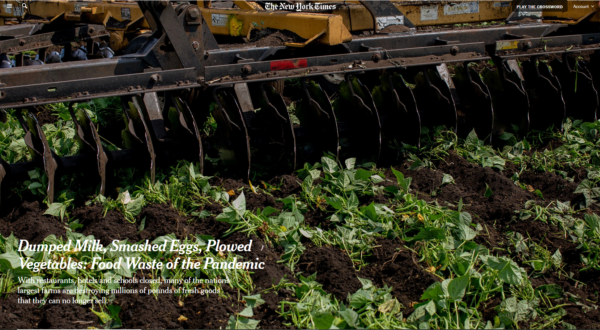

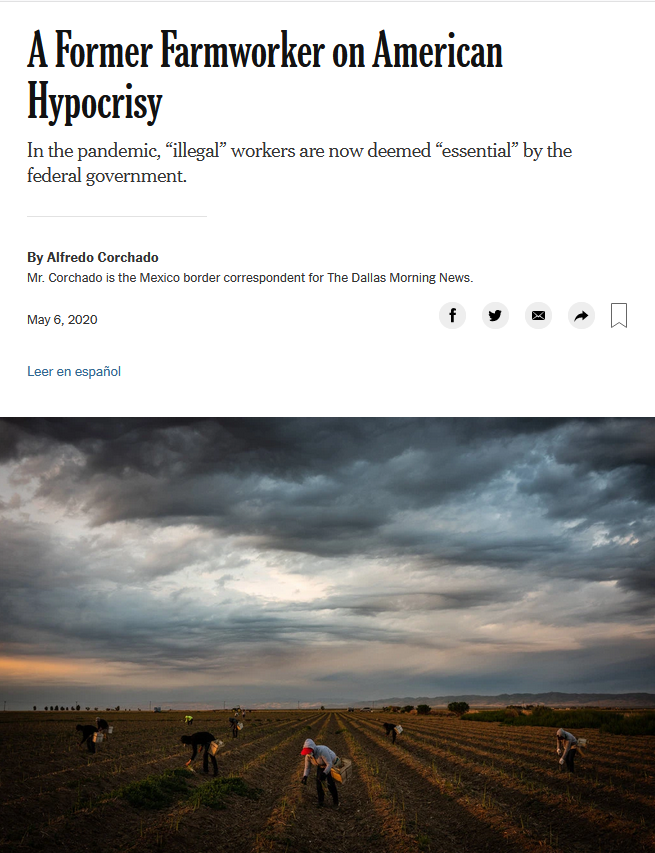

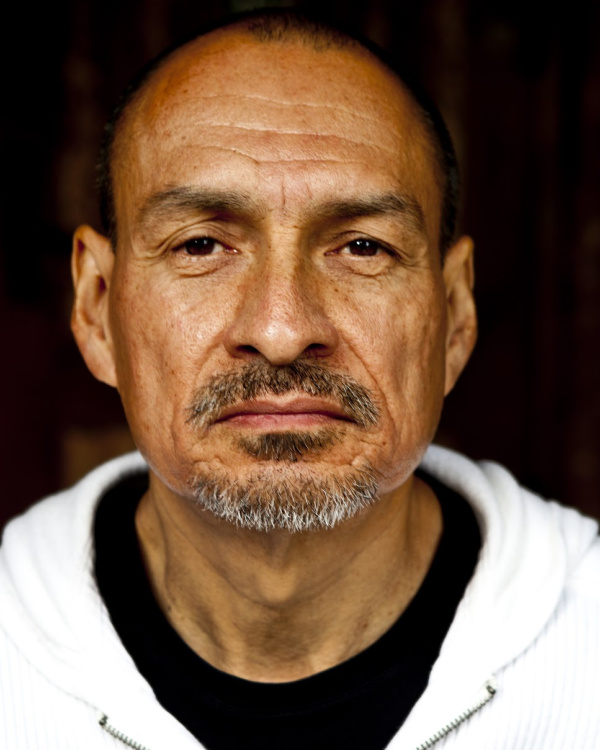

'Our Food System Is Very Much Modeled on Plantation Economics'Janine Jackson  Janine Jackson interviewed the Union of Concerned Scientists’ Ricardo Salvador about the coronavirus food crisis for the May 8, 2020, episode of CounterSpin. This is a lightly edited transcript. MP3 Link Janine Jackson: Listeners have likely seen the images: farmers dumping milk, smashing eggs, plowing produce under. At the same time, in the same country, people line up at food banks, unable to access or afford nutritious food. At the nexus of the health crisis and the economic crisis of Covid-19 is a food crisis. And it's along every dimension, from farm laborers to restaurant workers to hungry people. As with so many things, the pandemic didn't create the problems, but it's making them harder to deny. Ricardo Salvador is senior scientist and director of the Food and Environment Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists. He joins us now by phone. welcome to CounterSpin, Ricardo Salvador. Ricardo Salvador: Thank you very much. It's a pleasure to be here. JJ: If we could just talk, first, about the supply chain itself. What is it about the food system we have, that makes it a reasonable or necessary response to the crisis for some farmers to plow vegetables under that people could be eating? RS: It has to do with the structure of agriculture, and I think your question is very well-framed. It actually is a logical thing for most farmers to plow under their food, rather than try to deal with a food system that is very specialized, that operates at very large scale. It's very concentrated. And it operates along a few well-established channels. So it's important to understand what those channels are, to then understand why it's logical for farmers to do what is being reported, as well as to understand that this issue of food waste is a serious problem. And it is not exclusively on farmers. It's an issue of the structure of the system. So those channels I’m referring to have to do with the primary ways in which we all eat. Generalizing broadly: Prior to the pandemic, we all ate one of two ways. Either we went out someplace where somebody else took care of all the details; we don't have to worry about what's in season, how it's grown, how it's prepared; we just ask on a whim for whatever we're in the mood for, somebody prepares it, it’s delivered to us, somebody cleans up after us. And that system is supplied by a channel, a sector, in the food system, which is called food service. And it operates almost invisibly to the majority of us. But if you do see it, you see it in service entries and back alleys, with semi trailers delivering frozen food or packaged food in particular quantities that are suitable for the restaurant, cafeteria, the other institutions that deliver the food in the way that I described. And, by the way, we spend most of our money for food that comes to us in that particular channel—I mean, most of the money that we spend for food, we spend for food at restaurants, or food that we eat out. Then the other channel is the one that is overwhelmed right now, because it's actually having to do both its own job, as well as to backstop for all the foods that we normally would be eating when we go out. And this is the grocery channel. And it's important to understand that each of these channels have their own distribution networks, their own packaging methods, their own volume, transportation. And that if you prepare for one, you're not prepared for the other. JJ: Right. RS: You've packaged, you’ve labeled, you've processed for one of them and not the other. And so the system is not very fungible. What makes the most logic to someone that just reads about all of this waste is to say, well, as you said in your question, there are all these people lined up at food pantries, because suddenly they're unemployed. And that channel, which is referred to in the food system as the emergency food channel, actually is a redistribution channel. So usually food that is not used, or that, for some other reason—it's been mislabeled or it doesn't meet a quality standard or is leftover—that's the stuff that typically would go over to the emergency food channel. So nobody is equipped, there is no switch anyplace, where you can suddenly say, “Oh, that channel needs this much more food.” And the way in which folks at food pantries, and the people using those food pantries, can use the food is in very small quantities; nothing like what these major food channels can deliver. And so now, let's go back to your question about farmers. The way this whole thing looks to farmers is that they've contracted—typically in advance; they're making huge investments, many of them, millions of dollars in advance—for putting their crop in the field. And if their contracts are canceled, someone still has to pay for the picking, the processing, the transportation. And it can't be on farmers; that's something that somebody else needs to pay. Food pantries can't pay for that; as I just told you, they usually receive what others can't use, so they don't have the resources to do this. So it may be that these places are just miles from each other, but there is no way that the costs that are involved are going to be covered by the structure of the food system as it is right now. And for farmers, if they have produce, if that's what we're talking about, returning it to their soil is a way of recovering some of their costs, because that turns into fertility for their soil, for instance, just one example. So that way, it's not a total loss for them, but it is a major loss for them. In other words, they're not realizing profit. So that's the structure of our food system. That's why we get some of these inanities. JJ: And you can understand that if your business model as a farmer is based on selling or providing a particular thing to restaurants, or to hotels, they can't just shift on a dime what they're doing, is what I hear. RS: Yeah, exactly. And I will just clarify: Very few of them actually do sell directly to restaurants or to hotels. They typically will sell to contractors, very large firms that actually handle the packaging and the transportation. JJ: Like Cargill or something. RS: Right, companies like that. And then those folks are the folks that turn around and provide the exact packaging, the exact form that's required, by either food service or grocery. JJ: Let's talk about another aspect of the industry. Listeners may have heard that workers in meatpacking plants, for example, are falling sick in large numbers, and in some cases being threatened with job loss if they want to protect their health. You've written recently for Medium about the conditions for agricultural workers, and in strong terms. What should we know about the way the agricultural system treats people? RS: Yeah, this is one of the biggest revelations of the pandemic. It is applying a stress test to our entire society, not just the food system. But when it comes to the food system, one of the things that it's revealing is a seamy underside that is well-known to everybody within agriculture, but tends to be a revelation to people outside of agriculture. Outside of agriculture, I think it's pretty common for people to feel like it is a very vast global web of logistics that delivers anything you want, just in time, because that's the way that most of us experience it. So you imagine computer systems and sophisticated software and blinking lights and high technology, and in fact all of that does exist. But none of that would work if you didn't have people that were in the soil, working to harvest, that were not actually hacking away at carcasses in meatpacking plants, that weren’t pushing enormous amounts of groceries onto shelves, and doing all of the back-of-the-house work that none of us ever see. And that system—you know, I’ve referred to this term of “the structure of agriculture”—is a system that looks very much like a social hierarchy that many of us will remember from grade school, where we had slaves at the bottom of the pyramid and the pharaoh or king up at the top of the pyramid, fewer and fewer people benefiting as you go up the pyramid. In agriculture, we still have pretty much that system.  Ricardo Salvador: "Emancipation never really came to agriculture, in the sense that we still don't pay the full value of the labor that's required to make the entire system work." And in the United States in particular, because of our history, not very long ago, the people that performed all of the jobs that I just listed right now, or their equivalents, those were performed by enslaved people, people whom we forced to do this for no pay, for no compensation; we appropriated their labor. And that era is not that long ago. As everyone listening knows, emancipation didn't occur, at least officially, until 1865. But the fact is that emancipation never really came to agriculture, in the sense that we still don't pay the full value of the labor that's required to make the entire system work. Now, I could spend a lot of time talking to you about that. But we recently have been forced to recognize how essential these workers are, by actually giving them that official designation. “Essential” means, “Without you, the whole thing doesn't work.” But there's asymmetries here. One major asymmetry is we say, on the one hand, that they're essential; we would like to compel them to go to work so that the rest of us could have the comfort of still ordering in our T-bone steaks and what have you. But we don't pay these people in a way that reflects how essential they are. That's one asymmetry. The other asymmetry is that they do work that no one in this country is willing to do. There's lots of ways that I can support that statement. But one way is that under high periods of unemployment, like the one that we're going into right now, you would think that unemployed people would seek whatever job is available to them. So there is a labor shortage in agriculture to do all of the field labor and packing, processing that I just described. And Americans are not doing that work. That is actually verifiable. One of the ways that you can verify it is that we have a program that's called the Domestic Guest Worker program, that seeks to backfill for the labor shortage in agriculture when domestic workers will not do that work. And they are required to show that they've advertised, that they've recruited, that they've done everything possible to hire citizens to do this work, and only when they've certified that they can't get enough people domestically to do that work are they then granted an allotment of visas to bring in people from outside of the country. And that's actually how we run the food chain. So they're essential in the sense that there's a supply-and-demand issue. There's a mismatch of supply and demand. There's a demand for agricultural labor. We're not filling in it domestically, so we bring in people internationally, migrants, to do this work for us. And we exploit them, because we don't pay them the fair value of their labor. So that's the structure of our food system. It's very much modeled on antebellum plantation economics. JJ: It reminds me, also, of restaurants, the so-called “tipped wage,” so that you can pay someone $2.13 an hour, and that stemming, the history of that coming from restaurants, along with the Pullman Porter company, just not wanting to pay formerly enslaved people, and wanting them to have to rely on tips, and that continues with us today. And every time folks try to get rid of that tipped wage, or to raise it, the restaurant industry complains that they simply don't—it's another category of person that has been designated “essential, but expendable,” you might say. RS: That's it exactly. JJ: And I learned from you that, cravenly, the farm industry, those domestic guest workers that you were just talking about, the industry is now trying to cut their wages? RS: There's a phenomenon that all of us are observing at the moment that.... We could make this a political conversation, and I will try to steer away from that. But the fact is that policy is involved, and the phenomenon that I'm referring to is the phenomenon that's known typically as the fog of war. When you have a major crisis that is absorbing the public's attention, this is a prime time to try to push through policy goals that normally would just be completely intolerable, unpalatable, to the public. And so one of those goals is that, in spite of the obviously exploitative nature of the structure of the food system that I've just described to you, major players in the system still want to squeeze more out of that supply chain, and they don't see the workers as people who have the same needs as they and everybody else in this country do, to have such things as, for instance, occupational safety standards applied to their workplace, to have health benefits, to have retirement benefits, to earn enough to have dignified livelihood, meaning you can afford decent housing, you can afford to feed yourself and your family. We actually see them as “inputs”; that’s special agricultural language. “Inputs” is the machinery you need, the tractors and all of that, it's the fertilizers, the seeds that you need, and so on. And labor is seen as an input. And the way that you try to fatten up your profits is to cut the cost of your inputs, so that you get greater margin. So this is the policy agenda that is being driven right now under this fog of war underneath the pandemic. The language that the secretary of Agriculture, who very much backs this agenda, has used, he says that this is “wage relief for farmers.” What farmers actually need is fair prices for what they produce, which, by and large, they don't get right now. They don't exist in a competitive environment, and they don't have the leverage where they can actually negotiate fair prices for them. But that's actually what they need. If they could negotiate fair prices, they could afford to have it in their economy to pay all of their costs. But that's not the situation that we have right now. So what you have is the top of this pyramid that I described earlier, which is essentially the highly concentrated agribusiness sector, attempting to exploit the moment to cut as many costs as possible, and one of those costs is the cost of farm labor. And they’re cravenly taking advantage of the fact that, for all the reasons that I just described, these are people that are politically invisible; they don't have muscle. Many of them are domestic guest workers in the country; they signed paperwork that says they're only here to work in fields, that's all, and when they're done, they return home. Or else they're not documented, and so what are they going to do when they’re exploited? Sue? They have no standing, and so that’s being cravenly exploited. There was a very nice piece by Alfredo Corchado in yesterday's New York Times whose headline just captures the situation that we're in right now. The headline is, “If a Worker Is Essential, They Can't Be Illegal.” That's the quandary that we're dealing with right now; that's the hypocrisy that we need to recognize in the nation's labor and immigration policy. We're not valuing these people for, at the very least, the value they bring to the economy, much less as human beings. JJ: How do we take our understanding of that situation and turn it into action to make things different? What can folks do? RS: I think we've actually reviewed some of these things, so I'll give you a real quick list. So I mentioned that this is a stress test of the food system, and so the brittle points, the cracking points, they've become readily available. We need a food system that is fungible, that has redundancy built in. The so-called efficiencies that have been built into the highly specialized industrial model that we have right now, we are now learning, do not serve us when you have a situation where a single thing that is unpredicted takes out one pillar of the food system, and then the whole thing comes crumbling down. That's not the kind of food system that we need. We need one that is more distributed, meaning that there are more nodes within the food system that can respond in the volumes and quantities and the formats that are necessary for where people are going to be using this food. Now, a very good example of that is that the farmers that are doing well right now are the so-called small-scale family farmers. These are folks that produce in volumes, and who redistribute in local and regional networks, where they can respond very quickly, to where the schools are now becoming redistribution points for SNAP, for instance, or for school food that needs to be picked up by students that otherwise might not have access to that food, because they’re not coming to school every day, and so on. Or through farmers markets, another very important redistribution method which is very fungible. So we're learning that that's actually what works; we need to invest more in these kinds of highly distributed systems, and less in the highly concentrated systems. We need to reform immigration policy to recognize the economic value and the human rights that we need to accord to everyone that's making us wealthy and keeping us well-fed in this country. We need to reform labor standards so that it's safe for people that are working in the fields, and it looks like they're living in the 21st century, and not back in the 19th century or the 18th century. And there are very specific people who are responsible for making the decisions that I've just described. Everybody can talk to their congressional representatives and have them talk to their congressional leadership, the senior leadership of Congress, because these are the people who were pressured by the folks that are at the top of the food system pyramid. And the folks at the top of that food system pyramid, I'll just give you some actual organizations and names. Probably the single most influential agricultural lobby is the American Farm Bureau Federation. They say they represent farmers, but they actually represent agribusiness. And the president of that organization is Zippy Duvall. Let that man know what you think about everything that you've heard here. Somebody else that plays a very big role in terms of fruits and vegetable production in the United States is the president of the Western Growers Association. That individual, the president that leads that organization, is a guy by the name of Dave Puglia. Let him know what you would like to see instead of the system that we have right now. The person that's carrying the water for all of this in the White House is President Trump's chief of staff. He very much says his whole career has been about small government. That individual’s name is Mark Meadows. And by the way, I'll remind everyone that we're living in a time where, to quote Noam Chomsky a couple of weeks ago, every fiscal conservative is hiding their copy of Ayn Rand and is lining up for benefits from the nanny state. There's a lot of hypocrisy that we need to throw in these people's faces, because that's the urgency that the degree of exploitation and dysfunction that we’re living through demands. Probably one of the biggest cheerleaders for this dysfunctional food system that we have is the current secretary of Agriculture, Secretary Sonny Perdue. I would definitely advise that people let him know that we're seeing everything that they're doing, and the cynicism with which they're treating farm laborers in particular, but the way in which they're using the situation to essentially just throw more money at a system that clearly is failing. And the last of the people that I’ll name, because they're in the headlines every day, even though folks don't know them by name, these are the folks that run the meatpacking industry in the country. And I particularly recommend people contact Larry Pope, who heads Smithfield Foods, and Noel White, who heads Tyson Foods, because these are the folks that are making the decisions to force people to show up to work. They're interested in maintaining share value more than they're interested in preserving the health of their workers. They put out press releases saying that they value nothing more than the health of their workers, but they're forcing them to work under highly unsafe conditions, given the etiology of this particular pandemic, the coronavirus. We know how to stave further spread, but they're actually not willing to adopt the recommendations that come from CDC, specifically, because it would slow their production line; it would slow their volume. Well, this is happening to them anyway, which is why they're reacting in a way that demonstrates plutocracy in action: They've told the president what to do, and the president responded by saying, through an executive order, that these plants must remain open, implicitly that workers are compelled to show up to work against their health interests. So these are the sorts of things that these leaders are condoning, that they need to hear about, that eaters are not going to support. JJ: We've been speaking with Ricardo Salvador of the Food and Environment Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists. They're online at uscusa.org. You can read his piece, “Agribusiness Is Using the Covid-19 Crisis to Slash Food-Worker Wages,” on Medium.com. Thank you very much, Ricardo Salvador, for joining us this week on CounterSpin. RS: Thank you very much for the opportunity. |