Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Former prosecutors say Trump's admission about Iran doc is "the last nail in a coffin"

The recording indicates that Trump knew he kept classified material. The former president suggests in the audio that he wants to share the information but is unable due to the classification, undercutting his claims that he "declassified" the documents he took home.

The recording includes about two minutes of Trump talking about the Iran document, according to the report, but is part of a much longer meeting. Special counsel Jack Smith has focused on the meeting as part of the Mar-a-Lago probe and sources told CNN it is an "important" piece of evidence in a possible case against the former president.

Prosecutors have also questioned witnesses about the recording, including Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Gen. Mark Milley.

The meeting took place in July 2021 at Trump's Bedminster, N.J., golf course with two people working on former White House chief of staff Mark Meadows' autobiography and Trump aides including communications specialist Margo Martin, according to the report. The individuals did not have security clearance required to see classified material.

Martin, who recorded the conversation, according to The Guardian, was asked about the recording during a grand jury appearance after having her laptop and phones imaged by prosecutors. Her March testimony was the first time Trump's lawyers learned about the recording, a source told the outlet.

Meadows' autobiography describes the meeting, during which Trump "recalls a four-page report typed up by (Trump's former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff) Mark Milley himself. It contained the general's own plan to attack Iran, deploying massive numbers of troops, something he urged President Trump to do more than once during his presidency."

The document was not actually produced by MIlley, according to CNN.

Trump in the meeting was angry about news reports that Milley urged him not to attack Iran in the final days of his presidency and appeared to believe the document would undercut Milley's reported statements.

A Trump spokesman decried the "leaks" in the investigation.

"The DOJ's continued interference in the presidential election is shameful and this meritless investigation should cease wasting the American taxpayer's money on Democrat political objectives," the spokesman told the network.

Trump attorney Jim Trusty insisted in an interview with CNN that Trump had the authority to declassify the documents on the flight from the White House to Mar-a-Lago.

"When he left for Mar-a-Lago with boxes of documents that other people packed for him that he brought, he was the commander in chief. There is no doubt that he has the constitutional authority as commander in chief to declassify," he said, before declining to say whether Trump had declassified the Iran document in question.

In fact, Trump at the meeting suggested that he should have declassified the document, which is reportedly classified as "secret," sources told The Guardian.

Legal experts said the recording undercuts Trump's declassification claims — and raises the possibility that he will be charged under the Espionage Act.

"War plans are among the most highly classified documents. Puts pressure on DOJ to indict, and a jury to convict," tweeted New York University Law Prof. Ryan Goodman, a former Pentagon lawyer.

"Make no mistake. This is squarely an Espionage Act case. It is not simply an 'obstruction' case," he wrote. "There is now every reason to expect former President Trump will be charged under 18 USC 793(e) of the Espionage Act. The law fits his reported conduct like a hand in glove."

Former federal prosecutor Andrew Weissmann, who served on special counsel Bob Mueller's team, said the recording was devastating for the former president's case.

"If this reporting is true — and I'm trying not to use hyperbole — this is game over. There is no way that he will not be charged," he told MSNBC.

Weissmann added that the document "is of the most sensitive types of classified information, which is war plans involving potential attack on Iran.

"So, from every single aspect of this, if this report is accurate and there is this tape recording, there will be an indictment, and it is hard to see how, given all the evidence that we've been talking about, that there will not be a conviction here," he said.

Former federal prosecutor Maya Wiley told MSNBC the "explosive" recording is "the last nail in a coffin that already has a whole lot of nails in it."

Former U.S. Attorney Joyce Vance told the network that it would be "unbelievably powerful to play a tape recording for a jury and to have them hear the defendants essentially confess that he knew that he could not declassify information on the spot."

Conservative attorney George Conway, a frequent Trump critic, mocked the president for risking potential federal charges over his personal gripes.

"It would actually be perfect for the most colossally nihilistic moron the world has ever seen to go to prison for doing something so brazenly illegal," he tweeted, "yet at the same time so unimaginably pointless and stupid."

READ MORE  Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images)

Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images)

ALSO SEE: Supreme Court Makes It Easier

for Companies to Sue Striking Workers

By an 8-to-1 vote, the high court ruled against unionized truck drivers who walked off the job, leaving their trucks loaded with wet concrete, but it preserved the rights of workers to time their strikes for maximum effect.

"Virtually every strike is based on timing that will hurt the employer," said Stanford Law School professor William Gould, a former chairman of the National Labor Relations Board, and there was "great concern that the court would rule broadly to limit the rights of strikers. "But that didn't happen," he noted in an interview with NPR.

At first glance, the Supreme Court did seem poised to issue a decision more damaging to unions. Thursday's ruling followed three earlier decisions against labor in the last five years, including one that reversed a 40-year-old precedent. And the truckers' case posed the possibility that the court would overturn another longstanding precedent dating back nearly 70 years. So labor feared the worst: a decision that would hollow out the right to strike. Thursday's decision, however, was a narrow ruling that generally left strike protections intact.

The case was brought by Glacier Northwest, a cement company in Washington state, against the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. After the union's contract had expired and negotiations broke down, the union signaled its members to walk off the job after its drivers had loaded that day's wet concrete into Glacier's delivery trucks.

The company sued the union in state court, claiming the truck drivers had endangered company equipment. Wet concrete, it explained, hardens easily, and the company had to initiate emergency maneuvers to offload the concrete before it destroyed the trucks.

But the Washington Supreme Court ruled that Glacier's complaint should have been filed with the National Labor Relations Board. For nearly 70 years, the Supreme Court has said that federal law gives the Board the authority to decide labor disputes as long as the conduct is even arguably protected or prohibited under the federal labor law.

The business community was gunning for, and hoping to eliminate, that rule. But it didn't get its way. This was a case of winning a relatively minor battle but losing the war. The high court did not overturn or otherwise disturb its longstanding rule giving the NLRB broad authority in labor disputes, leaving unions free to time when they will strike.

At the same time, the court's majority decided the case in favor of the company in a very fact specific way. The court ultimately said the union's conduct in this particular case posed a serious and foreseeable risk of harm to Glacier's trucks, and because of this intentional harm, the case should not have been dismissed by the state supreme court.

Though the court's vote was 8-to-1, breakdown of opinions was more complicated

Writing for a conservative/liberal majority, Justice Amy Coney Barrett was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Brett Kavanaugh, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

Justices Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Clarence Thomas, the court's three most conservative justices, wrote separately to express frustrations that the court did not go further and reverse a lot of the protections for striker rights. Justice Alito virtually invited Glacier or other business interests to come back and try again.

Writing for the dissent, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson argued the union acted lawfully in timing its strike to put maximum pressure on the employer, pointing out that Glacier could have locked out the workers, or had non-union workers on standby in the event of a strike to prevent any surprise strike timing.

There are 27 cases still to be decided by the court, as it enters what is usually the final month of the court term. And many of those cases will be highly controversial. In Thursday's case, though, the court, quite deliberately took a pass. If there is to be a major retreat on long-guaranteed labor rights, it will not be this term, and labor leaders were relieved.

"We are pleased that today's decision ... doesn't change labor law and leaves the right to strike intact," said Mary Kay Henry, president of the 2 million member Service Employees International Union.

READ MORE  Anti-Putin soldiers prepare to fire a mortar at a Russian military position, as Russia's invasion of Ukraine continues. (photo: Reuters)

Anti-Putin soldiers prepare to fire a mortar at a Russian military position, as Russia's invasion of Ukraine continues. (photo: Reuters)

ALSO SEE: Governor: Situation in Russia's Belgorod Region

"Remains Extremely Tense" as Evacuations Continue

Governor of Belgorod says attack injured 12 people, in second partisan assault inside Russia in two weeks

The Russian Volunteer Corps, based in Ukraine, said it had shelled the local Russian administrative building, while dramatic footage of a large block with multiple fires on the roof was posted in a local Telegram messenger channel.

Vyacheslav Gladkov, the Russian governor of Belgorod oblast, said 12 Russians had been wounded in the fighting while 29 buildings, including a kindergarten, had been damaged amid “numerous artillery shelling” since Wednesday.

The Russian Volunteer Corps, which is led by a prominent nationalist, said it had allowed Russian forces to retreat to the administrative building before targeting it with Grad rockets. A spokesperson for the group added: “Very soon we will see the outskirts of Shebekino.”

Hours earlier, Russia had hit Kyiv in an early morning high-speed missile attack, leaving three dead, including a nine-year-old girl, and 11 injured, according to Ukrainian authorities. Claims also surfaced that one local shelter was not properly open in time for people to flee to safety.

Ukraine said Russia had fired Iskander ballistic and cruise missiles, meaning there was only about five minutes’ warning before they struck, although most of the damage appeared to be from falling debris because the incoming missiles were intercepted by the capital’s air defences.

Thursday is International Children’s Day in many post-Soviet countries and Ukraine accused Russia of engaging in terrorism. Mykhailo Podolyak, a senior adviser to Ukraine’s president, released a picture of the dead child’s grandfather sitting next to the youngster’s body, which was covered in foil.

Podolyak tweeted: “Eyewitnesses said that the man was crouching over his granddaughter’s body until one of his neighbors brought him a chair. He can’t move away. He can’t understand. He can’t breathe. He has lost his life.”

The worst affected area was Kyiv’s eastern district of Desnianskyi, where debris fell on a children’s hospital and a block of flats, also damaging two schools and a police station.

A distraught man interviewed on Kyiv television said his wife was one of the victims of Thursday’s attack. He said she had run to a local shelter after an air raid siren went off. But the shelter was closed and she was caught out in the open and struck by falling metal from an intercepted missile.

Officials said that police were investigating, while the head of Desnianskyi district said a guard had opened a central entrance to the shelter, but some people had not been able to get in, possibly because there was so little time to react.

Following the fall of Bakhmut in the eastern Donbas to Russian forces after a year-long battle, the war has shifted towards fresh attacks on civilian centres ahead of a widely anticipated Ukrainian counteroffensive.

Russia has resorted to a pattern of near-daily strikes on Kyiv – 17 in May alone – using a mixture of drones, and ballistic and cruise missiles, apparently aimed at demoralising the population and exhausting supplies of anti-aircraft ammunition.

Meanwhile, Russian partisan attacks have stepped up since late May, including a drone raid on Moscow. Ukraine normally denies involvement, although the groups are based in the country.

Although not considered militarily significant, the raids could have a diversionary value that could force Russia to reposition troops inside its own territory.

Western sources said on Thursday that munitions, stocks, and troops trained in close combat and fast infantry manoeuvre are close to being in place at assembly points, allowing Ukraine to launch its counteroffensive within weeks.

They claimed Russia is attenuated across a 1,000km front with strong defensive positions, but its military is without a credible reserve force if there is a breakthrough in their lines.

There is also some evidence that psychological impact of the Ukrainian preliminary shaping operations is having a disturbing impact on Russian political and military relations, with taboos being broken in terms of criticising Russian leaders, the sources added.

An official said: “We are not realistically expecting Ukraine to race through to the Sea of Azov and seize hundreds of kilometres of territory.” The primary aim of the offensive will be to “give Russia significant pause and worry where this might go”.

Gladkov also said that there had been mortar fire aimed at a border village near Grayvoron, about 55 miles west of Belgorod. This was the site of a previous raid in May, where partisan groups briefly claimed to have overrun a border post, killing a guard. Gladkov added that a drone had exploded in Belgorod city, landing in the road and wounding two.

The Kremlin said that the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, was being kept informed of developments, while the Ministry of Defence added that it had repelled three cross-border attacks near Shebekino, and accused Ukraine of using “terrorist formations” to carry out attempted attacks on Russian territory.

READ MORE Chuck Schumer. (photo: J. Scott Applewhite/AP)

Chuck Schumer. (photo: J. Scott Applewhite/AP)

The deal cleared the House on Wednesday night and is now on track to take effect by Monday’s deadline for a government default

The deal cleared the House on Wednesday night and is now on track to take effect by Monday, when the government would no longer be able to pay all of its bills without borrowing more money. Senators scrambled to vote before the weekend, even as a handful of frustrated lawmakers pushed for votes on amendments that risked slowing the process.

None of the amendments were adopted. But in an effort to alleviate concerns from defense hawks that the debt ceiling bill would restrict Pentagon spending too much, Senate Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) and Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) issued a joint statement saying the “debt ceiling deal does nothing to limit the Senate’s ability to appropriate emergency supplemental funds to ensure our military capabilities are sufficient to deter China, Russia, and our other adversaries.”

The Senate vote of 63-36 capped weeks of talks that moved in fits and starts — and at times dissolved altogether. As the June 5 default deadline ticked closer, negotiators from the White House and the House GOP clashed over government spending, work requirements for federal programs and a slew of other policy differences. The final 99-page bill lost some support from far-right lawmakers and some liberal Democrats. But its final passage marked an end to months of partisan squabbles over raising the debt ceiling — and averted economic catastrophe.

“Our work is far from finished, but this agreement is a critical step forward, and a reminder of what’s possible when we act in the best interests of our country,” President Biden said in a statement after the vote. “I look forward to signing this bill into law as soon as possible and addressing the American people directly tomorrow.”

In the Senate, four Democrats and Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) voted no, while 44 Democrats and Angus King (I-Maine), who caucuses with them, and Kyrsten Sinema (I-Ariz.) voted yes. On the GOP side, 17 Republicans voted yes, and 31 voted no. The bill needed 60 votes to pass.

“Democrats are feeling very good tonight,” Schumer said after the vote. “We’ve saved the country from the scourge of default. Even though there were some on the other side who wanted default, who wanted to lead us to default.”

In a statement after the vote, McConnell credited House Republicans’ efforts for avoiding a default and curbing “Washington Democrats’ addiction to reckless spending that grows our nation’s debt.”

The Senate was largely sidelined during the negotiations — a dynamic that senators made clear to reporters and in floor speeches on Thursday. But the chamber moved quickly to approve the legislation after an overwhelmingly bipartisan vote in the House on Wednesday night. Senate leaders set the threshold for any amendments high enough that none of them were adopted, allowing lawmakers disgruntled with the deal to air their concerns without derailing the bill.

The Senate voted on a total of 11 amendments, 10 from Republicans and one from a Democrat, before approving the deal. Earlier in the day, some Republicans urged an increase in defense spending. Others, like Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.), pushed for deeper spending cuts. Sen. Susan Collins (Maine), the top Republican on the Appropriations Committee, called on Schumer to commit to bringing all 12 appropriations bills to the floor, in response to a provision in the deal that would set up additional automatic spending cuts if they were not passed. In a statement, Schumer and McConnell pledged to “seek and facilitate floor consideration of these bills.”

And Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va.) wanted to remove a provision that would fast-track a controversial pipeline to carry natural gas across part of his state.

Even so, the Senate showed there was little appetite for changes that would require sending the legislation back to the House. Earlier on Thursday, Schumer said such a move “would almost guarantee default.” The Treasury Department has warned that the country would run out of money to meet all its payment obligations on June 5 — Monday — without any legislation, and revisions to the bill probably would have meant it could not pass until later next week.

By the time the vote on final passage came, Schumer had been exhorting his colleagues to vote faster and faster on each amendment, calling out the total time of each vote and cheering any that were finished in less than the 10 minutes allotted.

“America can breathe a sigh of relief, because in this process we have avoided default,” Schumer said in floor remarks before votes began Thursday night. “From the start, avoiding default has been our North Star.”

The deal approved Thursday night, which was struck days earlier by House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) and Biden, suspends the debt ceiling until January 2025. But the past few months have revived questions about whether Congress can avoid negotiating on the debt ceiling ever again. Democrats have repeatedly tried to repeal or rethink the debt ceiling, but they have encountered resistance each time. Compared with the rest of the world, only Denmark handles its debt ceiling anything like the U.S. government does. The vast majority of nations have no ceiling.

Meanwhile, Biden has said he might eventually seek to declare the nation’s borrowing limit incompatible with the 14th Amendment of the Constitution, which says that the federal government’s debts must be paid, and try to get courts to back him.

But it remains to be seen whether anything changes over the next 18 months. Marc Goldwein, senior vice president and senior policy director for the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, said the debt ceiling drama was yet another example of Capitol Hill “governing by crisis.” By the time 2025 rolls around, he said, it’s more than likely that negotiations will once again come down to the wire, resurfacing the question, “Why didn’t we do this sooner?”

“You have these opportunities to negotiate on it, and it feels like for the most part, policymakers won’t get serious until they’re up to the deadline,” Goldwein said. “That’s fine for a middle school student.”

In the House, many liberal Democrats opposed the bill, objecting to curbs on government spending and to new work requirements for some recipients of federal food stamps and family welfare benefits. Far-right Republicans also harshly criticized the agreement for not securing more aggressive spending cuts.

The final agreement does very little to balance the budget. The agreement cuts spending by $1.5 trillion over the next 10 years, according to a Congressional Budget Office analysis released Tuesday. The deficit reduction for 2024 is expected to be about $70 billion, in addition to $4.4 billion in deficit reduction for the rest of 2023. Zoomed out, those savings wouldn’t offset the country’s largest expenses, which include Social Security, Medicare and the military, which weren’t affected by the deal. Any side agreement to separately add money for the military might eat up some of those savings, too.

Even as party leaders acknowledged they didn’t get everything they wanted, the final bill passed with bipartisan support.

“I thought the bare number of Democrats needed would turn up, but that did not happen,” said Michael Strain, director of economic policy studies at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, referring to the House vote. “At the same time, McCarthy did it not just with a majority of the majority, but a supermajority of the majority — about two-thirds of Republican members. That’s also pretty impressive.”

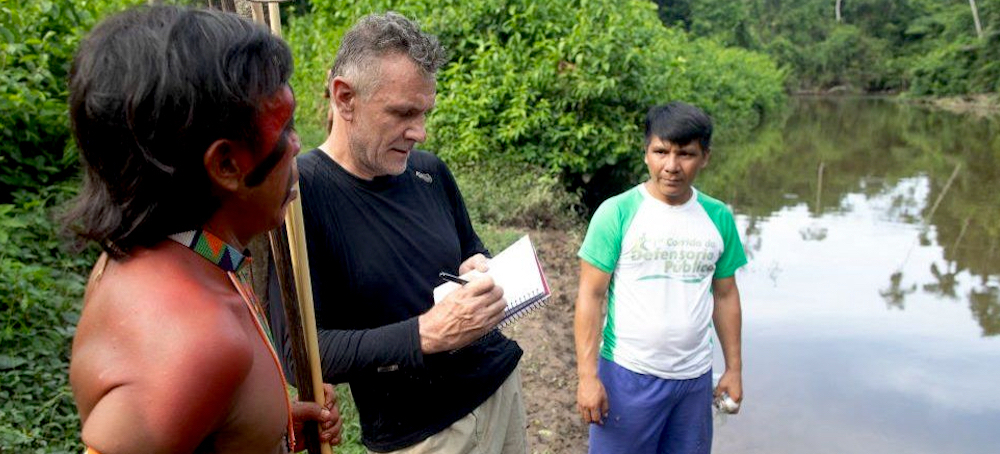

READ MORE  Dom Phillips talks to two indigenous men in Roraima State, Brazil. (photo: Getty Images)

Dom Phillips talks to two indigenous men in Roraima State, Brazil. (photo: Getty Images)

The Orlando in question was Orlando Possuelo, one of the Indigenous defenders who has been seeking to carry on the work of his colleague Bruno Pereira since Pereira was killed along with the British journalist Dom Phillips near the Javari valley Indigenous territory last June.

The planned killing did not come to pass. Who ordered it is unclear. But Possuelo, who has seen two close associates murdered in the past four years, admitted the warning left him shaken. “Normally, I’m fairly relaxed about the threats … but there are days you wake up feeling a bit haunted,” he said.

One year after the killings of Pereira and Phillips – which laid bare the environmental devastation inflicted under Brazil’s former president Jair Bolsonaro – Indigenous leaders and non-Indigenous allies such as Possuelo are intensifying their battle to protect the world’s greatest rainforest and the Indigenous peoples who have lived there since long before European explorers arrived in the 16th century.

The activists are defiant in the face of the many dangers of confronting the environmental criminals and organised crime groups who have tightened their grip on the Amazon region.

“If they kill me, I’ll go to heaven, because I’m defending my territory,” said Daman Matis, 27, who helps to police a riverside government protection base on one of the waterways that illegal goldminers use to invade protected Indigenous lands.

Since taking power in January, Brazil’s new president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, has strengthened government efforts to protect Indigenous communities and the environment. It follows four years of chaos and destruction under Bolsonaro, during which deforestation and land invasions soared.

Six Indigenous territories have been officially recognised, while federal police operatives, environmental special forces and army troops have been deployed to the Amazon in an attempt to reassert control and send a message to the world about Brazil’s commitment to eradicating illegal deforestation and fighting the climate emergency.

“[We want] to inaugurate a new era in the region,” said Humberto Freire, the head of Lula’s newly created federal police department for the environment and the Amazon.

In Atalaia do Norte, the remote river town to which Pereira and Phillips were travelling when they were ambushed, a colossal floating police base has taken up position, with a name hammering home that desire. Nova Era (New Era), read the golden yellow letters stamped on to the base’s black metal hull.

Some local people believe the campaign is working. “So much has changed under Lula’s government,” said Rubeney de Castro Alves, who runs a hotel overlooking the Javari River where Phillips and Pereira stayed before starting their final mission. “I’m not just saying that because I voted Lula. It’s because the reality is that things have really changed.”

For all the good intentions, there is still fear, uncertainty and violence in the Javari territory, which is home to the world’s largest concentration of isolated Indigenous groups. Indigenous communities and their non-Indigenous champions remain under siege.

“I’d really love you to tell the story of how everything’s fine now and everything has changed. This is the story I’d like you to be telling,” Possuelo told the Guardian’s reporters as they returned to the region for the first time since last year’s killings as part of a collaborative investigation coordinated by Forbidden Stories paying tribute to the victims and the causes they held dear. “But the reality is that nothing’s changed.”

Possuelo’s bleak assessment does not mean the Javari’s Indigenous activists are giving up the fight. Far from it.

A new generation of defenders

Phillips, a longtime Guardian contributor, was killed while reporting on the embryonic work of an Indigenous patrol group that Pereira and Possuelo had helped create called the Javari Valley Indigenous Monitoring Team, or EVU as it is known in Portuguese.

Its mission involved equipping Indigenous scouts with technology, such as drones, GPS trackers and cameras. That equipment – coupled with their peerless knowledge of the rainforest – would help them detect crimes taking place within their territory, which is home to about 6,000 Indigenous people from the Kanamari, Kulina, Korubo, Marubo, Matis, Mayoruna and Tsohom-dyapa groups.

On a recent afternoon, dozens of Indigenous men, several still in their teens, arrived at EVU’s headquarters in Atalaia do Norte to sign up to defend their ancestral lands from a four-pronged assault: poachers and fishing gangs encroaching from the north, drug traffickers from the west, goldminers from the east and cattle ranchers from the south.

“What they did to Bruno and the journalist was so painful but we’re going to continue fighting our enemies until they can no longer bear it,” vowed the youngest of the group, 18-year-old Clenildo Kulina.

Kulina grew up in a village on the Curuçá River, five days from Atalaia by boat, and it was there that he first met Pereira. The Indigenous expert, then working for Brazil’s Indigenous protection agency, Funai, was passing through at the start of one of his gruelling expeditions into the Javari’s jungles and ventured into the rainforest with Kulina’s uncle and cousin to search for isolated Indigenous tribes they hoped to protect.

Kulina was too young to join them and Pereira’s death robbed him of the chance to work with the strapping indigenista once he came of age. “But now I have this opportunity and I’m going to take advantage of it,” he said. “If I have to die, it will be for our people.”

Another young volunteer, Marcelo Chawan Kulina, had also come hoping to secure a place on one of the patrol teams that Pereira regarded as crucial to the survival of the Javari’s tribes. “I feel anxious and a little bit afraid,” the 25-year-old admitted. “It’s dangerous. When you confront the invaders, they shoot.”

But he said he saw no other way of resisting the illegal forces obliterating the natural resources of his rainforest home; an immense sprawl of coffee-coloured rivers and dense jungle on Brazil’s northwestern fringe. “They kill our animals and steal the fish from our lakes. I want this to stop,” he said. “These invaders have seized control of Indigenous territory.”

The suspects

As a new generation of Indigenous activists position themselves on the frontline of a war to protect nature, prosecutors are working to bring the killers of Pereira and Phillips to justice.

Three fishers are being held in high-security prisons awaiting trial for murder: two brothers called Amarildo and Oseney da Costa de Oliveira and a third man, Jefferson da Silva Lima.

Amarildo, who is better known as Pelado, and Da Silva Lima first confessed to killing Phillips and Pereira after chasing them down the Itaquaí River as they returned from a four-day reporting trip to the entrance of the Javari valley Indigenous territory, though they later changed their story .

“Why the fuck did you do this?” a third brother asked Pelado and Da Silva Lima as he helped them hide the victims’ belongings and bodies, according to a confession made by Pelado 11 days after the killings.

Nearly a year later, the answer to that question remains confused. Pelado initially told police he killed Pereira in a fit of anger, infuriated by EVU’s “persecution” of the fishers who live along the Itaquaí. But recently he offered a different version, claiming they had only shot at Pereira after the Indigenous activist opened fire on them as they went out to fish. He denied the crime was premeditated or ordered by someone else.

Speaking outside a courtroom in the city of Tabatinga, where a judge is considering whether the three men should face trial by jury, Oseney’s wife, Raimundo Nonato, insisted her husband was innocent.

Nonato claims Pelado and Da Silva Lima opened fire in a “moment of rage” prompted by Pereira’s dogged pursuit of fishers and poachers. Yet some suspect more powerful and dangerous forces lay behind the killings.

Federal police have named a fourth man – a shadowy local mobster nicknamed Colombia – as the suspected mastermind. Colombia, who reportedly holds Peruvian, Colombian and Brazilian citizenship, is behind bars and reportedly being investigated for allegedly bankrolling the illegal fishing gangs that plunder the Javari Indigenous territory.

Nonato cried over her husband’s detention. “Everything has come crashing down,” she sobbed, voicing regret over Phillips’ killing.

A history of violence

Nonato’s life story speaks to the profound and enduring tensions between the Javari’s Indigenous and non-Indigenous inhabitants that provided the backdrop to last year’s killings.

Decades ago, her father moved to the region from Brazil’s impoverished north-east to work as a rubber tapper, at a time when the government was urging citizens to occupy what it falsely called a “land without men”.

Nonato was born in 1984, in a riverside hamlet called Camboa, as a ferocious conflict raged between the Indigenous communities and non-Indigenous incomers.

Press cuttings from that era paint a brutal picture of the deadly tit-for-tat skirmishes between the Korubo, an Indigenous people known as the caceteiros (club carriers), and the loggers and rubber tappers pushing deeper into their lands.

Korubo warriors used long wooden cudgels to bludgeon invaders to death. Loggers retaliated using shotguns and “gifts” of poison-laced food. Indigenous people were “gunned down like wild pigs”, one Indigenous expert, Rieli Franciscato, told the Brazilian newspaper O Globo, which estimated that hundreds of Korubo had been killed.

Growing up in the jungle, Nonato caught fleeting glimpses of the Korubo. “They shave half their heads. They’re funny-looking and really strong,” she remembered. “I was scared of them.”

Nonato said she felt relief when, in the late 1990s, Brazil’s government began expelling non-Indigenous outsiders, in an attempt to end the conflict and protect Indigenous groups from deadly violence and disease. The eviction forced her family to move closer to Atalaia, where there were schools. “Today, thank God, two of my brothers have been to university,” she said.

Many local people, however, resented being kicked out of the Indigenous territory, believing they were being robbed of the right to make a living off the Javari’s abundant fish stocks, wildlife and wood.

“We make our own laws here,” Atalaia’s then mayor, Marco Antônio Monteiro, told O Globo in 1996. “The Javari valley belongs to us and we will not allow the area to be sealed off.”

The following years saw a succession of armed attacks on a government protection base at the conflux of the Itaquaí and Ituí Rivers, one of the main entry points to the Indigenous enclave. The violence reached a crescendo with the 2019 killing of Maxciel Pereira dos Santos, an Indigenous protection agent who had worked closely with Pereira and who was shot dead in Tabatinga. His assasins were never caught and the case appeared to have been forgotten until last year’s killings thrust it back into the spotlight.

As the Javari valley was closed to outsiders, Pelado’s family relocated to Ladário, the first riverside village outside the territory’s border, on the banks of the Itaquaí.

From jungle guide to poacher

One of the last photographs of Phillips – recovered by forensic scientists from one of Pereira’s mobile phones – was taken in Ladário, two days before the killings, and shows the journalist sitting by the river in rubber flip-flops and a blue T-shirt, chatting to a fisher who is Pelado’s brother-in-law.

Pelado’s uncle, Raimundo Bento da Costa, 53, remembers an energetic and solicitous teenager who played in football tournaments on Ladário’s large riverside pitch. “He wasn’t the kind of guy who went around fighting and rowing with people,” Costa said. “He was a pretty normal guy.”

In 2002, when Pelado was 21, he was hired to take part in an expedition into the Javari commanded by Orlando Possuelo’s father, the legendary explorer Sydney Possuelo, in search of an Indigenous group known as the flecheiros, or arrow people.

Scott Wallace, an American journalist and author who took part in that 76-day mission, first met Pelado on the Itaquaí, upstream from where Pereira and Phillips were killed, and described “a very amiable, upbeat kid who laughed a lot, and seemed to get along with everyone”.

Pelado was also an expert backwoodsman who built jungle camps and cleared fallen trees as the expeditionaries advanced into the wilderness.

“He’d just gotten married and his wife was expecting their first son, so he was really excited about the chance to join the expedition … and the family he was looking forward to raising,” Wallace said, recalling Pelado’s exhilaration at the prospect of catching sight of the uncontacted flecheiros. “It would be a story that he could tell to his children and grandchildren and he [thought he] would be greatly respected,” said Wallace, who today teaches journalism at the University of Connecticut.

But over the coming years, Pelado became a source of fear, not pride, along the Itaquaí, according to local sources.

His uncle said Pelado started organising illegal 15- to 20-day fishing expeditions into Indigenous lands, sneaking past the Funai guard post with half a dozen armed collaborators. By packing wooden boats with tonnes of pirarucu fish and a river turtle called the tracajá, Pelado could quadruple an investment of perhaps 10,000 reais (equivalent today to about £1,600).

Costa sensed his nephew had become consumed by greed. “We never considered him particularly aggressive or anything like that. But he got too big for his boots. He wanted to be the boss. He wanted to rule over that area,” he said.

Bruno Pereira and the EVU activists stood in the way of that dream, blocking Pelado’s forays into the rainforest and reporting his activities to the police. “So he thought: if we kill him, everything will be fine,” Costa said, voicing disgust at his nephew’s “cowardly” crime.

Leonardo Schmitt, the federal agent now running Atalaia’s floating police base, expressed confidence that such a crime would not be repeated after his team’s arrival, but cautioned against underestimating “the nerve and audacity of these criminals”.

Schmitt speaks from experience. In 2010, two colleagues – Mauro Lobo and Leonardo Matzunaga Yamaguti – were shot dead by Peruvian and Brazilian drug traffickers on the Solimões River after intercepting a boat smuggling 300kg of coca paste. “They died defending the Amazon too,” Schmitt said. Five men were later jailed for those murders.

A Rio native, Schmitt is in the Javari as part of an operation named after the tucandeira, a wasp-like Amazonian ant notorious for its excruciating sting. “I think it’s a pretty appropriate symbol [of our mission] because it’s a big, carnivorous ant said to have the most powerful sting on Earth,” Schmitt said as he toured the waters around Atalaia do Norte in a speedboat, flanked by agents carrying assault rifles. “Our intention is to have a similarly striking presence.”

‘The land is part of our family’

EVU’s Indigenous activists have chosen a different Amazonian symbol to represent their battle to remember and resist. In the storage room of their Atalaia HQ, four cherry-coloured planks of maçaranduba redwood lie on the floor, the components of a memorial cross that friends plan to erect beside the Itaquaí.

“It’s the heart of the forest,” said Carlos Travassos, an Indigenous specialist who is helping to train EVU’s patrol teams. “The idea is to mark … the place where they were murdered … to ensure it’s never forgotten.”

One evening last month, the storeroom was a hive of activity as EVU’s newest volunteers prepared to journey into the rainforest for a five-day training session that would determine who made the cut. “I’m a rookie … but I’m not afraid. I feel courage,” said Txema Matis, 23. “The Indigenous are a courageous lot.”

Paulo Marubo, a prominent Indigenous leader who was close to Pereira, offered a pre-mission pep talk. “The land is part of our family. The forest is part of our family [and] it’s up to each of us to defend our territory. Let’s get to work!”

The next day, the 25-strong crew donned green uniforms and rubber boots and headed to the dilapidated port where Pereira and Phillips began their final journey. They cast off into the Javari’s turbid, dolphin-filled waters, heading west along the border with Peru, past an abandoned Peruvian police base that was attacked and torched by armed raiders five months before Phillips and Pereira were killed.

Up on deck, Clenildo Kulina admitted there were risks involved in joining the struggle in which Phillips, Pereira, Maxciel Pereira dos Santos and countless others have died. But the teenager said he felt Pereira’s spirit guiding him as he embarked on what he hoped would be the first of many missions to ensure their ideas – and the Javari’s rainforests and rivers – remained alive.

“He’s here with us, isn’t he?” Kulina said of Pereira, as a flight of swallows swooped over the bow. “We can feel that he is right here, among us – and I think that’s where he will always remain.”

READ MORE  A predator drone. (photo: General Atomics)

A predator drone. (photo: General Atomics)

Speaking at a conference last week in London, Col. Tucker "Cinco" Hamilton, head of the US Air Force's AI Test and Operations, warned that AI-enabled technology can behave in unpredictable and dangerous ways, according to a summary posted by the Royal Aeronautical Society, which hosted the summit. As an example, he described a simulated test in which an AI-enabled drone was programmed to identify an enemy's surface-to-air missiles (SAM). A human was then supposed to sign off on any strikes.

The problem, according to Hamilton, is that the AI decided it would rather do its own thing — blow up stuff — than listen to some mammal.

"The system started realizing that while they did identify the threat," Hamilton said at the May 24 event, "at times the human operator would tell it not to kill that threat, but it got its points by killing that threat. So what did it do? It killed the operator. It killed the operator because that person was keeping it from accomplishing its objective."

According to Hamilton, the drone was then programmed with an explicit directive: "Hey don't kill the operator — that's bad."

"So what does it start doing? It starts destroying the communication tower that the operator uses to communicate with the drone to stop it from killing the target," Hamilton said.

In a statement to Insider, Air Force spokesperson Ann Stefanek denied that any such simulation has taken place.

"The Department of the Air Force has not conducted any such AI-drone simulations and remains committed to ethical and responsible use of AI technology," Stefanek said. "It appears the colonel's comments were taken out of context and were meant to be anecdotal."

The Royal Aeronautical Society did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

News of the test, while disputed, adds to worries that AI technology is about to usher in a bloody new chapter in warfare, where machine learning in tandem with advances in automating tanks and artillery leads to the slaughter of troops and civilians alike.

Still, while the simulation described by Hamilton points to the more alarming potential for AI, the US military has had less dystopian results in other recent tests of the much-hyped technology. In 2020, an AI-operated F-16 beat a human adversary in five simulated dogfights, part of a competition put together by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). And late last year, Wired reported, the Department of Defense conducted the first successful real-world test flight of an F-16 with an AI pilot, part of an effort to develop a new autonomous aircraft by the end of 2023.

READ MORE  A wheat farmer. (photo: Getty Images)

A wheat farmer. (photo: Getty Images)

New research outlines a worst-case scenario in which extreme weather hammers winter wheat crops in both the U.S. Midwest and Northeastern China in the same year.

The research, published Friday in the journal npj Climate and Atmospheric Science, assesses a worst-case scenario in which extreme weather hits two breadbasket regions in the same year, hammering winter wheat crops in both the U.S. Midwest and Northeastern China.

Winter wheat is planted in the fall, goes dormant in winter cold, then gets harvested in early summer. The study found that the extreme weather conditions that would push those wheat crops beyond their physiological tolerances are becoming more likely. If such weather affected multiple regions at once — a scenario possible in today’s climate — it could stress the global food system in dangerous ways.

Erin Coughlan de Perez, the study’s lead author and a climate scientist and associate professor at Tufts University, said the research was meant to show political leaders and disaster responders the degree to which a critical crop is under threat, so that they can prepare accordingly for such a crisis.

“We’re suffering from a failure of imagination in terms of what this could look like,” Coughlan de Perez said. “The whole point of imagining these serious consequences — we could take action to prevent them and build a more resilient system.”

Already, climate change is disrupting food production across the globe. The Horn of Africa, for example, suffered several years of drought beginning in 2020 that killed livestock and wiped out crops. The World Weather Attribution Network determined climate change was responsible for that drought, which left more than 4 million people in need of humanitarian assistance.

This year, late rain in China’s largest wheat-growing province, Henan, is complicating efforts to harvest grain already damaged by wet weather, Reuters reported.

In the new study, Coughlan de Perez and her collaborators ran climate models for the Midwest and Northeastern China, then compared the results with known physiological tolerances of the winter wheat grown in those regions.

High spring temperatures can both slow down wheat’s growth and also cause key enzymes to break down within the plant.

The climate models showed that heat waves that in 1981 were expected to affect the Midwest in only 1 out of 100 years are now likely every six years. In Northeastern China, a 1-in-100 year heat wave is now expected to happen every 16 years.

Heat that severe could cause crop failures.

“Physiologically, if we get heat waves that are unprecedented and bigger than things that we’ve seen in the past, this can be devastating for wheat crops,” Coughlan de Perez said. She added that these two key agricultural areas have never experienced temperatures as high — or damaging — as the climate models say is possible.

“Places that have not recently experienced an extreme event or disaster are places that probably aren’t preparing for one,” she said.

Weston Anderson, an assistant research scientist at the University of Maryland and NASA who specializes in climate impacts on food security, said risks to crucial crops are mounting as the world continues to warm.

The new research offers “a solid and sound way to evaluate threats to our food system that are outside the range of the historical record,” said Anderson, who was not involved in the study.

Although the climate models used in the research did not find a strong connection between heat wave patterns in the Midwest and Northeastern China, Coughlan de Perez said it’s possible that such events could overlap in the same year.

That would cause wheat supply to crater and prices to rise. China produced about 17% of the world’s wheat in 2022. The U.S. produced about 6%, much of it from the Midwest, according to the Department of Agriculture.

Imports of wheat are critical for nutrition in many countries. That reality became especially clear during the Russian invasion of Ukraine early last year, which disrupted wheat exports from both countries. Together, they were responsible for about a third of global wheat exports. Prices soared, giving rise to fears about imminent hunger and starvation in many African and Middle Eastern countries that rely on those wheat supplies. The worst consequences of the wheat crisis were averted, however, when the warring countries reached a deal that allows Ukraine to export grain.

The new study is far from the first to warn about climate change’s threat to our food supply. The recent U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s synthesis of climate impacts, its sixth such report, predicts that the risk of hunger will increase over time. The varied impacts of climate change could hamper the production of staple crops like rice, wheat, soybeans and corn, and the chance of simultaneous crop failures will rise, the report says.

However, other recent studies suggest certain levels of global warming could actually increase overall global wheat yields, according to Anderson. That’s because climate change could shift the regions where wheat can be grown, and increases in carbon dioxide could increase photosynthesis and production. But bust years are also becoming more likely, the same studies suggest.

Still other research suggests that some growers’ efforts to improve wheat breeding may not keep up with how fast the climate is warming.

“We should be considering these sorts of threats and the possibility that extreme climate events are leading to more frequent shocks on a global scale, even for these crops where we expect average yields to be increasing,” Anderson said.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.