Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn at a campaign event in Brunswick, Ohio on April 21, 2022. (photo: Dustin Franz/Getty Images)

Former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn at a campaign event in Brunswick, Ohio on April 21, 2022. (photo: Dustin Franz/Getty Images)

In military intelligence, he was renowned for his skill connecting the dots and finding terrorists. But somewhere along the way, his dot detector began spinning out of control.

“General Flynn, do you believe the violence on January 6 was justified?” Representative Liz Cheney asked him in a video teleconference deposition for the January 6 committee.

Flynn’s lawyer pressed the mute button and switched off the camera. Ninety-six seconds passed. Flynn and the lawyer reappeared with a request for clarification. Did Cheney mean morally justified, or legally? Cheney obligingly asked each question in turn.

“Do you believe the violence on January 6 was justified morally?” she asked.

Flynn squinted, truculent.

“Take the Fifth,” he said.

“Do you believe the violence on January 6 was justified legally?” Cheney asked.

“Fifth,” he replied.

Cheney moved on to the ultimate question.

“General Flynn, do you believe in the peaceful transition of power in the United States of America?” she asked.

“The Fifth,” he repeated.

It was a surreal moment: Here was a retired three-star general and former national security adviser refusing to opine on the foundational requirement of a constitutional democracy. Flynn had sworn an oath to protect and defend the Constitution against all enemies, foreign and domestic. Rule of law had been drilled into him for decades in the Army.

Now, by invoking the right against self-incrimination, he was asserting that his beliefs about lawful succession could expose him to criminal charges. That could not be literally true—beliefs have absolute protection under the First Amendment—but his lawyer might well have worried about where Cheney’s line of questioning would lead.

Flynn had said publicly that President Donald Trump could declare martial law and “re-run” the presidential election he had lost. He and Sidney Powell, one of Trump’s lawyers, had turned up in the Oval Office on December 18, 2020, with a draft executive order instructing the Defense Department to seize the voting machines that recorded Trump’s defeat. Flynn and Roger Stone, the self-described political dirty trickster, were the two men Trump made a point of asking his chief of staff to call on January 5, on the eve of insurrection, according to Cassidy Hutchinson’s recent testimony before the January 6 committee.

All of which raises a question: What happened to Michael Flynn?

He has baffled old comrades with his transformation since being fired as director of the Defense Intelligence Agency in 2014. He led chants to lock up Hillary Clinton in 2016. In 2020, he posted a video of himself taking an oath associated with QAnon. He has endorsed crackpot fabrications of the extreme right: that Italy used military satellites to switch votes from Trump to Biden in 2020, that COVID-19 was a hoax perpetrated by a malevolent global elite, that the vaccine infused recipients with microchips designed for mind control.

Has Flynn always been susceptible to paranoid conspiracies? Or did something happen along the way that fundamentally shifted his relationship to reality? In recent conversations I had with the former general’s close associates, some for attribution and some not, they offered a variety of theories.

I had started trying to answer these questions about Flynn well before the country saw him plead the Fifth. The best way to investigate, I initially thought, would be to spend time with the man himself.

I’d had lunch with Flynn some years ago at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York. He was a one-star general working for then–Lieutenant General Stanley McChrystal, his most important mentor in the Army. He fit in comfortably at the Council, a pinstriped bastion of the foreign-policy establishment, which these days is a bugaboo of his dark suspicions about global elites. We spoke of then–Vice President Dick Cheney, the subject of a biography I had recently written, and he later sent word that he had enjoyed listening to the audiobook while running. His affect was thoughtful, buttoned-down, and appropriate to the setting.

I recalled that lunch to Flynn’s brother Joe, who serves as his gatekeeper with the press, when I asked for an interview for this story. (Another brother, Charles, is the commanding general of the U.S. Army in the Pacific.) Joe Flynn said those were very different times. “His attitude about speaking to the mainstream media—or I’d say I would put The Atlantic into the left-wing media—is very negative because it always blows up in your face,” he said. “They always report things that [he] didn’t say or they’re calling names that he doesn’t, you know, that don’t have anything to do with him.”

“That’s kind of the whole point of talking to a guy, to understand him in his own words,” I said.

Joe Flynn didn’t bite.

“Write what you want to write. But we don’t necessarily want to add fuel to the fire by talking to people and then they twist your words. There has not been a time yet that it hasn’t backfired,” he said. Every story turns out to say, “‘Ah, Flynn’s a nut, Flynn’s a conspiracy theorist, Flynn’s an insurrectionist,’ all the other bullshit they say.”

This week, I tried again to seek comment from Flynn, via his brother. “There is no chance General Flynn will speak to the Atlantic,” Joe Flynn wrote. “Have a great day.”

When Flynn moves through public spaces these days, three muscular men with earpieces enclose him in a wedge. One of them moved to intercept me when I approached with a question at an event, taking my elbow and turning me away. “Don’t,” he said, succinctly.

The next-best strategy, I figured, was to watch Flynn in his element, surrounded by supporters. I went to hear him speak at the Trinity Gospel Temple in Canton, Ohio, where he served as mascot and majordomo of a traveling road show called “ReAwaken America.” It was a proudly mask-free event; anyone with a covered face was asked to leave. There would be six dozen speakers over two days, including MAGA stars such as Eric Trump, Mike Lindell, and Roger Stone. But Flynn was the big draw.

Nearly every other speaker paid Flynn homage. One of them won a standing ovation by invoking a MAGA trinity: “Jesus is my God. Trump is my president. And Mike Flynn is my general!”

Flynn stood in the wings, stage left, just visible to an adoring audience of 3,000. He wore cowboy boots, a gray worsted suit, and an open-collared shirt, arms crossed at his chest in a posture of benign command.

“Ladieeeees and gentlemen, stand on your feet and greet Generalllll … Miiiiiichael Flyyyyynnn!” Clay Clark, Flynn’s touring partner and emcee, yelled into the microphone in the style of a professional-wrestling announcer. The room erupted. “Fight like a Flynn!” screamed a man in the audience, quoting a slogan that Flynn’s niece was selling on T-shirts outside. “We love you!” screamed the woman next to me.

Nothing superficial explained the appeal. Flynn is not an orator. He does not premeditate applause lines, and he sometimes seems startled when the audience reacts. He rambles, scriptless, through fields of apparently disconnected thoughts. “He’s free-range,” Clark told me.

Some of the things he said fell into a category of assertion that his military-intelligence critics used to call “Flynn facts.” “Read some of The Federalist Papers,” Flynn told the crowd. “They’re simple; they’re amazing, amazing documents as to who we are.” He added, “Ben Franklin’s one of the ones that wrote some of this and argued some of it.” (No, he’s not.) Flynn attributed the nation’s founding to divine intervention, adding, “That’s why the word creator is even in our Constitution.” (It isn’t.)

What Flynn has is an everyman quality, according to Steve Bannon, who said he declined an invitation to join the tour. “Mike is authentic,” Bannon told me. “To them, he’s authentic. He’s a fighter. That’s big.” Flynn reminds Bannon, he said, of his Irish uncles and cousins: “He’s not pretentious. He’s one of them.”

If this was authenticity, though, it was authentically detached from reality. The animating ideas behind the “Great ReAwakening,” expounded by the various speakers, were (1) that forces loyal to Satan are stealing political power in rigged elections (2) on behalf of a global conspiracy masterminded by Klaus Schwab, the founder of the World Economic Forum, and Yuval Noah Harari, an Israeli public intellectual, and (3) that the cabal has fabricated the coronavirus pandemic as an excuse to mandate dangerous vaccines, which (4) make people sick and may secretly turn them into “transhumans” under the conspiracy’s remote control.

QAnon talking points pervade the “ReAwaken America” tour. In Canton, Clark got a rise from the crowd with a reference to “adrenochrome,” which QAnon myths describe as a drug that cannibalistic global elites harvest by torturing children.

Some of the “ReAwaken America” speakers fairly glowed with insincerity—Roger Stone grinned a Cheshire Cat grin after telling the crowd that he saw a “demonic portal” open over the White House when Joe Biden moved in.

But Flynn, by contrast, did not display any guile at all. By every outward indication, he was speaking in earnest.

The man had once had an outstanding career in military intelligence, a field that values discernment and reason, evidence and verification. Now he looked high on his own supply.

Did something in his history offer a clue?

Flynn grew up in Rhode Island, the sixth of nine children of an Army sergeant first class and a mother from a military family. He stood out early. He graduated from Middletown High School in 1977 as homecoming king, a co-captain of the state-champion football team, and the “best looking” senior by vote of his classmates. Thomas Heaney, the quarterback, told me that Flynn, at maybe 160 pounds, was scrawny for an offensive lineman but he had grit. He was “not the fastest guy on the field, but played hard.”

Already, Flynn had a flair for the heroic. As a teenager, he and a friend rescued a pair of toddlers from the path of a car rolling driverless down a hill. Flynn became known in the neighborhood as a “guardian of the little ones,” according to Kathleen Connell, a neighbor and a former Rhode Island secretary of state. But he also had a brush with the criminal-justice system, he writes in a 2016 book, which landed him in juvenile detention for a night and earned him a year of supervised probation. He does not elaborate.

Flynn was a B student at the University of Rhode Island but top of his class in the ROTC cohort. In 1983, not long after graduation, First Lieutenant Flynn deployed with the Army’s 82nd Airborne Division in the invasion of Grenada. There was not much combat to speak of, but Flynn demonstrated valor when two fellow soldiers were swept out on a riptide and struggled to stay afloat. Again, he was the hero, diving off a 40-foot cliff to rescue them both.

Flynn began to make his name as a colonel in 2004, when the Army deployed him to Iraq as J-2, or director of intelligence, of a Special Operations unit called Task Force 714. The task force, drawn from the most elite units in the Joint Special Operations Command and led by then–Major General Stanley McChrystal, had one mission in Iraq: to track and kill insurgents.

They had a slow start. In his memoir, My Share of the Task, McChrystal writes that he arrived in the command to discover “painstakingly selected, exquisitely trained warriors” who could not keep track of their targets. In those early days, the task force would stage a raid, kill or capture insurgents, and fill burlap sacks with “scooped-up piles of documents, CDs, computers, and cell phones.” Unable to make sense of that raw intelligence in the field, the commandos would ship it all back to headquarters in Baghdad, or even back to the United States, for analysis.

At McChrystal’s direction, Flynn rebuilt the system. The two men shaped the task force into an “extraordinary machine,” a senior flag officer who worked with them told me.

McChrystal described Flynn as “pure energy.” He speed-walked, speed-talked, and filled bulging green notebooks with diagrams and briefing notes. Flynn, McChrystal writes, “had an uncanny ability to take a two-hour discussion or a thicket of diagrams on a whiteboard and then marshal his people, resources, and energy to make it happen.”

Under Flynn’s leadership, and with forward-deployed intelligence analysts, the commandos found that they could capture an enemy safe house, exploit devices and papers on the spot, and use the fresh intelligence to launch another operation within an hour or two, before insurgents had even realized that they had been compromised.

Flynn and McChrystal became an exceedingly deadly team. At its peak, the task force was “doing 12 to 15 operations a night,” the flag officer said, month after month. “He was incredibly hardworking, and he could see how to connect the dots.” Another admirer of Flynn’s at the time, a retired four-star general, told me that there were no illusions about the nature of those missions. “You go in the house to kill everybody in there,” he said.

In his three years in Iraq, Flynn lived in a world of good and evil. He oversaw a relentless machine that killed thousands, including Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the prolifically murderous leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq.

Flynn won his promotion to brigadier general, then added a second star when he served briefly as J-2 for the Joint Chiefs of Staff in the Pentagon in 2008, a prestigious assignment. Then, in 2009, McChrystal was selected to command all U.S. and allied troops in Afghanistan. He brought Flynn with him.

General Barry McCaffrey, one of the most decorated generals in recent decades, made a fact-finding tour of McChrystal’s command in November 2009 and met with Flynn. He was dazzled. “He had a map, and he had this immense command of the terrorist forces in Afghanistan and the nature of the culture and what was going on in Pakistan,” McCaffrey told me. “I thought, God, this guy is flipping magic.”

People who worked with Flynn in Iraq and Afghanistan, most of whom declined to speak on the record out of respect for old friendships, said Flynn showed no sign in those years of extreme or fantastical views. One of his colleagues in Afghanistan was a young Marine captain named Matt Pottinger, who would go on to become deputy national security adviser under Trump. “When we were in Afghanistan,” Pottinger told me, “I didn’t hear wacky conspiracies.”

Still, with Pottinger’s help, Flynn cultivated a reputation as an iconoclast. He was best known in Afghanistan for a controversial white paper that he published in January 2010, a sharp critique of the U.S. government’s intelligence operations in Afghanistan by the man ostensibly in charge of them. Flynn was listed as the first and senior author, and it burnished his reputation as a defense intellectual, though in fact, Pottinger told me, he himself “wrote most of the paper,” and “Flynn provided guidance and edits.”

Flynn had taken a risk by publishing the paper outside the Pentagon chain of command, and then–Defense Secretary Robert Gates complained about the breach of protocol to James Clapper, then the undersecretary of defense for intelligence. “He didn’t object to the article as much as he did object to … the manner in which it came out,” Clapper told me. Clapper called to admonish Flynn, passing along the secretary’s displeasure. But on the whole, the episode raised Flynn’s profile and laid the ground for his next promotion.

Flynn spent his career in a fixed universe of black and white, right and wrong. His expertise was in connecting the dots and drawing inferences. But somewhere along the way, his dot detector began spinning out of control.

Flynn’s last job in uniform, as director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, became his first major failure. He had been “a superb officer” in staff positions, a senior colleague told me, but when it came time to run a large organization—with more than 15,000 employees, most of them civilians—Flynn struggled. Another colleague, a high-ranking officer, told me that Flynn “thought he was the only one speaking truth to power.” Flynn clashed with his civilian deputy, David Shedd, and his supervisor, Michael Vickers, the undersecretary of defense for intelligence, according to Clapper.

“I think he was a one-trick pony,” McCaffrey said. “He and McChrystal knew how to hunt down and kill or neutralize terrorist threats to the United States, and they were unbelievable at it, and Flynn was a part of it. Then they moved him into DIA.” There, McCaffrey said, “he was way over his head.”

In retrospect, the first signs of Flynn’s loss of touch with evidence came in this final military posting. Flynn, colleagues told me, would become fixated on an idea and demand that analysts find evidence to support it. This is when DIA executives began to speak derisively of “Flynn facts.” Flynn would say, for example, that Iran had killed more Americans than al-Qaeda had, a claim that could easily be refuted, but Flynn kept repeating it.

In February 2014, when he was not yet two years into the job, Flynn was summoned to Room 3E834 at the Pentagon. Vickers and Clapper, his two bosses, were waiting. The position was not working out, they said. He was fired, but allowed to hang on until he reached the minimum service required to retire as a lieutenant general.

“My problem was his impact on the morale of the workforce,” Clapper told me. “It was the stories about ‘Flynn facts.’ Very erratic, you know, he’d always contradict himself and give direction and then 10 minutes later contradict it. You just can’t do that, running a big organization.” For Vickers, Clapper suggested, “it was a case of insubordination” on issues relating to the Defense Clandestine Service. Both reasons for his firing hinted at an overweening confidence in his own apprehension of the world.

Flynn wrote in a memoir that President Barack Obama fired him because he did not want to hear Flynn’s warnings about the danger of Islamic extremism. Clapper calls that explanation “complete baloney.” Obama had nothing to do with Flynn’s firing, Clapper says, and neither did Flynn’s views on the Islamic State.

Flynn’s dissolution in recent years is a subject of considerable chagrin and embarrassment to his old brothers in arms. It is a forbidden subject for many of them, and an awkward one for others.

McChrystal, his longtime mentor and commander, is said by friends to have watched in horror as Flynn chanted “Lock her up!” at the Republican convention in 2016. He declined to be interviewed for this story. “Out of the respect for our service together, and years of closer friendship, I’m now just going to stay silent,” he told me by email. Retired Lieutenant General Keith Kellogg, once Flynn’s commander and later his White House colleague, wrote, “I have known Mike Flynn for many years going back to our days as Paratroopers in the 82d Airborne Division. As such, he remains a friend and [I] prefer to not talk about him.” My inquiries prompted many replies like those.

Former close associates of Flynn who did respond to my queries proposed varying explanations for Flynn’s behavior in recent years. One high-ranking officer said his extremism and conspiratorial bent may have been in him all along, but tamped down.

“The uniform constrains people’s political and emotional qualities,” he said. “You can misjudge a person because they are constrained by the job and the uniform.” When he takes off the uniform, “the personality that may have been constrained comes out.”

“Keep in mind, his reputation was built essentially as staff officer who’s got, you know, a really smart commander,” another top-ranking officer said. “You had Stan McChrystal, you know, holding both arms and keeping him focused.”

Clapper thinks it was Flynn’s humiliation at the DIA that started him down the wrong road. “Getting terminated a year early ate at him,” Clapper told me. “He had a grievance. And it just, it was corrosive with him, and he became a bitter, angry man and just latched on to anybody who was opposed to Obama and the Obama administration. That’s my armchair analysis of what happened.”

The humiliation of his subsequent firing as national security adviser and prosecution for lying to the FBI about conversations with the Russian ambassador to the United States (he pleaded guilty, then tried to withdraw his plea, and then was pardoned by Trump) only amplified his feelings of persecution, by this hypothesis.

But Clapper has another theory too.

“He spent a lot of time deployed, maybe too much, as it turns out,” Clapper said. “He spent a lot of time in Iraq and Afghanistan chasing terrorists, and I think that, to some extent, that consumed him.” An officer who worked closely with Flynn in the field told me, “If you spend years hunting terrorists and honing this killing machine,” some people “get unhinged by all that.”

One after another in my interviews, people who know Flynn speculated about the possibility of cognitive decline or a psychological disorder, then shied away. McCaffrey was the only person prepared to say on the record, “I think he was having mental-health problems.”

At every stage of his career in the Army, Flynn’s performance had been dissected and judged by a senior rater. Given his rapid ascent, he must have been promoted at least twice “below the zone,” or before he would normally have been eligible. Shouldn’t the Army have seen the seeds of Flynn’s unraveling?

McCaffrey said that that is asking too much. There are hundreds of generals in the Army, he said, and nearly 1,000 flag officers across the armed services. They are among the most rigorously selected people in any profession.

“As people get older, in particular, and as circumstances push in on them,” he said, “every year there’s some fairly small number who have mental-health problems … So yeah, some of them go bad. But Flynn went bad in one of the most spectacular manners we’ve ever witnessed. You know, it wasn’t just bad judgment. It was demented behavior.”

Demented, and well rewarded. Which is still another potential explanation for the Flynn we see today.

Somebody is making good money on the “ReAwaken America” tour. At $250 a ticket, the gate for the Canton event was in the neighborhood of three-quarters of a million dollars, not including sales of MAGA swag, Flynn memorabilia, Jesus hats, survival gear, vitamins and plant pigments marketed as COVID therapy, and, inevitably, MyPillow bedroom furnishings. Clay Clark, the emcee, is a Tulsa-based business coach who conceived of and organizes the tour; he holds the two-day events every month. Clark declined, in an interview, to say what Flynn’s cut is.

It could be that I am wrong about Flynn’s purity of belief. It could be that he is responding, rationally enough, to incentives. Flynn faced monumental legal bills in his criminal case, and there is a lucrative role in the MAGA ecosystem for someone who says the things that he says. John Kelly, the former White House chief of staff and a retired general, told me that Flynn “spent quite a bit of money” to defend himself. Perhaps, Kelly said, “he’s trying to make some of that money back.”

Then there is the lure of adulation. The latter-day Flynn is celebrated by adoring crowds. Standing onstage, he gets to be the hero once again.

Does Flynn imagine a political future? Sometimes it sounds that way.

He closed his Ohio appearance with a rallying cry.

“I’m trying to get this message out to the American people that now is the time to decide whether you’re going to be courageous or not,” he said. “I mean, this is it.”

I asked Joe Flynn whether his brother planned to run for office.

“I don’t think he’s interested in that at all,” Joe replied.

He wouldn’t be the last guy who got conscripted, however, and there is one political office for which Flynn has been on the shortlist before.

“I personally think he should become Trump’s running mate,” Clark said. “I’d love to see a Trump-Flynn ticket.”

In the closing days of the 2016 presidential campaign, when Trump flew to as many as five campaign events a day, Flynn became his regular warm-up act. “He was an amazingly popular opener,” Bannon told me. “He was as popular as Rudy [Giuliani], and Rudy’s pretty fucking popular with the crowd. Flynn was the most popular opening act we had.”

Trump, according to contemporary news accounts, looked hard at Flynn as a running mate in 2016 before selecting Mike Pence. Some Trump allies think that Flynn, who recently visited the former president at Mar-a-Lago, is back on the menu for 2024. “I think Mike [Flynn] could very well be on the VP shortlist in ‘24,” Bannon said. “And if the president doesn’t run, I strongly believe Mike is running.”

Roger Stone, the veteran operative of countless campaigns—and, like Flynn, the recipient of a pardon from Trump—told the Canton crowd to expect great things.

“There is one person who is absolutely central to the future of this country,” he said. “Absolutely central to the struggle for freedom that we face. This is a man who’s not a politician. I don’t think he much likes politics. This is a man who served his country. He’s actually a war hero … I speak of that great American patriot, General Michael Flynn.”

“And let me say this,” he added. “General Flynn’s greatest acts of public service lie ahead.”

Former White House counsel Pat Cipollone. (photo: Jabin Botsford/WP/Getty Images)

Former White House counsel Pat Cipollone. (photo: Jabin Botsford/WP/Getty Images)

A motley crew of unofficial Trump advisers had talked their way into the Oval Office and an audience with the president of the United States to argue the election had been stolen by shadowy foreign powers — perhaps remotely via Nest thermostats.

For hours, the group tried to persuade Trump to take extraordinary, potentially illegal action to ignore the election results and try to stay in power. And for hours, some of Trump’s actual White House advisers tried to persuade him that those ideas were, in the words of one lawyer who participated, “nuts.”

There was shouting, insults and profanity, former White House lawyer Eric Herschmann testified to the House committee investigating the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol. Herschmann said he nearly came to blows with Michael Flynn, a former national security adviser who was part of the Trump’s group of impromptu visitors.

“Flynn screamed at me that I was a quitter and everything. … At a certain point I had it with him,” Herschmann recalled in taped testimony that played at a Tuesday hearing. “So, I yelled back: Either come over, or sit your effing ass back down.”

Even for a White House known for its unconventional chaos, the Dec. 18, 2020, meeting was an extraordinary moment, demonstrating how Trump invited fringe players advocating radical action into his inner sanctum, as he searched for a way to remain in office despite losing an election.

“The west wing is UNHINGED,” declared Cassidy Hutchinson, a top aide to Trump’s chief of staff, Mark Meadows, in a text message sent as the meeting unfolded.

The rolling, hours-long shouting match was absurd, said Rep. Jamie B. Raskin (D-Md.), a committee member. But nevertheless, the night was “critical,” he argued, since it provided a forum for Trump to watch as his own advisers shot down, one by one, the false theories to which he had been clinging in hopes of staying in office.

“President Trump got to watch up close for several hours as his White House counsel and other White House lawyers destroyed the baseless factual claims and ridiculous legal arguments being offered by … Mike Flynn and others,” Raskin said.

Still, Trump was not dissuaded.

The wild session — during which Trump weighed seizing voting machines from key counties, deploying the National Guard to potentially rerun the election or appointing lawyer Sidney Powell as a special counsel to investigate the election — had been widely reported in past accounts of Trump’s final weeks in office.

But the committee, at its seventh public hearing on Tuesday, brought forward powerful and vivid personal testimony from six different participants — both those who wanted the president to act and those begging him not to do so — weaving them together in a video montage that intercut voices from both sides.

It took place four days after the electoral college met and, confirming the popular vote in key states, formally elected Joe Biden the next president. The committee showed clips of testimony demonstrating that Trump was told by everyone from Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) to Attorney General William P. Barr to Secretary of Labor Eugene Scalia — a lawyer and son of a deceased conservative Supreme Court justice — that there was no longer a legal path for him to remain in office, and it was time to concede.

Yet somehow, the delegation that included Flynn and Powell prevailed on a junior staffer to escort them into one of the country’s most secure facilities, where the group met for a time with Trump alone before any White House staffer even realized they were in the building.

Testifying to the committee via remote video, wearing oversized glasses and an animal print top, and sipping periodically from a can of Diet Dr Pepper, Powell — who had filed several unsuccessful lawsuits challenging the election — wryly explained that Trump’s aides came running when they realized what was happening.

“I bet Pat Cipollone set a new land-speed record,” she said, referring to the White House counsel.

For his part, Cipollone testified that he got a call that he needed to be in the Oval Office and rushed into the room. There, he spotted Flynn and Powell and another man he did not recognize

“I walked in, I looked at him and I said, ‘Who are you?’” said Cipollone, in one of a number of clips played by the committee of testimony given by Cipollone last week, after months of negotiations.

The man was Patrick M. Byrne, the former chief executive of the discount furniture outlet Overstock.com, who was helping to organize and fund Powell and Flynn’s efforts. Cipollone told the committee he was chagrined. “I don’t think any of these people were providing the president with good advice. And so I didn’t understand how they had gotten in,” he testified.

Cipollone was joined by other White House aides including Herschmann and staff secretary Derek Lyons, and the group listened as Flynn, Powell, Byrne and another lawyer working with Powell named Emily Newman assured Trump the election had been stolen. Meadows arrived eventually. Trump at times called other campaign aides and placed them on speaker phone.

“At one point, General Flynn took out a diagram that supposedly showed IP addresses all over the world, and who was communicating with whom via the machines and some comment about, like, Nest thermostats being hooked up to the internet,” Herschmann recalled.

The group recommended that Trump sign an executive order — they had brought a draft — that would appoint Powell as special counsel and instruct the Defense Department to seize voting machines, testimony showed.

But, according to Cipollone, the group was unable to answer one key question from Trump’s White House advisers.

“We were pushing back and asking one simple question as a general matter: Where is the evidence?” he recounted.

According to Cipollone, Powell and the others reacted with anger, suggesting that even asking the question was a sign that Trump’s White House team was insufficiently loyal to him. The committee emphasized the point by then showing a clip of Powell.

“If it had been me sitting in his chair, I would have fired all of them that night and had them escorted out of the building,” she testified.

All parties agreed the meeting was heated.

Three people familiar with the hours-long session told The Washington Post that the committee’s presentation captured the broad outlines of the meeting. They each spoke on the condition of anonymity to candidly describe the private meeting.

“The only thing that they didn’t quite capture was how loud and how profane it was. It was literally people just screaming and swearing and yelling at each other for hours,” one person said.

“Sidney Powell was screaming at the president that we were trying to undermine him the whole time,” said another person, who added that much of the meeting revolved around discussion of voting machines and Powell’s promise that if she could seize the machines, she could prove her theories.

A third person told The Post that Cipollone had his jacket on to leave for dinner with his family when he got the call about the meeting. “He thought he was going to be there for a few minutes, and he was there for many hours,” the person said.

It was Lyons’s last day as a White House official, and he planned to go to dinner with friends but was unexpectedly delayed in the Oval Office. Shouting could be heard from down the hall, the person said.

Herschmann testified that the screaming got “completely, completely out there.”

“It’d been a long day. And what they were proposing, I thought was nuts,” he testified.

The committee then immediately played a video of Trump attorney Rudy Giuliani, who had made his way to the White House that night and joined the meeting already in progress. Seated jacketless in a leather armchair and speaking in gravelly tones, Giuliani explained to the committee what he told Trump’s closest advisers that day: “I’m going to categorically describe it as, ‘You guys are not tough enough.’ Or maybe I put it another way, ‘You’re a bunch of pussies.’”

At some point, the meeting migrated to the Yellow Oval Room in the White House residence, where Trump served the group Swedish meatballs. (Byrne was “nonstop housing meatballs — he ate so many meatballs,” one person familiar with the gathering told The Post.) There the fighting continued.

By the end, after midnight, Powell testified that she believed that Trump had agreed to name her special counsel and extend her top secret clearance. Cipollone declined to explain to the committee what Trump said in the meeting but insisted no paperwork was ever filed to complete the appointment. Regardless, Lyons said Trump came away convinced the outsiders were working to keep him in office, as he desired. The meeting ended as it had started, Lyons testified: “Sidney Powell was fighting, Mike Flynn was fighting. They were looking for avenues that would enable it would result in President Trump remaining President Trump for a second term.”

At 12:11 a.m., with apparent relief, Hutchinson texted Anthony Ornato, then deputy chief of staff, that Powell, Flynn and Giuliani had left the building. She expressed amazement that Byrne — the former Overstock CEO — had been with the group. “Dream team!!!!” she wrote.

She then sent someone a photograph she had just taken of her boss, Trump’s chief of staff, escorting Giuliani from the building “to make sure he didn’t wander back to the Mansion.”

The White House aides might have been relieved to bring the meeting to a close. But at 1:42 a.m., Trump made clear which side in the debate had won his heart.

“Statistically impossible to have lost the 2020 Election,” he tweeted. “Big protest in D.C. on January 6th. Be there, will be wild.”

Robb Elementary School in Uvalde a day after the shooting. (photo: Jae Hong/AP)

Robb Elementary School in Uvalde a day after the shooting. (photo: Jae Hong/AP)

The video -- published by the Austin American-Statesman newspaper Tuesday, in a decision that enraged families of the victims who had yet to see the footage themselves -- shows responding officers approaching the door of the classroom within minutes of the shooter entering, yet retreating after the gunman opened fire at them.

After more than an hour -- with the hallway growing more crowded with officers from different agencies -- the doorway of the classroom was breached by law enforcement and the gunman was shot and killed.

The leak and subsequent release of the footage was particularly painful for the victims' families, including a group of parents and relatives who said they were blindsided Tuesday while in Washington, DC, to speak with elected officials. They expected to see the footage Sunday, when the Texas House Committee investigating the shooting planned to show it to the families before releasing it to the public.

"We get blindsided by a leak," said Angel Garza, whose 10-year-old daughter, Amerie Jo, was killed. "Who do you think you are to release footage like that of our children who can't even speak for themselves, but you want to go ahead and air their final moments to the entire world? What makes you think that's OK?"

The video, lightly edited by the American-Statesman to blur at least one child's identity and to remove the sound of children screaming, still leaves some questions unanswered -- in particular, why the law enforcement response was so delayed.

"They just didn't act. They just didn't move," Uvalde County Commissioner Ronald Garza said on CNN's "New Day" on Wednesday. "I just don't know what was going through those policemen's minds that tragic day, but ... there was just no action on their part."

The video also does not answer the question of "who, if anybody, was in charge," state Sen. Roland Gutierrez (D) told CNN on Tuesday.

"Even if we see 77 minutes in a hallway, it's not going to tell us who was in charge or who should have been in charge. And I think that's the sad statement of what happened on May 24 is that no one was in charge."

Gutierrez criticized the Texas Department of Public Safety for having a multitude of officers on site yet not taking control of the situation. The state agency has consistently pointed to Pedro "Pete" Arredondo, the Uvalde school district police chief, as the on-scene commander during the attack.

Arredondo was placed on leave as school district police chief in June and has not given substantial public statements about his decision-making that day despite intense public scrutiny, though he told the Texas Tribune that he did not consider himself to be the leader on the scene. On Tuesday, the Uvalde City Council accepted his resignation from his position as councilman.

Families of the victims said they were disturbed by the leaked footage, saying it was just the latest in a long line of examples of their wishes being pushed to the side. Officials say they had planned to show the footage to families this weekend before releasing it publicly.

"There's no reason for the families to see that," Uvalde Mayor Don McLaughlin said of the leak. "I mean, they were going to see the video, but they didn't need to see the gunman coming in and hear the gunshots. They don't need to relive that, they've been through enough," he said.

Officials harshly criticize video's early release

The Austin American-Statesman's decision -- along with TV partner KVUE -- to release the footage was harshly criticized by local officials who echoed the concerns of parents, saying certain graphic audio and images should not have been included.

"While I am glad that a small portion is now available for the public, I do believe watching the entire segment of law enforcement's response, or lack thereof, is also important," the chairman of the state House Investigative Committee, state Rep. Dustin Burrows (R) tweeted.

"I am also disappointed the victim's families and the Uvalde community's requests to watch the video first, and not have certain images and audio of the violence, were not achieved," he wrote.

In the first edited video, which is a little over four minutes long, audio captures frantic teachers screaming as the gunman crosses the parking lot after crashing his truck just outside Robb Elementary School's campus.

He then enters the school at 11:33 a.m., turns down a hallway carrying a semi-automatic rifle, walks into a classroom and opens fire. As the shots ring out, a student who had been peeking around the hallway corner at the gunman quickly turns and runs away.

Minutes later, officers rush into the hallway and approach the door, but immediately retreat to the end of the hall when the shooter appears to open fire at them at 11:37 a.m. Law enforcement continues to arrive in the crowded hallway but do not approach the door again until 12:21 p.m. and wait until 12:50 p.m. to breach the classroom and kill the gunman.

A second edited video, lasting almost an hour-and-a-half, was also published on the newspaper's YouTube channel.

In the footage, the sound of children screaming has been edited out, but the stark sounds of gunfire are still clearly audible and the gunman's face is briefly shown as he comes through the school doors.

"It is unbelievable that this video was posted as part of a news story with images and audio of the violence of this incident without consideration for the families involved," McLaughlin said in a statement.

The American-Statesman defended its decision, with executive editor Manny Garcia writing in an editorial, "We have to bear witness to history, and transparency and unrelenting reporting is a way to bring change."

McLaughlin also shared his disappointment that a person close to the investigation would leak the video.

"That was the most chicken way to put this video out today -- whether it was released by the DPS or whoever it was. In my opinion, it was very unprofessional, which this investigation has been, in my opinion, since day one," he said during a city council meeting Tuesday.

What will happen next

Despite the leak of the surveillance footage, the Texas House Investigative Committee still plans to meet with victims' families on Sunday and provide them with a fact-finding report as originally scheduled, a source close to the committee told CNN.

The report will show that there was not one individual failure on May 24, but instead a group failure of great proportions, the source said. Members of the committee also asked the director of Texas DPS, Col. Steve McCraw, to testify a second time on Monday to get further clarification on earlier sworn testimony before the Texas House and Senate, according to the source.

Meanwhile, some outraged family members took to social media to urge people not to share the video while families come to terms with the footage and the law enforcement behavior it reveals. "PLEASE PLEASE PLEASE DO NOT SHARE THE VIDEO!! We need time to process this!!," posted Berlinda Arreola, grandmother of Amerie Jo Garza.

Gloria Cazares, whose daughter Jacklyn was killed, also implored her Facebook family and friends not to share the video, saying it is "the opposite of what the families wanted!"

"If you are a true friend please do not share it, I don't want to see it in my feed nor do I want to be tagged on any of the news stations that are sharing it. Our hearts are shattered all over again!," Cazares wrote.

The Uvalde school district has scheduled a meeting on July 18 where McLaughlin said he hopes the City Council and victims' families will be able to get details about the return to school.

The school district previously announced that Robb Elementary School students will not return to the campus and will be reassigned to other schools.

Brett Rosenau. (image: Daily Beast)

Brett Rosenau. (image: Daily Beast)

The hunt for a wanted man in New Mexico ended with a house fire—and the death of a teenager whose aunt says the family knows a thing or two about police violence.

But the grim episode was made darker by the fact that the 15-year-old’s own father was killed by a member of one of the law-enforcement agencies involved in the incident.

Shela Rosenau, the boy’s aunt, said in an interview that the death last Thursday of her nephew, Brett, hit hard. Their relationship had only been rekindled in the last few years, after the teen reached out through Facebook with questions about his father’s family.

And she wondered if knowledge of his dad’s death at the hands of area cops might have factored into his own premature demise.

“I think that may be why little Brett—I think that’s maybe why he could have been scared of cops” and didn’t come out of the house last week in time, she told The Daily Beast.

Last Thursday, Albuquerque Police Department and the Bernalillo County Sheriff’s Department were pursuing an older man, Qiaunt Kelley, for alleged violation of parole when the man and teen went to a house in the city’s international district. Cops said Kelley had allegedly violated his parole for armed carjacking and stolen vehicle charges.

SWAT became involved in what turned into a standoff, and police sent “devices used to introduce irritants” into the home on San Joaquin Avenue SE, where the man had barricaded himself.

After a fire ignited, witnesses told reporters that police waited while the fire burned for nearly 40 minutes before Kelley was smoked out and arrested with burns on him. Police say that after they determined the smoke was coming from the house, the standoff ended.

It was only then that emergency responders went into the home to look for the minor, identified by police on Sunday as 15-year-old Brett Rosenau.

“Forty minutes of smoke inhalation will kill anybody. That’s common sense,” Shela Rosenau told The Daily Beast.

“So for them to wait 40 minutes, that’s just not right. That’s horrible,” she said. “I believe in that situation you save a life and they needed to go in there… I mean, that’s their job. They should not have sat back and waited for them to come out.“

After police extracted the boy from the flames, witnesses told Source New Mexico that his body was left in front of the home. Police said Rosenau died of smoke inhalation.

Deja, the daughter of the homeowners unrelated to the Rosenaus, told Source New Mexico that her family was pleading with police that there was a boy still inside.

“And they let him die, burn,” she told Source New Mexico.

Police now say they are investigating whether the fire could have been started by their own devices, similar versions of which have been known to cause fires.

The Bernalillo Sheriff’s Department referred requests for comment and questions by The Daily Beast to the Albuquerque Police Department.

The APD did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

“I know many people in our community are hurting right now, and appreciate everyone’s patience while the incident is thoroughly investigated,” said APD Chief Harold Medina in a statement released by the department on Sunday. “If any of our actions inadvertently contributed to his death, we will take steps to ensure this never happens again.”

Brett Rosenau’s father, also named Brett, was shot and killed on New Year’s Eve 2006 by a Bernalillo County Sheriff’s deputy while fleeing law enforcement on foot after a traffic stop, according to reporting by the Albuquerque Journal. Cops said the elder Rosenau was shot when he brandished a weapon at the pursuing deputy.

Shela Rosenau, who along with her relatives dispute that her brother had a weapon when he was killed, said the shooting had ruptured the family.

“You know, like, I don’t know, it just—it broke up that type of relationship that we could have had,” she said.

Three years later, the shooting was ruled “justified” by a grand jury, according to reporting by the Journal.

Although police were quick to state this week that the younger Rosenau “was not shot by anyone,” the boy’s death is the latest in many instances of deaths connected to Albuquerque police. In 2014, the Justice Department found Albuquerque cops “engaged in a pattern or practice of excessive force that violates the Constitution and federal law.”

While the ongoing consent decree that followed was targeted at the local police department, cops said that at least one member of the sheriff’s department behind the teen’s father’s death was also on hand at the raid.

It was at the elder Brett Rosenau’s funeral that Shela said she met Amanda Lopez, who was then pregnant with the future sports aficionado who would be named after his father. Shela Rosenau said the families have been estranged since.

In a statement released by her attorneys after the teen’s death, Lopez called her son a multi-talented athlete who was “a smart and funny young boy who walked to the beat of his own drum.” The boy was known by his mother as “pioneering” and not deterred by his smaller stature when playing sports like baseball and football.

“He was never shy to be affectionate and loving,” said the statement. “His mother was always amazed that he was never embarrassed when she would ask for him to hug or kiss her in front of his friends.”

After his death, the family is taking time to grieve and still “searching for answers,” said Lopez’s lawyer Taylor Smith.

“We also don’t want this to go swept under the rug,” said Smith. “So we along with the ACLU requested for an independent and transparent investigation into the police conduct.”

The boy, said his aunt, was ever curious about his father—and lawyers for the Lopez family confirmed that he was aware of the way that his own father had died.

“He was really excited to see some pictures that I sent to him [of his father]. He was just excited just to meet family” when he reached out over Facebook roughly four years ago, said Shela Rosenau.

She didn’t know him as well as others in his life, she said. But if their chats showed her anything, it was this:

“He's an awesome kid, “ Shela Rosenau told The Daily Beast.

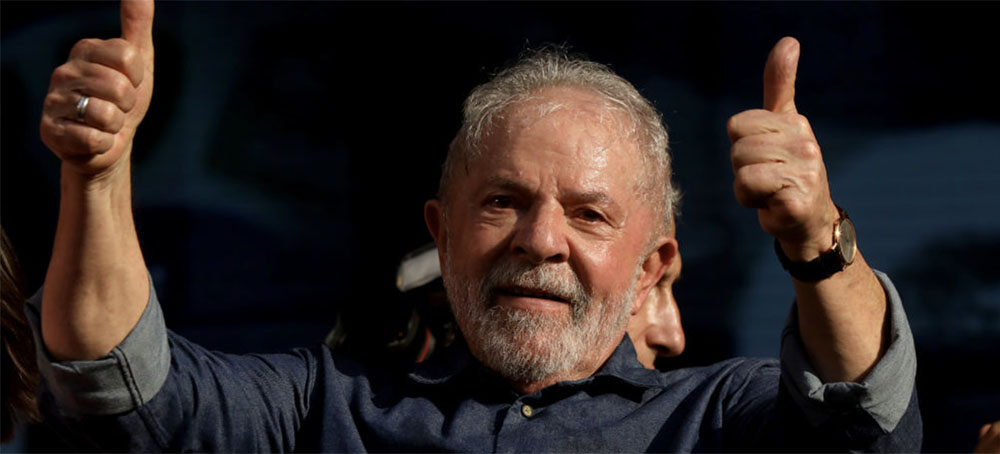

Former president of Brazil Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva gestures during a Labor Day demonstration on May 1, 2022, in São Paulo, Brazil. (photo: Rodrigo Paiva/Getty Images)

Former president of Brazil Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva gestures during a Labor Day demonstration on May 1, 2022, in São Paulo, Brazil. (photo: Rodrigo Paiva/Getty Images)

A few years ago, commentators were announcing the demise of the Latin American left. But if Lula wins this autumn’s presidential election in Brazil, the Left will be governing the region’s six largest economies for the first time.

Whether through elections (Argentina), “parliamentary coup” (Brazil), “silent coup” (Ecuador), or outright military coup (Bolivia), by the second half of the last decade, the left turn seemed to be giving way to the rise of a new right in the region. For their part, social movements appeared to be in a state of fatigue or, even worse, direct confrontation with left governments, and initially lacked the energy or will to defend them against the right-wing assault.

It is no small feat, then, that today there is no better place for thinking about alternatives to neoliberalism and authoritarianism than Latin America. Gustavo Petro’s historic win in Colombia will likely be joined by Lula’s success in Brazil’s October presidential election to conclude a cycle of electoral victories for the Left. By the end of the year, for the first time in its history, Latin America’s six largest economies — Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru — should all be under left-wing rule of one kind or another.

Gaining New Ground

The renewal of the pink tide brings with it the prospect of a return to the progressivism and promise of regional integration that accompanied the initial rise of the pink tide two decades ago. But there is also much that is new, both in the socioeconomic context and the character of their political coalitions.

Only two governments that were part of the initial pink tide — Nicaragua and Venezuela — remain in power. Other pink tide governments that were previously ousted, like those in Argentina, Bolivia, and potentially Brazil, have returned to power after reconfigurations in their parties and leadership. More significantly, however, several countries that for various reasons had not joined the previous pink tide — Colombia, Honduras, Mexico, Peru, and Chile — have all come under left-wing governance, through very different scenarios than those that gave rise to the initial Pink Tide.

These countries had been Washington’s closest allies in the region. All have implemented free-trade agreements with the United States, while Colombia, Peru, and Mexico are key regional nodes in the “war on drugs.” Colombia has long played the role of US proxy in undermining and destabilizing the Left in the region. The electoral victories of the Left in these countries are remarkable not only for overcoming persecution and violence in the name of anti-communism but also in dealing a further blow to already declining US hegemony in Latin America.

The Left’s success is a clear signal that the neoliberal hegemony of the 1990s that was first broken by the pink tide governments was never fully restored by their right-wing successors. Characterized by low popular support, fragmented ruling coalitions, and lack of an economic agenda, these recent right-wing experiments never achieved the dominance or duration of their predecessors, and their failure opened the way for the Left’s return.

More important, these electoral victories are testimony to the strength of social mobilizations that have swept the region in recent years, even if most of the new left governments did not emerge directly from them. Whereas the right-wing dictatorships of the 1970s and ’80s wiped out civic, labor, and campesino movements, destroying the Left for at least two decades, the repression unleashed by more recent right-wing governments failed to extinguish the Left.

Even before the pandemic hit in 2019 and continuing through to 2022, thousands upon thousands of people across Latin America have engaged in sustained protests as part of the region-wide estallido social against International Monetary Fund (IMF)–backed austerity policies. In Argentina, Chile, Colombia, and Ecuador, a reconstituted radical movement was able to forge a powerful street presence, weakening neoliberal governments and — with the exception of Ecuador — opening the way for progressive governments to come to power.

Renewed Social Mobilization

In Argentina, Bolivia, and Brazil, the Left might have been weakened, yet it nonetheless demonstrated that it had built sufficient power outside the state to withstand the assault from the Right and return left governments to power.

In Bolivia, social movements that had laid the foundations for the Movement for Socialism (MAS)’s initial rise to power in 2006 under Evo Morales were just as crucial in opposing the Jeanine Añez government after the 2019 coup. Sustained protests forced Añez to eventually hold elections in October 2020 after they had been canceled twice.

The tensions that had arisen under the MAS government did not prevent even its most ardent left critics from mobilizing in support of the MAS under the new leadership of Luis Arce — as well as rallying in support of the decision to jail Añez for her role in the coup. The vice presidential candidate David Choquehuanca, who identifies as Aymara, was able to regain the support of indigenous groups who had previously been frustrated with the MAS, including leaders who had criticized Morales.

In Brazil, ties between the Workers’ Party (PT) and social movements that had been weakened under PT governance were revitalized in the face of the soft coup against Dilma Rousseff and repression from the Jair Bolsonaro government directed against social movements. Lula’s choice of the former conservative governor Geraldo Alckmin as his running mate has not stopped the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST) and other left organizations from supporting his presidential candidacy in the October elections, rejecting other proposals for a broad-based front against Bolsonaro led by a nonleft candidate.

This is possible because the PT is still seen as the party where social movements can most effectively push their agendas. The MST has supported the formation of popular committees with the aim of developing an agenda from popular movements to ensure the demands of the working class reach Lula’s presidential agenda.

Only in Ecuador did the frictions between the previous Rafael Correa government and social movements prevent the return of Correísmo to power. Andrés Arauz ran for president last year as the candidate of the Union for Hope (UNES). UNES was set up as a reconstituted version of Correa’s previous party after his former vice president Lenín Moreno’s betrayal of Correa and the Citizens’ Revolution.

Arauz and UNES continued to enjoy remarkable popularity despite Moreno’s dirty campaign. However, the conservative banker Guillermo Lasso’s victory against Arauz in the 2021 elections was facilitated by long-standing divisions between Ecuador’s powerful indigenous movement and Correa’s Citizens’ Revolution. In the second round of the elections, Pachakutik candidate Yaku Pérez called on supporters to cast a null vote, arguing that neither the extractivism of Correísmo nor Lasso’s neoliberalism represented indigenous communities.

The indigenous movement itself was divided on its stance towards Correismo, with Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE) president Jaime Vargas dissenting at the last minute to give his support to Arauz. But this did not prevent 1.7 million Ecuadorians from voting blank, ensuring Lasso’s victory. Defenders of the null vote argued that they can bring down Lasso’s government through mass mobilizations, such as those which are currently bringing the country to a standstill.

Building New Coalitions

In countries where the Left has been elected for the first time, parties have adopted a different strategy toward social movements than initial pink tide parties. Whereas in the 1990s and 2000s, explosive revolts brought neoliberal governments to their knees and directly propelled left governments to power, recent left governments have emerged through more gradual processes of coalition-building against the background of social protest and exhaustion of the neoliberal right.

In Chile, student protests, teachers’ strikes, indigenous conflicts, and pensioners’ and feminist movements have been building for over a decade. This revitalized left provided the groundwork for sustained social mobilization when the estallido social broke out in 2019. The estallido also created a space for a new alliance between the student movement’s Frente Amplio (FA), the Communist Party, and other movements, leading to the formation of Apruebo Dignidad.

Throughout the 2010s, the FA followed a strategy of building power in state institutions, both national and local. During the 2019 mobilization, the FA spoke out for the protesters, demanding that right-wing president Sebastián Piñera lift a state of siege. It brought the issue of human rights violations before the International Criminal Court and sought to impeach Piñera on those grounds.

Similarly in Colombia, a decade of mass mobilizations — including the 2011 and 2018 student protests, the 2013 and 2016 agrarian strikes, and the national strikes of 2019 and 2021 — precipitated a crisis for right-wing Uribismo. Combined with the signing of the 2016 peace agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC rebel movement, this opened the way for a major shake-up of the political scene.

The country’s new president, Gustavo Petro, was not a protagonist of these mobilizations, and after his two decades in public office many Colombians would see him as part of the political establishment. Nonetheless, it was these mobilizations that made possible the building of Petro’s Pacto Historico political alliance, composed of a variety of movements including the Communist Party, Unión Patriotica, Congreso de los Pueblos, and indigenous and environmental movements.

During his time as mayor of Bogotá, Petro became the figurehead for popular protests when the attorney general, Alejandro Ordoñez, attempted to remove him from office for his attempt to reverse the privatization of the city’s waste disposal. In 2013, Petro led a mass occupation of Bogotá’s central Plaza Bolívar, which was renamed “Plaza de los Indignados.” The movement behind Petro brought together an array of groups affected by the hard-right attorney general: feminist pro-choice activists, LGBTQ movements, and the anti-bullfighting campaign.

Although Petro himself was not a leader of the national strikes of 2019 or 2021, his running mate, Francia Márquez, an Afro-Colombian environmental and feminist activist and human rights lawyer, spoke out regularly in defense of the human rights of the protesters. In his 2022 election campaign, Petro amplified the demands of the protesters, promising to dismantle the ESMAD riot police, revoke the military service requirement for young men, and transfer the police force to the control of the Ministry of Justice.

In Honduras, Xiomara Castro’s party (Libre) emerged out of the massive grassroots opposition that developed after the coup against Manuel Zelaya in 2009. The National Front of Popular Resistance united women’s, labor, campesino, LGBTQ, and indigenous movements. Over the course of several years, they built a potent street presence, combining mass mobilizations with international pressure on the regime.

Economic Storm Clouds

Another feature distinguishing the renewed pink tide is that it has emerged in a very different economic moment. Latin America was the continent most impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. GDP growth might have reached over 6 percent last year, but this was insufficient to compensate for the 6 percent contraction of 2020.

Already in the five years prior to the pandemic, the region had experienced a “lost half decade” of low growth. With economic collapse in 2020, modest recovery in 2021, and weak growth forecast in 2022, the region faces another “lost decade” of development. Twenty-five million people lost their jobs during the pandemic, and those who have found new employment since then face lower-quality, more precarious work.

Global commodity prices have risen, but this trend does not offer the same opportunity for Latin American countries as it did in the 2000s. The previous commodities boom was primarily driven by sustained growth from China and other emerging markets, which created a high demand for raw materials. The current price hike has been driven by COVID-induced supply chain disruptions and the war in Ukraine rather than an economic boom.

With China facing economic difficulties, commodity prices are unlikely to experience prolonged growth, instead becoming more volatile. Any rise in prices will equally be offset by shortages and higher prices for imports. While the previous pink tide had presided over a boom, current left governments are faced with the prospect of presiding over a bust.

Forging a New Model

The US Federal Reserve’s decision to raise interest rates will see investors flee developing economies for “safe havens” like the United States. In response, Latin American central banks are raising their interest rates in the hope of appeasing flighty foreign investors — but this comes at the cost of workers at home.

Latin America entered the pandemic with high levels of public debt, and from 2019 to 2020 debt levels rose from 69 to 79 percent of GDP. Despite the IMF’s changing rhetoric since the 2008 crisis, in practice, the fund has not backed down on its commitment to austerity. Major battles over the cost-of-living crisis and public spending such as that currently being fought on the streets of Ecuador are likely to spread.

Without the magic bullet of a commodities boom to fund social programs, new left governments will have to start by reducing inequality through structural reforms, with a more redistributive tax system and increased social spending. With the institutions of state power divided under most left presidents, attempts to do so will face conflict. In the course of such battles, governments can build bases of popular support.

Dim economic times can also present opportunities. The end of the commodities boom has reduced the prospects for economic growth but also opens the door for a more radical agenda going beyond the previous pink tide’s economic strategy based on national resource extraction.

Colombia’s Petro and Chile’s Gabriel Boric have promised to put environmentalism at the top of their agendas. Petro has vowed not only to end new oil exploration in Colombia but also to work with other progressive leaders on a regionwide just transition. Boric participated in Our Green America, a movement proposing a blueprint for a post-pandemic Green New Deal, and he has signed the Escazu Agreement on environmental justice.

Although the relationship between these new left governments and social movements is yet to be defined, this fresh direction opens the door to novel alliances with environmental and social movements that had been strained under previous left governments. This in turn creates possibilities for the Left to build power outside the state to push for a more radical agenda under the renewed pink tide.

A barrier Island. (photo: Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

A barrier Island. (photo: Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Barrier islands may not be such a good barrier anymore.

The fate of barrier islands like Alabama’s Dauphin Island and New York’s Fire Island is important for all coastal residents, even if they don’t live on them. Barrier islands shield the mainland from hurricanes, waves, erosion, and flooding, taking the brunt of a storm’s early blows. Without them, experts say hurricane damage to towns and cities inland would be even worse. Last year, Louisiana’s Grand Isle, the state’s only inhabited barrier island, faced Hurricane Ida head-on. Nearly half the homes there were demolished, and no structure was left untouched.

“These findings can be applied all over the world, but they may be particularly significant in the U.S., where houses are being built extremely close to the beach,” said Giulio Mariotti, a coastal scientist at Louisiana State University and lead author of the study, in a release. Previous studies have estimated that 13 million Americans could be displaced by rising seas, and $1 trillion worth of coastal real estate could be flooded by the end of the century. In May, a viral video of a stilted vacation house on a barrier island in North Carolina’s Outer Banks offered a picture of Americans’ precarious existence on the coast when it collapsed into the ocean.

The scientists created a model based on measurements from a string of islands off the Virginia coast. The islands are uninhabited, so they’re useful for studying a system free of common interventions like sea walls or jetties. Even though climate change has accelerated sea level rise over the past century, the Virginia islands have experienced little change to how fast they migrate, meaning they erode and build up sand in different places, leading them to shift location over time. The model shows that won’t always be the case.

As the seas modestly rose over the last 5,000 years, they created a vast reserve of sand and muck across the coast. Over the last century, storms and tides have devoured that sediment, clearing the way for barrier islands to shift gears. Now that the reserve has been depleted, the scientists expect rising sea levels will hasten the islands’ movements. Even in the unlikely case that the pace of sea level rise remains the same, scientists predict the rate at which the Virginia islands retreat will accelerate by 50 percent — from 16.5 feet per year to 23 feet — in the next century. If the seas keep rising, as experts expect they will, the islands would get pushed even closer to shore, leaving coastal communities even more vulnerable.

“This study shows that what we are seeing out there today is only a hint of what’s to come given increasing rates of sea level rise, and what is likely in store for developed islands globally,” said Christopher Hein, a co-author of the study and coastal geologist at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science.

The scientists noted their prediction may be conservative, since their model doesn’t account for the strength and frequency of storms, both of which hurry barrier islands toward the mainland.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.