Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

This surely was true of Sir Walter Raleigh, a poet, soldier, Queen Elizabeth’s boyfriend, who sailed up the Orinoco in search of El Dorado and failed and came back to London to be accused of treason and thrown in prison and have his head chopped off, a warning to the rest of us: don’t rise too high too fast. But as he himself wrote:

“Even such is time, which takes in trust

Our youth, our joys, and all we have,

And pays us but with age and dust.”

One day you’re a handsome dashing poet and pal of monarchy and the next day you’re a city in North Carolina.

Barack Obama suffered from unrealistic expectations, the first African American president, he was expected to usher in a new golden era, and look what happened. Meanwhile, Michelle Obama, in the role of FAAFL, kept a low profile and when she emerged as an author, she dazzled millions.

I know writers my age who decades ago were praised by the New York Times for a book that was “dazzlingly erudite and lavishly layered, bold and riveting and exquisitely crafted” and they haven’t written anything since, whereas the warmest praise I ever got was “amusing but often poignant,” which leaves plenty of room for improvement. So I keep trying to rise above poignant amusement to something lavishly layered and thus my morning passes happily. Don’t hit your peak too soon, is my advice. Don’t be afraid to disappoint.

I begin every day with low expectations thanks to a showerhead in a former house, a nozzle calibrated so that a two-centimeter turn took you directly from Arctic waterfall to fiery lava. You had to stand under the showerhead to adjust the knob so you stepped into this shower like you’d step onto the gallows, not sure if you’d perish by ice or by fire. Thanks to the memory of this instrument of torture, I begin each day with the hope of showering without being scorched alive and leap out of the shower, slipping on wet tile and displacing a couple discs and entering a long painful journey from chiropractor to orthopedic surgeon to a mystic named Sister Melissa who uses crystals and whispers solipsisms.

This hope is fulfilled — we moved to an apartment with a shower with two knobs, one hot, one cold, and there’s no problem, and you can adjust the spray to Deep Massage, Scattered Showers, or Wistful Mist. The shower is pleasant and uneventful and from that I proceed to a day that gets better and better.

I believe in life getting better. I grew up in a Sanctified Brethren home with a plaque over the breakfast table that said, “Jesus Christ the invisible guest at every meal, the silent listener to every conversation.” Which I found frightening, the idea of divine surveillance — it certainly didn’t encourage jokes — it encouraged false piety, even though we know that God looks on the heart and can tell a fake. From there, I walked to school where bullies ruled over the playground. They’d tie my shoelaces together when I wasn’t looking. They’d throw water at my crotch so it looked like I wet my pants. These scenes are still vivid in my mind.

None of that happens anymore. There’s no repressive plaque over the table and nobody ties the shoelaces of a man my age. I live with a woman who can read instruction manuals and put things together and who doesn’t mind when I drape my arms around her and whisper endearments.I do standup but not with a dog. In school I was given the nickname “Foxfart”. Nobody has called me that since back in the Eisenhower administration. This is what I consider real progress.

READ MORE  Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. outside the Supreme Court building in 2021. (photo: Jabin Botsford/WP)

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. outside the Supreme Court building in 2021. (photo: Jabin Botsford/WP)

But Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. chose not to address those or any other controversies in his annual “Year-end Report on the Federal Judiciary,” issued Saturday. Instead, he focused on a high mark of the judiciary’s past — a federal district judge’s efforts to implement school desegregation at Little Rock’s Central High School after the Supreme Court’s landmark 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

“The law requires every judge to swear an oath to perform his or her work without fear or favor, but we must support judges by ensuring their safety,” Roberts wrote in his nine-page report. “A judicial system cannot and should not live in fear. The events of Little Rock teach about the importance of rule by law instead of by mob.”

Roberts thanked Congress for recently passing the Daniel Anderl Judicial Security and Privacy Act, named for the son of New Jersey District Judge Esther Salas. Anderl was murdered in 2020 when he answered the door to their home in what was meant to be an attack on the judge.

The legislation allows judges to shield on the internet certain personal information about themselves and their families, such as home addresses, some financial information and employment details of their spouses. It has an exception for media reporting, but some transparency groups have worried that broad interpretation of the law could inhibit watchdog efforts.

Roberts also commended “the U.S. Marshals, Court Security Officers, Federal Protective Service Officers, Supreme Court Police Officers, and their partners” for “working to ensure that judges can sit in courtrooms to serve the public throughout the coming year and beyond.”

That’s about as close as Roberts came in his 18th report to commenting on the present day. The chief justice and other conservative members of the court have seen protesters outside their homes since the May leak of a draft opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, in which a majority of the court overturned Roe v. Wade’s federal guarantee of abortion rights.

A California man is facing attempted assassination charges after being arrested outside the suburban Maryland home of Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh with weapons and a plan to break into the justice’s house.

Roberts announced an investigation of the leak of the draft Dobbs opinion in the spring, just days after it was published in Politico, calling it a “singular and egregious breach of … trust that is an affront to the court and the community of public servants who work here.”

He directed Supreme Court Marshal Gail A. Curley to investigate the leak, saying that “to the extent this betrayal of the confidences of the Court was intended to undermine the integrity of our operations, it will not succeed.”

But Roberts has not publicly mentioned the investigation since then. Last summer, Justice Neil M. Gorsuch said the justices were expecting reports from Roberts about the work, but nothing has been exposed beyond leaked accounts of disagreements among justices and their clerks about attempts to examine cellphone records.

It is only one controversy to engulf the court. Several media outlets reported on what a former antiabortion evangelical leader said were efforts to encourage conservative justices to be bold in decisions regarding the procedure. Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. denied a specific allegation from Rev. Rob Schenck to the New York Times that the justice or his wife disclosed to conservative donors the outcome of a pending 2014 case regarding contraceptives and religious rights.

Congressional leaders demanded the court investigate, but Roberts through a legal counsel said there was little to probe after both Alito and the person to whom he was alleged to have given the information denied it.

Congressional Democrats have also questioned whether efforts by Virginia “Ginni” Thomas encouraging state legislators and White House officials not to give up on efforts to reverse the 2020 presidential election results — reported by The Washington Post and others — should prompt her husband, Justice Clarence Thomas, to recuse himself from litigation related to that issue.

Those legislators have demanded the court create a more formal code of conduct to deal with such questions.

Three years ago, Justice Elena Kagan told a congressional committee that the justices were “very seriously” looking at the question of whether to have a Code of Judicial Conduct that’s applicable only to the U.S. Supreme Court. But beyond Roberts saying such decisions should be made by the judicial branch alone, the chief justice has passed up the chance to be specific about plans.

Some thought the chief justice might return to such matters in his annual message, released by tradition on New Year’s Eve.

Instead, Roberts highlighted the courage of Judge Ronald N. Davies, brought in from North Dakota to preside over efforts to desegregate Little Rock’s Central High School over the objections of Arkansas Gov. Orval Faubus.

The bench from which Davies presided will be brought to the Supreme Court in 2023 as part of an exhibit about the court’s role in school desegregation and specifically the efforts of Thurgood Marshall, who argued Brown and later became the first Black Supreme Court justice.

“The authentic bench will give visitors an opportunity to transport themselves in place and time to the events in Little Rock of 65 years ago,” Roberts wrote. “The exhibit will introduce visitors to how the system of federal courts works, to the history of racial segregation and desegregation in our country, and to Thurgood Marshall’s towering contributions as an advocate before he became a Justice.”

READ MORE  The Pride flag is reflected in the glasses of a white nationalist who came to protest at the LGBTQ+ community's 'Pride in the Park' event in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho, on June 11, 2022. (photo: Jim Urquhart/NPR)

The Pride flag is reflected in the glasses of a white nationalist who came to protest at the LGBTQ+ community's 'Pride in the Park' event in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho, on June 11, 2022. (photo: Jim Urquhart/NPR)

The FBI recorded a drop in hate crimes in 2021, but the year's tally may not give a true account of hate crimes in the United States as thousands of law enforcement agencies were absent from the accounting.

The FBI annualized collection of data from law enforcement agencies saw 7,262 crimes motivated by race, religion, gender or other factors last year. That's a decrease from 8,263 incidents in 2020. But those numbers offer misleading conclusions as they are drawn from a pool of 3,255 fewer law enforcement agencies.

Only 11,883 agencies out of 18,812 city, state, municipal and tribal law enforcement agencies around the county sent data to the FBI, down from 15,138 in 2020.

The participation drop-off is due to a transition from a legacy crime reporting system that has existed in various forms since the 1920s to a more sophisticated reporting system that captures specific details of a crime. It allows the FBI and researchers to extract deeper analysis from crime statistics. For example, FBI data in 2021 showed that approximately 80% of homicides nationwide were committed with a firearm. That kind of data point wouldn't have been possible under the previous system.

But thousands of law enforcement agencies, including some of the biggest in the country like New York and Los Angeles, have lagged in the transition that began in 2016 to the new National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS).

Scores of police departments have found it difficult and costly to upgrade their legacy systems, despite the Justice Department aiding state and local agencies with more than $120 million in grants. The San Francisco Police Department told The Marshall project that it doesn't plan to send FBI data until 2025.

In 2021, for the first time, the FBI accepted data exclusively from the new NIBRS system, resulting in significant gaps that researchers say render the year's report meaningless.

In a news release, the Justice Department said "data cannot reliably be compared across years" as "several of the nation's largest law enforcement agencies, as well as some states, did not make the transition." As more law enforcement agencies transition to the new system, the department said, it would be able to "provide a richer and more complete picture of hate crimes nationwide."

But some researchers cast doubt on the FBI's ability to capture the true extent of hate crime in the United States even when more agencies are reporting their data, arguing that the issue runs deeper than the adoption of a new technology.

"People generally don't report crimes to the police. And for hate crimes, a lot of victims might not know they're a victim of a hate crime," says Jacob Kaplan, a researcher at Princeton's School of Public and International Affairs. "So even if 100% of agencies reported every hate crime they had and tried to really investigate everything, perceived hate crime, you're still going to be missing out on a potentially extremely large number of victims."

Researchers cite the gulf between the FBI's hate crime statistics compared to other data sets, such as the National Crime Victimization Survey reported by the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

"There's 200,000 to 300,000 hate crime incidents in a given year and the FBI data records less than 10,000 of them," says Eaven Holder, who authored a peer-reviewed study examining 18 years between the two data sets. "Estimates from the National Crime Victimization Survey suggests that 40 to 50% of all hate crimes go unreported to police."

In some cases, there is disagreement among law enforcement agencies about what constitutes a hate crime.

"New Jersey is a pretty good example where in recent years New Jersey has reported a lot more hate crimes than the FBI has agreed with," says Kaplan.

"Sometimes the FBI and the welfare agencies will disagree about why, the amount of bias, or disagree whether it was a hate crime," Kaplan says.

For example, in 2021 New Jersey reported 877 anti-Black bias incidents while the FBI counted 92. The FBI counted 25 incidents of anti-Jewish crimes in the same year, while New Jersey said there were 298.

New Jersey has reported a 400% increase in bias incidents since 2015, largely owing to the increase in harassment, a category the FBI does not include.

In some cases, gathering evidence to prove the motivating bias behind a crime may require more investigative resources than investigating the crime itself.

"For a hate crime to be reported, there needs to be evidence of bias that plays at least a small part in the crime," Kaplan notes. "And then the police need to have actual evidence, not just like, 'I think I was the victim of a hate crime.' They need some kind of evidence that suggests that bias was a motivating factor."

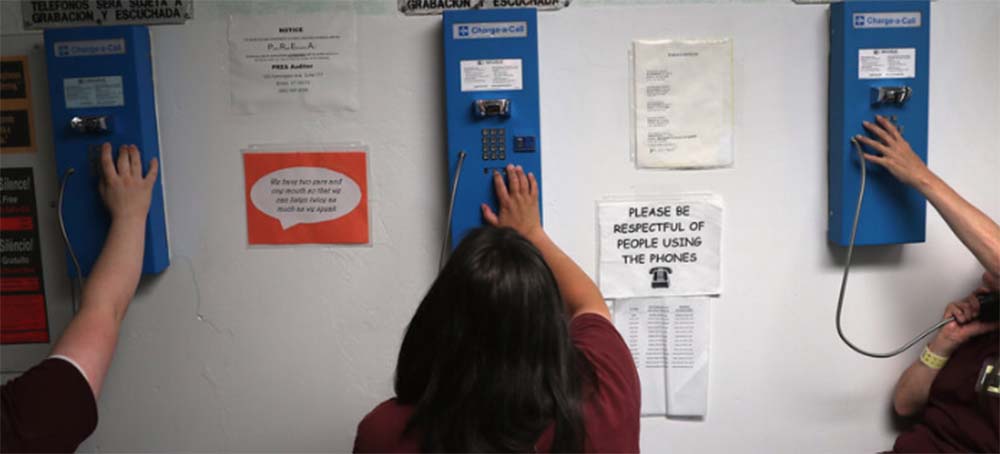

READ MORE  Prison inmates make one of their daily allotment of six phone calls at the York Community Reintegration Center. (photo: John Moore/Getty Images)

Prison inmates make one of their daily allotment of six phone calls at the York Community Reintegration Center. (photo: John Moore/Getty Images)

Legislation that aims to curb the costs of phone calls behind bars is heading to President Biden's desk for his signature.

The Martha Wright-Reed Just and Reasonable Communications Act of 2022, which was approved by Congress last month, is a major victory for the Federal Communications Commission in its yearslong fight to cap how much private companies charge incarcerated people for phone calls.

In a statement, FCC commissioner Geoffrey Starks called the newly passed legislation a "win for equity."

"Jails and prisons have charged predatory rates to incarcerated individuals for far too long," Starks said. "The FCC is poised to ensure that everyone has the ability to communicate."

Though rates differ by state, calls from prison cost on average $5 for a 30-minute phone call. Those fees can place a serious financial burden on incarcerated people and their loved ones looking to maintain regular contact, which research suggests can reduce recidivism. The bill itself is named after Martha Wright, a retired nurse who became a prison reform advocate after noticing the expensive cost to stay in touch with her grandson.

Two main factors contribute to expensive phone call fees

One reason for high rates is that jails and prisons typically develop an exclusive contract with one telecommunications company. That means incarcerated people and their families are stuck with one provider even if the company charges high rates.

Another factor is site commissions, or kickbacks that county sheriffs or state corrections departments receive. Some local officials argue that site commissions are crucial to fund staff who will monitor inmate phone calls for any threats to the community.

Prison reform advocates and federal regulators have scrutinized both contributing factors. Today, states such as New York, Ohio and Rhode Island have outlawed site commissions while California and Connecticut have made prison calls free of charge.

This bill may overhaul the prison phone call industry

The FCC has had the jurisdiction to regulate the cost of calls between states, but not within state borders, which FCC chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel has described as a "detrimental loophole."

Back in 2015, the FCC voted to cap costs on in-state prison phone calls. But two years later, a federal court struck down those regulations, arguing that the FCC had no such authority.

This legislation may finally change that, giving federal regulators the control to address in-state rates and ensure "just and reasonable" charges.

Rosenworcel told NPR's Weekend Edition that "just and reasonable" is not an abstract concept, but a legal term that the FCC has been using since the Communications Act of 1934.

"What it means is that those rates are fair and not discriminatory," she said in October. "No matter who you are or where you live in this country, whether you're incarcerated or not, you should be charged about the same to make some basic phone calls."

READ MORE  Inmates Jonathan Archille, left, and Brodarius Washington, work for no pay at the cafe in the state Capitol building in Baton Rouge on Nov 4, 2022. (photo: Emily Kask/WP)

Inmates Jonathan Archille, left, and Brodarius Washington, work for no pay at the cafe in the state Capitol building in Baton Rouge on Nov 4, 2022. (photo: Emily Kask/WP)

In recent years there has been a growing movement to prevent forced labor in prisons for little or no pay. But in a state that has one of the highest incarceration rates in the country, the debate is unsettled.

“They force us to work,” said Jonathan Archille, 29, who is among more than a dozen current and formerly incarcerated people in Louisiana who told The Washington Post they have felt like enslaved people in the state’s prison system.

Archille said prison staff had even used that term against him. “You’re a slave — that’s what they tell us,” he said. A spokesman for the Louisiana Department of Public Safety & Corrections, Ken Pastorick, said it “does not tolerate” such language and is looking into the allegation.

In the 2022 midterm elections, voters in four states approved changes to their constitutions to remove language enabling involuntary servitude as a punishment for crime — part of a larger push for change that many say is long overdue. But in Louisiana, a ballot measure that was conceived with the same goal in mind was rejected by a nearly 22-point margin.

Some observers and proponents of the Louisiana amendment attributed the result to the convoluted wording of the ballot question, which was changed to appease Republican lawmakers. Others said the measure wouldn’t have passed in its original form because the state was not ready to upend labor practices in its prisons.

“The drafting of our language didn’t turn out the way we wanted it to,” said state Rep. Edmond Jordan, a Democrat who sponsored the bill to change Louisiana’s constitution before later urging people to vote against the ballot measure that would have ratified it.

The amendments that passed in other states aren’t expected to lead to immediate, dramatic changes, which would require further legislation or legal challenges, and it’s unclear what would have happened had the more muddled Louisiana measure won approval. But the result is an unsettled debate in a state that has one of the highest incarceration rates in the country — and one that encapsulates broader themes such as race, criminal justice and the history of a country where slavery was once legal, all of which are at the center of the endeavor to revise other laws and regulations across the country.

Advocates are pushing for more state constitutional changes in upcoming elections, saying they are fighting for greater protections in a system that disproportionately affects Black and Brown people and forces many people to work for little or no pay. There are campaigns in about a dozen states, including Florida, New York and Ohio, for similar ballot measures in 2024. And the question could return in Louisiana in 2023.

As many as 800,000 incarcerated people work in prisons across the country, providing more than $9 billion a year in services to those facilities and creating around $2 billion in goods and commodities, according to a study from the University of Chicago’s Law School and the American Civil Liberties Union. The average prison wage is 52 cents an hour, while seven states are not required to pay prisoners for work. Many spend half their earnings on taxes and accommodation, the research shows.

“Louisiana law mandates that state inmates, necessarily serving a felony conviction, are required by law to work while incarcerated,” said a statement from the corrections department provided by Pastorick after the ballot measure was voted down. “Each inmate who is capable of working, is assigned a job duty, which may include working for the prison, or for Prison Enterprises.”

Prison Enterprises is a for-profit arm of Louisiana’s corrections department, which sells items made by prisoners, including office furniture, mattresses and offender uniforms.

“State law also provides that inmates ‘may’ be compensated, and state law also sets the range of an inmate’s earnings according to the skill, industry, and nature of the work performed by the inmate and shall be no more than a dollar an hour,” added the statement provided by Pastorick.

‘They should at least pay us’

A glimpse of Louisiana’s system came into focus last November at the Capitol building in Baton Rouge. Inmates arrived early each morning from Dixon Correctional Institute dressed in khaki shirts and green trousers; prison uniforms that have numbers sewn onto the breast. Some grabbed mops for janitorial work, others started hauling furniture. A few, including Archille, headed to the Louisiana House Dining Hall.

Archille was sent to prison when he was 17 after being found guilty of attempted murder for shooting two people from a car, according to court records. He has spent three of his 13 years in prison working at the Capitol on the “Trusty” program, which gives incarcerated people who show good behavior the chance to work outside prison grounds. As a trusty, Archille doesn’t earn or touch money; customers are forbidden from giving him tips.

“How you doing ma’am, how can we help?” he said to one as he served meatloaf and collard greens. Archille said few visitors to Louisiana’s Capitol ask him questions about his prison uniform. He said he serves them with a polite smile and tells them to have a good day.

Archille’s colleague and fellow inmate Brodarius Washington, 26, also part of the Trusty program, said working in the cafe at the Capitol is “good because we’re dealing with people. But we don’t get paid and they work us a lot.” They described being forced to work and not having a choice in their job.

As they talked to a reporter, Washington and Archille looked over their shoulders at the cafe’s manager, expressing fear of repercussions. “They should at least pay us and not try to punish us for talking to people like yourself,” Archille said. “But I’m really not afraid.”

Pastorick said it is against state law to abuse an inmate and that the department does not retaliate. He said “there are appropriate channels for requesting inmate interviews.” He previously declined a request from The Post to visit Louisiana State Penitentiary and interview people there.

In response to Archille’s allegation of being called a slave, Pastorick said, “This is the first time we have been made aware of this allegation as the inmate did not alert our staff to the alleged incident.” He added that Archille did not provide information to further the prison’s investigation of the allegation. Archille said he had given the guard’s name earlier but that no action was taken.

A week after The Post sought comment on the matter, Archille’s mother said she hadn’t heard from her son for a couple of days. Upon inquiring further with prison personnel, she said she had been told her son was on “lockdown” in the prison while under investigation for speaking to a journalist, which included isolation and loss of certain privileges.

“I usually speak to him every day,” Archille’s mother said through tears. Like others, she spoke on the condition of anonymity because she feared for her safety. “They said they didn’t want him talking to you guys and that’s why he’s on lockdown.”

When asked for comment, Pastorick said over the phone, “If somebody violates a policy then there are consequences for violating that policy. Disciplinary actions happen. I don’t know what you’re talking about, I haven’t been in contact with the prison. This is the first I’ve heard of any such thing.” He did not respond to follow-up emails and phone calls seeking more clarity on the inmate’s status or specific rule violations.

In Louisiana, there were more than 27,000 people imprisoned at the end of October 2022, according to the state’s corrections department. A 2022 report into captive labor from the University of Chicago and the ACLU found incarcerated people in Louisiana’s prisons earn 2 cents to 40 cents an hour. Costs inside the prisons can be high by comparison, with a visit to the prison doctor costing $3, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. Pastorick said routine sick checkups cost inmates a $1 co-pay, while emergency visits cost $2. Fees are waived if they have less than $250 in their account, Pastorick said.

At Louisiana State Penitentiary, known colloquially as Angola, incarcerated people clean the prison, cook for fellow inmates, farm vegetables for the corrections department, help sick people as orderlies in the prison hospital, and care for hospice patients.

“Most of the [prison] facilities are operating with less than half of what their own experts have found is the minimum necessary to safely operate the facilities,” said Lisa Borden, a civil and human rights lawyer at SPLC.

Situated on 18,000 acres of land — greater than the size of Manhattan — the prison started as a plantation and derives its nickname from the country in Africa once associated with the slave trade. Today, around 74 percent of the more than 5,000 inmates at Angola are Black, according to the University of Chicago and ACLU research. Advocates for change say a line can be drawn from Angola’s foundation as a plantation to the fields where incarcerated people work today.

“I was a 16-year-old kid who went straight from the classroom to the cotton field,” said Terrance Winn, 49, who gave testimony to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination for its 2022 U.S. review about his time at Angola from 1982 to 2020. Describing guards on horseback who oversee the field, he added, “You actually experience and feel what slavery was like for our ancestors.”

Those who refuse to work at Angola can be sent to segregated housing, beaten, and denied visits with family, according to the University of Chicago and ACLU report. In the summer months, temperatures can exceed 115 degrees — but work continues, people formerly incarcerated at the prison said.

Pastorick said these claims about prison conditions were “unfounded” and the use of segregated housing is determined by a department rule book for offenders.

‘We didn’t understand what we were voting for’

In recent years, there has been a growing movement to change state constitutions to prevent forced labor — part of a wider push to “End the Exception” in the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which states: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States.”

When Jordan proposed an amendment to Louisiana’s constitution in 2021, it was voted down in a committee due to Republican resistance. State Rep. Alan Seabaugh (R) described it as “dangerous,” and his colleagues voted to reject it.

Given that some felony convictions in the state come with sentences including imprisonment “at hard labor,” Seabaugh explained, people must work while incarcerated. “If you’re going to say a sentence with hard labor is tantamount to indentured servitude, and you outlaw indentured servitude, then you have potentially just invalidated” them, Seabaugh said.

In 2022, Jordan brought back the bill to amend the state constitution, which reads, “Slavery and involuntary servitude are prohibited, except in the latter case as punishment for crime.” Jordan wanted to strike the words “except in the latter case as punishment for crime.”

But state Rep. Richard Nelson (R) suggested an addition — clarifying that the law “does not apply to the otherwise lawful administration of criminal justice,” which he said would make it more palatable to his fellow Republican colleagues.

“We changed it to be like Utah, which everybody agreed to,” Nelson said. Voters in Utah approved a change to their state constitution in 2020 that removed the slavery exception but contained this provision to protect prison labor. Nelson added his amendment would still allow for work release programs, while removing the exception to slavery.

Jordan and Seabaugh both accepted Nelson’s amendment, which was cleared to go to a public vote. A nonpartisan member of staff in the state House drafted language for the ballot measure in the same meeting, which read: “Do you support an amendment to prohibit the use of involuntary servitude except as it applies to the otherwise lawful administration of criminal justice?” The use of the word “except” created complications.

After lawyers warned the measure could in fact be interpreted by courts to extend labor in prisons, Jordan reversed himself, telling people to vote “No.” Others followed Jordan’s lead and told people to strike down the measure, including the Louisiana Legislative Black Caucus.

But Decarcerate Louisiana, an organization of formerly incarcerated people who proposed the constitutional amendment to Jordan, urged people to vote “Yes,” saying the bill would have improved the situation for people in prison.

“The ballot question was too confusing,” said Curtis Ray Davis II, the founder of Decarcerate Louisiana. “We didn’t understand what we were voting for.”

Jordan said the wording of the ballot measure, which passed without question, was a “mistake.” He said he did not believe the drafting was “an intentional effort to derail it.”

Robert Singletary of the Louisiana House Legal Division said nonpartisan staff drafted the ballot language, but he declined to comment further.

Fox Richardson, who was imprisoned alongside her husband Rob and has co-written a forthcoming book with him about their 21 years separated by prison, said she believed the amendment would reaffirm the exception and allow forced labor in prisons to continue. “I voted no,” she said.

Ronald Marshall and Bruce Reilly at VOTE, an advocacy organization for current and formerly incarcerated people, reflected the conflicting sides, with the former voting against it and the latter voting for it.

“It should have read ‘slavery and involuntary servitude is prohibited’ and left it like that,” said Marshall, who served 25 years at Angola and described a brutal time inside with heat exhaustion and workers sustaining debilitating injuries.

The language on the ballot measures in Alabama, Oregon, Tennessee and Vermont was more straightforward, with Alabama voting as part of a larger package to remove racist language from the state constitution and Vermont choosing “Yes” or “No” on prohibiting slavery and involuntary servitude.

Some advocates of change said even these outcomes do not go as far as they would like. “The [Alabama] measure prevents the state from forcing individuals into that type of work,” said Jerome Dees, policy director for the SPLC who specializes in Alabama. “What it does not do is prevent them from hiring out those individuals and unjustly compensating them.”

But others said the constitutional changes could open a path for lawsuits from incarcerated people who claim their constitutional rights have been violated. In Colorado, which was the first state to change its constitution in this way in 2018, two incarcerated people have brought a class-action lawsuit against Gov. Jared Polis (D). Colorado also passed a law that will give incarcerated people in the final year of their sentences a minimum wage of $12.56 per hour when working for private companies.

Amendments similar to the ones that appeared on ballots this year could appear in eight states next year, according to Davis. “Human beings should not be property of other people or entities,” he said.

In Louisiana, Davis said he hopes Jordan will bring the bill back to the legislature next year with improved language. If he does, Seabaugh said he will oppose it.

“We put too many constitutional amendments to the people of Louisiana,” Seabaugh said.

READ MORE  A clothing manufacturing company in Mexico. (photo: Bryan Denton/NYT)

A clothing manufacturing company in Mexico. (photo: Bryan Denton/NYT)

The unfolding trend known as “near-shoring” has drawn the attention of no less than Walmart, the global retail empire with headquarters in Arkansas.

Early last year, when Walmart needed $1 million of company uniforms — more than 50,000 in one order — it bought them not from its usual suppliers in China but from Preslow, a family-run apparel business in Mexico.

It was February 2022, and the contours of global trade seemed up for alteration. The worst pandemic in a century had upended shipping. The cost of transporting products across the Pacific had skyrocketed, and ports were choked with floating traffic jams — a stark indication of the dangers of depending on a single faraway country for critical goods.

Among multinational companies, decades of faith in the economic merits of making things in China had come under withering challenge, especially as animosity intensified between Washington and Beijing.

At his office in Mexico City, Isaac Presburger, director of sales at Preslow, took Walmart’s order as a sign of his country’s evolving role in the economy, and the opportunities that flow from sharing the same side of the Pacific with the United States.

“Walmart had a big problem with their supply,” Mr. Presburger recounted. “They said, ‘OK, Mexico, save me.’”

Basic geography is a driver for American companies moving business to Mexico. Shipping a container full of goods to the United States from China generally requires a month — a time frame that doubled and tripled during the worst disruptions of the pandemic. Yet factories in Mexico and retailers in the United States can be bridged within two weeks.

“Everybody who sources from China understands that there’s no way to get around that Pacific Ocean — there’s no technology for that,” said Raine Mahdi, founder of Zipfox, a San Diego-based company that links factories in Mexico with American companies seeking alternatives to Asia. “There’s always this push from customers: ‘Can you get it here faster?’”

During the first 10 months of last year, Mexico exported $382 billion of goods to the United States, an increase of more than 20 percent over the same period in 2021, according to U.S. census data. Since 2019, American imports of Mexican goods have swelled by more than one-fourth.

In 2021, American investors put more money into Mexico — buying companies and financing projects — than into China, according to an analysis by the McKinsey Global Institute.

China will almost certainly remain a central component of manufacturing for years to come, say trade experts. But the shift toward Mexico represents a marginal reapportionment of the world’s manufacturing capacity amid recognition of volatile hazards — from geopolitical realignments to the intensifying challenges of climate change.

“It’s not about deglobalization,” said Michael Burns, managing partner at Murray Hill Group, an investment firm focused on the supply chain. “It’s the next stage of globalization that is focused on regional networks.”

That Mexico looms as a potential means of cushioning Americans from the pitfalls of globalization amounts to a development rich in historical irony.

Three decades ago, Ross Perot, the business magnate then running for president, warned of “a giant sucking sound going south” in depicting Mexico as a job-capturing threat to American livelihoods.

“The reality is that Mexico is the solution to some of our challenges,” said Shannon K. O’Neil, a Latin America specialist at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York. “Trade that is closer by from Canada or Mexico is much more likely to create and protect U.S. jobs.”

Given that the United States, Mexico and Canada operate within an expansive trade zone, their supply chains are often intertwined. Each contributes parts and raw materials used in finished goods by the others. Cars assembled in Mexico, for example, draw heavily on parts produced at factories in the United States.

Overall, some 40 percent of the value of Mexico’s exports to the United States consists of parts and components made at American plants, according to a seminal research paper. Yet only 4 percent of imports from China are American-made.

A Walmart spokesperson described the company’s interest in Mexico as part of a broader effort to make its supply chain less vulnerable to troubles in any one region.

For now, Mexico lacks the capacity to assume China’s place as the dominant supplier of a vast range of goods.

At Preslow’s factory some 50 miles north of Mexico City, 200 seamstresses leaned over clattering sewing machines on a recent morning, stitching garments amid the strains of Mexican folk music. Local designers sat in front of computer screens, conjuring new creations.

Yet the storage shelves were piled high with bolts of synthetic fabric, nearly all of it made in China.

“All the basic materials are still imported from China, because you don’t have the suppliers here,” Mr. Presburger said. “The fabrics I use are impossible to get in Mexico.”

Closer to Home

On the other side of the Mexican border, in a bedroom community north of Dallas, Jose and Veronica Justiniano were also dependent on vital goods from Asia and eager to find a vendor in the same hemisphere.

The couple ran a small business, Veronica’s Embroidery, out of their home. They supplied restaurants, construction companies and maid services with uniforms for their employees.

Born and raised in El Salvador, they had left behind a horrific civil war to forge comfortable lives in the United States.

Mr. Justiniano, 50, landed first in Los Angeles, where he worked as a janitor at the Beverly Hills jail, and then as a billboard installer. After moving to Dallas, he got an entry-level job at an auto parts plant, and eventually rose to supervisor, gaining expertise in machinery. Ms. Justiniano, 54, worked as a home aide to an aging couple.

In 2018, the couple bought their first embroidery machine, installing it in an upstairs bedroom. The next year, they secured their most important customer — Gloria’s Latin Cuisine, a chain of 22 fine-dining restaurants in Dallas, Houston, San Antonio and Austin.

The Justinianos bought uniforms from a company that imported them from Asia. Then they used their machines to embroider the logos.

Their distributor maintained huge stocks of inventory at warehouses in Texas, typically delivering within a day. But as the pandemic intensified in 2020, days turned into months. The Justinianos were late in their own deliveries, a mortifying threat to their business.

Mr. Justiniano hurriedly sought another supplier.

“The only way was Mexico,” he said.

They eventually entrusted much of their business to Lazzar Uniforms, a family-run company in Guadalajara, a booming city about 350 miles northwest of Mexico’s capital. Lazzar’s commercial director, Ramon Becerra, 39, was eager to gain a crack at the enormous market to the north.

“We know the U.S. is the future for us,” Mr. Becerrra said.

The Justinianos’ American distributor operated in bulk, selling only what it had in stock and providing no custom work. Lazzar, on the other hand, beckoned as a design shop and apparel factory in one.

Mr. Becerra’s team conferred on the particulars of what the Justinianos desired: a light fabric that vented away moisture, providing relief from the heat of the kitchen. The two companies were able to communicate easily by phone and video without having to navigate a time difference.

They started small, with a few dozen chef’s jackets. By September 2021, Veronica’s Embroidery was purchasing 1,000 linen shirts in a single order, at prices close to what its previous distributor charged for imports from Asia.

On a recent morning, Mr. Becerra hosted Mr. Justiniano at his factory in Guadalajara. The two men discussed a potential new partnership in which Lazzar would set up a warehouse in Texas, with Mr. Justiniano handling American distribution.

“This year has been a wake up call for the U.S.,” Mr. Justiniano said. “We have to reconsider where we get our stuff made.”

A Troubled Legacy

The biggest impediment to Mexico’s reaching its potential as an alternative to China may be Mexico itself.

Its president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, has neglected the nation’s infrastructure, including its ports.

Even Mr. Presburger, an enthusiastic promoter of his country’s industrial virtues, concedes that Mexico will struggle to amass the scope of China’s manufacturing capacity.

He recalled his first trip to China to look for fabric more than a decade ago. The scope of production left him astonished, with monumental spinning mills alongside specialized dying operations.

“The sheer size of the factories there is crazy,” he said. “I don’t think there’s a way back from that. It’s not going to be easy.”

Inside his factory, he displayed a popular item, a black bomber jacket adorned with an elaborate and colorful pattern. The zipper was made in Mexico, and so was a skull-shaped ornament that pulled it. But the rest of the components — the fabric, the thread, the liner — were all made across the Pacific.

Still, a shift is palpable.

Near Preslow’s plant, an enormous factory makes as many as six million buttons per day, employing some 1,500 people. The company, Botones Loren, has seen its sales grow by nearly two-thirds over the past year. Its customers — international brands like Armani and Men’s Warehouse — are shifting orders from China, said the company’s chief executive, Sony Chalouah.

“They think that the U.S. will continue to be fighting with China,” he said. “They want to not depend on China.”

The Geopolitical Realignment

Some within the apparel industry anticipate that Mexico’s appeal will fade as normalcy returns to the global supply chain.

Shipping prices have sharply declined over the past year. China has begun loosening Covid restrictions. Chinese apparel makers are aggressively courting business by offering steep discounts, according to Bernardo Samper, a longtime New York sourcing agent.

“At the end of the day, everything is driven by pricing,” he said.

Yet within Mexico, businesses are counting on continuing acrimony between the United States and China.

The Trump administration imposed steep tariffs on hundreds of billions of dollars of Chinese imports. President Biden has continued that policy, while adding measures that seek to deny China access to technology.

Washington has accused the Chinese government of genocide in its brutal repression of the minority Uyghur community in the western Xinjiang region — a major source of cotton. Any company buying clothing made in China risks accusations of exploiting Uyghur forced labor.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its deepening ties with China have amplified the sense that the world is dividing into distinct camps of allies and enemies.

Companies need reliable supply chains.

Lectra, a French company that makes machines that cut fabric into pieces for the apparel industry, has seen its sales in Mexico and Central America grow by nearly a third over the past year.

“What is driving this near-shoring is basically the situation between the U.S. and China,” said the company’s commercial director for the region, Carlos Sarmiento.

“It’s not that China is going to disappear from the American market,” he added. “It’s that there is more openness to look at Mexico and Central America as an alternative rather than depend entirely on China.”

READ MORE  Boys at Barrick Gold’s North Mara gold mine waste dump. (photo: Catherine Coumans/Mining Watch Canada/Mongabay)

Boys at Barrick Gold’s North Mara gold mine waste dump. (photo: Catherine Coumans/Mining Watch Canada/Mongabay)

Nigeria’s new oil frontier puts communities at risk, campaigners warn

The Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC) first announced the discovery of crude oil, gas and condensate in commercial quantity in Kolmani in 2019. President Muhammadu Buhari said the field has 1 billion barrels of oil reserves and 500 billion cubic feet of gas.

The governor of Gombe state has however pledged to avoid the “mistakes of the Niger Delta,” where decades of oil and gas exploration by multinationals have severely damaged the environment and destroyed livelihoods. Governor Inuwa Yahaya has promised both a role for local businesses in the value chain and transparency that will protect communities and the environment.

“With regard to the issue of the environment, our [state] ministry of environment is working hand in hand with the Federal Ministry of Environment and the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation Limited so that we will avoid all the mistakes and pitfalls that have been the big challenge of oil exploration and implementation in the southern part of the country,” he said.

But the federal government, which has final responsibility for mineral extraction, has not published an environmental impact assessment of the Kolmani project as required by law.

Chima Williams, executive director at Environmental Rights Action/Friends of the Earth Nigeria, said the organization was investigating issues surrounding the new project and would be demanding full disclosure of impact assessment from the government.

“If there is no impact assessment, how do you understand the likely problems, and the mitigation measures to tackle them?” he said.

Environmentalist Nnimmo Bassey of the Health of Mother Earth Foundation rejected the suggestion that the NNPC can extract oil without damaging the environment.

“It is erroneous to suggest that the ‘mistakes’ of the Niger Delta can be avoided. That will be wishful thinking,” he said. “The promises are always the same and the shocks of disappointment will be the same. We have seen this across Africa and those celebrating the find are playing fossil politics.”

Barrick Gold faces lawsuit over deadly police violence at Tanzanian mine

A plaintiff in a lawsuit launched in November by Tanzanian mining-affected communities against Canada’s Barrick Gold Corporation has spoken out against the killing of her son, allegedly by mine-funded police.

On Dec. 1, Rights and Accountability in Development (RAID), a U.K.-based charity that holds global businesses to account for human rights abuses, released a video in which a resident of one of the villages near Barrick’s North Mara mine describes looking for her son following a night of violent police activity near the mine.

“In the morning we were calling his phone but it was just ringing, so we started asking neighbors where my son was because we had heard bombs and shots that night,” says a woman identified only as Mariam to protect her from possible retaliation. “We were told there was some shooting — we went to the area and saw a lot of blood.”

She says she later found her son’s body at the morgue. “The mine has brought a lot of harmful practices. Police shoot and kill people or permanently injure them.”

RAID director Anneke Van Woudenberg says Barrick has signed an agreement with the Tanzania police to pay, equip, feed and house approximately 150 police officers who operate around the North Mara mine.

Barrick Gold’s chief executive officer, Mark Bristow, has previously denied any involvement by the company in the police abuses. “North Mara Gold Mine Limited does not supervise, direct or control any mission, assignment or function of the Tanzanian Police Force. The Tanzanian Police Force operates under its own chain of command and makes its own decisions on strategy,” he wrote in a February 2022 letter to RAID.

Mariam and 21 other members of the Indigenous Kurya community in the area around the mine have filed a claim for compensation for five deaths since Barrick Gold took control of the North Mara mine in September 2019, as well as alleged incidents of torture at the hands of police.

Funds for community development disappear in DRC’s Lualaba

Local media in the Democratic Republic of Congo are reporting that the chief accountant of an area near the southeastern town of Kolwezi has vanished along with $14.5 million in mining royalties.

According to reports, the official regularly withdrew substantial amounts of money from an account holding royalties that are paid to the state by mining companies. The funds are intended to finance projects supporting communities affected by the mining industry in this part of Lualaba province.

The misappropriation was exposed by a local civil society organisation, Luwanzo lwa Mikuba, which also noted that the head of the Kolwezi sector didn’t denounce the disappearance of his colleague, whom he himself had sent to the bank to withdraw money.

At the same time, the General Inspectorate of Finance discovered other embezzlements totaling more than $400 million across Lualaba province between 2018 and 2021, according to other sources.

“The spirit of the mining code is that these funds should be allocated to community development,” says Donat Mpiana, a human rights activist with the NGO ACIDH (whose acronym in French translates into “Action against Impunity and for Human Rights”). “But it is sad to see that this has not happened. Instead, these funds are used for other things.”

Mining royalties, according to Congolese mining law, are supposed to fund quick-impact projects that benefit the population. This includes the construction of roads, hospitals, schools and water infrastructure. These social goods are lacking in many rural areas.

In 2014-2015, an acidic water retention pond at Mutanda Mining, 40 kilometers (25 miles) southeast of Kolwezi, spilled into the Kando River. In 2017, according to the NGO Afrewatch, acid leaks from the same mining company contaminated residents’ fields in Lualaba-Centre and Kindu.

At the end of November, President Félix Tshisekedi appointed new leaders for local governments at the sector and commune levels. Because of suspicions of misappropriation, the Inspectorate General of Finance has asked that remittances and recoveries be delayed to allow an audit of public accounts.

This article was originally published on Mongabay.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.