24 May 23

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

WE WILL NOT BACK DOWN — Now more than ever we are faced with enormous challenges. These are the times that bring out the best in the best of us. We will stand as strong now as we ever have. We proudly ask for your support.

Marc Ash • Founder, Reader Supported News

Sure, I'll make a donation!

Graeme Wood | Inside the Garden of Evil

Graeme Wood, The Atlantic

Wood writes: "Harlan Crow wants to stop talking about Clarence Thomas."

Harlan Crow wants to stop talking about Clarence Thomas.

When you collect statues of lenin, Harlan Crow told me, “you get to be a bit of a snob.” The first Lenin I had seen that morning was a brass likeness in the entryway to Crow’s Dallas mansion—a house that capitalism built, if ever there was one. Lenin was in his Finland Station pose, but with his head replaced by Mickey Mouse’s. Crow’s office had at least one more Lenin. Now we were outside, pelted by rain in Crow’s Garden of Evil, admiring the fourth in a series of Lenins, an 18-footer harvested from western Ukraine. “There’s so many statues of Lenin,” Crow said, educating me on dictator-statue appreciation the way another rich guy might introduce a friend to the world of fine wine. Having a good story was crucial. “You don’t want a Lenin From Factory 107. You want Politburo.”

The many Lenins joined dozens of other petrified tyrants and world leaders, among them Communist revolutionaries (Ho Chi Minh, Mao Zedong, Che Guevara), a few secular autocrats (Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak), and a few hunched babushkas, in remembrance of communism’s victims. “Most are Communist,” Crow said, but he acknowledged that he hadn’t sorted the statues perfectly according to gradations of evil. Some had been moved years ago, not because of a historical reevaluation but during renovations when he built a batting cage for his kids, who are now grown. When they were little, he said, “the kids used to be scared of them.”

The garden is really a mishmash of 20th-century evil, evil-lite, and a few of Crow’s heroes (in the last category: Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, and Winston Churchill). “I have a number of people who are [just] dictators, like Pinochet and Juan Perón,” Crow said. “You can argue about Juan Perón, whether he was a force for good or a force for bad … You can argue about Mubarak.” He noted that Yugoslav President Josip Tito was preferable to Stalin, and Zhou Enlai (“one of my favorites”) was a big step up from Chairman Mao. “There are probably a few more guys in storage that I’ll eventually put out,” he said. Mustafa Kemal Ataturk: “Probably more for good than bad,” he said. “But it’s complicated.”

Last month, Crow’s eccentric hobby became a side drama in a broader scandal over his friendship and financial relationship with Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. Critics of that relationship drew attention to Crow’s garden statues as well as a small hoard of Third Reich memorabilia inside Crow’s enormous home library and museum. He owns a signed Mein Kampf, paintings by Hitler, and a Third Reich–era tea service. Crow said he hadn’t felt the need to sort the interior collection by level of evil, either. In the garden, he said, “I like these guys”—he motioned to Thatcher and Reagan, then to Che Guevara and Fidel Castro—“and I don’t like those guys. In my world, that’s blindingly obvious … But one thing I have learned from this is that I must not assume that things are obvious.”

“This is my era. I was born in 1949,” Crow said. “Communism was the great threat to the world.” The choice between capitalism and communism, freedom and serfdom, was a “big philosophical argument.” The Greatest Generation, he said, had a dramatic, existential shooting war. The Baby Boomers did not (“thankfully,” he added). “In my lifetime and your parents’ lifetime … we didn’t have the Battle of the Bulge or the storming of the beaches of Normandy.” But the big argument was worth memorializing. “I want us to remember it. I want us to learn from it,” he said. “And it’s pretty damn important that we remember it.”

“Sometimes I wonder if I should just get rid of it all,” he said. He knows that strangers have doubts about him, and about anyone who associates with him. “I’m not looking to be odd.” But the oddness was a colorful part of the case against his friend Thomas. “If you said, ‘Are you glad you did this?’ I would say, ‘I’m not sure.’”

When the twin Thomas and Third Reich scandals broke, I wrote that Crow is not a Nazi, and that to smear him as one is an offense against victims of actual Nazis, and against Crow himself. A week later, a public-relations firm representing Crow wrote to me to offer their client for an interview. When we met, Crow said he had read my article when it came out, and that very morning had reread the first couple of paragraphs, before hitting the Atlantic paywall. Even to be defended from this charge, he said, stung. “‘Harlan Crow Is Not a Nazi,’” he paraphrased the headline. “A bit too much like ‘Good News! Harlan Crow Stopped Beating His Wife.’”

Crow made clear that his preference would be not to talk at all about the current scandal—which had made him introspective about his relationship to politics, if not repentant. “My hope is that this is the last conversation I have on this topic in public,” he said. “I’m not the private person I was. I’m sad about that, but there’s nothing I can do. I just still kind of hope that it’ll all fade from memory, and I can go back to being just an old guy.”

He surely knows deep down that the desire to be “just an old guy” is somewhere between delusional and a forlorn dream. Crow is not even a normal old ultrarich guy.

His statue garden and in-home museum are nothing compared with the living friends and politicians he has collected: ex-presidents (George W. Bush and the late Gerald Ford are especially beloved), scholars and writers (Charles Murray, David Brooks), and foreign dignitaries (the socialist British Prime Minister James Callaghan was an early guest on his yacht, on a cruise with Ford up the Dnipro River to Kyiv in the 1990s). His patronage of the American Enterprise Institute—to name just one of the venerable conservative institutions that take his money—has placed him near the center of the conservative movement for decades.

And his relationship with Thomas is irregular to the point of suspicion. ProPublica’s investigation revealed that Thomas accepted various goodies from Crow, including luxury vacations on Crow’s yacht and jet, private tuition for Thomas’s grand-nephew, and a real-estate deal with fishy particulars. Crow bought a house owned by Thomas. Thomas’s mother lives there rent-free. Thomas’s failure to report these gifts and transactions has led to accusations that the most conservative justice on the Supreme Court votes according to the wishes of his wealthy friend, a prolific donor to right-leaning political candidates and think tanks. Even if Thomas votes autonomously, they say, for the sake of transparency and the Court’s integrity, he should have reported the gifts, hospitality, and transactions.

Rules and norms apply to justices with integrity and to justices without it, to free the former from suspicion and to expose the latter. Thomas has resisted these rules more aggressively than any other justice. His critics have enjoyed a feast of cynicism at his expense. “We should all have friends like Clarence Thomas’s,” Eric Levitz of New York magazine wrote. At Slate, Dahlia Lithwick and Lisa Graves described this behavior as “stunning” and “astonishing,” because of the “appearance of impropriety,” and because even if Crow has no business before the Court, he certainly knows people who do, and he supports think tanks that have submitted amicus briefs. (Although I agree that the transparency standard for justices should be a full monty—nothing less than total disclosure of financial arrangements—the accusation of corruption is different. Justices with connections to Harvard or its myriad donors, supporters, and alumni are not automatically corrupted by these connections. And Harvard, unlike Crow’s think tanks, is a respondent in the most prominent case currently pending before the Court.)

But even if justices are bound by strict rules, their unbound friends are still subject to speculation, reasonable and unreasonable, about the nature of their relationship to those in power. Crow is like most people, in that he feels he has acted with the purest and most honorable intentions. He is unlike many, though, in thinking that the world should take his word for it—and that if it does not, that’s the world’s fault, and not his.

“I probably have more influence than the ordinary Joe,” Crow told me. “But I still don’t think of myself as a center of influence. I think of myself as a real-estate guy that lives in Texas.”

One common feature of the rich and powerful is that they do not feel rich and powerful. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia, who is an absolute monarch, told me he couldn’t just rule by fiat. He listed all the ways in which he was constrained by history, by family, by tribal interests. Last month Joe Biden told a group of visitors to the White House that “the one thing I thought when I got to be president, I’d get to give orders. But I take more orders than I ever did.”

With Crow, the psychology is similar. The liberal world thinks he orchestrates a vast right-wing conspiracy, because he is in fact surrounded by huge numbers of influential people, some who want his money and access to power, and some who are just friends. But Crow kept insisting that he has little power over the American political scene. Even with his fantastic wealth, he was incapable of preventing the rise of the politicians he most abhors, in particular Donald Trump.

And although he often says he wants to go back to being just a normal guy, it is not obvious that a man is normal when he is standing with you in his house next to a life-size mannequin of Winston Churchill and makes no comment about it until prompted. In the one-minute walk to his home office we passed perhaps a hundred objects—paintings, death masks, statues, swords, and other curios—whose presence in any normal guy’s home would have merited a proud explanation. He said he stopped giving tours long ago, after realizing that “most people just want to see a rich man’s house.” Crow happily acted as docent on request, but on our first pass through the collection, the only object that he flagged for special interest was a small ziggurat of foil-wrapped breakfast burritos and a tray of doughnuts, to which The Atlantic’s photographer and I were welcome.

Clarence thomas and his family “have been dear friends for almost 30 years,” Crow said, denying that their friendship was political in any way. “It’s an ironic friendship, in the sense that I came from a world of silver spoons, and he came from a very difficult upbringing.” (Crow’s father, Trammell, who died in 2009, was at one point described in the press as the largest private landowner in the United States. Thomas did not see an indoor toilet until late in childhood.) Crow has taken Thomas on his yacht in Indonesia; he has hosted him at his resort in the Adirondacks.

I asked if he ever talked about law with Thomas. “I have never, nor would I ever, think about talking about matters that relate to the judiciary with Justice Clarence Thomas,” Crow said. He added that they “talk about the kind of things friends talk about,” such as weather and sports. In an email, he told me that “it’s not like we haven’t talked about work-related issues,” but that those conversations were casual and unrelated to jurisprudence. “It’s not realistic [for] two people [to] be friends and not talk about their jobs from time to time.” Thomas has spoken to him of his fondness for his clerks, or about bumping into Justice Stephen Breyer at Target. But Crow wrote that “it would be wrong” for him to talk about Court cases. “From my point of view, that is off limits. He and I don’t go there.”

Crow said he wasn’t a “law guy” and professed ignorance about any details of constitutional law. (The closest Crow has come to a Supreme Court case was in the early 2000s, when an architecture firm asked the Court to adjudicate a dispute with a firm in which Crow had a minority interest. The Court declined to hear the case.) “It would be absurd to me to talk to Justice Thomas about Supreme Court cases, because that’s not my world,” he told me at his house. “I could probably name maybe five or six cases. Brown v. Board of Education. Marbury v. Madison.” He thought for a bit and stopped at two. “We talk about life. We’re two guys who are the same age and grew up in the same era. We share a love of Motown.”

He wanted to be normal, he said. But I noted that Thomas is not a normal friend, and friendships with Supreme Court justices are laden with responsibilities that normal friendships are not. Singing Diana Ross together on the deck of a yacht in Bali would be wholesome fun with a non-justice. But with Thomas it raised all sorts of issues. Between choruses of “Baby Love,” did Thomas wonder whether his next trip to Bali depended on his continuing to vote a certain way? What guarantee did Americans have that their friendship transcended such doubts?

“I’m not trying to say I’m this moral paragon, because I’m not. I’m just a guy that made lots of mistakes in my life,” Crow said. “But I do believe that I’m on the right side of right, morally and legally.” He said that it was “kind of weird to think that if you’re a justice on the Supreme Court, you can’t have friends. That’s not healthy. Should I have changed my life in order to have these friends? Or should I behave differently around them because of who they are?” He said if the billionaire and patron of leftist causes George Soros were hunting buddies with the chair of the Federal Reserve, he would not particularly care. “If they are genuine friends and people of good character”—he said his friends’ interactions with Soros suggest that he is—“I don’t think it’s up to me to decide.”

“I’m not saying you’re wrong with your questions,” Crow told me. He recognized that character is “one of those highly subjective things.” But ultimately it is all that matters. “And I believe Justice Thomas to be a person of the highest character.”

For Crow, much hinged on this question of “good character.” In discussion of politicians, he often defaulted, in a way I found almost inspiringly optimistic, to analyzing them not by their policies but by their integrity. Integrity, he seemed to think, would isolate a politician or judge from influence, and would naturally incline that person toward a moderate, decent position. We discussed his nostalgia for a “good America,” whose politics existed on the spectrum between Reagan and Roosevelt, or better yet, between Romney and Obama (“an honorable man”), with his personal preference toward the Romney side. Thomas, he said, is “one of the most amazing and admirable people I know,” and it was as blindingly obvious that Thomas would not sell his soul for a series of vacations as it was that Harlan Crow was not a supporter of Adolf Hitler.

Moreover, the hospitality he offered to Thomas was not unusual. “For a long time, I’ve lived a certain lifestyle,” Crow said, sounding like he was about to confess to a kink. But the lifestyle he described was simply that of an extremely wealthy guy who likes to travel and host friends on holidays. “I’ve been successful. I have lived a comfortable life. I have a really big house,” he said. At his home in the Adirondacks, he said, a typical summer means 150 guests—work associates, parents of his children’s friends, a few wonks and political types. His yacht, too, is best understood as a floating extension of his hospitality. The only reason to have a yacht, he said, is to go places where one cannot go any other way—hopping around guano islands in the South Pacific, visiting the grave of a favorite Antarctic explorer on a tundra island in the South Atlantic, following the Northwest Passage. He likes to fill the staterooms with guests, both when he’s aboard and when he’s elsewhere.

“That’s the life I’ve lived. I don’t think there’s anything bad about it,” Crow said. He sees no reason to exclude Thomas from it. “I didn’t want to change my life.”

The ado over Thomas’s mother’s house seemed to baffle Crow completely. He said he considers Thomas’s rise “the kind of American story you dream about,” and he’d donated money in Thomas’s hometown of Savannah, Georgia, that would memorialize both his bootstrapped success and the Gullah-Geechee culture that produced him. Crow sent money to the Carnegie Library there; he bought the dilapidated former cannery where Thomas’s mother had worked (and gave the former owners a “life estate”—the right to remain living there until their deaths).

He said he’d had dinner at Thomas’s mother’s house “several times.” “She was a great cook, and probably still is at 94.” He’d asked Thomas if he could buy the house, at fair market value, and develop the area with the aim of eventually opening the house to the public to “honor” him. “I’m a real-estate guy,” Crow added modestly, and he figured that the neighborhood would improve if he bought and razed the drug dens and brothel on the same block, then sold the lots on the condition that the buyers build new houses. Thomas’s mother received a life estate as part of the transaction, which he said was “very common” in real-estate deals involving the elderly, and an “insignificant” expense in comparison to the cost of the deal as a whole.

“One day, I walked down that street with Justice Thomas, and there were mixed-race families living in the neighborhood,” he said. “The brothel and the crack houses were gone. There were kids riding bikes in the streets, families planning and working in their gardens. It was a neighborhood. And I’m very proud of that.”

Surely, I suggested, he could have structured the deal in a way that would not have involved writing a personal check to a Supreme Court justice. Create a foundation for public education, put impartial trustees on its board, and let it buy the house. Crow said he had done many deals in his life, and every one could, in retrospect, have been done a little better. This one wasn’t even a bad one, let alone corrupt. “It was a fair-market transaction, and I had a purpose,” Crow said. “I don’t see the foot fault.” But the idea that he had secretly corrupted his friend left him aghast. (I asked him whether he had any other financial relationships with Thomas or anyone related to Thomas, and he declined to answer, saying he doesn’t keep track of the hospitality extended to friends.)

Crow is aware that being denounced in the press is an occupational hazard of being absurdly rich, and that one of the unwritten rules of the billionaire life is that one must not complain about being a billionaire. (As Anthony Hopkins said, playing a billionaire in The Edge: “Never feel sorry for a man who owns a plane.”) But Crow certainly feels embattled. “If I go out and help an old lady across the street this afternoon, there’ll be something written about my diabolical purpose and evil intent.”

Crow’s sensibility is bound in the local culture of Dallas. I grew up there and recognized it instantly. It is not familiar to most Americans. Austin is proud of its bumper sticker keep austin weird. But Dallas’s weirdness is so deep that it perpetuates itself unintentionally, without noticing it. An auto-insurance agent specifies on his sign that he is named Ross but prefers to be addressed as “Pistol.” At the most famous historic site, you can have a picnic and watch tourists drive by and mimic the way John F. Kennedy’s head jerked “back and to the left” as it exploded. Crow has statues of fallen dictators in his yard, and those baffle outsiders. But I remember that Goff’s, the burger joint down the street from my house, had a statue of Lenin out front, salvaged in the 1990s from an Odesa, Ukraine, crane factory and outfitted with a plaque that said america won. It was all very Dallas, and even without the plaque everyone would have known that its owner planted it there to mock rather than revere the Soviet Union, much as a high-school student might steal and display his crosstown rival’s mascot.

Crow’s emphasis on integrity is also vintage Dallas. Dallas’s citizens may not have more integrity than anyone else, but they surely do talk about it more. A classicist friend told me he was asked to translate a Dallas family’s made-up motto, “Do the right thing,” into Latin. (His suggestion, Fac Rectum, was not accepted.) Dallas is an honor society, like much of the South. And it is no surprise that a wealthy Dallasite who aspires to be a good citizen would revile the politician who more than any other has obliterated the idea that integrity is a requirement for office.

The figure of Donald Trump looms over conversations with Crow, perhaps especially when his name hasn’t been uttered for some time. Crow’s loathing for Trump and Trumpian politics is well known. “Countries don’t survive forever,” he told me, and he thought “reasonably small groups” on the right and left in America were sowing discord. Without Trump, he said, “we wouldn’t have gone as nuts on the right as we have.” He said he had proudly self-diagnosed himself with “Trump derangement syndrome” and preferred not to sidetrack our conversation about Thomas by going on an “anti-Trump jihad,” although he was tempted to do so. He was morose and reluctant for much of our conversation but lit up when he noted how the country had “repudiated” extremists of the right and left in the 2022 elections. The extremists of the right were the Trumpists. “I don’t think the left has a Trump equivalent,” Crow wrote to me later. “Thank God.” But he does consider the “progressive wing of the Democrat party” extreme, and he said he wished it had even less power than it does.

Crow describes himself as “center right,” and he deviates from the Republican Party not only in his refusal to genuflect to Trump but also in other ways, such as his support for legal access to abortion. He is a backer of the No Labels movement, which is a quixotic—some say foolhardy—attempt to vanquish extremists by fielding a presidential ticket across party lines. He spends a great deal of energy cultivating politicians who might be bipartisan-curious. (I told him I wondered if that sort of grooming by rich donors had empowered Trump in the first place. Many voters don’t want their politics determined through backroom dealing. He acknowledged that he did not understand reactionary politics, and he committed himself to listening more to the views of those enraged by the power of people like him.)

But for Trump himself, his distaste is permanent and unalterable. Part of this animus comes from the stunning 2016 repudiation of Crow’s political causes, into which he has poured millions. But the animus is even deeper, I suspect. Crow’s view of politics, and the viability of his argument that a rich man and a Supreme Court justice can just be friends with yachting benefits, depends on voters’ and elites’ voting out people of bad character. “Trump is a man without any principles at all,” Crow wrote in an email. “Bernie Sanders has principles; I just think they’re wrong. Trump doesn’t have any.”

In superficial ways, the two men are similar. Like Trump, Crow is a real-estate developer with political interests and assets that require the use of scientific notation to estimate. Both men grew up rich, then took over his father’s empire. In almost every other respect, they are total opposites. Trump cratered the empire he inherited, while investing in the sleaziest possible ventures; under Crow’s stewardship, the family fortune increased. Crow is appalled at the accusation that he used a shady real-estate deal to funnel money to a crony—which is, frankly, the kind of thing Trump would do. Trump commands attention and bellows; Crow speaks in a reluctant mumble. Trump inflates his net worth; Crow does not. Trump contemplates pulling out of NATO. Crow says he has no time for any politician who wavers in supporting Ukraine. (“The Ukrainians’ courage is unique in recent history,” he wrote to me. “I believe they’ve earned the right to their own independence.”) Crow begs to be assessed on whether he is a person of “good character.” Not even Trump’s most loyal fans could keep a straight face if their leader asked the same.

And then there is the matter of the two men’s hobbies. The poet Clive James once observed that wealth and culture do not go together. As a rule, he said, “the bigger the yacht, the smaller the library.” Crow’s yacht, the Michaela Rose, could sleep every Supreme Court justice and still have room for Crow and the solicitor general. His library, which is a wing of his home, is not correspondingly small. It would be a jewel in the collection of any Ivy League school. He opens it more than 100 times a year for events and visits from schoolchildren and researchers.

Does Trump own any books? I browsed randomly on a few shelves in Crow’s library and found an early edition of Montesquieu’s L’esprit des Lois. Crow has a full-time archivist and librarian. At one point I asked Crow if he had in fact collected the signatures of every Supreme Court justice in American history. He paused, opened a small side door, and poked his head in to confirm with the librarian that the collection was complete. The librarian, who presumably sits there all day just waiting for such an inquiry, said they still lacked signatures from a handful of recent justices. (“Thanks!” Crow said, before closing the door.)

It is impossible to imagine Trump sailing for days in howling austral winds to reach the grave of Ernest Shackleton on South Georgia Island. Trump has no known friendships with Supreme Court justices, or indeed any friendships, period. Crow has many friends, and many acquaintances who have been his guests. One of his problems after the ProPublica exposé was that many possible character witnesses in his defense had been disqualified due to having accepted Crow’s hospitality. This includes Atlantic contributors who are employed, or have been employed, by think tanks he and his wife, Kathy, have funded, among them Arthur C. Brooks, a former president of the American Enterprise Institute, and Reihan Salam, the president of the Manhattan Institute as well as those who have dined or stayed at his homes, including the Atlantic contributing writer and New York Times columnist David Brooks.

“What about the hitler paintings?” I asked before leaving. He must have known the question was coming, but he took five full seconds before he gathered the courage to answer. “They’re put away,” he said.

“Permanently?”

He didn’t answer directly. He recalled a 2015 incident when he planned a fundraiser for Marco Rubio, and Democratic National Committee Chair Debbie Wasserman Schultz called his display of Hitler’s paintings “the height of insensitivity and indifference.” “So I took them down, and I put them in storage,” he said. But he sees nothing inherently wrong with displaying them. “Three World War II leaders—Churchill, Eisenhower, and Hitler— all being artists is in itself an interesting story,” he told me. “And I think it would be reasonable at some point to show pictures of all three of them together … But in the current environment, I’m going to say permanently—until I change my mind.”

He said he understood that certain objects mean different things to different people, and even though it was obvious to him that Nazis were bad, others might misread his intentions. “In a sensible world, people would be interested in things like that. But right now we’re not there,” he said. And the outrage over his Hitler paintings had shown him that he should consider how others feel. (This willingness to consider others’ feelings is itself a sign of his anti-Trumpishness.) “The idea that I might offend somebody, particularly somebody I care about, one of my friends, with this stuff—that hurts. I would never want to do that.”

“How about Hitler’s teapot and table linens?”

“Oh, they’re still upstairs,” he said. He admitted that Kathy had urged him to just put them away. “I’ve felt that right now it would be kind of deceptive to do that.” He said I could see the items but could not take photos.

We walked to a small room, away from the main floor of the library. “Kind of a catchall,” he said—a room with random items that didn’t fit elsewhere in his collection. Here was a sword owned by Douglas MacArthur, and another by a Japanese general present at the surrender. Then he turned, looking tense, to a display case with a rectangular leather cover, and opened it up, expecting to reveal the Nazi tableware within.

The case was empty, except for a sign that read not to commemorate, but to remember, in hopes that it may never happen again.

It was an awkward moment, and he seemed agitated at having misled me, even in this bizarre manner. “What I just said to you was wrong,” he said. “Somebody did something I didn’t know about.” He checked elsewhere in the room and found another empty case. “I didn’t know that. I’m not happy about it … I apologize.”

Crow looked ruffled. Even weirder than having Nazi memorabilia in your house is having it in your house but somehow losing track of it.

READ MORE

Tim Scott. (photo: Elizabeth Brockway/The Daily Beast/Reuters)

Tim Scott. (photo: Elizabeth Brockway/The Daily Beast/Reuters)

Rotimi Adeoye | Tim Scott’s Vision for America Isn’t for Black People

Rotimi Adeoye, The Daily Beast

Adeoye writes: "His personal story is inspiring, but his record as a U.S. Senator is one that doesn’t place much concern for Black Americans’ needs."

His personal story is inspiring, but his record as a U.S. Senator is one that doesn’t place much concern for Black Americans’ needs.

Sen. Tim Scott's life story is inspiring. Hailing from a black family with humble beginnings in South Carolina, the odds were stacked against him, making his ascent to the United States Senate all the more remarkable. With relentless determination and the invaluable support of public education, he blazed a trail through local politics in his thirties, defying expectations at every turn.

Scott, the only Black Republican in the Senate, on Monday officially announced he’s running for the 2024 GOP presidential nomination. But Scott’s vision for the country makes no sense at all.

Instead of boldly bridging the persistent gaps in wealth and racial equality that affected him, Scott’s policies would exacerbate them. While his personal journey stands as a powerful testament to the boundless potential of the American dream, his political track record paints a contrasting image—one where the advancement of Black individuals is woefully overlooked.

Let’s start with Sen. Scott’s record on the economy. When Donald Trump was president, Scott partnered with him on an idea called “Opportunity Zones.” The concept was simple and, on its face, seemed promising. The federal government would find Black and minority communities that needed a boost, and inject business and federal investment to revitalize them. However, once the program began, the exact opposite happened.

A study conducted by the Joint Committee on Taxation found a stark and unsettling inequality in investment distribution. Shockingly, a mere one percent of opportunity zones accounted for a staggering 42 percent of the total investment. If that wasn’t harrowing enough, an astonishing 78 percent of investments flowed into just five percent of the zones.

In combination with these alarming figures, a comprehensive report from The New York Times exposed the cruel reality that numerous Black entrepreneurs seeking funding were systematically excluded from the process. Regrettably, it appears that investors were predominantly fixated on high-return projects within the zones, such as opulent real estate developments, while neglecting the potential of lower-margin initiatives that could genuinely uplift Black communities by creating sustainable jobs and vital services.

The detrimental impact of Scott's policies on the economy do not end there. Scott was an ardent advocate of the radical Trump tax plan. He unabashedly boasted about his instrumental role in drafting the legislation declaring, “I helped write the bill for the past year, have multiple provisions included, and got multiple senators on board.” The plan has proven to be nothing short of a disaster for the very Black working families he claims to champion.

Rather than utilizing the tax code as a catalyst for advancing racial equity, such as by bolstering the Earned Income Tax Credit—an invaluable work credit that can provide financial support or reduce federal tax burdens—the Trump-Scott tax law has shamelessly tilted in favor of affluent households occupying the highest rungs of the income distribution. A damning report jointly published by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy and Prosperity Now reveals that white households within the top-earning one percent receive an exorbitant 23.7 percent of the law’s total tax cuts. On average, “white households receive $2,020 in cuts, while Black households receive $840.”

Furthermore, Scott's track record reveals a troubling pattern of actively undermining avenues of healthcare that could significantly benefit a majority of Black Americans.

One example is his staunch opposition to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and his efforts to defund crucial healthcare initiatives. Under the ACA, states were granted the option to expand Medicaid, a government healthcare program designed to provide vital care to millions of low-income Americans. While numerous states embraced this opportunity, Scott's own state chose not to participate.

He further displayed a lack of support for sustaining Medicaid funding for states that had previously embraced the ACA during the House Republicans’ campaign to dismantle it in 2017. Without hesitation, he confidently declared, “The reality of it is there is no way to get this done if you don’t make whole those states that were more fiscally responsible and did not expand.”

Medical professionals and extensive policy research have shown that Scott’s ideas on healthcare are incorrect. A study conducted by the Commonwealth Fund reveals the significant advantages associated with expanded Medicaid eligibility between 2013 and 2021. States that chose to expand their Medicaid programs experienced lower racial and ethnic disparities, providing enhanced coverage and improved access to healthcare services for their populations.

Scott’s failure to recognize these tremendous benefits further highlights his disconnect from the needs of Black communities, and his disregard for the importance of addressing racial inequities in our healthcare system.

It is crucial to acknowledge the profound impact that policies such as the ACA and a fair tax code can have in ensuring that all Black Americans have a shot at the American dream. The research unequivocally demonstrates the positive outcomes achieved when the federal government embraces these initiatives. Yet, Scott’s record is one of dismantling the progress we’ve made and reflects a concerning lack of understanding for the struggles faced by Black Americans.

Far from being a singular voting bloc or monolithic entity, the Black community is a diverse tapestry. Anyone who claims otherwise is gravely mistaken. Each voter within this community possesses their own unique set of concerns and priorities that must be addressed by any presidential candidate seeking their support. However, when examining Tim Scott's track record on these critical kitchen table issues that profoundly influence the lives of the majority of Black Americans, it becomes abundantly clear why his candidacy for president should be unequivocally rejected.

The importance of having leaders who wholeheartedly embrace and address the concerns that shape the lived experiences of Black Americans cannot be overstated. While Scott’s personal journey is undeniably remarkable, his absence in championing crucial causes for Black people raises serious doubts about his suitability for higher office.

We must demand leaders who unwaveringly prioritize the health, well-being, and prosperity of all Americans, regardless of their race or background. Settling for anything less in this critical moment is simply not an option. The urgency of the challenges faced by the Black community demands leaders who will go beyond rhetoric, and deliver substantive policies that uplift and empower. We cannot afford to compromise in our pursuit of a more just and equitable society.

READ MORE

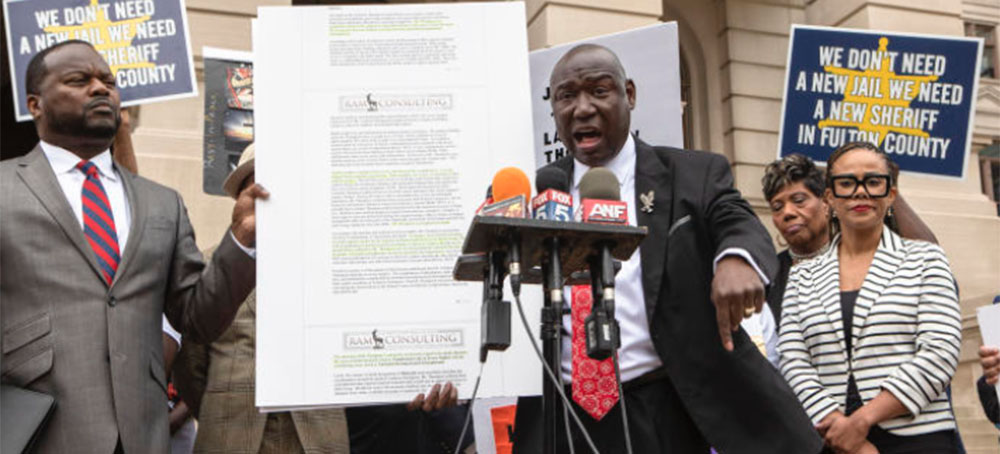

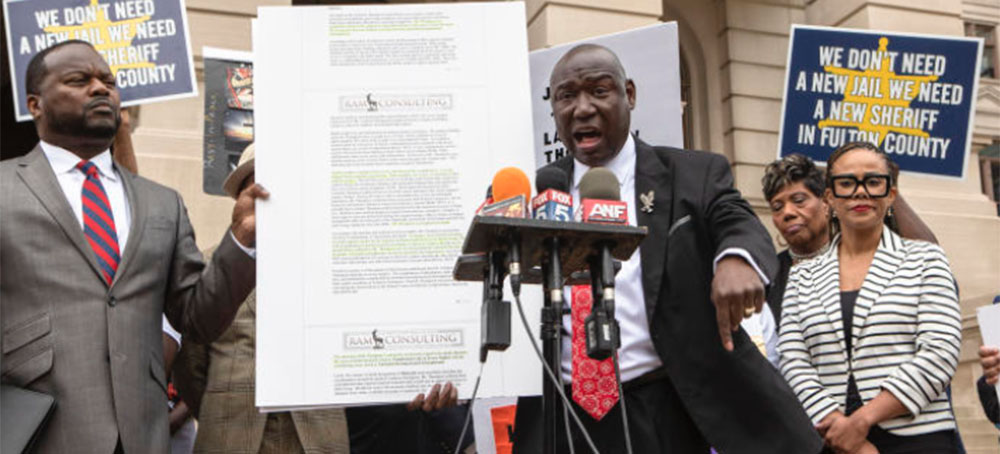

Civil rights attorney Ben Crump at a press conference Monday at the Georgia state Capitol in Atlanta on the results of an independent autopsy of Lashawn Thompson. (photo: Christina Matacotta/Atlanta Journal-Constitution/AP)

Civil rights attorney Ben Crump at a press conference Monday at the Georgia state Capitol in Atlanta on the results of an independent autopsy of Lashawn Thompson. (photo: Christina Matacotta/Atlanta Journal-Constitution/AP)

'Torture Chamber': Lashawn Thompson Family Autopsy Finds Jail Death a Homicide Due to 'Severe Neglect'

Jayla Whitfield-Anderson, Yahoo! News

Whitfield-Anderson writes: "A previous autopsy performed by the Fulton County, Georgia, medical examiner concluded that the cause of Thompson’s death was undetermined."

A previous autopsy performed by the Fulton County, Ga., medical examiner concluded that the cause of Thompson’s death was undetermined.

The family of Lashawn Thompson, a Fulton County, Ga., inmate who was reportedly found “eaten alive” by bedbugs and insects last year, on Monday announced the results of an independent autopsy that was paid for by the former NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick.

Dr. Roger A. Mitchell, the chair of the pathology department at Howard University, ruled Thompson’s death a homicide resulting from “severe neglect.” The first autopsy, performed by the Fulton County medical examiner, had concluded that Thompson’s death was undetermined.

“The undetermined autopsy will not be the final word,” Ben Crump, the family’s attorney, said during a news conference on Monday, adding that Fulton County will be held accountable for Thompson’s death in September 2022.

Thompson suffered from schizophrenia and was held in the psychiatric wing of Fulton County Jail, where he was untreated and was suffering from dehydration and malnutrition, according to the independent autopsy.

“Mr. Thompson was completely reliant on his caregivers to provide both day-to-day care as well as the acute life-saving care that was needed to save him from the untreated decompensated schizophrenia," Mitchell wrote in the autopsy report.

According to the independent report, Thompson had suffered from severe body insect infestation for more than 28 days. The jail was essentially “a torture chamber,” Crump said.

Crump said the additional autopsy proved there was criminal negligence in Thompson's death, which he called “the most deplorable death-in-custody case in the history of America.” Now the family is seeking accountability.

“I want to thank Colin Kaepernick for helping us find the answers, find the facts. It's something that we already knew in our heart, but he gave us the chance to prove it to the world,” Brad McCrae, Thompson’s brother, said at the news conference on Monday.

Kaepernick funds independent autopsies

The Thompson case isn’t the first where Kaepernick has stepped in to foot the bill for a second autopsy. In 2022 he started Know Your Rights Camp, an autopsy initiative that offers free second autopsies to family members whose loved ones died in encounters involving police.

In 2022, law enforcement killed approximately 100 people a month, totaling at least 1,197 people, in a particularly deadly year of police violence, according to Mapping Police Violence.

"We know that the prison industrial complex, which includes police and policing, strives to protect and serve its interests at all costs," Kaepernick told the Associated Press. "The Autopsy Initiative is one important step toward ensuring that family members have access to accurate and forensically verifiable information about the cause of death of their loved one in their time of need.”

For many such families, an independent autopsy serves to confirm, support or possibly contradict the initial findings.

For example, in 2020, the family of George Floyd hired two pathologists to perform an independent autopsy, which determined that Floyd died from asphyxia due to neck and back compression. The initial Hennepin County, Minn., medical examiner's report found no physical evidence suggesting that Floyd died from asphyxia, and stated that he died from cardiopulmonary arrest while he was being restrained.

While independent autopsies can be a financial burden, costing thousands of dollars, experts say families are entitled to a second opinion after the death of a loved one.

So far, the autopsy initiative has funded at least 42 autopsies across 15 states for police-related or in-custody death cases.

'A different set of eyes'

Lawrence Kobilinsky, a professor emeritus at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, told Yahoo News that families often seek out a second autopsy because they “may think that something was missed, or something was misinterpreted,” requiring a “different set of eyes.”

But Kobilinsky said two autopsies can result in different findings because “some people see things that other people don't.”

However, in deaths involving law enforcement, civil rights activists worry that there could be bias or impropriety in a county medical examiner’s autopsy.

“You have to look at the source of the autopsy,” Gerald Griggs, state president of the Georgia NAACP, told Yahoo News. “One is a dependent autopsy, which are dependent on the resources of the state. One is an independent autopsy, done by somebody that's not affiliated with the state. We know that Mr. Thompson died in the care and custody of Fulton County. So it's very difficult for the Fulton County medical examiner to be independent.”

But experts note that when second autopsies are performed, a body may not be in its original state. “You're not looking at a pristine body, you're looking at a body that's already been opened up and examined, and organs have been removed and analyzed,” Kobilinsky said.

Kobilinsky said autopsy is not a perfect science and depends on a medical examiner’s experience and judgment.

“A medical examiner will form their opinion not only from the autopsy, but from the circumstances surrounding the death, which they sometimes get from law enforcement or [eye]witnesses,” he said. But the difference between “an accident or a suicide or a homicide has serious consequences,” he added.

Is one autopsy enough?

Fulton County Sheriff Pat Labat, who has publicly acknowledged the wrongdoing at the Fulton County Jail, released a statement saying that he has not reviewed the independent autopsy report, but that "it was painfully clear there were a number of failures that led to Mr. Thompson's tragic death."

“I have already held the executive staff responsible for jail operations accountable by asking for and receiving the resignations of the chief jailer, assistant chief jailer of housing and assistant chief jailer, Criminal Investigative Division. Repercussions for anyone found to be negligent in Mr. Thompson’s care could come once the full investigation is turned over to the GBI [Georgia Bureau of Investigation] for review,” Labat said.

Griggs said both autopsies will be used, “because now you have two equally qualified experts. Jurors will be the ultimate determiner of what is fact.” Authorities have not announced any criminal charges in connection with Thompson’s death.

The autopsy completed by Mitchell took many weeks and provides full details on Thompson’s malnutrition, dehydration and psychosis.

“We have some real questions as to why the Fulton County medical examiner was not able to come up with a true cause of death,” Griggs said.

READ MORE

South Carolina Rep. Michael Rivers, D-St. Helena Island, left, talks to Rep. Joe Jefferson, D-Pineville, right, before the House begins debating an abortion bill on Tuesday, May 16, 2023, in Columbia, South Carolina. (photo: Jeffrey Collins/AP)

South Carolina Rep. Michael Rivers, D-St. Helena Island, left, talks to Rep. Joe Jefferson, D-Pineville, right, before the House begins debating an abortion bill on Tuesday, May 16, 2023, in Columbia, South Carolina. (photo: Jeffrey Collins/AP)

South Carolina House Passes Six-Week Abortion Ban After Hours of Contentious Debate

Sydney Kashiwagi, CNN

Kashiwagi writes: "South Carolina House members approved a controversial bill late Wednesday that would ban most abortions as early as six weeks into pregnancy, after having spent the last two days in contentious debate on the legislation."

South Carolina House members approved a controversial bill late Wednesday that would ban most abortions as early as six weeks into pregnancy, after having spent the last two days in contentious debate on the legislation.

Lawmakers had been called back for a special session this week by Republican Gov. Henry McMaster to continue work on Senate Bill 474, known as the “Fetal Heartbeat and Protection from Abortion Act,” which bans most abortions after early cardiac activity can be detected in a fetus or embryo, which can commonly be detected as early as six weeks into pregnancy, before many women know they are pregnant.

The bill will now head to the Republican-controlled state Senate, where lawmakers will consider changes made by the House. The Senate passed the initial version of the bill back in February.

Even if approved by the Senate, it remains to be seen whether the law would survive a court challenge. The state Supreme Court earlier this year struck down a similar six-week ban over privacy concerns.

But were the new legislation to go into effect, it would mean that the entire US South, with the exception of Virginia, has moved to significantly curtail abortion rights since the US Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade last year.

The state House voted 82-33 to advance the amended bill, with two Democrats joining Republicans in the chamber, but not before debate on the legislation dragged on for hours over multiple days.

Democratic lawmakers had filed more than 1,000 amendments to the legislation and vowed to make fellow legislators consider all of them, while Republicans said they would stay to work on the bill for as long as it took.

“We have no intention of pulling any amendments. We are going to make it hurt if they are going to force this on us,” Democratic state Rep. Beth Bernstein said.

Asked by CNN’s Jake Tapper on Wednesday whether the Democrats were “delaying the inevitable” passage of the measure, Bernstein conceded that “unfortunately” they were but that they also sought to raise awareness around it.

“[T]he reason these amendments are being filed is so we can have that voice and so people can understand what we’re doing at the statehouse is we’re effectively banning abortion,” Bernstein said on “The Lead.”

South Carolina passed a similar 6-week abortion ban in 2021, but the state Supreme Court struck it down earlier this year, concluding that the state constitution’s privacy protections require limits on the procedure to allow women sufficient time to end a pregnancy.

Recent efforts to pass further restrictions on abortion also faltered in April when the state Senate failed to pass the “Human Life Protection Act,” which would have banned most abortions in the state, in a 22-21 vote with five women voting against it – including three Republicans. The bill had previously passed in the state House and included exceptions for incidents of rape or incest.

Consideration on South Carolina’s latest abortion bill came as lawmakers in neighboring North Carolina moved on Tuesday to ban most abortions after 12 weeks after the state’s Republican-led General Assembly overrode a veto by Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper.

READ MORE

A memorial for the 19 students and two teachers killed at Robb Elementary School, in Uvalde, Tex., as seen Monday. (photo: Sergio Flores/WP)

A memorial for the 19 students and two teachers killed at Robb Elementary School, in Uvalde, Tex., as seen Monday. (photo: Sergio Flores/WP)

A Year After Uvalde, Officers Who Botched Response Face Few Consequences

Joyce Sohyun Lee, Sarah Cahlan and Arelis R. Hernández, The Washington Post

Excerpt: "In the year since the Robb Elementary School massacre in Uvalde, Tex., much of the blame for law enforcement’s decision to wait more than an hour to confront the gunman has centered on the former chief of the school district’s small police force."

A Post investigation finds numerous higher-ranking officers who made critical decisions remain on the job

In the year since the Robb Elementary School massacre in Uvalde, Tex., much of the blame for law enforcement’s decision to wait more than an hour to confront the gunman has centered on the former chief of the school district’s small police force.

But a Washington Post investigation has found that the costly delay was also driven by the inaction of an array of senior and supervising law enforcement officers who remain on the job and had direct knowledge a shooting was taking place inside classrooms but failed to swiftly stop the gunman.

The Post’s review of dozens of hours of body camera videos, post-shooting interviews with officers, audio from dispatch communications and law enforcement licensing records identified at least seven officers who stalled even as evidence mounted that children were still in danger. Some were the first to arrive, while others were called in for their expertise.

All are still employed by the same agencies they worked for that day. One was commended for his actions that day.

For many families of victims in the small Texas town, promises from top state law enforcement and government officials to hold all those responsible for the 77-minute delay in stopping the shooter today feel empty. Instead, they have learned to live alongside officers who faced no repercussions and remain in positions of authority in the community.

The officers shop at the same grocery stores as the families. They umpire weekly softball games. They live in the same neighborhoods. In some cases, they are blood relatives.

“When we see them, they put their heads down,” said Felicha Martinez, whose son was killed in the attack and whose cousin is a police officer who responded to the shooting. “They know they did wrong and wish they could go back and do it over again.”

Uvalde District Attorney Christina Mitchell Busbee has said she is still investigating the shooting response, leaving open the possibility that officers will face charges. If they did, however, it would be highly unusual, as officers rarely face criminal prosecution for missteps in crises.

The Texas Department of Public Safety opened an investigation into a half a dozen officers for wrongdoing but officially cleared almost all of them. DPS chief Col. Steven C. McCraw has said he would personally resign if his agency “as an institution” failed Uvalde. He insists it did not.

In all, four of the nearly 200 officers who responded from state and local agencies were fired after superiors found they made critical mistakes, according to public announcements. Four resigned, two of whom had loved ones who were killed that day. Nearly 190 federal officers, the majority from U.S. Border Patrol, were also on hand, but those agencies have denied several public records requests by The Post seeking information on their employment status.

Two officers the Department of Public Safety decided to dismiss are still employed in law enforcement, and others found ways to soften the blow from being fired or resigning after the massacre.

One senior Texas Ranger was given termination papers in January but remains on the force, state licensing records show. A DPS spokesman said he is currently suspended with pay, over four months later. The acting Uvalde police chief the day of the shooting resigned but was reelected to a county office he had held along with his law enforcement post. The first state police officer disciplined after the massacre was given the option to resign and now works for a local sheriff’s office.

The officers named in this article did not respond to detailed questions from The Post outlining its findings or declined to comment in multiple requests for interviews, citing the still-open investigation and pending civil lawsuits.

Many of the families, frustrated by the lack of accountability, have instead turned their focus to changing Texas’s lax gun laws, though thus far, the state legislature has been reluctant to do so. The disappointment with authorities and lawmakers has left them trying to make peace with how little has changed since 19 students and two teachers were killed.

“We all make mistakes, but this was a fatal mistake,” Javier Cazares said of the officers who stalled as the gunman kept shooting. He is haunted by the thought that his daughter, Jacklyn, 9, might have survived if they had entered sooner. “I hope it keeps them up at night too, but who knows?”

‘No active shooting’

The first indication something was terribly wrong in Uvalde arrived even before the gunman set foot in Robb Elementary.

After shooting his grandmother in the face, Salvador Ramos stole her truck and crashed it near a funeral home. Bystanders called 911 after he fired and walked toward the school.

What happened next has been repeatedly scrutinized by Texas lawmakers, federal investigators and community leaders trying to understand the dual horrors of that day: how an 18-year-old former student killed 21 people and why officers waited so long to stop him.

The Post’s reconstruction of what happened inside Robb Elementary last May 24 provides new details of key mistakes up and down the chain of command, starting at 11:31 a.m., when the first officer arrived at the school.

Body- and dash-camera footage shows that Uvalde Police Sgt. Daniel Coronado was the first supervising officer at the school. He arrived before Ramos entered the building at 11:33 a.m. The footage shows him parked nearby and taking cover as gunshots erupt. Coronado told investigators he then drove to the other side of Robb Elementary, thinking the gunman would try to flee in that direction.

“I still couldn’t believe that his whole mission was to take out kids. Never. It doesn’t cross your mind,” Coronado said in a post-shooting interview with investigators. “I think at that moment I still was thinking, okay, maybe he’s engaging officers or he’s just shooting to get away.”

Body-camera video captures Coronado running toward Robb Elementary with Uvalde school district police chief Pedro “Pete” Arredondo. City police Sgt. Donald Page is already inside. None are captured in available video and audio records stating they have command or otherwise establishing who would lead the response — one of the fundamental errors of the police response, experts say. Even as more officers continued to arrive, body-camera footage and other records show confusion throughout the ranks as to what the next steps would be.

Uvalde police policy urges officers to act quickly, stating that they should move swiftly to the shooter and “stop the violence.” It also notes that, ideally, the first two to five officers should form a team and enter the building. The footage shows that at least three officers were just beyond school grounds together before Ramos walked into the building.

Once inside, the gunman began firing as he burst into rooms 111 and 112, where he shot at dozens of children who had gathered to watch movies on the last day of school.

Two groups of officers — including several supervisors — gathered on each side of the hallway outside those classrooms.

“It’s an AR! It’s an AR! It’s an AR!” an officer yelled.

Minutes later, the shooter fired several rounds and two supervisors — Uvalde SWAT commander Sgt. Eduardo Canales and Uvalde Lt. Javier Martinez — were injured by fragments of building material.

Startled, Canales tells fellow officers, “We gotta get in there. He’s gonna keep shooting.” Martinez also acknowledged the urgency of the crisis, later trying to approach the classrooms before eventually retreating. In his post-shooting interview with investigators, stating he thought children were probably inside: “It’s a school. You’re going to assume there’s kids in there.”

But none of the officers shift to an active-shooter response. At 11:40 a.m. — four minutes after the officers are injured — Coronado radioed that the suspect was barricaded, according to a review of body-camera footage and available audio.

The Uvalde police department defines an active shooter as an armed individual likely to use “deadly force in an ongoing manner” and who has injured, killed or threatened other people, according to the agency’s officer guidelines. In a barricaded shooter scenario, an assailant is contained with little or no ability to harm others.

Coronado told investigators that he saw no signs of injuries, leading him to assume no children were at risk — even though during a lockdown, students are trained to stay quiet.

Texas Department of Public Safety radio communications show dispatchers repeat the assessment that officers are responding to a barricaded shooter at least 10 times, spreading the word to state officers that Ramos was not an active shooter threat.

“You don’t see any bodies, you don’t see any blood, you don’t see anybody yelling, screaming for help,” Coronado told investigators later. “Those are motivators for you to say, ‘Hey, get going, move.’ But if you don’t have that, then slow down.”

But officers soon started getting information that children were inside, The Post review found.

At 11:42 a.m. — nine minutes after the gunman stepped inside Robb Elementary — Coronado’s body camera captured audio of another officer confirming with school administrators that students were probably in the classroom.

Coronado is heard on a body camera saying: “Oh no, oh no.” But the available body-camera footage does not show him relaying this information to anyone else. Unbeknown to Coronado, his 10-year-old cousin, Xavier Lopez, was inside, struggling to stay alive from multiple gunshot wounds.

Officers at the scene gave at least 12 orders to hold back and not enter the classrooms despite hearing the gunfire blasts, The Post’s investigation found.

Several supervisors suspected there were children inside. “As much as he was shooting, I mean, he had to be shooting at something,” Page told investigators later. But time and again, radio communications and body-cam video captured supervisors telling each other and subordinates to wait. Uvalde County Constable Johnny Field tells the others, “There’s no active shooting.”

Gunshots, cries for help

Texas Ranger Ryan Kindell arrived around noon, about 30 minutes after the gunman entered the school. At the time, he was one of the highest-ranking Department of Public Safety officers at the scene. He told investigators he immediately recognized that someone needed to take charge and started organizing the responders stationed outside.

Yet he, too, failed to challenge the conclusion that Ramos was a barricaded subject — even as the gunman continued to fire and further information confirming children were inside reached officers, body-camera footage shows.

About 10 minutes after Kindell arrives, an officer’s body-camera footage captures the moment a dispatcher reveals a student had called 911 from inside one of the rooms. Kindell walks by and Canales and Field are in earshot as this information is shared loudly to those nearby, the footage shows.

That detail was quickly shared with Paul Guerrero, acting commander with the U.S. Border Patrol’s elite tactical unit, who arrived a minute later, according to body-camera footage. A rifle shield is brought in by a U.S. marshal. But Guerrero did not breach the classroom with his team for almost 40 more minutes, according to The Post’s review of available post-shooting interviews and videos.

“There’s victims in the room with us?” Guerrero asked an officer, body-cam footage shows, as he stands in the hallway outside the classrooms.

“Child on the phone, multiple victims,” the officer responds.

Despite that confirmation, officers continue focusing on trying to find a key to one of the two doors. Investigators now believe neither was probably locked. Arredondo repeatedly insisted on finding a “master key” and urged others to stay back.

“Tell them to f--- wait,” he told officers in the hallway.

At 12:21 p.m., the gunman fired his final burst of shots. Kindell, Guerrero, Coronado, Martinez, Field and Canales visibly reacted to the gunfire , but video footage and audio records show they did not change their response. The breach team led by Guerrero waited until 12:50 p.m. to enter the room and kill Ramos.

Law enforcement’s overall 77-minute delay came with potentially deadly consequences.

Three victims emerged from the school with a pulse but later died. For teacher Eva Mireles, 44, and Lopez, 10, critical resources were not available when medics expected they would be, delaying hospital treatment, an investigation by The Post, the Texas Tribune and ProPublica found last year. Another student, Cazares, 9, likely survived for more than an hour after being shot and died in an ambulance.

Gov. Greg Abbott (R) initially said that a “quick response” by law enforcement had saved lives. But two days after the massacre, authorities acknowledged officers had left a gunman in the rooms with children for more than an hour. Outrage grew as parents prepared to bury their children — some left barely recognizable by the AR-15-style weapon’s carnage.

An award for valor

In the initial aftermath, the state Department of Public Safety’s director put the blame for the botched response squarely on one man: Arredondo.

McCraw said the school police chief had incorrectly determined that the gunman was no longer an active shooter and that no more children were at risk. Arredondo oversaw the Uvalde district’s six-person police department. He has declined multiple interview requests but told the Texas Tribune he did not consider himself in charge of the scene.

Nearly a month after the shooting, he was placed on leave. Two months later, he was fired.

But earlier this year, Arredondo managed to upgrade his discharge status, which indicates the circumstances under which an officer leaves an agency, improving his prospects of future employment in law enforcement. The school district is attempting to overturn that.

A Texas House investigative report published in July spread blame across every law enforcement agency responding to the attack, noting more experienced agencies also failed to take charge.

A handful of other officers faced reprimand. Kindell was ordered fired, with McCraw writing in his termination letter in early January that the Ranger “should have recognized the incident was and remained an active shooter situation,” the Tribune reported. But records obtained exclusively by The Post show Kindell is still employed with the Department of Public Safety.

Travis Considine, a spokesman for DPS, characterized Kindell’s dismissal letter as a “preliminary decision” that will not be finalized until the officer is given a chance to meet with McCraw. In the meantime, Kindell has been “suspended with pay.”

Six other senior and supervising officers who The Post found were in a position to hear gunshots but did not immediately act, remain on the job. One officer — Guerrero, who took more than a half-hour to mount the assault that killed Ramos — later received a Department of Homeland Security award for valor for his actions that day.

Of the nearly 200 responding officers from state and local agencies, around 180 remain in law enforcement, according to records reviewed by The Post. Nine left their posts for jobs in other agencies.

For victim’s relatives, that tally is infuriating.

“Anyone who knew and sat there and listened to him reload, they should all lose their jobs,” said Brett Cross, the uncle and guardian of 10-year-old Uziyah Garcia, whom he called his son. “Anybody who made an order that they shouldn’t go in should face possible jail time.”

Unsatisfied with Arredondo’s firing, Cross camped for 10 days last fall outside the offices of Hal Harrel, then the Uvalde school district superintendent, pressuring officials to make good on their promises to hold officers accountable. His demands were partially met: The school district voted in October to suspend its entire police force. But he still wants to see more officers disciplined for inaction — and doesn’t hesitate to confront them when he sees them in Uvalde.

At one City Council meeting last year, Cross recalled, he stood toe-to-toe with the man he thought he recognized from one of the police body cam videos circulating on the internet, showing officers standing around while children were being killed.

“Is this you?” he recalled asking, showing the man an image on his cellphone of a large, bearded police officer in the Robb Elementary School hallway.

The man said it was. “What the f---, dude?” Cross spat out instinctively. He said the officer smiled and walked away: “Have a nice day.”

Mariano Pargas Jr. — who was serving as interim chief of the Uvalde police the day of the attack — was also soon suspended and later resigned. He is captured on body-cam footage telling Guerrero that a child had called from inside the room with the gunman, but like the others, available video and audio records show, he failed to take charge or push officers to enter and kill the gunman.

The suspension didn’t stop Pargas from running for reelection as a county commissioner.

Cazares who lost his daughter Jackie in the massacre — had never considered political office, but when he learned one of the officers condemned for inaction the day of the slaughter was running uncontested, he decided to challenge him.

“No, we can’t have that,” Cazares recounted thinking while campaigning as a write-in candidate.

But on Election Day, voters in Uvalde reelected every incumbent who was in office the day of the tragedy — including Pargas.

That night, Kimberly Mata-Rubio, whose 10-year-old daughter Lexi was killed, wrote on Twitter that, “I wanted to send a message, but, instead, the state of Texas sent me a message: my daughter’s murder wasn’t enough.”

‘No officer has to save you’

There have been moments in the past year where Uvalde families said life seemed almost normal despite the tunnel of their unbearable loss. There were quinceañeras and graduations that were almost enjoyable. And then there are the moments of anguish.

Martinez, who son Xavier Lopez was killed, comes from a family filled with law enforcement officers — including Coronado. These days, they have no communication.

“If we were to run into each other, they try to say hi,” she said, “but I want nothing to do with them.”

The parents, siblings and friends of those killed relive their agonizing stories over and over again in interviews, in therapy and in legislative hearings where they push for gun control. Sometimes they read prepared remarks from their phone’s Notes app or paper. Some can deliver gut punches on the spot through breathless gulps and hot tears.

“Tess didn’t have a choice in life or death, but you as leaders have a choice of what my daughter’s life will be remembered for,” Veronica Mata said about her slain daughter during an April bill hearing. “Will she die in vain? Or will her life have saved another child? Maybe, your child.”

Yet while the broader gun control community has been supportive, in Uvalde, the victims’ families face critics. They have been accused of making things political. Their unapologetic advocacy makes neighbors — especially those flying “Thin Blue Line” flags — uncomfortable. Local clergymen have criticized them in newspaper op-eds as thirsting for revenge instead of forgiveness. It hurts, a few said, but it doesn’t discourage them.

For Mata-Rubio, it’s the memory of her daughter Lexi that keeps her going. While sitting in a lawmaker’s office recently, the mother of four other children said she looked up and felt like she saw Lexi with her, biting her nails and bored while playing on her iPad, wanting to go home.

The apparitions remind her what she’s fighting for.

Mata-Rubio said she has too many what-ifs of her own to worry about whether the cops feel regret, shame or sorrow about their actions that day.

“I should never have left her in the hands of anyone else,” she said. “It was my job to protect her.”

But the massacre also left her convinced of something else: “No officer has to save you. They have immunity, they won’t face punishment. This country needs to be aware of that.”

READ MORE

The double homicide of British journalist Dom Phillips and Brazilian indigenous Bruno Pereira sparked protests across Brazil. (photo: BBC)

The double homicide of British journalist Dom Phillips and Brazilian indigenous Bruno Pereira sparked protests across Brazil. (photo: BBC)

Dom Phillips and Bruno Pereira: Brazilian Former Official Indicted Over Murders

BBC News

Excerpt: "Police have indicted the former head of Brazil's Indigenous protection agency for his alleged role in the murder of British journalist Dom Phillips."

Police have indicted the former head of Brazil's Indigenous protection agency for his alleged role in the murder of British journalist Dom Phillips.

Police didn't identify the official, named as Marcelo Xavier by state media.

He was accused of "possible malice" for failing to act on information which police believe could have prevented Phillips' death.

Phillips and Brazilian indigenist Bruno Pereira were killed on a reporting trip in the Amazon rainforest last year.

Three men have separately been charged with carrying out the double homicide.

Pereira was accompanying Phillips, a veteran journalist who wrote for newspapers including The Guardian and Washington Post, by boat through the Javari Valley near Brazil's border with Peru as part of Phillips' research for a book on conservation efforts in the Amazon.

The huge region is home to around 6,300 Indigenous people from more than 20 groups and is under threat from illegal loggers, miners and hunters.

The pair went missing on 5 June 2022 and their bodies were recovered 10 days later.

The latest development in the case saw federal police announce charges against the former president and former vice-president of Brazil's National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples (Funai) agency.

While authorities did not name the two officials, a number of media outlets including state broadcaster Agencia Brasil identified one ex-official as Mr Xavier.

They became aware at a meeting held in 2019, and through other documents, that the life of agency employees - such as Pereira - was at risk in lawless areas like the Javari Valley.

But they did not take the "necessary measures" to protect them, police said in a statement.

"In this way, they would have assumed the risk of the result of their omissions, which culminated in the double homicide," the force added, appearing to suggest Mr Xavier's failure to protect workers indirectly paved the way for the murders of Phillips, 57, and Pereira, 41.

Pereira had previously been employed by Funai but was not at the time of his death.

His and Phillips' disappearance sparked a manhunt in the remote area of the rainforest, and a global outpouring of support for their safe return.

After their bodies were discovered and identified, police found the pair had been shot dead, burned and buried in the forest.

Three men were later charged with their murders - Amarildo Oliveira, his brother Oseney Oliveira and Jefferson Lima.

They are thought to have decided to kill the pair when Pereira asked Phillips to take a picture of their illegal fishing boat.

READ MORE

A woman looks at the destruction in Haulover, Nicaragua in 2020 after the passage of Hurricane Iota. (photo: Inti Ocon/AFP)

A woman looks at the destruction in Haulover, Nicaragua in 2020 after the passage of Hurricane Iota. (photo: Inti Ocon/AFP)

Extreme Weather Has Killed 2 Million People Over Past Half Century, UN Says

Associated Press

Excerpt: "The economic damage of weather- and climate-related disasters continues to rise, even as improvements in early warning have helped reduce the human toll, the U.N. weather agency said Monday."

The World Meteorological Organization tallied nearly 12,000 extreme weather, climate and water-related events over the past half-century that caused economic damage of $4.3 trillion.

The economic damage of weather- and climate-related disasters continues to rise, even as improvements in early warning have helped reduce the human toll, the U.N. weather agency said Monday.

The World Meteorological Organization, in an updated report, tallied nearly 12,000 extreme weather, climate and water-related events over the past half-century around the globe that have killed more than 2 million people and caused economic damage of $4.3 trillion.

The stark recap from WMO came as it opened its four-yearly congress among member countries, pressing the message that more needs to be done to improve alert systems for extreme weather events by a target date of 2027.

“Economic losses have soared. But improved early warnings and coordinated disaster management has slashed the human casualty toll over the past half a century” WMO said in a statement. The trend of rising economic damage is expected to continue.

The Geneva-based agency has repeatedly warned about the impact of man-made climate change, saying rising temperatures have increased the frequency and intensity of extreme weather — including floods, hurricanes, cyclones, heat waves and drought.

WMO says early warning systems have helped reduce deaths linked to climate and other weather-related catastrophes.

Most of the economic damage between 1970 and 2021 came in the United States — totaling $1.7 trillion — while nine in 10 deaths worldwide took place in developing countries. The economic impact, relative to gross domestic product, has been felt more in developing countries, WMO says.

WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas said the cyclonic storm Mocha that swept across Myanmar and Bangladesh this month exemplified how the “most vulnerable communities unfortunately bear the brunt of weather, climate and water-related hazards.”

“In the past, both Myanmar and Bangladesh suffered death tolls of tens and even hundreds of thousands of people,” he said, alluding to previous catastrophes. “Thanks to early warnings and disaster management these catastrophic mortality rates are now thankfully history.”

“Early warnings save lives,” he said.

The findings were a part of an update to WMO’s Atlas of Mortality and Economic Losses from Weather, Climate and Water Extremes, which previously had covered a nearly 50-year period through 2019.

WMO acknowledges some caveats to its report: While the number of disasters has risen, some of that may be due to improvements in reporting about extreme weather events that might have been overlooked in the past.

While the findings account for inflation, WMO cautioned that estimating the economic toll can be an inexact science, and the reports could understate the actual damage.

Worldwide, tropical cyclones were the primary cause of reported human and economic losses.

In Africa, WMO counted more than 1,800 disasters and 733,585 deaths related to weather, climate and water extremes — including flooding and storm surges. The costliest was Tropical Cyclone Idai in 2019, which ran to $2.1 billion in damages.

Nearly 1,500 disasters hit the southwest Pacific, causing 66,951 deaths and $185.8 billion in economic losses.

Asia faced over 3,600 disasters, costing 984,263 lives and $1.4 trillion in economic losses — that cost mostly due to the impact of cyclones. South America had 943 disasters that resulted in 58,484 deaths and over $115 billion in economic losses.

Over 2,100 disasters in North America, Central America and the Caribbean led to 77,454 deaths and $2 trillion in economic losses.

Europe saw nearly 1,800 disasters that led to 166,492 deaths and $562 billion in economic losses.

Last week, WMO forecast a 66% chance that within the next five years the Earth will face a year that averages 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than in the mid-19th century, reaching a key threshold targeted by the Paris climate accord of 2015.

READ MORE

Contribute to RSN

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

Update My Monthly Donation

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611