Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Feels like this should make for a particularly uncomfortable vibe at the next family gathering!

Obviously, that result would be extremely embarrassing for the Trumps, which is probably why both Don Sr. and his eldest daughter have asked for the start date to be delayed. For his part, lawyers for the ex-president (and current presidential candidate) have argued that the evidence would take 11,000 hours to review, and that the trial should be pushed back six months. As for Ivanka? Her legal team took a slightly different approach.

Per The Independent:

In court documents, Ms. Trump’s attorneys argue that the fraud complaint filed last year against her and her codefendants by New York attorney general Letitia James “does not contain a single allegation that Ms. Trump directly or indirectly created, prepared, reviewed, or certified any of her father’s financial statements.”

“Other individuals were responsible for those tasks,” her lawyers wrote.

The “other individuals” accused in the case are her father and brothers, so this comes off…rather awkwardly, and the takeaway from The Independent was that the former first daughter threw her siblings and dad “under the bus.” Setting all that aside, it’s also pretty odd that her lawyers are arguing that the lawsuit does not include a single allegation in which “Ms. Trump directly or indirectly created, prepared, reviewed, or certified any of her father's financial statements,” when the AG’s office has flatly accused her of being in on the alleged scam. To wit, James’s office claims in the suit that all three Trump kids “knowingly participated” in the scheme. Of Ivanka specifically, the lawsuit notes her involvement in securing loans to buy Florida and Chicago properties in 2012, loans that were issued in part due to false financial statements. “On each of those transactions with Deutsche Bank, Ms. Trump was aware that the transactions included a personal guaranty from Mr. Trump that required him to provide annual Statements of Financial Condition and certifications,” the lawsuit reads. (Elsewhere, the suit points to the Trump Organization’s deal obtaining a ground lease for its Washington hotel, noting that project was “captained by Ivanka Trump, and Mr. Trump’s statements were central to their effort to win the bid.“)

Anyway, it’s not clear at this time if the judge overseeing the case will be convinced to delay the trial. In a letter made public on Friday, he wrote: “The core of this case is very simple: plaintiff claims that defendants submitted false financial statements to third-parties…. It is their own alleged documents and acts that are at issue…. October 2, 2023 is more than seven months away.” He added, “And with all that has already been accomplished, I see no reason to alter my determination to start the trial on that day.”

READ MORE  Amanda Zurawski, one of five plaintiffs in Zurawski v. State of Texas, speaks in front of the Texas State Capitol in Austin, Texas, Tuesday, March 7, 2023. (photo: Sara Diggins/AP)

Amanda Zurawski, one of five plaintiffs in Zurawski v. State of Texas, speaks in front of the Texas State Capitol in Austin, Texas, Tuesday, March 7, 2023. (photo: Sara Diggins/AP)

The first-of-its-kind lawsuit seeks to affirm that doctors can use their best medical judgment without fear of criminal penalty.

“It sounds like a pretty sick and twisted plot to a dystopian novel,” she continued. “But it’s not. It’s exactly what happened to me while pregnant in Texas.”

Zurawski and her husband had known each other since preschool. They married in 2019 and were excited to start a family. After months of fertility treatments, Zurawski learned she was pregnant. The couple was beyond thrilled; they decided to name their daughter Willow. Zurawski was “cruising though” her second trimester, she said, and had just finished the invite list for her upcoming baby shower when everything changed. She developed “unexpected and curious” symptoms. Her obstetrician told her to come in right away. After an examination, the couple received the “harrowing news” that Zurawski’s cervix had dilated prematurely. Later her water broke; because Zurawski’s pregnancy was still weeks from viability, there was no chance Willow would survive.

“I asked what could be done to ensure the respectful passing of our baby and … protect me from a deadly infection,” she recalled. Nothing could be done, she was told, because of Texas’s abortion bans.

Zurawski is one of five Texas women who are plaintiffs in a lawsuit that the Center for Reproductive Rights filed against the state this week. The lawsuit argues that the state’s various abortion bans, which contain only vague exceptions in cases of medical emergency and impose both civil and criminal penalties if violated, have caused confusion and sparked fear among medical professionals, putting pregnant people’s lives in danger.

“What the law is forcing physicians to do is to weigh … very real threats of criminal prosecution against the health and well-being of their patients,” Nancy Northup, CEO of the Center for Reproductive Rights, said during the Tuesday afternoon press conference. The lawsuit seeks to stop the “unnecessary pain, suffering, injury, and life-threatening complications caused by Texas’s abortion ban.”

The lawsuit asks a state district judge to clarify the scope of the medical emergency exception and affirm that physicians can provide abortion care when an emergency condition arises. It is the first lawsuit of its kind, Northup said, “in which individual women have sued a state for the harm that they endured because abortion care has been criminalized in the wake of Roe’s reversal.”

Zurawski’s doctor said her pregnancy could not be terminated until there was no longer fetal cardiac activity or her health had deteriorated enough that the ethics board at the hospital would allow an abortion. “I cannot adequately put into words the trauma and despair that comes with waiting to either lose your own life, your child’s life, or both,” she said. “For days I was locked in this bizarre and avoidable hell.” Zurawski developed life-threatening sepsis; only then did the hospital agree that she was sick enough to qualify for abortion under Texas law. “What I needed was … a standard medical procedure,” she said. “An abortion would have prevented the unnecessary harm and suffering that I endured.”

Confusion and Intimidation

By the time the U.S. Supreme Court issued its ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization last June — which overturned Roe v. Wade and eliminated a half-century of constitutional protection for abortion — Texas politicians had already codified two abortion bans. During their 2021 biennial legislative session, lawmakers passed Senate Bill 8, a six-week ban that sidestepped constitutional oversight by outsourcing enforcement to vigilantes empowered to bring civil suits against health care providers or anyone else they believed might have aided a patient seeking an abortion in violation of the law. Lawmakers also passed a so-called trigger ban, a complete ban on abortion that took effect in August 2022, shortly after Roe’s demise.

Theoretically at least, each of the Texas bans has an exception for cases involving medical emergencies. But according to the new lawsuit, the laws don’t use standard medical terminology, and what exactly counts as a medical emergency is vague. “Inconsistencies in the language of these provisions, the use of non-medical terminology, and sloppy legislative drafting have resulted in understandable confusion throughout the medical profession regarding the scope of the exception,” the lawsuit reads. While the exception appears multiple times in the state’s health and safety code, conflicting language leaves “physicians uncertain whether the treatment decisions they make in good faith, based on their medical judgment, will be respected or will later be disputed.”

And that is a serious problem given the extreme penalties for violating Texas’s abortion bans. Doctors who violate the trigger law, for example, face revocation of their license, a civil penalty of at least $100,000 per violation, and, if criminally charged, up to 99 years in prison.

To date, abortion is banned in 13 states, including Texas. Medical exceptions in those states vary, and some have none at all, providing only a list of possible defenses a physician can assert if they are prosecuted. Physicians have long warned that these exceptions are vague and place patients in danger. Stories of pregnant people denied abortion care despite suffering from serious medical complications or carrying a fetus with a fatal diagnosis have made news across the country, but they have prompted few, if any, attempts to better define exceptions to the bans.

During his 2022 reelection campaign, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott told Inside Texas Politics that he’d seen some situations in which pregnant people were not getting the heath care they needed to protect their lives. “There’s been too many allegations that have been made about ways in which the lives of the mother are not being protected, and so that must be clarified.” Although the Texas Legislature convened in January, no action has been taken to remedy the problem. A spokesperson for Attorney General Ken Paxton told the Associated Press that Paxton is “committed to doing everything in his power” to defend the laws as written.

Meanwhile, anti-abortion groups have pushed back on the notion that the bans they advocated for need any clarification, suggesting that where patients like Zurawski are concerned, doctors are simply being negligent. That’s exactly what the Texas Alliance for Life did in the wake of the center’s lawsuit. “Tragically, some physicians are waiting until their patients are nearly dead before performing a life-saving medical procedure,” Amy O’Donnell, the group’s communications director, said. “We see situations when pregnant women do not promptly receive treatment for life-threatening conditions as potential medical malpractice issues.”

“You Need to Leave the State”

In the face of legislative inaction, the new lawsuit seeks to have a judge step in and declare that doctors have the right to exercise their best medical judgment — and that they won’t face penalties for doing so. It also argues that the Texas Constitution guarantees fundamental rights that don’t disappear simply because a person is pregnant. “Texas law cannot demand that a pregnant person sacrifice their life, their fertility, or their health for any reason, let alone in the service of ‘unborn life,’ particularly where a pregnancy will not or is unlikely to result in the birth of a living child with sustained life,” it reads.

Three additional plaintiffs in the center’s lawsuit were also on the Capitol grounds Tuesday. Like Zurawski, they shared stories of wanted pregnancies that ended in heartbreak amid a nightmare of trying to access necessary abortion care in Texas.

Lauren Hall was nervous about becoming a parent, but excited, she told reporters. Then, when she was 18 weeks pregnant, an anatomy scan revealed anencephaly; her fetus was not growing a skull and had little brain matter. Her husband held back tears when he asked the doctor what they should do. The doctor hesitated. Wait to miscarry or leave Texas for an abortion, the couple was told. The doctor warned that if they chose to leave Texas, they should not tell anyone where they were going or why, and she couldn’t refer Hall to an out-of-state provider or even transfer her medical records; under Senate Bill 8, no one knew how far Texas would go to prosecute people involved in abortion care. Hall and her husband made their way to Seattle, where she finally received the medical intervention she needed. Hall recalled protesters outside the clinic, “calling us killers and waving pictures with dead babies at us.”

Lauren Miller already had a young son when she found out she was pregnant with twins. She and her husband were excited. They started calling the twins “Los Dos,” and every night, her husband would give her two kisses on the belly, “one for each.” But Miller began suffering from debilitating nausea and vomiting. At 12 weeks, she found out that one of the fetuses had two large fluid masses developing where his brain should be. The fetus had an often-fatal genetic abnormality, and later scans revealed “one heartbreaking issue after another.” Miller’s medical providers seemed to be searching for words when trying to counsel her about her options, she said. Finally, one specialist tore off his gloves and threw them in the trash: “I can’t help you anymore,” she recalled him saying. “You need to leave the state.”

That’s what she and her husband decided to do. She wanted to just “curl up and cry and mourn,” but instead, she had to scramble to find care to give the other twin “and myself the best chance of surviving this pregnancy.” She and her husband felt lost, she said, “like we were in a dark room feeling for a door.” She noted that while she had the resources to access the care she needed out of state, others might not be as fortunate. “Layers of privilege should never determine which Texans can get access to the health care they need.”

Anna Zargarian was surprised to find out she was pregnant. It was September 2021, just after S.B. 8 had gone into effect, and she remembered “naively” thinking that it was a good thing she wouldn’t need an abortion. Two months later, Zargarian’s water broke; her amniotic fluid was gone, and she was told the baby would not survive. On the Capitol lawn, Zargarian began to cry as she recalled getting the news. “My heart broke into a million pieces,” she said. “I didn’t even know a pain like that could exist until that moment.” Under the provisions of S.B. 8, she wouldn’t be able to get the care she needed in Texas until “my life was actively in danger,” she said. “I couldn’t understand what was going on.” She fled to Colorado for care. “Where else in medicine do we do nothing and just wait to see how sick a patient becomes before acting?”

A reporter at the press conference asked how the women felt now, filing this case together after going through such an isolating ordeal. To be clear, Zurawski said, none of the women wanted to be there: “We have all become involuntary members of the most horrific club on the planet.” And they were just a small representation of “countless others” in Texas and around the U.S. who have gone through similar trauma. “Being together is powerful, but it’s also traumatic knowing that there are so many people who are going through this,” she said. “And I think that’s why we’re all here.”

READ MORE  In this 2018 photo made from footage taken from the Russian Defense Ministry's official website, a Russian Kinzhal hypersonic missile flies during a test in southern Russia. (photo: AP)

In this 2018 photo made from footage taken from the Russian Defense Ministry's official website, a Russian Kinzhal hypersonic missile flies during a test in southern Russia. (photo: AP)

ALSO SEE: What Are the Hypersonic Missiles Russia Is Using in Ukraine?

In an early morning attack on targets across the country, Russian forces apparently added several hypersonic missiles, known as Kinzhals — or "Daggers" in Russian — to the lethal mix. Ukrainian forces say their defensive capabilities are not up to the task of taking out a Kinzhal.

Six Kinzhals were included in Thursday's attack, according to Ukrainian defense forces. Although Russia has used these weapons before, in the opening weeks of the conflict, Yuriy Ignat, an air force spokesman, told Ukrainian TV that the enemy had never fired so many of them in a single attack. Ignat said only 34 of the 81 total incoming Russia missiles were shot down.

Hypersonics pose a serious challenge to air defenses

Hypersonic missiles such as the Kinzhal are a fairly new breed of weapon that combine superior speed with the ability to maneuver to evade being shot down. Not only are they difficult to detect, but they make radical and unpredictable course changes as they get close to a target.

The Kinzhal, unveiled by Russian President Vladimir Putin five years ago, can accelerate to Mach 4 — four times the speed of sound — and may be capable of speeds of up to Mach 10, with a range to about 1,250 miles. The missile is also believed to be nuclear-capable.

An even more sophisticated weapon, Russia's Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle, can fly at speeds as high as Mach 27, according to the Kremlin. Another hypersonic, the Zircon anti-ship missile, has also reportedly been developed, but there are no reports of the Zircon or Avangard being used in combat.

There's debate over how much of a game changer they are

The Kinzhal "is launched from an aircraft and has a shorter range than Avangard," according to James Acton, co-director of the nuclear policy program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

But last year, after the first reported use of the Kinzhal in Ukraine, Acton downplayed the significance of the weapons as a "game changer" in the conflict.

"I don't know how much of an advantage Russia is getting from using hypersonic missiles," he told the BBC.

That is a sentiment largely echoed by U.S. Northern Command chief Air Force Gen. Glen VanHerck. Last May, VanHerck told a Senate Armed Services strategic forces subcommittee that Russia was having "challenges with some of their hypersonic missiles as far as accuracy" in Ukraine.

However, Victor Cha, who served on the National Security Council during the George W. Bush administration, told NPR last year that hypersonics could pose a real challenge — even to U.S. missile defense systems. At the time, Cha was referring to hypersonic missiles being developed by North Korea. U.S. missile defense systems are "good," he said, but they are mostly "geared towards stopping a handful of fairly primitive missiles from North Korea." Those systems dwarf the type of defenses that Ukraine is using in the fight against Russia.

"[T]hey would need to be improved to be able to handle more sophisticated sorts of missiles," Cha said.

The Pentagon, too, has expressed some urgency on the subject. Last year, Dee Dee Martinez, comptroller of the U.S. Missile Defense Agency, said hypersonic missiles "pose a new challenge to our missile defense systems."

"The development and deployment of missile defense systems to counter these advanced threats presents unique, but surmountable challenges, which require further development and technology investments," she said.

READ MORE  Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders, R-AR, waits to deliver the Republican response to President Biden's State of the Union address on Tuesday in Little Rock, Arkansas. Sanders signed a law this week making it easier to employ kids under 16. (photo: Al Drago/AP)

Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders, R-AR, waits to deliver the Republican response to President Biden's State of the Union address on Tuesday in Little Rock, Arkansas. Sanders signed a law this week making it easier to employ kids under 16. (photo: Al Drago/AP)

Effectively, the new law signed by the Republican governor applies to those who are 14 and 15 years old because in most cases Arkansas businesses can't employ those under 14.

Under the Youth Hiring Act of 2023, children under 16 don't have to get the Division of Labor's permission to be employed. The state also no longer has to verify the age of those under 16 before they take a job. The law doesn't change the hours or kinds of jobs kids can work.

"The Governor believes protecting kids is most important, but this permit was an arbitrary burden on parents to get permission from the government for their child to get a job," Sanders' communications director Alexa Henning said in a statement to NPR. "All child labor laws that actually protect children still apply and we expect businesses to comply just as they are required to do now."

Workers under 16 in Arkansas have had to get these permits for decades.

Supporters of the new law say it gets rid of a tedious requirement, streamlines the hiring process, and allows parents — rather than the government — to make decisions about their children.

But opponents say the work certificates protected vulnerable youth from exploitation.

"It was wild to listen to adults argue in favor of eliminating a one-page form that helps the Department of Labor ensure young workers aren't being exploited," the group Arkansas Advocates for Children and Families wrote about the law in a legislative session recap.

Arkansas isn't the only state looking to make it easier to employ kids in a tight labor market and fill an economic need. Bills in other states, including Iowa and Minnesota, would allow some teenagers to work in meatpacking plants and construction, respectively. New Jersey expanded teens' working hours in 2022.

But the bills are also occurring alongside a rising tide of minors employed in violation of child labor laws, which have more than tripled since 2015, and federal regulators have promised to crack down on businesses that employ minors in hazardous occupations.

There's no excuse for "why these alarming violations are occurring, with kids being employed where they shouldn't even be in the first place," Jessica Looman, principal deputy administrator of the Wage and Hour Division, told NPR in February.

Investigators from the Department of Labor found hundreds of children employed in dangerous jobs in meatpacking plants. Last month, Packers Sanitation Services paid a $1.5 million fine — the maximum amount — for employing 102 children to work in dangerous meatpacking facility jobs.

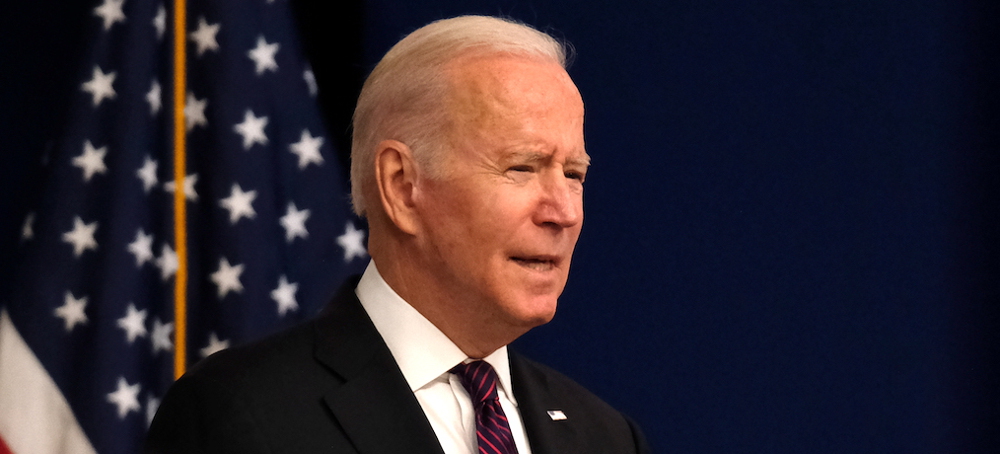

READ MORE  Joe Biden is refusing asylum to migrants who did not first seek protection in the countries they traveled through to reach the United States. (photo: U.S. Department of the Interior)

Joe Biden is refusing asylum to migrants who did not first seek protection in the countries they traveled through to reach the United States. (photo: U.S. Department of the Interior)

The Biden administration’s recently announced change to border policy effectively resurrects Donald Trump’s asylum ban. It will cause harm or suffering to thousands or millions of migrants seeking survival in the US.

Even with the low bar for reform set by the Biden White House, the announcement is a betrayal. It’s a cruel, needless decision that will cause harm and suffering to thousands or perhaps millions of people seeking survival in the United States. The United States received over 202,000 asylum affirmative applications in 2022 alone, plus another 68,300 defensive claims from migrants in deportation proceedings.

Biden’s asylum ban appears to be another instance of the Democrats’ cherished strategy of losing to the Republicans by implementing slightly weaker versions of the latter’s policies. But the bipartisan war on migrants points to a more profound crisis, indicating the destabilization of the conditions that, for decades, have structured the uneven movement of capital and labor across the US border.

Changing Enforcement Logics

US recourse to migrant containment, border militarization, and mass deportation is nothing new. In the decades prior to the global financial crisis, however, these methods were deployed more in the service of exploitation than expulsion.

Mass migration has been constitutive of neoliberal restructuring on both sides of the border. The fallout from US-imposed structural adjustment and free trade displaced vast sectors of the Mexican and Central American working class, peasant, and indigenous populations, whose devalued labor fueled the deindustrializing US economy. Migrant remittances, in turn, came to represent up to a quarter of GDP in countries like El Salvador.

In this context, the progressive criminalization of migration since the 1980s did not serve so much to expel or exclude migrant workers as to ensure they would be more severely exploited in segmented US labor markets.

Until recently, this arrangement suited capital just fine. Companies were free to reap extraordinary surplus from criminalized migrant labor in services, construction, and agriculture in the United States, while those workers’ remittances supplemented the poverty wages paid out to their families back home by the multinationals exporting palm oil or subcontracting to the region’s maquiladoras and call centers.

But in the extended period of instability and crisis since the 2007 market crash, this asymmetrical but mutually sustaining relationship between the United States and its neighbors has been unsettled. In the wake of the financial crisis, US deportations have reached unprecedented heights, and Democratic and Republican administrations alike have advanced policies to fortify what Mike Davis called the “Great Wall of Capital” between the United States and its neighbors.

Changing Migrant Populations

The last fifteen years has seen dramatic changes in the material conditions in which working people make their lives on both sides of the border. These transformations are reflected in the numbers, composition, and strategies of migrants arriving at the US southern border.

The Great Recession and its aftermath had a disproportionate impact on the labor markets that long relied heavily on the exploitation of racialized and criminalized migrant labor, such as construction and hospitality. The service sector, especially restaurants and hospitality, took another devastating hit during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Many Mexican migrants, especially undocumented workers, left the United States during the recession. As Mexican migration declined, however, migration from elsewhere in Latin America began to climb, propelled by converging crises of economic downturn, ecological collapse, and the global pandemic.

As a result, the population intercepted at the US-Mexico border is no longer dominated by single, job-seeking Mexican men. Instead, US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) data is increasingly made up of asylum-seeking women, children, and families from Central and South America and the Caribbean.

CBP euphemistically registers those detained or turned away at the border as “enforcement encounters.” “Encounters” with people from the northern Central American nations of Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador, on the rise since 2011, surpassed those from Mexico for the first time in 2017. From just under sixteen thousand “unaccompanied minors” intercepted in 2011, CBP registered over seventy-six thousand in 2019, 83 percent of them from northern Central America. Women, who comprised 13 percent of southwest border “encounters” in 2011, made up 63 percent in 2019.

The COVID-19 pandemic further destabilized these trends. Overall numbers spiked, with CBP interceptions topping 2.3 million in 2022 — up from 1.7 million in 2021 and 850,508 in 2019.

The makeup of migrant populations has also shifted in the pandemic’s wake. In 2022, northern Central Americans comprised just under 23 percent of “encounters,” with Mexicans at 34 percent. The largest group, 42.6 percent, came from elsewhere, led by asylum seekers from Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela, where US sanctions have multiplied the destructive effects of the pandemic and impeded recovery.

Two Steps Back

These evolving material realities form the backdrop against which the struggle over US immigration policy has played out in recent years. Each concession wrung out of the government by movements for migrant justice has been accompanied by an uptick in repression at the border.

Title 42 is a case in point. Over 2.5 million asylum seekers have been turned away or deported since the Trump administration initiated Title 42 expulsions under public health pretenses in March of 2020.

The Biden administration worked half-heartedly to terminate the emergency mechanism, finally setting a date for its expiration this spring. Title 42 is scheduled to end on May 11, but now it will be replaced with something more permanent: Biden’s new asylum ban takes effect the same day.

Even as it prepared to abandon Title 42, the White House expanded it in January to include the expulsion of migrants from Venezuela, Haiti, Cuba, and Nicaragua into Mexico, while exempting those from Ukraine. To soften the blow, the administration simultaneously announced a two-year “humanitarian parole” program from migrants from those four countries who could claim financial sponsors in the United States. Monthly applications would be capped at thirty thousand; CBP intercepted 77,034 migrants from Cuba and Nicaragua in December alone.

This humanitarian half-measure joins programs like Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and Temporary Protected Status (TPS) in a patchwork of provisional executive shields from deportation for an exceptional few. While Joe Biden quietly abandoned modest immigration reform in the Senate, he expanded TPS to include qualified migrants from Afghanistan, Cameroon, Ukraine, Venezuela, Myanmar, Syria, Sudan, South Sudan, and Yemen and renewed the provision for those from El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, and Nicaragua.

TPS-holders receive lawful work permits but no pathway to legal permanent residency. A matter of Department of Homeland Security discretion, TPS must be renewed every eighteen months. Like DACA recipients, beneficiaries are subject to stringent screening and scrutiny, as well as perpetual uncertainty and instability.

For sociologist David Feldman, these trends suggest a “nascent project of militarized migration management.” This strategy couples scorched-earth tactics at the border with the designation of flexible “pools of authorized — yet ultimately deportable — noncitizen workers subject to a wide array of restrictions and surveillance” that can more rapidly adapt to the changing demands of capital.

The Root of the Problem

In this context of crisis and contradiction, US foreign policy toward Latin America is increasingly framed in terms of addressing the “root causes” of migration.

Root-causes discourse emerged in the context of the US-made Central American child migrant crisis of 2014. The media frenzy spawned a slew of policy proposals for US aid and investment in the region, each less ambitious than the last.

Barack Obama led the charge with the “Alliance for Prosperity.” The plan, which then vice president Biden called a “Plan Colombia for Central America,” incentivized foreign investment and conditioned US aid on Central American border militarization and compliance with deportations. Under Trump, these State Department–led initiatives took a backseat to explicitly military priorities.

Back in the White House again, Biden has now tasked Vice President Kamala Harris with heading up the US approach to Central America. After dispatching the vice president to Guatemala to issue her notorious “Do Not Come” mandate, the White House debuted a “Strategy to Address the Root Causes of Migration in Central America” that identified economic insecurity and inequality, corruption, human and civil rights violations, criminal activity, and gender violence as factors contributing to migration.

Under this framework, Harris’s Partnership for Central America (PCA), an NGO led by a former McKinsey partner, claims to have secured $4.2 billion in commitments for private sector investment in the region from companies like Meta, Microsoft, Nestlé, and Pepsi. PCA initiatives include a “strategic partnership” with the Canadian firm Diversio, “the world’s first AI DEI [diversity, equity, and inclusion] analytics platform” with the goal of furthering “gender parity in supply chains.”

These self-serving efforts fall short of the reparations due to the region for the bloody history of US counterrevolutionary violence. To the contrary, they continue to position Central America as a site for US appropriation and extraction, reproducing the isthmus’s subordinate position in a US-led globalized economy and, by extension, intensifying the very processes of displacement and dispossession that they profess to prevent.

But even the best-intentioned of Democratic policy interventions miss a critical point. Liberal development discourse identifies the “root causes” of mass migration as deficiencies located within Central American societies. This is an old story, with roots in colonization and a pedigree that runs squarely through Walter Whitman Rostow’s 1960 Stages of Economic Growth. This framing posits the conditions associated with underdevelopment as a regrettable stage prior to economic development, which can be overcome through the judicious application of the appropriate public policies.

The reality, however, is that Central America’s so-called underdevelopment is the necessary outcome of development in countries like the United States. These are inseparable histories of accumulation and exploitation that structure the uneven development of the capitalist world system. This is true of the historical relationship between Latin America’s colonization and European industrialization, but it’s also true of the patterns of mass Latin American migration that have powered the US economy throughout the neoliberal period.

Post-pandemic, Central American migrants have been outnumbered by those fleeing crises compounded by US sanctions in Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua. These developments suggest that any efforts to remedy the disparities between the United States and its southern neighbors must also include relief from the suffocating impacts of sanctions. The real root causes of migration lie in these imperialist relations of dependency.

The War on Migrants

Instead of the typical sixty, the Biden administration has limited the public comment period on the asylum ban to thirty days. This move has done nothing to suppress the widespread outcry from migrant justice organizations and advocates, who have unanimously condemned the ban as illegal, racist, and inhumane.

Biden might have acted on his promise to expand asylum criteria to better meet the human rights and humanitarian needs at the border. Instead, he has continued the imperialist assault on the racialized poor, while carving out temporary and contingent categories of relief for a small few.

READ MORE  Ilopango women's prison on the outskirts of San Salvador where women have been held on abortion-related charges. (photo: Ali Rae/Al Jazeera)

Ilopango women's prison on the outskirts of San Salvador where women have been held on abortion-related charges. (photo: Ali Rae/Al Jazeera)

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh, as we end today’s International Women’s Day special looking at abortion bans. Five women are suing Texas after they were denied abortions, even as their pregnancies posed serious risks to their health and were nonviable, in the first such lawsuit since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade.

This comes as women’s rights activists Monday called for the Inter-American Court of Human Rights to condemn El Salvador’s total ban on abortions, which has been in place since 1998. The demands center on a case brought a decade ago by a woman, Beatriz, who died after being forced to carry a pregnancy although the fetus could not survive.

For more, we’re joined by Celina Escher, a Salvadoran Swiss filmmaker who directed the award-winning documentary Fly So Far about the criminalization of abortion in El Salvador, where dozens have been convicted and imprisoned after having miscarriages, stillbirths and other obstetric emergencies.

Celina, welcome back to Democracy Now! It is great to have you with us. We look from the United States to El Salvador. Is El Salvador the United States’s future? Talk about the total ban, but also the resistance.

CELINA ESCHER: Hello, Amy. Thank you for having me.

Yes, exactly. In El Salvador, well, abortion is still criminalized. There is no possibility to have an abortion in El Salvador. Women are still criminalized and in prison. But there is a big resistance still happening in El Salvador, although we’re living in a state of exception since one year. People have lost their human rights, and people are being unjustly incarcerated in El Salvador. There’s a big movement who try to legalize abortion in four cases, and also in three cases, but now a feminist leader, Gloria Peña, she’s facing a lawfare. She’s being persecuted. And she’s the woman who was also in my film. She wanted to legalize abortion in four cases, and now she is facing a persecution, political persecution. So, in general, there is an authoritarian regime happening in El Salvador, and feminist activists, journalists, dissident voices, everybody is under threat. Everybody is being persecuted. And yeah, this is really a difficult situation that people are facing in El Salvador right now.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Celina, could you talk about what happened with the release of your film, which was banned in El Salvador, and the stories that you hear from people who are featured in the film, if you could elaborate on those?

CELINA ESCHER: Yes, exactly. Well, last year in August, we wanted to have the cinema premiere in El Salvador. We have shown our film in 19 international film festivals, so we decided to launch the — to have the cinema premiere. But then, anti-choice organizations, 12 organizations, made a legal threat to the cinema. If they show our film in the cinema, they will make a legal threat. So, then, the cinema had to take down our film, and so we didn’t have the cinema premiere.

They tried to silence the voices and the stories of the women of the 17, but we have shown our film in community screenings together with the protagonist, Teodora Vásquez, and her organization, Mujeres Libres, across the country. So we are trying to show our film in many, many ways. But, as we see, the evangelical anti-choice groups have so much power. They are trying to silence us and trying to silence the stories of the women.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Talk more, Celina, about the origins of this law. You mentioned, in 1998, this new abortion law. How did it begin? And where do you see it going now?

CELINA ESCHER: Well, abortion was legal in three cases before 1998. Then it was a total ban of abortion in all cases. It was not possible to have an abortion even if your life is in danger, in cases of rape or the fetus will not survive outside the womb. So, in no cases was legal. And feminist organizations have been trying to legalize abortion since more than 30 years, but it has been really difficult and almost impossible to legalize abortion in El Salvador.

Now a feminist organization have brought the case of Beatriz in front of the Inter-American Court, and we are hoping that with this case will open up for the cases of the other women, and it will force El Salvador to change the abortion law. Last year, also the case of Manuela was held in front of the Inter-American Court, and the Inter-American Court ruled in favor of Manuela, saying that El Salvador is guilty for all human rights violations committed against Manuela. But the government has done nothing, and they don’t want the — Bukele doesn’t want to change the abortion law. He already said that he will keep the life that begins — the life begins at conception. So, he only wants to be reelected, but he doesn’t want to change the abortion law. So we will try with this case to open up and to make more pressure to the Salvadoran government.

AMY GOODMAN: Celina, tell us about these cases that are before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, the case of Manuela, that you just mentioned, and Beatriz.

CELINA ESCHER: Well, Manuela was a woman who lived in the countryside. She could not read and write. And she was pregnant. She had cancer, and then she had a miscarriage because of the cancer. Then she was criminalized in the hospital. She was sentenced to 30 years of prison, and she died in prison, leaving two sons behind.

And what we want is justice for Manuela and justice also for Beatriz. They are both women who lived in a situation of poverty. They needed to have an abortion. For example, the other example, the case of Beatriz, she had lupus, and she was pregnant, but the fetus had no brain, so it didn’t have any chance of survival outside the womb. So she asked the courts to have an abortion, but they denied her, and so the state forced [Beatriz] to keep the pregnancy. And it was torture for her for seven months. It was really torture for her. And then she gave birth with a C-section, and then the fetus died after many — like after three hours. And then she died years later because of the health issues she had.

So, the state is forcing women to keep pregnancy, also forcing young girls who have been raped to keep their pregnancy. This means torture for the women and girls. So, this is these two cases —

AMY GOODMAN: Celina?

CELINA ESCHER: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: We just have a minute, but I wanted to ask you to put El Salvador in the context of Central America and Latin America overall, where you have, what, Argentina and Colombia legalizing abortion. What’s happening in Central America overall?

CELINA ESCHER: Well, after in Colombia and Argentina abortion was legalized, in El Salvador — well, in Central America happened a major setback, because more and more conservative, right-wing, evangelical politicians who are in power are causing a major setback in reproductive rights. For example, in Honduras, it is not even legal to decriminalize abortion, not even to talk about it in the parliament. In Guatemala, they made a law, a family law, that also said that abortion is totally prohibited. In Nicaragua, abortion is also totally prohibited. And El Salvador is the country that has most extreme law, where women are —

AMY GOODMAN: And Mexico?

CELINA ESCHER: — unjustly criminalized for 30 and 40, 50 years of prison for aggravated homicide.

AMY GOODMAN: And Mexico? We have just 10 seconds.

CELINA ESCHER: And in Mexico — well, in Mexico now, it’s legal to have an abortion, and it’s anti-constitutional to criminalize abortion, though at least this, it’s happening, progressive.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we want to thank you so much for being with us. Celina Escher is a Salvadoran Swiss filmmaker and the director of the award-winning documentary Fly So Far, speaking to us from Stockholm, Sweden.

That does it for our show. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh. Have a productive, successful, happy International Women’s Day.

READ MORE  A Cal Fire firefighter watches over a structure as the Kincade Fire threatens along Chalk Hill Road in Healdsburg, California, Sunday, Oct. 27, 2019. (photo: Anda Chu/Bay Area News Group)

A Cal Fire firefighter watches over a structure as the Kincade Fire threatens along Chalk Hill Road in Healdsburg, California, Sunday, Oct. 27, 2019. (photo: Anda Chu/Bay Area News Group)

That heating has left nearly one-fifth of conifer forests in the Sierra Nevada mountains mismatched to the current climate, including 8% that are “severely” mismatched. This mismatch makes the so-called “zombie forests” less, or even completely, unable to recover after wildfires, themselves supercharged by climate change while also releasing massive amounts of carbon into the atmosphere.

Those findings come as a study published in PNAS finds climate-supercharged fires are so destructive that forests across 2.2 million acres across the West may be unable to regrow after fires — a landmass that could more than triple by midcentury to 7 million acres.

Researchers say improved forest management, including low-intensity burns can help, so long as those actions are taken concurrently with action on climate change. “But the longer you wait, the bigger the warming effect gets,” study co-author Phil Higuera told Inside Climate News. “Importantly, the projections only go through 2050, and that seems a lot closer than it used to.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.