Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Videos and messages from inside Putin’s army show troops deserting, fleeing and struggling to find their teams

Recently mobilised soldiers are refusing orders to face “certain death” by joining “human wave” attacks that they say are destroying entire units at a time.

Some are appealing directly to Putin in desperate videos, while others are standing up to Kremlin officials sent to quell the rebellion.

Reports are emerging of fighters being locked underground for declining to become targets in the “shooting range” that has become the front line.

Meanwhile the Russian army has been forced to create a new unit to round up all the “lost” soldiers deserting, fleeing or struggling to find their teams.

Soldiers from at least 16 different regions recorded video messages since early February to blame commanders for trying to use them in “human wave” attacks, according to a tally by Russian media outlet Verstka.

The Russian tactic of sending “human waves” of poorly trained and poorly armed fighters into the line of fire to overwhelm the opposition has become increasingly common, according to military observers.

READ MORE ![]() Silicon Valley Bank in Santa Clara, California. (photo: Nathan Frandino/Reuters)

Silicon Valley Bank in Santa Clara, California. (photo: Nathan Frandino/Reuters)

US treasury secretary says Biden administration is working closely with regulators to help depositors as fears of banking crisis rise

Yellen said conditions did not match the 2008 financial crisis, when the collapse of large institutions threatened to bring down the global financial system.

Yellen sought to calm fears that the $23tn US banking system could be affected by the collapse of relatively small regional bank.

“The American banking system is really safe and well-capitalized, it’s resilient,” she told CBS’s Face the Nation. “Americans can have confidence in the safety and soundness of our banking system.

“Let me be clear that during the financial crisis, there were investors and owners of systemic large banks that were bailed out … and the reforms that have been put in place means we are not going to do that again.

“But we are concerned about depositors and are focused on trying to meet their needs.”

Citing anonymous sources, Reuters reported on Sunday that the US government was expected to make a “material” announcement of plans to shore up SVB deposits and prevent wider fallout.

“We want to make sure that the troubles that exist at one bank don’t create contagion to others that are sound,” Yellen said.

The sudden failure of SVB, a California bank with assets valued at $212bn which primarily lent to tech start-ups, rattled investors and triggered calls for regulators to step in.

On Friday, SVB was placed under the control of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which guarantees deposits to $250,000. But many companies and individuals stand to lose more than half of deposits in excess of that, according to some estimates.

Mark Warner, a Virginia Democrat on the US Senate banking committee, said SVB had been “caught in a bind” by higher interest rates. A run on the bank late last week, with $42bn withdrawn on Thursday alone, was accelerated by “some actors”, he told ABC’s This Week.

Warner said he had been in talks with regulators, the White House and the Federal Reserve. The best outcome, he said, would be to find a buyer for SVB assets before markets opened in Asia late on Sunday.

“That would be best,” he said, adding: “Shareholders in the bank are going to lose their money. Let’s be clear about that. But the depositors can be taken care of, and the best outcome will be an acquisition of SVB.”

Warner indicated that unlike in 2008, there was a broad consensus in Washington that “shareholders of [SVB] ought to lose their money. Depositors have been a different circumstance, but there are questions around moral hazard”.

The Fox Business commentator Charles Gasparino tweeted that SVB depositors had been told they would “receive 30% to 50% of their money [on] Monday and most of the rest over time if there is no solution”.

The White House director of the Office of Management and Budget, Shalanda Young, told CNN’s State of the Union the situation was being taken “seriously” and attempted to soothe fears that other regional banks might be affected.

“It has a better foundation than before the financial crisis largely due to the reforms put in place after the financial crisis,” Young said, adding that reforms after 2008 gave “regulators more tools, and our system is more resilient in the foundation stronger”.

Yellen’s rejection of a bailout may increase fears of a domino effect on other banks if regulators do not find a buyer for SVB assets. But current and former financial officials in Washington indicated that the collapse of SVB does not warrant federal intervention.

A former FDIC chair, Sheila Bair, told NBC’s Meet the Press SVB was a $200bn bank in a $23tn banking industry.

“I think it’s going to be hard to say that this is systemic in any way,” she said.

Earlier, the Fed and FDIC were said to be considering the creation of a fund to backstop deposits at banks that run into trouble, Bloomberg reported.

The White House said on Saturday Joe Biden had spoken to the governor of California, Gavin Newsom.

“Everyone is working with FDIC to stabilize the situation as quickly as possible,” Newsom said.

The risk and financial advisory firm Kroll said it was “unlikely that an SVB-style bankruptcy will extend to the large banks”. But it warned that small community banks could face problems and the risk was “much higher if uninsured depositors of SVB aren’t made whole”.

Regional banks that have seen values plunge since the SVB crisis began include Signature Bank, First Republic Bank, Western Alliance and PacWest, which dropped 38%.

The failure of SVB “could be the first cockroach in the cellar”, the investment manager Fredric Russell told the Wall Street Journal. The failed bank was reportedly without a risk management officer for months before it collapsed.

“Banks get thrown into the dark pool of complacency, and then they lower their quality standards,” Russell said.

Bill Ackman, a billionaire hedge fund manager, also said failure to protect SVB depositors could spark withdrawals of uninsured deposits from other banks.

“These withdrawals will drain liquidity from community, regional and other banks and begin the destruction of these important institutions,” Ackman warned in a tweet thread.

“The government has about 48 hours to fix a-soon-to-be-irreversible mistake,” he wrote. “The unintended consequences of the government’s failure to guarantee SVB deposits are vast and profound and need to be considered and addressed before Monday. Otherwise, watch out below.”

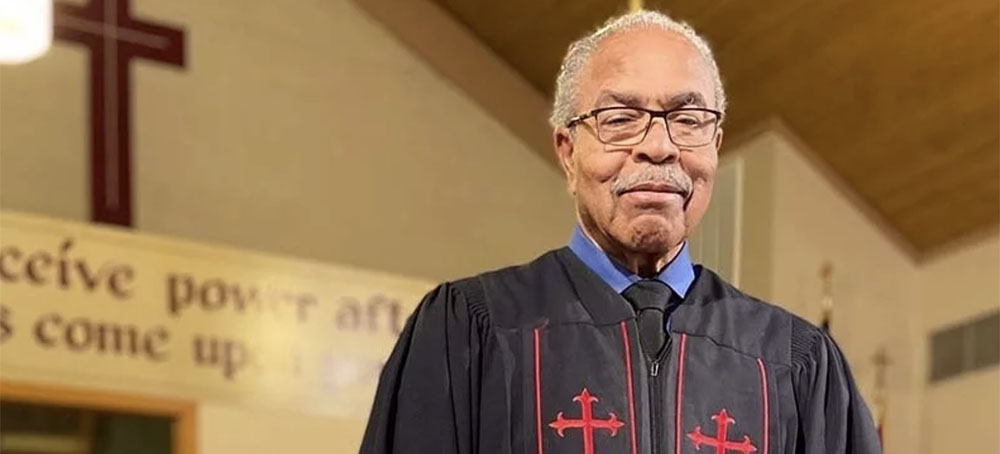

READ MORE The Rev. Wheeler Parker Jr. is the last living witness of the kidnapping of Emmet Till. Nearly 70 years later, he will still break down in tears when he describes what happened. (photo: Dr. Marvel Parker/NPR)

The Rev. Wheeler Parker Jr. is the last living witness of the kidnapping of Emmet Till. Nearly 70 years later, he will still break down in tears when he describes what happened. (photo: Dr. Marvel Parker/NPR)

There are times even now, when he will break down in tears when he describes what happened that night in Mississippi in 1955. Still, the story must be told.

"It changed my life," said the 83-year-old Parker. "I promised God if he just saved my life, I was going to do right."

Parker was just 16 years old when his cousin and best friend, 14-year-old Emmett Till, was lynched. Till's murder would spur international outrage and propel the fight for justice and equality. Parker is the last living witness of the kidnapping.

"We're here now because he still speaks from the grave. His story resonates and brought about a lot of changes," said Parker, who is now the pastor of the Illinois church founded by Till's grandmother.

Parker spoke to NPR as a part of a Weekend Edition series shining a spotlight on the Civil Rights generation. In his new book, A Few Days Full of Trouble, Parker tells the story of Till's death, but also of his life.

The best of friends

Before Till became a symbol for the civil rights movement, he was just a child who was silly, brave and adored by his family. Their nickname for him was Bobo.

"He was a fun-loving prankster, loved to tell jokes, stuttered all of the time. We do not really emphasize his stutter enough," Parker said.

The stutter was the result of a bout with polio, but it didn't slow Till down. According to Parker, Till was always the center of attention. The two of them were very close, living next door to each other in Chicago.

"Emmett didn't have any siblings, so when his mother took him on trips or fishing or something, she took me along. We were bonded like that."

Parker said that when Till learned he'd be traveling to Mississippi in the summer of 1955 to visit his grandfather, he pleaded with the family to let him tag along.

"They finally decided to let him go. And that's how we went - ended up going together," Parker said.

Danger in the Jim Crow south

That trip would end in tragedy. Till was not familiar with the strict racist dynamics that governed every interaction between Black people and white people in the south. The slightest infraction of the mores of the Jim Crow south could lead to violence and death.

During the trip, Parker and Till and other relatives went to a store. On the way out, Till whistled at a white woman.

"He loved to have pranks, so he whistled. He gave her the wolf whistle," Parker said. "When he did that, we could have died. Nobody said, 'Let's go.' We just made a beeline for the car."

"He was joking," Parker said. "He wanted to make us laugh. When he saw that we didn't laugh and we were scared, he's frightened now. And we jumped in the car, and we're going on this gravel road. And there's a car coming behind us. Dust is flying everywhere. And someone said, 'They're after us, they're after us.' And of course, we jumped out of the car and into the cotton field, and the car went on by."

After that encounter on the road, Till begged his relatives to not tell Parker's grandfather what happened.

A few days later, in the middle of the night, white men came to the house where Till and Parker were staying.

"I heard them talking at 2:30 in the morning," Parker recounted. "They said: 'You got two boys here from Chicago.' And, of course, when I hear this, I'm thinking — I said, man, we're getting ready to die. I said, these people finna kill us."

He remembers trembling with fear.

"I'm shaking like a leaf on the tree in the dark of a thousand midnights. It's so dark, you can't see your hand before your face. So, when they came in with the gun in one hand and a flashlight in the other, I closed my eyes to be shot. Horrible feeling. Horrible, horrible feeling."

When the men found Till, he was in bed, Parker said.

"Then they aroused him. And I think they told him to put his shoes on, and he wanted to put his socks on. It was just pure hell over there. Emmett had no idea who he was dealing with. He had no idea what was about to happen to him. He had no way of knowing because he didn't know that way of life. And he left, and that's the last time we saw him alive."

Keeping Till's memory alive

After Till was murdered, his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, rallied to make sure the world never forget what happened to her son.

"I tell people, Emmett, Bobo, was not the first person that suffered at the hands of Southerners," Parker said. "But this story, as God would have it, went ballistic. It went everywhere. And they — the whites — were not used to stories getting out like this."

Parker never talked to Mamie about what happened to her son.

"She never asked me what happened," he said. "I always had survivor's guilt. You know, how did she feel about me being here? Her son didn't come back. So we never discussed it at all. She just recognized that I was the one with her son. I came back, and her son didn't."

But, years later she would ask Parker to carry on his legacy.

"We have an Emmett Till memorial center. And she came and she saw what we were doing. She said: 'I want you to carry on the work.' And I remember saying, yes, but inside, I said, what can I do, what can I do? Not knowing that I'll be catapulted to where I am now. God put things in place, where - when it's God's will, it's his bill. He going to make sure he put the fire in you to do what you're supposed to do."

READ MORE  Mifepristone, the first pill typically given in a medical abortion. (photo: Evelyn Hockstein/Reuters)

Mifepristone, the first pill typically given in a medical abortion. (photo: Evelyn Hockstein/Reuters)

The lawsuit by Marcus A. Silva of Galveston County, Texas, seeks more than $1 million from each of the three defendants and an injunction prohibiting them from "distributing abortion pills." Silva's ex-wife is not a defendant in the suit.

It's believed to be the first such case since the Dobbs v Jackson Women's Health Organization decision last June overturned decades of abortion-rights precedent, allowing laws criminalizing abortion to take effect around the country.

The lawsuit alleges that Silva's then-wife discovered she was pregnant in July 2022 and tried to conceal both the pregnancy and the self-managed abortion from him. According to the lawsuit filed in state court, the couple divorced in February of this year.

Silva's then-wife worked with two of the women accused in the lawsuit, which includes screenshots of text messages that appear to show the friends discussing various ways of obtaining abortion pills and the logistics involved in self-managing an abortion at home. The third woman is accused of supplying the abortion pills.

In one exchange, one of the friends tells the pregnant woman, "You can do it at home. We can take the day off and do it at my place if you want."

In another message, the woman expresses gratitude to her friends, telling one of them, "your help means the world to me" and adding that she felt "so lucky to have y'all."

Silva's lead attorney is Jonathan Mitchell, who is known for designing the legal strategy behind Senate Bill 8, the unique Texas abortion ban that took effect in 2021 after the U.S. Supreme Court declined to block it. That law, implemented months before the Dobbs decision, got around federal precedent by employing what opponents describe as a "bounty hunter" system. It allows private citizens to sue anyone believed to be involved in helping a patient obtain an illegal abortion in Texas for tens of thousands of dollars.

But this case takes a different and arguably more aggressive strategy by instead referring to the state's wrongful death, murder and anti-abortion statutes. The suit describes assisting an abortion in Texas as an "act of murder" and notes the abortion took place after the Dobbs ruling, arguing that it was not protected by any federal precedent.

It repeatedly describes the abortion as the "murder" of Silva's "unborn child" with "illegally obtained pills." The suit also claims the three defendants conspired with the pregnant woman to secretly terminate her pregnancy.

The suit specifically notes that Silva's ex-wife is "exempt from civil and criminal liability and Marcus is not pursuing any claims against her." In the aftermath of Dobbs, the question of whether people who have abortions should be targeted for prosecution has been an ongoing subject of speculation and sometimes debate among abortion-rights opponents, although several major anti-abortion groups have taken a public stance opposing the prosecution of patients themselves.

In a statement, former Texas state Sen. Wendy Davis, a senior adviser at Planned Parenthood Texas Votes, said abortion-rights activists are "outraged, but we are not surprised" and accused anti-abortion groups of using the courts "as an instrument of fear and intimidation."

The suit comes as a federal judge in Texas is considering a separate lawsuit filed by anti-abortion rights groups seeking to force the Food and Drug Administration to pull mifepristone, a drug used in most medication abortions in the U.S., off the market. A competing lawsuit filed by a group of Democratic state attorneys general seeks to preserve access by prohibiting the FDA from removing the drug.

Medication abortion access increasingly has become the focus of litigation and legislation surrounding the fight over abortion rights in the United States. That's in large part because of its increasing use by patients seeking abortions. More than half of abortions in the U.S. now take place using pills, and pills are often more accessible than surgical procedures for people living in states with restrictive abortion laws.

READ MORE  Even a one-hour change in the clock can disrupt the body's circadian rhythms, especially when the clock 'springs forward.' (photo: Charlie Riedel/AP)

Even a one-hour change in the clock can disrupt the body's circadian rhythms, especially when the clock 'springs forward.' (photo: Charlie Riedel/AP)

The key is to ease into it.

The premise is simple: shift the clocks so people can get the maximum amount of daylight. In the spring, the one-hour change means more daylight in the evening and darker mornings; in the fall, the sun sets earlier while mornings are lighter. But this transition can be more disruptive beyond just losing one hour of sleep. Whether you’re a parent (to humans or pets) or an early riser who hardly enjoys waking in the dark, you can make the transition into daylight saving a little less painful.

“It’s not just a loss of an hour asleep, but we’re getting our light at a whole different time of day,” says Beth Malow, the director of the Vanderbilt Sleep Division at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. “Everything is off by an hour.”

Changing the clock confuses the body

Every process within the body, from sleep to metabolism, runs on an internal clock, known as circadian rhythm. Various cues, like light, trigger the release of hormones alerting the body to wake up, feel sleepy, get hungry. Even if you wake at the same time every day, the shift from standard to daylight saving time means it’s suddenly dark in the morning and your circadian rhythm is disrupted. “The body releases sleep-time and wake-time hormones at a particular time,” says Nilong Vyas, a board-certified pediatric sleep coach, founder of family sleep consulting service Sleepless in NOLA, and medical reviewer for SleepFoundation.org. “When the clock time is different than what the body is feeling or experiencing, we tend to feel a bit off until the body’s hormones re-regulate in a few days.”

Compared to the gradual change in daylight hours leading up to daylight saving time, the abrupt shift is a jolt to the body. All of a sudden, you’re eating, sleeping, and socializing at different times, and the body needs to play catchup. This sudden change has material impacts: Studies have shown that deadly car accidents, workplace injuries, and heart attacks increase following the springtime change.

Usually, people who work during the day and have consistent schedules can adjust within a week, says Jade Wu, author of Hello Sleep: The Science and Art of Overcoming Insomnia Without Medications. Those on the western edges of time zones see later sunrises than people on the eastern areas of time zones, which may make the adjustment more difficult, Malow says, since it’s darker longer in the morning.

Some people are more sensitive to the time change than others. Older people, people with autism, and adolescents may have more difficulty adjusting, Malow says. Genetics can play a role as well. Young children, pets, and others who aren’t aware of the time change are also thrown out of whack.

In the name of consistency, last March, the Senate unanimously voted in favor of making daylight saving time permanent starting this year. This would mean eliminating the “fall back” time change in November (and every other hour shift thereafter). Most of the country would experience sunsets after 5 pm — but later sunrises, too (it would be dark at 7 am most of the year). The bill died in the House last year, but has recently been reintroduced in the Senate. The bill would need to be passed by the Senate, House, and signed by the president to become law.

For those who enjoy more light in the evening, the move toward permanent daylight saving time is ideal, but it may not be the best for human functioning. Between standard time and daylight saving time, Malow has a preference for standard time. “It’s a healthier choice,” she says, because mornings are lighter during standard time. “We know that morning light is really important for our sleep and our moods,” she says. “Light in the afternoon isn’t as effective as light in the morning. If you want people to have natural light, you want them to have more light in the morning and that’s what standard time does.”

How to make the transition from standard time to daylight saving time less jarring

Since the country is stuck with daylight saving time for at least the immediate future, there are ways to ease into the time change. In the weeks leading up to daylight saving time, prioritize your sleep, Malow says, and make sure you’re not sleep deprived before losing an hour of sleep. (The necessary number of hours of sleep varies from person to person, but the CDC recommends adults get between seven and nine hours a night.)

Then, try to go to bed 10 to 15 minutes earlier each night the week before the time changes. “A 10-minute shift is a lot less of a jolt to the system than an hour,” Malow says. But if you’re not sleepy enough for an advanced bedtime, prioritize waking up 10 to 15 minutes earlier, Wu says, since you can more easily control when you rise, not when you fall asleep.

Parents can implement this subtle change in their children’s sleep schedules as well. If they’re resistant to waking up earlier, don’t worry, Wu says — they’ll adjust on their own. “Kids tend to be morning people anyway,” she says. “If the clock shifts one hour, it doesn’t really mess with them that much because they’re still getting up early.” For teens, who are natural night owls and are often sleep deprived, Wu advises parents to guide their teenagers toward less screen time at night and a long wind-down time prior to bed. “If you can, try your best to plan for at least eight hours of sleep knowing that you’re gonna have to wake up at X hour in the morning in the new time,” Wu says.

While infants and pets who aren’t as regimented with their sleep might not be as amenable to a change in when they wake up, parents (to both humans and pets) should still acclimate themselves to a slightly earlier bedtime for an easier transition. Try feeding your pets a few minutes ahead of schedule each day leading up to daylight saving time so they’ll be properly adjusted.

On Sunday morning, fight the urge to sleep in an hour later to compensate for the lost time — wake up around the same time you usually do on Sunday mornings, Malow says. If you typically attend a 9 am yoga class or religious service, keep those plans. Try to get outside in the morning, too, “because that will also reset your clock,” Malow says. Get the family together and go for a walk to ensure everyone gets their dose of daylight. If you have a sunrise alarm clock or a light box, these artificial light sources are also sufficient sources of light and can help get your circadian rhythm back on track, Vyas says.

“The remedy,” Vyas says, “is to ease into the time change so that it is not as jarring for the body when it happens.”

READ MORE  Farm workers on their march from Delano to Sacramento in 1966. (photo: Jon Lewis/Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library/Yale University)

Farm workers on their march from Delano to Sacramento in 1966. (photo: Jon Lewis/Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library/Yale University)

Decades after Cesar Chavez made the union a power in California fields, it has lost much of its clout. Membership dropped precipitously, from 60,000 to 5,500. It hopes a new law will turn the tide.

“Sí, se puede,” she chanted in unison with dozens of other farmworkers, who waved U.S. and Mexican flags as they walked along two-lane roads lined by dense orange groves in the Central Valley of California.

The banner, flags and rallying cry — “Yes, we can” — echoed back more than half a century to when Cesar Chavez, a co-founder of the United Farm Workers union, led agricultural workers on a pilgrimage along a similar route to meet lawmakers in Sacramento.

“We are a legacy of Cesar Chavez,” said Ms. Mota, 47, who, when blisters began to form on her feet during the 24-day trek in August, gathered strength by thinking of how the march in the 1960s led to groundbreaking farmworker reforms and propelled the U.F.W. to national prominence.

“We can achieve what we want,” Ms. Mota said.

What the farmworkers wanted last summer was for Gov. Gavin Newsom to sign into law a bill that they argued would make it easier and less intimidating for workers to vote in union elections — a key step, they believed, in rebuilding the size and influence of a now far less prolific U.F.W. But changing a rule is not the same as changing the game. The question now is whether the U.F.W. can show it has not irretrievably lost its organizing touch and can regain the ability to mobilize public opinion on its behalf as it did under Mr. Chavez.

The union is a shadow of what it was decades ago. Membership hovers around 5,500 farmworkers, less than 2 percent of the state’s agricultural work force, compared with 60,000 in the 1970s. In the same period, the number of growers covered by U.F.W. contracts has fallen to 22 from about 150. The march last summer stood as a reckoning of sorts for a union desperate to regain its relevance.

Labor organizing has rebounded nationwide in the last few years, with unions winning elections at an Amazon warehouse on Staten Island and at least 275 Starbucks stores, and among white-collar workers in the tech and media industries. But in California’s fields, which supply about half of the produce grown in the United States for the domestic market, such efforts have found little traction.

It has been more than five years since the U.F.W. mounted an organizing drive and election petition in the state — at Premiere Raspberries in Watsonville. The U.F.W. unionization vote succeeded, but the company refused to negotiate a contract and in 2020 announced plans to shut down and lay off more than 300 workers.

Ms. Mota, who has worked seasonal jobs around the state for two decades, has seen her wages drop by about $6,000 over the last several years. She is now earning around $15,000 a year. She said that on farms without union contracts, bosses sometimes make veiled threats about cutting hours, refuse to give workers breaks in 100-plus degree weather and turn a blind eye to dangerous conditions.

“Where we do not have a union contract, there is no respect,” she said in Spanish on a recent morning from her ranch-style home in the farming town of Madera.

But the bill backed by Ms. Mota, which Mr. Newsom signed into law after the marchers arrived in Sacramento, has fueled a cautious optimism. Backers say the ability to more freely organize will help them gain more influence.

“There is new energy, new legislation and attention from the public in terms of workers’ rights,” said Christian Paiz, a professor of ethnic studies at the University of California, Berkeley, who has researched farm labor in the state. “We could be on the front lines of a renaissance.”

The Shadow of Cesar Chavez

Farmworkers have, for generations and by design, existed on the fringes of the American work force.

The National Labor Relations Act of 1935 excluded farm and domestic workers from federal protections — a decision, rooted in racism, that ensured that the Black, Latino and Asian people whose work opportunities were largely limited to those two industries were not covered.

But by the 1960s, momentum for change was building.

Mr. Chavez, who was a farm laborer picking avocados and peas before becoming a grass-roots organizer, teamed up with Dolores Huerta, a young workers’ rights activist from the Central Valley, and in 1962 they founded the National Farm Workers Association. It became the U.F.W.

Three years later, it was a key force behind the Delano grape workers’ strike, in which thousands of Mexican and Filipino farmworkers walked off their jobs, demanding raises from $1.25 to $1.40 an hour, as well as elections that could pave the way for unionization.

As the striking farmworkers made their way along the 335-mile trek in 1966, which started in Delano, the group grew steadily, and other unions began to pledge their support.

In the Bay Area, longshoremen had refused to load shipments of grapes that hadn’t been picked by unionized workers and, before long, a statewide pressure campaign had become a national one.

Weeks after the march began, a lawyer for Schenley Industries, a large Central Valley grape grower that was a target of the boycott, contacted Mr. Chavez, and the company soon agreed to negotiate a contract. It officially recognized the U.F.W., making it the first major corporation to acknowledge a farm union.

The grape workers’ strike stretched into the summer of 1970, when widespread consumer boycotts forced major growers to sign on to collective bargaining agreements between the union and several thousand workers.

In the years that followed, Mr. Chavez forged a relationship with Gov. Jerry Brown, a Democrat, and helped champion the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975, which established the right to collective bargaining for farmworkers and created a board to enforce the act and arbitrate labor fights between workers and growers. It was the first law in the country guaranteeing protections to farm workers.

But the union’s gains soon began to erode. Mr. Brown’s Republican successor, George Deukmejian, and his appointees made changes to the farm labor board in the 1980s and cut funding, arguing that the adjustments were necessary to correct an “easily perceived bias” in favor of farm workers and the U.F.W. and against growers. And even when the union has won elections, it has often faced legal challenges from growers that can drag on for years.

The law that Mr. Newsom signed last year, Assembly Bill 2183, was the union’s biggest legislative victory in years. It paved the way for farmworkers to vote in union elections without in-person election sites. For years, U.F.W. officials argued that dwindling membership numbers stemmed from fears about voting in person at sites often held on properties owned by the growers.

The bill faced opposition from growers, who contended that the measure would allow union organizers to unfairly influence the process. Mr. Newsom initially voiced reticence, but signed the measure into law after then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and President Biden publicly pushed him to do so.

“In the state with the largest population of farmworkers, the least we owe them is an easier path to make a free and fair choice to organize a union,” Mr. Biden said at the time.

Supporters of the measure highlight how the demographics of farmworkers have changed over the years. In the 1970s, under Mr. Chavez, many farmworkers were U.S. citizens, but migration from Mexico and Central America in the decades that followed created a work force composed primarily of undocumented workers. Because they lack immigration papers, supporters say, they are especially vulnerable. (Undocumented workers can be covered by labor agreements.)

In signing the measure, Mr. Newsom and the U.F.W. agreed to support follow-up compromise legislation that would guard farmworker confidentiality during elections and place limits on card-check voting, a method in which employees sign cards in favor of unionizing.

‘We Are Ignored’

Last summer, as she marched past vineyards and groves of mandarin oranges, Ms. Mota thought of the harvest cycle that has defined much of her life.

She reflected on the dormant season, in December and January, when she prunes pistachio and almond trees, and the rainy months, when it’s sometimes hard to find work. But then comes the prosperous citrus and grape harvests, through the spring and the fall, which always make her think of the families who will eventually toast with wine squeezed from the fruit she plucked from the vine.

“I love for my hands to harvest a fruit and then seeing those fruits and vegetables in the restaurant,” Ms. Mota said.

She thought, too, about the invisibility and dangers of her work — the tiny teeth marks etched into her leather boot by a snake bite, the molehill where she badly sprained her ankle, the co-worker airlifted to San Francisco with injuries.

“We are ignored,” she said.

Still, she didn’t feel that way during the march, where in many towns people greeted them with snacks, Gatorade and full meals. While the group was in Stockton, an inland port city, Ms. Huerta, now 92, stood before the crowd wearing a baseball cap emblazoned with the words, “Sí se puede.”

“You all have made me so proud,” she told them.

Ms. Huerta, who helped negotiate the first farmworker contract with Schenley, left U.F.W. leadership more than two decades ago to pursue other causes. But in an interview, she said the need for unionization remained as high as it was when she helped start the union.

“Farmworkers wanted the support and still want the support,” said Ms. Huerta, who attributed the dearth of contracts to a refusal by growers to bargain in good faith.

Despite setbacks in recent decades, U.F.W. officials say they have continued to secure contracts that focus on health care benefits, wage increases and cultivating a respectful culture between farmworkers and employees. At Monterey Mushrooms, which has operated under a contract since the 1980s, U.F.W. officials say the average annual income for a mushroom picker is $45,000 and includes vacation time and a pension. (The statewide average for farmworkers is between $20,000 and $25,000 a year, according to the U.S. Labor Department.)

“With a union contract, workers are educated about their rights and empowered to defend them,” said Teresa Romero, the union’s president.

Issues might vary from farm to farm, Ms. Romero said. “In one workplace it may be low wages, in another it may be unsafe conditions, in still another it may be the workplace culture — having to pay bribes or endure sexual harassment to get work or having a particular supervisor who is racist or cruel,” she said. “We understand the immense risks that workers are taking when speaking up on the job; it takes courage for workers to form their union.”

Ms. Romero said she was confident that the new state law — along with a streamlined federal process to protect workers involved in labor disputes surrounding immigration threats from employers — would translate into more bargaining power and more contracts.

A Question of Strategy

Some labor watchers are skeptical of the union’s ability to reinvigorate itself.

Miriam Pawel, an author who has written extensively about the union and Mr. Chavez, said the U.F.W.’s decline reflected a shortfall in organizing efforts in the communities where farmworkers live.

“It’s evolved more into an advocacy organization and walked away from the more difficult work of organizing,” Ms. Pawel said. Referring to the 1975 labor relations act, she added, “They have the most favorable labor law in the country and have barely taken advantage.”

Ms. Pawel cited a 2016 state law mandating that agricultural employers pay overtime if people worked more than eight hours in a day. The union lobbied for the measure, but growers warned that they couldn’t afford to pay overtime and would adjust schedules to avoid doing so. The new overtime rule has been phased in over the years, and some farmworkers have voiced anger about losing hours.

“If the union were stronger in the fields, and at organizing, it could have won elections and demanded better overtime provisions in contracts,” Ms. Pawel said.

Ms. Romero pushed back against such criticism, arguing that, until Mr. Newsom signed A.B. 2183 in September, many farmworkers had justified fears that, if they sought unionization, their bosses would fire them or even try to get them deported.

Indeed, a report by the University of California, Merced, Community and Labor Center found that 36 percent of farmworkers said they would not file a report against their employer for failing to comply with workplace safety rules and that 64 percent cited fear of employer retaliation or job loss.

And since the bill’s passage, the Farm Employers Labor Service, a trade group that staunchly opposed the law, has placed advertisements on Spanish-language radio stations, warning about what it means to be in a union. In one ad, a man shouts: “Signing a union petition can lead to the union stealing 3 percent of your salary! Do not let them!”

Those messages deeply concern Ms. Romero.

“Filing for an election when workers are not protected from genuine risks of retaliation will only lead already poor people into further hardship,” she said. “This is the implicit threat that the growers’ power depends on.”

‘They Just Want to Work’

Many California growers say they can be better bosses without unions.

On a recent afternoon off Interstate 5 in the small city of Firebaugh, Joe Del Bosque stared out at bare fields on the melon farm he has owned since 1985. A thick fog hung over the area, and the ground was puddled from rain water. It was the quiet season on the farm, where he employs more than 100 farmworkers annually.

Mr. Del Bosque said that when he was a boy, his parents, legal U.S. residents, traveled from a town near the California-Mexico border to the Central Valley to pick melons every summer. As a farm owner, he has never had a union contract, and aims to keep it that way.

He provides his employees with good conditions and fair wages, he said, without their having to pay union dues. “From my experience, workers who are moving around from season to season do not want the extra hands involved,” he said of the union. “They just want to work.”

He said he had little trouble finding field hands, including migrants who move from farm to farm with each season. And he noted that in the Salinas Valley — closer to the coast, where housing is more expensive — many growers rely on H-2A visas, which let them bring workers, often from Mexico, for just a few months of the year.

That impermanence, he said, works against the U.F.W. “If the workers are here only a few months a year and then leave the state, how are you going to organize?” he said.

Mr. Del Bosque said that he respected the U.F.W.’s history and the groundwork of Mr. Chavez and Ms. Huerta, but that he opposed A.B. 2183. The law, he contends, will allow the U.F.W. to unfairly sway farmworkers at their kitchen tables and behind closed doors.

“That’s the intimidation factor,” Mr. Del Bosque said.

A New Spirit of Activism

While the impact of the law remains unclear, it has buoyed the spirits of some farmworkers.

Asuncion Ponce started harvesting grapes along the rolling green hills of the Central Valley in the late 1980s. Through the decades, Mr. Ponce has worked on several farms with U.F.W. contracts. Bosses on those farms, he said, seemed aware that if they harassed or mistreated workers, the union would step in.

“They don’t mess with you any more,” he said, “because they think there could be problems.”

Even so, he has seen his financial security decline. He averaged $20,000 a year in the 1990s and 2000s, he said, but these days he brings in around $10,000 a year picking grapes and pruning pistachio trees. His eight-hour shifts are no longer supplemented by overtime, as growers have cut hours — partly as a result of the overtime bill U.F.W. leaders supported.

Occasionally, Mr. Ponce said, he relied on third-party contractors, who growers sometimes employ, to find him available work. But he said he was optimistic that with the new legislation he would land a full-time job on a union farm.

On a recent evening, the 66-year-old sipped coffee and decompressed after a shift at a farm outside of Fresno. His feet ached and his flannel shirt was stained with fertilizer, but he is happy that his job lets him spend all day outdoors — a passion born in his hometown in the Mexican state of Puebla, where he harvested corn and anise.

He smiled softly under his white mustache as he spoke about the legacy of Mr. Chavez, which inspired him to join for several legs of the pilgrimage last summer.

“I marched for many reasons,” he said in Spanish. “So we are not as harassed and mistreated as we are now in the fields, so benefits and better treatment come our way.”

For Ms. Mota, joining the march helped awaken a new spirit of activism.

Over the years, she said, she felt afraid to talk about unionizing at work, but now she tells any colleagues who will listen about the advantages she sees: the ability to negotiate a better salary, benefits and a respect for seniority.

Her viewpoint was shaped in her early years as a farmworker. “Throughout the years I have realized that we are marginalized,” she said. “They don’t value us.”

Once, she said, she watched as a farmer grabbed a knife used to harvest cantaloupe and put it to the cheek of another worker. He glared into the farmworker’s eyes, she said, and called the workers his slaves.

“You feel humiliated,” she said, fighting back tears.

She is convinced that having a strong union is the only answer. “We deserve a dignified life in this country,” she said.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.