside, whether that means the way we behave or the pattern of electrical impulses in our neurons. Subjectivity, what it feels like to exist, is so profoundly different from what we can observe scientifically that the two realms can’t even be described in the same language.

Few people have ever taken the challenge of Nagel’s essay as literally as Charles Foster in his 2016 book Being a Beast. A barrister and academic by profession, Foster set himself the challenge of entering the mental worlds of five animal species by living as much like them as possible. To be a fox, he writes: “I lay in a back yard in Bow, foodless and drinkless, urinating and defecating where I was, waiting for the night and treating as hostile the humans in the row houses all around.” To be a badger, he dug a trench in the side of a hill and lived inside it with his young son Tom, eating earthworms and inhaling dust. “Tom was filling tissues with silica and blood for a week,” Foster notes.

Foster welcomes all this damage and discomfort, but not in the spirit of a scientist doing fieldwork. Rather, he evokes the medieval flagellants who covered their backs with welts to purge themselves of sin. That Foster defines sin as a transgression against nature rather than God doesn’t make the concept any less religious. “Evolutionary biology is a numinous statement of the interconnectedness of things,” he writes, and his preaching translates easily into Christian terms: “Say, with Saint Francis, ‘Hello, Brother Ox,’ and mean it,” he demands.

Foster’s way of seeking communion with the animals may be extreme, at times comically so, but his basic impulse is shared by many of today’s students of animal cognition, and an increasing number of laypeople as well. Encountering an animal mind can perform the same function as a great work of art or a religious experience: it makes the familiar strange, reminding us that reality encompasses far more than we ordinarily think.

The great difference is that while a traditional religious experience can awaken human beings to God, an animal epiphany can awakens us to the fullness of this world. “What she taught me was to feel that you’re part of this place, not a visitor,” Foster says in the closing lines of My Octopus Teacher, and by “this place” he doesn’t just mean a particular kelp forest, but the Earth itself. At first this might sound like an odd realisation: where else would human beings belong if not on our one and only planet?

But in the 21st century, it is clearly becoming harder for us to think of ourselves as genuinely belonging to the Earth. Whether we look back on our long history of driving other species to extinction, or forward to a future in which we extinguish ourselves through climate breakdown, many humans now see humanity as the greatest danger facing the Earth – a cancer that grows without limit, killing its host.

It is no coincidence that, at the same moment, tech visionaries have begun to think about our future in extraterrestrial terms. Earth may be where humanity happened to evolve, they say, but our destiny calls us to other worlds. Elon Musk founded SpaceX in 2002 with the explicit goal of hastening humanity’s colonisation of Mars. Other “transhumanist” thinkers look forward to a fully virtual future, in which our minds leave our bodies behind and achieve immortality in the form of electromagnetic pulses.

These projects sound futuristic, but they are best understood as new expressions of a very old human anxiety. We have always suffered from metaphysical claustrophobia – the sense that a cosmos containing no minds but our own was intolerably narrow. That is why, since prehistoric times, humans have populated Earth with other kinds of intelligences – from gods and angels to fairies, forest-spirits and demons. All premodern cultures took the existence of such non-human minds for granted. In medieval Europe, Christian and Greek philosophical ideas gave rise to the doctrine of the “great chain of being”, which held that the universe is populated by an unbroken series of creatures, all the way from plants at the bottom to God at the apex. Humanity stood in the middle, more intelligent than the animals but less than the angels, who came in many species, with different powers and purviews.

Filling the universe with hypothetical minds, superior to our own in wisdom and goodness, helps relieve our species’ loneliness, giving us beings we could talk to, think about, and strive to emulate. Our need for that kind of company in the universe hasn’t gone away, though today we prefer to fill the region “above” us in the space of possible minds with advanced extraterrestrials and superpowered AIs – beings that are just as hypothetical as seraphim and cherubim, at least so far.

Our rising interest in animal minds can be seen as a way of filling in the regions “below” us as well. If an octopus is like an intelligent alien, as Godfrey-Smith writes, then we don’t need to scan the skies so anxiously for an actual extraterrestrial. Yong quotes Elizabeth Jakob, an American spider expert, to the same effect: “We don’t have to look to aliens from other planets … We have animals that have a completely different interpretation of what the world is right next to us.” Perhaps simply knowing that these other minds exist can help us make peace with the limitations of our own.

READ MORE US debt ceiling bill passes House with broad bipartisan support. (photo: Kenny Holston/The New York Times)

US debt ceiling bill passes House with broad bipartisan support. (photo: Kenny Holston/The New York Times)

With 149 Republicans and 165 Democrats supporting the measure, Biden has called on the Senate to quickly take up the legislation

The final House vote was 314 to 117, with 149 Republicans and 165 Democrats supporting the measure. In a potentially worrisome sign for the House Republican speaker, Kevin McCarthy, 71 members of his conference opposed the deal that he brokered with President Joe Biden.

Taking a victory lap after the bill’s passage, McCarthy downplayed concerns over divisions within the House Republican conference and celebrated the policy concessions he secured in his negotiations with Biden.

“I have been thinking about this day before my vote for speaker because I knew the debt ceiling was coming. And I wanted to make history. I wanted to do something no other Congress has done,” McCarthy told reporters after the vote. “Tonight, we all made history.”

Biden applauded the House passage of the legislation, calling on the Senate to quickly take up the legislation to avoid a default. The treasury secretary, Janet Yellen, has warned that the federal government will be unable to pay its bills starting 5 June unless it was allowed to borrow more.

“This budget agreement is a bipartisan compromise. Neither side got everything it wanted,” Biden said in a statement. “I have been clear that the only path forward is a bipartisan compromise that can earn the support of both parties. This agreement meets that test.”

The debt ceiling bill passed by the House would suspend the government’s borrowing limit until January 2025, ensuring the issue will not resurface before the next presidential election. As part of his negotiations with Biden, McCarthy successfully pushed for government spending cuts and changes to the work requirements for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

However, the concessions that McCarthy won fell far short for members of the Freedom caucus, who had pushed for steeper spending cuts and much stricter work requirements for benefits programs. They belittled the debt ceiling compromise as a paltry effort to tackle the nation’s debt, which stands at more than $31tn.

Representative Scott Perry of Pennsylvania, chair of the Freedom caucus, said on Twitter before the vote: “President Biden is happily sending Americans over yet another fiscal cliff, with far too many swampy Republicans behind the wheel of a ‘deal’ that fails miserably to address the real reason for our debt crisis: SPENDING.”

House Freedom caucus members staged one last attempt to block the debt ceiling bill from advancing on Wednesday afternoon, when they opposed a procedural motion prior to the final vote. With 29 Republicans voting against the motion, McCarthy had to rely on Democratic assistance to advance the debt ceiling proposal. In the end, 52 Democrats voted for the motion, setting up the final vote and virtually ensuring the bill’s passage.

The House Democratic leader, representative Hakeem Jeffries of New York, mocked McCarthy’s failure to unify his party, arguing the procedural vote proved the speaker has “lost control of the floor”.

“It’s an extraordinary act that indicates just the nature of the extremism that is out of control on the other side of the aisle,” Jeffries said during the floor debate before the final vote. “Extreme Maga Republicans attempted to take control of the House floor. Democrats took it back for the American people.”

Despite his sharp criticism of McCarthy and his Republican colleagues, Jeffries and the majority of the House Democratic caucus supported the debt ceiling bill. Although they lamented the spending cuts included in the bill, those Democrats argued the crucial importance of avoiding a default outweighed their personal concerns about the legislation.

“Our constitution makes perfectly clear the validity of the public debt of the United States shall not be questioned,” said California representative Nancy Pelosi, the former Democratic House speaker. “While I find this legislation objectionable, it will avert an unprecedented default, which would bring devastation to America’s families.”

But dozens of progressive lawmakers opposed the bill, attacking the spending cuts and new work requirements procured by McCarthy as an affront to the voters who elected them.

“Republicans never cared about reducing the deficit, only about forcing through their anti-working family policy priorities under the threat of a catastrophic default,” said Pramila Jayapal, chair of the Congressional Progressive caucus. “The deal they passed tonight proves that point, and I could not be part of their extortion scheme.”

Progressives in the Senate, including Senator Bernie Sanders, have echoed that criticism and indicated they plan to oppose the debt ceiling proposal, but the bill still appears likely to become law. The Senate Democratic majority leader, Senator Chuck Schumer of New York, has pledged to act swiftly to take up the bill once it has passed the House. The Senate Republican minority leader, Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, has already indicated he plans to support the proposal as well.

“Any needless delay, any last-minute brinksmanship at this point would be an unacceptable risk,” Schumer said in a floor speech Wednesday morning. “Moving quickly, working together to avoid default is the responsible and necessary thing to do.”

READ MORE  Drag artists applying makeup before a performance in a club in Istanbul in May. (photo: Sergey Ponomarev)

Drag artists applying makeup before a performance in a club in Istanbul in May. (photo: Sergey Ponomarev)

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan vilified gay people during his re-election campaign, calling them a threat to society and rallying conservatives against them. It has left people feeling threatened, and alone.

They were familiar themes, heard often throughout Mr. Erdogan’s campaign for re-election: He frequently attacked L.G.B.T.Q. people, referring to them as “deviants” and saying they were “spreading like the plague.” But Ms. Oz said she had hoped it was just electioneering to rally the president’s conservative base.

“I was already worried about what was to come for us,” said Ms. Oz, 49. But after the speech, she thought, “it will get harsher.”

The rights and freedoms of L.G.B.T.Q. citizens became a lightning-rod issue during this year’s election campaign. Mr. Erdogan, facing the greatest political threat of his two decades as the country’s dominant leader and seeking to woo conservatives, repeatedly attacked his opponents for supposedly supporting gay rights. The anti-Erdogan opposition mostly avoided the topic for fear of alienating some of its own voters.

That left many L.G.B.T.Q. people fearing that the discrimination they have long faced by the government and conservative parts of society could worsen — and feeling that no one in the country had their backs.

“People are scared and having dystopian thoughts like, ‘Are we going to be slashed or violently attacked in the middle of the street?’” said Ogulcan Yediveren, a coordinator at SPoD, an L.G.B.T.Q. advocacy group in Istanbul. “What will happen is that people will hide their identities, and that is bad enough.”

Turkey, a predominantly Muslim society with a secular state, does not criminalize homosexuality and has laws against discrimination. But in recent conversations, more than a dozen L.G.B.T.Q. people said they often struggled to find jobs, secure housing and get quality health care as well as to be accepted by their friends, relatives, neighbors and co-workers.

In recent years, they said, they have encountered new restrictions on their visibility in society. Universities have shut down L.G.B.T.Q. student clubs. And since 2014, the authorities have banned Pride parades in major cities, including in Istanbul, where crowds in the tens of thousands used to participate.

That tracks with Mr. Erdogan’s vision for Turkey.

Since the start of his national political career in 2003, he has increased his own power while promoting a conservative Muslim view of society. He insists that marriage can only be between a man and a woman, and encourages women to have three children to build the nation.

Rights advocates say that as Mr. Erdogan has gained power, his conservative outlook has filtered down, encouraging local authorities to restrict L.G.B.T.Q. activities and pushing the security forces to crack down on gay rights activism.

Anti-L.G.B.T.Q. rhetoric was more prominent during this election than in past cycles, even though there are no looming legal changes that would expand or limit rights. No political party is trying to legalize same-sex marriage or adoption, for example, or expand medical care for transgender youth.

Instead, Mr. Erdogan and his allies use the issue to galvanize conservatives.

“What they want to impose on society in terms of other values is full of hatred and violence toward us,” said Nazlican Dogan, 26, who is facing legal charges related to participation in pro-L.G.B.T.Q. protests at Bogazici University in Istanbul. “It was really ugly and it made us feel that we can’t exist in this country, like I should just leave.”

During his campaign, Mr. Erdogan characterized L.G.B.T.Q. people as a threat to society.

“If the concept of family is not strong, the destruction of the nation happens quickly,” he told young people during a televised meeting in early May. “L.G.B.T. is a poison injected into the institution of the family. It is not possible for us to accept that poison as a country whose people are 99 percent Muslim.”

In April, his interior minister, Suleyman Soylu, went even further, falsely claiming that gay rights would allow humans to marry animals.

SPoD, the advocacy group, asked parliamentary candidates during the campaign to sign a contract to protect L.G.B.T.Q. rights. Fifty-eight candidates signed, and 11 of them won seats in the 600-member legislature, said Mr. Yediveren, the coordinator.

His group has also tried to expand legal protections for L.G.B.T.Q. people.

While certain laws prohibit discrimination, they do not specifically mention sexual identity or orientation, he said. At the same time, the authorities often cite vague concepts like “general morals” and “public order” to act against activities they don’t like, such as Pride week events.

“This week is very important because we don’t have physical locations we can come together as a community to support each other,” said Bambi Ceren, 34, a member of a committee planning events for this year’s Pride week, which begins on June 19.

Last year, the police prevented Pride events and arrested people who gathered to take part, committee members said.

SPoD runs a national hotline to field queries about sexual orientation, legal protections or how to access medical care or other services. The group can solve most issues related to services, Mr. Yediveren said, but most callers’ problems are social and emotional.

“People are feeling very lonely and isolated,” he said.

Transgender individuals struggle to find jobs, housing and proper medication and care. And gay men and lesbians are sometimes forced into heterosexual marriages and fear coming out to their families and co-workers.

Worrying about, “‘Will I be caught one day?’ causes a lot of stress for them,” Mr. Yediveren said.

And the threat of violence is real.

Some L.G.B.T.Q. people said they had been beaten by the security forces during protests or met with indifference from the police while being harassed on the street.

A survey last year by ILGA-Europe, a rights organization, ranked Turkey second-to-last out of 49 European countries on L.G.B.T.Q. rights. Another group, Transgender Europe, said that 62 transgender people had been killed in Turkey between 2008 and 2022.

Many L.G.B.T.Q. people fear that the demonization during the campaign will make that threat more acute.

A queer university student from Turkey’s Kurdish minority, who grew up in a smaller city with no significant L.G.B.T.Q. presence, said she feared that bad days were ahead.

People who would not normally commit violence might feel empowered to do so because the government had spread hatred for people like her, she said, claiming they were sick, dangerous or a threat to the family. She spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of being attacked.

Despite the increased danger, many L.G.B.T.Q. people vowed to keep fighting for their rights and maintaining their visibility in society. To deal with the fear of random attacks, they plan to look out for each other more to ensure they are safe.

In Istanbul, a 25-year-old drag performer who goes by the stage name Florence Konstantina Delight and uses gender-neutral pronouns called the new attention unsettling.

“In the whole history of queer life in Turkey, we could never be that visible,” they said in an interview. “But because of the election, everyone was talking about us.”

They described growing up in Turkey as “full of abuse, full of denial, full of teachers ignoring your existence and what happened to you, like your pals bullying you.”

At age 16, Florence accepted their sexual identity, attended a Pride parade and set up a Facebook account with a fake name to contact L.G.B.T.Q. organizations and make friends, eventually stumbling upon someone at the same high school.

They later moved to Istanbul, where they perform weekly at a rare L.G.B.T.Q.-friendly bar.

Mr. Erdogan’s win on Sunday caused Florence despair.

“I stared into space for a while,” they said.

READ MORE  Amazon workers participate in a walkout at Amazon Headquarters, in Seattle, Washington, U.S., May 31, 2023. (photo: Matt Mills McKnight/Reuters)

Amazon workers participate in a walkout at Amazon Headquarters, in Seattle, Washington, U.S., May 31, 2023. (photo: Matt Mills McKnight/Reuters)

Some Amazon Employees Walk Out in Seattle to Protest Climate, Office Policies

Matt Mcknight, Reuters

Mcknight writes: "Some Amazon.com Inc employees staged a walkout on Wednesday in protest of the e-commerce giant's changes to its climate policy, layoffs and a return-to-office mandate."

More than 100 people gathered in the afternoon by the Spheres, the glass-dome monument at the heart of Amazon's Seattle headquarters, according to a Reuters witness. "Emissions climbing. Time to act!" the group chanted. "Stand together; don't turn back!"

More than 1,900 employees had pledged to protest globally, according to the organizers, an activist group known as Amazon Employees for Climate Justice (AECJ).

Amazon said it had not observed actions other than in Seattle.

The walkout follows moves that took Amazon "in the wrong direction," AECJ has said. Among them, the company recently eliminated a goal to make all Amazon shipments net zero for carbon emissions by 2030, though it still has a broader pledge on climate for a decade later.

Amazon also announced some 27,000 role cuts in recent months, or 9% of its corporate workforce, a shift for a company that long touted its job creation. A return-to-office mandate by May 1 caused confusion for some staff as to whether they needed to relocate homes nearer to work or whether they would be laid off beforehand.

In a statement, Amazon spokesperson Brad Glasser said the company is pushing hard to cut its carbon emissions.

"For companies like ours who consume a lot of power, and have very substantial transportation, packaging, and physical building assets, it’ll take time to accomplish," he said. "We remain on track to get to 100% renewable energy by 2025."

He added that Amazon listens to employee feedback and was happy with the collaboration that arose from its return-to-office policy.

There have been other protests in recent years, including in 2019, when Amazon workers were among hundreds of employees of large technology companies to join marches in San Francisco and Seattle, saying their employers were too slow to tackle global warming.

READ MORE

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611