How the KGB Hooked Trump

'American Kompromat,' a new book by Craig Unger, gets the lowdown from former Russian and U.S. spies

WAS DONALD TRUMP a Russian asset? Just how compromised was he? And how could such an audacious feat have been accomplished? Based on extensive, exclusive interviews with dozens of high-level sources—Soviets who resigned from the KGB and moved to the United States, former officers and agents in the CIA and FBI, lawyers at white-shoe Washington firms—and an analysis of thousands of pages of FBI investigations, police investigations, and news articles in English, Russian, and Ukrainian, veteran investigative reporter Craig Unger’s American Kompromat unearths the unsettling facts behind the theories of Trump’s compromise by the Kremlin. It’s a story that should rattle anyone who cares about the future of democracy in America.

From American Kompromat: How the KGB Cultivated Donald Trump, and Related Tales of Sex, Greed, Power, and Treachery, by Craig Unger, to be published by Dutton, an imprint of the Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Craig Unger.

There are boundaries in America’s political discourse—or at least there were until Donald Trump’s presidency. There were still taboos: One simply didn’t say that the president of the United States is a Russian asset. And yet according to Bob Woodward’s Rage, no less than former Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats, a Republican, had “deep suspicions” that Putin “had something” on Trump, seeing “no other explanation for his Behavior.” And Coats wasn’t the first highly placed intelligence officer to make such assertions.

In a New York Times op-ed published three months before Trump’s 2016 election, former CIA director Michael Morell wrote, “In the intelligence business, we would say that Mr. Putin had recruited Mr. Trump as an unwitting agent of the Russian Federation.”

In January 2017, just before Donald Trump’s inauguration, Michael Hayden, former head of both the CIA and the National Security Agency, called Trump “a clear and present danger” to America and “a useful idiot,” a term often attributed to Vladimir Lenin that refers to naïve Westerners who could be manipulated for propaganda and other purposes.

In December 2017, the former director of national intelligence James Clapper asserted that Trump was, in effect, an intelligence “asset” serving Russian president Vladimir Putin. And in 2019, former CIA director John Brennan declared that Trump “is wholly in the pocket of Putin,” and went further on “Meet the Press,” adding that he had called Trump’s behavior “treasonous, which is to betray one’s trust and aid and abet the enemy, and I stand very much by that claim.”

Yet somehow, these extraordinary allegations—that the president of the United States is an operative for a hostile foreign power—have not become part of the national conversation. It’s as if the entire country is in denial, even now, after Russian cyber warriors were discovered amplifying claims by Trump and his allies that the election was being “stolen” from them.

So let me try to answer the question: Is Donald Trump a Russian asset?

I believe the answer is yes, and that what happened between Trump and the Russian state is best understood as a series of sequential, and sometimes unrelated, operations that played into each other over more than four decades.

“When people start talking about Trump’s ties to the KGB or Russian intelligence, some are looking for this super sophisticated master plan which was designed decades ago and finally climaxed with Trump’s election as president of the United States,” said Yuri Shvets, a former KGB officer who quit before the fall of the Soviet Union, moved to the United States in1994 and now lives outside Washington, DC. But that’s not how it happened.

According to Shvets, standard Soviet practice was to develop assets and data that might have not have an immediate payoff, but could offer far more value years in the future.

“That’s a big difference between the KGB and some Western HUMINT [human intelligence] agencies,” Shvets told me in an extended series of interviews.

“The KGB is very patient. It can work a case for years. Americans want results yesterday or a maximum today; as a result, they have none. They don’t get that if you round up nine pregnant women, the baby would not be born within a month. Each process must ripen.”

In Trump’s case, it appears that the results took roughly 40 years to ripen. “Then,” Shvets added, “it paid off much, much more than anyone could possibly have imagined.”

Discovering what took place and how—or at least some of it—meant interviewing former officers from the KGB, the CIA and the FBI, and reading hundreds of documents from FBI investigations and countless news stories in English, Russian, Ukrainian, and more. What emerged over the course of this reporting was the story of how a relatively insignificant targeting operation by the KGB’s New York Station, its rezidentura, more than 40 years ago morphed into the greatest intelligence bonanza in history, by putting a Russian asset in the White House as President of the United States.

The operation began after Trump, about 30 years old at the time, acquired the enormous and decrepit Commodore Hotel adjacent to New York City’s Grand Central Terminal in 1976. It has been widely reported over the years how Trump, who paid only $1 for the option to buy the hotel, made an immense fortune by converting it into the Grand Hyatt New York in 1980.

Despite all we know about the deal, one obscure, seemingly mundane detail in the development of the Grand Hyatt may be key to unraveling Donald Trump’s ties to Russian intelligence. The incident in question is the reported purchase by Trump of hundreds of television sets for the new hotel from Semyon “Sam” Kislin, a Ukrainian Jew who co-owned a small electronics store in New York.

Inside Wiring

At the time, Manhattan was awash with cut-rate electronics stores selling every gadget imaginable. But Kislin’s store, Joy-Lud, on lower Fifth Avenue near the Flatiron Building, proclaimed its distinctiveness. “We speak Russian,” a sign read. As a result, it carved out a special niche among Soviet diplomats, KGB officers, and Politburo members living in or passing through New York City.

The reason for Joy-Lud’s popularity among the Soviets wasn’t only that they spoke Russian. Standard American TV didn’t work in the Soviet Union, which used different technical standards to broadcast. “You couldn't buy a TV set in a regular American store which would work in Moscow,” says Shvets, who was familiar with the Joy-Lud when he served as a major in the KGB in Washington in the mid-1980s. “The only place was Kislin's.” So Soviets living in New York who wanted to buy a TV that would work when they took it back home all patronized the store.

The store—its walls covered with pictures of Soviet singers, athletes and cosmonauts—won over high-powered customers such as Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze, Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko; KGB counterintelligence chief and, subsequently, Prime Minister Yevgeny Primakov, and others.

But one client didn’t quite fit in with the rest—Donald Trump. Many details about Trump’s relationship with Kislin and purchase of TVs for the Grand Hyatt are not known. In fact, Kislin himself seems to be the only source on record regarding the transaction, having told Bloomberg Businessweek, in 2017, that he “had sold Trump about 200 televisions on credit.” Trump, who later developed a reputation for stiffing vendors, made sure he paid Kislin on time. “I gave [Trump] 30 days, and in exactly 30 days he paid me back,” Kislin said. “He never gave me any trouble.”

But there was more to it than that.

A Burnt Out Case

I first met Shvets in October 2019 at a steakhouse in Tysons Corner, Virginia, near his home, about 10 miles outside Washington. Clad in a sport jacket, jeans and no tie, at 67, he could still pass for a journalist, which is exactly what he did back in the mid-1980s, when he was a Washington correspondent for Tass, the Soviet news agency.

But that was merely a cover for his real career working in counterintelligence for the KGB. He was in Washington to recruit American spies.

A 1980 graduate of Patrice Lumumba People’s Friendship University in Moscow, Shvets did post-graduate work at the Academy of Foreign Intelligence, where he and classmate Vladimir Putin were taught the secrets of the espionage trade.

Shvets had joined the KGB for a very simple reason. “It was the best job a man could have in the Soviet Union,” he told me. The pay was good—by Soviet standards, at least—and the perks were fabulous. In a country whose national discourse was a tightly controlled creation forged by propaganda and state censorship, Yuri had access to information that ordinary Soviet citizens couldn’t get—The Washington Post, The NewYork Times, American TV, and the BBC—not to mention the secrets men die for.

When Shvets moved to Washington in 1985, ostensibly as a Tass reporter, he was in fact serving in the KGB’s First Chief Directorate, the counterintelligence department. Within five years, however, Shvets became deeply disillusioned with the KGB, and resigned. In the mid-1990s he published a book about his experience with the KGB, Washington Station, and was granted political asylum in the United States, eventually settling in suburban Virginia, where we first met.

After being granted asylum, Shvetz occasionally used his knowledge and contacts to work against the Soviet regime. He was a friend of former FSB officer Alexander Litvinenko, and had worked closely with him in 2005 helping him assemble a dossier on senior Kremlin officials that alleged, among other charges, that Vladimir Putin had provided protection to the Barsukov and Tambov crime gangs when he was deputy mayor of St. Petersburg. In 2006, Litvinenko was poisoned by radioactive Polonium 210, in what was likely a retaliatory state sponsored assassination directed by Putin.

Shvets also worked for oligarch Boris Berezovsky, the multibillionaire who once owned Russia Channel One, Russia’s main television channel, but broke with Putin and won asylum in London. In 2013, Berezovsky was found dead at his home near Ascot with a ligature around his neck. His death was said to be consistent with hanging but because of “contradictory” evidence, coroner Peter Bedford returned an open verdict; he could not say beyond reasonable doubt whether Berezovsky committed suicide or was murdered.

Today, Shvets plies his craft in the world of corporate intelligence, providing research and strategic intelligence on the former Soviet Union to American and Western European corporations. Long steeped in the particulars of KGB tradecraft, he has had a front row seat at the birth of post-Soviet Russia as a Mafia state. His expertise is valuable to those doing business in Eastern Europe and Russia.

Shvets’s tenure with the KGB in Washington happened to take place while the spy agency began to keep an eye on Donald Trump in the 1980s through the New York Station, the sister outpost to the Washington Station, where Shvets was posted.

According to Shvets, the KGB got its foot in the door with Trump thanks to the forementioned owner of the Joy-Lud electronics store, Semyon Kislin, a wealthy Sovietémigré from Odessa, who left the Ukrainian seaport in 1972. At the time Kislin emigrated, Shvets said, the Odessa field office of the KGB had a special “Jewish department” to oversee the “recruitment” of Jews from Odessa who wanted to leave the Soviet Union.

“It was almost an ultimatum,” Shvets told me. “If you wanted to immigrate, you had to sign the pledge to cooperate with the KGB. And Kislin was one of those recruited.”

Soviet Front

Many émigrés forgot about their promises to the KGB as soon as they got to the United States, but not Kislin. Before long, he and his partner, Soviet émigré Tamir Sapir (neé Temur Sepiashvili), had set up Joy-Lud to sell goods to fellow Soviets. That was Kislin’s way of cooperating: Joy-Lud Electronics was a KGB front.

The Russians had different categories for agents who could be tasked to perform specific operations as handlers, recruiters, and penetration agents. Kislin's job, according to Shvets, was simple. "He was a spotter agent. His task was to look for potential targets for KGB recruitment.”

And, according to Shvets, Kislin had spotted Donald Trump.

There were a number of anomalies in Trump’s deal to buy 200 TV sets for The Grand Hyatt from Kislin. Why would the blue-chip Hyatt Corporation get television sets from a small Soviet outfit instead of a reliable wholesaler? The answer, according to Shvets, is that Kislin probably offered the TV sets to Trump at spectacularly low prices.

By doing so, the KGB, via Kislin, got its foot in the door and could see if the flashy,connected real estate mogul was worth the effort to recruit. Once contact with Trump had been reported to the KGB, the process began. The KGB could not have foreseen Trump’s ascent in politics, of course, but simply making a sale to Trump got the ball rolling.

Shvets says that the KGB operative assigned to keep in touch with Trump (who would not have known he was being cultivated as a potential asset) would almost certainly have been a Soviet operative at the UN, and would have reached out to Trump at a frequency of roughly once a month. “That was standard procedure,” he told me, “It was so standard it was like a cop asking you for your driver’s license and registration after stopping your car for a traffic violation.”

Over the next four decades, starting in the 1980s, as Trump was introduced to more and more Soviet businessmen and Soviet officials, buying apartments in Trump buildings became a tried and true way for the so-called Russian Mafia to launder money. Then starting in the early 2000’s, Trump partnered with wealthy Soviet émigrés such as Tamir Sapir, who happened to have been Semyon Kislin’s partner, and Kazakhstan-born businessman Tevfik Arif in condo franchising projects through the Bayrock Group, a real estate development company located in Trump Tower. All the while, the file that the KGB and its successors kept on Trump would be updated and shared.

In a 1999 Center for Public Integrity article, Pulitzer Prize winner Knut Royce explained how Semyon Kislin accumulated his wealth in the United States. Royce cited a 1994 FBI file characterizing Kislin as a "member/associate" of the mob organization headed by Vyacheslav Ivankov, the "godfather of Russian organized crime in the United States.” By then, Kislin had started Trans-Commodities, a firm which, according to the FBI report, “is known to have laundered millions of dollars from Russia to New York." It also noted that Kislin had cosponsored a visa for Anton Malevskiy, a contract killer who headed one of Russia’s most bloodthirsty Mafia families.

By this time, the former Soviet Union had been dissolved and Russia had emerged as the new wild, wild West, with former mobsters jockeying for control of steel, aluminum, oil and other commodities. Kislin’s firm, Trans-Commodities, Inc., and Malevskiy were also allegedly tied to oligarch Mikhail Chernoy, who was said to be among the roughest players in the bloody and brutal Aluminum Wars that pitted billionaire oligarchs against each other and were marked by embezzlement, money laundering and murder.

For all that, Kislin was never charged with any crime, and in 1999, denied any ties to the Russian mob. He has also denied charges that Trans-Commodities laundered money for Russian organized crime.

Kislin declined to be interviewed for this article, but his attorney, Jeffrey Dannenberg, said that there were no such FBI files and that the Center for Public Integrity had disavowed Knute Royce’s article long ago. “Not only is the article wrong, but many years ago I spoke with the head of the Center for Public Integrity and told him it was wrong,” Dannenberg told me. “They withdrew the article—which was pretty extraordinary for them. They withdrew it.”

Turns out that was not true. Mei Fong, Director of Communications and Strategy at the Center, told me, “We haven’t disavowed anything. The article is still on our website.” And indeed, it can be found here.) Later, as if to insulate himself from allegations that he was tied to the Russian Mafia, Kislin became a donor to Rudy Giuliani’s successful mayoral campaigns in New York in 1993 and 1997, and raised millions more for him at fundraising events.1 In return, Giuliani gave Kislin a plum patronage job on the New York City Economic Development Corporation in 1996.

Who Do You Trust?

After the KGB had put together about 10 reports on Trump, Shvets says, they would have assessed whether he could be recruited in either of two capacities: “Capacity number one—as a trusted contact. Capacity number two, which is more ambitious—as an agent. You want to know if this guy can be cultivated to the point where he can be brought to cooperate.”

To that end, I asked Shvets and Glenn Carle, a former national intelligence officer with the CIA, how an agent might handle a new asset who had just been recruited, and their answers were somewhat similar. “Be good to them,” said Shvets. “Give them what they want. Have a good relationship.”

As for Carle, he explained, “I think we [as handlers] are dream makers. We fulfill the dreams of our targets. Whatever you lack, we can provide. If you need psychological soothing because you are under stress, come cry on my shoulder. If you need someone to talk to, I'm a listener. If you want a bowling buddy, I really like ten pin. And so forth.”

It’s widely known that Trump—profoundly insecure, highly suggestible, and exceptionally susceptible to flattery—was anxious to acquire intellectual validation. In In that regard, the KGB would have been delighted to humor him.

“It was like he was created to be recruited,” said Shvets. “Everybody has weaknesses. But with Trump, it wasn’t just weakness. Everything was excessive. His vanity—excessive. Narcissism—excessive. Greed—excessive. Ignorance—excessive.”

By the mid-1980s, Trump had become convinced he knew as much about nuclear, as he put it, as anyone in the country. He told reporters at The New York Times and Washington Post he was such nuclear arms virtuoso, he should be negotiating nuclear proliferation talks. According to Shvets, that ongoing fixation provided a great opening for the KGB.

“They’d say, ‘You have great potential. Someday you’ll be a big politician. You have such an unorthodox approach! What great ideas! Such people as you should lead the United States. And then we together can change the world. Maybe we should just be friends and forget about hostilities. There is a growing admiration in Kremlin about your successes as a businessman and we are looking for new idea opportunities and I believe that there is an opportunity for your business in Russia. We want to explain our position on different issues and here they are.’

“Trump may be taking notes, or he might be given a printout,” Shvets continued. “The KGB called them ‘teases,’ but you might call them sound bites or Active Measure instructions.”

All this was taking place during an extraordinary period in the spy game, a period during which the Soviet Mission to the United Nations was said to be harboring a huge nest of operatives in New York. In addition to the Soviet Mission, the KGB planted scores of intelligence officers inside the United Nations Secretariat, the executive arm of the UN. Typically, specific jobs in the Secretariat were overseen by Soviet representatives who ensured that they went to KGB operatives.

Pulp Fiction

The “official” Russian account of how Trump first came to Moscow in 1987 appeared on the website of the daily newspaper Moskovsky Komsomolets (MK), a Moscow-based daily newspaper with a circulation of nearly one million, at 6:54 pm on November 9, 2016—nine hours and 20 minutes after Donald Trump was declared the 45th president of the United States.

It came in the form of an interview with Natalia Dubinina, the daughter of Yuri Dubinin, who, in the 1980s, had served as a Soviet ambassador, first to the United Nations and then the United States. With her father, Dubinina was among the first Soviet officials to meet Trump in New York, in March 1986. According to her account, while she was working at the UN, her father arrived in New York, for the first time in his life, to start work at the UN. She picked him up, and gave him a quick tour of Manhattan. Their first stop was Trump Tower, which her father saw as an “unprecedented architectural masterpiece.”

“This building was the first thing my father saw in New York,” Dubinina told MK. “He had never seen anything like it, it was a revolution in architecture and Approach.” In fact, Dubinin was so amazed, his daughter said, that he instantly decided he had to meet the building’s creator, and, with her in tow, went straight up to Trump’soffice. “My father was fluent in English,” Natalia said, “and when he told Trump that thefirst thing he saw in New York was Trump Tower, Trump immediately melted. He is an emotional person, somewhat impulsive. He needs recognition and, of course, he likes when he gets it. My father’s visit had an effect on him like honey on a bee.”

Between the Lines

To most readers, Dubinina’s account may seem relatively anodyne, but in fact it was full inaccuracies, some of which appear to be intentional, and which, taken together, raise the question of whether there was another agenda behind the article’s publication.

According to the Russian newsweekly Argumenty i Fakty (Argument and Facts), at the time Dubinina first met Trump, she worked for the Soviets in the UN’s’ Dag Hammarskjöld Library. That little known fact about her is extraordinary when one considers the context. According to a report by U.S. Senate Select Intelligence Committee, Dubinina’s highly-paid and sought after position was really a cover for KGB operatives who used it to disseminate Soviet disinformation and implement covert operations.

All of which suggested that Dubinina was a spy. Moreover, as The Guardian reported in 2006, MK, which published Dubinina’s interview, has a history of aiding both Soviet and Russian intelligence with active measures, including the publication of disinformation suggesting that the polonium poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko had been the work of Americans. All of this was important, Shvets told me, because it shows “Natalia [Dubinina] was a KGB officer and her story in MK was an attempt to cover the true nature of the KGB’s contact with Trump.” Dubinina did not respond to multiple attempts to reach her for this article.

“It was a ‘hello ’from the Russian human intelligence [HUMINT] to DT [Trump], their man at the White House, and it was an urgent attempt to conceal the details of his initial contacts with the KGB foreign intelligence,” Shvets theorized.

“Dubinina had kept silent from 1986 until the day after Trump's election,” he added. “And suddenly, she comes out with a big interview published the very same day. So, it had to be prepared in advance.”

Assigning, writing, editing, and publishing a story that fast just doesn’t happen inmost major dailies, unless someone important is around to grease the wheels. In this case, Shvets told me, it was the successors of the Soviet KGB, the FSB, the Russian Federation’s Federal Security Service.

“I know firsthand that Moskovsky Komsomolets was used for active measures by the Russian intelligence community,” he said. “I know their modus operandi, because I was trained by the same textbooks as Putin and those who are running Russian intelligence services.”

The main point behind the Dubinina interview may have been to conceal the fact that Trump’s first contact with Russia had been through KGB intelligence. “This is crucial,” said Shvets.

“If it was Russian HUMINT that established the initial contact, all subsequent contacts with Russian representatives had to be ultimately controlled by the KGB/FSB/SVR and were part of one big intelligence operation, which significantly contributed to his election as the US President in 2016.”

“And number two, the KGB believed that Trump would read this article or a translation of this article. It was like a reminder saying, ‘Guys, we remember. And you see, we are lying... We are camouflaging our relationship, but we remember everything.’”

Red Letter

In January, 1987, Yuri Dubinin, who after a brief two month term as ambassador to the UN became the chief Soviet envoy to Washington, wrote Trump a letter.

“It was an established procedure for the KGB stations in the US to use Ambassador Dubinin to pass on invitations to Americans to visit Moscow,” says Shvets. “Usually, those trips were used for ‘deep development,’ recruitment, or meeting with the KGB handlers.” The letter also expressed the Russian government’s interest in Trump constructing a Moscow replica of Trump Tower, the building Dubinin had so admired. After all, that was what had gotten Trump so excited.

Trump’s trip began on July 4, 1987. The Guardian’s Luke Harding wrote about it in some detail in his 2017 book, Collusion: Secret Meetings, Dirty Money, and How Russia Helped Donald Trump Win. He said it resembled “a classic cultivation exercise which would have had the KGB’s full support.”

Since then, new details have come to light that make it even harder to believe that Trump’s visit was anything other than a means of activating his relationship with the KGB.

First, according to Shvets, Dubinin’s letter inviting Trump had been written at the behest of General Ivan Gromakov in the First Chief Directorate’s rezidentura in Washington. Gromakov, who died in 2009, was a high-level official who attended meetings with then-KGB Chairman Viktor Chebrikov, his successor Vladimir Kryuchkov, and other top officials in the KGB.

By all accounts, Trump was thrilled with the invitation. But there is no evidence that he was aware of General Gromakov’s heretofore unreported role in extending it. Nor is there reason to believe that he was aware of the widely known fact that Goscomintourist (better known as Intourist), the Soviet agency that arranged his trip, was a front for the KGB.

“There's no way they would overlook a guy like Trump,” former CIA station chief in Moscow Rolf Mowatt-Larssen told me. “The KGB would be all over Trump. Any trip he goes to Moscow, it’s going to be a full court press.”

Before Trump was brought to Moscow, Shvets says, the KGB in New York City would have conducted a “preliminary evaluation” of his personality based on intelligence from their human assets who had penetrated his circle. That information could have come from a yet-to-be identified handler, or, perhaps, a number of wealthy Soviets who owned and lived in Trump Tower and other Trump properties, and had links to the KGB. After that would have come the professional evaluation, for which Trump would have had to meet with an experienced operative at least three or more times.

“In terms of his personality,” Shvets added, “the guy is not a complicated cookie, his most important characteristics being low intellect coupled with hyper inflated vanity. This combination makes a dream for an experienced recruiter.”

Traveling to Moscow with his then-wife Ivana, Trump stayed at the National Hotel, where he was almost certainly under constant observation. During the trip, Trump saw half a dozen potential building sites for Moscow’s Trump Tower, none of which were as close to the Kremlin as he had hoped.

Shvets, who had been recalled to Yasenovo, the First Directorate’s highly guarded headquarters in a forest southwest of Moscow, had no contact with the Trump party when it arrived. But he was close enough to the operations underway at New York Station to understand their shared protocols. “The New York desk where Natalia Dubinina worked was located just two doors away from the room where I worked. On a regular basis, we had business meetings where we were discussing professional matters. We didn't discuss specific cases in this giant meeting, but you could have an understanding on generally what's going on.”

And that was to flatter Trump into believing that not only was he a budding statesman, but that he had a lucrative real estate future in Russia.

There was another key aspect to Trump’s trip to Moscow that has been widely overlooked by the press: As soon as he returned to New York, Donald Trump decided to make a highly improbable, quixotic, and, as it turned out, short-lived run for the presidency in the 1988 primaries against George H. W. Bush, then the incumbent vice president. To help put his campaign on the map, Trump decided to promote his newlyacquired foreign policy expertise that he’d learned in Moscow earlier that year.

Shvetz was still in Yasenevo, when, on an unspecified date in September 1987, a cable came across his desk that today appears far, far more significant than it did at the time. “I remember receiving a cable that was an assessment of activities in general terms of KGB intelligence stations in the United States,” Shvets told me. The cable came from Service A, sometimes known as the Active Measures division of the First Chief Directorate in which Shvets worked. Active Measures is a term used by Soviet and Russian security services for conducting political warfare via disinformation, propaganda, counterfeiting, and other means.

At the time, Service A consisted of about 120 officers who focused on three main themes: creating material that would discredit all aspects of American foreign policy, promoting conflict between the United States and its NATO allies, and supporting Western peace movements.

Shvets recalls receiving a cable celebrating the work of a new asset acquired by the KGB. The point of the cable, Shvets said, was not to call attention to the identity of the new recruit, but to show off examples of successful craftsmanship in recruitment and in analytical work.

In this case, the new recruit had executed a successful Active Measure operation by voicing KGB talking points in full-page ads bought in three major American newspapers: The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Boston Globe. The ads called for the United States to stop spending money to defend Japan and the Persian Gulf.

The ads, which originally appeared on September 1, 1987, ran under the headline, “There’s nothing wrong with America’s Foreign Defense Policy that a little backbone can’t cure,” and, for all practical purposes, called for the dismantling of the postwar Western Alliance. The ads took the form of an open letter to the American people “on why America should stop paying to defend countries that can afford to defend Themselves.”

“The world is laughing at America’s politicians as we protect ships we don’t own, carrying oil we don’t need, destined for allies who won’t help,” the ad said. “It’s time for us to end our vast deficits by making Japan, and others who can afford it, pay.”

The positions put forth were and remain quite extraordinary. Oil in the Persian Gulf was of “marginal significance,” the ad said.

Right. Of course. This, just a few years after the Carter Doctrine had proclaimed that the United States would use military force if necessary to defend its national interests—aka oil—in the Persian Gulf. And just a few years before the 1990-1991 Gulf War, which was entirely about control of the viscous amber fluid that powers the world.

Abandon Japan? Sure. Why bother with one of the most pro-American nations in the world? Provoking distrust between the US and Japan in political, economic, and military circles would only help the Soviets.

So it was indeed a triumph for the KGB to manipulate an American into attacking foundational elements of American foreign policy, and doing it with the KGB’s strategic talking points.

As for the man behind the ad, he was a flashy 41-year-old real estate mogul from New York.

At the time, Shvets hadn’t even heard of him. Even though the unidentified asset had no access to classified material, the KGB decided he could still be used to channel active measures to influential people in the U.S. That was important. And, according to Shvets, “The ad was assessed by the Active Measures Directorate as one of the most successful KGB operations of that time. It was a big thing—to have three major American newspapers publish KGB soundbites.”

The day after the ad appeared, a New York Times article suggested the man behind it might enter the 1988 Republican presidential primaries against incumbent Vice-President George H. W. Bush. According to Shvets, earlier that summer the KGB had likely proposed to their new recruit that he run for president. Whether that was merely a whimsical suggestion or not, the new asset went so far as to set up a fall appearance in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, an obligatory campaign ritual.

As it happened, the candidate soon dropped out of the GOP primaries. But by then, the fact that he’d already executed his first active measure for the KGB merited a minor celebration for Shvetz and his colleagues 4,700 miles away from New York in Yasenevo.

Ordinarily, the name of the new asset would not appear on such a cable. “In handling assets, security always comes first when it comes to agents,” Shvets said.

“There’s always a correlation between objectives and risks,” he added. “You can’t afford to lose a very important asset in intelligence work. If he had been seen as an important asset, this cable wouldn’t have been sent at all.” There would not have been a name in it. But in this case, the ad itself had already been signed by the new asset.

And his name was Donald J. Trump.

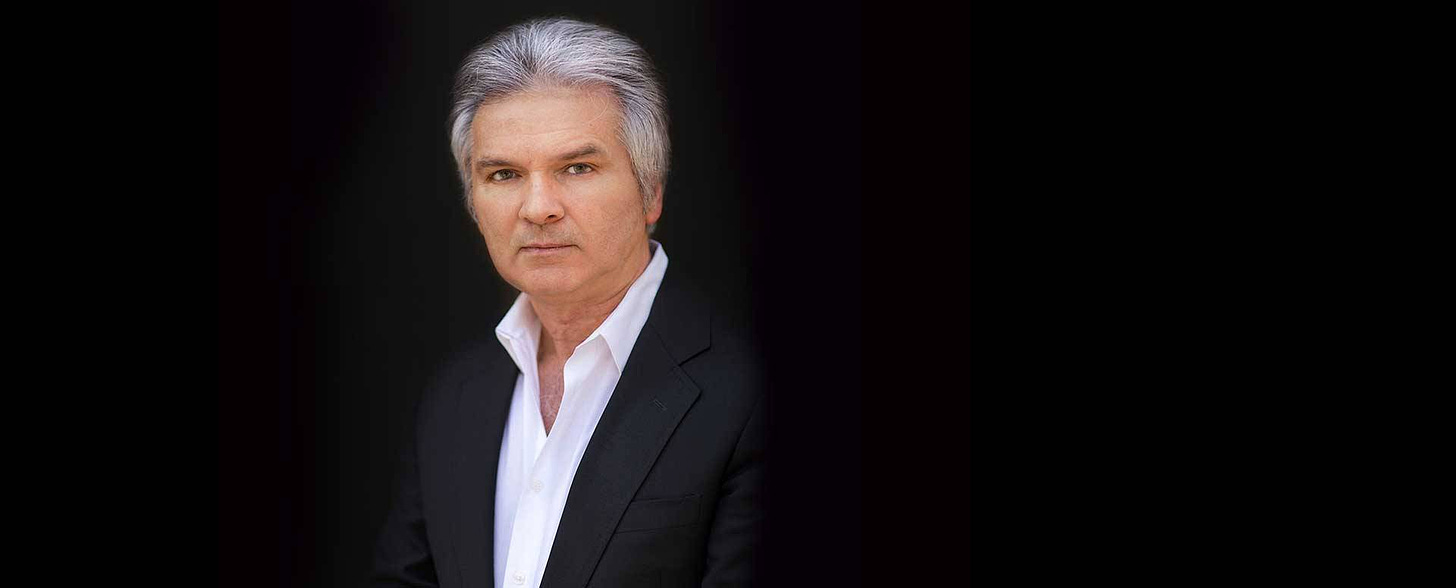

Craig Unger is the author of seven books, including the New York Times bestsellers House of Bush, House of Saud, and House of Trump, House of Putin. For 15 years he was a contributing editor for Vanity Fair, where he covered national security, the Middle East, and other political issues. A frequent analyst on MSNBC and other broadcast outlets, he was a longtime staffer at New York Magazine, has served as editor-in-chief of Boston magazine, and has contributed to Esquire, The New Yorker, and many other publications. He has written about the Trump-Russia scandal for The New Republic, Vanity Fair, and The Washington Post. He is a graduate of Harvard University and lives in Brooklyn, New York.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.