How Chesa Boudin’s life made him a lightning rod for the progressive prosecutor movement

Chesa Boudin and Lorenzo Charles became friends during monthly visits to their mothers in a maximum-security prison.

Lorenzo’s mother was behind bars for a relatively minor drug offense; Kathy Boudin, a leader of the radical Weather Underground, was doing 20 years to life for her role as an unarmed getaway driver in a 1981 Brinks robbery near New York City that ended with three dead.

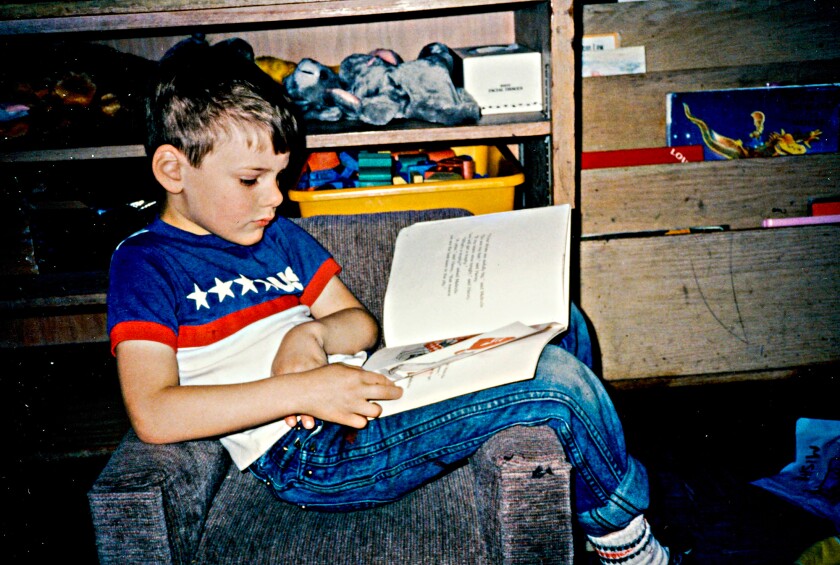

When 6-year-old Chesa screamed at his mother for abandoning him as an infant, Lorenzo calmed him. When Chesa refused to do homework, his mother urged him to emulate Lorenzo, an A student who lived with his grandmother in a tough Brooklyn neighborhood.

Chesa lived in Chicago with his adopted family of activist intellectuals. With their support, he channeled his anger into achievement. He lost touch with Lorenzo. In his first semester at Yale, Chesa received a letter from his father, imprisoned for his role in the Brinks robbery. He had met Lorenzo on his cell block. Doing time for burglary.

It’s a story so central to Boudin’s life that he tells it over and over, always with the same last line: For Lorenzo, “the odds played out.”

Lorenzo’s fate drew Boudin to research and write about those odds against children of incarcerated parents, which deepened his convictions about injustice and racism, which propelled him to law school and a job as public defender in San Francisco.

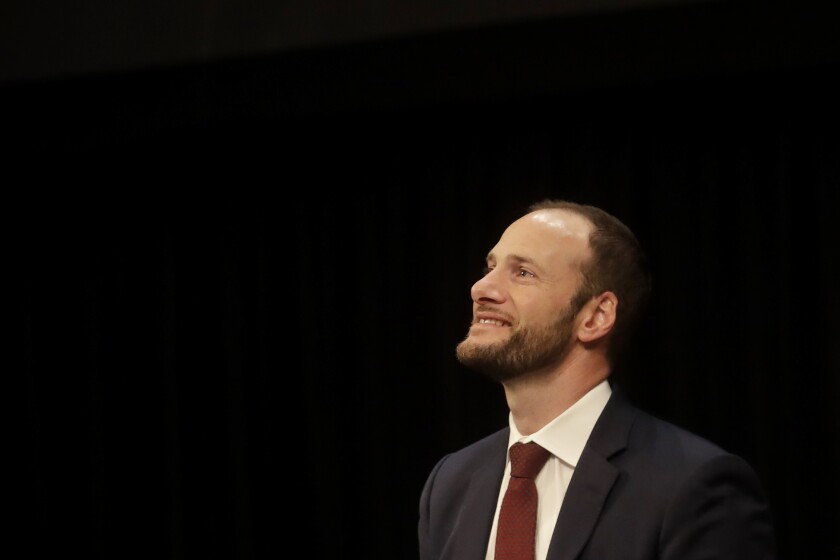

And then he made a move in some ways as radical as his parents’ choices: In 2019, he ran for San Francisco district attorney, promising to use incarceration as a last resort, tackle systemic racial inequities and prosecute police brutality.

Everything about his victory was improbable. He was a 39-year-old public defender who had never prosecuted a case. In a city where politics is a blood sport, he was a candidate who had never run for anything since class vice president in sixth grade. His four parents, the two who bore him and the two who raised him, had been faces on FBI Most Wanted posters.

Opponents registered the domain name recallchesaboudin.org within days of his being sworn in. Fueled by tech money, fears of crime, and San Francisco politics, the June 7 recall election has made Boudin a lightning rod for every tragedy in the city, the target of anger over homeless encampments, drug dealing, gun violence and home burglaries.

San Francisco voters’ verdict on Boudin will reverberate far beyond the city’s 47 square miles, including in Los Angeles, where Dist. Atty. George Gascón faces a potential recall. Because if you can’t make radical change in San Francisco, what future does the progressive prosecutor movement have?

Two months after he took office, Boudin spoke at a Columbia University conference that focuses on ending mass incarceration. In the front row was his mother, Kathy, paroled in 2003, doctorate in education in 2007, founder of the center that organizes the annual event.

“I never wanted to run for office,” Boudin said. “Because of the compromise. Because of the mucky, disgusting policymaking process. The moral clarity of being a public defender was safer, was easier.... But I found myself, I think we all find ourselves, in a pretty unique historic moment.... And now I face the slippery slope of compromise. Every day.”

When he stood up in court, which he did often, he was clear what “for the people” meant: “A lot of people in my role don’t think that ‘the people’ include those they are prosecuting.”

He was trying to disrupt the paradigm that divides the world into good victims and bad criminals, that equates locking people up with public safety, that measures success by convictions. He was trying to redefine success as interventions that healed victims and held criminals accountable, yet offered a path to redemption.

He hired former public defenders in top jobs to “bring people into the office who don’t just theoretically know that the person they’re prosecuting is a three-dimensional person … who have seen racial profiling and what it looks like in police reports. Seen people who are wrongfully accused.”

He was trying to convince career prosecutors that they had been wielding their enormous power wrongly.

“They don’t want to believe that for their entire life, their entire career, they’ve been doing harm,” he said months later at a symposium. “They don’t want to believe that an outsider like me, a career public defender, knows better than they do how to be a prosecutor, or how to be a prosecutor that helps promote public safety.”

This, more than any specific reform, has made him a polarizing figure, loved and reviled, savior and threat.

“I just want to live in a city where the DA prosecutes crime,” tweeted Michelle Tandler, an entrepreneur and recall supporter. “My home has been overrun by radicals and the criminals they empower.”

The COVID-19 pandemic bred insecurity and fear, addicts and homeless stood out on empty San Francisco streets, home burglaries surged as tourists vanished and tech workers left the city, and Boudin’s past, which shapes all that he does, was reduced to a simple refrain: son of terrorists.

::

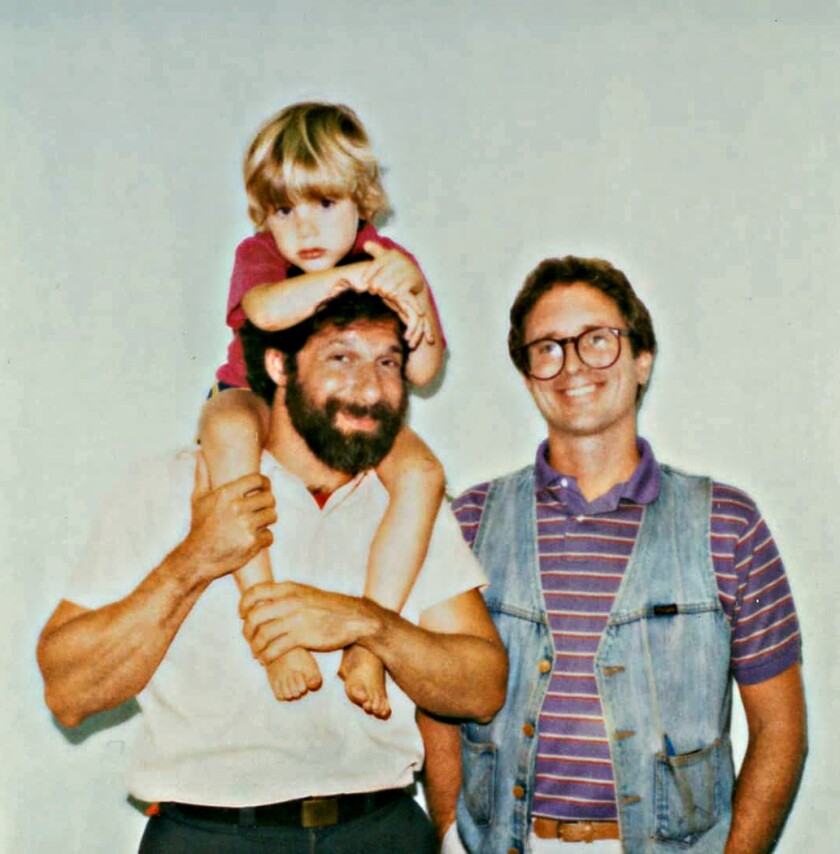

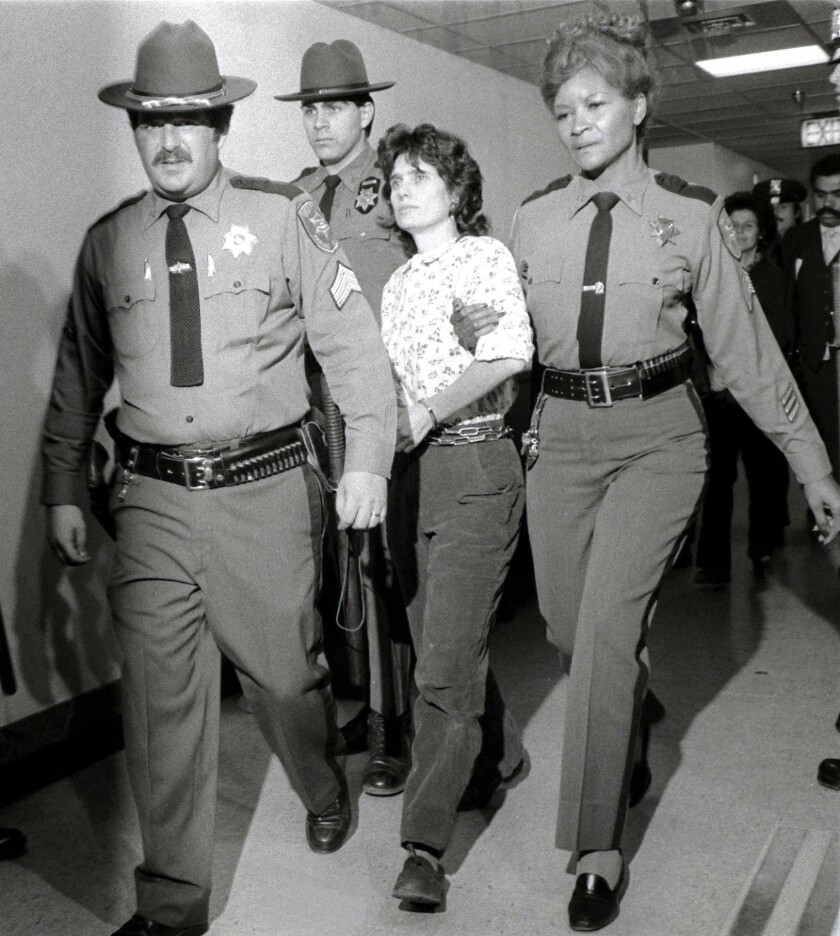

On Oct. 20, 1981, Kathy Boudin dropped her 14-month-old son at the babysitter and joined his father, David Gilbert, assigned to pick up members of the Black Liberation Army after they robbed a Brinks truck in a suburban mall.

The plan went awry; Black revolutionaries shot and killed a Brinks guard and two police officers. Boudin and Gilbert were arrested at the scene.

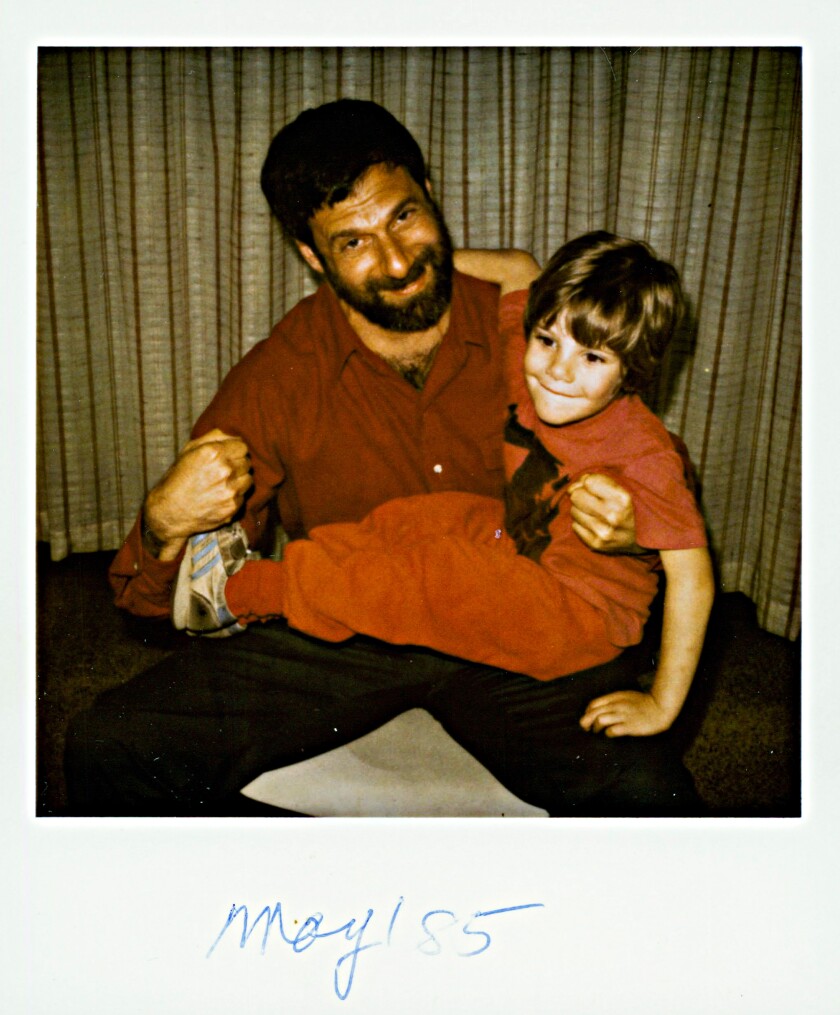

Chesa was adopted by Bill Ayers and Bernardine Dohrn, friends of his parents from the movement. By 7, he was flying solo more than a dozen times a year from their Chicago home to New York for prison visits.

“We’d be going about our lives, and then Chesa would be gone for four days,” said Sam Kass, a close friend since childhood. “He would go off into this other world and then come back to ours. And we’d be running around and riding bikes.”

By junior high, years of therapy helped channel his rage and guilt into ambition and achievement. “It was a very conscious decision,” Kass said. “He just worked harder at everything than everybody in everything he did. Whether he was good at it or not.”

He was the A student who read the most books, the multitasker who editorialized against the abolition of a free period, which he used to email family, eat, talk to teachers, get library books, make photocopies, attend club meetings and catch up on “those little things adults call errands.”

His nickname was the Shark: Always moving, or you die.

In a home that was a salon for children as well as adults, Chesa developed both a hard shell and an outspoken sense of injustice.

When teachers told him to wear a name tag the first day at school, Chesa threw such a fit that Ayers had to intercede. The problem was not the name tag, but the itchy yarn around his neck, Boudin recalled in an interview. Thirty-three years later, righteous indignation still tinged his voice:

“I wasn’t being rebellious for the sake of being rebellious. I was uncomfortable.”

He embraced, first by necessity and then by choice, a life that straddled two worlds.

“Every day I combine two lives: one immersed in the stability of privilege and the other meeting the challenges of degradation,” Boudin wrote in his college application essay.

Reconnecting with Lorenzo Charles became the impetus for research on the rights of children of incarcerated parents and the biases of a system that disproportionately locks up Black men.

Boudin spoke around the country with a friend whose father had been a leader of the Attica prison rebellion.

“I would be the one who would be emotional,” Emani Davis said. “And he would stick to all the points.”

Boudin’s first new program as district attorney allowed parents charged with certain low-level crimes to enroll in classes and therapy in lieu of jail.

In response to criticism that the policy arbitrarily favored parents, Boudin pointed to the capriciousness of a system that sent his mother to prison for 22 years and sentenced his father to life, for the same crime:

“You point me to a place in the criminal justice system where the quality of justice is not arbitrary,” he said.

Kathy Boudin still has the well-worn paper atlas she kept in her prison cell, immersed in maps that became a lifeline to her teenage son when he discovered travel.

“It was a leap that I remember experiencing as him owning a certain part of life that he created, that he loved, and then he would share with all of us. But it was his,” she recalled.

He counted countries as intensely as he studied. (Now more than 100, on all seven continents.)

The night that Kathy Boudin was released from parole, after seven years during which she could not leave New York without permission, she called her son.

“He said, ‘Great! Now we can travel together,’” she recalled.

When Chesa Boudin decided to run for district attorney, the hardest part was telling his parents.

“I was wary, even unhappy about it,” Gilbert wrote in an interview from prison (he was since granted clemency and paroled in November). “I’m skeptical about what one can accomplish in the money-laden arena of electoral politics.”

“I was very concerned that as a prosecutor, you have to prosecute people. You have to put people in prison,” Kathy Boudin said. “What would that be like for him, and how would he handle that?”

He handled it by leaning into his family history to make points: People are more than their worst mistake. A man in his 70s with a perfect record during four decades in prison posed no danger to society and belonged at home. Coming face to face with victims can be the most potent rehabilitation.

“The thing that made the biggest difference for my mom was when she met one of the people whose lives she had turned upside down by participating in the crime,” Boudin told a forum.

Neither Kathy Boudin nor Bernardine Dohrn ever expected their son to enter politics. He had been a Rhodes scholar, worked as a translator for the administration of Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, written a coming-of-age memoir (ever competitive, he boasts it received the worst review ever in the New York Times), returned to Yale for law school.

Then he found a home at the San Francisco public defender’s office, which he talks about with uncharacteristic passion. “The energy, esprit de corps, commitment — the culture of the institution is one I found to be addictive,” he said.

But the victories of prosecutors such as Larry Krasner in Philadelphia and Rachael Rollins in Boston convinced him that a shift in public opinion had created opportunity for systemic change. In 2018, he was a finalist to run Los Angeles’ vast public defender’s office. That emboldened him when Gascón, the San Francisco district attorney at the time, decided not to run again, creating the first open contest for the office in 110 years.

A political novice, Boudin had two key assets. He was confident he would outwork the competition. And he was a networker since childhood. “There were 400 kids in our high school class,” said his brother Malik Dohrn, seven months older. “I stay in touch with eight. Chesa stays in touch with 400.”

Boudin eked out a victory, narrowly defeating Mayor London Breed’s favored candidate.

As he celebrated the night of his inauguration, Boudin had no idea how prophetic his words would soon seem:

“2020 is going to be an amazing year. There’s going to be a roller-coaster ride.”

::

For a while, the roller coaster brought heady highs: The twin crises of the pandemic and the murder of George Floyd made Boudin’s agenda both more urgent and politically feasible.

Keeping people out of jail — to provide space for social distance and reduce spread of the coronavirus — became an imperative amid a health emergency. The jail population shrank so quickly the city was able to close a structurally unsafe lockup.

The strength of the Black Lives Matter protests temporarily quieted Boudin’s most outspoken adversary, the police union, and fueled his agenda.

Prosecutors no longer asked for cash bail. They stopped seeking gang enhancements or “three strikes” charges, which dramatically increase the length of sentences. They refused to file charges for contraband seized during pretext stops, which overwhelmingly target Blacks and Latinos.

Boudin filed the first homicide charges in the history of San Francisco against a police officer for actions while on duty, then filed charges against four more.

The plunge came with equally dizzying speed. On New Year’s Eve 2020, a man on parole sped through an intersection and hit and killed two women, police said. Multiple agencies could have made different decisions that would have averted the tragedy, but the spotlight was on the district attorney’s failure to press charges that might have kept Troy McAlister behind bars.

McAlister’s name became shorthand for a prosecutor who let dangerous criminals roam the streets. The recall movement gathered momentum.

“As car break-ins and burglaries reached a crisis level in San Francisco, Boudin’s refusal to hold serial offenders accountable is putting more of us at risk,” the recall committee said.

Boudin tried for months to counter the accusations and underlying fears with data: Homicides had increased from a record low in 2019, but at a slower rate than neighboring jurisdictions. Police data showed crime overall had dropped in 2020. He was prosecuting drug cases at higher rates than his predecessor, while police were solving crimes at historically low rates.

He now sees the efforts to focus on the data as a mistake.

“In a world where people have good reason to be really skeptical of what they’re told by the government, if you’re scared, the last thing you want to hear is somebody tell you that your fear is irrational,” he said in March.

Boudin had won election by being the outsider who criticized a failed system; now he owned the system. To redefine public safety, to demonstrate that communities can be safe locking up fewer people, to build a consensus for programs that might break cycles of recidivism, would take years.

“So what do you do? You still have an ethical obligation to implement the best policies with the most consistency and the longest-term impact that you can politically afford to do. That’s the balancing act,” he said.

Boudin gravitates toward sports he characterizes as “mind over matter,” in which “there is literally always a little bit better you can do. And it’s always within your control. Or it feels that way.” He ran his first marathon after college on a course he measured around his parents’ camp in Northern California.

“It was him against him,” Dohrn said. “It was perfect in a way.”

The recall too is Boudin against himself.

He is still the outsider, a political interloper in a tightknit city. In a job that’s often a political springboard — one of his predecessors is now vice president of the United States — he is an anomaly; his ambition, said Judith Resnik, his law school mentor, “is to change what the whole world understands the role of a prosecutor to be.”

He likens his current situation to another favorite sport, chess, which he learned as a child from his grandfather, the prominent civil rights attorney Leonard Boudin.

“To the best of your ability, you’re anticipating what’s coming down the road and how you respond to it so that you’ve thought it through, and you’re not just reacting in the moment,” he said.

“But you can’t always see what’s coming.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.