Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The article below is satire. Andy Borowitz is an American comedian and New York Times-bestselling author who satirizes the news for his column, "The Borowitz Report."

Though Santos’s claim not to exist was given long odds of succeeding, he forcefully made his case for his own unreality.

“Your honor, I stand before you, a fictitious character,” Santos proclaimed.

The New York congressman argued that, since he does not exist, all charges against him should be dropped, but he promised to submit to the judicial process in his cinematic universe.

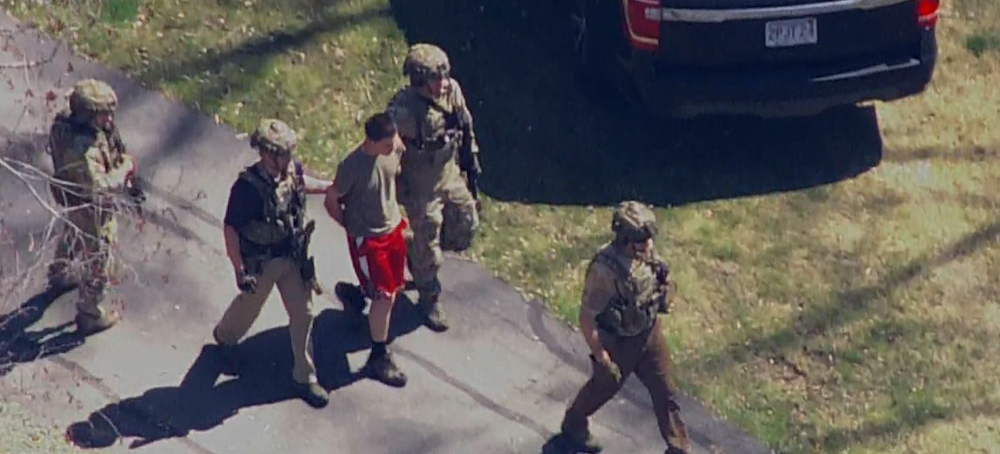

READ MORE  Jack Teixeira was arrested in connection with the leaking of classified documents that were posted online. (photo: CNN)

Jack Teixeira was arrested in connection with the leaking of classified documents that were posted online. (photo: CNN)

Videos and chat logs reveal Jack Teixeira’s preparations for a violent social conflict, his racist thinking and a deep suspicion of the government he served

“Jews scam, n-----s rape, and I mag dump.”

Teixeira raised his weapon, aimed at an unseen target and fired 10 times in rapid succession, emptying the magazine of bullets.

The six-second video, taken at a gun range near Teixeira’s home in Massachusetts, affords a brief but illuminating glimpse into the offline world of the 21-year-old National Guard member, who stands accused of leaking a trove of classified military intelligence on the group-chat platform Discord.

Previously unpublished videos and chat logs reviewed by The Washington Post, as well as interviews with several of Teixeira’s close friends, suggest that he was readying for what he imagined would be a violent struggle against a legion of perceived adversaries — including Blacks, political liberals, Jews, gay and transgender people — who would make life intolerable for the kind of person Teixeira professed to be: an Orthodox Christian, politically conservative and ready to defend, if not the government of the United States, a set of ideals on which he imagined it was founded.

Teixeira’s love of guns, which first drew him to an online community of friends, was intertwined with a deep suspicion of the government that he served as an enlisted member of the Air National Guard. But Teixeira did not consider himself a whistleblower, according to friends.

By the time of his arrest, filings by federal prosecutors show that Teixeira had amassed a small arsenal of rifles, shotguns and pistols, as well as a helmet, gas mask and night-vision goggles, all under the roof of the house where he lived with his mother and stepfather. The Post obtained and verified two videos taken at their home in Dighton, Mass., where the FBI arrested Teixeira last month.

Filmed from the shooter’s perspective, the first video shows a person identified by a Discord user as Teixeira firing an AR-style weapon into the forest. Another video shows the gunman firing a pistol into the woods behind Teixeira’s home, including two rapid volleys that suggest the weapon may have been modified. It isn’t clear what legal or illegal modifications Teixeira may have made, though devices like binary triggers and typically illegal auto sear accessories can make semiautomatic guns fire quicker than they are designed to shoot. A separate photograph shows an AK-style weapon resting on a table outside the family home next to a helmet with attached night-vision goggles.

For Teixeira, firearms practice seemed to be more than a hobby. “He used the term ‘race war’ quite a few times,” said a close friend who spent time with Teixeira in an online community on Discord, a platform popular with video game players, and had lengthy private phone and video calls with him over the course of several years.

“He did call himself racist, multiple times,” the friend said in an interview. “I would say he was proud of it.”

The friend, like others on the server, spoke on the condition of anonymity to avoid being associated publicly with Teixeira, who faces a potential sentence of 25 years in prison. The friend gave a video interview to The Post and requested that their face be obscured and their voice modified.

In the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, Teixeira told friends that he saw a storm gathering. “He was afraid they would target White people,” his friend said. “He had told me quite a few times he thought they need to be prepared for a revolution.” The friend said Teixeira spoke approvingly of Kyle Rittenhouse, a teenager who shot three people, two fatally, during protests that summer in Kenosha, Wis., claiming that he had acted in self-defense. A jury acquitted Rittenhouse of five counts, including intentional first-degree homicide, in 2021.

Teixeira’s preparations for civil chaos weren’t limited to arms; knowledge was also power. His job as a computer technician at Otis Air Force Base, on Cape Cod, gave him access to the Pentagon’s network for top-secret information, where, according to his friends, Teixeira viewed thousands of classified documents on a vast range of topics, from the war in Ukraine to North Korean ballistic missile launches to attempts by foreign governments to interfere in U.S. elections. Teixeira shared some of this intelligence bounty with a band of about two dozen people in a Discord server he came to control called Thug Shaker Central. (The server’s name, the most often used of several, is a racist allusion.) Teixeira’s goal, they said, was to reveal truths that powerful people had hidden from ordinary ones.

Teixeira wanted his online companions, many of them teenage boys, to “be prepared for things the government might do, reinforcing to them that the government was lying to them,” said the close friend, who was also a member of the server. Beginning in 2022, the year after Teixeira was granted a top-secret government security clearance following a standard background investigation, he began posting classified documents in the server, first typing them out by hand and later uploading photographs of printed documents bearing classification markings and restrictions on their distribution. He also shared video from the base, showing friends on the server where he worked and allegedly secreted away classified intelligence.

The Post obtained hundreds of documents, as well as text messages, that Teixeira shared on the server over the course of several months. Teixeira’s lawyers declined to comment. Teixeira, who remains in federal custody, has not entered a plea.

Teixeira occasionally augmented his leaks with sober analysis. He once confidently predicted that China “will be trying to avoid sanctions and appease us in the near term” in light of new laws and regulations aimed at blunting the country’s semiconductor manufacturing industry.

But Teixeira’s missives also revealed a conspiratorial streak.

“Recently a Al-Qaeda sympathizer moved nearby my area, immigrant and we’re finding more about their organization,” he wrote in October 2022, apparently referring to the U.S. government. “Any sand ni--er like that we will watch them[.]”

On Discord, an account with the handle “Jack the Dripper,” one of Teixeira’s known monikers, shared an image titled “payback,” showing a large passenger jet careening toward the Kaaba in Mecca, Islam’s holiest site.

Teixeira asserted that “lots of FBI agents were found to have sympathized with the Jan 6 rioters,” and he said naive members of the intelligence community, of which he was technically a part, had been “cucked.” He referred to mainstream press as “zogshit,” appropriating a popular white-supremacist slur for the “Zionist Occupied Government.” Friends said that during live video chats, Teixeira expounded on baseless accusations of shadowy, sinister control by Jewish and liberal elites, as well as corrupt law enforcement authorities.

“He had quite a few conspiratorial beliefs,” the close friend said, adding: “I remember him multiple times talking about things like Waco and Ruby Ridge, and talking about how the government kills their own people,” referring to a pair of notorious armed standoffs that the far right has held up as emblematic of government oppression.

Polarized by the pandemic

Already united by their love of guns and their Orthodox Christian faith, two members of Thug Shaker Central said their nascent political beliefs became hardened and more polarized during the isolation of the pandemic. Unable to see their local friends in person, the young members spent their entire days in front of screens and came under the influence of outsize online figures like Teixeira. Some on the server saw him as an older brother — others, friends said, like a father figure.

The Post obtained previously unpublished screenshots from the server and recordings of members playing games together. Racist and antisemitic language flowed through the community, as did hostility for gay and transgender people, whom Teixeira deemed “degenerate.” The line between sarcasm and genuine belief became increasingly blurred. On video calls, users held up a finger, jokingly imitating members of ISIS. In their rooms were flags associated with Christian nationalism and white power.

In interviews, some of the members struggled to explain worldviews that had developed largely online, and expressed remorse. Several admitted they had become radicalized during the pandemic and were influenced by Teixeira, whose own politics seemed animated by social grievances and an obsession with guns.

The members may have sensed they were treading into dangerous political waters, even before leaked classified documents started circulating. During video chats, some hid their faces behind masks, fearful of being publicly identified with a group of self-professed bigots, Teixeira’s close friend said.

After he enlisted in the U.S. Air National Guard in September 2019, Teixeira also feared that his own racist and violent statements would jeopardize his chances of getting a security clearance. “He was worried something from Discord would come up during his interview,” said the friend, who met him when the application was still pending. Teixeira changed his online handle to an innocuous version of his surname and became “less active” in the community for a time, the friend added, in an effort not to create more incriminating evidence.

But Teixeira already had an offline record that arguably should have raised concerns for the officials who approved his security clearance. In March 2018, Teixeira was suspended from his high school “when a classmate overheard him make remarks about weapons, including Molotov cocktails, guns at the school, and racial threats,” according to a Justice Department filing last month that argued Teixeira should remain in jail while he faces charges under the Espionage Act stemming from his alleged leaks.

Federal prosecutors noted that, according to local police records, Teixeira claimed that he had been talking about a video game when he made the alarming comments. But other students disputed that characterization, prosecutors said. And Teixeira’s close friend, who knew him after he had graduated high school, said he had confessed to wanting to take a gun to school and carry out a shooting.

“He had told me multiple times about when he was younger, his desire to shoot up his school,” the friend said. “He hated his school.”

“To my knowledge, he never hurt anyone physically, but he absolutely talked about it pretty often,” the friend added. Other friends confirmed Teixeira talked about attacking his school, but they said they didn’t take his threats seriously.

It remains unclear how Teixeira obtained a clearance and what consideration, if any, adjudicators gave to his history of violent remarks.

Ann Stefanek, an Air Force spokeswoman, said Teixeira is subject to “potential discipline,” considering he was working under active duty. After the Air Force concludes an investigation, she said, a commander will determine if Teixeira should face charges in the military. The service is coordinating closely with the FBI in the leak investigation, she said.

Teixeira remains an airman first class, a low-ranking enlisted service member, as he awaits trial on the leaking charges.

The military has, in the past, struggled to track down individuals who have espoused racist or white-nationalist ideologies. Service members have faced charges that include dereliction of duty and misconduct for racist rants.

After Teixeira got his privileged access, he sought out another official license that had eluded him: a firearms identification card, which, in the state of Massachusetts, permits the possession of “non-large-capacity rifles, shotguns, and ammunition.”

Teixeira’s application had been turned down in 2018 due to the concerns of local police about his violent remarks at his high school, court records show. But in a letter to a local police officer in 2020, Teixeira argued that his new career in the Air Force, and the security clearance that came with it, demonstrated his trustworthiness.

“I now represent much more than myself and need to watch what I say and do both in public and in private, as it affects more than just myself,” Teixeira wrote in November 2020. He allegedly began divulging classified information online a little more than a year later.

A second server

The pandemic refuge of Thug Shaker Central wasn’t the only place Teixeira appears to have spilled protected information.

According to court documents and online records reviewed by The Post, Teixeira posted intelligence on another Discord server as early as February 2022. This community of gamers contained hundreds of people, exposing official secrets to a much larger audience than his tight-circle of friends, who said they understood they should keep the classified documents to themselves.

The server, called Abinavski’s Exclusion Zone, is associated with a YouTube streamer who plays the video game War Thunder, known for its realistic models of tanks, fighter jets and other military vehicles. A member of the server, who asked not to be identified, said a user believed to be Teixeira posted intelligence in a channel called “civil-discussions,” usually in a running thread.

Abinavski’s Exclusion Zone remained active this month. When The Post reviewed the server on Tuesday, it listed 627 members, of whom 150 were online at the time.

On April 6, a Discord user informed Teixeira that he had seen material he believed the service member had shared show up on another social media platform, Telegram, in a channel devoted to pro-Russian topics.

“Is it actually one of them btw,” the unidentified user asked, according to court documents.

“Not commenting,” Teixeira wrote in reply. The user then asked, “[D]id you share them outside of abis,” an apparent reference to Abinavski.

In chat logs made public by prosecutors, Teixeira repeatedly makes reference to “the thread” where he had posted material starting in 2022. In a March 19, 2023, exchange, Teixeira wrote that he’d “decided to stop with the updates,” thanking “everyone who came to the thread about the current event,” an apparent reference to the Russian invasion of Ukraine that had begun a year earlier.

“I was very happy and willing and enthusiastic to have covered this event for the past year and share with all of you,” Teixeira wrote, in comments that match messages the New York Times first reported he had made on that date in what it identified as a second server but didn’t name as Abinavski’s Exclusion Zone. In an email to The Post, Abinavski said a user believed to be Teixeira left the server in early April.

Abinavski said the civil-discussion channel had a thread for conversations around the Ukraine war, created roughly the time Russia invaded. “Members confirmed with me … that photos of documents were posted” to the channel, Abinavski said.

The YouTuber added that Discord deleted the civil-discussion channel on April 24 after “multiple members” received notices from the company.

In a statement, a spokesperson for Discord said: “We have removed content, terminated user accounts, and are cooperating with the efforts of the United States Departments of Defense and Justice in connection with this incident.”

“In this instance, we have banned users involved with the original distribution of the materials, deleted content deemed to be against our Terms of Service and issued warnings to users who continue to share the materials in question,” the spokesperson added.

As classified documents began popping up across the internet, Teixeira asked an unnamed user to help him delete en masse the posts that Teixeira had made in civil-discussions, according to court documents. “If anyone comes looking, don’t tell them shit.”

But the leak that led the authorities to the young National Guard member appears to have come not from Abinavski’s larger group but within Teixera’s trusted circle. The classified information that showed up on Telegram, and later circulated more broadly online, came from a young Thug Shaker Central member, several other members of the server said, who broke the club’s unwritten rule not to share the documents and set off a chain of events that led to Teixeira’s arrest the following month.

Moving from online to IRL

The civil-discussions channel gave Teixeira a large audience. But in Thug Shaker Central, he seemed to feel he was in a more intimate environment, able to share his love of guns and express his political views to a sympathetic audience. Teixeira posted videos and photographs taken at his mother and stepfather’s home in Dighton and clips he recorded at the nearby gun range, where Teixeira made his “mag dump” video.

Teixeira developed an offline relationship with at least one friend on the server: Henry Adams, 18, who lives with his family about an hour’s drive from Dighton in Hanover, Mass.

Three former members of Thug Shaker confirmed Adams’s identity, as well as his close ties with Teixeira and activity on the server. An attorney for Adams, Max Perlman, confirmed that his client knew Teixeira for “around three years,” bonding over shared interests. Through his attorney, Adams denied being a member of Thug Shaker Central, claimed to be unaware of its existence and said he had never seen any “illicit material” posted by Teixeira on any server.

According to a former member of the server, Adams tried to obtain support for Teixeira following his arrest. Asked if Adams had contacted anyone on the server, Perlman said his client had spoken “to one minor individual and asked for letters of support because Mr. Teixeira’s mom ask[ed] him to see if people would do that and get them to his lawyer.”

Perlman said Adams’s and Teixeira visited a shooting range in Raynham, Mass., “many, many times,” accompanied by Adams’s mother, Lisa, his father, Richard, or Teixeira’s biological father, Jack Michael Teixeira.

Reached by phone, Adams’s mother didn’t dispute that her son knew Teixeira. But she denied that he was active on Thug Shaker Central and said he “saw nothing.”

Referring to Teixeira, she asked, “When did serving your country and being a Christian become a bad thing?”

Attempts to reach Jack Michael Teixeira were unsuccessful.

Additional videos obtained and verified by The Post showed Teixeira and Adams at the gun range, owned by Taunton Rifle and Pistol Club. In one, Adams fires a Soviet-era SKS rifle. In another, Teixeira fires a pump action shotgun.

The club president, Eric Dewhirst, confirmed that the footage was taken at the members-only facility. In an interview at the organization’s clubhouse, Dewhirst said there was no record of Teixeira being a member, suggesting that he and his friend were probably taken there by someone else. Dewhirst, who said he had read about Teixeira’s alleged crimes and his life online, described the 21-year-old as “young and head full of mush.”

‘He absolutely enjoyed gore’

When Teixeira wasn’t firing guns in the real world, he was playing with them online.

“He played a lot of video games, mostly shooters,” his close friend said, noting that Teixeira preferred games from the shooter’s point of view.

Teixeira’s gaming and political cultures overlapped, the friend observed. “Once you start getting into the more niche video games, a lot of those communities are much more conservative. I think he found a small place where his views got echoed back to him and made them worse.”

The interest in video games and conservative politics was accompanied by an acute obsession with violence, the friend said. “He would send me a video of someone getting killed, ISIS executions, mass shootings, war videos. People would screen-share it, and he would laugh very loudly and be very happy to watch these things with everyone else. He absolutely enjoyed gore.”

Friends may not have taken seriously Teixeira’s threats against his high school. But he voiced approval of some shooters, particularly when they targeted people of different races and faiths. Teixeira was especially impressed by a gunman’s rampage at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, in 2019, which left 51 people dead and 4o injured. “He was very happy that those people died,” the friend said, because they were Muslim. The shooter live-streamed his massacre as though he were in a video game.

The line between condoning violence and making light of it was slippery. When Teixeira was waiting on approval of his security clearance, he told his friend that he was particularly concerned that “jokes” he had made in the server might surface about “shooting up buildings” and “wanting to kill government agents.” These were frequent subjects of amusement.

“Most of the jokes he would make were about the ATF,” the friend said, referencing the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, the federal government’s premier gun control agency and a bête noire of the far right.

“He was very against gun control. And so he would talk about wanting to kill ATF agents or when ATF agents would show up to his house, like theoretically preparing your house so that they would die in some strange trap.”

In arguing that Teixeira should remain in jail while he faces charges, federal prosecutors pointed to his threats of violence in high school. But among online communities whose members hold “more extremist conservative views,” the friend said, “it’s really common to joke about killing government agents like that, so it never seemed worrying to me.”

Teixeira’s alleged hostility toward the government doesn’t explain his motivation for disclosing classified information. Other convicted leakers, including those like Teixeira who served in lower-level positions but had some of the highest levels of security clearance, were self-described whistleblowers trying to check perceived abuses or wrongdoings. Teixeira was trying to impress, and apparently mold, a group of teenagers.

“I think he did think it made him special,” the close friend said. “I think there was a part of him that felt like he was cool or important because he got that access.”

For the teenagers Teixeira had taken under his wing, the classified documents offered an education about how the world secretly worked. “He wanted to be seen as someone who’s powerful or looked up to,” the friend said. “He wanted them to be what he thought was the ideal, the ideal man.”

People help escort patients through the picketers. (photo: VICE)

People help escort patients through the picketers. (photo: VICE)

Abortion providers feared they’d see an increase in harassment and threats if Roe v Wade was overturned. They were right.

But in the year since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, the protests at her clinic have become so large and loud that, for the first time, Goodrick has had to enlist people to help escort patients through the picketers.

The men who show up to protest—because it is mostly men, Goodrick said—used to focus on praying. Now, they have a bullhorn; they scream and yell. “Not much we can do about it. So they stop cars, they scare people,” she said. “They try to stop me every time I come in.”

Goodrick’s not sure, exactly, where they come from. Maybe they’re locals. Maybe they’re out-of-state anti-abortion activists who are enraged that Arizona is continuing to permit abortions. But she does know that they disturb patients. “Some get angry, some get upset. Some talk to them,” Goodrick said. “Some feel like they have to, because they’re blocking their car and handing them something.”

As they prepared for Roe to be overturned, abortion providers and their supporters worried what would happen once clinics shuttered in red states. Would anti-abortion activists, deprived of their usual targets, cross state lines to protest at the remaining clinics? And if they did travel, would they become more aggressive?

The answer to both questions, nearly a year after Roe was struck down, appears to be yes, according to data released Thursday morning from the National Abortion Federation, which has spent decades tracking anti-abortion harassment and violence against clinics. As new abortion bans shuttered clinics across the country, states that have abortion protections on the books have seen a disproportionate surge in anti-abortion activity.

“The data shows that extremists do not stop at clinic closures and travel across state lines to target providers whose practices remain open,” Michelle Davidson, the federation’s security director, told reporters on a Wednesday press call. “Protected states saw a 100-percent increase in burglaries, a 200-percent increase in arson, [a] 538-percent increase in obstructions of clinic entrances, and an astounding 913-percent increase in stalking.”

States with abortion protections also experienced almost 41,000 reports of picketing in 2022, roughly 7,000 more than in 2021, the National Abortion Federation found.

Marva Sadler works at Whole Woman’s Health, a group of abortion clinics that recently opened up a location in New Mexico after closing all its Texas clinics. There, she told reporters, anti-abortion activists have started to do what’s called “schedule-packing,” filling up clinics’ schedules with appointments they don’t need and have no intention of showing up to.

“At the time when abortion is already hard to access, with so many clinics closing and the only ones having limited capacity and times, [anti-abortion activists] are successfully booking appointments to prevent even more patients from access to care,” Sadler said.

Anti-abortion activists, particularly ones who make a career out of opposing the procedure, have long traveled across the country to organize protests at abortion clinics—the bigger the better. Perhaps most famously, at the height of its fame in the 1990s, the anti-abortion group Operation Rescue summoned thousands of supporters to Wichita, Kansas, to besiege the city’s three abortion clinics. At least 2,600 people were arrested during this so-called “Summer of Mercy.”

Earlier this year, an anti-abortion group called Free the States held its annual conference in Wichita. Free the States is a self-proclaimed “abolitionist” organization, meaning its followers believe that abortion should be prosecuted like murder—and abortion patients should be prosecuted like murderers, an unpopular position among more mainstream anti-abortion circles.

Zachary Gingrich-Gaylord, who handles communications for a Wichita abortion clinic called Trust Women, estimated that the conference drew in a few hundred out-of-state supporters. But Trust Women has a tall metal fence that surrounds its property, as well as a parking lot that wraps around the entrance. Those barriers often deter would-be protesters.

“They did a big march down the street and came and did some photo opps at the clinic,” said Gingrich-Gaylord. “They were just a lot of spectacle. They wanted to turn the city upside down for Jesus.”

Still, these kinds of attention-grabbing maneuvers can leave a mark. Years after Operation Rescue left Wichita, one local abortion provider, Dr. George Tiller, remained a lightning rod among abortion opponents. He was shot to death in his church in 2009.

For abortion providers, this is the ultimate fear: that anti-abortion protests will explode into violence outside clinics. In 2022, there were four reports of arson against abortion clinics, compared to two in 2021, the National Abortion Federation found. Between 2010 and 2021, clinics received just two threats of anthrax or bioterrorism. In 2022 alone, they received four.

Julie Burkhart, who runs a Wyoming clinic that was set on fire by a suspected arsonist in June 2022, said that blaze shut down her clinic for 11 months and cost nearly $300,000 in repairs.

“This also caused great fear in our staff members. It shook the community,” Burkhart said, adding that anti-abortion protests continued even though the clinic was shut down. “We see anywhere from half a dozen to around 30 people who will come out to the clinic at any time. We even had to call law enforcement recently because protesters decided to trespass onto our property. And so this is definitely an ongoing issue and fear for us.”

The apparent increase in interstate travel by anti-abortion activists is particularly striking against the backdrop of abortion opponents’ efforts to limit people’s ability to cross state lines for the procedure. Idaho recently passed a first-of-its-kind law to charge people with “abortion trafficking” if they help minors leave Idaho for legal abortions without their parents’ knowledge.

“It’s absolutely hypocrisy,” said Erin Matson, executive director of the pro-abortion rights group Reproaction, which tracks anti-abortion activity. “They don’t necessarily live the way that they decreed that others should do.”

READ MORE  A demonstration in response to the death of Manuel Terán, who was killed during a police raid inside Weelaunee People's Park, the planned site of a "Cop City" project, in Atlanta. (photo: Cheney Orr/Reuters)

A demonstration in response to the death of Manuel Terán, who was killed during a police raid inside Weelaunee People's Park, the planned site of a "Cop City" project, in Atlanta. (photo: Cheney Orr/Reuters)

Three activists protesting the planned facility were charged under a little-known Georgia law, raising first amendment concerns

“Cop City” has sparked a broad-based protest movement in Atlanta and elsewhere, drawing global headlines when one environmental activist was shot and killed by police.

The latest arrests are “stunning and feel like overreach”, said Ken Paulson, director of the Free Speech Center at Middle Tennessee State University. They come under a law making it a felony to intimidate a law enforcement officer, and are in response to a printed flyer.

“It raises serious first amendment concerns,” the ACLU of Georgia wrote in an email. “It is also part of a broader pattern of the state of Georgia weaponizing the criminal code to unconditionally protect law enforcement and to silence speech critical of the government.”

Caroline Hart Tennenbaum and Abeeku Osei Vassall, of Atlanta, and Julia Dupuis, of Fullerton, California, were arrested 28 April, after leaving a flyer on mailboxes in Cartersville, a Georgia town about 45 miles north-west of Atlanta.

The flyer, exclusively obtained by the Guardian, called a policeman who lived in the neighborhood a “murderer” for participating in the 18 January shooting and killing of activist Manuel Paez Terán.

Local police initially charged the three with stalking, a misdemeanor, according to the county sheriff’s report. The activists heard officers debating whether to arrest them, with one asking another, “Isn’t this freedom of speech?” according to Lyra Foster, an attorney defending the arrestees. But the sheriff’s department was soon “advised that GBI [Georgia bureau of investigation] and FBI agents would be en route to interview the suspects”, according to the report.

The arrestees declined to be interviewed without a lawyer. Felony charges were added at some point.

A GBI spokesperson, Nelly Miles, would not answer questions about how or why the agency became involved. Neither would the FBI. Events surrounding the arrest led Stewart Bratcher, another attorney representing the activists, to wonder, “are they investigating a crime here or are they not liking what people are saying and therefore looking for a crime?”

The day after the arrests, all three were placed in solitary confinement without explanation, and left there for nearly four days, said Caroline Verhagen, mother of Dupuis. Georgia’s deputy attorney general, John Fowler, will be prosecuting the charges – an indicator of the state’s approach to the case.

The officer mentioned in the flyer, Jonathan Salcedo, was one of six named in a recently released document from the GBI, the agency charged with investigating Paez Terán’s death. The 18 January incident was the first time in US history police have shot and killed an environmental activist while protesting, catapulting the training center, known as “Cop City”, and the forest in which it will be built, into international news.

The state alleges the activist shot first and the case is with a special prosecutor.

Paez Terán, or Tortuguita, was one of dozens of activists camped in a public park south-east of Atlanta in mid-January, protesting against the “Cop City” project, planned for a part of the South River forest less than a mile away, as well as a developer’s plans to convert 40 acres (16 hectares) of the park into private land.

In the ensuing months, dozens of protesters have been arrested and charged under a state domestic terrorism law – another first in US law enforcement response to environmental activism. Now the state appears to have added a legal arrow to its quiver, after Salcedo called local police on the three activists driving through his neighborhood in Cartersville. Two were leaving flyers under the flags on mailboxes in front of each house, while a third was a passenger, according to Foster.

The sheriff’s report indicates Salcedo saw the van drive by, leaving flyers on mailboxes, and “felt harassed and intimidated by these actions and wished to have them prosecuted”.

The flyer features a large-type, bold-faced heading. Written as if by a resident, it reads: “Dear Neighbor, a murderer lives in our neighborhood!”

The same flyer was made for several of the officers involved in the shooting; only the name and street location of the officer’s residence varies. It explains some of the incident, including that Tortuguita’s body sustained 57 gunshot wounds, according to the DeKalb county autopsy report. The flyer does not include physical or other threats. It finishes by stating that the officer “has blood on his hands and he lives in our neighborhood”.

The activists’ intent, according to Foster, was “to raise awareness of a tragedy”.

Language on felony intimidation of a law enforcement officer was added in 2012 to a statute on intimidating “any officer in or of any court” that had been on the books for three decades.

“I’ve never come across a law that makes it a felony to intimidate a law enforcement officer or his family through speech or communication – unless there’s a very specific threat,” said Paulson.

“Saying unpleasant and insulting things about the way a public employee does his job is at the heart of free speech in America,” Paulson added.

Bratcher, with two decades of Georgia practice, said he had never seen the charge prosecuted. Thaddeus Johnson, a criminal justice professor at Georgia State University who is researching laws in 15 states with increased penalties for assaulting police officers, also had never seen the law used.

Meanwhile, the family of the one arrestee from out of state, Julia Dupuis, has been trying to understand both the jail’s treatment and the state’s charges. Verhagen, who lives in Massachusets, said that actions such as putting her daughter in solitary confinement and, afterward, leaving lights on all night, are “like a third-world jail”.

“I’m afraid they’re going to stretch this law on intimidation to fit their needs and my daughter winds up in jail for a couple of years,” she said.

READ MORE  A worker at an Amazon warehouse. (photo: Helen H. Richardson/Getty Images)

A worker at an Amazon warehouse. (photo: Helen H. Richardson/Getty Images)

Working at Amazon isn’t just physically taxing, it’s dangerous. Despite years of scrutiny and years of company spin, Amazon still has a serious injury rate more than double the rest of the industry.

This began to change two years ago, for an ominous cloud had appeared over the company’s carefully managed reputation. A September 2020 exposé by journalist Will Evans had revealed to the public what had long been apparent to the hundreds of thousands of Amazon’s warehouse workers: the firm’s novel techniques of labor extraction were inflicting a terrible toll on the health and well-being of its legions of pickers and packers.

As Evans reported, the rate of serious injury in the warehouses had steadily climbed in recent years, reaching an unprecedented peak of 7.7 per hundred workers in 2019, nearly double that of the industry standard. A second independent analysis, released by the Strategic Organizing Center (SOC) in June 2021, further demonstrated that the company’s extraordinarily high clip of worker injury is directly related to the punishing work rate inflicted on its workers.

Thus Bezos’s 2021 letter, his last as CEO, as well as Andy Jassy’s first effort as new CEO, issued last April, were distinguished by a new tone of defensiveness, as company leadership attempted to respond to a gathering storm of negative press.

Over the past two years, Amazon has focused its defense on three particular arguments, none of which stand up to even casual scrutiny.

“We Don’t Set Unreasonable Performance Goals”

First, the firm simply disputes the statistics compiled by the SOC, instead providing its own set of alternative facts. A particularly clumsy example is that the company includes its own workforce when computing the “industry average,” permitting Jassy to insist that the firm’s injury rates are “about average.” In 2022, for example, Amazon employed 36 percent of US warehouse workers, yet was responsible for no less than 53 percent of recordable injuries. A far more honest assessment would compare Amazon’s serious injury rate (6.6) and that of the remainder of the industry (3.2).

Second, when the company does acknowledge the safety problem, it brazenly denies what is obviously its source: “we don’t set unreasonable performance goals,” Bezos claimed in his April 2021 letter. And even more counterintuitively, the company has consistently maintained that the solution to a problem caused by innovative techniques of labor extraction is . . . more innovation. Thus Jassy, in his 2022 letter, asserts that what is needed is “rigorous analysis, thoughtful problem-solving, and a willingness to invent,” and further reassures investors that the firm will continue “learning, inventing, and iterating” until the problem is resolved. What he did not own up to is that Amazon’s rate of serious injury actually rose in 2022 by 13 percent.

Third, and most invidiously, Amazon has resorted to blaming workers themselves, in particular the hundreds of thousands of new people brought on during the past few years of rapid expansion. Since the great majority of the new hires are “new to this sort of work,” and since Amazon’s number crunchers have determined that most injuries occur within the first six months of employment, it is only natural that, as Jassy informed shareholders at the 2022 meeting, “your rates tend to go up.”

If this is indeed true, then it would seem that the company would have every incentive to retain as many of its warehouse workers as possible. Why expend so much effort to train up “industrial athletes” if most of them don’t stick around for the long haul? And yet turnover rates in the warehouses are astronomical; as the New York Times reported in 2021, even before the so-called Great Resignation, the company’s rate reached as high as 150 percent annually, meaning the entire workforce is replaced every eight months.

A measure of Amazon’s commitment to “Burn and Churn” is the “Pay to Quit” program that Bezos introduced in 2014, in which hourly employees are annually offered a payout — $1,000 initially, increased yearly up to a maximum of $5,000 after five years — to move along. (Facing the prospect of running out of human fuel, Jassy suspended the program for most employees in January 2022.)

Profits Over Safety

In retrospect, the May 2022 Amazon shareholder meeting probably represents the high tide of criticism of the firm’s labor practices. The blowback had reached such intensity that Amazon faced a record fifteen shareholder proposals, many of which concerned labor and safety issues. These included a call for board representation from an hourly worker, a request for a report on the company’s compliance with freedom of association standards as established by the International Labor Organization and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a proposal for an independent audit of working conditions in Amazon warehouses, and something of a Hail Mary demand from an enterprising Texas warehouse worker for the immediate suspension of all productivity quotas in the interest of safety.

But all fifteen proposals, each vigorously opposed by company leadership, were comfortably defeated — the demand to overturn the whole system of labor extraction was voted down by no less than 99.8 percent of Amazon investors.

If a solid majority of Amazon shareholders were untroubled by the company’s disgraceful safety record, they found the matter of the stock price more concerning. Although the firm had posted record profits for 2021 — more than $33 billion — disturbing trends had begun to appear in the second half of the year, triggering a precipitous fall in the stock price, from a peak of $186.12 in July 2021 to $104.10 by the May 24, 2022 meeting.

While there were many reasons for the plunge, much of it can be attributed to the lifting of COVID restrictions. Company leadership appears to have presumed that the meteoric, lockdown-driven growth in its consumer division was here to stay — that US consumers would not return to Walmart or Kroger. When the opposite happened, retail sales plummeted, and suddenly all that feverish expansion in the fulfillment network had become a burdensome drain on profits.

It should be stressed that criticism of the company’s injury mills has hardly abated in the twelve months since the May 2021 meeting, generating increased scrutiny from the government. At present, the company is under investigation from an unprecedented array of state institutions, including numerous state Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) branches, the federal OSHA office under the Department of Labor, and the Southern District of New York. Wherever these agencies have looked they have found an abundance of violations; federal investigations in five states between December 2021 and February 2022 netted the company a raft of citations, but Amazon has dug in its heels, appealing each and every one of them.

While all this was dutifully reported by the business press, the orientation of coverage began to change in the second half of 2022, as more and more reports of the company’s falling profitability began to appear. Shortly after the meeting, for example, Amazon announced a net loss of $2 billion for Q2, compared to a 2021 Q2 profit of $7.8 billion. With little improvement in the third and fourth quarters — the firm would reveal a net loss of $2.7 billion for 2022 as a whole — rumors began to swirl that Bezos himself would soon return to save the day.

Somehow, some way, mighty Amazon had become a money-losing operation again, and it was Jassy himself bearing the brunt of the blame. But at the same time, all the bad financial news served to distract from the issue of injuries, and if he had failed spectacularly in resolving the latter, there were many relatively easy measures he could take to address the former.

Like so many of his fellow tech chieftains, Jassy began to respond in November by announcing a plan for mass layoffs in the corporate sector: by April 2023, the company had eliminated no less than twenty-seven thousand employees, and a new round is currently underway. Wildly cheered on by Wall Street, the stock price — which in December had dipped all the way into the eighties — began to recover, and by the end of March it was back above $100, where it remains as of this writing.

“In Denial”

And yet the matter of the company’s shameful injury record was still out there, and given how poorly the firm had responded the past two years, a new strategy was needed. One of the cleverer moves of the SOC had been releasing its 2022 report on April 13, thereby preempting Jassy’s first shareholder letter, published the following day. Learning from its mistakes, this year Amazon preempted the preemptor, issuing a new edition of its own safety report on March 14. An exercise in spin, statistical manipulation, and outright lying, the “Delivered With Care” report managed to garner little if any attention, although as shall be discussed, this was probably the intention.

The SOC responded on April 13 with its own annual report, “In Denial: Amazon’s Continuing Failure to Fix Its Injury Crisis,” providing a comprehensive critique of “Delivered With Care” and managing to drum up at least some interest from the business press. Based on its own analysis, the SOC had to concede that Amazon can claim a reduction in its rate of serious injury, from 6.8 in 2021 to 6.6 in 2022 — a little less than 3 percent lower.

But there is significant reason to be skeptical of even this modest improvement, since the joint federal OSHA/Southern District of New York investigations found significant evidence of underreporting, resulting in a raft of subpoenas for documents relating to potential fraud (Amazon continues to fight the subpoenas in court). And even if the 6.6 figure holds up, it is still more than double than the rest of the industry.

Meanwhile, the content of Jassy’s second shareholder letter, published on April 14, suggests that the CEO has moved on to other concerns. Nowhere does the matter of workplace safety appear, nor does any mention of employee relations in general, save for an announcement that corporate employees must return to the office for a minimum of three days a week. First come the excuses: souring macroeconomic conditions, heightened competition, headwinds over at Amazon Web Services, etc. Then come the typical reassurances that company leadership is on top of things, that every effort is underway to return the firm to profitability.

As always, the emphasis is on “invention,” on the new sectors the company will soon come to dominate. Amazon is getting in on the chip boom. Advertising revenues are about to explode, as the firm’s ingenious algorithms outpace those of its competitors. Our own satellites will soon illuminate the not-yet-wired world.

Rather more concerning, at least to the multitude of warehouse workers, is the other side of the profitability equation, i.e. the reduction of costs. A year ago all the talk was of the herculean efforts — backed by $1 billion of new investment — to address safety issues. Here’s Jassy, summarizing his obsessive commitment to task:

When I first started in my new role, I spent significant time in our fulfillment centers and with our safety team. . . . At our scale . . . it takes rigorous analysis, thoughtful problem-solving, and a willingness to invent to get to where you want. We’ve been dissecting every process path to discern how we can further improve. . . . we’ll keep learning, inventing, and iterating until we have more transformational results. We won’t be satisfied until we do.

One year later, priorities have clearly changed. All that energy is now to be devoted to a very different enterprise, that of restoring profitability:

Over the last several months, we took a deep look across the company, business by business, invention by invention, and asked ourselves whether we had conviction about each initiative’s long-term potential to drive enough revenue, operating income, free cash flow, and return on invested capital.

The deep look certainly did not spare the warehouses, which are singled out as particularly egregious offenders:

A critical challenge we’ve continued to tackle is the rising cost to serve in our Stores fulfillment network (i.e. the cost to get a product from Amazon to a customer) — and we’ve made several changes that we believe will meaningfully improve our fulfillment costs and speed of delivery. . . . Over the last several months, we’ve scrutinized every process path in our fulfillment centers and transportation network and redesigned scores of processes and mechanisms, resulting in steady productivity gains and cost reductions over the last few quarters. There’s more work to do, but we’re pleased with our trajectory and the meaningful upside in front of us.

Another Year

That these efforts to boost productivity might conflict with the firm’s purported number-one priority in its warehouses — the safety of its workers — is a question no longer of concern to Jassy. If at the upcoming shareholder meeting, scheduled for May 26, he is once again asked about the matter, he’ll surely say something like this: “The safety team is all over that. See their recent report.”

Herein lies the heart of the problem: even operating a fulfillment network twice as dangerous as its competitors, Amazon simply cannot turn a profit on rapidly delivering packages for free or with minimal fees. For the consumer division to make money doing so, it will need to tighten the screws on its workers even more, extracting ever-more labor from their ailing bodies.

Perhaps the company can defy the laws of nature. Perhaps it can reengineer “scores of processes and mechanisms” in the interest of efficiency without simultaneously inflicting a greater toll on its pickers and packers. But it will be another year until we find out.

In the meantime, we have clearly reached an impasse. In a couple weeks, the shareholders will gather again, and the same activist groups will present their proposals for change. But it’s difficult to see how results could be better this year, given the firm’s financial struggles, which will surely take center stage. A better bet would be state intervention — new legislation, a serious clampdown from OSHA — but Amazon has thus far fended off these challenges with relative ease.

The ideal solution would be unionization across the entire fulfillment network, which would enable workers to negotiate a reasonable, safe, and humane work rate. But from the company perspective this simply cannot be allowed to happen, for even under the current regime of brutal labor extraction, Amazon appears to be incapable of turning a profit.

Amazon is operating injury mills — more than thirty-six thousand of its workers suffered serious injury last year. The company has clearly determined that such numbers are acceptable. Do the rest of us agree?

Amazon Responds

Since Jacobin started reporting on Amazon’s shareholder letters back in 2021, we have annually reached out for comment. After two years of ignoring our requests, the company came through this week. Here are our inquiries and Amazon’s responses:

1) In his 2020 shareholder letter, former CEO Jeff Bezos indicated that he was introducing a new leadership principle, that of making Amazon “Earth’s Safest Place to Work.” But when the leadership principles were updated on July 1, 2021, this was changed to “Success and Scale Bring Broad Responsibility.” Why was this change made? Is Amazon no longer committed to being Earth’s Safest Place to Work?

- When Jeff introduced the ideas of “Earth’s Best Employer” and “Earth’s Safest Place to Work” in the letter, he did not say anything about these being leadership principles. He talked about them as a “vision for our employee’s success.” Here’s what he said, lifted directly from the letter: Despite what we’ve accomplished, it’s clear to me that we need a better vision for our employees’ success. We have always wanted to be Earth’s Most Customer-Centric Company. We won’t change that. It’s what got us here. But I am committing us to an addition. We are going to be Earth’s Best Employer and Earth’s Safest Place to Work.

- Separately, three months following the shareholder letter, Amazon announced our two new leadership principles. If you read the description of the leadership principle “Strive to be Earth’s Best Employer,” you’ll find that safety is included in the definition, which states “Leaders work every day to create a safer, more productive, higher performing, more diverse, and more just work environment.”

- Our commitment to continuous safety improvement is reiterated in Amazon’s 2022 safety report, which was released in March. The report states “Our goal is to be the safest workplace within the industries that we are typically designated.”

- Andy Jassy has also underlined the importance of safety numerous times, including at the Bloomberg Tech Summit, in a CNBC interview with Andrew Ross Sorkin, and with CNBC’s Jon Fortt.

2) Also in his 2020 letter, Mr. Bezos noted that in his new role as Executive Chair, he was eager “to work alongside the large team of passionate people we have in Ops and help invent in this arena of Earth’s Best Employer and Earth’s Safest Place to Work.” But we have been unable to find any media reports that Mr. Bezos has indeed devoted any of his time over the past two years to the matter of worker safety. Could you provide details on his activities in this critical area?

- Amazon has done significant work to improve safety performance. We began releasing Delivered With Care, our safety, well-being, and health report, in 2022 and released it again this year (which you can download here). The report includes some of the following highlights:

- From 2019 to 2022, we saw our recordable incident rate improve by almost 24%. This includes an 11% year-over-year decline in our recordable injuries from 2021 to 2022.

- Since 2019, we reduced the number of injuries resulting in employees needing to take time away from work by 53%.

- In 2022, we engaged with over 1.4 million employees to understand safety sentiment and areas of improvement.

- From 2019 to 2022, we invested $1 billion in safety initiatives unrelated to COVID-19, and in 2023, we are investing another $550 million in safety initiatives. This is in addition to the $15 billion in COVID-related costs we incurred to make more than 150 significant process and procedural changes to help protect our employees and partners during the pandemic.

- We have reduced collision rates in our U.S. Delivery Service Partner network by 35%

- In 2023, Amazon became one of the first to sign on to the Department of Transportation’s nationwide call to action to reduce deaths on the roadways. Amazon committed another $200 million to continue upgrading safety technologies across our fleet of trucks and vans, including additional investments in collision avoidance technologies, strobing brake lights, and in-vehicle camera safety technology — just to name a few.

3) Since we began reporting on Amazon’s workplace injury record, the company has regularly referred to the fact that it employs more than 6000 safety professionals; Mr. Bezos cited the figure of 6200 in his April 2021 letter. Given the recent mass layoffs at the company — 27,000 roles eliminated with a new round currently underway — is this figure still accurate? How many positions have been eliminated in the safety division? What is the current figure?

- Amazon’s current number of workplace health and safety professionals is more than 8,000 globally.

READ MORE  The teenager was identified as Ángel Eduardo Maradiaga Espinoza. (photo: Reuters)

The teenager was identified as Ángel Eduardo Maradiaga Espinoza. (photo: Reuters)

The teenager was identified as Ángel Eduardo Maradiaga Espinoza, according to a tweet from Honduran foreign relations minister Enrique Reina. Maradiaga was detained at a facility in Safety Harbor, Florida, Reina said, and died Wednesday. His death underscored concerns about a strained immigration system as the Biden administration manages the end of asylum restrictions known as Title 42.

His mother, Norma Saraí Espinoza Maradiaga, told The Associated Press in a phone interview that her son “wanted to live the American Dream.”

Ángel Eduardo left his hometown of Olanchito, Honduras, on April 25, his mother said. He crossed the U.S.-Mexico border some days later and on May 5 was referred to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which operates longer-term facilities for children who cross the border without a parent.

That same day, he spoke to his mother for the last time, she said Friday.

“He told me he was in a shelter and not to worry because he was in the best hands,” she said. “We only spoke two minutes, I told him goodbye and wished him the best.”

This week, someone who identified himself only as one of her son’s friends at the shelter called her to say that when he had awakened for breakfast, Ángel Eduardo didn’t respond and was dead.

His mother then called a person in the U.S. who was supposed to have received Ángel Eduardo, asking for help verifying the information. Hours later, that person called her back saying it was true that her son was dead.

“I want to clear up my son’s real cause of death,” she said. He didn’t suffer from any illnesses and hadn’t been sick as far as she knew.

“No one tells me anything. The anguish is killing me,” she said. “They say they are awaiting the autopsy results and don’t give me any other answer.”

No cause of death was immediately available nor were circumstances of any illness or medical treatment.

HHS said in a statement Friday that it “is deeply saddened by this tragic loss and our heart goes out to the family, with whom we are in touch.” A review of health care records was underway, as was an investigation by a medical examiner, the department said.

White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre called the news “devastating” and referred questions about the investigation to HHS.

The asylum restrictions under Title 42 expired Thursday, with President Joe Biden’s administration announcing new curbs on border crossers that went into effect Friday. Tens of thousands of people tried to cross the U.S.-Mexico border in the weeks before the expiration of Title 42, under which U.S. officials expelled many people but allowed exemptions for others, including minors crossing the border unaccompanied by a parent.

This was the first known death of an immigrant child in custody during the Biden administration. At least six immigrant children died in U.S. custody during the administration of former President Donald Trump, during which the U.S. at times detained thousands of children above the system’s capacity.

HHS operates long-term facilities to hold children who cross the border without a parent until they can be placed with a sponsor. HHS facilities generally have beds and facilities as well as schooling and other activities for minors, unlike Border Patrol stations and detention sites in which detainees sometimes sleep on the floor in cells.

Advocates who oppose the detention of immigrant children say HHS facilities are not suited to hold minors for weeks or months, as sometimes happens.

More than 8,600 children are currently in HHS custody. That number may rise sharply in the coming weeks amid the shift in border policies as well as sharply rising trends of migration across the Western Hemisphere and the traditional spike in crossings during spring and summer.

Ángel Eduardo had studied until eighth grade before leaving school to work. Most recently he had been working as a mechanic’s assistant. He had been a standout soccer player in Olanchito in northern Honduras since he was 7 years old, his mother said.

The teenager had hopes of reuniting with his father, who left Honduras for the U.S. years ago, and earning money to support her and two younger siblings still in Honduras, his mother said.

He had migrated with his mother’s approval and financial support from his father in the United States, she said.

“Since he was 10 years old he wanted to live the American Dream to see his father and have a better life,” she said. “His idea was to help me. He told me that when he was in the United States he was going to change my life.”

READ MORE  Deforestation near Humaita, in Amazonas state, Brazil. (photo: Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

Deforestation near Humaita, in Amazonas state, Brazil. (photo: Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

Lula won last year's election pledging to end deforestation after years of surging destruction under his predecessor Jair Bolsonaro, but has faced continued challenges since taking office as environmental agency Ibama grapples with lack of staff.

Official data from space research agency Inpe showed that 328.71 square km (126.92 square miles) were cleared in the Brazilian Amazon last month, below the historical average of 455.75 square km for the month.

That interrupted two consecutive months of higher deforestation, with land clearing so far this year now down 40.4% to 1,173 square km.

Bolsonaro had slashed environmental protection efforts, cutting funding and staff at key agencies as he called for more farming and mining on protected lands.

Experts say it is still too early to confirm a downward trend, as the annual peak in deforestation from July to September lies ahead, but see it as a positive signal after rainforest destruction rocketed in late 2022.

"There are several factors, and the change in government might indeed be one of them," said Daniel Silva, a conservation specialist at WWF-Brasil. "The environmental agenda has been resumed, but we know time is necessary for the results to be reaped."

Lula has said it is urgent for Brazil to show his government is not only talking about protecting the environment, but that it is on its way to fulfill a commitment to end deforestation by 2030.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.