|

|

UNDER CONSTRUCTION - MOVED TO MIDDLEBORO REVIEW AND SO ON https://middlebororeviewandsoon.blogspot.com/

|

|

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

uthorities claimed an activist shot a trooper before he was gunned down, but new video captures a cop telling a colleague, “You fucked your own officer up.”

Authorities said an officer gunned down Manuel “Tortuguita” Teran on Jan. 18 because Teran opened fire first, hitting a state trooper as officers conducted a sweep of the forest where Teran and dozens of others had protested—and lived—for months.

Authorities claimed in January that there was no video of the shooting available. On Wednesday, however, Atlanta police released footage of officers near the shooting, which captured audio of at least a dozen gunshots, despite not capturing the gunfire visually.

Moments after police opened fire on Tortugita, killing them, and Atlanta Police officer can be heard saying, "Man...you fucked your own officer up?" in reference to the trooper that was also shot. pic.twitter.com/qw8G0G34b0

— Atlanta Community Press Collective (@atlanta_press) February 9, 2023

Also in the clip was an unnamed officer’s reaction to the gunfire, which implied law enforcement may have been shooting at each other.

“Man,” the officer said. “You fucked your own officer up.”

Activists, who’ve proclaimed Teran’s innocence, honed in on that soundbyte Wednesday, claiming it discredited the Georgia Bureau of Investigation's story that Teran opened fire and struck a state trooper first before cops fired back at him.

“I feel nothing but rage right now,” Micah Herskind, a local organizer against Cop City, wrote on Twitter. “Rage that they assassinated Tortugita [sic] and lied about it. Rage at a violent system that continues to claim lives and make the victims look like the villains.”

Herskind called the footage “completely damning.”

State investigators told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution that they’re sticking with their initial story of what happened despite the newly-released footage.

“Our original assessment that we provided is based on the facts that have been uncovered in the investigation,” spokesperson Nelly Miles said. “It’s not based on a story that has been fabricated online and repeated in the media.”

The shooting came on the heels of months of protest near the construction site for the proposed police training facility, which supposedly cost $90 million and will include state-of-the-art explosive testing areas, firing ranges, and a mock city.

In addition to arguing it’s a waste of taxpayer money, environmental activists, like Teran, had campaigned to save the forest that’s likely to be destroyed to construct the facility.

Clashes with police had become violent in the past, but never fatal prior to January. Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp called the protesters “domestic terrorists” last year.

While state troopers don’t wear body-cams, Teran’s family had called on Atlanta police to release footage from their officers who were close to the scene and equipped with body-cams. In a press conference, they also said an independent autopsy revealed Teran suffered at least 13 gunshot wounds.

The footage released Wednesday—totalling more than 40 minutes across four videos—begins with Atlanta officers walking through the woods, destroying tents and confiscating items left behind by protesters. A seemingly light mood among the officers turns serious when gunfire breaks out just after 9 a.m.

The camera captures the officers taking cover behind trees, with one asking, “Is this target practice?”

People are heard screaming but their words are indiscernible. The cops appear to move closer to the gunfire, with one officer heard saying the shots “sounded like suppressed gunfire,” which another officer agreed with.

Moments later, the camera-wearing officer is heard saying, “man, you fucked your own officer up.”

A theory that the incident was an instance of “friendly fire” has been repeated by activists since the day of the shooting. On Jan. 18, an account named “Defend The Atlanta Forest,” tweeted about the theory just hours after Teran was pronounced dead.

“We have reason to believe the officer shot today was hit by ‘friendly fire’ and not by the protester who was killed,” the account wrote. “Do not believe the police and their media. Demand an end to police militarization and hands off the forest.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

In the portion of his speech on the need to raise the debt limit, Biden said that “some of my Republican friends want to take the economy hostage unless I agree to their economic plans.” Speaker Kevin McCarthy, who had given his own remarks on the debt limit the day before to pre-but the attacks he knew would come, gave one of his many solemnly disappointed shakes of the head.

“Some Republicans want Social Security and Medicare to sunset,” Biden said, before being cut off by loud Republican jeering, punched up with individual shouts from the likes of Georgia Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, who pointed at the president yelling “liar!”

The scene was chaotic enough that Biden had to veer off-script and engage in a live policy dialogue with his detractors. That’s unusual, and thrilling for what’s otherwise become a stale tradition. He clarified, almost apologetically, that he wasn’t talking about all Republicans. And when some shouted at him to name these Republicans who wanted Social Security and Medicare to expire, Biden demurred.

“I’m politely not naming them,” he said, “but it’s being proposed by some.”

The prepared line in Biden’s speech, before he was interrupted, was that “some Republicans want Medicare and Social Security to sunset every five years.” The “some Republicans,” in this case, is one Rick Scott.

In his 11-point plan, sub-point 7 of point 6 reads: “All federal legislation sunsets in 5 years. If a law is worth keeping, Congress can pass it again.” The plan doesn’t single out Medicare and Social Security specifically, but these are programs that were established by federal legislation and would thus disappear under Scott’s proposal unless renewed every five years. This is an… impracticable idea. Congress can’t, and no one should want them to, rewrite all federal law every five years.

But the agenda’s out, and now Scott and his party have to live with it. Scott is, of course, capable of softening that language, or deleting it altogether, any time he wants to. He’s already watered down another bullet-point suggesting that all “Americans should pay some income tax to have skin in the game” after everyone pointed out that he was calling to raise taxes on the poorest half of Americans.

Given that he’s had a year to learn this lesson, you would think Scott might be changing his tune now. In releasing the plan last year, Scott had released a Republican agenda for Democrats to scour for attacks throughout the midterm elections (even though he insisted he was acting in his personal capacity). It was a direct challenge to Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell’s preferred election strategy of keeping the focus strictly on Democratic policies.

As we know, Republicans’ efforts to retake the Senate never materialized, with Democrats adding one seat to their threadbare majority. And even though the election has passed, Democrats have hardly forgotten about the political potency embedded in elements of Scott’s plan, which again he could still modify if he so chose.

But Scott still hasn’t done that with this agenda item. Even after a night to sleep on it, Scott woke up Wednesday defending his idea.

🧵 Last night, @JoeBiden rambled for a while, but it seems he forgot to share the facts:

— Rick Scott (@SenRickScott) February 8, 2023

In my plan, I suggested the following: All federal legislation sunsets in 5 yrs. If a law is worth keeping, Congress can pass it again.

This is clearly & obviously an idea aimed at dealing with ALL the crazy new laws our Congress has been passing of late.

— Rick Scott (@SenRickScott) February 8, 2023

@JoeBiden is confused…to suggest that this means I want to cut Social Security or Medicare is a lie, & is a dishonest move…from a very confused President.

Does he think I also intend to get rid of the U.S. Navy? Or the border patrol? Or air traffic control, maybe?

— Rick Scott (@SenRickScott) February 8, 2023

This is the kind of fake, gotcha BS that people hate about Washington.

I’ve never advocated cutting Social Security or Medicare and never would.

Is it clear and obvious, though, that this idea is “aimed at dealing with ALL the crazy new laws our Congress has been passing of late”? When we read “all federal legislation,” we think about more than the Inflation Reduction Act or the American Rescue Plan. Where to begin? We think of the Voting Rights Act or the Clean Water Act. We think of the establishment of the Department of Education. And we think of Medicare, Social Security, and Medicaid. These may not all be laws that Republicans want to scrap in their entirety. But they are ones that many Republicans would like to have a fresh leverage point over, every five years, to make cuts. For now, they believe their only real leverage point to tackle spending programs they believe are on “autopilot” is when it’s time to raise the debt ceiling, which is why we are where we are, with another looming debt ceiling crisis that threatens a brittle global economy.

Plenty of Republicans, including chairmen of important committees and caucuses in the House, have been muttering about using the debt limit to force changes to Medicare and Social Security. Even before the State of the Union, though, that was unlikely to be the path they pursued in negotiations. McCarthy for one—and Donald Trump, for another—understands that holding the global economy hostage in order to extract cuts to Medicare and Social Security would be the dumbest move in history. They would lose the policy fight, and the political damage could cost them the 2024 election. In his remarks the day before the State of the Union, McCarthy said that “cuts to Medicare and Social Security are off the table” for the debt limit negotiations.

Biden used his State of the Union to lock them into that position. As Republican protested his claim that “some” of them wanted to cut Medicare and Social Security, he said he was happy to see so much “conversion.”

“So folks, as we all apparently agree, Social Security and Medicare is off the books now, right?” Biden said. Applause broke out.

The one saving grace for Rick Scott? If it wasn’t his toxic plan Biden chose to highlight, it would have been someone else’s. There’s plenty of loose talk out there. It could have been Wisconsin Sen. Ron Johnson’s suggestion that mandatory spending programs be subjected to annual review. It could have been Utah Sen. Mike Lee’s 2010 vow to “to phase out Social Security, to pull it up from the roots and get rid of it.” Biden could have simply referenced Republicans’ efforts to cut Medicaid, a cornerstone of their 2017 Obamacare repeal plan, which quite nearly made it into law.

When put like that, though, Scott deserves some credit. One line from a brochure has had enough juice not just to survive a year in his opponents’ playbook, but to be the focal point of an unusually memorable State of the Union as an incumbent president prepares for reelection. It’s an achievement, showcasing the long, toxic shelf life of a poorly written idea.

READ MORE  Ukrainian officials say that they almost never launch HIMARS rounds without detailed coordinates provided by U.S. military personnel situated elsewhere in Europe. (photo: Mosa'ab Eishamy/AP)

Ukrainian officials say that they almost never launch HIMARS rounds without detailed coordinates provided by U.S. military personnel situated elsewhere in Europe. (photo: Mosa'ab Eishamy/AP)

Ukrainian officials say that they almost never launch HIMARS rounds without detailed coordinates provided by U.S. military personnel situated elsewhere in Europe

The disclosure, confirmed by three senior Ukrainian officials and a senior U.S. official, comes after months of Kyiv’s forces pounding Russian targets — including headquarters, ammunition depots and barracks — on Ukrainian soil with the U.S.-provided High Mobility Artillery Rocket System, or HIMARS, and other similar precision-guided weapons such as the M270 multiple-launch rocket system.

One senior Ukrainian official said Ukrainian forces almost never launch the advanced weapons without specific coordinates provided by U.S. military personnel from a base elsewhere in Europe. Ukrainian officials say this process should give Washington confidence about providing Kyiv with longer-range weapons.

A senior U.S. official — who, like others, spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the issue — acknowledged the key American role in the campaign and said the targeting assistance served to ensure accuracy and conserve limited stores of ammunition for maximum effectiveness. The official said Ukraine does not seek approval from the United States on what to strike and routinely targets Russian forces on their own with other weapons. The United States provides coordinates and precise targeting information solely in an advisory role, the official said.

The GPS-guided strikes have driven back Moscow’s forces on the battlefield and been celebrated as a key factor in Kyiv’s underdog attempt to stave off the nearly year-old Russian assault. When Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky visited the White House in December, he gave President Biden a military medal that had been approved for meritorious service by the commander of a Ukrainian HIMARS unit.

The issue is sensitive for the U.S. government, which has cast itself as a nonbelligerent friend to the government in Kyiv as it fights for its sovereignty and survival. The Kremlin has repeatedly accused the United States and its NATO allies of fighting a proxy war in Ukraine.

Senior Pentagon officials declined for days to answer questions about whether and how they provide coordinates for the strikes, citing concerns about operational security. They instead provided a statement highlighting the limitations of American involvement.

“We have long acknowledged that we share intelligence with Ukraine to assist them in defending their country against Russian aggression, and we have optimized over time how we share information to be able to support their requests and their targeting processes at improved speed and scale,” Brig. Gen. Patrick Ryder, a Pentagon spokesman, said in the statement. “The Ukrainians are responsible for finding targets, prioritizing them and then ultimately deciding which ones to engage. The U.S. does not approve targets, nor are we involved in the selection or engagement of targets.”

The senior Ukrainian official described the targeting process, generally: Ukrainian military personnel identify targets they want to hit, and in which location, and that information is then sent up to senior commanders, who then relay the request to U.S. partners for more accurate coordinates. The Americans do not always provide the requested coordinates, the official said, in which case the Ukrainian troops do not fire.

Ukraine could carry out strikes without U.S. help, but because Kyiv doesn’t want to waste valuable ammunition and miss, it usually chooses not to strike without U.S. confirmation, the official said, adding that there are no complaints about the process.

For months now, the Ukrainian government has been lobbying Washington for longer-range precision weapons.

Kyiv possesses HIMARS launchers and a similar weapon, the M270 multiple-launch rocket system, each of which fire a U.S.-made rocket that can travel up to 50 miles.

Ukrainian officials also have sought the Army Tactical Missile System, or ATACMS, a munition that can be fired from the same launcher and travel up to 185 miles. Biden administration officials have declined to provide that weapon, which is in limited supply and seen by senior U.S. officials as an escalation that could provoke Russia and drag the United States directly into the war.

Kyiv has pledged that it would not use the longer-range missile to strike across the border inside Russia.

The senior Ukrainian official contended that the Ukrainian military would face the same limitations it does now with conventional HIMARS rounds if it received ATACMS, with Ukraine still dependent on U.S. targeting coordinates.

“You’re controlling every shot anyway, so when you say, ‘We’re afraid that you’re going to use it for some other purposes,’ well, we can’t do it even if we want to,” the senior Ukrainian official said.

The senior U.S. official disputed the characterization. It is “not true,” the U.S. official said, that “Ukrainians run targets by us for approval.”

Ukrainian military officials have said that Russian forces have moved back their ammunition stocks out of HIMARS range, which has led to a steep decline in the daily bombardment of Ukrainian cities and soldiers but also reduced Kyiv’s ability to target Moscow’s arsenal. With ATACMS, the Ukrainians probably would target Russian military installations in Crimea, which Russia invaded and annexed illegally in 2014.

The United States also recently approved the purchase and delivery of another GPS-guided munition, the ground-launched small-diameter bomb, or GLSDB, that can travel more than 90 miles and be launched from HIMARS and similar launchers. The round was initially designed to be fired from aircraft but has been repurposed.

The head of the Ukrainian military’s missile forces and artillery training, Maj. Gen. Andriy Malinovsky, told The Washington Post in an interview in October that Ukraine’s Western allies had confirmed coordinates for targets ahead of the Kharkiv counteroffensive.

The partners had worked out a process, he said, with Ukraine receiving precise coordinates to ensure they wouldn’t miss their mark with multiple-launch rocket artillery systems as the rapid counteroffensive caught Russian forces unprepared. The targeting information also provided a workaround for when Russian signal-jamming prevented aerial drone reconnaissance on the battlefield, Malinovsky said.

“According to our maps and software, a point will have one set of coordinates,” Malinovsky said. “But when we give this target to partners for analysis, the coordinates are different. Why? Because the Americans and NATO countries have access to military satellites.

“We’re all basically always online,” he added. “They immediately get us the coordinates and we then fire the MLRS right away.”

A third Ukrainian official confirmed that targeting all goes through an American installation on NATO soil and described the process as “very fast.” The Post is withholding the name of the base at the request of U.S. officials who cited security concerns.

READ MORE  In January, demonstrators in Tallahassee protested policies restricting how issues of race are taught in Florida schools. (photo: Alicia Devine/AP)

In January, demonstrators in Tallahassee protested policies restricting how issues of race are taught in Florida schools. (photo: Alicia Devine/AP)

A letter from state officials is likely to fuel controversy over the College Board, which has been accused of stripping or minimizing concepts to please conservatives.

When the final course guidelines were released last week, the College Board had removed or significantly reduced the presence of many of those concepts — like intersectionality, mass incarceration, reparations and the Black Lives Matter movement — though it said that political pressure played no role in the changes. Florida had announced in January that it would not approve the curriculum.

The specifics about the discussions, which occurred over the course of a year, were outlined in a Feb. 7 letter from the Florida Department of Education to the College Board.

READ MORE  Displaced residents sit near their collapsed home as rescue operations continue in Antakya, Turkey, Thursday, Feb. 9, 2023. (photo: Sergey Ponomarev/New York Times)

Displaced residents sit near their collapsed home as rescue operations continue in Antakya, Turkey, Thursday, Feb. 9, 2023. (photo: Sergey Ponomarev/New York Times)

ALSO SEE: As the Earthquake Death Toll Soars, So Does Criticism

of Turkey's Government Response

Most seismologists have a shortlist of places in the world that they worry about — hotspots where any news of a major temblor is a pit-in-the-stomach moment. These concerns are especially true in so-called “seismic gaps,” segments of known fault zones that haven’t ruptured in an unusually long time — long enough that people may have let their guard down.

The East Anatolian fault that ruptured this week in Turkey, for example, was well-known to scientists and government officials, but it had not caused a catastrophic earthquake in at least the last century. Turkey has implemented building codes to protect against earthquake risks, but this week’s tragedy — with a death toll climbing above 19,000 — highlights a long-standing concern among scientists that it isn’t being enforced rigorously enough.

For geoscientists, much of the death and destruction from big quakes is preventable with better building practices. Tragedy can be anticipated with Cassandra-like clarity. But human behavior and investment is often motivated by experience — things that have happened in our lifetimes, or within a few generations. So even when building codes are implemented to safeguard the population, more immediate problems can move to the forefront, which means corners may be cut, and older structures might remain vulnerable.

“I think that’s what’s so nefarious about earthquakes. A particular fault can easily wait many generations and do absolutely nothing — and in matter of seconds to minutes, all hell breaks loose,” said Harold Tobin, a seismologist at the University of Washington. “It’s quite normal for a fault to go several hundred years between earthquakes, so there’s no human recollection of it.”

This is the map of earthquake hazard in Türkiye, produced in 2018 by the national agency AFAD. It shows that the two distinct fault zones for both the M7.8 and the M7.5 were both identified as high hazard. Source: https://t.co/bqvz3rMIly pic.twitter.com/wZQYT8ilId

— Harold Tobin (@Harold_Tobin) February 7, 2023

In addition, the human tendency to want to predict specific hazards may inadvertently put others in a blind spot. For years, scientists have been predicting the “Big One” somewhere along the San Andreas fault in California. There have been several 7.0-magnitude earthquakes in California since the 1990s, but not on that fault.

“We spend a lot of time thinking about those places, because that patch seems locked, loaded and ready to go. When might it break?” said Wendy Bohon, an earthquake geologist based in Maryland. “But there are all these sleeping giants in the world that are accumulating stress and strain more slowly, and we don’t focus as much attention on them just because they are not quite as in-your-face … even though we know they are areas that have high seismic hazard.”

Turkey is a seismically active hot zone, located at a junction where three pieces of Earth’s crust are squeezing against each other. For years, a different fault in Turkey — the North Anatolian fault — has gotten the lion’s share of scientific attention. Large earthquakes have marched westward along the fault, leaving an obvious seismic gap beneath the Sea of Marmara, dangerously close to Istanbul, one of the most populous cities on Earth.

Scientists have calculated and recalculated the likelihood of a massive quake there in the next few decades, often saying it’s when, not if, catastrophe will strike.

By contrast, the East Anatolian fault had experienced a more modest handful of 6.0-magnitude earthquakes during the relatively brief era of modern seismic monitoring, which started in the 1960s. In 2020, Karasözen and a team of scientists published a detailed study of a 6.8-magnitude quake caused by a rupture in the fault, also highlighting historic earthquakes along the fault in the late 1800s that had been reconstructed from damage patterns and reports of shaking.

This week’s 7.8-magnitude earthquake was therefore entirely expected, but also a little surprising to scientists because it was so massive, packing a more powerful punch than anticipated. Earthquakes are measured on a logarithmic scale, which means the difference between a 6.8 and a 7.8 is bigger than it sounds. One whole number increase on the scale creates seismic waves with 10 times the amplitude, releasing 32 times the energy.

“We knew the potential of this fault,” Karasözen said. “We knew how deadly it could get.”

But even scientists who draw on seismological data, historical and indigenous accounts and paleoseismology studies can sometimes see patterns clearly only after a quake has occurred.

“Sometimes the earthquake is bigger than you expect,” said Michael Steckler, a geophysicist at Columbia Climate School’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. He noted that in Tohoku, Japan, there was a baseline expectation of a 7.0- to 7.5-magnitude earthquake, but in 2011 a deadly 9.0-magnitude quake caused a tsunami and widespread devastation. “In retrospect, it now turns out that area has a magnitude 9 [earthquake] about every thousand years,” he said.

Even though scientists cannot predict or prevent earthquakes, they do know how to prevent deaths — which is what makes it so painful to see these events in different parts of the world.

“The old saying is: ‘Earthquakes don’t kill people, buildings kill people.’ It’s heartbreaking, especially when you see a building that was built properly holding up and the one next door is completely collapsed,” said Tom Parsons, a geophysicist with the U.S. Geological Survey.

What may cause scientists the most anguish is that even when building codes exist, people remain at risk because regulations may not be followed or enforced.

Mustafa Erdik, who founded the department of earthquake engineering at Boğaziçi University in Istanbul, said in an email that problems in Turkey lie in the “degree of conformity with the code.”

“We use building codes that reflect the state-of-engineering,” Erdik said. “Damage is expected after such large earthquakes. But the type of damage (floors piled up on each other) should not have taken place.”

On Twitter, Karasözen shared a recent real estate listing on social media from Malatya, Turkey, that stated a property was in compliance with earthquake standards. That building crumbled this week.

“As geoscientists and engineers, WHAT CAN WE DO MORE?!” she tweeted.

We know the earthquake-prone regions in Turkey, and we have the proper building codes. The issue is execution. Here's an example of that. This apartment (flat) posting is recent, from a couple of days ago. 1/3 pic.twitter.com/N9Pcqs8lWS

— ezgikarasozen (@ezgikarasozen) February 7, 2023

Which areas of the world scientists worry about most varies. Bohon holds special concern for Haiti, where population density, seismic risk and vulnerable building stock can have catastrophic consequences — the country has been hit twice by major earthquakes since 2010 and is still recovering. Tobin sees major risks in Kathmandu, which experienced a 7.8-magnitude earthquake in 2015. Steckler is worried about a major quake in densely populated Bangladesh.

And Karasözen thinks often about Turkey, but also Iran, where there are similar fault systems. Her work has focused on filling in gaps in crucial data that are needed to understand active faults.

Normally after a quake in Turkey, Karasözen checks in with family and friends and then dives into the science, immersing herself in the physics of seismic wave propagation, postseismic deformation, aftershocks. She’s proud that her work can help her home country.

This time, she can’t bring herself to look at the data yet. She’s putting her energy into fundraising, instead.

“Of course it’s an interesting earthquake,” she said. “This one is different. Seeing all of the tweets [from people trapped] under the rubble … It’s just too much.”

READ MORE  Five Memphis police officers were fired in connection with a traffic stop that led to the death of Tyre Nichols. Clockwise from top left: Tadarrius Bean, Demetrius Haley, Emmitt Martin III, Desmond Mills Jr. and Justin Smith. (photo: AP)

Five Memphis police officers were fired in connection with a traffic stop that led to the death of Tyre Nichols. Clockwise from top left: Tadarrius Bean, Demetrius Haley, Emmitt Martin III, Desmond Mills Jr. and Justin Smith. (photo: AP)

District Attorney Steve Mulroy did not say how many cases would be scrutinized but said the review would include both closed and pending cases.

District Attorney Steve Mulroy did not say how many cases would be reviewed but said in a statement that it would include both closed and pending cases.

The five former officers were also added to the county’s list of law enforcement officers whose credibility has been questioned, Mulroy said.

Tadarrius Bean, Demetrius Haley, Emmitt Martin III, Desmond Mills, Jr. and Justin Smith were charged last month with second-degree murder, kidnapping, official misconduct and official oppression in connection with the brutal Jan. 7 assault on Nichols.

Body and police camera video footage captured the beating, which led to his death three days later, igniting outrage across the country.

Despite claims that Nichols was stopped for reckless driving, the Memphis police chief later said there was no evidence to substantiate those allegations.

All of the officers charged were members of a special crime-fighting force called Scorpion that was disbanded shortly after Nichols’ killing. The unit had made hundreds of arrests within the first few months of its launch in 2021, Mayor Jim Strickland said in an address to the city last year.

Though the unit was created to combat violent crime, some residents say they have been stopped by Scorpion officers for minor, nonviolent offenses.

A 22-year-old Memphis man, Monterrious Harris, filed a federal lawsuit this week claiming Scorpion officers had beaten him just days before Nichols was assaulted.

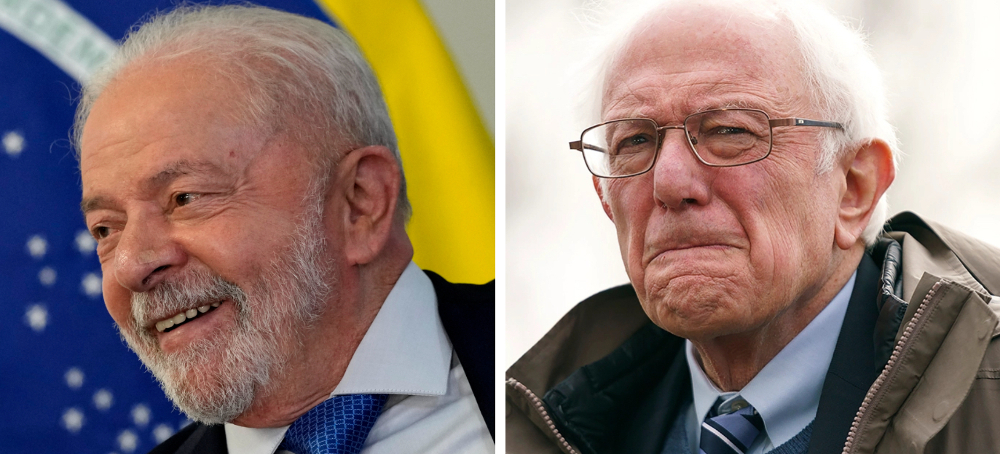

READ MORE  Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva will meet with Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) during his visit to Washington, D.C., on Friday. (photo: Greg Nash/Getty)

Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva will meet with Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) during his visit to Washington, D.C., on Friday. (photo: Greg Nash/Getty)

Sanders was a vocal advocate for Lula’s freedom after he was jailed over corruption charges in April 2018.

“As President, Lula has done more than anyone to lower poverty in Brazil and to stand up for workers,” Sanders said in a tweet when Lula was released in November 2019, after the Brazilian Supreme Court ruled that he could not be imprisoned while appeals were still pending.

“I am delighted that he has been released from jail, something that never should have happened in the first place,” Sanders added.

Sanders, who was a Democratic presidential candidate at the time, called Lula after his release. During the conversation the Brazilian president reportedly told Sanders he was rooting for him to win the 2020 election.

Lula previously served as president of Brazil from 2003 to 2010. He was favored to win the 2018 presidential election but was blocked from running by his conviction, according to The Associated Press. Former President Jair Bolsonaro would go on to win the 2018 election.

The Brazilian Supreme Court confirmed a lower court ruling overturning Lula’s conviction in April 2021, which Sanders touted as an “important victory for democracy and justice in Brazil.” Lula secured his second presidency after defeating Bolsonaro in a tight run-off election in October.

Lula is traveling to Washington, D.C., this week to meet with President Biden, who extended an invitation as a sign of support after Bolsonaro’s supporters stormed the country’s Congress, Supreme Court and presidential palace on Jan. 8.

Biden spoke with Lula the day after the riot, condemning it as an “attack on democratic institutions and on the peaceful transfer of power” and offering the invitation for a visit. The two leaders are expected to discuss the U.S.’s support for Brazil’s democracy and efforts to promote democratic values worldwide, among other issues.

Sanders did not respond to a request for comment about his visit with Lula on Friday.

READ MORE  From riot gear to PR to Dairy Queen, records detail every expense Enbridge reimbursed after the Line 3 protests. (photo: Kerem Yucel/Getty)

From riot gear to PR to Dairy Queen, records detail every expense Enbridge reimbursed after the Line 3 protests. (photo: Kerem Yucel/Getty)

From riot gear to PR to Dairy Queen, records detail every expense Enbridge reimbursed after the Line 3 protests.

Nelson drove 30 minutes to Hubbard County, where he and officers from 14 different police and sheriff’s departments confronted around 500 protesters, known as water protectors, occupying a pipeline pump station. The deputy spent his day detaching people who had locked themselves to equipment as fire departments and ambulances stood by. A U.S. Customs and Border Protection helicopter swooped low, kicking dust over the demonstrators, and officers deployed a sound cannon known as a Long Range Acoustic Device in attempts to disperse the crowd.

By the end of the day, 186 people had been detained in the largest mass-arrest of the opposition movement. Some officers stuck around to process arrests, while others stopped for snacks at a gas station or ordered Chinese takeout before crashing at a nearby motel.

These latter details might be considered irrelevant, except for the fact that the police and emergency workers’ takeout, motel rooms, riot gear, gas, wages, and trainings were paid for by one side of the dispute — the fossil fuel company building the pipeline, which spent more than $79,000 on policing that day alone.

When the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission gave Enbridge permission in 2020 to replace its corroded Line 3 pipeline and double its capacity, it included an unusual condition in the permit: Enbridge would pay the police as they responded to the acts of civil disobedience that the project would surely spark. The pipeline company’s money would be funneled to law enforcement and other government agencies via a Public Safety Escrow Account managed by the state.

By the time construction finished in fall 2021, prosecutors had filed 967 criminal cases related to pipeline protests, and police had submitted hundreds of receipts and invoices to the Enbridge-funded escrow account, seeking reimbursement. Through a public records request, Grist and the Center for Media and Democracy have obtained and reviewed every one of those invoices, providing the most complete picture yet of the ways the pipeline company paid for the arrests of its opponents — and much more.

From pizza and “Pipeline Punch” energy drinks, to porta potties, riot suits, zip ties, and salaries, Enbridge poured a total of $8.6 million into 97 public agencies, from the northern Minnesota communities that the pipeline intersected to southern counties from which deputies traveled hours to help quell demonstrations.

By far the biggest set of expenses reimbursed from the Enbridge escrow account was over $5 million for wages, meals, lodging, mileage, and other contingencies as police and emergency workers responded to protests during construction. Over $1.3 million each went toward equipment and planning, including dozens of training sessions. Enbridge also reimbursed nearly a quarter million dollars for the cost of responding to pipeline-related human trafficking and sexual violence.

Reporters for Grist and the Center for Media and Democracy reviewed more than 350 records requested from the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission, pulling out totals described in invoices and receipts and dividing them into categories such as equipment, wages, and training. Each agency had its own method for tracking expenses, with varying levels of specificity. In cases where reporters were unable to cleanly disentangle different types of expenses, those expenses were categorized as “other/multiple.” Generally, totals should be considered conservative estimates for each category.

The $79,000 that Enbridge paid for the single day of arrests on June 7, which doesn’t include much of the Enbridge-funded equipment and training many officers relied on, displays the wide range of activities and agencies Enbridge’s money touched. The attorney’s office of Hubbard County, where the protest took place, even attempted to get Enbridge to reimburse $27,000 in prosecution expenses. In other words, the area’s top arbiter of justice assumed that Enbridge would be covering the cost of pursuing charges against hundreds of water protectors. (The state-appointed escrow account manager denied the request.)

Some of the most surprising Enbridge invoices were from institutions and officials associated with protecting Minnesota’s environmental resources and preserving a balance between industry and the public interest. No agency received more escrow account money than the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, or DNR, which is also one of the primary agencies monitoring Line 3 for environmental harms. Of the $2.1 million that the DNR received, the funds were mainly used to respond to protests and train state enforcement officers about how to wrangle protesters, in some cases before construction had even begun. Conservation officers joined police on the front lines of protests, on the pipeline company’s dime.

The Aitkin County-run Long Lake Conservation Center, one of the oldest environmental education centers in the U.S., provided facilities to police to the tune of over $40,000, which the sheriff’s office paid using Enbridge funds. And a public safety liaison hired to coordinate among Enbridge, the Public Utilities Commission, and local officials was paid $120,000 in salary and benefits by the pipeline company over a year and a half.

The invoices also document, in unusual detail, the connection between fossil fuel megaproject construction and violence against women: Enbridge reimbursed a nonprofit organization for the cost of hotel rooms for women who had reportedly been assaulted by Line 3 workers. The pipeline company also helped pay for two sex trafficking stings conducted by the Minnesota Human Trafficking Investigative Task Force, leading to the arrest of at least four Line 3 pipeline workers.

The state of Minnesota also considered police public relations to be expenses eligible for Enbridge funding. John Elder, at the time spokesperson for the Minneapolis Police Department, put out police press releases and responded to journalist queries on behalf of the Northern Lights Task Force, which was set up to coordinate emergency response agencies throughout the protests. Enbridge ultimately reimbursed the St. Louis County Sheriff’s Office for 331 hours of his work at a wage of $80 per hour. (St. Louis County Sheriff Gordon Ramsay said he was not in office during pipeline construction and could not comment on Line-3-related work, and Elder did not respond to requests for comment.)

A year earlier, Elder had handled Minneapolis police PR when one of the city’s officers killed George Floyd, sparking an unprecedented wave of nationwide protests. Elder was behind the notorious press release stating that Floyd had “physically resisted officers” and died after he “appeared to be suffering medical distress.” Hours later, a bystander video went viral, showing that the medical distress followed an officer pressing his knee on Floyd’s neck for more than nine minutes. Fallout from the press release did not stop law enforcement agencies from choosing Elder to lead officials’ public relations surrounding the Line 3 protests.

Water protectors contend that the state of Minnesota’s arrangement with Enbridge trampled their constitutional rights. With 97 criminal cases unresolved across the state, five defendants in Aitkin County are pursuing motions arguing that the escrow account created an unconstitutional police and prosecutor bias that violated their rights to due process and equal protection under the law. They want the charges dismissed. Attorneys with the Partnership for Civil Justice Fund’s Center for Protest Law and Litigation previously used the defense against charges filed by Hubbard County that were ultimately dismissed. They’re now preparing a separate civil lawsuit challenging the use of the escrow account on constitutional grounds.

Winona LaDuke, an Anishinaabe activist and founder of the Indigenous environmental nonprofit Honor the Earth, is among those arguing in court that charges should be thrown out. Aitkin County, the jurisdiction behind the allegations she’s fighting, was reimbursed $6,007.70 for wages and benefits on just one of the days she was arrested. LaDuke believes the money amped up the police response.

“They were far more aggressive with us, far more intent on finding any possible reason to stop somebody,” she said. “Law enforcement is supposed to protect and serve the people. They work for Enbridge.”

LaDuke added that she believes the DNR’s Enbridge money represents a “conflict of interest.” In addition to its role in monitoring the pipeline’s full Minnesota route, the agency is directly responsible for the ecological health of 35 miles of state lands and 66 waterways where Line 3 crosses — and where Anishinaabe people have distinct treaty rights to hunt, gather, and travel. To date, the DNR and the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency have charged Enbridge over $11 million in penalties for violations that include dozens of drilling fluid spills and three aquifer breaches that occurred during construction. LaDuke and others have criticized the agency’s response to the incidents, noting that it took months to publicly disclose the first of the aquifer breaches.

Juli Kellner, an Enbridge spokesperson, emphasized that the escrow account was operated by an independent manager who reported to the Public Utilities Commission, not the oil company. Kellner said the account was created to relieve communities from the increased financial burden that public safety agencies accrued when responding to protests.

“Enbridge provided funding but had no decision-making authority on reimbursement requests,” she said.

Ryan Barlow, the Public Utilities Commission’s general counsel, said the commission had no comment about the appropriateness of specific expenses: “If expenses met the conditions of the permit they were approved; if they did not, they were not approved.”

In a statement, the DNR said that receiving reimbursement from Enbridge does not constitute a conflict of interest: “At no time were state law enforcement personnel under the control or direction of Enbridge, and at no time did the opportunity for reimbursement for our public safety work in any way influence our regulatory decisions.”

When asked why its officers were trained how to use chemical weapons ahead of the protests, the DNR said their peace officers’ overall mission is “protecting Minnesota’s natural resources and the people who use them” and that such equipment, while occasionally necessary, “is not used as part of conservation officers’ routine work.”

Hubbard County Sheriff Cory Aukes said his agency’s response was dictated by the protestors and water protectors. “If they want to block roads, threaten workers, and cause $100,000 worth of damage to Enbridge equipment, well, we have a job to do, and we did it,” Aukes said, adding that Enbridge is a taxpayer that officers have a duty to protect. “Enbridge is a big taxpayer in Hubbard county and we would be doing an injustice if we didn’t support them as well.”

“We were in the middle,” added Aitkin County Sheriff Dan Guida. “There were probably times when it seems like we dealt with water protectors in a more criminal way, but they were the ones breaking the law.” He added that officers had no knowledge of the reimbursement plan and that the funds spared taxpayers the cost of policing the pipeline.

Long Lake Conservation Center manager Dave McMillan, on the other hand, said he knew the money the Aitkin County Sheriff’s Office paid his organization for police officer lodging would come from Enbridge. “My concern was not wanting to become a pawn or a player in this political battle. In the same token, we said if any of the organizations that were protesting said they wanted to come here and use our facilities, we would have said yes,” he said. Enbridge’s connection to the facility runs even deeper: The company’s director of tribal engagement sits on the board of the Long Lake Conservation Foundation, which helps fund the county-run facility.

With energy infrastructure fights brewing over liquid natural gas terminals in the Southeast, lithium mining in the West, and the Enbridge-operated Line 5 pipeline in Wisconsin and Michigan, the ongoing legal cases that have ensnared the water protectors will help decide whether or not the public safety escrow account will be replicated elsewhere.

“Our concern is that this now will become the model for deployment nationwide against any community that is rising up against corporate abuse,” said Mara Verheyden-Hilliard, the director of the Center for Protest Law and Litigation, who is representing some of the water protectors. “It becomes very easy to sell this to the public as a savings for taxpayers, when instead what they’re doing is selling their police department to serve the pecuniary interests of a corporation.”

Long before Line 3 construction began, Anishinaabe-led water defenders promised they would rise up if the expanded pipeline was permitted. Members of the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission warily looked west to North Dakota, where in 2016 and 2017 public agencies spent $38 million policing massive protests led by members of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe against construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. With global concerns about climate change and biodiversity reaching a fever pitch, building an oil pipeline now came with a hefty civil disobedience bill, and the commissioners did not want taxpayers to foot it.

According to the pipeline permit, finalized in 2020, whenever a Minnesota public safety agency spent money on almost anything related to Line 3, they could submit an invoice, and Enbridge would pay it. Nonprofits responding to drug and human trafficking were also eligible for grants from the account. To create a layer of separation between police and the Enbridge money, the state hired an account manager to decide which invoices would be fulfilled.

Minnesota wasn’t the only state considering this kind of account. In 2019, South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem passed a law designed to establish “the next generation model of funding pipeline construction.” The law created a fund for law enforcement and emergency managers responding to pipeline protests, paid partly by new rioting penalties, but also with as much as $20 million from the company behind the pipeline. Noem’s office collaborated on the legislation with TransCanada, now known as TC Energy, which was preparing to build the controversial Keystone XL tar sands oil pipeline. But with Keystone XL defunct after President Joe Biden pulled a key permit in 2021, only Minnesota would have the opportunity to fully test the new model.

Even beforeLine 3 received its final permit on November 30, 2020, more than $1 million in reimbursement-eligible expenses had been spent. Sheriffs’ offices were already buying riot gear and conducting crowd control trainings in 2016 and 2017, in anticipation of the protests.

Key to coordinating it all was the Northern Lights Task Force, established in September 2018 and consisting of law enforcement and other public officials from 16 counties along the pipeline route or otherwise hosting Enbridge infrastructure, as well as representatives from nearby reservations and state agencies. Task force members met at least a dozen times before construction began, the invoices show, and at times Enbridge representatives joined. It didn’t necessarily matter, however, whether Enbridge was physically in the room, because the company’s money was always there: For the law enforcement agencies that requested it, the corporation paid wages and overtime for each Northern Lights Task Force meeting attended.

David Olmstead, a retired Bloomington police commander appointed by the Minnesota Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Management to fulfill the duties of the Line 3 public safety liaison, coordinated between Enbridge and public officials. Enbridge reimbursed the homeland security agency Olmstead’s salary and benefits as well as more than $20,000 in lodging expenses that Olmstead charged to a credit card, which included a room at Duluth’s Fairfield Inn that was rented for two straight months at the height of protests in June and July 2021, for a nightly rate of $165.

Olmstead, who did not respond to requests for comment, helped set up a network of emergency operations centers to be activated when protests kicked off. He also worked with task force members as they arranged dozens of training sessions. Although a large proportion focused on crowd control tactics, others covered techniques for dismantling lock-downs, responding to weapons of mass destruction, policing sex trafficking, upholding the constitution, understanding Native American culture, and using lessons learned from policing the Dakota Access Pipeline. Public officials spent over $950,000 of Enbridge’s money on training expenses, including meals, lodging, mileage, training fees, and wages.

Three quarters of the Enbridge training money went to the Department of Natural Resources. The agency’s enforcement division is not only responsible for upholding environmental laws and ticketing deviant poachers and recreational vehicle drivers, but it also has full police powers on state lands. While riot control may not be in the typical job description of a Minnesota conservation officer, previously known as a game warden, dozens of them trained to control crowds and use less-lethal chemical weapons.

The Enbridge fund wasn’t supposed to be primarily for stuff. To limit purchases, Public Utilities Commission members added language in the permit stipulating that public agencies could only use it to buy personal protective equipment, or PPE.

Over half of PPE funds went toward riot gear valued at more than $700,000, which was purchased from police equipment vendors like Streicher’s and Galls. For 13 county and city police forces, that meant more than $5,000 in riot suits, shields, and gas masks. The Beltrami County Sheriff’s Office took over $70,000 for riot gear, and the Polk County Sheriff’s Office more than $50,000. (Neither office responded to requests for comment.) However it was state agencies that received more than half of the Enbridge reimbursements for crowd control equipment: more than $200,000 for the Minnesota State Patrol, and over $170,000 for the Department of Natural Resources.

Enbridge also covered more than $325,000 in clothing — mostly cold weather apparel — as well as over $55,000 for hand, foot, and body warmers. Even the identification patches worn on many deputies’ lapels were paid for by Enbridge — totaling more than $7,000. Another $2,000 went toward porta potty rentals, and over $12,000 more toward gear to protect police as they detached protesters who had locked themselves to equipment, including face shields and flame-proof blankets to guard against flying sparks.

Enbridge paid not only for the time the Sheriff’s deputies took to arrest water protectors and bind their hands behind their backs, but also for the handcuffs themselves, which were dubbed PPE and paid for by the pipeline company. The state of Minnesota approved more than $12,500 in Enbridge funds for zip ties and handcuffs.

“Less lethal” weapons did not count as personal protective equipment, the account manager decided, to the frustration of some law enforcement leaders. However, even though Enbridge couldn’t buy these weapons, the company did cover trainings on how to use them. Several trainings were provided by the tear gas manufacturer Safariland, costing thousands of dollars. Enbridge also reimbursed over $260,000 worth of gas masks and attachments, including filters for tear gas, presumably to protect law enforcement from the chemicals they themselves would be deploying.

It wasn’t necessarily the counties with the heaviest protest activity that purchased the most equipment using Enbridge money. Among the top five local law enforcement equipment buyers was the Freeborn County Sheriff’s Office, located in one of Minnesota’s southernmost counties. The agency’s only Enbridge-related expense besides equipment was for three officers to spend a two- to three-day deployment assisting other agencies along the pipeline route in the northern part of the state. (The office did not respond to requests for comment.)

2021 was a year of unprecedented protest among Northern Minnesota’s pristine lakes and wetlands. Enbridge and law enforcement faced a drumbeat of road blockades, lockdowns to pipeline equipment, marches through remote prairie, and layered demonstrations combining Anishinaabe ceremony with direct action tactics refined by generations of environmental and Indigenous social movements.

The biggest Enbridge escrow account expense was more than $4.5 million in wages, benefits, and overtime for officials responding to perceived security threats during construction. More than just police and sheriff’s offices were involved: The Department of Natural Resources’ largest Enbridge-funded expense was $870,000 in personnel costs during construction.

And it wasn’t just calls for service that Enbridge paid for. Dozens of invoices mentioned “patrols,” where law enforcement would drive up and down the pipeline route or surveil places occupied by pipeline opponents.

The Cass County Sheriff’s Office’s “proactive” safety patrol, described in an invoice, may help explain why that agency expensed far more money for response costs to the escrow account — over $900,000 — than any other county or city, despite facing fewer mass demonstrations than other areas.

Like Cass, Hubbard County at times instituted patrols as well as mandatory overtime shifts. The invoices confirm that sheriff’s deputies surveilled the Namewag camp, which was located on private land and used both as a space for Anishinaabe land-based practices and as a jumping off point for direct action protests. “On 3/6 and 3/7, Hubbard County Deputies observed roughly 30 previously unidentified vehicles arriving and periodically leaving the Hinds Lake Camp (Ginew [sic] Collective Camp) in Straight River Township, Hubbard County,” one invoice states.

It goes on to describe intelligence shared by an Enbridge employee, detailing the movements of various groups of pipeline resistors. “Migizi camp [another anti-Line 3 encampment] is empty at this time and intelligence suggests Migizi and Portland XR [short for Extinction Rebellion] are camping at a public campground,” the message from Enbridge stated.

Enbridge also paid for gas that fueled officers’ cars, hotels they stayed in when assisting other jurisdictions, and food they ate during shifts. During both planning stages and periods of law enforcement action, Enbridge covered at least $150,000 in meals, snacks, and drinks.The oil company bought bagels, Domino’s pizza, McNuggets, Subway sandwich platters, a Dairy Queen strawberry sundae, summer sausage, cheese curds, deep fried pickles, Fritos, Gatorade, and energy drinks, including one called Pipeline Punch.

From planning through construction, police and sheriff’s offices together received at least $5.8 million in Enbridge funds. For state agencies, the Enbridge funds represented a tiny proportion of massive budgets. However, for the Cass County Sheriff’s Office, the Enbridge money added up to the equivalent of more than 10 percent of the office’s 2021 budget. (The office did not respond to requests for comment.) Five other sheriff’s offices received reimbursements equivalent to over 5 percent of their annual budgets.

The range of choices law enforcement agencies made regarding what to invoice makes clear the discretionary nature of the Line 3 response. Clearwater County is home to one of two places where Line 3 crosses the Mississippi River and the site of a number of protests. Although 20 other law enforcement agencies billed Enbridge for assisting the local sheriff, Clearwater County billed nothing to the pipeline company.

The invoices also offer insight into the way the influx of pipeline workers translated into incidents of human trafficking and assault. “Since the Line 3 Replacement project has come to our area, we have experienced an increase in calls and need for services,” reads a grant application from the nonprofit Violence Intervention Project, or VIP, based in Thief River Falls, Minnesota, a community through which the pipeline passes, just outside the Red Lake Reservation. “We have provided services to several victims that have been assaulted by employees working on the Enbridge line 3 project.”

Enbridge reimbursed the organization for two hotel rooms for assault survivors, since VIP’s shelter was full at the time. The company also paid $42,000 worth of hazard pay for shelter workers during the 2021 winter, due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Enbridge’s biggest human trafficking grant recipient was Support Within Reach, a northern Minnesota organization that works with survivors of sexual violence, which used the money to pay for extra personnel costs during pipeline construction and to buy emergency cell phones for advocates.

Additional funds also went to public agencies: Enbridge reimbursed $43,551.96 to local law enforcement agencies working with the Minnesota Human Trafficking Investigative Task Force. The documents describe at least two multi-agency operations in Grand Rapids and Bemidji, and news reports from the time confirm that they led to the arrest of four Line 3 workers.

Kellner, the Enbridge spokesperson, said that any employee caught and arrested for human trafficking would be fired by the company. She added that the four workers who were arrested were subcontractors, not direct employees of the oil company, and were fired by the contractor Enbridge worked with.

The Link, a nonprofit based in North Minneapolis, received $36,870 from Enbridge and used it in part to assist the task force with sting operations and support survivors who were found. Beth Holger, the organization’s chief executive officer, said she did not feel conflicted about taking Enbridge’s money, because it was going to victims: “Yes we took money from a corporation that has caused harm, and we’re giving it to people to help with that harm.”

The $8.6 million in expenses covered by Enbridge by no means accounts for the full public cost of responding to opposition to the Line 3 pipeline.

Several sheriffs’ offices anticipated thousands more Enbridge dollars than they received. The sheriffs’ offices in Cass, Beltrami, and Polk counties each attempted to expense around $25,000 of equipment that was ultimately denied reimbursement.

Hubbard County Sheriff Cory Aukes said that it was unfortunate that the Hubbard county attorney’s request for prosecutorial funds was denied by the account manager, as Aukes sees the influx of charges and protestors as an undue burden on the attorney’s office as well as the sheriff’s office. He said that his agency had plenty of other expenses that weren’t covered.

He added that he believes it would be fiscally irresponsible to decline Enbridge’s funds. “Shouldn’t they have to fund that? Shouldn’t they be responsible to reimburse these additional costs?” Aukes asked.

To water protectors, however, the greatest costs of the pipeline are its consequences for the climate, water, and the Canadian forest ecosystem decimated by tar sands oil production. The nonprofit LaDuke co-founded, Honor the Earth, issued its own invoice to Enbridge before the creation of the escrow account, estimating that Line 3 would cost $266 billion annually in environmental losses and social damages.

So far, she hasn’t received a response.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

LOTS OF POSTS IGNORED BY BLOGGER..... ALL POSTS ARE AVAILABLE ON MIDDLEBORO REVIEW AND SO ON DOJ Deleted an Epstei...