Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Trump’s fear of damaging press was so much greater than his fear of criminal accountability that he ended up making an incriminating recording.

In the ongoing classified-documents scandal, though, the tapes seem to exist. CNN and The New York Times report that Justice Department Special Counsel Jack Smith, who is investigating Trump’s removal of secret records to Mar-a-Lago, has obtained a recording in which the former president discussed his possession of a sensitive document. According to the outlets, Trump indicates that he knows it’s classified and is aware he cannot share it.

The content of the tape is important for any prosecution of Trump, which would have to prove he knew that what he was doing was wrong. But the circumstances of the recording are also revealing about how Trump operates, and the way he seems to understand bad press as a graver threat than criminal prosecution.

No dispute exists over whether Trump took boxes of documents with him from the White House. The question is whether they were classified and public records, or declassified and his personal property. Trump has asserted publicly—though his attorneys have conspicuously avoided doing so in legal filings—that he declassified all of the materials before leaving office, without providing any evidence for the claim. Audio proof that Trump understood that at least one document was still secret would demolish that defense.

Given that mishandling of classified materials by former officials is apparently common, Smith appears to also be focusing on whether Trump attempted to hide the documents from the federal government once they were requested and then subpoenaed. Reports indicate that Trump had boxes moved to hide them and lied to his attorneys about the material, and an aide allegedly inquired about how long surveillance video was maintained. (Lordy, maybe there are lots of tapes.)

Aside from the egregious violation of the Stringer Bell rule—or perhaps just the Richard Nixon rule—that recording evidence of one’s own criminality represents, the tape would demonstrate yet again Trump’s reckless disregard for the law. Consider the circumstances for the recording. In July 2021, two writers working with former White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows on his autobiography interviewed Trump at his Bedminster, New Jersey, club. Meadows was not present. (Suffice it to say that this is not how Bob Haldeman or Ulysses S. Grant wrote their memoirs.)

Trump was, as usual, in a score-settling mood. A recent New Yorker report had claimed that in the final days of his administration, Chairman of the Joint Chief of Staff Mark Milley had taken steps to prevent Trump from striking Iran. The story’s sourcing was opaque, but it narrated events from Milley’s own perspective. Trump, who likes to portray himself as a dovish, isolationist opponent of warmongering generals, was furious. At the meeting with the two writers, Trump brandished a report that he claimed was Milley’s plan for an assault on Iran, and said that the general had repeatedly urged him to mount an attack. He can apparently be heard waving the papers on the recording. Neither outlet heard the audio, but it was described to reporters at both by multiple sources.

But Trump was reluctant to show the writers the actual document, according to the reports, because he knew it was still classified and they did not have security clearances. He may not have always been so fastidious. Smith is reportedly also investigating whether Trump showed several visitors a classified map.

The recording that Smith has obtained was reportedly made not by the writers but by Margo Martin, a Trump aide who “ routinely taped the interviews he gave for books being written about him that year,” according to the Times. The former president was apparently worried about being misrepresented or misquoted.

To summarize: Trump’s fear of damaging press—whether in the Milley reports or the Meadows book—was so much greater than his fear of criminal accountability that he ended up making an incriminating recording that could end up as a key piece of his own prosecution.

Throughout his career, Trump has behaved as a person who sees image as more important than law. It’s an outlook that seems to stem not only from his inherent disdain for rule of law and love of publicity, but also from a calculation that when the two conflict, image will triumph. Over and over, he’s managed to wriggle out of potential legal jams with bluster, brazenness, and the occasional large check. That worked as president, too, where he escaped serious consequences from Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation and his first impeachment by rallying political support. It was not enough to prevent his loss in the 2020 presidential election, but it helped avoid conviction in his second impeachment.

Trump is still at it. No matter how damning the evidence that Smith is able to assemble, Trump is seeking to bully the Justice Department out of charging him. If that doesn’t work, he hopes to be reelected to the presidency in November 2024, which would allow him to shutter any investigation or prosecution against him, or to pardon himself. It might yet work.

READ MORE  Ukrainian servicemen demonstrated working on a mobile air defense system responsible for protecting a patch of sky just outside Kyiv. (photo: Nicole Tung/The New York Times)

Ukrainian servicemen demonstrated working on a mobile air defense system responsible for protecting a patch of sky just outside Kyiv. (photo: Nicole Tung/The New York Times)

Russian air attacks on Kyiv have come in relentless waves. Yet very little has penetrated the patched-together but increasingly sophisticated air defense network. Here’s why.

The drill is the same for Ukraine’s air defense crews as they work round the clock to combat the relentless barrage of missiles the Russians launch at Kyiv, mostly foiling the most intense bombardment of the capital since the first weeks of the war.

In the month of May alone, Russia bombarded Kyiv 17 times. It has fired hypersonic missiles from MIG-31 fighter jets and attacked with land-based ballistic missiles powerful enough to level an entire apartment block. Russian bombers and ships have fired dozens of long-range cruise missiles, and more than 200 attack drones have featured in blitzes meant to confuse and overwhelm Ukrainian air defenses.

It presents a constant struggle for Ukrainian defenders. Russian assaults can be unrelenting. They come mostly at night, but sometimes in daytime hours, as they did on Monday.

Even when Ukraine manages to blast missiles from the sky, falling debris can bring death and destruction. Early Thursday, Russia sent a volley of 10 ballistic missiles at Kyiv; Ukrainian officials said they were all shot down but that falling fragments killed three people, including a child, and injured more than a dozen others.

Yet overall, very little has penetrated the complex and increasingly sophisticated air defense network around Ukraine’s capital, saving scores of lives.

“We have no days off,” said Riabyi, the call sign of the 26-year-old “shooter” who is part of a two-person antiaircraft missile crew responsible for protecting just one patch of sky just outside Kyiv.

Ukraine’s air defenses are a stitched-together patchwork of different weapons, many of them newly supplied by the West, protecting millions of civilians in Kyiv and other cities, and guarding critical infrastructure that includes four working nuclear power plants. Tom Karako, the director of the Missile Defense Project at Washington’s Center for Strategic and International Studies, called it “a sort of a dog’s breakfast” of systems.

There are hundreds of people like Riabyi, equipped with American-made surface-to-air Stinger missiles and other portable weapons. Many more are operating more complex launchers that have arrived recently, like the Patriot (American), NASAMS (Norwegian-American) and SAMP/T (French-Italian). Ukraine also uses German-made Gepard antiaircraft guns, and a mix of Soviet-era air defenses.

Andriy Yusov, a spokesman for Ukraine’s military intelligence agency, said the recent air raids aimed at the capital were a “massive and unprecedented” assault intended to exhaust air defense systems, strike a powerful symbolic blow at the heart of the ancient capital and sow terror.

President Volodymyr Zelensky once again thanked “the defenders of the sky” in his address to the nation on Tuesday night. The battle in the skies, he made clear, is as important as the bloody struggle being waged by soldiers on land.

Air defense teams have managed to shoot down roughly 90 percent of the incoming missiles and drones recently and, remarkably, 100 percent of the ballistic missiles aimed at Kyiv, according to the Ukrainian Air Force. Those statistics could not be independently verified.

Air defense assets will also be critical in Ukraine’s looming counteroffensive — keeping newly acquired weapons safe as they stage for battle and then providing cover for Ukrainian troops if they manage to break through Russian lines.

Riabyi and his partner, Oleg, 38, are responsible for protecting a sector of the sky measuring around 10 square kilometers outside Kyiv. When the alarm sounds, he said, they race from a base in the Kyiv area to one of a handful of secret firing positions outside the city, pull the tarp off a truck-mounted Stinger system and prepare.

“If an air target is coming close to our sector, our commander gives us command No. 1: find and annihilate,” he said, demonstrating the procedure recently at a secret location outside Kyiv.

After the team fires, their position is exposed and they have two minutes to move or risk being targeted.

On the side of the team’s truck, Ukrainian tridents mark their successes. The first two tridents represent Russian fighter jets they said they shot down during the first days of the war. They said they had since shot down six Orlan reconnaissance drones, two Russian attack helicopters, and two Iranian-made Shahed drones.

Continuing success in the skies, however, is by no means assured.

Leaked Pentagon documents made public in April expressed deep concern that Russia could achieve air superiority as Ukraine runs out of antiaircraft missiles for Soviet-designed S-300 and Buk systems that still make up the backbone of Ukraine’s air defenses.

Since that analysis was leaked, Ukraine’s Western allies have stepped up delivery of new systems and ammunition. The arrival of two Patriot batteries in late April gave Ukraine its first system designed to shoot down ballistic missiles.

Air defense systems rely on a variety of methods to take down incoming missiles. For a cruise missile, which can travel at around 500 miles per hour, an interceptor can target its heat signature or track a laser projected onto the missile by the Ukrainian defender, among other methods.

Ballistic missiles are capable of traveling much faster. Ukrainians target them with interceptor missiles that are also capable of traveling at high speed, and that have their own guidance and radar to assist in tracking at such speeds. The only proven defense against the powerful Russian Iskander missiles is the American Patriot air defense system, which can be fired within nine seconds of a target being identified.

Still, Ukraine must make difficult decisions about how to deploy limited resources.

Mr. Karako of the Missile Defense Project said the recent attacks on Kyiv have shown “how stressing and challenging a concerted air assault can be,” underscoring the need for Ukraine to keep building its defenses as the Russians try to wear them down.

While Ukrainian and Western officials have noted that Russia is most likely running low on precision missiles, and relying more on less accurate missiles and drones, Moscow has shown that it still has the capacity to stage attacks at a regular tempo.

Since Russia launched its full-scale invasion 15 months ago, it has fired over 5,000 missiles and attack drones at targets across Ukraine, according to a recent study by the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

But like Russia’s ground offensives, the air assaults have failed to produce the strategic military effects Moscow desired, according to the study, and Ukrainian air defenses have “greatly shaped the course of the war, limiting Russian striking power.”

Mr. Yusov, the representative of Ukrainian military intelligence, said that the Russians changed tactics after bombardment of civilian infrastructure and cities over the winter and early spring failed to cripple Ukraine’s ability to function.

Moscow is now targeting more military installations to undermine Ukraine’s counteroffensive, he said, while also setting its sights on Kyiv because it remains “an unconquered target for the aggressor.”

Peter Mitchell, writing for the Modern War Institute at West Point, asserted that the barrages are designed to fill the air with more incoming targets than the defenses can handle, “using a combination of land-, sea-, or air-launched missile platforms.”

For Kyiv residents, the nearly nightly blitzes have been exhausting and terrifying. The first alarm usually sounds after midnight and the assaults last for hours.

“I’m checking the information trying to understand what is flying and from where,” said Natalia Ulianytska, 32, a human rights activist who lives in Kyiv.

“When there’s a massive missile attack, I go to the bathroom together with my cat,” she said.

Ms. Ulianytska said she was not so much scared as anxious and “very angry.”

She knows when the Russian drones and missiles arrive by the thunderous explosions in the sky. Even when air defense teams successfully shoot down a target, there is danger as fiery wreckage rains down on the streets below.

Several people have been killed and injured by falling debris in Kyiv in the past month, and scores of businesses and apartment buildings have been damaged.

Riabyi, the gunner, said he has had to learn on the job. He was still going through training at a base in Ukraine’s west when Russia invaded.

His wife, pregnant with their first child, fled their home north of Kyiv before Russian soldiers could occupy the village; Riabyi was dispatched to Kyiv.

His daughter was born in May, but he did not see her for the first time until December. They spent a few days together and then he had to return to his post to help ensure she could sleep safely.

READ MORE  Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy speaking to the press about the debt ceiling negotiations in Washington, D.C., May 24, 2023. (photo: Saul Loeb/AFP)

Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy speaking to the press about the debt ceiling negotiations in Washington, D.C., May 24, 2023. (photo: Saul Loeb/AFP)

Republican lawmakers are refusing to raise the debt ceiling unless Democrats accept sweeping spending cuts and expanded work requirements on social programs — an agenda borrowed from a dark money–funded think tank that has pushed to loosen child labor laws.

In doing so, GOP lawmakers are following the agenda pushed by an obscure conservative think tank bankrolled by far-right billionaires and activists that was behind a recent slew of state bills rolling back child labor laws across the country. The effort comes several years after the GOP passed massive, deficit-busting tax cuts benefiting the wealthy and corporations — and as the party pushes to make those tax cuts permanent, at an estimated cost of $3.5 trillion.

In effect, Republicans want to force Americans in poverty to pick up the tab for the tax cuts they gave to their wealthy donors, while giving those donors more vulnerable workers to exploit.

Republicans are attempting to ram through the think tank’s agenda by refusing to raise the debt ceiling, an arbitrary limit set by Congress on how much money the federal government can borrow, unless Democrats accept sweeping spending cuts and expanded work requirements on social programs.

The government is constitutionally required to pay its debts and meet its contractual obligations, and almost every Congress for the past century has voted to raise the debt ceiling without incident. But with divided control of Congress and Joe Biden as president, Republicans want to use the imminent threat of the United States defaulting on its debts and an economic recession as an opportunity to punish the poor.

Last month, House Republicans passed debt ceiling legislation proposed by Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) that would massively cut government spending on social safety net programs — including Medicaid, food stamps, and cash assistance, known as Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF).

The proposal would subject most Medicaid recipients between the ages of nineteen and fifty-five without dependent children to a work requirement, forcing them to work for at least eighty hours a month or earn a minimum monthly salary to remain eligible. The new requirements likely would cause millions of low-income Americans to lose Medicaid coverage.

The plan would also expand food stamp and TANF work requirements to adults aged forty-nine to fifty-five, which could kick one million people off the food assistance program and more than half a million families off cash assistance.

Study after study has shown that work requirements have no impact on long-term employment outcomes, but they do kick eligible people out of social programs due to administrative burdens and make them poorer.

“When we talk about work requirements, remember, we want to take people from poverty to jobs,” McCarthy told reporters on Monday, adding: “I don’t think it’s right that we borrow money from China to pay somebody that has no dependents, [is] able-bodied, to sit on a couch. What we find is people become more productive.”

McCarthy’s work requirement proposal and his gripes about dependency come straight from the Foundation for Government Accountability (FGA), a conservative think tank that recently made headlines for helping secretly draft several state bills to roll back child labor laws.

One such bill in Iowa would allow fourteen-year-old kids to “perform non-incidental work in meat freezers” and fifteen-year-olds to perform “light assembly work as long as the assembly is not performed on machines or in an area with machines,” NBC News reported. The bill, which has not yet been signed by the governor, “appears to violate” federal labor laws, according to Labor Department officials.

“Work requirements will help get Americans out of dependency and back to work, preserving resources for the truly needy,” said the FGA’s president and CEO, Tarren Bragdon, when House Republicans introduced their debt ceiling proposal. “There has never been a better time to get able-bodied adults back into the workforce.”

Bragdon, a former Maine state legislator, founded the organization in 2011 during the Tea Party’s austerity push as part of the last major debt ceiling standoff, when Republicans demanded significant spending cuts.

One week before Republicans released their current debt ceiling proposal, the FGA released new polling in favor of work requirements. On April 11, the FGA’s polling arm published data showing that more than 70 percent of likely voters support expanded work requirements for cash welfare benefits and food stamps, as well as new work requirements on Medicaid.

The following week, McCarthy proposed expanding work requirements for food stamps and TANF, and imposing new work requirements on Medicaid in his debt ceiling package.

The FGA then put out a white paper claiming that “House Republicans’ proposal for Medicaid and food stamp work requirements will increase the labor force and boost the national economy,” on the basis that “moving just four million able-bodied adults from welfare to work would increase real GDP by an estimated $149 billion.”

Lobbying records show the FGA’s advocacy arm, the Opportunity Solutions Project, started lobbying Congress on work requirements in 2017. In the first quarter of 2023, the group spent $130,000 on lobbying, including on food stamp reform, work requirements, and TANF, according to federal records reviewed by the Lever.

The FGA and its advocacy arm have been bankrolled by right-wing groups in the dark money network built by conservative Supreme Court architect Leonard Leo, and also receive huge money from the family foundation of cardboard box magnate and conservative megadonor Dick Uihlein.

Between 2019 and 2021, Leo’s network contributed nearly $4 million to the FGA and its advocacy arm, according to tax records reviewed by the Lever.

Uihlein’s foundation has contributed nearly $18 million to the FGA since 2014, according to data from the Center for Media and Democracy.

Other major donors to the FGA have included the billionaire Scaife family, heirs to the Mellon aluminum and banking fortune, and DonorsTrust, a donor-advised fund — or pass-through vehicle — long known as conservatives’ “dark money ATM.” (Leo’s network donated $71 million to DonorsTrust in 2021.)

In 2018, the FGA was behind a GOP push to attach work requirements to food stamps — which was passed by House Republicans but failed in the Senate. “Political observers said the inclusion of proposed changes to food stamps was testimony to the FGA’s growing influence in key Republican circles,” the Washington Post reported.

More recently, the FGA and its affiliates have crusaded to eliminate the temporary augmentation of social safety net programs enacted by congressional COVID relief bills — like expanded child tax credits, unemployment benefits, and food stamps.

The FGA noted in its 2021 annual report that it had “leveraged our relationships with governors to help states opt out of the $300 unemployment bonus and build momentum for this federal program to end in September 2021.”

The organization wrote that it had also “capitalized on our work in West Virginia and connections with Sen. Joe Manchin to show 1) the effectiveness of work requirements and 2) how the expanded child tax credit caused dependency, supply chain issues, and inflation problems.”

Manchin, a coal baron turned corporate Democratic senator for West Virginia, reportedly complained to his colleagues that lazy parents would use their expanded child tax credit payments to buy drugs, and demanded that it include a work requirement, before blocking its reauthorization altogether.

Census research found that the expanded child tax credit lifted nearly three million children out of poverty, though temporarily.

This spring, the FGA’s Opportunity Solutions Project was the only group backing legislation in Maine to add work requirements to Medicaid. The FGA also pushed to restart Medicaid redeterminations, or administrative checks on beneficiaries’ eligibility, which often result in people wrongfully losing coverage because they miss a piece of mail. Redeterminations were temporarily paused during the pandemic, but the federal government recently allowed states to start conducting them again.

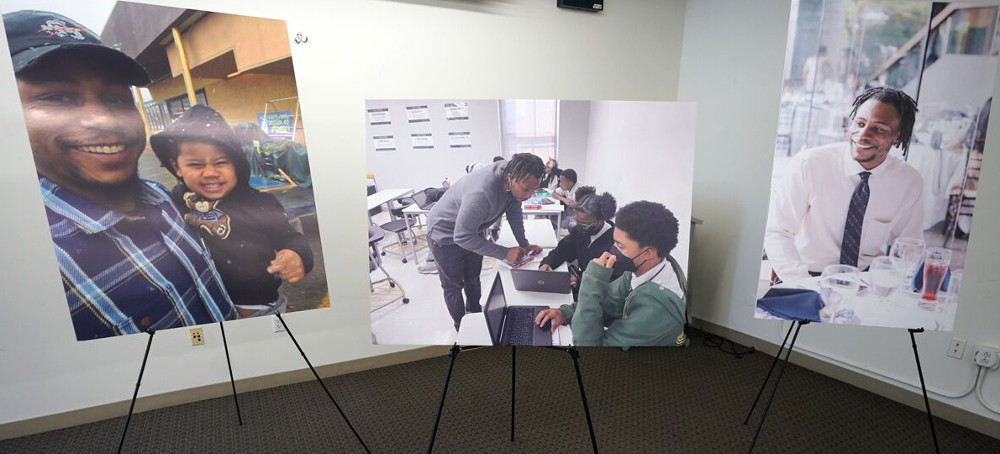

READ MORE  Pictures of Keenan Anderson, who was tasered multiple times during a struggle with Los Angeles police officers and died at a hospital, are displayed at news conference held by his family's attorney, Jan. 20, 2023, in Los Angeles. (photo: Damian Dovarganes/AP)

Pictures of Keenan Anderson, who was tasered multiple times during a struggle with Los Angeles police officers and died at a hospital, are displayed at news conference held by his family's attorney, Jan. 20, 2023, in Los Angeles. (photo: Damian Dovarganes/AP)

The Jan. 3 death of Keenan Darnell Anderson, 31, prompted an outcry over the Los Angeles Police Department’s use of force. It was one of three fatal LAPD confrontations, including two shootings, that took place only days into the new year.

The specific manner of Anderson’s death was undetermined but the cause was listed as “effects of cardiomyopathy and cocaine use” and his death was “determined hours after restraint and conducted energy device use,” the coroner’s report said.

The family’s attorney, Carl Douglas, did not immediately respond to an email from The Associated Press Friday evening seeking comment on the report.

Mayor Karen Bass said her thoughts were with Anderson’s friends and family “as I know the release of this report will cause them and many Angelenos great pain as they still mourn this loss.”

“The coroner raises questions that still must be answered and I await the result of the investigation already underway,” Bass said in a statement.

Anderson was a high school English teacher in Washington, D.C., and a cousin of Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors.

He was visiting family members in Los Angeles when he was stopped on suspicion of causing a hit-and-run traffic accident in the Venice area, police said.

An officer found Anderson “running in the middle of the street and exhibiting erratic behavior,” according to a police account.

Anderson initially complied with officers as they investigated whether he was under the influence of drugs or alcohol, but then he bolted, Police Chief Michel Moore said.

Police chased Anderson and he was shocked with a Taser at least six times during a struggle when he resisted arrest, police said.

“They’re trying to George Floyd me,” Anderson said as an officer threatened to use a stun gun, which was repeatedly deployed seconds later as Anderson was face down on the pavement and begged for help, saying, “I’m not resisting.”

Anderson screamed for help after he was pinned to the street by officers and repeatedly shocked, according to police body camera footage released by the LAPD. Footage also showed an officer pressing his forearm on Anderson’s chest and an elbow in his neck.

“They’re trying to kill me,” Anderson yelled.

After being subdued, Anderson went into cardiac arrest and died at a hospital about four hours later.

His relatives have filed a $50 million claim with the city, which is a legal requirement before filing a lawsuit. The claim alleges officers unreasonably used deadly force, failed to follow training and filed false police reports.

READ MORE  A local resident removes the Russian flag from a billboard in central Kherson, Ukraine, Nov. 13, 2022. (photo: Efrem Lukatsky/AP)

A local resident removes the Russian flag from a billboard in central Kherson, Ukraine, Nov. 13, 2022. (photo: Efrem Lukatsky/AP)

While Putin may have said he was taking what was his, Smithsonian Distinguished Scholar and ambassador-at-large Richard Kurin called it a “war crime.” This act, he claimed during a panel on “Protecting Cultural Heritage in Conflict Zones,” is part of a larger campaign to erase Ukrainian culture.

Kurin added that nearly 1,700 other instances of likely damage to museums, archives and libraries have been reported.

“Particularly in Ukraine, culture and identity and history is being targeted,” Kurin said during the event, which was part of the 2023 Meridian Culturefix Conversations. “This is not collateral damage.”

Moderator Deborah Lehr, the CEO and managing partner of Edelman Global Advisory, added that such forms of cultural genocide are often employed in conflict.

Kurin shared one example from when he was recently in Iraq assisting in the rehabilitation of the Mosul Museum, which had previously been a target of ISIS.

“The obliteration of history and culture, the denial of people’s identity, it has gone on through history. It’s not something new, but the technology of doing it is,” Kurin said. “We’ve spent many years already trying to put back together what ISIS blew up in a few seconds for a few hundred dollars.”

“In Ukraine… a missile, a bomb causes so much destruction [that] it’s going to take years and years and billions of dollars to pick up,” he added.

While their Ukrainian “cultural colleagues” have begun the work of restoration and storing cultural artifacts that could be targeted, First Secretary of the Embassy of Ukraine to the U.S. Kateryna Smagliy spoke on the importance of international collaboration in rebuilding Ukrainian heritage, without which she doesn’t believe they will succeed.

Such rebuilding, she said, starts with understanding the history of Ukrainian culture.

“As of today, we still see a lack of expertise in American universities and all over the world because for many years, the nation of 40 million people was considered insignificant, not important and not deserving a place in galleries, museums and public venues,” Smagliy said.

“Fortunately — if there is anything good that came out of Putin’s actions — Ukraine is finally on the map,” she added.

Though the conflict really began in 2014, Kurin said, this renewed attention has resulted in international support from both the private and public sector, who have provided money, training and ideas on how to preserve Ukrainian culture. It will continue to take a village, he said, to fight that fight.

He then compared the task at hand with the rebuilding of Mostar Bridge, which the former Director-General of UNESCO Irina Bokova said was destroyed during the Bosnian War to symbolize that there could not be understanding between the two sides.

“That bridge connected communities that were then at war and to build that bridge was not only building bricks and mortar, it was building community and the social fabric,” Kurin said. “That’s the thing that’s in front of us.”

“It’s not just the destruction, it’s how do we build back after that?” he continued. “That’s the challenge.”

READ MORE  Narges Mohammadi at her home in Tehran last year during a medical furlough from prison. (photo: Reihane Taravati)

Narges Mohammadi at her home in Tehran last year during a medical furlough from prison. (photo: Reihane Taravati)

Fighting for change has cost Narges Mohammadi her career, separated her from family and deprived her of liberty. But a jail cell has not succeeded in silencing her.

That warning has proved prescient.

Ms. Mohammadi, 51, Iran’s most prominent human rights and women’s rights activist, is now serving a 10-year jail sentence in Tehran’s notorious Evin prison for “spreading anti-state propaganda.”

Her current imprisonment is hardly her first encounter with Iran’s harsh approach to dissent.

Over the past 30 years, Iran’s government has penalized her over and over for her activism and her writing, depriving her of most of what she holds dear — her career as an engineer, her health, time with her parents, husband and children, and her liberty.

The last time Ms. Mohammadi heard the voices of her 16-year-old twins, Ali and Kiana, was over a year ago. The last time she held her son and daughter in her arms was eight years ago. Her husband, Taghi Rahmani, 63, also a writer and prominent activist who was jailed for 14 years in Iran, lives in exile in France with the twins.

The suffering and loss she has endured have not dimmed her determination to keep pushing for change.

A small window in her cell in the women’s ward of Evin opens to a view of the mountains surrounding the prison in north Tehran. Spring brought more rain this year, and the rolling hills were covered with wildflowers.

“I sit in front of the window every day, stare at the greenery and dream of a free Iran,” Ms. Mohammadi said in a rare and unauthorized telephone interview from inside Evin in April. “The more they punish me, the more they take away from me, the more determined I become to fight until we achieve democracy and freedom and nothing less.”

The New York Times also interviewed Ms. Mohammadi over the telephone in April 2022, when she was granted a brief medical furlough from prison. In March and April of this year, The Times interviewed her by submitting questions in writing and in a surreptitious phone call from inside prison arranged through intermediaries.

Last month, the prison authorities revoked Ms. Mohammadi’s telephone and visitation rights because of statements she had issued from prison condemning Iran’s human rights violations, which were posted on her Instagram page, her family said.

PEN America awarded Ms. Mohammadi the Barbey Freedom to Write Award at its annual gala in New York last month. The United Nations named her one of the three recipients of its World Press Freedom Prize this year.

“Narges Mohammadi has been an indomitable voice against Iranian government repression even while being among its most persecuted targets,” said Kenneth Roth, the executive director of Human Rights Watch from 1993 to 2022. “She has been unyielding despite repeated imprisonment, continuing her reporting on government abuse even from her prison cell. Her persistence and remarkable courage are a source of inspiration worldwide.”

Ms. Mohammadi grew up in the central city of Zanjan in a middle-class family. Her father was a cook and a farmer. Her mother’s family was political, and after the Islamic revolution in 1979 toppled the monarchy, an activist uncle and two cousins were arrested.

Two childhood memories, she said, set her on the path to activism: Her mother stuffing a red plastic shopping basket with fruit every week for prison visits with her brother, and her mother sitting on the floor near the television screen to hear the names of prisoners executed each day.

One afternoon, the newscaster announced her nephew’s name. Her mother’s piercing wails and the way her body crumpled in grief on the carpet left a lasting mark on the 9-year-old girl and became a driving force for her lifelong opposition to executions.

When Ms. Mohammadi entered college in the city of Qazvin to study nuclear physics, she looked to join women’s student groups, but none existed. So she founded them, first a women’s hiking group and then one about civic engagement.

In college, she met her husband, a well-known figure in Iran’s intellectual circles, when she attended an underground class he taught on civil society. When he proposed, her parents told her a political marriage was destined for doom. Mr. Rahmani spent their first wedding anniversary in solitary confinement.

The couple lived in Tehran, where Ms. Mohammadi created, expanded and strengthened civil society organizations that were working on women’s rights, minority rights and defending prisoners on death row.

She also wrote columns about women’s rights for newspapers and — to earn a reliable income — worked as an engineer for a building inspection firm. The government forced the firm to fire her in 2008.

The judiciary has convicted Ms. Mohammadi five times, arrested her 13 times and sentenced her to a total of 31 years in prison and 154 lashes. Three additional judicial cases were opened against her this year that could result in additional convictions, her husband said.

Their family of four has not been together as a unit, when one parent wasn’t in jail or exiled, since the twins were toddlers. Ms. Mohammadi and Mr. Rahmani both said their son often says he is proud of his mother’s work, but their daughter has questioned her parents’ decision to have children when their activism remained a priority at any cost.

Holidays and birthdays are when the children grieve her absence more intensely, her husband said.

“This separation has been forced on us. It’s very difficult. As a husband and father, I want Narges living with us. And as her partner in activism, I am obliged to support and encourage her work and elevate her voice,” said Mr. Rahmani in an interview in New York when he came to receive the PEN award on her behalf.

Since September of last year, the couple’s activism has taken on more urgency. An uprising erupted across Iran, led by women and girls, demanding an end to the Islamic Republic. It was set off by the death of a young woman, Mahsa Amini, in the custody of the morality police for allegations of violating Iran’s hijab rules.

Even from detention, Ms. Mohammadi was encouraging civil disobedience, condemning the government’s violent crackdown on protesters, including executions, and demanding world leaders pay attention to Iranians’ struggle for freedom.

Her decades-long efforts have helped raise a grassroots awareness in Iran of these issues. For Iran to transform into a democracy, she says, change must come from within the country through the development of a robust civil society.

“Like many activists inside the prison, I am consumed by finding a way to support the movement,” she said in the written part of the interview. “We the people of Iran are transitioning out of the Islamic Republic’s theocracy. Transition won’t be jumping from one point to the next. It will be a long and hard process but the evidence suggests it will definitely happen.”

Ms. Mohammadi has always treated prison as a platform for activism and a petri dish for scholarly research. During the uprising, she organized three protests and sit-ins and delivered speeches in the prison yard. The women sang, chanted and painted the walls with slogans, promptly erased by the guards.

For as long as she has been jailed, she has led weekly workshops for women inmates, teaching them about civil rights.

Ms. Mohammadi’s research from prison, based on interviewing inmates, resulted in a book about the emotional impact of solitary confinement and prison conditions in Iran. In December she released a report on the systematic sexual assault and physical abuse of women prisoners.

Her friends and colleagues say Ms. Mohammadi’s most remarkable trait is her refusal to be a victim. A trained singer in Persian classical music, she organizes gatherings in the ward where she sings, plays rhythmic tombak on a pot and dances with the other women. In March at Nowruz, the Persian new year, she led a group singing a Persian rendition of the Italian protest song, “Bella Ciao.”

“When prison drags on for many years, you have to give your life meaning within confinement and keep love alive,” Ms. Mohammadi said. “I have to keep my eyes on the horizon and the future even though the prison walls are tall and near and blocking my view.”

READ MORE  Burning forest in Lábrea, Amazonas state in August 2020. (photo: Christian Braga/Greenpeace)

Burning forest in Lábrea, Amazonas state in August 2020. (photo: Christian Braga/Greenpeace)

Investigation involving Guardian shows systematic and vast forest loss linked to cattle farming in Brazil

A data-driven investigation by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism (TBIJ), the Guardian, Repórter Brasil and Forbidden Stories shows systematic and vast forest loss linked to cattle farming.

The beef industry in Brazil has consistently pledged to avoid farms linked to deforestation. However, the data suggests that 1.7m hectares (4.2m acres) of the Amazon was destroyed near meat plants exporting beef around the world.

The investigation is part of Forbidden Stories’ Bruno and Dom project. It continues the work of Bruno Pereira, an Indigenous peoples expert, and Dom Phillips, a journalist who was a longtime contributor to the Guardian . The two men were killed in the Amazon last year.

Deforestation across Brazil soared between 2019 and 2022 under the then president, Jair Bolsonaro, with cattle ranching being the number one cause. The new administration of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has promised to curb the destruction.

Researchers at the AidEnvironment consultancy used satellite imagery, livestock movement records and other data to calculate estimated forest loss over six years, between 2017 and 2022 on thousands of ranches near more than 20 slaughterhouses. All the meat plants were owned by Brazil’s big three beef operators and exporters – JBS, Marfrig and Minerv a.

To find the farms that were most likely to have supplied each slaughterhouse, the researchers looked at “buying zones”; areas based on transport connections and other factors, including verification using interviews with plant representatives. All the meat plants exported widely, including to the EU, the UK and China, the world’s biggest buyer of Brazilian beef.

The research focused on slaughterhouses in the states of Mato Grosso, Pará and Rondônia, important frontiers of deforestation associated with ranching. It is likely the overall figure for deforestation on farms supplying JBS, Marfrig and Minerva is higher, because they run other plants elsewhere in the Amazon.

All three companies say they operate strict compliance procedures, in an open and honest manner, to ensure they are meeting their sustainable goals.

Nestlé and the German meat company Tönnies, which had supplied Lidl and Aldi, were among those to have apparently bought meat from the plants featured in the study. Dozens of wholesale buyers in various EU countries, some of which supply the catering businesses that serve schools and hospitals, also appeared in the list of buyers.

Nestlé said two of the meatpackers were not currently part of its supply chain, and added: “We may scrutinise business relationships with our suppliers who are unwilling or unable to address gaps in compliance with our standards.”

Tönnies said: “These Brazilian companies process many thousands of animals per year for export,” and claimed it was unclear whether the company was the recipient of products from plants linked to deforestation. Lidl and Aldi said they stopped selling Brazilian beef in 2021 and 2022 respectively.

Some of the meat shipped to the EU could breach new laws designed to combat deforestation in supply chains. Regulations adopted in April mean products brought into the EU cannot be linked to any deforestation that happened after December 2020.

Alex Wijeratna, a senior director at the Mighty Earth advocacy organisation, said: “The Amazon is very close to a tipping point. So these types of figures are very alarming because the Amazon can’t afford to be losing this number of trees … this has planetary implications.”

The MEP Delara Burkhardt said the findings reinforced the need for greater legislation globally to tackle deforestation: “The destruction of the Amazon is not only a Brazilian affair. It is also an affair of other parts of the world, like the EU, the UK, or China that import Amazon deforestation. That is why the consumer countries should enact supply chain laws to make sure that the meat they import is produced without inducing deforestation. I hope that the new EU law against imported deforestation will be a blueprint for other major importers like China to follow.”

Aidenvironment found that 13 meat plants owned by JBS were linked to ranches where there had been forest clearance, felling or burning. For Marfrig and Minerva there were six and three plants respectively.

According to a separate Guardian analysis for the Bruno and Dom project, the Amazon slaughterhouses belonging to these companies processed cattle worth more than $5bn (£4bn) while still in Brazil in 2022: more value will be added further along the complex supply chain, and by an overwhelming margin the economic value of this industry is being realised outside Brazil, on dinner plates at restaurants in Beijing and New York. They have repeatedly been criticised for deforestation in their supply chains over the last decade.

Other companies are also known to source cattle from the same buying zones.

In cases where the full beef supply chain could be mapped, the study estimated that since 2017 there had been more than 100 instances of forest loss on farms that directly supplied company plants.

More than 2,000 hectares of forest were apparently destroyed on a single ranch between 2018 and 2021 – São Pedro do Guaporé farm, in Pontes e Lacerda, Mato Grosso state – which sold nearly 500 cattle to JBS, though the copany said the farm was ‘blocked’ when its due diligences identified irregularities with them. The JBS meat plant that processed these cattle sold beef to the UK and elsewhere in recent years.

The farm was also connected to the indirect supply of more than 18,000 animals across the three meat packers between 2018 and 2019 according to Aidenvironment. All three companies said they were not currently being supplied by the ranch.

More than 250 cases of deforestation were attributable to indirect suppliers – farms that rear or fatten cattle but send them to other ranches before slaughter. (Some farms act as both direct and indirect suppliers.)

Meat companies have long said that monitoring the movements between ranches in their complex supply chains is too difficult. Critics say this allows for “cattle laundering”, where animals from a “dirty” deforesting ranch are trucked to a supposedly “clean” farm before slaughter, disguising their origin. A clean farm is one with no history of fines or sanctions for deforestation, even if its owner has carried out deforestation on other ranches.

TBIJ and Repórter Brasil worked with Dom Phillips and the Guardian to report on an example of cattle laundering in 2020. Then, the team appeared to show that cows from a farm under sanctions for illegal deforestation had been moved in JBS trucks to a second, “clean” farm. After the story was published, JBS stopped buying from the owner of both farms.

However, our investigation has found that the owner now supplies Marfrig, another of Brazil’s big three meat packers. One of his farms, Estrela do Aripuanã, in Mato Grosso state, is still under sanctions but remains part of the international beef supply chain.

Records appear to show that between 2021 and 2022, nearly 500 animals were moved along the exact route that TBIJ investigated in 2020. The cattle ended up at the same “clean” second farm, Estrela do Sangue, which has no embargos or other environmental sanctions.

Separate documents appear to show dozens of animals moving from Estrela do Sangue farm to Marfrig’s meat plant in Tangará da Serra.

Last year, another TBIJ investigation linked the Tangará da Serra plant to the invasion of the Menku Indigenous territory in Brasnorte.

According to shipping records, the plant has sold more than £1bn worth of beef products since 2014 to China, Germany, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands and the UK.

In a statement, Marfrig confirmed it had received cattle from the owner, saying: “With every transaction it makes, Marfrig checks the status of the cattle-supplying properties. At the time of slaughter, the farm in question was compliant with Marfrig’s socio-environmental criteria, meaning the property was not located in an area with deforestation, embargo, or forced labour, nor in a conservation unit or on Indigenous lands.”

It added: “Marfrig condemns the practice referred to as ‘cattle laundering’ and any other irregularities. All suppliers approved by the company are regularly checked and must comply with the mandatory socio-environmental criteria described in the company’s current policy.”

Minerva said it “tracks the condition of the ranches, ensuring that cattle purchased by Minerva Foods do not originate from properties with illegally deforested areas; possess environmental embargos or are overlapping with Indigenous lands and/or traditional communities and conservation units.”

JBS queried the “buying zones” methodology used in the research, saying it states “the estimate determines the potential maximum purchase zone and not necessarily the effective purchase zone.” It also said that it blocked the São Pedro do Guaporé farm “as soon as any irregularity was identified”. When asked, it did not specify the date.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.