Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

That the LAPD is confidently deploying this public relations tactic nearly three years after George Floyd’s death is a grim reflection of how little has changed.

Preliminary toxicology tests, performed on Anderson’s body by the police department itself, found traces of cannabinoids and cocaine metabolite in his system – results that in no way mitigate the extreme violence inflicted on Anderson by the police ahead of his January 3 death.

The drug tests were not released as part of an official autopsy; the Los Angeles County coroner’s office is still investigating Anderson’s death and has not yet ruled on its exact medical cause. Instead, the LAPD conducted its own drug tests and announced the results in an unambiguous effort to denigrate and blame its victim, the third man of color killed by the department in the few short weeks of 2023 alone.

There’s nothing surprising about this sort of police practice. The idea that drug possession or use by Black people creates grounds enough to warrant police violence, even deadly violence, has undergirded half a century of U.S. policing. Cops from the department that murdered George Floyd attempted to blame his death on the fentanyl found present in his system, too, but thankfully without success.

If Anderson’s official autopsy undermines police claims that drugs played a role in his death, it would be a relief, but not a victory. Instead, the very willingness of the LAPD to release its toxicology report speaks to a much broader problem: the certain confidence in the public’s willingness to demonize and blame Black victims. If such racist narratives around drugs weren’t readily available, the police department wouldn’t have bothered releasing the toxicology results at all.

That the LAPD is confidently deploying this public relations tactic nearly three years after Floyd’s death is a grim reflection of how little has changed.

This should come as no surprise, either: The uprisings that followed Floyd’s murder were met with harsh state repression in the streets, aided by disavowals and dismissals across the media and political mainstream. The Democratic lawmakers who knelt ludicrously in kente cloth to signal their anti-racist credentials are the same leaders who have rejected every serious attempt to reckon with the racist violence that defines U.S. policing.

Calls to defund the police were deemed electorally radioactive, demands to abolish the police derided as delusional, police budgets further swelled, and impunity has continued to reign.

Police killed 1,176 people in 2022 — more killings than in any of the last 10 years. And while racial justice organizers and abolitionists continue to fight, the mass rebellions of 2020 were aggressively drained of political potency by an array of counterinsurgent forces, from mass arrests, media demonization, and, crucially, the complete and cowardly abandonment by liberal politicians on the city, state, and federal levels.

I don’t doubt pollsters’ findings, that voters in 2020 were turned off by the term “defund,” but I’m not interested in relitigating debates around electoral slogans. What matters is that the reality of U.S. policing persists as a continuous, unrepentant, and reform-resistant threat to Black lives.

It should go without saying that the presence of drug traces in Anderson’s blood should in no way shift culpability for his death away from the police. Anderson died following a brutal interaction with police officers he had flagged down to ask for assistance after a traffic collision. Friends and relatives said Anderson was undergoing a mental health crisis — a tragically common circumstance of deaths in police custody.

As released body cam footage showed, Anderson was chased and pinned down in the middle of the street. Two LAPD officers held him down, one with an elbow on his neck, then a knee dug into his back while he was handcuffed, and another cop stood over him with a Taser gun, shooting him with its electric charge — directly in the back — again and again, for a total of over 90 seconds. Anderson was then taken to hospital, where he died around four hours later.

The presence of drugs in Anderson’s system doesn’t even mean that he was high at the time of his interaction with police. Cocaine metabolite can stay in a person’s system for days. More to the point, Anderson certainly didn’t die of a cocaine overdose: These almost exclusively happen while taking the drug, not after hours in a hospital following physical violence and extensive electrocution suffered at the hands of police.

Even as city residents are terrorized, police consume enormous amounts of these communities’ resources. The LAPD received $1.8 billion in city funding last year, 29 times higher than the city’s housing budget, amid a perilous homelessness crisis. Bloated police budgets have not diminished crime but simply expanded the potential for police interactions in which a civilian can be treated as criminal and face violence. Racist police logics maintain a stranglehold over U.S. political norms. Otherwise, it would be — as it should be — beyond doubt that the police are wholly responsible for Keenan Anderson’s death.

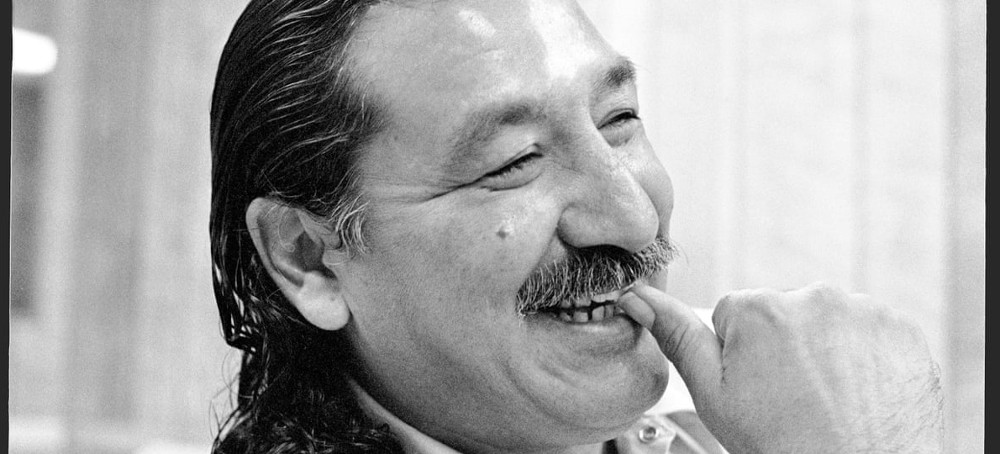

READ MORE  Leonard Peltier, was convicted of murdering two FBI agents and has been held in maximum security prisons for 46 of the past 47 years. (photo: Courtesy of Jeffry Scott)

Leonard Peltier, was convicted of murdering two FBI agents and has been held in maximum security prisons for 46 of the past 47 years. (photo: Courtesy of Jeffry Scott)

Exclusive: retired FBI agent Coleen Rowley calls for clemency for Indigenous activist who has been in prison for nearly 50 years

Coleen Rowley, a retired FBI special agent whose career included 14 years as legal counsel in the Minneapolis division where she worked with prosecutors and agents directly involved in the Peltier case, has written to Joe Biden making a case for Peltier’s release.

“Retribution seems to have emerged as the primary if not sole reason for continuing what looks from the outside to have become an emotion-driven ‘FBI Family’ vendetta,” said Rowley in the letter sent to the US president in December and shared exclusively with the Guardian.

Rowley added: “The focus of my two cents leading to my joining the call for clemency is based on Peltier’s inordinately long prison sentence and an ever more compelling need for simple mercy due to his advanced age and deteriorating health.

“Enough is enough. Leonard Peltier should now be allowed to go home.”

Peltier, an enrolled member of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa tribe and of Lakota and Dakota descent, was convicted of murdering two FBI agents during a shootout on the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota in June 1975. Peltier was a leader of the American Indian Movement (AIM), an Indigenous civil rights movement founded in Minneapolis that was infiltrated and repressed by the FBI.

Rowley refers to the historical context in which the shooting took place as “… the long-standing horribly wrongful oppressive treatment of Indians in the U.S. [which] played a key role in putting both the agents and Peltier in the wrong place at the wrong time”.

The 1977 murder trial – and subsequent parole hearings – were rife with irregularities and due process violations including evidence that the FBI had coerced witnesses, withheld and falsified evidence.

Peltier, now 78, has been held in maximum security prisons for 46 of the past 47 years. He has always denied shooting the agents. Last year, UN experts called for Peltier’s immediate release after concluding that his prolonged imprisonment amounted to arbitrary detention.

In an exclusive interview with the Guardian about her intervention, Rowley, who retired in 2004, said that for years new agents were “indoctrinated” with the FBI’s version of events.

“The facts are murky, and I’m not going to say either narrative is correct. I wasn’t there. But I do know that if you really care about justice, then the real issue now is mercy, truth and reconciliation. To keep this going for almost 50 years really shows the level of vindictiveness the organisation has for Leonard Peltier.

“The bottom line is there are all kinds of problems in the intelligence service which by and large never get corrected for the same reasons: group conformity, pride and an unwillingness to admit mistakes so systemic problems are covered up and never fixed,” said Rowley, a 9/11 whistleblower who testified to the Senate about FBI failures in the terrorist attacks.

Nick Estes, an assistant professor of American Indian studies at the University of Minnesota, said Rowley’s support of Peltier’s clemency was “historic”.

“She is trying to dispel a myth that is deeply embedded into the culture of the FBI … handed down through indoctrinating young recruits such as Rowley about Peltier’s unquestionable guilt and the FBI’s supposed blamelessness during the reign of terror on the Pine Ridge Indian reservation,” said Estes, a volunteer with the International Leonard Peltier Defense Committee.

Rowley wrote to Biden in response to a letter by the intelligence agency’s current director vehemently opposing Peltier’s release on behalf of the “entire FBI family” – which was recently published online by the Society of Former Special Agents of the FBI.

Christopher Wray described Peltier as a “remorseless killer who brutally murdered two of our own – special agents Jack R Coler and Ronald A Williams”. Commutation of Peltier’s sentence would be “shattering to the victims’ loved ones and an affront to the rule of law”, according to Wray’s letter to the justice department’s pardon attorney dated March 2022.

FBI has successfully opposed every clemency application with emotive op-eds, letters and marches on Washington.

But the time served on most murder sentences ranges between 11 and 18 years, while Mark Putnam, the first FBI agent convicted of homicide – for strangling his female informant – was released after serving just 10 years of a 16-year sentence. Peltier was sentenced to two consecutive life sentences, and a parole officer who recommended his release after acknowledging that there was not enough evidence to sustain the conviction, was demoted.

“The disparate nature of Peltier being held for nearly a half century behind bars is striking,” said Rowley, who in the 1990s helped pen an op-ed by the head of the Minneapolis division opposing Peltier’s release. “The facts are everything, not loyalty to the FBI family, not them versus us, not good guys versus bad guys.”

Peltier supporters hope that Rowley’s intervention will count.

“Rowley speaks with authority and is saying that nothing justifies him being in prison, just vindictiveness, so ignoring her means turning a blind eye to what’s happening,” said Kevin Sharp, Peltier’s attorney who submitted the most recent clemency application 18 months ago. “Rowley knows the case. She knows the FBI and supervised some of those directly involved. She knows Indian Country, so understands the context, which is really important.”

Peltier is currently being held in a maximum security prison in Coleman, Florida, where his health has significantly deteriorated since contracting Covid-19, according to Sharp, who visited in December. Multiple recommendations by the facility to lower Peltier’s classification, so that he can be transferred to a less restrictive prison closer to his family, have been rejected.

“This is a little old man with a walker. It’s not just the FBI that’s vindictive,” added Sharp, a former federal judge appointed by Obama who stepped down from the bench in protest of mandatory minimum sentences. He took on Peltier’s case in 2018 after successfully obtaining a pardon from Donald Trump for a young Black man he had been forced to imprison.

According to Sharp, Peltier’s clemency was still on the table until Trump’s last day in office but didn’t make it on to the final list of presidential pardons which was mostly former associates and white-collar criminals.

He added: “This is not about a 10-minute shootout. It’s about hundreds of years of what had gone before and the decades of what’s gone on afterwards. That’s why Leonard Peltier was convicted, and that’s why he’s still in jail.”

READ MORE George Santos allegedly took more than $3,000 from a disabled veteran who was raising money to pay for his dog's surgery. (photo: Win Mcnamee/Getty)

George Santos allegedly took more than $3,000 from a disabled veteran who was raising money to pay for his dog's surgery. (photo: Win Mcnamee/Getty)

Santos was tapped to help a veteran whose dog needed life-saving surgery, but he allegedly disappeared with the money, Patch reports

Per the report, disabled Navy veteran Richard Osthoff was raising money for his dog Sapphire back in 2016 when he was connected to Friends of Pets United — the organization that Santos led under the name of Anthony Devolder (a video recently emerged of the New York politician introducing himself as “Anthony Devolder” at a pro-Trump LGBTQ event).

After Santos and Osthoff connected, Santos — who is currently facing criminal investigations for lying about his qualifications during his run for congress — allegedly helped the veteran raise $3,000 on GoFundMe, deleted the fundraiser, and later disappeared with the money. While Santos claimed Friends of Pets United was a tax-exempt organization that he founded in 2013, the IRS could not find a record of a registered charity under that name, according to the New York Times.

“He stopped answering my texts and calls,” Osthoff told the outlet. (The fundraiser was unable to be located in web archives by Patch.)

Sharing screenshots of his Facebook posts on the matter, Osthoff explained that his dog died in 2017 without access to the life-saving treatment it needed, and that he was unable to afford euthanasia and cremation. “I had to panhandle. It was one of the most degrading things I ever had to do,” the veteran said.

Osthoff was later helped by Michael Boll, a local police sergeant who led NJ Veterans Network, to reach out to Santos after the GoFundMe was removed.

“I contacted [Santos] and told him ‘You’re messing with a veteran,’ and that he needed to give back the money or use it to get Osthoff another dog,” Boll said. “He was totally uncooperative on the phone.”

Osthoff claimed that Santos urged him to visit a vet clinic in New York where he had “credit,” but the veterinarian there said they “couldn’t operate the tumor.” In a final conversation with Santos, Osthoff said Santos told him that the charity had put the funds to use “for other dogs” after the GoFundMe wasn’t done his way.

“Remember it is our credibility that got GoFundme […] to contribute. We are audited like every 501c3 and we are with the highest standards of integrity,” Santos appears to write in a text message, as shown in a screenshot shared by Patch. “Sapphire is not a candidate for this surgery the funds are moved to the next animal in need and we will make sure we use of resources [sic] to keep her comfortable!”

Saphire’s death the following year contributed to Osthoff’s PTSD and worsened his mental health, he said. “Little girl never left my side in 10 years. I went through two bouts of seriously considering suicide, but thinking about leaving her without me saved my life,” he told the outlet. “I loved that dog so much, I inhaled her last breaths when I had her euthanized.”

The pet-related news with Santos comes after the Nassau County Republican Committee called for him to resign from his position after reports indicating the newly minted Long Island representative fabricated huge swaths of his personal backstory and resume.

In December, The New York Times exposed a series of lies Santos made regarding his resume, including fabrications regarding attending prestigious universities and having worked for major financial institutions. A follow up report by Forward found that Santos had claimed to be a “proud American Jew,” and the descendant of Holocaust survivors, despite ancestral records indicating that Santos had no Jewish ancestry.

Federal authorities and Nassau County prosecutors have initiated investigations exploring whether Santos’ fabrications and public misrepresentations constitute criminal activity. Despite this, Santos was sworn in as a member of Congress on Friday, and has spent his initial days in office dodging reporters and sitting solo in the House chamber.

READ MORE  Anti-abortion activists demonstrate outside the Supreme Court of the United States in Washington, U.S., June 13, 2022. (photo: Evelyn Hockstein/Reuters)

Anti-abortion activists demonstrate outside the Supreme Court of the United States in Washington, U.S., June 13, 2022. (photo: Evelyn Hockstein/Reuters)

This Sunday marks what would have been the 50th anniversary of Roe v. Wade, the 1973 ruling that guaranteed a constitutional right to abortion. But the landmark decision was overturned by the ultraconservative Supreme Court just over six months ago in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health. The court’s removal of the right to safe, legal abortions has led to total abortion bans in 12 states. Meanwhile, the push to ensure access to abortion has spurred new legal challenges and greater reliance on the abortion pill mifepristone, as medication abortions account for more than half of all U.S. abortions. We get an update from Amy Littlefield, abortion access correspondent at The Nation, whose most recent piece looks at how cities and states are acting to limit the damage from Dobbs. “There are an untold number of people staying pregnant against their will, despite the best efforts of activists,” she says.

Meanwhile, the push to ensure access to abortion has spurred new legal challenges and greater reliance on medical — on the medical pill, the abortion pill mifepristone, as medication abortions account for more than half of all U.S. abortions today. Starting today, New York City plans to offer free abortion pills at four sexual health clinics.

For more, we’re joined by Amy Littlefield, abortion access correspondent at The Nation. Her most recent piece is headlined “Cities and States Are Acting Fast to Blunt the Impact of Dobbs.” She’s just back from New Mexico, where activists are working to expand abortion access as people seek help there from neighboring states, like Texas, where abortion bans are in place.

Amy Littlefield, welcome back to Democracy Now! It’s great to have you with us. Why don’t you give us a lay of the land of abortion access around this country today?

AMY LITTLEFIELD: It’s so great to be back with you, Amy and Juan, on this somber and also, I would say, hopeful anniversary — or, what would have been the anniversary of Roe v. Wade.

So, I want to talk about the literal map of abortion access in this country right now. As you mentioned, 12 states ban abortion entirely in this moment, with some limited exceptions depending on how — each state law is different in terms of how dead or how sick the pregnant person has to be before there can be an intervention to save their life and terminate the pregnancy. Most of the states that have these bans do not make exceptions for rape or incest. And what’s really important, Amy, is, when you look at the map, there’s Idaho and South Dakota, and then there’s 10 states with these total bans that are all in a row in a deep red brick wall across the South. So, if you start in El Paso, Texas, and move to the east, to the eastern edge of Alabama, we’re talking about a solid block of 10 states. Moving up north to Missouri and to West Virginia in the east, we’re talking about states all in a row, multistates deep, more than 1,300 miles of states pushed together, where legal abortion is effectively gone.

And I want to tell you a number that I can’t stop thinking about since I found it, which is 58,000. Amy, that’s the number of abortions that happened in Texas in 2020. Fifty-eight thousand, OK? That’s like a decent-sized city — right? — that happens to be composed entirely of people of childbearing age, most of whom are women and also trans and gender-nonconforming people, who are pregnant and don’t want to be. And I ask you to imagine, in this landscape, this deep brick wall of abortion bans, where those 58,000 people are going to go. Right? What happens to them? And we know, you know, from speaking to activists in states like New Mexico, some of them are making it out. Some of them are making these arduous journeys in cars filled with sleeping bags and coolers. They’re driving across state lines. They’re boarding planes as part of airlifts coordinated by grassroots activists. But I think the emerging picture is that that is the exception and not the rule, and there are an untold number of people staying pregnant against their will, despite the best efforts of activists to help them get access to abortion pills even in states where abortion is banned or to get outside of the state to seek legal abortion elsewhere.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, Amy, there have been some states that have enacted laws that strengthen abortion rights or rejected ballot initiatives that would restrict the procedure. Could you talk about some of those states and what they are doing, in effect, to assist those in the abortion ban states?

AMY LITTLEFIELD: Absolutely, Juan, and you’re so right. I mean, there is this emerging picture of states, on the one hand, going as far as they can to ban abortion, and then, on the other hand, this really historic momentum building behind pro-abortion rights policies that once would have felt unheard of in this country. And that’s happening not just in blue states like California and New York, Washington, Oregon and Illinois; it’s also happening in cities and counties within these deep red states.

So, for example, Nashville, Tennessee, the City Council there has passed legislation deprioritizing enforcement of abortion-related crimes, because abortion is illegal in Tennessee. So, the Nashville city councilors said, “Well, what can we do?” You know, they have also allocated half a million dollars to Planned Parenthood to fund reproductive healthcare.

So we’re seeing cities and counties trying to step up. Atlanta is another one that’s directed public funding, as well as Seattle — right? — a city that you might have expected that from. New Orleans, cities in — Denton, Texas, these are places that are passing proactive measures to blunt the impact of criminal abortion laws and also to try to shore up reproductive healthcare access wherever they can.

In the first three months after the Dobbs decision came down reversing Roe v. Wade, we saw 17 states and at least 24 municipalities moving to expand or protect abortion access. That’s according to the National Institute for Reproductive Health. So, that’s really historic, and it speaks to a huge surge in momentum and, I think, a lot of Democratic politicians at the local and county and state level understanding that there’s tremendous power in local government. Now, the anti-abortion movement was very savvy about realizing that before, but I think we’re seeing a long-overdue recognition of the power of local government among progressives right now.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And could you talk, as well, about the actions of the federal government, of the Biden administration, and the announcement earlier this month of the Food and Drug Administration?

AMY LITTLEFIELD: Right. So, what happened earlier this month is that the Food and Drug Administration announced an easing of restrictions on mifepristone, the abortion pill, which is one of the medications taken to induce a medication abortion. And what it will allow is for the abortion pill to be sold in retail pharmacies, like CVS and Walgreens, if someone has a prescription. This is a game changer for people who live in states where abortion is legal, who might be able to go to a CVS or Walgreens. This is if these pharmacies go through the certification process the FDA has set up. Then you can go to a CVS or a Walgreens in a state like Massachusetts, where I am, or New York and get your prescription for the abortion pill filled there, which is a huge shift. I mean, before, because of the pandemic, the Biden administration had made the abortion pill available through the mail, from mail-order pharmacies. Before that, you had to go in person to a clinic in order to get it. So, this is a game changer, but one that affects people in states where abortion is already legal. The same thing with Mayor Eric Adams’ decision and the public health clinics that are going to be offering the abortion pill in New York City for free — I mean, that’s a huge, hugely significant decision.

I think each of these decisions moves the Overton window — right? — takes a step towards destigmatizing abortion and could lead to people in states where abortion is banned, you know, in Tennessee and Arkansas, demanding not just a reimplementation of the protections in Roe v. Wade, but free abortion pills in the public health clinic. If it’s happening in New York City, I think that shifts the Overton window for everyone else.

And I want to say — you know, not to give Eric Adams too much credit here. I want to just say these movements, these victories belong to the movements that are advocating for them, and not to the politicians, because we know Democrats have spent a long time treading water when it comes to expanding abortion access, and I think they’re moving now because of this crisis and because of the enormous amount of momentum behind the deeply popular right to an abortion —

AMY GOODMAN: And, Amy —

AMY LITTLEFIELD: — and restoring it and expanding it.

AMY GOODMAN: It may have explained why the House division between Democrats and Republicans is so close, that it wasn’t a red wave, as many had predicted, because of people’s concern about reproductive rights access. But what about, for example, Kathy Hochul, the governor of New York, who ran on a very pro-choice stand against Lee Zeldin, fiercely anti-choice, and yet she appoints to the — she nominates to the highest court Hector LaSalle. Many progressives are condemning this move because he is anti-choice, not to mention anti-labor.

AMY LITTLEFIELD: Absolutely, Amy. And I have to say, the sound and the fury that are merging the enormous amount of resistance around LaSalle’s nomination shows what happens when two of the most enormously powerful and surging underpinnings of the Democratic Party’s power get together — right? — labor unions, on the one hand, opposing LaSalle’s stance against unions in rulings against unions, and then abortion rights, right? I mean, I wish we saw more collaboration — and I think we will — between those two extremely powerful movements.

But the reason why LaSalle is a deep concern for supporters of abortion rights, and the other day more than a hundred experts and advocates and organizations that support abortion rights signed on to a letter opposing his nomination, is because of a ruling in favor of crisis pregnancy centers. These are anti-abortion centers that often pose as abortion clinics, that try to look like medical clinics. And when Attorney General Eric Schneiderman tried to investigate them several years ago, he was stymied by a ruling that LaSalle had signed on to. And so, that’s of tremendous concern, especially because, you know, these policies, like the one in New York City to issue free abortion pills in public health centers, the efforts by the New York state Legislature to shore up abortion access, they don’t mean anything if the courts are against those policies. And if the highest court in the land is going to come down and reverse those policies or stymie those policies because of an anti-abortion stance, then, you know, these policies, even in a state like New York that’s considered safe, are dead in the water. And so this is hugely consequential.

And I think it’s clear that Kathy Hochul didn’t read the writing on the wall, right? I mean, Democrats owe the fact that they averted a total disaster in the midterms to the reversal of Roe v. Wade and the enormous amount of work and grassroots organizing that went into pushing back against that overturn and trying to restore abortion rights. I mean, if you don’t believe me, consider the fact that there were six states where abortion was directly on the ballot in the midterms, OK, starting with Kansas in August, of course, which we talked about on the show. And even in red states like Kansas, Kentucky, Montana, the abortion rights position won in every single one of those ballot measures. And so, what that says is that the Democratic base is fired up on this issue. It sees a connection between abortion and other economic issues. And some Democrats are recognizing that. And it would seem some Democrats, like Kathy Hochul, are not understanding precisely what their constituents want.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Amy, we just have a few seconds left, but I wanted to ask you — you mentioned you had been to New Mexico recently and the New Mexico Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice. Could you talk about what you saw on the ground there?

AMY LITTLEFIELD: Yeah. So, I visited the headquarters of the New Mexico Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice, which is an abortion fund that provides practical support. They help with the logistics of people traveling to New Mexico. And again, remember, New Mexico is right to the west bordering Texas, that state where there were 58,000 abortions in 2020, OK? And this is a state that had about a tenth of that in terms of their 2020 numbers for abortion.

So, this is a grassroots organization. Every week they reserve 10 spots on an airplane to bring patients from Texas and airlift them to New Mexico for an abortion. And they have set up — their offices have begun what looks like sort of a field hospital in this new borderland of abortion access. They’ve got cots for people to rest on. They’ve got heating pads that were stitched by volunteers; cookies baked by volunteers; freezers full of frozen dinners; maxi pads; toys for kids. I mean, it’s this real — it’s this way station for people who are making a long journey from out of state, mostly from Texas, to come to New Mexico, which has become this haven destination for abortion. You’re seeing clinics following the flow of patients moving to New Mexico from states where abortion is banned.

But the most chilling thing that stuck with me from this visit, Juan, is that they told me that they don’t always — they’re not always able to fill those 10 spots on the airplanes that they fly each week. Sometimes they have seven people coming. Sometimes they have fewer. And what I think that speaks to is an enormous amount of confusion and an enormous amount of sort of lack of information for people who need an abortion and might not know where to go. And we don’t know how many of those patients are self-managing an abortion with the help of grassroots organizations or, you know, some underground networks. We don’t know how many of those people are just staying pregnant against their will. And that really is the human rights crisis that is unfolding in real time right in front of us on this Roe v. Wade anniversary.

AMY GOODMAN: Amy Littlefield, we want to thank you so much for being with us, abortion access correspondent at The Nation. We’ll link to your latest piece, “Cities and States Are Acting Fast to Blunt the Impact of Dobbs.”

Next up, as Senator Bernie Sanders gives a national address on the state of America’s working class, we’ll look at what he addressed last night: the growing problem of medical debt and the movement to stop hospitals from suing patients, having their wages garnished, putting liens on the homes of people facing medical bills they cannot afford. Stay with us.

READ MORE  Kevin McCarthy speaks during a news conference at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. (photo: Stefani Reynolds/Bloomberg)

Kevin McCarthy speaks during a news conference at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. (photo: Stefani Reynolds/Bloomberg)

The Right plans to seize on the debt ceiling to ram through unpopular ideas. The strategy could force Democrats to choose between government paralysis or draconian cuts to the federal budget — possibly even Social Security and Medicare.

By any rational measure, this shouldn’t be a big deal. There’s little technical reason for the debt ceiling to exist at all — a view shared, among others, by Yellen herself. Despite support from even moderate figures like Yellen, Democrats refused to eliminate the debt ceiling when they controlled both houses of Congress. Instead, they handed Republicans a loaded gun.

With the debt ceiling, as with counting votes or certifying an election, the Right hopes to seize on this otherwise drab government function as a point of leverage to thrust unpopular ideas onto the country. A faction of the incoming House Republican majority all but forced Kevin McCarthy to commit to shutting down the government before they would support his run for Speaker of the House. To be fair, McCarthy hardly needed to be strong-armed: he already said last fall that he planned to play chicken with Democrats over a government shut down in order to force cuts to Social Security and other government programs.

In fact, as the Washington Post reported Friday, rather than try to figure out a way to avoid a needless debt crisis, House Republicans’ primary concern is finding a way to make the Treasury keep paying investors who hold government bonds when the government shuts down. Instead of avoiding needless harm to the economy, they just want to shield their real constituents from the worst of the fallout.

For such a plan to work, it would have to both pass the Senate and receive Joe Biden’s signature — both of which, for the moment, appear to be nonstarters. But Biden and the Democrat-led Senate also need the House to agree to raise the debt limit and pass a budget if they want the government to keep running.

What looks like a stalemate on paper unfortunately favors the Right. Republicans are only too happy for most of the government to close down, meaning they have far less to lose in sticking to a hard line in negotiations. That leaves Biden and Democrats with two unacceptable outcomes: a nonfunctioning government, or draconian cuts to the federal budget, including potentially to Social Security and Medicare.

The most likely course of events is after several weeks of needless pain, representatives of economic sectors that depend to a greater extent on steady credit and government regulation will put enough pressure on McCarthy to go back on his promises to the far-right members of his caucus. He’ll eventually force through a stopgap measure that gets Democrats to agree to inflict significant pain on the American people for no good reason (if not as much as Republicans want), and then the far right of the party will depose him as speaker. Some other equally masochistic empty suit will take his place, we’ll all forget about it for six months, nothing will change, and then it will be time for the country to take another stupid ride on the same merry-go-round, our pockets a little emptier for it.

Doesn’t it always seem to turn out that way somehow?

READ MORE  A man walks past a burning barricade during a protest against Haitian Prime Minister Ariel Henry, calling for his resignation, in Port-au-Prince. (photo: Richard Pierrin/AFP)

A man walks past a burning barricade during a protest against Haitian Prime Minister Ariel Henry, calling for his resignation, in Port-au-Prince. (photo: Richard Pierrin/AFP)

The constitutional mandate of Haiti's de facto ruler, Prime Minister Ariel Henry — which some viewed as questionable from the start, as he was never technically sworn in — ended more than a year ago.

The country has had no president since its last one, Jovenel Moïse, was assassinated in 2021. Its Senate is supposed to have 30 members, and its lower legislative chamber should have 119; all of those seats are unfilled. Haiti's elected mayors were all reappointed or replaced in 2020.

And last week, its 10 remaining senators departed office after their terms ended, leaving behind a nation's worth of elected offices that now sit empty after years of canceled elections.

"The situation is catastrophic," said Robert Fatton, a Haitian-born political scientist at the University of Virginia. "It would not be an exaggeration to say that the current crisis is one of the most severe crises that Haiti has ever confronted."

The country of 12 million people last held national elections in 2016. In the years since, the turmoil — political and otherwise — has been relentless.

Gang violence has displaced more than 150,000 people from their homes and forced aid groups such as Doctors Without Borders to close facilities and relocate staff. A new outbreak of cholera is suspected to have infected nearly 25,000 Haitians since October. In 2021, an earthquake killed 2,000 people and wrought new devastation to a part of the country that had been hit just five years before by a Category 5 hurricane.

Rampant inflation has sent the cost of food and gas spiraling; food insecurity is so widespread that about 40% of the population do not have enough to eat. And the disasters have combined to keep thousands of the country's schools closed, meaning millions of Haitian children have lacked steady education and meals since the beginning of the pandemic.

"I grew up under dictatorship, so I'm not idealizing the Haiti I grew up under. But this is the first time I think we have seen this level of lawlessness, this level of gang violence where people's lives do not matter," said Cécile Accilien, a professor of Haitian studies at Kennesaw State University, in an interview with NPR.

Unending political turmoil

Even before the shocking assassination of President Moïse in July 2021, in which he was killed inside his private residence in Port-au-Prince, Moïse had been ruling by decree. He declined to call elections in 2018, then again in 2019, causing the terms of most of the country's legislators and mayors to expire in January 2020.

That had already made him increasingly unpopular. Then, shortly before the still-unsolved assassination, Moïse appointed Dr. Ariel Henry, a neurosurgeon and former government minister, to serve as prime minister.

But lacking a quorum in the legislature to consider his appointment, Henry was never formally sworn in. After Moïse's assassination, Henry emerged from a power struggle as de facto ruler. Even that shaky constitutional backing ended long ago; Haiti's constitution requires elections to be held within 120 days of a presidential vacancy, a period that ended in November 2021.

Now, Henry stands alone at the head of a fractured, weakened government that appears powerless to address the country's many challenges: gang violence, cholera, inflation.

"It's a collapse," said Patrice Dumont, one of the 10 senators who departed office this month.

Speaking to NPR last fall, Dumont said rampant corruption had kept Haiti from making progress. "The situation that we are facing now, it's made because of the bad choices made by Haitian actors, Haitian political leaders," Dumont said.

A small group of elites have long controlled Haiti's ports, customs and government welfare agencies, he said. "And they live almost in paradise," even as millions of Haitians live in poverty, he said. Other key ports and roads are held by gangs, who control an estimated 60% of Port-au-Prince.

Dumont compared Haiti, with its widespread social injustice and wealth inequality, to a pressure cooker always at threat of explosion.

After Moïse's assassination, a group of civil society organizations and political parties convened to chart a different path forward for Haiti. Together, in late 2021, they proposed what's been called the Montana Accord: a two-year interim government, led by a president and prime minister, to provide stability and oversight until new elections could finally be held.

Negotiations between the group and Henry have not yet borne fruit. Meanwhile, the country's myriad humanitarian crises have worsened since the political chaos began.

Last October, amid a fuel crisis set off by the elimination of fuel subsidies and gang control of a key terminal, Henry requested foreign military intervention to help stabilize the situation.

The U.S. and U.N. said they would consider Henry's request. But among Haitians, that call was widely unpopular; much of the population views foreign groups with distrust after years of ineffective — or downright harmful — interventions by international organizations and governments. Haiti's national police regained control of the fuel terminal in November.

Henry has called for elections in 2023, but many are skeptical

Now, all eyes are on Henry, who recently agreed to hold elections this year with the aim of swearing in a new government in early 2024.

On New Year's Day, Henry called for a new round of elections, writing on Twitter that they must be done "without prejudice" and "in transparency."

But Henry has not said when such a vote would happen — instead, he has promised to reestablish a long-disbanded electoral council to plan and propose "a reasonable timetable" for elections.

Henry's pledges have drawn wide skepticism. A similar commitment in 2021 failed to materialize.

"It is highly unlikely that Henry can deliver on any of these new promises," said Fatton of the University of Virginia.

Given the country's terrible security situation and the lack of popular support for Henry's government, the idea of elections in the immediate future is "frankly preposterous," Fatton said. "Having elections after six or seven months would recreate the current mess and the prevailing zero-sum-game politics."

The United Nations said last month it would appeal for $719 million for Haiti in 2023, about double the amount in 2022. Ulrika Richardson, the U.N. humanitarian coordinator in Haiti, said last month that efforts to combat the worsening crises would be ineffective unless the root causes of Haiti's problems are addressed.

"It's going to be very difficult if we don't address this now," she said. "We have corruption. We have impunity. We have governance. And all of that needs to really be at the center of our thinking as we go forward."

READ MORE  A boat navigates at night next to large icebergs near the town of Kulusuk, in eastern Greenland, Aug. 15, 2019. (photo: Felipe Dana/AP)

A boat navigates at night next to large icebergs near the town of Kulusuk, in eastern Greenland, Aug. 15, 2019. (photo: Felipe Dana/AP)

>New research in the northern part of Greenland finds temperatures are already 2.7 degrees warmer than they were in the 20th century

That’s the finding from research that extracted multiple 100-foot or longer cores of ice from atop the world’s second-largest ice sheet. The samples allowed the researchers to construct a new temperature record based on the oxygen bubbles stored inside them, which reflect the temperatures at the time when the ice was originally laid down.

“We find the 2001-2011 decade the warmest of the whole period of 1,000 years,” said Maria Hörhold, the study’s lead author and a scientist at the Alfred Wegener Institute in Bremerhaven, Germany.

And since warming has only continued since that time, the finding is probably an underestimate of how much the climate in the high-altitude areas of northern and central Greenland has changed. That is bad news for the planet’s coastlines, because it suggests a long-term process of melting is being set in motion that could ultimately deliver some significant, if hard to quantify, fraction of Greenland’s total mass into the oceans. Overall, Greenland contains enough ice to raise sea levels by more than 20 feet.

The study stitched together temperature records revealed by ice cores drilled in 2011 and 2012 with records contained in older and longer cores that reflect temperatures over the ice sheet a millennium ago. The youngest ice contained in these older cores was from 1995, meaning they could not say much about temperatures in the present day.

The work also found that compared with the 20th century as a whole, this part of Greenland, the enormous north-central region, is now 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer, and that the rate of melting and water loss from the ice sheet — which raises sea levels — has increased in tandem with these changes.

The research was published in the journal Nature on Wednesday by Hörhold and a group of researchers at the Alfred Wegener Institute, the Neils Bohr Institute in Denmark, and the University of Bremen in Germany.

The new research “pushes back the instrument record 1,000 years using data from within Greenland that shows unprecedented warming in the recent period,” said Isabella Velicogna, a glaciologist at the University of California at Irvine who was not involved in the research.

“This is not changing what we already knew about the warming signal in Greenland, the increase in melt and accelerated flow of ice into the ocean, and that this will be challenging to slow down,” Velicogna said. “Still, it adds momentum to the seriousness of the situation. This is bad, bad news for Greenland and for all of us.”

Scientists have posited that if the air over Greenland becomes warm enough, a feedback loop would ensue: The ice sheet’s melting would cause it to slump to a lower altitude, which would naturally expose it to warmer air, which would cause more melting and slumping, and so forth.

That this north-central part of Greenland is now 1.5 degrees Celsius warmer than it was in the 1900s does not necessarily mean the ice sheet has reached this feared “tipping point,” however.

Recent research has suggested that Greenland’s dangerous threshold lies at about 1.5 degrees Celsius or higher of planetary warming — but that is a different figure than the ice sheet’s regional warming. When the globe reaches 1.5C of warming on average, which could happen as soon as the 2030s, Greenland’s warming will likely be even higher than that — and higher than it is now.

Researchers consulted by The Washington Post also highlighted that the northern region of Greenland, where these temperatures have been recorded, is known for other reasons to have the potential to trigger large sea-level rise.

“We should be concerned about north Greenland warming because that region has a dozen sleeping giants in the form of wide tidewater glaciers and an ice stream … that awakened will ramp up Greenland sea level contribution,” said Jason Box, a scientist with the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland.

Box published research last year suggesting that in the present climate, Greenland is already destined to lose an amount of ice equivalent to nearly a foot of sea-level rise. This committed sea-level rise will only get worse as temperatures continue to warm.

The concern is focused on the Northeast Greenland Ice Stream, which channels a major portion — 12 percent — of the ice sheet toward the sea. It’s essentially a massive slow-moving river that terminates in several very large glaciers that spill into the Greenland Sea. It is already getting thinner, and the glaciers at its endpoint have lost mass — one of them, the Zachariae Isstrom, has also lost its frozen shelf that once extended over the ocean.

Recent research has also demonstrated that in past warm periods within the relatively recent history of the Earth (i.e., the last 50,000 years or so), this part of Greenland has often held less ice than it does today. In other words, the ice stream might extend farther outward from the center of Greenland than can be sustained at current temperatures, and be strongly prone to moving backward and giving up a lot of ice.

“Paleoclimate and modeling studies suggest that northeast Greenland is especially vulnerable to climate warming,” said Beata Csatho, an ice sheet expert at the University at Buffalo.

In the same year when the researchers were drilling the ice cores on which the current work is based — 2012 — something striking happened in Greenland. That summer, in July, vast portions of the ice sheet saw surface-melt conditions, including in the cold and very high-elevation locations where the research took place.

“It was the first year it has been observed that you have melting in these elevations,” said Hörhold. “And now it continues.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.