Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

“The Students Demand Action (SDA) has coordinated a nationwide school walkout amongst students throughout the country with similar trends to those seen in Colorado,” stated the situational awareness bulletin dated April 4, which was issued by the Colorado Information Analysis Center. CIAC’s mission is “preventing acts of terrorism, taking an all-crimes/all-threats approach,” according to the agency’s website. It’s not clear how the student walkouts relate to this mission. Experts have long criticized fusion centers like CIAC for operating with broad authorities and little oversight.

“Sadly, messaging targeting protests happens all too often from fusion centers thanks to expansive mandates and lax rules and accountability,” said Spencer Reynolds, counsel in the Brennan Center for Justice’s liberty and national security program, who previously served as senior intelligence counsel in the office of general counsel for the Department of Homeland Security. “These agencies started as counterterrorism hubs and in early years often singled out American Muslims,” Reynolds added. “They’ve since doubled down, expanding to scrutinize racial justice, environmental, and pro-choice demonstrators.”

“The Colorado Information Analysis Center is not monitoring,” a spokesperson for the Colorado Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management told The Intercept. “The staff within the state’s watch center provide situation awareness to our school districts for planning purposes. … As our website states, the watch center is a unit that has analysts who provide 24/7 support to include coordinating information collection, analysis, and dissemination for Colorado Department Public Safety.”

Fusion centers like CIAC are state entities that were established in the wake of 9/11 to streamline domestic intelligence-gathering. They provide warnings and analysis to local law enforcement and work in concert with federal agencies like the Department of Homeland Security. They have drawn criticism from civil liberties advocates for engaging in sweeping data collection and dissolving the legal boundaries between state and federal power.

“Fusion centers are often run by police and have a practice of tracking protesters who they construe as security threats,” Reynolds said.

CIAC’s expansive focus is evident in several other bulletins obtained by The Intercept, which are not public but were shared with state and federal partners, including law enforcement. One bulletin, dated November 29, 2022, warned of “potential threats posed by extremism in gaming,” citing games like Roblox as examples. Another warned of the “social and safety implications of new social media app, Gas,” a social platform designed for high schoolers.

“The planned school walkouts are believed to be in response to several recent school shootings,” the CIAC bulletin states, going on to identify over two dozen Colorado schools where walkouts were expected to take place. Last month, two school administrators were shot and wounded by a 17-year-old in Denver’s East High School. On March 27, six people, including three students, were killed when a former student opened fire at the Covenant School in Nashville, Tennessee. The CIAC bulletin attributes the walkouts to both of these shootings.

READ MORE  Justin Jones on the floor of the House chamber as he walks to his desk to collect his belongings after being expelled from the legislature. (photo: AP)

Justin Jones on the floor of the House chamber as he walks to his desk to collect his belongings after being expelled from the legislature. (photo: AP)

ALSO SEE: Tennessee Dems Call Out 'Racial Dynamic' That Fueled Expulsion From House

The vote came a week after three lawmakers interrupted a floor session with a megaphone, leading protesters in calls for stronger gun laws in the wake of the Nashville school shooting that left six people dead.

They said they were representing their constituents, while Republicans said they were leading an insurrection.

The Republican-controlled House voted along party lines to expel Reps. Justin Jones, D-Nashville, and Justin Pearson, D-Memphis — both Black lawmakers under the age of 30. Rep. Gloria Johnson, D-Knoxville, held on to her seat by a single vote, and later suggested that's because she is white.

Jones agrees. Speaking to Morning Edition on Friday, he accused Tennessee House Speaker Cameron Sexton of having "trafficked in racial rhetoric and racism."

"This is the consequence of a body that wants to suppress not just our vote, but the votes of our districts that are majority Black and brown," Jones said. "I represent one of the most diverse districts in Tennessee, and so now those 78,000 people have been silenced."

Sexton has not responded to NPR's request for comment on Jones' claims. But he told reporters after the vote that the decision was based on "the actions of those three that they did on the House floor on that day," and the body needing to follow the proper "process and procedures."

Jones says the lawmakers decided to bring the protest to the House floor on March 30 out of frustration with the legislature's inaction on gun control and hope that they would listen to the young people who were rallying at the Capitol. They were the largest protests Nashville has seen in the past decade, he says.

Jones represents a part of the city and says the community is still grieving and processing the trauma of the Covenant School shooting in late March.

"People are calling for action, and the first action we get from the Tennessee general assembly is to expel members for calling for common-sense gun laws," Jones adds.

So what happens next? Jones' and Pearson's districts will hold special elections to fill their newly vacant seats, and their county commissions can appoint an interim lawmaker to serve until then.

When asked whether he will run in the special election, Jones says "we are looking at all options right now."

Member station WPLN reports that the Metropolitan Council — the legislative body of the consolidated city-county government of Nashville and Davidson County — will hold a special meeting on Monday, where they may vote to reappoint Jones.

Jones says many members of the council have said they will do so.

"Now the question is: Will Speaker Cameron Sexton allow us to be seated, or will he once again try and subvert the will of the voters?" Jones adds.

Sexton told reporters that if the council does reappoint the expelled lawmakers, "we'll go through that process when the time comes." According to Tennessee's constitution, lawmakers can't be expelled more than once for the same offense.

And if the council does reappoint Jones, will he return and demand his seat?

"Most definitely," he says.

Jones spoke to Morning Edition's Steve Inskeep about the events leading up to his expulsion and what he hopes to see now.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Interview highlights

On whether expulsion is a fitting consequence for civil disobedience

This is not the natural consequence, this is the most extreme reaction that we saw that sets a very dangerous precedent for democracy. ... This is only the third time in Tennessee history that the House of Representatives has expelled its members, and the other times involved criminal or unethical activity. ... We were expelled for "breach of decorum," but in reality we were expelled for obedience to our oath of office to speak for our constituents and to make sure that our dissent and protest is marked for the journal when we see action that is injurious to the people.

On why lawmakers led the protest in the first place

Thousands of people — students, parents, teachers, grandparents, concerned community members — [were] here at the Tennessee Capitol, and the speaker refused to let them be heard. He refused to even let us talk about the issue of gun violence on the House floor that week. Any time we brought it up our microphones were cut off, we were ruled out of order, so we did not have even a venue to voice the grievances of our community. And so we had no other choice but to do something out of the ordinary and to try to stand in solidarity with disrupting business as normal, because business as normal was sticking our head in the sand when our children are dying.

On what House leadership did and didn't do after the protest

The next day the speaker already stripped my committees from me, he had my ID badge to the building turned off even though I was still a representative at the time, shut off my parking privileges to park at the legislature, and so that was the reaction that we saw.

But then because the speaker falsely mischaracterized our nonviolent peaceful protest and solidarity with the people as an insurrection, he escalated the situation not only against us but against those thousands of young people at the Capitol who were protesting, simply saying that they want to live, in the days following a mass shooting here in Nashville.

On whether he thinks lawmakers' youth, race and political leanings factored into their expulsion

That's absolutely correct. We're the two youngest Black lawmakers. I'm 27, Rep. Pearson is 28, and so we represent the voices of our generation. And race, most definitely. And I think Rep. Johnson said it, when she was not expelled and I was expelled — those were the first two cases heard — the news media asked and she said "I think it's because of skin color."

READ MORE  Rebekah Jones clashed frequently with Governor Ron DeSantis after her dismissal on grounds of insubordination. (photo: Kaytie Boomer/AP)

Rebekah Jones clashed frequently with Governor Ron DeSantis after her dismissal on grounds of insubordination. (photo: Kaytie Boomer/AP)

Rebekah Jones says 13-year-old, charged over apparent threats to middle school in February, targeted for political reasons

The 13-year-old is the son of Rebekah Jones, the founder of Florida’s pandemic database, who clashed frequently with DeSantis after her dismissal on grounds of insubordination.

According to officials in Santa Rosa county, the boy made online threats in February to “shoot up” a middle school or stab people, resulting in a charge of internet-related terrorism.

But in a Twitter thread, Jones claimed her son Jackson was “kidnapped on the governor’s orders” as retaliation for her filing a lawsuit last month to try to win her job back, and had been cleared as “not a threat” by police and school officials.

“That’s what they do in Florida: steal your children as political punishment,” she wrote.

Jones said her son only reposted internet memes about mass shootings in a Snapchat group with friends, yet was arrested and detained in a juvenile facility because “he has a target on his back”.

The Miami Herald reported on Thursday that the youth was arrested on Wednesday.

Jones, a Democrat who lost her challenge for DeSantis ally Matt Gaetz’s congressional seat in November, tweeted that she suspected her son’s social media was being spied on.

“A week after we filed our lawsuit against the state, a kid claiming to be the cousin of one of my son’s classmates joined their Snapchat group. They recorded their conversations, and anonymously reported my son to police for sharing a popular internet meme,” she said.

“They said they had to complete a threat assessment since they received an anon complaint, which both the local cops and the school signed off on as not being a threat.”

Two weeks later, she said, the state issued a warrant for “digital threats of terrorism”.

“Everything my son has struggled with these last two years came from DeSantis personally targeting my family for blowing up his Covid success story lie. He was 11 years old when he was held up at gunpoint by police on DeSantis’s orders,” she added, referring to a December 2020 incident in which armed officers raided the family’s home as the Florida department of law enforcement (FDLE) investigated an alleged hacking of the health department’s computer network.

Jones later reached a plea deal in that case, admitting guilt and paying FDLE $20,000 for the cost of the investigation.

DeSantis’s office did not respond to a request for comment. But according to Santa Rosa sheriff’s spokesman Bob Johnson, speaking with Wear TV, the teenager “basically said something along the lines ‘I’m feeling silly today, I think I may shoot up a bunch of people in a building’.”

A police report seen by the TV station said a search warrant for his Snapchat account uncovered threats against his former middle school, including: “I want to shoot up the school,” and “I always keep a knife on me so maybe I’ll just stab ppl idk”.

The memes, the Herald reported, including one of a police officer sleeping instead of responding to a school shooting.

Jones, in her lawsuit, accuses the state of violating her whistleblower protections by firing her when she claimed Florida’s health department forced her to suppress the real number of Covid cases and deaths. She is seeking compensation for “emotional distress”, and reinstatement with back pay.

She called DeSantis, a likely candidate for the Republican party’s 2024 presidential nomination, “a fascist who wishes to be king”.

READ MORE  Oscar Leon Sanchez (left) was fatally shot by LAPD officers on Jan. 3, 2023. (photo: Courtesy Sanchez Family)

Oscar Leon Sanchez (left) was fatally shot by LAPD officers on Jan. 3, 2023. (photo: Courtesy Sanchez Family)

It’s yet another case that raises concerns about police response to mental health crises and puts the spotlight on the barriers to mental health care for L.A.’s immigrant community.

Just up the street, Ysidro Leon motioned to an altar he prepared for his deceased brother, Oscar Leon Sanchez, under their covered patio.

Fresh flowers sat atop a gold tablecloth and candles burned all around. In the center, a picture of Leon Sanchez leaned up against a larger print of Our Lady of Guadalupe. “My brother liked her a lot, he had shirts, he had caps of the Virgin of Guadalupe ... Well, we, like every Mexican, you understand, we always venerate people and our saints,” Leon said in Spanish.

Leon Sanchez’s photo was marked with the day he was killed by LAPD officers: Jan. 3, 2023.

Borders and barriers

The first week of January was a deadly one for interactions with LAPD. Within just 48 hours, Takar Smith, Keenan Anderson, and Leon Sanchez were added to the long list of people who have died at the hands of police officers. Two of the men — Smith and Leon Sanchez — appeared to be experiencing a mental health crisis when they were shot and killed.

While both cases raise concerns about police response to mental health crises, the death of Leon Sanchez, a 35-year-old immigrant from Mexico, laid bare the barriers that L.A.’s immigrant community faces in accessing mental health care. Among the obstacles: fear of deportation, a dearth of culturally competent therapists who speak their language, and a cultural stigma around mental diseases and seeking help.

Leon Sanchez arrived in Los Angeles in 2007, according to his family. A psychologist LAist spoke with said she often sees immigrant patients who experienced complex trauma in their home countries. And the stress of adapting to life in the U.S. can exacerbate those issues, especially with the increased anti-immigrant rhetoric in recent years.

As Carolina Valle, policy director for the California Pan-Ethnic Health Network, put it: “We’ve seen huge attacks on the immigrant population ... And that has had a huge effect on their feelings about accessing care, their feelings about government and their feelings about services.”

Fatal encounter

In an uncommon move, LAPD Chief Michel Moore released officer body-worn camera video from the incidents involving Smith, Anderson and Leon Sanchez at a press conference the week following their deaths.

In the case of Leon Sanchez, the LAPD said 911 callers alleged he was throwing metal objects at cars and people while holding a knife.

Officers found Leon Sanchez at an apparently abandoned home. In the beginning of the released body camera video, two officers are heard talking to him for several minutes in English and Spanish, asking him to come down from a second-floor balcony.

The LAPD claimed Leon Sanchez advanced toward them with a sharp metal object at which point officers fired live and non-lethal ammunition. In the body camera video, one of the officers is using a riot shield that blocks the view of Leon Sanchez, which makes it impossible to see these alleged actions.

According to the L.A. County coroner’s office, Leon Sanchez’s cause of death was “multiple gunshot wounds.” The full autopsy report was not available as of March 22, due to “pending additional testing,” a coroner’s office spokesperson said in an email.

Leon said his brother was struggling with depression after the death of his mother in 2019. Christian Contreras, the family’s attorney, said Leon Sanchez was diagnosed with major depressive disorder after the death of his mother in 2019 and had taken medication to treat his condition.

Jonathan Smith is executive director of the Washington Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights and Urban Affairs. He is a use-of-force expert who reviewed the footage at LAist’s request.

While Smith said he’s relatively impressed with the officers coordination and decision to have less lethal force ready, he questions why officers didn’t call in one of the LAPD’s specially trained mental health crisis teams made up of an armed officer and a clinician from the Department of Mental Health, especially since a 911 call alleged Leon Sanchez was throwing things at cars and pacing back and forth. One caller said: “It appears that he’s on drugs because he’s assaulting people on the street.”

“The information I have raises very, very serious concerns about whether any force was authorized or useful,” Smith said.

READ MORE  A man lights a candle at a memorial during a ceremony Dec. 11, 2021, to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the massacre of nearly 1000 civilians in the village of El Mozote, El Salvador. (photo: Jose Cabezas/Reuters)

A man lights a candle at a memorial during a ceremony Dec. 11, 2021, to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the massacre of nearly 1000 civilians in the village of El Mozote, El Salvador. (photo: Jose Cabezas/Reuters)

More than 1,000 adults and children were killed there in 1981 by the military searching for an alleged training camp.

Roberto Antonio Garay Saravia, a retired officer from the Salvadoran Armed Forces, was arrested in New Jersey on Tuesday by Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Removal Operations officers with the assistance of Homeland Security Investigations agents.

He was arrested on charges of assisting or otherwise participating in extrajudicial killings and willfully misrepresenting this material fact in his immigration application, the Department of Homeland Security said in a news release.

“Individuals who have committed atrocities overseas will not find safe haven in the United States,” DHS Deputy Secretary John K. Tien stated in the press release.

The investigation was initiated and developed by Homeland Security Investigations' Human Rights Violators and War Crimes Center.

In late 1981, U.S.-trained Salvadoran army units attacked civilians in the town of El Mozote. At least 1,000 people, half of them children, were killed.

The Salvadoran army was fighting leftist guerrillas of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front.

When President Ronald Reagan took office earlier that year, he increased military aid and sent Special Forces instructors to the Central American country.

According to the press release, Garay Saravia was a section commander in a specialized counterinsurgency unit known as the Atlácatl Battalion from 1981 to 1985. It goes on to say the unit was directly implicated in numerous atrocities, including the El Mozote massacre.

Garay Saravia was also deployed in three other operations that resulted in the massacres of hundreds of noncombatant civilians.

READ MORE  Plaintiffs pose at the Miami Dade County Courthouse on the day their climate lawsuit was filed in April 2018. (photo: Robin Loznak/Our Children's Trust)

Plaintiffs pose at the Miami Dade County Courthouse on the day their climate lawsuit was filed in April 2018. (photo: Robin Loznak/Our Children's Trust)

This summer, the first youth-led climate case will make it to trial. And it could change everything

Close to five years ago in this exact place, she was brainstorming with her mother about a service project at the start of her freshman year in high school. Her mother showed her an article about China ceasing to take the world’s plastic recycling and suggested her daughter choose something environmental for the assignment. That moment was Gibson-Snyder’s first awakening to a planet in peril.

She suddenly began noticing that thick wildfire smoke choked the skies more frequently in summer, forcing her soccer practice indoors. She went for a hike in Glacier National Park, dipped in a lake at the bottom of a glacier that had existed for thousands of years and was predicted to disappear by the end of this century. By the time a teacher mentioned that the best way to reduce an individual carbon footprint was to forgo having children, she’d already started wondering on her own whether she should have the kids she’d always wanted. How much would her children suffer, and contribute to global suffering? How could this huge decision with such considerations be her burden at only 14 years old? And how was it that none of the adults in the proverbial room were doing anything about this?

At 14, she watched Greta Thunberg’s speech to the U.N. Climate Action Summit, the one where Thunberg said to gathered authorities of the world: how dare you have known for so long that the climate was changing and done so little. How dare you come to the youth for your hope. How dare you steal our childhood and our future like this while you continue to look away. How dare you.

“I remember collapsing, bawling,” Gibson-Snyder says. “She pointed at what I had been feeling. She was able to capture the rage and terror and unfairness of this all in one phrase.”

When Gibson-Snyder was 16, a guest speaker came into the weekly lunch meeting of her school environment club. The speaker talked about a youth climate case that was being put together against the state of Montana for violating its citizens’ Constitutional right to a clean and healthy environment by doubling down on fossil fuels. By then, Gibson-Snyder had begun to understand that agonizing over individual changes like avoiding plastic straws wasn’t the most efficient way to solve the climate problem. “Relying on individuals to change everything about their lives is a misplaced responsibility,” she says, “when it’s governments and corporations — governments enabling corporations — that caused this situation in the first place.”

Gibson-Snyder signed onto the lawsuit as a plaintiff. It felt, finally, like agency. She joined 15 others, ranging in age from 2 years old to 18 and hailing from all over Montana: the doorsteps of Glacier and Yellowstone National Parks, the Flathead Indian Reservation, western cities like Kalispell and east to the rural Powder River. The youngest two plaintiffs suffer from respiratory conditions that leave them vulnerable to the poor air quality of wildfire smoke; their parents signed them onto the suit. Most heard about it through school, friends, or older siblings and signed on themselves.

Now, three years later, that case will finally be heard in June in Montana’s small capitol town of Helena. As the first youth-led climate case to make it to trial, it’s the first time that this generation and their prosecution can lay out a body of evidence for how climate change is impacting environmental resources, how a state’s fossil fuel-driven projects and existing policy violate a constitutional right and knowingly contribute to climate change, and the psychological injuries its children suffer as a result. A similar Utah case was recently dismissed, and a suit against the federal government has been languishing in delays since 2015; in 2020, a federal appeals court “reluctantly” threw it out, ruling that climate change was not an issue for the courts. But Montana is a unique battleground.

It all started in 1972, explains Anne Hedges, director of policy and legislative affairs for Montana Environmental Information Center and an expert witness for the youth. Montana citizens came together to write a new constitution to replace the 1889 governing document that had been written, essentially, to give industry free reign to pillage the landscape. The Constitutional Convention minutes brim with stark examples of disaster. The Anaconda Copper Company smelter stack—one of the tallest brick structures in the world and so wide you could drive a bus around its top—was turning surfaces in Anaconda black with toxic soot. The open pit mine in Butte was filling with deadly acid water. The aluminum plant in the Flathead was spewing fluoride gas that damaged trees and deformed the bones of wildlife. The pulp mill in Missoula, not far from where Grace and I sit now in the coffee shop, was polluting water.

The convention delegates, who actively de-emphasized their political affiliations, wanted to ensure the farming, ranching, and outdoor recreation that shaped Montana would be protected, along with its ecosystems and people. They wrote the strongest language possible, including a Constitutional right to a clean and healthful environment for present and future generations, a right provided in only two other states: Pennsylvania, and as of 2021, New York.

But then came the money. Tax revenue from two enormous coal-fired power plants built in southeast Montana in the 1980s went to programs that helped develop the state. And it went into private pockets, too, of coal companies and lobbyists and legislators. In the early 2000s, Montana environmental groups increasingly raised concerns about climate change in the review process to permit new energy projects; in response, fossil fuel interests convinced the state to simply prohibit those reviews from considering climate change impacts. The fossil fuel industry also convinced the legislature to add provisions specifically promoting fossil fuels to the state’s energy policy — even though state agency reports during those years pointed to fossil fuels contributing to Montana’s shift from a carbon sink to a carbon emitter. As a result, Hedges says, the state has never denied a permit sought by a fossil fuel company. Today Montana is one of the top five coal producers in the U.S. with extraction levels higher than that of entire countries, including Brazil, and total annual emissions from its fossil fuel-based economy are on the order of 166 tons of CO2.

To keep the youth case from going to trial, the state has engaged in a series of aggressive tactics, said lead counsel and Our Children’s Trust lawyer Nate Bellinger. They’ve filed legal motions and practices to attempt to get the case dismissed, including trying to secure a court order allowing them to do independent psychological evaluations for some of the plaintiffs and trying to depose the youngest ones, who are only 5 and 8. And now in the state legislature, Republicans enjoy a supermajority. Montana Republicans have submitted bills in this 2023 session to weaken the Constitutional right to a clean environment and to repeal the state’s energy policy—both statutes at the core of the youth climate trial, and both aimed at making the trial disappear, although it’s unlikely such measures will affect the underlying legal claims of the case.

The attorney general’s office declined to comment, as did the state’s agency and expert witnesses. But based on depositions, the state is likely to argue that the climate is changing less than the mainstream narrative claims, that it’s not caused by humans, and won’t have the dire impacts on Montana alleged by the prosecution; the state’s emissions aren’t significant to global emissions; the plaintiffs themselves are consuming fossil fuels; and that the youth’s psychological impacts are due to the fact that they’re victims of the “apocalyptic rhetoric” surrounding the “faux climate ‘crisis.’”

Melissa Hornbein, a Helena-based lawyer and one of three local counsel on the case, says that while she never wants to predict what a judge is going to do, she thinks the case is fairly straightforward at a legal level in favor of the plaintiffs, given the Constitutional right and the fact that the state knew it was contributing to climate change. And if they win, it’s a precedent-setting case that climate change is, in fact, a court issue. A ruling in favor of the youth could catalyze a domino effect of similar rulings across the country based on rights to life, liberty, and protection of the environment as part of the public trust, making it one of the most consequential lawsuits to the fate of the next American generations.

But Hornbien says there’s also another important issue at the heart of this battle.

“We’re at an inflection point in Montana, with respect to the values that are enshrined in our 1972 constitution, which was frankly one of the most progressive and visionary constitutions of any state in the country. And the time has come for us as Montanans to decide if those are still our values. We’re seeing this at the national level, too, that democracy is not self-sustaining, it’s a decision that has to be made on an almost daily basis. We have a truly unique guiding document in this state. But it’s not going to protect itself.”

NINETEEN NOW, Gibson-Snyder will have spent three years of her youth as part of this case by the time the trial rolls around. After graduating high school, she took a gap year to live in Washington D.C. and accompanied a State Department trip to Jordan, where she put to work the Arabic she learned in high school. She’s back home on break from her first year at Yale, where she aims to study environmental policy. Wearing a white collared shirt under a sweater and her hair in a low bun, poised and articulate, she resembles a young lawyer herself.

In the coffee shop, our conversation has been interrupted twice when the director of Families for a Livable Climate and then the director of Climate Smart Missoula, both of whom she worked with during high school, stop by to say hello. We’d talked about meeting in one of Gibson-Snyder’s favorite outdoor spots instead, perhaps up the canyon, but it’s currently pouring rain in a whiplash swing from the bomb cyclone that dumped snow and record lows on Montana—the kind of extreme swings that climate scientists predict will become more common. Looking out at the rain, Gibson-Snyder talks about what it’s like to grow up “at the wrong time, crunch time as far as the climate crisis goes,” and to live with “the burden placed on us from all sides to be the saviors, the ones who will make it all right again.”

“I’ll spend several weeks focusing on class and friends and then experience days of bone-crushing guilt, thinking what am I doing, why am I spending time on these things [instead of environmental work]. And that is such an invalidating experience. I’m so much more than that as an individual. I have to be [in order] to keep my sanity. I’m an adult now, but I shouldn’t be responsible for the world. It’s so ridiculous to expect these 7- and 12-year-olds to have to persuade the state to protect us so we can have a healthy life, when the entire point of the state is to protect our rights.”

In media around the case, state representatives have called the youth liberal tools being exploited by out-of-state-special interest groups and dismiss their climate-induced psychological burdens as emotional hysteria and irrational thoughts placed in their heads by their parents and hyped-up media. I ask her how it feels to hear those things from the entity that’s supposed to be protecting her.

“It really bothers me to have this pushback from the state when we’re fighting to protect the Attorney General’s children and grandchildren, their land and their home. And the blame—they’re such straw man arguments. It’s not Missoula running this case,” she said, referencing her hometown’s status as the state’s liberal island. “It’s people from all across the state. That’s what gives it such power.”

IN THE FLATHEAD VALLEY, plaintiffs Lander and Badge Busse grew up in an opposite environment from Gibson-Snyder’s community. Evangelical billboards spring from the side of the highway. Although Trumpist Ryan Zinke won Montana’s new Senate seat in 2022, he lost this district—his own home district—in the primary to an even more right-wing opponent. The first house on the Busses’s street in the wooded outskirts of Kalispell is enclosed in an extensive eight-foot fence holding up security cameras and a Q’Anon sign.

Sporting a seventies shag, Lander, 18, looks the part of a retro rock star. Which he may be someday, if he can get a scholarship to study music theory in New York, and when he finishes the post-apocalyptic concept album he’s been mulling. Badge, 15, looks the freestyle skier that he is in baggy jeans and a t-shirt. He’s at the mountain every weekend in winter, determined to ski all the real snow he can before, as his ski coach mentioned recently, manmade snow replaces it. In summer, he’d rather be fly fishing than doing anything else. And in the fall, both boys tote rifles into the forest with their father to bring home game to fill the freezer. Their living room is hung with the antlered skulls of the brothers’ first elk, first deer. Hunting, they explain, is not an extracurricular activity. It’s part of a way of life that’s deeply connected to the land and the health of that land.

Between the hook-and-bullet lifestyle that’s been categorized as generally Republican and their home-ground politics, it’s easy to assume that the Busse boys are conservative, and that the next generation sees climate change as a nonpartisan issue—a trap I find myself falling into in wanting, just as Gibson-Snyder said, to believe that this generation is somehow better than us, can transcend our bitter divides. But the boys describe themselves as left-leaning. In fact, they only speak about the case now to each other, their parents (Sara, a communications consultant, and Ryan, a former conservative and firearms executive who wrote Gunfight: My Battle Against the Industry that Radicalized America, are both left-leaning), and others involved in the lawsuit. Both boys have lost friends over their participation in it, and struggle with how to ride the line between being kids and also part of such a weighty effort. “It’s like living two separate lives,” Lander says.

In 2011, Our Children’s Trust brought another youth climate case against Montana, petitioning the state Supreme Court to declare that the state holds the atmosphere in public trust and must therefore steward it for future generations. When Ryan and Sara heard about it, they described it to their boys, who wanted to sign on. Badge was only 4 at the time, and likely went along with Lander, Ryan said, who even then had a strong sense of justice. That petition was denied on a lack of legal grounds. When this new case came around, “we did not have to talk to either boy,” Ryan recalled. “They did the talking. Both were very keen on being involved and both were very versed on the issues and the case.”

Despite the isolation and threat of persecution, neither brother has questioned their commitment to the case. They’re proud to be part of it. Not winning, Lander says, “would be a complete obliteration of the values we stand for in Montana, and conservation values on a national scale. The people who wrote our Constitution knew the value of the land that we live on, and it’s our job as citizens to uphold those traditions that were written into it. It’s our obligation to be involved in this case, regardless of whatever harm it brings us, emotional or physical.”

Yes, physical. Armed intimidation, they say, is common in the valley. Badge references a 2020 Black Lives Matter rally in Kalispell when a counter-protester pointed an AK-47 at him. He turns to his brother now and says, as if he’s thinking of it for the first time, “I mean, I’m scared of showing up to court [in Helena] and there could be protesters outside.”

Neither of them are particularly worried about being on the stand, though. All the plaintiffs will be at the trial, although the little ones won’t testify. They’ve already been deposed—when the opposing side’s lawyers may ask questions as part of the discovery process before trial. In trying, Badge suspects, to get him to reveal that he actually didn’t spend all that much time outdoors, an attorney asked him several times where exactly his family hunted. He finally replied, “A local never gives up their spots.” They both say that the attorneys tried to corner them on energy questions, like what their house runs on, as if they’re supposed to come up with the solutions for how the state reduces fossil fuel extraction and demand. “That’s the state’s job,” Lander says. “Our job is to hold the state accountable to put in the necessary environmental protections that our Constitution guarantees us.”

I ask the boys what story they want to tell the world with their involvement in this case. Badge talks about rivers depleting, the glaciers that feed them melting until they’re gone, the fish disappearing with them. He describes the aching pain always in the back of his mind that he must savor every moment that his own kids may never experience.

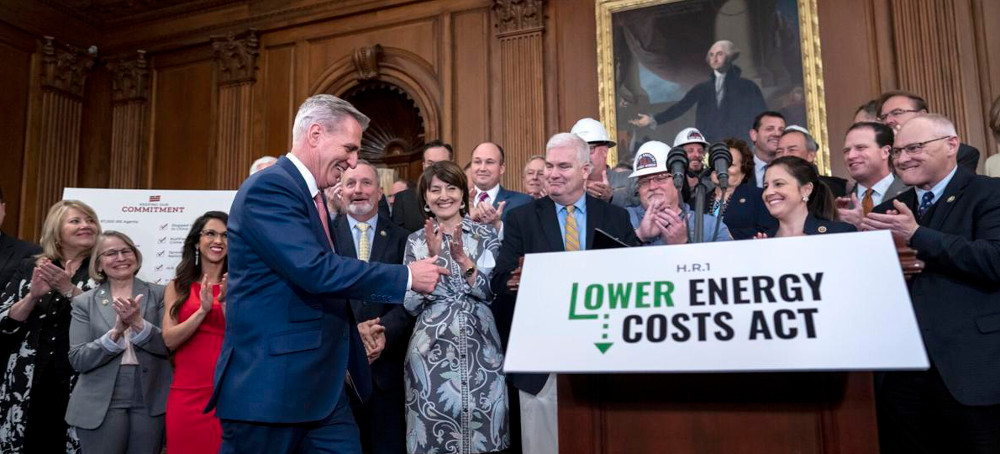

READ MORE  Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy is greeted by fellow Republicans after passing H.R.1 at the Capitol in Washington, Thursday, March 30, 2023. (photo: J. Scott Applewhite/AP)

Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy is greeted by fellow Republicans after passing H.R.1 at the Capitol in Washington, Thursday, March 30, 2023. (photo: J. Scott Applewhite/AP)

The so-called Lower Energy Costs Act, or H.R.1, would cut a fee on methane emissions from oil and gas operations, ease permitting regulations for energy projects and require more fossil fuel leasing on public lands, among other things. Its mostly Republican backers argue that it would boost U.S. energy independence and lower domestic energy costs, but opponents argue that relying on fossil fuels in the first place is what makes energy prices so volatile.

“None of it [the GOP energy agenda] makes sense in this moment,” Rep. Kathy Castor (D-Fla.), who sits on the Energy and Commerce Committee, told Politico. “They ignore the fact it was the high fossil fuel prices that was the primary driver of inflation. What I hear from folks back home is they don’t want to be at the mercy of these gas and oil price spikes. They are looking towards the clean energy economy — greater independence and more money in their pocket.”

The bill passed 225 to 204, with four Democrats supporting it and one Republican voting against. It is partly the GOP’s answer to President Joe Biden’s signature climate legislation, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). It would repeal key elements such as the methane fee, the $27 billion Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund and money to make buildings more energy efficient, according to Politico and The New York Times.

It also takes up the cause of permitting reform, limiting the review time for new projects under the National Environmental Policy Act to two years and making it harder for green groups to sue to block projects like pipelines.

Its backers argue that the measure would lower energy costs and ensure the U.S. does not have to rely on foreign powers.

“The Biden administration has kneecapped American energy production, and endlessly delayed critical infrastructure projects. Democrats’ misguided policies increased costs for every American and jeopardized our national security – and they’ve made the rest of the world more reliant on dirtier energy from Russia and China,” the website of House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) reads. “To lower costs for Americans and grow our economy, we need to get the federal government out of the way. The Lower Energy Costs Act will fast-track American energy production, and includes comprehensive permitting reforms that will speed construction for everything from pipelines to transmission to water infrastructure. And it ensures that the critical minerals needed for advanced technologies come from America – not China.”

However, it would actually cost taxpayers more, since it would reduce the royalties that oil and gas companies have to pay for drilling on public lands, The New York Times pointed out.

Environmental justice advocates, meanwhile, warn against the impacts of rushing through dirty energy projects.

“Developers and others attempting to cut corners on environmental impact assessments have a long history of placing environmentally harmful developments in communities of color, minimizing or even failing to disclose dangers to the communities,” WE ACT for Environmental Justice senior director of strategy and federal policy Dana Johnson said in a statement emailed to EcoWatch. “For the past half-century, NEPA’s standards for environmental impact assessments have helped communities identify and mitigate impacts and, most importantly, consider public comments. Any efforts to water down NEPA will subsequently hurt the communities impacted most.”

Democrats have dubbed the bill the Polluters Over People Act and will likely succeed in blocking it for now, The New York Times reported. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) said it was “dead on arrival,” and Biden has promised to veto it.

“This Administration is making unprecedented progress in protecting America’s energy security and reducing energy costs for Americans – in their homes and at the pump. H.R. 1 would do just the opposite, replacing pro-consumer policies with a thinly veiled license to pollute. It would raise costs for American families by repealing household energy rebates and rolling back historic investments to increase access to cost-lowering clean energy technologies. Instead of protecting American consumers, it would pad oil and gas company profits – already at record levels – and undercut our public health and environment,” a Statement of Administration Policy released Monday reads. “The Administration strongly opposes this bill.”

However, the bill is a victory of sorts for McCarthy, showing he can rally his party’s narrow majority for a vote, according to Reuters. It also could become a major campaign talking point for Republicans heading into the 2024 election, Politico noted. Finally, it could be a bargaining chip in the Congressional push for permitting reform, which is a major priority for coal-backed Senator Joe Manchin (D-W. Va.) and supported by some Democrats to ease renewable energy installations.

“By showing our strong support, we give some of our Senate Democratic friends an idea of okay, we have a place to work the permitting space particularly,” Representative Kelly Armstrong (R-N.D.) of the House Energy and Commerce Committee told Politico. “Even if it’s not the whole package, these are smart policies whether you are trying to hook up offshore wind or trying to get a gas pipeline from North Dakota to Illinois.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.