Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

A person places flowers outside the scene of the mass shooting at a supermarket in Buffalo, N.Y., on Sunday. (photo: Matt Rourke/AP)

A person places flowers outside the scene of the mass shooting at a supermarket in Buffalo, N.Y., on Sunday. (photo: Matt Rourke/AP)

It is also the 198th mass shooting in 2022. With just over 19 weeks into the year, this averages out to about 10 such attacks a week.

The tally comes from the Gun Violence Archive, an independent data collection organization. The group defines a mass shooting as an incident in which four or more people are shot or killed, excluding the shooter. The full list of mass shootings in 2022 can be found here.

Prior to the Buffalo attack, the largest-scale mass shooting this year was at a car show in Dumas, Ark., on March 19. That attack killed one person and injured 27.

Such shootings are an American phenomenon

Mass shootings, as is well known by now, are a common recurrence in the United States. Around this time last year, the U.S. had experienced a similar number of mass shootings: also about 10 a week.

We ended 2021 with 693 mass shootings, per the Gun Violence Archive. The year before saw 611. And 2019 had 417.

The massacres don't come out of nowhere, says Mark Follman, who has been researching mass shootings since 2012, when a gunman killed 12 people at a movie theater in Aurora, Colo.

"This is planned violence. There is, in every one of these cases, always a trail of ... behavioral warning signs," he told NPR earlier this month.

Follman, the author of a new book, Trigger Points, says the role of mental health is also widely misunderstood.

"The general public views mass shooters as people who are totally crazy, insane. It fits with the idea of snapping, as if these people are totally detached from reality."

That's not the case, he said. There's "a very rational thought process" that goes into planning and carrying out mass shootings.

The suspect in the Buffalo attack left behind a racist screed, donned body armor, and livestreamed the attack.

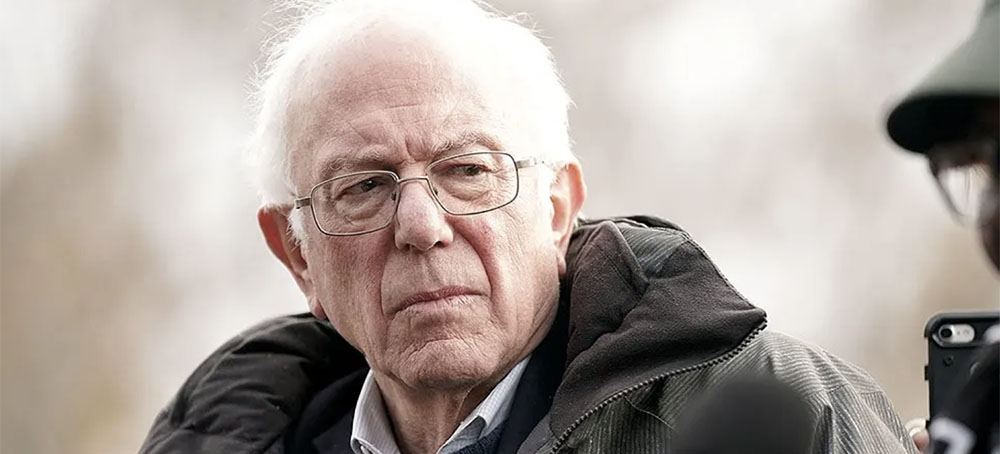

Bernie Sanders. (photo: The Hill)

Bernie Sanders. (photo: The Hill)

Sanders told host Chuck Todd on NBC’s “Meet the Press” that Congress should end the filibuster and then pass an abortion rights bill that all 50 Democrats in the Senate would support amid the looming threat of Roe v. Wade being overturned by the Supreme Court.

“I mean, people cannot believe that you have a Supreme Court and Republicans who are prepared to overturn 50 years of precedent,” Sanders said. “So I think what we should do is on this bill: end the filibuster, do everything that we can to get 50 votes on the strongest possible bill to protect a woman’s right to control her own body.”

The Senate failed to pass an abortion rights bill last week after opposition from both Republicans and moderate Democrat Joe Manchin (W.Va.).

Sanders told “Meet the Press” that Manchin and fellow moderate Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D-Ariz.) had “sabotaged” President Biden’s agenda by failing to support crucial legislation and an end to the filibuster in the upper chamber.

“It should not be a head-scratcher. You’ve got two members of the Senate, Sen. Manchin and Sen. Sinema, who have sabotaged what the president has been fighting” for, Sanders said. “You had two people who prevented us from doing it. You have a better word than sabotage? That’s fine. But I think that is the right word.”

Sanders said they should keep fighting to codify abortion rights into law, arguing “nobody should think that this process is dead.”

“We should bring those bills up again, and again, and again,” he said.

The inspector general's office of the DoJ confirmed the subpoena came from the Biden administration. (photo: Reuters)

The inspector general's office of the DoJ confirmed the subpoena came from the Biden administration. (photo: Reuters)

It was previously unclear if the order came from the Trump White House as the inquiry had spanned both presidents’ terms

In a statement to the Guardian, the inspector general’s office of the justice department confirmed that the subpoena was issued in February 2021 – shortly after Biden entered the White House. The action was taken in an effort to divine the identity of an alleged leaker, who was suspected of divulging to news outlets details of an inquiry into the previous Trump administration’s policy of separating children from their parents at the southern US border.

On Thursday, it emerged that the DoJ had secretly used a subpoena to confirm the phone number of Stephanie Kirchgaessner, the Guardian’s investigations correspondent. She had been the author of two reports in 2020 that revealed sensitive aspects of the child separation policy, including that Donald Trump’s then deputy attorney general, Rod Rosenstein, had given the green light for children of any age to be removed from their parents.

It was unclear at that point which administration had been responsible for issuing the subpoena, as the leak inquiry had straddled both the Trump and Biden administrations. Now the inspector general’s office of the DoJ has clarified that the move was made under the Biden administration.

Stephanie Logan, spokesperson for the inspector general’s office which acts as the DoJ’s internal watchdog and which was conducting the child separation inquiry, told the Guardian that the subpoena had been issued in February 2021 in compliance with “the requirements of the Justice Manual”.

The subpoena, she said, had been issued to a telecommunications company to confirm that “one specific telephone number already known to investigators … in fact belonged to a specific media outlet”. Investigators knew the phone number – Kirchgaessner’s, though Logan did not refer to the reporter by name – from their previous review of the phone records of an official in the inspector general’s office suspected of being the source of the leak.

Logan stressed that “the subpoena did not request, and investigators did not receive, the content of communications to or from the account holder’s phone number” or any other other details of the phone account.

The disclosure of the use of a subpoena to confirm a Guardian reporter’s phone number in a case that involved no national security concerns or classified information provoked strong criticism. The Guardian’s editor-in-chief Katharine Viner called the DoJ’s action “an egregious example of infringement on press freedom and public interest journalism”.

In July 2021, the DoJ under Biden’s newly appointed attorney general, Merrick Garland, announced a new policy that promised to restrict the use of “compulsory process to obtain information from, or records of, members of the news media acting within the scope of news gathering activities”. Advocates for increased federal protections for the press have complained however that there has been lackluster support from the Biden administration for stronger shield laws.

Last summer Ron Wyden, the US senator from Oregon, introduced new legislation to protect reporters from unnecessary government surveillance as a response to revelations about the Trump administration’s heavy-handed surveillance of journalists at CNN, the New York Times and other outlets. Wyden told the Freedom of the Press Foundation at the time that he had tried to enlist the support of the justice department for his new Press Act, but officials within the Biden administration had failed to engage.

The 'IN AMERICA: How Could This Happen' project artist Suzanne Firstenberg walks through the installation on Oct. 23, 2020, in Washington, D.C. At the time, the project honored each of the 225,000 lives lost in the U.S. from COVID-19 with a white flag. (photo: Jack Gruber/USA TODAY)

The 'IN AMERICA: How Could This Happen' project artist Suzanne Firstenberg walks through the installation on Oct. 23, 2020, in Washington, D.C. At the time, the project honored each of the 225,000 lives lost in the U.S. from COVID-19 with a white flag. (photo: Jack Gruber/USA TODAY)

The collapse of COVID-19 testing around the world may soon force governments to get creative with how they monitor infection rates.

That might seem like a dangerous combination. If authorities can’t accurately keep tabs on where and how fast the virus is spread, they might not be able to help protect vulnerable communities.

Fortunately, there’s one way to track SARS-CoV-2 without relying on drive-through testing sites or testing at pharmacies, clinics or hospitals. More and more, scientists are looking for the virus in sewer water. In our toilet flushes, in other words. “Wastewater seems to be the key to early detection, especially in the context of increased at-home testing and potentially reduced reporting,” Niema Moshiri, a geneticist at the University of California, San Diego, told The Daily Beast.

But there’s a big problem with this wastewater surveillance. Any method of monitoring a global pandemic itself needs to be global. While North America, Europe, Australia and parts of Asia have pretty good wastewater surveillance systems in place, China—the country that’s arguably the most vulnerable to COVID right now—doesn’t.

With China’s own individual testing hinging on Beijing’s unsustainable zero-COVID lockdown policy, the country should start shifting to wastewater surveillance, experts explained in a new scientific study. It won’t be easy.

It’s important not to overstate the recent slight increase in global COVID cases. A clutch of highly contagious new coronavirus subvariants—the children of the Omicron variant that first appeared last fall—are driving surges in cases in the United States, South Africa and a few other countries, potentially including North Korea.

Thanks to vaccines and lingering antibodies from past infection, these surges are nowhere near as bad—or as deadly—as previous surges. Amid an overall global decline in COVID, the USA saw an uptick in infections, from a year-low of 30,000 daily new cases in late March and early April to 85,000 daily new cases last week. South Africa meanwhile saw daily new cases rise from 1,300 to 7,700 over the same period.

Hospitalizations and deaths aren’t rising nearly as much, of course—again thanks to all those vaccines and antibodies. What’s perhaps more worrying is the decrease in testing that has tracked along with the increase in infections. At the same time COVID is surging, we seem to be losing our original tool for tracking the disease.

In the U.S., we were testing 2.5 million people every day at pharmacies, drive-through sites, and other locations that reported their test results to state authorities, which in turn reported them to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Today we’re testing just 55,000 people a day. Individual testing is collapsing in other countries, too.

There’s one very good reason for this drop. At-home tests are now cheap, reliable and readily available. The administration of U.S. President Joe Biden even provides eight free antigen tests per household.

When you test at home, there’s no obligation to report your results to the authorities. It’s possible millions of people all over the world are catching COVID, testing for it, self-isolating and recovering–all without their government knowing it.

Possible, but not likely. In the U.S., for one, the CDC acted quickly back in 2020 to set up a national wastewater-surveillance system that now includes 886 sites spread across the 50 states, tribal lands, and U.S. territories.

Testers scoop water from water-treatment plants, sewers, and septic tanks, test for SARS-CoV-2 and log the results. Sequencing random samples can determine exactly which variants and subvariants are present in a particular community. It was wastewater monitoring that warned us about a regional surge in the BA.2.12 subvariant of Omicron in and around New York starting in late March.

European countries, Australia, and countries across Asia have ramped up their own wastewater monitoring, too. A global surveillance system, one that doesn’t depend on voluntary individual testing, is taking shape.

It’s not perfect, of course. “Wastewater data are meant to be used with other COVID-19 surveillance data,” the CDC stressed on its website.

Wastewater surveillance “doesn’t provide the same degree of localization as clinical testing that is reported,” Rob Knight, the head of a genetic-computation lab at the University of California, San Diego, told The Daily Beast. “The Point Loma wastewater treatment plant in San Diego covers 2.3 million people, so you don’t know if the signal comes from specific areas as you would with clinical testing.”

However, home tests that are not reported don’t provide any public health information at all, so wastewater is better than that.”

The bigger problem is China. Not only do China’s 1.4 billion people account for 18 percent of the world’s population, China is more vulnerable to COVID than most countries. The Chinese government’s zero-COVID policy, which locked down city after city to prevent the virus from spreading, had a tragic side-effect.

For more than two years, almost no one in China caught COVID, meaning almost no one in China had natural antibodies when the extremely contagious Omicron variant and its subvariants showed up—and punched right through citywide lockdowns in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and elsewhere. It didn’t help that the Chinese government has pushed locally made vaccines that might not be as effective as the best Western-made messenger-RNA jabs.

Daily new cases in China peaked at 30,600 back in late April. They’ve since dropped to fewer than 10,000. But much of China remains locked down. And as long as that’s the case, individual testing isn’t really a problem. Health authorities in major cities can mandate and enforce frequent testing at government-run sites.

But experts agree: China’s zero-COVID strategy is unsustainable. Besides being very unpopular with many Chinese, it’s also driving down China’s economic growth and risking recession in China as well in countries that rely on trade with China.

If and when zero-COVID ends, individual testing in China could collapse the same way it’s collapsed in other countries. And there isn’t a countrywide wastewater monitoring system to pick up the slack in data. Yet. “To cope with the future challenges in public health emergencies, it is vital to monitor sewage,” a team led by Ying Zhang, an environmental engineer at China’s Fuzhou University, explained in a new academic study.

Part of the problem is that, for all its rapid economic growth over the past generation, China is still a developing country—and its development is uneven. That’s apparent in the sewer system. “The allocation of the pipeline across the whole country is unbalanced,” Ying’s team wrote. Drainage is concentrated in the industrial east at the expense of the rural west, leaving potential gaps in surveillance.

And the pipes that do exist aren’t always well-built. “Because the operation, management and maintenance of the drainage system have not drawn much attention in China, serious problems within the drainage system occur in many cities, such as leakage, overflow and blockages.” Blocked and leaky pipes can corrupt samples.

In light of the challenges, Ying and his coauthors proposed starting small with a partial surveillance system in the biggest cities—and expanding from there, as infrastructure allows. In any event, China needs to do something to get ahead of a possible drop in individual testing.

The pandemic isn’t over. New variants and subvariants are coming. If we’re not going to get tested at the corner pharmacy, then we need someone to monitor our pipes. And this needs to happen all over the world.

Girls attend a class after their school reopened in Kabul on 23 March 2022. The Taliban ordered girls' secondary schools to shut just hours later. (photo: AFP)

Girls attend a class after their school reopened in Kabul on 23 March 2022. The Taliban ordered girls' secondary schools to shut just hours later. (photo: AFP)

Since the Taliban rowed back on its promise to let girls back into the classroom, many Afghan families have been relocating to Iran

It has now been more than eight months since girls in Afghanistan were allowed to attend secondary school.

Initially kept out of the classroom for six months because of the turmoil in the country following the August 2021 US withdrawal and the Taliban's return to power, girls were repeatedly told they would be able to recommence their education at the start of the new school year in March.

But on Wednesday 23 March, as thousands of teenage girls across Afghanistan headed back to school, the Taliban reversed the decision at the last minute. Taliban guards posted outside schools barred their entry, leaving students in tears as they headed back home with books in hand.

“They would look at the girls and say: ‘Go home. Even studying this much should be enough for you all',” recalled Nilofar, 31, a teacher in the western province of Herat.

IS attacks on schools

Sources who spoke to Middle East Eye in the city of Mashhad, northeast Iran, said that enrolment at schools catering for Afghan refugees had increased over the last six weeks, particularly for young girls.

A principal at one such school said that, although education might not be the primary factor pulling people towards Iran, it was a significant one.

“There are major issues with insecurity and the economy," the principal, who did not want to be identified by name, said.

"But if education isn’t the number one reason for these families to come here, it’s definitely high up.”

In recent months, forces claiming allegiance to the Islamic State (IS) group have staged increasingly brazen attacks on schools, education centres and places of worship in several provinces of Afghanistan.

The attacks came despite the Taliban’s repeated claims that once they came to power and the US-led occupation had ended, safety and security would finally return to the nation.

Yet one international organisation has said that nearly 20 million Afghans, or 47 percent of the population, were facing food insecurity due to the economic downturn, drought, aid cutbacks and Washington’s withholding of billions in Afghan assets following the Taliban’s return to power.

Zainab Sajadi, the principal at a non-governmental school for Afghan refugees in Mashhad, told MEE that the enrolment of undocumented students had risen since the Taliban takeover last summer.

“We received hundreds of new students. Our classrooms are completely full,” Sajadi, 41, said.

“We don’t have enough chairs. Some students stand in class, others have to share their chairs.”

Teachers doing extra shifts

Sajadi said the school had started to hold three different shifts of classes a day, with the teachers doing extra lessons voluntarily and without additional pay.

But Sajadi feared that no matter how many steps they took, it would never be enough to meet the outsized demand.

“Even If we keep teaching three shifts a day and continue enrolling students, there will still be thousands of other students who will be unable to attend school,” she told MEE.

Sixty percent of the pupils in Sajadi's school are Afghan girls.

“They are the most intelligent students in our school," she said. "I can see just how much they are starving for education.”

But the journey to Iran for Afghans is fraught with dangers and difficulties.

Paying smugglers to get you across the border can cost upwards of $400 per person, and with bank restrictions on weekly withdrawals in place and millions of people unemployed or on severely reduced wages since the Taliban returned to power, such fees are beyond many Afghans.

Furthermore, Iranian border guards have been accused of shooting dead or torturing Afghan migrants. Tehran was notably one of only two governments (the other being Islamabad) to never suspend the deportation of Afghans as the Taliban was inching closer to Kabul last summer.

For those Afghans who do make it into Iran, there is also the abuse, intimidation and racism they face from both the government and the general Iranian population.

This is why hundreds of Afghan families have relocated to a handful of areas in their own country where teenage girls have been able to return to school.

Increasingly harsh dress codes

One such place is Mazar-i-Sharif, the fourth-largest city in Afghanistan and the capital of the northern province of Balkh.

There, dialogue between the schools and the Taliban has seen girls able to continue their education. However, schools in Balkh and elsewhere have been threatened with closure if they refuse to comply with increasingly harsh dress codes.

“The requirements on hijab are getting tougher day by day,” a teacher in Balkh told Human Rights Watch last month, regarding the mandatory Muslim headscarf.

“They have spies to record and report. If students or teachers don’t follow their strict hijab rules, without any discussion they fire the teachers and expel the students.”

One of the regulations that authorities have enacted is a change to the traditional school uniform of long, black tunics and white headscarves for more Gulf-style coverings that obscure the faces of female students.

A girl in the 11th grade in Mazar told MEE that one of the reasons women in the city have been able to return to school was that they had not allowed themselves to be turned away.

"We kept going back, saying we want to go to school and eventually they had to let us in," the girl, who did not want her name revealed, said.

But she acknowledged that adhering to the increasingly strict dress code set by the Taliban was a condition of being able to go back to school.

"We dress exactly how they want us and only show our eyes," she said.

Sodabah, a student from Mazar, said most of the girls in her school were elated to finally be able to return to their studies on 23 March, but that the joy had been short-lived.

“All our classmates and teachers were so happy until our teacher told us about the school bans in other cities, including Kabul," she said. "Our happiness turned to despair.”

The 19-year-old said she wished all Afghan girls could share in their happiness and return to school, but so far, that has not happened.

Marked increase in numbers

Educators and students in Mazar told MEE that they had seen a marked recent increase in the number of girls in the city’s female high schools arriving from other provinces.

Amina, 17, said her family moved to Mazar from Kabul in early April specifically so that she could continue her education. She said that she was fortunate to have relatives in the city who could help her and her siblings enrol at schools there.

“The Kabul education department rejected our requests for our transcripts so we could transfer to schools in Mazar," she told MEE by phone.

"If my aunt wasn’t a teacher at this school, we wouldn’t have been able to enrol in Mazar.”

Kamila, a teacher at a girls’ high school, said that since April they had been receiving “many students from other provinces”, who wished to continue their studies and that educators in Mazar were hoping to provide these girls “with the chance to continue their educations until they can go back to their provinces and schools".

Kamila said that whether these families are relocating to other provinces or other countries, this was proof that, “Afghan girls and women want education. They want wisdom”.

However, as the Taliban continues to tighten restrictions on the daily lives of Afghan men and women - last week, the group formally announced that all women would be required to cover their faces and only step out of the house when necessary - keeping the doors of the schools open has not been easy.

“We have received instructions from the Balkh education department about Sharia regulations and uniforms,” Kamila said, confirming that the Taliban would make surprise inspections to ensure that their orders were being followed.

Financial burden

However, with many Afghan families struggling to put food on the table amid the economic downturn and the devaluation of the Afghan currency, complying with the new uniform regulations is only adding more financial strain.

A teacher at a girls’ school in Mazar, who did not wish to be identified for security reasons, said the Taliban had not considered the financial burden their new uniform guidelines have placed upon Afghan families at a time when millions of men and women remain unemployed.

“It is very challenging for the students to purchase new uniforms amid an economic crisis. Think about the economic difficulty this places families with three or four girls in,” said the teacher.

Sodabah, the 19-year-old student, agreed.

“The new uniform costs around 800 afghanis [$9], which is more than our weekly groceries, but we didn’t have any other option,” she said.

Her father used to sell t-shirts and jeans at a local market. But she said that since the Taliban came to power, demand for western-style clothing had completely plummeted. As a result, her father had been unable to make enough to support the family and had switched to selling vegetables.

But despite the difficulties, he had worked hard to ensure he could buy new uniforms so his three daughters could continue their education.

“In any situation, I will attend school. I have to study to be successful,” said Sodabah.

A Phillips 66 oil refinery looming over a Wilmington, California neighborhood in 2016 prompted a successful citizen lawsuit in 2018 over benzene emissions. (photo: Rick Loomis/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images)

A Phillips 66 oil refinery looming over a Wilmington, California neighborhood in 2016 prompted a successful citizen lawsuit in 2018 over benzene emissions. (photo: Rick Loomis/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images)

About 6.1 million people in the U.S. live within three miles of an oil refinery, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The EIP report stated that 129 oil refineries were operating in the U.S. last year, 118 of which reported benzene concentrations at or near the refinery site — an area known as the fenceline — to the EPA. Fenceline communities have minority and low-income populations that are almost twice that of the general population, according to the EPA. Difficult to detect leaks from pumps, valves and other sources are responsible for a considerable amount of the excess benzene emissions, The Guardian reported.

If the average yearly level of the highest measured concentrations of benzene at a refinery is over three micrograms per cubic meter — which includes almost half of the oil refineries — the EIP defines that as a “long-term potential health threat,” the report said. Action is required by the EPA if the average is over nine micrograms per cubic meter, which is considered “action level” benzene emission, reported The Guardian.

“If [facilities] can’t get their benzene below the action level, year after year, we really need to see enforcement from the EPA,” said executive director of the Environmental Integrity Project Eric Schaeffer, as The Guardian reported. “You need to start paying penalties when your fence-line levels persist.”

High-level benzene exposure over periods of shorter duration can have negative health effects like dizziness and headaches, as well as respiratory tract and skin irritation, according to the report. Exposure to concentrations of benzene over 29 micrograms per cubic meter over a period of one to 14 days has the potential to increase risks like the weakening of the immune system and other noncancer effects, estimated the U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances Disease Registry (ATSDR). A two-week average benzene concentration of more than 29 micrograms per cubic meter was recorded at least once by fenceline monitors at 22 facilities last year.

Benzene can increase leukemia risk, the report said, and breathing the carcinogen at levels of 0.13 micrograms per cubic meter over a person’s lifetime has the potential to cause as much as one additional case of cancer for every million people exposed, according to EPA estimates. The health risks increase proportionately with the levels of benzene exposure.

Self-reported data showed that last year the highest average net benzene levels were produced by a refinery owned by Marathon Petroleum in Texas City, Texas, reported The Guardian. People of color make up 62 percent of the approximately 37,000 people who live within three miles of the refinery, and 47 percent of the population is low-income.

“People living near these facilities have greater [exposure] to lifetime cancer risk than any other part of the state, yet the regulatory agencies responsible for protecting us continue to approve permits for these facilities,” said Leticia Gutierrez, Government Relations Director of advocacy group Air Alliance Houston, as The Guardian reported.

Spokesperson for the EIP Tom Pelton said that the EPA’s benzene regulations were the result of a lawsuit brought by the EIP, reported Reuters.

“We want the EPA to enforce their own rules,” said Pelton, as Reuters reported.

Special Coverage: Ukraine, A Historic Resistance

READ MORE

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.