Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Will historical trends hold and Republicans do well? Or will this time be different?

According to the latest findings of the highly respected NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist National Poll, Americans overwhelmingly disapprove of the court’s ruling (56-40%). This tracks with what we have seen about polling on abortion in recent years. Taking away this right is highly unpopular. But the question that has always lingered is whether this would be a galvanizing issue for Democratic voters. Well according to this poll, the answer is a resounding yes. But that doesn’t actually make it so.

NPR summarizes the results as a jolt of enthusiasm for Democrats:

“This issue presents volatility into the 2022 midterms, because 78% of Democrats say the court's decision makes them more likely to vote this fall, 24 points higher than Republicans.”

And there has been a significant shift in which party people say they will vote for for Congress in 2022:

“Democrats have regained the favor of voters to control Congress, with 48% saying they are more likely to vote for a Democratic candidate in the fall and 41% more likely to vote for a Republican. In April, Republicans led on that question in the poll 47% to 44%, which was within the margin of error.”

But NPR's writeup of these results does include this important note:

“The lead for Democrats may not translate into maintaining control due to the way voters are geographically distributed and how boundaries of congressional districts are drawn.”

This last caution is important. We live in a federal system, so even large swings of voters, if they occur mainly in states that already are red or blue, might not swing the ultimate composition of Congress. Furthermore, those who analyze partisan leanings in congressional districts say that the latest round of redistricting has led to a far smaller pool of swing districts. This means that much of the Democratic/Republican divide is already gerrymandered in place. Wave elections in either direction become all the more difficult.

We have noted many times before on Steady the historic headwinds that Democrats face in the elections this fall. This starts with the structural precedent of American politics that the party that controls the White House almost always loses seats in Congress in midterms. Then there is President Biden’s low opinion ranking, high inflation (particularly at the pump), the lingering pandemic, and more. There is also the reality that Democratic voters are often less motivated to vote in non-presidential years.

These are especially uncertain times, and uncertainty and anxiety often rebound against those currently in power. The Democrats, with control of both houses of Congress and the White House, are in power.

I know that the Steady readership has a lot of political sophistication. You understand the broader context around the realities of this power. You know that these congressional majorities are razor thin, especially in the Senate where Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema have proven unwilling to abolish the filibuster to allow for up-and-down votes on key Democratic priorities. Furthermore, the legislative and executive branches of government are only 2/3 of the whole. The past few weeks, much of our attention has been driven by the third branch, over which Democrats clearly have no power — the Supreme Court.

If the Democrats are to make a case to voters that, while in power, they are not really in full power, they need to have a clear and deliberate message that anticipates the frustration from the electorate over what is seen as inaction on a host of important issues. You can’t keep saying “vote for us” and then not be seen as delivering.

The journalist Brian Beutler outlined this conundrum in a newsletter back in December anticipating the end of Roe.

“If Roe falls, and Democrats respond in essence by saying “elect more Democrats,” they’re going to get a resounding earful from people who expect them to use their power now, while they have it. I hope that backlash prevails on them, but one way around it would be to level with people: We will fix this by doing X, but we can’t do X until we have Y more Democrats than we currently have. That approach would have the virtue of allowing voters to hold them to a promise. But it’d also require them to specify X and Y, and I think they’re in denial about both.”

Well, in recent days that is exactly what has happened. In an op-ed in The New York Times, Senators Elizabeth Warren and Tina Smith started filling in the X’s and Y’s of Beutler’s equation:

“If voters help us maintain our control of the House and expand our majority in the Senate by at least two votes this November, we can make Roe the law all across the country as soon as January.”

This was echoed by David Plouffe, Barack Obama’s campaign manager in 2008:

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi had the same equation in mind while speaking at a press conference last Friday:

“There is a plan, and that plan is to win the election – hopefully to get two more senators so that we can change the obstacles to passing laws for the good of our country.”

And as if on cue, just as we were wrapping up this post, Hawaii’s Senator Brian Schatz tweeted out this language:

You don’t have to squint hard to see a campaign message emerge: “If you want to save legal abortion in America, you need to vote for Democrats to give enough of a majority in Congress to exert real change.” It is not the easiest sell, and it requires a bit of nuance, but it is likely the Democrats’ best chance.

Of course, evidence of Republican extremism, as we’ve noted here many times, goes far beyond Roe. We can see it on guns, voting rights, and championing the Big Lie. There are real concerns about the separation of church and state and the ability to confront our climate crises.

The shift in voter preference noted in the poll that began this Steady post is undoubtedly due in part to the Roe decision. But it also might be the expanding congressional investigation into the insurrection of January 6. Or it is the frustration over gun deaths, even with the recent legislation, which many Democrats and others didn’t feel went far enough.

Let’s be clear, the Republicans have a lot of strengths in the upcoming elections. But what Roe and other developments do is create more unknowns. They greatly expand the spectrum of the possible. They churn expectations around voter enthusiasm and turnout. Will historical trends hold and Republicans do well? Or will this time be different? Considering how divergent our next two years — and likely the decades to come — would be with the different outcomes, the question over what might happen is really a question over two very different futures for our nation.

Ultimately this will be decided by tens of millions of voters at the polls. With that in mind, I am, as always, very curious about what you think of the current state of the midterms. And, have your views changed in the wake of the abortion decision, the January 6 hearings, or other recent developments?

Department of Homeland Security agents. (photo: AP)

Department of Homeland Security agents. (photo: AP)

Garland resident wrote, “Slaughter them all,” and called for burning down government buildings after the Supreme Court’s abortion ruling. The Department of Homeland Security was not amused.

The feds’ letter to Madeline Walker of Garland came after she tweeted about burning government buildings on the day the Supreme Court handed down its decision.

Using expletives, Walker tweeted, “Burn every ... government building down right ... now. Slaughter them all,” in reply to video in which President Joe Biden urged protestors to remain peaceful.

As of noon on July 1, Walker’s original post — which landed her a warning letter from the feds — had 8 retweets and 31 likes. She has since deleted both her posts.

Less than a week later, two police officers and a Department of Homeland Security special agent showed up at her door Thursday morning with the warning letter.

“You are advised as of the date of this letter to cease and desist in any conduct deemed harassing/threatening in nature, when communicating to or about the federal government,” the letter said. “Failure to comply with this request could result in the filing of criminal charges.”

Joshua Henry, a special agent for DHS, confirmed the letter’s authenticity and said it was delivered at 11:30 a.m. on Thursday. Robert Sperling, director of communication for the Federal Protective Service, also confirmed to The Dallas Morning News that the letter posted on Twitter was delivered.

Walker could not be reached for comment by The Dallas Morning News. But in an interview with the website Jezebel, she said she did not intend for her words to be taken seriously and told agents she did not plan to burn down any buildings.

“Obviously, I’m not trying to go to prison over this,” she told Jezebel. “There could’ve been a better way for me to go about it, actively going to protest or speaking out in public or things like that. I guess maybe Twitter wasn’t exactly the best idea to pull out the stops with.”

On Thursday night, Walker posted the feds’ letter on Twitter. The tweet has since gone viral, prompting Walker to take her account private.

“This was such a nice way to get woken up this morning. 4 cops banging on my door,” Walker wrote in the deleted tweet.

“Reminding everyone that Pastor Dillon Awes of Stedfast Baptist Church in Fort Worth is allowed to preach that gay people should be ‘lined up against the wall and shot in the back of the head.’ when people reported him to the police they said, ‘free speech,’” Walker wrote, replying to her original post.

“Uhhhh where was this energy before the Jan 6th insurrection!?” another user wrote.

“Wouldn’t it be nice if they put this energy into monitoring and warning the white nationalists and misogynists who shoot up our schools, nightclubs, and places of worship?” another woman replied.

Henry said Walker sharing the letter on Twitter could bring more trouble.

“She’s kind of taking it as a joke,” Henry said. “She’s not remorseful about these statements, so that’ll be presented to a United States Attorney and they’ll make a decision on that.”

When a reporter asked the Garland Police Department if their officers accompanied a federal agent to Walker’s house to deliver the letter, spokesman Pedro Barineau wrote in an email “since DHS confirmed they went out there, they will have all the details and will need to provide the information. We can’t speak about another agencies [sic] investigation.”

On Friday night, the Federal Protective Service sent an email with an official statement to The News.

“DHS’s Federal Protective Service coordinates with law enforcement partners across the country to protect federal facilities, and those who work in and visit those buildings, from violence,” the statement read.

“FPS may issue warnings as a result of threats made to federal facilities and federal employees, in line with standard law enforcement practices. Americans’ freedom of speech and right to peacefully protest are fundamental Constitutional rights. Those rights do not extend to violence and other illegal activity.”

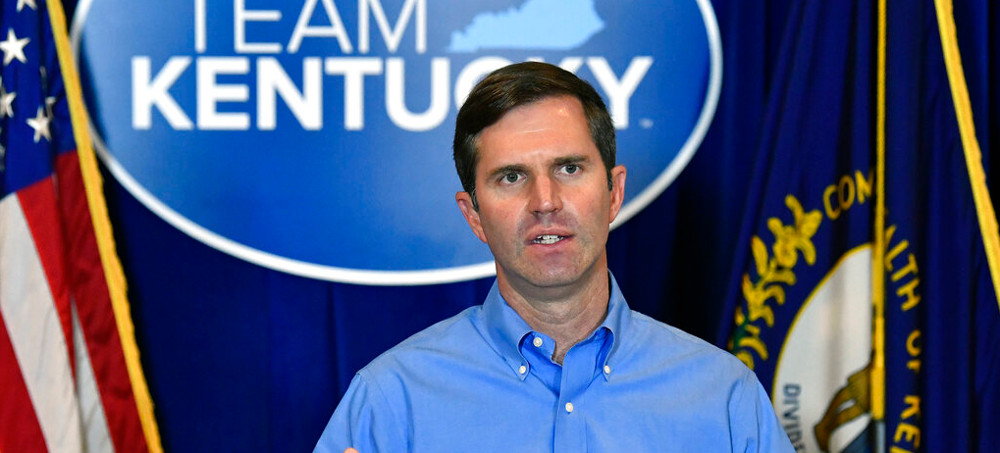

Democratic governor Andy Beshear of Kentucky speaks at an event in Lexington, Kentucky, April 08, 2022. (photo: Jon Cherry/Getty)

Democratic governor Andy Beshear of Kentucky speaks at an event in Lexington, Kentucky, April 08, 2022. (photo: Jon Cherry/Getty)

ALSO SEE: Sinema Opposes Biden's Call for

Filibuster Exception to Pass Abortion Rights

"If the president makes that nomination, it is indefensible," said Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear at a press conference on Thursday. "This is an individual who aided and advised on the most egregious abuse of power by a governor in my lifetime."

Beshear was referring to Meredith's service as former Republican Gov. Matt Bevin's deputy counsel, including when the governor issued a raft of controversial pardons — including of a man convicted of raping a child — at the end of his term in 2019.

"I don't know how the President could say he's for public safety if he makes this nomination," said Bevin.

On Wednesday, the Louisville Courier-Journal first reported that Biden planned to make the nomination in an apparent deal with Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, Kentucky's senior senator. On Friday, a federal judge in the state announced her resignation, opening up a spot for Meredith's appointment to the US District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky.

But even more concerning for some Democrats is Meredith's record on abortion, particularly in the wake of the Supreme Court overturning the constitutional right to an abortion last week.

Biden has said he would use all of his "appropriate lawful powers" to fight back against the ruling.

While working for Bevin's office, Meredith defended an abortion law enacted in 2017 that required abortion doctors to perform an ultrasound and describe the image to the patient before performing the procedure.

Democratic Rep. John Yarmuth of Kentucky called the decision a "huge mistake" and said the planned nomination was "some kind of effort to appease Mitch McConnell, which is something this state and country should be very upset about." Yarmuth's office also confirmed to Insider that he'd been informed of the nomination by the White House.

Charles Booker, the party's nominee for US Senate, went even further.

"The President is making a deal with the devil," he wrote on Twitter. "This is some bullshit."

Residents walk past destroyed apartment buildings in the city of Severodonetsk in the Luhansk region of Ukraine, on Thursday, June 30. (photo: Reuters)

Residents walk past destroyed apartment buildings in the city of Severodonetsk in the Luhansk region of Ukraine, on Thursday, June 30. (photo: Reuters)

While it is just a few incidents isolated to the town of Kherson so far, US officials say the resistance could grow into a wider counterinsurgency that would pose a significant challenge to Russia's ability to control newly captured territory across Ukraine.

The Kremlin "faces rising partisan activity in southern Ukraine," Avril Haines, the director of national intelligence, said during a conference in Washington, DC, on Wednesday.

The US believes that Russia does not have enough forces in Kherson to effectively occupy and control the region, one US official said, especially after pulling forces from the area for the fight to the east in Donbas. Another US official told CNN that move may have provided Ukrainian partisans with a window in which to attack locally installed Russian officials.

Ukraine has also conducted limited counterattacks near Kherson, further straining Russian forces.

The region is critical to Russia's hold on Ukraine's Black Sea coast and controls access to the Crimean peninsula. It's unclear how many Russian forces are in or near Kherson, but an occupation against a hostile local population requires far more soldiers than a peaceful occupation of territory.

Russia's leaders have prioritized the military campaign at the expense of any semblance of government. "It's clearly not something they're able to invest in right now," one US official said.

Trio of assassination attempts

The first attack in Kherson occurred on June 16, when an explosion shattered the windows of a white Audi Q7 SUV. The vehicle was left seriously damaged, but the target of the attack survived.

Eugeniy Sobolev, the pro-Russian head of the prison service in occupied Kherson, was hospitalized after the attack, according to Russian state news agency RIA Novosti.

Less than a week later, a second pro-Russian official in Kherson was targeted. This time, the attack succeeded. On June 24, Dmitry Savluchenko, the pro-Russian official in charge of the Department of Youth and Sports for the Kherson region, was killed, RIA Novosti reported. Serhii Khlan, an adviser to the head of the Ukrainian Kherson Civil Military administration, called Savluchenko a "traitor" and said he had been blown up in his car. Khlan proclaimed, "Our partisans have another victory."

On Tuesday, the car of a third pro-Russian official was set on fire in Kherson, according to Russian state news agency Tass, though the official was not injured. It's unclear who committed the attacks.

There does not appear to be a central command guiding an organized resistance, officials said, but the attacks have increased in frequency, particularly in the Kherson region, which Russia occupied in March at the beginning of its invasion.

A source familiar with Western intelligence was more skeptical about whether the resistance could develop from partisan attacks to a more organized campaign capable of managing the attacks and supplying weapons and instructions

So far, the resistance has not dented Russia's control over Kherson, the source familiar with Western intelligence emphasized.

But in the long term, the US assesses that Russia will eventually face a counterinsurgency from the local Ukrainian population.

"I think Russia is going to have significant challenges in trying to establish any sort of stable administration for these regions, because likely collaborators -- more prominent ones -- are going to be assassinated and others will be living in fear," said Michael Kofman, director for Russia studies at the Center for Naval Analyses, a Washington-based think tank.

Making Russian governance difficult

On Tuesday, Russian-appointed authorities in the Kherson region arrested the elected Ukrainian mayor of the city, Ihor Kolykhaiev, hours before announcing plans for a referendum to join Russia. The pro-Russian military-civilian administration accused Kolykhaiev of encouraging people to "believe in the return of neo-Nazism."

Kolykhaeiv's adviser said Russian authorities also had seized hard drives from computers, ransacked safes and searched for documents. Earlier this month, Ukraine's military said "invaders" had broken into Kherson State University and abducted the rector.

Russian forces have gradually instituted the ruble as the local currency and issued Russian passports.

In Mariupol, pro-Russian authorities celebrated the so-called "liberation" of the city in May. The Russian-aligned Donetsk People's Republic changed road signs from Ukrainian to Russian and installed a statue of an elderly woman grasping a Soviet flag. Meanwhile, the iconic Mariupol sign painted in Ukrainian colors was repainted in Russian colors.

Despite Russia's efforts to eliminate Ukrainian history, ethnicity and nationalism from Kherson and other occupied territories, the Ukrainian population shows a willingness to resist.

"The occupiers and local collaborators are making more and more loud statements about [the] Kherson region joining Russia," a Ukrainian official said last week, "but every day, more and more Ukrainian flags and inscriptions appear in the city."

The attempts to forcibly erase Ukrainian culture and dictate a Russian hegemony have produced the opposite effect in some cases, according to a senior NATO official.

"There have been reports of assassination attempts against some of the quislings that have been put in place to be governors, mayors [and] business leaders," said the NATO official. A quisling is a traitor who collaborates with an enemy force, named after a Norwegian official in World War II who collaborated with the Nazis. "That almost certainly has deterred Russian sympathizers or Russians or whoever they're going to bring in there to take these posts from taking them up in the first place."

As an occupying force in Kherson -- in particular, one that seems intent on maintaining control -- Russia has to provide basic services in the territories it manages, like clean water and trash pickup. But the US assesses that acts of resistances are making it difficult to provide governance and basic services, one of the US officials said.

The US knew there was a "serious resistance network" within Ukraine that would be able to take over if and when the military had failed, the official said. Before the invasion, the US anticipated the insurgency would emerge, coupled with guerrilla warfare, after a brief period of intense fighting in which Russia prevailed. But the war has now dragged on for months, with many analysts predicting a far lengthier conflict.

A senior US official warned a Russian counterpart before the conflict that they would face an insurgency if they invaded Ukraine and tried to occupy territory, the official said. But the warning fell on deaf ears and the invasion proceeded, driven in part by hubris and bad intelligence.

Russia believed its forces would be greeted with open arms and would crush any resistance quickly, erroneous fantasies that fell apart quickly but did little to change Russian President Vladimir Putin's calculations.

Kofman says it's unclear what type of governing framework Russia will try to create to exert control, but there is no doubt that it intends to retain the territories. After facing prolonged, bloody insurgencies in Afghanistan and Chechnya, the Kremlin knew to anticipate another potential insurgency in Ukraine.

"They did see it coming," Kofman said. "That's why they set up filtration camps and shipped out a lot of the population out of occupied areas."

The Tesla workers said they were subjected to offensive racist comments and behaviour by colleagues, managers, and human resources employees on a regular basis, according to the lawsuit filed in a California state court. (photo: Mike Blake/Reuters)

The Tesla workers said they were subjected to offensive racist comments and behaviour by colleagues, managers, and human resources employees on a regular basis, according to the lawsuit filed in a California state court. (photo: Mike Blake/Reuters)

Some plaintiffs were assigned to the most physically demanding posts or passed over for promotion, the lawsuit said.

The workers said they were subjected to offensive racist comments and behaviour by colleagues, managers, and human resources employees on a regular basis, according to the lawsuit filed in a California state court.

The harassment, which occurred mostly at Tesla’s Fremont, California factory, included using the terms “nigger”, “slavery” or “plantation” or making sexual comments such as “likes booty”, the lawsuit said, adding that the car maker’s “standard operating procedures include blatant, open and unmitigated race discrimination”.

Some of the plaintiffs were assigned to the most physically demanding posts in Tesla or passed over for promotion, according to the lawsuit.

It said that Montieco Justice, a production associate at Tesla’s Fremont factory, was immediately demoted upon returning to Tesla after taking an authorised leave of absence as a result contracting COVID-19.

Tesla did not immediately respond to a Reuters news agency request for comment.

The car maker is facing at least 10 lawsuits alleging widespread race discrimination or sexual harassment, including one by a California civil rights agency.

It previously has denied wrongdoing and said it has policies in place to prevent and address workplace misconduct.

On Monday, a federal judge in California ordered a new trial on the damages Tesla owes to a Black former factory worker who accused the company of race discrimination, after he turned down a $15m award.

This month, a Tesla shareholder filed a lawsuit accusing CEO Elon Musk and the company’s board of directors of neglecting worker complaints and fostering a toxic workplace culture.

A Russian serviceman keeps watch in front of a wheat field near Melitopol, Ukraine, on June 14. (photo: Sergei Ilnitsky/EPA)

A Russian serviceman keeps watch in front of a wheat field near Melitopol, Ukraine, on June 14. (photo: Sergei Ilnitsky/EPA)

Exclusive: António Guterres says growing north and south divide is ‘morally unacceptable’ and dangerous

The global food, energy and financial crises unleashed by the war in Ukraine have hit countries already reeling from the pandemic and the climate crisis, reversing what had been a growing convergence between developed and developing countries, António Guterres said.

“Inequalities are still growing inside countries, but they are now growing in a morally unacceptable way between north and south and this is creating a divide which can be very dangerous from the point of view of peace and security.”

Guterres, who spoke to the Guardian at the UN ocean conference in his home town of Lisbon in Portugal this week, said his biggest concern was how global problems were widening the gap between rich and poor.

“What is worrying is we are living in a perfect storm. Because all crises are contributing to the dramatic increase in inequality in the world and to a serious deterioration in living conditions of the most vulnerable populations.

“All these escalated a situation in which a world that was looking like it was converging between developing countries and developed countries, even if inequality were growing within countries north and south. Now we are back to a divergence.”

Earlier this month, the head of the UN’s World Food Programme warned dozens of countries dependent on wheat from Russia and Ukraine risked protests, riots and political violence as global food prices surge.

Of all the crises facing the world the climate crisis was the most vital, Guterres said.

“That is why it is so concerning that the war in Ukraine has to a large extent kept out the focus on climate action. We need to do everything we can to bring again the climate issue as the most important issue in our collective agenda. It’s more than the planet, it is the human species that is also at risk.”

While many important topics were addressed at the Cop26 UN climate conference in Glasgow last November, the central question of how to reduce emissions was not seriously discussed and continues to be ignored, he said. There was agreement, he said, that to keep warming down to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, deep cuts of 45% in emissions by 2030 compared with 2010 levels were needed. But we are moving in the wrong direction, he added.

“The truth is that if we look at the national determined contributions we have today and what was announced before during and immediately after Cop we are still moving into an increase of emissions of 14%.

“We have the risk of sleepwalking into the killing of the 1.5C goal.

“Something is being done, but it is too little too late. If we want to keep 1.5 alive we need to have a massive determination to reduce emissions as quickly as possible.”

All indicators suggest the effects of the climate crisis are accelerating faster than the worst predictions of a few years ago, he said.

Earlier this month, Guterres hit out at fossil fuel companies, describing them and the banks that finance them as having “humanity by the throat” and castigated governments that failed to rein in fossil fuels and were in many cases seeking to increase production of gas, oil and even coal, the dirtiest fossil fuel.

Asked about the backsliding of EU countries that have announced plans to reopen coal-fired power stations in response to Russia’s restrictions of gas flows into Europe, Guterres said: “Coal is enemy number one of climate action.”

The UN secretary general has called on Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries to phase out all coal plants by 2030 and other countries by 2040.

“I hope these examples of countries where some coal will be burned will be for a very short period,” he said

Germany, a country heavily reliant on Russian gas, announced it would reopen mothballed coal-fired stations to conserve its supplies, following Russia’s restrictions of gas flows. France has signalled it may reopen a coal station due to the situation in Ukraine.

Guterres said the war had highlighted our dependence on fossil fuels. “It is the instability in the fossil fuel market that is creating these dramatic impacts in rising energy prices and contributing to rising food prices and to the extremely difficult financial situation of many developing countries. If the world had invested massively as it should have had the past decade on renewables, we would today be in a completely different situation.” We need to learn lessons of the past, he said.

At the UN conference, attended by global leaders and heads of state, the heads of small island developing states such as Palau, Fiji and Tonga spoke of the devastating impact on their countries from increasing typhoons and sea level rise. The minister for climate change in Vanuatu, Silas Bule Melve, said the climate crisis was the single biggest threat” to the country’s efforts to expand its blue economy.

On Monday, Guterres declared the world was in the middle of an “ocean emergency” and condemned the “egoism” of some countries that were hampering efforts to reach a long-awaited treaty to protect the world’s oceans.

A longstanding promise, made in 2009 and brought to the fore at Cop26, from rich countries to provide £100bn a year in climate finance to the developing world has not yet been delivered.

Although this finance was a small part of what is needed, the failure to honour the promise of providing it, year after year, has added to the division between rich and poor countries, Guterres said. It “probably won’t happen in 2022”, he added. “This makes developing countries feel that there is indeed not a strong commitment of solidarity. Small island developing states feel it with particular intensity.

“There is a risk of the next Cop to be negatively impacted by this frustration of developing countries and lack of confidence and trust in the seriousness of the support of the developed world. And this would be tragic because we really need to mobilise everybody. We need everybody committed if we want to keep 1.5C alive.”

Asked what gave him hope, Guterres said he had met many young people in Lisbon, part of a youth forum aiming to develop ideas on solutions to the ocean and climate emergencies. Their depth of knowledge, clarity, commitment in their proposals and their enthusiasm “is my best hope”, he said.

“Young people are engaged. We see more and more cities, more and more civil society and even more areas of the private sector that are engaged. Governments are now becoming probably the entities that are moving more slowly.”

The U.S. once held a wealth of wetness, but the country's treasury has shriveled. (photo: Suzanne K. Mast Lee)

The U.S. once held a wealth of wetness, but the country's treasury has shriveled. (photo: Suzanne K. Mast Lee)

Wetlands absorb carbon dioxide and buffer the excesses of drought and flood, yet we’ve drained much of this land. Can we learn to love our swamps?

When I was ten years old, my family lived in a rented house in Rhode Island. Saturdays were free time, and I sometimes went to a nearby swamp. A fishermen’s path circled the swamp. Far out in the water stood the unreachable hulk of a dead tree—branchless, tall, white, and with a large hole near the top. I had somewhere read that great blue herons nested in such snags, and that in one swamp a man had brought a ladder, placed it against a tree, and climbed up to look into a heron nest. The heron stabbed him in the eye as he came level with the nest, and the man, his eye and brain pierced, fell dead from the ladder. I wanted to see if there was a heron nest in this local swamp’s dead tree—perhaps even a live heron, perhaps even the remains of a ladder, perhaps even a sun-bleached skull nearby. When I got to the swamp, I saw a small raft and a pole lying on the bank. There was no one around. I pushed the raft out into the tawny water, got on board, and began poling toward the snag. I was halfway there when I heard furious shouts and screams. Looking back, I saw the two worst boys at my school jumping up and down on the bank and hurling futile clods of mud. I had stolen their raft. After a quick look for a hiding place, I changed direction and took an oblique route to the farthest shore, where I pole-vaulted onto firm land, found the path, and rushed away from the scene of the crime. It was some time before I noticed that I was still carrying the raft pole, and I leaned it helpfully against a tree before continuing home.

Many modern Americans do not like swamps, herons or no herons, and experience discomfort, irritation, bewilderment, and frustration when coaxed or forced into one, except for a few, like my mother, for whom entering a swamp was like plunging into a complex world of rare novelties. My mother’s hero was Henry David Thoreau, the enigmatic New England surveyor-naturalist-essayist. Thoreau has been called the patron saint of swamps, because in them he found the deepest kind of beauty and interest. He wrote of his fondness for swamps throughout his life, most feelingly in his essay “Walking”: “Yes, though you may think me perverse, if it were proposed to me to dwell in the neighborhood of the most beautiful garden that ever human art contrived, or else of a Dismal Swamp, I should certainly decide for the swamp.” He went so far as to describe his dream house as one with windows fronting on a swamp where he could see “the high blueberry, panicled andromeda, lambkill, azalea, and rhodora—all standing in the quaking sphagnum.”

Many people vaguely understand that wetlands cleanse the earth. In fact, they are carbon sinks that absorb CO2, and they are unparalleled in filtering out human waste, material from rotten carcasses, chemicals, and other pollutants. They recharge underground aquifers and sustain regional water resources, buffering the excesses of drought and flood. In aggregate, the watery parts of the earth stabilize its climate.

Wooded swamps are at the end stage of a fen-bog-swamp succession, legacies of the Ice Age, when the melt started the sequence by first creating stupendously huge lakes. Lake Agassiz covered more than a hundred thousand square miles of Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, North Dakota, and Minnesota. Lake Missoula covered about three thousand square miles of what is now Montana; its repeatedly bursting ice dams and cataclysmic floods spread through Idaho and Washington and created bizarre giant ripples as the long-ago gushers scoured out the channelled scablands of eastern Washington. The melt turned much of the North American continent into wet ground, with long chains of swamps gouged by no-brakes glaciers that plowed across the terrain. Burly new watercourses captured smaller streams and made deltas and estuaries.

In the nineteenth century, the United States enlarged in a fever of land acquisition: the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, involving eight hundred thousand square miles from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada, doubled the size of the country; in 1819, the Adams-Onís Treaty added Florida and part of Oregon; five hundred and twenty-five thousand square miles of Texas were annexed in 1845; the Oregon Treaty, in 1846, enrolled the Pacific Northwest from Northern California to the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Great oceans and lakes framed the country, and the interior roiled with tangles of rivers like unspooling silver ribbons. All that territory had once held a wealth of wetness—scientists have estimated that approximately two hundred and twenty-one million sopping acres existed in the early seventeenth century, much of it swamps—and two hundred years later many swamplands remained. As the United States pushed its borders, its population leaped from 7.2 million people in 1810 to 12.8 million by 1830, almost doubling in twenty years. The welcoming arms of open immigration became the hallmark of America, and that reputation lingers in global memory, despite today’s more painfully stringent reality.

The original occupants of the continent knew the rivers and swamps, the bogs and lakes, as they knew the terrain and one another. But for most English settlers and European newcomers nature consisted of passive and inanimate substances and situations waiting to be used to human advantage. Preservation and care of nature were not what they had come for.

The first generations of overseas settlers concentrated on claiming the easiest farmland near the shore and in the river valleys. To their mind, there were no local resources. Everything had to be imported or reinvented. As invaders, they had constant battle with Indigenous people who defied them. It was not until the Revolutionary War ended and the Indian Wars devolved into treaty-making that the population noticeably increased and a need for more farmland brought settlers into the upland forests. The growing scarcity of good farmland revived old stories of swamp and marsh drainage. Farmers already knew that a wagonload of “muck” from a nearby swamp would enrich the soil, renewing yields that had weakened over the years. In addition, during the Civil War, moving heavy guns and personnel through swamps was incredibly difficult; soldiers often resorted to laboriously clearing bypass routes. One of the men wrote of wading through knee-deep and deeper mud in North Carolina after the battle of First Gum Swamp: “The brambles [were] thick and thorny, the water coffee-colored, alive with creeping things, the air heavy with moisture and foul odors.” These memories persisted. Across the country, the ongoing stories of vile adventures in the muck made it clear to military, government, and citizenry that something had to be done about the swamps so universally detested. Everywhere there were horrendous mixtures of fen, bog, swamp, river, pond, lake, and human frustration. This was a country of rich, absorbent wetlands that increasingly no one wanted.

After a rainstorm, any curious child who drags a stick obliquely away from a rivulet sees the rivulet forsake its original channel and follow the stick’s trail; the stick dragger has discovered the principle of drainage. It is this innate existential curiosity that has led humans to commit unthinking malfeasances against the natural world. Farmers grew up with shovel in hand ready to cut drainage ditches. The government was solidly on the side of drainage to increase land area, in part for incoming immigrants. In 1849, Congress passed the first of several swampland laws that turned federal wetlands over to the individual states with the right to dispense those water-sodden acreages for purposes of drainage. These laws perpetuated the myth of endless land free for the taking, and showed an inability or an unwillingness to observe changes in nature over the seasons and years.

By the nineteen-eighties, roughly half of America’s wetlands had been wiped out. Aerial photography made wetland size estimates possible, and in 1990 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service published a study showing that since the sixteen-hundreds the country’s treasury of wetlands had shrivelled to a hundred and three million acres, and that some states had lost almost all their original wetlands.

The single-minded desire for more agricultural land linked to automation and the transfer of field labor from human to machine, along with the growing customer base of non-farming populations for cheap foods and grains, has come with a terrible cost. Between 2004 and 2009, another sixty-two thousand three hundred acres of wetlands disappeared to agricultural interests and housing developers. And more continue to disappear because of sediment-deposition patterns; fertilizer runoff; spilled and leaking chemicals; increasing floods, storms, droughts, and fires; and today’s rising sea level.

Rising sea level is both subtle and blatant: we hardly notice it until a storm brings vast flooding. For example, at Naval Station Norfolk, in the Hampton Roads region—a natural roadstead channel of deep water in Chesapeake Bay, fed by the James, Nansemond, and Elizabeth Rivers—seawater is now swelling up at an unprecedented rate. The environmental writer Jeff Goodell visited the station and wrote, “There is no high ground on the base, nowhere to retreat to. It feels like a swamp that has been dredged and paved over—and that’s pretty much what it is.”

It is in and around wetlands that the greatest blossoming of biodiversity has occurred—it is not too much to say that we owe our existence to this planet’s wetlands, including fens, bogs, and swamps. Our wholesale destruction of wetlands for the sake of a few decades of growing wheat, rice, soy, and palm oil has been breathtakingly short-sighted. Once again, we are shocked into recognition that most of us live only for the moment.

The great Southern coastal swamps of the United States were and are treasures of the natural world. Some have been exploited and damaged beyond recognition; some are still rich and wonderful, preserved as wildlife refugia or parks. Visitors can share the amazement and delight of the botanist William Bartram, whose exploratory travels in Georgia and Florida between 1765 and 1776 yielded writings and drawings that show a wild, tropical South—warily sensitive Seminoles, violent and crafty alligators, exquisite unnamed flowers, masses of bayonet-like grasses, colossal black oaks. Every fly-fisher will appreciate his description of the mayfly hatch:

Innumerable millions of winged beings, voluntarily verging on to destruction, to the brink of the grave, where they behold bands of their enemies with wide open jaws, ready to receive them. But . . . gay and tranquil each meets his beloved mate in the still air, inimitably bedecked in their new nuptial robes. What eye can trace them, in their varied wanton amorous chaces, bounding and fluttering on the odiferous air!

Bartram was the son of the Philadelphia Quaker John Bartram, who had been appointed Botanist for the American Colonies by George III. John Bartram made the country’s first botanical garden on his Philadelphia property. Father and son often went on botanical expeditions together. One such was to Georgia’s lower Altamaha, where in 1765 they first discovered the Franklinia, in a sandhill bog. This small, beautiful tree is now extinct in the wild but continues to delight American gardeners, who grow specimens all descended from those few seeds collected by William Bartram on his Georgia travels. Thinking of the Bartrams, I once planted the closely related Stewartia in my garden, while I was living in Port Townsend, Washington; it grew handsomely but did not flower during my time there.

A valuable medicinal plant was the Bartrams’ second find. “It grows twelve or fifteen feet high,” William Bartram wrote, “with large panicles of pale blue tubular flowers, specked on the inside with crimson.” This was Pinckneya pubens, the Georgia “fever tree,” a natural source of quinine used by Native Americans to treat tick fever, muscle cramps, parasites, and malaria.

At times, the travels were dangerous or pestiferous, as when Bartram fell asleep next to his campfire to enjoy “but a few moments, when I was awakened and greatly surprised, by the terrifying screams of Owls in the deep swamps around me . . . which increased and spread every way for miles around, in dreadful peals vibrating through the dark extensive forests.” This past spring, in New Hampshire, I heard amorous owls similarly whooping and caterwauling in the woods. One of Bartram’s more admirably descriptive passages pinpoints the belligerence of the “subtle greedy alligator”:

Behold him rushing forth from the flags and reeds. His enormous body swells. His plaited tail brandished high, floats upon the lake. The waters like a cataract descend from his opening jaws. Clouds of smoke issue from his dilated nostrils. The earth trembles with his thunder. When immediately from the opposite coast of the lagoon, emerges from the deep his rival champion. They suddenly dart upon each other. The boiling surface of the lake marks their rapid course, and a terrific conflict commences. They now sink to the bottom folded together in horrid wreaths. The water becomes thick and discolored. Again they rise. . . . Again they sink.

The American biologist and ornithologist Brooke Meanley, who died in 2007, knew intimately every swamp corner that the Bartrams had visited two centuries earlier. He spent most of his professional life in the Southern swamps. Born in Maryland in 1915, and educated at the University of Maryland, Meanley worked as an ornithologist for the Department of the Interior. In his work, he took thousands of pictures of swamp habitats and birds—including many that no longer exist.

During the Second World War, he served for four years, and was stationed in Georgia, rehabilitating returning soldiers with damaged bodies and psyches. His way was to take the jittery men on hikes and bird walks through nearby forests and swamps. One can only guess how many bird-watchers and amateur naturalists found mental balance and lifelong interests in the natural world through these expeditions. Certainly they learned from him that cutting old-growth forests removed vital bird habitat.

Meanley’s years in and around the Southern water lands are encapsulated in his book “Swamps, River Bottoms and Canebrakes.” I had never heard of the Slovac Thicket until I read Meanley’s description: “For its size, the fourteen-acre Slovac Thicket, located in the heart of the Grand Prairie near Stuttgart, Arkansas, packed the most wildlife excitement per acre that I have ever known.” It’s a good bet that a sky totally black with twenty million birds, such as he saw and photographed that day, cannot now be seen.

Swamps and birds go together; when the swamp disappears, so do the birds. The New World warblers (a.k.a. wood warblers), a group of about fifty small passerine birds that migrate from South and Central America to the boreal forests of Alaska and Canada, were Meanley’s favorites. Many are brightly colored, and their complicated high-pitched songs are difficult to hear. They flicker and flit through branches and reeds like sunlight on a windy day and are a challenge to see. In a perfect world, a warbler can live for a decade, but in the world of predatory house cats, wind turbines, and enormous glass buildings a warbler is lucky to live two years. Meanley found that the bottomlands of the I’On Swamp, in South Carolina, were a choice habitat for the Bachman’s warbler, once the seventh most common migratory bird, annually flying up from Cuba to breed in the blackberry swamps and cane thickets of the Southeast United States. The swamp, named for a landowner, Jacob I’On, was the hunting ground for an early American ornithologist, the Reverend John Bachman, who in 1833 first found the songbird. His friend John James Audubon listed the warbler in his “Ornithological Biography.” As other wetlands were drained and cut, warblers found a refuge in the I’On. Meanley counted himself fortunate to have twice seen a Bachman’s warbler in his lifetime—in 1958 and 1963. In his day, he knew that the species was near extinction. It has not been seen since 1988 and is now presumed to have joined the passenger pigeon and the ivorybill.

For Meanley, the prince of Southern swamps was the Okefenokee, which contained up to twenty-five feet of peat deposits, and was once a haunt of the ivorybill. In describing the swamp’s charms, he wrote that it had everything: “The live oak hammocks, alligators and large wading birds, and the legends. In my judgement it is the most picturesque swamp in North America.” It was, he observed, a mosaic of lakes, shrub bogs, and cypress heads and bays, and though much of its cypress had been cut in the early twentieth century, fifty years later, when he was back in the Okefenokee, lusty regrowth allowed him to say that the swamp “looks today as it did when it was the stronghold of the Seminoles and Creeks.”

When I was in my twenties, my then husband and I sometimes vacationed in the Georgia islands—St. Simons or Sea Island—and we went once to the Okefenokee for a motorboat outing. For hours, we prowled the dark water at low speed, bathed in the damp, heady Southern air that always made me happy when I stepped off the plane into its distinctive perfume. I could not count all the wading birds that stalked in the shallows like tall, aloof models. We glided past cypress and their peculiar pointy knees. Our guide said the knees breathed for the cypress. He pulled up to a small island and waved his hand with a grandiose gesture at the mossy ground. I stepped out of the boat and felt the ground move in an undulating roll. It was a mat of sphagnum moss, and although some people say it is like walking on a waterbed, its billowy heave seemed to me more like a wave of dizziness before you pass out—a very slow falling sensation although you remain upright.

My most intimate swamp experience came one summer when I lived in a remote and ramshackle house in Vermont with a beaver-populated swamp half a mile down in the bottomland. I went to the swamp almost every day by a circuitous route through the woods, passing a patch of pitcher plants and two or three sundews, across a brook, following the beavers’ tree-drag ruts to an old stick dam. There were trout in this swamp and beautiful painted turtles. I watched the amazing acrobatics of dragonflies with disbelief that they were actually doing what I saw them do. Even when I sat on the back porch high above the swamp I thought I could catch the green smell of bruised lily pads.

Once, after weeks away, I came back to the house in the late afternoon. I had started reading Norman Maclean’s story “A River Runs Through It” on the plane ride home and decided to read to the end before I went inside the house. It was an utterly quiet, windless day, the light softening to peach nectar. I read the last page and its famous final line, “I am haunted by waters.” I closed the book and looked toward the swamp. Sitting on a stone wall fifteen feet away was a large bobcat who had been watching me read. When our eyes met, the cat slipped into the tall grass like a ribbon of water, and I watched the grass quiver as it headed down to the woods, to the stream, to the swamp.

After the Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804-06 and the Erie Canal’s gradual opening from 1825 onward, the country’s swelling population pushed into the new Western territories. The Great Black Swamp, a product of the excess of mire left over from the glacial melting of the Ice Age-era Lake Erie, and which covered much of Ohio and parts of Michigan and Indiana, inspired visceral revulsion. The Black Swamp froze itself blue in winter and simmered under the summer sun. It was forty miles wide and a hundred and twenty miles long, an elm-ash watery woodland well stocked with snakes, wildcats, moose, birds, malaria-carrying mosquitoes, and unnamed demons, immovably in the way of all who were trying to go west. Travellers forced to splash through swamps under attack from blackflies, no-see-ums, and deerflies, or to make long, tiresome detours around watery areas, complained vociferously and called to the heavens for drainage.

By the eighteen-fifties, farmers noticed that raised stream banks in parts of the swamp were made of dry black soil. They picked up handfuls of it, rubbed it between their fingers, felt the friability and tensile strength, judged its tilth. Then they cut down the stream-bank trees, plowed and planted, and harvested tremendous crops. They said what every farmer in newly opened peatland has ever said as they gathered the first harvests: “This is some of the most productive soil on earth.” Other farmers noticed, and since stream-bank acres were limited, a few men with experience in wet soils tried drainage with ditches and tiles. Excited by their success, the farmers attacked the Black Swamp; a mad make-your-own-land rush was on. In the eighteen-eighties, an Ohio man, James B. Hill, frustrated by the slow work of laying drainage tiles, invented a machine he called the Buckeye Traction Digger. Every farmer wanted one, and the Black Swamp began to dry out.

Pro-drainage legislation helped the process along, and woe betide the landowner who resisted his neighbor’s drain work. In 1915, Ben Palmer of Minnesota wrote a legal guide to drainage. Chapter 4—“Drainage Legislation and Adjudication”—explains, “Thirty-six states of the Union have now enacted general drainage laws for the purpose of providing the legal machinery which is necessary if drainage work involving any considerable amount of land is to be successfully carried on.”

By the early twentieth century, only a pinch of the original Black Swamp still existed—the rest was “some of the most productive soil on earth.” It was taken as a stroke of luck that drainage tiles could be made from the clay deposits beneath the good peaty soil—in a way, the Black Swamp paid for its own annihilation. But a few generations later the productive soils were depleted; the nutrients in organic soils will disappear when they are not replenished. Manure grew scarce as tractors replaced horses. The farm world welcomed synthetic fertilizer. Time passed, and the Maumee River, which drains the Ohio cropland watershed, became a major source of pollution in Lake Erie. I was once on a train that stopped for hours on a bridge over the Maumee River to let freight traffic through. There was no sign—frothy scum, iridescent gloss, or bright algae—to show that just below the train flowed Lake Erie’s poison enemy.

Aside from the joys of draining, there was another pot of gold at the end of the swamp: fortunes for the nineteenth-century woodland owners and professional timbermen who cut down the wetland forests not only of Ohio but of Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Georgia, Louisiana, Florida, and any other state north or south that had swamp forests—taking irreplaceable giant elm, ash, oak, birch, poplar, maple, basswood, hickory, and chestnut.

Ohio residents, by and large, did not appear to miss their state’s swampland. Sharon Levy, a science writer who specializes in water and wetland issues today, wrote of the mark the Black Swamp made on Ohioans:

The tough people who conquered the Great Black Swamp did so at great personal expense, and they’ve passed down a deep and abiding loathing of wetlands. They are considered a menace, a threat, a thing to be overcome. These attitudes are enshrined in state law, which makes impossible any action, including wetland restoration, that slows the flow of runoff through those miles of constructed drainage ditches—the very conduits that, after each heavy rainfall, deliver thousands of metric tons of phosphorus and nitrogen to the Maumee, and onward into Lake Erie from which millions of people drink.

One authority on water, William Mitsch, has suggested that if ten per cent of the old Black Swamp soils were allowed to become wetlands again they would cleanse the runoff, yet Ohioans remain powerfully anti-wetland. Even private efforts to restore small wetland areas are met with neighbors’ complaints about noisy frogs and fears of flooding. Still, despite all odds, there exists the Black Swamp Conservancy, a land trust that oversees twenty-one thousand acres of wetlands. Hundreds of active Black Swamp Conservancy members are doing their best to restore and protect remnants of this great swamp. Can they persevere?

My mother’s favorite book when she was a teen-ager, in the nineteen-twenties, was one that she loved for its swamp setting, Gene Stratton Porter’s “A Girl of the Limberlost.” The Limberlost Swamp is in northeast Indiana, forty miles west of the Great Black Swamp. Porter’s home was near the Limberlost, which, though small at thirteen thousand acres, was still a diverse and complex system of streams and ponds eventually draining into the Wabash River. The Limberlost was made up of timber, reeds, sphagnum moss, orchids, sundew, pitcher plants, and grasses that nurtured great crowds of waterbirds and migratory birds, snakes, frogs and other amphibians, deer, muskrat and beaver, mink, and an encyclopedia of insects, including rare moths and butterflies.

There are at least two and probably more stories of how the name Limberlost originated. In one, a man named James Miller, so physically agile he was called Limber Jim, was hunting in the swamp. He became hopelessly lost, walking in deadly circles before he began to blaze trees in a straight line. His friends found him and referred to the swamp ever after as the place where Limber was lost. Another story refers to Limber Jim Corbus (what is it with these flexible Indiana men?), who also set out for a day’s hunt in the swamp and became lost, but blazed no trees and was never found.

Despite being considered a “nature” novel, “Girl of the Limberlost” is the usual American story of taking from nature for personal gain. The book champions its heroine, Elnora, who collects the chrysalides of moths, then raises, kills, and mounts them. After her miserable first day in high school, where she is scorned as an out-of-fashion backwoods hick, she sees a placard in the local bank window offering cash for moths, cocoons, and pupa cases. Elnora needs money to buy the kind of nice clothes and cosmetics that will let her join modish high-school cliques and pay for her books. She describes her moths to the placard’s writer, who tells her, “Young woman, that’s the rarest moth in America. If you have a hundred of them they are worth a hundred dollars according to my list.” Elnora is on her way to wealth, a career, a rich husband, and all the rest of it, thanks to the corpses of the Yellow Emperor moth.

Against Porter’s protests, the Limberlost was ruinously drained for farmland by steam-powered dredges between 1888 and 1910. But in the nineteen-nineties Indiana readers who treasured Porter’s book bought some of the original swamp acreage and, with help from several conservation groups, started restoring the swamp by removing drainage tiles. As the water deepened, they planted native sedges, grasses, trees, and water plants. Today, a small piece of the Limberlost exists again, serving as a tourist attraction and a home to muskrats, ducks, herons, turtles, fish, and insects. The Yellow Emperor moths are still around.

It is an important decision to restore even a small piece of wetland that has been severely mauled—once land is apportioned to owners, there can be no easy path to restoration of a natural habitat. Bogs and swamps take thousands of years to build up and develop; humans and their machinery can wipe out those centuries in a few months. But once a few interested people put on their boots and go into the damaged wetland, and once their curiosity is aroused about how the water moves, and what plants, amphibians, and birds formerly thrived in their local remnant swamp, they are hard to stop. There is unequalled joy in restoration.

Mangroves are marine trees. They grow in brackish and saline water along Southern and tropical shores—their splayed-out roots resemble the “cages” that supported Victorian hoop skirts—and they form peat. Their specialized home ground, such as Florida’s Everglades, is smelly and muddy. There are roughly sixty species of mangrove, mostly found in Asia, and the strongest forests are those of mixed species. Mangrove swamps have been called the earth’s most important ecosystem, because they form a bristling wall that stabilizes the land’s edge and protects shorelines from hurricanes and erosion, and because they are breeding grounds and protective nurseries for thousands of species, including barracuda, tarpon, snook, crabs, shrimp, and shellfish. They take the full brunt of most storms and hurricanes, and generally survive—but not always. Hurricane Irma, in 2017, hit the mangroves of Big Pine Key, in Florida. While shrubs came back after a time, the mangroves did not. Some saw the cause of mangrove death as trapped standing salt water, but others thought that the storm surge had plastered a very fine coating of sediment on the vital aerial roots, which dried into a choking hard sealant.

Mangrove leaves fall into the water and, as they decay, become the base for a complex food web benefitting algae, invertebrates, and the creatures who feed on them, such as jellyfish, anemones, various worms and sponges, and birds. The peat that mangroves form is especially soft and deep, ideal for clams and snails, crabs and shrimp. The mangrove’s roots filter out harmful nitrate and phosphate pollutants. The tangled branches above the water make a safe habitat for literally thousands of species of insects that attract birds. They offer resting places for migrating birds and nesting places for others, including kingfishers, herons, and egrets. Monitor lizards, macaque monkeys, and fishing cats on the hunt prowl the branches. Below the water, the knots of interlaced roots protect tiny fish from the ravenous jaws of larger fish, and even manatees and dolphins take refuge in these swamps. Mangroves interact with coral by trapping muddy sediment that would smother the reef, while the offshore reef protects the mangroves and seagrass beds from pummelling waves. Structurally, mangroves form an enormous hedge that extends down into the water and high above it. They are a major part of the “blue carbon” group that absorbs CO2, which also includes the salt marshes, seagrasses, and beds of kelp and other seaweeds.

With all these virtues, it would seem that mangroves must be the most valued trees on earth. Unfortunately, that is not the case. Although climate researchers see mangrove swamps as crucially important frontline defenses against rising seawater and as superior absorbers of CO2—they are five times more efficient than tropical forests—they are in big trouble, and mangrove removal is a constant threat.

In 2010, a count showed that about fifty-three thousand square miles of mangrove forest protected the earth’s coasts. But six years later thirteen hundred square miles of mangroves had been lost to palm-oil and rice farms and shrimp aquaculture. In some cases, mangrove forests have been removed to make room for shrimp ponds; in other cases, the shrimp ponds are set back from the mangroves, but the released effluents and pollution still damage and degrade the mangrove forest by changing the water’s salinity, altering the mangrove’s ability to take in nutrients. The consequence is slow death for the mangroves.

Many countries have tried to master the complexities of mangrove restoration, with mixed results. Choice of the right site and a mutually beneficial mix of species is critical. Some well-intentioned restorers planted greenhouse-raised single-species saplings in mudflats that mangroves had never grown in, or that were exposed to erosion and strong waves. Yet mudflats have a low oxygen supply because they are constantly wet, and mangroves need to breathe.

A different approach was that of the Florida biologist, ichthyologist, and wetlands ecologist Roy (Robin) Lewis III, who worked out the details of effective mangrove restoration. Repetitive observation can unravel the mysteries of events and processes. Lewis, who was born in 1944, was still a graduate student when he began working in mangrove swamps. “I spent a decade working in the mangroves before I started to have an understanding of what was going on,” he once remarked. He dedicated years to puzzling out the rhythms of mangrove happiness. He observed that, in the natural order, when a mangrove tree died, plentiful seeds from nearby healthy mangroves floated in and rooted themselves. The problem with many restoration attempts was location. Just any random part of a shoreline would not work. The flow of water had to be correct. Mangrove roots need to be sometimes wet and sometimes dry. Lewis worked out a wet-dry ratio of thirty to seventy. “They have a short period of wetness, and then they have a long extended period of dryness, and those alternate daily,” he told a reporter for the Smithsonian Institute. “That’s the secret: you’ve got to replicate that hydrology.”

His first trial of this theory came in 1986, with thirteen hundred acres of damaged and dead mangroves half smothered in dirt and weeds on a flat site near Fort Lauderdale. After several years of experiment and study, Lewis brought in earth-moving equipment to create a gentle slope of land that would allow the natural tidewaters to ebb and flow. Then he waited. The tides brought mangrove seeds that took root, and five years later three local species of mangroves were growing. Fish moved into the sheltering roots, and the birds followed. No mangrove saplings were hand-planted; all the new trees grew from waterborne mangrove seeds. Lewis’s way of working with nature—observation and study, planning and patient waiting—has become the gold standard for restoration.

It is usual to think of the vast wetland losses as a tragedy, with hopeless conviction that the past cannot be retrieved. Tragic, indeed, and part of our climate-change anguish. But as we learn how valuable wetlands are in softening the shocks of the changing climate, and how eagerly the natural world responds to concerned care, perhaps we can shift the weight of wetland destruction from inevitable to “not on my watch.” Can we become Thoreauvian enough to see wetlands as desirable landscapes that protect the earth while refreshing our joy in existence? For conservationists the world over, finding this joy is central to having a life well lived.

It is of course possible to love a swamp. I remember another small and nameless Vermont larch swamp, which could be reached only by passage through a dark and gloomy ravine that I thought of as the Slough of Despond.

At the bottom of the ravine ran Jacobs Chopping Brook. The flurried, emotional water of the brook contrasted with the black glass disk of swamp water that seemed made to reflect passing clouds but under rain showed itself as dimpled pewter. It has been fifty years since I last saw it, but it is still with me.

...they paved paradise and put up a parking lot...

Mitchell said this about writing the song to journalist Alan McDougall in the early 1970s: "I wrote 'Big Yellow Taxi' on my first trip to Hawaii. I took a taxi to the hotel and when I woke up the next morning, I threw back the curtains and saw these beautiful green mountains in the distance. Then, I looked down and there was a parking lot as far as the eye could see, and it broke my heart...this blight on paradise. That's when I sat down and wrote the song." The song is known for its environmental concern -- "They paved paradise to put up a parking lot" and "Hey farmer, farmer, put away that DDT now" -- and sentimental sound. The line "They took all the trees, and put 'em in a tree museum / And charged all the people a dollar and a half(twenty five bucks) just to see 'em." refers to Foster Botanical Garden in downtown Honolulu, which is a living museum of tropical plants, some rare and endangered.

Special Coverage: Ukraine, A Historic Resistance

READ MORE

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.