Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

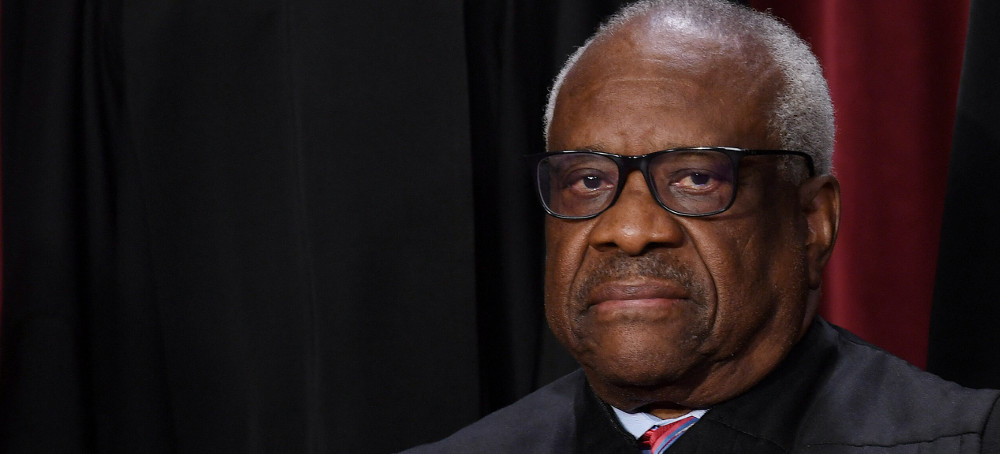

Crow paid for private school for a relative Thomas said he was raising “as a son.” “This is way outside the norm,” said a former White House ethics lawyer.

Tuition at the boarding school ran more than $6,000 a month. But Thomas did not cover the bill. A bank statement for the school from July 2009, buried in unrelated court filings, shows the source of Martin’s tuition payment for that month: the company of billionaire real estate magnate Harlan Crow.

The payments extended beyond that month, according to Christopher Grimwood, a former administrator at the school. Crow paid Martin’s tuition the entire time he was a student there, which was about a year, Grimwood told ProPublica.

“Harlan picked up the tab,” said Grimwood, who got to know Crow and the Thomases and had access to school financial information through his work as an administrator.

Before and after his time at Hidden Lake, Martin attended a second boarding school, Randolph-Macon Academy in Virginia. “Harlan said he was paying for the tuition at Randolph-Macon Academy as well,” Grimwood said, recalling a conversation he had with Crow during a visit to the billionaire’s Adirondacks estate.

ProPublica interviewed Martin, his former classmates and former staff at both schools. The exact total Crow paid for Martin’s education over the years remains unclear. If he paid for all four years at the two schools, the price tag could have exceeded $150,000, according to public records of tuition rates at the schools.

Thomas did not report the tuition payments from Crow on his annual financial disclosures. Several years earlier, Thomas disclosed a gift of $5,000 for Martin’s education from another friend. It is not clear why he reported that payment but not Crow’s.

The tuition payments add to the picture of how the Republican megadonor has helped fund the lives of Thomas and his family.

“You can’t be having secret financial arrangements,” said Mark W. Bennett, a retired federal judge appointed by President Bill Clinton. Bennett said he was friendly with Thomas and declined to comment for the record about the specifics of Thomas’ actions. But he said that when he was on the bench, he wouldn’t let his lawyer friends buy him lunch.

Thomas did not respond to questions. In response to previous ProPublica reporting on gifts of luxury travel, he said that the Crows “are among our dearest friends” and that he understood he didn’t have to disclose the trips.

ProPublica sent Crow a detailed list of questions and his office responded with a statement that did not dispute the facts presented in this story.

“Harlan Crow has long been passionate about the importance of quality education and giving back to those less fortunate, especially at-risk youth,” the statement said. “It’s disappointing that those with partisan political interests would try to turn helping at-risk youth with tuition assistance into something nefarious or political.” The statement added that Crow and his wife have “supported many young Americans” at a “variety of schools, including his alma mater.” Crow went to Randolph-Macon Academy.

Crow did not address a question about how much he paid in total for Martin’s tuition. Asked if Thomas had requested the support for either school, Crow’s office responded, “No.”

Last month, ProPublica reported that Thomas accepted luxury travel from Crow virtually every year for decades, including international superyacht cruises and private jet flights around the world. Crow also paid money to Thomas and his relatives in an undisclosed real estate deal, ProPublica found. After he purchased the house where Thomas’ mother lives, Crow poured tens of thousands of dollars into improving the property. And roughly 15 years ago, Crow donated much of the budget of a political group founded by Thomas’ wife, which paid her a $120,000 salary.

“This is way outside the norm. This is way in excess of anything I’ve seen,” said Richard Painter, former chief White House ethics lawyer for President George W. Bush, referring to the cascade of gifts over the years.

Painter said that when he was at the White House, an official who’d taken what Thomas had would have been fired: “This amount of undisclosed gifts? You’d want to get them out of the government.”

A federal law passed after Watergate requires justices and other officials to publicly report most gifts. Ethics law experts told ProPublica they believed Thomas was required by law to disclose the tuition payments because they appear to be a gift to him.

Justices also must report many gifts to their spouses and dependent children. The law’s definition of dependent child is narrow, however, and likely would not apply to Martin since Thomas was his legal guardian, not his parent. The best case for not disclosing Crow’s tuition payments would be to argue the gifts were to Martin, not Thomas, experts said.

But that argument was far-fetched, experts said, because minor children rarely pay their own tuition. Typically, the legal guardian is responsible for the child’s education.

“The most reasonable interpretation of the statute is that this was a gift to Thomas and thus had to be reported. It’s common sense,” said Kathleen Clark, an ethics law expert at Washington University in St. Louis. “It’s all to the financial benefit of Clarence Thomas.”

Martin, now in his 30s, told ProPublica he was not aware that Crow paid his tuition. But he defended Thomas and Crow, saying he believed there was no ulterior motive behind the real estate magnate’s largesse over the decades. “I think his intentions behind everything is just a friend and just a good person,” Martin said.

[After this story was published, Mark Paoletta, a longtime friend of Clarence Thomas who has also served as Ginni Thomas’ lawyer, released a statement. Paoletta confirmed that Crow paid for Martin’s tuition at both Randolph-Macon Academy and Hidden Lake, saying Crow paid for one year at each. He did not give a total amount but, based on the tuition rates at the time, the two years would amount to roughly $100,000.

Paoletta said that Thomas did not have to report the payments because Martin was not his “dependent child” as defined in the disclosure law. He criticized ProPublica for reporting on this and said “the Thomases and the Crows are kind, generous, and loving people who tried to help this young man.”]

Crow has long been an influential figure in pro-business conservative politics. He has given millions to efforts to move the law and the judiciary to the right and serves on the boards of think tanks that publish scholarship advancing conservative legal theories.

Crow has denied trying to influence the justice but has said he extended hospitality to him just as he has to other dear friends. From the start, their relationship has intertwined expensive gifts and conservative politics. In a recent interview with The Dallas Morning News, Crow recounted how he first met Thomas. In 1996, the justice was scheduled to give a speech in Dallas for an anti-regulation think tank. Crow offered to fly him there on his private jet. “During that flight, we found out we were kind of simpatico,” the billionaire said.

The following year, the Thomases began to discuss taking custody of Martin. His father, Thomas’ nephew, had been imprisoned in connection with a drug case. Thomas has written that Martin’s situation held deep resonance for him because his own father was absent and his grandparents had taken him in “under very similar circumstances.”

Thomas had an adult son from a previous marriage, but he and wife, Ginni, didn’t have children of their own. They pitched Martin’s parents on taking the boy in.

“Thomas explained that the boy would have the best of everything — his own room, a private school education, lots of extracurricular activities,” journalists Kevin Merida and Michael Fletcher reported in their biography of Thomas.

Thomas gained legal custody of Martin and became his legal guardian around January 1998, according to court records.

Martin, who had been living in Georgia with his mother and siblings, moved to Virginia, where he lived with the justice from the ages of 6 to 19, he said.

Living with the Thomases came with an unusual perk: lavish travel with Crow and his family. Martin told ProPublica that he and Thomas vacationed with the Crows “at least once a year” throughout his childhood.

That included visits to Camp Topridge, Crow’s private resort in the Adirondacks, and two cruises on Crow’s superyacht, Martin said. On a trip in the Caribbean, Martin recalled riding jet skis off the side of the billionaire’s yacht.

Roughly 20 years ago, Martin, Thomas and the Crows went on a cruise on the yacht in Russia and the Baltics, according to Martin and two other people familiar with the trip. The group toured St. Petersburg in a rented helicopter and visited the Yusupov Palace, the site of Rasputin’s murder, said one of the people. They were joined by Chris DeMuth, then the president of the conservative think tank the American Enterprise Institute. (Thomas’ trips with Crow to the Baltics and the Caribbean have not previously been reported.)

Thomas reconfigured his life to balance the demands of raising a child with serving on the high court. He began going to the Supreme Court before 6 a.m. so he could leave in time to pick Martin up after class and help him with his homework. By 2001, the justice had moved Martin to private school out of frustration with the Fairfax County public school system’s lax schedule, The American Lawyer magazine reported.

For high school, Thomas sent Martin to Randolph-Macon Academy, a military boarding school 75 miles west of Washington, D.C., where he was in the class of 2010. The school, which sits on a 135-acre campus in the Shenandoah Valley, charged between $25,000 to $30,000 a year. Martin played football and basketball, and the justice sometimes visited for games.

Randolph-Macon was also Crow’s alma mater. Thomas and Crow visited the campus in April 2007 for the dedication of an imposing bronze sculpture of the Air Force Honor Guard, according to the school magazine. Crow donated the piece to Randolph-Macon, where it is a short walk from Crow Hall, a classroom building named after the Dallas billionaire’s family.

Martin sometimes chafed at the strictures of military school, according to people at Randolph-Macon at the time, and he spent his junior year at Hidden Lake Academy, a therapeutic boarding school in Georgia. Hidden Lake boasted one teacher for every 10 students and activities ranging from horseback riding to canoeing. Those services came at an added cost. At the time, a year of tuition was roughly $73,000, plus fees.

The July 2009 bank statement from Hidden Lake was filed in a bankruptcy case for the school, which later went under. The document shows that Crow Holdings LLC wired $6,200 to the school that month, the exact cost of the month’s tuition. The wire is marked “Mark Martin” in the ledger.

Crow’s office said in its statement that Crow’s funding of students’ tuition has “always been paid solely from personal funds, sometimes held at and paid through the family business.”

Grimwood, the administrator at Hidden Lake, told ProPublica that Crow wired the school money once a month to pay Martin’s tuition fees. Grimwood had multiple roles on the campus, including overseeing an affiliated wilderness program. He said he was speaking about the payments because he felt the public should know about outside financial support for Supreme Court justices. Martin returned to Randolph-Macon his senior year.

Thomas has long been one of the less wealthy members of the Supreme Court. Still, when Martin was in high school, he and Ginni Thomas had income that put them comfortably in the top echelon of Americans.

In 2006 for example, the Thomases brought in more than $500,000 in income. The following year, they made more than $850,000 from Clarence Thomas’ salary from the court, Ginni Thomas’ pay from the Heritage Foundation and book payments for the justice’s memoir.

It appears that at some point in Martin’s childhood, Thomas was paying for private school himself. Martin told ProPublica that Thomas sold his Corvette — “his most prized car” — to pay for a year of tuition, although he didn’t remember when that occurred.

In 2002, a friend of Thomas’ from the RV community who owned a Florida pest control company, Earl Dixon, offered Thomas $5,000 to help defray the costs of Martin’s education. Thomas’ disclosure of that earlier gift, several experts said, could be viewed as evidence that the justice himself understood he was required to report tuition aid from friends.

“At first, Thomas was worried about the propriety of the donation,” Thomas biographers Merida and Fletcher recounted. “He agreed to accept it if the contribution was deposited directly into a special trust for Mark.” In his annual filing, Thomas reported the money as an “education gift to Mark Martin.”

Prosecutors alleged defendants viewed themselves as Donald Trump’s army, intent on keeping him in power through violence

A jury deliberated for seven days in Washington before finding Tarrio, 39, and other defendants guilty on 31 of 46 counts. The jury returned not guilty verdicts on four counts and continued deliberating on 11 remaining counts. The result was another decisive victory for the Justice Department in the last of three seditious conspiracy trials held after what it called a historic act of domestic terrorism to prevent the peaceful transfer of power from Donald Trump to Joe Biden after the 2020 presidential election.

Tarrio, dressed in blue suit and vest with red tie, gazed at his relatives in the courtroom gallery as the verdict was read. The other men fixed their eyes on the jury foreman.

“If the worst happens … we’re standing on principle,” Tarrio said in a jail call shared on social media after closing arguments on April 25, making his first extended public comments since his March 2022 indictment.

Tarrio did not testify at trial, but he contradicted his defense team’s argument to jurors that he was being made “a scapegoat for Donald Trump and those in power.” Instead, Tarrio embraced hard-line Trump backers’ claims that he was being used as “the next steppingstone” to “get to” Trump, who is running again for president. “They’re trying to get to the top and they’re trying to manipulate the 2024 election,” he said in the jail call.

Legal analysts said the convictions on the historically rare and politically weighty crime of seditious conspiracy sent a necessary signal of deterrence to extremists contemplating political violence. The verdict also could pose repercussions for the former president as Special Counsel Jack Smith investigates whether Trump or those around him broke the law in seeking to hold onto power by fanning false and incendiary claims that the election was stolen, pressuring state and federal officials to assist the effort, and sending thousands of supporters who heard him speak at a Jan. 6 rally to march to the Capitol.

“The verdict empowers the special counsel to bring indictments for the efforts to overturn the election,” said New York University law professor Ryan Goodman. “It underscores the enormous stakes in mobilizing Americans to believe the Big Lie and directing an armed crowd to interfere with the congressional proceedings.”

The convictions mark “an important milestone on the journey to accountability for the perpetrators of the insurrection on January 6, 2021 … showing that political violence and attacks on our democratic institutions will be taken seriously by our justice system and will not be tolerated by the American people,” said Lindsay Schubiner, director of programs at Western States Center, a Portland-based civil rights group that monitors anti-democracy movements nationwide.

Over nearly 15 weeks of proceedings, prosecutors alleged that the Proud Boys on trial saw themselves as Trump’s “army.” Inspired by his directive to “stand by” during a September 2020 presidential debate and mobilized by his December 2020 call for a “wild” protest, prosecutors said, the men sought to keep Trump in power through violence on the day that Congress met to certify the presidential election results.

Defense attorneys for Tarrio fought back by blaming the former president, saying prosecutors were punishing the Proud Boys for their political beliefs, for an unplanned riot triggered by Trump’s incitement of angry supporters, and for law enforcement failures.

All defendants were convicted of at least one count punishable by up to 20 years in prison. Tarrio and fellow Proud Boys leaders Ethan Nordean, Joe Biggs and Zachary Rehl were found guilty of three such crimes: seditious conspiracy — or plotting to oppose by force Congress’s confirmation of the election result — conspiring to obstruct the congressional session, and actually obstructing the proceeding.

The jury did not come to an agreement on whether rank-and-file member Dominic Pezzola, who joined the Proud Boys in late 2020, was part of either conspiracy, but it did find him guilty of the obstruction charge, as well as of assaulting police, stealing a riot shield and smashing the first window breached by rioters. All five were convicted of conspiring to block lawmakers and police from doing their jobs.

U.S. District Judge Timothy J. Kelly directed the jury to resume deliberations over Pezzola as well as whether to hold all five men responsible for aiding Pezzola’s destruction of government property and another Proud Boys member who threw a water bottle at an officer.

Tarrio is the first person not present at the Capitol to be found criminally responsible at trial in the violence that injured scores of police, ransacked offices and forced the evacuation of lawmakers. The government alleged he watched from Baltimore after being expelled from D.C. one day earlier pending trial for burning a stolen “Black Lives Matter” flag at an earlier pro-Trump rally in Washington.

Fourteen people have now been convicted of seditious conspiracy for Jan. 6 violence, all followers of two high-profile groups in the alt-right or anti-government extremist movements, the Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers, whose founder Stewart Rhodes and five followers were found guilty in November and January. Four other members of the two groups previously pleaded guilty to the count. Three Oath Keepers members were acquitted but, like Pezzola, were convicted of obstructing the congressional session.

The verdict concludes the last of three Jan. 6 seditious conspiracy trials, the highest-profile cases stemming from the largest prosecution in U.S. history.

Both Tarrio and Rhodes were accused of playing an outsize role in organizing the violence or threat of violence by extremists drawn to the Capitol by Trump’s incendiary and baseless claims that the 2020 election was illegitimate.

Defense lawyers say the government’s theory that Tarrio and his co-defendants could be held criminally liable for using other rioters as “tools” of violence could be applied to many others who weren’t near the Capitol that day.

But U.S. prosecutors have not produced any “smoking gun” evidence explicitly tracing the actions of any of the Capitol’s violent actors to Trump or his advisers — either from a cooperating witness or an actual written message — although that conceivably could change if anyone still facing charges or pending sentencing “flips” and cooperates.

The government’s own evidence at trial showed how challenging the investigation has been. Statements by a lead FBI case agent in internal messages accidentally disclosed to the defense and entered into trial show that investigators only cracked Tarrio’s encrypted phone in late January 2022 — a year after the riot.

Only then, FBI Special Agent Nicole Miller wrote on Feb. 1, 2022, did she believe evidence on Tarrio’s phone cleared the “hurdle” to bring a conspiracy case against him.

The government argued that the Proud Boys’ concerted action on Jan. 6 alone was evidence of a criminal conspiracy, when prosecutors said the group marched to the Capitol even before Trump finished speaking at the White House Ellipse, helped drive rioters forward at several points, and celebrated with “victory smokes” and claims of credit after the Capitol breach.

“Make no mistake …” Tarrio texted, “We did this.”

But prosecutors also cited hundreds of encrypted messages, chats and social media posts involving the defendants. The conversations discussed keeping Trump in power “by any means necessary including force” — as star government witness and Proud Boys cooperator Jeremy Bertino testified — and storming the Capitol. The messages show that the Proud Boys were also angry at police handling of Bertino’s stabbing after a Dec. 12, 2020, rally in Washington, the government said.

The government has previously shown evidence that Tarrio, a former aide to Trump political confidant Roger Stone, was in contact with Trump’s “stop the steal” campaign organizer Ali Alexander and Oath Keepers founder Rhodes throughout the post-election period. Rhodes had shared a proposal for storming Congress — while Tarrio, Nordean and Biggs were each in phone and text contact with Infowars.com founder Alex Jones or producer Owen Shroyer on Jan. 4, 5 and 6.

Stone, Alexander and Jones have denied any wrongdoing and have not been charged with any crime.

The Proud Boys used “1776” as a shorthand for what they wanted to achieve, prosecutor Conor Mulroe said in closing arguments. But he said the defendants’ violent revolution would have reversed the Revolutionary War’s achievement — founding “a nation where leaders were chosen by the people, and power was handed over peacefully under the rule of law — not ruled by a king for life through the power of his army.”

Attorneys for the Proud Boys put on a combative defense, variously urging jurors to blame the violence on Trump, not his followers; accusing the Biden administration of overcharging protesters and locking up political opponents; alleging that a corrupt or incompetent Justice Department hid informants’ and police roles in the violence; and casting the defendants as beer-drinking brawlers who were patriots at heart, not “foot soldiers of the right” who turned from violently battling leftists in the streets to attacking police and lawmakers.

“There were no statements in those chats about stopping the transfer of power on Jan. 6 with or without force,” Tarrio attorney Nayib Hassan said, and defendants had no “shared objective” other than to march, protest and promote the Proud Boys brand.

The government’s entire case was built on a kind of “misdirection and innuendo,” manipulating jurors’ hostility toward Trump and playing to their “anger, emotion and partisan prejudice” to convict the men based on “guilt by association,” Nordean defense attorney Nicholas Smith said.

Tarrio, Nordean and Biggs did not testify at trial, but Rehl said the Proud Boys’ preparations were strictly for self-defense after past violence in Washington. “There was nothing nefarious about it,” he said.

Pezzola took the stand to “take responsibility for my actions” and to clear the others of culpability. But he also attacked prosecutors and said he would stand “against this corrupt trial with your fake charges.”

While prosecutors offered no specific plan centered on the certification, they showed jurors scores of messages in which defendants said they would go to war to keep Trump in office.

The defense struggled with the deluge of videos, Parler posts and Telegram messages amassed by the government, showing Proud Boys cheering and encouraging violence. When Rehl testified that he assaulted no one, the government surprised him with video that appeared to show him firing pepper-spray at police.

But attorneys cast themselves as defenders of the constitutional right to protest, not just of a group they acknowledged could be offensive, crude and even hateful. One — Biggs attorney Norm Pattis — warned darkly that convictions would only exacerbate the country’s divisions and possibly lead to civil war.

For now, the Proud Boys organization is a shell of what it once was. The Jan. 6 prosecution, along with revelations that Tarrio and others have been federal informants, have divided the group. But membership continues to grow, and followers have found a new cause in protesting drag performances and transgender rights events around the country, sometimes leading to violence.

“If you are running a group [that] is somewhat effective … I guarantee you that there are [informants] within your group,” Tarrio said after closing arguments Tuesday in a jail call with reporters hosted by Gateway Pundit. He added that upon his release, he thought he might get out of politics and do “some kind of cultural thing.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611