21 February 23

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

I WISH MORE PEOPLE WOULD DONATE. I'M A SOCIAL WORKER ... and we all know social workers don't earn much -- and 75 years old, and I donate $48 monthly, more than three times what it costs for home delivery of the Washington Post, I just gave RSN an extra $100 this evening because I felt somebody had to do something. C'mon, loyal readers -- help out just a little more!

Katie, RSN Reader-Supporter

Sure, I'll make a donation!

How James O'Keefe Lost the Project Veritas Civil War

Andrew Rice, New York Magazine

Rice writes: "James O'Keefe, the hidden-camera sting artist whose deceptive practices scandalized journalism and thrilled his audience of hard-core conservatives, has formally left Project Veritas, the nonprofit media organization he created."

James O’Keefe, the hidden-camera sting artist whose deceptive practices scandalized journalism and thrilled his audience of hard-core conservatives, has formally left Project Veritas, the nonprofit media organization he created.

Reached on his cell phone on Monday, a few minutes before his ouster became official, O’Keefe refused to discuss whether he was preparing to exit. Members of the Project Veritas board either did not return messages or declined to comment on rumors. “I can’t,” said longtime board member George Skakel before hanging up the phone. A Twitter post by Neil McCabe, a former Project Veritas spokesman who now works for the One America News Network, reported on Monday that O’Keefe “read his resignation letter to his former team and board members at their Mamaroneck, N.Y. headquarters” on Monday morning. However, R.C. Maxwell, a Project Veritas spokesman who is close to O’Keefe, tweeted later on Monday that O’Keefe had not resigned but rather had been “removed from his position as CEO by the Project Veritas board.”

O’Keefe subsequently posted a video of his speech announcing his departure to his employees. In a public statement released Monday evening, the Project Veritas board of directors denied it had terminated O’Keefe, claiming he had instead been “suspended indefinitely” pending the “resolution of a fulsome investigation” into what it described as “financial malfeasance.” Nonetheless, the board said it was still seeking to “continue conversations with James to resolve internal matters rather than litigate them publicly.”

“He quit,” Skakel wrote in a follow-up text after this story was initially published online. “He was not forced out.”

Whatever the truth of the messy circumstances, O’Keefe has left the organization after a two-week period of turmoil. During that time, Project Veritas has been divided between a group of O’Keefe loyalists and a large group of dissenters on the staff and board who chafed at the founder’s erratic management style, spending, and penchant for costly confrontation with ideological adversaries and his own employees. O’Keefe was placed on paid leave in early February after what people close to the organization described as a blowup in which he summarily fired a pair of top employees, including the group’s chief financial officer. News of the action — and rumors that O’Keefe was about to be fired — sparked a viral backlash among O’Keefe’s large number of fans on social media, many of whom posted that there was “no Project Veritas without James O’Keefe.” An attorney representing Project Veritas donors reportedly wrote a letter to the board threatening legal action if O’Keefe were to be removed. Meanwhile, O’Keefe was apparently hiking in Santa Monica with the anti-vaccine activist Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who posted a scenic tweet as proof of life.

On February 15, the nonprofit’s executive director, Daniel Strack, posted a conciliatory letter, saying that “James has not been removed from Project Veritas” and avowing that members of the nonprofit’s board “all love James.” Sources familiar with the organization’s internal workings said, however, that a battle was raging behind the veneer of civility. One source said that an internal messaging system used by employees had turned into “an all-out brawl” and a “civil war,” as O’Keefe’s partisans attacked a faction of employees who had signed a highly detailed letter of complaint that described their boss as a “power drunk tyrant.” In his speech to his staff on Monday, O’Keefe said he wrote a letter to all the members of the board, saying that if they did not resign en masse, he would be “forced to walk away.” Strack later reportedly described the message as an “ultimatum.”

“I have received increasingly emotional and irrational outreaches from various parties pushing me to ‘negotiate’ a resolution to a situation that was caused solely by the planned actions of the board and the executive team addressed on this email,” O’Keefe wrote. He said he had concluded that the board had been “planning its actions to remove me from a management position well in advance” of its decision to place him on leave in early February.

“I cannot in good conscience return to such a mismanaged organization,” O’Keefe wrote. “The board members and the officers addressed here have each individually and as a group absolutely failed Project Veritas, its employees and me as both an employee and fellow board member. You have created an embarrassing public display by leaking Project Veritas confidential information. I have not responded privately or publicly because there is no rational appropriate response to the emotional circus that has been created by your actions.”

He gave board members a deadline of last Friday to comply with his resignation demand. They refused. In his speech on Monday, O’Keefe said that he had clashed with the board over a number of issues related to his management and personal behavior, including his use of private jets and questions “about girls I’ve dated in the past.” He said one officer of the nonprofit had sent a message to the board filled with “bizarre innuendo and hyperbole” about expenses he had charged to the organization. “These included, and you can’t make this up, that Project Veritas paid for James O’Keefe’s down payment of his wedding,” O’Keefe said. “I got a chuckle out of this. I’m not married.” (In fact, O’Keefe reportedly invited a host of Republican stars, including Donald Trump Jr. and Clarence Thomas, to a wedding planned for May 2020, which was later called off.) O’Keefe said the $12,000 expense was actually for a Project Veritas holiday party.

O’Keefe also questioned the timing of the move against him, asking why he had been forced out soon after “we broke the biggest story in our organization’s history” — referring to an undercover sting operation against Pfizer. Project Veritas claims its videos reveal that the pharmaceutical company is conducting gain-of-function research as part of its vaccine science, a charge Pfizer strongly denies. O’Keefe’s supporters online have blamed Big Pharma for his sudden ouster. “None of this makes any sense, and why is it all happening right now?” O’Keefe asked. “I don’t have answers. You guys are journalists. Maybe you can go find the answers.”

In its statement, the board said it “wants to work things out with James, and has tried every route possible to remedy the issues at hand,” but had a “legal obligation to comply with state and federal law” that governs spending at nonprofit organizations. The board said O’Keefe’s firing of the CFO (who was later reinstated) “left us no choice but to suspend him.” As examples of O’Keefe’s spending on “personal luxuries,” the statement listed $60,000 related to “dance events” where O’Keefe performed routines dramatizing his life; a $14,000 charter-plane flight to meet with someone concerning repairs to his sailboat, the Lucky Charm III; $150,000 in expenses related to “black cars”; and “hundreds of other acts of personal inurement.” It said that O’Keefe had shown up at the office on Presidents’ Day, a company holiday, to stealthily “remove his belongings” from the office, where he displays many mementos of his career, including a chinchilla stole that he wore in his first big sting, against the progressive community group ACORN, back in 2009.

In his video, O’Keefe told his staff that he was packing up his personal effects. “I’m sorry, I’m getting emotional,” he said, his voice cracking. “I’m intending to start anew.”

O’Keefe’s departure leaves the future of Project Veritas in serious doubt. His celebrity and flair for self-promotion turned the nonprofit — originally founded in his parents’ carriage house — into a large and well-financed media organization with an annual budget of roughly $20 million at its peak in 2020. Since then, however, its fortunes have taken a sharp downward turn. Last year, it lost a trial in a civil case brought by a Democratic campaign organization that Project Veritas infiltrated during the 2016 presidential campaign. (O’Keefe has said he will appeal the verdict.) Similar lawsuits are making their way through the courts. A federal criminal investigation related to Project Veritas’ purchase of a diary stolen from Ashley Biden, the president’s daughter, is looming over O’Keefe and others who worked on the investigation. According to its publicly filed federal tax returns, the nonprofit has been spending millions of dollars on lawyers to defend itself and O’Keefe personally. In recent months, the organization has been showing signs of financial stress, laying off rank-and-file employees. The board’s statement said its “serious concern” about the company’s “financial health” was a major source of its conflict with O’Keefe.

“Their burn rate is unreal,” says a source familiar with the organization’s operations. “They’re going through like a million bucks a month.”

Without O’Keefe, Project Veritas will likely struggle to raise money, placing the ongoing existence of the organization in peril. O’Keefe, however, appears to have been preparing for his next act. On Friday, according to corporate records, a company called Transparency 1, LLC was formed in Delaware. Its ownership was not disclosed, but one source says that the LLC was rumored to be a new corporate vehicle established by O’Keefe.

READ MORE

U.S. Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR), chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, during a nomination hearing on February 15, 2023, in Washington, D.C. (photo: Kevin Dietsch/Getty)

U.S. Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR), chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, during a nomination hearing on February 15, 2023, in Washington, D.C. (photo: Kevin Dietsch/Getty)

A Top Senate Democrat Has an Extraordinarily Radical Plan to Deal With Trump's Worst Judge

Ian Millhiser, Vox

Millhiser writes: "What if the Biden administration simply ignored court orders from the most partisan Republican judges?"

What if the Biden administration simply ignored court orders from the most partisan Republican judges?

On Thursday, Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR) proposed a radical solution to the possibility that a medication used in more than half of all abortions soon becomes banned. Should Matthew Kacsmaryk, a Trump-appointed judge who is widely expected to hand down a court order banning the drug, end up doing so, Wyden says that the Biden administration should simply ignore that decision.

Wyden offered this proposal at the end of a speech on the Senate floor, where he also laid out several reasons why the lawsuit attacking this abortion drug, mifepristone, lacks merit. “The answer” to a decision banning mifepristone, Wyden declared, “is to ignore it, at least until there is a final ruling on the underlying matter by the Supreme Court.”

It’s a radical proposal, but not entirely without precedent. That Wyden is calling for it at all, however, is significant and suggests that at least a few Democrats may be open to extraordinary actions that could rein in rogue judges.

There are very rare examples of a presidential administration refusing to obey a federal court order (or, at least, preparing to) and Wyden discussed the most famous example in his speech. In the wake of the Supreme Court’s pro-slavery decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), President Abraham Lincoln denied that “the policy of the Government upon vital questions affecting the whole people” should be “irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court.” And then he openly defied the decision.

The Lincoln administration issued a passport to a Black man, despite Dred Scott’s holding that Black people cannot be citizens. And he signed legislation banning slavery in the territories, despite Dred Scott’s holding that an enslaved person remains enslaved even if they enter a free territory.

Realistically, the Biden administration is unlikely to follow Wyden’s advice. Though the argument that the executive branch might refuse to follow a rogue judge’s decision has a long pedigree — Alexander Hamilton wrote in the Federalist Papers that the judicial branch “will always be the least dangerous to the political rights of the Constitution,” in part because it “must ultimately depend upon the aid of the executive arm even for the efficacy of its judgments” — there’s a reason why Wyden had to reach back to the Lincoln administration to find a high-profile example of a president using this power.

Presidents have generally been reluctant to question the independence of the judiciary, which is normally an essential feature of a liberal democracy. And President Joe Biden, in particular, has largely brushed aside calls to reform the judiciary.

But the fact that Wyden, a senior Democrat with a reputation as a policy wonk and not as a bomb thrower, is calling for such an extraordinary response to a potential judicial decision is significant. It suggests that Democrats at the highest level are wrestling with what to do with the problem of rogue judges who act as rubber stamps for a partisan agenda, regardless of what the law actually says. And that they are open to solutions that ordinarily would not be on the table.

How we got to the point where a Democratic policy wonk is calling on the president to defy a court order

Matthew Kacsmaryk is a Trump appointee to a federal trial court in Texas. Before joining the bench, he worked as a lawyer for Christian Right causes, and his public writings reveal a fixation with sexual politics. During his brief time on the bench, he has attacked the right to birth control and tried to neutralize the federal ban on LGBTQ discrimination by health providers.

Now, he’s currently hearing a lawsuit, known as Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine v. FDA, which claims that the FDA must withdraw its approval of mifepristone — a drug the agency initially approved in 2000 and thus has been lawfully available in the United States for nearly a quarter century.

The plaintiffs’ legal arguments in this Alliance case are ridiculous. One of their primary arguments, for example, is that the FDA didn’t follow its own regulations when it approved mifepristone in 2000. But even if that were true, Congress enacted a law in 2007 that deemed any “drug that was approved before the effective date of this Act” to be in compliance with the relevant federal legal requirements.

And, in any event, there are countless procedural reasons why this lawsuit should fail. Among other things, the statute of limitations to challenge the FDA’s approval of a new drug is six years. Again, the FDA approved mifepristone in 2000.

But Kacsmaryk’s brief record as a judge includes several instances where he defied clear legal authorities to rule in favor of right-wing causes, and even did so in cases where he had no plausible argument that he had jurisdiction to hear the case at all.

There’s one other issue with Kacsmaryk. An obscure judicial order dealing with case assignments says that all federal lawsuits filed in Amarillo, Texas, will automatically be assigned to Kacsmaryk. The reason why Kacsmaryk hears so many cases brought by far-right litigants is that these litigants actively seek him out.

The Supreme Court, meanwhile, has largely encouraged this kind of behavior by conservative litigants, and by Kacsmaryk himself. Though the Supreme Court, which is dominated by Republican appointees, occasionally reverses judges like Kacsmaryk, the Court has slow-walked its review of such judges, often allowing someone like Kacsmaryk to dictate federal policy for months, a year, or more before stepping in.

So Wyden is proposing a radical solution to a devilish problem. Right now, far-right litigants can simply walk into Kacsmaryk’s courtroom and obtain any number of outrageous court orders sabotaging federal policies or access to drugs like mifepristone. And, even if the Supreme Court does eventually step in, it’s likely to do so only after letting Kacsmaryk sow chaos for months or longer.

Wyden’s proposal, to ignore Kacsmaryk’s ruling at least until the Supreme Court issues a final ruling, would neutralize the Supreme Court’s ability to leave Kacsmaryk’s order in effect while the justices wait months before they decide the case.

There are two important precedents for a president refusing to follow a court order

Explicit presidential defiance of the judiciary is rare, and for good reason. The courts are the mechanism the United States uses to ensure that the law is enforced against individuals who violate it. Respect for the law as a whole deteriorates if losing litigants believe that they can effectively appeal any lost case to a partisan president.

But there are two very high-profile examples in which a president did move against the courts — or, at least, in which a president was prepared to move against the courts — in response to utterly catastrophic decisions.

President Lincoln made his intention to defy Dred Scott clear from the very beginning of his presidency, announcing in his first inaugural address that the Supreme Court must not have the last word on slavery:

[I]f the policy of the Government upon vital questions affecting the whole people is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court, the instant they are made in ordinary litigation between parties in personal actions the people will have ceased to be their own rulers, having to that extent practically resigned their Government into the hands of that eminent tribunal.

He followed up this speech, of course, by signing legislation that was at odds with Dred Scott.

A similar drama played out during the Franklin Roosevelt administration, albeit with a less dramatic climax. In Roosevelt’s first term, many contracts contained “gold clauses” requiring debtors to pay their debts in gold dollars valued at the time the contract was made. Because of rampant deflation during the Great Depression, these gold clauses increased the amount of debt owed under these contracts by as much as 69 percent.

This was obviously a crushing economic burden for borrowers of all kinds, including homeowners. Additionally, these gold clauses drove up the amount of debt railroads owed on their bonds so much that they could have bankrupted most of the railroad industry, potentially shutting down the nation’s ability to ship goods at the height of an economic depression.

Faced with these consequences, Congress declared these gold clauses null and void — effectively establishing that borrowers would owe one dollar for every dollar they borrowed (plus interest, of course), and not $1.69 for every borrowed dollar. Roosevelt, afraid that the Supreme Court would strike down this legislation and reinstate the gold clauses, prepared a speech announcing that he would not obey such a decision.

Ultimately, the Court did not require these gold clauses to be enforced. But Roosevelt was prepared to say that “to stand idly by and to permit the decision of the Supreme Court to be carried through to its logical, inescapable conclusion would so imperil the economic and political security of this nation that the legislative and executive officers of the Government must look beyond the narrow letter of contractual obligations.”

There are much less radical solutions to the Matthew Kacsmaryk problem than the one Wyden proposed

Now, let’s be clear, the power that Lincoln exercised in response to Dred Scott, and the power that Roosevelt would have exercised if the Supreme Court had ruled the wrong way in the gold clause cases, is extraordinary and should only be exercised in response to truly outrageous court decisions.

President Andrew Jackson probably didn’t actually utter the words “[Chief Justice] John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it,” in response to an 1832 Supreme Court decision requiring states to honor treaties between the federal government and American Indian tribes. But he is often misquoted as a reminder that the power to defy court decisions can be used for evil ends as easily as it can be used to ward off catastrophe.

Similarly, it’s not hard to imagine what a figure like Donald Trump or Ron DeSantis might do if they believed they have a free hand to ignore the courts.

There are much less radical solutions to America’s Matthew Kacsmaryk problem than open presidential defiance of the courts, assuming that the institutions that have the power to implement those solutions actually want to prevent right-wing litigants from shopping their most ambitious cases to an allied judge.

The reason why every case filed in Amarillo is heard by Kacsmaryk, for example, is a September 14, 2022, order signed by Judge David Godbey, the chief judge of the federal trial court where Kacsmaryk sits, which assigns these cases to Kacsmaryk. Godbey could rescind this order, and replace it with a new order randomly assigning these cases to one of several judges.

The federal judiciary as a whole could also amend its civil procedure rules to provide that all cases will be randomly assigned. Or it could create a new process that, for example, permits the United States to request random assignment of any case that seeks to enjoin a federal policy on a nationwide basis.

Congress could also step in and write a new law governing case assignments. Or it could strip Kacsmaryk’s court of its power to issue nationwide injunctions.

These would be ordinary, measured solutions to the problem of a single rogue judge currently using his power to decide whether doctors can prescribe a widely used drug that has been available in the United States for more than 20 years. And then, in the future, possibly using it to decide any other issue that far-right litigants want him to decide.

But, if neither Congress nor the judiciary is willing to come up with an ordinary solution to the Matthew Kacsmaryk problem, then the only solutions that remain are extraordinary ones like the one proposed by Wyden.

READ MORE

Parts of a Norfolk Southern freight train that derailed in East Palestine, Ohio. (photo: Gene J. Puskar/AP)

Parts of a Norfolk Southern freight train that derailed in East Palestine, Ohio. (photo: Gene J. Puskar/AP)

Ohio to Open a Clinic Amid Growing Health Concerns Over Train Derailment

Chantal Da Silva, NBC News

Da Silva writes: "The Ohio Health Department is launching a clinic in East Palestine on Tuesday to address mounting health concerns among residents after a train derailment prompted Norfolk Southern officials to release and burn a toxic chemical in the area to avoid an explosion."

ALSO SEE: Many in East Palestine,

Skeptical of Official Tests, Seek Out Their Own

The clinic will open at noon Tuesday for any East Palestine-area residents with questions related to the Feb. 3 train derailment.

Ohe Ohio Health Department is launching a clinic in East Palestine on Tuesday to address mounting health concerns among residents after a train derailment prompted Norfolk Southern officials to release and burn a toxic chemical in the area to avoid an explosion.

The department said in a news release Sunday that it would open the clinic in partnership with the Columbiana County Health Department and with support from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

It said the clinic, which opens at noon, will be available to East Palestine-area residents “who have medical questions or concerns related to the recent train derailment.”

The state attorney general's office has indicated it plans to take legal action against Norfolk Southern after a 150-car train carrying hazardous chemicals derailed Feb. 3.

In a notice of intent to sue addressed to Alan Shaw, the president and CEO of Norfolk Southern, Ohio Attorney General Dave Yost said his office was considering litigation.

"After Norfolk Southern’s train derailed, the company caused the release of hazardous materials into the air, land, and surface and ground waters in and around East Palestine," Yost said in the letter, dated Feb. 15.

"The pollution, which continues to contaminate the area around East Palestine, created a nuisance, damage to natural resources and caused environmental harm. Local residents and Ohio’s waters have been damaged as a result," he said.

Yost also noted that Norfolk Southern was legally obligated to preserve “all information potentially relevant to the impending litigation.” He specifically noted that the records of all current and former employees of Norfolk Southern and its contractors pertaining to the derailment and pollution and the causes of the pollution must be preserved.

The rail company already faces multiple class-action suits from members of the East Palestine community over the incident, which forced residents within roughly a mile radius to evacuate their homes.

Some residents say they have suffered health issues, while others say they have found dead animals, including fish and chicken, in the area. For the most part, those suing the rail company say they that have lost income because of the evacuations, that they were exposed to cancer-causing chemicals and that they no longer feel safe in their homes.

The Environmental Protection Agency classifies vinyl chloride, the chemical that was released, as a carcinogen that can increase one’s risk of liver cancer or damage with routine exposure.

One of the class-action lawsuits alleges that the rail company “discharged more cancer causing Vinyl Chloride into the environment in the course of a week than all industrial emitters combined did in the course of a year” in the U.S.

Norfolk Southern has said it was “unable to comment directly on litigation.” In a public update Thursday, it said that in addition to continuing cleanup work, it was distributing more than $2 million in financial assistance to families and businesses to help with the costs of the evacuation. It also said it was creating a $1 million fund for the community. The company did not immediately respond to a request for further comment Monday.

In an open letter, Shaw promised to stay in the area “as long as it takes to ensure your safety and to help East Palestine recover and thrive.”

As of Sunday, the EPA had evaluated the indoor air in more than 530 homes in conjunction with Norfolk Southern and had not detected vinyl chloride above levels of concern in any of them. Meanwhile, Gov. Mike DeWine said Thursday that the municipal water was safe to drink, based on the results of sampling and tests done by the EPA, Norfolk Southern and other agencies.

In an apparent bid to demonstrate the water was safe to drink, the state EPA shared a photo on Twitter of agency officials and politicians, including East Palestine Mayor Trent Conaway, "enjoying a glass of clean water."

It said they were "happy to see good data results that show the water in the village is safe to drink."

Still, as concerns grow, Tuesday's clinic will allow residents to get health assessments and have their concerns addressed.

“Last week, I was in East Palestine and listened as many area residents expressed their concerns and fears,” state Health Director Bruce Vanderhoff said in a statement provided by the department. “I heard you, the state heard you, and now the Ohio Department of Health and many of our partner agencies are providing this clinic, where people can come and discuss these vital issues with medical providers.”

The clinic will be at First Church of Christ at 20 W. Martin St. Registered nurses and mental health specialists are expected to be on site. A toxicologist will be either at the clinic or available by phone, the Health Department said in a news release. A mobile unit operated by the Community Action Agency of Columbiana County will also be parked outside the church to accommodate more appointments, it said.

Community members can start scheduling appointments Monday by calling 234-564-7755 or 234-564-7888, the Health Department said.

In a recent letter addressed to Shaw, Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg said Norfolk Southern would need to uphold its stated commitments to those affected by the derailment.

“The people of East Palestine cannot be forgotten, nor can their pain be simply considered the cost of doing business," he said.

READ MORE

Rescue workers last week in Islahiye, Turkey. (photo: Mehmet Kacmaz/Getty)

Rescue workers last week in Islahiye, Turkey. (photo: Mehmet Kacmaz/Getty)

We Were Too Late, and the Rubble Was Quiet

Naomi Cohen, The New York Times

Cohen writes: "We were late to the scene of the crime. Two days late."

We were late to the scene of the crime.

Two days late. When the first earthquakes hit southern Turkey on Feb. 6, it took one full day of planning and one full day of travel before we reached the epicenter, Gaziantep. The flight from Istanbul usually takes about 90 minutes, but there was a rush of people heading south to help, and our group — about 160 search and rescue volunteers — had to wait our turn.

When we finally reached Islahiye, a town in Gaziantep Province, a man with dust-encrusted hair asked the gendarme why, four days after the earthquake that had caused the Sehit Zafer Yilmaz apartment building to collapse on his family and 19 others, we were finally listening for sounds of life in the rubble. He had told the same gendarme that he heard sounds on the first day and the second and the third but had been told there was nothing there. “There are 6,000 other districts like yours,” the gendarme said. There were many other districts, and many other buildings. In Islahiye alone there were at least 140 other buildings like the Sehit Zafer Yilmaz apartments; in the week that we were there we were assigned eight of them.

During the pandemic, I joined an organization that trains volunteers for neighborhood search and rescue teams so that each neighborhood has people who know what to do in the first crucial hours. An organization born out of the shared belief that when the next earthquake struck, we’d have only one another to rely on, and here we were.

When an earthquake hits at night, the usual approach is to try to reach the bedrooms first, but the Sehit Zafer Yilmaz apartments folded like a book: An upstairs bathroom spilled into a downstairs balcony, and a kitchen floor dangled above our heads. So we began to dig at random. We were a loud mess of gendarmerie, miners, construction workers, police, municipal workers, local volunteers and searchers and rescuers, with our jackhammers, hydraulic cutters, shovels, grinder machines, excavator and crane, each of us answering to a different team leader, all of us balancing on a precarious mound of twisted metal and concrete that could tumble at the next aftershock.

In Turkish the place we were excavating was, in rescue-speak, the olay yeri, which also means “the scene of the crime.” I found the term appropriate. The first victims we found there were a man and his baby daughter. The toes of his bare blue feet pointed up, and his daughter’s leg was curled around his. Where his waist had been was a block of concrete. It was too risky to reach them, so we had to leave them where they were and move on to the apartment of a woman and her daughter. We found them clutching each other. The woman’s husband, a policeman who had been helping on the site, wept silently as we rushed to cover them with blankets before zipping them into two black body bags.

We used a detector that can pick up the gentlest vibrations, like the shuffling of feet. On the fourth day we called out for anyone who was trapped to tap three times on the nearest object, and I saw the red bars on the monitor sigh up and down, suggesting a response.

The policeman near me was unimpressed. Twice already he had dug up a corpse where a noise had been detected. But, he said, we should search for everybody, dead or alive, with the same enthusiasm. The next morning our team pulled out a toddler from roughly the spot the detector had marked. A paramedic said he probably died a few hours earlier.

On the sixth day a sniffer dog was brought to seek out any last warm breaths and found nothing.

At another of the buildings I was assigned to there were rumors that the contractor who’d built it had been murdered. Contractors are being talked about here as if they should shoulder the blame for all 40,000 deaths and counting. Certainly they played their part, cutting corners and bribing the auditors who are meant to check whether the buildings are up to code. But what about the man who, we were told, knocked down the supporting ground floor columns of an apartment building to make way for a supermarket? Or the concrete maker who still sells concrete mixed with sea sand and large rocks, despite all the regulations that forbid it? Or the nth mayor who forgot about the earthquake emergency plan spread on his desk and left for a coffee break? Or us, the would-be rescuers, who were two days late?

There were rumors that people in Islahiye threw stones at the district governor’s office, attacked aid workers and stole rescue equipment and supplies of food. I could not verify any of the claims. But so what if they did? They have been failed by everyone. They were made homeless, left to camp out day and night in temperatures as low as 23 degrees Fahrenheit, with their families shellshocked or half missing or both, waiting to learn if they would have to bury yet another of their own. So many of them are poor and have always been last in line for everything.

By now many of these families have split again. Some have traveled across Turkey to squeeze into the homes of relatives as they wait for the new apartments they’ve been promised. Some have been herded into camps and will wait there.

On Monday night, another powerful earthquake measuring 6.4 struck the region. Emergency workers have started looking for survivors under the newly collapsed buildings. This time, their hearts will be heavier, but at least the dust won’t yet have settled.

READ MORE

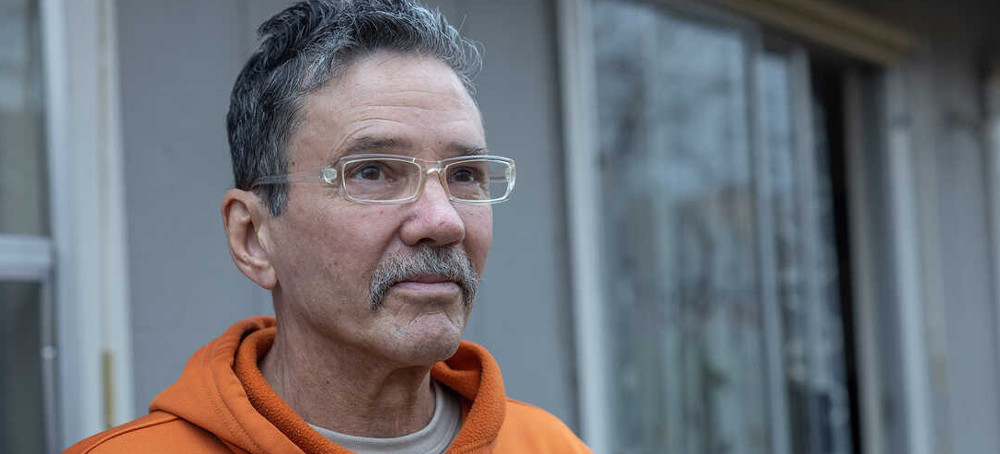

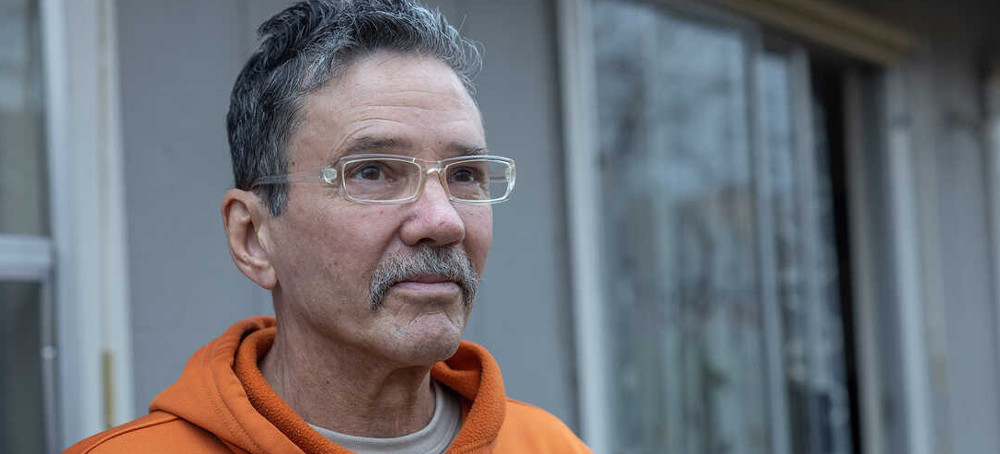

Jimmy Dee Stout outside his brother's home in Round Rock, Texas. Stout had served about half of his 15-year sentence for a drug conviction when he was diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer last year. (photo: Julia Robinson/KHN)

Jimmy Dee Stout outside his brother's home in Round Rock, Texas. Stout had served about half of his 15-year sentence for a drug conviction when he was diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer last year. (photo: Julia Robinson/KHN)

Frail People Are Left to Die in Prison as Judges Fail to Act on a Law to Free Them

Fred Clasen-Kelly, NPR

Clasen-Kelly writes: "'Prisons are becoming nursing homes,' Zunkel said. 'Who is incarceration serving at that point? Do we want a system that is humane?'"

Jimmy Dee Stout was serving time on drug charges when he got grim news early last year.

Doctors told Stout, now 62, the sharp pain and congestion in his chest were caused by stage 4 lung cancer, a terminal condition.

"I'm holding on, but I would like to die at home," he told the courts in a request last September for compassionate release after serving about half of his nearly 15-year sentence.

A federal compassionate release law allows imprisoned people to be freed early for "extraordinary and compelling reasons," like terminal illness or old age.

Stout worried, because COVID-19 had swept through prisons nationwide, and he feared catching it would speed his death. He was bedridden most days and used a wheelchair because he was unable to walk. But his request — to die surrounded by loved ones, including two daughters he raised as a single father — faced long odds.

More than four years ago, former President Donald Trump signed the First Step Act, a bipartisan bill meant to help free people in federal prisons who are terminally ill or aging and who pose little or no threat to public safety. Supporters predicted the law would save taxpayers money and reverse decades of tough-on-crime policies that drove incarceration rates in the U.S. to among the highest in the world.

But data from the U.S. Sentencing Commission shows judges rejected more than 80% of compassionate release requests filed from October 2019 through September 2022.

Why the law hasn't made a difference, so far

Judges made rulings without guidance from the sentencing commission, an independent agency that develops sentencing policies for the courts. The commission was delayed for more than three years because Congress did not confirm Trump's nominees and President Joe Biden's appointees were not confirmed until August.

As a result, academic researchers, attorneys, and advocates for prison reform said the law has been applied unevenly across the country.

Later this week, the federal sentencing commission is poised to hold an open meeting in Washington, D.C. to discuss the problem. They'll be reviewing newly proposed guidelines that include, among other things, a provision that would give consideration to people housed in a correctional facility who are at risk from an infectious disease or public health emergency.

The lag in compassionate release is particularly alarming because prisons are teeming with aging inmates who suffer from cancer, diabetes, and other conditions, academic researchers said. A 2021 notice from the Federal Register estimates the average cost of care per individual is about $35,000 per year.

COVID-19 made things even worse

The pandemic only compounded the problem, because incarcerated people with preexisting conditions are especially vulnerable to serious illness or death from COVID-19, said Erica Zunkel, a law professor at the University of Chicago who studies compassionate release.

"Prisons are becoming nursing homes," Zunkel said. "Who is incarceration serving at that point? Do we want a system that is humane?"

The First Step Act brought fresh attention to compassionate release, which had rarely been used in the decades after it was authorized by Congress in the 1980s.

The new law allowed people in prison to file motions for compassionate release directly with federal courts. Before, only the director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons could petition the court on behalf of a sick prisoner, which rarely happened.

This made federal lockups especially dangerous at the height of the pandemic, academic researchers and reform advocates said.

In a written statement, Bureau of Prisons spokesperson Benjamin O'Cone said the agency placed thousands of people in home confinement during the pandemic. "These actions removed vulnerable inmates from congregate settings where COVID-19 spreads easily and quickly and reduced crowding in BOP correctional facilities," O'Cone said.

The number of applications for compassionate release began soaring in March 2020, when the World Health Organization declared a pandemic emergency. Even as COVID devastated prisons, judges repeatedly denied most requests.

Research has shown that high rates of incarceration in the U.S. accelerated the spread of COVID infections. Nearly 2,500 people held in state and federal prisons died of COVID-19 from March 2020 through February 2021, according to an August report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Charles Breyer, the former acting chair of the sentencing commission, has acknowledged that compassionate releases have been granted inconsistently.

Data suggests decisions in federal courts varied widely by geography. For example, the 2nd Circuit (Connecticut, New York, and Vermont) granted 27% of requests, compared with about 16% nationally. The 5th Circuit (Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas) approved about 10 %.

Judges in the 11th Circuit (Alabama, Florida, and Georgia) approved roughly 11% of requests. In one Alabama district, only six of 141 motions were granted — or about 4% — the sentencing commission data shows.

Judges in the 11th Circuit seem to define "extraordinary and compelling reasons" more conservatively than judges in other parts of the nation, said Amy Kimpel, a law professor at the University of Alabama.

"This made it more difficult for us to win," said Kimpel, who has represented incarcerated people through her role on the nonprofit Redemption Earned.

Sentencing commission officials did not make leaders available to answer questions about whether a lack of guidance from the panel kept sick and dying people behind bars.

The new sentencing commission chair, Carlton Reeves, said during a public hearing in October that setting new guidelines for compassionate release is a top priority.

Stout said he twice contracted COVID in prison before his January 2022 lung cancer diagnosis. Soon after doctors found his cancer, he was sent to the federal correctional complex in Butner, N.C.

According to a 2020 lawsuit, hundreds of people locked in the Butner prison were diagnosed with the virus and eight people died in the early months of the pandemic. An attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union, which filed the suit, called the prison "a death trap."

The idea of battling cancer in a prison with such high rates of COVID-19 troubled Stout, whose respiratory system was compromised. "My breathing was horrible," he said. "If I started to walk, it was like I ran a marathon."

Stout is the kind of person for whom compassionate release laws were created. The federal government has found prisons with the highest percentages of aging inmates spent five times as much on medical care as did those with the lowest.

Stout struggled with drug addiction in the '80s but said he turned his life around and opened a small business. Then, in 2013, following the death of his father, he drifted into drugs again, according to court records. He sold drugs to support his habit, which is what landed him in prison.

After learning about the possibility of compassionate release from another prisoner, Stout contacted Families Against Mandatory Minimums, an organization that advocates for criminal justice reforms and assists people who are incarcerated.

Then-Chief U.S. District Judge Orlando Garcia ordered a compassionate release for Stout in October.

As Christmas approached, Stout said he felt lucky to be home with family in Texas. He still wondered about what was happening to the people he met behind bars who won't get the same chance.

READ MORE

Inside the Teamsters' Preparations for a UPS Strike

Alex N. Press, Jacobin

Press writes: "This summer could see 350,000 UPS workers walk off the job, the United States' largest strike in the 21st century thus far. The Teamsters are getting ready. Here's a look at how."

This summer could see 350,000 UPS workers walk off the job, the United States’ largest strike in the 21st century thus far. The Teamsters are getting ready. Here’s a look at how.

On Super Bowl Sunday morning outside a union hall in Nassau County, New York, the Teamsters had run out of parking. The members of Teamsters Local 804 had gathered at the Local 282 building because their own headquarters, in Long Island City, wasn’t large enough for a general membership meeting. Local 804 represents roughly eight thousand United Parcel Service (UPS) workers in New York City, Westchester, and Long Island, making it one of the Teamsters’ largest UPS locals. As members kept arriving, proper spaces filled up, and workers left their cars wherever they could — a problem for the union’s neighbor, an ambulance company, whose vehicles were now having trouble navigating the shared parking lot. Upon hearing that their cars were blocking ambulances, the offending union members trudged back to the lot to move. When this many Teamsters are preparing for a strike, it can be tough to find a spot.

Inside the union hall, the Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil” blared over the speakers as some six hundred members waited for the meeting to begin. Local 804 president Vinnie Perrone, who began working at UPS nearly thirty years ago, said that he hadn’t seen a membership meeting this well attended since Ron Carey was reelected for a second term as president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT).

That was in 1996, and Carey ran as a critic of weaknesses in the UPS contract; he was backed by a coalition that included the Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU), a reform caucus founded in 1976 to push for greater rank-and-file democracy within the then-mob-infested union. Carey had started out as a UPS driver in Queens, and before becoming IBT president in 1992, he served as president of Local 804. In 1997, he led the 185,000 UPS Teamsters out on a nationwide strike that lasted fifteen days before the union declared victory. The United States has not seen a strike of that magnitude since.

That may soon change, which is what the Local 804 members were gathered on Long Island to discuss.

“UPS’s opening position is crystal clear: all the company wants after a year with $101 billion in revenue is more money off your backs,” said Perrone from the dais facing the members, flanked by his executive board and business agents.

The UPS contract is the largest private sector union contract in the United States, and UPS CEO Carol Tomé has said she doesn’t believe the company and the union are far apart as they prepare to negotiate a new five-year contract. Union members aren’t so sure. They are preparing for a strike.

Perrone, who is also an IBT trustee and its Eastern Region Package Director, laid out the numbers: heightened delivery demand during the pandemic has been good to UPS, which reported a record profit in 2022. Annual revenue is up 11 percent on average for each year of the pandemic. The company delivers more than twenty million packages a day in the United States, making it the second-largest ground courier after the United States Postal Service (USPS). An estimated 6 percent of the country’s gross domestic product moves through UPS; though they are sure to try, competitors like USPS, FedEx, and Amazon would likely be unable to fully pick up the slack.

Many of the Local 804 members were angry. UPS has been laying off and displacing them, cutting hours and splitting shifts. One worker accustomed to working a straight eight-hour day says that he is now being told to work for four hours in the morning and four at night, upending his ability to get a good night’s sleep, much less do anything else. Other UPS locals report the same problem.

To Perrone, it’s a scare tactic by UPS, one that has the potential to sow disunity among the union members at a critical time: if a worker has their hours cut while their coworker voluntarily works overtime, the former would surely come to resent the latter. The local’s president wants to keep the workers together, focused on who he says is responsible for their grievances: UPS.

“UPS is trying to piss everyone in this room off,” said Perrone. “Every year, they try to scare and intimidate us.”

Just before noon, after workers who had formed a long line behind a microphone in the center aisle finished voicing questions and comments, Perrone recited a definition that may become relevant should UPS workers from Local 804 and across the country walk off the job in August: “A scab takes the job of a striking worker. He has no allegiance to anything and is only concerned with himself.” With that, the meeting was adjourned.

High Stakes

There are now around 350,000 Teamsters at UPS, a mix of drivers and warehouse employees who work inside the buildings where packages are loaded and unloaded. The national master contract expires on July 31; negotiations for the new contract are set to begin on April 16. That makes for a shortened negotiation window compared to prior years, in which bargaining began well in advance of the contract’s expiration. Current Teamsters general president Sean O’Brien has vowed that if the union doesn’t have a tentative agreement by the end of July, workers will strike.

The union has several sticking points. Foremost are “22.4s,” named after the 2018 contract provision that created a tier of lower-paid full-time workers. That process was led by then IBT president James P. Hoffa, son of the man whose name is synonymous with the union. While the average annual pay for a UPS driver is $95,000 — making it the rare job that offers livable pay, a pension, and benefits without requiring a college degree — newer drivers who are slotted into the 22.4 category do the same work as more senior drivers, but for pay that can be as low as $20.50 an hour and without comparable control over their schedules. That creates higher turnover in those positions, another benefit to the company given the greater compensation that seniority brings. O’Brien has also pledged to lead his members out on strike if the company refuses to eliminate the tier.

Fewer than half of the Teamsters at UPS are drivers; the rest work inside UPS distribution facilities, and many of them are part-time. Some part-timers are paid as little as $15.50 — meager enough that in some parts of the country, the local minimum wage is higher. The Teamsters want to raise the starting wage above twenty dollars an hour.

Another disagreement concerns UPS’s recent incorporation of a fleet of personal-vehicle drivers (PVDs) during peak delivery season (roughly November to January). PVDs deliver packages in their own cars, constituting a nonunion gig workforce whose existence poses a threat to its unionized counterpart. The lack of air conditioning in full-time drivers’ vehicles and the company’s push for driver-facing cameras are also matters of contention. (UPS insists that it has begun updating the temperature regulation systems in its vehicles after one driver died and several more were hospitalized during a recent heat wave.) Forced overtime, including six-day workweeks (what workers refer to as the “six-day punch”), has been one of the major stories of the pandemic and is a key issue at UPS as well.

The past few years have seen increased energy in the US labor movement, even if it has not yet translated into greater union density. Starbucks and Amazon workers have grabbed headlines for their surprisingly successful union drives. A sea change is underway in the United Auto Workers (UAW), whose contracts at the Big Three automakers, covering 150,000 workers, expire on September 1. Other potential strikes are in the works, too: the Writers Guild of America’s contract expires May 1, and another contract, covering some seventy-five thousand health care workers at Kaiser Permanente, expires on September 30. A UPS strike this summer would have political effects beyond its immediate economic impact — it would be a national sign of workers going on the offensive, refusing a status quo that has seen them get poorer as the rich accumulate more wealth than ever before.

A Contract Forced Down Drivers’ Throats

Sean Orr was driving his UPS route in 2018 — the last time the Teamsters were negotiating a new contract — when news broke that Teamsters leadership would invoke an arcane article in the union’s constitution to force him and his fellow UPS employees to accept a contract that the majority had voted against.

The “two-thirds rule” allowed IBT officers to impose a contract after a majority of voting members voted no if less than a majority of members participated in the vote. While 54 percent of the votes on the national master contract had been against ratification, fewer than 50 percent of eligible UPS employees voted, allowing Hoffa to invoke the loophole. Workers were shocked; few had even been aware of the possibility of such an outcome. (I hadn’t been aware of it, either; writing in the Washington Post, I had argued against the contract, laying out why UPS would want it ratified. I failed to consider that Hoffa might want its ratification as much as the company.)

“I was talking to my shop steward on the day that Hoffa and Denis Taylor [Hoffa’s lead negotiator] said that even though UPS had said they had heard the members and would return to the table, the contract would be imposed as is anyway,” Orr told me. “We were driving our routes and totally stunned.”

Orr is a member of Local 705 in Chicago and a TDU cochair, but at the time, he lived in Wisconsin. As members prepared to vote on ratifying the tentative agreement, he joined a rank-and-file movement to vote no on the contract, believing that certain provisions were unacceptable — the 22.4s most of all. The vote no movement argued that accepting a lower-paid tier in the contract wasn’t just bad for those slotted into that new category; it was kryptonite for the union. Lesser pay for equal work breeds resentment, mistrust, and anger between members of the same union. Condemn newer members to a lower tier, they argued, and you all but ensure the spirit of solidarity that is at the heart of trade unionism will rot from within.

After Hoffa imposed the contract, Orr says he realized that Hoffa was “going to finally lose his next election. You don’t do that to hundreds of thousands of your own members and get to have a career after that.”

It wasn’t only Orr who viewed Hoffa’s imposition of the contract as a betrayal. Rather than being on the workers’ side, the IBT president had proved that his foremost commitment was collaborating with the employer to get a deal that strengthened UPS’s position in the market. Workers were furious.

In short order, members of TDU and other Teamsters outraged by the imposition began organizing to ensure such a debacle would never happen again. At the 2021 IBT convention, delegates voted to amend the constitution, removing the two-thirds rule. They made other changes, too, mandating that all contract bargaining committees must include rank-and-file members and voting to distribute strike benefits on day one rather than day eight, as had been the previous policy. The latter move reflected a growing openness to using the strike as a weapon to get a strong contract, whether at UPS or elsewhere.

Breaking With Hoffa, Burying the Hatchet With TDU

Sean O’Brien broke with Hoffa over the UPS contract. The longtime close ally of the IBT president had led Boston’s Local 25 since 2006 and was the national union’s chief negotiator against UPS. But in 2017, as the Teamsters readied themselves to negotiate their largest contract, O’Brien suggested that the national negotiating committee include Kentucky’s Local 89 president Fred Zuckerman. Zuckerman, whose local includes UPS’s massive Worldport air freight facility, had run against Hoffa in the previous IBT leadership election on the Teamsters United slate and nearly won. Hoffa took O’Brien’s suggestion as an attack. Soon, O’Brien was fired from his position and replaced with Taylor.

It didn’t take long for O’Brien to return the favor. Criticizing Hoffa’s approach to both Amazon — whose nonunion expansion in logistics work similar to UPS’s undermines the standards won by Teamsters members — and UPS, O’Brien announced that he would run against Hoffa or his chosen successor in the 2021 IBT leadership election as a part of the Teamsters United slate, with Zuckerman running as secretary-treasurer. TDU endorsed the duo.

O’Brien had long been an opponent of the reform caucus — indeed, in 2013 he was suspended from his union positions for threatening some TDU members during a local election that his opponents nonetheless won. But as O’Brien’s election slate came together, Matt Taibi, a member of TDU and one of those opponents, was on it. Despite past differences, the two sides would work together to defeat Hoffa’s candidates: Steve Vairma and Ron Herrera for the presidency and for secretary-treasurer, respectively.

During the campaign, O’Brien took a militant tone toward UPS, vowing to strike to remove the hated 22.4 tier. He has promised to win “the best contract ever negotiated at UPS,” and in a September 2021 debate with Vairma in Las Vegas, vowed to make the Teamsters “a more dynamic, more militant organization.” As for Amazon, he pledged to create an aggressive organizing program targeting the company. The two are connected: if the Teamsters want to organize Amazon — and they must if they want to protect the standards they’ve won at UPS — the ability to point to a strong UPS contract with no concessions would make for a convincing argument when speaking with Amazon workers.

When the ballots were counted, O’Brien won handily, with about two-thirds of the vote electing him as the head of the 1.3 million–member union. Now it was time to make good on his campaign promises.

When I first met O’Brien in the summer of 2022, the lifelong Bostonian was in a surprisingly good mood despite the Celtics’ NBA finals loss to the Golden State Warriors the previous night. When I asked him if he’d watched the defeat, he said he’d caught the game in his hotel room after speaking at a rally alongside Senator Bernie Sanders, Association of Flight Attendants–Communications Workers of America president Sara Nelson, and then-incoming Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) president Stacy Davis Gates. We were all in Chicago for the Labor Notes conference, a gathering of rank-and-file union members from across the country and world. Labor Notes works closely with TDU — they share a Detroit headquarters, and O’Brien’s presence at the conference is a testament to the alliance. The presence of President Hoffa at the conference, much less his speaking at the gathering’s plenary session, would have been unimaginable.

“I need TDU just as much as TDU needs me,” said O’Brien. In a sign of the coalition’s continuance, he has appointed TDU member Paul Trujillo as IBT education director; other TDU leaders now hold key roles in the union as well. O’Brien noted that while TDU had long agitated for the reforms won at the latest Teamsters convention, it took a broader movement — one that includes him and his supporters in the union — to win them. Zuckerman, too, had once been a Hoffa ally before becoming fed up with union givebacks to UPS. But when O’Brien broke with Hoffa, enough of the old guard came with him to move the votes needed to win.

“There’s no running from the fact that I was with Hoffa at one point in time,” said O’Brien. “But whether you choose to be affiliated with TDU or you’re considered a staunch socialist, how different are we? We have common goals and objectives.”

O’Brien is a fourth-generation Teamster. He was born in Charlestown, the neighborhood north of downtown Boston that is home to Local 25’s headquarters, and he is quick to point out that unlike his predecessor, he began his career as a rank-and-file Teamster. He learned about the union at the dinner table: growing up, every member of his family was a member of the union except his mother, who was a member of the Office and Professional Employees International Union.

O’Brien and I had met in his hotel lobby at 9:00 a.m., but the IBT president had been up since before sunrise. He’d gone to a picket line at Breakthru Beverages Group in Cicero, just outside the city, where more than one hundred Teamsters had been on strike for four days. When I asked how the excursion went, he grinned.

“We brought a little Boston style,” he said, by which he meant that they’d prevented scabs from crossing the line, keeping pickets tight outside of the two entrances to the building. “We made the cops earn their money today.” He had a good time walking the picket line. “That was fun. I’d rather do that stuff than sit on my fat ass in Washington.”

The outing is a sign of O’Brien’s professed commitment to greater engagement with rank-and-file members. He said that he visits worksites at least three days a week, noting that Hoffa was rarely if ever seen at a workplace or on a picket line, “except maybe at a meet and greet or cocktail hour.”

“We should be at the workplaces, talking to members and seeing what they’re going through every day,” said O’Brien. If he stays in touch with workers, the people who experience an employer’s unreasonable demands and exploitation on a daily basis, it can also help keep him from wavering when pressure mounts at the bargaining table.

Later that day, in a conference room at the Hyatt Regency O’Hare, O’Brien stood before TDU at a fundraiser, flanked by rank-and-file members and expressing a debt of gratitude.

“When we decided to take back our union, we knew that one group was very important to help do not only what was in the best interest of leadership, but of the rank-and file-membership,” said O’Brien. “I want to thank you for having the courage and conviction to believe in what we did. But our work is not done, our partnership with TDU is not done.”

At the plenary in the hotel’s ballroom, O’Brien sat on the dais alongside Sanders, the CTU’s Gates, Amazon Labor Union (ALU) president Chris Smalls, Starbucks worker Michelle Eisen, and John Deere striker Nolan Tabb. By way of introduction, Labor Notes staffer Al Bradbury reminded the thousands of assembled workers that O’Brien had pledged to strike UPS if that’s what’s needed to reverse the givebacks negotiated by the Teamsters’ prior leadership. The statement brought the crowd to its feet.

“We’re going to negotiate the best agreement at UPS with zero concessions, and we’re going to put that company on its knees if that’s what it takes,” said O’Brien from the stage, eliciting rapturous applause.

He offered CEOs his forecast for the coming years: “It’s gonna get bloody, it’s gonna get painful. So ice up, because when you take one of us on, you take all of us on. If you are corporate America and you want to take us on, put your helmet on and buckle your chinstrap, because it’s a full-contact sport.”

Warming Up for a Strike

A few dozen Local 804 members and a handful of their allies were standing around in a parking lot in Hempstead, Long Island. The local had voted down the 2018 UPS contract by 96 percent — the same percentage by which they voted for O’Brien over the Hoffa-backed slate — and now, they were preparing for a strike. Beginning with the Teamsters’ launch of a contract campaign in August 2022, when Local 804 held more than a dozen rallies outside UPS buildings, the local has looked to engage members so that should a strike come, those rank and filers will see themselves as the heart of the union.

That goal wasn’t necessarily obvious as the group, unmissable in their signature bomber jackets, waited for stragglers to arrive. They were officially gathered to canvass the neighborhood to gather support for State Senator Jessica Ramos’s “Raise the Wage” bill, which would bring the state’s minimum wage to $21.25 an hour by 2026 and index it to inflation. But canvassing is also an opportunity to build confidence among newer union members and create relationships across the persistent divides of UPS’s workforce — part-timer versus full-timer, inside worker versus driver, 22.4 versus veteran driver — so that in the event of a strike, members are unified.

Militant rhetoric from Teamsters leadership means nothing if it isn’t backed by a credible strike threat. If UPS doesn’t believe workers are willing to endure the risk and hardship a strike entails, the company will have little reason to concede to the union’s demands. Most of the public would become aware of the union’s demands only once a strike starts, but the process of pulling one off begins long before any picket lines form. Calling a 350,000-person strike, especially with a workforce as geographically dispersed as that of UPS, is a momentous undertaking. It can only happen by ensuring rank-and-file workers are committed fighters.

Ramos, who chairs the State Senate’s Labor Committee, was in Hempstead to canvass, too. As members grabbed clipboards, Antonio Rosario, a full-time Teamsters organizer, passed out union beanies in the brisk February chill. “This is what it takes to make a movement like this happen: all of us working together,” Rosario told the group. After practicing the canvassing script, the workers divided into pairs and dispersed to their assigned turf.

Alease Annan and Angela Brown were one such pair. Annan is relatively new to the union: a year and a half ago, she was hired by UPS as an “inside worker” at the Maspeth, Queens building. As an unloader, Annan stands in a trailer, putting packages on a conveyor belt. As a sorter, her work consists of looking at packages’ zip codes and figuring out where to put them. As a part-time night-shift employee, she punches in at 10:45 p.m. and never knows for sure when she’ll get cut: part-timers are only guaranteed three-and-a-half hours of work, but during peak season, they sometimes stay until 6:00 a.m.

Brown, who works out of UPS’s main New York City hub on Forty-Third Street and Eighth Avenue in Manhattan, has been at the company for twenty-nine years. Both she and Annan are members of Local 804’s newly formed women’s committee. Long-term priorities for the group include breastfeeding space and additional women’s bathrooms in the buildings. The committee became Annan’s gateway into more active union participation. As a part-timer, her pay isn’t much higher than the New York City minimum wage of fifteen dollars an hour, and in January, she spoke at the State House in Albany in support of Ramos’s bill.

The pair was assigned to canvass a residential block. Everyone with whom Annan and Brown spoke offered their support for Ramos’s bill — raising the minimum wage is not a hard sell to working-class New Yorkers. A few residents already had the phone number of their representative, State Senator Kevin Thomas, and didn’t mind calling to urge him to cosponsor the legislation. The pair’s canvassing sheet filled up with names and phone numbers.

At the first few houses, Annan and Brown read mechanically from the script, occasionally stumbling over their words. But they quickly grew comfortable going off script, drawing on their own knowledge of how hard it is to get by on a low wage in New York. By the end of the canvassing session, both women were relaxed, enthusiastic. When they spotted a man walking by across the street, Brown ran over, hoping to get one more name before they called it a day.

“Unloading a box is my small contribution to what it takes to get a package to your door, and everyone involved in that process deserves a living wage,” Annan told me. Born and raised in Brooklyn, she hopes to own a home one day, and while she has a full-time job on top of her position at UPS, higher wages would help.

“I’m all for it,” Brown told me when I asked the pair about the possible strike. “When it comes up, I tell coworkers that I’m union because if we work together, we break bread together, and we need to stand together.”

But she and Annan are concerned about whether part-timers will cross the picket line. Annan has been saving money to endure the strike because she is engaged with the union, but she recently spoke to another part-timer who had no idea that a strike might be in the cards. “I doubt she’s alone,” she told me and Brown.

Part-timers are in a more financially precarious position than their full-time counterparts, and if they haven’t been putting money away to ride out a work stoppage, the hardship might push them to scab. A strike doesn’t require 100 percent participation to be won, but the more workers who stay out, the better. Plus, there’s the matter of what happens to relationships between coworkers when some strike and some don’t. Annan and Brown are concerned about that, too.

As the sun began to set, the canvassers regrouped to report back on their time at the doors. One pair’s turf consisted almost entirely of union members — fellow Teamsters and some SEIU members — and few of the Local 804 members encountered resistance in their conversations (though one man told a pair of canvassers, “I’m a boss and I don’t want to pay my workers more money”). Rosario thanked the group for spending their Sunday looking out not only for themselves, but for all workers. He informed them of other legislative efforts backed by the local: socialist New York City councilmember Tiffany Cabán’s Secure Jobs Act, which would protect workers from unfair and arbitrary firings, and Senator Ramos and Assemblymember Latoya Joyner’s TEMP Act, which would require employers, including UPS, to protect workers in cases of extreme temperatures.

The group talked about how the next canvassing session for Ramos’s bill, scheduled to take place in a more conservative part of Long Island, might go. The state senator would attend that outing too.

“You Can Feel the Giant Awakening”

Rosario was twenty-two in 1997, when Carey led UPS workers out on strike. He had been at UPS since 1994 but had only just gotten interested in the union. During the second Teamsters meeting Rosario ever attended, at the Local 282 union hall in Nassau County, Carey made a bravura speech announcing that the union would strike.

“I remember him saying, ‘We’re gonna be out on those streets. We’re gonna be raising our voices. We’re gonna fight for everything we deserve. We’re gonna fight for what we’re worth,’” Rosario told me. “Everybody was going nuts.”

The strike’s slogan was “Part-Time America Won’t Work,” emphasizing UPS’s desire to split stable full-time jobs into part-time and combination jobs. The work stoppage cost the company an estimated $40 million per day. When it was over, the union had won raises and some ten thousand full-time jobs — Rosario’s own position was transformed into that of a full-time package-car driver. But it is that same push to undermine those jobs, building out a lower tier of drivers and increasing the use of gig workers, that might leave UPS workers with no choice but to hit the streets once again this year.

Rosario’s experiences on that picket line transformed him. He became a shop steward, the worker others go to for information and assistance in grieving or otherwise resolving workplace issues. Around ten years ago, Rosario joined TDU. Last year, after just under three decades at UPS, he became a full-time organizer for the IBT.

Shortly after the strike, Hoffa and his allies forced Carey out of the presidency on trumped-up charges of corruption, of which he was later cleared. Hoffa led the union for nearly twenty-five years. Rosario describes the Teamsters during that period as a sleeping giant, an era that he believes the union is leaving behind: “You can feel the giant awakening; you could already feel the morale improving among workers during the leadership election.”

When I asked him whether he thinks all of his fellow TDU members feel the same way — after all, O’Brien was a loyal Hoffa lieutenant for a long time — Rosario insisted that even the strongest skeptics he has spoken to feel good about the direction the union is going under O’Brien’s leadership. “The difference in the union is like night and day,” he told me. “It’s a beautiful thing to watch.”

A Credible Strike Threat

No one knows for sure whether the Teamsters will strike UPS this summer, though some observers have already gone on the record saying it’s a certainty. Todd Vachon, a professor of labor relations at Rutgers, told CNN that the only question is how long the strike will be. It’s hard to imagine a 350,000-person strike — and one that is not concentrated in just one state or region but covers the whole United States — in a country with union density and strike activity at historic lows. But the labor movement wasn’t particularly strong in 1997 either.

O’Brien campaigned on militancy toward UPS. Even if he wanted to, it would be hard for him to back down on striking in the face of a membership willing to fight — and winning any of the union’s contract priorities, much less all of them combined, requires a credible strike threat. UPS CEO Tomé has told investors that the company is “building contingency plans”; workers say that management has been warned not to plan any vacations for August.

It’s hard to overstate the transformative potential a successful nationwide UPS strike would present. Many workers in the United States have seen little evidence that taking collective action with their coworkers can improve their lives, and this would be a chance to change that. A strike of this magnitude would not only create more Rosarios at UPS, but it would also be a point of coherence for the many workers at other companies who want to organize their own workplaces. The question of winning a strong contract is hanging over workers who have recently organized new unions — the ALU, Starbucks Workers United — and that, too, raises the stakes of this fight. A picket line is a point of unity, a place where the still-disparate parts of the labor movement can come together, building relationships and clarity.

Yet the goal is a strong contract, and some UPS workers hope that the strike threat they are now creating will be sufficient to force UPS’s hand before the July 31 deadline. But there are bigger considerations, too: O’Brien built his political power on the message of striking UPS and members may demand he do just that.

At the moment, those workers are signing contract unity pledge cards, which list fourteen contract priorities including converting 22.4s into regular package-car drivers, addressing excessive overtime, raising part-time pay, and reining in subcontracting and PVDs. The hope is that when negotiations begin, O’Brien and Zuckerman will bargain with a towering pile of those cards on the table in front of them. The message to UPS of such a stack would be, “we aren’t bluffing.”

In the workers’ favor, too, is the place UPS drivers hold in the public eye. As Deepa Kumar writes in Outside the Box, her book on the 1997 UPS strike, the company had trouble vilifying the strikers because drivers are too sympathetic of figures. James Kelly, then CEO of UPS, even admitted, “If you were to pit a large corporation against a friendly, courteous UPS driver, I’d vote for the UPS driver, also.” Times may have changed, but many customers still know their drivers, and they’ve seen them work day in and day out through a yearslong pandemic. Plus, pro-union sentiment among the US public is at a fifty-year high.

Orr said that at the Jefferson Street UPS building where he works, his focus is on changing the idea that the union is only people like him, a shop steward. Workers need to know that they are the union, and that every UPS employee has the responsibility of enforcing the contract.

“A credible strike threat requires that the entire workforce is visibly, militantly fighting,” said Orr. That means enforcing the current contract to the letter, training members to know their rights, highlighting the ones that UPS is trying to whittle down, and holding weekly meetings at UPS buildings to keep members informed.

On August 1, 2022, a year before the contract’s expiration, Orr’s local handed out thousands of hats at the gates of all their UPS buildings. The front of the hat reads “Keeping the Workers’ Movement Alive,” and on the side is a graphic honoring the twenty-fifth anniversary of the 1997 strike. Orr said management hates the hats and threatened disciplinary action in his building if workers wouldn’t take them off. But when one regional manager told workers to do so, they refused, reciting the article in their contract that protects their right to wear union gear inside the building. “Creating that militant union presence on the shop floor is the best thing we can do right now,” he told me.

On the morning of the day we spoke by phone, Orr had been talking with a few veterans of the 1997 strike in his building. They told him they felt that the union was in a better place than it had been before the last strike.

“They feel really good,” he told me. “They’re confident that the union is going to have a big win against UPS.”

READ MORE

Wheat plantations burnt after Russian airstrikes in Donetsk oblast. (photo: Miguel Medina/AFP)

Wheat plantations burnt after Russian airstrikes in Donetsk oblast. (photo: Miguel Medina/AFP)

The 'Silent Victim': Ukraine Counts War's Cost for Nature

Jonathan Watts, Guardian UK

Watts writes: "Toxic smoke, contaminated rivers, poisoned soil, trees reduced to charred stumps, nature reserves pocked with craters: the environmental toll from Russia's war with Ukraine, which has been detailed in a new map, might once have been considered incalculable."

Investigations are under way in the hope this is the first conflict in which a full reckoning is made of environmental crimes

Toxic smoke, contaminated rivers, poisoned soil, trees reduced to charred stumps, nature reserves pocked with craters: the environmental toll from Russia’s war with Ukraine, which has been detailed in a new map, might once have been considered incalculable.

But extensive investigations by Ukrainian scientists, conservationists, bureaucrats and lawyers are now under way to ensure this is the first conflict in which a full reckoning is made of environmental crimes, so the aggressor can be held to account for a compensation claim that currently stands at more than $50bn (£42bn).

The environment ministry has set up a hotline for citizens to report cases of Russian “ecocide”, which so far number 2,303, and issues weekly updates of the tally. The latest edition estimates that in the past year:

- Ukraine has had to absorb or neutralise the impact of 320,104 explosive devices.

- Almost one-third of the country (174,000 sq km) remains potentially dangerous.

- Debris includes 230,000 tonnes of scrap metal from 3,000 destroyed Russian tanks and other military equipment.

- A hundred and sixty nature reserves, 16 wetlands and two biospheres are under threat of destruction.

- A “large” number of mines in the Black Sea threaten shipping and marine animals.

- Six hundred species of animals and 880 species of plants are under threat of extinction.

- A third of Ukrainian land is uncultivated or unavailable for agriculture.

- Up to 40% of arable land is not available for cultivation