Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

"Gentlemen, we have interfered, are interfering and will interfere. Carefully, precisely, surgically and in our own way, as we know how to do," Prigozhin boasted in remarks posted on social media.

The statement, from the press service of his catering company that earned him the nickname "Putin's chef," came on the eve of the U.S. midterm elections.

It was the second major admission in recent months by the 61-year-old businessman, who has ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin. Prigozhin has previously sought to keep his activities under the radar and now appears increasingly interested in gaining political clout — although his goal in doing so was not immediately clear.

White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said Monday that Prigozhin's comments "do not tell us anything new or surprising."

"It's well known and well documented in the public domain that entities associated with Yevgeny Prigozhin have sought to influence elections around the world, including the United States. The U.S. has worked to expose and counter Russia's malign influence efforts as we discover them," she said, noting that Yevgeny has been sanctioned by the United States, the U.K. and the European Union.

"Part of Russia's efforts includes promoting narratives aimed at undermining democracy and sowing division and discord. It's not surprising that Russia would be highlighting their attempted efforts and fabricating a story about their successes on the eve of an election," she added.

In September, Prigozhin also publicly stated that he was behind the Wagner Group mercenary force — something he also had previously denied — and talked openly about its involvement in Russia's 8-month-old war in Ukraine. The military contractor also has sent its forces to places like Syria and sub-Saharan Africa.

Video also has emerged recently of a man resembling Prigozhin visiting Russian penal colonies to recruit prisoners to fight in Ukraine.

In 2018, Prigozhin and a dozen other Russian nationals and three Russian companies were charged in the U.S. with operating a covert social media campaign aimed at fomenting discord and dividing American public opinion ahead of the 2016 presidential election won by Republican Donald Trump. They were indicted as part of special counsel Robert Mueller's investigation into Russian election interference.

The Justice Department in 2020 moved to dismiss charges against two of the indicted firms, Concord Management and Consulting LLC and Concord Catering, saying they had concluded that a trial against a corporate defendant with no presence in the U.S. and no prospect of meaningful punishment even if convicted would likely expose sensitive law enforcement tools and techniques.

In July, the State Department offered a reward of up to $10 million for information about Russian interference in U.S. elections, including on Prigozhin and the Internet Research Agency, the troll farm in St. Petersburg that his companies were accused of funding. Prigozhin also has been sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury Department for election interference.

Until now, Prigozhin had denied Russian involvement in election interference.

Russian media, prisoner's rights groups and relatives of prisoners this year reported an extensive effort by Wagner — and sometimes Prigozhin personally — to recruit convicts to fight in Ukraine. Prigozhin hasn't directly confirmed it, but said in one statement that "either (the Wagner private military company) and convicts, or your children" will be fighting on the front lines.

Last week, Wagner opened a business center in St. Petersburg, which Prigozhin has described as a platform for "increasing the defense capabilities" of Russia.

On Sunday, he also announced through Concord the creation of training centers for militias in Russia's Belgorod and Kursk regions that border Ukraine.

"A local resident, like no one else, knows his territories, is able to fight against sabotage and reconnaissance groups and take the first blow if necessary," he said.

A one-time hot dog stand owner, Prigozhin opened a swanky restaurant in St. Petersburg that drew interest from Putin. During his first term in office, Putin took then-French President Jacques Chirac to dine at one of Prigozhin's restaurants.

"Vladimir Putin saw how I built a business out of a kiosk, he saw that I don't mind serving to the esteemed guests because they were my guests," Prigozhin recalled in an interview published in 2011.

His businesses expanded significantly. In 2010, Putin attended the opening of Prigozhin's factory making school lunches that was built on generous loans by a state bank. In Moscow alone, his company Concord won millions of dollars in contracts to provide meals at public schools. Prigozhin has also organized catering for Kremlin events for several years and has provided catering and utility services to the Russian military.

When fighting broke out in eastern Ukraine between Russian-backed separatists and Kyiv's forces in 2014, Prigozhin said through his spokespeople that he was seeking to "put together a group (of fighters) that would go (there) and defend the Russians."

Russian laws prohibit the operation of private military contractors, but state media in recent months have openly reported on Wagner's involvement in Ukraine.

READ MORE  A rally advocating for early voting and voting rights on Oct. 30, in Decatur, Georgia. (photo: Elijah Nouvelage/The Washington Post)

A rally advocating for early voting and voting rights on Oct. 30, in Decatur, Georgia. (photo: Elijah Nouvelage/The Washington Post)

Officials in Cobb County, a fast-growing suburb of metropolitan Atlanta, said on Friday that they failed to mail more than 1,000 requested absentee ballots because the election worker in charge of the machine used to package and mail absentee ballots improperly used a flash drive that records which requested ballots have been sent to voters.

Since the error was discovered, many of those voters have received an absentee ballot or have opted to vote by another method, according to county officials. The rest will have a ballot overnighted to them.

The American Civil Liberties Union and Southern Poverty Law Center filed a lawsuit on behalf of Cobb residents over the weekend. As part of a settlement reached Monday, the county said it will accept any ballots from affected voters by Nov. 14 as long as they are mailed by Election Day.

Cobb County Superior Court Judge Kellie S. Hill signed a consent order on Monday evening after deliberating with the county and civil rights organizations.

The Georgia secretary of state’s office said it has opened an investigation into the incident, calling the failure to mail more than 1,000 ballots “unacceptable.”

Janine Eveler, Cobb County’s election director, apologized for the error during a Monday afternoon news conference.

“We’re so sorry to these voters,” Eveler said. “We’re sick about it, the employee who is responsible is sick about it. She’s in tears all the time. We’re very upset, this has never happened to us, and we just want to make it right.”

Daniel White, an attorney for the county, added: “We want voters to be able to choose how they want to vote. We wanted to make it as convenient as possible. This was just a purely clerical error that an engineer is sick about, and the staff sick about it.”

Eveler said the county has faced high turnover in its election office, and 38 percent of election workers are new to their roles this year. The county lost several employees because they were under “too much pressure, and their own lives were suffering with the extra workload,” Eveler said. Ahead of the election, she said many staffers are working more than 80 hours a week.

“Though that is no excuse for such a critical error,” Eveler said.

Lawyers for the ACLU said they will work to ensure the order is fully implemented but cautioned that the specific incident didn’t account for the full scope of issues with absentee ballots in Georgia this year.

“We are happy that today’s ruling grants a specific subset of those voters a chance to cast their ballot. However, we heard from many voters who are not included in the solution provided today. We hope those voters can somehow exercise their right to vote as well, whether by mail or in person,” said Vasu Abhiraman, senior policy counsel for the ACLU.

A new election law approved last year also shortened the window of time during which voters could request an absentee ballot and the county could deliver it, which Eveler said made it “more difficult to get the number of ballots out in the short time that we have.”

READ MORE  Leola Scott at her home in Dyersburg, Tennessee. (photo: Ariel Cobbert/ProPublica)

Leola Scott at her home in Dyersburg, Tennessee. (photo: Ariel Cobbert/ProPublica)

While many states have made it easier for people convicted of felonies to vote, Tennessee has gone in the other direction.

In August, Scott tried to register to vote. That’s when she learned she’s not allowed to cast a ballot because she was convicted of nonviolent felonies nearly 20 years ago.

One in five Black Tennesseans are like Scott: barred from voting because of a prior felony conviction. Indeed, Tennessee appears to disenfranchise a far higher proportion of its Black residents — 21% — than any other state.

The figure comes from a new analysis by the nonprofit advocacy group The Sentencing Project, which found that Mississippi ranks a distant second, just under 16% of its Black voting-eligible population. Tennessee also has the highest rate of disenfranchisement among its Latino community — just over 8%.

While states around the country have moved toward giving people convicted of felonies a chance to vote again, Tennessee has gone in the other direction. Over the past two decades, the state has made it more difficult for residents to get their right to vote back. In particular, lawmakers have added requirements that residents first pay any court costs and restitution and that they be current on child support.

Tennessee is now the only state in the country that requires those convicted of felonies be up to date on child support payments before they can vote again.

The state makes little data available about who has lost the right to vote and why. Residents who may qualify to vote again first have to navigate a confusing, opaque bureaucracy.

Scott says she paid off her court costs years ago. But when she brought a voting rights restoration form to the county clerk to affirm that she had paid, the clerk told her she still had an outstanding balance of $2,390.

“It was like the air was knocked out of me,” she said. “I did everything that I was supposed to do. When I got in trouble, I owned it. I paid my debt to society. I took pride in paying off all that.”

Scott does not have receipts to verify her payments because she made them so long ago, she said. And there is no pathway for her to fight what she believes is a clerical error.

She is now a plaintiff in a lawsuit filed by the Tennessee NAACP challenging the state’s voting rights restoration process. In court documents, the state denied allegations that the restoration process is inaccessible.

Overall, according to The Sentencing Project, about 470,000 residents of Tennessee are barred from voting. Roughly 80% have already completed their sentence but are disenfranchised because they have a permanently disqualifying conviction — such as murder or rape — or because they owe court costs or child support or have gotten lost in the system trying to get their vote back.

Over the past two years, about 2,000 Tennesseans have successfully appealed to have their voting rights restored.

Those convicted after 1981 must get a Certification of Restoration of Voting Rights form signed by a probation or parole officer or another incarcerating authority for each conviction. The form then goes to a court clerk, who certifies that the person owes no court costs. Then it is returned to the local election commission, which then sends it to the State Election Commission for final approval. (Rules on voting restoration were revised multiple times, so older convictions are subject to different rules.)

Republican Cameron Sexton, speaker of the Tennessee House of Representatives, said people convicted of felonies should have to pay court costs and child support before voting.

“If someone’s not paying or behind on their child support payment, that’s an issue,” he told ProPublica. “That’s an issue for that child, that’s an issue for that family, not having the things that they agreed to in court to help them for that child.”

When asked about Tennessee being the only state to require that child support payments be up to date before voting rights can be restored, Sexton said, “Maybe Tennessee is doing it correctly and the others are not.”

A 2019 report from the Tennessee Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights found that the requirements for repayment have been especially burdensome to women, the poor and communities of color. The report also noted that Tennessee has increasingly levied court charges “as a means for funding the State’s courts and criminal justice system.”

Georgia previously required payment of restitution and fines in order to restore voting rights. But in 2020, the office of Georgia’s secretary of state clarified that anyone who has completed their sentence may vote, even if they owe court costs or other debts that were not incurred as part of their sentence.

Disenfranchisement does not solely impact the lives of individual voters — it can have consequences for elections, too. This is particularly true for multiracial communities in Tennessee, according to Sekou Franklin, a political science professor at Middle Tennessee State University. He pointed to county-level races that have been decided by a few dozen votes.

“There are real votes that are lost that can shape elections,” Franklin said.

Black Tennesseans, even those who were not enslaved, have been disenfranchised for centuries. In 1835, the new state constitution took away the right to vote from free Black men, who had been able to vote under the previous constitution. It also stipulated that anyone convicted of an “infamous” crime — a list that included robbery, bigamy and horse stealing — would lose their voting rights, often permanently.

The civil rights laws of the 1960s opened up voting again for Tennesseans. But soon lawmakers began adding back in provisions that disenfranchised people convicted of felonies. Legislators updated the statute every few years, adding to the list of crimes that permanently disqualify someone from voting. The result is a convoluted list of eligibility criteria for voting rights restoration that depend on what a person was convicted of and when the conviction took place.

The reality of disenfranchisement in Tennessee received some national attention recently around the case of a Memphis woman, Pamela Moses. Three years ago, she got her probation officer’s signoff to vote again. The next day, the Tennessee Department of Correction asserted the officer had made an error. Prosecutors then charged Moses with lying on an election document. She was convicted and sentenced to six years in prison, but a judge later threw out the conviction.

Tennessee lawmakers from both parties have tried, unsuccessfully, to make it easier for residents to get their vote back.

In 2019, two Republican lawmakers sponsored a bill that would have automatically restored voting rights to people upon completion of their sentence. It was supported by a bipartisan coalition of civil rights advocates, including the libertarian group Americans for Prosperity and the Tennessee American Civil Liberties Union. But it never gained traction among legislators.

In 2021, two Democrats sponsored another bill that would have granted automatic vote restoration, but that bill also died. The sponsors said that the Republican supermajority in Tennessee’s legislature simply doesn’t have an appetite to take it on.

“We said we wanted to do criminal justice reform, but all we’ve done is really nibbled around the edges,” state Sen. Brenda Gilmore told ProPublica, referring to a bill she co-sponsored with a fellow Democrat.

Dawn Harrington, the founder of Free Hearts, an organization that supports formerly incarcerated women, also advocated for the 2021 bill.

On a trip to New York City in 2008, Harrington carried a gun that was licensed in Tennessee. Because New York does not recognize permits from other states, she was convicted of a gun possession charge.

After serving a yearlong sentence on Rikers Island, she returned to Tennessee and set out to have her rights restored. Tennessee requires the incarcerating agency to sign the rights restoration form, but Harrington struggled to find someone in New York willing to sign it. After nine years, her rights were finally restored in 2020.

“I don’t know if you know the show ‘The Wiz,’ but I literally eased on down the road,” Harrington said about having her voting rights restored. “I danced. I was so happy I cried. I was feeling all the emotions. You never know how much something means to you until it’s taken away.”

READ MORE  People wait in line to vote early or resubmit ballots Monday at Philadelphia City Hall. (photo: Caroline Gutman/The Washington Post)

People wait in line to vote early or resubmit ballots Monday at Philadelphia City Hall. (photo: Caroline Gutman/The Washington Post)

The effort spawned a two-hour line at Philadelphia City Hall, as well as anger among voters who saw it as an attempt to infringe on their rights

Kirby Smith said after he and his wife were told that their ballots would not count, because they were missing dates, they stood in line for two hours at Philadelphia City Hall on Monday to cast new ones, missing much of the workday.

“Oh I’m going to vote. It’s not a question,” said Smith, a 59-year-old Democrat who said he viewed the court decision as part of an attempt to block people from voting. “I’m going to fight back.”

Multiple judges have ruled over the past two years that mail ballots returned on time by eligible Pennsylvania voters should be counted even if they lack a date on the outer envelope. Republicans sued in October to reverse that policy, arguing that it violated state law. Last Tuesday, they won a favorable ruling from the state Supreme Court, which directed counties not to count ballots with missing or inaccurate dates.

That decision triggered a sprawling volunteer-run effort to make sure voters who had already returned their ballots knew that their votes would not count if they didn’t take action.

Nowhere has that effort been more intense than in Philadelphia. On Saturday, city officials published the names of more than 2,000 voters who had returned defective ballots and urged them to come to City Hall to cast a new ballot in the few days remaining before Election Day. Community activists and volunteers for the Democratic Party and the Working Families Party began calling, texting and knocking on people’s doors to get the word out.

On Monday, the line to cast a replacement vote at City Hall snaked outside and into the building’s courtyard as volunteers supplied snacks and bottled water, according to voters and activists.

“I’m lucky. I could wait in line and do this,” said Melissa Sherwood, a 25-year-old Democrat who works from home. “Some people who don’t have that luxury probably took one look at the line and said no way.”

Penina Bernstein said she was thousands of miles away in Colorado when she found out — from friends and strangers who contacted her via Facebook — that her ballot was undated and would not count. She made immediate plans to get back to Pennsylvania to vote.

“I am flying home tonight and I will be there to fix it tomorrow, because my voice will not be silenced by voter suppression,” said Bernstein, 40, who added that she is not wealthy and was making the trip at significant expense.

Several volunteers said they had spoken to many other voters who said they would not be able to make it to City Hall to fix their ballots, because of a disability or a lack of transportation.

The mobilization to contact voters is a decentralized, ad hoc effort being carried out by many disparate groups. While some voters told The Washington Post that they had been contacted about their ballots multiple times, others said they had not heard anything until they received a call from a reporter.

“Our fear is there will probably be several thousand Philadelphians who lawfully attempted to vote and their votes will not count,” said Benjamin Abella, an emergency physician who has been volunteering with a group of fellow doctors working to notify voters that they need to fix their ballots.

Abella said that the effort by his group and others was a grass-roots mobilization to compensate for the lack of government effort to contact voters individually. He said voters who managed to get to City Hall found few workers ready to receive them — thus the long waits. “It’s really unfortunate that this is the way democracy works in America in 2022,” he said.

Shoshanna Israel, with the Working Families Party in Philadelphia, said the effort to help voters fix their ballots has snowballed since Sunday, with 250 people signed up for a phone-bank session Monday evening. The party has programmed voters’ names, type of ballot deficiency and county of residence into software that creates a tailored script for volunteers contacting voters.

Several voters told The Post that they had not received any notification from the city government. Nick Custodio, a deputy city commissioner, said Philadelphia officials put out a robocall to voters whose numbers they had. But otherwise, he said, “we’re focused on the election tomorrow.”

City officials had announced that voters could cast a replacement at City Hall until 5 p.m. Monday. But about 3:45, officials told some people in line that they would not reach the office before closing time and could not vote, according to Abella, who was there.

The decision upset some people, and sheriff’s deputies arrived to enforce the decision. City Commissioner Seth Bluestein, a Republican, wrote on Twitter that it was a “disgrace” that voters were being put in the position of trying to cure their ballots at the last minute. City officials are “doing the best they can to help as many voters as possible with very little time and resources,” he wrote.

Not all counties in Pennsylvania notify voters when their mail ballots are deficient and allow them to submit replacements. Courts have found that state law does not require counties to give voters a chance to fix defective ballots, but neither does it prevent them from doing so.

In Allegheny County, home to Pittsburgh, officials posted lists of more than 1,000 names of voters with undated or incorrectly dated ballots. Just over 100 cured their ballots on Monday, according to city officials.

Darrin Kelly, president of the Pittsburgh-area AFL-CIO-affiliate, said his members account for 147 of the voters whose ballots have been set aside there. His volunteer phone-bankers had contacted about 100 of them by 5 p.m. Monday and expected to reach all of them by the end of the evening.

“The most important thing is protecting our democracy and making sure everybody has a chance to vote,” said Kelly, who guessed that most of his members are Democrats.

At a public meeting of the Lancaster County elections board Monday, a citizen urged the board to notify voters who had cast defective ballots and allow them to cast another, saying to do otherwise would amount to disenfranchising neighbors. One of the board members said he agreed, but the other two did not.

“We’ve never cured ballots in Lancaster County,” said Joshua G. Parsons, a county commissioner and a member of the board. “It’s a questionable procedure.”

In northeastern Pennsylvania’s Monroe County, Republicans sued last week in an effort to block officials from inspecting mail ballots before Election Day, the first step of the county’s effort to ensure that voters who returned ballots with errors — such as missing signatures or dates — had a chance to cast a replacement. A state judge denied that request Monday.

Meanwhile, the fight over undated and incorrectly dated ballots is not over. When the state Supreme Court directed counties not to count those ballots, it also directed them to set those ballots aside and preserve them — apparently in anticipation of more litigation. On Friday, several voting and rights groups filed a lawsuit in federal court, arguing that not counting those ballots over a “meaningless technicality” would amount to a violation of civil rights law.

Clifford Levine, a Democratic election lawyer based in Pittsburgh, said he expects as many as 1 percent of mail ballots to be set aside for errors — a potentially difference-making sum in tight races such as the U.S. Senate contest. As of Monday, more than 1.1 million Pennsylvanians had cast ballots by mail, with about 70 percent of them Democrats.

The Pennsylvania secretary of state’s office has released the names of at least 7,000 voters whose ballots have been flagged for errors, but Levine said that number will grow through Election Day as more ballots arrive — and also because some counties have chosen not to review mail ballots, notify voters of errors or share the information with the state.

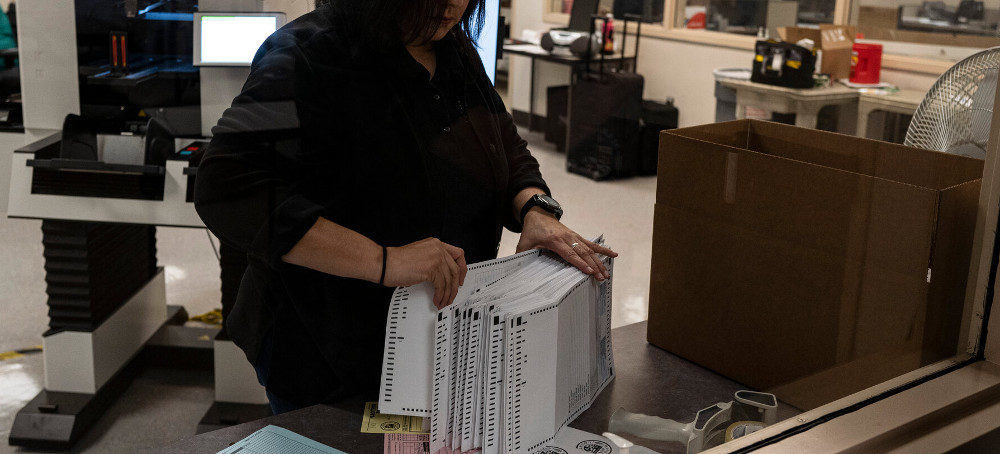

Eliza Luna, a ballot designer with the Maricopa County Elections Department, counts ballots for the Arizona Presidential Preference Election at the Maricopa County Tabulation and Election Center in Phoenix, Arizona, U.S., March 17, 2020. (photo: Adriana Zehbrauskas/The New York Times)

Eliza Luna, a ballot designer with the Maricopa County Elections Department, counts ballots for the Arizona Presidential Preference Election at the Maricopa County Tabulation and Election Center in Phoenix, Arizona, U.S., March 17, 2020. (photo: Adriana Zehbrauskas/The New York Times)

The harassment in Maricopa County included menacing emails and social media posts, threats to circulate personal information online and photographing employees arriving at work, according to nearly 1,600 pages of documents obtained by Reuters through a public records request for security records and correspondence related to threats and harassments against election workers.

Between July 11 and Aug. 22, the county election office documented at least 140 threats and other hostile communications, the records show. "You will all be executed," said one. "Wire around their limbs and tied & dragged by a car," wrote another.

The documents reveal the consequences of election conspiracy theories as voters nominated candidates in August to compete in the midterms. Many of the threats in Maricopa County, which helped propel President Joe Biden to victory over Trump in 2020, cited debunked claims around fake ballots, rigged voting machines and corrupt election officials.

Other jurisdictions nationwide have seen threats and harassment this year by the former president's supporters and prominent Republican figures who question the legitimacy of the 2020 election, according to interviews with Republican and Democratic election officials in 10 states.

The threats come at a time of growing concern over the risk of political violence, highlighted by the Oct. 28 attack on Democratic House Speaker Nancy Pelosi's husband by a man who embraced right-wing conspiracy theories.

In Maricopa, a county of 4.5 million people that includes Phoenix, the harassment unnerved some election workers, according to previously unreported incidents documented in the emails and interviews with county officials.

A number of temporary workers quit after being accosted outside the main ballot-counting center following the Aug. 2 primary, Stephen Richer, the county recorder who helps oversee Maricopa's elections, said in an interview. One temporary employee broke down in tears after a stranger photographed her, according to an email from Richer to county officials. The unidentified worker left work early and never returned.

She wasn't a political person, she told Richer. She just wanted a job.

On Aug. 3, strangers in tactical gear calling themselves "First Amendment Auditors" circled the elections department building, pointing cameras at employees and their vehicle license plates. The people vowed to continue the surveillance through the midterms, according to an Aug. 4 email from Scott Jarrett, Maricopa's elections director, to county officials.

"It feels very much like predatory behavior and that we are being stalked," wrote Jarrett.

ATTACKS PERSISTED

Since the 2020 election, Reuters has documented more than 1,000 intimidating messages to election officials across the country, including more than 120 that could warrant prosecution, according to legal experts.

Many officials said they had hoped the harassment would wane over time after the 2020 results were confirmed. But the attacks have persisted, fueled in many cases by right-wing media figures and groups that continue without evidence to cast election officials as complicit in a vast conspiracy by China, Democratic officials and voting equipment manufacturers to rob Trump of a second presidential term.

In April, local election officials in Arizona participated in a drill simulating violence at a polling site in which several people were killed, according to an April 26 email from Lisa Marra, the president of the Election Officials of Arizona, which represents election administrators from the state's 15 counties. The drill aimed to help officials prepare for Election Day violence, and left participants "understandably, disturbed" said the email to more than a dozen local election directors.

In a statement, Marra said: "This is just one other tool we can use to ensure election safety for all."

Maricopa officials appeared at times overwhelmed by threatening posts on social media and right-wing message boards calling for workers to be executed or hung. Some messages sought officials' home addresses, including one that promised "late night visits." Employees were filmed arriving and leaving work, according to emails among county officials.

Two days after the Aug. 2 primary election, the county's information security officer emailed the FBI pleading for help.

"I appreciate the limitations of what the FBI can do, but I just want to underline this," wrote Michael Moore, information security officer for the Maricopa County Recorder's Office. "Our staff is being intimidated and threatened," he added. "We're going to continue to find it more and more difficult to get the job done when no one wants to work for elections."

A special agent for the FBI acknowledged the agency's limitations, according to the emails. "As you put it, we are limited in what we can do - we only investigate violations of federal law," the FBI agent responded in an Aug. 4 email. Reporting threats to local law enforcement is "the only thing I can suggest," the agent wrote, "even if at this point it has not resulted in any action."

The FBI declined to comment on the agent's response to Moore. It also declined to confirm or deny the existence of ongoing investigations into the threats.

Moore did not respond to requests for comment, but Richer, his boss, said in a statement that he greatly appreciated the FBI's partnership and vigilance. "This is an inherently emotional topic - communications of the most vile nature have been repeatedly sent to my team," the statement said.

One anonymous sender using the privacy-protective email service ProtonMail sent "harassing emails" for almost a year, Moore, wrote in an Aug. 4 email to the FBI. One message warned Richer that he'd be "hung as a traitor."

"I'd like to have a black and white poster in my office of you hanging from the end of a rope," the sender wrote.

The harassment and threats were affecting the mental health of election workers, Jarrett wrote in his Aug. 4 memo. "If our permanent and temporary staff do not feel safe, we will not be able (to) recruit and retain staff for upcoming elections."

In all, county officials referred at least 100 messages and social media posts to FBI and state counter-terrorism officials. Reuters found no evidence in the correspondence that officials saw any of the messages as breaching the expansive definition of constitutionally protected free speech and crossing into the territory of a prosecutable threat.

The U.S. Justice Department declined to comment on specific ongoing investigations but said it has opened dozens of cases nationwide involving threats to election workers. Eight people face federal charges for threats, including two who targeted Maricopa County officials.

DOJ spokesperson Joshua Stueve said that while the "overwhelming majority" of complaints the agency receives "do not include a threat of unlawful violence," he said the messages are "often hostile, harassing, and abusive" towards election officials and their staff. "They deserve better," Stueve said.

ONLINE INSPIRATION

Misinformation on right-wing websites and social media fueled much of the hostility towards election staff, according to the internal messages among Maricopa officials.

On July 31, the Gateway Pundit, a pro-Trump website with a history of publishing false stories, reported that a Maricopa County election official allowed a staff technician to gain unauthorized access to a computer server room, where he deleted 2020 election data that was set to be audited. The website published the names and photos of the official and the tech; readers responded with threats against both.

"Until we start hanging these evil doers nothing will change," one reader wrote in the Gateway Pundit's comment section. Another suggested death for the computer tech identified in the story: "hang that crook from (the) closest tree so people can see what happens to traitors."

The tech hadn't deleted anything, according to a Maricopa spokesperson. The county election director had instructed him to shut down the server for delivery to the Arizona State Senate in response to a subpoena. A review of server records confirmed nothing was deleted, the spokesperson told Reuters, and all data from the 2020 election had been archived and preserved months earlier.

Election employees singled out in Gateway Pundit stories "tend to see a surge in being targeted" for threats and harassing messages, Moore, the county's information security officer, said in a Nov. 18, 2021, email to the FBI. Those stories, he added, are often "flagrantly inaccurate." A Reuters investigation published last December found the Gateway Pundit cited in more than 100 threatening and hostile communications directed at 25 election workers in the year after the 2020 election.

Other right-wing news outlets and commentators elicited similar hostile comments in response to their allegations against Maricopa officials. In August, right-wing provocateur Charlie Kirk posted a comment in Telegram accusing Richer, the county recorder, and "his cronies" of making Arizona's elections "a Third-World circus."

"When do we start hanging these people for treason?" one reader commented. Another simply added, "Kill them."

The Gateway Pundit and Kirk did not respond to requests for comment.

After a security assessment by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security in late 2021, Maricopa strengthened doors, added shatterproof film on windows and bought more first aid kits, according to the documents.

But the harassment has continued.

"This goes beyond just onsite security. It is a mental health issue," Jarrett, the county elections director, wrote in an email to county officials two days after the primary.

"I very much respect freedom of speech and welcome public scrutiny," Jarrett added. "However, allowing this predatory activity to occur is damaging and threatening the viability of the elections department."

READ MORE  Iranian women protest the mandatory hijab in Tehran metro. (photo: Twitter)

Iranian women protest the mandatory hijab in Tehran metro. (photo: Twitter)

3 million people use the Tehran Metro every day, and this mass of commuters is providing cover for daily acts of defiance against the regime.

Across the carriages and platforms of the Tehran Metro, small acts of resistance are everywhere, mirroring the widespread demonstrations that are taking place in the country’s streets, as people demand greater freedom and rights for women.

Here, protest slogans plaster subway walls, and anti-government chants ring out through the tunnels.

Some 3 million people in the mega-city’s population of 14 million take the metro every day, and with a smaller police presence, women feel more free to reject the country’s strict dress code around wearing headscarves.

For nearly two months, Iran has been roiled by protests against the country’s morality police and ruling clerics after the death of Mahsa Amini, who died in police custody on the 16th of September after being accused of dressing improperly. Since she died, tens of thousands of mostly young Iranians have taken to the streets across the country in response, calling for more rights and even revolution.

In the Tehran Metro, large crowds gather during rush hour, and chant popular political slogans such as, “Death to the tyrant, be it the shah or the mullah.” Clips of sporadic protests in metro stations are shared online more and more frequently, with more women refusing to wear headscarves inside train carriages.

Tehran’s metro is vast, with seven lines and 145 stations. The large number of people using the service during rush hour has provided people, particularly women, with a safe space to protest against the government.

The city’s traffic is notoriously terrible, but its metro line is among the most affordable public transport systems in the world – a day ticket costs just 4,500 Iranian Rials ($0.11). It’s become a key part of daily life for the city’s working class, students, and young people. Despite heavy surveillance and cameras set up inside the stations, crowds have for weeks been gathering on platforms and inside trains, often chanting anti-government slogans.

As anti-government demonstrations have developed, new protest trends have emerged, from knocking off clergymen’s turbans to young couples posting photographs of themselves kissing while riding the metro, and in other public places.

The network has been the setting for mostly peaceful protests in the past, most recently in 2021 as parts of the country grappled with a water crisis.

Public transport is gender segregated in Iran, with carriages divided with metal bars, creating sections for women, men and families. Women say this is yet another everyday reminder of how conservative Iran is.

“The carriages being divided between men and women is already a regular reminder of the reality of Iran, [which exists] no matter how much we try to build our own lives alongside all the rules and regulations,” said Parisi, who spoke using a pseudonym for security reasons.

#فوری

— BARANDAAZ_NEWS (@BARANDAAZOnline) October 31, 2022

هماکنون #تهران

شعار_نویسی همزمان با تظاهرات در مترو.

✊مرگ بر خامنهای

✊مرگ بر دیکتاتور #مهسا_امینی#اعتصابات_سراسری pic.twitter.com/eyQ04FZzhV

Women can be fined and jailed for breaking the “modesty” dress code, which includes wearing a dark headscarf in public, as well as a long jacket that falls at least to the knees, and a long list of “chastity rules.” Despite the law being harshly enforced for over four decades, women in Iran have found ways to circumvent the restrictive laws by wearing colourful fabrics and showing some of their hair – far from the ideals set by the clergymen who rule the country.

Iran’s feared morality police, known as Ershad, has tried to enforce hijab laws by patrolling the public transport system since July this summer, when the state was cracking down on dress-code violations. But with large crowds gathering inside the metro, many of the police officers just choose to just park their green-and-white vans outside the station entrances.

In July, Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi passed a series of laws and bills to crack down on a growing trend of young women failing to follow the so-called hijab laws, which he described as “un-Islamic.”

The ongoing protests highlight how young Iranians are increasingly refusing to follow these laws.

Amini was detained by a unit in a crowded public place during a family visit to Tehran. Her death triggered an outpouring of fury not seen since the protests against the strictly Islamic government instated after the revolution of 1979. The backlash against the regime in the aftermath of Amini’s death has seen protests continued by university students despite mass arrests and a crackdown on their dormitories.

Still, nearly two months after Amini’s death, crowds of young people continue to stage sit-ins at universities across Iran.

“Her death was felt by all women in Iran, and the rest is a simple message of having enough of getting harassed by Ershad,” said Zahra, a woman in Tehran, who spoke to VICE World News under a pseudonym for security reasons.

Videos circulated on social media from Tehran Metro stations have shown Iranian women removing their scarves, including footage of a woman dancing inside the metro.

The government has said it will track women who defy the hijab laws using CCTV, but so far nobody has faced repercussions for protesting on the metro. Regime sympathisers trying to take photographs of women removing their headscarves have found themselves being booed and heckled by other commuters.

“It takes a person or two to start a noise in the crowd waiting on the platforms,” said Shirin, an Iranian woman speaking under a pseudonym for security reasons.

Shirin takes the metro every day. “[The protest] isn’t something new to the Tehran metro,” she said, “but it is slowly turning into a space where people feel safe to express their anger at the regime because people protect each other from the police, or anyone who would bother a woman for her clothing or head-covering.”

“People in Iran are learning to take matters into their hands, and there aren’t enough Ershad vans parked outside the metro stations to arrest us all,” another woman told VICE World News, speaking on condition of anonymity for security reasons.

The Iranian government only allows approved state media to operate in the country, and it describes the protest movement as “riots”.

“We Iranians usually roll our eyes at whatever the government says, and with mass protests ongoing in the country, they are the last people to listen to hear the truth,” said Maryam, an Iranian woman speaking under a pseudonym for security reasons.

President Raisi, a hardliner and a member of the clergy, came to power easily in an election last year. A favoured former student of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the country’s Supreme Leader, Raisi is expected to follow in his footsteps after his time as president is up. In Iran, clergymen – who are called mullahs – have the last say in every single political matter, even if there is a parliament and a functioning civil government on the sidelines.

“The mullahs have a picture of an ideal woman in their head, and even if it sounds ridiculous, we learned to live and put up with it all. But this summer, it just started to become too much to tolerate anymore,” Maryam added.

Iran has accused Israel and the US of fuelling the protests, but young women have had enough, a Tehran-based woman speaking under condition of anonymity, told VICE World News.

“The mullahs are like broken records and blame some foreign countries for every mess in the country,” she said, “but people have had enough of [listening to] every dumb regulation out there.”

READ MORE  'If GOP takes congress, Climate Action will be stalled, reversed.' (photo: Democracy Now!)

'If GOP takes congress, Climate Action will be stalled, reversed.' (photo: Democracy Now!)

The climate movement warns the midterm elections will either advance or torpedo climate initiatives in the U.S. This comes as climate activists and scientists at the U.N. climate summit in Egypt cautioned that the world is heading toward climate disaster without deeper cuts in planet-heating emissions. “We are up against a ticking time bomb of an unrelenting climate crisis and an economic crisis that is bearing down on working people,” says Varshini Prakash of the Sunrise Movement, which has reached 3 million young voters to get out the vote in the midterms. Prakash also explains how parts of President Biden’s climate legislation passed this year could be stalled or reversed if Republicans take back control of Congress in 2023.

For more, we’re joined by Varshini Prakash, co-founder and executive director of the Sunrise Movement, which has been helping to get out the vote.

Welcome back to Democracy Now! Varshini, we have a lot to take on here. Your organization, the Sunrise Movement, has always been a climate justice movement, combining the issue of climate crisis with human rights. At the U.N. climate summit, as we speak, we just heard the sister of Alaa Abd El-Fattah demanding his release from prison, a political prisoner. And at the same time, she and other climate activists are talking about the critical importance of being serious about dealing with the climate. Can you put it all together for people here in the United States, and especially on this Election Day, what these elections mean, not only for the United States but for the world?

VARSHINI PRAKASH: Absolutely. And thank you again for having me here.

We, as you have mentioned, we are up against a ticking time bomb of an unrelenting climate crisis and an economic crisis that is bearing down on working people and already hurting so many. This is not a domestic issue, this is a global issue. We have seen climate disasters like the hurricanes in Puerto Rico and Florida, the record heat waves all across Europe, I mean, Pakistan completely submerged, an entire country submerged, and the millions of climate refugees that are emerging from all of those collective crises. So, you know, and as you mentioned, the absolute paltry amount that historical polluters like the United States have contributed to countries to support the reparations and the repair that will need to be done from these major disasters.

And so, you know, we have passed earlier this year one of the largest pieces of climate legislation ever passed by a single country, and we saw how difficult it was to pass that climate legislation with a Democratic majority holding the House and the Senate and presidency, the fact that it had to go through, essentially, a coal baron in Joe Manchin. And the stakes of this election, if either of those houses — if either the House or the Senate goes to Republicans, is essentially that we have lost even a greater shot at federal legislation. We are seeing Republicans running who have said before that climate change is [bleep]. That was Ron Johnson, sitting senator in Wisconsin, whom Mandela Barnes is running against, who Sunrise has endorsed. They don’t believe in climate action. And that is why this election is so critical, because what is on the ballot is not Democrat versus Republican, it is a chance at greater action to stave off the greatest crisis of our generation, or, frankly, willful denial, after decades of science, that will lead to our collective annihilation. And so, you know, that is what is on the ballot today.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, Varshini, if that’s true, why do you think that the climate crisis has registered so low in terms of all polling of Americans as they head to the polls today, whether it’s the Republicans — their main concerns are inflation, crime, immigration. On the Democratic side, it’s the preservation of democracy and abortion, but very little talk of the continuing and escalating catastrophe on the climate. Why is that registering still so low among the American public?

VARSHINI PRAKASH: Yeah, I mean, there’s a lot going on in the world and in our country right now, and we have seen an effort on the part of Republicans to actively create disinformation and to revoke some of our most essential rights as humans, as Americans in the last couple of years.

But I think something that brings me hope in this election — and I work with a lot of young people — already we are seeing more young people registered to vote than we did even in 2018, and we are hoping for another record-breaking cycle for youth voter turnout. And I think a lot of that is because our generation is mobilized by things like taking action on climate change and student loan debt cancellation. It is essential that our government invests in our generation and in everyday people, and that young people actually respond well to that federal investment in them.

We’ve seen that in the polling, as well. So, looking at Biden’s poll numbers from the spring to now, young people were deeply unexcited to vote months ago. And after Joe Biden passed a climate bill, a gun bill and moved to cancel student loans, they have improved significantly.

There are still a lot of barriers along the way, and some of the main issues that we’re hearing on the ground are that young people don’t have enough information. They aren’t being communicated with in the way that other voters in these swing states do. But when they have the information and they are encouraged and supported to get out and vote, they are far more likely to vote for Democrats.

And so, we’re also hearing, you know, we’ve got young people — we’ve made over 3 million voter contacts across the country. We’ve got, you know, young people in dorms and talking to thousands of young people. We’re hearing that some of the top issues on the ground are climate change and abortion. And now we really have to connect the dots for people from the concerns they hold in their everyday lives to the policies that are being passed and the political terrain that can be won if they engage in these elections.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And can you talk about how both Democrats and Republicans are dealing with what seems to be a revival of the fossil fuel industry largely as a result of the war in Ukraine? You have the fracking industry in the United States, of course, now rushing to provide more gas to Europe as Europe searches for more sources of energy to replace its Russian supplies. How are both Democrats and Republicans dealing with this issue of — well, how do you fight climate change while at the same time allowing new growth in the fossil fuel industry?

VARSHINI PRAKASH: Yeah, yeah. Yeah, I mean, frankly, it’s the same refrain that we have been hearing for 40, 50 years. It is the same playbook of the richest industry in the history of the world, that is attempting to protect its bottom line and using every tool in its toolbox in its dying years in order to do so. And so, I think, frankly, what we saw with the war in Ukraine was the fossil fuel industry using that moment to say, “This is our opportunity to drill and frack and increase our reliance on oil.”

And we cannot afford to do so. I mean, we are seeing — everybody is seeing viscerally and with their own eyes the impact that this crisis is having on them. And it is only going to get worse from here. This is just the beginning. And so, we cannot afford to have this moment be increasing our dependency on our addiction to oil and gas. We need to use this moment and push people like Joe Biden to declare a climate emergency, to utilize things like the Defense Production Act to ramp up the production of renewable energy, and see it as, frankly, the largest national security threat that is posing, you know, us as — in America, as well as our global economy.

AMY GOODMAN: Varshini Prakash, I want to thank you so much for being with us, co-founder and executive director of the Sunrise Movement, speaking to us from Boston, Massachusetts.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.