Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

ALSO SEE: Georgia Sticks It to Putin: We Still Want to Join NATO

The all-consuming war in Ukraine has caused Russia to drop the ball elsewhere, officials who spoke with The Daily Beast revealed.

The officials, including members of the opposition Syrian National Army (SNA), said Moscow has withdrawn from several areas in northwestern Syria near the Turkish border, including Tal Rifaat, where Ankara has said it would carry out a military operation to combat the U.S.-backed Syrian Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), which Turkey considers a terrorist group.

The SNA, a coalition of rebel groups backed by Turkey, would take part in the possible operation, according to Yusuf Hammoud, an officer and former spokesperson for the SNA.

Hammoud, who is based in northwestern Afrin, Syria, said Russia has cut its presence in areas around Aleppo and Tal Rifaat.

“It will make it easier for Turkey to win this war,” Hammoud told The Daily Beast.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has said that his country will carry out a military operation in the northwestern cities of Tal Rifaat and Manbij near the Turkish border to create a “safe zone” where 1 million Syrian refugees could return.

Tensions between Syrian refugees and locals in Turkey have been rising, putting domestic pressure on Erdogan, whose popularity has declined amid an economic crisis a year before national elections are due.

If there is an attempt to take these areas, it risks a direct confrontation between NATO member Turkey and groups allied with Russia.

Beyond engaging in conflict with possibly several armed groups, an incursion could also have a heavy humanitarian toll, leading to the death or displacement of people who have gone through 11 years of Syria’s civil war.

The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights said that Turkey’s 2019 offensive against Kurdish forces in the northeast led to the displacement of more than 150,000.

Erdogan has not said when the offensive will begin.

“Like I always say, we’ll come down on them suddenly one night. And we must,” the Turkish president stated at the end of May, according to the Associated Press.

Ankara insists the YPG, which has cooperated with the U.S. in its fight against ISIS, is an offshoot of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), which has waged a decades-long insurgency in Turkey, leading to tens of thousands of deaths.

Turkey, the U.S., and the EU consider the PKK a terrorist organization. Ankara has carried out four previous incursions into Syria, including against the YPG.

Turkey’s presence in Syria has put Ankara at odds both with its NATO allies and powerful competitors, including Russian President Vladimir Putin, who backs Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

While Erdogan has continued support for opposition rebel groups, he has had to placate the competing interests of Russia, a nearby nuclear power with a permanent UN security council seat and a crucial source of energy and tourism to Turkey.

After Moscow introduced economic sanctions against Turkey for downing a fighter jet in 2015 that Ankara said had violated its airspace, Russia said Erdogan had apologized for the incident.

If the Kremlin now tacitly accepts a Turkish incursion into areas it or its allies control, it could be seen as a sign of how the invasion of Ukraine has overstretched the Russian military and it can no longer enforce its interests or its allies, even against a country with less geopolitical weight and military power.

The Turkish government did not respond to The Daily Beast’s request for comment on the possible operation.

U.S. State Department spokesperson Ned Price has expressed concern over the possible operation, stating it would undermine regional stability, and put U.S. troops and the fight against ISIS at risk.

Moscow’s Syria envoy stated that Russia has tried to convince Turkey not to go ahead with the military operation, Russia’s state news agency Tass reported.

Still, Moscow-based analyst Kerim Has, who specializes in Turkish-Russian relations, said that Russia could give Turkey a green light to launch an offensive, despite its public comments.

Has stated that if Turkey, or groups it backs, take control over Tal Rifaat, that could lead to an attempt to take nearby Aleppo, controlled by Russia’s ally, Assad.

Has believes Russia’s war in Ukraine has made Moscow more dependent on Ankara, a NATO member that has not imposed sanctions on Russia and which could serve the Kremlin’s interests by delaying NATO membership for Sweden and Finland.

“Mr. Edrdgan’s hands are stronger now in regards to Russia compared to four months ago,” Has said.

He added that since Russia would want Erdogan to win the upcoming election, Moscow could allow the incursion to boost the Turkish president’s popularity among his nationalist base.

Hammoud, with the SNA, said that Iranian forces were taking over some of the areas the Russians have retreated from.

Ahmad Misto, a civil leader in northwestern Syria with a brigade in the SNA, stated that Iranian forces have taken control of areas around Aleppo and Idlib province in the northwest where Russia has withdrawn.

“The Russians still have political power over the [Syrian] regime but the Iranians have it military-wise on the frontlines,” Misto said.

He added that the pullback of Russian forces happened about one to one-and-a-half months after Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine.

Mohammad Ismail, a senior leader of the Kurdish National Council, based in Qamishli, northeastern Syria, said the increased presence of forces from Iran would provide more motivation for Turkey to go on the offensive.

“Some [areas] have noticed a Russian withdrawal and it was filled by Iranian forces instead. If Iran is increasing their influence, then also Turkey has to get in,” he said.

Turkey and Iran are long-time rivals, battling for influence in the region and taking opposing sides in Syria where Tehran backs Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

Ismail added there was a noticeable decrease in Russia’s presence a month ago, specifically in areas around Tal Rifaat, going towards the west of the Euphrates river.

Soon after, Erdogan announced on June 1 that the military operation would be carried out in Tal Rifaat, along with Manbij.

Ismail believes Kurdish forces would hand over territory to the Syrian regime for protection against a Turkish offensive.

The Syrian Democratic Forces said earlier this month that it may cooperate with Damascus if Ankara carries out an incursion.

That would be another motivation for an operation by Ankara as the increased regime presence could push civilians fearful of Assad towards the border, potentially leading to more refugees in Turkey.

But civilians in Syria also fear Turkey and its allies, said Ismail.

In 2020, a UN war crimes expert stated that the SNA may have committed torture and looting in northern Syria.

“There’s no clean war,” Ismail stated. “International forces [are] going to decide everything on the ground.”

Palestinians hold posters displaying veteran Al Jazeera journalist Shireen Abu Akleh, who was shot dead as she covered an Israeli raid on the Jenin refugee camp on May 11, 2022, in the West Bank city of Hebron. (photo: Hazen Bader/Getty)

Palestinians hold posters displaying veteran Al Jazeera journalist Shireen Abu Akleh, who was shot dead as she covered an Israeli raid on the Jenin refugee camp on May 11, 2022, in the West Bank city of Hebron. (photo: Hazen Bader/Getty)

The lawmakers, all of them Democrats plus two independents, called for "a thorough and transparent investigation under U.S. auspices" into the shooting death of Shireen Abu Akleh, a Palestinian-American reporter, in Jenin on May 11.

Israeli and Palestinians officials have exchanged recriminations over the incident, which has heightened tensions.

"It is clear that neither of the parties on the ground trust the other to conduct a credible and independent investigation," wrote the lawmakers, led by Senator Chris Van Hollen, in a letter to Biden, who is due to visit Israel in July.

"We believe the only way to achieve that goal is for the United States to be directly involved," they wrote.

A spokesperson for the White House National Security Council said the United States is not conducting an official investigation" but urged both sides to share evidence with each other. "We expect full accountability for those responsible," the spokesperson added.

The Israeli embassy said Israel conducted a thorough inquiry and "continues to call for an investigation with the United States in an observer role."

The Palestinian Authority said in late May its investigation showed Abu Akleh was shot by an Israeli soldier in a "deliberate murder."

Israel denied the accusation.

The Israeli military concluded "unless the bullet is handed over, it is impossible to determine which side fired the fatal shot," but the Palestinian Authority has refused to do so, the Israeli embassy said.

It denied any Israeli soldier "targeted a journalist."

The Israeli army had said shortly after the incident that Abu Akleh might have been accidentally shot by one of its soldiers or a Palestinian militant in an exchange of gunfire.

A bridge in Irpin, Ukraine, in April. (photo: Vladyslav Kranoshchok)

A bridge in Irpin, Ukraine, in April. (photo: Vladyslav Kranoshchok)

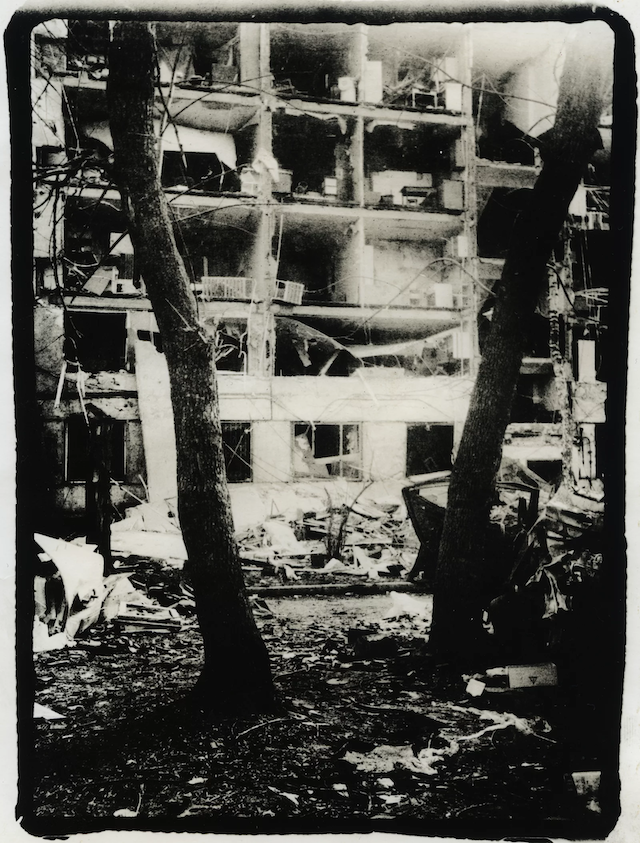

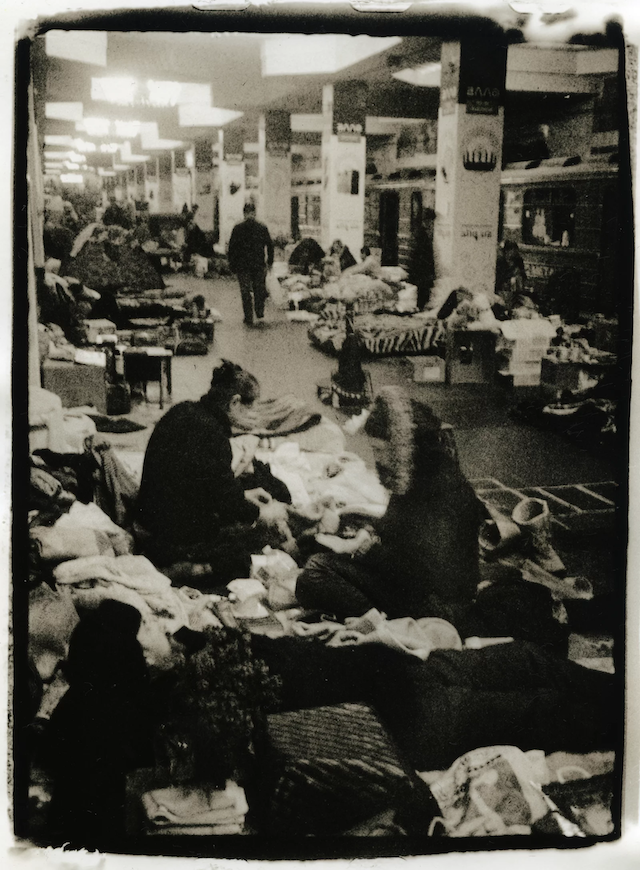

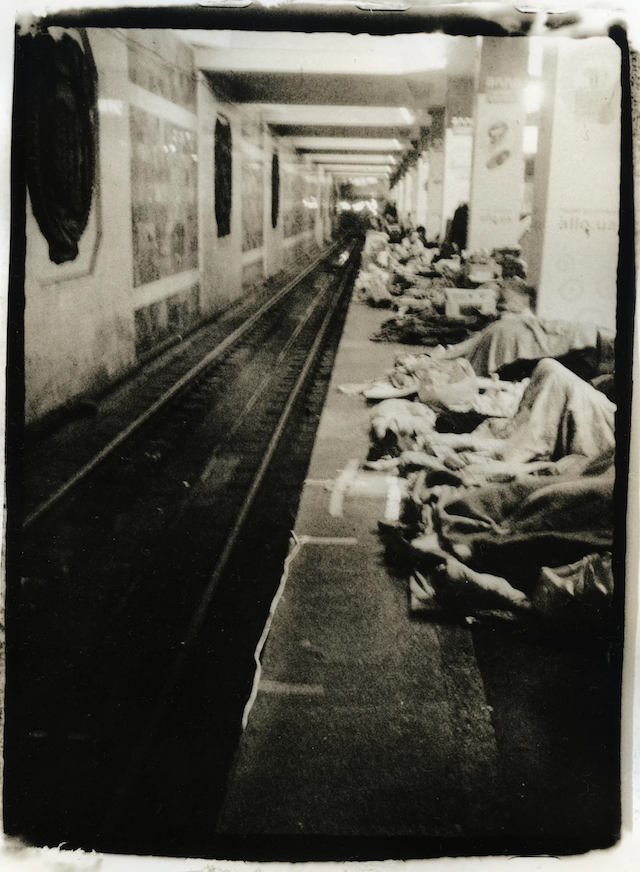

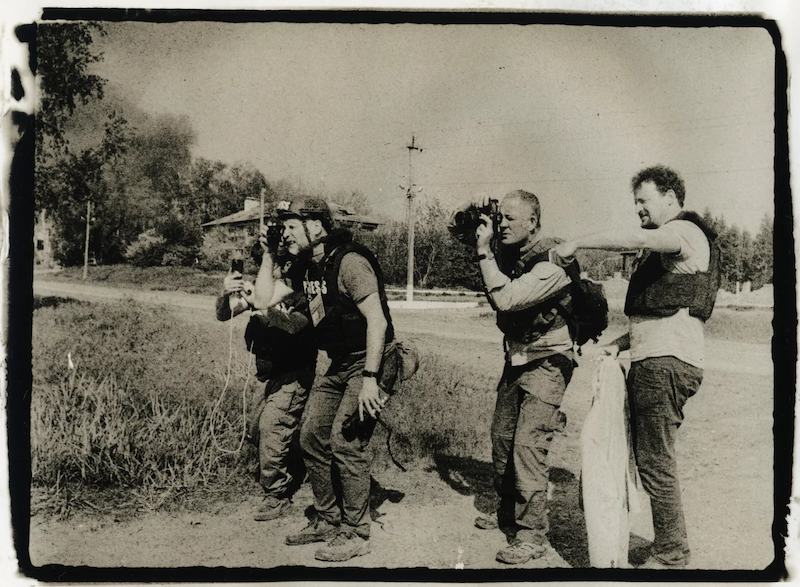

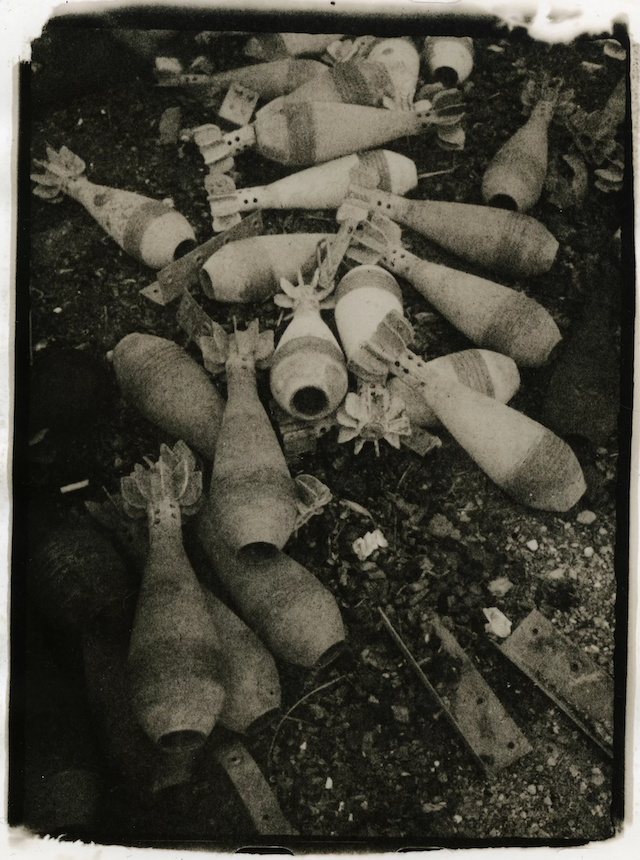

After Russia invaded Ukraine on Feb. 24, the country's second-largest city, Kharkiv, came under siege for nearly three months. The center of the northeastern city is just 30 miles from the Russian border. Russian troops quickly advanced on Kharkiv and pounded it for weeks with mortars, heavy artillery and cruise missiles. Hundreds of thousands of people fled, while others took shelter in cellars and the city's underground metro stations.

Krasnoshchok stayed put even as others sought safety farther west or left the country. But he didn't want to use underground bomb shelters.

"I never used basements or anything like that," he says, "because it's damp down there. It's cold and dark. I don't need that."

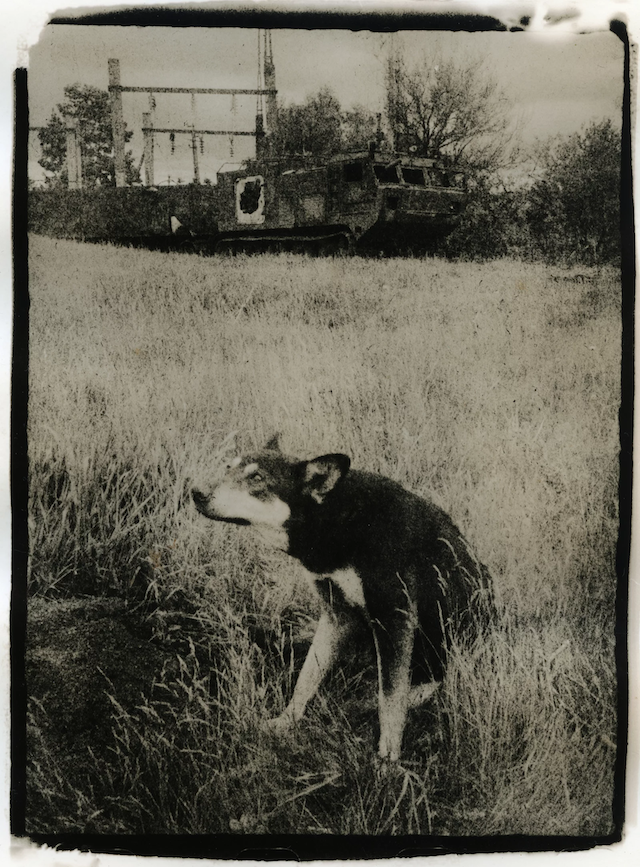

Krasnoshchok, who's 41, describes himself as a "geopolitical surrealist" painter. Once the war started, he wanted to document the way the invasion dramatically changed the country.

"I only work with the physical photos," he says about his choice to use an Olympus Pen S 35 mm camera from the 1980s loaded with black-and-white film rather than a modern digital camera. He develops the film himself and prints his images at his home in one of Kharkiv's residential neighborhoods. "I really believe my work differs a lot from the digital images because it's actually in front of you," he says. "This is, like, actual art, and this is really important for history."

During the early part of the war, Krasnoshchok started wandering the empty streets of Kharkiv with his camera. It was still winter. The snow contrasted sharply against the blackened, bombed-out apartment buildings.

"In just a 1 1/2 kilometer [almost 1 mile] radius from my house, there's a lot of destruction here," he says. "They've been shelling here a lot."

He says he found the stark, destroyed landscapes visually striking. "They remind me of some kind of post-apocalyptic pictures of cities like Chernobyl or Detroit," he says.

"Why do black and white? Because, with this method, I am fully controlling the whole process," he says. "From the moment I'm taking a picture, to using the chemicals, to actually printing it, to framing it — this is the purest way of making photography."

Krasnoshchok really wanted to do something creatively different from the many photographers documenting the war. "Everybody shoots with digital now," he says. "There are so many of them, and I'm pretty sure that if we look at all of their works, we're going to see a similar pattern to how they do it. With this physical method, I really believe that it's going to allow me to find my own point of view."

"In my art, I'm trying to study the composition and the structure of the image and its influence on the observer," Krasnoshchok says.

"I stay here mostly so I don't miss anything interesting."

He's sent some of his negatives and some of his paintings to a friend's home in central Ukraine for safekeeping. He posts many of his photos on Instagram.

But he grew up in Kharkiv. His house was passed down to him by his father. It's not just that Krasnoshchok doesn't want to leave, he wants to be here in his home city at this moment.

"A war, it's a unique thing," Krasnoshchok says. "Sometimes in a lifetime you have it once. Sometimes you don't have it at all."

As an artist, he wants to absorb it. He says he isn't worried about getting killed or a bomb dropping on his house because that's out of his control.

"I keep 90% of all of my art, all my belongings here because I believe that if a missile hits here or something happens here, I'm mentally prepared to say goodbye to all of this," he says, gesturing to his living room, which is covered in his paintings. "This is a wooden house — if something comes here, it's going to be absolute destruction."

Krasnoshchok says he makes his art first for himself and then he hopes that through his art, the viewer ends up seeing the world differently.

Privacy rights protect personal autonomy and shield survivors of abuse. They also conceal abuse and safeguard the powerful. Is the concept coherent? (photo: Andrew Brookes/Getty)

Privacy rights protect personal autonomy and shield survivors of abuse. They also conceal abuse and safeguard the powerful. Is the concept coherent? (photo: Andrew Brookes/Getty)

Privacy rights protect personal autonomy and shield survivors of abuse. They also conceal abuse and safeguard the powerful. Is the concept coherent?

Brandeis later pointed to Warren’s “deepseated abhorrence of the invasions of social privacy” in explaining why the two men published their famous law-review essay “The Right to Privacy,” in 1890. It decried invasions of “the sacred precincts of private and domestic life.” It deplored “the details of sexual relations” being “broadcast in the columns of the daily papers” and the publication of “idle gossip, which can only be procured by intrusion upon the domestic circle.” People should have legal recourse, it suggested, against those who publish private facts about them.

For decades afterward, courts debated whether the right to privacy existed. But, by the nineteen-sixties, many courts and legislatures had recognized such a right, in various forms, entitling people “to be let alone” and protected from incursions into their private affairs. The tort-law scholar William Prosser, an architect of modern privacy jurisprudence, noted in a classic 1960 study that the right to privacy had, confusingly, come to encompass rights against not only publishing private facts but also several other kinds of harm: portraying a person in a false light; appropriating a person’s name or likeness; and intruding on a person’s “seclusion.”

As privacy widened in scope, it seemed to grow in power. In the 1965 case Griswold v. Connecticut, the Supreme Court constitutionalized a right to privacy, ruling that prohibiting the use of contraceptives was unlawful because of “a right of privacy older than the Bill of Rights.” As Justice William O. Douglas, writing for the Court, put it, “Would we allow the police to search the sacred precincts of marital bedrooms for telltale signs of the use of contraceptives? The very idea is repulsive to the notions of privacy surrounding the marriage relationship.” Douglas, who married four times, explained that marriage is “intimate to the degree of being sacred” and promotes “harmony in living.” And so the constitutional right to privacy—which soon became the basis for the right to abortion and, later, the right to same-sex intimacy—was derived from the common law of marriage, in which an established doctrine of “marital privacy” had traditionally shielded the life of a married couple from interference.

Douglas’s repulsed imaginings drew on at least two distinct senses of privacy. First, privacy as secrecy: the idea that some personal matters, especially those of a sexual nature, should be sequestered from others’ view. And, second, privacy as autonomy: the idea that some personal decisions should be unimpeded by government interference. With marital sex serving as the paradigmatic private act—private in both senses—the rhetorical logic of Griswold suggested that the obvious importance of the first kind of privacy meant that the state must respect the second.

In Roe v. Wade (1973), the valence of constitutional privacy, helped along by the sexual revolution of the late sixties, broadened from sacred marital beds and domestic enclosures to personal autonomy and bodily integrity. People having control over decisions about their own bodies, free from the state, was the core liberty value that privacy represented. In Lawrence v. Texas, three decades later, the Supreme Court struck down a Texas anti-sodomy statute as an unjustified “intrusion into the personal and private life of the individual.” In effect, “Don’t look” had become “Hands off.”

The shifting terrain here invites the question of whether, when we talk about “the right to privacy,” we’ve been treating as interchangeable two terms that are merely homonyms: roughly, privacy as nondisclosure and privacy as noninterference. Justice Samuel Alito, in his leaked draft opinion overturning Roe v. Wade, asserted that the Court, in holding that privacy covered abortion, had previously “conflated two very different meanings of the term: the right to shield information from disclosure and the right to make and implement important personal decisions without governmental interference.” Alito’s purpose, of course, was to deny the constitutional basis for the right to abortion. And yet disaggregating the two concepts of privacy—the right to hide and the right to decide—may do the opposite, revealing both their interdependence and the contribution each makes to personal liberty.

Contemplating the overruling of Roe v. Wade, scholars have often speculated that abortion access might have been less vulnerable if it hadn’t been grounded in a right to privacy at all. (Some have seen a sturdier foundation in the equal-protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.) In the decades after Roe, many feminists argued that privacy had long offered a cover for the subordination and abuse of women in the home and in marriage; as one unit in the eyes of the law, husband and wife were alone in their privacy—including in instances when a wife sought protection against her husband. The feminist legal theorist Catharine A. MacKinnon, along these lines, sharply criticized the Supreme Court’s reliance on privacy to protect rights to abortion and same-sex intimacy. “Privacy works to protect systematic inequality,” she argued. The claim is particularly resonant at a time when Roe’s fragility is apparent.

Today, the right to privacy may implicate “everything from sexual intimacies and private scandals to police eavesdropping and computer data,” Amy Gajda writes in “Seek and Hide: The Tangled History of the Right to Privacy” (Viking). Although she notes the disparate interests that demand legal protection under privacy’s tent, her focus is on privacy as secrecy, on the right to prevent information about oneself from becoming public. Commentators these days regularly warn that Big Tech is getting rich by preying on our privacy for commercial purposes; they also point out that eliminating the right to abortion will disproportionately harm the poor and the marginalized. Yet Gajda, a journalist turned law professor, has a different story to tell. She contends that the right to privacy has, from the start, served the interests of rich men and élite society. “When we laud ‘The Right to Privacy,’ ” she writes, “we laud language influenced at least indirectly by a man—men, really—with much to hide.” Consonant with the feminist critique, Gajda’s theme is that privacy sounds “pretty darned great” until it’s used “to protect the most powerful, thereby shrinking public knowledge about the nation and its key players.”

Like Samuel Warren, early American proponents of privacy were powerful men with secrets to keep. Thomas Jefferson was bothered by innuendo circulating about his hidden life, which included his relationship with the enslaved Sally Hemings, who was a teen-ager when she first bore his children. Jefferson attacked the very press whose freedoms he had previously championed, and he encouraged the prosecution of a newspaper editor. But, as Gajda recounts, he also gave money to an editor who reported on Alexander Hamilton’s adulterous affair with the married Maria Reynolds. Hamilton, another champion of a free press, responded by complaining about the loss of his privacy. In letters exchanged in 1789, John Adams and William Cushing, soon to become a Supreme Court Justice, agreed that malicious press revelations of politicians’ “male conduct” should be punishable, even if true.

When President Grover Cleveland, in his forties, started dating the young daughter of a friend of his who had died (they eventually married) and newspapers began making insinuations about the relationship, he complained of the “outrage upon all the privacies and decencies of life” and demanded that reporters respect the “rights of privacy.” Gossip about a child born out of wedlock, domestic abuse, bacchanalian orgies, and his wife’s preference for the company of older men drove Cleveland to deliver an address at Harvard in which he emotionally condemned newspapers that “violate every instinct of American manliness, and in ghoulish glee desecrate every sacred relation in private life.” President Warren G. Harding, who had a secret child with one of his mistresses, persuaded journalists to adopt a national ethical code, which stipulated that “a newspaper should not invade private rights or feelings without sure warrant of public right as distinguished from public curiosity.”

Gajda’s point is that, throughout American history, enthusiasm for privacy has been linked to a truth that the #MeToo movement made familiar: privacy shields men’s conduct concerning women. The “sacred precincts” that Warren and Brandeis so wanted protected are often the unholy environs of privileged misbehavior. A person’s right to privacy can be at odds with the public’s “right to know,” which has been critical to the functioning of our democracy. Cue President Bill Clinton’s statement, with respect to his affair with a White House intern, that “even Presidents have private lives,” and President Donald Trump’s insistence on keeping private his financial dealings, which included hush-money payments to a porn star.

Look more closely at the jurisprudence of privacy in the postwar era and you see that the two kinds of privacy had very different trajectories. The cause of noninterference bounded from Griswold to Roe to Lawrence. The cause of nondisclosure, meanwhile, was largely in retreat, as the Supreme Court increasingly gave priority to press freedom. The vicissitudes of privacy were exemplified by the saga of Frederick Wiseman’s documentary “Titicut Follies,” which portrayed inmates in a state hospital for the criminally insane. A court limited access to the film in 1967, citing the right to privacy; in 1991, a court allowed the film to be shown to the public without restriction. Later in that decade, a woman who objected to a television show that aired closeup footage of her rescue from a car wreck that left her a paraplegic lost parts of her privacy case because, the California Supreme Court pronounced, “the desire for privacy must at many points give way before our right to know.”

Only recently has privacy as secrecy made something of a comeback. Nearly a decade ago, after Gawker published a video of Hulk Hogan having sex with a friend’s wife in that friend’s canopy bed, Hogan sought damages for invasion of privacy, in a suit funded by the tech billionaire Peter Thiel. The result was the biggest modern-day showdown between press freedom and privacy. Gawker’s brazen stance at trial—in a deposition, a former Gawker editor said that the site was entitled to post any celebrity sex tape it wanted, unless the video depicted a child under the age of four—didn’t bode well for its prospects. (Gawker said that he had answered “in a flip way.”) A 2016 verdict awarding Hogan a hundred and forty million dollars and the resulting demise of Gawker Media showed, Gajda says, the right to privacy “rallying back with full-nelson force.”

Gajda worries that “in our zeal for privacy” we will err in a direction that limits the public’s right to know. Still, her emphasis on privacy as a weapon wielded by the powerful means giving less attention to the protections that privacy might afford the vulnerable. In cases involving charges of rape, intrusive questions about an accuser’s sexual history used to be routine; efforts to limit them have been informed by privacy interests. Instances in which press freedom has trumped privacy, on the other hand, have included the right to publish a rape victim’s name, and sometimes video of the crime. Even when it comes to sexual assault, privacy cuts both ways.

The suspension of privacy can harm poor women in particular. In the realm of domestic violence, for example, one effect of the feminist critique of privacy has been the rise of police and prosecutorial policies that were developed to counter an older regime of abuse-shielding marital privacy. The policies, which focus on mandatory punitive enforcement, consciously override the wishes of the victim, and can result in a kind of state-imposed de-facto divorce. People who lack privacy as secrecy, simply because their living quarters leave them exposed, are especially subject to being reported to the authorities, which can encroach on privacy as autonomy. And these people are, disproportionately, poor women of color. Privacy rights, in short, can shield victims no less than victimizers.

Where Gajda casts journalism as privacy’s main opponent, Brian Hochman’s “The Listeners: A History of Wiretapping in the United States” (Harvard) focusses on the government’s eavesdropping. Hochman, a scholar of American studies, chronicles how electronic surveillance became “normalized” in the U.S. Although we once recognized that wiretapping was a “dirty business,” as Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes put it in 1928, we now, Hochman regrets, accept it as “a mundane fact of American life,” spurred by routine crime-control measures and the policing of people of color.

Soon after the Supreme Court expressed revulsion at the thought of police searching marital bedrooms, it heard the case of Charles Katz, a Los Angeles bookie whose communications of wagers while using a public pay phone were intercepted by F.B.I. agents who had bugged the phone booth without a warrant. The Court decided that this counted as a “search” under the Fourth Amendment, because “electronically listening to and recording the petitioner’s words violated the privacy upon which he justifiably relied while using the telephone booth,” even though it was in a public place. Katz v. United States (1967) is widely understood as an important win for privacy, but Hochman points out that the ruling also “articulated the conditions under which wiretapping and electronic eavesdropping could be construed as permissible”—such as when police get a warrant and limit the duration and the scope. The case thus set the stage for electronic surveillance “to become an ordinary tool of law and order.”

Americans, Hochman says, could have shut down electronic surveillance for good. President Lyndon Johnson even supported a Senate bill to stop government eavesdropping. Instead, we got law-and-order politics, which translated to racial politics, and helped domesticate wiretapping as a technique for criminal investigation. In 1994, the year that President Clinton signed a crime bill that has been blamed for ushering in a raft of further tough-on-crime measures and aggravating gross racial disparities, he also signed into law a bipartisan bill requiring telephone companies to design their equipment and services to enable surveillance and easily meet official requests for information.

For Hochman, the history of wiretapping ultimately feeds into the larger racial tragedy of mass incarceration and overcriminalization. Just as punishment and policing have had a disproportionate impact on Black communities, he notes, key moments in the history of wiretapping involve surveillance of Black individuals. The federal government eavesdropped on Black political leaders and civil-rights groups, from Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X to the Black Panthers and the Nation of Islam. Today, he writes, electronic surveillance has “turned up in cases involving drug dealers in Baltimore, undocumented immigrants in Detroit, and Black Lives Matter activists in Chicago.”

It’s striking that the two major social movements of the past five years, #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, respectively, lend their frames to Gajda’s and Hochman’s projects: too much deference to privacy serves male entitlement, on the one hand, and insufficient deference to privacy serves white supremacy, on the other. An oscillation between the two sets of concerns captures not only our unstable moral and social-justice intuitions, which often depend on who’s the violator and who’s the violated, but also the real trade-offs between privacy and competing concerns.

The F.B.I. notoriously wiretapped Martin Luther King, Jr.,’s home, office, and hotel rooms for years, seeking ways to discredit him, listening in on dozens of extramarital affairs, and, at one point, anonymously mailing him tapes of his sexual activities alongside a letter urging suicide to avoid exposure. In 1977, a federal court ordered the F.B.I. intercepts to be sealed at the National Archives until 2027. But they have been largely reconstructed and made available by the historian David Garrow, through clever Freedom of Information Act requests for wiretap transcripts of King’s associates. Unlike Garrow, whose examination of these private conversations, in “Bearing the Cross” (1986), resulted in a Pulitzer Prize, Hochman, who urges resistance to “intrusion into the most mundane corners of social life,” generally avoids using material that is available because of wiretaps. Indeed, his discussion of Garrow’s use of government intercepts omits mention of Garrow’s explosive publication, in 2019, of an F.B.I. agent’s notes about the contents of one particular hotel-room recording. (The recording, and the rest of the intercepts, will become available in five years.) The notes, released as part of the John F. Kennedy assassination records, state that King “looked on, laughed and offered advice” as a friend of his, a Baptist minister, raped a woman.

Readers looking for discussion of this contentious disclosure won’t find it in Gajda’s history of privacy, either, though she is not otherwise shy about describing allegations, even gossip, about prominent American leaders’ behavior. Should Garrow have published the allegations? Many people denounced him for doing so. They properly warned that we should not take as established fact a highly motivated F.B.I. agent’s account of what the recording contains. But they also recapitulated the familiar concern for the privacy of public men and invoked the privacy of female sexual partners, or victims. If all this seemed at odds with #MeToo and its suspension of male-protective privacy prerogatives, the collision of gender and race in public accountability remains deeply uncomfortable. We recognize that the privacy claims of oppressors may have to be restricted in order to curb their ability to oppress. The trouble is that the oppressor and the oppressed, the subordinator and the subordinated, aren’t two distinct groups. People who are victims in certain contexts can be victimizers in others. And so privacy claims—and privacy critiques—will routinely clash.

Privacy, in its various forms, is ultimately about control. The ethic of nondisclosure involves our ability to control access to information about ourselves, whether the information is favorable or unflattering. The ethic of noninterference involves our ability to control decisions about our own lives, for good or ill. When we disaggregate these meanings, it becomes easier to understand how their connection, through mutual reinforcement, is basic to personal liberty.

The knowledge that others—whether private citizens or the government—may be observing our words and actions against our will alters the environment in which our decisions are made; it makes it harder to exercise true control over personal decisions. What Alito dismisses as a conceptual conflation is better understood as a necessary alliance. As we head into a world without Roe v. Wade, the enforcement of abortion restrictions will depend, tellingly, on industrious efforts to ferret out information about individuals seeking, obtaining, and performing abortions. People arriving at certain clinics already find themselves filmed, their license plates recorded.

So it’s unfortunate but unsurprising that the use of one term to refer to the personal dimensions of both secrecy and autonomy has led to confusion over whether privacy really is a fundamental right. The problem arises when we take secrecy as an end in itself, and thus as the paradigm of privacy—an error that can be traced back to Warren and Brandeis’s parochial preoccupations. In truth, privacy with respect to the disclosure of information is an outgrowth of the deeper concern to preserve the conditions for individual autonomy, not the other way around. Rather than a prerogative of the privileged, intent on keeping the general public at bay, the right to privacy should have been understood from the start as a prerogative of the people, establishing a zone where the state cannot readily trespass.

Deciding where the zone extends and when that zone can be breached will always be a vexed and demanding process, because it takes place at the very interface between a polity and a person. Yet when we diminish an individual’s protections against the state the costs are far from insignificant. That shouldn’t be a secret. Personal autonomy, the ultimate value that privacy enshrines, doesn’t just buttress freedom; it is freedom.

The gun control measure, which the House is expected to pass, would enhance background checks, tackle the "boyfriend loophole" and provide "red flag" grants to states. (photo: Getty)

The gun control measure, which the House is expected to pass, would enhance background checks, tackle the "boyfriend loophole" and provide "red flag" grants to states. (photo: Getty)

The measure, which the House is expected to pass, would enhance background checks, tackle the "boyfriend loophole" and provide "red flag" grants to states.

The vote was 65 to 33, with all 50 Democratic-voting members and 15 Republicans, including Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, voting to send the bill to the House for a vote expected Friday.

“The United States Senate is doing something many believed was impossible even a few weeks ago. We are passing the first significant gun safety bill in nearly 30 years,” Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., said immediately before the vote. “The gun safety bill we are passing tonight can be described with three adjectives: bipartisan, commonsense, lifesaving.”

The measure would offer grants to states for “red flag” laws and crisis prevention programs. It would enhance background checks for people ages 18 to 21, opening the door to access to juvenile records. It also seeks to close the “boyfriend loophole” by keeping guns away from non-spouse dating partners convicted of abuse, with caveats to restore their access under certain circumstances.

In addition, the legislation would clarify which sellers are required to register as firearm licensees, which would require them to conduct background checks on potential buyers. And it would toughen penalties for gun trafficking.

The bipartisan package now goes to the House, where Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., vowed in a statement Thursday that she will bring the "life-saving legislation" to a floor vote Friday and "send the bill to President Biden" for his signature.

Sen. Chris Murphy, D-Conn., said: "Shooting after shooting, murder after murder, suicide after suicide — for 30 years, Congress stood in its political corners and did nothing. But not this time. This will become the most significant piece of anti-gun-violence legislation Congress has passed in three decades."

Murphy negotiated the modest collection of policies with Sens. John Cornyn, R-Texas, Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz., and Thom Tillis, R-N.C.

"I'm encouraged about how much common ground we were able to find," Cornyn said. "People who've suffered unthinkable losses in some of these mass shootings incidents. But I want to tell them that their advocacy has turned their pain into something positive."

The NRA opposed the bill, arguing that it "falls short at every level."

"It does little to truly address violent crime while opening the door to unnecessary burdens on the exercise of Second Amendment freedom by law-abiding gun owners," the group said in a statement.

In recent days, numerous GOP supporters sought to debunk right-wing claims that the legislation would curtail Second Amendment rights, vowing it would preserve gun rights for law-abiding Americans and that it would go only after criminals.

"If you're pro-Second Amendment, you should be for this bill," said Sen. Bill Cassidy, R-La.

The Senate voted the same day the Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution provides a right to carry a gun outside the home, delivering a major win for the NRA.

President Joe Biden, who as a senator helped craft gun laws in the 1990s, said he is looking forward to signing the measure into law.

"I am glad to see Congress has moved significantly closer to finally doing something — passing bipartisan legislation that will help protect Americans," he said in a statement after the bill cleared a key test vote earlier Thursday. "Our kids in schools and our communities will be safer because of this legislation. I call on Congress to finish the job and get this bill to my desk."

In a separate statement, the White House said the legislation "would be one of the most significant steps Congress has taken to reduce gun violence in decades, giving our law enforcement and prosecutors new tools to prosecute gun traffickers."

Cornyn emphasized the limitation of the boyfriend loophole policy.

“Unless someone is convicted of domestic abuse under their state laws, their gun rights will not be impacted,” he said this week. “Those who are convicted of non-spousal misdemeanor domestic abuse — not felony, but misdemeanor domestic violence — will have an opportunity after five years to have their Second Amendment rights restored. But they have to have a clean record.”

The negotiations were prompted by mass shootings in Buffalo, New York, and Uvalde, Texas, that killed a combined 31 people, including 19 schoolchildren. The shootings were 10 days apart, and there have been more mass shootings since then.

Imprisoned firefighters return after controlling a fire in California, U.S., in 2015 (photo: Robert Galbraith/Reuters)

Imprisoned firefighters return after controlling a fire in California, U.S., in 2015 (photo: Robert Galbraith/Reuters)

Imprisoned workers face disciplinary actions if they won’t perform tasks, ACLU finds, and often receive little or no pay.

In a nearly 150-page report released in mid-June, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the University of Chicago’s Global Human Rights Clinic said nearly 800,000 of the 1.2 million Americans imprisoned in state and federal prisons perform labour during their time behind bars.

The work of prison labourers – who, the report found, often work for as little as 13 to 52 cents per hour, and in certain states, do not get paid at all – has become the subject of debate over the legacy of racism in the American prison system.

“In addition to working under coercive and arbitrary conditions, incarcerated workers in U.S. prisons are often working for paltry wages or no wages at all,” the ACLU found.

The report, which relied on public records, questionnaires, and interviews with imprisoned people, found that more than 75 percent of respondents faced disciplinary action if they refused to perform certain tasks.

“These punishments can include the loss of visitation rights for loved ones and even solitary confinement,” Jennifer Turner, the report’s lead author and researcher with the ACLU, told Al Jazeera in a phone interview.

“One formerly incarcerated person told us he was held in solitary confinement because he refused to pick cotton for a facility that was built on a former slave plantation.”

The report found that more than 80 percent of imprisoned labourers perform essential tasks for the facilities that imprison them, from janitorial duties to cooking, laundry and maintenance work.

The pay for such work is typically 13 to 52 cents an hour, and in seven states — Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas — the majority of workers receive no pay at all, the report said.

In many states, wages have remained frozen for decades. In Vermont, the report noted, the pay for imprisoned workers was last revised in 1988, and is still set at 25 cents an hour.

“Incarcerated people not only replace workers needed for typically lower-paid maintenance work,” the report said. “But they also perform work that is typically well remunerated, saving prisons even more money.”

The report also noted that nearly 15 percent of imprisoned workers perform jobs for state-owned prison industries or public works, performing a variety of tasks that can include road work, auto maintenance, data entry, call centre work, and even firefighting.

Such work pays more than other prison labour, making between 30 cents and $1.30 a day, still substantially less than a free person makes.

In Oregon, the report noted, an imprisoned person doing work for the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) that would typically get $80 a day is paid between $4 and $6, and in Louisiana, imprisoned people make mattresses for 20 cents an hour.

Less than 1 percent of US prison labour is carried out for private industries, with the primary beneficiaries being local, state, and federal governments, the report said.

The US Bureau of Prisons (BOP), which oversees federal prisons, told Al Jazeera in an emailed statement that the humane treatment of those in their custody is a “top priority”.

Work programmes “reduce inmate idleness, while allowing the inmate to improve and/or develop useful job skills, work habits, and experiences that will assist in post-release employment”, the department said.

However, the study found that 70 percent of imprisoned workers said they received no formal job training.

Meanwhile, what little wages they do make are often eaten away by fees charged by prisons for everything from soap to food, to phone calls. Healthcare can also be prohibitively expensive for those behind bars, especially when paired with jobs that pay less than a dollar an hour.

The Prison Policy Initiative, a progressive criminal justice think-tank, said in February that for imprisoned workers who make between 14 and 63 cents an hour, a health fee of $2 to $5 is the equivalent of a $200 to $500 medical visit for someone who is not in prison.

“It is not unusual for more than 60 percent of an incarcerated person’s paycheck to be garnered by these fees,” said Turner. “Often, families that are already missing the income the person would be providing because they’re incarcerated end up helping pay, and go into debt.”

U.S. natural gas pipelines are experiencing the equivalent of one leak every 40 hours, a new report has found. (photo: Getty)

U.S. natural gas pipelines are experiencing the equivalent of one leak every 40 hours, a new report has found. (photo: Getty)

From 2010 to 2021, almost 2,600 such leaks occurred that were serious enough to require federal reporting — with 850 resulting from fires and 328 from explosions, according to the study, released by U.S. Public Interest Research Groups (U.S. PIRG) Educational Fund.

These incidents killed 122 people and injured 603, with total costs in property damage, emergency services and the value of unintentionally released gas totaling nearly $4 billion, the authors observed.

Such events also led to the leakage of 26.6 billion cubic feet of natural gas — the equivalent to more than 2.4 million passenger vehicles driven for a year, according to the report, published together with Environment America Research … Policy Center and the Frontier Group think tank.

“House explosions and leaking pipelines aren’t isolated incidents — they’re the result of an energy system that pipes dangerous, explosive gas across the country and through our neighborhoods,” co-author Matt Casale, environment campaigns director for U.S. PIRG Education Fund, said in a statement.

“It’s time to move away from gas in this country and toward safer, cleaner electrification and renewable energy,” he added.

To draw their conclusions, Casale and his colleagues sifted through federal leak reporting data available through the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration.

The authors — who referred to natural gas by its primary component of methane rather than using the word “natural” — stressed that the amount of gas leaking into the environment is likely far greater than the quantity captured in federal leak reporting.

Citing a Science study from 2018, they noted that leaks from gas lines over two decades had nearly doubled the climate impact of natural gas.

The resultant warming was on par with that of carbon dioxide-emitting coal plants, the study found, noting that while methane doesn’t persist in the atmosphere as long as carbon dioxide does, its warming effects are much stronger.

Natural gas releases can occur intentionally when a utility needs to lower pressure or empty pipelines for maintenance, or they can happen due to wear, equipment failure, natural causes, accidental force or puncture, according to the U.S. PIRG report.

While Environmental Protection Agency data showed that emissions from natural gas transmission had fallen significantly between 1990 and 2016, progress has slowed since, the authors found.

They also expressed concern that some information regarding deaths and injuries might not be available in the federal leak reporting database, since not all the leaks occur in the pipeline system.

A considerable volume of leaks might be overlooked particularly in urban areas, the report found, citing a 2021 Harvard University study.

That study, they explained, found that methane emissions from natural gas infrastructure and use in U.S. cities was two to 10 times greater than federal estimates indicated. Meanwhile, Boston’s emissions were six times higher than those reported by the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection.

More than half of those emissions came from non-pipeline sources both in and out of homes, according to the U.S. PIRG report.

“Leaks, fires and explosions are reminders that transporting methane gas is dangerous business,” report lead author Tony Dutzik, associate director and senior policy analyst at Frontier Group, said in a statement.

Moving forward, the report authors recommended that the U.S. curb its reliance on natural gas for home heating and cooking as well as for electricity generation.

They argued that policymakers should instead incentivize the transition to all-electric buildings and renewable energy. And in the interim, they suggested focusing gas infrastructure investments on fixing leaks.

“Fully protecting the public requires us to reduce our dependence on gas,” Dutzik added.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.