Friends,

Another thing we must do to resurrect the common good is to use honor and shame appropriately.

All too often, America honors people who haven’t advanced the common good but have merely achieved notoriety or celebrity or amassed great wealth or power.

All too often, America shames people for failing to conform to prevailing ideas about fashion or coolness.

If we’re to revive the common good, we must honor behavior that strengthens the common good and condemn behavior that erodes the common good.

IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICA, THE MEANING OF HONOR has become confused, because those who bestow honors often have ulterior motives.

Funding has been drying up for universities, hospitals, museums, social services, the arts, libraries, and other repositories of public goods. Meanwhile, vast riches have been accumulating in the hands of a relative few.

As a result of both trends, organizations have been using the lure of honors to hook rich donors. In return for their donations, they are imbued with moral approval. Galas are held in their honor. Colleges bestow on them honorary degrees. Endowed professorships carry their names. Their names are etched on university buildings, concert halls, research institutes, and museums.

But how these donors obtained their wealth is assumed to be irrelevant. The message is that the common good doesn’t really count. Wealth and power do.

[Michael Milken receiving honorary degree from Drexel University, 2008]

Michael Milken was indicted in 1989 for racketeering and securities fraud. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison (subsequently reduced to two), a fine of $600 million, and a permanent ban from the securities industry.

Since then, Milken has been repeatedly honored by universities for his charitable giving.

The Taubman Center at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government is named after Alfred Taubman, who in 1988 donated $15 million to establish it. In 2002, Taubman was sentenced to prison for orchestrating a price-fixing scheme between the nation’s top two auction houses.

After the conviction, Harvard students asked Harvard officials to change the name of the center. They refused. The center’s director explained that, “in the great scheme of things, [Taubman] has led a very ethical life. His conviction does not mean that his life has not been ethical, or one that Harvard doesn’t want to associate with.”

Hello? Taubman had just been convicted of price-fixing. His name was etched on Harvard’s school of government, which is supposed to train students to work for the common good. A criminal conviction for price-fixing did not alter the appropriateness of honoring this man?

In 2017, the Los Angeles Press Club bestowed on movie mogul Harvey Weinstein its Truthteller Award. The organization called him an example of “integrity and social responsibility.”

But it was an open secret that Weinstein had a long history of harassing women in five-star hotel rooms. Why did Hollywood honor Weinstein despite this? Because he raised money for many activities Hollywood approved of, and he had the power to make or break the careers of starlets, writers, journalists, and public relations specialists who directly or indirectly depended on him.

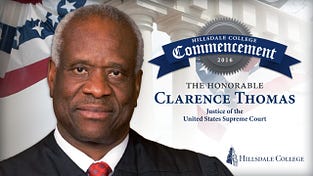

We automatically affix the prefix “The Honorable” to the names of people who hold high public office, including Supreme Court justices who have dishonored their offices by taking lavish and unreported gifts.

Honors should be reserved for those who have shown the courage to stand up for the common good against the forces of greed, corruption, and abuses of power.

I’m thinking of people like Cheryl Eckard, who, in 2003, as a quality assurance manager at pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline, discovered serious problems at its largest plant — drugs produced in non-sterile environments, a water system contaminated with microorganisms, and medicines made in the wrong doses. After Eckard alerted management, she was fired. She then shared her findings with the Food and Drug Administration and sued the company.

And Army Major General Antonio Taguba, who insisted on an honest investigation into Abu Ghraib even though his military and political superiors didn’t want one.

[Eileen Foster]

And Eileen Foster, who in 2008, while in charge of fraud investigations at Countrywide Financial Corporation (the nation’s largest subprime mortgage lender, at the epicenter of the mortgage meltdown that almost brought the entire economy to its knees), told her superiors that many executives in Countrywide’s chain of command were working to cover up the massive fraud. A few months later, Countrywide’s new owner, Bank of America, fired her for “unprofessional conduct.” Foster then began a three-year fight to clear her name and prove she and other employees had been punished for doing the right thing.

Let me add to this honor roll people who put themselves in harm’s way for the good of all: first responders, volunteers in natural disasters, firefighters, members of the armed forces.

And the federal and state prosecutors who are trying to hold Trump and his enablers accountable to the law in the face of Trump’s intimidation and harassment, often accompanied by threats by Trump loyalists to them and their families.

We should honor those who do among the most difficult of jobs of all — teachers in poor communities, social workers, nurses, elder-care and hospice workers.

These are the true heroes of America. They keep the nation going. They maintain the common good. But they’re often overlooked, sometimes even insulted. Most earn very little.

We can honor not just with respect and appreciation but also by making sure they earn enough money to live. We can also honor them by raising public awareness of the importance of the work they do.

WE HAVE ACADEMY AWARDS for actors, directors, and screenwriters; Nobel Prizes in math and science; culinary awards for chefs; Olympic awards for athletes; Kennedy Center honors for the performing arts.

Why not awards for upholding and strengthening the common good?

A Common Good Award for an outstanding whistleblower.

A Common Good Award for an exemplary civil servant.

A Common Good Award for the teacher or social worker whose quiet and modest work over the course of her career has dramatically improved other peoples’ lives.

A Common Good Award for the nonprofit leader who has taken a courageous stand speaking truth to power.

Why shouldn’t universities confer honorary degrees on these unsung heroes of American life?

Why doesn’t the United States, as does Britain, issue honors to a thousand citizens each year who have made significant contributions to the common good?

Such honors would continuously remind us of what it means to work for the common good, offer examples of civic behavior we want to encourage, and raise public consciousness of what we owe each other as members of the same society.

Such public honoring could be a corrective to what we now do — blindly and automatically bestow honors on rich philanthropists because they’re rich, and celebrities because they’re celebrated.

WIELDED APPROPRIATELY, SHAME can also be a powerful motivator for the common good. It can illuminate the gap between the ideals we profess and the reality we tolerate, mobilizing us into action.

Martin Luther King Jr. shamed the nation by making it impossible for white Americans outside the South to condemn segregation there while simultaneously tolerating discrimination all around them. As King told a crowd of 25,000 in Detroit in June 1963:

“We’ve got to come to see that the problem of racial injustice is a national problem. No community in this country can boast of clean hands in the area of brotherhood. Now in the North it’s different in that it doesn’t have the legal sanction that it has in the South. But … de facto segregation in the North is just as injurious as the actual segregation in the South. And so if you want to help us in Alabama and Mississippi and over the South, do all that you can to get rid of the problem here.”

By extending the shame of Southern segregation to the nation as a whole, King raised the bar: We were all implicated in racial discrimination. It was our shame as well as the South’s. It continues to be.

A more recent example of shaming for violating the common good occurred in August 2017 after Donald Trump equated neo-Nazis who marched on Charlottesville, Virginia, with counter-demonstrators.

In response, Kenneth Frazier, the CEO of Merck pharmaceuticals, resigned from Trump’s business advisory council. Frazier said:

“America’s leaders must honor our fundamental values by clearly rejecting expressions of hatred, bigotry, and group supremacy, which run counter to the American ideal that all people are created equal. As CEO of Merck and as a matter of personal conscience, I feel a responsibility to take a stand against intolerance and extremism.”

Frazier’s words and action fortified other CEOs to resign from Trump’s advisory boards. Although Trump himself has shown no capacity for shame, their action had large symbolic importance. They signified that the corporate leaders of America were not going to abide white supremacists. They were going to take a stand for the ideal of racial equality.

SHAME MAY HAVE EVOLVED as a way to maintain social trust necessary to help us survive. Charles Darwin, in his book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, noted that humans around the world express shame in similar ways — blushing, becoming hot, casting their eyes downward, and lowering their heads.

Members of Congress occasionally call as witnesses CEOs who have harmed the common good, but these shaming rituals rarely have any practical consequences.

After BP’s carelessness on the North Slope damaged the environment, Representative Joe Barton, a Texas Republican and chairman of the Committee on Energy and Commerce, excoriated BP executives. Barton said he was

… concerned about BP’s corporate culture of seeming indifference to safety and environmental issues. And this comes from a company that prides itself in their ads on protecting the environment. Shame, shame, shame.”

But no legislation was passed to force BP or any other oil company to be more careful. Four years later, BP spilled 210 million gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico from its Deepwater Horizon drilling rig — the worst oil spill in history.

Congressional shaming must be followed by legislation and criminal prosecutions that confirm the standard of behavior we expect.

PROSECUTIONS SHOULD BE DIRECTED against individual wrongdoers rather than at companies as a whole. Corporations cannot feel shame; only individuals can.

Yet these days, few executives of major corporations and Wall Street banks are ever held personally accountable for illegal acts. As I’ve noted, no executive of any major bank was prosecuted for the 2008 financial crisis.

Obama’s Justice Department stopped bringing cases against corporate executives, because winning cases against individual executives has become too difficult and expensive for government prosecutors.

Corporations have become adept at giving their top guns plausible deniability of knowledge in any nefarious scheme (Goldman Sachs executives used the abbreviation LDL — “let’s discuss live” — to hide their traces), and prosecutors are routinely outgunned and outmaneuvered by platoons of high-priced corporate attorneys.

But individual executives must be held accountable.

AMERICA HAS BECOME CONFUSED about the difference between private morality and public morality.

Private morality concerns what people do in private, often involving sex — between unmarried people or gay people, adultery, contraception, abortion, gay marriage, even which bathroom a transgender person must use.

Public morality involves what people do when they hold positions of power and public trust.

A society that honors and elevates the common good would not penalize average people for what they do in private, but would be vigilant against leaders who abuse and undermine public trust.

Ideally, notions of right and wrong are sufficiently embedded in people’s moral consciousness from an early age that they don’t need to be honored or shamed into good behavior.

But the erosion of the common good over the last decades suggests that such moral consciousness has waned. Society must buttress it, and in so doing remind others of acceptable limits.

If we’re serious about reestablishing the moral foundation of our life together, we must reconnect honor and shame to the good we hold in common.

***

Next week, I’ll talk about civic education as part of our effort to rediscover the common good. Thanks again for joining me on this journey.

These weekly essays are based on chapters from my book THE COMMON GOOD, in which I apply the framework of the book to recent events and to the upcoming election. (Should you wish to read the book, here’s a link.)