Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Why did it take a murderous war on Ukraine for Germany to wake up to the threat from Russia?

Nowhere has this process of revisiting the past in search of the right decisions for the future been more fraught since the Russian invasion than in Germany. Over the past 16 months, the country has ended its heavy dependence on Russian oil and gas, abandoned its reluctance to send weapons to the war zone, and turned into one of Ukraine’s most important military and financial backers after the US. Most Germans now support this policy shift – or Zeitenwende (turning point) as Chancellor Olaf Scholz terms it – but public debate about the future of Germany’s security policy has not stopped. And arguments about history play a prominent part.

The brutality of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, Putin’s blatant disregard for international law, and his explicit threats against the west have compelled Germany’s political and intellectual elites to reconsider long-held and widespread assumptions about the lessons for Germany of the second world war and the cold war. The significance of this change should not be underestimated, nor should anyone be surprised that it remains precarious and contested.

In the three decades after the end of the cold war, Germany’s policy in central and eastern Europe was heavily influenced by a reading of history that put Russia at the centre of German thinking about the region, while neglecting the smaller countries in its neighbourhood. This Moscow-centric bias reflected the extent of Russia’s power, but was also, at least in part, due to Germany’s recognition of its historic responsibility for the second world war, which on its eastern front, was a brutal war of annihilation. More than 25 million Soviet soldiers and civilians died, and they play an important role in Germany’s culture of remembrance.

The readiness to face up to its historical responsibility for the second world war, and the focus on reconciliation and remembrance, are hard-won achievements of German democracy that should not be taken lightly. What remained problematic after the cold war, however, was a widespread German tendency to equate Russia with the Soviet Union, and for politicians to argue that Nazi Germany’s crimes imposed a special German obligation to seek dialogue with Russia, without extending the same consideration to the other former states of the Soviet Union, such as Ukraine. After all, roughly 8 million of the Soviet victims of the second world war were Ukrainians, and Ukrainian territory was the site of brutal battles and unspeakable crimes, particularly against the Jewish population. There has been no lack of nuanced historical research on this, but it is only now, after Putin’s invasion, that the important distinction between Russia and the Soviet Union is being more widely appreciated in Germany’s public discourse.

The emphasis on the terrible price of war with the Soviet Union between 1941 and 1945 also resulted in a lack of German sensitivity about German-Russian collusion from 1939 to 1941 and its long-term consequences. Before Hitler decided to attack the Soviet Union two years later, he and Stalin agreed in the Molotov-Ribbentrop nonaggression pact of 1939 to divide central and eastern Europe into Nazi and Soviet spheres of influence. The countries that paid the price for this in brutal occupation, deportation and displacement were as deserving of Germany’s special consideration after the fall of the iron curtain as Russia. The memory of this collusion has profoundly shaped central and eastern European thinking about both countries to this day, especially in Poland and the Baltic states. However, in the two decades leading up to the war in Ukraine, their point of view mattered less to Berlin than Moscow’s.

Another defining chapter in Germany’s history that is now under re-examination is the famous “Ostpolitik” of the cold war chancellor Willy Brandt. This remained central to Germany’s thinking about Russia until 24 February 2022. In the late 1960s and early 1970s Brandt and his Social Democratic party (SPD) pursued a policy of dialogue with the Soviet Union in the hope of stabilising West Germany’s relationship with eastern Europe. His belief, 25 years after the end of the second world war, was that a strategy of “change through rapprochement” would reduce east-west tensions and possibly even help change the Soviet Union from within. Rapprochement included trade with the Soviet Union.

One does not have to be a member of the SPD to be proud of Brandt, albeit for a different reason. He is most famous for kneeling down in front of the memorial to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1970, an unprecedented and hugely important gesture of shame and repentance for Germany’s war crimes and the Holocaust. It is also important to stress that Brandt’s pursuit of dialogue with the Soviet Union was from a position of strength. West German defence spending was at 3% of GDP a year during his time as chancellor, vastly higher even than what is envisaged in Germany’s first national security strategy, published on 14 June.

But Germany’s Russia policy lost its way after the cold war, as large parts of the SPD maintained a naive attachment to the principle of “change through trade” and remembered or reinterpreted Brandt’s policy in a selective way. Decades after Brandt, Gerhard Schröder, another SPD chancellor, is accused of turning this cherished and widely idealised tradition into a convenient excuse for prioritising German business interests in Russia over the geopolitical concerns of Germany’s central and eastern European Nato and EU allies. In their recent book, The Moscow Connection, Reinhard Bingener and Markus Wehner present a forensic and damning account of how Putin’s Russia spent decades courting both German political elites and public opinion, showing that the debate about Germany’s long-held Russia-centric assumptions is essential.

Germany’s support for Ukraine since the invasion constitutes a clear break with its Russia policy. The Scholz government has burned its bridges with Putin and abandoned longstanding principles that had resonated with many Germans until February 2022. This was not easy. But the crucial question is not just whether the Zeitenwende Scholz promised is really happening, but why it took a murderous war in Ukraine for it to begin.

Germany changed its mind about Russia, but not until it was too late. The necessary and agonising interrogation of why is only just beginning. A change, which from the German government’s point of view feels significant, even drastic, was long overdue and far too slow in the eyes of many of its allies. The criticism is valid. It is the urgency of Ukraine’s plight that should set the pace of Germany’s response to this catastrophic crisis of European security – not its own soul-searching.

READ MORE  Juneteenth. (image: James W. Watts/Henry Walker Herrick/Library Company of Philadelphia/Reuters/Michael Noble Jr.)

Juneteenth. (image: James W. Watts/Henry Walker Herrick/Library Company of Philadelphia/Reuters/Michael Noble Jr.)

Freedom and justice have always been delayed for Black Americans.

On Thursday’s episode of What Next, I spoke to Adam Serwer, a politics writer at the Atlantic, about the history and meaning of Juneteenth and what the recent embrace of the holiday says about racial progress in America. This transcript has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Mary Harris: What is the story of Juneteenth? How did it become so prominent nationally?

Adam Serwer: So the Emancipation Proclamation frees the slaves in the Confederacy. A lot of Confederate slave owners freak out because a lot of slaves are running towards Union lines. They want to defect, they want to join the Union Army, they want to help out however they can, or they just want to be free. And as a result, a lot of slave owners pack up and head to Texas, and Texas is one of the last states to have slavery really abolished. That comes with General Order No. 3, which is issued by Union Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger on June 19, 1865.

And we should say the Emancipation Proclamation was 1863.

Right. So this is years after technically all the slaves in the Confederacy were supposed to be free. Part of the celebration comes from the fact that a lot of the enslaved folks in Texas, the emancipated, were moved there to avoid emancipation. So there is a delayed celebration but also a sense that this is finally happening for them. That probably explains why this celebration became so prominent both in the state and why Black Americans and other states have latched onto it as the predominant celebration of emancipation, even though it comes years after the Emancipation Proclamation was actually issued.

I’ve heard Juneteenth described as a particularly apt holiday to commemorate Black liberation because it represents the way freedom and justice in the United States has always been delayed for Black people. And I thought that was just such an interesting way to put it, where it was an acknowledgment that we did declare that this was illegal, but we didn’t actually make it happen for years.

Yeah. In a way it’s a metaphor, because the declaration of progress happens long before actual progress is achieved.

And awareness around Juneteenth has tended to expand with the growth of major Black liberation movements in the United States—Reconstruction, the civil rights era.

If you look at it that way, it’s not surprising that there’s been a resurgence of the effort to recognize Juneteenth as a national holiday, because we’re going through one of those moments now where there is a lot of political momentum for efforts to dismantle systemic discrimination. At least for the moment. The history of these things is that these moments only last for so long. And particularly when efforts to remedy discrimination start to touch material concerns, you tend to see that tide of public support recede, particularly from white Americans.

As Martin Luther King starts pivoting towards concerns that are not just about political rights but about economic concerns, you can see that resistance start to grow. There’s a lot of resistance to the Fair Housing Act and to the integration of neighborhoods as well as a great deal of resistance to the integration of schools. When civil rights movements shift from political rights to more material concerns about wealth and disparities and stuff like that, you can see a lot of resistance from people who were previously sympathetic. And I think that’s probably going to happen here, if history is any guide. It’s one thing to say the police shouldn’t kill people, they shouldn’t discriminate. For people who are very conservative on issues of race, that seems like a very reasonable demand. But when you start talking about redistribution of wealth, people tend to start becoming a lot more skeptical, because they feel like they’re going to have things that belong to them taken from them.

This year, with so many more people committing to celebrating Juneteenth, I’m struck by how different people have said different things about what the holiday is for. Some have said it’s for volunteering and learning about racism, and other people have said it’s more about being with family. I wonder how you think the holiday should be observed.

I feel like there is an impulse to want to be solemn about it, but that’s not the way that I’ve experienced it for most of my life. I think it’s important that people remember why it exists, certainly. But I’m not against people celebrating it the way we celebrate something like Memorial Day or the Fourth of July, where the historical significance of the holiday is understood by the people who are celebrating it but people are also having a very good time.

I wonder if you worry at all about whether widespread acceptance of Juneteenth might dilute its meaning.

I’m not worried about it. As long as people remember what it’s for, I don’t have a concern. I mean, even Memorial Day was initially a Black American celebration at the end of the Civil War. As long as people have a sense of historical memory for what Juneteenth is, why it’s being celebrated, why emancipation came to Texas so late, and what that means for racial progress in the country, I don’t really have a problem with it.

Most states already acknowledge Juneteenth. But this year you have Virginia declaring its intent to make it a holiday, and all of these companies saying that they will acknowledge this day, from J.C. Penney to Twitter to Spotify to my company, Slate.

There’s a lot of upside to recognizing Juneteenth for companies, and not a lot of downside. The upside is that you get to say, We’re recognizing this celebration of emancipation as an important thing. If you’re a corporation, you get to sell people Juneteenth swag of some kind. You get to sell beer for Juneteenth. You get to sell hot dogs for Juneteenth. You get to sell Juneteenth T-shirts, whatever. But you also don’t give up very much. It’s not like you’re sacrificing a lot by recognizing this thing as a holiday, and you may get a lot of gain out of it in the sense that people will see you as someone who is politically and culturally welcoming in a way that may get you more customers. So on the one hand, it’s a nice symbolic progress. But on the other hand, it doesn’t require a lot of sacrifice, and there’s a lot of gain to be had from doing it.

We’re still in a capitalist society.

I don’t think corporations, from supermarkets to clothing stores to anything else, are going to be that upset if there’s another July Fourth in June.

Right. One more reason to barbecue. One more reason to come buy fireworks.

Exactly.

This low-cost way for a company to acknowledge the moment—you see that in some of the movement around Juneteenth. A couple of places that have decided to celebrate the holiday have had little scandals of their own—the NFL, the New York Times. And I wonder if you worry that for some of these companies, declaring a holiday is where the work begins and ends.

Well, I think it would be very hard to find a corporation in the United States that hasn’t had to deal with some kind of racial controversy at one point or another. I think the important thing is to remember that observing Juneteenth is not a way to, as President Barack Obama once put it, “purchase racial reconciliation on the cheap.” It’s not a way to inoculate yourself against charges of racism or abandon whatever commitment you might have to treating your employees equally and with respect. And people shouldn’t see it that way. But to the extent that the holiday increases the recognition of the significance of slavery and emancipation in American history, then I think that it’s probably a good thing.

A few weeks back, Alexis Ohanian—one of the founders of Reddit, who’s also the husband of Serena Williams—decided to step down from the board of his company and encourage the board to select a Black person to replace him. I was thinking about that in the context of all this. I was like, wow, that’s a pretty powerful action. If a company really wants to respond to the moment, is there something it should be doing?

If you’re recognizing Juneteenth but you’re not involving Black people in your company, by hiring them or by putting them in leadership positions or paying them a fair salary, then your commitment to racial justice is obviously bullshit. And to the extent that you have Black employees at your company who see themselves being mistreated or not being considered for leadership positions or being paid less than everybody else, those employees are going to recognize that for what it is and not as a genuine commitment to any sort of racial justice or equality.

It sounds like you’re saying this is shorthand, but it remains to be seen if this shorthand is meaningful.

I think that it’s meaningful in a symbolic way. It’s both easy to understate the importance of symbolism and to overstate it, in the sense that this does not remove any of the ongoing institutional barriers to racial equality in the United States but it is a nice sort of cultural thing to acknowledge the extent of the Black contribution to American history and how much of that contribution has come with tremendous suffering.

READ MORE  Donald Trump leaves the federal courthouse in Miami, Florida, after his arraignment last week. (photo: Chandan Khanna/AFP)

Donald Trump leaves the federal courthouse in Miami, Florida, after his arraignment last week. (photo: Chandan Khanna/AFP)

ALSO SEE: Bill Barr Calls Trump a '9-Year-Old Kid,'

Says Indictment His Own Fault

Motion was filed by prosecutors to restrict storage and use of discovery material turned over to defense in classified papers case

Trump, who was arraigned in Miami last week on a 37-count indictment over his improper storage and handling of classified materials at his Mar-a-Lago resort, can also only view, but not retain, any of the evidence under the direct supervision of his lawyers, the order from the magistrate judge, Bruce Reinhart, stated.

The secrecy ruling in particular will thwart Trump, who has been a vocal critic of justice department prosecutors and special counsel Jack Smith on his Truth Social website, from attempting to publicize or spin any of the evidence to his advantage as he continues to insist the case against him is a politically motivated “witch-hunt”.

“Discovery materials, along with any information derived therefrom, shall not be disclosed to the public or the news media, or disseminated on any news or social media platform, without prior notice to and consent of the United States or approval of the court,” Reinhart’s order, filed on Monday in the southern judicial district of Florida, stated.

Trump, Reinhart said, “shall not retain copies” and may only review case materials “under the direct supervision of defense counsel or a member of defense counsel’s staff”.

The non-dissemination clause applies equally to Trump, the favorite to win the Republican party’s 2024 presidential nomination, and his team of lawyers.

The defense is currently being led by the New York attorney Todd Blanche, a former federal prosecutor, following Trump’s apparent inability to recruit a specialist national security lawyer with a necessary security clearance to help him navigate Espionage Act charges.

Prosecutors filed a motion last week asking for conditions on how the defense stores and uses the papers.

Despite Monday’s victory, the justice department could have an uphill battle to convict Trump, who also faces a criminal fraud trial in New York for an alleged hush money payment to an adult film star, and potential legal peril in Georgia and Washington DC for attempts to overturn his 2020 election defeat to Joe Biden.

The Florida case is in the hands of Judge Aileen Cannon, a Trump appointee to the federal bench, who has already issued rulings favorable to him last year, which were overturned by an appeals court. Analysts have questioned her impartiality and point out she wields substantial power to dismiss or delay the case.

On Sunday, the Washington Post reported that Trump could win a further delay, past the 2024 presidential election, because the case could be tried under the rules of the Classified Information Procedures Act.

Such trials “legally require more precautions and tend to take more time to get to trial than a typical criminal case”, the newspaper said.

Trump pleaded not guilty last week to all charges in the classified documents case at his Miami arraignment, at which only selected reporters and nine members of the public were permitted to attend.

Republicans remain split over Trump’s two indictments. Chris Christie, the former New Jersey governor challenging him for the presidential nomination, on Sunday called the behavior leading to the charges “indefensible” and “deeply disturbing”.

“We would not be here if Donald Trump had simply returned the documents that the government had asked him to return dozens of times,” he told CBS’s Face the Nation.

House Republicans, however, have been quick to defend the former president, questioning the justice department’s motives for bringing the prosecution, and why Biden has not been charged for also retaining classified documents.

In a bizarre defense of Trump last week, the House speaker, Kevin McCarthy, insisted that some of the classified documents stored at Mar-a-Lago in a shower room were completely secure because “a bathroom door locks”.

READ MORE  Anjanette Young and supporters gather at Daley Plaza in Chicago after marching from Federal Plaza to commemorate the National Day of Protests on Oct. 22, 2021. (photo: Jose M. Osorio/Chicago Tribune/AP)

Anjanette Young and supporters gather at Daley Plaza in Chicago after marching from Federal Plaza to commemorate the National Day of Protests on Oct. 22, 2021. (photo: Jose M. Osorio/Chicago Tribune/AP)

The Chicago Police Board voted 5-3 Thursday to fire Sgt. Alex Wolinski for multiple rules violations and “failure of leadership" in the raid at the apartment of Anjanette Young, according to a 31-page written ruling, the Chicago Sun-Times reported.

Young, a social worker, was getting ready for bed in February 2019 when several officers serving a no-knock warrant stormed into her apartment on Chicago's Near West Side searching for a man believed to have an illegal gun.

Police body-camera footage of the raid showed that officers handcuffed Young, who was naked when police arrived, as she repeatedly told them that they were in the wrong place. The city’s law department said Young was naked for 16 seconds but the covering officers put on her kept falling off before she was allowed to get dressed several minutes later.

The botched raid and the city’s handling of it prompted anger from clergy, lawmakers and civil rights activists who decried it as racist and an affront to a Black woman’s dignity.

Young later sued the city over the raid, resulting in the Chicago City Council voting unanimously in December 2021 to pay her $2.9 million to settle her lawsuit.

Young said in a statement released Friday by her attorneys that Wolinski's firing is “only a small piece of the Justice for which I have been waiting.”

“While my heart goes out to his family because they now suffer the consequences of his abhorrent misconduct, I wish all eight members of the Chicago Police Board would have recognized the need and urgency for Sergeant Wolinski’s removal,” she added.

Then-police Superintendent David Brown brought administrative charges against Wolinski in November 2021, recommending that he be fired.

Wolinski, who had joined the Chicago Police Department in 2002, was accused of violating eight departmental rules, including inattention to duty, disobedience of an order and disrespect to or maltreatment of any person.

The Civilian Office of Police Accountability also called for Wolinski’s firing and for suspensions for several other officers present during the raid, although to date no other officers have faced Police Board charges for the raid, the Chicago Tribune reported.

While the incident happened before former Mayor Lori Lightfoot took office in May 2019, her administration later tried to block the police video from airing on television and rejected Young’s Freedom of Information request to obtain video of the incident. Young later obtained it through her lawsuit.

READ MORE  Ricardo Marcos died after a collision in which his Hyundai Elantra became wedged under a tractor-trailer. (photo: Irma Orive/ProPublica)

Ricardo Marcos died after a collision in which his Hyundai Elantra became wedged under a tractor-trailer. (photo: Irma Orive/ProPublica)

For decades, federal safety regulators ignored credible scientific research and failed to take simple steps to stop gruesome roadway crashes involving heavy trucks. Meanwhile, the bodies piled up.

Marcos had spent a long day toiling as a mechanic at a trucking company in McAllen, Texas, a sunbaked city nestled right on the U.S.-Mexico border.

Now he was headed home on U.S. Route 281, a long swath of asphalt that runs parallel to the Rio Grande in this part of Texas. His wife, Irma Orive, was waiting for him.

But Marcos, 61, never made it.

Big commercial trucks are ubiquitous in this part of the world, an endless stream of massive diesel-powered vehicles ferrying goods across the border, and on his drive home, Marcos encountered a large truck pulling a 53-foot trailer. The truck edged out of a driveway and began, slowly, to turn left onto the road, blocking traffic in both directions. It was as if someone had erected a big steel wall.

Video shows what happened next on that night in 2017. Traveling at more than 40 mph, Marcos’s Hyundai slammed violently into the larger vehicle and became wedged beneath it. The impact ripped the top half of the car apart. Marcos did not survive.

The collision did terrible things to his body, breaking his ribs, lacerating his liver and spleen, snapping his neck and damaging the frontal lobes of his brain, according to the medical examiner’s report.

An investigator with the local police department blamed the collision on the truck driver, who was initially charged with negligent homicide, though charges were eventually dropped. ProPublica and FRONTLINE were unable to contact the trucker.

“I still miss him. I miss him every day,” said his widow, 70. “We did everything together.”

The incident was awful and tragic. But it wasn’t particularly uncommon. Collisions in which a passenger vehicle such as a car, SUV or pickup truck slides beneath a large commercial truck are called underride crashes in the jargon of the transportation industry. And they happen all the time: Each year hundreds of Americans die in this type of collision.

The federal government has been aware of the problem for at least five decades.

Reporters for ProPublica and FRONTLINE obtained thousands of pages of government documents on underride crashes — technical research reports, meeting notes, memoranda and correspondence — dating back to the 1960s. The records reveal a remarkable and disturbing hidden history, a case study of government inaction in the face of an obvious threat to public wellbeing. Year after year, federal officials at the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, the country’s primary roadway safety agency, ignored credible scientific research and failed to take simple steps to limit the hazards of underride crashes.

NHTSA officials failed to act, in part, because they didn’t know how many people were killed in the crashes. Their poor efforts at collecting data over the years left them unable to determine the scale of the problem. This spring the agency publicly acknowledged that it has failed to accurately count underride collisions for decades.

According to NHTSA’s latest figures, more than 400 people died in underride crashes in 2021, the most recent year for which data is available. But experts say the true number of deaths is likely higher.

Records show the agency often deferred to the wishes of the trucking industry, whose lobbyists repeatedly complained that simple safety measures would be prohibitively expensive and do lasting damage to the American economy. During the 1980s, for example, industry leaders argued they couldn’t afford to equip trucks with stronger rear bumpers, which are also called rear underride guards; the devices are meant to prevent cars from slipping beneath the trailer during a rear-end collision. The beefier, more robust rear guards would’ve cost an additional $127 each, according to industry estimates.

David Friedman was a top official at NHTSA during the Obama years. “NHTSA has been trying, for decades, to do something about underride deaths. And yet over and over, they haven’t made the progress that we need. Why? Well, I think part of it is because industry just keeps pushing back and undermining their efforts,” said Friedman, who served as the agency’s acting administrator in 2014. “There are so many hurdles put in the way of NHTSA staff when it comes to putting a rule on the books that could address issues like underride.”

The technology at issue — strong steel guards mounted to the back and sides of trucks — is simple and “relatively inexpensive,” Friedman argued. “The costs are small.”

The circumstances surrounding underride crashes vary widely. In some cases, the driver of the smaller vehicle is at fault — they are speeding, texting or simply not paying enough attention to the road. In other cases, the trucker is to blame. Take, for example, a crash that occurred in Caledonia, Wisconsin, in 2020. A truck going roughly 40 mph blew past a stop sign at a four-way intersection. A Volkswagen SUV plowed directly into the side of the larger machine, became trapped between the wheels of the truck and was dragged down the block as shards of glass, steel and plastic shot into the air like shrapnel; miraculously, the SUV driver survived. Police cited the trucker, who declined to be interviewed.

The biggest trucks on the road — properly called tractor-trailers or semi trucks — consist of two parts. At the front is the tractor, which is equipped with a high-horsepower engine capable of pulling 80,000 pounds. A hitch connects it to the trailer, which can range from 28 feet to more than 50 feet long. The typical semitrailer rolls on an array of giant wheels, its floor sitting nearly 4 feet off the ground.

Modern automobiles come equipped with a host of meticulously engineered safety technologies. There are bumpers and crumple zones meant to absorb kinetic energy and reduce the violence of an impact. There are airbags to cushion the driver and passengers.

But in an underride crash, these technologies are rendered moot by the height difference between a large truck and the average passenger vehicle. Typically, it is the windshield of the smaller vehicle that takes the brunt of impact, slamming into the bottom edge of the trailer as the steel pillars holding up the car’s roof collapse. In many cases the airbags don’t even deploy.

This violent sequence of events often produces grievous injuries. Start looking at underride crashes and you’ll quickly notice a pattern of awful head injuries: broken skulls, severely damaged brains, even decapitations. Some victims suffer crushing injuries to the torso or get speared in the chest by jagged chunks of steel.

Truck drivers are rarely harmed in the crashes.

NHTSA officials and Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg declined to be interviewed by ProPublica and FRONTLINE. NHTSA did not respond to written questions from the news organizations, including about why the agency had moved so slowly to address the lethal hazards posed by underride collisions. In a statement, NHTSA defended its record, noting that it had recently created a committee to study the issue and developed new safety rules; it had been directed to take those steps by federal legislation passed in 2021. “Safety is the top priority for the U.S. Department of Transportation and NHTSA,” the agency said.

The American Trucking Associations, a trade group representing the nation’s major commercial haulers, for decades opposed safety regulations that would’ve improved rear underride guards and saved lives. Dan Horvath, the ATA’s vice president for safety policy, said he has little information about the organization’s past positions, but he acknowledged that costs were “a very real factor” for the industry.

Trucking companies now spend billions annually to improve safety, investing in everything from new braking systems to stringent drug-testing for drivers, Horvath said. “Safety is not just a slogan with our members,” he added. “It’s really the fundamental foundation of their operations.”

Eventually the ATA came to support government rules aimed at improving rear guards.

Still, the ATA and other industry groups are continuing to fight congressional efforts to require semitrailers to be equipped with side guards, which could prevent underride crashes like the one that killed Marcos. They said there’s not enough research to support a government mandate, which would impose huge costs on businesses that operate on thin profit margins.

During these five decades of industry resistance and government paralysis, thousands of people have died.

I. Decades of Delay

The year was 1967 and Hollywood star Jayne Mansfield was riding in the front seat of a gray Buick Electra, a massive boat of a sedan, cruising along U.S. Route 90 in Louisiana. It was after 2 in the morning. Ahead of the Buick, a semi truck had slowed to about 35 mph.

Mansfield’s driver failed to brake in time, striking the rear of the vehicle. The Buick’s long hood slid beneath the belly of the semitrailer. The top half of the car was destroyed. The actress and two others were killed. Mansfield’s three children, who’d been riding in the back of the vehicle, survived. One of them, Mariska Hargitay, is now an actor in the “Law & Order” TV franchise.

In the days after Mansfield’s death, leaders at the Department of Transportation began looking into underride crashes — and they quickly made a worrisome discovery.

The federal regulations in place at the time required that large trucks and semitrailers come equipped with a rear bumper, known as a rear guard, meant to prevent underride collisions. But the rules were lax: The guard could hang as much as 30 inches off the ground, far higher than the typical car bumper, and didn’t have to cover the full width of the truck or trailer. And it didn’t have to meet any strength standards.

Most rear guards of this era consisted of three pieces of rectangular steel: a horizontal bar welded to two vertical beams that bolted to the bottom of the trailer. Often crudely fashioned from thin, low-grade metal, the guards did little to prevent underrides — they had a tendency to simply collapse when hit.

A bigger guard built from stronger materials, top officials realized, could save lives.

They announced plans for a new regulation requiring tougher, more substantial guards. “Accident reports indicate that rear end collisions in which underride occurs are much more likely to cause fatalities than collisions generally,” the department noted in a 1969 statement regarding the proposed regulation.

The proposal was not well received by the major trucking companies or the firms that built and sold trucks and semitrailers. In a 1970 letter to the department, the ATA complained about “the unfairness of inflicting upon the industry the heavy cost penalty which would be brought about by the incorporation of a guard of the proposed type.”

The Truck Trailer Manufacturers Association, a lobbying outfit representing semitrailer builders, had little desire to make safer rear guards. In correspondence with the department, the TTMA said it would be “far more practical” to force Volkswagen and other companies making compact cars to produce larger vehicles that were less likely to slip beneath a truck.

Facing backlash, the department scuttled its proposed regulation. “At the present time, the safety benefits … would not be commensurate with the costs of implementing the proposed requirements,” officials wrote in a statement explaining their decision.

Congress in 1970 established NHTSA, giving the new agency broad powers to reduce the number of deaths and serious injuries on America’s roadways. The agency would function as a unit within the larger Department of Transportation, a vast and sprawling bureaucracy tasked with overseeing everything from ships and planes to trains and automobiles. It was a moment of growing public concern over the carnage on America’s roadways — concern fueled in part by consumer advocate Ralph Nader’s damning exposes.

NHTSA immediately took on the underride issue, commissioning a series of studies by scientists in Arizona who ran Chevrolet Impalas and VW Rabbits into rear guards mounted on a simulated semitrailer body. The researchers determined the guards needed to be built bigger and stronger to prevent underrides.

Days before Ronald Reagan was sworn in as president in 1981, NHTSA went public with a revised rule that would beef up the rear guards on trucks and semitrailers. The cost was minimal: The agency estimated the new guards would cost $50 more per vehicle.

But the ATA and other trade organizations voiced their unhappiness about the added expense, which they believed would come out to $127 per trailer. As they had a decade earlier, they said the guards cost too much and would not save many lives.

After Reagan took office, NHTSA underwent a dramatic transformation. The new president had campaigned on promises to slash government regulation, which he saw as an unfair burden on the American economy, and he quickly began reshaping the executive branch.

He installed a new administrator at NHTSA, Raymond Peck Jr., a former lobbyist for the coal industry, who fired agency workers, rescinded existing safety rules and delayed regulations that were under development. The underride rule was jettisoned.

The entire regulatory process at NHTSA “came to a halt,” recalled Lou Lombardo, a physicist who was at the agency at the time. “We had nothing, nothing, nothing to do.”

Asked if people died as a result of the agency’s failure to act on rear underride crashes, Lombardo had an instant reply: “Oh heck yes.”

II. Devastating Consequences

Matt Brumbelow demolishes cars and trucks for a living.

At a sophisticated laboratory near Charlottesville, Virginia, he spends his days smashing brand new vehicles into a slab of superhard concrete and steel. The goal, always, is to identify hidden vulnerabilities — doors that collapse catastrophically, car seats and headrests that could worsen whiplash injuries during a violent impact. A complex pulley system is used to yank the pristine cars, trucks and SUVs — loaded with sensors, and, in some cases, biomechanical dummies — into the test block.

“I love it,” said Brumbelow, who has a degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Virginia. “It’s definitely more than a job.”

He gave journalists from ProPublica and FRONTLINE a tour of the facility, which is run by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, a nonprofit organization dedicated to reducing the harm done by motor vehicle crashes on the nation’s roads. The lab looks like the world’s tidiest and best-lit auto salvage lot — horribly mangled vehicles are everywhere.

By the 1990s, NHTSA had finally adopted a regulation requiring tougher rear guards. The new requirements only applied to newly built semitrailers; older models that were already on the road were exempted.

It took effect in 1998, more than 30 years after Mansfield’s death first drew attention to the issue.

In time, though, it became clear to Brumbelow and his colleagues that this landmark safety regulation was deeply flawed. Sifting through the data from 1,070 collisions, Brumbelow and his team noticed a distinct pattern: Guards built to the new federal standard were still failing, leading to severe underride crashes.

NHTSA, he believed, hadn’t done enough testing on these new guards to see how they would perform under real-world conditions. And other countries had established much more stringent standards — guards used just across the border in Canada, for example, had to be far stronger than those required under NHTSA’s 1998 rule.

By 2010, the institute had purchased a fleet of Chevrolet Malibu sedans and was slamming them into semitrailers equipped with guards meeting the updated federal standard. The results were dismal. “In crash tests that we were running at 35 miles an hour, they were failing,” he recalled.

Brumbelow and his colleagues tested guards made by the eight largest semitrailer manufacturers in the U.S. All but one of them collapsed catastrophically; if these had been real crashes, the people in the cars would’ve been killed or badly injured.

One of the Malibus is still sitting on the floor of the lab. It bears the signature wounds of an underride crash: There is no damage to the bumper and the hood is only mildly dented, but the windshield has been destroyed and the roof is shredded. The dummy in the driver’s seat fared very poorly.

“It’s clear the standard is inadequate,” he said, adding that in his view NHTSA is making crucial policy decisions based on “bad science.”

NHTSA’s dubious decisions have had devastating consequences in the real world.

In 2013, Marianne Karth was behind the wheel of her Ford Crown Victoria sedan, traveling through Georgia on her way to a family wedding. Two of her daughters, Mary and AnnaLeah, were in the back seat; her son Caleb was sitting next to her in the front.

“I came upon slow traffic. I slowed down and a truck driver — apparently — did not. He hit us,” she recalled. Karth’s Ford spun around, then slammed into the rear end of another semi truck and became wedged underneath it.

The truck’s rear guard, which Karth believes met the 1998 federal standard, “just came off onto the ground. It totally came off the truck.”

Photos taken at the crash site show debris scattered all over the roadway. To extricate Karth and her children, a rescue team equipped with hydraulic cutting tools hacked the car apart.

The collision killed 17-year-old AnnaLeah instantly; her sister, 13, survived for a few days in the hospital before dying of her injuries. Caleb sustained a minor concussion.

In the years since the crash, Karth and her husband, Jerry Karth, have channeled their grief into constant activism — petitioning NHTSA, helping to draft federal legislation, meeting with members of Congress, talking to anybody who will listen.

If the truck had been equipped with a stronger guard, said Karth, “it’s possible that my daughters would be alive.”

After witnessing the tests conducted by Brumbelow and the Insurance Institute, many of the country’s major trailer companies voluntarily began building better guards that are far more capable of withstanding a collision.

“We place such a high value on the safety of both our customers and the driving public that we have chosen to provide this improved level of safety and performance as a standard feature — and at no additional cost,” said Bob Wahlin, president and CEO of Stoughton Trailers, a large manufacturer, in a 2016 press release touting the company’s new guards.

In the view of Andy Young, an attorney and truck driver who has testified before Congress about underride collisions, “the industry made changes because they were worried about bad publicity. … They were embarrassed.”

NHTSA, however, did not spring into action. Instead, the agency allowed companies to continue building trailers with the weaker guards. In 2022, more than a decade after Brumbelow’s tests, NHTSA updated its rules. Even then, the agency acted only after the passage of a federal law directing it to do so.

Some safety advocates panned the revised regulation, noting that most big trailer companies are now building guards that are more robust than those required by the new government rule. They saw it as a step back.

“The record speaks for itself: There’s no way you can say that NHTSA acted swiftly to protect people from this known danger,” said Zach Cahalan, executive director of the Truck Safety Coalition, a network of crash survivors and victims’ families. “This is a story I can tell you over and over for different issues. You can’t tell me that people are laser focused on safety.”

While the government has made what Cahalan calls “incremental progress” on rear underride crashes, it has yet to craft regulations addressing collisions that occur when a passenger vehicle runs into the side of a large truck. Such accidents kill hundreds of people annually.

III. Side Guard Safety

Eric Hein sat on a bench on the grounds of a small Methodist church in the rugged Sandia Mountains north of Albuquerque, New Mexico. From time to time, a semi truck chugged up a steep four-lane road nearby, sending a low rumble through the canyon.

In his hands he held photos of his teenage son, Riley Hein, who was killed in a collision with a heavy truck in 2015. He wept softly. The years, Hein said, have scarcely dulled his sorrow.

Riley Hein was driving to high school when an 18-wheeler drifted into his lane. The teen’s Honda Civic smacked into the side of the massive vehicle and became wedged beneath it, trapped between the front and rear wheels.

Instead of stopping, the trucker pulled Riley Hein and his damaged Honda down the highway for half a mile. The car erupted in flames. By the time firefighters were finally able to extinguish the fire, it had been reduced to a husk of charred metal. Riley Hein — a smiley, gregarious teen who played trombone in the school marching band — was dead.

ProPublica and FRONTLINE reporters repeatedly tried to contact the driver, but were unable to locate him.

“We had to sell the house and leave after Riley was killed,” Eric Hein recalled. “It was just too quiet. And it was very painful driving down the highway and seeing the place where his car burned.”

Riley Hein’s story points to another problem: Even when semi trucks are equipped with rear guards, there is nothing to keep a car from hitting the side of a truck and getting stuck beneath it. NHTSA has never adopted regulations requiring any type of underride guard on the sides of trucks.

During the late 1960s, the Department of Transportation said publicly that it intended to “extend the requirements for underride protection to the sides of large vehicles.” But department officials quietly dropped the idea. In 1991, NHTSA revisited the concept and determined that it would be too costly.

Over the past several decades, engineers have developed a host of devices that can be mounted to the underbelly of a semitrailer to prevent underride crashes like the one that took Riley Hein’s life. Most are built from a lattice of thick steel tubes. Wabash National, a major trailer builder based in Indiana, has patented several designs.

But the technology has largely been shunned by the trucking industry. Wabash has never put its side guards into production. (Many semitrailers are equipped with lightweight panels that hang between the front and rear wheels; these are not side guards. These devices are meant to improve fuel-efficiency but don’t provide any safety benefits — they’ll collapse during a crash.)

Hein was shocked when learned about this history. The semitrailer that smashed into his son’s Civic was built by Utility Trailer Manufacturing Company, one of the biggest players in the U.S. market. Eric Hein decided to sue the company, alleging they’d been “negligent for not putting on side underride guards on the trailer that killed Riley.”

It was a relatively novel strategy, and his attorney Randi McGinn, was initially skeptical, pointing out that there had been few successful legal cases built on the theory.

But as McGinn and her co-counsel, Michael Sievers, dug into the evidence, they became increasingly convinced that Hein’s instinct had been right. During discovery they obtained a seven-page document signed by executives from Utility and 10 other semitrailer companies. The document, drafted in 2004, was a pact struck by the biggest companies in the business, a pledge to work cooperatively — and secretly — to thwart any lawsuits stemming from side and rear underride crashes. The arrangement had been orchestrated by Glen Darbyshire, an attorney for the TTMA, the trade group.

As part of the agreement, the firms would keep crucial safety information confidential. That material — including “documents, factual material, mental impressions, interview reports, expert reports, and other information” — wasn’t to be shared with anyone outside of the circle.

Darbyshire declined to be interviewed by ProPublica and FRONTLINE, as did the TTMA.

To McGinn, it seemed the companies had spent years battling lawsuits rather than directing their engineers to address an obvious hazard. “This is the same thing that the tobacco companies did — rather than fix the problem, or admit the problem,” said McGinn. “Corporations have to be responsible for safety, too. They can’t put their profits before the lives of 16-year-old kids.”

In the course of the litigation, Jeff Bennett, Utility’s vice president for engineering, said he’d spent 32 years with the company and had never heard of a car getting trapped under a trailer, other than in the Hein case. The company, he testified, had never designed or built a side guard.

Utility executives argued that adding side guards to trailers would unleash a cascade of new problems: They could cause trailers to get hung up on steep loading ramps, interfere with the functioning of brake lines, and fatigue the frame of the trailer.

After a two-week trial in 2019, jurors in Albuquerque found Utility negligent, ordering the company to pay nearly $19 million to the Hein family. It was one of the largest verdicts to hit the trucking industry in recent years.

Utility did not respond to emails from FRONTLINE and ProPublica requesting comment.

In a statement issued after the trial, the company said, “Utility Trailer does not believe it negligently designed, tested, or manufactured its trailers. Utility Trailer presented uncontroverted evidence that adding a side-underride guard to its trailers would make the trailers more dangerous to the motoring public.”

Since then, however, the company’s stance has shifted dramatically. Utility now sells what it calls a “side impact guard,” offering it as an additional safety feature on its trailers. In its sales brochure, Utility says the guard has been mounted to “over 20 trailers” currently on the road.

In recent years, Sens. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., and Marco Rubio, R-Fla., have repeatedly pushed legislation that would require semis and other heavy trucks to have some sort of side guard. Introduced three times since 2017, the bill has not made it out of committee.

While the senators haven’t been successful with the legislation, they managed to insert language instructing NHTSA to study side guards into the infrastructure bill signed by President Joe Biden in November 2021.

“You know, people don’t like change. And certainly, you know, the trucking companies don’t want to have to invest more money necessarily on safety,” Gillibrand said, when asked about the criticism. “But this is something that is necessary.”

Rubio declined to be interviewed by FRONTLINE and ProPublica.

The industry remains strongly opposed to side guards. In one letter to Congress, the ATA said there wasn’t “sufficient science” on side guards and urged the government to conduct more research on the devices before mandating them.

“When we talk about installing side underride guards, we’re focusing on mitigation after that crash has already happened,” said Horvath, the ATA’s top safety official. “Unfortunately, resources are not limitless. And if I’m going to direct resources as a trucking company, I want to focus on avoiding that crash from ever occurring.” Big trucking companies are supportive of new electronic technologies such as automatic emergency braking systems, which use cameras or sensors to detect road hazards and halt the truck before it crashes, or engine modules that limit the speed of a truck, he said.

Lewie Pugh, a retired trucker, is executive vice president of the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association, a group representing individual drivers and small trucking firms. “Speaking as somebody who has real-world experience driving a truck, I believe there are probably certain instances, certain situations where side underride guards will work and save lives,” Pugh said. “I also believe that there are certain instances where side underride guards will cost lives, and we don’t know the unintended consequences.”

If you ask Pugh, he’ll tell you that truckers have every right to be skeptical of both the government and new technologies. In 1975, NHTSA adopted a regulation requiring anti-lock brakes on large trucks and trailers. The new braking systems, however, proved to be glitchy and prone to failure, leaving truckers rolling down the road without any way to stop.

He worries that if side guards are mandated, the costs will hit independent truckers and small operators hard.

“Research is key, and don’t use the truck drivers and the trucking companies as the guinea pigs,” Pugh said. “Let’s make sure this stuff is working.”

IV. Counting Crashes

NHTSA operates on a $1.3 billion annual budget. The agency is responsible for everything from setting standards for motorcycle helmets to investigating defective vehicles to studying automated driving technologies. It is America’s primary roadway safety agency.

And yet NHTSA is unable to count the number of underride crashes that occur in the U.S. each year.

An analysis of the agency’s data by ProPublica and FRONTLINE indicates that more than 400 people, including several truckers, died in underride collisions in 2021, the most recent year for which complete figures are available.

But the true death toll is likely far higher. Pointing to a series of studies dating back to the 1970s, experts say NHTSA has never been able to properly track underride crashes, despite spending hundreds of millions of dollars on data-collection efforts.

“There is a severe undercounting of the number of underride crashes in this country,” said Harry Adler, a co-founder of the Institute for Safer Trucking, an activist group that follows the data closely.

Part of the problem is that NHTSA relies on local and state law enforcement officers to investigate serious collisions and document their findings. Those police reports are sent to NHTSA and compiled into a single, mammoth database, cataloging tens of thousands of incidents every year.

The agency, however, has never required these first responders to track underride crashes and has offered police little training on the issue. As Adler notes, “only 17 states have a field on their police accident reports to indicate if an underride occurred.”

Underride “fatalities are likely underreported,” stated the Government Accountability Office in a 2019 report urging NHTSA to do a better job of educating police officers and other law enforcement personnel about the crashes.

NHTSA’s own data can be conflicting. ProPublica and FRONTLINE compared two agency databases. One contained detailed information, including photos and crash diagrams, on 27 fatal side and rear underride truck collisions. In the other one — the primary data set of fatal crashes — only three of those 27 accidents were listed as underrides.

Recently, the agency acknowledged that its numbers on underride crashes are unreliable. NHTSA said it has recently taken steps to improve its data-collection practices.

The issue is not academic. When NHTSA looks at a new safety rule, it makes strict economic calculations. How many lives will be saved by the regulation? How much will it cost businesses to implement the rule?

NHTSA generally won’t adopt a new safety measure unless it can be shown to work and to cost the industry no more than $12.5 million for each life it saves.

Critics said the undercount of fatalities played an important role this spring, when NHTSA released new research on the costs and benefits of side guards.

The agency determined the devices aren’t economically feasible — they would be too expensive and save too few lives. According to NHTSA’s calculations, mounting the devices on every new semitrailer in the U.S. would cost upwards of $778 million and would only prevent 17.2 deaths per year.

Some experts, though, are skeptical of NHTSA’s calculations. They said that NHTSA made faulty assumptions about the efficacy of side guards and the number of lives at risk. The National Transportation Safety Board, an independent federal agency, has said publicly that NHTSA’s analysis underestimated the potential benefits of the guards.

Brumbelow’s organization concluded that a more realistic estimate of the lives that side guards would save each year is 159 to 217, far higher than what NHTSA found.

The higher number flips the cost-benefit equation in favor of requiring trucks to have side guards.

“There are hundreds of lives that are being lost every year in side underride crashes,” he said. “The system that would be needed on a trailer to prevent so many of those fatalities from occurring is not overly complex.”

NHTSA, he concluded, needs to take the matter “more seriously.”

V. “Complete Success”

Against one wall in a crowded workshop in Cary, North Carolina, are an array of tool chests and welding equipment. Hunks of steel and extruded aluminum — truck parts — lie on a tall workbench. A shelving unit holds several child car seats.

In the center of the space, Aaron Kiefer is sorting through a pile of manilla folders. He is a mechanical engineer and accident reconstructionist. Clients — insurance firms, attorneys and, quite often, trucking companies — hire him to figure out what transpired in the moments before a serious crash.

Kiefer has plenty of work. In recent years America’s streets and highways have become more perilous, with fatal collisions of all types increasing significantly; Buttigieg, the transportation secretary, recently declared it a “national crisis.” Deaths due to truck crashes have surged by nearly 50% over the past decade, to 5,788 in 2021; nearly 155,000 people were injured that year.

Kiefer’s case files are the stuff of nightmares. One particularly gruesome investigation involved a car that had been cut in half by an encounter with a semi truck. Looking at photos from the crash, which occurred in Alabama, he said, the auto “passed all the way underneath the trailer.” He added, flatly, “It was not a survivable crash.”

Kiefer said he’s investigated “at least 100” underride collisions. “Seeing these types of accidents, over and over, has become increasingly a frustration of mine, personally,” he explained. “When you have this mismatch between the commercial vehicle and the passenger vehicle, the passenger vehicle always suffers. And I feel like there are reasonable ways to prevent these types of accidents.”

In hopes of reducing this roadway violence, even a little, Kiefer has designed a side guard using superstrong polyester webbing — the same material is used to lift extremely heavy cargo — attached to a matrix of steel bars. The goal is to get the trucking industry to adopt the device, which weighs 400 pounds, far less than other side guards; the lighter weight should translate into better fuel efficiency and other benefits for truckers.

On a warm day last fall, Kiefer staged a test of the device, dubbed a Safety Skirt, on a huge square of asphalt at the North Carolina State Highway Patrol training center in Raleigh. It was a grassroots effort. Welders at Maverick Metalworks, a local business, had helped Kiefer fabricate the guard. A salvage yard had donated a sacrificial Nissan Altima, which was delivered by volunteer from a nearby towing company.

Kiefer brought an old, battered semitrailer equipped with his guard to the facility, which under normal circumstances is used by police practicing high-speed driving techniques. He was planning a T-bone-type crash: The Nissan would strike the side of a trailer at a 90-degree angle. Marianne and Jerry Karth were on hand to witness the event, as was Lois Durso, an activist who had driven up from Florida with her husband.

With police officers and local reporters watching, the car was towed toward the trailer at 35 mph, smacked into the guard with loud thud and bounced off. The blow crunched the hood of the Nissan and set off the airbags, but no underride had occurred. It worked. “Yes! Yes! Yes!” shouted Marianne Karth.

“Complete success,” Kiefer said, smiling. “This is awesome. It’s a step towards highway safety.”

Now he just has to get NHTSA and the trucking companies to agree.

READ MORE  A Ugandan wearing a mask with a rainbow sticker takes part in the Gay Pride parade in Entebbe on August 8, 2015. (photo: Isaac Kasamani/AFP)

A Ugandan wearing a mask with a rainbow sticker takes part in the Gay Pride parade in Entebbe on August 8, 2015. (photo: Isaac Kasamani/AFP)

When identity gets criminalized, everyone gets hurt.

Uganda is far from the only nation to criminalize homosexuality — at least 62 other countries, most of them in Africa and the Middle East, also have anti-gay laws on the books. But Uganda’s regulation cracking down on LGBTQ existence is especially draconian. It outlaws same-sex sexual activity but also punishes others who merely tolerate the existence of queer people. According to the law, a person can be punished for even leasing property to a gay person.

This isn’t Uganda’s first attempt to pass such legislation: The nation has had laws forbidding “buggery” (anal sex between men) on the books since British colonial times. In 2009, prodded by support from extremist groups of American evangelical Christians, Uganda’s parliamentary body attempted to pass a law broadening punishable activities to include other forms of gay sex, as well as the “promotion of homosexuality.” Although that law failed, a similar one was passed in 2014. That law was later overturned by the nation’s constitutional court on a technicality; the current law is also being challenged before the court.

Regardless of whether the new law stands, damage has already been done. As Uganda’s government has deliberated over the law, there’s been an uptick in police and civilian harassment and violence against LGBTQ Ugandans, and terrified citizens are trying to flee the country.

When LGBTQ Ugandans suffered a wave of violence after the 2014 law passed, law enforcement set the tone — but ordinary civilians perpetrated much of the abuse, said Jennifer Leaning, a public health and human rights expert at Harvard’s François-Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights, during a public event on Monday. The same dynamic appears to be unfolding now.

But the law also poses threats to those outside the LGBTQ community, including the many Ugandans who support it. Stigmatizing identities has a domino effect on other people: “Everyone is affected when vulnerable people are pushed out of care,” said Asia Russell, executive director of Health GAP, an international HIV equity advocacy organization.

On the face of it, criminalizing homosexuality is immensely dehumanizing and damaging. But the destruction this law can cause runs much deeper, and could set Uganda back on a range of health metrics.

Here’s how that could look.

Uganda’s HIV progress is at risk

One big fear experts have about the AHA is that it will lead to rising rates of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among all Ugandans. HIV is already mired in stigma and misconceptions in the region, and the law will likely drive sexual activity, STI prevention efforts, and care-seeking for HIV and STIs underground.

“If you are worried about being accused of being gay, then you certainly are not going to come in for HIV testing,” said Matthew Kavanagh, a professor of global health at Georgetown University, “even if you’re a heterosexual man.”

In recent years, Uganda had been making steady progress on HIV. The nation was an early adopter of many of the preventive strategies that emerged in the days before HIV medications were available on the continent. Its government hospitals implemented services aimed at preventing transmission from mothers to children in 2000, and the country was a pioneer among African countries in offering HIV testing and education services to the general public. And in the years after HIV treatment rolled out in Uganda in 2004, the country implemented some relatively progressive HIV testing policies.

Between 2010 and 2021, the country’s new HIV infection rate decreased by 39 percent.

In Uganda, as in most of sub-Saharan Africa, most new HIV infections are in women — not in men who have sex with men, as in the US. In 2021, 65 percent of new HIV infections in Uganda were in women and girls, who are most likely to be infected through heterosexual sex, compared with only 19 percent in the US in 2019.

Still, many Ugandans associate HIV risk with gay sex, said Kavanagh. Therefore, merely engaging in HIV prevention, testing, and treatment efforts can implicate someone as being gay and lead to punishment.

Richard Lusimbo, a Ugandan LGBTQ rights activist who leads the Uganda Key Populations Consortium, said during Monday’s event that already, peer sex educators have been jailed for providing HIV preventive services. “All they did was carrying out promotion of health services and providing more information to their peers around condom use, around lubricants,” he said. “Having even lubricant becomes a risk.”

With the consequences so severe, it wouldn’t be a surprise if all people at risk avoided any kind of sexual health care, but especially HIV testing and care services. That poses an enormous threat to Uganda’s progress on HIV.

Already, the AHA has led to so much fear among many people living with HIV that some HIV/AIDS treatment centers in Uganda’s capital are nearly empty, and the HIV treatment medications they normally hand out to patients are piling up, according to reporting from Reuters.

Since the law’s passage, drop-in centers that offer HIV services to members of Uganda’s LGBTQ community have seen a 60 percent drop in service utilization, said Kenneth Mwehonge, who directs Uganda’s Coalition for Health Promotion and Social Development, during Monday’s event.

It’s very worrisome if people living with HIV aren’t getting the medications they need. Modern medical treatment for HIV is extraordinarily effective — it generally makes the virus undetectable, which allows people with HIV to live normal life spans and prevents them from transmitting the infection through sex. But untreated people are at high risk for progressive and life-threatening immune system problems, and are much more likely to transmit the disease through sexual activity.

If the trend of avoiding care persists, it means more HIV will go undiagnosed and untreated, and transmission will likely rise across all populations — not just among gay people.

The law threatens the trust at the heart of provider-patient relationships

By deputizing all of Ugandan society as reporters of homosexual activity, the AHA is likely to raise patient concerns about the safety of seeking medical care, especially if there’s a concern they could be suspected to be gay. That could lead people — LGBTQ and not — to avoid seeing medical providers for a whole range of diseases, both infectious and not.

Under a section of the AHA concerning “promotion of homosexuality,” people can be punished for contributing to the normalization of gay sex acts. Punishments in this case include fines and license revocation. Another section indicates all Ugandans have a “duty to report” those suspected of even intending to have gay sex. This section contains language that protects health care providers from violating confidentiality provisions by reporting a patient.

For these reasons, the law has been widely interpreted to mean that health care providers must call the police on any patient they believe to be gay.

“When you look at the act, it’s very broad and very vague when it talks about promotion,” said Lusimbo, during Monday’s event. “So does providing a service to an LGBTI person qualify as promotion?”

The implication that it does is creating a lot of hesitation among providers who “do not want to be associated or be seen as people who are promoting or engaging in amplifying the voices of the LGBT community,” he said.

When trust in health providers breaks down, it can be lethal to a community’s health, said Kavanagh. “What we know — whether it’s HIV, or Covid, or [mpox], or Ebola — is that trust between the health sector and the population is perhaps the most critical tool in ensuring that the people who are experiencing the highest rates of transmission get diagnosed, get treatments, get a vaccine,” he said. “And what this law is requiring is that health workers actively break that trust. And that is very, very dangerous for public health.”

Indeed, Uganda’s recent success at containing an Ebola outbreak with relative speed relied on community members’ trust in traditional healers, community health workers, and conventional medicine practitioners. Under the AHA, a person with Ebola symptoms might hypothetically avoid seeking care out of fear they’d be suspected of homosexuality because their symptoms resembled acute HIV infection. It’s not only LGBTQ people who would suffer under those circumstances.

Critical foreign aid supporting Uganda’s health and other infrastructure may be withdrawn or redirected

Foreign aid is critical for supporting Uganda’s health system, and important for other parts of its infrastructure — and donors might be pulling back some of that aid now that the AHA has passed. That could result in weaknesses in health care and other systems that harm the whole of Ugandan society.

Uganda is one of the top recipients of foreign aid globally. Aid from foreign governments generally comprises between 6 and 8 percent of the nation’s gross national income, and thousands of nonprofit organizations also operate within the country.

Over the last few months, as Uganda’s political bodies considered the latest version of the AHA in earnest, countries and organizations have begun reconsidering their relationship and their assistance to the country. The World Bank and the United States Agency for International Development are reevaluating their work in Uganda, and a joint statement from several major funders of the nation’s health infrastructure called for the act to be reconsidered.

Programs funded by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, which provides about $400 million in HIV funding to Uganda each year, could become illegal under the new law, said Russell. “There’s a huge concern that PEPFAR strategy becomes promotion of homosexuality under this law,” she said.

Academic institutions that work within the country are also reconsidering how their funds are being used. Louise Ivers, director of Massachusetts General Hospital’s Center for Global Health, wrote in an email to Vox that the organization planned to redirect the millions it spends on its Uganda program away from governmental to nongovernmental institutions.

That means shifting from supporting a public university in southwest Uganda — which helps sustain nurse training and community health work programs — to instead supporting nongovernmental organizations working on humanitarian efforts and education aimed at reducing LGBTQ discrimination in Uganda.

“In many ways just ‘pulling out’ is easy, but instead we are trying to take a careful approach that will both serve the poorest patients (a priority to us as clinicians), while also following through on our values,” Ivers wrote.

Ivers’s concern — and that of many other funders — is to avoid compounding harm to LGBTQ communities by withdrawing critical support not only for HIV care, but for the entire health care system.

It’s not just funding for health services that donors are reconsidering: Kavanagh said there is a “big push” to also review World Bank loans for infrastructure support to the nation. In fact, during the 2014 effort to pass an earlier version of the AHA, the World Bank paused its loans to Uganda.

Reducing support for any public goods in Uganda would likely cause pain for all Ugandans: A weaker health system and bad roads hurt everyone. “The health sector is of interest to the Ugandan government, but other sectors are even more important,” said Kavanagh.

Experts fear a spillover effect to other populations and other countries

Lusimbo fears the AHA will lead to increased persecution not only of LGBTQ people but also of other marginalized groups. In particular, he’s concerned the next step for the law’s proponents is to push for legislation targeting harm reduction programs that provide care to people who inject drugs.

There’s also concern that the AHA will lead Uganda’s neighboring countries to adopt similar attitudes toward LGBTQ people, if not similar legislation. Ingrid Katz, a research scientist at the Center for Global Health at Massachusetts General Hospital, noted that a “family protection bill” in Kenya uses the same language as the AHA. Lusimbo said Ghana and Tanzania are also seeing rising rates of anti-LGBTQ sentiment — “they seem to be having kind of a template that is being followed,” he said.

International pressure is mounting against Uganda, but it could also backfire. Uganda’s president has been defending the law as anti-imperialist: As he explains it, the West is trying to impose its values of LGBTQ tolerance on Uganda.

It’s hard not to note the irony here; after all, American evangelicals helped transform Uganda’s long-simmering homophobia into law. Still, some human rights advocates within the country have asked foreign partners to tread lightly in their opposition to the law — in part to avoid the appearance that resistance is funded by outside interests.

The difficult consequences of any actions make this a challenging time for people who care about public health. Continuing aid appears to condone an egregiously harmful law — but withdrawing aid will also hurt innocent people.

“Governments that espouse hate shouldn’t get funding,” said Kavanagh, and donors who invest in Uganda’s essential social services “have to creatively address this horrific set of policy choices. The economic ramifications, hopefully, will wake Museveni up,” he said.

Although the law is popular among Uganda’s general public, some LGBTQ advocates are clear that they do not want the US government and other funders to take measures that would cause harm to Ugandans more broadly. “We do not believe in sanctions or cutting off aid because at the end of the day, this again has a very negative impact on other Ugandans,” said Lusimbo.

Instead, aid that directly impacts LGBTQ communities or supports the legal work of challenging the AHA before Uganda’s constitutional court is key, he said.

“This is a really delicate time for the outside world to put immense pressure on Uganda,” said Leaning, the human rights expert. Right now, she said, the best help for the nation’s most vulnerable is likely “funding or expertise — done quietly.”

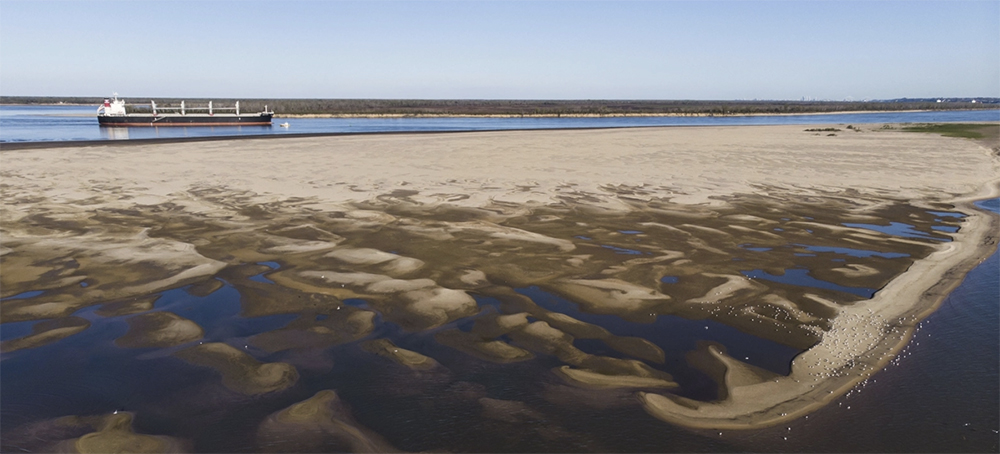

READ MORE  An aerial view of the Parana River, which water level reached a historic low, in Argentina, on February 15, 2022. (photo: Marcelo Manera/Anadolu Agency)

An aerial view of the Parana River, which water level reached a historic low, in Argentina, on February 15, 2022. (photo: Marcelo Manera/Anadolu Agency)

As conditions that best support life shift toward the poles, more than 600 million people are already living outside of a crucial “climate niche,” facing more extreme heat, rising food scarcity and higher death rates.

The research, which adds novel detail about who will be most affected and where, suggests that climate-driven migration could easily eclipse even the largest estimates as enormous segments of the earth’s population seek safe havens. It also makes a moral case for immediate and aggressive policies to prevent such a change from occurring, in part by showing how unequal the distribution of pain will be and how great the improvements could be with even small achievements in slowing the pace of warming.

“There are clear, profound ethical consequences in the numbers,” Timothy Lenton, one of the study’s lead authors and the director of the Global Systems Institute at the University of Exeter in the U.K., said in an interview. “If we can’t level with that injustice and be honest about it, then we’ll never progress the international action on this issue.”

The notion of a climate niche is based on work the researchers first published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2020, which established that for the past 6,000 years humans have gravitated toward a narrow range of temperatures and precipitation levels that supported agriculture and, later, economic growth. That study warned that warming would make those conditions elusive for growing segments of humankind and found that while just 1 percent of the earth’s surface is now intolerably hot, nearly 20 percent could be by 2070.

The new study reconsiders population growth and policy options and explores scenarios that dramatically increase earlier estimates, demonstrating that the world’s environment has already changed significantly. It focuses more heavily on temperature than precipitation, finding that most people have thrived in mean annual temperatures of 55 degrees Fahrenheit.

Should the world continue on its present pathway — making gestures toward moderate reductions in emissions but not meaningfully reducing global carbon levels (a scenario close to what the United Nations refers to as SSP2-4.5) — the planet will likely surpass the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting average warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius and instead warm approximately 2.7 degrees. That pathway, which accounts for population growth in hot places, could lead to 2 billion people falling outside of the climate niche within just the next eight years, and 3.7 billion doing so by 2090. But the study’s authors, who have argued in other papers that the most extreme warming scenarios are well within the realm of possibility, warn that the worst cases should also be considered. With 3.6 degrees of warming and a pessimistic climate scenario that includes ongoing fossil fuel use, resistance to international migration and much more rapid population growth (a scenario referred to by the U.N. as SSP3-7), the shifting climate niche could pose what the authors call “an existential risk,” directly affecting half the projected total population, or, in this case, as many as 6.5 billion people.