LELAND NALLY

OCTOBER 9, 2020

MeidasTouch

Independent journalist dials 2,000 numbers from Epstein’s infamous black book—and uncovers it was just as much Ghislaine Maxwell’s as Epstein’s. Dina Doll breaks down how the investigation reveals Maxwell’s central role in the network—and what it says about Trump’s possible pardon of her.

I Called Everyone in Jeffrey Epstein’s Little Black Book – Mother Jones

https://www.motherjones.com/politics/...

Lola Blankets: Get 35% off your entire order at https://LolaBlankets.com by using code: MISSTRIAL at checkout.

Visit https://meidasplus.com for more!

MeidasTouch relies on SnapStream to record, watch, monitor, and clip the news. Get a FREE TRIAL of SnapStream by clicking here: https://go.snapstream.com/affiliate/m...

Support the MeidasTouch Network:  / meidastouch

Add the MeidasTouch Podcast: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast...

Buy MeidasTouch Merch: https://store.meidastouch.com

Follow MeidasTouch on Twitter:

/ meidastouch

Add the MeidasTouch Podcast: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast...

Buy MeidasTouch Merch: https://store.meidastouch.com

Follow MeidasTouch on Twitter:  / meidastouch

Follow MeidasTouch on Facebook:

/ meidastouch

Follow MeidasTouch on Facebook:  / meidastouch

Follow MeidasTouch on Instagram:

/ meidastouch

Follow MeidasTouch on Instagram:  / meidastouch

Follow MeidasTouch on TikTok:

/ meidastouch

Follow MeidasTouch on TikTok:  / meidastouch

/ meidastouch

EXCERPTS (THIS IS A LENGTHY MUST READ ARTICLE!) :

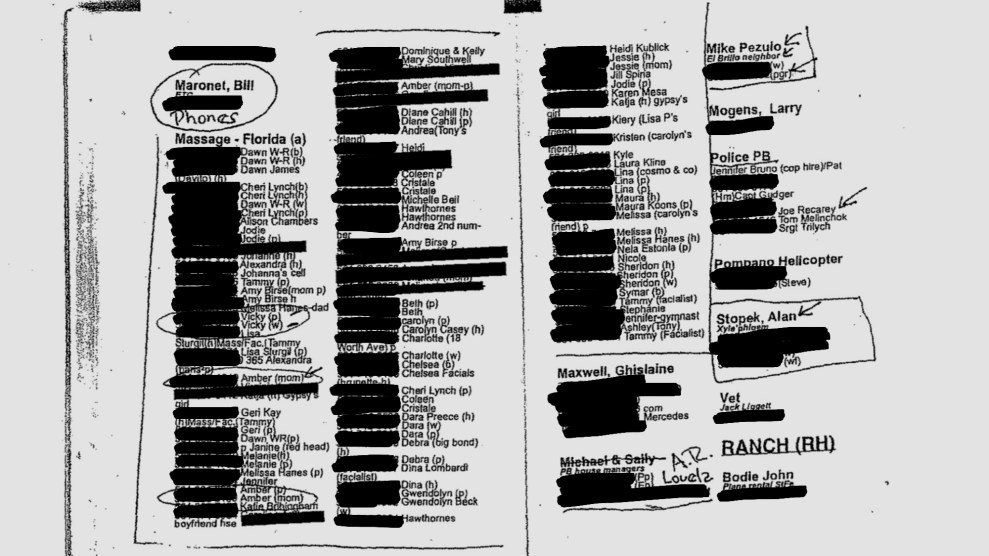

Jeffrey Epstein’s little black book is one of the most cursed documents ever compiled in this miserable, dying country. Totaling 97 pages and containing the names, numbers, and addresses of a considerable cross section of the global elite, Epstein’s personal contact book first turned up in a courtroom in 2009 after his former butler, Alfredo Rodriguez, tried to sell it to lawyers representing Epstein’s victims for $50,000. Rodriguez described the book, apparently assembled by Epstein’s employees, as the “Holy Grail.” It is annotated with cryptic marginalia—stars next to certain entries, arrows pointing toward others–and the names of at least 38 people are circled for reasons that aren’t totally clear. There are 1,571 names in all, with roughly 5,000 phone numbers and thousands of emails and home addresses. There are celebrities, princes and princesses, high-profile scientists, artists from all over the world, all alongside some of the world’s most powerful oligarchs and political leaders—people like Prince Andrew (circled), Ehud Barak (circled), Donald Trump (circled).

Rodriguez was Epstein’s butler at his Palm Beach mansion for many years. He was intimately familiar with his boss’s sexual proclivities. He claimed to have seen nude underage girls at Epstein’s pool, said that he would routinely wipe down and stow away sex toys in Epstein’s room after “massages,” and alleged that he saw child pornography on Epstein’s personal computer. In 2011, Rodriguez was sentenced to 18 months in prison for having tried to sell the book to an undercover agent after failing to notify investigators about its existence. Rodriguez said in court that the book was “insurance” against Epstein, who wanted him to “disappear.” Rodriguez died of mesothelioma shortly after serving his sentence.

The public first became aware of the book in 2015, when the now-defunct website Gawker published a version of Rodriguez’s copy, revealing for the first time just how ludicrously connected Epstein was to the people who run the world. Gawker’s file showed only names; attached phone numbers and emails were blacked out. Shortly before Epstein’s mysterious death in August 2019 in his cell at the Manhattan Correctional Facility, an unredacted version of the book popped up on some dark corners of the internet, with almost every phone number, email, and home address entirely visible, and I got my hands on a copy.

Epstein’s little black book isn’t little at all—it’s gargantuan. Its defining feature is its size and thoroughness, and there are just as many boring numbers as exciting ones–for every Jordanian princess there are three reflexologists from Boca. The listings are at times preposterously detailed, often containing additional names and numbers for people’s emergency contacts, their parents, their siblings, their friends, even their children, all alongside hundreds of car phones, yacht phones, guest houses, and private office lines. Some individuals have dozens of numbers and addresses listed, while others list just a single number and first name. Epstein collected people, and if you ever had any interaction with him or Ghislaine Maxwell, his onetime girlfriend and alleged accomplice, you more than likely ended up in this book, and then several years later you received a call from me.

I made close to 2,000 phone calls total. I spoke to billionaires, CEOs, bankers, models, celebrities, scientists, a Kennedy, and some of Epstein’s closest friends and confidants. I sat on my couch and phoned up royalty, spoke to ambassadors, irritated a senior adviser at Blackstone, and left squeaky voicemails for what must constitute a considerable percentage of the world oligarchy. At times the book felt like a dark palantir, giving me glimpses of dreadful, haunted dimensions that my soft, gentle, animal being was never supposed to encounter. At other times it was nearly the opposite, almost grotesquely boring and routine. Seeing at close range the mundanity of Epstein and his fellow elites–how simple and childish they could be–was a sickening experience of its own. The worst call by far was with a woman who told me she’d been groped by Epstein, an incident she said she didn’t report at the time out of fear of retribution from Epstein. (I have been aggressively counseled to remind the readers of Mother Jones that an appearance in the address book is not evidence of any crime, or of complicity in any crime, or of knowledge of any crime.)

They weren’t all elites, thankfully. Sometimes I would have delightful conversations with normal people who had cleaned a car or given Epstein a facial, and only shared in my distaste for Epstein and his circle. Sometimes I would call a number that had changed hands at some point since the book was compiled, and instead of reaching the governor or fashion designer I was looking for, I would end up with just a normal bloke on the line, some poor recipient of a torrent of wrong-number phone calls of the worst variety imaginable. Their fate was a twisted inversion of my own: The oligarchy wouldn’t stop calling them.

Some highlights and lowlights from my tour of Jeffrey Epstein’s little black book. Remember: An appearance in the address book is not evidence of any crime, or of complicity in any crime, or of knowledge of any crime.

Doug Band, longtime adviser to Bill Clinton: Called a number listed as his home number, which wound up being his childhood home. Spoke to his dad for five minutes. Seemed like a decent guy. “Doug hasn’t lived here for 30 years!” All right, man, take care!

Jimmy Cayne, former CEO of Bear Stearns: Wife answered the phone. When asked about Epstein and Cayne’s relationship, she said, “Yes, they were friends, but we have no comment.”

“Yeah man, people keep calling me up, asking for Muffie, and I’m like, you know, I’m just always polite, man.” That’s Elijah Hutch, 22-year-old aspiring music producer who lives in Flatbush in Brooklyn. He has the old cell number for Muffie Potter, wife of world-famous plastic surgeon Sherrel Aston and the fourth-greatest socialite in history, according to Town and Country magazine.

“They’ll text me about some dinner I went to, or how it was great seeing me with so and so, and I’m always just respectful man and just let them know, ‘Hey, man, I think Muffie gave you the wrong number.’” Eli had no idea who Muffie was, or Epstein for that matter, and I almost didn’t want to explain it to him, but I did: the child sex ring, the princes, the presidents, the suicide, the black book–everything. Out of all the people I spoke to, Eli had by far the most cogent analysis of the situation.

“Damn, man, this is all sounding so strange.” Find Eli Hutch on SoundCloud here. Let the haunting lyrics of “Go Away” give you strength as they did me, awake at my desk at 4 a.m. so I could call every pedophile in London.

My demons creeping, getting close, they just want to snatch my soul, but I won’t let them get a hold

What a world, any phone can reach any other. It’s almost unbelievable what a string of seven to 12 numbers can get you. All I did for weeks was sit on my couch, feel like dogshit, flip through this haunted book, and call people up one by one in between bouts of stress diarrhea. That’s it. You just type the numbers in, and sometimes you get a ring, and sometimes a person picks up.

THE FUZZ (MAYBE)

I made the first call from a coffee shop in Los Angeles’ Koreatown the day after Epstein’s suspicious suicide in his cell at Manhattan’s Metropolitan Correctional Center while awaiting trial, a convenient turn of events for the rich and famous people who would now avoid exposure in court. The death was a national scandal. Followers of the Epstein case—I’m including myself here—reacted to his death with a burst of paranoia and anger. Conspiracizing was rampant. I had come across a screenshot of an unredacted section of the black book and determined to track down its source. I decided to check the most awful place on the internet, 8chan, where I was quickly rewarded for my intuition—an unredacted PDF of the entire book had been posted just a few hours earlier. About 12 seconds later I was dialing Melania Trump’s personal cell phone. Voicemail. Then I sent a text to David Copperfield. “David, we need to talk. It’s about Jeffrey.”

I tried a couple more people, none of whom picked up, whereupon I was interrupted by a call from a restricted number. The guy on the line said he was with the FBI. He said there were “reports of fraudulent phone calls” being made on this line, which I immediately understood as bullshit—I wasn’t committing any phone crime or trying to trick someone into doing so. “I don’t know about fraudulent, but I have a feeling I know what you’re talking about,” I said, undoubtedly sounding cool, relaxed, unbothered. He then said, “I have a real call coming in,” to what sounded like someone else in the room, his voice quiet in the way of someone who has just pulled the phone off his face to look at it. He hung up and never called again, as far as I know. Whether the guy was FBI or a private security goon posing as a fed, the call was an important development—it told me that the book I was dealing with and the numbers it contained were genuine. Every cell phone, every yacht line, every private office number—they were all real, and every one of them was about to get a call from me.

THE ART-COLLECTING SCIENTIST DILETTANTE: “YOU’RE SO FULL OF SHIT.”

The next day I began calling en masse. By now, in an effort to spare my girlfriend any psychic harm, I was operating from the Los Angeles Central Library, first from a foyer, my voice bouncing off the high marble ceilings with embarrassing levels of clarity and volume, and then from a corner of the library’s art gallery, deftly maneuvering around any guests when necessary. That day had been terrible, full of wrong and disconnected numbers, and I was close to quitting the entire project out of both fear and hopelessness when I placed what was maybe my 50th phone call, to Stuart Pivar, who answered the phone and told me, “Jeffrey Epstein was my best pal for decades.”

Pivar, 90 years old, is an art collector, scientist, and a founder (alongside Andy Warhol) of the New York Academy of Art. He ended up speaking with me for over an hour about his “very, very sick” friend in a conversation we wound up publishing in its entirety. Stuart told me—over and over again—that Epstein suffered from “satyriasis,” which he described as the male version of nymphomania, and that he used his money and power to “make an industry” out of having sex with underage girls. This apparently entailed Epstein having sex with “three girls a day” and “hundreds and hundreds” in total. He said he never knew Epstein was having sex with children until Maria Farmer, a student at the academy and an acquaintance of Pivar, had told him she had been assaulted and held hostage by Epstein. He also claimed that Epstein had never invited him to what he called “The Isle of Babes,” a reference to Epstein’s private island where much of the child sex trafficking allegedly occurred.

Pivar said he was “in mourning” for Epstein, who had died just two days before we spoke. By turns morose, defeated, and indignant, veering between florid ruminations about teenage sexuality and bitter denunciations of me and my life choices, he unloaded his thoughts and feelings about Maxwell and Leslie Wexner, Epstein’s billionaire patron, as well as about the nature of perversion, criminality, perhaps even life itself.

On pathology: “What’s a pervert? There are all kinds of behavioristic aberrations, obviously, including mass murderers. You don’t call mass murderers ‘perverts,’ do you?”

On nature and civilization: “And so, all kinds of rules get made. And nature is not allowed to take its course on account of civilization. Jeffrey broke those rules, big time. But what he was pursuing was the kind of, I suppose, sexual urges which would—why am I telling you this stuff for? Leave me alone. Go away.”

On Epstein accuser Virginia Giuffre and Epstein’s child-sex ring: “Anyone who did one thing, let us say, to some 16-year-old trollop who would come to his house time after time after time and then afterwards bitch about it—why, no one would pay attention. Except Jeffrey made an industry out of it.”

On nature and civilization, cont’d: “The business of sexual attraction, the attraction of males and females in its natural state, is not the same as what happens when civilization puts [up] all kinds of rules. Because sexual attraction starts at a very, very young age. When I was 14, I had to deal with a girl who was only 13. And somehow, I remember, it was at summer camp. And I stopped having to do with her because of the tremendous age gap.”

On me and my life choices: “You’re so full of shit, it’s terrible. You should not be writing about this. You’re not qualified.”

On himself and his life choices: “Why did I talk to you! I’m a dead fish, and you’re going to ruin me. Luckily, I don’t know anybody who reads the Mother Jones anymore. I can’t believe it still existed.”

On my having inveigled him, so to speak, into yapping pointlessly: “You inveigled me, so to speak, into yapping pointlessly because I have nothing else to do for the moment, and I’m relying on you to understand what I say. If you misquote me or anything like that, I will sue your magazine until the end of the Earth….Tell me your name again so I can start writing a complaint to sue you.”

Somewhere in all this, Pivar managed to tell me the entire backstory of his decadeslong friendship with Epstein. Pivar had met Epstein through the New York Academy of Art, where Epstein was a board member. It was at an NYAA function where he met a young Maria Farmer, who along with her younger sister would become one of Epstein’s earliest accusers. Farmer, a painter, was at the Wexner mansion at Epstein’s invitation for what she believed was an art residency when, she alleges, Epstein and Maxwell sexually assaulted her and held her hostage for 12 hours with the aid of Wexner’s massive security team. After the ordeal, Farmer soon learned that her younger sister had also been assaulted by Epstein and Maxwell during a similar “artist residency.” Pivar told me he ran into Farmer at a flea market where she told him “this bizarre story…and I realized oh my god something was happening after years and years, which he”—Epstein—”didn’t tell me.”

My hourlong conversation with Pivar was genuinely illuminating. Pivar spoke about Epstein in the exact way many of his friends and colleagues would speak about him to me in the coming weeks—reverence mixed with an acknowledgement of Epstein’s essential disingenuousness. Much has been made in the press of Epstein’s intelligence, mostly due to his vast wealth, the glowing adoration of his elite peers, and the long roster of high-profile scientists and thinkers with whom he surrounded himself. Pivar was the first person to peel back the curtain of Epstein’s reputation with intimate, firsthand knowledge of the man himself, and to counter the prevailing media narrative at the time.

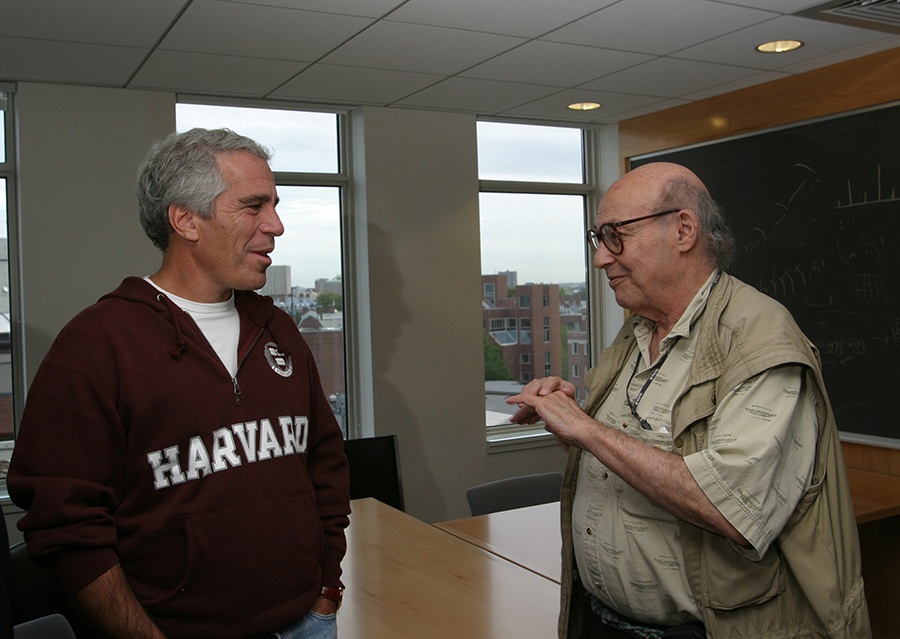

Jeffrey Epstein with the late Marvin Minsky, known as “the father of artificial intelligence.”

Rick Friedman/Corbis/Getty

Pivar had attended a few of the now widely publicized intellectual summits at Epstein’s house in New York. Epstein hosted dinner parties for world-famous scientists and thinkers from around the globe, people like Steve Pinker, Stephen J. Gould, Martin Nowak, Lawrence Kraus, and Marvin Minsky. “Jeffrey didn’t know anything about science,” Pivar said. “He would say, ‘Oh, what is gravity?’ Which of course is an unanswerable thing to present at a dinner to a bunch of scientists. And because he was Jeffrey, why, they would—and as the founder of the feast—they would listen to him and try to give [answers]. He was attempting, somehow, in his ignorant and scientifically naive state, to do something scientifically important. He had no compunctions about inviting people, and since he had money, they would listen.”

Epstein used his money and influence to brand himself an avant-garde intellect, a sparkling autodidact dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge on the far-out edge of human perception. In large part, it worked extraordinarily well. You could build mountains out of the bizarre, nebulous claims of esoteric knowledge ascribed to Epstein. “He was good at puzzles and finding things out. He could look at an organization and see what was wrong,” one friend told me. Wexner, when asked by Vanity Fair about his relationship with Epstein, said that he was good at “seeing patterns” in politics and financial markets. “Epstein’s mind goes through a cross section of descriptions,” Joe Pagano, a longtime friend of Epstein, has said. “He can go from mathematics to psychology to biology. He takes the smallest amount of information and gets the correct answer in the shortest period of time. That’s my definition of IQ.” Epstein’s attempt to portray himself as a galaxy-brain genius was surely helped along by his vast fortune—as I would find, the myth of his genius and the fortune were mutually reinforcing notions. His brilliance went largely unquestioned, because how else could he have been so rich? His wealth wasn’t so mysterious once you understood just how brilliant he was.

But Pivar didn’t buy it—at least not entirely. He still called his old friend a “very, very brilliant guy” and said Epstein had “a very—how should I say—charming way of expressing himself.” But Pivar also acknowledged that Epstein was a bullshitter. He “couldn’t concentrate on a subject for more than two minutes before having to change the subject, because he didn’t know what anyone was talking about and would blurt out the dumbest things,” Pivar said. In particular Epstein had an affinity for posing pseudo-deep questions like “What is up?” and “What is down?” at the scientific summits he hosted on his private island.

The act would wear thin eventually, Pivar recalled. “While everybody was watching, we began to realize he didn’t know what he was talking about. Then after a couple of minutes—Jeffrey had no attention span whatsoever—he would interrupt the conversation and change it and say things like, ‘What does that got to do with pussy?!’”

THE ACTRESS: “IT’S A WEIRD FEELING, I’M KIND OF REPULSED…”

Pivar was the first person I spoke to who had actually been close to Epstein. There would be others, and they would speak as freely and searchingly about Epstein as Pivar had, musing about their place in his life, some wracked with guilt, some clumsily rushing to his defense. By far the most eager sharer was an actress who had met Epstein in the early ’80s, before he’d gotten super-rich, and who maintained a decadeslong close friendship with him as he rose into the ranks of the elite. She asked that we not use her real name—we will be calling her Julie.

Julie’s name did not have any particularly special notation in the book. She’s not famous, by any means, and as far as I know she hasn’t ever talked to any other reporter or media outlet. “I like talking to you, I don’t really want to talk to anyone else,” she told me at one point. “How old are you? You’re like my therapist.”

Julie and I would speak multiple times on the phone over the months I worked on this story, sometimes for over an hour, sometimes for just a few minutes. She met Epstein in the 1980s at a dinner with her agent and a group of models at a known “model hangout” in New York City. Epstein approached the table and asked if any of them would like to go party at his apartment, and some of the women agreed, Julie included. While Epstein played the piano for the small crowd in his place, a friend of hers pulled her aside and told her, “I think he’s hitting on you.”

Julie allowed there was some initial mutual attraction and flirtatiousness, but nothing “crossed the line,” she said. The two were friends and remained friends and nothing more for their entire relationship. Soon after they met, Julie would find herself talking with people like Vera Wang and Andy Warhol at Epstein’s dining room table, or flying with Epstein on his private planes to meetings and parties around the world. She’d take a couple trips to his private island, Little Saint James; frequent his properties in New York, New Mexico, and Palm Beach; chill with a few of Bill Clinton’s staffers; and meet many of the people in Epstein’s inner circle, including Virginia Giuffre, his eventual accuser. “She was always there” in Little Saint James, Julie said.

Epstein’s home in Palm Beach, Florida.

Emily Michot/Miami Herald/TNS/ZUMA

Julie was always adamant with me that she never witnessed any sexual abuse during her entire relationship with Epstein, and that while she and everyone else knew that Epstein was into young girls, she never questioned whether any were of legal age. She also repeatedly told me how “happy” all the girls were to be with Epstein, at least the ones she saw. “The girls that complain and say they didn’t want to be there, or that they weren’t happy—if someone was unhappy, he had no time for you. His attention span was short and he could be really rude. So any girl that was around him had to be up and bubbly,” she said. “You know, he was always joking around, doing stupid, like, sexual jokes—if there was some girl walking around he’d pants her or something, you know what I mean? But it was always in jest….I let him go back then, but, you know, it’s a weird feeling. I’m kind of repulsed, but somewhere deep down I do miss that personality.”

Julie seemed absolutely helpless in the face of the monstrousness of the Epstein saga, and over the hours of calls we had she would achingly retrace her relationship with him and his circle with me. At times she was resolute in her condemnation, despairing over the seriousness of his crimes and at one point telling me she was “glad he’s dead.” At other times, even though she was a survivor of sexual assault as well, she would grow irritated and retreat into denial, offering sloppy, desperate defenses of Epstein’s actions or doubts about victims. She read me excerpts from her diary over the phone, shared gossip, and led me to flight logs and photographs to corroborate her story. She wept over how such an influential figure in her life, someone who treated her with kindness, someone whom she looked up to, could have done such awful, hideous things, and how terrible it was to look back on their relationship and feel betrayed, and worse still, to miss him. Although she had better insight into his life than perhaps most people on this Earth, she too had agonizing, unresolved questions, and parts of Epstein still remain an enigma even to her.

“I think a lot about why my role and some girls roles were different,” Julie told me. “I think Jeffrey liked to exploit people. If he saw a girl and could corrupt her, he might like that.”

There are two things that make Julie’s story unique. One, unlike many of Epstein’s friends, she is not a famous or known person. No reporter would know about her unless they did what I did and called every single person in the black book. Two, she knew Epstein well and from a very early point, being a part of what she called a small, core group of friends who remained in his life from before he was the rich and infamous figure the public knows him as today. From up close, Julie says, she watched his personality change as his riches and connections grew.

Throughout the many years of their friendship, she attended several private gatherings where only a small number of Epstein’s friends were present, giving her an opportunity to meet and get to know the big players in his life. When Julie first met Epstein he was wealthy but far from the ultrarich guy he would become. He was secretive about his work, always, but she believed he was working as a “bounty hunter” when they met, helping track down embezzlers for corporations (and possibly governments).

She told me she sat in on a meeting in Paris between Epstein and Leslie Wexner, the founder of L Brands and Victoria’s Secret who says Epstein embezzled at least $46 million from him. This was early in Epstein and Wexner’s relationship, not long after the two had been introduced by insurance tycoon Robert Meister. Epstein began working for Wexner in the late 1980s, though the nature of that work still isn’t entirely clear. Vanity Fair in 2003 said it was “related to cleaning up, tightening budgets, and efficiencies.” Julie told me Epstein was helping to track down employees who Wexner believed were “stealing” money from him at L Brands headquarters. “Leslie had said to him: ‘I have a problem in my company—there’s something wrong, someone is stealing from me. Would you fly out to Ohio’—and, of course, that’s like hell for Jeffrey, going to Ohio–‘would you fly to Ohio for several months going over all my books with a fine tooth comb and find out what’s going on?'”

On the plane to Paris, Epstein prepped Julie for the meeting. It was just going to be the three of them—Epstein, Wexner, and Julie. (Julie wasn’t attending in any official capacity. She was meeting some friends in Paris, and Epstein invited her to catch a ride with him on Wexner’s plane.) She recalled a nervous and excited Epstein telling her to be on her best behavior, worried that she might say something that would make him look bad, and emphasizing how important this meeting was.

“Wexner was this super-successful guy who didn’t really have any life, and Jeff described him to me as completely socially inept,” Julie said. ”Jeffrey was like, ‘Look at me now, wow, look at where I am,’ and it was exciting for him.”

The meeting, at least to Julie, was nothing momentous. “I remember meeting Leslie at the cafe, and all he did was eat peanuts out of the little peanut tray. And I remember, just to try and make him feel comfortable, I ate the peanuts with him….It was so incredibly awkward,” said Julie. Leslie was shy, quiet, and the meeting was short and uncomfortable—few words shared, no food served, the trio sustaining themselves on peanuts alone. In all, it was an uneventful evening, but looking back now, one can see why Epstein had been so excited about cozying up to Wexner. “Jeffrey told me, ‘This guy [Wexner] has everything in the world, but he doesn’t have anyone to share it with,’ and Jeffrey knew all the girls in the world.” That was Epstein’s MO, Julie said. “He’d take some rich guy and introduce him to a girl.” I spoke with one woman who said she met Epstein at an art fair in Palm Beach. He was direct with her. “He came up to me and said, ‘Would you like a date with Prince Andrew?’” she recalled.

In the years following, Epstein began to play a central role in Wexner’s life. “Jeffrey wasn’t just a money manager. He was a personal assistant….If Leslie had a problem with his yacht, he was there,” Julie told me. The billionaire handed over huge swaths of his finances to Epstein’s control, sold a plane and a mansion to trusts that Epstein controlled, and to the surprise of his friends and colleagues, went so far as to hand Epstein his power of attorney in 1991. “People have said it’s like we have one brain between two of us: each has a side,” Epstein told Vanity Fair in 2003. Colleagues and friends of Wexner’s were shocked at Epstein’s hold over Wexner. Julie, however, wasn’t that surprised. She recalled Epstein saying to her, “This guy has no life, and I’m going to give him a life.” It was that simple.

Epstein’s relationship with Wexner was transformative, if for no other reason than that he became incredibly rich because of it. Julie says a “huge, huge” change occurred in Epstein’s personality after his relationship with Wexner began to solidify, and particularly after he had started amassing his mysterious fortune. In fact, in her mind, three people were responsible for the changes she saw in her friend. There was Wexner. Less directly, there was Bill Clinton, who reportedly connected with Epstein through the Clinton Foundation. (“Seeing a powerful guy like Clinton get away with what he got away with,” said Julie, who never met Clinton, “I think it just emboldened him to think he could do whatever he wanted.”) And above all, there was Ghislaine Maxwell.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.