Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Former president, who faces 37 charges related to retention of secret documents, addresses Republican conventions in Georgia and North Carolina

The former president took the stage at state Republican conventions in Georgia and North Carolina where he lashed out against the Department of Justice, the FBI and the Biden administration, called his recent indictment “a travesty of justice” and repeated unsupported conspiratorial claims that Joe Biden had stashed secret documents in the Chinatown neighborhood of Washington DC.

“We got to stand up to the … radical left Democrats, their lawless partisan prosecutors … Every time I fly over a blue state, I get a subpoena,” said Trump at the onset of the meandering speech that attempted to bridge his legal troubles with campaign promises.

“I’ve put everything on the line and I will never yield. I will never be detained. I will never stop fighting for you,” he added.

He went on to launch a tirade against federal officials, saying, “Now the Marxist left is once again using the same corrupt DoJ [justice department] and the same corrupt FBI, and the attorney general and the local district attorneys to interfere … They’re cheating. They’re crooked. They’re corrupt. These criminals cannot be rewarded. They must be defeated. You have to defeat them.

“Because in the end, they’re not coming after me. They’re coming after you and I’m just standing in their way,” he said.

Trump accused the Biden administration of weaponizing the justice department, calling the recent indictment “ridiculous and baseless” and “among the most horrific abuses of power in the history of our country”.

He went on to add that “the only good thing about [the indictment] is it’s driven my poll numbers way up”.

Trump repeated his baseless attacks against his former opponent Hillary Clinton, whom the state department investigated for several years over her use of private email before it found “no persuasive evidence of … deliberate mishandling of classified documents”.

He also lashed out at Joe Biden over the classified documents from his time as vice-president and senator which were found in his office in Washington and his Delaware home.

“Nothing happened to Crooked Joe with all that … He has so many classified documents … This is a sick nest of people that needs to be cleaned out immediately,” said Trump as the crowd in Georgia cheered fervently.

Trump also brought up his former vice-president and now presidential opponent Mike Pence, who also had marked documents discovered in his Indiana home.

“They looked at Mike Pence. He had classified documents, no problem,” said Trump.

While Biden and Pence turned over the marked documents as soon as they were discovered and allowed their lawyers to look through their properties, Trump has been accused of deliberately concealing boxes of records from his attorney, the FBI and the grand jury, according to the latest indictment.

On the plane to North Carolina after his Georgia speech, Trump told Politico he would not drop out of the presidential race, even if he was convicted on the latest charges. “I’ll never leave,” he said.

When asked if he would pardon himself should he become president again, he said: “I don’t think I’ll ever have to … I didn’t do anything wrong.”

Pence also appeared at the North Carolina event, marking the first shared venue with his former boss since the ex-vice president announced his own campaign. He condemned the “politicization” of the Justice Department and urged attorney general Merrick Garland “to stop hiding behind the special counsel and stand before the American people” to explain the basis for the federal investigation into Trump.

In an interview with the Associated Press after his speech, Pence said he had read the indictment but repeatedly declined to share his personal reaction to its contents or to criticize Trump.

“The very nature of a grand jury is that there is no defense presented,” Pence said. “That’s why I said today I’m going to urge patience, encourage people to be prayerful for the former president, but also for all those in authority and for the country going forward.”

In North Carolina, Florida governor and Trump rival Ron DeSantis didn’t mention Trump by name but compared his situation to that of Clinton.

“Is there a different standard for a Democratic secretary of state versus a former Republican president?” DeSantis said. “I think there needs to be one standard of justice in this country ... At the end of the day, we will once and for all end the weaponization of government under my administration.”

On Saturday night, Trump said he would endorse lieutenant governor Mark Robinson in the race for governor of North Carolina. Trump said he would save his formal endorsement for another time but told Robinson from the stage, “You can count on it, Mark.” He referred to Robinson as “one of the great stars of the party, one of the great stars in politics.”

Robinson has attracted a reputation as a sharp-spoken social conservative, telling a church in 2021: “There’s no reason anybody anywhere in America should be telling any child about transgenderism, homosexuality, any of that filth.”

Trump’s two speeches had been planned before the justice department indicted him on Thursday evening with 37 criminal charges regarding his alleged illegal retention of classified government documents after leaving office in 2021.

The sweeping indictment which was unsealed on Friday accuses Trump of mishandling classified documents as well as obstructing justice, making him the first US president to be federally indicted.

Trump is expected to appear in a federal court in Miami on Tuesday and may face prison if convicted.

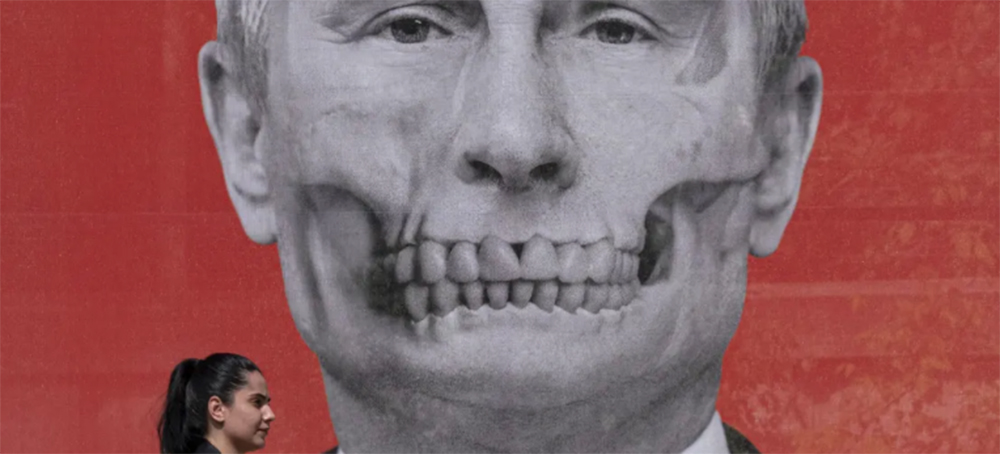

READ MORE With the Russian army on the back foot, the dictator looks less secure in the Kremlin than ever. (photo: Vadim Ghirda/AP)

With the Russian army on the back foot, the dictator looks less secure in the Kremlin than ever. (photo: Vadim Ghirda/AP)

Opposition leaders have begun to plan for the end of the regime – and some believe it is now inevitable

Nearly 300 exiled Russian opposition politicians and activists gathered to discuss these questions in the European parliament earlier this week, the congress coming as news broke of the Nova Kakhovka dam destruction, the latest grim episode in Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine.

The Brussels forum, convened by four MEPs, was the first such gathering to be given official status by a European parliamentary body, as some in Europe start thinking about how the contours of a post-Putin Russia would look.

“This is the first time that someone is speaking about the possibility of post-Putinism. Three months ago, this wasn’t possible. EU countries thought that Putin would be president for years and years if not decades and decades … Now, the perception has changed,” said Bernard Guetta, a French MEP who was one of the forum’s organisers.

Mikhail Khodorkovsky, formerly the richest man in Russia before he was jailed for a decade in 2003, said that simply changing Putin for another person from his system would not make any difference.

“This regime should be destroyed,” he said during the opening session. “There is no other road to a peaceful normal future for Russia and for Europe and the whole world.”

The Russian opposition has been saying this for years, and it can often sound like wishful thinking. But with the Russian army on the back foot, drone strikes and military incursions hitting inside Russia and infighting between the elites spilling into the public domain, some in Europe are also beginning to wonder if Putin is as secure in the Kremlin as they had thought.

What a post-Putin Russia would look like is a matter of debate, however. Andrius Kubilius, the Lithuanian MEP and former prime minister who was the conference’s main organiser, said it was still a minority view among European politicians that real democratic change could come to Russia, but he felt it was an important argument to make for the sake of both Russia and Ukraine.

“If big European capitals won’t believe in a possibility of a democratic Russia, which I admit is not so easy to believe at this point, you think either … the same regime will stay in power for ever … or Russia will collapse into total disaster,” said Kubilius.

If western politicians believed a complete Ukrainian military victory would mean the collapse of Russia into an even worse dictatorship or civil war, they “then become scared of Ukrainian victory,” he said.

Some participants of the conference had left Russia more than a decade ago, while others had left after Putin launched his all-out invasion last February. They travelled to Brussels from Berlin, Vilnius, Paris, Tbilisi and many other cities that have become hubs for Russian exiles.

Many participants suggested the collapse of the Putin regime was a matter of when, not if, adding that while the initial post-Putin era might involve a power grab by those in the inner circle, things could soon change quickly.

“Any post-Putin ruler would be significantly weaker in terms of legitimacy and public authority … the regime will try to hold on to power but will not last for long,” said Vladimir Milov, a longstanding opposition politician who was deputy energy minister early in Putin’s rule. “That’s when we need to apply pressure for people to speak up,” he added.

The only Ukrainian at the forum was Oleksiy Arestovych, who resigned in January. He was a former senior adviser to President Volodymyr Zelenskiy. Arestovych dismissed the view – common in Ukraine – that the Russian opposition should be ignored as it shares the imperial mindset of the Kremlin, as “political shortsightedness”. He said it was important to think about how to change the regime in Russia, rather than simply hope for Russia’s disintegration.

“There is no such thing as other people’s freedom. While Russia isn’t free, we are not fully free either because at a minimum it means … attempts to carry out a new war are always possible. So even from the point of Ukraine’s security we have to talk about the liberation of Russia,” he said.

For all the fighting talk at the forum, the Russian opposition remains divided over how best to cooperate. Representatives from the foundation of jailed opposition politician Alexei Navalny, the best known opposition leader, were a notable absence from the Brussels conference. They have boycotted many similar events, believing them to be pointless talking shops.

Also absent was Ilya Ponomarev, a former MP who was the only Russian parliamentarian to vote against the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and subsequently fled to Kyiv, where he has taken Ukrainian citizenship. He now claims to have links to partisan movements inside Russia and the armed units who have carried out cross-border incursions into Russia from Ukraine in recent weeks.

“The organisers do not want even a flavour of armed resistance,” Ponomarev said in a telephone interview. On Thursday, he began his own forum in Warsaw, dedicated to creating legislation for a post-Putin transition period.

On the sidelines of the Brussels forum, many admitted privately that some of the discussions about how to act in a hypothetical future Russia sounded like premature wishful thinking. But some also noted how quickly things might change in the country, and the importance of being ready.

“We have this habit of 20 years of stability and we can hardly wrap our heads around the fact that the system can be weak and eroding … but the erosion is visible,” said political scientist Ekaterina Schulmann.

“Those within the country will have the advantage … But those who move fast enough can also play a role. And of course everyone will have a chance to lose their heads as well.”

READ MORE  Soldiers with 2nd-319th Airborne Artillery Unit listen to remarks from the 18th Airborne Corps commander, Lt. Gen. Christoper Donahue, before a redesignation ceremony assigning the name Fort Liberty to what was formerly called Fort Bragg on June 2, 2023, in Fayetteville, North Carolina. (photo: Melissa Sue Gerrits/Jacobin)

Soldiers with 2nd-319th Airborne Artillery Unit listen to remarks from the 18th Airborne Corps commander, Lt. Gen. Christoper Donahue, before a redesignation ceremony assigning the name Fort Liberty to what was formerly called Fort Bragg on June 2, 2023, in Fayetteville, North Carolina. (photo: Melissa Sue Gerrits/Jacobin)

While the armed forces carry out the mission of US imperialism, millions of working people sit at the heart of that machine, drawn to become soldiers by the promise of economic stability. A Left looking to rebuild links with the working class can’t avoid them.

This makes the lack of engagement between the US civilian left and soldiers and veterans seem striking, and even a bit alarming. While the armed forces carry out the mission of US imperialism, millions of working people sit at the heart of that machine, many of whom enlisted out of economic desperation and are skeptical of power and authority. Moreover, once enlisted, grievances among rank-and-file soldiers pile up — over racism, misogyny, poverty, and the military’s reckless attitude toward troop health and safety.

This chasm is all the more puzzling given the Left’s proud history of military organizing and of veteran leadership in historic US worker and social movements. From the civil rights movement to the Vietnam antiwar movement to the 1970s rank-and-file worker rebellion, GIs, and veterans have been pivotal actors in fights for justice, peace, and equality.

Moreover, as Suzanne Gordon, Steve Early, and Jasper Craven show in their informative new book, Our Veterans: Winners, Losers, Friends, and Enemies on the New Terrain of Veterans Affairs, the military apparatus today is a contested political space with organizing inroads for the Left and labor movement.

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), which provides a model not-for-profit health care system, is under constant attack by corporate interests and their bipartisan lackeys. Active-duty troops, the overwhelming majority of whom never see battle, face harsh working conditions, health and safety disasters, precarious economic existences, and often intense abuse and bullying. While far-right forces try to recruit disenchanted soldiers and vets from within, Koch-funded elites seek to privatize and profit off the military’s services. Moreover, the armed forces are a pipeline for unions, with many veterans among the ranks of the postal workers, communications workers, and more. Indeed, say Gordon and Early, veterans have the potential to be a vital part of the leadership of a revived labor movement.

The book is an excellent and nuanced introduction to the contours and politics surrounding military labor and veterans’ affairs. For a socialist left looking to rebuild links with the US working class, it’s a vital read.

In this exclusive interview, Derek Seidman talked to Suzanne Gordon and Steve Early about their new book and the many issues it raises about the contentious terrain of veterans’ politics, the struggle to save the VA, the bridges between the military and the labor movement, and much more. Gordon is an award-winning journalist and author who has worked on veterans’ issues for a decade, and Early is a longtime labor organizer and author of several books.

Derek Seidman: To start off, can you say a little bit about why you decided to write this book?

Suzanne Gordon: I’ve been writing about veterans’ issues for about ten years. I helped found a group called Veterans Health Care Policy Institute, which fights against VA privatization. Steve has often been my editor, so for us the book was a logical consequence of that work, but also of the fact that we’ve both been antiwar activists since our college years, which is a very long time. Issues around the military and foreign policy really shaped our political coming of age. Fighting against, first, the Vietnam War, and then all the subsequent US military ventures, has really been part of both of our identities.

Steve Early: I first came into contact with veterans as a cadet in the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) at Middlebury College in the fall of 1967. I had been persuaded by the draft that, if you had to go into the military, it was best to do so as an officer. It took me one semester — going to the firing range, marching around and taking orders, being instructed by a recently returned Vietnam vet who seemed quite unhinged by his experience — to conclude that a better way of dealing with the Vietnam War was to end the draft, kick ROTC off campus, and stop the war so that nobody would have to go fight in such a costly and tragic conflict.

I spent the rest of my time in college doing antiwar organizing. I worked for the American Friends Service Committee for a year as a statewide antiwar organizer in Vermont. When I got involved in the labor movement a few years later, I met many younger Vietnam veterans who had just come home and gotten jobs as coal miners in West Virginia and Kentucky, and they became militant dissident members of the United Mine Workers (UMW). They were part of a reform movement in the early 1970s that overthrew the corrupt, murderous old-guard leadership of the UMW. This created a real opening for a few years for revitalization of the entire labor movement. At the time, the UMW had two hundred thousand members and was much bigger and more highly visible than it is today.

I saw that multiple generations of veterans from World War II, the Korean War, and particularly Vietnam could be catalytic influences in the labor movement — an experience that was confirmed later when I met the great Tony Mazzocchi, a visionary leader of the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers International Union (OCAW). Mazzocchi was a combat veteran and survivor of the Battle of the Bulge. He came back and benefited, along with fifteen million other soldiers, from the original GI Bill. He became a lifelong advocate of free higher education for all, based on the GI Bill model, and of single-payer health care based on the VA healthcare system. He was a tireless campaigner for job safety and health legislation, including the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1972. He later helped found the Labor Party. He was another example of someone who served in the military, came out, and then got involved in union work and was tremendously influential as a force for progressive change.

So I think there’s a lot of overlap between veterans’ affairs and labor issues that is often ignored but that we highlight in the book. As someone who has spent fifty years in the labor movement — working with veterans who were stewards, local officers, strike activists, and organizing committee members — this connection kind of jumped out to me.

Derek Seidman: You begin your book by surveying the hazardous working conditions that service members face. The level of harm and precarity that military personnel endure — and not at all just combat personnel — was really striking. Can you talk about some of this, especially the severe health problems veterans live with? And can you also specifically address the pervasive sexual harassment and sexual assault that occurs in the miliary?

Suzanne Gordon: There are so many issues that I think the Left should get involved with when it comes to the military. Because it’s the military, I think there’s a lot of confusion or ambivalence toward this issue. What’s unique about our book is that we look at military service as not just service, but a job. I think the harping on “service and sacrifice” leads many people to ignore the fact that there are a lot of sacrifices that service members are asked to make — not sacrificing their lives, but sacrificing their health — that have nothing to do with the risks of combat. That’s because the Department of Defense (DOD) is one of the most reckless employers on the face of the earth when it comes to the safety of its workers, i.e, service members.

Most military service members never see combat. Only about 10 percent of actual service members see combat, and even that 10 percent that is in combat zones is not all shooting or being shot at. There are all kinds of things that the military could do to prevent the kind of injuries that service members suffer from, but in fact they do the opposite.

It starts with indoctrination, which is too often a brutal training regimen where people are assaulted emotionally and physically, and sometimes sexually. Younger cohorts of veterans have many more muscular, skeletal, shoulder, neck, and back problems from all the extreme exercise routines that they go through. There’s a tremendous amount of bullying that’s tolerated, and that leads to post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental health conditions. Around 126 military bases are contaminated with toxic chemicals. You have moldy housing that service members and their families are housed in. They’re not paid enough. And then they incur a lot of debt because the military lets predatory lenders — car dealers, for example — on Navy ships and on bases, and they get people into debt, which has been shown to increase the risk of suicide.

Then there’s military sexual trauma. This is a misogynistic, bullying environment. It impacts mostly women, though there are some men who suffer from military sexual trauma, which can include everything from harassment, to rape, to murder. The military is just not doing enough about this — in fact, it actually punishes women who report rape. They’ve fought every effort to create independent prosecutors and investigators — legislation that was proposed.

Then there’s the scandal of how the military fails to protect troops that are in combat. They bought helmets that were supposed to protect soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan from improvised explosive devices, but they neglected to put in pads so that the helmets fit well enough. The service members in those combat zones had to go to some not-for-profit to get the helmets to fit. Then there was a scandal about the earplugs they hired 3M to produce, which were faulty. The earplugs were supposed to protect them from hearing loss and tinnitus, but they didn’t work. You also have this scandal of hiring KBR, formerly Kellogg, Brown … Root — known during the Vietnam War as Burn … Loot — to dispose of garbage in combat zones. They basically chose a fifteenth-century mechanism of garbage disposal, which is just burn everything — lithium batteries, corpses, animals, chemicals. So now, there’s now an estimated 3.5 million veterans who have been potentially impacted by these toxic exposures, breathing in this stuff 24-7.

Steve Early: What we try to highlight is that military service, stripped of the flag-waving and all the patriotic trappings, is a job. It’s work, in a highly unregulated industry, with no protective labor legislation, and no antidiscrimination statutes that you can invoke. For soldiers on active duty, in the US military, it’s a felony for them to join a union or go on strike. This is a legal straitjacket that dates back to the era of the GI antiwar movement during the Vietnam War, when the need for a “servicemen’s union” was widely discussed among uniformed foes of the war.

Half the military workforce today is between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five, so we’re talking about young people. It’s a demographic without much prior full-time work experience. Men and women, without many other civilian job opportunities, who are looking for stable employment, steady pay, health insurance coverage, subsidized housing, food, and clothing. The promise of job training is a very big part of that enticing package and much emphasized by military recruiters. Where else, outside of much-harder-to-get-into building trades apprenticeship programs, do you get paid to learn new skills?

Then there’s the longer-term promise that you will have affordable health care when you get out and that you’ll have access to affordable higher education through the GI Bill. This legislation, in its modern-day form, has enabled at least a million post-9/11 veterans to avoid becoming deeply indebted, although many still have to do some borrowing to meet their college or university expenses — and thousands have been fleeced by shady for-profit institutions that hoover up a huge amount of GI Bill money in return for diplomas of sometimes questionable value.

That’s why people go into the military. And just think what the very different results for our society would be if the federal government, instead of putting 20,000 recruiters in the field and having 1,400 hiring offices and programs in 3,500 high schools, offered training and job opportunities as health care workers or teachers or construction workers? Even with a recruitment budget of $1.5 billion a year, the Pentagon would have great difficulty competing with that because poor and working-class young people would take these other pathways to good jobs and benefits and productive careers.

There’s a lot of organizing work that can still be done among some citizen soldiers. Our union, the Communications Workers of America (CWA), down in Texas supports the Texas State Employees Union, a longtime open-shop, public sector union. They’ve now created a Military Caucus and signed up members of the Texas National Guard who are concerned about workplace issues and problems. They’re upset about their Republican governor stripping them of tuition assistance and cutting other benefits and deploying them, on an open-ended basis, to “protect” the US-Mexico border as part of an election-year political stunt. That’s at least one concrete example of organizing soldiers as workers that’s underway right now in Texas. There’s another effort along the same lines among National Guard members that the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) is trying to recruit in Connecticut.

Derek Seidman: It feels like a defense of the VA health system is one core undercurrent of your book. Can you talk about what the VA health system looks like? Also, the corporate and rightwing attacks on the VA health care system feature prominently in your book. Readers might be surprised to know that many of the same corporate and right-wing forces that are working to degrade and privatize just about every public service in US society are doing the same in the military world.

Whether it’s hospital services, or military housing, or mental health support, there’s been concerted lobbying and political efforts by corporate forces, including the Koch brothers, to outsource, privatize, and profit off of services for active-duty personnel and veterans. Can you discuss this?

Suzanne Gordon: Let’s start with explaining how the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the VA’s health system, works. The VHA is the largest and only publicly funded and fully integrated health care system in our country. Unlike Medicare, it’s both the payer and provider of care. The VHA has almost four hundred thousand employees, a third of whom are veterans.

Of the nineteen million living veterans today, only about nine million are enrolled in the VA, and only about six million use it daily or depend on it every year for the majority of their health care. This rate of VHA enrollment is due to the fact that Congress refuses to pay the full costs of war and limits eligibility for health services to those who have certain discharge statuses as well as a proven service-connected disability and/or low income. Most of the six million veterans who totally depend on the VHA most are people of color, low income, or women.

The VA delivers health care from discharge to grave. Countless studies document that the healthcare it provides is superior to the care delivered to most of us in the private sector. It’s also more cost effective because all the VA staff are on salary, so there’s no incentive to recommend futile, unnecessary treatments and fraudulently bill the government and recommend unnecessary tests and procedures as occurs so often in the private sector.

The VHA also excels with emergency care and suicide prevention. They’ve integrated mental health and primary care, which is unlike any other system. So, if you go to your primary care doctor and you say, “I’m feeling anxious,” they won’t refer you to a psychologist or psychiatrist. They’ll take you down the hall, and you can meet with those psychologists. They have nutritionists, pharmacists, and social workers. They also integrate what are known as social determinants of health into the system, so they deal with things like homelessness and education and job retraining.

Although the Kochs and the Republicans have promoted this idea that there’s always a long wait in the VA, the wait times are in fact much shorter than in the private sector. That’s because there’s telehealth, and there’s just more of a commitment to get people in.

It’s a really impressive system that works extremely well. Around 92 percent of veterans, when polled, say they like the VA. But that’s the problem — if you have a system that works, then you have a popular system, and that means that $128 billion this year alone is going into the pockets of public sector employees and serving the public. The private sector can’t stand that. The Optums and the United Healthcares, the pharmaceutical industry that has to negotiate lower prices with the VA, find it odious that such a government system delivers better care at lower costs with lower wait times. They are determined to destroy the VA by picking on every little glitch or scandal and amplifying it through the media.

The Koch brothers have spent millions funding an astroturf veteran group called the Concerned Veterans for America that is dedicated to promoting bad news about the VA and privatizing it. Other dark money groups like the American Enterprise Institute and Pacific Research Institute are determined to tarnish the reputation of the VA. They do this, not just because they want the money that’s going into the public coffers to be diverted to the private coffers, but also because they hate the idea of a government program that functions well. The constellation of dark money forces that are trying to privatize the public schools, the post offices, and Medicare are trying to privatize the VA.

And unfortunately, they’re succeeding. In 2018, they passed something called the VA Mission Act, which basically diverts more and more VA patients and VA money to private sector providers. It’s proven to not work, and yet coalitions of Democrats and Republicans have supported this legislation. It’s really disturbing. Only seventy Democrats in the House voted against the Mission Act. Only Bernie Sanders in the Senate and several Republicans from rural states voted against it. Now some Democrats are worried about money leaching out of the VA, without acknowledging that they helped make that happen.

Steve Early: As someone who spent many years trying to help workers with job-related injuries or illnesses, I know, from firsthand experience, that state compensation programs for civilian workers are often difficult to navigate. The benefit payouts are insufficient. Employers dispute whether someone has actually been injured on the job. Cases can be drawn out. And even when people get workers’ comp payments and treatment, the latter is limited to the health problem that’s job-related. If they’re sufficiently disabled, they lose their previous job-based health care coverage and then can’t pay other medical bills for themselves or their family anymore. So compared to VA coverage, that’s a very fragmented, limited, and insufficient system.

In contrast, the VA gives veterans the full range of health care coverage even if you get in with just a partial disability rating. For example, if you lost your hearing as a result of your military service, you won’t just get your hearing aid, but wider, coordinated care. It’s not fragmented, it’s comprehensive. VA rehabilitation programs are much better than any state workers’ comp system. So as Suzanne says, the VA is a model for how a broader national public health care system might operate. And if we think of military veterans as workers, it’s also our best-functioning workers’ comp system for the millions of people who are able to get into the VA, based on having a service-related injury or illness.

Derek Seidman: Your book really demonstrates that the question of veteran politics, identity, and representation is contested terrain. For example, you show that there are major generational and ideological divides between the old guard of veterans service organizations (VSOs) and the newer, younger, more diverse ones — and you also show that even just among the newer and younger VSOs, there are major political and strategic divisions.

Moreover, you have everyone from — as you mentioned — the Koch brothers to Bernie Sanders trying to shape veteran politics and policies. In broad strokes, can you discuss this, and also why it’s important for people on the Left to understand veteran politics as contested terrain?

Steve Early: The nineteen million Americans who served in the military are often viewed as a monolithic bloc. They are thought of being, typically, older, conservative, white males with American flag pins and Legion caps, marching in patriotic parades, voting Republican, and cheering every new war that comes down the pike. Of course, part of that stereotype is true of some of the millions of people who served in the military. But we want readers to understand that’s not an accurate reflection of what’s actually a population with much greater racial, gender, and age diversity.

The Left has understandably always related well to the minority of veterans who were conscientious objectors and antiwar activists. GI dissent has played an important role in strengthening and broadening the base of antiwar movements and bringing wars to swifter conclusions. I think, historically, progressives are familiar with groups like the Vietnam Veterans Against the War or Veterans for Peace, as well as successor organizations like Iraq Veterans Against the War, which morphed into About Face, and Common Defense, a progressive veterans’ group.

Part of the diversity in the veteran population also involves this dual identity of being a trade unionist and a veteran. If you’ve got a million people who’ve served in the military and who are now working at the VA or at the post office, or in building trades jobs or manufacturing jobs, or are telephone workers and members of CWA, that’s a constituency within the labor movement to which the latter needs to pay more attention. The labor movement should be tracking which of their members have served in the military and trying to offer special training and education programs for veterans, while creating more veterans’ committees and caucuses.

CWA has done a number of training programs with Common Defense as part of its Veterans Organizing Institute through a CWA program called the Veterans for Social Change network. This has been a way of trying to mobilize labor-oriented veterans to counter right-wing recruitment of former military personnel. Because otherwise more vets will just end up in the MAGA-land formations that surrounded the Capitol on January 6, 2021, where a disproportionate number of Donald Trump supporters in that crowd had backgrounds in both law enforcement and the military.

Suzanne Gordon: The mainstream media also loves to play up the “crazy veteran” stereotype. While it’s true there are a disproportionate number of veterans who are involved in mass shootings and are perpetrators of police brutality, you never see articles in the New York Times about groups like Veterans for Peace or Common Defense. The public only has an image of a very narrow spectrum of veteran opinion.

I really think these progressive veteran groups deserve a shout out. Common Defense members are supporting US representative Ruben Gallego in his campaign to replace Arizona senator Kyrsten Sinema. They also helped elect Chris Deluzio from Pennsylvania who is now on the House Veterans’ Affairs Committee. If there were more vets like them on that committee, it would reflect a broader range of political views than it currently does. And there would be more members questioning the impact of VA privatization.

I think the assumption that most veterans are automatically hostile to left or progressive ideas is incorrect. Veterans are really varied in their political views. They’re very reachable, particularly if you can claim with some credibility that you support their disability benefit and health care programs. Obviously, if veterans only listen to Fox News and nobody else talks to them, then the “right-wing veteran” image becomes more of a self-fulfilling prophecy. So we’ve encouraged health care reform activists to learn more about the VA and join the struggle against its privatization. If more progressives become defenders of the VA, as Bernie Sanders has been for many years, then veterans and their families will notice that. Over time, it will help counter Fox News claims that the Left hates or looks down upon people who served in the military.

Derek Seidman: You also discuss how big corporations and billionaires engage in a kind of “veteran-washing” where they try to burnish their reputations through seemingly pro-veteran initiatives that have a lot more flash than substance. You bring up the examples of Walmart and Amazon, for example, and how they announced they’d hire more veterans — but in jobs that were systematically stressful, degrading, and nonunionized.

And you explore how corporations help bankroll new veterans’ groups and why this can be a problem — for example, it aligns veterans’ groups with corporate privatization schemes that ultimately degrade veteran care. Can you talk about the problems you see in the relationship between corporations and veterans’ groups?

Suzanne Gordon: If you look at the annual reports of groups like Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, you’ll find that they accept funding from the hospital and pharmaceutical industry and other large corporate interests. It’s no surprise that they have supported bills and initiatives that will lead to the privatization of the VA.

Steve Early: In the private sector, you have veterans who have good unionized jobs, but I think less attention has been paid to the situation of those in nonunion workplaces. Some veterans are getting very involved in key organizing campaigns at companies like Amazon, where there is a big gap between corporate rhetoric and workplace reality. For example, a bunch of these anti-union employers — including Walmart, Starbucks, Comcast, Sprint, and T-Mobile — rallied around a Trump administration suicide-reduction initiative called PREVENTS. They were all very eager to be part of a new “public-private partnership” that was designed to strengthen mental health for veterans in the workplace. So they signed a pledge to “Hire our Heroes” and treat them well.

In the case of Amazon, management promised to hire up to one hundred thousand veterans by the end of next year. As part of this pledge, these same employers committed to reducing workplace risk factors for suicide, such as financial stress, emotional stress, and substance abuse. They pledged to create a safe and inclusive work environment and to create employee resource groups to support newly hired veterans.

At Amazon, men and women who have been in the military are encouraged to join an official support group called “Warriors at Amazon.” But management takes a very hostile stance against any unapproved “affinity group,” like the Amazon Labor Union (ALU), that’s trying to improve conditions in a notoriously unsafe and stressful work environment. In fact, when the ALU was trying to gain a toehold at Amazon warehouses on Staten Island and elsewhere, management made a special effort to hire a few veterans from military intelligence backgrounds to keep other Amazon workers, including fellow veterans, under surveillance, as part of its ongoing union-busting campaign.

In terms of such organizing, unions need to be on the lookout themselves for people with other types of military experience and training. They’re not necessarily going to be industrial spies or stereotypical right-wingers. They may be people who actually have leadership skills, personal courage, and experience with teamwork — some of the positive aspects of military service. That practical experience with collective activity can be put to good use in a nonunion workplace where people do need to be really brave to stand up against a union-busting employer like Amazon or Walmart. As these campaigns expand, I think we’re going to see more veterans become key labor movement activists.

Derek Seidman: You note that many veterans became postal workers and teachers, and many also take government jobs. The American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE) and CWA come up in your book, and you also discuss the progressive veterans’ group Common Defense and efforts to build relations with the labor movement. Can you talk a bit more about the relationship between the labor movement and veterans? And what more could the labor movement be doing to build inroads with veterans?

Steve Early: There are two critical and parallel anti-privatization campaigns where there’s already a lot of community-labor campaigning underway. One is to save the VA from further incremental privatization, while the other is to save the United States Postal Service (USPS) from outsourcing as well. It’s no coincidence that both of these federal employers are a big source of jobs for former military folks.

In the Veterans Health Administration, close to a third of the workforce, about one hundred thousand people, are veterans. So one of the distinctive features of the VA is a culture of solidarity between patients and providers. You have veterans taking care of other veterans, and they’re doing it as doctors, nurses, therapists, and support staff.

A lot of them are active in the major VA unions, such as AFGE, National Nurses United (NNU) — which represents about twenty thousand VA nurses — and several other labor organizations that also have VA units. They are all part of what is one of the most heavily unionized health care systems in the country.

That makes the fight against VA privatization a critical labor struggle that could benefit from broader union support. In the community, many people not connected to unions want to know how to thank veterans for their service. Well, they can contact members of Congress and express understandable concern about the impact of the privatization on jobs and services, which are hard for veterans to find outside the VA.

The same thing is true of the postal workers’ struggle. Historically, the Postal Service has been a way that men and women leaving the military could trade one uniform for another and then provide a vital public service for their community. About 110,000 postal workers represented by the American Postal Workers Union (APWU), the letter carriers and the mail handlers, are veterans. It’s a key source of employment for former service members who are African American. And it’s a public sector job with decent benefits and pay — and until recently, job security.

Particularly under the Trump administration, the Postal Service was a major target for an ongoing privatization push. That is still a threat today under Joe Biden’s administration, because Biden hasn’t fired Postmaster General Louis DeJoy. The mission of this super-wealthy Trump appointee was basically to find ways to dismantle the Postal Service and outsource more of its work to private mail delivery companies. Thanks to widespread community labor resistance, some of DeJoy’s plans were blocked, particularly during the 2020 election when they would have disrupted and delayed mail-ballot voting. But he’s still on the job, working hard to downsize USPS.

I think these are two struggles that many nonveterans could get behind very easily and help win. Thwarting privatization is certainly in our own interest, as people who want reliable public mail service and a good working model for health care for all.

Derek Seidman: The US left — and the global left, for that matter — have long histories of orienting toward soldiers and veterans. GIs and vets, in alliance with civilian organizers, played absolutely crucial roles in major twentieth-century social movements, from the movement against the Vietnam War to the civil rights movement to the 1970s rank-and-file labor upsurge. But today there isn’t a ton of energy or attention given to the military by the US left. It’s not broadly viewed as a terrain for organizing and contention. Why do you think this is? And why do you think people on the Left — even those skeptical of the military’s aims — should pay more attention to active-duty personnel and veterans?

Suzanne Gordon: The last time there was a lot of organizing of active-duty service members and veterans was during the Vietnam War, and there was a draft, so people were perceived as being hauled into these conflicts, often against their will. Today’s all-volunteer army has created a civilian-military divide and made service members feel they’re the only ones signing up and making that sacrifice. On the other side, many civilians think, well, these people volunteered, so they must be gung ho about military intervention.

But that’s not true. There’s an economic draft. I mean, some people do sign up to “kill the bad guys,” but most of them sign up because they want the GI Bill or health care or job training. Also, we used to have military bases in Brooklyn and San Francisco, in more liberal towns, but almost all of them were closed. Now the bases are located mostly in the South and Southwest. Many people don’t know any service members because there are so few nearby. During and after World War II, everybody knew a veteran. During the Vietnam War, I had male friends who were drafted or joined the Reserves or National Guard to avoid being drafted. But now there’s a much greater military-civilian divide.

Steve Early: That divide is definitely a by-product of having an “all-volunteer force” for the last half century. When we no longer had the pressure of the draft on millions of people, it became harder to organize against the Vietnam War in its final stages. I think everybody who’s tried to organize against multiple US wars in the Middle East since then has discovered that it’s more challenging without lots of people facing the possibility of conscription — and therefore being forced to pay more attention to US foreign and military policy and its possible adverse impact on them personally.

The demographics of the DOD’s active-duty workforce have certainly changed since the twentieth-century heyday of the “citizen soldier” to the point where military service has become a kind of family business. Many young people enlist these days because their moms and aunts or uncles and fathers served, so you end up with multigenerational military families even if they don’t include career military people — and largely hailing from nine or ten states that also have a disproportionate number of military bases.

The burden of military service is not just shared by a much narrower slice of the total population. The 1 percent who serve have also been fashioned into what our friend Danny Sjursen, a retired Army major and West Point graduate, calls “a homegrown foreign legion.” In the post-9/11 era of “forever wars,” that kind of US military has indeed become more formidable “terrain for organizing and contention.”

READ MORE  Justice Samuel Alito testifies about the court's budget in 2019. (photo: Chip Somodevilla/Slate)

Justice Samuel Alito testifies about the court's budget in 2019. (photo: Chip Somodevilla/Slate)

The court ruled that protection under the CWA only applies when wetlands have “a continuous surface connection to bodies that are ‘waters of the United States’ in their own right, so that there is no clear demarcation between ‘waters’ and wetlands.” Justice Samuel Alito arrived at this distinction by parsing the wording of the Clean Water Act as passed by Congress in 1972 and amended in 2018—specifically the words “waters of the United States”—and the opinion makes much of this means of arriving at the decision. However, at no point does the opinion consider what connections between waters actually look like or how they work.

The notion that a wetland can only be linked to streams or lakes by a continuous surface connection—presumably visible to the justices themselves—is fundamentally at odds with hydrology, the science of water. The movement of water beneath the surface (groundwater) connects water bodies in ways that are just as or more important than surface connections, something that has been understood by hydrologists for well over a century. There is about one hundred times the volume of fresh groundwater beneath the surface as there is in lakes, rivers, and wetlands combined. Water routinely moves from wetlands into rivers and streams, and back, and much of that exchange is beneath the surface. Groundwater movement freely allows wetlands to connect to rivers even when there is no visible surface connection. Consequently, there is quite commonly no clear demarcation between “waters” and wetlands whether there is a surface connection or not. The distinction drawn by the court is hydrologically meaningless. The water itself can flow back and forth, whether the justices see it with their eyes or not. Hydrologists use the concept of “watershed” to include all the waters in a basin because they are almost always all connected, often by flow beneath the surface. This should come as no surprise even to someone with no background in hydrology. We are all at least passingly aware of the many of cases of groundwater contamination that impact water bodies of all kinds, with substantial human, ecological, and economic costs.

However, there is no need to criticize the quality of scientific understanding in the opinion—because there is nothing to criticize. Remarkably, the opinion seeks “to decide the proper test for determining whether wetlands are ‘waters of the United States’ ” while explicitly excluding scientific understanding from this test. The scope of the new opinion goes far beyond what was necessary to resolve the case before it. The court used this opportunity to deliberately undermine the CWA by establishing an expansive “proper test” that has no scientific basis. Instead of giving even minimal consideration to the science of water in making this sweeping ruling, the court cites as authorities various English-language and law dictionaries. The court apparently considers the physical principles of water movement irrelevant to a ruling that has the potential for enormous impacts on water quality and the environment.

Indeed, the court says so: It derides the EPA’s interpretation of “adjacent” and overturns the use of the concept of a “significant nexus” between a wetland and another water body, a standard that had been in place since a previous court decision in 2006. However, the EPA’s usage has a considerably firmer hydrological basis for understanding the connections between wetlands and waterways than the court’s new continuous surface connection standard.

Justices Elena Kagan and Brett Kavanaugh correctly note that it is well understood that wetlands can be linked to other water bodies without an obvious surface connection. If the court were truly interested in establishing whether wetlands are connected to other water bodies, instead of abstruse arguments about the meaning of adjacent vs. adjoining, the hydrologic sciences have an extensive tool kit that can address those questions. But the court opinion dismisses that approach as “fact-intensive,” as if facts bearing on a question were somehow a hindrance to a logical and just decision.

Further, the court takes a distinctly negative view of the possibility that the classification of a wetland could “evolve as scientific understandings change.” There could hardly be a clearer indication of the disconnect between law and science in this opinion. According to the court, the law demands a fixed definition of a wetland and its connectivity that depends weakly if at all on the facts of a specific case. That science would seek to marshal facts and to evolve understanding as new information becomes available is clearly a bug, not a feature, in the eyes of Alito.

A case about our natural world is not contract law—there is actual physical reality involved that can only be ignored at the peril of making a poor or even dangerous decision. If you jump off a bridge, gravity will surely decide the outcome, regardless of the wording of a statute on bridge-jumping. The result of the court’s linguistic analysis is an exiguous textual opinion based on parsing dictionaries instead of a functional understanding even minimally consistent with basic science.

As much as they might like to believe otherwise, even the Supreme Court does not have the power to decide if water will flow from a wetland to a stream. It will do so based on well-understood physical principles that are unaffected by legal hair-splitting. The court should not hide behind dictionary definitions in addressing questions that are inextricably both legal and scientific and that have enormous consequences for our environment and quality of life. That the court chose to deliberately ignore any scientific knowledge of the question before it and directly reject any consideration of the environmental consequences of its decision does not make this a narrow textual decision—it makes it narrow-minded.

In handing down this decision, the court has seriously undermined the explicitly stated intent of Congress “to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation’s waters.” In many cases, the goals of the CWA simply cannot be achieved if a large fraction of wetlands is excluded from its purview. The opinion supporting this outcome is plainly physics-free. But physics applies whether the court wants it to or not. Wetlands are almost always connected to streams and lakes, and damaging or polluting wetlands will negatively impact the integrity of the nation’s waters, whether the court can see the connection or not. They are demonstrably part of the waters of the United States and no rational water quality policy—or legal opinion—can pretend otherwise.

READ MORE  Striking academic workers at the University of California, Los Angeles in November 2022. (photo: Gary Coronado/LA Times)

Striking academic workers at the University of California, Los Angeles in November 2022. (photo: Gary Coronado/LA Times)

Unions won’t come back without fundamental changes to bargaining.

I am, like all non-management Vox staff, a Writers Guild of America, East member, and a former member of Vox’s union bargaining committee, so I empathize with the urge to be optimistic about the future of organized labor, especially at a time when my comrades in the film and TV industries are striking for a better contract. I stand in solidarity with them and hope they get an excellent contract.

But I think it’s even more important to be honest about the situation. Organized labor is not booming, rebounding, or in a resurgence of any kind. Instead, it is in decline, as it has been for many years.

Official data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics starts in 1983. That year, 20.1 percent of all workers were in a union. That’s down to 10.1 percent as of 2022 — the lowest it’s ever been in that time frame. The decline has been basically continuous, with brief interruptions in 2008 and 2020 as non-unionized workers lost jobs faster than those with union protections. While public-sector unionization has fluctuated a bit (it fell from 36.7 percent to 33.1 percent from 1983 to 2022), by far the sharper decline is in the private sector, where rates fell from 16.8 to 6 percent.

Planet Money’s Greg Rosalsky put it well in a piece earlier this year: “While there was an uptick in labor organizing in 2022, we’re hardly witnessing a rejuvenated movement strong enough to dramatically reverse unions’ long-run decline.”

What’s driving the decline in unions?

Starting the data at 1983 gives a misleading picture: The decline of unions began well before then.

Harvard economist Richard B. Freeman has put together data on union membership going back over 100 years. It shows that the share of households with a union member was around 10-11 percent going into the Great Depression. Starting in 1937 (not coincidentally the year the Supreme Court upheld the pro-union National Labor Relations Act passed two years earlier), you see a dramatic rise in membership. The rate went from 13.2 percent in 1936 to 26.6 percent in 1938. The rate peaked at around a third of households, and stayed in that range for decades. But by the mid-1950s, a slight but perceptible decline was already starting, which has continued ever since.

I’ve seen two major theories for why this happened. The first emphasizes politics: Countries with more left-wing governments have seen smaller declines in unions. In Canada, for instance, the share of workers in a union has fallen, but the fall is less stark than in the US, which might be explainable by its more pro-union laws.

The second emphasizes the fact that union firms tend to expand their workforces less quickly than other firms. That makes sense: Unions raise wages, so union workforces cost more. But over time, this effect means a greater and greater share of the workforce is non-unionized because non-unionized firms are able to grow faster.

In a landmark 2001 paper, economist Henry Farber and sociologist Bruce Western credited this as a major factor behind union decline in the US. They estimated that unions would have to increase their organizing rate sixfold just to keep the US membership rate constant. To increase unionization, they’d need an even more dramatic and improbable explosion in organizing.

I lean toward the latter theory. It helps explain why you didn’t see a collapse in union rates when hostile governments (like those of Ronald Reagan or George W. Bush) came to power, but instead the same gradual decline as occurred under Democrats.

Laws, not vibes

Whatever explanation you choose, any attempt at union revitalization will require much more than organizing a few Starbucks locations. It will require wholesale change to labor law.

The political scientist David Madland’s book Re-Union gets into the details well, but the gist is you need to find ways to organize unions across whole sectors, not just workplace by workplace. In many European countries, firms don’t pay a penalty for paying good union wages; union contracts are “extended” to whole sectors. If UPS drivers win a good contract, FedEx would then have to abide by those terms too, even though it doesn’t have a staff union.

This would be an ambitious change. The PRO Act, the labor movements’ big priority in Congress (which is currently dead in the water given Republican control of the House), wouldn’t do much to further it; that act would mostly strengthen the existing workplace-based system, which is valuable but insufficient. Some states like California are experimenting with sectoral bargaining, but we’re in very, very early days yet.

The future of labor, I think, lies much more heavily in legal reform efforts meant to enable that kind of broader bargaining than it does in a few heavily publicized elections at individual companies. It’s not sexy work, but it’s the only thing that could return organized labor to the power it once had in the US.

READ MORE  Gwen Gehlhausen, right, embraces Arlo Dennis at their home in Orlando last month. (photo: Thomas Simonetti/WP)

Gwen Gehlhausen, right, embraces Arlo Dennis at their home in Orlando last month. (photo: Thomas Simonetti/WP)

That is the day a slate of new laws signed by Gov. Ron DeSantis targeting the LGBTQ community take effect. Doctors will be allowed to deny care based on their moral beliefs. The use of preferred pronouns will be banned in public schools. And children will be barred from attending drag shows, among other measures. One law that prohibits gender-affirming health care for transgender people under the age of 18 is already being enforced.

The Republican governor vying to become president in the 2024 election championed the bills as part of his “Florida Blueprint.” His critics call it “the slate of hate.”

For Dennis, they add up to a difficult but urgent decision to flee. “I’m a trans adult. I have gender nonconforming children, and these laws are just so specifically targeting our communities that I don’t feel like my parenting relationship is going to continue to be respected,” Dennis said. “We just low grade don’t feel safe.”

A tectonic shift in how the LGBTQ community perceives its welcome is underway in a state famed for both a vibrant gay history in pockets like Key West and a past filled with examples of intolerance and aggression. While some of the new legislation builds on previous laws, gay rights advocates say they are alarmed by the sheer number of bills and the increasingly hostile rhetoric from DeSantis and Republican state lawmakers, who have championed the legislation as making Florida safe for children and standing up for parental rights, echoing a theme frequently used on the campaign trail by DeSantis.

In recent weeks, several civil rights groups have issued travel advisories for Florida, warning LGBTQ tourists to reconsider plans to visit the Sunshine State. The overall impact of the laws make Florida “openly hostile toward African Americans, people of color and LGBTQ+ individuals,” the NAACP, the oldest civil rights organization in the nation, said in its warning in May.

Two Florida communities have canceled annual Pride parades out of concern that they will unintentionally break a new law that makes it a third-degree felony to have a child present at “an adult live performance.” Some transgender families are placing their children in private schools. And a growing roster of LGBTQ families and individuals are opting to leave.

NBA superstar Dwyane Wade announced that he had moved his family to California in part because he feared his transgender teenage daughter “would not be accepted or feel comfortable” in Florida. A NASA engineer left for Illinois after concluding the new bills amount to the state “attempting to erase trans people.”

Those who cannot afford to relocate are turning to GoFundMe to raise money to leave a state they say has become a dangerous place for them and their children. Advocates for transgender Floridians have started Transit Underground, an informal coalition to help connect those leaving with volunteers who offer transportation and temporary housing.

“We’re telling allies who say we should not leave, but stay and fight, that trans people can’t live in a state of genocidal terror,” said Lakey Love, a founder of the Florida Coalition for Transgender Liberation, which is supporting Transit Underground.

DeSantis and his staff have dismissed the growing backlash. Christina Pushaw, a former DeSantis spokeswoman who now works for his presidential campaign, posted a tweet in response to a survey indicating LGBTQ families are leaving the state with a single emoji: a waving hand. The governor likened the travel advisories to “a stunt” and has insisted the purpose of the laws is to “let our children be children.”

“We have a very crazy age that we live in. There is a lot of nonsense that gets floated around,” DeSantis said to a crowd of supporters at the Christian Cambridge School in Tampa in May. “What we have said in Florida is, we are going to remain a refuge of sanity and a citadel of normalcy.”

‘People became complacent’

Florida is home to several cities famed for embracing gay life and culture but, as with many states, its history with the LGBTQ community has been uneven.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the Johns Committee, a state-sponsored investigative panel, targeted civil rights activists suspected of ties to communists. Its work eventually homed in on Florida universities. A 1959 report by the group alleged that “homosexual professors were recruiting students into ‘homosexual practices’ and they in turn were becoming teachers in Florida’s public-school system and recruiting even younger students.”

A decade later, former beauty queen Anita Bryant launched what some now see as a precursor to the DeSantis-backed measure critics call “Don’t Say Gay,” which bars classroom lessons related to gender identity and sexual orientation in K-12 public schools. She championed a crusade known as “Save Our Children” to overturn a local ordinance in Miami that prohibited discrimination against LGBTQ people in housing, work and private education, arguing it infringed on her rights as a parent.

Despite that complicated past, gay pride flourished in parts of the state. Glamorous hotels and restaurants catering to the gay community sprang up in Miami Beach in the 1970s and remain fixtures today. Thousands flock to Key West for Pride Month and New Year’s Eve, when the island city does a ball drop hosted by a drag queen.

There and elsewhere, many have felt the worst was behind them, particularly after the Supreme Court recognized same-sex marriage in 2015, said Scott Galvin, director of Safe Schools South Florida, which works with LGBTQ youth. “We thought, we’ve arrived, the struggle is over,” said Galvin, who is also a longtime North Miami City Council member. “As a result, people became complacent.”

Even after the 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting, many in the gay community felt a sense of solidarity. The outpouring of grief and support poured into Orlando from across the political spectrum, including from DeSantis, who in 2019 attended a memorial event with his wife, Casey.

“Even people who were not LGBTQ felt attacked,” Dennis recalled after a gunman killed 49 people in the gay nightclub. “After Pulse, I remember hearing a man, he looked like a regular good old boy, say ‘These are my gays. Don’t mess with them.’”

When DeSantis last year signed the Parental Rights in Education Act, known as the “Don’t Say Gay” bill, Galvin said he was taken aback. He saw schools ordering teachers to remove rainbow flags and safe space stickers from their classrooms. Some teachers began pulling books like “And Tango Makes Three,” a picture book at about two male penguins who form a family, from their bookshelves, fearful of getting into trouble.

Then he was hit directly: Miami-Dade County schools, which for 20 years had welcomed Galvin’s nonprofit to host an annual empowerment day for LGBTQ students, refused to authorize the event this year, citing the new law.

“When all of this started, we had a hard time motivating people in the LGBTQ community who don’t have children,” Galvin said. “You know, you’re 35 years old and you’re hitting up the clubs, life is great, so what happens in schools doesn’t affect you, right?” Now, he said, “they’re starting to realize that we’re all under attack.”

The state had shifted further right politically, as evidenced by the double-digit reelection of DeSantis last November. And while the governor set his sights on the Republican presidential nomination, his allies in the legislature introduced a new crop of bills placing restrictions on transgender people.

A fight over ‘childhood itself’

The bills aimed to establish some of the strictest provisions on gender-affirming care and how gender identity is addressed in the classroom. Whether they would pass was not in doubt. With a Republican supermajority in the legislature, most of the signature proposals from DeSantis easily advanced. But public hearings were contentious.

Tsi Day Smyth, who is nonbinary and has a transgender child, spoke often at the hearings, an act of protest they called exhausting and dispiriting. “You’re looking at legislation meant to erase people. And when you enter that room, you feel like they’ve already erased you,” Day Smyth later recalled in an interview.

During a hearing over a bathroom bill, state Rep. Webster Barnaby (R) lashed out against those speaking against the legislation, likening them to people who are “happy to display themselves as if they were mutants from another planet.”

“The Lord rebuke you, Satan, and all of your demons and all of your imps who come parade before us,” Barnaby said, looking at the speakers, including Day Smyth. “That’s right. I call you demons and imps who come and parade before us and pretend that you are part of this world.” Barnaby briefly apologized several minutes later, but Day Smyth said the message coming from Republican lawmakers was clear: Trans people are not welcome here.

The harsh rhetoric continued even after the bills were passed. At a bill signing event in May, DeSantis was joined by Rep. Randy Fine (R), who sponsored some of the anti-LGBTQ legislation. Fine likened the bills as part of a broader war of good against evil. “There is evil in this world, and we are fighting it here today,” Fine said. “The fight that we have had here in Florida is about the fundamental nature of childhood itself.”

‘Taking us back 100 years’

The new laws already appear to be having a chilling effect. Florida is home to about 95,000 transgender adults, according to an estimate from the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law, and while the vast majority are likely to stay, a number like the Dennis family are taking steps to leave.

According to GoFundMe, there has been a surge in fundraisers created to support trans people looking to relocate to more LGBTQ-friendly states since May 2022. So far this year, more than $200,000 has been raised on the platform to support trans people and their families looking to leave Florida.

Among those deciding to leave Florida is Eleanor McDonough, who was the only out trans woman working in the state legislature. She served as an aide to state Democratic Rep. Rita Harris, but she left after the session ended in May, convinced that there is “no indication that the Republican supermajority is going to stop any time soon.”

Some Republican lawmakers told McDonough they did not believe in all of the anti-trans rhetoric and legislation, but she said they told her they felt they had to support DeSantis in his policies or see their own legislative priorities killed. “They found it hard to make eye contact with me at the end,” McDonough said. “They would just look away from me, almost like they felt shame on their part for what they were doing.”

The anti-LGBTQ turn is evident beyond the halls of power in the capital of Tallahassee. On May 17, the day DeSantis signed his slate of LGBTQ-focused bills, someone hacked an electronic street sign in Orlando, across town from where the Dennis family lives. The sign had been put up for an upcoming marathon.

Hackers changed the language to read: “KILL ALL GAYS.”

“What is happening now is taking us back not 50 years, but 100 years,” said Caitlin Ryan, a founder of the Family Acceptance Project at San Francisco State University in California. “It is extremely destructive.”

Still, many are also vowing to stay and defend their rights, gathering to protest at the state capitol, and showing up at pride events. Tens of thousands gathered the first weekend in June in Orlando for the annual Gay Days events at Walt Disney World kicking off Pride month of June.

“I have trans friends who are leaving the state,” said Joseph Clark, chief executive of the Gay Days event. “People don’t feel safe right now. They don’t feel welcome. But I think that is more of a reason to do what we’ve been doing on an annual basis for more than 30 years.”

‘We can’t stay in Florida’

For the Dennis family, normalcy is a family made up of three parents, all of whom are transgender, raising two children. Hazel is 12 and Sparrow is 5. Dennis said both their children are gender creative, a term that describes individuals who do not identify as a man or a woman. Dennis said there is a feeling of dread now because of laws directed at transgender families like theirs.

When Sparrow was born, Dennis, 35, said they would be a “theyby,” a baby whose gender was not advertised to the world. Gaining acceptance and affirmation for that choice was difficult, Dennis said, even in Orlando, a city whose voters have consistently elected progressive politicians over the past decade. “Not everyone is accepting,” Dennis said. “I don’t need my neighbor to like me. But I need laws to protect me.”

Hazel quickly chimed in with a remark that hinted at the fear the family lives with because of anti-LGBTQ laws and hostile rhetoric in Florida. “For instance, I don’t want to get shot,” Hazel said. Dennis said they do not want their children to endure hatred.

The parents got together and consulted a map of the country that shows states that have LGBTQ-friendly policies. They picked Maryland, and they are moving there in early July.

Dennis needs medication for their transition, which has also become more difficult in Florida for adults. Dennis has been a community organizer in Orlando and said they will miss “the tenacity and the creativity and the resilience of community.”

“It feels like I’m jumping off a sinking ship and being like, well, I got my life raft, y’all take care of yourselves,” Dennis said. “But we can’t stay in Florida.”

READ MORE  Dogs stand in flood water as civilians are evacuated in Kherson, Ukraine, on June 7, 2023. (photo: Muhammed Enes Yildirim/Anadolu Agency)

Dogs stand in flood water as civilians are evacuated in Kherson, Ukraine, on June 7, 2023. (photo: Muhammed Enes Yildirim/Anadolu Agency)

Millions of fish have already washed up dead and other animals and plant life have likely been affected, experts warned.

Iryna Tutyun told NBC News that it was “difficult to cope” with the number of animals in need of help after huge swaths of the southern city of Kherson and its surrounding area were inundated following the destruction of the Kakhovka dam Tuesday.

“I still have about 30 dogs and a dozen cats in my care. Every morning I go to them, feed them and see if everything is OK with them,” Tutyun, 43, said, adding that some of the animals had been injured.

On a wider scale, experts are also warning that the impact on the region’s wildlife could be “catastrophic,” as millions of fish have already washed up dead and other animals and plant life likely have been affected.

Tutyun said she had also heard of goats, chickens and other animals being plucked from the waters that spilled from the reservoir behind the dam, which was 150 miles long and around 14 miles wide.

Both Ukraine and Russia have traded blame for the destruction of the vast dam in a Russian-controlled area on the front lines of the war. Tutyun said the massive spill is the worst thing that has happened to Kherson, which was taken by Russia days after President Vladimir Putin launched his invasion in February 2022 and then liberated by Ukrainian forces in November.

Tutyun said that after the invasion she “went through Russian checkpoints, sometimes under the watchful eyes of machine guns,” to feed the animals and has been looking after them ever since.

Elsewhere in Kherson, the Kazkova Dibrova zoo said in a Facebook post Tuesday that a pair of monkeys, Anfisa and Charlie, and a pony named Malish, were among 300 animals killed by the flooding. A mule, a parrot, a crow, a groundhog, guinea pigs and ferrets, also perished, zoo officials said.

In addition to this, the State Agency of Land Reclamation and Fisheries of Ukraine said in a Facebook post that it had observed “a significant number of dead fish,” with the Silver Crucian Carp particularly affected. Several social media users also posted videos of dead fish washing up.

Calling the consequences “catastrophic,” the Nizhnyodniprovskyi National Nature Park also posted a statement to Facebook saying that a large swath of its 193,056 acres was underwater.

Quoting Alexey Chachibaya, the park’s director, the statement said that the rise in water levels had led to the “mass death” of animals and plants.

Were the water to rise, he said, it could lead to the “destruction of buildings near the river and destruction of flora and fauna in those settlements affected by flooding.”

There are a number of ecologically important areas along the Dnieper river, including wetlands, according to Doug Weir, the research and policy director at the Conflict and Environment Observatory, a nonprofit organization based in Britain.

“Much of the lower Dnieper and its tributaries are part of the Emerald Network, sites designated for their ecological importance, and include nature reserves and other protected areas,” he said.

In the short term, Weir said, “we can expect significant physical changes to habitats from both erosion and the deposition of sediments; both can impact aquatic habitats. The floodwaters are also mobilizing a range of pollutants from industrial, agricultural, energy and residential areas, these may affect species and habitats,” he noted.

Weir added that the floods would “create considerable volumes of solid waste, which will need to be managed in an environmentally sound manner.”

While nature will recover, he said “the ecosystems and habitats will be different following the disturbance,” although it was “likely that they will be less diverse and therefore less resilient to environmental change, such as climatic changes.”

Thor Hanson, an independent conservation biologist who specializes on how wars affect the environment, agreed that aquatic habitats would be affected.

“Rising waters in adjacent wetlands, particularly near the mouth of the river, threaten to flood countless active nests, burrows, and breeding pools, reducing or eliminating reproductive output for the year,” he said in an email Thursday.

He added that contamination from the dam site itself “and from potential flooding of military and industrial sites downstream may impact ecosystems and human health far into the post-war period.”

In the meantime, Tutyun said she “can’t leave” all the animals she has been helping, along with several senior neighbors she also cares for.

Vowing to stay in Kherson, she said, “I hope this will come to an end. I have hope that one day the water will dry, the shelling will stop.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment