Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

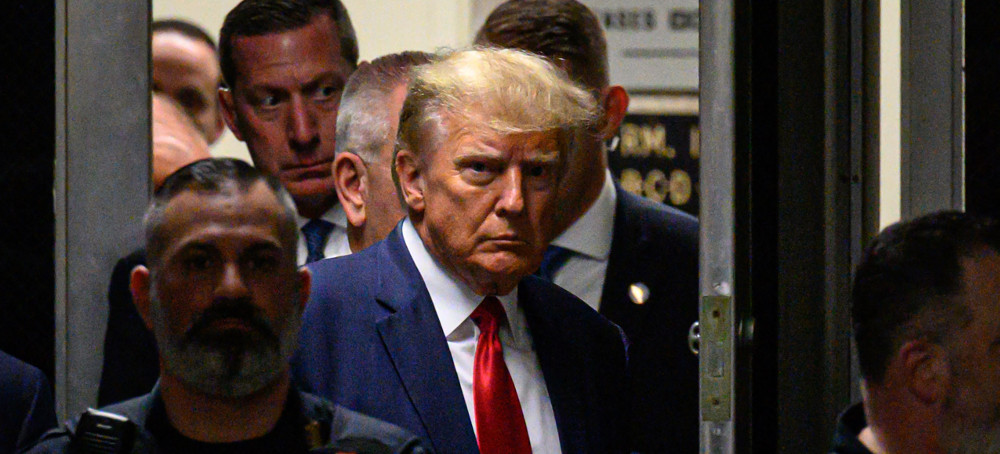

Years of interviews with potential witnesses provide insights into the Manhattan D.A.’s case.

The following year, after I wrote a story for The New Yorker about the payment to Sajudin and the role of A.M.I. in suppressing damaging stories about Trump, he agreed to talk to me for a podcast version of “Catch and Kill,” a book I wrote about tactics used by Harvey Weinstein and Donald Trump to suppress stories. At a studio in Brooklyn, in 2019, Sajudin recounted his experiences with Trump and A.M.I. to me for several hours. “You were asking me questions about this—this contract, and this gag clause,” Sajudin told me, recalling the encounter at his door. “I was, like, Holy crap, where’d this guy get this information from? How’d this get out? I says, ‘I’m not supposed to be sayin’ nothin’. Who would leak this?’ ” The New Yorker has uncovered no evidence that Trump fathered the child. The alleged daughter and her mother both declined to comment, and the father of the family told me it wasn’t true. But the transaction, which I confirmed by interviewing half a dozen A.M.I. employees with knowledge of the agreement, was part of a pattern of concealment, orchestrated by Trump and A.M.I., before the election. “The whole fact that they covered it up is what made this a big story,” Sajudin told me.

Unbeknownst to Sajudin, several months before he received his payment, Trump had met with Michael Cohen, his personal attorney at the time, and David Pecker, then the chief executive of A.M.I. The three men formalized a scheme in which Pecker and A.M.I. agreed to buy the rights to incriminating stories on behalf of Trump’s campaign and never publish them. The practice of purchasing a story in order to suppress it is known in tabloid circles as “catch and kill.”

The alleged scheme is at the heart of the thirty-four-count criminal indictment filed against Trump by a Manhattan grand jury which resulted in the former President’s arraignment on Tuesday. A statement of facts released by the District Attorney, Alvin Bragg, described the transaction with Sajudin, along with subsequent payments intended to secure the silence of two women who both claimed to have had affairs with Trump. Prosecutors argue that those payments were part of a years-long conspiracy to hide “damaging information from the voting public during the 2016 election.”

On Wednesday, when I reached out to Sajudin to ask him about his reaction to the indictment, he told me that Bragg’s office never got in touch with him. In a statement issued through his lawyer, Sajudin said, “I was in complete shock when I was informed by my Attorney that I was cited in the statement of facts related to former President Trump’s Indictment as I was not given any forewarning that I would be included. I was never asked to appear before the Grand Jury, nor was I ever interviewed by the District Attorney’s Office.” Other sources also told me they had not been contacted—among them was Daniel Portley-Hanks, the private investigator hired by A.M.I. to look into the accuracy of Sajudin’s rumor. “I even recently called the prosecutor’s office and gave them my information. No one ever called me back,” Portley-Hanks told me this week. “Their investigators need to do a better job if they want this case to stick. Right now, all they have is David Pecker’s word that what he did was under the direction of Donald Trump. However, other people in that office also knew what was going on.”

Douglas Cohen, a spokesperson for Bragg’s office, declined to comment. A person with knowledge of the investigation told me that prosecutors had contacted only the witnesses that they felt were necessary at this stage of the legal process, and had avoided some calls in the interest of preventing leaks.

The decision highlights the unique perils of the Trump indictment, legally and politically. In interviews, several former prosecutors said the decision not to interview Sajudin was risky and wondered why Bragg did not seek information from someone in a position to either support or rebut the evidence being presented. “This was a public investigation for a long time,” Marc Agnifilo, a former prosecutor in Manhattan, said. “So I can’t think of any reason to indict the case without interviewing this person.” A former prosecutor who was involved in the trial of a Trump associate and asked not to be named, warned, “When you are trying one of the most important cases in our lifetime, you want to make sure you know everything about your case so you’re not surprised about anything that may come up at trial.”

Others said that they understood the decision and did not fault it. The intense public interest in the case meant that prosecutors had to go to great lengths to keep their investigation under wraps. Danya Perry, a former Assistant U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, told me that prosecutors didn’t need Sajudin’s testimony to meet their burden of proof before the grand jury. Pecker and other witnesses could verify that the payment was made to the doorman. “They have the story now from documents and two witnesses,” Perry said. Whether he fathered a child or had these affairs “is legally irrelevant.”

“It’s like a corporate mob, so to speak,” Dino Sajudin said, of his time at Trump Tower. “They’ll try to be nice to you in the beginning . . . and then, if that doesn’t work, they try to strong-arm you.”

A.M.I.’s payment to Sajudin was the first of three described by prosecutors. Eight months after paying Sajudin, A.M.I. paid the first of two women, a former Playboy model named Karen McDougal, a hundred and fifty thousand dollars and promised her a number of career opportunities—including magazine covers and a monthly fitness column—in exchange for her silence. Several months later, amid concerns about the cost and the potential legal ramifications of the scheme, A.M.I. referred the second woman—the adult-film actor Stephanie Clifford, who performs as Stormy Daniels—to Cohen, who paid her a hundred and thirty thousand dollars through a shell company. Clifford had, for years, been shopping the story of her sexual liaison with Trump, which she says took place in 2006, shortly after Trump’s wife, Melania, gave birth to their son, Barron.

McDougal, who is named as “woman one” in the indictment documents, did not respond to a request for comment this week. When she spoke with me in 2018 for a New Yorker story and again in 2020 for the podcast, she expressed regret. “Knowing now what’s going on behind the scenes,” McDougal told me, “I feel like I was part of a major coverup in history.”

Prosecutors have charged Trump with thirty-four felony counts of falsifying business records, apparently related to payments reimbursing Cohen after he paid Clifford. Prosecutors will seek to establish that the offenses, which would typically be classified as misdemeanors, were undertaken with the goal of commissioning another crime, allowing them to be charged as felonies. The person with knowledge of Bragg’s investigation noted that prosecutors are not required by law to specify that second crime. “Flexibility and options are key,” that person told me. Prosecutors intend to “save that decision” for when they “feel like it’s most prudent.” In a press conference this week, Bragg referenced multiple potential second crimes, including violations of state and federal election law.

Trump, in his own press conference this week, said that the charges were a politically motivated attempt by Bragg, a Democrat, to prevent him from winning reëlection. “Everybody that has looked at this case, including RINOs and even hardcore Democrats, say there is no crime and that it should never have been brought,” he said. Cohen and Pecker, who are both expected to testify on behalf of the prosecution, did not respond to requests for comment.

Sajudin, now in his fifties, sports a goatee and slicked-back hair. He grew up in Brooklyn in a large Italian American family. Sajudin told me that he spent his youth working in construction and asbestos abatement, witnessing mob associates pay off building inspectors. In 2008, he began working as a doorman at Trump Tower. “Whenever Trump would come to the building, he would quite often give everybody a hundred-dollar bill,” he recalled in the 2019 interview. On the other hand, he said, “It’s like a corporate mob, so to speak.” He added, “They’ll try to be nice to you in the beginning, to try and get what they want. And then, if that doesn’t work, they try to strong-arm you.”

At Trump Tower, Sajudin clashed with a woman who worked as the building’s concierge and who had previously been Trump’s housekeeper. Sajudin recalled her making lavish purchases that seemed incongruous with her income and said that she enjoyed impunity from the building’s management. “Every time she had an argument with somebody, the first words to come out of her mouth is, ‘I will call Mr. Trump. I will call Mr Trump,’ ” Sajudin told me. He said that he raised the matter with superiors, including Matthew Calamari, Trump’s longtime bodyguard, who’d risen through the ranks of the Trump Organization to become its C.O.O. Calamari, he said, “got really loud and rude and told me, he says, ‘You know, you need to, like, let it go.’ He says, ‘If you had Trump’s kid, you could do whatever you want.’ ” The next time Trump arrived at the building, Sajudin said, he received an unusually large tip from Calamari. “Several hundred bucks,” Sajudin recalled. “I assumed he was being so nice to me because he wanted me to be quiet.”

When Sajudin, agitated by his disputes with the concierge, continued to press the subject, he said that Calamari called him into a second meeting, in a dim office with the blinds drawn. Sajudin recalled that Calamari told him, “We think of you like family. We work together. But you need to let this situation go.” Calamari then shook his hand and asked, “Are we clear?” “He wouldn’t let go of my hand,” Sajudin added. “It was like a movie. You know, it was like watching ‘Goodfellas.’ ” (Calamari has declined repeated requests for comment.)

After his encounter with Calamari, Sajudin felt that his standing in the Trump Organization deteriorated. “I definitely feel I was blacklisted,” Sajudin told me. “They probably don’t want a person with this information working in a building in Manhattan.” Sajudin eventually departed the organization—he said by mutual agreement. As he sought another job, it occurred to him that he could monetize the rumor. He contacted Globe, and then the Enquirer. A reporter from the Enquirer responded quickly, offering him six figures, which was later reduced substantially when Sajudin said that he didn’t want his name attached.

In the fall of 2015, Sajudin found himself in a hotel room in rural Pennsylvania, taking a polygraph test for the Enquirer, which he passed. He signed an initial agreement with the tabloid to grant it exclusive rights to the story. Soon after, during a meeting with an Enquirer reporter at a nearby fast-food restaurant, he also signed a revised contract, which included a more robust nondisclosure clause. “If I did speak on the story, I could be subject to a million-dollar fine,” he said.

A.M.I. employees were divided as to the truth of the underlying rumor. Some questioned Sajudin’s credibility. In 2014, a Web site registered through a service that obscures the identity of the author claimed that Sajudin had made similar accusations against a Trump Tower resident. Sajudin told me that he continued to believe the Trump paternity rumor and defended his credibility. “When I tell you it’s the truth, it is the truth,” he said. “No one would risk all this to make up stories.”

Eight months after the payment with Sajudin, A.M.I. finalized its deal with McDougal. Several months after that, Michael Cohen paid off Stormy Daniels. Soon after, Trump was elected President.

In April, 2018, F.B.I. agents raided Cohen’s hotel and office, in part to gather information on the A.M.I. scheme, and The New Yorker published my initial reporting on the payment to Sajudin. “Oh, shit,” Keith Davidson, the lawyer who represented both McDougal and Clifford, told me in 2019, describing his reaction to the raid. “Oh, shit, shit, shit.” Cohen was ultimately convicted and sentenced to three years in prison for campaign-finance violations, tax evasion, and lying to Congress. A.M.I. admitted to the scheme, and struck a non-prosecution agreement with federal authorities. Trump was not charged at the time. (Cohen and Davidson did not respond to requests for comment this week.)

During our interviews, McDougal told me that she believed that “catch and kill should be illegal in a lot of situations and positions.” She added, referring to elected officials, “If you’re working for your country, you have to be up front with this stuff.” Sajudin told me that he had been taken aback by the escalating significance of his story. As the trial of the former President proceeds, interest in A.M.I.’s transactions related to Trump will likely intensify. “I thought this was just, like, a tabloid,” Sajudin told me. “Now I see it’s a lot more than that.”

READ MORE  Boxes of mifepristone, one of two drugs used in medication abortions. (photo: Evelyn Hockstein/Reuters)

Boxes of mifepristone, one of two drugs used in medication abortions. (photo: Evelyn Hockstein/Reuters)

Federal lawsuit by conservative groups followed the Supreme Court’s elimination of the constitutional right to abortion last June

The dueling opinions — one from Texas and the other from Washington state — concern access to mifepristone, the medication used in more than half of all abortions in the United States and follow the Supreme Court’s elimination of the constitutional right to the procedure last year. It appears inevitable the issue will move to the high court, and the conflicting decisions could make that sooner rather than later.

The highly anticipated and unprecedented ruling from Texas puts on hold the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of mifepristone, which was cleared for use in the United States in 2000. It was the first time a judge suspended longtime FDA approval of a medication despite opposition from the agency and the drug’s manufacturer. The ruling will not go into effect for seven days to give the government time to appeal.

U.S. District Judge Matthew J. Kacsmaryk, a nominee of President Donald Trump with long-held antiabortion views, agreed with the conservative groups seeking to reverse the FDA’s approval of mifepristone as safe and effective, including in states where abortion rights are protected.

“The Court does not second-guess FDA’s decision-making lightly,” Kacsmaryk wrote in the 67-page opinion. “But here, FDA acquiesced on its legitimate safety concerns — in violation of its statutory duty — based on plainly unsound reasoning and studies that did not support its conclusions.” He added that the agency had faced “significant political pressure” to “increase ‘access’ to chemical abortion.”

In a competing opinion late Friday, a federal judge in Washington state ruled in a separate case involving mifepristone that the drug is safe and effective. U.S. District Judge Thomas O. Rice, who was nominated by President Barack Obama, ordered the FDA to preserve “the status quo” and retain access in the 17 states — along with D.C. — that are behind the second lawsuit, which seeks to protect medication abortion.

Within hours of the Texas ruling, the Justice Department and drug manufacturer Danco Laboratories filed their notice of appeal. Attorney General Merrick Garland said the government would ask the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit to allow the FDA to maintain approval of the pill pending the outcome of the case. Garland said in a statement that the department was still reviewing the decision out of Washington state.

President Biden criticized the Texas ruling in a statement Friday, saying the court had “substituted its judgment for FDA, the expert agency that approves drugs. If this ruling were to stand, then there will be virtually no prescription, approved by the FDA, that would be safe from these kinds of political, ideological attacks.”

He called the decision “another unprecedented step in taking away basic freedoms from women and putting their health at risk.”

The conflicting and complicated decisions will likely put pressure on the FDA and the Biden administration to determine how to enforce the new mandates set by these rulings.

The judge’s decision in Texas to pause his own ruling for a week while the administration seeks review in the 5th Circuit, and the contrary ruling in Washington state, means no immediate change in the status quo. But the Biden administration might not want to wait for the 5th Circuit to act before bringing the issue to the Supreme Court.

It could ask the justices to put Kacsmaryk’s decision on hold while legal battles continue. The justices might then face a decision about whether to hear the case in the normal course of business — which would mean scheduling a hearing in the new term that begins in October — or to take up the case on an emergency basis.

The court has done that in some recent cases. But that could cause serious problems for a court that has one round of oral arguments left in the current term, and has issued few opinions in cases already argued and none in the biggest disputes involving election law, affirmative action and religious and LGBTQ rights.

Medication-induced abortion has become increasingly contentious since the high court overturned the nearly 50-year-old Roe v. Wade decision last June, which allowed states to outlaw or sharply restrict the procedure.

Abortion clinics reached Friday night emphasized that the Texas ruling would not affect their care for the next seven days. Even then, if Kacsmaryk’s ruling takes effect, several providers said they would not stop prescribing mifepristone until they are instructed to do so by the FDA.

Many abortion clinics have been preparing for the Texas ruling for months. If they are forced to stop providing mifepristone, they say, they will continue to provide surgical abortions and, in many cases, a different medication abortion regimen that includes only misoprostol, the second drug in the standard two-step medication abortion regimen.

“Nothing changes for us tomorrow,” Amy Hagstrom Miller, chief executive of Whole Woman’s Health, a network of abortion clinics, texted a group of her staff at 6:51 p.m., less than an hour after the ruling was issued.

Whole Woman’s Health will not stop prescribing mifepristone until it receives directions from the FDA, Hagstrom Miller said.

The U.S. fight over abortion

The Texas lawsuit was brought by the legal group Alliance Defending Freedom on behalf of antiabortion medical organizations and four doctors who say they have treated patients with mifepristone. It claimed the FDA did not have the power to approve the drug and takes issue with the agency’s easing of restrictions on the pill through the years.

In a statement Friday, the group’s senior counsel, Erik Baptist, said the FDA “never had the authority to approve these hazardous drugs and remove important safeguards. This is a significant victory for the doctors and medical associations we represent and more importantly, the health and safety of women and girls.”

Public health professionals and legal experts had denounced the lawsuit as unsupported by scientific evidence. The FDA has repeatedly found the two-step medication abortion protocol to be a safe and effective alternative to surgical abortions. The drug manufacturer, Danco, and the Justice Department have called the plaintiff’s claims baseless.

In response to the ruling, Abby Long, Danco’s director of public affairs, said in a statement, “This is a dark day for public health, especially reproductive rights and the reliance on science and medical expertise to guide decisions about what drugs are safe and effective and should be available to patients.” The court’s ruling, she said, “fails to account for the meticulous, well-documented FDA decision-making process.”

In his ruling, Kacsmaryk was highly critical of the FDA’s decisions over the years to loosen restrictions on how the pill is administered and faulted the FDA for “lax reporting requirements.”

The FDA, he wrote, “took its chemical abortion regimen — which had already culminated in thousands of adverse events suffered by women and girls — and removed what little restrictions protected these women and girls.”

He found that suspending approval was in the public interest because of the drug’s potential side effects.

“Many women also experience intense psychological trauma and post-traumatic stress from excessive bleeding and from seeing the remains of their aborted children,” he wrote.

Throughout the ruling, Kacsmaryk used language often invoked by the antiabortion movement, referring to abortion providers as “abortionists” and characterizing mifepristone as being used “to kill the unborn human.” Kacsmaryk, a conservative Christian with a long history of antiabortion views, issued the ruling on Good Friday.

Nathan Cortez, a law professor and FDA scholar at Southern Methodist University, said the judge’s ruling was “about as out-there as you can imagine.”

“The sources he cites and the terminology he uses also read very much like the opinion of an antiabortion crusader rather than an impartial judge,” said Cortez, who was one of 19 FDA experts who signed onto an amicus brief supporting the agency’s position that the pill had been properly approved.

“It cannot be overstated that courts just don’t override FDA’s judgment on whether to approve new drugs and what conditions to place on their marketing — and for good reason: again, most judges know these are incredibly complex decisions.”

Both sides made their cases to Kacsmaryk on March 15 during a four-hour hearing that focused on the technical aspects of federal drug regulation and FDA processes. Kacsmaryk seemed aware of the stakes and how historic this case could be, asking the lawyers about legal precedent and his authority to essentially override the FDA’s approval of a drug more than 20 years ago.

The lawsuit in Washington state was filed in February — three months after the challenge to mifepristone was filed in Texas. Washington Attorney General Bob Ferguson said the FDA imposed too many restrictions on mifepristone and asked the judge to order the federal government to make the medication easier for people to obtain.

While these legal proceedings are entirely separate from the one in Kacsmaryk’s Texas courtroom, it appears to serve as at least a partial rebuke to that lawsuit. In a February news release announcing his lawsuit, Ferguson noted that Washington was one of 21 states along with D.C. to file a brief in the Texas abortion pill case, urging Kascmaryk to allow the FDA to maintain its approval of the abortion pill. Ultimately, Rice did not order the FDA to roll back any of its restrictions of mifepristone in his Friday ruling, but he ruled that the status quo must remain.

In a two-step medication abortion, a patient first takes one mifepristone pill, which terminates the pregnancy. About 24 hours later, the patient typically takes a four-pill dose of misoprostol — a drug introduced in 1973 to treat stomach ulcers — to soften the cervix and prompt contractions that expel the embryo or fetus. While misoprostol is widely used on its own to perform abortions around the world, studies show it is less effective than the two-step regimen, and usually causes more cramping and bleeding.

The Texas lawsuit targeted the FDA’s loosening of restrictions on the abortion pill, including the agency’s decision in 2016 to say the drug could be used through 10 weeks of pregnancy, up from the seven-week limit in the initial approval. The FDA took steps this year to ease access to the medication in states where its use is legal, allowing retail pharmacies to dispense the pills directly from doctors or by mail.

Abortion providers expressed concern Friday that Kacsmaryk’s ruling could curtail their ability to send abortion pills — both mifepristone and misoprostol — through the mail. Many patients rely on telehealth services that mail pills, especially those living in rural areas, far from brick-and-mortar clinics.

In his ruling, Kacsmaryk repeatedly invoked the Comstock Act, a 150-year-old law that prohibits mailing any drug used “for producing abortion,” which has not been applied for decades. Arguments that the Comstock Act no longer applies are “unpersuasive,” Kacsmaryk wrote, adding that federal criminal law declares abortion pills “nonmailable.”

READ MORE  Ukrainian troops prepare to fire a mortar toward Russian positions on the frontline in the eastern region of Donetsk on Wednesday. (photo: Genya Savilov/AFP)

Ukrainian troops prepare to fire a mortar toward Russian positions on the frontline in the eastern region of Donetsk on Wednesday. (photo: Genya Savilov/AFP)

The revelation set off alarm bells at the Pentagon, which is trying to determine how the material was leaked or stolen.

"We are aware of the reports of social media posts and the department is reviewing the matter," said Pentagon Deputy Press Secretary Sabrina Singh.

The Department of Justice has opened an investigation into the leaks and has been in communication with the Department of Defense, DOJ spokesperson Xochitl Hinojosa told NPR in a statement. The DOJ declined further comment.

The documents include maps of Ukraine and charts on where troops are concentrated and what kinds of weapons are available to them. The online posts show photos of physical documents that were folded and creased in some instances.

One is labeled "Top Secret," and is titled "Status of the Conflict as of 1 March." It gives a detailed battlefield summary on that particular day, though it's not clear why the documents are emerging now, more than a month after they were prepared.

The story was first reported by The New York Times. NPR has also seen the documents online, but is not publishing links to them.

Military analysts say the documents appear genuine, but think the original versions were likely altered in some places.

For example, one chart puts the Ukrainian death toll at around 71,000, a figure that is considered plausible. However, the chart also lists the Russian fatalities at 16,000 to 17,500. The Russian count is believed to be much larger, though neither side releases overall casualty figures.

Also, the chart with the death toll is printed on a black background, while all the other charts on the page are printed on a white background.

It's not clear how valuable the information might be to the Russian military.

Documents do not contain battle plans

The papers published online do not reveal Ukrainian battle plans for a widely expected offensive this spring. Still, they do mention combat brigades that Ukraine is assembling and when they should be ready to fight.

The identity of those who published the documents, and their motives, are not known. Putting the documents online alerted the Pentagon that they had been leaked or stolen, which might not have been otherwise known.

Before the war, Russian intelligence agencies were considered extremely active in Ukraine. Russia and Ukraine were both part of the Soviet Union, and Russian President Vladimir Putin, a former intelligence agent himself, had meddled in Ukrainian affairs throughout his time in power, including an initial 2014 military incursion.

In the runup to Russia's full-scale invasion in February 2022, the U.S. intelligence community intentionally publicized some information about the Russian plans.

The goal was to persuade the international community that the threat of a Russian attack was real. CIA Director William Burns has made multiple visits to Ukraine and spoken about the ongoing intelligence sharing between the two countries.

Prior to the war, some U.S. officials expressed concerns that Russian intelligence could gain access to the information the U.S. was providing to Ukraine. But the intelligence sharing among the U.S., NATO and Ukraine has been seen as extremely valuable in helping the smaller Ukrainian military fight off the Russians.

On the battlefield, the Russians continue to press a months-long offensive in eastern Ukraine, in and around the town of Bakhmut, but the Russian military has only made progress in heavy fighting that has claimed thousands of casualties on both sides.

The Ukrainians are widely expected to launch their own offensive this spring, and most analysts expect it to focus on areas controlled by Russian troops in southeastern Ukraine.

A senior Ukrainian security official, Oleksii Danilov said that no more than five people in the world know when and where the counteroffensive will begin.

READ MORE  Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov. (photo: AFP)

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov. (photo: AFP)

Moscow wants any Ukraine peace talks to focus on creating a "new world order," Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said on a visit to Turkey on Friday.

He also threatened to abandon a landmark grain deal, which Turkey helped broker, if obstacles to Russian exports remain.

"Any negotiation needs to be based on taking into account Russian interests, Russian concerns," Lavrov said.

"It should be about the principles on which the new world order will be based."

He added that Russia rejects a "unipolar world order led by 'one hegemon'."

Russia has long said it was leading a struggle against the United State's dominance over the international stage, and argues the Ukraine offensive is part of that fight.

The Kremlin this week said it had no choice but to continue its more than year-long offensive in Ukraine, seeing no diplomatic solution.

The beginning of the offensive saw rising fears of a global food crisis as Russia and Ukraine are major exporters of grain and other agricultural products.

Lavrov however said Russia may pull out of the landmark deal that allowed vital exports to leave blocked ports in the Black Sea.

"If there is no further progress in removing barriers to the export of Russian fertilizers and grain, we will think about whether this deal is necessary," Lavrov said.

On the eve of the visit, Moscow said it extended the agreement "as a gesture of goodwill for another 60 days."

Russia has repeatedly threatened to abandon the agreement that has allowed the export of more than 25 million tons of grain.

Moscow has been complaining that its side of the agreement, promising the right to export fertilizer free from Western sanctions, is not respected.

Turkey is pushing for a 120-day extension in compliance with the original agreement, which was negotiated by Ankara and the United Nations last July.

READ MORE  Wisconsin Supreme Court candidate Janet Protasiewicz, center, holds hands with Wisconsin Supreme Court Judges Rebecca Dallet, on left, and Ann Walsh Bradley, on right, after the race was called for her during a watch party in Milwaukee on Tuesday. (photo: Evelyn Hockstein/Reuters)

Wisconsin Supreme Court candidate Janet Protasiewicz, center, holds hands with Wisconsin Supreme Court Judges Rebecca Dallet, on left, and Ann Walsh Bradley, on right, after the race was called for her during a watch party in Milwaukee on Tuesday. (photo: Evelyn Hockstein/Reuters)

emocrats made clear to voters that the Wisconsin Supreme Court election this week centered on one key issue: giving liberals a majority on the court so they can overturn the state’s abortion ban.

But the race was also about getting the votes to redraw gerrymandered legislative and congressional districts. And protecting the outcome of the 2024 presidential election. And, potentially, a long list of other issues.

Wisconsin has a Democratic governor and a Republican legislature, so many of its most consequential disputes are resolved by the state Supreme Court. Milwaukee County Judge Janet Protasiewicz, a liberal, beat former justice Daniel Kelly, a conservative, by 11 points. When she is sworn in on Aug. 1, liberals will obtain a 4-3 majority, ending a 15-year run of conservative control of the court.

Exactly what will happen in the coming years is uncertain because so much depends on what cases get filed and which ones the justices decide to take. Here’s a look at some of the issues that could come before the court, starting with the cases that brought this week’s election so much attention:

1

Abortion

Wisconsin abortion providers stopped offering the procedure last summer after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision that guaranteed a right to abortion. Soon after, Gov. Tony Evers (D) filed a lawsuit to overturn the 1849 law that bans all abortions except those needed to save the life of a mother. The case is now before a trial judge and is expected to eventually make it to the Supreme Court. Protasiewicz has repeatedly professed her support for abortion rights and the new majority is expected to invalidate the ban.

2

Redistricting

The state Supreme Court approved election maps last year that gave Republicans nearly two-thirds of the seats in the state legislature and six of the state’s eight congressional seats. Liberal groups plan to file a lawsuit this summer in hopes of getting more neutral lines. The majority is sure to establish new districts — the liberals already on the court dissented over how the court drew the lines, and Protasiewicz called the maps “rigged” during her campaign. Whether the justices could put new districts in place for the 2024 election is less certain because they would need to act by the spring.

3

2024 results

The state Supreme Court rejected challenges in 2020 to Joe Biden’s presidential victory brought by Donald Trump and his allies in a string of 4-3 rulings, with one conservative joining the court’s liberals. Democrats feared they could not count on the conservative justice in future cases, and now they won’t have to rely on his vote if there is a challenge over the 2024 results.

4

Voting rules

Challenges to voting rules happen every campaign cycle and this new majority is expected to generally support expanding voting rights. One lawsuit to watch involves a bus used by city officials in Racine to conduct early voting.

5

Voter ID

Wisconsin’s voter ID law, approved in 2011, withstood a decade of legal challenges. Given the new majority, liberal groups see an opportunity to bring new litigation over the issue.

6

Veto power

Wisconsin governors have some of the broadest veto powers in the country, allowing them to creatively strike out parts of budgets and some other bills. The state Supreme Court in 2021 issued a muddled decision that limited the veto authority of Evers but created as many questions as it answered. The new majority could restore many or all of his veto powers, strengthening his hand as Republican lawmakers write the state budget.

7

Union rights

Republicans in 2011 effectively eliminated collective bargaining for most public workers in Wisconsin, sparking massive protests, waves of recall elections and seemingly endless court battles. Courts upheld the law, known as Act 10, but unions could bring a new lawsuit over the issue.

8

School vouchers

State lawmakers in 1990 created the country’s first school voucher program in Milwaukee and have expanded it ever since. While the program is well established and now available across the state, opponents could now launch challenges over aspects of it.

9

Public records

Republican lawmakers over the last two years have lost lawsuits over withholding records from the public about their controversial review of the 2020 election. Assembly Speaker Robin Vos (R) has been appealing those decisions, but he will have a tough time winning before the high court.

10

Republican electors

The state’s presidential electors are suing the 10 Republicans who in 2020 filed official-looking paperwork claiming to be the state’s rightful electors and seeking to name Trump as the state’s winner instead of Biden. The case is novel and probably would have gone nowhere with the conservative majority. Those bringing the case will still face difficulties but could have an easier time convincing the new majority that the Republican electors should pay fines.

11

Lame-duck laws

Evers and state Attorney General Josh Kaul (D) first won their offices in 2018, but before they were sworn in, Republican lawmakers approved last-minute laws limiting their power. Courts have upheld the bulk of those laws so far, but litigation continues over an aspect of them that allows legislators to get involved in lawsuits that ordinarily would be handled by the attorney general alone.

12

Trans students

Conservatives have sued over school policies that allow students to change their names or pronouns in class without parental consent. Those bringing the cases will have a more difficult time before the new majority.

13

Court transparency

In 1999, the Wisconsin Supreme Court became one of the first courts in the country to hold its administrative meetings in public so that anyone could watch their deliberations on court policies and budgets. The live-streamed meetings at times turned nasty, and conservatives in 2012 ended the practice so they could conduct the meetings behind closed doors. The liberals have said they will start holding the meetings in public again.

14

A new chief justice

The court last month gave conservative Justice Annette Ziegler another two-year term as chief justice. The new majority wants to name liberal Justice Ann Walsh Bradley as chief justice. It’s not clear whether the liberal justices will wait until Ziegler’s term as chief justice ends in March 2025 to do that or try to do it sooner.

15

Judicial ethics

A decade and a half ago, conservatives on the court adopted ethics rules written by a business lobbying group that say justices do not have to step aside from cases involving campaign contributors. Liberals have railed against the policy and pushed for change. Now they will have a chance to write new rules. What precise policies they might adopt are unclear. Conservatives are sure to use the debate to question whether Protasiewicz can participate in the abortion and redistricting cases after spelling out her views on those issues.

16

Attorney sanctions

A judge filed an ethics complaint last year against conservative former state Supreme Court Justice Michael Gableman for his conduct as the attorney leading Republican lawmakers’ review of the 2020 election. Liberals on the court are likely to have more appetite to discipline Gableman than his conservative former colleagues would have.

The next Supreme Court election is in April 2025, when Bradley’s 10-year term is up. Bradley announced Tuesday she plans to seek reelection, and the race will give conservatives an opportunity to try to reclaim the majority.

READ MORE  Officials who have used Spillman Technologies' software in California, Colorado and Texas allege it has created "huge safety risks" and led to at least one death. (photo: NBC News)

Officials who have used Spillman Technologies' software in California, Colorado and Texas allege it has created "huge safety risks" and led to at least one death. (photo: NBC News)

Officials who have used Spillman Technologies’ software in California, Colorado and Texas allege it has created “huge safety risks” and led to at least one death.

Officials who have used Spillman Technologies’ software in California, Colorado and Texas allege it has crashed in the midst of 911 calls, forcing dispatchers to frantically take notes by hand while emergencies were unfolding. They say it has failed to provide the fastest routes for traveling to the scenes of emergencies, costing precious time for first responders and those they’re trying to help. And they say it has lost police reports about alleged crimes, sometimes as officers were in the midst of writing them.

Spillman Technologies, which was acquired by Motorola Solutions in 2016, provides dispatch and records management software systems to more than 1,000 agencies nationwide, according to a 2016 press release from Motorola. Officials say that while those services are crucial for law enforcement agencies, the software has failed to deliver them as promised.

Eleven spokespeople for Motorola Solutions did not respond to phone calls and emails from NBC News containing a dozen detailed questions summarizing the allegations in this story.

A lost allegation of child sex abuse

Sgt. Rob Garnero, a spokesperson for the Redding, California police department, last month blamed Spillman for losing a 2018 allegation that Ryan Rovito, 34, had “several hundred” child sex abuse images on his computer, which authorities discovered after his ex-wife reported finding “some photos of prepubescent juveniles on his computer,” Garnero said. How exactly the case got lost within the software, though, remains unclear.

But Redding Police Chief Bill Schueller said that it was unclear whether Rovito’s initial case was lost due to a problem with Spillman — which he said the department had just started using a few weeks before the case was filed — or a mistake made by a staff member who was “learning the new system and making a mistake in the routing of the reports.” He said a lieutenant doing an audit of other lost cases has found “a couple hundred,” but “none of any significant impact” like the Rovito case.

Lieutenant Chris Smyrnos of the Redding Police, who said he oversaw the implementation of Spillman throughout Shasta County, said that Rovito’s 2018 case was likely lost due to an “operator error where that report got misrouted” to a part of the software that was not being actively monitored by those who had access to it — something he said the software should not allow to happen in the first place.

Because it was lost, the case was never prosecuted and didn’t reach the Shasta County District Attorney’s Office until last November, after officials initially believed the statute of limitations had expired, representatives for the DA’s office and the Redding Police Department have said.

It was only after Rovito’s current wife gave police his hard drive and a hidden camera she allegedly found in the couple’s bathroom that authorities from the DA’s office determined that the 2018 case actually fell under a 10-year limit and that law enforcement would investigate it alongside the more recent case. Rovito was arrested last month on charges related to possession of child sex abuse images and surreptitious recording.

Regardless of how the case was lost, Schueller said it was “very frustrating” that Rovito’s earlier case was lost until a few months ago — and that it’s far from his only frustration with Spillman.

Rovito’s lawyer, Timothy Prentiss, has said his client maintains his innocence. His next court date is April 21.

System crashes during 911 calls create ‘huge safety risks'

Spillman has a track record of failing to properly maintain multiple types of records for the Redding police, including crime data, Schueller alleged. As a result, the crime statistics available on their website from 2019 to 2021 are “a rough estimate,” he said.

“We didn’t do it for 2022 because it’s too screwed up,” he added.

The software has also failed to track how long it takes individual agencies to respond to the scene of an emergency, according to Schueller and Smyrnos, who said they can only see how long it takes the first agency to arrive. (If that first agency is the fire department, for example, the police department can’t see how long it took their officers to arrive, Smyrnos said.)

As a result, Schueller has hired three high school interns to try to make those calculations manually so he “can get accurate response time data” for his officers, he said.

The software would also crash when officers were in the middle of writing police reports, Smyrnos said, adding that sometimes officers would lose narratives they had been writing for two to three hours, forcing them to start again.

And Schueller alleged Spillman has created “huge safety risks” for both first responders and civilians by repeatedly crashing while dispatchers were trying to enter details from 911 calls, which are needed to send first responders to the scene.

When the system crashes, call takers “handwrite notes on a piece of paper while the system reboots and continue to try to help the caller and get the units — whatever they are, fire, police or ambulance resources — to that person,” he said.

“A crash while you’re entering in an emergency call is not an effective way to serve our community,” he added.

Schueller said that officers in his department constantly reported problems with the software to the company — and “some things would get fixed, some things would never get fixed,” he said.

The software also repeatedly crashed during 911 calls in Weld County, Colorado, where more than 40 agencies used Spillman from approximately early 2012 until last November, according to one former and one current county official.

The system would freeze in the midst of 911 calls “like somebody unplugged it,” and call takers would then have to take handwritten notes and deliver them to a dispatcher charged with sending first responders to the scene, said Mike Wallace, the county’s former director of public safety communications.

“It was such a regular event with Spillman — the system was crashing on a weekly basis — that we had to educate and train our staff to manually intervene,” said Wallace, who is now the public safety communications manager for the city of Margate, Florida, which he said does not use the Spillman software.

A $1.25 million dollar settlement

Wallace said that while he could not recall any instance in which a civilian in Weld County died as a result of Spillman’s delays, officials knew the crashes were costing dispatchers and first responders time they couldn’t afford to lose.

“Between life and death, seconds mean everything,” he said.

Lost time due to a software error made a fatal difference in San Angelo, Texas, according to a more than $3.5 million lawsuit the city brought against Spillman Technologies in 2017.

The suit — which Spillman paid $1.25 million to settle that same year, and which was dismissed with prejudice, meaning it cannot be refiled — alleged Spillman was “a defective software solution” that “jeopardized the lives of the city’s residents and first responders.” It alleged that Spillman routinely crashed and failed to properly map the shortest routes to the scene of an emergency, causing first responders to rely on maps on their personal cellphones and forcing city residents to sometimes wait up to 30 minutes for first responders to arrive.

In one instance, a local resident who was suffering from cardiac arrest died, allegedly while waiting for first responders to arrive after the Spillman software allegedly malfunctioned and dispatched a unit of first responders located on the opposite side of the city, 25 to 30 minutes from the scene, according to the lawsuit. A closer group of first responders eventually learned about the emergency call and beat the other unit to the scene — but by that time, it was already too late, according to the lawsuit, which said the death was “a preventable outcome for the patient.”

In another incident, Spillman allegedly failed to alert dispatchers that multiple calls were coming from the same address: one caller — an armed man — said he planned to kill police and that neighboring homes should be evacuated, and another caller reported a house fire at the scene, the lawsuit states. As a result, police who arrived at the scene “were surprised to find the house on fire,” and firefighters were not prepared to encounter the man armed with a rifle in the home’s front yard, the lawsuit alleges, adding that firefighters “crawled to the back of their engine to take cover.”

Lorelei Day, deputy communications director for the city of San Angelo, said officials do not have any further comment on the settlement and that the city is now using software manufactured by a different company.

Former Spillman customers go elsewhere

Other onetime Spillman customers have also abandoned the software for what they say are more effective alternatives.

Weld County replaced Spillman last year with CentralSquare, a software system the company says is used by more than 8,000 public agencies, “due to the growth of our county and the increased functionality associated with CentralSquare,” said Tina Powell, director of public safety communications.

Shasta County will no longer be a Spillman customer as of May 1, when they will switch to Motorola’s PremierOne dispatch and records management software, which Schueller characterized as “tried and true” in large law enforcement agencies throughout the country.

“It’s been a frustrating transition to Spillman — I’m frankly glad we’re getting out of it,” he said.

READ MORE  Brandon Johnson campaigned on promises to make Chicago a leader in sustainability. (photo: Alex Wroblewski/Getty)

Brandon Johnson campaigned on promises to make Chicago a leader in sustainability. (photo: Alex Wroblewski/Getty)

Brandon Johnson campaigned on promises to make Chicago a leader in sustainability.

Johnson, 47, a former teacher and union organizer, currently serves as a Cook County commissioner. His campaign promises included making Chicago a leader in sustainability and addressing pollution-burdened neighborhoods in the city.

His opponent in the run-off election, Paul Vallas, 69, is the former CEO of Chicago Public Schools and ran on a tough-on-crime platform.

While environmental activists are cheered by his mayoral win, they and other observers also know the reality.

“He’s basically supportive of the environment, particularly equity … but he wasn’t elected on the environment,” said Dick Simpson, a professor emeritus of political science at the University of Illinois-Chicago and a former alderman.

So progress might depend on one thing: pressure.

“I think it’s important to put pressure on the new administration, by climate activists,” said Simpson. “Without vocal, continual pressure by both citizens and aldermen in the city council, it will remain a quite secondary issue.”

Communities in Chicago have risen up in recent years to fight back against environmental injustice, with the most recent struggle garnering national attention when residents of the Southeast Side protested against the proposed location of a scrapyard in their already polluted neighborhood.

Activists were eventually successful at preventing the move but only after years of actions that included hunger strikes.

One of those hunger strikers was Óscar Sanchez, an organizer at the Southeast Environmental Taskforce.

“We should be thinking of Brandon as a friend,” he said. “But we also hold our friends accountable.”

So activists will be watching to see if Johnson hews to his campaign promises, notably his claim that he would bring back Chicago’s Department of Environment, which was eliminated in 2011 by a previous administration. The current mayor, Lori Lightfoot, also promised to bring back the Department of Environment but failed to deliver.

Without that department in place, polluters in Chicago have largely gone unpunished according to a report by Neighbors for Environmental Justice. The local group reviewed data from 20 years and found that after the Department of Environment was shuttered, environmental violations fell by 50 percent and air quality citations fell by 90 percent.

In the meantime, Chicago’s air quality has declined. A recent Guardian analysis of air quality data found that Chicago’s South and West sides rank third in the nation for worst air quality in the United States.

For Sanchez, these issues of pollution and environmental justice are deeply connected to other issues in the city.

“Environmental justice encompasses housing, it encompasses our energy burden, it encompasses our availability to have clean water in our home, it encompasses being able to send our children to school without worrying about diesel trucks,” he said.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.