Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

“They will never show you this on television, they will never tell you the truth,” a man identified as a Russian soldier tells family in what Ukraine says is an intercepted call.

Audio shared by Ukraine’s Security Service is said to capture an intercepted phone call between a soldier based in the Kharkiv region and a female relative outside Moscow. It was not immediately clear when the conversation took place, but the unnamed man’s complaints appear to echo those heard repeatedly from Russian troops throughout nearly five months of the war.

“We’re losing now,” the purported soldier says, prompting an indignant response from his female relative, who replies, “Well it’s you guys who are losing there, but they are winning everywhere [else].”

“That’s the picture they paint for you on television, but in reality it’s drastically different here,” he says. “They will never show you this on television, they will never tell you the truth. We’re losing.”

Taken aback by the confession, the woman asks him to explain how Russian troops could be losing—and there seems to be no shortage of answers.

“We should have about 90 tanks left, and you know how many we have left? We have probably 14 tanks left,” the man says.

“You don’t have artillery?”

“We do, but it’s so curved you can measure the [target] misses in kilometers,” he says, adding that “Everything’s sad.”

Even as his admission surfaced, Ukrainian authorities said Russian troops continue to bomb residential areas—a tactic they say is out of rage at so many military setbacks.

In the latest attack Wednesday, authorities said at least three people were killed when strikes hit a bus stop in Saltivka, in the Kharkiv region. A young boy was reported among the dead.

People hold a Ukrainian flag with a sign that reads: "Kherson is Ukraine," during a rally against the Russian occupation in Kherson, Ukraine, Sunday, March 20, 2022. (photo: Olexandr Chornyi/AP)

People hold a Ukrainian flag with a sign that reads: "Kherson is Ukraine," during a rally against the Russian occupation in Kherson, Ukraine, Sunday, March 20, 2022. (photo: Olexandr Chornyi/AP)

“Russian forces have turned occupied areas of southern Ukraine into an abyss of fear and wild lawlessness,” said Yulia Gorbunova, senior Ukraine researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Torture, inhumane treatment, as well as arbitrary detention and unlawful confinement of civilians, are among the apparent war crimes we have documented, and Russian authorities need to end such abuses immediately and understand that they can, and will, be held accountable.”

Human Rights Watch spoke with 71 people from Kherson, Melitopol, Berdyansk, Skadovsk and 10 other cities and towns in the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions. They described 42 cases in which Russian occupation forces either forcibly disappeared civilians or otherwise held them arbitrarily, in some cases incommunicado, and tortured many of them. Human Rights Watch also documented the torture of three members of the Territorial Defense Forces who were POWs. Two of them died.

The purpose of the abuse seems to be to obtain information and to instill fear so that people will accept the occupation, as Russia seeks to assert sovereignty over occupied territory in violation of international law, Human Rights Watch said.

People interviewed described being tortured, or witnessing torture, through prolonged beatings and in some cases electric shocks. They described injuries including broken ribs and other bones and teeth, severe burns, concussions, broken blood vessels in the eye, cuts, and bruises.

A formerly detained protest organizer, who requested anonymity, said Russian forces beat him with a baseball bat in detention. Another protestor was hospitalized for a month for injuries from beatings in detention. A third said that after seven days in detention he could “barely walk” and had broken ribs and a broken kneecap.

The wife of a man whom Russian forces detained for four days, following a house search in early July, said his captors beat her husband with a metal rod, used electroshock on him, injured his shoulder, and gave him a concussion.

Describing the pervasive fear, one journalist in Kherson said: “You don’t know when they’ll come for you and when they’ll let you go.”

Former detainees described being blindfolded and handcuffed for the entire duration of their detention and being held with very little food and water and no medical assistance. Russian personnel forcibly transferred at least one civilian detainee to Russian occupied Crimea, where he was forced to carry out “corrective labor.”

In several cases, Russian forces released detainees only after they signed a statement promising to “cooperate” with the authorities or recorded a video in which they exhorted others to cooperate.

In all but one of the detention cases, Russian forces did not tell families where their loved ones were being held, and the Russian military commander’s office provided no information to families seeking it.

The laws of war allow a warring party in an international armed conflict to detain combatants as POWs and to intern civilians in noncriminal detention if their activities pose a serious threat to the security of the detaining authority. Arbitrary detention, unlawful confinement, and enforced disappearances are all prohibited under international humanitarian law and may amount to or involve multiple war crimes. Torture and inhuman treatment of any detainee is prohibited under all circumstances under international law, and, when connected to an armed conflict, constitutes a war crime and may also constitute a crime against humanity.

For civilians, the risk of arbitrary detention and torture under occupation is high, but they do not have a clear option to leave to Ukrainian-controlled territory, Human Rights Watch said. For example, the journalist in Kherson told Human Rights Watch, “I have my own Telegram channel, I’m in their database, I had to go into hiding. I’ve been warned that they can come for me at any time. I don’t risk leaving because I’m on their [blacklist].” Thirteen people who did leave described harrowing trips through numerous Russian checkpoints and detention.

In an interview with Human Rights Watch, Tamila Tasheva, permanent representative of the Ukraine president in Crimea, who also monitors the situation in newly occupied areas in southern Ukraine, said that Ukraine’s authorities cannot verify the exact number of enforced disappearances in Kherson region. She said that human rights monitors estimated that at least 600 people had been forcibly disappeared there since February 2022.

“Ukrainians in occupied areas are living through a hellish ordeal,” Gorbunova said. “Russian authorities should immediately investigate war crimes and other abuses by their forces in these areas, as should international investigative bodies with a view to pursuing prosecutions.”

Russian forces invaded Kherson region, on the Black Sea and Dnipro River, on February 25, 2022, and on March 3 claimed to control its capital, Kherson. It was part of a broader invasion and occupation of Ukraine’s coastal south, which includes Melitopol and Berdyansk, cities in Zaporizhzhia region, and ultimately Mariupol, in Donetsk region.

Ukrainian forces have started preparing a counteroffensive to retake occupied coastal areas, Ukraine’s defense minister said in July. On June 21, an official in the Russian occupation administration stated that a “referendum” on Kherson region “joining Russia” was planned in the fall.

From the start of the occupation, Russian military targeted for detention or capture not only members of Territorial Defense Forces, who should be treated as POWs under international humanitarian law, but also local mayors and other civil servants, police officers, as well as participants in anti-occupation protests, journalists, or others presumed to have security-related information or to oppose the occupation.

Over time Russian forces also started to detain people, apparently at random, according to numerous sources. They also targeted community volunteers who distributed food, medicines, diapers and other necessities, all in very short supply in Kherson, to people in need.

Torture of Prisoners of War

On March 27, Russian forces captured, held, and repeatedly tortured three members of Kherson’s Territorial Defense Forces, Vitali Lapchuk, a commander; Denis Mironov, his deputy; and a Territorial Defense Forces volunteer “Oleh” together with a civilian, “Serhii,” whose real names are withheld for their protection. Mironov, 41, died from injuries inflicted during beatings in detention. Lapchuk’s body was found on May 22 in the bay in Kherson, his arms bound, and a weight tied to his legs. Oleh, who was injured from torture, was part of a prisoner exchange with Russian POWs held by Ukraine on April 28.

Denis Mironov and Oleh

“Oleh,” a Territorial Defense Forces volunteer, said that he was to meet Mironov and Lapchuk on the morning of March 27, but when he went to the appointed place, he did not see them. As he was about to leave, two men in civilian clothes approached him. They knocked him down and handcuffed him, then led him around the corner, where he saw three more men, whom he believed to be Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) agents, uniformed, heavily armed, and wearing balaclavas. Mironov and Lapchuk were standing against a wall, in handcuffs.

The FSB agents took the three men to the former National Police Directorate building in Kherson on 4 Liuteranska Street (formerly Kirova Street).

Oleh said that on the first day, he was blindfolded and interrogated for 12 hours, and that the agents beat him, gave him electric shocks, and tried to suffocate him with a plastic bag. “It’s impossible to say how many times they tortured me, because you lose all track of time,” he said. Eventually, he, Mironov, and Serhii, ended up in the same room. The agent knocked Oleh down. He said his blindfold shifted, and he could see the agents hit Mironov several times in the face and kick him in the groin. They took off Mironov’s trousers and beat him with a rubber club. “His body just turned into a blackened mess,” he said.

After more questioning, the agents took Oleh to a basement cell, where, approximately 30 minutes later, three men brought in a detached door and threw it on the floor. Two soldiers “practically carried in Denis [Mironov] … he was very badly injured … They lowered him down onto the door. He lay down and didn’t move anymore.”

The next day the men were taken to another building in the complex, which had been a temporary detention facility, and placed them in different cells. After about four days, Oleh was transferred to a larger cell. He had seen the date on an FSB agent’s watch, which he recognized as his own. He kept track of time by sticking pieces of chewed chewing gum on the wall.

On April 6, Oleh was transferred to yet another cell, together with Mironov.

“Denis was in pitiable state ... He spoke in a whisper, one word at a time … could not finish a sentence. He groaned, he could not cough, it was obvious that his chest was pierced, and his ribs were pressing on his lungs. He could not lie down properly … he could only sit.”

Russian personnel brought three cans, 250 grams each, of army rations every two days, for all five people in the cell. “They always took out chocolate and meat beforehand so only gave us these cans and some dry biscuits,” Oleh said. “I have not seen a piece of bread once that whole time. We all lost a lot of weight. Denis could eat only apple sauce … We spoon-fed him … For 22 days without any medical attention, he was slowly dying.”

At one point, Oleh’s captors forced him and two others to state on camera, with the flags of Ukraine and the far-right wing militant group, Right Sector, in the background that “the Territorial Defense Force in Kherson no longer exists, but there are still patriots, and everyone should fight.” “Later I realized they posted this video on social media, to see who would post likes and comments, [to entrap people],” he said.

On April 18, Oleh, Mironov, and the other cellmates were transferred to Sevastopol, in occupied Crimea. The next day, Mironov was taken to a hospital. “I was relieved … but it was too late for him,” Oleh said. Oleh was exchanged on April 28.

He said that seven of his ribs had been broken and were not yet healed when he spoke with Human Rights Watch on July 9. Most of his teeth were broken and at least six were missing: “I have a concussion. I continue to have severe headaches. All of our limbs were beaten … All of our backs, hips, buttocks, shoulders … were blue [from beatings]. Everyone’s kidneys had been beaten, so we peed pink.”

In a separate interview, Ksenia Mironova, Denis’s wife, told Human Rights Watch that on April 8, after Mironova left Kherson, an acquaintance called her and said a man had brought her Denis’ watch, and said that he was being held at the facility on Liuteranska Street (formerly Kirova Street), that he had chest injuries, could not walk, and had to be spoon-fed. Mironova wrote to the facility, which responded that no such person was there. After she learned he had been transferred to Sevastopol, she tried unsuccessfully to get information from Crimea about him.

On May 24, Mironova said, the Mykolaiv police phoned her to say Denis had died in the hospital. Oleh identified the body, upon Mironova’s request. He said that “the date of death was written in green antiseptic on his leg: 23.04.” The death certificate, issued by Ukrainian authorities who received the body and which Human Rights Watch reviewed, states the cause of death as “blunt trauma to the rib cage – hemothorax."

Oleh also said that Serhii, who had been detained with him, and the two other men, on eof them also a civilian, were severely beaten in detention, and that he saw Serhii with bruises and cuts on his head. He was released on April 5.

Death of Vitali Lapchuk

Lapchuk, 48, was not taken to the basement with the others on the day they were detained. Lapchuk’s wife, Alyona, a local businesswoman, said that at around 1 p.m. on March 27, she was at her mother’s house with her mother and her eldest son, when three vehicles emblazoned with the letter Z drove up to the house.

“My husband called me, and said ‘Open up, they’re going to take the weapons.’ I opened the door, and I almost passed out. His jaw was all black, broken, his eyes’ blood vessels were broken. His face was striped with rifle blows. … There were nine armed men with him. Vitali told one of them, ‘You gave me your word as an officer that [if I gave up the weapons] you won’t touch my family.’”

The armed men took Lapchuk to the basement, where the weapons were. Alyona could hear them beating her husband. Her mother, she said, got a Bible and started praying and weeping. When they brought Lapchuk back up from the basement, she said she could see blood coming out of his cheek and based on her previous experience as a medical worker, believed that he had a cheekbone fracture.

The armed men put bags over the heads of Lapchuk, Alyona and her son, and took them to the police station on Liuteranska Street (formerly Kirova Street), where they held them for several hours. “They asked me if I was a fascist … I told them that my grandfather was Jewish and that I was Ukrainian. They said, ‘there is no such country.’”

All the while Alyona and her son could hear them beating and interrogating her husband in the next room. “I told them if they thought he did something wrong, there are courts for that, but you can’t just beat a man to death,” she said. “I could not believe what was happening.”

Russian soldiers put Alyona and her son in a car and said that Vitali “was a terrorist and would answer to Russian Federation law.” The soldiers dumped Alyona and her son under a bridge, and they walked home, arriving at approximately 4 a.m.

Starting on March 28, Alyona searched for Lapchuk. After she learned of Oleh’s release, from Crimea, she said she searched all over Crimea, and also Rostov and Taganrog, through her friends and connections in Russia.

On June 9, a pathologist sent her a text, asking her to call the next day. “I knew immediately. I sobbed all night, then I called the prosecutor [in charge of Lapchuk’s case] and said, ‘I won’t survive this, call [the pathologist] yourself.’” The prosecutor later called Alyona, telling her that on May 22, a young man who had been catching crayfish found her husband’s body floating, his arms tied, a weight tied to his legs.

“All that time I had been praying that he was alive,” she said.

Protesters, Journalists, Activists

Media reported public protests against the occupation in Kherson, Berdyansk and Melitopol, in March, April and early May. Russian forces put some down violently, including in Kherson, using live bullets and wounding some protesters. Two witnesses said that Russian troops aimed for people’s legs; one said that he saw a man who was hit in the legs. Russian forces also hunted down community volunteers who distributed aid to people in need.

Human Rights Watch spoke to nine people who organized, participated in, or witnessed the protests or were community volunteers, all of whom had been detained by Russian forces.

Protesters

Kherson

Arkadiy Dovzhenko, 29, a marine biologist from Kherson, said that people in Kherson started protesting in large numbers from the beginning of the occupation and that he joined:

I was just a regular Ukrainian guy. But one day at a protest I picked up the microphone to say: ‘Russians, go home.’ That’s how they heard my voice … and decided I was the organizer. Then Russian journalists started coming, and we made the decision: that we will stop them from getting a pretty picture for their propaganda TV.

Dovzhenko described his detention on April 21:

That day they [began] throwing grenades with teargas. They shot people with real bullets. They aimed at people’s legs. I saw several guys who had to be carried away, who were shot. There was blood on the pavement.

Russian forces detained Dovzhenko as he tried to run from the scene, and took him, blindfolded and hands bound, to the basement of a police building, and from there to another room:

They hit me with clubs, punched and kicked me. It lasted for several hours … In about three hours they took me back to the basement. Then they brought me back up. They asked me the same questions. Who organized this protest rally? Who organized other protest rallies? They asked me if I knew anyone at ATO [Ukrainian military and security force operations in Donbas] [and] for addresses [of other] protesters. They also asked me questions about my religion … told me that Ukrainian Orthodox Christians were terrorists and renegades.

Russian forces held Dovzhenko for seven days, handcuffed and blindfolded for the entire time, interrogating him repeatedly every day. “They gave me water, but it was very bad … They fed us from their food rations. It was almost nothing.”

When they released Dovzhenko, he said, he could barely walk: “I had a brain concussion. I had several broken ribs and a broken kneecap.”

Dovzhenko left Kherson in May, but it took three days of harrowing travel through numerous Russian checkpoints to get 200 kilometers to safety in Kryvy Rih.

City in Kherson Region (name of the city withheld for security reasons)

A local municipal deputy from a city in Kherson region who participated in protests said that around June 7, Russian forces searched his home, beat him for two hours with a baseball bat, and held him, blindfolded, for 36 hours in a cell at a makeshift detention center at a children’s summer camp. They filmed him against his will stating he had agreed to become an FSB informer. They released him 24 hours later, threatening to hold him indefinitely if he did not stop protesting and doing volunteer work. After they returned to his home several more times to harass him, he fled the country.

“Anton,” Berdyansk

On March 18, Russian forces detained a protest organizer “Anton” in occupied Berdyansk at a traffic intersection, while he was delivering aid to people in the community. Anton told Human Rights Watch that they drove him, blindfolded and handcuffed, to what he believed was a local police station. The Russian forces asked him whether he was a protest organizer, and when he said no, they hit him with his shoe, knocking him over, and kicked and punched him for several minutes. “I told them I was not a protest organizer, just a patriot of my country, Ukraine. They said, there is no such country.”

The Russian forces made him take off his jeans, taped his legs together and continued beating him. They administered electric shocks through clips they attached to his earlobes, at first for a few seconds, then for up to 20 seconds, while asking questions about protests and his volunteer work. “Everything went dark and I saw orange spots,” he said. “They took an automatic [weapon] and pointed it at my groin and told me to prepare to die.”

After 90 minutes, they led him to a cell, where, he said, he coughed up blood for three hours. On his third day in custody, Russian security personnel blindfolded him and took him to the facility’s second floor, where they made him read on camera a statement they had written, that he had organized protests, urging people not to attend protests, and to trust the new authorities.

They warned that if he did not do the recording, they would detain his son and grandson. “One man held the [text], one filmed, and a third stood behind the camera with his automatic pointed at me. They made me read it twice, as they didn’t like the first one.” After three days in detention the Russian forces released him.

He sought medical help for numerous bruises, broken blood vessels in his eyes, and leg injuries. He left on April 5 for a city under Ukrainian control, where he was hospitalized and treated for the injuries, mainly to his ankles. “The soft tissue was crushed. I had about 20 centimeters of [swelling] under the skin and [was at risk of] gangrene. The [doctors] removed it and I had a skin graft. I lay in bed for 22 days without getting up [and] was discharged on May 18.”

Journalists and Volunteers

Novaya Kakhovka

On March 12, Russian forces detained and held incommunicado Oleh Baturin, a journalist from Kherson region. Baturin told Human Rights Watch that on the morning of March 10, he received a message apparently from his friend, Serhyi Tsyhypa, a former Donbas veteran, asking to meet. When Baturin did not see Tsyhypa at the rendezvous point in Kakhovka, a nearby town, he started walking away. Several men in military garb ran toward him: “They screamed for me to get on the ground, handcuffed me and pulled the hood of my jacket over my head so I could not see anything. They didn’t say who they were, did not tell me what I was accused of or why I was being abducted in this manner.”

The military took Baturin to a local administrative building, where they questioned and beat him: “They told me I was done with [journalism] and threatened to kill me.” Then they took him to the Kherson city police station, where he was questioned again. “All the while I could hear people screaming somewhere nearby and I heard shooting from automatic weapons.” Baturin spent the night in an unheated room at the police station, handcuffed to a radiator. The next day he was taken to a pretrial detention facility in Kherson, where he was questioned every day until his release on March 20.

Tsyhypa is still missing. His wife, Olena, said that witnesses saw him being detained at a checkpoint. A passerby found Tsyhypa’s dog, who was with him the day he disappeared, tied up outside city hall.

Snihurivka

On April 6, Russian forces detained Yurii, a Baptist pastor, at a checkpoint in Snihurivka, in Mykolaiv region, near the administrative border with Kherson region, where he had purchased food, medicines, and other basic items for the community in Kherson. After finding several photos on his phone of Russian military equipment, taken in the first days of the invasion, they drove him to a police lock-up.

They held him for six days, in a small freezing cell with no electricity, little food, and barely any water. They questioned him about his involvement in protests and his role as a priest in encouraging people to protest. They confiscated his car, with US$2,000 worth of medicines and humanitarian aid, and what he said was $6,000 of his own money. Russian soldiers at the checkpoint told Yurii that his car was with the FSB in Kherson. He was released under condition that he continue delivering aid to Kherson and pass on information about Ukrainian checkpoints to Russian forces.

Yuri fled Kherson with his wife the next day.

Local Officials, Civil Servants

In newly occupied areas, Russian authorities arrested numerous elected officials, business owners, community activists and people with influence, including the mayor of Melitopol, the mayor of Kherson city, and heads of local administrations. Tasheva, the Ukraine president’s representative, said that as of June 28, among the 431 cases of unlawful detention that Ukrainian law enforcement agencies had opened were six involving mayors of cities in the Kherson region, the heads of three local territorial administration units, 17 regional and local council members, and 43 law enforcement officials. She said 162 were still in detention.

Human Rights Watch documented cases in which a former municipal volunteer, a former policeman, and a head of a regional administration were either detained, or whose family members were unlawfully detained, apparently to pressure them. One remains in custody.

Russian forces in Kherson detained a 36-year-old former policeman on May 27, after they searched his house and found his police uniform and his father’s hunting rifle, his wife said. The man had worked on the police hotline.

The man’s family went every day to the military commandant’s office but were given no information on his whereabouts. “They told us that … that someone was ‘working on him,’” his wife said. Eventually she started going to the pretrial detention center, where on the 28th day of her husband’s detention, a guard accepted the food parcel she had brought for him. Her husband was released on July 12. His wife did not wish to discuss his physical condition, aside from noting that he bore “marks of physical violence.” “You know how they torture people there,” she said.

On April 8, Russian forces detained Vladyslav (Vlad) Buryak, 16, at a Russian checkpoint in Vasylivka, about 70 kilometers from Melitopol, as he was attempting to get to Zaporizhzhia, said his father, the head of Zaporizhzhia regional administration. The father had left Melitopol earlier fearing for his safety, but his son refused to leave because his grandfather was ill and could not travel.

As the soldiers checked passengers’ documents, one of them saw Vlad looking at his phone. They demanded to see it and found several pro-Ukraine Telegram channels on it. One of the soldiers told Vlad to get out of the car, pointed a gun at him and asked if he should shoot him on the spot. The military interrogated Vlad for three hours and, upon discovering who his father was, took him to a police holding facility in Vasylivka, where they kept him in a solitary cell. Buryak told HRW that while in detention, his son was forced to wash the bloodied floors in the facility, including in empty cells, “where Ukrainian [military] were tortured.”

After Vlad spent 48 days in detention, the Russian military transported him to a hotel in Melitopol, where he was held for an additional 42 days, but had regular access to a phone and was able to contact his family. On July 7, Vlad was released.

On June 30, armed Russian forces detained 40-year-old “Alina” and her ex-mother-in-law at Alina’s former husband’s house near Kherson, where they all had been staying since the invasion, Alina’s sister said.

The sister said she believes they were detained because of Alina and her former husband’s participation in the Kherson municipal guard, a community police force set up for a short period of time following the Russian occupation to address looting and destruction. The sister said she believes that the Russian forces have a list of all the participants and have detained many of them.

The soldiers detained Alina and her ex-mother-in-law and forced Alina to leave her 6-year-old son with a neighbor. The authorities released Alina the following evening, but her ex-mother-in-law remained in detention at the time of the interview. Alina delivers clean clothes and medicine to the facility for her ex-mother-in-law’s diabetes and liver problems. She said her ex-mother-in-law’s soiled clothes have blood stains.

Alina told her sister that she believes they are holding her ex-mother-in-law until her son, Aiyna’s former husband who managed to leave Kherson, returns to Kherson and they can detain him.

Other Enforced Disappearances, Unlawful Detentions of Civilians

Human Rights Watch documented 13 additional cases in which Russian forces apparently forcibly disappeared civilians, 12 men and a woman, in Kherson region. Russian forces in most cases did not tell families where their loved ones were being held and provided no information when the relatives inquired. Several were beaten in detention and one was unlawfully transferred to Crimea for “corrective labor.” Family members said none of them participated in the military.

Failure to acknowledge a civilian’s detention or to disclose their whereabouts in custody with the intention of removing them from the protection of the law for a prolonged period, constitutes an enforced disappearance, a crime under international law, and when committed as part of an attack against the civilian population can constitute a crime against humanity.

Still Forcibly Disappeared

“Yurii,” 43, Kherson

On May 26, Russian forces detained a local businessman “Yurii,” 43, in the parking lot of Kherson’s central market. His stepdaughter said that on July 14 her mother filed an appeal with the Russian military administration, who told her that Yurii was alive and that his case was “under review” but did not say where he was held.

At the end of June, a man contacted her mother, the stepdaughter said, and said he had been Yurii’s cellmate in a makeshift pretrial detention facility in Kherson, and that Yurii had spent several weeks in solitary confinement before being placed in the shared cell. He said there were plans to transfer Yurii to Crimea and then to Rostov, in Russia, supposedly on weapons possession charges.

His wife has visited the facility every few days with packages of food and clothing, which guards at the facility accepted but without confirming he was there.

“Bohdan,” 39, Ivanivka

Russian forces detained “Bohdan,” 39, a warehouse manager on April 29 in the town of Ivanivka in Kherson region. He remains missing. His family contacted the Russian occupying authorities but were given no information.

His wife said she had fled the town with their children in mid-March after Russian soldiers searched their house, questioned Bohdan and detained him for several hours. The next-door neighbors called her in late April and said that Russian soldiers came to the house in two cars and took Bohdan with them. Bohdan had called his wife the day before and told her Russian soldiers had taken his car, promising to return it.

“Dmytro,” 54 Ivanivka

On May 5, Russian forces detained Dmytro, 54, in Ivanivka, Kherson region. His daughter said that Dmytro called on May 4 to say he would be staying with neighbors for a while. Other neighbors told her that they saw Dmytro visiting his house on May 5 to feed his cattle, when soldiers arrived, handcuffed Dmytro, and took him away. The neighbors said that Russian forces had taken over the house, who said they knew nothing about Dmytro’s whereabouts and that “as long as we are here, he cannot come here.”

According to his daughter, Dmytro did not participate in the Territorial Defense Forces and was not a veteran of the war in Donbas..

"Stepan," 49, Oleshky

In the early morning of April 7, a group of approximately 10 armed Russian personnel came to the home of Stepan, 49, a driving instructor, in the town of Oleshky in Kherson region. His daughter, who spoke with her mother afterward, said that her father, mother, and younger sister were at home at the time. The men searched the house and yard, including with metal detectors, saying they were looking for weapons. They separated the family members and questioned them in different rooms. The soldiers referred to one of the men among them by nom-de-guerre “The Wind” (In Russian, Ветер)..

They took Stepan away with them in handcuffs, telling him to bring his identity documents and medicines, saying, “You’ll need them, since things will be very bad for you.” Stepan has pancreatitis, an inflammation of his pancreas, and osteomyelitis, a bone marrow infection, and is officially registered as having a disability.

On April 8, Stepan called his wife and his daughter, separately, from detention, saying that he had had a pancreatic attack, but had received medication and food and was not being beaten. His daughter said it sounded as if her father was speaking on a speakerphone. No one in the family has heard from him since.

A friend, acting on behalf of the family, went to the local military administration to ask about her father, the daughter said, but received no information. The family also contacted Ukrainian government agencies and hotlines and a pretrial detention facility in Crimea, without success.

Released

A woman named Mariia said that on June 25, Russian forces detained her husband, 30, a taxi driver, and her brother, 19, a naval academy student, with two other men in a shop in central Kherson owned by Mariia’s mother-in-law. Mariia said that the shop’s security cameras showed 10 to 15 armed Russian soldiers entering the shop, forcing the men to the floor, taking away their phones, and putting bags over their heads before taking them away.

After the detention, Mariia’s mother-in-law went to the local military administration to ask about the men. Officials did not share any information about the men and told her to wait.

They released Mariia’s husband after 7 days, her brother after 13 days, and the other men after three days. She said they were apparently held in the basement of a Kherson pretrial detention facility. Officials beat them and did not provide sufficient food. Mariia said her brother lost 10 kilograms. She said her brother had sent geolocations of Russian positions to Ukrainian intelligence, although Russian forces did not question him about this. During interrogations, the Russian forces asked questions that showed that “they knew everything about the men,” Mariia said. After the men’s release, she, her husband, brother, and mother-in-law left Kherson out of fear for their safety.

"Vasylii," Kherson

Russian forces detained Vasylii at his home on July 4, and held him for four days. His wife said she had been at home with Vasylii, their toddler child, and Vasylii’s parents. Seven Russian soldiers entered the house and told the men to go outside, and the women to go down to the first floor. The soldiers took photos of the family members’ identity documents, searched the house, and detained Vasylii.

In the evening, his family went to the local military administration office to ask about him, but officials gave them no information. Vasylii was released on July 8. He told his wife he had been held in a former pretrial detention center in Kherson. Russian forces beat Vasylii, used electroshock on him, beat him on his legs with a metal rod, injured his shoulder, and gave him a concussion, his wife said. He still has headaches and nightmares. When they interrogated him, Russians knew everything about him and his family, his wife said.

After his release, Russian forces told Vasylii they would come back to check in on him in three weeks. The family fled Kherson, fleeing for their safety. They have no idea why he was detained, but Vasylii was not in the Territorial Defense Forces, did not participate in the war in Donbas, nor in the pro-Ukraine demonstrations, according to his wife. His wife also told Human Rights Watch that Russian soldiers came to Vasylii’s car repair shop sometime in early April and demanded a payment of 5,000 hryvnia ($US169) to continue running the shop or to repair their cars for free. His wife said that Vasylii gave them the money and they left.

“Valentyn,” 48, Chaplynka

On June 8, 48-year-old Valentyn left his home in a village of Chaplynka, in Kherson region, about 50 kilometers from the administrative border with Russian-occupied Crimea, to go shopping and did not return. Valentyn’s daughter said that his mother, who is in her 70s and whom he cared for, looked for him on June 9 at the local police station, where Russian occupation officials told her he was detained “for drugs,” but did not say where they were holding him. They told her that she should move to a nursing home.

The mother went to the police station daily, and eventually was allowed to see her son. She told the daughter that Valentyn was “all beaten, very thin.” On a subsequent visit, the staff told her that he had been taken to Crimea. Russian authorities released Valentyn about a month after his initial detention, on July 4 or 5.

His daughter said that Valentyn told his family that he had been beaten and had been sent to Crimea for two weeks for “corrective labor.” Authorities did not return his identity documents and bank cards, and barred him from leaving the village. His daughter said Russian personnel allegedly detained several other villagers also on June 8, but she had no further information about them.

Legal Obligations

All parties to the armed conflict in Ukraine are obligated to abide by international humanitarian law, or the laws of war, including the Geneva Conventions of 1949, the First Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions, and customary international law. Belligerent armed forces that have effective control of an area are subject to the international law of occupation found in the Hague Regulations of 1907 and the Geneva Conventions. International human rights law, including notably both the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights, is applicable at all times.

The laws of war prohibit attacks on civilians, forced transfers of civilians, summary executions, torture, enforced disappearances, unlawful confinement, and inhumane treatment of detainees. Pillage and looting of property are also prohibited. A party to the conflict occupying territory is generally responsible for ensuring that food, water, and medical care are available to the population under its control, and to facilitate assistance by relief agencies.

The Third Geneva Convention governs the treatment of prisoners of war, effective from the moment of capture. This includes obligations to treat them humanely at all times. It is a war crime to willfully kill, mistreat, or torture POWs, or to willfully cause great suffering, or serious injury to body or health. No torture or other form of coercion may be inflicted on POWs to obtain from them any type of information.

Anyone who orders or commits serious violations of the laws of war with criminal intent, or aids and abets violations, is responsible for war crimes. Commanders of forces who knew or had reason to know about such crimes, but did not attempt to stop them or punish those responsible, are criminally liable for war crimes as a matter of command responsibility.

Russia and Ukraine have obligations under the Geneva Conventions to investigate alleged war crimes committed by their forces, or on their territory, and appropriately prosecute those responsible. Victims of abuses and their families should receive prompt and adequate redress.

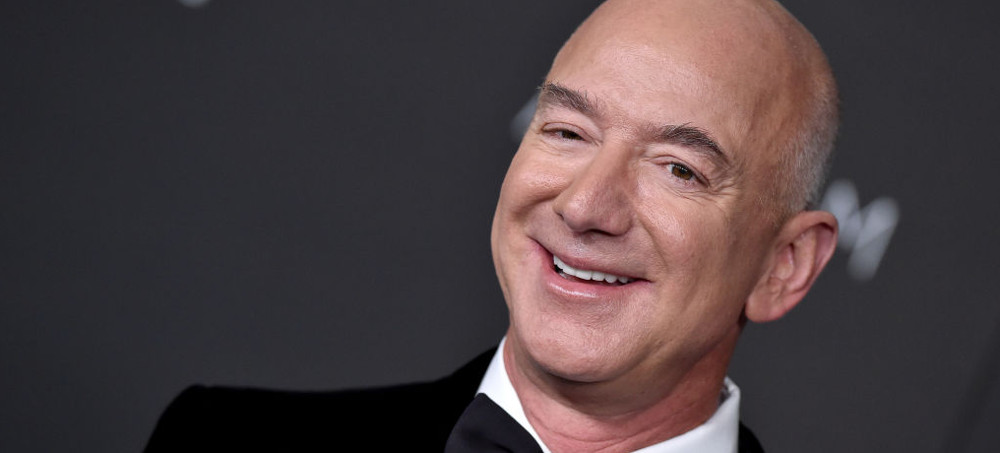

Jeff Bezos attends the 10th Annual LACMA Art+Film Gala presented by Gucci at Los Angeles County Museum of Art on November 6, 2021, in Los Angeles, California. (photo: Axelle/Bauer-Griffin/Getty)

Jeff Bezos attends the 10th Annual LACMA Art+Film Gala presented by Gucci at Los Angeles County Museum of Art on November 6, 2021, in Los Angeles, California. (photo: Axelle/Bauer-Griffin/Getty)

Amazon has announced it is acquiring One Medical, a private equity–backed primary care provider that generates most of its revenue from a for-profit Medicare program. It’s a terrifying sign of Amazon’s continued expansion and the privatization of Medicare.

While Amazon’s profits from its core consumer retail business are dwindling, in part because of heightened competition from brick-and-mortar retailers that were shut down at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the corporation’s cloud computing division, Amazon Web Services, continues to enjoy robust profits thanks in part to generous government contracts. Now Amazon could be attempting to build on that federal largesse by seeking to milk revenue from Medicare, the national health insurance program for seniors and people with disabilities.

Amazon, which has broad market power, reach, and influence, could use its new platform to advance the cause of Medicare privatization at a much more aggressive pace. The consequences wouldn’t just mean more taxpayer dollars funneled to the megacorporation but also Medicare recipients facing a health care system with ever more resources being allocated to profit instead of care.

The deal must go through normal regulatory approval processes. Advocates have pledged to oppose it.

“Amazon has no business being a major player in the health care space, and regulators should block this $4 billion deal to ensure it does not become one,” said Krista Brown, a senior policy analyst at the American Economic Liberties Project, which advocates on antitrust issues, in a statement.

She added in an interview, “It won’t make Amazon the largest player in health care, but will further dissolve integrity that is already on shaky territory with the health care system.”

As we reported in April, President Joe Biden’s Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has expanded a Medicare privatization scheme launched under former President Donald Trump. That program, which is currently referred to as ACO REACH, involuntarily assigns Medicare patients to private health plans operated by for-profit companies, like One Medical subsidiary Iora Health.

Medicare provides set payments to provide care for these patients, much like insurance. This arrangement incentivizes Iora and other privatization entities to limit the amount of care that seniors receive.

Continued expansion of Medicare privatization seems integral to One Medical’s business model.

The company’s most recent quarterly report shows that more than half of its revenue comes from Medicare. This includes Medicare Advantage plans operated by private health insurers, traditional Medicare fee-for-service payments, and the ACO REACH program.

One Medical’s most recent annual report notes, “A significant portion of our revenue comes from government health care programs, principally Medicare,” including specifically the ACO REACH privatization model.

The filing adds, “Any changes that limit or reduce the [ACO REACH model or] Medicare Advantage could have a material adverse effect on our business, results of operations, financial condition and cash flows.”

Like many mergers, both parties in Amazon’s new acquisition benefit from the arrangement. Amazon gets a more stable revenue source just as its retail segment is faltering, while One Medical gets Amazon and Bezos’s considerable political power. That power has led Congress to seriously consider granting Bezos a $10 billion subsidy for his Blue Origin space exploration boondoggle and has led Senate majority leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) to stall on holding a vote to hold a vote on bipartisan antitrust legislation being championed by Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN).

Amazon has a suite of powerful lobbyists at its disposal, including the lobbying firm run by the brother of Steve Ricchetti, who is the counselor to the president. The tech giant is the eighth-highest spender on lobbying in the country this year, according to data collected by OpenSecrets.

The Congressional Progressive Caucus has led the charge against the ACO REACH model. Representative Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) said in May:

The ACO REACH program is Medicare privatization, hidden in layers of bureaucracy. Essentially, seniors are put into this program, which allows a profit-seeking third party like a health insurer or private equity–backed firm to step in and get paid by Medicare to manage the care that they get. Taking for themselves the profit that is whatever they don’t want to spend on the patient.

But despite opposition from progressives, Biden, Health and Human Services secretary Xavier Becerra, and CMS administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure have resisted this pressure and continued to implement the program.

Observers also have concerns about the privacy impacts of Amazon acquiring One Medical.

“Allowing Amazon to control the health care data for another 700,000+ individuals is terrifying,” said Brown at the American Economic Liberties Project. “It will also pose serious risks to patients whose sensitive data will be captured by a firm whose own Chief Information Security Officer once described access to customer data as ‘a free-for-all.’”

Don't blame progressives for Biden's failures. It's the party's right flank that abandoned the working class. (photo: Chris Kelponis/Getty)

Don't blame progressives for Biden's failures. It's the party's right flank that abandoned the working class. (photo: Chris Kelponis/Getty)

Don’t blame progressives for Biden’s failures. It’s the party’s right flank that abandoned the working class.

The president’s approval rating has hit record lows, with some polls eclipsing the dismal support for his predecessors Barack Obama and Donald Trump. When it comes to the economy, which encompasses voters’ top-ranked concern, Biden’s approval stands at just 30 percent. As inflation continues to hit Americans in the pocketbook, especially high energy and food prices, a majority now say they believe the economy will get worse over the coming year — and expect a recession. Nearly 80 percent of respondents in a recent New York Times survey say the country is heading in the wrong direction, while 64 percent of Democrats want someone else to be the party’s nominee in 2024. In sum, the American public is handing down a harsh referendum on Biden’s leadership.

What’s behind these dire numbers? First off, the president’s agenda that voters elected him to enact — from curbing climate change to expanding childcare, guaranteeing paid family leave and taxing the rich — remains stalled in Congress, facing stiff opposition from conservative Democrats. Other campaign promises that Biden could fulfill through executive action, like canceling student debt, haven’t been acted upon.

Inflation numbers have reached record highs, leading to economic pain for millions of working people who face far higher prices for gas, rent, groceries and transportation, while wage increases haven’t nearly kept pace. These spiking costs have disproportionately impacted voters of color and younger Americans, the very constituencies that helped hand Biden the presidency. And when it comes to other crises, such as the scourge of gun violence and the Supreme Court’s gutting of abortion rights, the Biden administration has appeared wholly unprepared to meet the moment.

Which leads to another question: Who’s to blame? Well, if you ask the punditry class, the answer is simple — progressives and the Left.

In a Tuesday column at the Los Angeles Times, Jonah Goldberg says of Biden that, “one of the primary reasons he’s failing is that his agenda, and his rhetoric, caters to a progressive base that speaks for a minority of voters.” At CNN, meanwhile, Democratic strategist Paul Begala writes that, by pushing Biden to take a stronger tack to implement his stated policy goals, “progressives are practically doing the GOP’s job for them.” Instead, Begala implores, those on the Left should stop complaining and simply “strengthen him, so he can lead the way forward.” And at Yahoo! Finance, columnist Rick Newman argues that ahead of the midterms, the party should move to the center, writing, “the majority of Democrats themselves may have now tired of progressive visions of a mythical Shangri-La.”

What all of these critiques miss is a simple fact: Ever since Biden took office, progressives have been working to make his agenda a reality and bring relief for the very working people now facing economic havoc, while Democrats on the right flank of the party have obstructed this program every step of the way. But rather than deal with the uncomfortable truth that so-called “moderates” are the ones imperiling both Biden’s presidency and Democrats’ electoral fortunes, establishment-friendly commentators are yet again lazily training their sights on their favorite scapegoats — the Left.

The slow death of Build Back Better

Last summer, as the then-$3.5 trillion Build Back Better (BBB) plan was still moving through Congress, Biden said of the legislation, “A vote against this plan is a vote against lowering the cost of healthcare, housing, childcare, eldercare, and prescription drugs for American families.” Democratic leadership had planned to couple votes for BBB alongside a $1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill in order to codify Biden’s economic blueprint in one fell swoop. Progressives played a key role in selling BBB, both to the American people and to the Democratic caucus.

In November 2021, after the House had passed a version of the bill, Senate Budget Committee Chairman Bernie Sanders (I‑Vt.) urged his colleagues in the Senate to support the budget resolution, claiming that “what we are trying to do is address the needs that working people are facing in America that have been neglected for decades.”

Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D‑Wash.), head of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, made a similar point, saying last fall: “We have been so united in standing up for the president’s agenda in really making sure that we don’t leave behind women who need childcare, families who need paid leave, communities that need us to address climate change, housing, immigration. These are the things we’re fighting for in the Build Back Better agenda. And it’s the president’s agenda.”

Far from catering “to a progressive base that speaks for a minority of voters,” as Jonah Goldberg claims, BBB is popular across the political spectrum. Polling has shown that a clear majority of Americans back the legislation itself, as well as the constituent elements of the bill: universal pre‑K, free community college, long-term care investments, modernizing the electricity grid, lowering the Medicare age, capping the costs of prescription drugs and creating a Civilian Climate Corps all command over 50 percent support.

In short, both the U.S. public and progressives in Congress want Biden’s agenda to become law. But instead, BBB is “dead,” according to Sen. Joe Manchin (D‑W.V.) — one of the right-wing Democrats responsible for killing the bill.

Rather than keeping the infrastructure and BBB bills coupled, last year Manchin and his fellow conservative Democrats demanded that they be separated, with the bipartisan bill to be voted on first. While a number of progressives ultimately voted against the infrastructure bill in protest, including Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D‑N.Y.) and other members of the Squad, the majority of Democrats conceded and agreed to support it after Biden reportedly assured them that he would bring along holdouts, including Manchin, to get behind BBB.

As Jayapal said in December 2021, “the version of Build Back Better we passed out of the House was agreed to by nearly every senator caucusing with the Democrats — and we sent it to the upper chamber based on the president’s promise that he could deliver the 50 senators needed to make it law.”

But that didn’t happen. Instead, Manchin and self-described moderates such as Reps. Josh Gottheimer (D‑N.J.) and Abigail Spanberger (D‑Va.) took a victory lap once the bipartisan bill passed, before Manchin declared at the end of last year that he would not support BBB, effectively thwarting key planks of Biden’s agenda. The bill has remained in a holding pattern ever since, with negotiations sputtering time after time as Manchin — a coal baron taking money from Republican billionaires — declares that he cannot get behind proposals like spending to address climate change and increasing taxes on the wealthiest Americans, as he did earlier this month.

And it’s not just Manchin. Along with Gottheimer and Spanberger, other conservative Democrats including Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D‑Ariz.) and Rep. Kurt Schrader (D‑Ore.) voiced their opposition to BBB at various stages of the process, though they generally received less attention than Manchin for blocking the legislation. There are likely other members of the Democratic caucus similarly opposed to more spending on social programs who’ve been happy to stay quiet as more high-profile Democrats attract attention for knifing the budget package.

Rudderless Democrats

The impact of BBB’s failure has been profound. Housing projects that would have been funded through the bill are being abandoned, as are investments in climate mitigation efforts. Parents are being forced back to work due to the lack of a national paid leave policy. Students continue to rack up more debt without any guarantees of tuition-free college. The list goes on. And Democrats are left without a clear message to voters about what they accomplished as they head into an extremely challenging midterm election season.

To take one striking example, as a result of BBB’s failure, Democrats were unable to extend the expanded Child Tax Credit (CTC) that helped fortify recipients’ bank accounts last year. One of the most transformational economic policies enacted in over a decade, the expanded CTC lifted millions out of poverty and cut the child poverty rate by roughly 30 percent. According to data from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 91 percent of low-income families used their monthly benefit payments on basic needs such as food, clothing, school supplies and rent. As inflation increases and the credit has dried up, those costs are now swelling for the working class.

The expiration of the CTC has plunged 3.7 million more children in the United States back into poverty, and nearly half of families with kids can no longer afford enough food. Along with the disastrous human toll of this policy decision, Democrats are also suffering politically. Before the expanded CTC expired, the party held a 12-point advantage among recipients of the program. But by April of this year, after payments stopped, that edge disappeared, with Republicans gaining the upper hand among this group of voters.

Progressives have long been the strongest champions of the expanded CTC, and it was the reluctance of conservative Democrats like Manchin to approve an extension that led to the program’s demise. Allowing parents to buy enough food for their kids was not some progressive vision of “a mythical Shangri-La,” as in Rick Newman’s words. Rather, it was a life-changing policy that voters are now blaming Democrats for ending.

Stoking a crisis

On issue after issue, from expanding abortion rights to enacting more forceful gun control laws, progressives in Congress have offered solutions more in line with the views of the U.S. public than those being pursued by either moderate Democrats or the Biden White House. That’s not to mention other more far-reaching, left-wing policies that are broadly popular, including Medicare for All, a federal jobs guarantee and a Green New Deal.

To respond to inflation, progressives have pushed for policies that would punish corporations that are jacking up prices on consumers while raking in record profits. One proposal would impose a windfall tax on the profits of Big Oil companies, which are rewarding wealthy shareholders with stock buyback programs. Others are proposing measures to crack down on corporate price gouging and dominance of supply chains, including by the meat industry, where just four beef companies control 85 percent of the market. Polls suggest that this response to inflation would be favored by the public. The Federal Reserve, meanwhile, with Biden’s blessing, is taking the opposite route, raising interest rates — which will likely lead to higher unemployment and decreased worker bargaining power, i.e. more neoliberal austerity.

If the chattering classes were serious about assessing the reason for Biden and the Democrats’ shrinking poll numbers, they would place blame on the real culprit — an unwillingness among the party establishment to take bold action to address the issues facing the country, from a broken healthcare system to economic plunder of working people by the super rich to bought-and-paid-for politicians acting on behalf of their corporate funders.

By instead chiding the Left, these commentators are repeating the tired ritual of treating progressives not as partners in Democratic governance, but rather as whiny children who should stay quiet while the adults among the party elite take charge. As Jamelle Bouie writes at the New York Times, “Somehow, the people in the passenger’s seat of the Democratic Party are always and forever responsible for the driver’s failure to reach their shared destination.”

This left-punching is also taking a page out of the handbook of former President Trump, who recently denounced “Radical Left Democrats” for high inflation and the country’s economic woes. As for the power brokers in the Democratic Party, they’re busy funding the campaigns of extremist pro-Trump election deniers in Republican primaries, part of a bid to stem Democratic losses in the midterms — a strategy that could easily backfire, and one that could easily be described as “practically doing the GOP’s job for them,” as Paul Begala put it.

In 2020, voters elected a president who promised an agenda of lifting up the working class by redistributing wealth downward, investing in social programs and tackling the climate crisis. Progressives have worked relentlessly to help Biden deliver on these pledges, while right-wing Democrats have stymied him again and again. The crisis facing the administration is on their hands, no matter what the mainstream pundits try to tell you.

People visit a mural depicting photos of American hostages around the world, created by the Bring Our Families Home Campaign, is seen in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C., July 20, 2022. (photo: Sarah Silbiger/Reuters)

People visit a mural depicting photos of American hostages around the world, created by the Bring Our Families Home Campaign, is seen in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C., July 20, 2022. (photo: Sarah Silbiger/Reuters)

The families want to raise awareness and pressure the Biden administration.

The mural features 18 Americans held in other countries. There are currently 64 known citizens being detained outside the U.S., according to the James W. Foley Legacy Foundation.

The mural includes WNBA superstar Brittney Griner and former Marine Paul Whelan, who have become faces of the issue because of their ongoing detentions in Russia. (Griner was arrested and later pleaded guilty to illegally bringing hashish oil into the country, though she said it was "inadvertent" and was part of her vape cartridge. Whelan was charged with espionage, which he and the U.S. government deny.)

The 15-foot-tall installation aims to bring attention to Griner, Whelan and to a series of under-recognized Americans being held around the world, sometimes for political leverage.

Many of the images used for the mural are of the last pictures taken of the detainees.

While Matthew Heath's portrait depicts him with a soft smile in his crisp Marine uniform from when he served, his mother, Connie Haynes, said he is currently being tortured in Venezuela after more than two years in detention.

She claims Heath has been repeatedly beaten and left with both hands broken and his retina detached and has at random intervals been fed carbon monoxide while locked in a 2 square-foot box.

Heath tried to kill himself this year but was still being abused and chained to his bed in the medical facility where he was being watched, according to his mom.

"My son is not going to survive if our government does not get him home," she said Wednesday. "I don't know how much more he can endure."

During the unveiling, Haynes was interrupted with a call and rushed to end of the alley next to the mural. Her son was trying to reach her.

"We were able to tell him what we're doing, for him, for the other families -- how hard we're working to try to get him home," Heath's uncle, Everrett Rutherford, said afterward.

They were also able to connect Heath with the Biden administration's special presidential envoy for hostage affairs, Roger Carstens, who spoke Wednesday.

During the rare opportunity to talk with Heath, Rutherford said he and Heath's mom were able to "give [Heath] a bit of courage and hope."

State Department spokesman Ned Price on Wednesday called the mural "a powerful symbol of those who have been deprived and taken from their loved ones" and said Carstens' presence at the unveiling was an important way "to continue to show our support for these families who are enduring an ordeal that to anyone but them is unimaginable."

"These efforts are -- by necessity -- quiet," Price said when asked about the frustration of some of the detainees' families about the future. "We have found that these cases often are best worked behind the scenes. Even though we don't speak of it, it doesn't mean that we aren't working around the clock to see the successful resolution and outcome."

The mural's artist says it was designed to be impermanent.

The Americans' faces, plastered using flour, water, sugar and paper, will "fade, tear and eventually disappear over time," Isaac Campbell explained in a press release. That fleeting quality is meant to add a sense of urgency for the government to "use the tools available to bring these Americans home -- before their faces fade away and disappear from this wall," Campbell wrote.

"This doesn't go away," said Neda Sharghi, the only sister of Emad Shargi, a dual citizen who has been detained in Iran since 2018 on claims he is a spy.

The siblings' father, who "felt like there was hope to bring his son home" while watching the unveiling, fainted and was taken away in an ambulance out of the event, Neda Shargi said. "This is our world," she added.

"Any second my father could pass and not see his son anymore," she said. "But I don't want to cry," she continued, calling on anyone struck by the new mural to call their representatives to "let President [Joe] Biden know that you will all stand with him if he can bring Americans home."

Wednesday's ceremony comes one day after Biden signed an executive order that declared hostage-taking and the wrongful detention of U.S. citizens a national emergency.

The order is meant to leverage more financial sanctions against those who are directly or indirectly involved in such detentions. Additionally, the State Department added new warnings on its travel advisories to help citizens avoid locations overseas where they risk wrongful arrest.

The White House informed relatives of American detainees of the executive order before its signing in a Monday call that was characterized as a "one-way conversation" by Jonathan Franks, a spokesman for a network of families and the Bring Our Families Home Campaign. He claimed the White House's latest actions were "an effort to pre-manage the press attention" around relatives of those detained arriving in Washington this week.

While some families have commended the move to improve transparency and intelligence-sharing between the federal government and concerned relatives of those held overseas, others have expressed vexation with their lack of communication with the president.

"We are definitely grateful," Hannah Shargi, the daughter of Emad Shargi, told ABC News of Biden's recent actions. But she said she wants to see, at minimum, meetings between families and Biden organized by the country where their relative is detained.

"We know that they're suffering. We know they're scared. And we know they're anxious," White House spokesman John Kirby said at a briefing on Tuesday. "We know they want their loved ones back home, and the president wants that, too."

Meanwhile, they work and they wait.

"I used to walk these streets with him," Hannah Shargi said Wednesday next to the mural that features her father. "It gives me some hope that he is larger than life here. And he is larger than life in real life -- so I'm glad people are seeing him how I see him."

Commuters wait in line to board a bus in San Salvador on July 19, 2022, as El Salvador's gamble on bitcoin is exacerbating a debt crisis. (photo: Camilo Freedman/Getty)

Commuters wait in line to board a bus in San Salvador on July 19, 2022, as El Salvador's gamble on bitcoin is exacerbating a debt crisis. (photo: Camilo Freedman/Getty)

22 july 22

Garcia is a 46-year-old minutas, or shaved ice, seller in El Zonte, a beachfront community of a few thousand people in El Salvador that’s being aggressively rebranded as Bitcoin Beach. A potbellied man not much more than 5 feet tall, Garcia is used to pushing a cart through the sunshine, lugging around supplies, selling sweet ice treats to locals and tourists, including Bitcoiners, some of whom are buying up property in the area. Garcia was almost a Bitcoin Beach mascot, appearing in YouTube interviews, tweeted about by influencers, and featured in Diario El Salvador, a government-owned newspaper. Bitcoin Magazine, which has offered extensive, enthusiastic coverage of El Salvador’s use of bitcoin as legal tender, highlighted a sign on Garcia’s cart that read “aceptamos bitcoin,” calling the minutas seller and his wife “Bitcoin pioneers.”

But on April 11, police pulled Garcia aside in El Zonte. They stripped him down and checked his decades-old tattoos for gang signs (a faded one on his left hand reads, in English, “FUCK YOU!”), and he was arrested. After two days in police custody, he was taken to Mariona, the country’s largest prison. With no access to a lawyer or formal charges filed, Garcia was told he might be imprisoned there for years, even decades.

Under the current state of emergency introduced by Bukele and his Nuevas Ideas party, civil liberties in El Salvador have been suspended in the name of fighting rampant gang violence. Now, people disappear in often arbitrary arrests, and families hear nothing. Prisons once open to visitors and journalists are closed shops. Police have triple-digit daily arrest quotas. The goal, as some Nueva Ideas officials have publicly said, is to arrest all of the supposedly 70,000 gang members in the country. In the first 10 weeks, an estimated 36,000 people were arrested, and according to the human rights organization Cristosal, at least 63 people had died in detention as of July 20, when the Bukele regime extended the state of emergency for a fourth time. Bukele said that the error rate for innocent people arrested was no more than 1 percent.

Garcia was lucky to get out. Dana Zawadzki, a Canadian woman who owns a small local cafe and runs an informal vet clinic to sterilize the many stray dogs in the area, knew him, describing Garcia and his family as “very near and dear to my heart.” She worked with Garcia’s wife, Dominga, to start an online campaign in which they called for the local bitcoin faithful, some of whom are well-known online influencers with lines of communication to the Bukele administration, to oppose Garcia’s detention and to donate money to his family. Eventually the campaign attracted attention on bitcoin Twitter, where Bukele is a confirmed participant-observer. Weeks later, Garcia was mysteriously freed.

Messages to several Bukele officials, including his brother Karim, who occupies no government position but is a close adviser to the president, went unreturned. Attempts to contact the president via his preferred medium — Twitter — were unsuccessful, except in causing a minor Salvadoran social media flurry that an actor from the TV show “Gotham” was in town. (Ben McKenzie, co-author of this piece, played Commissioner Jim Gordon; Bukele has long referred to himself as Batman and tweets Batman memes.)

Outside Mariona prison, north of San Salvador, women arrive and await information on their arrested male relatives. An encampment has developed, with makeshift kitchens, bathrooms, and laundry stations. The women wait for people like Mario Garcia, who is one of many casualties of a recent political crackdown that Bukele imposed after a secret deal between the government and the country’s major gangs crumbled. Now, a clandestine detente has given way to government forces kicking in doors and stopping men on sidewalks to check their tattoos.

In street markets in San Salvador, El Faro reported, vendors have started to sell prison uniforms that people buy to send to their incarcerated loved ones. The prevailing narrative is that the mass-arrest policy remains popular — a recent Salvadoran newspaper poll found Bukele with an 86.8 percent approval rating. On occasion, the Bukele government declares — perhaps improbably — that no murders have occurred in the country for 24 hours.

The ruthless battle against gang violence accords with Bukele’s attempt to project a tough-guy image. After El Salvador’s president got into bitcoin, he began courting online personalities and cryptocurrency executives, referring to himself as a “cool dictator” and the “CEO” of El Salvador. There was hardly a bitcoin influencer with whom he wouldn’t pose for a photo. His government released lavishly produced, short promotional films that combined Hollywood-style production values with well-armed Salvadoran troops doing macho military stuff and taking down evil-doers — all at the command of their brave president.

Despite the Salvadoran government’s occasional flair for marketing, the country faces enormous economic challenges, a debt crisis, constant struggles with crime and violence, a diplomatic row with the United States, and the mercurial rule of Bukele, who might be glibly described as a Salvadoran blend of Donald Trump, Filipino President Rodrigo Duterte, and an incredibly online bitcoin influencer. In 2021, Bukele reshuffled the judiciary, appointing new judges who then creatively interpreted the country’s constitution to allow a president to run for reelection. Filling government posts with relatives and friends from high school, Bukele runs El Salvador almost like a family enterprise. The business’s finances may be teetering, but with his policy of mass arrests and censorship laws targeting independent news outlets, Bukele appears determined to further consolidate power.

Looming over all this is the ongoing fallout of Bukele’s disastrous bitcoin project. In June 2021, at a video presentation at a bitcoin conference in Miami, Bukele announced that his country would be the world’s first to adopt the digital token as legal tender. On September 7, 2021, bitcoin was officially introduced in El Salvador to much propagandistic fanfare and some discontent, including social protests. That day, the global crypto markets crashed, with a number of exchanges unexpectedly shutting down. Numerous reports of fraud and identity theft followed; one local coiner told us that his friend used a photo of a dog to verify his identity. Rampant technical problems plagued the rollout of Chivo, the official wallet in which all citizens would receive $30 worth of bitcoin (whose value has since plummeted). Overall adoption has been minimal, with most people still preferring U.S. dollars, the country’s other legal tender. Nor has bitcoin proved useful with remittances, which are key to El Salvador’s economy: Less than 2 percent of remittances sent to El Salvador now use bitcoin.

The bitcoin project itself is run by a tangled mess of government and private interests, some of them foreign; few outsiders know who holds what or where. Bukele brags on Twitter that he buys bitcoin, using the state treasury, on his phone while sitting on the toilet. He’s never posted the wallet address he uses so the public can scrutinize these transactions, but if they’re real, he’s millions in the red. And so are his people.

Wilfredo Claros lives with his wife, two children, and other family members on a small plot off an unpaved road in a verdant area low in the mountains around La Unión, a town in El Salvador’s east. Chickens, dogs, and one frequently annoyed turkey roam the property, where Claros built his cinderblock house. He feeds his family by farming, fishing, and plucking mangos that practically fall out of the sky. They drink water from a well and cistern system, which an earlier generation of family members built under the shade of Parota trees, a broad-canopied member of the pea family that yields a rich, caramel-colored wood. Claros credits its cool water with keeping his family healthy during the Covid-19 pandemic.

That’s for now, at least. Claros, like dozens of his friends, relatives, and neighbors, knows his land is set to be cleared and incorporated into a new airport to serve Bitcoin City. It’s still unclear how many people will be affected. The Salvadoran government hasn’t done a census in at least 15 years.

Bukele promises to turn a concept, which for the moment exists as a golden model on Twitter, into a physical city underwritten by crypto mining and geothermal energy — and tourism dollars. The government hasn’t adequately explained to locals why the digital currency is shaking up their lives, but they know this much: Some of them have to leave. Their land is needed for Bitcoin City.

No one we queried thought that El Salvador, a country about the size of New Jersey, needed another airport, except perhaps as a place to bring in private jets of crypto elites or anyone else favored by the regime. The planned future site of Bitcoin City is a sleepy, charming region with some beach and hiking possibilities for tourists, but there’s nowhere near the demand — or infrastructure — necessitated by an airport project. La Unión, which is a few miles from the Honduras border, is an unassuming coastal town that happens to be a hub for the regional narco trade. Cocaine passes through, some of it moving up the coast in the false bottoms of local fishermen’s boats. The mayor of the nearby town of Conchagua, who was living in Houston for 10 years before Bukele’s Nuevas Ideas party enticed him back to the country, has a brother who’s been accused of being a narco trafficker. (Overall, cocaine seizures have declined under the Bukele administration.)

Neither Claros nor his neighbors know when demolition day will come or where they’re expected to go. They don’t know why the area, full of flora, livestock, and a healthy community, needs to be bulldozed for an airport. There’s a sense of helplessness on behalf of locals, who share what little they know through a WhatsApp group. “We deserve information,” said Claros.

Claros emphasized the unfairness of his predicament, facing eviction without pretext and without much information. “I can’t go to Bukele’s house and claim his house and take it away,” Claros said. “I’d be shot. Why can that happen to me?”

On March 26, at least 62 people were murdered across El Salvador — one of the most violent days the country experienced since its civil war, which began, by many accounts, with the 1980 assassination of the archbishop Óscar Romero and lasted until 1992. Thirty years later, the high death toll shocked the country of about 6.5 million, and Bukele’s government declared a state of emergency the following day. Under Bukele, El Salvador, in a rather short period of time, has exchanged the world’s highest murder rate for its highest incarceration rate. (With an estimated 2 percent of adults in prison, El Salvador now reportedly incarcerates more people per capita than the United States.) Bukele loyalists and many Salvadorans call the policy a success, at least from a public safety perspective, but questions linger: How was this supposed reduction in homicides achieved, and at what cost?

Publications by El Faro, Reuters, and the U.S. Treasury Department have offered answers, revealing that the Bukele regime, like some of its predecessors, had reached secret deals with the major gangs, which include MS-13, 18th Street Sureños, and 18th Street Revolucionarios. On May 17, El Faro reported on seven audio recordings of a Bukele official talking to gang leaders and lamenting a breakdown in relations. The recordings revealed backbiting among Bukele officials (who referred to the president as “Batman”) and wobbly relationships between the government’s designated negotiator and some of the gang leaders. They also unveiled prior close collaboration: a high-ranking Bukele official said he had personally pulled a gang leader wanted in the United States out of prison and taken him to Guatemala; the leader is no longer in government custody and has reportedly made it to Mexico. At the same time, the gangs saw the Bukele regime as guilty of betrayal when it promised safe passage to other gang members and then arrested them. The gangs’ outburst of ultraviolence — which targeted ordinary people, not just rivals — was their angry response, a vicious flexing of their power. The violence has since leveled off, by Salvadoran standards, but it also helped justify the government’s mass-arrest campaign.