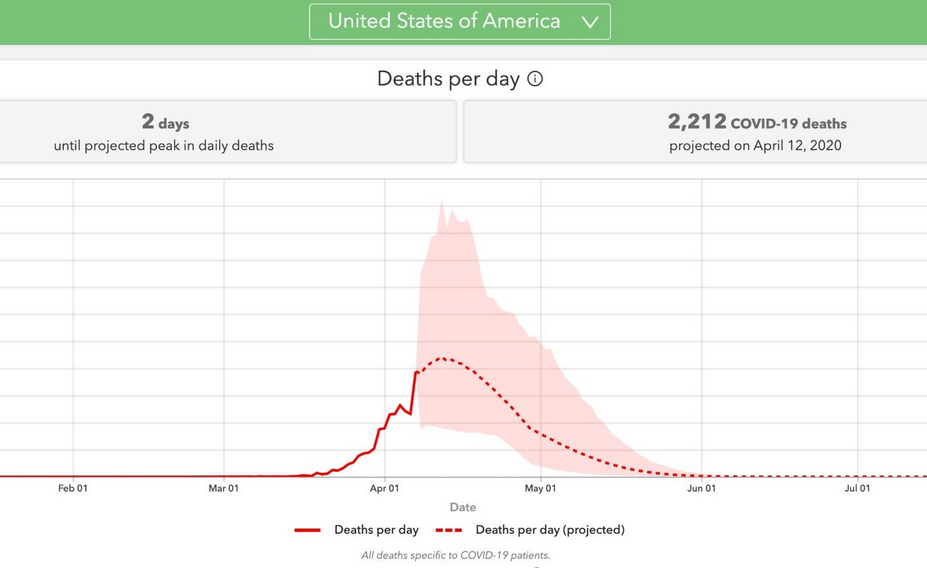

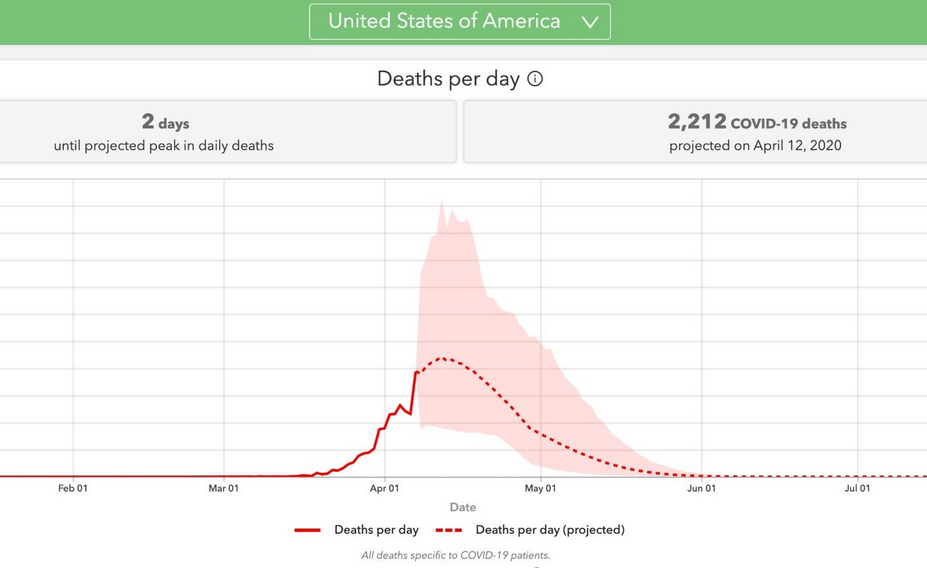

'There's a Perceived Need to Get This Over With So We Can Get Back to Work'Janine Jackson  Janine Jackson interviewed FAIR's Jim Naureckas about Covid-19 false choices for the May 1, 2020, episode of CounterSpin. This is a lightly edited transcript. MP3 Link Janine Jackson: There was a story in the April 29 New York Times about how, even as coronavirus cases in the US have surpassed 1 million, and more American people have died than in the Vietnam War, Donald Trump and Jared Kushner are pushing the line that the White House response is “a great success story” and “We're on the other side of the medical aspect of this.” It's the sort of elite media reporting that imagines it’s holding Trump and his cronies up to derision, with withering terms like “revisionist history” and “at odds with the reality on the ground.” “Mr. Trump has demonstrated a striking tendency to try to frame the political narrative on his own terms, even when at variance with the facts,” says the Times, as it provides a platform for him to do just that. There is some great data reporting, of course, but corporate media’s overweening focus on “competing narratives” or “spin” colors and clouds their own relationship to the facts. Dangerous at all times, it's especially reckless in a time of still-evolving public health crisis. Joining us again to talk about what we know about the reality on the ground of Covid-19 is Jim Naureckas, editor of FAIR.org. Welcome back to CounterSpin, Jim Naureckas. JN: Thanks for having me back.  This exceptional Washington Post piece (4/30/20) came out the day this interview was conducted, and directly addresses the question of how people are still getting infected despite the lockdown. JJ: I say, “to talk about what we know about the pandemic.” So much coverage seems to be reflected through a lens of what the speaker wants, or assumes: “Since the economy has to reopen soon, how do we do that?” You almost have to force yourself to pull back, and just look at actual information: Who is getting sick? Where? Who is dying? And so on. But I know that you've been concerned that reporters aren't being tenacious enough on what you might think would be Question 1 to stop a virus, the news we could most use: Namely, how are people catching it? JN: Yeah, I do think that is an incredibly important story that is not really being covered. The fight against the coronavirus involves, certainly, healthcare workers trying to cure the sick. But, really, the bigger terrain that this is being combated on is keeping people from getting infected. And we have to do that ourselves. No one is keeping us from being infected except our own actions. So we need to know, what works to keep us safe and what is putting us at risk? And I don't think that media are really giving us the information that we need to know what those risks are. JJ: Yeah, they're talking about cultural battles between people wearing masks and people not wearing masks, but it's sort of apart from a conversation of, “Do we have evidence that that works?” Because, of course, if you know how people are catching it, you'll also know how people maybe are not likely to catch it, and we can shape our actions around that. JN: And it does seem like the kind of thing that reporters can do, to talk to people who are sick—not all of whom are gravely ill—and ask them what they were doing, what their lifestyle choices were under the lockdown. I have seen some good reporting on case studies that have been done, mostly before the lockdown, that show that there can be a great number of cases spread from a single social event, where people are in a room together and give the coronavirus to each other. But I have not seen that kind of reporting done, to talk about where the new infections keep coming from, now that most people are sheltering in place. JJ: The way that media refer to something in what we call the “boilerplate,” the sort of thumbnail description they give of an event or a phenomenon—it might be inserted into lots of different stories—but it reflects their essential message about this situation. And with that in mind, I know that you took issue with the way AP, a very influential wire service, was describing the coronavirus. What was the problem there, and has it changed? JN: They seem to be using the same boilerplate. There's this paragraph they stick into just about every article that they write about the coronavirus. And it seems to reflect a fear that people are too worried about the coronavirus. It stresses that this is mostly a problem for people who are old or have health problems, and concludes, “The vast majority of people recover.” The vast majority of people recover from cholera, you know; it doesn't mean it's not a deadly disease. I think that this is really sending a message, especially to young people, that this is not something that you need to take seriously. It's not something that is going to affect you, so why worry about it? JJ: Yeah. And they talk about, “Well, it's just with people who have underlying health conditions.” But then when you parse that out, that turns out to be a large, very large number of people. JN: Yeah, a huge number of people are considered overweight, have high blood pressure and may not be aware of it. It works out to be about half the population have the kind of underlying health issues that they say are dangerous.  The Hill (4/10/20) projecting the US Covid-19 outbreak will end by August 4 with a total of 60,415 Covid-19 deaths; the US passed that number on April 29. JJ: In this Times story that I saw yesterday, Jared Kushner says, “We're on the other side of the medical aspect of this, and I think that we've achieved all the different milestones that are needed.” You know, he's a humanoid, and the piece is trying to make clear that these claims are “out of step with reality,” but media themselves have talked about a “peak,” and us being on the other side, having turned some kind of corner, or other countries having done that, and they do it with what looks like data and charts and everything. What's troubling you there? JN: There is this, I think, very comforting idea that as quickly as the coronavirus arrived, it will go away. There are these charts that have been widely circulated, from an outfit at the University of Washington, that show very neat peaks, where the infections go up, and then they come right back down again. And when you look at the math behind these forecasts, you find that the assumptions that they use require that the disease go away as fast as it arrived. And in fact, when they correct their data for a steeper increase in infections, they have to correct on the other side, and have the disease going away just as fast. When you look at the real world, and you look at the course of infections in countries that have had the coronavirus for longer, you do not see a sharp peak with the infections coming down. The coronavirus outbreaks can linger for a long time, with a long period of ongoing death at relatively the same rate. And that seems to be a more realistic view of what the endgame is going to be here. JJ: Everyone, of course, wants to see hopeful news. And there is hopeful news out there. We just want it to be based in reality, and not in sort of magical thinking. But you took issue with a New York Times piece the other day out of Rhode Island. What’s that about? JN: Well, the point of the article was that Rhode Island has done a lot of testing. And it was really trying to assert that Rhode Island only looks like it has a bad outbreak of coronavirus because they test so much, and so they're more aware of it. But really, when you look at deaths from coronavirus, which are not subject to bias from doing a lot of testing, they have the seventh-worst case in the nation. They really have been hard hit. And while they have, to their credit, ramped up testing, they did that like two weeks ago. Since they've been at this high level of testing, they continue to have new cases rising, and that's not because they’re testing a lot, it’s because they actually have an ongoing infection that is serious. And the article was framed as: The fact that they're testing so much will make it easier for them to reopen their economy. And I think that is underlying a lot of this wishful reporting, is that there's a perceived need to get this over with, so we can get back to work. And so you look for whatever hopeful signs you can point to, that say that it's OK to go back to having economic activity, even though the virus is still out there. And in most places, where they're talking about reopening, there's far more cases now than there were when the economy was shut down in the first place. JJ: Yeah. Which makes it hard to follow. But let me just ask you, I know you just wrote something about Sweden, which is another place folks first thought was a good model, then thought, hmm, that wasn't such a good model. What’s that about, now? JN: Yes. The New York Times, again, had a story talking about the “apparent success” in Sweden where they have not had a lockdown, and tried to get by with social distancing and banning gatherings over 50 people, but have not told people to stay home. And a lot of people point to Sweden and say, “Ah see, look: Sweden.” JJ: They’re being more sane about it.... JN: And they're doing a great job. And the New York Times claimed that they have been as successful as most countries in the world at controlling the virus. And it's just not true. Per capita, in terms of deaths, they have the tenth-worst outbreak in the world. That's not a success. They have roughly a third, per capita, more deaths than the United States. And I don't think many people would say that the United States is a role model for dealing with the coronavirus. But Sweden has done worse. When you compare it to their neighbors, who are similar countries in terms of their social structure and population density, which I think is an important factor here, Norway and Finland have had one-sixth the number of deaths per capita as Sweden. So it's not clear to me why we're not writing stories about Finland's apparent success of dealing with the coronavirus, rather than looking at Sweden.  Jim Naureckas: "A lot of coverage...assumes that the two choices are to sit in our homes and have people basically go bankrupt as they can't work, or else to force them back into the workplace and have them take their chances with the coronavirus." JJ: Again, it's hard not to see what's pointed to as a solution being shaped so much by what people want to see as the solution, and want to happen. Finally, you understand that people don't think we can just stay in lockdown, and just wait, and just wait for a vaccine, and maybe that'll be a year or maybe that'll be two years. But it makes it sound as though that's all we can do. What do you think about that framing as we go forward, in terms of, we've exhausted our options, and now we just sit and wait? JN: You do see a lot of coverage that assumes that the two choices are to sit in our homes and have people basically go bankrupt as they can't work, or else to force them back into the workplace and have them take their chances with the coronavirus. And the idea that you could support people through this crisis, give people the resources they need, delay obligations like rent and debt repayment and so forth, that these things could be put off while we deal with the crisis—it’s not really being seriously considered as an option. The idea that the landlord must get paid seems to be a sacred cow that really can't be trifled with. JJ: We've been speaking with Jim Naureckas. He's the editor of FAIR.org. Thanks, Jim Naureckas, for joining us this week on CounterSpin. JN: Thanks for having me back. |