ORIGINALLY POSTED ON MIDDLEBORO REVIEW AND SO ON BLOGSPOT.COM

14 February 22

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

A treacherous alliance is growing that will undermine democratic institutions in the US and elsewhere

After all, it wasn’t long ago that Donald Trump – who openly admired Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin – encouraged racist nationalism in America while delivering much of the US government into the hands of America’s super-rich.

Now state-level Republicans are busily suppressing votes of people of color and paving the way for a possible anti-democratic coup, while the national Republican party excuses the attack on the Capitol – calling it “legitimate political discourse” – and censors Representatives Liz Cheney and Adam Kinzinger, the only two congressional Republicans serving on the panel investigating that attack.

America’s oligarchic wealth, meanwhile, has reached levels rivaling or exceeding those of Russia and China. During the pandemic, America’s 745 billionaires increased their holdings by 70%, adding $2.1tn to their wealth in just over a year.

A portion of this wealth is going into politics. As early as 2012, more than 40% of all money spent in federal elections came from the wealthiest of the wealthiest – not the top 1% or even the top tenth of the 1%, but from the top 1% of the 1%.

Now, some of this wealth is supporting Trumpism. Peter Thiel, a staunch Trump supporter whose net worth is estimated by Forbes to be $2.6bn, has become one of the Republican party’s largest donors.

Last year, Thiel gave $10m each to the campaigns of two protégés – Blake Masters, who is running for the Senate from Arizona, and JD Vance, from Ohio. Thiel is also backing 12 House candidates, three of whom are running primary challenges to Republicans who voted to impeach Trump for the events of January 6.

It’s not just Republicans. Last year, at least 13 billionaires who had previously donated to Trump lavished campaign donations on Democratic senators Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema, according to an analysis of Federal Election Commission records.

The combination of oligarchic wealth and racist nationalism is treacherous for democratic institutions in the US and elsewhere. Capitalism is consistent with democracy only if democracy reduces the inequalities, insecurities, joblessness, and poverty that accompany unbridled profit-seeking.

For the first three decades after the second world war, democracy did this. The US and war-ravaged western Europe built the largest middle classes the world had ever seen, and the most buoyant democracies.

The arrangement was far from perfect, but with the addition of civil rights and voting rights, subsidized healthcare (in the US, Medicare and Medicaid), and a vast expansion of public education, democracy was on the way to making capitalism work for the vast majority.

Then came a giant U-turn, courtesy of Ronald Reagan in America and Margaret Thatcher in Europe. Deregulation, privatization, globalization, and the unleashing of finance created the Full Monty: abandoned factories and communities, stagnant wages, widening inequality, a shrinking middle class, political corruption and shredded social support.

The result has been widespread anger and cynicism. Even before the pandemic, most people were working harder than ever but couldn’t get ahead, and their children’s prospects weren’t any better. More than one out of every six American children was impoverished and the typical American family was living from paycheck to paycheck. At the same time, a record high share of national wealth was already surging to the top.

Starting last July, America did an experiment that might have limited these extremes and reduced the lure of racist nationalism. That’s when 36 million American families began receiving pandemic payments of up to $3,000 per child ($3,600 for each child under six).

Presto. Child poverty dropped by at least a third, and the typical family gained some breathing space.

But this hugely successful experiment ended abruptly in December when Senator Joe Manchin joined 50 Republican senators in rejecting President Biden’s Build Back Better Act, which would have continued it.

They cited concerns over the experiment’s cost – an estimated $100bn per year, or $1.6tn over 10 years. But that’s less than big corporations and the rich will have saved on taxes from the Trump Republican tax cut of 2018. Repeal it, and there would be enough money. The cost is also less than the increase in the wealth of America’s 745 billionaires during the pandemic. Why not a wealth tax?

The experiment died because, put simply, the oligarchy didn’t want to pay for it.

Oligarchic economics coupled with racist nationalism marks the ultimate failure of progressive politics. Beware. When the people are no longer defended against the powerful, they look elsewhere.

Kyrsten Sinema. (photo: Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images)

Kyrsten Sinema. (photo: Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images)

For months, the Arizona senator has stymied the Democrats’ agenda, dragged down her party’s reelection hopes, and earned the ire of her supporters. We still don’t know why.

To make up for these shortfalls, Sinema was last seen wooing the fossil fuel industry at a Houston fundraiser. One executive reported that he was “tremendously impressed” by Sinema’s opposition to the modest filibuster reform that would have allowed Democrats to pass their voting rights agenda. Whether oil money will be enough to protect her from a primary challenge—or bump that 18 percent number up a few notches—isn’t clear. But what choice does she have (besides, you know, helping to pass an agenda that’s popular among Arizona voters)?

The big question for Sinema is what she is trying to accomplish. Joe Manchin, for all his faults, has been relatively clear about what he wanted from the Build Back Better Act: He didn’t want programs that were only funded for a few years; he insisted that social spending be means-tested and that it reduce the deficit; he said he wouldn’t support anything more than $1.5 trillion but showed some openness to a slightly higher number. Sinema, on the other hand? On the filibuster, she peddled a mix of lies and ahistorical myths, insisting, for instance, that the filibuster exists as a mechanism to encourage bipartisanship, when it is, in fact, a tool of obstruction and a product of the Jim Crow era.

On the Build Back Better Act, she was even less clear. She has vociferously opposed raising taxes but has never offered a clue about what components of the measure she was interested in supporting. This contributed to the legislative morass that ultimately helped kill the bill altogether. The best guess was that her opposition was merely performative—that she was making a long-term bet that sinking the Democratic agenda was better for her politically in a purple state than helping to usher it through.

If her ultimate goal was some odd political end—to hoover up enough Republicans and independents to make up for her decline in support from progressives—she’s clearly failed miserably. Her Democratic colleagues are unhappy with her at the moment; her quixotic efforts have alienated her from Democratic organizers in her home state and helped fund efforts to unseat her. (A recent poll found that 55 percent of Arizona Republicans approve of her, versus 44 percent of Democrats. But lest you think she has some future as a party-switcher, recall that she voted to convict President Donald Trump in both of his impeachment trials—a certain deal-breaker.)

Meanwhile, she’s done no small amount of damage to Kelly’s chances of reelection. Though popular, he will face a tough race later this year in an election that will almost certainly be a bloodbath for congressional Democrats. “I do think that Kyrsten Sinema is making it significantly more difficult for Mark Kelly to get re-elected,” one Arizona Democrat told Insider last month. “This is not what we wanted to talk about right now,” they continued. “It’s like a vacuum that’s taking away from the focus that needs to be on Mark Kelly right now … instead we’re fighting against ourselves here.”

Ultimately, this has been Sinema’s greatest, and perhaps only, accomplishment. She has claimed the center of attention for herself and, in doing so, has divided the Democratic Party, stymied its legislative agenda, and damaged the reelection chances of herself and her fellow Democrats. Perhaps she had some galaxy-brain motive for this—though it may also be that Sinema has simply decided that the only issues she cares about are high-proof deficit hawkery and a commitment to keeping the wealthy from paying taxes—but even if that were the case, it’s been clear for months that her lonely stance against social spending and voting rights is accomplishing nothing from a political or policy perspective.

While much of the focus of Democratic frustration has focused on Manchin, the West Virginia senator’s political considerations are easy to understand. Democrats need him to accomplish anything: Whenever he leaves the Senate, it’s likely that decades will pass before another West Virginia Democrat holds his seat; his approval rating in his home state is 60 percent, while Joe Biden’s is 32 percent. If Manchin sees a political benefit in killing the version of the Build Back Better Act that was approved by Democratic leaders—however unconscionable doing so may be—there’s at least a case to be made that he’s making the correct call from a raw political perspective. No such case can be made for Sinema: She has simply spent the last year acting like an inscrutable doofus while screwing things up for everyone around her.

Theoretically, the situation is repairable. Sinema is not up for reelection until 2024—there’s more than enough time for her to get with the program. But from a practical standpoint, it’s already too late. The Democrats will almost certainly lose at least one house of Congress in the midterm elections, ensuring that Republicans will return to their obstructionist crouch. The time to get things done is now—or, more accurately, was a few months ago. Sinema has opted to spend Biden’s first year in office repeatedly shooting herself in the foot, alienating the members of her party, and driving her stateside supporters away in droves. Hope it was worth it.

Biden and student debt. (image: Insider)

Biden and student debt. (image: Insider)

Biden said on the campaign trail that if elected, he'd seek to "immediately" wipe out at least $10,000 in student debt for every federal borrower, a move that advocates say is in his authority. But over a year into his presidency, Biden has failed to deliver on that pledge, leaving borrowers like Rob frustrated.

"I know that I'm going to have to start making payments," Rob, who's studying to become a teacher and did not want to disclose his full name for privacy reasons, told Insider. "Teachers don't make a lot, and it's going to have a big impact on me, already just on my quality of life."

Indeed, the 34-year-old, along with about 45 million other Americans who took out federal loans for their higher education, will have to resume loan payments on May 1 when the Biden administration's pandemic pause expires.

"It's upsetting because you vote for Democrats, and they honestly never really follow through with their promises at all," Rob said. He owes about $60,000 in student debt and said he won't vote in this year's midterm elections unless the president follows through with $10,000 in cancellation.

"I would be shocked, and I'd be thrilled to go to the voting booth if they do do it," he added. "But right now they need to earn my vote, and right now they're not doing it."

The White House has been slow to take sweeping measures on student-debt cancellation as Biden questions his legal ability to do so and punts the responsibility to Congress. In the meantime, the student-loan companies that process the record-breaking $1.7 trillion debt have poured money into lobbying and politicians' war chests to oppose broad cancellation — spending that could provide some clarity on Biden's inaction.

Recent Democratic-led efforts to stanch the flow of money into politics have tanked. Yet despite spending and lobbying, experts say there is a glimmer of hope for advocates fighting for student-debt cancellation to push back.

"This is an interesting sort of David and Goliath battle," said James Thurber, a political scientist at American University who teaches an ethics and lobbying seminar, "where David is winning on a few things but not over the entire policy change."

Student-loan companies spend millions to keep their industry alive

Why Biden has not pursued broad student-debt forgiveness is unclear, but the student-loan industry's wide-reaching influence on politics might shed some light on the administration's position.

Student-loan companies spent nearly $4.5 million on lobbying efforts last year, according to OpenSecrets, a nonprofit that tracks campaign-finance and lobbying data. The industry lobbied against student-loan payment pauses during the pandemic, along with student-debt issues in Biden's COVID-19 stimulus package last year. In 2020, the industry spent about $4 million on lobbying.

The federal government hands out contracts to these companies to service student loans to borrowers. In exchange, companies earn fees for each loan they service.

Navient, previously one of the largest federal student-loan servicers, spent nearly $1.7 million on lobbying last year and earned $717 million in profits. (Mired in decades of controversies and allegations of misleading borrowers, Navient received approval from the Education Department in October to shut down its federal-loan services at the end of last year. The company has consistently denied wrongdoing but recently reached a settlement with 39 attorneys general over accusations of abusive practices.)

Another major student loan company, Nelnet, spent $230,000 on lobbying in 2020. That same year, Nelnet made over $352 million in profits. Nelnet did not return Insider's request for comment.

"They're lobbying to make sure that they have profit. They're not lobbying for the public interest of students, in my opinion," Thurber told Insider. "They're interested in the bottom line."

Navient, in its 2021 midyear lobbying report, said the company had rallied behind a variety of student-debt-related issues, including improving loan-repayment programs, assisting borrowers in default on their debt, and easing the process for bankruptcy discharges. The company did not provide comment for this story.

Student-loan companies, through political action committees, are also major donors to political campaigns. In 2020, the industry donated about $715,000 to candidates, with the money evenly split between both parties, according to OpenSecrets.

Biden was the top recipient of contributions from student-loan companies in 2020, with $38,535, followed by his opponent, former President Donald Trump, who got $25,716.

"Our concern is always that monied interests have a much bigger presence and effect on policy," Dan Auble, a senior researcher at Open Secrets who focuses on lobbying data, told Insider.

This spending isn't new. According to Open Secrets, student-loan companies have exhausted more than $47 million on lobbying the federal government and nearly $5.5 million on campaign contributions over the past decade, seeking to prevent student-debt policies that run counter to their interests.

"There are other forces at work that are also influencing what's happening. So it's certainly not the only factor, but you can be fairly certain that the business interests involved in the student-loan issue are having their voices heard," Auble said.

Rep. Virginia Foxx of North Carolina, the highest-ranking Republican on the House Education and Labor Committee, has received nearly $30,000 in contributions from student-loan companies over the past two election cycles. She recently decried Biden's extension of the pause on monthly loan payments and has opposed student-debt cancellation.

Foxx did not return Insider's requests for comment.

Democrats fail to reduce the power of money in politics

The power of lobbying does not appear likely to weaken any time soon. Since Biden took office, Democrats have unsuccessfully sought to curb the influence of money in politics. The For the People Act, an elections and campaign-finance overhaul that passed the House last year but was blocked by the Senate, would have tightened ethics laws for federal officials and lobbyists.

Specifically, the legislation would have slowed the so-called revolving door of government officials who become lobbyists for the industries they previously oversaw, and rely on their insider knowledge and connections to push forward their clients' interests. More than half of the lobbyists in the education industry have walked through the revolving door, OpenSecrets has found.

"Lobbyists are actually writing legislation and pieces of legislation. They have relationships with the people on Capitol Hill and in the White House and the executive branch. They often have passed through the revolving door," Auble said. "They have a good idea of how to put pressure on the various levers of government. So it's clear that the close to $4 billion that is spent on lobbying each year is having some effect on policy."

Current law maintains that former senior-level government officials should hold off for a year until they engage in lobbying. The For the People Act would have doubled that waiting period to two years, as many officials often defy the current rules.

The bill would have also increased transparency by closing what's known as the "shadow lobbying" loophole, which refers to individuals who attempt to influence policy, for example, by meeting lawmakers or advising lobbying firms, but who are not actively registered as lobbyists.

"There's a lot of people on the Hill lobbying and meeting the definition of lobbying," Thurber said, "but they're not registered, and that's wrong. It needs to be enforced more."

Yet the over 800-page legislation failed in the Senate because Republicans widely opposed the bill, and Democrats could not overcome the 60-vote filibuster requirement.

"Mitch McConnell said he would not take up anything" in the bill, Thurber, who's personally in favor of increased transparency around lobbying and worked on reforms during the Obama administration, told Insider. "There were things in there on lobbying that even many Republicans in the Senate wanted, but no one is touching it because that's what his position is as the minority leader."

"I think the strategy of the minority party in the Senate is no — no on everything," he continued.

Many Americans have long held perceptions that corporate, wealthy interests and lobbyists hold too much power over policymaking, contributing to distrust in the federal government. Democratic, Republican, and independent voters have all expressed support for cleaning up political corruption.

Transparency around lobbying is important "because in a democracy, you have to have trust in the institutions that are making your laws," Thurber said. "If you've got all kinds of vested, narrow interests, having an influence and you don't know about it, it really undermines democracy, fundamentally."

The public can still wield influence over policy

Republicans balk at broad student-debt forgiveness, saying Americans would bear the brunt of the costs in the form of lost government revenue from loan payments. Canceling $10,000 in federal student debt per borrower would cost about $373 billion, according to Brookings. On the other hand, Democrats backing student-debt cancellation say the move would stimulate the economy and decrease the country's racial wealth gap.

Both sides — those in favor of debt cancellation and those against — have pushed Biden to act in their favor. Yet substantial progress on student-debt reform under his administration could ultimately depend on which competing force wins out.

Grassroots activism can prove effective if done correctly, experts say. Social-media campaigns, on-the-ground advocacy, advertising, connections on Capitol Hill and the White House, and clear messaging, are strategies that can influence policy decisions, Thurber said.

Standing against the student-loan companies is a slew of advocacy groups, labor unions, and nonprofits, as well as dozens of Democratic lawmakers who have championed the issue. At least 18 nonbusiness organizations, such as the Bipartisan Policy Center, American Civil Liberties Union, and the American Federation of Teachers, lobbied for student-debt cancellation in 2021, OpenSecrets found.

"Money alone doesn't always counteract popular organization for a particular position," Thurber told Insider. "Money does buy access. It doesn't always buy the policy that you want though."

In the student-debt arena, some of that campaigning has paid off. For instance, under immense public pressure, Biden extended the loan-payment pause, set to end in February, another 90 days until May 1.

Once a far-fetched idea, student-debt forgiveness has gone mainstream in recent years, as the debt climbs to historic highs, borrowers struggle to pay their loans, and political candidates, including Biden, promote policies to address the crisis. Americans appear to be on board, with a majority of respondents repeatedly saying the government should cancel at least some of the $1.7 trillion debt, according to polling.

"Sometimes the public good wins and overcomes campaign contributions and lobbying expenditures. It's rare, but sometimes it does," Thurber said.

Forgiving the debt could energize voters ahead of this year's midterms and potentially offer Biden a boost to his approval ratings, which have slumped to 41% amid inflation woes and the continuing COVID-19 pandemic.

Biden stalls on a campaign pledge

When pressed on the president's failure to enact $10,000 in student-debt cancellation, the Biden administration has recycled a response: touting already-implemented relief, deferring to Congress, and at times sidestepping the issue.

"The President supports Congress providing $10,000 in debt relief. And he continues to look into what debt relief actions can be taken administratively," a White House spokesperson said in a statement to Insider.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, two leading Democrats supporting student-debt cancellation, have struck down the idea of crafting a bill to cancel student debt, saying such legislation would not succeed in today's partisan Congress.

Hundreds of advocacy groups, along with a number of Democrats like Schumer and Warren, believe the responsibility to forgive student debt is Biden's. They argue that Biden can act on the same executive authority through the 1965 Higher Education Act that he used to extend the payment pause to eliminate student debt.

"The president already has the power to cancel $50,000 of student-loan debt. It's time for him to do that," Warren told Insider.

Braxton Brewington, a spokesperson for the Debt Collective, the nation's first debtors' union, told Insider that "$1.8 trillion of crushing student debt is a major policy failure that Biden can fix with the stroke of a pen."

Documents obtained by the Debt Collective found that the Education Department had completed a memo in April on Biden's legal ability to wipe out student debt. The White House has yet to release its results.

To be sure, Biden has not completely neglected the student-debt crisis. Some steps he's taken include canceling nearly $15 billion for targeted groups, such as those with disabilities and those defrauded by for-profit schools.

An Education Department spokesperson told Insider that while "we continue to deliver immediate relief for those struggling with debt, we are also making permanent changes that reduce indebtedness and make college more affordable."

"The department is also continuing to work closely with the White House to review additional options with respect to debt cancellation," the spokesperson added.

Megan Erickson, a Biden voter who has a five-figure balance in student debt that she calls an "embarrassingly large amount of money," said she'd like to see his administration buckle down on long-term solutions to the debt crisis, including making college more affordable and easing the loan-repayment process.

But, she added, "the idea of a reduction is so very appealing."

The $10,000 debt cancellation has "been an ongoing topic in our household," Erickson told Insider. "Could you imagine, what if this did happen? And then we'll go back and forth as to, well, if it did happen, where would it come from and how do we make it better for people going forward?"

Eminem kneeling at the Super Bowl. (photo: Pepsi/Daily Beast)

Eminem kneeling at the Super Bowl. (photo: Pepsi/Daily Beast)

The embattled league now says it signed off on the rapper’s gesture of support of Colin Kaepernick and his fight against racial injustice.

The move by Eminem came after he performed “Lose Yourself” in front of the sold-out crowd at the Los Angeles Rams’ SoFi Stadium in Inglewood, California. If you recall, Kaepernick led a series of protests meant to highlight the injustice of police brutality against Black Americans that involved players kneeling during games as the national anthem played. He was subsequently pushed out of the league and received a sizable settlement from the NFL.

Early reports claimed the NFL had denied Eminem’s request to kneel during the performance, but he did so anyway in defiance of their decree. They also tried to prevent Dr. Dre from rapping the line “still not loving police” in his song “Still D.R.E.,” but he didn’t listen either.

However, the NFL claimed it was in on it all along, even signing off on Eminem’s mimicking of Kaepernick’s career-ending gesture after watching it in rehearsals all week.

“We watched all elements of the show during multiple rehearsals this week and were aware that Eminem was going to do that,” league spokesman Brian McCarthy said, according to ESPN.

The masking debate continues for schools. (photo: Jon Cherry/Getty Images)

The masking debate continues for schools. (photo: Jon Cherry/Getty Images)

Democrats are caught in the middle of school masking wars, and some blue states are lifting the rules.

The classroom was always going to be the last stand for the mask wars in California. Schools stayed closed longer here than anywhere else in the country as teachers unions made access to vaccines a condition of their return. More recently, teachers have demanded better masks and more testing to guard against the Omicron variant.

Gov. Gavin Newsom seems ready to eliminate mask requirements in schools, as his counterparts in New Jersey, Oregon and Connecticut did this week. But Newsom cannot go where teachers unions aren’t ready, as was the case with school reopening a year ago.

“They just asked for a little bit more time, and I think that’s responsible, and I respect that,” the governor said of teachers unions at a news conference Wednesday. “But we are also in a date with destiny. We recognize that we want to turn the page on the status quo.”

Newsom is not the only one still requiring masks in schools; New York Gov. Kathy Hochul is maintaining a similar mandate, as is Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker, though those states are among a dwindling number.

Democrats again face an internal struggle — caught between evidence that high-quality masks reduce transmission, parental concerns that children have lost a sense of normalcy and pandemic fatigue among all involved. President Joe Biden is trying to figure out next steps as his top health advisers are still urging schools to maintain mask requirements while Democratic governors are abandoning that approach.

Newsom has promised to release a plan for easing school masking rules. But he also pointed to the relatively low vaccination rates for children under 12 as the sticking point in labor negotiations.

If the new policy is tied to higher vaccine uptake, those changes could be slow to arrive.

So far, about 33 percent of kids ages 5 to 11 have received at least one dose of the vaccine, according to the latest state figures, compared to 89 percent of Californians 18 and older. School districts in Los Angeles and Sacramento put their vaccine mandates on hold instead of sending large numbers of unvaccinated students back into remote learning.

California’s top priority is to keep schools open, state epidemiologist Erica Pan said — and that may mean sticking with masks even as the requirements for California businesses expire next week.

“Frankly, schools have been an extremely safe place to be, especially with masks,” Pan said Tuesday during a webinar with other medical professionals hosted by the California Medical Association.

Pan cited guidance from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Academy of Pediatrics that supports universal school masking, and said she knew of no data showing that masking children causes them physiological, developmental or social harm. Public health experts generally support mask-wearing, while some studies show the benefit to be largely dependent on the type and fit of the mask.

The California Teachers Association, which has more than 300,000 members, declined to comment on its discussions with the Newsom administration. The state’s second-largest teachers union, the 120,000-member California Federation of Teachers, says any end to mask restrictions must have sufficient justification beyond political reasons.

“We support developing a plan for transitioning away from masking in schools — an off-ramp — that is based on science and not politics,” CFT President Jeff Freitas said in a statement.

Parents are divided on the subject. Some are increasingly frustrated with what they see as needless and harmful restrictions and argue masking should be optional; some high school students have walked out of class in protest of the rules. But others worry their children could put vulnerable relatives at risk or have their schooling disrupted yet again if they are exposed to the virus — even if they are vaccinated.

“I think it’s too early,” said Mindy Reed, the mother of a 17-year-old student in the small Central Coast town of Cambria about lifting masking rules in classrooms. “The mask mandate shouldn’t require kids to wear the masks outside, but I think in the classrooms we still need to protect them.”

The masking debate has boiled over in the Bay Area, where some school districts have one-upped the state’s rules by having children mask outdoors or wear medical masks instead of cloth coverings.

On Wednesday, more than 450 San Francisco parents signed onto a letter to Mayor London Breed urging optional masks for school kids, citing their relatively low risk of serious infection.

Meanwhile, school districts are bracing for impact. Kevin Gordon, a prominent education lobbyist, said he has been flooded with calls from school leaders up and down the state who are worried about backlash as the state eases the mandate in other settings, but not schools.

“We are having districts communicate to the governor and lawmakers the need to make sure schools are not forced to stay masked while the rest of the community ends up not being masked,” Gordon said.

Some teachers agree that the mandate has lasted too long.

“I’m ready to take the mask off now,” said Jason Avicolli, a social studies teacher at Las Lomas High School in the Bay Area city of Walnut Creek who argues universal masking has caused “detrimental mental effects, psychological, social and emotional damage.”

Ernesto Falcon, a Bay Area parent who has been outspoken about school reopenings and mask mandates, said it seems public officials are using masks to assuage fears instead of clearly communicating evidence suggesting they aren’t needed.

“The government’s job and the public school system’s job is to say, ‘Well, that’s not necessary for safety,’” Falcon said. “Instead they did the opposite, of ‘Oh my gosh, these parents are scared, let’s just require it as well.’”

Yet even as the state eyes the masking exits, some districts are moving in the other direction.

The United Teachers of Richmond just last week clinched an agreement with the West Contra Costa Unified School District requiring kids to wear medical masks and a series of tests for students and staff after a positive case in a classroom.

The union president, Marissa Glidden, said in an email that local high school students “led the advocacy for better masks at schools,” and that the upgrade requirement stemmed from public health guidance. When asked about an endpoint for those measures, Glidden said the union would discuss that with the district if county and state recommendations changed.

“Right now,” Glidden wrote, “the state has shared they will continue the school mask mandate beyond February 15th.”

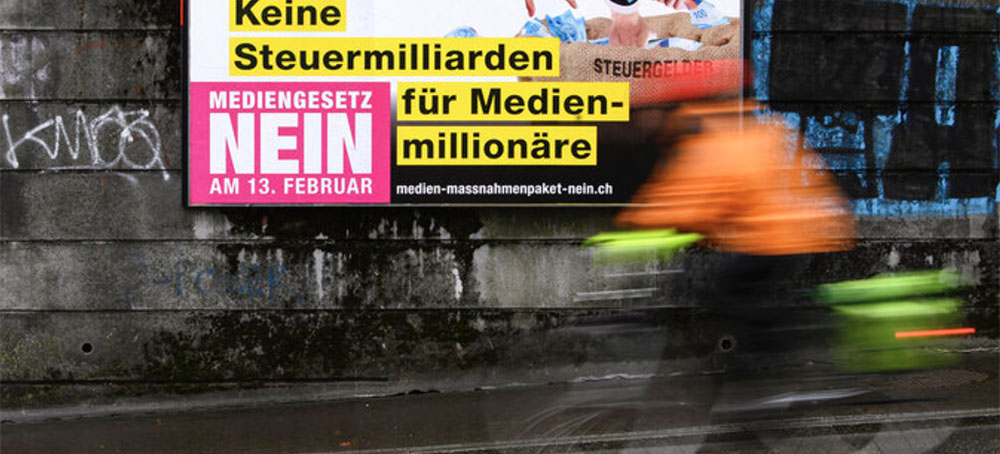

A poster reading 'No tax billions for media millionaires. Media Law No' displayed on a wall in Bern, Switzerland, Wednesday, Feb. 2022. (photo: Anthony Anex/AP)

A poster reading 'No tax billions for media millionaires. Media Law No' displayed on a wall in Bern, Switzerland, Wednesday, Feb. 2022. (photo: Anthony Anex/AP)

Some 56% of voters rejected the measure, public broadcaster SRF reported.

Opponents of the plan, which had been passed by Swiss lawmakers in June, had pulled together enough signatures in a petition to put the issue before the public, part of Switzerland’s particular form of democracy that gives voters in the country of 8.5 million a direct say in policymaking.

Foes of the plan had said the cash injection would waste taxpayer money, benefit big newspaper chains and the media moguls who run them and hurt journalistic independence by making media outlets more dependent on state handouts and thus less likely to criticize public officials. They also said it was discriminatory, since free newspapers wouldn’t benefit.

“A media subsidized by the state is a media under control. As the adage goes: ‘Don’t bite the hand that feeds you,’” wrote the opponents who pressed for the referendum. They say big print-media groups together took in more than 300 million in profits in 2020, even during the COVID-19 crisis.

Many other countries in Europe and beyond offer support to newspapers through postal fee discounts, tax breaks and other measures.

Supporters of the cash injection had countered that journalism, especially in local areas ill-served by big media groups, should be considered a public service, as are many public radio and television broadcasters in Switzerland and around Europe.

“Media groups are fighting to survive. Ad revenues for print press haven’t stopped declining or are getting swallowed up by giants like Facebook and Google, and subscriptions aren’t enough,” the Swiss Green party, which supported the measure, had argued before the vote.

Proponents said more than 70 papers have disappeared since 2003. Advertising revenue in all print publications plunged 42% between 2016-2020 in Switzerland.

Brown coal is among the dirtiest energy sources, but it still makes up Germany's largest source of power. (photo: Joakim Eskildsen/The New Yorker)

Brown coal is among the dirtiest energy sources, but it still makes up Germany's largest source of power. (photo: Joakim Eskildsen/The New Yorker)

The country embarked on an ambitious plan to transition to clean energy, aiming to lead the fight against climate change. It has not been easy.

Görlitz, which was barely damaged in the Second World War, often stands in for prewar Europe in movies and TV shows. (“Babylon Berlin,” “Inglourious Basterds,” and other productions have filmed scenes there.) It was a startling sight nonetheless, especially since, a few hundred yards away, a crowd was gathering for the AfD, the far-right party whose incendiary rhetoric about foreign migrants invading Germany has raised alarms in a country vigilant about the resurgence of the radical right.

In fact, at the rally, the rhetoric about foreigners from the AfD’s top national candidate, Tino Chrupalla, was relatively mild. Germany’s general success with handling the wave of more than a million refugees and migrants who arrived in the country starting in 2015 has helped undermine the Party’s central platform. Chrupalla moved on from migrants to other topics: the threat of coronavirus-vaccination mandates for schoolchildren, the plight of small businesses, and the country’s desire to stop burning coal, which provides more than a quarter of its electricity, a greater share even than in the United States.

Coal has particular resonance in the area around Görlitz, one of the country’s two large remaining mining regions. Germany’s coal-exit plan, which was passed in 2020, includes billions of euros in compensation for the coal regions, to help transform their economies, but there are reports that some of the money has been allocated to frivolous-sounding projects far from the towns most dependent on mining. Chrupalla, who is from the area, listed some of these in a mocking tone and told the crowd that the region was being betrayed by the government, just as it had been after German reunification, when millions in the former East Germany lost their jobs, leading many to abandon home for the West. “We are being deceived again, like after 1990,” he said.

Such language was eerily familiar. For years, I had been reporting on American coal country, where the industry’s decades-long decline has spurred economic hardship and political resentment. In West Virginia, fewer than fifteen thousand people now work in coal mining, down from more than a hundred thousand in the nineteen-fifties. The state is the only one that has fewer residents than it did seventy years ago, when the U.S. had a population less than half its current size—a statistic that is unlikely to surprise anyone who has visited half-abandoned towns such as Logan, Oceana, and Pineville. Accompanying the decline has been a dramatic political shift: a longtime Democratic stronghold, West Virginia was one of only ten states to vote for Michael Dukakis, in 1988; in 2020, it provided Donald Trump with his second-largest margin of victory, after Wyoming, which also happens to be the country’s largest coal producer, ahead of West Virginia.

The statistics are strikingly similar in Lusatia, the coal-mining region that stretches north of Görlitz along the Polish border, straddling the states of Brandenburg and Saxony, about ninety miles southeast of Berlin. Since 1990, employment at coal mines and power plants has plunged from eighty thousand to less than eight thousand, and the region’s population has fallen sharply, too. Hoyerswerda, in the heart of the area, has lost more than half of its seventy thousand inhabitants, leaving a constellation of vacant Eastern Bloc high-rises; Cottbus, the region’s largest city, has dropped from roughly a hundred and thirty thousand people, just before the Berlin Wall fell, to less than a hundred thousand. And the rightward shift visible in West Virginia has happened here, too: along with the rest of eastern Saxony, Lusatia is the AfD’s stronghold, with the Party capturing more than a third of the vote in some towns.

But there’s one crucial difference between the two places. As part of its Energiewende, or energy pivot, Germany has embarked on a formal effort to exit coal, with a national commission and subsequent legislation setting specific closure deadlines for mines and plants, and distributing billions of euros in compensation to coal companies, workers, and the regions themselves. In the U.S., the coal exit has been haphazard. Federal attempts to move beyond coal went dormant under President Donald Trump, and under President Joe Biden they are now running up against the opposition of Senator Joe Manchin, the West Virginia Democrat who holds both the crucial fiftieth vote in the Senate and a stake in a family coal business that earned him nearly five hundred thousand dollars in 2020. To the extent that the country has reduced its coal usage, it has been driven mostly by the profusion of cheap natural gas. The effort to provide solutions to the social and economic fallout for coal regions has been limited to fledgling projects, such as a working group that Biden convened last year to identify communities in need and funding opportunities for them to pursue.

This contrast was what brought me to Lusatia. The German coal exit has assumed outsized symbolic importance in a world that desperately needs to reduce carbon emissions: the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says that we need to stop adding carbon dioxide to the atmosphere by 2050 in order to have any hope of keeping warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Burning coal for electricity represented nearly a third of all energy-related carbon emissions—the world’s single largest source—in 2018, and the International Energy Agency believes that global consumption of coal power reached record levels last year. In the absence of leadership from the U.S., Germany is seeking to show how a major manufacturing power can reduce its reliance on coal without causing too much economic damage or political backlash. A lot is riding on whether the country can pull it off.

“God created Lusatia, and the Devil buried brown coal underneath it.” This saying is credited to the Sorbs, the ethnic Slavic people who have lived in the region—die Lausitz—since the sixth century. The land was swampy, and the area remained relatively impoverished, with the exception of the cities at its southern end, Görlitz and Bautzen, which flourished as market hubs on one of Central Europe’s primary east-west trade routes.

Everything changed after the discovery of the brown coal, in the late eighteenth century. Brown coal, or lignite, is sedimentary rock that is less compressed than typical bituminous coal. Lignite is softer, closer to peat in carbon’s geological arc. It’s also even dirtier to burn than bituminous coal, and emits even more carbon.

Because lignite sits closer to the surface than bituminous coal, workers don’t need to dig deep shafts and tunnels. Instead, they use the open-cast method, excavating the clay and sand that lie above the lignite seam. This is safer than sending workers deep underground. But it requires removing everything that stands in the way, and in densely settled Central Europe that means demolishing villages—Braunkohle mining has led to the destruction of hundreds of communities in Germany. Once the mines are exhausted, they are either flooded to become lakes or levelled off with fill, which often leaves the land unusable for farming and in some cases even too unstable to walk on. “No entry” signs dot the local woods.

Open-cast mining started in Lusatia around 1900, and, in the decades that followed, the villages targeted for destruction tended to be Sorbian. The new industry brought a wave of workers to the area, mostly ethnic Germans, and a prosperity that it hadn’t known before. Lusatia produced coal briquettes that warmed homes, and the fuel that lit the streets of Berlin and powered factories in Chemnitz and Dresden. The German word for miner has a noble connotation: Bergmann—literally, “mountain man.”

Brown coal is found in western Germany, too, near Cologne. But there it was long overshadowed by the much larger sprawl of bituminous mines in the Ruhr region, just to the north. These mines transformed the area into Germany’s great industrial powerhouse, a vast urban agglomeration home to Essen, Dortmund, and other manufacturing cities. Germany’s coal riches were integral to the new nation’s rise in the late nineteenth century, to the war machine that sustained it through two horrific conflicts, and to West Germany’s rebound in the nineteen-fifties, after which the region’s bituminous mining became less competitive with imported coal. In 2018, mining of bituminous coal in Germany was shut down for good.

In the coal regions of the former East Germany—Lusatia and a second region, near Leipzig, which has seen employment decline even more precipitously—the cultural and economic hold of coal persists. Braunkohle was the German Democratic Republic’s only major energy resource—it had almost no oil or bituminous coal—so the country opened several dozen open-cast mines in the postwar decades, destroying many more villages in the process. It built high-rise apartment towers in the larger towns to relocate people from the destroyed villages and to house mine workers. It gave these workers preferential pension payments and exalted them as paragons of the “workers’ and farmers’ state,” as the country’s leaders called the G.D.R. “Being a miner meant something,” a retired excavator operator, Monika Miertsch, told me. A former electrical engineer in Cottbus recalled that, when he was a child in the G.D.R., his teachers endlessly told students that their small nation produced more brown coal than any other country in the world. Christian Hoffmann, a naturalist who grew up in Weisswasser, in Lusatia, said that people would snap to attention whenever a band started playing the coal-miner anthem, “Steigerlied.”

The industry permeated local life. The soccer team in Cottbus is named Energie. Regional artists put Braunkohle mines on canvas—a museum in Cottbus recently held a retrospective of the work. One of East Germany’s best-known singer-songwriters, its Bob Dylan, was an excavator operator from Hoyerswerda named Gerhard Gundermann, who kept working in the giant pits even as his musical career blossomed.

After my first visits to Lusatia, which is now home to slightly more than a million people, the dominance of Braunkohle started to seem overwhelming. It was as if everyone was working for the industry or had lost his or her family’s village to it, or both—which helped explain why some residents weren’t too upset about the latter. It made for an especially stark manifestation of the trade-off between the coal-based development of the modern world and the environmental costs that came with it. “They knew that it gave work. They accepted it,” Hannelore Wodtke, a member of the town council in Welzow, said when we met. We were in Proschim, a village that she helped save from a planned expansion of the Welzow-Süd mine, two years ago. “Through coal, people did earn well. And that’s why it looks pretty good around here.”

One Saturday, I accompanied a group into the Welzow-Süd mine, on a tour offered by the owner of all the Lusatian mines, a Czech-controlled company called LEAG. We started at an outlook above the mine, a vast barren moonscape stretching to the horizon, four miles across, and then a bus took us down a long winding dirt road, pausing to let us admire giant excavators—more than six hundred feet long, among the largest machines in the world—that would resume work on Monday morning.

At last, we arrived at a seam of brown coal, about three hundred feet underground. A guide handed out plastic bags and encouraged us to pick up chunks as souvenirs. Some pieces were so soft or ragged that they resembled old wood or caked mud. It was hard to believe that this rudimentary stuff was still powering one of the wealthiest countries in the world.

I recalled a similar moment, years earlier, when I was far belowground, in a mine in southern Illinois, watching workers shear bituminous coal off a seam at the end of a three-and-a-half-mile tunnel. It had seemed unbelievably archaic at the time—men tossed hunks of black rock onto a conveyor belt so that we could power our laptops and cell phones. The giant hole in Lusatia seemed even more unfathomable: machines had destroyed villages, and then larger machines had dug into the fossilized past for three-hundred-million-year-old carbon with which to fuel yet other machines, our daily life.

“Watching coal-miners at work, you realize momentarily what different universes different people inhabit,” George Orwell wrote in “The Road to Wigan Pier,” his 1937 account from the North of England. “Down there where coal is dug it is a sort of world apart which one can quite easily go through life without ever hearing about. Probably a majority of people would even prefer not to hear about it. Yet it is the absolutely necessary counterpart of our world above. . . . Their lamp-lit world down there is as necessary to the daylight world above as the root is to the flower.”

That quality of not wanting to hear about the mining of coal, the reluctance of those in far-removed cities to make the connection between their world and that other one, provoked much of the resentment in the producing regions of the U.S. “This country benefitted from having the cheapest electricity in the world,” Cecil Roberts, the president of the United Mine Workers of America, told me in New York in July, after a rally of current and retired miners on behalf of striking Warrior Met Coal workers, in Alabama. “So what are we going to do with these communities?”

I heard a similar sentiment from miners in Germany. “If we really shut down now, then Berlin will have no more electricity,” Toralf Smith, a leading representative for power-plant workers in Lusatia, told me. “And I’d like to see how it goes at the universities in Berlin when the toilets don’t function and the cell phones don’t function and the Internet doesn’t function. When their lives don’t function. It’s a lack of respect. If we have to switch things over for the sake of climate politics, we won’t stand against that, but it can’t be done on our backs. It has to be done with us.”

In 2019, the sociologist Klaus Dörre, of the University of Jena, and a team of researchers interviewed dozens of coal workers in Lusatia about the region’s transition away from the industry. They found that workers keenly felt the loss of Anerkennung—recognition or esteem—that they and their forebears had enjoyed in East Germany. The workers cited opprobrium like that from a Green Party state legislator in western Germany who tweeted a protest poster that read “Whether Nazis or coal, brown is always shit.” One worker told the researchers, “In [East German] times, we were the heroes of the nation—that’s what they always said. And now we’re the fools or evildoers of the nation, because we have to let ourselves be scolded as Nazis or murderers or polluters and I don’t know what else. And that hurts.”

When I visited Dörre in his office in Jena, he said that the overriding theme from the interviews was the lingering trauma of the economic dislocation after the collapse of the Wall, a period known as die Wende. “The story that was told to us was ‘We’re the survivors, from eighty thousand down to eight thousand. Now you’re all coming and want to give us a second Wende.’ ”

But his team also found that the workers were not necessarily all gravitating to the AfD as a result of their anger and anxiety. Organized labor still has a strong hold on the German coal industry, unlike in the U.S.; the national coal workers’ union is allied with the center-left Social Democratic Party, and has managed to keep many members from straying right. Union leaders, as Dörre wrote in a report summarizing his research, hope that the region as a whole can also be kept from straying too much further right: “If you can manage to show that positive development is possible for the region, despite the coal exit, that would cut the ground out from under the AfD.”

In 2020, China built more than three times more new capacity for generating power from coal than the rest of the world combined. Last year, despite recurring pledges to start corralling carbon emissions, the country produced a record four billion tons of coal, up nearly five per cent from the year before. Defenders of coal in Germany like to point to figures like this, along with the fact that Germany’s greenhouse-gas emissions constitute a mere two per cent of the global total. Why should Germany be putting its economy at risk for such relatively slight gains?

Such arguments have stood little chance against Germany’s vigorous climate-activism movement. Activists and energy analysts told me that the country bears a special responsibility to reduce emissions. As a major industrial power, it produced a significant share of historical emissions; as manufacturing has shifted to Asia, the nation’s consumers are relying on goods produced elsewhere, making them partly responsible for emissions there, too; and, as a wealthy nation, Germany has the resources to demonstrate a better path. “It makes a huge difference if well-off, industrialized Germany manages to transition away to a different system that sustains its prosperity without causing massive emissions,” Benjamin Wehrmann, a Berlin-based correspondent for Clean Energy Wire, said. “Most people in the industry agree that its signalling effect is much larger than the actual effect.”

This exceptionalism has, however, complicated the effort to leave coal. Germany has long been home to a strong anti-nuclear movement, partly as a result of its fears of being caught in the middle of a Soviet-U.S. nuclear war. In 2000, the governing coalition of the Social Democrats and the Green Party, whose roots lay in anti-nuclear activism, agreed to phase out nuclear power. Chancellor Angela Merkel reversed this stance in 2009, after her center-right Christian Democratic Union regained power, but in 2011, in the wake of the Fukushima disaster, she announced that the country would close all seventeen of its nuclear power plants within eleven years. To replace the lost energy—nearly a quarter of the country’s load at the time—Germany would ramp up renewable energy. Thus the Energiewende accelerated.

Since then, the country has greatly expanded its wind and solar capacity. The dramatic shift toward renewables in a country of eighty-three million people helped drive down prices worldwide for wind and solar equipment, fulfilling the country’s self-conception as a market leader. (This plunge in prices came at a cost, though, as cheap Chinese solar panels put many German panel-makers out of business.)

But the expansion has slowed in recent years, owing to a combination of state-level restrictions on siting wind turbines, resistance to turbines and transmission lines among conservationists and local residents, and a reduction in subsidies for wind-power developers. In the first half of 2021, coal was back to providing more of the country’s electricity than wind. Most experts estimate that, to meet its renewable-energy goals, Germany needs to quadruple its wind production, to the point where turbines cover two per cent of the country’s landscape. And Germany is already contending with some of the highest electricity prices in the world, a source of consternation for domestic manufacturers seeking to remain globally competitive.

This was the daunting context in which the government convened its commission for the coal exit—Kohleausstieg—in June, 2018. Germany’s per-capita carbon emissions were still significantly higher than the E.U. average. Activists were demanding a fast response—hundreds of them had, since 2012, occupied Hambach Forest, a patch of woods in western Germany that was threatened by the expansion of a brown-coal mine. But the country needed to time the exit so that it could be assured of having enough power not only to replace both coal and nuclear energy but to add capacity, in order to handle the coming transition to electric-powered vehicles. (Tesla recently built a manufacturing plant outside Berlin.)

The thirty-one-member Commission on Growth, Structural Change, and Employment consisted of environmentalists and scientists, industry representatives and trade unionists, and residents and elected officials from the coal regions. It met regularly in Berlin and visited some coal towns. In January, 2019, after its final meeting, which ran until almost 5 A.M., it voted nearly unanimously in favor of a plan to exit coal by 2038. In July, 2020, the Bundestag passed a law with closure dates for various mines and power plants, and specific sums for compensation: 4.4 billion euros for the power companies, five billion euros for older workers to retire a few years early (separate funds would cover younger workers while they looked for new jobs), and, most important, forty billion euros for the mining regions, to help them with their economic transformation, a process known as the Strukturwandel.

It was a remarkable achievement, an example of postwar Germany’s consensus politics. “At a fundamental level, that all these different branches of society were able to come together around a coal exit is very significant,” Ingrid Nestle, a Green member of the Bundestag, told me. Climate-change experts in the U.S. looked on with admiration. “They got the environmental community, labor community, and business community together to hash it out,” Jeremy Richardson, an energy analyst and a West Virginia native formerly with the Union of Concerned Scientists, told me. “You have to get people together, and you have to invest.”

But it did not take long for the good feelings to fade. Environmental groups and Green Party leaders began arguing that the country needed to move up the exit date if it wanted to meet the European Union’s new, more ambitious goal of cutting emissions by fifty-five per cent from 1990 levels by 2030. In April, 2021, Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court ruled that the country’s existing climate efforts did not go far enough to stave off disaster. And, in July, heavy rains caused devastating flooding in western Germany, near Belgium. The floods killed at least a hundred and eighty people and destroyed entire towns, drawing greater attention to the possible effects of climate change.

As the election to replace Merkel got under way during the summer, climate change was central. Having sat through countless American Presidential TV debates where the subject was barely mentioned—and where politicians couldn’t even agree on whether climate change is real—I was astonished to see it take up twenty minutes in each of the three German debates that I watched, and to see the candidates toss around Klimaneutralität and Kohleausstieg as if they were household terms. The Social Democrats’ candidate for Chancellor, Olaf Scholz, agreed with his Green rival, Annalena Baerbock, on the urgent need to reduce carbon emissions. On Election Day, September 26th, the Social Democrats won more votes than Merkel’s center-right Christian Democrats, putting them in a position to form a government with the Greens and the pro-business Free Democrats.

The AfD saw its nationwide numbers sag, but, in the coal towns of Lusatia and the nearby regions of eastern Saxony, the Party did even better than it had four years earlier.

“You will watch a new, totally mind-blowing TV series, only to forget about it completely a couple months later.”

Cartoon by Drew Panckeri

I encountered an AfD voter at a wind-turbine factory in Lauchhammer, on the western edge of Lusatia. The Danish company Vestas had opened the plant in 2002, and it seemed to embody the ideals of the Energiewende: a century earlier, Lauchhammer had been home to one of the first brown-coal mines in the region, and now it was making the machinery of renewable power. But, a week before the election, Vestas announced that it was shutting down the factory, a decision widely attributed to the slowing growth of wind power in Germany. It will lay off the plant’s four hundred and sixty employees early this year.

I arrived at the factory one weekday evening at dusk, and waited in a light rain in a parking lot. After a while, a young man emerged, headed for his car. Cornell Köllner, a genial thirty-one-year-old, had worked at the plant for five years as a mechanic, advancing to a supervisory role. He enjoyed the work, and did not know what he would do next. The only other major employer in this part of Lusatia was B.A.S.F., the chemical company, which had a plant in nearby Schwarzheide that would soon be expanding into battery production. He could look for work outside the region, but he had recently bought a house, and he did not want to leave his family. “I’ve got to look for work here in the area,” he said.

The confounding nature of it all—shuttering a wind-turbine factory at a time when the country was supposedly ramping up renewable energy, and doing so in the region that was supposed to be targeted for extra assistance in managing the transition—had only confirmed for Köllner his preference for the AfD. “Not because of ‘Nazi,’ God forbid,” he said. “But because AfD is proposing something completely different.” I pressed him on what, exactly, that was, what the Party would do to help Lusatia or people like him, but he stuck to generalities. “They would change things,” he said. “They would really change things.”

Reluctance to leave in search of work elsewhere was widespread in Germany. “We work where we live,” Klaus Emmerich, the chief worker representative at the Garzweiler mine, in the western region, told me. “Where we live, that is our Heimat”—the German word that expresses something stronger than just “home” or “home town.”

Again, the echo was strong from U.S. coal regions, where residents, especially younger ones, constantly wrestle with the question of whether to stay or go. “It’s just home,” John Arnett, a marine veteran who worked for a closing coal-fired plant in southern Ohio, told me, in 2018. “I’ve been a bunch of different places, different countries. I’ve been across the equator. And now this is where I want to be, or I’d have stayed somewhere else. It’s the most beautiful place in the world, these hills.”

The people who remained often took offense at the economist’s or the pundit’s counsel that the only thing to do for regions that had lost their former economic rationale was to give people a bus or plane ticket out. In the U.S., the rate of people moving across state lines has in fact dropped by half since the early nineties, a trend attributed to, among other things, the cost of living in higher-opportunity cities and the breakdown of the traditional nuclear family, which leaves people dependent on extended family for child care or elder care.

The stay-or-go question is particularly sensitive in eastern Germany, because of the flight of younger people that occurred in the years after reunification. Die Zeit estimates that 3.7 million people, a quarter of the population of the former G.D.R., eventually left. One night, at a tavern in Hoyerswerda, I talked with Jörg Müller, a fifty-six-year-old man who worked at the B.A.S.F. plant, making paint for German car companies, and who had in his youth done cleaning jobs at the mine where his father worked as an engineer. Müller, who had brought up his children alone after his wife died young, of cancer, was worried about the impact that higher energy prices could have on B.A.S.F.’s prospects. But his main preoccupation was his grown children, who had left the area—one to study in Dresden, one to work in Kassel, in the former West Germany. I asked him how often he saw them. “Once or twice a year,” he said.

To coal’s opponents in Germany, such laments about home-town decline are undermined by the fact that the industry has been demolishing home towns for decades. The extent of the destruction is all the more striking in a culture that generally idealizes the village. Even amid all the devastation wrought by the coal industry in Appalachia—the mountaintop-removal mining, the coal-slurry spills—coal companies have not had to wipe entire towns off the map, as happens in Germany.

The week after the election, I travelled to the western brown-coal region, known as the Rhenish district, which has become the primary front for climate activists seeking to halt mining via direct action. They had succeeded in sparing Hambach Forest, and many had now moved to a new encampment, in a tiny hamlet called Lützerath that was on the verge of being claimed by the Garzweiler mine. Part of the hamlet had already been demolished by R.W.E., the German energy company that owns all the western region’s mines and power plants, which employ about nine thousand people. The only villager still living in Lützerath was a fifty-six-year-old farmer who was fighting the company in court and had welcomed more than a hundred activists to set up camp on his property. An R.W.E. spokesperson told me that the company “will continue to try to find an amicable solution with the landowner.” The spokesperson added that R.W.E. works closely with those affected by its plans and stands by its promises.

On October 1st, the day that the company was allowed to resume removing trees there, I cycled from the town of Erkelenz through fields of harvested sugar beets to reach Lützerath, where several dozen advocates had joined the occupiers to launch the defense. It made for a jarring juxtaposition: there were the remaining trees around the hamlet, festooned with tree houses and anti-coal banners; a narrow strip where the advocates were arrayed to speak; and, behind them, a vast pit, with excavators churning away at the edge of it. “If Lützerath falls, then the 1.5-degree limit falls,” Pauline Brünger, an activist with the youth movement Fridays for Future, said. “It lies in our hands—1.5 degrees is nonnegotiable. Lützerath must stand.”

I wandered into the encampment, where activists were breaking down pallets to build huts and more tree houses while others held an orientation session for new arrivals. Many wore balaclavas to try to hide their identities; others wore covid masks that served the same function. When I took pictures, a young woman came over to stop me.

Suddenly, a cry went up from the entrance to the encampment: two large excavators were approaching the hamlet. A couple of dozen activists marched down the road to block them. One of the drivers climbed out, saying that he and his colleague were only doing land-reclamation work on the older portion of the mine, and were coming to park their equipment for the weekend. The activists refused to let him through. “Hey, have a lot of fun sitting!” he called out angrily as he reversed back down the road.

Soon afterward, two large pickups approached from the other direction, loaded with concrete blocks and metal fencing, and rolled into the main assemblage of protesters; they were bringing the materials for an added security perimeter, and had taken a wrong turn, right into the enemy camp. The activists fell upon them and unloaded the blocks and fencing to build their own security perimeter, preventing access to one of the hamlet’s roads. The drivers sat helplessly in their cabs, watching the expropriation. Finally, a handful of police officers arrived and, after some cajoling, arranged for the materials to be returned and for the trucks to be allowed back out.

Nearby, five larger villages were also threatened with destruction by R.W.E. Most families had already sold their homes to the company and moved out, many of them to new developments on the outskirts of Erkelenz which had been built to house relocated families, and had even been named for the marked villages—Kuckum-Neu, Keyenberg-Neu, and so on. Tina Dresen, twenty-one, and her family were still holding out in Kuckum, and she told me how strange it had been to grow up in the shadow of Garzweiler and to see other villages falling to the bulldozers, one by one. “On the right side of my home was the hole, and life ended there,” she said. “I didn’t know anyone who lived there, and the bus stopped driving there, and the villages were destroyed there. I lived only to the left.”

She told me that some of the vacant homes in Kuckum were being used to house families who had lost their homes to the recent flooding. The irony was overpowering: people rendered homeless by a disaster likely exacerbated by climate change were now living in homes made available by the looming displacement of the coal mining that was contributing to climate change.

That evening, I rode my bike to Kuckum and found one of the displaced families. Anja Kassenpecher had been relocated to the village with her son, four cats, and two dogs, after the flooding destroyed her beloved half-timber house in the town of Ahrweiler. “What happened in the flood catastrophe, that was nature, and one couldn’t do anything against that,” she said. “But the dismantling of the coal here, one could do something about that.”

Cartoon by Roz Chast

In 1945, the victorious Russians removed a thirty-kilometre stretch of rail between Cottbus and the town of Lübbenau, to take back to the Soviet Union, one of many such claims made throughout eastern Germany. The rails were never replaced, and the single track in that stretch has meant that trains run between Cottbus and Berlin only once an hour—less than ideal by German standards. Part of the Strukturwandel’s forty billion euros will be used to replace the missing track.

But, toward the end of 2021, reports kept appearing in the local and national media of the questionable ways other portions of the fund were being put to use by federal agencies and by the obscure provincial councils that were overseeing much of the spending: a techno festival, a zoo, new streetcars in Görlitz. Coal defenders and opponents alike told me how wrong they thought it was to spend three hundred and ten million euros on a new branch of Germany’s public-health agency in an exurb of Berlin sixty miles from Cottbus, or millions more on the renovation of a cultural center in a town thirty miles from Dresden, far from the coal towns. In November, eleven mayors met to express their frustration with the spending decisions and to demand that communities closest to the coal mines get more of a say. “If it goes on like this, the pot will be empty,” Tristan Mühl, the mayor of the village of Krauschwitz, told me afterward. “The perspective of the community is missing.”

Part of the challenge for the appropriators was structural: under European Union rules, they were forbidden to use the money to subsidize new or existing businesses in the region. Instead, the discussion was of funding research institutes for renewable energy, including innovations in hydrogen power, that might eventually lead to job creation. René Schuster, a Cottbus-based representative of the environmental group Grüne Liga, told me that it was doubtful whether such ventures would ever come close to replacing the jobs that would vanish in the coal exit. “I doubt you’re going to get a boom in new jobs that will replace what you’re losing from coal,” he said. “That you’re going to get seven thousand jobs, that’s not going to happen.” But it was still wrong to think of the coal jobs as somehow sacrosanct, he added. “It’s often discussed as if coal workers have a fundamental right to their job. There’s no right to an income. You have a fundamental right to your property. Whoever gets relocated, their property rights are being encroached on. But whoever wants to live off that relocation, well, they have no fundamental right to that.”

After the election, Olaf Scholz and his counterparts in the Greens and the Free Democrats began negotiating the coal-exit terms for their coalition pact, including whether to move the 2038 date to 2030. Adding pressure was the concurrent climate summit in Glasgow, where a major focus was whether to mandate a global end to burning coal. The talk of an earlier exit prompted more consternation in Lusatia, where many viewed it as a breach of the commission’s compromise. “By 2030, little of this will have got started,” Christine Herntier, the mayor of Spremberg, said of the Strukturwandel.

Every day or two, I checked an app called Electricity Map, which shows the sources from which countries are drawing their electricity. Invariably, coal was Germany’s largest source, with wind a distant second or third. The plan was to use natural gas as a bridge to the expansion of renewables, but that would require building more gas power plants, fast, and would also mean making Germany even more dependent on Russia, one of its biggest gas suppliers. Recently, Russia built a controversial pipeline to Germany through the Baltic Sea, called Nord Stream 2. As a last resort, Germany could buy nuclear-based electricity from France, which has remained staunchly committed to nuclear power, or coal-fired electricity from Poland, but not without hypocrisy, given its own disavowal of both sources.

On November 24th, the coalition released its governing agreement, which called for “ideally” moving up the coal exit to 2030. The rhetorical wiggle room satisfied neither side, and reflected the bind in which the country has found itself. Germany had set out to be an example of how to relinquish the dirty-energy source that had enabled modernity. It had developed a clear timetable, and it had agreed on significant compensation, recognizing that there was a societal obligation to people whose livelihood was being shut down as a matter of policy. The process was undoubtedly superior to what was playing out at the same time in the U.S., where the Biden Administration’s plan to spend five hundred and fifty-five billion dollars on incentives to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions, as part of the sweeping Build Back Better package, was foundering, shy of majority support in the Senate.

But Germany was also at risk of being an unintended example, one that could be cited by opponents of the imposition of emissions reductions. (A recent Wall Street Journal editorial was titled “Germany’s Energy Surrender: Rarely has a country worked so hard to make itself vulnerable.”) The exit from nuclear power was leaving the country much less space to maneuver as it tried to move away from coal. And the lack of transparency and forethought with the regional spending undermined the purpose of the compensation: to convey that, this time around, the rest of the country really did care what happened to its left-behind places.

On my final visit to Lusatia, in November, I met Lars Katzmarek, an employee at LEAG, the coal company, at a coffee shop in Cottbus. Katzmarek, who is twenty-nine, oversees telecommunications at the mines, a job he loves and hopes to keep until things shut down. He was not drifting to the AfD: he is a loyal Social Democrat, he believes in climate change, and he even met with some Fridays for Future activists in 2019.

But he understood the feeling of betrayal in the region. His parents both worked in Braunkohle. His mother lost her job in the nineties and never found steady work again. Cottbus has experienced the third-highest rate of departures to western Germany of any city in the former G.D.R., and nearly all of Katzmarek’s high-school friends have left town. It was hard now to watch a new wave of people leaving the company and the region because they didn’t believe the promises of the Strukturwandel. “The sorrow is gigantic,” he said.

Katzmarek composed rap music on the side, and he had recently produced a single about Lusatia’s plight which included clips of him singing atop one of the turbines at the Vestas plant—before the news came of its closure. “For politics to win back the trust of the people, it has to finally be the case that things are carried out the way they said they would,” he said. “This is the big chance to win back trust.”

What you couldn’t have was a coal exit that led to a decline in German industry because of higher electricity costs. “You can’t have deindustrialization in Germany,” he said. “Industry means prosperity. A loss of prosperity would be absurd. If other countries look to see how Germany has fared, and they see deindustrialization and a loss of prosperity and the people growing discontent and populism gaining a new foothold, who would follow our example?”

His nuanced tone made me wish that we had more time to talk. But he had to catch the hourly train to Berlin, to visit one of his many friends who had left Lusatia.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.