Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

ADDED: READ THIS WITH CAUTION!

ONE OF THE LINKS INCLUDED IS A BLOG OPPOSED TO GOVERNMENT SPENDING - NO SCIENTIFICTIC CREDENTIALS NOTED.

POLITICIANS ARE IN NO POSITION TO DETERMINE THE SOURCE OF THE VIRUS & ONE SHOULD BE CAUTIOUS OF AN UNQUALIFIED WITCH HUNT!

New reporting, attributed to U.S. government sources, identified a coronavirus researcher at the Wuhan Institute of Virology who fell ill in November 2019.

The funding came in three grants totaling $41 million, doled out by USAID and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, or NIAID, the agency then headed by Dr. Anthony Fauci. Hu is listed as an investigator on the grants.

The news that U.S. intelligence had learned that three Wuhan Institute of Virology lab workers had been hospitalized with Covid symptoms in November 2019, significantly before the outbreak at the city’s seafood market, was first reported by the Wall Street Journal in May 2021. But the revelation had curiously little impact on the broader debate over the origin of the pandemic, even as it would invalidate, if confirmed, the claim that the pandemic originated at the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market when the virus allegedly jumped from an animal to a human. No such animal has been identified, but new reporting by Michael Shellenberger and Matt Taibbi, sourced to three government sources familiar with a State Department investigation, has identified the three lab workers as Ben Hu, Yu Ping, and Yan Zhu. Two of the grants ran from 2014 through 2019. The third was cut off in 2020 by President Donald Trump after the outbreak in Wuhan.

The NIAID and USAID grants list Hu as an investigator in the projects being funded. Hu is a top deputy to Shi Zhengli, known in the virology world as “batwoman” for her work extracting samples of viruses from bats in Chinese caves. The FOIA documents were first obtained by White Coat Waste in 2021 but given new relevance with the reporting of Hu’s involvement.

The Times of London, meanwhile, also recently reported new details about activity in the Wuhan Institute of Virology in the run-up to the pandemic, similarly sourced to three investigators with the U.S. State Department. That report includes allegations about the Wuhan labs’ collaboration with Chinese military scientists, buttressing what had once been dismissed as a fringe conspiracy theory: that the virus was connected to bioweapons research. “In the lead-up to the pandemic, the Wuhan institute frequently experimented on coronaviruses alongside the Academy of Military Medical Sciences, a research arm of the People’s Liberation Army,” the Times reported. “In published papers, military scientists are listed as working for the Beijing Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology, which is the military academy’s base.”

Much of the focus of the Times investigation is on a virus found in a mine where workers were sickened in 2012, leading to hospitalizations and deaths. Another key question probed by the State Department investigators relates to a project proposed to the Pentagon by Shi and two collaborators, Ralph Baric of the University of North Carolina, and Peter Daszak of EcoHealth Alliance. The proposal, submitted to the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, entailed inserting a furin cleavage site into a coronavirus. It was rejected, but speculation remains as to whether some of the research was conducted anyway.

“The investigators spoke to two researchers working at a US laboratory who were collaborating with the Wuhan institute at the time of the outbreak,” the Times reported. “They said the Wuhan scientists had inserted furin cleavage sites into viruses in 2019 in exactly the way proposed in Daszak’s failed funding application to Darpa.” A key hallmark of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, is its furin cleavage site (FCS).

“The significance of the fact that ‘patient zero:’ Ben Hu received US funding from NIH and USAID in 2018-2019 is that NIH and USAID support to Hu potentially directly funded the insertion of FCS sequences into SARS-ike coronaviruses that had been proposed in EcoHealth’s/WIV’s unsuccessful 2018 DARPA grant application,” said Dr. Richard Ebright, a molecular biologist and laboratory director at the Waksman Institute of Microbiology. “Just as USAID and NIH support to Shi potentially funded the insertion of FCS sequences into SARS-ike coronaviruses that had been proposed in EcoHealth’s/WIV’s unsuccessful 2018 DARPA grant application.”

Congress has mandated the U.S. government to declassify information related to the pandemic’s origin and the Wuhan Institute of virology by Sunday, June 18.

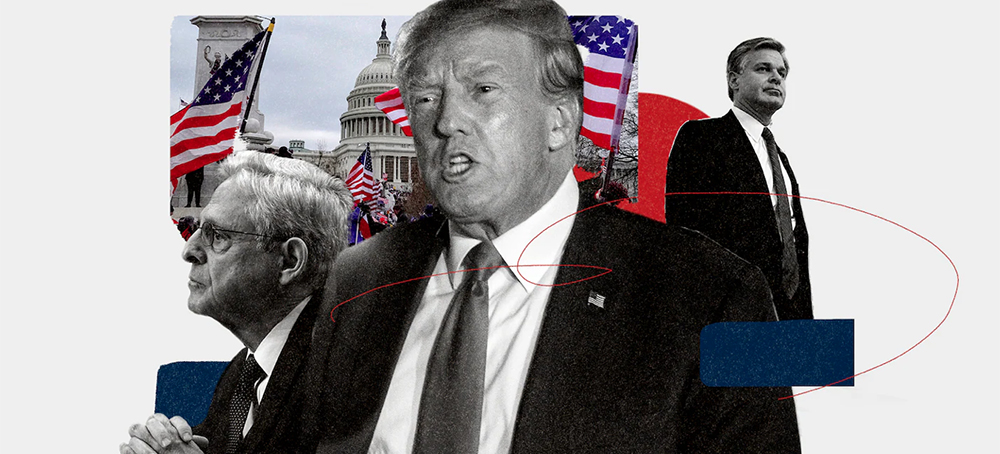

READ MORE  Merrick Garland, Donald Trump and January 6. (photo: Elena Lacy/Bonnie Jo Mount/Jabin Botsford/Bill O’Leary/WP)

Merrick Garland, Donald Trump and January 6. (photo: Elena Lacy/Bonnie Jo Mount/Jabin Botsford/Bill O’Leary/WP)

In the DOJ’s investigation of Jan. 6, key Justice officials also quashed an early plan for a task force focused on people in Trump’s orbit

In the two months since the siege, federal agents had conducted 709 searches, charged 278 rioters and identified 885 likely suspects, said Michael R. Sherwin, then-acting U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia, ticking through a slide presentation. Garland and some of his deputies nodded approvingly at the stats, and the new attorney general called the progress “remarkable,” according to people in the room.

Sherwin’s office, with the help of the FBI, was responsible for prosecuting all crimes stemming from the Jan. 6 attack. He had made headlines the day after by refusing to rule out the possibility that President Donald Trump himself could be culpable. “We are looking at all actors, not only the people who went into the building,” Sherwin said in response to a reporter’s question about Trump. “If the evidence fits the elements of a crime, they’re going to be charged.”

But according to a copy of the briefing document, absent from Sherwin’s 11-page presentation to Garland on March 11, 2021, was any reference to Trump or his advisers — those who did not go to the Capitol riot but orchestrated events that led to it.

A Washington Post investigation found that more than a year would pass before prosecutors and FBI agents jointly embarked on a formal probe of actions directed from the White House to try to steal the election. Even then, the FBI stopped short of identifying the former president as a focus of that investigation.

A wariness about appearing partisan, institutional caution, and clashes over how much evidence was sufficient to investigate the actions of Trump and those around him all contributed to the slow pace. Garland and the deputy attorney general, Lisa Monaco, charted a cautious course aimed at restoring public trust in the department while some prosecutors below them chafed, feeling top officials were shying away from looking at evidence of potential crimes by Trump and those close to him, The Post found.

In November, after Trump announced he was again running for president, making him a potential 2024 rival to President Biden, Garland appointed special counsel Jack Smith to take over the investigation into Trump’s attempt to overturn the 2020 election.

On June 8, in a separate investigation that was also turned over to the special counsel, Smith secured a grand jury indictment against the former president for mishandling classified documents after leaving office. Trump was charged with 31 counts of violating a part of the Espionage Act, as well as six counts arising from alleged efforts to mislead federal investigators.

The effort to investigate Trump over classified records has had its own obstacles, including FBI agents who resisted raiding the former president’s home. But the discovery of top-secret documents in Trump’s possession triggered an urgent national security investigation that laid out a well-defined legal path for prosecutors, compared with the unprecedented task of building a case against Trump for trying to steal the election.

Whether a decision about Trump’s culpability for Jan. 6 could have come any earlier is unclear. The delays in examining that question began before Garland was even confirmed. Sherwin, senior Justice Department officials and Paul Abbate, the top deputy to FBI Director Christopher A. Wray, quashed a plan by prosecutors in the U.S. attorney’s office to directly investigate Trump associates for any links to the riot, deeming it premature, according to five individuals familiar with the decision. Instead, they insisted on a methodical approach — focusing first on rioters and going up the ladder.

The strategy was embraced by Garland, Monaco and Wray. They remained committed to it even as evidence emerged of an organized, weeks-long effort by Trump and his advisers before Jan. 6 to pressure state leaders, Justice officials and Vice President Mike Pence to block the certification of Biden’s victory.

In the weeks before Jan. 6, Trump supporters boasted publicly that they had submitted fake electors on his behalf, but the Justice Department declined to investigate the matter in February 2021, The Post found. The department did not actively probe the effort for nearly a year, and the FBI did not open an investigation of the electors scheme until April 2022, about 15 months after the attack.

The Justice Department’s painstaking approach to investigating Trump can be traced to Garland’s desire to turn the page from missteps, bruising attacks and allegations of partisanship in the department’s recent investigations of both Russia’s interference in the 2016 presidential election and Hillary Clinton’s use of a private email server.

Inside Justice, however, some have complained that the attorney general’s determination to steer clear of any claims of political motive has chilled efforts to investigate the former president. “You couldn’t use the T word,” said one former Justice official briefed on prosecutors’ discussions.

This account is based on internal documents, court files, congressional records, handwritten contemporaneous notes, and interviews with more than two dozen current and former prosecutors, investigators, and others with knowledge of the probe. Most of the people interviewed for this story spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal decision-making related to the investigation.

Spokespeople at the Justice Department and FBI declined to comment or make Garland, Monaco or Wray available for interviews.

Garland, 70, whose department includes the FBI, has maintained that DOJ would follow the facts in investigating the attack on the Capitol, starting with “the people on the ground” and working up. In a speech he was heavily involved with writing to mark the first anniversary of the attack, Garland lauded the department’s progress, while also nodding to public scrutiny of the pace of the investigation.

“In circumstances like those of January 6th, a full accounting does not suddenly materialize,” Garland said. “We follow the facts, not an agenda or an assumption. The facts tell us where to go next.”

Asked about prosecuting Trump, Garland generally has expressed the same sentiment as Sherwin that no one is above the law. The Justice Department will hold accountable anyone “criminally responsible for attempting to interfere with the … lawful transfer of power from one administration to the next,” Garland said in the summer of 2022.

In an interview with The Post, Matthew M. Graves, who succeeded Sherwin as the U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia, cautioned against drawing conclusions about the government’s approach while its work is ongoing. He noted that 23 of 29 affiliates and members of the Oath Keepers charged in connection with the attack had been convicted so far, several for seditious conspiracy, the first such convictions since 2009.

“I hear everybody kind of wants everything to go faster,” Graves said. “But I think if you kind of look at this in historical perspective — what the department has been able to achieve — I think when people get some distance from it, it will stand as something unprecedented.”

Still, there were consequences to moving at a slower pace. For many months after the attack, prosecutors did not interview White House aides or other key witnesses, according to authorities and attorneys for some of those who have since been contacted by the special counsel. In that time, communications were put at risk of being lost or deleted and memories left to fade.

Peter Zeidenberg, who helped lead a special counsel probe of the George W. Bush White House, said Garland and Monaco had to tread carefully because investigating a president’s attempts to overturn an election is a novel case, and they did not want to appear partisan. “But you can take it to the extreme … you work so hard not to be a partisan that you’re failing to do your job.”

‘Everybody keeps asking, “Where the hell is the FBI?”’

Outnumbered and desperate to regain control of the Capitol following the Jan. 6 attack, Capitol Police had for the most part let the rioters walk away. The task of identifying the thousands of attackers — let alone building cases against them — fell to a Justice Department whose leadership was in transition.

William P. Barr had left his post as attorney general two weeks before the attack amid a growing rift with Trump. His successor, Jeffrey Rosen, held the office for less than a month, and Garland would not be sworn in until March 11. Biden’s pick to replace Sherwin as the U.S. attorney in D.C. would not take office for another 10 months.

At the FBI, Trump, over the previous year, had repeatedly threatened to fire Wray, 56, who had in turn tried to keep a low profile. The investigations of Clinton’s email and Russia’s interference in the 2016 election had been run out of FBI headquarters and created firestorms. Since then, Wray and his team sought to avoid even an appearance of top-down influence by having local field offices run investigations and make day-to-day decisions. In fact, when it came to the Jan. 6 investigation, agents noticed that Wray did not travel the five blocks from FBI headquarters to the bureau’s Washington field office running the investigation for more than 21 months after the attack. In that time, people familiar with the investigation said, he had never received a detailed briefing on the topic directly from the assistant director in charge of the office, Steven D’Antuono.

Against that backdrop, a key partnership formed on the night of the insurrection between D’Antuono and Sherwin that would set the direction for the early phase of the investigation.

The two agreed they needed to round up as many Jan. 6 rioters as possible to dissuade extremists from disrupting Biden’s inauguration in two weeks.

Prosecuting violent Trump supporters wasn’t the job Sherwin had signed up for. The longtime Miami federal prosecutor and former naval intelligence officer had come to D.C. the previous year on a short-term assignment as a top adviser to Barr on national security matters. Barr then named him in May 2020 to be acting U.S. attorney in Washington, raising concerns that the office — which was then handling multiple investigations of interest to Trump — would continue to be politicized. But Sherwin had experience with domestic extremists, as well as with Trump. In 2018, he had helped track, interrogate and charge a Florida Trump supporter who sent mail bombs to Democratic Party officials and media organizations. The following year, he won the conviction of a Chinese trespasser at Trump’s Mar-a-Lago Club in Palm Beach, Fla.

For D’Antuono, 51, an unlikely series of past tests now seemed like practice for the glare of Jan. 6, he told colleagues. An accountant by training, he had been promoted to a senior post in the FBI’s St. Louis field office in 2014, just as the police shooting of Michael Brown touched off protests in nearby Ferguson and his office was called to investigate the shooting. D’Antuono then took over the Detroit field office before the pandemic hit. Michigan became a hotbed of lockdown protests, and he oversaw an investigation of militia members accused of plotting to kidnap Gov. Gretchen Whitmer (D). Weeks before the 2020 presidential election, Wray named him head of the D.C. office.

Two days after the Capitol attack, the FBI began announcing charges that were meant to send a message. Agents arrested the man pictured propping his feet on House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s desk. The next day it was the man in the horned headdress who was known as the “QAnon shaman.” The goal was to “show confidence in the system,” Sherwin told a colleague.

Beyond short written or video statements denouncing the Jan. 6 violence in general, however, neither Wray nor Rosen came out publicly to reinforce that message.

D’Antuono, who was interacting with lawmakers and reporters, told colleagues: “Everybody keeps asking, ‘Where the hell is the FBI?’”

The answer they heard did not instill confidence. Top FBI aides told D’Antuono and Sherwin that Wray wanted to stay on as Biden’s FBI director. They said they would not put the top boss “out there” — in the public eye — because they feared any public comments might spur Trump to unceremoniously fire him.

People close to Rosen and Wray said they preferred to let the local investigators running probes discuss the specifics of their cases.

On Jan. 12, the Justice Department’s public affairs team informed Sherwin and D’Antuono that they would lead the department’s first live on-camera news conference about the investigation.

The pair said investigators were prioritizing the arrest of violent actors, whom Sherwin called the “alligators closest to the boat.”

When asked whether the department would also investigate Trump’s role in urging supporters to come to Washington and inciting the crowd to march on the Capitol, Sherwin again said Trump was not off-limits.

A plan to focus on Trump’s orbit is batted down

By the end of January, with Biden now sworn in as president, the scope of the Jan. 6 investigation was rapidly expanding inside the U.S. attorney’s office. Scores of prosecutors and FBI agents from around the country — most still working remotely because of the pandemic — had been tasked with continuing to identify and charge rioters.

The U.S. attorney’s office and the FBI had specialized teams probing the death of Capitol Police officer Brian D. Sicknick and the police shooting of rioter Ashli Babbitt. Another team, searching for who had planted pipe bombs near the Capitol, had almost 50 FBI agents. A “complex conspiracy” team, a group of 15 prosecutors and agents, zeroed in on members of militia groups who appeared to have coordinated and plotted aspects of the attack, internal briefing documents show.

But a group of prosecutors led by J.P. Cooney, the head of the fraud and public corruption section at the U.S. attorney’s office, argued that the existing structure of the probe overlooked a key investigative angle. They sought to open a new front, based partly on publicly available evidence, including from social media, that linked some extremists involved in the riot to people in Trump’s orbit — including Roger Stone, Trump’s longest-serving political adviser; Ali Alexander, an organizer of the “Stop the Steal” rally that preceded the riot; and Alex Jones, the Infowars host.

In a decade in the U.S. attorney’s office, Cooney, 46, had gained a reputation as a bold prosecutor who took on big cases. In 2017, he argued the government’s bribery case against Sen. Robert Menendez (D-N.J.), which ended in a mistrial and with the Justice Department withdrawing the charges. In 2019, he oversaw the team that convicted Stone on charges of witness tampering and lying to Congress. Cooney signed off on recommending a prison sentence of seven to nine years, but Barr pressed to cut it by more than half after Trump tweeted that it was “horrible and very unfair.” Trump later pardoned Stone.

In February 2021, Cooney took his proposal to investigate the ties with people in Trump’s orbit directly to a group of senior agents in the FBI’s public corruption division, a group he’d worked with over the years and who were enmeshed in some of the most sensitive Jan. 6 cases underway.

According to three people who either viewed or were briefed on Cooney’s plan, it called for a task force to embark on a wide-ranging effort, including seeking phone records for Stone as well as Alexander. Cooney wanted investigators to follow the money — to trace who had financed the false claims of a stolen election and paid for the travel of rallygoers-turned-rioters. He was urging investigators to probe the connection between Stone and members of the Oath Keepers, who were photographed together outside the Willard hotel in downtown Washington on the morning of Jan. 6.

Inside the FBI’s Washington Field Office, agents recognized Cooney’s presentation for the major course change that it presented. Investigators were already looking for evidence that might bubble up from rioter cases to implicate Stone and others. Cooney’s plan would have started agents looking from the top down as well, including directly investigating a senior Trump ally. They alerted D’Antuono to their concerns, according to people familiar with the discussions.

D’Antuono called Sherwin. The two agreed Cooney did not provide evidence that Stone had likely committed a crime — the standard they considered appropriate for looking at a political figure. Investigating Stone simply because he spent time with Oath Keepers could expose the department to accusations that it had politicized the probe, they told colleagues.

D’Antuono took the matter to Abbate, Wray’s newly named deputy director. Abbate agreed the plan was premature.

Sherwin similarly went up his chain of command, alerting Matt Axelrod, one of the senior-most officials Biden installed on his landing team at “Main Justice,” as the DOJ headquarters on Pennsylvania Avenue NW is known. Axelrod, a top Justice Department official during the Obama administration, had been tapped by Biden’s transition committee to help run the department day-to-day until Garland and Monaco could be confirmed.

Axelrod called a meeting for the last week of February with Sherwin, D’Antuono, Abbate and other top deputies. Cooney wasn’t there to defend his plan, according to three people familiar with the discussion, but Axelrod and Abbate reacted allergically to one aspect of it: Cooney wanted membership rolls for Oath Keepers as well as groups that had obtained permits for rallies on Jan. 6, looking for possible links and witnesses. The two saw those steps as treading on First Amendment-protected activities, the people said.

Axelrod saw an uncomfortable analogy to Black Lives Matter protests that had ended in vandalism in D.C. and elsewhere a year earlier. “Imagine if we had requested membership lists for BLM” in the middle of the George Floyd protests, he would say later, people said.

Axelrod later told colleagues that he knew Jan. 6 was an unprecedented attack, but he feared deviating from the standard investigative playbook — doing so had landed the DOJ in hot water before. Former FBI director James B. Comey’s controversial decision to break protocol — by publicly announcing he was reopening the investigation into Clinton’s emails days before the 2016 presidential election — was widely viewed as swinging the contest in Trump’s favor.

Some in the group also acknowledged the political risks during the meeting or in subsequent conversations, according to people familiar with the discussions. Seeking the communications of a high-profile Trump ally such as Stone could trigger a social media post from Trump decrying yet another FBI investigation as a “witch hunt.” And what if the probe turned up nothing? Some were mindful, too, that investigating public figures demanded a high degree of confidence, because even a probe that finds no crime can unfairly impugn them.

All who assembled for the late February meeting were in agreement, with Axelrod making the final call: Cooney’s plan would not go forward.

Aspects of the proposal were reported in 2021 by The Post and the New York Times. But the identity of the prosecutor who pushed for the plan, several of its details and the full story of how it galvanized the Justice Department’s approach to the Jan. 6 investigation have not been previously revealed.

Inside the FBI’s Washington Field Office, buzz about who might join the task force to investigate those around Trump dissipated as word spread that plans for the team had been shelved. In the U.S. attorney’s office, budding investigative work around the finances of Trump backers was halted, an internal record shows, including into Jones, who had boasted of paying a half-million dollars for the president’s Jan. 6 rally and claimed the White House had asked him to lead the march to the Capitol.

About the same time, attorneys at Main Justice declined another proposal that would have squarely focused prosecutors on documents that Trump used to pressure Pence not to certify the election for Biden, The Post found.

Officials at the National Archives had discovered similarities in fraudulent slates of electors for Trump that his Republican allies had submitted to Congress and the Archives. The National Archives inspector general’s office asked the Justice Department’s election crimes branch to consider investigating the seemingly coordinated effort in swing states. Citing its prosecutors’ discretion, the department told the Archives it would not pursue the topic, according to two people with knowledge of the decision.

A prosecutor missteps with talk of seditious conspiracy

The Justice Department didn’t expound at the time on why they turned down the elector probe, but the department made clear its strategy on the riot. Investigators would rely on the traditional method for prosecuting organized crime cases — rolling up of smaller criminals to implicate bigger ones.

To make it work, however, Sherwin began agitating that the government would need a hammer — a charge that would fit the historic nature of the crime and potentially carry decades in prison — to leverage rioters to tell everything they knew about the planning.

On Feb. 19, Sherwin signed an indictment charging nine Oath Keepers with conspiring to obstruct a government proceeding. In meetings, he instructed his top deputies to rapidly draft a superseding indictment charging some of them with seditious conspiracy and present it to DOJ headquarters so they could weigh applying this novel charge.

The Justice Department’s most recent attempt to prosecute using the Civil War-era statute — in the plot to kidnap the Michigan governor — had resulted in embarrassment when a judge tossed it out.

Sherwin, though, had seen the charge as appropriate for Jan. 6 rioters from early on; the main file folder in the U.S. attorney’s office computer system, where line prosecutors shared charging papers and other filings, was named “riots and seditious conspiracy.” Sherwin had begun carrying around a copy of the seditious conspiracy criminal statute, 18 USC 2384: “if two or more persons … conspire to overthrow, put down, or to destroy by force the Government of the United States,” he would read, shrugging his shoulders as though it was obvious.

Sherwin had announced he would step down, making way for Biden to nominate a new U.S. attorney, but he felt so strongly about the seditious conspiracy approach that it figured into his briefing for the new attorney general on Garland’s first day on the job.

Sherwin emphasized that most of the rioters were “stand-alone” actors who got caught up in the mob mentality. He said he was worried prosecutors risked getting bogged down trying hundreds of defendants and recommended the government plead out hundreds of lesser Jan. 6 cases. He stressed that the department should focus on the planners and leaders of the attack and consider using the little-used charge of attempting to violently overthrow their government.

Garland thanked Sherwin but did not reveal his thinking on seditious conspiracy, according to two people familiar with the meeting. It would become the norm in Garland’s buttoned-down Justice Department to share information on only a need-to-know basis.

Addressing staff on his first day, Garland made clear he expected the department to speak through its conduct and court filings. “We will show the American people by word and deed that the Department of Justice pursues equal justice and adheres to the rule of law,” he said.

Garland began arriving at the office each day before 8:30 a.m. and staying until after 7 p.m. When it came to charging decisions, even senior members of his team wouldn’t be read in unless they had an operational reason to be involved. But just 10 days in, his pursuit of a drama-free tenure faced a jolt.

Before returning to Miami, Sherwin agreed to tape an interview with CBS’s “60 Minutes.”

Sherwin suggested to CBS that investigators had obtained enough evidence to prove some rioters engaged in sedition. “I personally believe the evidence is trending toward that, and probably meets those elements,” he said.

Amit Mehta, the federal judge overseeing the prosecution of several members of the Oath Keepers involved in the Jan. 6 attack, watched Sherwin’s March 21, 2021, interview.

On six hours’ notice, he called a video hearing with lawyers on the Oath Keepers’ case and said he was more than a little “surprised” to see Sherwin publicly forecasting future charges on a nationally televised broadcast.

“Whether his interview violated Justice Department policy is really not for me to say, but it is something I hope the Department of Justice is looking into,” Mehta said.

Garland’s top deputies were livid, and the attorney general himself was visibly upset, several people familiar with his reaction said. The attorney general, who was painstaking in preparing his own public remarks, was especially angry at Sherwin for speaking off the cuff. In the hearing with Mehta, John Crabb, chief of the criminal division of the U.S. attorney’s office, said it appeared that “rules and procedures were not complied with” regarding the television interview, and that Sherwin had been referred to the department’s internal affairs office for an ethics probe. Sherwin later told people he thought he’d had the department’s support to tape the interview.

Sherwin heard from a close Justice Department ally that Garland and his deputies now felt boxed into the seditious conspiracy charges — or to tough questions if they didn’t bring them.

The ‘bottom-up’ approach faces internal roadblocks

As the six-month mark from the attack passed, several prosecutors felt increasingly overwhelmed by the growing workload and the extended wait for a permanent U.S. attorney. Prosecutors had begun recommending plea deals for dozens of Jan. 6 defendants but told colleagues weeks would pass without decisions from superiors.

Taking Sherwin’s place until Biden’s nominee could be named and confirmed was Channing D. Phillips, 65, who had twice served as the U.S. attorney in D.C. Phillips expressed to people that he saw his role as a placeholder with limited power to make decisions about Jan. 6 cases.

A permanent replacement was slow in coming, leaving some prosecutors describing the investigation as “rudderless” throughout the summer of 2021. Near the end of July, Biden nominated Graves, a lawyer in private practice who had once led the office’s fraud section.

During that time, Justice officials continued to have conflicting views over whether to pursue people in Trump’s orbit. The debate reached the deputy attorney general’s office.

Monaco, 55, had begun her career as a staffer in Biden’s Senate Judiciary Committee, and had herself worked as a federal prosecutor in the D.C. office. Monaco later rose to be the chief of staff to FBI Director Robert S. Mueller III and subsequently was President Barack Obama’s homeland security adviser. By design, conflicts that arise between the U.S. attorney’s office, the FBI or other branches of the Justice Department are managed by the deputy attorney general’s office.

Monaco warned her aides that the department could not begin probing political actors linked to Trump based on assumptions, according to two individuals familiar with the discussions.

“A decision was made early on to focus DOJ resources on the riot,” said one former Justice Department official familiar with the debates. “The notion of opening up on Trump and high-level political operatives was seen as fraught with peril. When Lisa and Garland came on board, they were fully onboard with that approach.”

Some prosecutors even had the impression that Trump had become a taboo topic at Main Justice. Colleagues responsible for preparing briefing materials and updates for Garland and Monaco were warned to focus on foot soldiers and to avoid mentioning Trump or his close allies.

Late that summer, members of the team leading one of the most high-profile parts of the bottom-up probe into members of the Oath Keepers became frustrated, according to people familiar with the investigation.

Prosecutors wanted to charge Stewart Rhodes, the group’s founder, and several lieutenants with seditious conspiracy. But by fall, the decision remained in limbo. Prosecutors had put Rhodes in their sights since February, when they first referred to him as “Person One” in court records, but still hadn’t arrested him.

“The agents kept asking, ‘What’s going on?’” recalled one of those familiar with the case. “They were ready to pick up Rhodes.”

While FBI agents and line prosecutors wanted to move forward with the charge, a decision was delayed in part because of wariness and debate among some officials inside Monaco’s and Garland’s offices about the risk of sedition charges being overturned on appeal. On top of that, the department still lacked Senate confirmation for two of Biden’s nominees — for U.S. attorney in D.C. and an assistant attorney general for national security, the key supervisors over the investigation.

‘At some point, there was no ladder from here to there’

By fall, some of Biden’s Justice Department nominees began to finally win Senate confirmation.

On Nov. 1, 2021, Matthew G. Olsen was sworn in as assistant attorney general for national security. He was returning to an office he helped build from scratch two decades earlier in the Bush administration, in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

Four days later, Graves, 47, was sworn in as U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia. With that, 10 months after the attack on the Capitol, Garland finally had a permanent team of chief prosecutors in place to guide the investigation.

Olsen, 61, pressed to take on a role in the Jan. 6 casework, which had been led until then by the D.C. U.S. attorney’s office, according to people familiar with the offices at the time. He argued to senior Justice Department officials that an effort to block the peaceful transfer of power was squarely in the vein of what the national security division should be focused on. Monaco agreed. By mid-November, both Olsen and Graves were sitting with D’Antuono, receiving an exhaustive briefing on the state of the Jan. 6 investigations.

The outstanding issue of whether to charge Rhodes and other militia leaders with seditious conspiracy quickly rose to the top of to-do lists for the two new appointees. It had been eight months since Sherwin directed his deputies to raise the idea in a memo to the office of the deputy attorney general.

Since then, with successive new indictments, the government’s evidence had grown stronger.

Graves and Olsen agreed seditious conspiracy charges “fit like a glove” for the alleged criminal acts of Rhodes and key deputies, one individual briefed on the discussion said, but they disagreed on how many people to charge. Olsen urged they charge a smaller number for whom the evidence was stronger.

But investigators were beginning to doubt whether such charges would implicate anyone higher than Rhodes. The bottom-up approach that had dominated nearly a year of the government’s time had not yielded any significant connection to Trump’s orbit.

“It had become clear that the odds were very low that ‘bottom-up’ was ever going to get very high,” said one of those individuals. “At some point, there was no ladder from here to there.”

In the meantime, public knowledge of the actions in the White House that precipitated Jan. 6 was building rapidly. A book by The Post’s Bob Woodward and Robert Costa detailed a memo by Trump legal adviser John Eastman purporting to show a legal basis for Pence to block the certification of Biden’s win on Jan. 6. It called for the vice president to rely on fake slates of electors for Trump from seven states to declare that the election outcome was in dispute. A separate Post story also revealed numerous details of a “war room” that Trump’s closest advisers had been running out of the Willard hotel. The president’s backers used the space as a hub to push members of state legislatures to take steps to support Eastman’s plan, and to urge Pence not to certify the results.

‘I’m not serving subpoenas on the friggin’ Willard’

Inside the U.S. attorney’s office and at Main Justice, prosecutors noticed the developments and grew troubled that the office was still putting too few resources into probing evidence of a broad, Trump-led conspiracy to overturn the election.

Soon after Graves arrived, prosecutors had highlighted the challenges of preparing for rioter trials while also reviewing thousands of hours of video and other digital data for evidence of other crimes.

Graves relayed to Monaco’s office that he planned to stand up a new investigative unit, marking the government’s first major pivot to look beyond the riots. It would be charged with pulling together strands of evidence that investigators had obtained from various rioter cases, including leads on the effort to block the certification.

The office was stretched thin, but among the many documents awaiting Graves’s review when he arrived was one that would transfer a little-known Maryland federal prosecutor to his office.

Thomas Windom, 45, who had won plaudits for investigating a domestic extremist group called “The Base,” had appealed to higher-ups for a move. The deputy attorney general’s office saw the U.S. attorney’s office in D.C. as being in need of help.

Graves put Windom on the new investigations team.

With Graves’s support, Windom soon approached the FBI’s Washington Field Office for additional help.

At a meeting in November 2021, Windom asked D’Antuono to assist in a grand jury investigation, which would include subpoenaing the Willard hotel for billing information from the time when Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani was working with Stephen K. Bannon, Boris Epshteyn and other Trump associates in their “war room.” Stone was staying there around Jan. 6 as well, in a different suite.

D’Antuono was skeptical. The investigative track sounded eerily similar to the Cooney proposal that had been shot down in February, he later confided to colleagues.

“I’m not serving subpoenas on the friggin’ Willard,” D’Antuono told Windom, according to a person familiar with their discussions. “You don’t have enough to issue subpoenas.”

Windom seemed surprised at the flat rejection, according to people familiar with the meeting. D’Antuono offered instead to give Windom full access to the FBI’s trove of evidence about Oath Keeper and Proud Boy extremists involved in the riot. Maybe Windom would find a communication or financial link between rioters and Trump deputies, D’Antuono suggested. The two also briefly discussed fake electors, but the FBI wasn’t ready to move forward on that topic either. Windom thanked him and left.

In the next several weeks, Windom would turn to consider the fake electors and discreetly inquire if another agency might help: the U.S. Postal Service inspector.

At the same time, Graves’s and Olsen’s debate over who to charge with sedition stretched into December, and a growing chorus of former public officials, lawmakers and others criticized Garland for what they saw as a lack of progress on the events that ignited the attack and the roles of Trump and his allies. In one of several examples, three former military generals warned in The Post that the country had to prepare for the next insurrection after not a single leader who incited the violence had been held to account, and they pressed the Justice Department to “show more urgency.”

That fall and winter, a House committee pursuing its own investigation into Jan. 6 conducted interviews with top Trump administration officials. Privately, its chief investigator, Timothy Heaphy, a former U.S. attorney, had alerted prosecutors in the D.C. U.S. attorney’s office to a few details his team had uncovered about Trump’s pressure on Justice Department officials and Pence to block the election results, according to a person familiar with the exchanges. But eye-grabbing news accounts about the committee’s discoveries fueled public criticism that the Justice Department appeared to be lagging.

In late December, amid that wave of criticism, Olsen briefed the attorney general that he had reached a decision on the sedition question: Rhodes and 10 other Oath Keepers would face that rarely brought charge.

Garland had gotten deep into the weeds on the charge in previous briefings, cracking open his statute book and asking numerous questions about the risks of it being overturned. Monaco told the attorney general that Olsen’s team had done a good job stress-testing the case.

Days later, Garland delivered a speech on the eve of the anniversary of the Jan. 6 attack. One line stood out as a promise to his critics: “The actions we have taken thus far will not be our last.”

The FBI investigation is opened

On Jan. 13, 2022, the department indicted Rhodes and 10 other Oath Keepers on charges of seditious conspiracy. It did not quiet the criticism, but instead put a spotlight on signs the Justice Department was not, in comparison with the House committee, working as actively to investigate Trump’s role in the attempted coup.

Politico had reported that week that the House committee had demanded and received documents from several states about fake electors as well as other efforts Trump advisers had taken to pressure state officials ahead of Jan. 6. A wave of news reports and commentary followed, including by MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow, who devoted several nights of her show to reporting on clues that suggested Trump allies ran a coordinated scheme to try to overturn the election.

In the last of those episodes, on Jan. 13, Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel (D) announced that she had referred the matter of fake electors to federal prosecutors — that day. She called the scheme “forgery of a public record” under Michigan law but said the Justice Department would be best suited to prosecute a multistate effort.

About two weeks later, on Jan. 25, Monaco was asked during a televised interview about indications that the fake electors scheme had been coordinated by Trump allies. Monaco hinted there was an investigation underway.

“We’ve received those referrals,” Monaco said on CNN. “Our prosecutors are looking at those. I can’t say anything more on ongoing investigations.”

Law enforcement officers, including some who would be called upon to join the investigation in ensuing months, were taken aback by Monaco’s comments because they had not been told work was beginning, and it was extremely rare for Justice Department officials to comment on ongoing investigations.

Behind the scenes, federal prosecutors in Michigan who received Nessel’s referral were waiting to hear from Monaco’s office about how Main Justice wanted to proceed. National Archives officials were dumbstruck; the Justice Department was suddenly interested in the fake electors evidence it had declined to pursue a year earlier.

One person directly familiar with the department’s new interest in the case said it felt as though the department was reacting to the House committee’s work as well as heightened media coverage and commentary. “Only after they were embarrassed did they start looking,” the person said.

When D’Antuono saw Monaco’s comments, he turned to his deputies and offered a prediction: He would get a call soon from prosecutors asking him to begin investigating electors.

Within a few weeks, prosecutors from the U.S. attorney’s office were again in a meeting with D’Antuono. This time, they did not attempt to link the electors scheme to violence on Jan. 6 but presented it as worthy of its own investigation. D’Antuono told colleagues he saw a path for opening a full investigation, as there was evidence of a potential crime — mail fraud: Documents that appeared fraudulent had been submitted through the mail to the National Archives and signed by people the FBI could trace.

D’Antuono agreed to run the FBI’s multistate investigation.

The process did not go quickly. Lawyers at the FBI and Justice Department launched into what became many weeks of debate over the justification for the investigation and how it should be worded; one time-consuming issue became whether to name Trump as a subject.

With the FBI investigation still not opened, late in March a federal judge presiding over a civil case made a startling ruling: Trump “more likely than not” committed federal crimes in trying to obstruct the congressional count of electoral college votes.

The determination from U.S. District Judge David O. Carter came in a ruling addressing scores of sensitive emails that Eastman had resisted turning over to the House select committee. After reviewing the documents privately, Carter wrote that the actions by Trump and Eastman amounted to “a coup in search of a legal theory” and that “the illegality of the plan was obvious.”

Carter, who was appointed by President Bill Clinton, took the opportunity to express frustration with the pace of the criminal investigation.

“More than a year after the attack on our Capitol, the public is still searching for accountability. … If the country does not commit to investigating and pursuing accountability for those responsible, the Court fears January 6 will repeat itself.”

In April 2022, more than 15 months after the attack, Wray signed off on the authorization opening a criminal investigation into the fake electors plot.

Still, the FBI was tentative: Internally, some of the ex-president’s advisers and his reelection campaign were identified as the focus of the bureau’s probe, but not Trump.

Starting from behind

On June 21, 2022, the House select committee held a nationally televised hearing on fake electors — a topic the committee had, in contrast to the Justice Department, identified early on as a major target for investigation. Testimony revealed what the committee had learned in nine months: The Trump campaign had requested that fake elector documents be flown to D.C. in time to help pressure Pence. The Republican speaker of the Arizona House, Russell “Rusty” Bowers, hushed the chamber, saying Giuliani had contacted him to try to remove Biden’s electors in his state. “He pressed that point, and I said, ‘Look, you are asking me to do something that is counter to my oath,’” Bowers said.

That day, FBI agents delivered subpoenas about electors for Trump to state lawmakers in Arizona. The next day, agents served subpoenas to people who signed documents claiming to be Trump electors in Georgia and Michigan.

Near the end of July, the Justice Department investigation into Trump’s orbit gained new speed.

Graves decided the investigation was becoming too big to operate without a supervisor. The U.S. attorney turned to Cooney, the chief of the public corruption division who had sought to push investigators to begin looking at people in Trump’s orbit almost a year and a half earlier. In an office-wide email on July 28, Graves was vague about Cooney’s new role, saying he was leaving his post to help with “investigatory efforts” related to Jan. 6.

Over the next three months, subpoenas to former Trump campaign and White House officials sought information not only on fake electors but also on Trump’s post-presidential fundraising efforts, hinting at how wide-ranging the investigation had become.

Then, on Nov. 18, Garland abruptly summoned to Main Justice the D.C.-based prosecutors working on the Jan. 6 conspiracy as well as those who had already gathered extensive evidence of Trump concealing classified records at his Mar-a-Lago resort. The attorney general told them that to ensure the appearance of independence into the two probes of a potential Biden rival, he would appoint a special counsel later that day. While the prosecutors could choose their next steps, Garland said he hoped they would continue the work under Smith.

Cooney, who had worked with Smith almost a decade earlier, as well as Windom and roughly 20 others, signed on.

A new chief prosecutor would typically need weeks or months to get up to speed on a high-priority investigation. But Smith issued subpoenas in the Jan. 6 probe after just four days, picking up where the U.S. attorney’s office had left off, seeking communications between officials in three swing states and Trump, his campaign, and 19 advisers and attorneys who had worked to keep him in power.

Smith’s office kept up a steady pace. Prosecutors issued flurries of subpoenas, including demands for records relating to Trump political action committees and his fundraising pitches around supposed election fraud. Smith’s prosecutors also summoned a stream of witnesses for preliminary interviews and testimony before a D.C. grand jury.

In several cases, before the special counsel’s office got in touch, witnesses in the fake electors scheme hadn’t heard from the FBI in almost a year and thought the case was dead. Similarly, firsthand witnesses to Trump’s Jan. 2, 2021, call to Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger — in which Trump asked him to “find” enough votes to win that state — were not interviewed by the Justice Department until this year, after Smith’s team contacted them.

In late May, members of Trump’s legal team began bracing for Smith to bring charges in his other line of investigation. On June 8, a grand jury in Miami endorsed Smith’s evidence that Trump kept and withheld top-secret documents, indicting Trump.

On Tuesday, as Trump pleaded not guilty to those charges in federal court in Miami, Smith’s investigation into efforts to steal the election continued: Michael McDonald and Jim DeGraffenreid, the chairman and vice chairman of the Nevada Republican Party who had signed a document claiming to be electors for Trump, entered the area of the D.C. federal courthouse where a grand jury has been meeting on cases related to Jan. 6.

READ MORE  President Biden shakes hands with Sen. Joe Manchin III (D-W.Va.) after signing the Inflation Reduction Act into law on Aug. 16, 2022. (photo: Demetrius Freeman/WP)

President Biden shakes hands with Sen. Joe Manchin III (D-W.Va.) after signing the Inflation Reduction Act into law on Aug. 16, 2022. (photo: Demetrius Freeman/WP)

Corporate and political opponents of President Biden’s signature economic package have intensified their campaign to kill a broad swath of the law before it takes effect

“The American people won, and the special interests lost,” Biden proclaimed at the time.

Nearly a year later, though, his pronouncement appears in jeopardy: A growing roster of corporate and political foes has started to lay siege to the law known as the Inflation Reduction Act, hoping to erode some of its key provisions before they can take effect.

The latest broadside arrived Friday, when the pharmaceutical giant Bristol Myers Squibb — a maker of the popular blood-thinner Eliquis — sued the Biden administration over its forthcoming program to lower prescription drug prices for seniors. The case marked the third such legal challenge against the U.S. government this month, raising the prospect that older Americans may never see cheaper pharmacy bills.

On Capitol Hill, meanwhile, House Republicans over the past week unveiled a battery of measures that would fund the government — and stave off a federal shutdown — on the condition that Congress revokes billions of dollars in funding for other Inflation Reduction Act initiatives. Separately, GOP leaders also took the first step to terminate tax credits that would expand clean energy and promote electric vehicles, potentially undermining Biden’s plans to reduce carbon emissions.

Some of the legislative efforts face tough political hurdles because Democrats control the Senate and Biden could veto any repeal. But the intensifying opposition underscores the fragility of the president’s agenda under a divided government — and the stakes for Biden’s signature achievement entering the next election.

“They came right out of the gate and went to work,” said Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), the leader of the tax-focused Senate Finance Committee, referring to the law’s opponents. “Everybody’s got a constitutional right to be foolish, but some of this is just economic self-sabotage.”

But Wyden said Democrats would be vindicated in their efforts to defend their accomplishment: “People are already getting relief, they’re getting direct relief in their pockets.”

For Democrats, the adoption of the Inflation Reduction Act last year secured the final component of Biden’s vast economic agenda. It clinched the largest single burst of climate funding in U.S. history, and it introduced a bevy of long-sought health-care affordability programs targeted at seniors, including a cap on insulin prices for Medicare beneficiaries.

Yet the law stopped short of Biden’s original, roughly $2 trillion re-envisioning of the role of government in Americans’ lives, after Democrats failed to overcome their own internal fissures — and unanimous Republican objections. Lawmakers also faced an onslaught of lobbying: The nation’s largest companies and lobbying groups spent a combined $2.3 billion in 2022 to shape or scuttle key components of the emerging law, according to a review of federal ethics disclosures and data compiled by the money-in-politics watchdog OpenSecrets.

Among the fiercest critics was the pharmaceutical industry, which spent more than $375 million to lobby over that period, the records show. Many tried and failed to block Congress from granting the government new powers to negotiate the price of selected prescription drugs under Medicare.

The work to implement that program is underway: The Biden administration is supposed to identify the first 10 drugs it is targeting for negotiation by September, continue the formal process into 2024 and see the prices implemented in 2026, with more drugs to follow in future years. Drug manufacturers that refuse to comply would face steep financial penalties.

Already, though, pharmaceutical giants have filed an early blitz of legal challenges to that plan.

In its lawsuit Friday, Bristol Myers Squibb argued the negotiation process violates the company’s constitutional rights, particularly by forcing it to sell its medicines at steep discounts. The company earned $46.2 billion in revenue last year, including about $11 billion from Eliquis, one of the drugs that could be targeted for Medicare negotiation.

In a separate statement, Bristol Myers Squibb said the Inflation Reduction Act had “changed the way we look at our development programs,” particularly for cancer drugs. It added that any haggling with the government would harm “millions of patients who are counting on the pharmaceutical industry to develop new treatments.”

The lawsuit echoes the arguments raised by another pharmaceutical giant, Merck, which sued the Biden administration earlier this month in a bid to shield its lucrative diabetes and cancer drugs from potential price cuts. The industry’s top lobbyists also have joined the fight: The U.S. Chamber of Commerce — whose dues-paying members include drugmakers AbbVie and Eli Lilly — aligned with local business groups in a June 9 lawsuit to try to block Medicare from bringing the program online.

Some top executives have signaled they expect additional legal challenges on the near horizon. Asked about its plans at a Bloomberg investor conference earlier this month, for example, the chief executive of the drugmaker Biogen responded: “I think we’ll look at it.”

“In Merck’s lawsuit, they talk about an ‘extortion,’ and I think that is accurate,” Chris Viehbacher said earlier in the conversation. “I’m personally not surprised by the lawsuit. I wouldn’t be surprised if you see more.”

The early volleys against the law seemed reminiscent of the reception that greeted Biden’s Democratic predecessor more than a decade earlier, when President Barack Obama had to fend off a dizzying array of insurance industry lawsuits and GOP-led efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act. The core tenets of the law emerged mostly unscathed, but only after years of expensive, complicated legal and political wrangling — which may foreshadow the new fight over drug pricing awaiting the White House.

“When you’re taking on the pharmaceutical industry, you’re taking on one of the most powerful institutions in the country,” said Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), one of the architects of the drug pricing program, who leads the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee. “They are a very, very powerful entity.”

On Capitol Hill, GOP lawmakers at times have sided with the industry, even introducing legislation that would cancel Medicare’s new powers before they take effect. More recently, though, Republicans have labored to neuter the Inflation Reduction Act primarily by revoking its funding.

In two measures to fund the government released Wednesday, GOP lawmakers led by Rep. Kay Granger (R-Tex.), the chair of the House Appropriations Committee, proposed to eliminate about $13 billion meant to boost rural energy, help Americans afford energy-efficient appliances and implement new green building standards.

“It is finally time to be responsible stewards of taxpayer dollars by rescinding these new government giveaways,” said Rep. Andy Harris (R-Md.), a member of the far-right House Freedom Caucus, who leads a key congressional subcommittee overseeing some of the funds.

Other Republicans have tried to narrow or eliminate a bevy of tax credits designed to spur the adoption of cleaner energy, including solar and wind power, even as their congressional districts benefit from an influx of new investment.

Republicans on the House Ways and Means Committee recently advanced a trio of bills cutting taxes for businesses — paid for by repealing key portions of the Inflation Reduction Act meant to boost clean energy and clean electricity development. GOP lawmakers would also whittle down a tax program meant to help Americans purchase new electric vehicles, while eliminating tax credits for used EVs.

Rep. Jason T. Smith (R-Mo.), the chairman of the panel, described the provisions in a statement as “hundreds of billions of dollars in green special interest tax breaks to the wealthy and well connected.” As he finalized the legislation, he pledged the party would repeal “the worst of these handouts.”

The bill marked the second time in two months that Republicans had embraced such a repeal. They initially tried to revoke much of the 2022 law as part of their April bill to cut spending and raise the debt ceiling. Ultimately, Republicans only secured one of their proposed cuts — a rescission of billions of dollars meant to help the IRS pursue unpaid taxes — as part of the debt ceiling deal struck this month between Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.).

“The Republicans are putting themselves in political jeopardy by trying to attack the IRA, the provisions of which are incredibly popular,” said Ben LaBolt, the communications director at the White House.

The flurry of activity on Capitol Hill came as the Biden administration finalized rules that would allow local governments and nonprofits to take advantage of new clean energy tax breaks. John D. Podesta, the senior adviser to the president for clean energy, predicted to reporters that the policies could open the door for local officials to electrify their own vehicle fleets, build local rooftop solar networks and deploy other projects that reduce emissions.

“We’re already seeing a massive response from the private sector,” he said.

Some of those investments have greatly benefited Republican-held congressional districts. To highlight the stakes, the left-leaning Center for American Progress Action Fund found in an analysis released Friday that roughly 100,000 jobs in these communities could be affected if lawmakers wiped out climate provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act.

The figure represents a tally of announcements from companies that make electric vehicle batteries, solar panels and fuel cells, some of which were made before and after the passage of the law, as firms sensed a business opportunity.

In a fierce legislative debate, some Democrats echoed that view. Rep. Richard E. Neal (D-Mass.), the top party lawmaker on the Ways and Means Committee, on Tuesday criticized the GOP approach as a “scam” before touting the Inflation Reduction Act as “wildly popular with the American people, including the Republican base.”

READ MORE  Receding water levels are seen this month along the Dnipro River in Ukraine’s southeast, with the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, which is occupied by Russian forces, in the background. (photo: Daniel Berehulak/NYT)

Receding water levels are seen this month along the Dnipro River in Ukraine’s southeast, with the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, which is occupied by Russian forces, in the background. (photo: Daniel Berehulak/NYT)

Source: Interfax-Ukraine, quoting Petro Kotin, Head of Energoatom, during his visit to a nuclear power plant on Wednesday, 14 June

Quote from Kotin: "ZNPP staff can initiate a cold shutdown of Unit No. 5 in theory, but they can’t do it in practice, because the Russian forces are controlling the situation. The [Russian-appointed] management of the power plant has so far failed to comply with the order issued by the State Nuclear Regulatory Inspectorate of Ukraine (SNRIU), but the information we obtained indicates that they might be preparing to do so."

Details: Kotin said there was hope that the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) mission and IAEA Director General Rafael Grossi would be able to convince Russian occupation forces to ensure the cold shutdown of the power unit.

"Cold shutdown is the safest mode for a power unit to be in under any circumstances," Kotin added.

He also explained that the SNRIU’s decision, issued on 8 June 2023, to implement the cold shutdown of the last of the ZNPP’s functioning power units (which is currently operating in what is known as the hot shutdown mode) was a logical measure in light of the draining of the Kakhovka Reservoir following the explosion at the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Plant (HPP), which was the primary water source for the ZNPP splash pools.

Ukraine’s Energy Minister Herman Halushchenko said that the blowing up of the Kakhovka HPP and the draining of the Kakhovka Reservoir could have put the ZNPP in critical danger if the power plant was still operational.

"Grossi knows about this issue, the fact that the cold shutdown has not been implemented. I hope that when he is there he will be able to exert his influence accordingly. But for now, this is not critical. The crucial question I have now is this: How are we going to bring the power plant back online after its liberation? We will have to find a new way of cooling it. This is another difficult challenge we face," the minister stressed.

Background:

- On 14 June, the SNRIU said that Russian occupation forces at the ZNPP have been obstructing the transfer of Unit No. 5 to a safe cold shutdown, which the SNRIU ordered on 8 June to ensure the safe operation of the ZNPP as water levels in the Kakhovka Reservoir, the primary source of water for the ZNPP splash pools, are falling following the explosion at the Kakhovka HPP.

- IAEA Director General Rafael Grossi began his visit to Ukraine on 13 June, meeting with President Volodymyr Zelenskyy in the evening. He arrived at the ZNPP on 15 June, after his visit to the ZNPP had been postponed due to safety concerns.

READ MORE  Petrochemical storage tanks are seen at the Enbridge Edmonton Terminal, near Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, October 7, 2021. (photo: Todd Korol/Reuters)

Petrochemical storage tanks are seen at the Enbridge Edmonton Terminal, near Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, October 7, 2021. (photo: Todd Korol/Reuters)

U.S. District Judge William Conley issued the order on Friday in Madison. The judge's action came just over a month after the Bad River Band told him an immediate shutdown was needed following heavy spring rains that eroded a riverbank protecting the pipe. The pipeline carries 540,000 barrels of oil per day from Canada through the Great Lakes region.

An Enbridge spokesperson said on Saturday the company plans to appeal the judge's order.

In the ruling, Conley said a sudden shutdown could lead to oil shortages and price hikes in the United States, adding that "given the environmental risks, the court will order Enbridge to adopt a more conservative shutdown and purge plan."

Enbridge said in court filings ahead of the judge's action that a hasty shutdown of the pipeline was unnecessary and would cause "extreme market turmoil." The company has proposed re-routing the pipeline around the tribal reservation, but has not received federal approvals to do so.

Representatives for the tribe did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The tribe has said a breach in the pipeline along the 12-mile (19 km) segment that runs through the reservation could pollute important fishing waters, wild rice habitat and potentially underground aquifers.

The tribe sued Enbridge in 2019, arguing that riverbank erosion threatened a "looming disaster" that warranted removal of the pipeline and saying that the company no longer had a legal right to operate on the property after pipeline easements allowing it to use the land expired in 2013.

Conley ruled last year that the pipeline was trespassing on the land but stopped short of ordering a shutdown due to public and foreign policy concerns. The judge in November said significant erosion that could cause a rupture was unlikely, but told the parties to develop a shutdown plan anyway.

READ MORE  A young girl and her mom sit in an ESL class at Capital District Latinos in Albany, N.Y. earlier this month. (photo: Lexi Parra/NPR)

A young girl and her mom sit in an ESL class at Capital District Latinos in Albany, N.Y. earlier this month. (photo: Lexi Parra/NPR)

They requested asylum at the Texas border.

They lived in two shelters there. In Brownsville, then in San Antonio. They lasted four days with a relative in Boston, before he said there was no room. They wound up in New York City shelter, where Coronel says they were 12 people per room. When officials told them Albany would be less crowded, they immediately agreed to go.

"It's a lot of instability," says Coronel. "But the situation in Venezuela has gotten impossible. You can't walk down the street without a government official shaking you down for money every couple of blocks. We just want to work and live in peace."

New York City has received over 60,000 migrants and asylum seekers in the last year or so. Officials there say they are overwhelmed, and have begun sending people to nearby communities.

It's a policy that is increasingly concerning to advocates. While places like Albany, a sanctuary city, have welcomed new arrivals, many localities have expressed hostility towards immigrants.

"In these non-sanctuary cities, folks are very much in fear of getting deported," says Micky Jimenez, executive director of the non-profit Capitol District Latinos. "If they work there, they go to work, and go back home. They are very much afraid."

Local non profits like hers are doing their best to step up, but they say they, too, are stretched thin.

New arrivals, and the lack of resources to help them, have caused tension

New York has become a battle ground for immigration, and relations between the city, neighboring towns and activists have become increasingly acrimonious.

"They're all sanctuary cities until they have to be sanctuary cities," says Peter Crummey, a Republican and town supervisor of Colonie.

Located 20 minutes away from Albany, the village of Colonie is not a sanctuary city. So Crummey says he was blindsided when, on Memorial Day weekend, New York City sent a bus with 24 migrants to his town. He's suing New York, but he says he's also infuriated at the lack of guidance from the Biden administration and Congress.

"The federal government has created chaos in our country, by not responding and making a plan for these folks," he says. "The solution lies at the feet of the federal government. Because immigration is decidedly a federal issue. It's not a town issue. Or a village issue."

It's a sentiment that is echoed in communities throughout the area. Some residents even say they worry about the new arrivals exacerbating existing tensions.

Efren Rojas works as a mechanic in Rockland County, N.Y., about two hours south of Colonie.

"I've always overheard people talk badly about Hispanics," he says. "No matter where you come from, your family can be here for hundreds of years, they will still see you as from another country. You're skin is a little dark, and you will make people uncomfortable."

Rockland's population is 78% white and nearly 19% Latino, according to 2022 U.S. Census figures. It also recently received migrants and asylum seekers from New York City. It was granted a temporary restraining order to keep any additional migrants from being placed there. The New York Civil Liberties Union has filed suit against the county.

Rojas says he's not opposed to folks migrating, after all, he did it from Mexico when he was a teenager. He was undocumented for years - he now has his papers. But he thinks the federal government should not be offering them assistance.

"I was always scared that if I asked for help, I could get deported. I'm not resentful about that. I came to work, not to ask for help," he says. "They're abusing the system."

At a nearby super market parking lot, Anthony Gerome says he's concerned about the costs of taking people in. He points out that the U.S. economy is not great right now.

"We can't afford it," he says. "We have too many people in the United States that are U.S. citizens, veterans of war and so on that need our help desperately."

Gerome says he feels compassion for people asking for asylum in his area but, he says people in this town did not sign up to take on and take care of asylum seekers.

"People come to the suburbs thinking they're gonna have a better life and a safer environment. Because it's not only a fiscal problem. It's a safety issue. We don't know who these people are," Gerome says.

Actually, people who have entered the U.S. recently as migrants or asylum seekers have been screened by immigration authorities, and allowed to pursue their cases from within the U.S.

But, Gerome says, he doesn't trust it.

Looking for help from overwhelmed systems

Hostility toward immigrants in some of the towns where they are being bused is alarming to many advocates and lawmakers. During a judicial hearing over Rockland and Orange County's executive orders banning any more migrants from coming in, White Plains federal judge Nelson Román said the bans were reminiscent of "Jim Crow law. Not that I'm saying it is."

Dan Irizarry is Chairman of Capitol District Latinos and acknowledges the challenges. "We can greet them, we can clothe them, we can feed them to a degree," Irizarry says. "But then what happens to them once they try to assimilate into this local area that's not really friendly to them at all?"

Throughout New York state, organizations like his have been stepping up to help. The list of comprehensive services includes a food pantry, English classes, clothing donations and even partnering with a local hospital to offer mammograms.

But the program's director, Micky Jimenez, estimates the number of people they serve has increased by 70% in the last year.

"We need funding. There is no way that we can continue to provide the level of services that we are providing," Jimenez says. "You know we're blessed with the incredible volunteers we have. But they're getting tired, too."

A few miles south, the community organization Albany Victory Gardens also provides help to migrants. "It's America. You're supposed to help each other out" says Linda Pasqualino as she waited to get her fruits and vegetables. "My grandmother came here from Czechoslovakia when she was seven. This is all politics; they're using people as weapons."

Albany Victory Gardens President Mitchell Keyes says he doesn't understand the outrage. He says, anyone who walks through Albany will notice the "Help Wanted" signs. "There's a lot of jobs out here. And ain't nobody taking them. So if an immigrant comes and signs for a job he's qualified for, why not hire him?" he asks.

It's not that easy. Johnson Coronel, the 26-year-old Venezuelan who recently arrived, says he's noticed those stores with the "Help Wanted" signs Keyes mentioned. Sometimes he and his friends from the shelter go into those stores, asking for work.

They are told no one speaks Spanish, or they are asked for a work permit — which no one has yet, Coronel says. With immigration courts backed up, getting a permit to work could take as many as two years.

At least for now, he is stuck. Again. No income, living in the shelter, in a sanctuary city surrounded by towns where a lot of people have made it clear they do not want migrants like him there.

"We're tired," Coronel says. "One day we're here, the next day we're there. It's time to say, 'This is it. We're staying here. This is home.' "

READ MORE  Khadijatou Bah cooks a meal in M’Bouroré, Guinea. (photo: Kathleen Flynn/ProPublica)

Khadijatou Bah cooks a meal in M’Bouroré, Guinea. (photo: Kathleen Flynn/ProPublica)

The World Bank Group enabled the devastation of villages and helped a mining company justify the deaths of endangered chimps with a dubious offset.

Chimps had long encroached on Kagnèka, her farming community of about 350, but there was a time when residents could beat on gongs to scare them away. That changed about six years ago when a mining expansion drained streams and razed trees, driving the displaced primates into a desperate struggle with the village over food and water. Kagnèka’s crops became an open buffet. And the chimps began guarding the river so aggressively that Bah no longer felt safe bringing her two small children, or washing her clothes on the bank, or even going alone.

One afternoon in February, an enormous nest loomed above — a mound of bent branches where a chimpanzee would have recently slept. Bah used a gourd to scoop water into a bucket to balance on her head, then rushed home with neighbors, past trees stripped bare of bananas.

What Bah and her neighbors didn’t know is that they — and the chimps who now terrorize them — are the accepted collateral damage in a deal brokered by the globally respected World Bank Group, whose priorities include reducing poverty, protecting the environment and preventing the spread of deadly diseases.

The idea seems noble: In parts of the world rich in natural resources, but struggling economically, the bank sets up arrangements known as biodiversity offsets. Mining or gas companies, for example, can build environmentally ruinous projects in areas even if they are home to endangered species as long as the companies protect the same species elsewhere or take other steps to “compensate” for the ecological damage.

When the World Bank Group funds their operations, it allows the companies to publicly portray themselves as ecologically responsible. In some cases, the name-brand companies that eventually use their products can do so as well.

The World Bank Group has backed such projects for decades; its arm that works with private companies, the International Finance Corporation, has funded at least 19 with biodiversity offsets.

IFC standards are influential and considered the best in the world.

But in practice, ProPublica found, projects brokered by the World Bank Group can fall short of their idealistic goals. The one in Guinea has left a trail of hunger, displaced and broken families, decimated ecosystems and conditions ripe for the spread of deadly contagions.

And the deals themselves sometimes fall apart, with the land used as an offset falling prey to another company or disaster — with few consequences for the company or its lenders.

The deal in Guinea began like many others: Compagnie des Bauxites de Guinée sought funding to expand its mining operation. The company estimated its project would lead to the deaths of up to 83 critically endangered western chimpanzees; if they weren’t killed in the demolition, the displacement would decimate the population over time, as females stopped reproducing due to stress and males injured or killed one another fighting over shrinking territory.

A nearby company that also needed money predicted its mine would result in the loss of twice as many chimps. The IFC helped the companies establish Moyen-Bafing National Park some 200 miles away, where thousands of other chimps already lived. Bolstering and protecting this population, the idea went, would make up for the loss of the others.

But the companies’ consultants underestimated the chimp death toll, primatologist Genevieve Campbell and her colleagues later found in an independent review of the offset. The consultants had assumed some of the chimpanzees near the mines would survive, but the reviewers concluded the development would contribute to the eventual deaths of all the chimpanzees — about 180 to 400.