Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The F.B.I. director promised to save American democracy from those who would subvert it—while his secret programs subverted it from within.

But by that fall, more than two years into Nixon’s Presidency, Hoover had become a liability, the historian Beverly Gage explains in her crisply written, prodigiously researched, and frequently astonishing new biography, “G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century” (Viking). He was seventy-six, and showing his age, napping for hours in his office in the afternoons. He was also showing, in Gage’s words, “increasing levels of vitriol and instability,” informing the White House, for instance, that the four student demonstrators shot to death by National Guardsmen at Kent State had “invited and got what they deserved.” In 1970, for the first time in a career in which he had enjoyed remarkable levels of public approval, half of Americans polled by Gallup said that they thought he should retire. And there was worse to come.

On the night of March 8, 1971, burglars broke into an F.B.I. field office in Media, Pennsylvania, and made off with a cache of top-secret files. The culprits, whose identities would not be revealed for years, were a small band of Quaker-inspired pacifists who suspected that the F.B.I. had infiltrated the antiwar movement and other New Left activities. They were proved right by the documents, which they pored over and then began releasing in tranches to two members of Congress, Senator George McGovern, of South Dakota, and Representative Parren Mitchell, of Maryland, and to three newspapers, the Los Angeles Times, the Washington Post, and the New York Times. (McGovern, Mitchell, and the L.A. Times turned the files over to the F.B.I.; the Post and, later, the Times chose to report on their contents.) Hoover’s F.B.I., as the files established, had engineered a clandestine campaign aimed at “disrupting” and “neutralizing” left-wing and civil-rights organizations through the use of informants, smear campaigns, and callous, cunning plots to break up marriages, get people fired, and exacerbate political divisions. One of the files made reference to the name of the project: COINTELPRO, which stood for “counterintelligence program.” It would take years of digging by journalists, reams of Freedom of Information Act requests, and the dogged work of the Church committee—a congressional body, chaired by the Idaho senator Frank Church, that was formed in 1975 to look into the nation’s intelligence activities—to reveal substantially more about the program. Under its auspices, the F.B.I. had wiretapped Martin Luther King, Jr.,’s hotel rooms and recorded his sexual assignations. In 1964, soon after King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, a package containing the tapes arrived at his home. His wife, Coretta Scott King, opened it. Inside was a letter, concocted by the F.B.I. and purporting to be from a disappointed Black supporter of King’s, that called him “a filthy, abnormal animal” while seemingly urging him to kill himself. COINTELPRO operatives went on to spread a false rumor that the actress Jean Seberg was pregnant by a member of the Black Panthers. (In fact, she was married and pregnant with her husband’s child, but, after the rumor circulated, she gave birth prematurely and lost the baby.) In 1969, COINTELPRO operatives collaborated with Chicago police in the raid that killed the twenty-one-year-old Black Panther leader Fred Hampton in his bed. Hoover, Gage notes, approved a bonus for the F.B.I. informant who had drawn a map of Hampton’s apartment, including where he slept.

In the outcry that followed the early revelations about COINTELPRO, some members of Congress called for Hoover’s resignation. Life ran an ominous image of him as a marble bust, with the cover line “Emperor of the F.B.I.” Even Nixon’s adviser Patrick Buchanan told the President that Hoover should go, before his reputation was picked over “by the jackals of the Left.” Amid public criticism, Hoover had—to Nixon’s annoyance—become uncharacteristically cautious on certain fronts. He was less aggressive than Nixon wanted him to be, for instance, in pursuing whoever had leaked the Pentagon Papers. In frustration, Nixon secretly authorized the creation of a team of intelligence operatives who would do whatever, in his view, had to be done. The team came to include a former F.B.I. agent, G. Gordon Liddy, and was code-named the Plumbers.

All that remained was to cut Hoover loose. The trouble was that he had no intention of leaving. He had already finagled an extension of the mandatory federal-government retirement age of seventy. By temperament and by ideology, he was inclined to hold on to his power in perpetuity. The President and his staff spent months scheming about how, exactly, to maneuver him out. They considered various deal sweeteners—including the idea of appointing Hoover to the Supreme Court. Nixon’s advisers composed a script for the President to use at a breakfast meeting with Hoover that morning in 1971, in which he would be assured that, if he stepped down, he would leave with “full honors (medal, dinner etc.).” The two men spoke for almost an hour at the White House, Gage tells us. But, in the end, Nixon could not bring himself to recite the script.

In fact, the only commitment that came out of the meeting was a concession from Nixon to increase the F.B.I.’s personnel budget. Nixon, in his memoirs, said that he retreated out of loyalty to a great man and an old friend. But to those in his circle, Gage writes, the President “revealed something more acute: a fear of Hoover’s skill at wielding power, and a sense that even the President was no match for the F.B.I. director.” Nixon told his aides, “We may have on our hands here a man who will pull down the temple with him, including me.” Several more months passed, during which the President was always just about to lower the boom. But when Hoover died—at home, of heart failure, on May 2, 1972—he was still the director of the F.B.I. “That old cocksucker!” Nixon exclaimed when he got the news from his chief of staff. Gage puts that reaction down to equal parts surprise and admiration for the man Nixon used to call his best personal friend in government.

Previous accounts of how Hoover clung to his position for so long have tended to stress his capacity to intimidate, and even blackmail, Presidents. Gage certainly does not deny Hoover’s talent and taste for these dark arts, but she wants to emphasize a simpler explanation, one less flattering to America’s self-regard. For a very long time, most Americans admired Hoover. In the nineteen-thirties, the Bureau’s white-collar officers acquired a new mystique when, at Franklin Roosevelt’s behest, they took on gangsters such as John Dillinger and Pretty Boy Floyd. For the first time since the Bureau’s founding, in 1908, agents were allowed to make arrests and carry guns—they shot Dillinger down as he left a movie theatre in Chicago, where he’d been watching a gangster picture. Though initially wary of the press and publicity, Hoover proved adept at turning them to his advantage. The Bureau opened its doors to the public for tours, and coöperated with Hollywood studios on a spate of films and, later, a TV series that glamorized F.B.I. agents and offered tantalizing glimpses of the agency’s state-of-the-art forensics. (My father acted in one of these F.B.I. lovefests, a B movie called “Parole Fixer,” from 1940. He was treated to a trip to headquarters, including a turn in the basement shooting range, and a highly flattering, personally autographed charcoal portrait of Hoover.) Outside the director’s office was a display case that contained an array of confiscated weapons, along with John Dillinger’s death mask and bloodstained straw boater.

But Hoover’s purview took in far more than crime. By the late nineteen-forties, he had become the country’s most reliable anti-Communist warrior, more sober (in all senses of the word) and less erratic than Joseph McCarthy, and in it for the long haul. While husbanding his hoard of secrets, he managed to fashion himself into a sort of avuncular avatar of conservative Americanism. Until the COINTELPRO revelations, that persona insured his wide appeal. In interviews with reporters and in speeches before women’s clubs and the American Legion, Hoover extolled Christian faith and the importance of Sunday school; inveighed against “sob sisters,” defense lawyers, “convict lovers,” criminal-justice reformers, and civil-rights “agitators”; and harped on the unrelenting threat of Communism to the American way of life. “The truth is that Hoover stayed in office for so long because many people, from the highest reaches of government, down to the grassroots, wanted him there and supported what he was doing,” Gage writes. In 1964, after he gave a press conference in which he denounced King as America’s “most notorious liar,” fifty per cent of Americans sided with Hoover and just sixteen per cent sided with King. (The rest were undecided.) And, as the Nixon story shows, Hoover’s crepuscular hold over Presidents was tenacious. He served under eight of them, four Republicans and four Democrats, and, Gage makes clear, most were either beholden to him or scared of him, or both.

There have been other big, ambitious biographies of Hoover, but “G-Man” is the first in nearly three decades. One advantage to writing about him now is that, in the realm of national security, revelations burble up over time, files get declassified, FOIA requests haul out unexpected specimens in their nets. But some of Gage’s freshest takes concern Hoover’s upbringing in a respectably middle-class but emotionally beleaguered family, and the formation of his racial attitudes in a college fraternity with a sentimental attachment to the Jim Crow South. Many of the book’s other sharp assessments come not from secret documents but from generally available historical sources that the author has read with close attention or particular nuance.

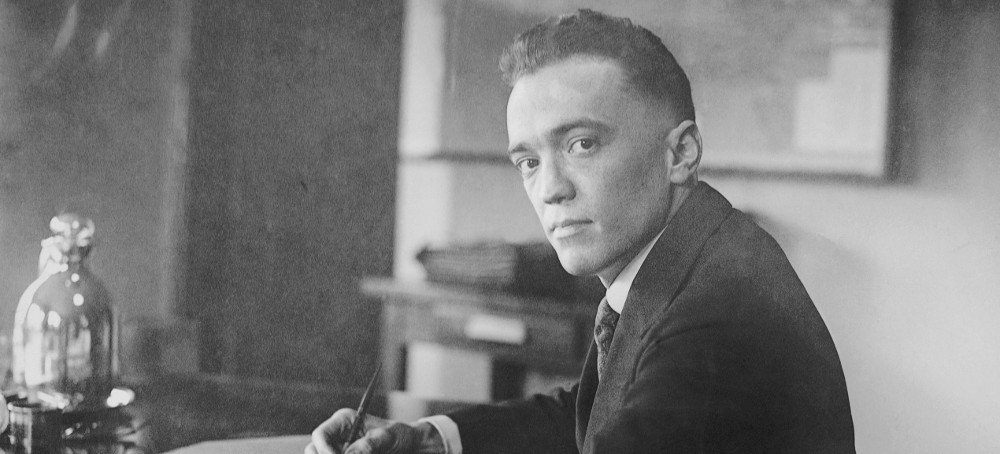

Hoover was born on January 1, 1895, in Washington, D.C., the city in which he would always live. His father, Dickerson Hoover, worked for the federal government, printing maps for the Coast Survey. He and his wife, Annie, had three children before Edgar, the youngest, arrived. One daughter had died of diphtheria at the age of three, during a vacation to Atlantic City, a blow from which the family seems never to have entirely recovered. Edgar was, Gage says, “an ambitious, hard-working child, eager to please his teachers and parents alike.” The family was loving, his father gentle and affectionate. He was also, for much of Edgar’s life, gripped by severe depression. When Hoover was a teen-ager, Dickerson was institutionalized for a time at a sanitarium in Laurel, Maryland. He died in 1921, at the age of sixty-four; the death certificate listed the causes as “melancholia” and “inanition”—vague diagnoses that hinted at how little effective treatment existed for the mentally ill. It’s difficult to know exactly how his father’s shadowy condition affected Hoover; there are no extant letters or journals that reveal how he felt about it. But Gage suggests that he was probably ashamed of his father, viewing his depression as weakness. A niece of Hoover’s recalled that he seemed angry about it: “He never could tolerate anything that was imperfect.”

The Washington that Hoover grew up in had the largest Black population of any city in the U.S., and was becoming more rigidly segregated. He attended an all-white public high school and went on to study law at George Washington University, an institution that did not admit Black students until 1954. At G.W., in what Gage argues was a portentous step, Hoover joined the Kappa Alpha fraternity. Founded in 1865 in honor of Robert E. Lee, Kappa Alpha was, according to Gage, a bastion of the Lost Cause mythology that glorified the defeated plantation culture of the slaveholding South. As late as the nineteen-fifties, the fraternity’s chapters were still holding Confederate dress balls, blackface minstrel shows, and “secession ceremonies.” Hoover remained a loyal alum all his life. Kappa Alpha became, Gage reports, his “chief source of sustenance and friendship”—a model for the overwhelmingly male, virtually all-white, sociable but hierarchical and ritual-bound F.B.I. that he built up as its director. Through the fraternity’s network, he “gained entree to Washington’s political elite,” especially circles dominated by Southern members of Congress. Perhaps even more important, Kappa Alpha “solidified the conservative racial outlook he would preserve, with minor variations, for the rest of his life.”

Hired at the Department of Justice in 1917, Hoover hunkered down and never left. He had held a previous job as a clerk at the Library of Congress, a two-year stint that sparked his zeal for collecting and classifying information. At Justice, he was assigned to the Bureau of Investigation, then a relatively poky subdepartment known to the public, if it was known at all, for sniffing out violations of the 1910 Mann Act. That changed when Woodrow Wilson’s Attorney General, A. Mitchell Palmer, began watching political subversives—anarchists, socialists, strike organizers, the occasional mail bomber, and not a few pacifists who grumbled into their liberty cabbage about Wilson or his war. In 1919 and early 1920, Palmer ordered a notorious series of raids, banging on doors to arrest and, when possible, deport suspected radicals to Russia, Eastern Europe, or Italy. Palmer picked the young Hoover to head the new Radical Division, which organized these raids. He took to the work with enthusiasm, meticulously filling the cabinets at headquarters with thousands of index cards on troublemakers across the country.

It was “an unprecedented experiment in peacetime political surveillance” that marked Hoover for life, Gage writes. When he and Palmer were challenged by civil libertarians, a new category that rose up partly in response to the raids, it “brought out an ugly, vindictive side to Hoover’s personality—one that had always been there, perhaps, but that had been controlled by a steady diet of praise and success.” Now he established a habit that he would retain for the rest of his life, of turning critics into enemies—and investigating them as such. His righteousness, combined with bureaucratic acumen and political savvy, won the admiration of his superiors. In 1924, he became the acting and then the permanent director of what was still called the Bureau of Investigation. There were those who warned that he’d been tainted by the excesses of the Palmer Raids; Felix Frankfurter, the future Supreme Court Justice, was one of them. But Hoover was entrenched and wily, and he struck a modern note—rejecting rough stuff like the third degree for interrogating wrongos, and upholding forensic innovations, such as a national repository of fingerprints. He was what we might now call data-driven.

Was Hoover gay? I would have thought that it was a settled matter by now, but I would have been wrong. In a recent book, “Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington,” the journalist James Kirchick writes, “While it’s certainly plausible that Hoover was gay and that Tolson was his lover, the only evidence thus far adduced has been circumstantial.” In 2011, when Clint Eastwood made a bio-pic about Hoover that suggested he and Tolson were romantically involved, the Washington Post ran an article about ex-F.B.I. agents who angrily denied the notion. It’s true that, in the absence of more direct evidence, we can’t know. But Gage, who handles the question deftly and thoughtfully, will leave most readers with little doubt that Hoover was essentially married to Tolson, a tall, handsome Midwesterner with a G.W. law degree who went to work at the Bureau in March of 1928, and whom the press habitually referred to as Hoover’s “right-hand man.” Neither of them ever married, or, it appears, had a serious romantic relationship with a woman. After Hoover’s mother died, in 1938—he had lived with her in the family home until then—it was bruited about that now, in his mid-forties, he was marriageable at last. Hoover half-heartedly fanned the embers of a convenient rumor that he just might be engaged to Lela Rogers, the age-appropriate, fervently anti-Communist mother of Ginger. In 1939, he gave an interview in which he claimed to have been searching in vain “for an old-fashioned girl,” adding that “the girls men take out to make whoopee with are not the girls they want as the mother of their children.” Meanwhile, the only person with whom he seems to have enjoyed a documented flirtation, though it was chiefly epistolary, was an F.B.I. agent he had assigned to hunt down Dillinger, a young man named Melvin Purvis. In a correspondence from the thirties that Purvis, not Hoover, saved, the director dwelled admiringly on his agent’s swoon-worthy Clark Gable looks; as Purvis’s boss, he alternately promoted him and punished him for showboating and other infractions. (After forcing Purvis out of the Bureau, Hoover never spoke to him again; he did not even acknowledge his death, by suicide, in 1960.)

Beginning in the mid-nineteen-thirties, Hoover and Tolson, confirmed bachelors, as my grandparents would say, were almost inseparable. Though they did not live together in Washington, they took a car to work together every morning and lunched every day at a restaurant called Harvey’s. They went to New York night clubs, Broadway shows, and the horse races à deux, and vacationed together—Miami in the winter and La Jolla for the entire month of August every year. (Gage offers a close reading of photographs Hoover took in Miami one year, which included tender shots of a shirtless Tolson at play on the beach, and asleep in a deck chair.) Social invitations and holiday greetings from anyone who knew Hoover at all well and wanted to stay on his good side were addressed to them both. When Hoover died, he left the bulk of his estate to Tolson. F.D.R.’s son Elliott later said that his father had heard the rumors about Hoover’s homosexuality but didn’t care “so long as his abilities were not impaired.” It was possible for people to know the deal and to acknowledge it only tacitly, if at all, and for Tolson and Hoover to hide in plain sight.

What Hoover felt about all this remains elusive—a frustration, surely, for the biographer, and occasionally for the reader. We do know what Hoover did when, for example, he heard gossip about his sexuality or was asked to gather information about the sexuality of people less supremely insulated than he was. If an F.B.I. agent overheard you suggesting that Hoover was gay, you could anticipate an uninvited visit from clean-shaven men in hats, and a conversation in which you were told to shut up or else. Gage describes one such incident, from 1952, in which an employee at a D.C. bakery frequented by G-men told them that a guy he’d met at a party had asked if he’d “heard the director is a queer.” The report reached Hoover, who, Gage says, sent agents to the man’s house “to threaten and intimidate him into silence.”

Moreover, Hoover dutifully played his part in the “lavender scare” of the nineteen-fifties, which targeted homosexuals working in government for exposure and expulsion. (The excuse was that they posed a security risk, since it was thought that they were somehow uniquely vulnerable to blackmail, and that, like Communists, they made up a kind of secret society lodged in the heart of our institutions.) Hoover did not speak publicly about the issue the way he did about the Communist threat. But he obtained from the D.C. police the names of people arrested for “sexual irregularities” and passed them along to the White House. Those who worked for the government in any capacity, from filing clerk to Cabinet secretary, were supposed to be fired—and barred from all future government work. Perhaps he thought that his willing participation in a gay witch hunt would deflect attention from his own private life; perhaps he considered himself and Tolson different from the sexual irregulars the cops were rounding up. In the early nineteen-sixties, when a chapter of the Mattachine Society, a gay-rights organization, started up in Washington, Hoover immediately had its meetings monitored by informants. Some of the merrier men of the Mattachine, for their part, seemed to have got a kick out of sending Hoover invitations to their events. Gage reports on a memo in the files that reads, “This material is disgusting and offensive and it is believed a vigorous objection to the addition of the Director to its mailing list should be made.”

Hoover’s passion for rooting out subversives in the civil-rights movement, on the other hand, burned bright throughout his career, sustained by the racial ideology he’d assimilated as a young man. For most of his tenure, Hoover resisted hiring Black people as anything other than chauffeurs and greeters. Through a fluke of federal bureaucracy, his hiring practices were not subject to the same civil-service regulations as those of other agencies. He took full advantage of this loophole to recruit preferentially from George Washington and Kappa Alpha well into the nineteen-forties, with predictably homogeneous results. (There were also some weird, pseudo-phrenological specifications: an F.B.I. memo taken in the 1971 burglary proscribed the hiring of men with “pear-shaped heads.”)

Under varying degrees of pressure from Roosevelt, Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson, Hoover’s F.B.I. did investigate racially motivated murders in the South. A tipoff to the F.B.I., in fact, finally led investigators to the bodies of three civil-rights workers murdered during the Freedom Summer, in 1964, and buried deep in an earthen dam in rural Mississippi, where they would surely have otherwise remained. In the mid-sixties, the F.B.I. even had a COINTELPRO unit dedicated to infiltrating the Ku Klux Klan, and Hoover was frustrated by the intransigence of white Southern juries who wouldn’t return guilty verdicts for suspects the F.B.I. had helped track down; for one thing, it made the Bureau look ineffective. But Hoover’s heart was just never in the harassment of white supremacists the way it was in the hounding of Black leftists. For the most part, he resisted calls for F.B.I. agents to protect civil-rights demonstrators, and he refused to inform King of credible death threats. Lyndon Johnson had to beg him to make an exception and send a detail to Jackson, Mississippi, to watch over King for a few days in the summer of 1964.

The relationship between L.B.J. and Hoover was a push and pull out of which emerged some assurance, for a time, of King’s safety, landmark civil-rights legislation, and more leverage for Hoover. He liked L.B.J. a lot better than he’d liked the Kennedys, and he was willing to do him some favors. In 1964, when Hoover testified about the Bureau, as he did each year, before the House Appropriations Committee, he took the opportunity to go off the record and talk about King’s sexual escapades and his ties to former members of the Communist Party. Johnson’s aides worried that, once these scurrilous remarks entered the Capitol Hill gossip stream, the civil-rights bill they were working to pass would be imperilled. Hoover could have said more and said it more openly—no doubt he would have liked to—but doing so would have sabotaged Johnson while bringing the Bureau’s secret spying operation to light. He held off. The bill became law in early July. When Johnson signed it, he handed out pens to those who’d helped insure its passage, and one of them went to Hoover, who had done so only by staying quiet. “With Johnson’s prodding,” Gage writes, “Hoover showed that the F.B.I. was still capable of producing solid and professional work”—tracking down the whereabouts of the three murdered civil-rights workers, for instance.

But Johnson also involved Hoover in a shady side gig, for which he owed the director. L.B.J. feared that he would lose control of the 1964 Democratic Convention, in late August: there were rivals for the nomination, a Black protest delegation from Mississippi challenging the all-white official one, and white Southern Democrats on the rampage. Johnson wanted as smooth an ascension to the top of the ticket as possible, so he asked Hoover to have F.B.I. agents, supplemented by civil-rights-movement informants, keep tabs on the protesters and on anyone else poised to disrupt an all-the-way-with-L.B.J. spectacle. The agents did their job.

At times, Gage argues for Hoover as a tragic figure—a man who started out with a dedication to public service and certain narrow commitments to doing things expertly and aboveboard, but who allowed his idealistic professionalism to wane and his mission to be corrupted. Yet much that she writes about cuts against that interpretation. Hoover may indeed have been dedicated to government work and its possibilities (an orientation that we do not, as Gage says, associate with contemporary conservatism). From the Palmer Raids to COINTELPRO, however, he was never able to understand campaigns to expand social or racial or gender equality as anything other than criminal conspiracies, ginned up by foreign agents and their dupes. As a result, Gage concludes, “Hoover did as much as any individual in government to contain and cripple movements seeking social justice, and thus to limit the forms of democracy and governance that might have been possible.” That is a devastating assessment.

Hoover’s reputation may have suffered, but in one crucial respect he still holds the upper hand. In 2027, the recordings that the Bureau made in King’s hotel rooms will be released to the public. We’ll all have the chance to listen to and judge them. In Hoover’s office at the time of his own death was a set of files containing letters and other papers that concerned his private life. According to congressional investigators, the files included Bureau documents as well. Hoover had given orders to his long-serving secretary, Helen Gandy, to destroy them when the time came. On the day he died, Gandy began to do so. It took her two months to tear up each paper and then make sure they were all shredded or incinerated. Hoover knew how to keep his own secrets. He is keeping some of them still.

READ MORE "Doug Mastriano was defeated in his bid for Pennsylvania governor." (photo: Mike Segar/Reuters)

"Doug Mastriano was defeated in his bid for Pennsylvania governor." (photo: Mike Segar/Reuters)

Relief as Republicans election deniers running to take over elections beaten in almost every statewide race

Voters rejected election deniers who sought to become the top election official in Arizona, Nevada and Michigan – all key battleground states – as well as Minnesota and New Mexico. In Pennsylvania, Doug Mastriano, a state senator who has been among the most prominent spreaders of election misinformation, lost his bid to be the state’s top election official. Kari Lake, a Republican who built her campaign around election denialism, also is projected to lose her bid for governor in Arizona.

“We see the voters clearly saying trying to delegitimize democracy is not a winning strategy,” said Jocelyn Benson, a Democrat who defeated Kristina Karamo, a Republican who spread baseless misinformation about the 2020 election results, to win a second term last week. “But we still have a presidential election now under two years away in which we anticipate a lot of the same challenges.”

In Michigan, Democrats defeated election deniers in the governor and attorney general’s race as well, beating back what many feared could be an election denialism trifecta in a key battleground state.

In 94 statewide races this fall, just five non-incumbent election deniers won their elections as of Monday afternoon, according to States United Action, a group that has been tracking election deniers running. Those candidates won in Alabama, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas and Wyoming.

Several of the candidates who lost were members of the America First Secretary of State Coalition, which is led by Jim Marchant, a former Nevada lawmaker who lost his bid on Tuesday to be secretary of state. Just one member of the coalition, Diego Morales, won his bid to be secretary of state in Indiana, which is solidly Republican.

“The voters have spoken. And they spoke to something that is much deeper than the passing fad of the big lie or any other election denialism that a variety of politicians have sort of cooked up for their own, or what they perceive to be their own benefit,” said Adrian Fontes, a Democrat who is projected to beat Republican Mark Finchem, who tried to overturn the 2020 election, in Arizona’s secretary of state race.

“The American people are not gonna be swayed, regardless of their political leanings.”

The sweeping defeats came in an election cycle when there was increased attention to secretary-of-state races, long overlooked as inconsequential downballot contests, because of the enormous power the office has over how votes are cast and counted. There was deep concern that, if elected, election deniers could use the positions to undermine and potentially try and overturn the results of future elections, including the presidential contest in 2024.

“This was a threat we’d never faced before in this country. We’d never faced a threat of secretaries of state refusing to certify a result that they didn’t like. We can now say with certainty that this movement was rejected by the American people in this election,” said Trey Grayson III, a Republican who served as Kentucky’s top election official from 2004 to 2011.

“In every swing state those deniers lost elections, as well as in many other races across the country. This was a clear message that Americans believe in free and fair elections.”

In separate interviews, several Democrats who won their races shared a similar roadmap for beating back election denialism. First, they committed to telling the truth about the 2020 elections and the lack of voter fraud, betting that voters would reward them for defending the integrity of US elections.

In Michigan, Benson said a strategy was “really hammering that the choice isn’t a partisan one, but it’s one between truth versus lies. And chaos versus clarity. And that the battle is really over whether the voters will have a voice and a vote in future elections. And that impacts everything else.”

That strategy worked for Jeff Zapor, a 46-year-old counselor in South Lyon, a Detroit suburb, who voted for Benson last week. He said the secretary of state race was the most important contest on the ballot. “When you’re running on a platform of complete abject falsehoods, to me, that shows a complete lack of character. And you’re running for the exact wrong reason,” he said after he voted.

Steve Simon, Minnesota’s secretary of state, said focusing on the truth about elections was not a matter of instantly getting voters to change their minds, but rather chipping away at moving them towards convincing them they can trust the election results.

“I’m not naive and most people aren’t. I’m not saying that just by saying the truth in the face of disinformation that it will just wither and shrivel and go away,” said Simon, who defeated Kim Crockett, a Republican who said the election was “rigged”.

“Not everyone has to make a 180 [turn]. They might do a 12. They might do a 27. They might do a 38. And that’s worth something. It’s not a light switch. It’s not this choice between believing or not believing.

“But if you can, over time, say what the truth is enough so that people start to weigh that as they’re processing those other arguments.”

The winning candidates also said they focused on making threats to democracy less abstract, focusing instead on concrete issues voters care about.

“When I called my mom and said, ‘We’re gonna save democracy,’ she was like: what does that mean?” said Cisco Aguilar, a Nevada Democrat who defeated Marchant in the Nevada secretary of state’s race. “In the very beginning we had to educate the voter about the importance of the secretary of state’s race. How the secretary of state provided access to the ballot box to the kitchen table issues that the voter cared about.”

“Talking in the abstract about democracy being under attack, while that’s real and I’ve certainly done that over the last few years and will continue to do so, we really also need to talk in the specifics about what that actually means,” Benson said.

“What it means to empower folks who have been lying to voters as opposed to holding them accountable and rejecting them.”

Democrats running against election deniers also benefitted from bipartisan support, according to a post-election memo from DemocracyFirst, a Pac focused on defeating election deniers (Adam Kinzinger and Liz Cheney, two Republicans who have been vocal about threats to democracy backed Democrats running against election deniers. And they were buoyed by a flood of money in their election bids, outraising election deniers by a three-to-one margin, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. Democratic-aligned outside groups, including iVote and the Democratic Association of Secretaries of State, spent millions of dollars, unprecedented money in a secretary of state’s race, that was unmatched by election deniers, the Brennan Center noted.

“It appears that election denial was a stronger asset to fundraising in the primary season than it has been in the general. Candidate strategy may have played a role in this,” Ian Vandewalker and Maya Kornberg of the Brennan Center wrote in their analysis tracking candidate spending.

They noted that Finchem and Marchant stopped running online advertisements after their primaries (Finchem started running them again in October).

Despite those victories, the threat of election denialism is unlikely to disappear from American politics any time soon. More than 170 of the 291 election deniers who ran for Congress or in statewide elections this year were elected, according to a Washington Post tally.

Trump, who has made the myth of a stolen election central to his post-presidency, is expected to launch a 2024 presidential bid for the White House on Tuesday.

“While 2022 was indeed for the voters, for democracy, we are really just in the halfway point of what is a multi-year, multi-faceted effort to delegitimize democracy in our country,” Benson said.

“We are just two-thirds of the way in,” she said. “Act II ended with a win for democracy just as Act I did. But we now have Act III, the 2024 presidential election.”

READ MORE "Firefighters work to put out a fire in a residential building hit by a Russian missile strike in Kyiv on Tuesday." (photo: Gleb Garanich/Reuters)

"Firefighters work to put out a fire in a residential building hit by a Russian missile strike in Kyiv on Tuesday." (photo: Gleb Garanich/Reuters)

President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said the Russian barrage included 85 missiles in the space of a couple hours on Tuesday afternoon and evening.

"Does anyone seriously think that the Kremlin really wants peace?" Zelenskyy's top adviser, Andriy Yermak, said on Twitter. "It wants obedience. But at the end of the day, terrorists always lose."

The attacks come a day after the United Nations General Assembly approved a resolution saying Russia should be held accountable for the war it's waging in Ukraine, and should be required to pay reparations. And just last Friday, Russia suffered a major military setback as it was forced to retreat from the strategically important southern city of Kherson.

Ukraine shot down some of the incoming missiles, but others reached their targets in the capital Kyiv, the northeastern city Kharkiv, the western city of Lviv, and the southern city of Odesa, among others.

In Kyiv, at least two residential buildings were hit and at least one person was killed, according to Mayor Vitali Klitschko.

Video posted by the mayor's office showed one apartment building in Kyiv engulfed in heavy flames and thick smoke.

Half of Kyiv loses power

The mayor also said about half of the capital was without power.

The northeastern city of Kharkiv was without power, according to officials there.

"The United States strongly condemns Russia's latest missile attacks against Ukraine," said U.S. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan, who was attending the G20 summit in Bali, Indonesia.

"The United States and our allies and partners will continue to provide Ukraine with what it needs to defend itself, including air defense systems. We will stand with Ukraine for as long as it takes," Sullivan said.

Earlier Tuesday, Zelenskyy spoke to the G20 by video, saying his country is determined to recover all of its territory taken by Russia.

"In order to free our entire land, we will have to fight for a while longer," Zelenskyy said.

There are some international calls for peace talks to end war in Ukraine. But Zelenskyy noted that the two countries reached interim agreements after Russia first invaded in 2014.

Russia used this period of relative calm to regroup militarily, he said, adding that Ukraine would not fall for this again.

We will not allow Russia to wait us out and build up its forces," said Zelenskyy.

In his speech, the president repeatedly called the G20 the 'G19,' saying Russia should be excluded.

Russia turns to air power

With Russia's ground forces unable to make much headway in recent months, and being significantly pushed back in many instances, Russia is increasingly relying on airstrikes.

Russia launched a heavy bombing campaign against Ukraine's energy systems in October, damaging around 40% of the country's electricity system, according to Ukrainian officials.

Ukrainian workers have scrambled to repair the damaged power grid. However, many parts of the country, including the capital, were suffering power outages for hours every day, even before the latest attack.

The Russian airstrikes come as temperatures are rapidly falling and a long, cold winter looms.

Ukraine's limited air defenses have proven more effective than expected in protecting key government and military facilities.

However, the recent Russian campaign has targeted such a wide range of civilian and energy facilities that Ukraine has been unable to protect them all.

READ MORE Donald Trump in Wisconsin, April 4, 2016. (photo: Scott Olson/Getty)

Donald Trump in Wisconsin, April 4, 2016. (photo: Scott Olson/Getty)

Seven years ago, the New York businessman entered the political fray on defense, working vigorously to cast himself as a serious contender for the Republican presidential nomination to the incredulity of veteran political operatives and his primary opponents. This time, Trump takes the plunge as the party’s indisputable frontrunner, but once again, he finds himself in a defensive crouch.

On the brink of a campaign launch that elicits both enthusiasm and dread from different corners of his own party, Trump’s quest to return to the Oval Office could face untold obstacles in the months to come, even with his loyal base firmly intact. He has spent the days since the midterm elections fending off criticism from fellow Republicans over his ill-fated involvement in key contests, furiously lashing out at two GOP heavyweights who could complicate his path to the White House if they mount their own presidential campaigns, and fretting that he or associates could soon be indicted by federal investigators in two separate Justice Department probes.

Aides say Trump is hoping his early entry into the 2024 presidential primary will reframe the conversation away from Republican failures and inject a fresh dose of enthusiasm into a demoralized party amid GOP failures to capture Senate control and win a sizable House majority. Though the former president has been touting his 200-plus victories on Election Night, many of the Trump-endorsed Republicans who prevailed last Tuesday ran uncontested or were widely expected to win their contests, while several Senate candidates he endorsed in highly prized races failed to dethrone their Democratic opponents or flip open seats into the GOP’s column.

Mehmet Oz, Adam Laxalt and Blake Masters, three Republican Senate candidates who earned Trump’s support in their primaries, respectively lost to Democratic opponents in Pennsylvania, Nevada and Arizona. Meanwhile, Herschel Walker, a longtime Trump friend challenging Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock, is headed to a December runoff after both failed to reach 50% support in Georgia.

On Saturday, CNN projected that Democrats will retain control of the Senate in the 118th Congress, an outcome that has fractured Republicans and left the party on tenterhooks as Trump readies his “big announcement.”

Next targets

Trump, who in the immediate aftermath of the midterms conceded that his party had suffered a “somewhat disappointing” outcome, has already moved on, settings his sights on winning a second term in Washington and attacking two GOP governors who could challenge his status as the party’s anchor in the months to come, Ron DeSantis of Florida and Glenn Youngkin of Virginia.

“I Endorsed him, did a very big Trump Rally for him telephonically, got MAGA to Vote for him – or he couldn’t have come close to winning,” Trump said of Youngkin in a Truth Social post last week.

Three sources familiar with the matter said the former president believed Youngkin was supportive of comments his lieutenant governor, Winsome Earle-Sears, made during a Fox Business appearance last week. She told the network she would not support Trump if he runs for president a third time.

Responding to repeated questions about Trump’s impending 2024 announcement, Earle-Sears said, “A true leader understands when they have become a liability. A true leader understands that it’s time to step off the stage, and the voters have given us that very clear message.”

Sears later declined to tell The Washington Post whether Youngkin knew prior to the interview that she planned to split from Trump, a detail that caught the former president’s attention, according to one of his aides.

“If Glenn Youngkin decides to run for president, that’s his choice. But Team Trump will certainly mount a massive effort to win the Virginia delegates going to Milwaukee that is going to embarrass Youngkin,” said John Fredericks, a Virginia-based conservative radio host who chaired Trump’s campaigns in the state in 2016 and 2020.

The former president’s criticism of Youngkin, whose 2021 gubernatorial bid he endorsed against former Democratic governor Terry McAuliffe, came on the heels of a spate of insults Trump launched against DeSantis, the popular Florida governor who has refused to rule out a 2024 campaign against the former president and increasingly appears to be laying the groundwork for one. In the span of one week, Trump went from introducing a disparaging new nickname for the Florida governor (“DeSanctimonious”) to heeding requests from Republicans to pare back his criticism of DeSantis in the home stretch before Election Day, to blasting out a scathing statement on the heels of DeSantis’ reelection, calling him “an average Republican governor.”

DeSantis allies said they do not expect the Florida governor to engage at all with Trump’s bashing for as long as he can avoid it. In two press conferences related to Hurricane Nicole that DeSantis held after winning reelection by a 19-point margin, he did not mention the overall midterm results or take any questions. Notably, he has also avoided taking a victory lap on Fox News, which would undoubtedly inquire about Trump and 2024, after appearing frequently on the network while campaigning for reelection.

“Trump rants for a couple of months. DeSantis throws some red meat during [Florida’s next legislative session] and then we have a primary around May,” said one DeSantis ally, describing his current posture

Asked how long the governor can go without acknowledging Trump’s attacks, a second DeSantis ally responded simply, “A long time.”

Trump’s bitter criticism of Youngkin and DeSantis, two rising Republican celebrities, was a stark reminder of the scathing brand of politics he brings to the campaign trail, without regard for how it might impact his own party. His first use of “DeSanctimonious” came just days before the Florida governor appeared on the ballot in his bid for reelection. And much to the chagrin of top Republicans, including some of Trump’s closest allies on Capitol Hill, his Tuesday announcement comes as the party looks to prevent Senate Democrats from securing a 51-seat majority through the Georgia runoff.

“I know there’s a lot of criticism and people saying, ‘Just focus on Georgia,’ but he figures there’s no point in waiting. If Herschel loses, he’ll be blamed for distracting from the runoff but if he wins, he doesn’t believe he will get any credit for energizing the base,” said a current Trump adviser.

Some of Trump’s closest allies said Republicans should brace for a significant escalation in his attacks on rumored GOP challengers once he is a declared presidential contender, meaning he could ramp up his criticism of DeSantis, Youngkin or others while the party is fighting for Walker’s survival in Georgia.

“Nobody should be surprised. This is how Trump does primaries,” said Michael Caputo, a former Trump administration official who remains close to the former president. “The question you have to ask is whether this format can work for him again.”

Of course, Trump has not been in a hotly contested primary since 2016, when he unleashed broadsides against more than a dozen-plus opponents with fury and vitriol that shocked some Republican observers but delighted a segment of the Republican primary electorate that would later evolve into his loyal base. Few Trump allies expect him to behave any differently in the months to come. Even if he remains the only declared candidate until others enter the fray next year, he will continue his preemptive blitz against perceived challengers.

“Donald Trump will make sure every Republican candidate is well-vetted,” said a senior Trump aide.

“No one’s going to get a free pass. It’s going to be brutal,” added the Trump adviser.

Other obstacles

The likelihood that Trump will face primary challengers may be the least of his concerns at this juncture.

While the former president maintains significant support from grassroots Republicans, some of the party’s largest donors have been meeting with other potential presidential hopefuls and signaling they may be interested in bankrolling alternative candidates. It’s a concern Trump allies are confronting head on as they privately explore ways to make the monstrous pile of cash he has raised since leaving office available to him as a presidential candidate. Billionaire Ken Griffin, who gave nearly $60 million to federal Republican candidates and campaigns in the 2022 cycle, told Politico in an interview last week that he would support DeSantis if the Florida governor tosses his hat into the ring for the 2024 GOP nod. Two other Republican donors who gave to Trump in 2016 and 2020 and requested anonymity for fear of retribution told CNN that they, too, were waiting to see what DeSantis decides to do, while one of them said they would also be willing to support former Vice President Mike Pence should he challenge his former boss.

“One of our biggest challenges will be the fundraising component but I do think [Trump] has proved that he doesn’t need deep-pocketed donors, per se,” said a person close to Trump, noting the enduring strength of his small-dollar operation.

Trump will also have to convince Republicans that he would be an asset at the top of the ballot in 2024 as opposed to an albatross for vulnerable candidates in tight races. That task comes amid a fraught intraparty debate over the GOP’s bruising midterm outcome, with some Republicans claiming Trump’s involvement – including an eleventh-hour 2024 campaign tease at a rally on the eve of Election Day – did more to hurt the party than help. Others have blamed party leaders for failing to articulate clear policy priorities, pointed to the party’s money gap against Democrats in key races, or lamented the bickering that unfolded all cycle between two of the party’s biggest campaign committees led by Florida Sen. Rick Scott and allies of Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell.

Some Trump allies said the donor challenges, midterm outcome and questions about his stature has left a dearth of seasoned campaign operatives willing to join his next campaign. Though the president has told allies he wants to keep his operation lean, much like his 2016 presidential campaign, some have privately questioned whether it’s out of preference or due to recruitment troubles. CNN has previously reported that Trump’s likely campaign is expected to be helmed by three current advisers – Susie Wiles, Chris LaCivita and Brian Jack – with assistance from a group of additional aides and advisers with whom the former president is already familiar. Overall, his 2024 apparatus is expected to dwarf in comparison to his reelection campaign two years ago, multiple sources said.

Either way, as Trump works to find his footing on the verge of a presidential campaign that could coast to the party’s nominating convention or encounter any number of unforeseen troubles, allies who have stuck by his side said they are ready for battle one last time.

“Our team is accustomed to fighting tooth and nail. Team Trump is going to fight for the nomination,” said Fredericks.

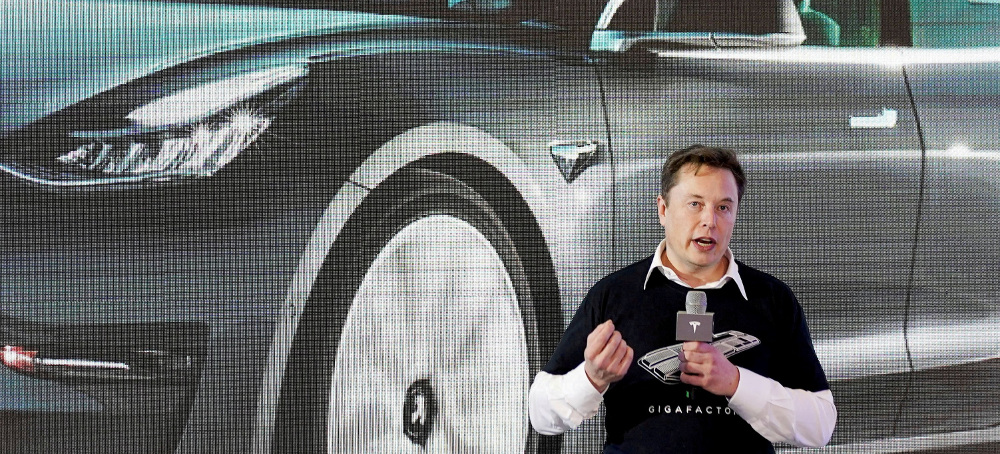

READ MORE "As Elon Musk will take the stand to defend his $56 billion compensation package as CEO of Tesla, a manslaughter trial is set to begin in LA for a fatal crash caused by a Tesla owner operating Autopilot." (photo: Aly Song/Reuters)

"As Elon Musk will take the stand to defend his $56 billion compensation package as CEO of Tesla, a manslaughter trial is set to begin in LA for a fatal crash caused by a Tesla owner operating Autopilot." (photo: Aly Song/Reuters)

Elon Musk will take the stand to defend his $56 billion compensation package as CEO of Tesla. At the same time, a manslaughter trial is set to begin in LA for a fatal crash caused by a Tesla owner operating Autopilot.

And that’s not all! On Tuesday in Los Angeles, a Tesla Model S owner is on trial for manslaughter in a case that experts are calling it a first-of-its-kind legal test of the responsibility of a human driver in a car with advanced driver-assist technology like Tesla’s Autopilot.

Taken together, the twin trials represent a critical test for Musk’s multitasking skills

Taken together, the twin trials represent a critical test for Musk’s multitasking skills. He’ll take the stand in one trial, and while Tesla isn’t facing charges in the manslaughter case, the company’s top deputies are sure to be tracking its developments. Musk’s acquisition of Twitter has already done much to diminish both his wealth and his personal brand. Depending on the outcomes of these cases, the reputation of his primary revenue-generating company — Tesla — could also be eroded.

The $56 billion question

Let’s go over what’s at stake with both these cases, starting with the trial over Musk’s compensation at Tesla.

Musk was able to avoid a trial in Delaware’s Court of Chancery when he finally agreed to acquire Twitter at his original price of $44 billion. But the controversial CEO will still find himself taking the stand in the Wilmington-based court for a different case examining the compensation plan that Tesla’s board of directors created for Musk in 2018.

The plan, which was approved by Tesla shareholders, hinged on the company hitting certain milestones in the next 10 years, including an at-the-time astronomical-seeming market valuation of $650 billion — an amount that was more than 10 times the company’s 2018 value of around $59 billion. Shareholders approved a total of 12 tranches that Musk must surpass before vesting the full amount.

The CEO is expected to earn the final batch early next year, allowing him to collect an estimated $56 billion

In 2021, Tesla’s valuation briefly hit $1 trillion after Hertz announced it was purchasing 100,000 of the company’s vehicles to bulk up the rental car company’s fleet. And when Tesla reported its first quarter 2022 earnings, the company surpassed benchmarks that triggered the vesting of the ninth through 11th of 12 tranches of options granted to Musk. The CEO is expected to earn the final batch early next year, allowing him to collect an estimated $56 billion, the largest compensation awarded to anyone on Earth from a publicly traded company.

The trial will focus on whether the compensation package requires Musk to work full-time at Tesla. In addition to overseeing Tesla, he is also helping run SpaceX, The Boring Company, and Neuralink. And then, of course, there’s Twitter.

Fun fact: the case will be decided by Chancellor Kathaleen McCormick of Delaware’s Court of Chancery. That’s the same Kathaleen McCormick who oversaw the legal dispute between Twitter and Musk that ended with his purchase of the social media platform last month.

Fun fact: the case will be decided by Chancellor Kathaleen McCormick of Delaware’s Court of Chancery

Legal experts told Reuters that corporate boards generally have wide latitude to set executive pay. Tesla’s directors have argued that the compensation package did what it was intended to do — ensure that Musk guided the company through difficult financial waters to achieve a record-setting valuation.

The shareholder who filed the suit alleges that the board lacked independence from Musk when approving the compensation plan. The board included Musk’s brother Kimbal, as well as friends Antonio Gracias and Steve Jurvetson. (Jurvetson and Gracias have since left Tesla’s board.)

Man vs. machine

While Musk takes the stand to testify about his pay, a separate trial focused on Tesla’s driver-assist technology will be taking place in Los Angeles. It is a possible test case for whether the technology has advanced faster than legal standards.

Limo driver Kevin George Aziz Riad, 27, is on trial for manslaughter after running through a red light in his black Tesla Model S, slamming into a Honda Civic and killing two people. The LA County District Attorney does not mention Autopilot in its charges against Riad, but the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration confirmed that the driver-assist feature was active at the time of the incident. The agency plans on publishing its findings from the investigation soon.

It is a possible test case for whether the technology has advanced faster than legal standards

Autopilot, which can control steering and braking functions, as well as perform automatic lane changes while on certain highways, has come under increased scrutiny from federal regulators.

Last year, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration opened an investigation into over a dozen incidents involving Tesla vehicles using Autopilot that have crashed into stationary emergency vehicles. Autopilot has contributed to a number of fatal crashes in the past, and the families of deceased drivers have sued Tesla for wrongful death. And last month, it was reported that the Department of Justice is probing dozens of Tesla Autopilot crashes, some of which were fatal.

Legal experts speculate that prosecutors will have a hard time proving the guilt of the human driver when at least some of the tasks are controlled by Autopilot. Notably, Tesla does not face charges in the case. On its website, Tesla says that its driver-assistance systems ”require active driver supervision and do not make the vehicle autonomous.”

Numerous Tesla drivers have been caught misusing Autopilot, and some have even publicized the results themselves. Drivers have been found sleeping in the passenger seat or backseat of their vehicles while speeding down crowded highways. A Canadian man was charged with reckless driving after being pulled over for sleeping while traveling at speeds of 93mph in a Tesla. A class action lawsuit was filed in San Francisco recently alleging that Tesla’s marketing of Autopilot and its Full Self-Driving feature is deceptive and misleading.

Numerous Tesla drivers have been caught misusing Autopilot

Some safety experts have argued that driver-assist technology like Autopilot encourages drivers to be less attentive. Musk has claimed that Tesla’s Autopilot could save half a million lives if universally deployed. Meanwhile, the US Department of Transportation recently began collecting data about ADAS-related crashes, but it’s too soon to draw many insights.

Riad’s lawyers are likely to point to the Justice Department investigation, as well as the class action lawsuit, as evidence that their client is not solely responsible for the fatal crash. Whatever the outcome, Tesla’s reputation as a hard-charging automaker that’s too comfortable with risk is likely to come under increased scrutiny.

“It should not be assumed that Riad was blindly relying on Autopilot, simply because he was driving a Tesla,” criminal defense attorney Cody Warner, who specializes in autonomous vehicles, wrote in Law360. “But it’s hard to escape the conclusion that Tesla’s recent reputation for moving quickly and breaking things — even at the expense of public safety — has been imputed to Riad.”

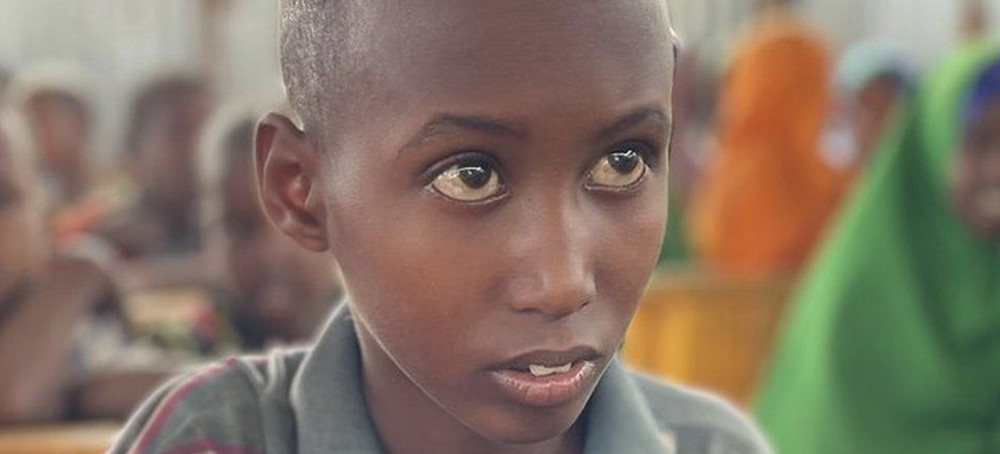

READ MORE "Dahir had previously told the BBC he just wants to 'survive' the drought in Somalia." (photo: Ed Habershon/BBC)

"Dahir had previously told the BBC he just wants to 'survive' the drought in Somalia." (photo: Ed Habershon/BBC)

The school's sole teacher, Abdullah Ahmed, 29, writes English days of the week on the blackboard, as Dahir, and perhaps 50 classmates, recite: "Saturday, Sunday, Monday...".

For a few minutes, a burst of interest energises the children, but soon the yawns and coughs resume - signs of the hunger and sickness that echo, like a grim soundtrack, across the plateau of rocky ground around Baidoa that has become home in recent months for hundreds of thousands of civilians, displaced by the worst drought to hit Somalia for 40 years.

"I think at least 30 of these children have not had breakfast. Sometimes they come to me to tell me of their hunger," says Mr Ahmed. "They struggle to concentrate, or even to come to class."

Six weeks ago, on our last visit to this part of southern Somalia, Dahir sat, weeping, beside his mother Fatuma, outside the family's flimsy home-made hut.

A few days earlier, his younger brother, Salat, had starved to death on the journey into Baidoa from the drought-parched countryside.

Salat was buried a few metres away. Now the grave is surrounded by huts built by newer arrivals.

"I'm worried about my sisters. I wash for them. I wash their faces too," says Dahir, glancing across at six-year-old Mariam, who coughed hoarsely and complained of a headache, and then at four-year-old Malyun, sitting lethargically and with sunken eyes on her mother's knee.

"She is warm. I think she has measles. They may both have measles," says Fatuma, putting her hand to Malyun's forehead.

Measles and pneumonia have swept through Baidoa in recent months, killing many younger children whose immune systems have been weakened by malnutrition.

At the provincial hospital in the centre of Baidoa, doctors and nurses move between beds in the intensive care ward, inserting fluid drips into emaciated infants' arms, and oxygen tubes into tiny nostrils.

Several children's limbs are dark and blistered - as if from severe burns - one painful reaction to prolonged starvation.

"We have received some more [aid] supplies. But still not enough," says Abdullahi Yusuf, the hospital's head doctor.

"The world is paying attention to Somalia's drought now. We see visitors from international donors. But that doesn't mean we are getting enough support. I hope it will come soon. It is a desperate situation."

Six weeks ago, he described the situation as "terrifying." Today he acknowledges a slight drop in admission numbers but explains that was probably due to a few days of rain which had disrupted some dirt roads and prompted some families to focus on trying to plant crops rather than bringing sick children to hospital.

The situation is 'getting worse'

Back at the camp, Fatuma lugs a plastic jerrycan of water home from a communal tap. Dahir emerges from the hut to help her clean a battered metal bowl while her ailing daughters lie, wearily inside the hut.

"My boy is a big help. He does so much to help the girls," says Fatuma.

While she boils water, her phone rings. Her husband, 60-year-old Adan Nur, is calling from their home in a village three days' walk away, in territory controlled by Islamist militant group al-Shabab.

"He says he's planted sorghum. He's okay. He will return soon. But we have lost all our livestock. There is no way we can make a living from just the crops, so I will stay here. That way of life is over," says Fatuma after the call is over.

Her decision is backed up by the views of many experts, who warn that this rainy season appears to be failing, just like the last four - spreading a blush of green across the wilderness outside Baidoa but making no real impact on the crisis.

"It's still getting worse. A lot of people are still coming here to seek food, safety, and water. And many children are dying of malnutrition. We urge [the government and international community] to consider the situation… as a famine," says Baidoa's Mayor Abdullah Watiin, stepping briefly out of a community meeting in a heavily guarded compound.

Inside the hall, an army general warns local people about the growing threat from al-Shabab, telling them to be on the look-out for explosive devices and ambushes.

Somali government troops and militias are expected to widen an offensive that appears to have been met with some success further north, but that risks making it even harder to access some rural communities hit hardest by the drought.

Later in the day, Fatuma settles her two sickest children - Mariam and four-year-old Malyun - on a blanket on the dirt floor of their hut.

An offer to take the children to hospital was rejected in favour of a course of traditional herbal remedies. Then Fatuma, weary too, lies down beside the girls.

"I just want them to get better," says Dahir, watching from his own small blanket, then solemnly repeating the phrase two more times.

READ MORE "Cows seek shelter under a lone tree in a deforested region of the Amazon. Marabá, Para state, Brazil." (photo: Ricardo Lima/Getty)

"Cows seek shelter under a lone tree in a deforested region of the Amazon. Marabá, Para state, Brazil." (photo: Ricardo Lima/Getty)

As world leaders return home from COP 27 and prepare for other meetings they must listen to native peoples and the plans they bring to the table to quell extraction from the Amazon

The Amazon River feeds a tropical forest of 2.86 million square miles, which is nearly the size of the land area of the contiguous U.S. This greenery covers about 5 percent of Earth’s land surface and critically modulates the global climate system. In addition, the Amazon is an unparalleled hotspot of biodiversity. It is home to about one third of all known terrestrial species of plants, animals, and insects, 10 percent of all biomass on the planet and 20 percent of the world's fresh water. Most importantly, there are more than 500 distinct indigenous peoples in the Amazon rainforest. The Amazon is the lifeblood of a complex web of interconnected ecological systems.

But this system is in danger of collapse, and the politicians and public officials in Amazon countries and beyond have done little to help.

Businesses that extract natural resources and commodities that have great value in the international market, such as oil, timber, minerals, agriculture and livestock, are destroying the land and water in the Amazon. According to the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP) the Amazon will reach a point where restoration will be impossible in the next 30 years. Contrary to what many people think, protecting the Amazon is not a local issue for the nine countries that make up the Amazon region; it is, and should be recognized as, a global priority issue that affects us all.

It is imperative that governments, businesses, civil society and international organizations support Indigenous peoples in the urgent restoration of ecosystems. We believe that despite the Global North’s responsibility in causing this unparalleled catastrophe, it is Indigenous people in the Amazon basin who will lead the most lasting and bold solutions to the current crisis.

In Ecuador and Peru, Indigenous groups, including the Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Rainforest (AIDESEP), the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon (CONFENIAE) and Coordinator of the Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon Basin (COICA) have organized in defense of their Pachamama, as they call Mother Nature. This alliance is called the Amazon Sacred Headwaters Initiative, and it covers 86 million acres bioregion and is home to more than 600,000 people from 30 Indigenous nationalities.

This alliance is unique, because it is an initiative of Indigenous organizations, led by Indigenous people (27 of 29 members of the governing board are representatives of Indigenous organizations), and it is one of the largest standing forest conservation programs in the world, with a socioecological transition plan that has both territory- and global-level actions.

The main vehicle to achieve the alliance’s goals is the Bioregional Plan 2030, developed over four years with support from leading elders, known as “sábios,” from the Amazonian communities, and world-class international scientists. The plan describes nine transition pathways, such as community-based renewable energy systems and regenerative entrepreneurship, that in turn create social and economic benefits that prioritize protecting nature and the people who live in the Amazon region. The plan will demonstrate that another vision of development is possible, one that doesn’t violate human rights or ecosystems. It will consolidate Amazonian well-being, ensure Indigenous self-determination and territorial governance, and stop the advance of extractive industries. The plan blends both the ancient knowledge of Indigenous peoples and the most rigorous of modern science, to create, for the first time, a comprehensive document on how to fix this crisis.

The ancestral knowledge associated with the relationship of the Amazonian peoples with their territories and forests is also in danger. These Indigenous peoples are ancestral to the Amazon, and the companies and governments that support extraction regardless of environmental or human cost are destroying and displacing the native groups, mostly during the last 50 years. This is in addition to the lost species of plants and animals, many of which are rare and exist nowhere else on earth. The loss of these species means the loss of genetic information that could teach us about evolution, disease, immunity and adaptation to changes in environment, such as climate change. Beyond this, many studies have proven the linkage between biodiversity loss and new diseases, such as zoonotic diseases worldwide, which led to the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically in the Amazon, there is a study that shows the impacts of diversity loss and climate change on infectious diseases and public health.

Luckily, the Amazon Sacred Headwaters Initiative is not the only collaborative effort to restore the Amazon basin. The Science Panel for the Amazon, composed of over 240 scientists, is the first high-level science initiative dedicated to the Amazon. The panel was established to make clear the scientific, economic and moral case for conservation and to address widespread deforestation, forest degradation and wildfires that have intensified in recent years. Its 2021 Amazon Assessment Report, presented at COP 26, which has been called an “encyclopedia” of the Amazon region, is unprecedented for its scientific and geographic scope, its inclusion of Indigenous scientists, and its transparency, having undergone peer review and public consultation.

The situation is dire but not hopeless. There is no longer room for small actions; it is time for systemic transformations. A study by researchers at Princeton University and elsewhere concluded that deforestation of the Amazon results in up to 20 percent less rainfall in the U.S. Northwest. The hundreds of billions of trees in the Amazon biome have absorbed over a billion metric tons of CO2 per year, equal to about 4 percent of world fossil-fuel emissions. But recent studies suggest that deforestation and degradation are converting the Amazon from a net carbon sink to a carbon source. This is why we say the Amazon is the heart of the planet, because its destruction is not just a “regional” problem; the large range of the consequences make it a global problem.

This effort is a call to all humans, many of whom no longer trust the rhetoric of major global events, national governments, or traditional governance systems. Beyond the financial support that is undoubtedly necessary, this and other similar efforts are trying to avoid a path that will lead to destruction and death and promote a path that leads to regeneration. This path is where all living beings, Indigenous peoples and non-Indigenous, Amazonians and non-Amazonians, human beings and non–human beings alike, can live with dignity and in safety, while also avoiding climate collapse. We have to act boldly and faster. Why not start by protecting the heart of the planet?

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611