Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Never mind the opinion polls and the Republican posturing. When the right sees Putin, they want what he's got

Robert McNamara, who was secretary of defense under Lyndon Johnson in the 1960s and one of the chief architects of the disastrous war in Vietnam, is the film's subject. If you let people talk, they will show you who they really are. Morris demonstrates great skill at allowing villains to speak for themselves, and in doing so to reveal their complexity — and their sincere belief in their own victimhood and heroism. "The Fog of War" is a masterclass in that lesson, one which all interviewers and those others who use words for a living should internalize.

In the film, McNamara tells this story from his World War II past:

The U.S. Air Force had a new airplane named the B-29. The B-17s and B-24s in Europe bombed from 15,000, 16,000 feet. The problem was they were subject to anti-aircraft fire and to fighter aircraft. To relieve that, this B-29 was being developed that bombed from high altitude and it was thought we could destroy targets much more efficiently and effectively.

I was brought back from the 8th Air Force and assigned to the first B-29s, the 58th Bomb Wing. We had to fly those planes from the bases in Kansas to India. Then we had to fly fuel over the hump into China.

The airfields were built with Chinese labor. It was an insane operation. I can still remember hauling these huge rollers to crush the stone and make them flat. A long rope, somebody would slip. The roller would roll over [that person], everybody would laugh and go on.

That story of laughter and death and numbness applies to America's current situation as well. Former Trump White House press secretary Stephanie Grisham recently told "The View" that Donald Trump wanted the power to kill with impunity. In explaining why Trump both admired and feared Vladimir Putin she said:

I think he was afraid of him. I think that the man intimidated him. Because Putin is a scary man, just frankly, I think he was afraid of him…. I also think he admired him greatly. I think he wanted to be able to kill whoever spoke out against him. So I think it was a lot of that. In my experience with him, he loved the dictators, he loved the people who could kill anyone, including the press.

A healthy society would have been stunned, disgusted, terrified and moved to action by Grisham's confession. The evident fact that Trump is a sociopath would have been the subject of extensive news coverage. If America were a healthy society, we would have an ongoing "national conversation" about the peril the country experienced from Trump, his Republican-fascist allies and their movement — danger that has only grown stronger.

A healthy society would now ask: How can we prevent another Donald Trump, another fascistic, sadistic demagogue, from ever coming to power?

What does it say about American society that Donald Trump and his cabal of coup plotters and other enemies of democracy and freedom have not been punished? That they are plotting in public how overthrow American democracy and return Trump to power without fear of punishment or other negative consequences? And that Trump still has many tens of millions of followers — many of whom are potentially willing to engage in acts of violence, and perhaps even die, at his command? What does that say about a country and a people?

What was the response to Grisham's comments about Donald Trump's desire to commit murder? Silence and indifference. Neither the media nor the American people seem to care. They have become desensitized to what not long ago would have been judged unconscionable.

America is a pathocracy. The masses take their cues from corrupted elites. Malignant normality is the new normal. Political deviance has been normalized. The Age of Trump constantly offers further proof that a sick and broken society can accept just about anything, no matter how surreal and grotesque

Fascism thrives in such societies. But the poison could not have spread so quickly if the soil and foundations were not toxic to begin with.

It is not adequate simply to say that Donald Trump idolizes authoritarians, demagogues, political strongmen and tyrants. The essential question must be this: Who are the specific objects of ideation and worship for Donald Trump, the other American neofascists and their followers?

The most prominent example, of course, is Vladimir Putin. The American people and the world should not be swayed and bamboozled by the Republican Party and its propagandists, who are now trying to claim that they are diehard Cold Warriors, forever united against Putin and his aggression. The American people and the world should also not be seduced by superficial public opinion polls that purport to show that Republican voters are now vigorously anti-Putin and do not support his war against Ukraine.

Today's Republican voters and other Trumpists are part of a political cult. They follow, uncritically, whatever directives and various signals are sent to them by Donald Trump, Fox News, the white right-wing evangelical churches and the larger right-wing echo chamber.

Public opinion polls taken before the invasion of Ukraine show that Republicans view Vladimir Putin as a better leader than Joe Biden. That is no coincidence. It is publicly known that Putin and Russia's intelligence agencies have been engaged in a long-term influence campaign designed to manipulate (and manage) the Republican Party, its leaders, the right-wing news media and their public.

Putin is an authoritarian and a demagogue. He is anti-human, anti-freedom and anti-democracy. He stands against the future and human progress and pluralism. To many of his admirers in America and the West, he is a leader of "White Christianity." Putin has persecuted and imperiled the LGBTQ community, and is hostile to women's rights and women's equality. He kills and imprisons journalists, and is doing his best to silence free speech.

Most recently, Putin has indicated that criticism of his regime and the war in Ukraine will be viewed a type of thoughtcrime. He is using similar language to the Republican fascists and the larger white right in claiming victimhood and suggesting he has been "canceled" by elites.

Putin's Russia is a plutocracy and a kleptocracy controlled by an oligarchic elite of white men. He uses secret police and other enforcers to terrorize any person or group he deems to be the enemy. Republicans in the U.S., and many of their allies and followers, want to exercise that kind of power in America.

Why would a group of ultra-nationalist Americans celebrate the invasion of a U.S. ally by someone both the left and right have largely understood to be an enemy of freedom?

In fact, though, the U.S. right wing has long cultivated ties with Russia. Some of these are self-evident quid-pro-quo affairs: The "sweeping and systematic" campaigns of election interference authorized by Putin in support of a Trump victory in 2016 and 2020; Trump's attempt to leverage Congressionally allocated aid to Ukraine for political dirt on the Biden family; the confessed Russian agent who infiltrated the National Rifle Association and the National Prayer Breakfast in a bid to develop informal channels of influence on the Republican Party.

More broadly, however, U.S. conservative evangelicals have developed strong symbolic and institutional ties with the Russian Orthodox Church. In recent years, these have dovetailed with white racist fantasies of Russia as an ethnically pure land of traditional religion and gender roles, symbolized by the bare-chested kleptocrat on horseback, Vladimir Putin….

At the much broader level of institutionalized ambitions to "dominion," the Russian partnership has proved invigorating to the American right's overlapping agendas of white supremacy, masculine authority, and anti-democratic Christian authority. If Putin's cooperation with the Moscow Patriarchate is a model for emulation, American theocrats are telling us what they seek here at home. We would be foolish not to take them at their word.

In total, the Republican fascists and the larger "conservative movement" have shown themselves to be Putin's puppets.

To make matters even worse, Putin now imagines himself as a 21st-century version of Joseph Stalin.

To wit. In a speech on Wednesday, Putin denounced "national traitors" who are supposedly undermining the war on Ukraine, saying that "real" Russians will "always be able to distinguish true patriots from scum and traitors." This is the man so many of today's Republicans idolize. That should make clear how dangerous to American democracy and society they truly are.

The form of politics modeled by Vladimir Putin and his Stalinist dreams cannot be precisely replicated in America. As such, it is being massaged and reshaped by the Republican neofascists and their allies to assimilate more easily into American political culture. But it is no exaggeration to suggest that those forces are engaged in a Stalinist revolutionary struggle against American democracy; their tactics, strategies and goals are that extreme.

For many reasons, this moment has brought renewed interest in George Orwell's classic dystopian novel "1984." In a letter written in 1944, a few years before the publication of that book, Orwell reflected upon the dangers of totalitarianism he saw in the U.S. and Britain:

But one must remember that Britain and the USA haven't been really tried, they haven't known defeat or severe suffering, and there are some bad symptoms to balance the good ones. To begin with there is the general indifference to the decay of democracy. Do you realise, for instance, that no one in England under 26 now has a vote and that so far as one can see the great mass of people of that age don't give a damn for this?

Secondly there is the fact that the intellectuals are more totalitarian in outlook than the common people. On the whole the English intelligentsia have opposed Hitler, but only at the price of accepting Stalin. Most of them are perfectly ready for dictatorial methods, secret police, systematic falsification of history etc. so long as they feel that it is on 'our' side. Indeed the statement that we haven't a Fascist movement in England largely means that the young, at this moment, look for their führer elsewhere. One can't be sure that that won't change, nor can one be sure that the common people won't think ten years hence as the intellectuals do now. I hope they won't, I even trust they won't, but if so it will be at the cost of a struggle. If one simply proclaims that all is for the best and doesn't point to the sinister symptoms, one is merely helping to bring totalitarianism nearer.

Orwell's "1984" was meant as a direct rebuttal to both Stalinism and Nazism.

The American people have been repeatedly warned about the dangers represented by the Republican fascists and the Trump movement. The past is prologue — but it does not have to be. The American people can choose to learn the lessons of the past about how democracies succumb to fascism and authoritarianism and act accordingly, or they can continue to insist, against all available evidence, that such evils only bloom elsewhere and cannot possibly happen here.

But democracy must be an active choice. Indifference and passivity are sure to destroy it. What choice will the American people make?

Civilians trapped in Mariupol, Ukraine, under Russian attacks are evacuated in groups under the control of pro-Russian separatists through other cities on March 20, 2022. (photo: Stringer/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

Civilians trapped in Mariupol, Ukraine, under Russian attacks are evacuated in groups under the control of pro-Russian separatists through other cities on March 20, 2022. (photo: Stringer/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

Officials say building destroyed with civilians inside, as further reports emerge of city residents being forcibly taken to Russia

Linda Thomas-Greenfield, America’s ambassador to the UN, said the US had not yet confirmed the allegations, made on Saturday by Mariupol city council and repeated in detail on Sunday by Ukraine’s human rights spokesperson, Lyudmyla Denisova.

“I’ve only heard it. I can’t confirm it,” Thomas-Greenfield told CNN. “But I can say it is disturbing. It is unconscionable for Russia to force Ukrainian citizens into Russia and put them in what will basically be concentration and prisoner camps.”

As the UN said about a quarter of Ukraine’s pre-war population had been displaced by the conflict and Ukrainian authorities accused Moscow of bombing an art school in Mariupol where more than 400 people had taken shelter, Denisova said Russian troops had “kidnapped” residents and taken them to Russia.

“Several thousand Mariupol residents have been deported to Russia,” she said on Telegram. After processing at “filtration camps”, some had been transported to the Russian city of Taganrog, about 60 miles (100km) from Mariupol, and from there sent by rail “to various economically depressed cities in Russia”, she said.

Denisova said Ukrainian citizens had been “issued papers that require them to be in a certain city. They have no right to leave it for at least two years with the obligation to work at the specified place of work. The fate of others remains unknown.”

Russian news agencies have reported that hundreds of people whom Moscow are calling refugees have been taken by bus from Mariupol to Russia. Denisova said the “abductions and forced displacements” violated the Geneva and European human rights conventions and called on the international community to “respond … and increase sanctions against the terrorist state of the Russian Federation”.

Resident Anna Iwashyna, 39, who recently fled Mariupol to to Zaporizhzhia, said: “I don’t know if people are being taken to Russia by force, but I can say for sure nobody is going there willingly.”

Iwashyna said conditions in the city were atrocious. “The entire infrastructure has been destroyed,” she told the Guardian. “There are no shops, no pharmacies, no medical aid, fires are all around the city, there are no firefighters. There’s nowhere to get food.”

Iwashyna said she had seen “dead bodies on the street, with my own eyes. Right by the Maritime University. There was a missile, it was still stuck into an intersection, and there was a dead person on the sidewalk. I could hear planes all night long, they are bombing and bombing and bombing the city, non-stop.”

Days after Russian shells struck a theatre in the city that was also being used as a shelter, local authorities said Mariupol’s G12 art school had been destroyed while women, children and elderly people were inside. There was no immediate word on casualties at the site and no further update on the search for survivors at the theatre.

Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelenskiy, on Sunday described Russia’s siege of the city as “a terror that will be remembered for centuries to come”. Bombarded since the start of the invasion, many of Mariupol’s residents have been without heat, power or water for more than a fortnight. Local authorities have said at least 2,300 have died, some of whom had to be buried in mass graves.

Denisova also accused Russian forces of the murder of 56 elderly people in the town of Kreminna in the Luhansk region after a Russian tank “cynically and purposefully fired at a home for the elderly”. Fifteen survivors were “abducted by the occupiers”, she said, calling the attack “another act of horrific genocide”.

Mariupol authorities said on Sunday that nearly 40,000 residents had managed to leave the city in the previous week, mostly in their own vehicles, despite ongoing air and artillery strikes. Ukraine’s deputy prime minister, Iryna Vereshchuk, said seven safe routes would again be open across the country on Sunday.

In the north-eastern city of Sumy, authorities evacuated 71 orphaned babies through a humanitarian corridor, the regional governor, Dmytro Zhyvytskyy, said on Sunday. He said the orphans, most of whom need constant medical attention, would be taken to an unspecified foreign country.

But in the capital, Kyiv, authorities said at least 20 babies carried by Ukrainian surrogate mothers were being cared for by nurses in a bomb shelter because of constant shelling, with parents unable to travel into the war zone to pick them up.

The head of the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR, said more than a quarter of Ukraine’s pre-war population had fled their homes to escape the Russian onslaught. “Among the responsibilities of those who wage war, everywhere in the world, is the suffering inflicted on civilians who are forced to flee their homes,” Filippo Grandi tweeted.

“The war in Ukraine is so devastating that 10 million have fled either displaced inside the country, or as refugees abroad,” he said. The UN said 3,389,044 Ukrainians had left the country since Russia’s invasion began on 24 February, 90% of them women and children. More than 6.5 million people are internally displaced.

The UN human rights office, OHCHR, said it had confirmed the deaths of 902 civilians in Ukraine since the start of the conflict, adding that most of the casualties were from explosive weapons such as heavy artillery shells, missile and air strikes, OHCHR said. The actual toll will be significantly higher, it said.

As military experts said Russia’s largely stalled ground advance was forcing Moscow to switch to a war of attrition, the Kremlin said on Sunday it had deployed another of its new Kinzhal (Dagger) hypersonic missiles, which travel faster than the speed of sound and can change direction mid-flight.

Ukraine has confirmed that missile attacks took place, on a fuel depot near the southern city of Mykolaiv and an ammunition depot in western Ukraine, but said the missile type had not yet been determined.

Russian shelling also heavily damaged the Azovstal metallurgical plant in Mariupol, one of the largest in Europe, Ukrainian officials said. “The economic losses for Ukraine are immense,” tweeted an MP, Lesia Vasylenko.

The mayor of the encircled northern city of Chernihiv said on Sunday a hospital had been hit in the latest shelling, killing dozens of civilians. “The city is suffering from an absolute humanitarian catastrophe,” Vladislav Atroshenko said.

Details are also emerging of a rocket attack that killed as many as 40 marines in Mykolaiv, a Black Sea port city, on Friday, according to the New York Times, which cited an unnamed Ukrainian military official.

Nevertheless, the Ukrainian presidential adviser Oleksiy Arestovych said on Sunday that the frontlines between Ukrainian and Russian forces were “practically frozen” as Russia did not have enough combat strength to advance further. “[Over the past day] there were practically no rocket strikes on [Ukrainian] cities,” Arestovych added.

Britain’s defence ministry said Russian forces had made “limited progress in capturing cities” but had instead “increased its indiscriminate shelling of urban areas, resulting in widespread destruction and large numbers of civilian casualties”.

It warned that Russia would “continue to use its heavy firepower to support assaults on urban areas as it looks to limit its own already considerable losses, at the cost of further civilian casualties.”

David Petraeus, the former US military commander and CIA chief, said it was “absolutely confirmed” that Ukrainian forces had killed at least four Russian generals. The Russian forces’ command-and-control structure had “broken down”, he said. “Their comms have been jammed by the Ukrainians. They’re literally stealing cell phones from Ukrainian civilians to communicate among each other.”

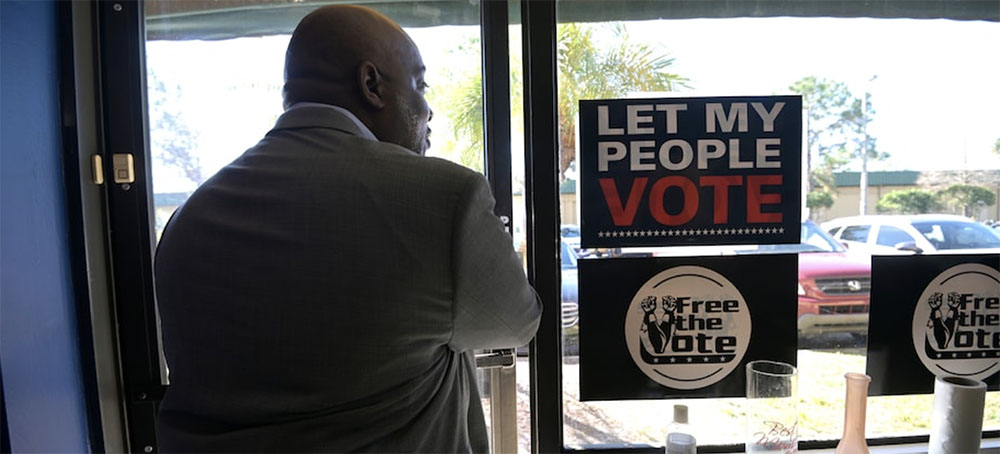

Desmond Meade, executive director of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, powers his activism with his own story of turning his life around after prison. (photo: Phelan M. Ebenhack/WP)

Desmond Meade, executive director of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, powers his activism with his own story of turning his life around after prison. (photo: Phelan M. Ebenhack/WP)

As his national profile increases, Desmond Meade pushes for jobs, housing and dignity for formerly incarcerated people like himself

The event’s pomp, to say nothing of the size of the gift, was a world removed from his lowest days fresh out of prison. Back then, he was jobless, in drug rehab and thinking a lot about death, including his own.

“I didn’t want to be that person who died and nobody came to the funeral or even knew that he died,” he would later write in a memoir.

There’s no chance of such anonymity now. Whether on the Miami Dolphins’ home field, at a rally outside the Capitol in Tallahassee or on college campuses across the country, the burly, 54-year-old Meade is visible and known. More than anyone else, he is the face of voting rights activism in Florida, the man who spearheaded a state constitutional amendment to give people like him — people with felony convictions — the right to cast a ballot.

That work continues, as urgent as ever because of moves in Florida and in other states that have limited when and how people can vote, how they can register and whether they even can be given water while they wait in line at the polls.

But as his national profile has risen, Meade has expanded his message beyond voting rights to address the many obstacles formerly incarcerated people face. Voting is at the heart of making them whole, Meade says. It’s just the start, though.

“Our mission … is much greater than that,” he told an audience in Austin this month during a SXSW Conference discussion on rebuilding these lives. “We believe that just like a chain is only as strong as its weakest link, our society, our country, can only be as great as those who have been most weakened by systems of oppression and discrimination.”

For years, he has studiously avoided making partisan statements, no matter how he was challenged publicly. That could soon change. People ask him all the time if he’ll run for office, and Meade no longer is brushing off the prospect with a laugh and shake of his head.

“I would consider it,” he said in a recent interview. “We need people in office who are more concerned about the needs of the people, all the people of Florida, than the needs of their political party.”

Meade is integrally linked to the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, which he has led for more than a decade. The nonprofit’s greatest success was the overwhelming passage of Amendment 4, the initiative that represented the nation’s largest expansion of voting rights since the civil rights era. More than 1.4 million Floridians who had served time regained the right to vote.

After the amendment’s impact was tempered by “implementation legislation” pushed by Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) and Republican lawmakers — requiring individuals to first pay off any fines and fees connected to their convictions — Meade and the coalition were able to raise millions of dollars to assist 40,000 “returning citizens” in settling those debts. Among the donors: singer John Legend and basketball superstar LeBron James.

The accolades haven’t stopped. In 2020, the Ford Foundation named Meade one of its first Global Fellows. In September, the MacArthur Foundation awarded him a $625,000 “genius grant,” as the honor is commonly known, saying “his bold vision for empowering returning citizens through mobilization and education serves as a blueprint for other states to follow.”

Yet for all the praise and prominence, Meade remains a man living with drug and battery convictions — reflecting the troubled years after he was dishonorably discharged from the Army but before he was released from prison and transformed his life through college and law school. A felony record like his is often a barrier that can make it difficult or even impossible to find a job, start a business or be approved for a loan. Meade, for one, is still having trouble getting a mortgage.

“I may have the financial wherewithal to get a house,” he noted, “but even that is not good enough, you know?”

He maintains a frenetic schedule, often away from his family in Orlando as he crisscrosses both the state and nation to speak on panels, at churches, to inmates and in corporate boardrooms. He and friend Neil Volz, the coalition’s deputy director, host a podcast called “Our Voice.” Their biweekly conversations typically feature guests with lives once caught up in the criminal justice system.

The coalition’s rally during the 2022 legislative session drew hundreds of supporters to urge passage of bills that would lower hurdles to employment and housing for people with felony records. One measure, dubbed the Desmond Meade Bill, would block entities that contract with the state corrections department for prison labor from refusing to hire individuals after they are released. It died in committee.

Meade was among the scores of men and women who jubilantly registered to vote on Jan. 8, 2019, the day that the constitutional amendment took effect for formerly incarcerated Floridians. He paid off his fines and fees and, on Nov. 3, 2020, voted for the first time since leaving prison 15 years earlier.

Not until October 2021, however, did the state Clemency Board restore all his civil rights. (His initial request several months earlier had been denied, with DeSantis questioning him sharply.) He at last can sit for the Florida Bar. And he now can run for office.

He is still trying to keep the issues he cares about nonpartisan, the approach he says made the amendment campaign so successful: “Everyone knows someone who deserves a second chance.”

Such evenhandedness is why former Republican lawmaker J.W. Grant talks of the “fantastic working relationship” he had with Meade, even while pushing the measure that made voter registration contingent on repayment of prison fines and fees. “He’s somebody that I have a ton of respect for,” Grant said last month.

At the same time, it draws the rare criticism of Meade, mostly from individuals strongly aligned with his work.

Roni Bennett, co-founder and executive director of South Florida People of Color, says she understands why some people are frustrated with him but thinks he is wise to stay above the partisan fray.

“He’s able to maintain his credibility that way,” Bennett said. “It’s about human rights, not about Republicans or Democrats. There’s issues on both sides with that.”

Meade, who listed no party affiliation on his voter registration, is getting a little closer to crossing the line between activism and politics. While still not naming names, his language is more direct and pointed.

“Right now, democracy is burning. The country is burning,” he told students at Florida Memorial University in December. He looked exhausted, yet he became increasingly energized as talked over the next hour, answering questions about how to organize for a cause and what to do when powerful people stand in the way of change.

In the end, Meade turned to hope — just as his own journey once did. “I do believe that we, as a community, will emerge from the ashes,” he said, “and create the type of democracy, the type of world … where we would be respecting people, respecting their humanity and be willing to treat everyone with dignity.”

David Cross at the 2019 Tribeca Film Festival in New York City. (photo: Roy Rochlin/Getty Images/Tribeca Film Festival)

David Cross at the 2019 Tribeca Film Festival in New York City. (photo: Roy Rochlin/Getty Images/Tribeca Film Festival)

David Cross on political humor, how standup has changed, and why complaints about cancellation are “bullshit.”

We want them to be funny. We want them to turn outrage into laughter. We want them to look at the absurdity of the world and reflect back on it in some kind of cathartic way. We also want them to “punch up,” to mock the powerful. And then sometimes we just want them to get us to stop thinking and laugh.

The role of comedy is always an open question, but it seems to pop up a lot these days. Comics like Michael Che and Dave Chappelle have been in the news, for different reasons, and it’s usually about free speech or “cancel culture.”

Most of these debates are boring and circular, but I am interested in how comics engage with the world, and what they decide to make fun of and why. So I reached out to David Cross for the latest episode of Vox Conversations. You probably know him from his TV work. He was the star and co-creator of HBO’s Mr. Show and he famously played Tobias Funke on the cult hit Arrested Development. But he’s also a long-time standup comedian and has a new special out, called I’m From the Future.

We talk about the evolution of his comedy, why he doesn’t think of himself as a political comedian, and what he thinks about “cancel culture” and the idea of “selling out.”

Below is an excerpt, edited for length and clarity. As always, there’s much more in the full podcast, so subscribe to Vox Conversations on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Sean Illing

This is one of those moments where I feel like everyone’s pissed off about everything, and you definitely seem as pissed off as the rest of us in this special. Did you feel like you had an unusual amount of rage bottled up for this one?

David Cross

I’d say it was normal rage. It’s always there. The question is always what am I directing it toward? But everything is tempered now because I’m a dad and so I try to infuse some sort of optimism in all the anger and negativity and cynicism because I just have to for my kid’s sake.

But I don’t know if it’s rage, exactly. It’s mostly incredulousness. It’s just the frustration of looking at a world that makes no sense. And you’re twisting everything to make it make sense to you and it just doesn’t on so many levels. And that’s part of where the anger stems from, I guess. We could have a truly great society, but you guys keep fucking it up.

Sean Illing

My favorite bit in the show is where you’re pretending to stand in front of all these imaginary kids and you’re telling them all the ridiculous shit they’ll organize their political identities around when they’re older, all the inane stuff they’ll be pissed off about.

David Cross

Yeah, that’s where the title of the show comes from, I’m From the Future. That’s a good example of a bit where I had a very vague idea of doing something about people who scream at other people in a store for speaking Spanish. They overhear them speaking Spanish and they scream at them. I worked on that for months and I could not find the angle at all, and it just wasn’t working. It sounded preachy.

And then it occurred to me, “Oh, what if they were 5 or 6 years old and you showed them the person that they were going to become?” The kids would be like, “No, I don’t want to do that.” So that’s where that whole thing came from.

Sean Illing

It’s funny, when I started preparing for this interview, I thought about the distinction between a political comic and a comic who just talks about politics, and I said to myself, “Of course, Cross is a political comic!” Then I heard you say that you’re absolutely not a political comic, and naturally I felt like a jackass.

David Cross

Well, it’s not dumb. I’ll let you finish your thought, but I’ll just say that I can point to different comedians that are political comedians, and the bulk of their material, let’s say more than 75 percent of it, deals directly with politics or cultural wedge issues, which might feel like it’s political, and mine doesn’t.

I truly understand why sometimes it feels like more of the set is political, and my last few shows have been a little weightier and not as light and breezy as some of the others. I still have some really stupid dad puns, some bad jokes, and some silly impressions and absurdist stuff in there, but when you’re doing material about Trump or Obama or even going all the way back to Bush, it feels like it has more weight to it.

Sean Illing

I don’t want to dump on any other comics, but there are some who I’m not sure they’d have anything to talk about if they weren’t talking about politics, and I definitely don’t think of you that way. There are the late-night-style comics who use politics as fodder, but they’re not really saying anything — it’s all discardable blooper stuff. And then there are comics who obviously are funny and tell jokes but there’s a moral clarity behind it, and I’ve always thought of you in that way, even though there’s plenty of silliness in your material.

David Cross

I didn’t take it as an insult or anything, and I’m not bothered by the idea that I’m pigeonholed that way. It’s just one of those things where I feel like I have to clarify things because I definitely talk about politics and I definitely have a strong point of view. But I still don’t think of myself as a “political comedian.”

Sean Illing

Do you talk about politics because you feel like you have to?

David Cross

Not at all. I find that a little pretentious for my taste, the idea that I have a moral obligation to do this thing. And it also implies that I have some sort of galaxy brain that I have to share with people so that they’re enlightened. This is the kind of stuff I’d be saying over a few pints at a bar with friends. And when these shows develop, I start at small rooms, like 99-seat rooms in a basement in a club in Brooklyn. So they are my friends. They’re all right there in front of me. That’s where this stuff develops.

Sean Illing

I guess it’s the ideological comics that don’t really work for me. I think you can be a funny political comedian, but I’m not sure you can be a funny ideologue. I think you stop being funny when you stop telling the truth and it’s hard to tell the truth and serve an ideological audience at the same time.

David Cross

I think you’ve hit on something, whether intentional or not, and it has to do with the polarization and the capitalization and the exploitation of our audiences. And I think you see a lot more people doing that kind of thing. They’re speaking to a consumer base and they’re looking at it like that. It used to be, back in the late ’80s or the early ’90s, that there was a kind of stigma around the comics who were just doing standup so that they could get on a sitcom. That was a real thing. Other comics would recognize it immediately.

And now there are people who are trying to backdoor into standup via other avenues so you can get a podcast or something because that’s where the money is. It’s a 180 from where it used to be. People are getting into standup now for the money. So you get a lot of people with a foot in both worlds that are using standup specifically to build their base, to build their revenue-streaming possibilities.

Sean Illing

It really does feel like comedy has changed so much over the last 20 years, going back to the Bush era and up until today. You put out this amazing comedy album shortly after 9/11 and it was one of the first pieces of popular art in those early days that anticipated the horrors of that era, and it seems like things have just gotten steadily darker since.

David Cross

It’s both a continuation and a heightening of more of the same thing. But I look back, I haven’t listened to that album, Shut Up, You Fucking Baby!, in quite a while. But that’s a younger guy. That’s a guy who didn’t know that things were going to remain awful and actually get worse and worse and worse. That was a guy in his 30s who has the world in front of him and who kind of knew what it was going to be like.

I had just moved to New York, maybe eight months prior to that, after being in LA for nine years, where every minute was spent like, “I got to get out of here.” And all the material that has developed subsequently is just a standup getting older and more outraged. But as I said earlier, I’ve got to filter things and be as optimistic as I can because of my daughter and her friends. I’m around kids a lot more now. I wasn’t around kids a lot, certainly not back then. And so it’s interesting because I’m just a different person now. I’m the same standup, but my experiences are different. My world is different.

Sean Illing

Have you noticed a shift in the audience over the years?

David Cross

Yeah, they’re older! They used to be in their 20s and 30s, now they’re in their 50s. What’s going on?

Sean Illing

I just turned 40, man, I think I’m one of the olds now. But seriously, do you feel like things have changed on the demand side in terms of where the lines are or what people will laugh at? There’s so much noise about “cancel culture” in comedy and I find most of it boring and I assume comics have always adapted with the times. Do you feel like the pace of adaptation is quicker now than maybe it was when you first started?

David Cross

I don’t think so. Nobody’s getting arrested.

Sean Illing

I don’t actually know of any comedians who’ve been “canceled.”

David Cross

No, they haven’t been. That’s bullshit. If we think about it in less histrionic terminology, there’s certainly a reality now where if you say something and if you don’t apologize and you double down and then you triple down, then you’re going to have a segment of your fan base react. And you’re going to have lots of people who didn’t care about you in the first place doing that whole performative outrage thing. They’re just showing their weight as consumers. It’s not that different from people saying, “We’re going to boycott this thing because they advertise on Tucker Carlson and I don’t like what he said.”

People have every right to do that. We live in a capitalist society, and that’s how it works. So people aren’t getting canceled. They’re either getting their tickets refunded or trying to shame people from going to see somebody’s live show. Who knows what kind of effect that’ll have? Probably not very much.

I don’t know anybody that’s not able to do standup anymore because they said something offensive. Obviously, there are people who have done some egregious things that have nothing to do with their comedy and lots of people have made their feelings known about that. But if you say something extremely homophobic or misogynist or racist or anti-Semitic that cannot be defended and people go, “Hey that person’s appearing on Apple TV or Netflix or whatever. Let’s boycott the sponsors,” then that’s their right. But nobody’s not able to do standup. Maybe you can’t sell out Madison Square Garden eight shows in a row, but you’re still going to get to do standup.

A graveyard outside the shuttered Haywood County Community Hospital in Brownsville, Tenn. on Feb. 7, 2022. (photo: Rory Doyle/Politico)

A graveyard outside the shuttered Haywood County Community Hospital in Brownsville, Tenn. on Feb. 7, 2022. (photo: Rory Doyle/Politico)

The state is a poster child for how rural areas are suffering disproportionately amid the pandemic in the worst public health crisis in a century.

The rural county in the Tennessee delta, near the Mississippi River, had its health care system ground down in the years leading up to the pandemic: Ever since the 84-year-old Haywood County Community Hospital closed its doors in 2014, the numbers of doctors and other health care professionals dwindled. Residents who once were on a first-name basis with their care professionals were left to book appointments at facilities miles from where they’d raised their families and grown older.

Haywood County — with its flat land and fertile soil, generations of proud farmers but low per capita income of about $22,000 — is something of a poster child for rural America. It’s also a prime example of the decline of rural health care — and how rural areas are suffering disproportionately in the worst public health crisis in a century.

Some of the biggest disparities in the Covid-19 crisis aren’t just among red states and blue states, or Black, white and Latino populations; they’re between rural and urban communities.

Of the 50 counties with the highest Covid deaths per capita, 24 are within 40 miles of a hospital that has closed, according to a POLITICO analysis in late January. Nearly all 50 counties were in rural areas. Rural hospital closures have been accelerating, with 181 since 2005 — and over half of those happening since 2015, according to data from the University of North Carolina. But that may be just the beginning. Over 450 rural hospitals are at risk of closure, according to an analysis by the Chartis Group, one of the nation’s largest independent health care advisory firms.

Those closures caused shortages of beds, ventilators and medical staff, and left behind patients with high and rising levels of diabetes and hypertension. Now, those communities often also have high rates of unvaccinated people — and that may well be related: In the communities where health resources disappear, so too does confidence in the medical system. Trusted sources of information go elsewhere.

The closure of Haywood County Community Hospital in Brownsville left local resident Jack Pettigrew with a 35-minute trip to the nearest emergency room, thinking Covid-19 was going to kill him.

“Honest to goodness, when we were backing out of the driveway that day, I had the strangest feeling that I wouldn’t be coming home,” he said, recalling how he worried about the long trek to the emergency room.

Pettigrew, who retired in 2020 after practicing medicine in Brownsville for 37 years, had spent his career treating a population that watched Haywood County Community Hospital shrink over the years until it finally closed entirely in 2014 — like six others in western Tennessee that closed in the same timeframe. Stories of people dying because they couldn’t get care fast enough started popping up everywhere after the closure. Underlying conditions became a bigger problem.

“We would constantly make appointments for people for mammograms or diagnostic tests or whatever, and, you know, two weeks later, we’d get a note that the patient never showed,” recalled Pettigrew. “And you never know whether you missed a breast cancer or whatever because they just didn’t go.”

Then the pandemic hit.

“In the case of Covid, we faced some of the same challenges,” Pettigrew said. “In our rural area, there are a lot of people that don’t even have transportation, so they rely on somebody else to take them places, bring them back. If they don’t have something like that, a lot of times, they just kind of ignore their situation, and it gets worse and worse and worse until they’ve gone beyond the point of return. And I suspect there were a lot of people that got Covid that didn’t do anything about it until they got extremely sick and then, unfortunately, a lot of them didn’t pull through it.”

Haywood County, tinted blue in most elections, has a middling vaccination rate by national standards, but it was still higher than surrounding counties. Nonetheless, the number of people who died of Covid in Haywood County is in the 97th percentile nationally — well above many nearby counties. Overall, rural communities have seen almost twice as many deaths per capita as metropolitan ones.

Pettigrew survived his own bout with Covid-19, after a harrowing experience at the nearest hospital, in Jackson, Tenn., where doctors and nurses were frantically battling Covid surges that led steady streams of patients from communities across western Tennessee that had lost their own hospitals.

Pettigrew’s sense of dread deepened as he heard codes called over the intercom, knowing many of them meant people were dying all around him. He texted his son, asking him to call when he was alone. Pettigrew didn’t want his wife to hear him tell his son about important documents and safe combinations, in case he died soon.

After a day in the ER, he was finally moved to another room, where he would spend five days before returning home.

His outcome was better than many — not only because he survived Covid, but because he could get to a hospital, because he survived the trip there, because a bed was open at all. His wife, with Covid-19 and double pneumonia, would be turned away from the hospital. He wouldn’t even try to bring his dad, who was in his 90s and would eventually die from the virus.

“We knew they basically weren’t going to keep him or do much for him because they were basically hospitalizing people that were in an age group that would possibly survive and then be back into a normal life,” Pettigrew said.

In rural hospitals in western Tennessee, people would wait days in emergency room hallways, hoping for a bed to open up — even if the bed were on the other side of the state. Nurses would have to hand-pump air into patients for hours with manual ventilators because of shortages. Other hospitals in West Tennessee would connect two patients to a single ventilator while their owner, Braden Health, tried to buy ventilators from a recently closed field hospital — but they had already been sold to another state. One hospital in the region, Houston County Community Hospital, moved 50 patients into a nearby gymnasium.

“It’s one of those ripple things, it’s touched most everybody,” Pettigrew said. “Most everybody knows one of those stories, and it’s really sad.”

Warnings go unheeded

Washington ignored years of signals that the South’s health care system was crumbling. When the pandemic began, it was too late to rebuild.

The rate of rural closures accelerated over the last decade, with 2020 setting a record — even as demand for their hospital services was growing to an all-time high.

In the last decade, 138 rural hospitals have either partially or completely closed, according to data from the University of North Carolina. Well over three times that many — 453 — are at risk of closure, according to a 2020 analysis from the Chartis Center for Rural Health. Of that group, 216 are at a high risk of closure.

Other analyses are even more pessimistic. Over 500 rural hospitals are at immediate risk of closure, according to a 2022 model from the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform.

In Tennessee, both models show, over half of remaining rural hospitals are at risk of closure — just like in other states across the South and Midwest.

Tennessee — and the entire Southeast — was nearing a crisis well before the pandemic, with hospitals operating above surge capacity even before the first infections were reported.

“We were down to a bare-bones number of hospital beds to support communities, and there was almost no slack in the system,” said Stephan Russ, the associate chief of staff at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

“I don’t think many people realize how close to the edge we were,” he added.

Vanderbilt’s hospital was already getting calls from states hours away in 2018 and 2019. One of those calls, which Russ experienced himself as an emergency physician, came in 2018. A rural hospital in southern Alabama called Vanderbilt asking if they had a bed for a patient in his late 40s who required emergency surgery for a twisted intestine. The hospital had recently lost its only surgeon, so the relatively straightforward procedure had to be done elsewhere. They had called nearby hospitals, all of which were full.

When the patient arrived in Nashville, the swelling in his abdomen had cut off circulation to his legs. He was immediately sent to the operating room, where he died on the table.

“We have a residency program at Guyana, on the coast of South America,” Russ said. “These are the types of things that [I see] when I go down and work in Guyana. We see this for the Amerindian population that are coming out of the villages and need a canoe to get, you know, to a hospital. This isn’t the type of thing that we’re used to seeing in the United States.”

Tennessee lost over 1,200 staffed hospital beds between 2010 and 2020 despite a population that grew by over half a million, according to the American Hospital Directory and census data. Mississippi, with the most Covid-19 deaths per capita, lost over 1,100 beds over that decade. Alabama, second only to Mississippi in per-capita deaths from the virus, lost over 800.

Those beds would have been critical to statewide systems under the stress of the pandemic, according to doctors and hospital officials. Smaller hospitals often send their most serious patients to larger hospitals, usually in urban areas, for higher levels of specialized care. But large hospitals also send patients to smaller hospitals when they can get the same level of care — especially if staffed beds are in short supply. Without rural hospitals, urban centers were swamped with patients, making transfers more difficult and higher levels of care less accessible.

In Florida, where there have been fewer closures, Tallahassee Memorial Health was able to alleviate the crowding caused by Covid-19 by training staff at smaller hospitals to treat cases that would usually require a higher level of care. Nearby rural hospitals proved to be the key to treating patients through the pandemic.

“We need every single one of them,” Lauren Faison-Clark, administrator for regional development, population health and telemedicine at Tallahassee Memorial HealthCare, said of rural hospitals. “We don’t want everybody coming to Tallahassee for health care.”

If the region had seen significant closures leading up to 2020, Faison-Clark said, Tallahassee hospitals would have likely seen overflowing emergency rooms with beds in hallways and worse outcomes for many patients.

In Mississippi, where officials told drivers to be cautious on the road because of the extreme shortage of beds, closures did lead to a breakdown in levels of care.

“The entire system clogged up,” said Claude Brunson, executive director of the Mississippi State Medical Association. “Without a doubt, there are some patients who died because we did get bottlenecked and couldn’t establish a very good flow of care across the system — because we had lost the numbers of beds that we truly did need.”

In central Tennessee, transfers became such a critical issue that hospitals, including Vanderbilt’s, created a transfer coordination center to maximize the efficiency of the system. But not every state or region has even that advantage.

“We have gotten calls all summer long from Georgia, Alabama, Kentucky, Virginia, West Virginia,” Russ said of Vanderbilt. “Oftentimes, these are small rural hospitals that have called over 50 big hospitals in the Southeast trying to get care for their patient and have been unsuccessful.”

No open beds

In Brownsville, Andrea Bond Johnson — who locally operates an insurance company and ran for the state house — saw the limits of the hospital system first-hand when her parents were ill and waiting for results from their Covid tests.

Her 86-year-old mother was getting weaker, having to take breaks to rest when walking between the bedroom and the kitchen.

“Annie, come here,” her mom yelled from her bedroom. “Something is wrong with my heart.”

Fearing a heart attack, Johnson called 911. Fortunately, they lived near the EMS facility in town. Even more important — and not always the case — there was an ambulance available.

When the hospital closed, Haywood County had been obliged to purchase new ambulances to carry patients over longer distances. Even with more crews and vehicles, call times were still much longer.

A crew arrived about 15 minutes after Johnson’s call, moving her mother to the back of the ambulance. But the paramedics didn’t rush her to the hospital. Instead, they began examining her as if she were in the emergency room already.

Johnson saw her mother slumped over while the paramedics worked to get readings.

“Honestly, it looked like my mom had passed away,” Johnson said.

Doctors in Brownsville are acutely aware of the “golden hour” of care, Pettigrew said. The care in the first hour of severe illness can often determine the outcome. Spending more than half of that hour driving to a hospital can prove to be fatal.

Johnson looked closer at her mother and saw faint breathing. The paramedics continued working for quite a while, Johnson said, before determining that her mother needed to be airlifted to Jackson’s hospital.

Johnson drove to the hospital, beating the helicopter. Her mother was held longer in the ambulance to try to stabilize her as much as possible before the trip.

“Really, our emergency room is in the back of an ambulance,” Johnson said, echoing a sentiment — and sometimes verbatim quote — from people across the South who’ve lost their hospitals.

Unable to get into the hospital because of Covid protocols, Johnson returned home to care for her 87-year-old father. It wasn’t long before his breathing became irregular. She called an ambulance again, which took him to Jackson’s hospital.

After he arrived — unable to walk, and with Parkinson’s Disease along with Covid-related pneumonia — Johnson got a call from the hospital. They said her dad had to go home.

“[Haywood County residents] filled up the Jackson hospital until they said, ‘Listen, we have no more beds. I’m sorry, we just cannot take care of you,’” she said.

Her father was sent to a skilled nursing facility in Dyersburg, a 50-minute drive away, where his wife would eventually join him. They stayed together in a Covid wing of that facility for weeks, celebrating their 59th wedding anniversary there.

Johnson’s mother got worse, having to go back to a hospital — but Jackson’s was out of space. She went to the hospital in Dyersburg, but also short on beds, she had to stay in the emergency room overnight before she could get a room. After hours of Johnson driving and weeks of her parents resting, her mother and father recovered.

“It would have made a tremendous difference if the hospital had been open,” she said. “We were unable to take care of ourselves in our own community.”

Losing trust in the system

Lisa Piercey, the health commissioner for the Tennessee Department of Health, was regularly checking metrics on how the state’s 95 counties were performing through the pandemic. Urban areas were regularly the best performers — with high vaccination levels and low Covid-19 mortality rates — but so were rural areas that had open hospitals and clinics.

“I would say, ‘Oh my goodness, why is this little rural county on this list of high vaccination rates?’” she said. Trust in the system would turn out to be a key to success.

“The population there didn’t necessarily put that much credibility in what I say or what the governor had to say, but if their local hospital and their local doctors did that ... they would go there, and their vaccination rates were higher,” Piercey said.

Large hospitals across the South, trying to reach the unvaccinated, would partner with rural hospitals to convince more people to get the shot. Without smaller facilities with roots in a community, however, vaccine hesitancy gained a foothold.

Hospital closures have led to fewer vaccinations of all kinds for some communities — not just shots for Covid-19. In the years after Haywood County’s hospital closed, flu vaccinations dropped almost 10 percent in the county, according to data from the University of Wisconsin.

“It’s almost like they’ve been forgotten,” said David Sudduth, executive director of Healthy Me-Healthy SC, a program to improve health care for people in rural South Carolina.

That separation was a key contributor to vaccine hesitancy in some communities, the Mississippi State Medical Association found in a local study.

“The number-one priority is [the unvaccinated] wanted to get information from someone they trusted, and the number-one trusted person for those folks and their families is their primary care physician,” Brunson, president of the MSMA, said. “The primary care physicians would be in the rural hospital there ... and probably has a clinic outside that’s closely associated with that hospital. And so by not having the rural hospital, you lose that connection between that community and the health care professional that would have been there.”

Hospital closures also led to more underlying conditions in communities, doctors and health care experts across the South said — and those illnesses compounded Covid’s danger. Haywood County’s hospital closure was followed by a spike in chronic illness and underlying conditions. The premature death rate had ticked up to its highest level in well over a decade in the years after the closure. The rate of obesity had risen to its highest recorded level, as did deaths from heart diseases. Brownsville’s city government started programs trying to get underlying conditions under control, promoting healthier diets and exercise.

The same was true in rural areas across the South.

“Any of us who practice medicine — we know that if we talked to a patient that we’ve been taking care of them and their family for a long period of time, they’ll do something because they trust us,” said Mississippi’s Brunson.

‘A moment of action’

Most rural hospitals close because of financial trouble, and many of them relied largely on government reimbursements — Medicare and Medicaid — to survive. If the government or private insurance reimbursements don’t cover the cost of a procedure, it can lead to losses and eventual closures. Hospitals that aren’t part of a large system have almost no bargaining power with private insurers, they say, which can exclude the facility from their network entirely.

And without larger systems, which can both bargain for better pricing and also have departments dedicated to filing for maximum reimbursements, many rural centers find it increasingly hard to survive.

That’s why the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has implemented payment structures that are supposed to aid rural hospitals — including a coming payment structure intended to benefit rural emergency rooms. Some states put their own funding into rural hospitals to stop the financial bleeding, others hired consultants and created task forces to find out what was going wrong.

But the solutions that had been proposed up to 2020 had either had limited impact or never passed at all.

When the pandemic hit, conversations about those solutions, once mostly out of the news cycle, became urgent. Constituent calls started pouring in.

“One of the big issues we had when Covid first started was people couldn’t get an ambulance to come to their house, so they were just dying,” said a legislative aide working for a member of Congress from a rural state.

All of the staff shortages, sustained losses in revenue and declining access to health care seemed to come to a head when deaths from the pandemic started adding up.

“It’s kind of the perfect storm,” the aide said. “We were shit out of luck.”

Rural doctors had been sounding the alarm for decades, trying to get state and federal action. Pettigrew, from his office in Haywood County, had worked to get the attention of legislators in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

“I tried my best to get someone from Washington to send down somebody — a representative — and just spend a week in my clinic before they made decisions on how they wanted to change the health care delivery,” he said. “Because so many people just have no idea what it’s really like in areas like this.”

These efforts continued for years, even with large hospitals joining the effort.

“I was meeting with people from Deloitte and others, trying to get attention to this,” Russ, asssociate chief of staff at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, said. “In 2018, there were days where, at least from a transfer perspective, it didn’t appear that we had more than a handful of open ICU beds in the entire Southeast.”

Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine) has long been concerned about rural hospital closures, but it was only after systemwide failures that the problem could begin to be seriously addressed, she said.

“This is a moment of action, and I think if you look at the flurry of activity prompted by the pandemic, that that becomes evident,” she told POLITICO.

Updates to health requirements that she and other lawmakers have been working on for a decade, for instance, are now finally law after the pandemic pushed Congress to act. The Paycheck Protection Program and Provider Relief Fund offered most rural facilities more government support than they had ever seen. Broadband expansion and updated telehealth regulations will offer new opportunities for care in many areas, and several bills have been introduced to boost the workforce in rural health care. Behavioral health and addiction treatment have also come into the spotlight, with new measures to bring care to rural Americans.

“At least the pandemic has allowed us to make some changes — whether it’s reimbursement or telemedicine or allowing others than physicians to prescribe home health care — that we had not been successful in getting through before,” Collins said.

Emergency federal funding for hospitals during the pandemic meant rural closures fell to an all-time low in 2021 — after being at an all-time high in 2020, with 19 closures in a single year. But that money will eventually run out, leaving rural providers to navigate the patchwork of adjustments state and federal lawmakers have made to try to stop the financial losses.

“We always had a Band-Aid on [the rural health care crisis],” one aide who works on health care legislation said.

There are some policies aimed at tackling the closures in a new way. CMS is working to create a payment system that would incentivize hospitals facing closure to at least continue offering emergency services.

A few months ago, Collins visited the Maine Medical Center in Portland, where the staff and facilities were overwhelmed. In the Covid wing, many patients would not survive, she said. Most of them were from rural Maine, far beyond the reaches of Portland.

“You see the patients literally in the hallways — and I saw that even at Maine Medical Center, but it’s more prevalent at the rural hospitals where all the ICU beds are filled,” Collins said. “There was one rural hospital that was putting Covid patients in the areas that were for obstetrics, and they were just hoping that there wouldn’t be any moms coming in to give birth.”

Beyond the pandemic

Older folks in Brownsville remember when Haywood Community Hospital was a model of quality. The hospital had at one time attracted specialists from Memphis, who would perform delicate surgeries in Brownsville. Other rural hospitals in West Tennessee also had specialized care, from orthopedic surgery to coronary care units.

Even as such specialized care was pared down over the years, the hospital’s essential services saved lives and supported the health of the community. In 2013, exactly one year before the hospital closed, a baby in Brownsville had a severe allergic reaction — Clayton Pinner was rushed to the local hospital and eventually transported to Memphis.

“The doctors just kept saying if we had not gotten in there so quickly, he certainly would not have lived,” said Natalie Pinner, Clayton’s mother.

But even while doctors and nurses were saving people like Pinner, the hospital was losing money — a good year was when it was only $300,000 in the red, said Michael Banks, who was on the community’s advisory board for the hospital before it closed — and instrumental in its reopening.

“We struggled, I mean we were turning into your typical Delta town,” he said.

After the closure, Haywood County didn’t have a working emergency room to stabilize patients before moving them to larger facilities, much less any specialists. A resident had a heart attack soon after the closure, and without facilities to get him immediate treatment, he died.

The hospital was there for the Pinners in 2013, but it was not in 2018, when Clayton was diagnosed with a rare form of leukemia. During the first wave of Covid, doctors at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital were concerned there wouldn’t be enough hospital beds to go around for at-risk children in rural areas, like Clayton.

“With all of the hospital closures in the surrounding counties, the ER that we had been sent to in Jackson was just overworked,” Pinner said.

Pinner and her husband checked the number of hospital beds available in West Tennessee every day, and deciding it was too dangerous to be far from St. Jude, they moved to Memphis.

When the pandemic is over, the impacts of hospital closures and a weakened health care infrastructure will remain. Through the pandemic, people have become even less connected to their doctors, underlying conditions have gone untreated, and the opioid epidemic has accelerated.

Even if hospitals had no more Covid cases to take on, many rural states would have a hard time keeping up with demand.

Braden Health, the company reopening the Haywood County Community Hospital, is betting that many — if not most — of these closures didn’t have to happen at all. They have begun opening hospitals in the South — including a few in western Tennessee — with the belief that they could be financially sustainable.

Kyle Kopec, the director of government affairs for the company, said that some of these hospitals could have been kept open through the pandemic if they had the precise knowledge of what is sustainable in a rural setting — and if the American reimbursement system took smaller, rural hospitals into account. Even though some policies are changing, experts and hospital operators say it’s likely too little, too late.

Braden Health, even while opening Haywood County’s hospital and others, estimates the worst is yet to come for rural health care. More than a decade’s worth of closures could be possible in the next few years, some projections warn.

“Your hospital is essentially an oil tanker in the middle of the ocean, and it’s on fire. It’s sinking and has no lifeboats, and if you don’t figure it out, you’re going down with the ship,” Kopec said.

The reopening of the Haywood County Community Hospital in Brownsville seemed far-fetched amid the sea of closures — even to the town’s mayor, Bill Rawls.

“It was just a never-ending, bottomless pit of issues that put people’s lives in jeopardy. At the end of that pit was somebody’s life,” he said. “It’s just a blessing from God, Dr. Braden and his group.”

But for now, Haywood County continues to hold out hope that a new hospital — slated to fully reopen this summer, with limited services returning sooner — could change the outlook on their health. Braden Health and local doctors hope to reestablish a deeper connection between the community and health care workers, and many residents are more excited about the acute care, mental health care and diagnostics coming to them than the $5.6 billion Ford plant being built a few minutes away.

“We need quality health care to be available to everybody. It should be a right, not a privilege. And we just saw that right taken from us,” Rawls said. “People didn’t realize how much they needed until it was gone. It’s like you don’t miss the water until the well runs dry.”

Afghan refugees. (photo: Reuters)

Afghan refugees. (photo: Reuters)

Since the Taliban took control of Afghanistan last year, the country has faced a humanitarian crisis with half of the population experiencing acute hunger. The U.N. Refugee Agency says 3.4 million Afghans are internally displaced due to conflict, the country’s healthcare system is experiencing severe shortages, and workers in schools and hospitals are going without salaries while facing rising food and energy costs — which many attribute to economic restrictions the Biden administration implemented. We look at the unfolding crisis in Afghanistan with journalist Matthieu Aikins, formerly based in Kabul, who went undercover with Afghan refugees to write his book, “The Naked Don’t Fear the Water,” following their journey crossing borders to the West. “It’s very stark, the difference in treatment between the vast majority of refugees who need smugglers to escape and what’s happening in Ukraine right now,” says Aikins. He is a contributing writer to The New York Times Magazine, where in his latest piece he raises the question: Who does the West consider worthy of saving?

FILIPPO GRANDI: When the entire attention of the world is focused on Ukraine, and, by the way, on the refugee crisis that Ukraine — the Ukraine war is producing — and rightly so, because it’s big, it’s serious — I thought it was important to pass the message that other situations which also require political attention and resources should not be forgotten and neglected, especially Afghanistan.

AMY GOODMAN: Afghanistan has faced a looming humanitarian crisis since the Taliban took control last August, with millions on the brink of starvation. The U.N. Refugee Agency says 3.4 million Afghans are internally displaced; another 2.6 million Afghans have fled Afghanistan as refugees.

To discuss all of this, we spoke to the award-winning journalist Matthieu Aikins, contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine, who has reported on the U.S. occupation and war in Afghanistan since 2008. He’s written a remarkable new book. It’s called The Naked Don’t Fear the Water: An Underground Journey with Afghan Refugees. In his New York Times essay, headlined “’We’ve Never Been Smuggled Before,’” he writes about Afghans who are trying to escape their country as its economy is collapsing. Nermeen Shaikh and I recently interviewed Matthieu Aikins. I began by asking him to answer a question he poses in his article: Who does the West consider worthy of saving?

MATTHIEU AIKINS: Imagine right now if Ukrainians, instead of being allowed to cross freely into neighboring countries, into the EU, where they don’t require visas — imagine if they were being forced to cross the mountains and sea with smugglers and risk their lives just to escape this war. And that, of course, is the situation for Afghans, as it was for Syrians, as it was for people in most conflicts in the world. They’re caged in by these borders. They’re not able to cross freely without visas.

And when I went to Afghanistan this summer and fall, I went to the border with Iran and witnessed a new wave of Afghans who are displaced, who are fleeing their country, and spoke to a young couple there named Jawad and Shukria, who are the subject of this article that you mentioned, and they had decided to escape the Taliban and were facing this deadly journey through the desert in order to reach safety. And that, unfortunately, is the situation for Afghans.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And, Matt, on the question of refugees and where Afghan refugees have been able to enter, the vast majority of which were in — of whom were in Afghanistan — sorry, in Pakistan and in Iran, but then, more recently, it’s been harder for them to even enter those countries.

MATTHIEU AIKINS: Yeah, and they need visas, in most cases, and they’re not easy to get. The passport office wasn’t working. This young woman, Shukria, didn’t have a passport before the collapse, and so she couldn’t get one. Even if they do have one, they can’t get visas to the majority of countries. I mean, Afghans have one of the worst passports in the world when it comes to visa-free travel. And that’s actually deliberate. These visa laws are put in place to keep out asylum seekers which the West doesn’t want. So, it’s very stark, the difference in treatment between the vast majority of refugees, who need smugglers to escape, and what’s happening in Ukraine right now, which is, of course, good. People should be allowed to flee wars without having to resort to smugglers.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Matt, before we go to the situation, the political situation, in Afghanistan now — and, of course, later, your book — if you could talk about the humanitarian crisis? As we said in the introduction, 75% of Afghanistan’s population has now fallen into acute poverty, 5 million Afghans facing acute malnutrition, and the U.N. secretary-general warning that the country was hanging by a thread. Could you talk about what you know of the causes of this crisis and what you think needs to be done?

MATTHIEU AIKINS: Well, one thing we have to understand is that there’s been a malnutrition, a poverty crisis in Afghanistan for a long time. Poverty and malnutrition actually got worse during the U.S. occupation, because of the conflict and because of the ineffectiveness of development and aid. But, of course, the collapse has made it far worse. You know, we, over 20 years, built the most aid-dependent state in the world, perhaps in history, and the sudden withdrawal of that aid has had predictable consequences. It’s led to this near collapse of the government and a situation where people don’t have enough to eat, where they’re, in some cases, selling their children, you know, in very young marriages in order to survive, where they’re fleeing across borders just to find jobs. So people are fleeing a catastrophe that we have direct responsibility for. But under the refugee laws that we have today, that wouldn’t count — that doesn’t make them eligible for asylum. You know, someone fleeing starvation is not considered a refugee in the classic definition of the term, the Geneva Convention of 1951. And yet that is absolutely what’s driving a lot of Afghans to leave their country.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: You said, Matt, that a humanitarian crisis is not grounds for Afghans or others seeking asylum refugee status. But in addition to the humanitarian crisis, there have been widespread reports of the Taliban cracking down on women, women activists, former members — members of the former government, as well as on journalists. I mean, are those people still trying to flee the country?

MATTHIEU AIKINS: They are. But like I said, it’s very difficult to leave. You know, people are facing risk of persecution. I have friends there. You know, every day I wake up to messages on my phone, people who are desperate to get out. It’s very, very difficult for them to get visas and leave. And once they do, even if they can get to a neighboring country like Iran or Pakistan, they’re looking at waiting years for refugee resettlement. But there’s a lot of people who are trying to get them out. These are people who want to leave, who have people in the West who want to help them get out, support them. They’re people we have a responsibility for, due to our long involvement in the country and the mess we’ve left behind. And yet, again, because of visa restrictions, because of immigration laws, because of man-made constraints, these people are trapped in a desperate situation.

And so, that’s really, I think, what we should be aware of. And one of the things I wanted to explain in my book is just how much of the suffering and restrictions faced by refugees, faced by migrants, are the result of border policies, are the result of laws. And it really takes a case like Ukraine, where people are just leaving — you know, they’re just getting in their car and driving to Poland — for us to see just how much of the suffering is actually unnecessary in places like Afghanistan.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s take a deep dive into your book, because you tell this story so graphically, what happens to refugees, you know, those who are, quote, “worth saving” and those who aren’t. Matthieu Aikins’ book is called The Naked Don’t Fear the Water: An Underground Journey with Afghan Refugees. We have a rule on Democracy Now!, Matt, and that is no soundbites. So you’ve got to give us the whole meal here. Can you talk about the journey you took, the obstacles, the horror people face when they’re fleeing a desperate situation, which is what you could describe Afghanistan, the country, as over the last decades of the U.S. invasion and occupation of Afghanistan? Talk about your journey.

MATTHIEU AIKINS: Well, the story begins with my friend, whom I call Omar in the book. And Omar was one of the first people I met in Afghanistan when I went there, shortly after I went there in 2008. He had grown up in exile. His parents fled the Soviets. You know, we have to remember, Afghanistan has been at war for 40 years now, tragically. And they came back after 2001 full of hope for the future of their country, for this era of development and peace that the West had promised to Afghans after the Afghan invasion. And he became a translator with the American military. He was also working for Canadians. He spoke English. Then he decided he wanted to work with journalists, so that’s when we met. And we worked together for many years in the country while I was living in Afghanistan. I got to know his family, as well. And like many Afghans, he dreamed of emigrating to the West. He actually applied for one of these special immigrant visas that the U.S. grants to employees, local employees in Afghanistan and Iraq. He should have qualified, but because of all the paperwork restrictions, he was rejected.

So, this happened in 2015, when, as you probably recall, there was a migration crisis in Europe. A million people crossed the Mediterranean Sea — it was the largest movement of refugees in history — in these little rubber rafts. So, the borders in Europe opened briefly, and Omar thought, “This is my chance to go.” So he decided to take the smugglers’ road to Europe in order to escape. And I decided to go with him. But the only way that I could do that was to go undercover as an Afghan refugee myself, because of the danger of being kidnapped or being arrested and separated. And because I have — my mother’s ancestors are Japanese, but I look Afghan and I speak Persian, from living there for so many years. So I was able to do that. So, the book is a story of our journey together through the migrant underground to Europe.

AMY GOODMAN: So, talk about the journey you took. Talk about where you started with your friend Omar and what you faced.

MATTHIEU AIKINS: Well, it started in Kabul, when he decided to go. And he was on the fence about leaving for a while, because he had fallen in love with, you know, a young woman, the neighbor’s daughter, and he didn’t want to leave and risk losing her. But, ultimately, he realized that was the only way her father, who didn’t want the marriage to happen, was going to give him her hand, because he needed to go and have something to show he could bring her legally to Europe perhaps. So he made the decision to set off.