Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The highest accolades often go to those who died for their country. But when a war is based on deception with horrific results, as became clear during the massive bloodshed in Vietnam, realism and cynicism are apt to undermine credulity. “War’s good business so give your son,” said a Jefferson Airplane song in 1967. “And I’d rather have my country die for me.”

Government leaders often assert that participating in war is the most laudable of patriotic services rendered. And even if the fighters don’t know what they’re fighting for, the pretense from leadership is that they do. When President Lyndon Johnson delivered a speech to U.S. troops at Cam Ranh Bay in South Vietnam, he proclaimed that “you know what you are doing, and you know why you are doing it -- and you are doing it.”

Five decades later, long after sending U.S. troops to invade Panama in 1989 and fight the 1991 Gulf War, former President George H.W. Bush tweeted that he was “forever grateful not only to those patriots who made the ultimate sacrifice for our Nation -- but also the Gold Star families whose heritage is imbued with their honor and heroism.” Such lofty rhetoric is routine.

Official flattery elevates the warriors and the war, no matter how terrible the consequences. In March 2010, making his first presidential visit to Afghanistan, Barack Obama told the assembled troops at Bagram Air Base that they “represent the virtues and the values that America so desperately needs right now: sacrifice and selflessness, honor and decency.”

From there, Obama went on to a theme of patriotic glory in death: “I’ve been humbled by your sacrifice in the solemn homecoming of flag-draped coffins at Dover, to the headstones in section 60 at Arlington, where the fallen from this war rest in peace alongside the fellow heroes of America’s story.” Implicit in such oratory is the assumption that “America’s story” is most heroic and patriotic on military battlefields.

A notable lack of civic imagination seems to assume that there is no higher calling for patriotism than to kill and be killed. It would be an extremely dubious notion even if U.S. wars from Vietnam to Afghanistan and Iraq had not been based on deception -- underscoring just how destructive the conflation of patriotism and war can be.

From Vietnam to Iraq and beyond, the patriotism of U.S. troops -- and their loved ones as well as the general public back home -- has been exploited and manipulated by what outgoing President Dwight Eisenhower called the “military-industrial complex.” Whether illuminated by the Pentagon Papers in 1971 or the absence of the proclaimed Iraqi weapons of mass destruction three decades later, the falsehoods provided by the White House, State Department and Pentagon have been lethal forms of bait-and-switch.

Often lured by genuine love of country and eagerness to defend the United States of America, many young people have been drawn into oiling the gears of a war machine -- vastly profitable for Pentagon contractors and vastly harmful to human beings trapped in warfare.

Yet, according to top officials in Washington and compliant media, fighting and dying in U.S. wars are the utmost proof of great patriotism.

We’re encouraged to closely associate America’s wars with American patriotism in large part because of elite interest in glorifying militarism as central to U.S. foreign policy. Given the destructiveness of that militarism, a strong argument can be made that true patriotism involves preventing and stopping wars instead of starting and continuing them.

If such patriotism can ever prevail, the Fourth of July will truly be a holiday to celebrate.

Norman Solomon is the national director of RootsAction.org and executive director of the Institute for Public Accuracy. He is the author of a dozen books including War Made Easy. His latest book, War Made Invisible: How America Hides the Human Toll of Its Military Machine, was published in June 2023 by The New Press.

Reader Supported News is the Publication of Origin for this work. Permission to republish is freely granted with credit and a link back to Reader Supported News.

READ MORE  Vehicles travel along Interstate 95 under the Pioneer Trail Road bridge on Wednesday. (photo: Jacob M. Langston/The Washington Post)

Vehicles travel along Interstate 95 under the Pioneer Trail Road bridge on Wednesday. (photo: Jacob M. Langston/The Washington Post)

Mori Hosseini, who donated a golf simulator to the governor’s mansion, championed a new exchange on Interstate 95 that feeds into his housing and shopping center project

The decision by the Florida Department of Transportation to use money from the 2021 American Rescue Plan for the I-95 interchange at Pioneer Trail Road near Daytona Beach fulfilled a years-long effort by Mori Hosseini, a politically connected housing developer who owns two large tracts of largely forested land abutting the planned interchange. The funding through the DeSantis administration, approved shortly after the governor’s reelection, expedited the project by more than a decade, according to state documents.

Hosseini plans to develop the land — which includes a sensitive watershed once targeted for conservation by the state — into approximately 1,300 dwelling units and 650,000 square feet of nonresidential use, including an outdoor village shopping district. He has called the Woodhaven development, which has already begun construction, his “best project yet” and promised to pull out all the stops for its success.

“With or without the interchange, we would have built Woodhaven there, but it certainly helps,” he told the Daytona Beach News Journal in March 2019.

Government documents obtained by The Washington Post through open-records requests show a steady relationship between DeSantis and Hosseini in recent years. The governor’s office occasionally received requests for DeSantis to attend events or support proposals from Hosseini, and DeSantis extended invitations to Hosseini in return for events in Tallahassee.

Hosseini helped DeSantis arrange a round of golf at Augusta National Golf Club in Georgia in 2018, according to the Tampa Bay Times. A year later, Hosseini donated a golf simulator that retails for at least $27,500 to the governor’s mansion, according to records previously obtained by The Post. In the 2022 campaign cycle, companies controlled by Hosseini gave at least $361,000 to political groups that benefited the DeSantis reelection campaign, according to state campaign finance records. Hosseini’s plane has been repeatedly used by DeSantis, according to a Post analysis.

A DeSantis spokesman, Jeremy Redfern, published on Twitter on Wednesday night, before this story published, emails from a Post reporter seeking comment.

“You are trying to make an accusation to play ‘gotcha,’” he wrote in one email to The Post, after he had been asked whether the governor had spoken to Hosseini about the Pioneer Trail project or advocated for its funding.

He referred questions to Jessica Ottaviano, the communications director for the state transportation department, who also did not directly respond to questions about DeSantis’s or Hosseini’s involvement in the decision to fund the project.

She said in a statement that state transportation planners “determined and prioritized projects that had local support and were production ready to use” the federal covid funds. The Pioneer Trail project has been a priority for some local officials for decades.

“[T]his enhanced interchange project will help keep up with Florida’s growing population,” she said. “Florida currently leads the nation in net in-migration with a majority of these new residents moving to Central and Southwest Florida.”

Hosseini did not respond to multiple requests for comment by phone and email.

DeSantis, who campaigned in 2018 on a pledge to “drain the swamp in Tallahassee,” reported a net worth of about $320,000 in 2021, according to public filings. He has subsequently relied more on benefits from wealthy supporters than his predecessor, current Sen. Rick Scott (R-Fla.), who was independently wealthy and flew on his own private plane.

DeSantis, a Republican candidate for president, initially criticized the American Rescue Plan in March 2021 as “Washington at its worst,” arguing that much of the money “had nothing to do with covid” and that politicians were using the bill “as a Christmas tree” on which to hang pet projects.

But since the money arrived in Florida, he has used it for favored projects unrelated to the pandemic, including using interest from the federal funds to pay for the flight of mostly Venezuelan migrants from Texas to Martha’s Vineyard last year. DeSantis called on the state legislature to direct about $1 billion in covid relief to transportation projects in March 2021.

State transportation leaders notified local officials about the decision to use covid relief money for the interchange during a public meeting on Nov. 30, 2022, three weeks after DeSantis’s reelection.

The $126 million interchange budget — which includes about $34 million in funding from other federal, state and local sources — covers purchasing land for right of way, along with construction costs, records show. It also includes funds to build partial access roads near the interchange onto Hosseini’s property, a feature that was not in the 2021 design plans but appeared in 2022 plans, according to public records.

Ottaviano said the state’s decision to pay for the partial roads into the Woodhaven development was made in coordination with local governments and agencies. “Future connections to Pioneer Trail were considered when we applied for the permit to ensure adequately sized ponds and designs for the existing and future drainage patterns in the area of the proposed interchange,” she said.

The new exits on Interstate 95 will allow highway travelers to more easily access Hosseini’s development rather than having to use highway exits four miles to the north and three miles to the south, according to design plans. Other developments south of the interchange are also expected to benefit from the new off-ramps.

John Tyler, the Florida transportation secretary for the central district, told local officials at a Jan. 25 meeting of local planners that federal pandemic relief money will be used for three projects in Volusia County, with most of the funds going to the Pioneer Trail interchange because it was “ready for construction.”

He credited state leaders in Tallahassee in making the pandemic relief money available.

“The 2021 legislature asked the department to identify projects for that funding that they prioritized,” Tyler told the officials at the meeting. “It was adopted in the 2022 legislature into the department work program, signed off by the governor and we are here today to continue moving forward.”

The local planning authority approved the state’s plans at the meeting over the objections of Jeff Brower, the Republican chairman of the Volusia County Council, who argued that the interchange would encourage the development of sensitive wetlands that feed into nearby Spruce Creek.

“There are areas that just shouldn’t be developed,” Brower said at the meeting, referring to the Woodhaven project. “The pollution that we’re creating to our entire state’s water system is clearly resulting from the decisions that we’re making to develop essential wetlands and watersheds.”

Former Republican governor Charlie Crist, who ran as a Democrat against DeSantis last year, also opposed the interchange, arguing during his 2022 campaign that Hosseini’s development would damage the local watershed. Hosseini sold part of his land to the government about a decade ago for conservation.

“This is a project Florida does not need and is one the community does not want — the state should not keep pushing for it,” Crist wrote in a 2022 opinion piece for the Daytona Beach News-Journal. “Powerful developers want the interchange so they can more easily build on nearby land they own.”

One prominent local supporter of the project is Hosseini’s sister, Maryam Ghyabi-White, a regional transportation consultant at Ghyabi Consulting, who DeSantis reappointed in 2021 to the St. Johns River Water Management District Governing Board. The water district, at the staff level, provided a permit for the project, without direct input from the board, she said.

She travels frequently to Tallahassee to push for local funding for transportation programs, working as a paid consultant on other interchange expansion plans along I-95. She said in an interview that the Florida Department of Transportation directed federal money to the Pioneer Trail interchange because “it was the only interchange in Volusia that design was ready,” not because of any intervention from DeSantis. The federal funds would have gone to a Tampa project if local officials had rejected the funds, she said.

At the Jan. 25 meeting, she spoke in favor of the project, calling her brother the “elephant in the room” and saying the project was needed to relieve traffic congestion at nearby interstate exits. She said in an interview that she does not have a business relationship with her brother and was not paid to consult on the Pioneer Trail interchange.

“It has nothing to do with family,” she said of her support for the Pioneer Trail exits on I-95. “His project has been approved. He does not need to have this interchange.”

The ethics manual of the executive office of the governor says employees “may not accept a benefit of any sort when a reasonable observer could infer that the benefit was intended to influence a pending or future decision of the employee, or to reward a past decision.” It specifically bans gifts to state employees from “parties who have pending matters awaiting decision by the state.”

However, the rules do not bar in-kind donations of private plane travel for political functions or campaign contributions. Hosseini’s purchase of a golf simulator for the cabana at the governor’s mansion was approved by a state attorney because it was given as a loan to the mansion, not to DeSantis personally, according to documents obtained by The Post.

DeSantis reappointed Hosseini to the University of Florida Board of Trustees during his first term in office. In 2019, Florida first lady Casey DeSantis took a private jet owned by Hosseini to announce a mental health initiative outside Jacksonville, Politico reported. Ron DeSantis appears to have taken a private plane owned by one of Hosseini’s companies to a February fundraiser hosted by his political action committee in Miami, according to flight-tracking data and campaign finance disclosures.

A person familiar with DeSantis’s operation, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to describe private information, said the governor’s team would call Hosseini regularly because he would usually provide his plane with late notice.

“They had a long, close relationship, and his plane was nice — it was a comfortable plane,” this person said.

A review of more than 2,700 pages of documents from 2020 and 2021 — given to The Post in response to a public records request — show a working relationship between the two men, but no mention of the Pioneer Trail interchange.

They show Hosseini recommending someone for a position on the University of Florida Board of Trustees, calls on DeSantis’s schedule with the developer and the appointment of Hosseini’s wife to a different board in 2019. They also include invites from the governor’s office for Hosseini to attend events, such as receptions at the governor’s mansion and the State of the State address. Hosseini was also involved in transportation projects as part of Space Florida, the state’s aerospace finance and development authority, where he serves on the board of directors with DeSantis.

Stephan Harris, a project manager at the River to Sea Transportation Planning Organization, said construction on the interchange is expected to begin early next year, with completion in 2025.

Local opponents of the plan are still hoping to stop the project.

Several groups have challenged in state court the permit for the project given by the local water management district. They argue that the project plans fail to fully consider the secondary and cumulative impacts of the exchange.

“It is the zombie interchange that just won’t die, despite being fought back several times before,” Save Spruce Creek founder Derek LaMontagne, who has been leading local opposition to the project, said in a statement. “Spruce Creek and its nature preserve are idyllic treasures that need to be protected.”

READ MORE  Michael Jenkins (right) with his mother, Mary Jenkins, and one of his counsels, attorney Trent Walker at a press conference. (photo: Kayode Crown)

Michael Jenkins (right) with his mother, Mary Jenkins, and one of his counsels, attorney Trent Walker at a press conference. (photo: Kayode Crown)

One of the men was nearly killed when an officer put a gun in his mouth and pulled the trigger, the lawsuit says.

The two men, Michael Jenkins, 32, and Eddie Parker, 35, filed the $400 million federal lawsuit against the Rankin County Sheriff's Department this month. The lawsuit describes the deputies’ alleged actions as “one of the worst and most bizarre incidents of police misconduct in United States history.”

“Due to recent developments, including findings during our internal investigation, those deputies that are still employed by this department have all been terminated,” Sheriff Bryan Bailey said Tuesday, reading from a prepared statement. The department declined to say how many deputies were fired.

“We understand that the alleged actions of the deputies have eroded the public’s trust in our department,” added Bailey, who is named in the lawsuit. “Rest assured that we will work diligently to restore that trust.”

Malik Shabazz and Trent Walker, attorneys for the two men, did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The FBI, the Justice Department and the U.S. attorney’s office for Southern Mississippi have opened a federal civil rights investigation.

Rankin County, one of Mississippi’s most populous counties, sits just across the Pearl River from Jackson, the state capital. Its population is 74% white and nearly 23% Black, according to the 2022 census. It abuts counties with large Black populations in a state that has long contended with a violent racial history.

The incident comes in a national reckoning over officers' use of excessive force, with particular scrutiny of the targeting of Black people. Recent shootings and beatings — including the deaths of Aderrien Murry in Indianola, Mississippi, and Tyre Nichols in Memphis, Tennessee — have again shined the spotlight on the issue after the country faced mass protests over the police killing of George Floyd in Minnesota in 2020.

Jenkins and Parker, who lived together at the time of the alleged assault, claimed in the federal lawsuit that deputies entered their home without cause or warning. The deputies beat, waterboarded, stunned, sexually violated and attacked them with racial slurs, the men say in the lawsuit.

The lawsuit alleges that the officers lobbed race-based insults at the men and angrily accused them of dating white women. They allegedly handcuffed and beat the men before they shot them with Tasers 20 to 30 times “in a sadistic contest with each other as to which Taser would be most effective when fired against these two victims,” according to court documents.

The officers then put the two men on their backs and poured water on their faces in an effort to waterboard them, the lawsuit claims, before they sexually assaulted them with a sex toy.

Multiple deputies put their guns to the men’s heads and threatened to kill them, the lawsuit says.

The evening ended when an officer put a gun in Jenkins’ mouth while he was handcuffed, according to the lawsuit. The gunshot allegedly shattered Jenkins’ jaw and severely lacerated his tongue. Several of Jenkins’ arteries were severely damaged, and he almost died, it says. He was then left alone to seek aid, the court documents allege.

While the sheriff’s department would not say how many deputies were relieved, a spokesperson said all those at the scene were fired after the internal investigation. The lawsuit said six officers were at the scene, though it named only three, including Deputy Hunter Elward.

Elward could not immediately be reached for comment Wednesday evening.

Elward, the officer accused of shooting Jenkins, was previously involved in the death of Damien Cameron, a 29-year-old Black man whose neighbor accused him of vandalism and called the police in 2021, the department has said.

A grand jury declined to indict Elward last year, citing a lack of evidence. Mississippi Public Broadcasting reported Monday that his family still sought justice nearly two years later.

The lawsuit said Bailey, the sheriff, “directly participates in acts of excessive force with the deputies he supervises and has been denied qualified immunity by this court” before it named multiple incidents in which his officers are alleged to have used excessive force.

Bailey said it remained his “privilege” to lead the department.

“I believe in my heart that this department remains one of the best departments in our state, and I am committed to doing everything in my power to keep this department on a correct path moving forward,” Bailey said, reading from his statement.

As reporters peppered him and a spokesperson with questions Tuesday at the end of the news conference, Bailey slowly and quietly edged toward the door. He stopped to say only that he would not resign and that he could not answer further questions.

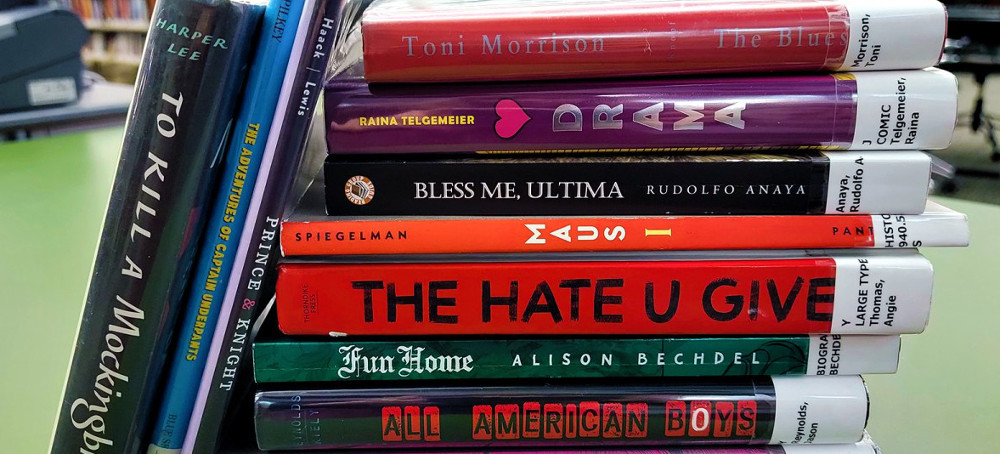

READ MORE  A selection of often-banned books that are available at the Library Center in Springfield. (photo: Shannon Cay)

A selection of often-banned books that are available at the Library Center in Springfield. (photo: Shannon Cay)

The restrictions are escalating into threats to defund public libraries.

At the library, patrons aren’t really expected to pay for anything; they can use the library’s free services, from unlimited wifi to job application support; and, of course, the thousands of books libraries hold are available to anyone.

But in recent months, Republican state lawmakers and local elected boards in states including Texas and Missouri have threatened to remove library funding as a way to control what materials patrons can and cannot access.

In August 2022, Missouri lawmakers passed a law establishing new standards that libraries must meet to secure state funding. The standards banned any material containing “explicit sexual content.” According to the law, children should not be able to access such content at school. A teacher or librarian who made such material available to children could face jail time and or a fine of $2,000.

Free expression advocates sounded the alarm, but legislators did not stop there. In February 2023, Republican House lawmakers in the state voted to remove $4.5 million of library funding from the state budget, in what was seen as retaliation to an ACLU lawsuit against SB 775. Though the funding was ultimately restored to the budget in a subsequent state Senate vote, librarians told Vox the threat still created a chilling effect.

The funding threats didn’t come out of nowhere. They are an outgrowth of book bans in public schools. When anti-book crusaders are unsuccessful at banning certain materials, lawmakers and board leaders escalate the fight and threaten to remove funding for libraries altogether.

In this episode of The Weeds, we dig into threats to defund public libraries and the growing movement to ban books at schools and libraries across the country. Cody Croan, an administrative librarian in Missouri and the legislative committee chair of the Missouri Libraries Association, talks about what he’s seen on the ground. Kasey Meehan, the program director for Freedom to Read at PEN America, tells us what this new level of censorship means for American democracy.

Below is an excerpt of our conversation, edited for length and clarity. You can listen to The Weeds on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get podcasts.

Fabiola Cineas

So the Missouri House stripped the funding, but the Senate did ultimately restore it. Is the threat actually gone?

Cody Croan

I actually don’t have an answer for you on that. So immediately, the threat is gone. I see no reason why the funding that got restored would be removed after the fact. So the only other step that I’m aware we’re waiting on is for the governor to sign all of the budget bills.

I sure hope that the conversations we had with legislators clarified what was going on and that there won’t be this initial reaction to just straight-up remove our funding.

I do think that we could see some other legislation that surrounds this idea of no longer trusting their libraries to ethically provide materials to their communities. Those are things that I’m going to be watching for.

And the thing that I have to go back to is these libraries were put together and voted on initially. Maybe they might have been put together 50-plus years ago, so by a whole other generation. But they have remained in place. They were voted by the people to be put together. They voted to have a tax to support that library. And then the state decided that it was important for the state to also provide some funding to the state’s libraries, because if a community recognizes the importance of a library within itself, the state recognizes that that is important as well. The state won’t start a community library for them, but it will support them. And that’s important to know. And that is in our state constitution, that library funding is provided for a library that is created within a community.

Fabiola Cineas

Can you just talk about the connection between book bans that are happening in school classrooms, in school libraries, and how they are connected to what we see the state legislature doing in Missouri?

Cody Croan

Sure. The book bans are specifically connected to that Senate Bill 775 that got passed last year; they are the schools’ response to getting back to interpreting what the intent behind the law was. And so you see several school districts out in St. Louis, I know one here near the Kansas City area, that have removed books. I don’t know the specifics of them, but I can imagine it’s not too far off base to say that someone came to the school with a list of books and a complaint saying that they disagree with this book being on their shelves.

With the law in place, last year, the schools most likely saw that it was better to remove the materials first and to evaluate them later than to put any of their employees or any organizations that are associated with them at risk of having this law applied to them.

But at the end of the day, when you start removing materials that you brought into the collection based on your collective development policy, which I’m certain that schools have — those school libraries have their collection development policies — if you have a policy on that, you need to stick to your policy. Otherwise, you’re making exceptions off the cuff and at the behest of the loudest voice. And when you listen to the loudest voice, it’s not always the best for everyone you’re serving. And when you serve a large community or even a small community of students, they themselves are diverse. And it’s important to recognize that you need to have something in your collection for everyone.

You’ll see schools say, well, if we remove it from the school library, they can still access it from the public library. Again, the problem is can they actually get to the public library to access that material? That’s not a substitute, because there are all sorts of other barriers, whereas [when] they’re at school, they have the opportunity to visit their library there. They have to go to school legally. They’re required to go to school and get an education. So having the materials that they can see themselves in is important for schools to fulfill and make available as well.

Fabiola Cineas

So let’s talk numbers. How many book bans have you all tracked, whether you want to talk about 2023 or in the past two or three years?

Kasey Meehan

We at PEN America have been tracking instances of book bans in public school and school libraries. The other folks, like the American Library Association, are looking at books that are being challenged in public libraries. But for PEN America ... since 2021, we’ve been tracking instances of book bans. And we do see kind of continuous increases in the books that are being challenged and removed from our public schools.

So in the first half of this school year, which our most recent report speaks to, we counted over 1,400 instances of book bans. And for PEN America to record a book ban, there has to be some sort of public, publicly accessible data out there. So either it’s been reported locally by journalists or it’s been put on a district website that’s publicly available.

So this idea that we always say we’re likely undercounting this quite significantly and that there are likely many books that aren’t even being publicly reported for us to record.

The thing that I think doubles down on that alarming number is within those instances of book bans. That’s about 800 unique book titles.

So there are 800 books across the country in just the first half of the school year that are being deemed, as, you know, no longer appropriate or, have been removed from, you know, circulation as part of this movement.

Over the last year and a half since we started tracking book bans, we’ve seen, you know, about over 4,000 total instances of book bans from fall 2021 through fall 2022.

We’ll have another kind of end-of-the-year report, which will look to this entire school year. And our preliminary sense is that we will continue to see increased and high-end numbers of book bans.

Fabiola Cineas

So I feel like a lot of this conversation is about, on a foundational level, just American society. What kind of country do we want to create for children, and what do we want them to have access to in the process? So what would you say is the connection between books and reading and democracy more broadly? And then how are these book bans threatening those connections?

Kasey Meehan

I think we see the efforts to ban books as deeply undemocratic. That book banning imposes restrictions on students and families based on the preferences of a few. ... I speak to this idea that it’s a coordinated movement and within that it’s really a vocal minority here, that we’re not talking about everybody. A majority of folks disagree with book banning. I think a majority of even parents would see that they would like to make decisions for their own kid, but not necessarily impose their views on everyone’s child who’s in a given public school. So I think what we see is undemocratic. I think we also see the way in which schools, again, are intended to serve the educational process by making knowledge and ideas available and ensuring that there are books available regardless of personal or political ideologies.

So, moving forward, I think we would love to see a place where all students have that freedom to read and the freedom to access a diversity of views and stories, and to see themselves and to see others with different lived experiences reflected in books. That is our hope, is that we can kind of bring us back to a place where that freedom to read, that freedom to learn, is really centered in these conversations and is brought back to public schools and other institutions that serve that intended goal.

READ MORE  An intersection near Brownwood Park on Saturday where a stop sign has been modified in opposition to the Atlanta Public Safety Training Center that protesters refer to as 'Cop City,' in Atlanta. (photo: Jim Urquhart/NPR)

An intersection near Brownwood Park on Saturday where a stop sign has been modified in opposition to the Atlanta Public Safety Training Center that protesters refer to as 'Cop City,' in Atlanta. (photo: Jim Urquhart/NPR)

"I was released on day 90, which is the basically the last day that they could legally keep me incarcerated without an indictment," Harper said. "And I'm still unindicted as of now."

The controversy over the planned Atlanta Public Safety Training Center — which opponents have dubbed "Cop City" — has been growing for two years. Spearheaded by a private organization, the Atlanta Police Foundation, it would site a state-of-the-art facility on 85 acres of land that the city acquired a century ago to use as a prison farm. Proponents say the project is badly needed to replace the Atlanta Police Department's dilapidated training facilities. But what started as a local debate has ballooned into a flashpoint around several issues with national resonance.

"Our state affiliate in Georgia and we at the national office have been watching what's been happening very, very closely," said Hina Shamsi, director of the ACLU's National Security Project. "What's been happening with Cop City is a stark demonstration of how overbroad state domestic terrorism laws, like Georgia's, can be used to disproportionately punish people, including protesters who express political beliefs."

Law enforcement officials claim demonstrators have been violent

According to the National Conference on State Legislatures, Georgia, New York and Vermont are the only states with laws about "domestic terrorism" or a "domestic act of terrorism." But many more states have terrorism statutes that further criminalize acts that are intended to "influence the policy of government" by "intimidation or coercion." To some, these statutes leave too much room for abuse.

"They really are a political instrument," said Lauren Regan, an attorney and executive director of the Civil Liberties Defense Center. "There are already numerous criminal statutes that would adequately prosecute the alleged criminal act, [such as] murder, assault, battery, menacing. There's already a ton of crimes that could cover this."

Law enforcement officials in Georgia say that demonstrators have been violent. At a January press conference following Terán's killing, Georgia Bureau of Investigation Director Michael Register said that Terán had fired the shot that injured an officer. Five months later, however, the GBI still has not released results of its investigation. Register and the head of Atlanta's Police Department have also claimed that activists have committed crimes including arson, assault, intimidation, using explosives, throwing rocks at officers and setting booby traps. The GBI declined requests for an interview, and APD referred questions about the domestic terrorism charges to the GBI.

But so far, none of the 42 defendants have seen evidence or specific charges alleging that they engaged in those acts. While they were accused of domestic terrorism in their arrest warrants, indictments are still forthcoming. This is true even for individuals who were detained in December.

"I don't think they really had a lot of focus in getting a conviction under that [domestic terrorism] statute," said Regan. "I think they were using it to scare people into submission."

Some GOP leaders in Georgia have boosted the narrative that the opposition movement comes from other states

To Alex Papali, another defendant in this case, the way that law enforcement agencies have targeted mostly non-Georgia residents with the domestic terrorism label has felt clearly political. Papali was at the music festival in the forest in March. He said when word got around that police had arrived, panic set in. He said officers detained anyone they were able to catch.

"It was just totally arbitrary and random," Papali said." But at one point they asked people where they're from and they separated all the Georgia residents from all the out of town folks... and then they let them leave."

Papali, a Massachusetts resident, was among those taken to DeKalb County Jail and labeled as a domestic terrorist.

"It couldn't have been more transparent that they were trying to create this narrative of 'outside agitators' coming in to disrupt the peaceful community," he said, "when the reality was there was a lot of local residents who also were supporting this this event."

Some Republican elected leaders in Georgia are amplifying the narrative that the opposition movement is highly organized and from other states. In an interview on WANF-TV, Attorney General Christopher Carr stated without a trace of doubt: "If you come to this state, engage in acts of violence to destroy infrastructure and property with the intended effect of changing public policy, it is a domestic terrorism charge." Carr's office did not respond to requests for interview.

But in Atlanta, a city that considers itself the cradle of the Civil Rights movement, this framing feels familiar.

"Dr. [Martin Luther] King [Jr.] was labeled an outside agitator at some point and he was born right here in the city of Atlanta, just like I am," said Rev. Keyanna Jones, an organizer with Community Movement Builders and the Faith Coalition to Stop Cop City.

Until recently, Jones lived right next to the proposed training facility site, but moved away because the Atlanta Police Department currently uses part of it for target practice. Jones said the sound of gunfire throughout the day was taking a toll on her young son. But even though she has left the city of Atlanta, she continues her activism on behalf of her neighbors and allies in the movement.

"I have never seen repression like this before. This is something that I did not think I would see in modern times," Jones said. "What the state of Georgia is trying to do is say that protest is not legal, that protesting is wrong. That if you go against me, then you're going to be punished."

Jones and others have increasingly felt this to be true in light of the recent arrests of three bail fund workers, under charges of charity fraud and money laundering. The arrest warrants in those cases allege that the fund was channeling money to Defend the Atlanta Forest, characterized in the document as "a group classified by the United States Department of Homeland Security as Domestic Violent Extremists."

However, DHS does not classify or label domestic extremism groups, and there is no federal law criminalizing domestic terrorism, because of first amendment concerns. These defendants, too, are awaiting formal charges in an indictment and so have not had an opportunity to respond to the allegations.

To many who believe the domestic terrorism charges are baseless, there are signs that prosecutors may, in fact, be struggling. First, there is the failure to indict the defendants. And on Friday, DeKalb County District Attorney Sherry Boston abruptly announced that her office was withdrawing from prosecuting the case, leaving the state AG as the sole prosecuting jurisdiction.

"It is clear to both myself and the attorney general that we have fundamentally different prosecution philosophies," Boston said in an interview on WABE-FM. Her office declined to be interviewed by NPR.

But even if the charges are dropped, or a grand jury fails to indict, some defendants worry that the toxic label of "domestic terrorist" may stick.

"The first weight of that came to me when... my mug shot was posted up on some fascist Twitter [account], and I had to have the conversation with my parents that they might start receiving death threats," said Vienna Forrest, who was arrested in December. "That's going to be something that'll follow me for a long time."

READ MORE  Local residents stand next to an apartment building damaged by a Russian military strike in Sloviansk, eastern Ukraine, April 14, 2023. (photo: Reuters)

Local residents stand next to an apartment building damaged by a Russian military strike in Sloviansk, eastern Ukraine, April 14, 2023. (photo: Reuters)

European Union leaders are grappling with that question at a meeting in Brussels Thursday.

The World Bank estimates Ukraine will need at least $411 billion to repair the damage caused by the war. And the EU and its allies are determined to make Russia foot part of the bill.

One idea put forward in the EU is to draw off the interest on income generated by Russian assets while leaving the assets themselves untouched.

This approach would probably deliver about €3 billion ($3.3 billion) a year, according to Anders Ahnlid, the director general of the Swedish National Board of Trade and head of the EU working group looking into frozen Russian assets.

“It’s the best way of using these assets in accordance with EU and international law,” Ahnlid told CNN, noting that was also the view of lawyers at the European Commission, which has promised to propose a way to tap frozen Russian assets within weeks.

But some EU member states, and the European Central Bank (ECB), have concerns that it could shake confidence in the euro as the world’s second biggest reserve currency. The EU has been at pains to contrast the illegality of Russia’s invasion with its own strict adherence to the rule of law.

“We have to respect the principles of international law,” said a senior EU diplomat, who requested anonymity because he is not authorized to discuss closed-door meetings. “It’s a matter of reputation, of financial stability and trust.”

The ECB declined to comment.

How it would work

After the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February last year, EU and Group of Seven countries imposed unprecedented sanctions on Russia, freezing nearly half of its foreign reserves — some €300 billion ($327 billion) — among other measures.

Around two-thirds of that, or €200 billion ($218 billion), sits in the EU, mostly in accounts at Belgium-based Euroclear, one of the world’s largest financial clearing houses.

Euroclear plays a crucial role in global markets, settling cross-border trades and safekeeping more than $40 trillion in assets.

The group said in April that cash on its balance sheet had more than doubled over the year to March to stand at €140 billion ($153 billion), boosted by payments associated with frozen Russian assets, including bonds.

Ordinarily, these payments would have been made to Russian bank accounts, but they have been blocked as a result of sanctions and are now themselves generating vast amounts of interest.

Euroclear routinely invests such long-term cash balances and, in the first quarter, it recorded €734 million ($802 million) in interest earned on cash balances from sanctioned Russian assets.

The plan proposed by the EU working group would involve using a special levy to collect the windfall interest income made by Euroclear from frozen Russian assets, which would then be paid into the EU budget for the reconstruction of Ukraine.

Speaking on the sidelines of Thursday’s EU meeting, Latvia’s Prime Minister Arturs Krišjānis Kariņš said frozen Russian assets were “low-hanging fruit.”

“We need to find a legal basis to utilize, mobilize these assets to help… pay for the damage Russia is causing in Ukraine,” he said.

But one senior EU official warned of unintended consequences, such as causing other countries or investors to worry about the safety of their assets in Europe.

“Those who have money might think ….’what if one day, I’m on the list,’” the official, who also requested anonymity because the discussions are private, said Wednesday.

One way to reduce risks to the EU would be to coordinate action with the G7. “I think discussion at the G7 is quite key,” the official added.

Ahnlid echoed this, noting that many EU member states had stressed the importance of the bloc taking steps “in tandem with G7 partners.”

READ MORE  Air conditioning, purifiers, and even box fans can help. (photo: Michael Robinson Chávez/The Washington Post)

Air conditioning, purifiers, and even box fans can help. (photo: Michael Robinson Chávez/The Washington Post)

Air conditioning, purifiers, and even box fans can help.

That’s because the air quality inside buildings is a direct reflection of outdoor air quality, said Ian Cull, an environmental engineer and air quality expert based in Chicago. Few buildings (with the notable exceptions of some health care and laboratory settings) are hermetically sealed to prevent them from sharing any air with the outdoors. So people breathing air inside eventually end up breathing whatever’s on the outside.

But not all buildings are created equal, and some HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) systems do a better job of maximizing air quality than others.

I talked to Cull about how to make the best of what you have during wildfire season. Whether you have central, in-unit, or no AC — and whether you have little or lots of resources to commit to cleaning the air in your house — there are things you can do to improve the quality of the air you and yours breathe.

How can I tell how good or bad my indoor air quality is?

You can buy a small handheld or indoor air quality monitor, but really, the best indication of your indoor air quality is outdoor air quality, said Cull. “When it’s really bad, yes, you can smell it,” he said. “But even when the sight and smell goes away, there’s going to be a period of time where outdoor air pollution is still exceeding standards.”

It would be great if you could use some measurement of different components of indoor air pollution to help determine how clean and safe your indoor air is. (During a wildfire, the chief pollutant you’d want to measure would be soot particles — technically called “particulate matter.” But at other moments, it’s also important to minimize volatile organic compounds, or VOCs, which are compounds that can be toxic to human health.)

However, while there are tons of home-use air quality monitors on the market, they don’t all work as well as advertised — and it can be really hard to determine which ones do. One 2019 study showed that home monitors made by Dylos and Purple performed almost as well as professional ones.

But for most people, Cull recommends using the AirNow app or site to determine the air quality in your region, and assuming your indoor air quality more or less approximates outdoor air quality.

Then, he said, work to prevent outdoor air from flowing inward — and clean the air that’s inside.

How can I keep outdoor air outside — and indoor air inside?

The three most important strategies in reducing the inward flow of outdoor air are blocking its routes inward, turning off indoor exhaust systems, and minimizing ventilation.

1. Block routes for outside air to keep it from coming in — within reason. That means closing windows and doors, and, where it’s relatively easy to do so, sealing visible crevices.

Cull said that caulking around drafty windows, or applying seasonal shrink-wrap window covering to prevent smoky air from getting in through unseen cracks, probably isn’t going to yield much additional protection. “Air finds its way in,” he said, and focusing your energy on other strategies like filtration (more on that below) is probably more effective.

But if you have a big gap to the outside that’s easily sealable with duct tape, throw some on there, he said.

2. Keep exhaust fans off. Differences in pressure between the inside and the outside are what determine how much outside air flows into your space. Exhaust fans — like the ones in bathrooms and on hoods over kitchen ranges — are designed to suck air out of the room, which creates an incentive for outside air to flow in. That’s normally a good thing, but in a smoky air situation, it’s the opposite of what you want.

3. Switch from ventilation to recirculation on any and all HVAC units. When the outdoor air is clean, we generally want it to replace stale indoor air pretty frequently. But when outdoor air quality plummets, we want to keep it out. Instead, we want to just recirculate the better-quality air that’s already inside our homes.

Doing that will look different depending on what your home uses for cooling the air — and on how much control you have over tweaking any central systems’ settings.

If you have central air, see if you can figure out how to close the fresh air intake ducts. These are generally openings on the outside of a building, often with a grill over them — and for someone not used to finding them, they can be hard to tell apart from other openings in the side of a building. Still, if you can find yours, closing them is a good first step.

If you have an in-unit (“window”) air conditioner, you likely have the option of bringing in outdoor air (often symbolized with wavy one-way arrows) or recirculating indoor air (which often is indicated with arrows running in an oval or circle). When the air outside is bad, opt to recirculate.

What are the best ways to clean my indoor air?

No matter how well-sealed your windows and doors are, some outdoor air is making it inside — and with it, the particulate matter that makes smoke such a potent irritant to eyes, noses, and throats. Continuously running your indoor air past a filter, and using the air filter with the smallest holes your system can move air through, helps keep your air as clean as possible.

Again, this will look different depending on your home’s HVAC system.

For people with central air conditioning, explore using a filter with a MERV (minimum efficiency reporting value) of 13 or higher (the range is 1 to 16). The higher a filter’s MERV rating, the smaller the holes in the filter — and the better it is at catching soot particles of all sizes. However, an air conditioning unit works harder to move air through a very fine filter than it works to move air through a filter with big holes. Older units in particular might struggle with filters of higher MERV ratings. So if you detect a noticeable drop in airflow from your home’s ducts after upgrading to a filter with finer holes, you might be stuck using a filter with bigger holes.

For people without central air conditioning who have forced-air heating (that is, it’s heated by warm air coming out of vents, rather than by a radiator or hot pipe that circulates steam), the options are pretty similar. Thermostats usually have two settings — one controlling the heat (often with at least two options, including “heat” and “off”), and one controlling the fan (with options “on,” “off,” and “auto”). Normally, in the summertime, the heat is set to “off” and the fan is set to “auto.” When the air gets smoky, you want to keep the heat off but turn the fan to auto. You also want to upgrade the filter in your furnace using the same considerations you would for an air conditioner.

If you’re using an in-unit (“window”) air conditioner, or not using any air conditioner at all, your best bet is using a free-standing air purifier to clean the air in each room. An in-unit air conditioner doesn’t typically have much filtration capacity, so as long as it’s set to recirculate air, its effect on indoor air quality is neutral.

Do I need a standalone air purifier? And if so, how do I choose (or make) one?

For those lucky folks who live in the best-case-scenario buildings — those with newer central air conditioning systems, with the option of upgrading their filters and closing their intake ducts — additional air filtration devices might not be necessary. An air quality monitor can help people in this situation decide whether they need more air purification help, said Cull. And some particularly high-risk people might reasonably choose to buy an air filtering unit just in case.

For those of us with more gaps in our HVAC systems’ capacity, the benefit of a standalone air purifier is more clear, said Cull. But it can be hard to tell the good from the bad or merely okay: The pandemic led to a flood of air filters and purifiers on the market, and some are better than others.

For the best objective insight on air purifier performance, Cull looks to the Association of Home Appliance Manufacturers’ Verifide site; Consumer Reports is also thorough, but paywalled, and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) also offers tips on choosing a product. He recommends putting one in each room and keeping it on full-time while air quality (which he assesses using the AirNow app or site) is low. (He also recommends avoiding ones with ionizers, which actually add pollutants like ozone to the air.)

Almost all air purifiers will remove the particulate matter that’s the most prominent pollutant in wildfire smoke. However, some also remove volatile organic compounds (VOCs, toxic gases and compounds that can also lead to health consequences). Air purifiers whose filters include an activated carbon (or “charcoal”) layer have this capacity.

During the pandemic, many people constructed their own, low-cost air filtration alternatives, most commonly Corsi-Rosenthal boxes. These contraptions involve four air filters and a box fan, but there’s an even simpler alternative to them — a poorer-man’s poor-man’s air purifier, said Cull: taping a single MERV-13 (or higher) filter to the back of a box fan and placing the unit in the middle of the room. (You want the filter mounted on the upstream side of the fan, with the arrows on the filter — which indicate the direction of airflow through it — pointing toward the fan.) He recommends running this setup around the clock until air quality is back to the healthy range.

What indoor activities should I avoid when the air is smoky?

Certain common household activities — frying foods or cooking foods that smoke, using a gas stove, burning candles and incense, vacuuming (unless you use one with a HEPA filter), and smoking, for example — create byproducts that aren’t great for our airways.

Under normal circumstances, when we’re maximizing ventilation by opening windows or allowing our HVAC systems to draw in outside air, these byproducts dissipate pretty easily. That happens less readily if you’re following any of the above suggestions.

For that reason, it’s especially important to avoid doing these activities inside while you’re taking measures to maximize your indoor air quality. And it’s always a good idea to avoid smoking.

You can get more tips on indoor air from the EPA’s website.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.