Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The article below is satire. Andy Borowitz is an American comedian and New York Times-bestselling author who satirizes the news for his column, "The Borowitz Report."

After publication of the texts, which indicate that Carlson knew Donald J. Trump’s claims of widespread election fraud were false, the anchor, concerned that his reputation for mendacity had been permanently tainted, spiralled into despondency.

“Tucker is in a very dark place right now,” a Fox News colleague said. “To be unmasked as an honest person is literally his worst nightmare.”

In an emotional appearance on Fox, Carlson begged his viewers not to “rush to judgment” based on a few “ill-advised texts that give off the unfortunate appearance of accuracy.”

“A couple of years ago, in a moment of weakness, I slipped and told the truth,” Carlson, choking back tears, said. “I plead with you not to judge me by this shameful episode but by my entire body of work.”

READ MORE  A U.S. F-22 fighter jet shot down the alleged spy balloon with a missile. (photo: Insider)

A U.S. F-22 fighter jet shot down the alleged spy balloon with a missile. (photo: Insider)

Illinois hobby group says balloon went missing the day military missile costing $439,000 destroyed unidentified entity nearby

The Northern Illinois Bottlecap Balloon Brigade says one of its hobby craft went “missing in action” over Alaska on 11 February, the same day a US F-22 jet downed an unidentified airborne entity not far away above Canada’s Yukon territory.

In a blogpost, the group did not link the two events. But the trajectory of the pico balloon before its last recorded electronic check-in at 12.48am that day suggests a connection – as well as a fiery demise at the hands of a sidewinder missile on the 124th day of its journey, three days before it was set to complete its seventh circumnavigation.

If that is what happened, it would mean the US military expended a missile costing $439,000 (£365,000) to fell an innocuous hobby balloon worth about $12 (£10).

“For now we are calling pico balloon K9YO missing in action,” the group’s website says, noting that its last recorded altitude was 37,928ft (11,560m) while close to Hagemeister island, a 116 sq mile (300 sq km) landmass on the north shore of Bristol Bay.

The object above Yukon was the second of three felled on Joe Biden’s orders on successive days last weekend after a Chinese spy balloon – a fourth separate object – was shot down over the Atlantic after it crossed the South Carolina coast on 4 February.

US officials said during the week that the three objects shot down after the destruction of the Chinese spy balloon were probably benign and likely to have been commercial or linked to climate research.

On Thursday, after several days of pressure from Democratic and Republican lawmakers, and amid an escalating diplomatic row with China, Biden broke his silence. The president said: “Nothing right now suggests they were related to China’s spy balloon program or that they were surveillance vehicles from any other country.”

He said they were eliminated because authorities considered they posed a threat to aviation, although some observers say the downings were an overreaction amid political pressure over the discovery of the Chinese balloon.

The Illinois brigade’s membership is a “small group of pico balloon enthusiasts” which has been operating since June 2021, according to its website.

It says pico balloons have a 32in diameter and 100in circumference, and they have a cruising altitude between 32,000 and 50,000ft, a similar range to commercial aircraft.

They contain trackers, solar panels and antenna packages lighter than a small bird, and the balloons are filled using less than a cubic foot of gas. According to Aviation Week, they are small hobby balloons starting at about $12 that allow enthusiasts to combine their interests in high-altitude ballooning and ham radio in an affordable way.

Scientific Balloon Solutions founder Ron Meadows, whose Silicon Valley company makes purpose-built pico balloons for hobbyists, educators and scientists, told the publication that he attempted to alert authorities but was knocked back.

“I tried contacting our military and the FBI, and just got the runaround, to try to enlighten them on what a lot of these things probably are,” he said. “They’re going to look not too intelligent to be shooting them down.”

National security council spokesperson John Kirby told reporters that efforts were being made to locate and identify the remains of the objects that were shot down, but the process was hampered by their remote locations and freezing weather.

Kirby also said there was “no evidence” that extraterrestrial activity was at play in any of the downed objects, but the president had ordered the formation of an interagency team “to study the broader policy implications for detection, analysis and disposition of unidentified aerial objects that pose either safety or security risks”.

READ MORE  Arizona Rep. Ruben Gallego speaks during a news conference with newly elected Hispanic House members at the DCCC headquarters in Washington, D.C. (photo: Francis Chung/POLITICO/AP)

Arizona Rep. Ruben Gallego speaks during a news conference with newly elected Hispanic House members at the DCCC headquarters in Washington, D.C. (photo: Francis Chung/POLITICO/AP)

The Arizona congressman, who just launched a campaign to take Kyrsten Sinema’s Senate seat, discusses political pragmatism, the lessons of the war on terror, and what’s really happening in Latino communities.

If this election marks a turning point in Sinema’s political career, then it is also critical for Gallego, an outspoken, partisan figure who represents a different generational tendency, in which the dynamic force in the Party is the young members of the establishment, hardened by the Trump experience, growing more combative in their politics and expansive in their demands. Raised in Chicago with three sisters by an immigrant single mother (his estranged father was at one point imprisoned for drug trafficking), Gallego made it to Harvard, where his work-study job entailed cleaning his classmates’ bathrooms. After his grades faltered, and what he called an “enforced ‘pause’ ” on his studies, he enlisted in the Marine Corps and later served as an infantryman in Iraq, where he saw extensive combat as part of a company that went on to suffer some of the highest casualties of any Marine company during the conflict. Returning Stateside, he eventually moved to Arizona with his Harvard girlfriend, Kate Widland, who is now his ex-wife and the mayor of Phoenix. Gallego’s 2021 memoir of his war experience, “They Called Us Lucky,” is an emotional and at times angry book that emphasizes the tenacity of combat trauma in his own life and in the lives of his fellow-soldiers. Gallego is not idealistic about the business of politics, nor about the people within it. After a short interview by phone, Gallego and I met for dinner in Rockefeller Center, on Monday evening, when the media world was consumed by the news that the U.S. military had shot down several unidentified flying objects over North America. We spoke about the Senate race, the impact that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have had on politics, and—most of all—about the generational change under way in the Democratic Party.

Do you have any insight about whether we’re under attack by aliens? I feel like I would be derelict if I didn’t ask—do you know anything we don’t know?

I definitely know stuff you don’t know, because I’m the former chairman of the Intelligence and Special Operations committee. So, yes, yes, I do. I don’t think what’s happening now is aliens—that I deduced recently.

Are these just balloons?

Could be anything. But if we’re using F-22s to shoot it down it’s probably not aliens. Just a hunch.

You gave a quote to Vox a year and a half ago that really stuck with me, because it seemed to give some insight into how you view politics. You said, “Politics is dark and hard. It’s not a bunch of people trying to do their best. It’s who can shank each other in a smarter way.”

Well, I try to be subtle.

Aha.

Many times, politicians focus on this idea of how politics should be but not necessarily on the outcome. That ends up hurting people that need help. Sometimes you have to maybe not work hand in hand with your loyal opposition. Maybe you should focus on making people’s lives better. A lot of people grew up watching “The West Wing” and thinking that politics can be decided by two people who agree. Well, sometimes you should just care about the outcome. People are hurting right now. They need help, and politicians should focus on how to get that done first.

I had thought this had something to do with the 2020 Democratic primaries, and the very idealistic politics that were ascendent then.

No. I’ve always kind of felt this way. I’ve seen the disappointments of my generation. I was born in 1979. I’ve seen two recessions, the towers fall, us getting thrown into an illegal war—and all this time I think there’s been a certain disappointment with the outcomes. I think it’s because politicians aren’t very realistic.

When you say disappointed with the outcomes—

You have generations right now that find themselves in poverty that their parents were never in. You have the lowest amount of homeownership, especially below the age of thirty. You have the highest amount of debt. All these things that our parents grew up with, that we kind of were expecting, are no longer there. But there really hasn’t been any kind of policy decisions to try to help. Until recently.

If this is your perspective on politicians, do you think that the press is not cynical enough?

I don’t think it’s that the press isn’t cynical enough. It’s just that the viewpoints coming from the press, and from policymakers, are very much a product of groupthink. Everyone went to the same colleges. Everyone grew up in the same areas, and I think they all kind of ended up thinking the same way.

I’ll give you a good example. I won’t name this person, but someone I went to college with was shocked after the 2016 election that Donald Trump had won. We went out to dinner, and he was lamenting that he didn’t understand how it went so bad—G.D.P. growth was happening every year. When you have the same amount of money coming into your checking account but you can’t afford to buy anything new, G.D.P. growth doesn’t matter. And he was shocked. He was, like, “Oh, so we should have been worried about people’s personal income growth the whole time?” Like, yes, yes. I don’t think you have to be more cynical. I just think that people have to look outside their bubble to see what’s actually happening.

I think we should be more cynical.

I also do think reporters should be cynical. That should be your standard.

But you did not grow up in that bubble. You grew up in a different environment.

Yeah, I grew up in a different environment, absolutely.

Tell me about that.

I definitely was an interloper in polite society. I was born and raised in Chicago, but lived for a while in Mexico, the son of immigrants. We lived in Mexico, part time, in a city called Chihuahua, and also in the country, where there was a farm that we were working. When we moved back to the states, we moved into working-class Latino and Black neighborhoods on the South Side of Chicago. You know, in some ways, it’s probably the last generation where I got to ride my bike until the lights were on, all that kind of stuff. But there was also gang violence, things of that nature.

This was the late eighties.

Late eighties, early nineties, yeah. I had a cousin who was shot—everyone knew it was my uncle who did it. It was still a pretty decent experience growing up, but it was working class—my father was a construction worker, and I’d go to construction sites with them and work construction. Things eventually, unfortunately, went bad. My father’s company went under. He started selling drugs. Eventually, my father left the picture. He’d pop in every once in a while, but he was no longer a father. And he was an asshole. You don’t think about it at that age, but, when you think about it later, you’re better off, right?

Not a good dude.

No, not a good dude. My mom is hardworking. She was a secretary. She had four kids to raise. She moved into a small apartment just outside Chicago, a community called Evergreen Park. It was a very working-class area, largely Irish and Italians—a lot of people who work in the trade unions and stuff like that. We had a two-bedroom apartment for five people. I was the only male, so I slept on the floor. I went to college. You know, it was a weird situation—we were poor, but we were working. We weren’t spiteful. I don’t think we thought of ourselves as poor. Now we understand that it was not great. I worked throughout high school. I was a janitor. I worked in a meatpacking factory. I was a line-order cook and then went to school, studied, helped raise my sisters. And I had a lot of help from my teachers, my family.

You’ve said that, when Trump ran, you were very worried early on because you’d grown up among his voters, in Evergreen Park, and you were pretty sure he’d have traction.

When I was starting high school, the effects of NAFTA were starting to get felt, and Rush Limbaugh was actually coming through. I was one of the few Latinos in that high school. And definitely a mouthy Latino. I was not going to back off of anybody. I got shit for it. I was called a spic, beaner, everything else you can think of. People would try to start fights with me, and with my sisters, too. A lot of what I was hearing was definitely things that their parents were saying, right? And where were the parents getting it? It doesn’t excuse the kids for being little shithead racists. It is what it is. But you can tell that there was frustration at that point—it was a Democratic area—about people losing their jobs.

And you don’t think this was just about elemental racism? You think it was specifically about NAFTA?

Oh, there’s elemental racism in everything. But there’s degrees to it. And I think the stress of this shit that was happening in these households was probably on top of that. When Trump came along, years later, I was worried right away. I think a lot of people were saying, “No, no, no, he couldn’t win.” I’m, like, “There’s a big segment of the population who’ve been waiting for someone to say this to them and make them feel good about these thoughts that they’ve been having.” And unfortunately I was right.

You left Evergreen Park to go to Harvard.

You know, I got into this great school, but to this day I’m not really a Harvardian. Like, I went to school there, but I never really fit in.

I think you were there at the same time as Pete Buttigieg and Elise Stefanik.

Yeah, I knew both of them because—this is a weird situation—they were in this group called the I.O.P., the Institute of Politics. I used to go bartend at their events. They have a speaker series and stuff like that. We’d get paid to go bartend or serve food. But, yeah, I knew of them. They were campus celebrities already.

Did it feel as though you were in a whole different world from them?

I never thought about it. I mean, I was just happy I was getting nine bucks an hour. And whenever there was some old dude who came by and said, “Oh, chap,” or something like that, I was, like, This dude’s going to tip me well at the end of the night. I was in this thing called Dorm Crew, where you clean the student bathrooms. It wasn’t until later on that I realized it was actually kind of fucked up—clean the kid’s bathroom, and then see him the next day. When you’re in it, it’s just a work-study job.

You went to Iraq as a marine, in 2005. You’d been working in politics a bit.

Yeah, right. I had just gotten off the 2004 election.

Did you have a political career in mind at that point?

No, I always wanted to work for the C.I.A. or the State Department. I thought it was really cool. I used to love that shit. And I even did an internship at the State Department, just after 9/11, so, probably the summer of 2002. Colin Powell was in charge. I was in the Western Hemisphere department. I loved everything about it. Even took the Foreign Service exam that summer and went pretty far in it. I passed the orals and then didn’t pass the next level. But, yeah, that was a goal. I wanted to be a diplomat. The military—being in the Marines is mostly something that I wanted to do for me. I should have been smarter, in retrospect. But I thought it would be very helpful for going into the F.B.I., the C.I.A., or the State Department.

Before you went to Iraq, in the aftermath of 9/11, did you feel that the U.S. was in an emergency?

Prior to the Iraq War, I actually thought it was a war of emergency. I really thought, at some level—and in retrospect I was wrong—that we were at an existential point in this country. I was already in the military [as a reservist]. I didn’t join because of 9/11, but I hoped that they were going to activate me to go to Afghanistan. Partly I wanted to serve, partly I wanted revenge. People died. In a weird way, for a lot of us younger Latino men, it was our generational fight—kind of a way to be part of the grander American story. And, unfortunately, we ended up in Iraq, and it’s a whole different story. I still feel that Latinos aren’t part of the story of the last twenty years of war, even though a lot of us were in that war.

What do you mean by “aren’t part of the story”?

When you see any movies about the Iraq War, you don’t see, you know, Javier Ramos running around, right? There were a lot of us over there. I mean, we had so many Latinos that we’d speak Spanish to each other on patrol.

You’ve written a whole book about what happened in Iraq and its aftermath, so we don’t need to get into a ton of detail—

I can’t afford more therapy.

But, toward the end of this book, you have a scene where you duck out of an event where Dick Cheney is going to speak because you’re furious about the whole situation.

Yeah. I mean, we were getting fucking killed because these guys didn’t get us enough armor, didn’t get us enough manpower, and just basically left us out there to die.

Knowing what you now know about politics, why did they?

The more I’ve been in this, the more I’ve realized that it was a combination of things: acceptance that people are just going to die; laziness, that they just didn’t want to break through bureaucracy to get us the weapons that we needed; ego, because some of these officers wanted their ribbons and their medals, and we were the fodder; and a lot of wish-casting about what was happening in Iraq.

A lot of us were very heroic at the time, in an awful situation. We were put in an unjust war by our leadership—by our bosses, by our politicians. And, when we returned, people still didn’t want to deal with the fallout of what happened, and kind of wanted to just ignore it for years. One of the things I really wanted to do with my book is not sugarcoat it, because war is dirty, and the aftermath carries on, you know, forever. I’m going to have P.T.S.D. for the rest of my life. A lot of my friends have other diseases, and one too many have killed themselves.

Will there be any effect on policy—fewer wars, for example—if these experiences are properly digested?

You know, I wasn’t born yet, but I think the same thing was said after the Vietnam War, that we wouldn’t find ourselves in foreign engagements. And of course that wasn’t true. I hope people will learn the lessons of the endless war, about military power and what it can do, but I’m afraid that won’t be the case. Until people really feel what happens in war, it’s always going to be easy to ship those kids off to war. It’s the same families and communities that are committing their kids to the military. It’s not really the full society.

Early in the 2016 primaries, I saw Jeb Bush do a veterans’ event in New Hampshire, where he was trying to make a play for the veteran vote, as the brother of the former Commander-in-Chief. There were all these guys at the back of the room, some of them in wheelchairs, many with a kind of broken-seeming look, who were veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and were just not having any part of it. That always stuck with me, and I’ve wondered how much that experience of war had to do with the rise of Trump and populism.

The connection between veterans and Trump is more about his populist appeal. I mean, a lot of them were also very pro-Bernie, right? You sometimes hear from people that Trump is the antiwar guy, but he has nearly gone to war with North Korea a couple of times. He gave the Saudis weapons that are killing innocent children in Yemen.

One thing that was appealing to veterans was that they felt Trump spoke with no bullshit, and they were just sick of the same politicians over and over again. That same group may have cost him the election [in 2020] because they felt that he was a danger to the country and they didn’t vote for him as much as they did in 2016.

Are we still in the Trump emergency, or do you feel like we’re out of it?

You have Trump and you have Trump copycats. Until we actually fully defeat election denialism, I don’t think we can just let it go. There are offshoots of it—dangerous people, such as Michael Flynn, who have this ethno-nationalist religious movement that’s very scary, and that’s not even being paid attention to right now.

Let’s talk a little bit about that. After returning from Iraq, you eventually moved to Arizona, started working in politics, and, by 2011, you were the vice-chair of the Arizona Democratic Party. The next year, you were in the state legislature. The major figures in the Arizona G.O.P. were still John McCain and Jeff Flake, but there were all these other Republicans around who are now part of the national conversation. A big one is Kari Lake, who was then a newscaster, and who eventually became an election denier and was one of the Trumpiest figures in the country in this last cycle, when she narrowly lost a race for governor of Arizona. What did you see of the Republican Party in Arizona then, and how was it transitioning?

I was seeing two things happening at the same time. You had a Republican Party that was trying to be the McCain wing of the Party. And then you had the one being led by people like Russell Pearce and Sheriff Joe Arpaio. That was building, but you felt it all the time. There were people in my American Legion who were in shopping malls where people would come up to them and say, “Go back to your fucking country”—to people who have lived here for generations. As a Latino, I would get it all the time: “Go back to your country. You’re a traitor. You’re a spic.”And that was coming as the Republican Party was getting crazier and crazier. The Republican Party wouldn’t use words like “spic” or anything like that, but they would certainly amp up some of the illegal-immigration rhetoric that was kind of throwing a blanket across all of us.

And that was the time of S.B. 1070. [The law originally required police to determine the immigration status of anyone they stopped whom they suspected of being in the country illegally.]

Yeah. S.B. 1070 really was a wake-up call to Arizona and to Latinos in Arizona, because it’s one time when everyone felt targeted. It’s one time that everyone thought, like, Oh, it doesn’t matter if you are well-to-do—you’re brown, you’re going to be targeted. That’s the one thing that unified a lot of the community to finally get together and start pushing back.

How much responsibility do Republicans such as Flake and McCain bear for this?

It’s not that they’re weak. What the Republicans don’t want to tell you is that people with these views were always there, because they needed them. And, instead of trying to say, “No, that’s not the kind of party we are,” they try to keep them as the base. They ran commercials that are somewhat inflammatory. Maybe they did their best, but there was nobody in the Republican Party who was entirely denouncing the really xenophobic, right-wing tilt that was taking over at that point. They were always trying to figure out how to calm it, how to tame it, but it was always part of the base of the Party that they needed to have.

This is maybe an example of a theme of yours: that politics is about sticking the shank in.

It was a failure of collective action. A lot of Republican leadership wanted this not to happen. But they just wanted someone else to do it for them. Much like Trump in 2016—nobody wanted Trump to happen, but nobody wanted to do anything about it. Even now. In some sense, they’re, like, Well, someone will do it, and I’ll just keep reaping the benefits. In reality, they could have done it, but it would have required all of them to take a leap together. And I think a lot of them were afraid to do it because a lot of them started going down, started losing elections and primaries. And then a lot of them kind of rationalized that they got to live to fight another day.

One of the big themes coming out of the 2020 election was that Democrats were going to have a problem with Latino voters in the future, concentrated especially among Latino men without college degrees. How do you read the evidence of the 2022 election both in Arizona and nationally? How worried do you think the Democratic Party should be about the Latino vote?

In 2022, we stabilized, except in Florida. And, as I tell my friends, Florida is always going to Florida us—and that’s across the board, right? We stabilized because Democrats actually spoke to Latinos early and often. And we spoke to them about things that matter to them. For me, talking about the American Dream matters to Latinos. They want to have steady jobs; they want to have a bright future for the kids. They want to believe that if they work hard, play well, and study hard, they’re going to have that American Dream. In 2022, we were having that conversation more often, about how the Democratic Party is that party. That’s why we were able to recover a lot of that.

The other thing that really matters, and people don’t talk about it, is that January 6th and election denialism drove a lot of conservative male Latino voters back to the Democrats. Latino males, and especially older Latino males, are very patriotic. They love this country. They love the Constitution, and enjoy everything that comes with it.

How did January 6th change the Democratic Party?

I think there’s just a lot more understanding of the danger of letting certain elements of fascism go unchecked. A lot of people thought, you know, maybe it’s just Trump, and other people keep him in check. We were wrong. But it wasn’t just Trump that got us to January 6th. It was all these lawyers with Ivy League degrees and people who have been in government forever, who let this kind of build to the point that we could have had a real disaster on our hands. It has made us more attentive and aggressive. It also gave us the opportunity to reframe what patriotism is. I think patriotism in the past has had a lot to do with honoring the military. A lot of people now understand that patriotism has to do with honoring the Constitution, protecting our institutional democracy.

When I was running for office all those years before January 6th, rarely did people ever talk about the institution of democracy. I think this is a newfound passion. It’s a newfound passion for me. I still can’t believe how close I came to getting killed by an insurrection. It makes me more aggressive. If someone like Kari Lake is my opponent, I’m going to take her down. Not because I don’t think she’s a good person. I think she’s a real threat to democracy. I think she will do anything she can to overthrow elections for her own political game. I think there are a lot of people who would gladly join her, and I think that is a reason why we have to have people running, not just for policy goals but for pure protection of democracy.

There was a big fuss a year or two ago when you said that your office would not be using the term “Latinx” in its official communications. You went on a little Twitter rant about it. And I remember at the time kind of rolling my eyes and thinking, Here goes Gallego grandstanding a bit here, and now he’s going to go on Bill Maher—

Got me on that one!

—and it feels like he’s trying to build a kind of anti-woke brand. Because you could have simply used the words “Hispanic” and “Latino” in your office’s communications and not made such a big deal about it. Why did you make a big deal about it?

I felt that we needed to communicate to the people who were iffy on this that it’s O.K. to not use a term like that. As the chair of the Committee for Hispanic Causes PAC, we see data. We see what’s really happening in the Latino community. There was this very weird feedback loop that was happening where people were afraid to say it, to say, “Hey, ‘Latinx’ is not the most appropriate term to use all the time.” It was important to just start the conversation, because it wasn’t going to be done by, honestly, a white consultant. It wasn’t going to be done by another activist group that was feeling the same way. And so I had a position from which it was safe to say it. I was not going to get voted out for saying it. A lot of us Latinos in Congress have a certain amount of authority to do this that a lot of other people just don’t.

The thing you’re signalling here is to not let the academic, activist language govern how you try to communicate with ordinary people?

Absolutely, yeah. And we did see some campaigns that sent out literature to Latino or Hispanic voters that referred to Latinx voters. That’s a very risky move, considering how few people identify with that word.

Arizona only recently became a state that elects Democrats to statewide office. But the Democrats it elects are, in many cases, people without deep roots there. Mark Kelly and Kyrsten Sinema came to Arizona from other places. You moved to Arizona as an adult.

There wasn’t that barrier. There are more people in Arizona who moved to Arizona after 1990 than who lived in Arizona before 1990. That tells you something about the movement of people in Arizona. And because the Arizona Democratic Party was very bare-bones, there wasn’t a hierarchy we had to fight.

One of the people who didn’t have to fight that hierarchy is Senator Sinema, who you are now running against. I’m sure you watched her campaign in 2018 closely.

I volunteered. I donated, I knocked on doors for her. . . . We had met early on, when I worked on a campaign that she was the chairwoman of.

You were both operatives.

Yeah. And we were in the State House together. She was an effective legislator who I think at that point was in it for the right reasons. She ran for Congress, and a lot of us were happy that she won and were rooting for her. But you could sense that there were some things that were kind of off during the campaign. There was a group that got together to recall Russell Pearce, who was the head of the S.B. 1070 movement [and the president of the State Senate]. They called us and asked us to support the recall, and I said of course I would do it, I would raise money for the recall. I got some calls from some very big donors who were, like, “How can you do this? Russell’s the president. He’s not that bad.” Like, he is bad. Sorry. He literally tried to take away birthright citizenship in Arizona. You don’t get any worse than that. When Kyrsten was asked if she was going to support the recall, she absolutely said no. She said, “I have to work with this guy.” That was in 2012. In 2016, she refused to endorse Hillary—didn’t campaign for her, didn’t show up at anything. That was troubling for me.

What’s your theory about what happened with Sinema?

She didn’t learn. When you grow up poor, every day is a grind. For me, the walk to school was the biggest thing in my life. It was cold. It was rainy. And then I had to figure out how to get back, and how to do the work, and all this kind of shit, right? And now you multiply that by three hundred and sixty-five days, and by however many years. The whole time you’re just, like, How the fuck am I gonna get out of this? That’s all you’re really obsessing about. What are my little lights that I can focus on?

A lot of it is about who’s helping you out. My computer wasn’t up to snuff for my college applications, so the Kobelt family, a really nice family in Evergreen Park, would let me use their computer. You need that kind of stuff. I had a librarian, Linda, who would let me stay after school and practice exams. And so it’s weird to see somebody who I think went through the same thing just be, like, I’m not going to worry about these people anymore. I’m going to worry about these people who are already doing well, and already have power. It’s as if she literally forgot the lessons of being poor.

You’ve said that you considered challenging Mark Kelly when he ran for Senate, in 2020.

If I ran against Kelly it would have been a losing campaign. We did our polling, and, honestly, we were ten points down before we started, which is . . . manageable. But it was going to be a two-year race for a two-year term, and then you’d have to run again. It was going to have to be running to his left and going negative where you can—I was going to spend so much time away from my baby son attacking someone else, who I think at his core is a good man who would end up doing the right things. It didn’t make sense. It was hard because he didn’t have any positions at that point. He was an astronaut. It’s great to have a great American story, but try running against a fucking astronaut. I mean, that’s hard.

Sinema’s got an eighty-two-per-cent rating from the A.F.L.-C.I.O. And I think she’s someone most progressives would trust on social issues—she’s been a leader on reproductive and L.G.B.T. rights. The place where they might have the most doubt is on economic issues. But, even there, the A.F.L.-C.I.O. says she goes four-fifths of the way toward where they’d like her to go. That’s not terrible. Why is it so important to run against this person, when you might risk splitting the vote and throwing it to Republicans?

When push came to shove, was she going to make the right decisions? She didn’t. I was on the floor on January 6th. It was not a great situation. The country was under threat. We need to have some legal way to stop these courtroom insurrections that are going to happen, and she’s there upholding the filibuster of the John Lewis voting-rights act, of a person who she claimed was her friend and mentor. When she was needed, when we needed courage from her, she did not show courage. This is a tough job. You’re spending all this time away from family, all this kind of stuff. Why do all this if, at the end of the day, you’re not really moving the ball forward? Not really making people better? That’s what she represented to me.

At an earlier point, I asked you if we were still in the Trump emergency, and you said, basically, yes.

Right.

That sounds to me like part of what you are saying here.

I don’t really think you need to be a lockdown Democratic voter. I don’t think the problem is that she didn’t stay with the Party. It’s that she didn’t stay true to Arizona. Nobody sent her over there to negotiate for pharmaceutical companies. She did that. No one sent her to negotiate for hedge-fund managers and private equity. She did that on her own. Where was this pressure coming from? And then she didn’t even bother to tell us why she did it. She doesn’t have town halls. Well before me, people were mad about it. Because, at some level, she had broken the social contract she had created with these voters.

When I talk to folks about this race, what I hear, generally, is that “Gallego is trying to get her out of the race, because, if she stays in, and you have two people elected as Democrats and one as a Republican, you’d bet on the Republican.”

People need to make their own estimations about whether it’s worth it. If we run a really, really good race, she and other people are going to have to make calculations. If she stays in, she’s not going to be a senator. And I’m going to. If she leaves, I’m going to be a senator.

The Democrats have been outwardly very cordial about Sinema leaving the Party. They’ve allowed her to keep her committee posts; they’ve said accommodating things about her. Do you think that suggests that they’re going to avoid intervening in this race?

Look, elected officials are just passive-aggressive by nature. They’re not going to confront somebody they don’t have to, and so they put off making hard decisions. Right now, it’s so early in the race that they don’t have to make a decision. [The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee] is not going to do anything in this race for a while. Why put yourself in a weird situation with someone you’re going to need to sit next to for the next two years when you can just put off the decision, right? I wish it were deeper than that. But there is no Machiavellian move. It’s just a passive-aggressive standoff.

READ MORE  Donald Trump. (photo: Erin Schaff/NYT/Redux)

Donald Trump. (photo: Erin Schaff/NYT/Redux)

In 2020, Fox News anchors Tucker Carlson and Sean Hannity pushed Donald Trump’s election fraud claims for weeks. New documents suggest they never believed any of it.

It’s hard to think of a more succinct encapsulation of conservative media than one of its biggest stars complaining that reality is ruining his credibility.

Carlson wasn’t alone. A week later, Sean Hannity texted Carlson and fellow Fox personality Laura Ingraham that calling Arizona for Biden — again, we should stress, simply reporting reality — had “destroyed a brand that took 25 years to build and the damage is incalculable.”

Carlson later tried to get another Fox News reporter fired for a tweet questioning Trump’s false assertions of election fraud. Carlson didn’t claim the reporter’s tweets were inaccurate, according to newly revealed text messages. Rather, his main concern was that “The stock price [of Fox’s parent company] is down. Not a joke.”

It may not surprise many readers that Fox News values right-wing propaganda over facts. But newly released documents from a major defamation case against the network show just how deep a cynical disregard for the truth went with its biggest on-air talent.

In a $1.6 billion lawsuit, the voting machine company Dominion Voting Systems says that Fox News defamed it by claiming Dominion machines were switching votes from Trump to Biden. As part of the suit, Dominion gained access to internal Fox communications, some of which were released in a court filing yesterday.

Quotes like Carlson’s about the stock price and continual fretting about low ratings by Fox pundits and executives bolster Dominion’s argument that Fox personalities continued to make claims they knew were false out of a concern for losing viewers to even more extreme outlets like Newsmax. Carlson and Ingraham privately described Trump surrogates with terms like “liar” and “a complete nut.” But in one of the few accurate statements he’s ever made, Carlson got at the heart of the issue. Trump, he wrote in a text to his producer, “could easily destroy us if we play it wrong.”

In their internal communications, Carlson and Hannity sound less like journalists and more like hucksters who realize the jig is up. Stuck between the potential wrath of Trump and his followers on the one hand, and Fox owner Rupert Murdoch’s insistence on reporting material with some semblance of the truth on the other, they panicked.

Fox claims that it was simply reporting claims made by Trump and other newsworthy individuals without propagating false claims itself. But Dominion seems unusually confident in its chances, given how difficult defamation cases are for plaintiffs in the United States.

So far, Fox has managed to keep parts of its communications redacted in the public versions of court filings. Adding to Fox’s legal headaches, the New York Times is suing to unseal the full record. We might not even have seen the worst of it yet.

READ MORE  A voter at a polling precinct. (photo: NAACP)

A voter at a polling precinct. (photo: NAACP)

The supreme court race in Wisconsin, America’s most crucial swing state, is the biggest election of 2023.

Democrats and Republicans don’t agree on much in Wisconsin, the nation’s most important and arguably its most polarized swing state. But they agree that their state’s ongoing Supreme Court election is the most important in a generation.

“The Supreme Court race is for all the marbles,” Wisconsin Democratic Party Chairman Ben Wikler told VICE News.

Conservatives concur. They’re even using the same description.

“This is for all the marbles,” Brandon Scholz, a veteran Wisconsin Republican strategist and lobbyist who has managed previous supreme court races, told VICE News.

The April 4 election will determine whether liberals or conservatives have a majority on the state Supreme Court.

That balance of power couldn’t be more important. The court will soon decide whether abortion is legal for the state’s 6 million people. It will likely reconsider whether the aggressively gerrymandered maps that have kept Republicans mostly in control of the swing state for more than a decade will remain in place through 2030. And it will play a crucial arbiter of how the state’s elections are run in 2024, when Wisconsin could once again decide who wins the presidency.

Early voting has already begun for the February 21 nonpartisan primary, and the top two vote-winners will advance to an April 4 runoff election.

“This is for all the marbles.”

The race has centered heavily around abortion. When the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the constitutional right to an abortion last year, an 1849 law banning abortion in Wisconsin went back into effect (it was written just one year after Wisconsin became a state, and more than a half-century before women gained the right to vote). Wisconsin Democratic Attorney General Josh Kaul is challenging the law, and whoever wins this race will likely be deciding vote on how that case goes.

Milwaukee County Circuit Judge Judge Janet Protasiewicz, a liberal who is expected to advance to the general election, has campaigned hard on abortion rights and told VICE News that “a woman should have a right to choose.” Her two conservative opponents, former Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Dan Kelly and Waukesha County Circuit Judge Jennifer Dorow, have been slightly less explicit about the issue—but both have endorsements from Wisconsin Right to Life, the state’s largest anti-abortion rights group.

But abortion isn’t the only crucial issue at stake in this race.

Wisconsin was the tipping-point state in both the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections, has been ground zero for fights over gerrymandering and fair elections in recent years. Its makeup will be crucial in future democracy fights.

“The Wisconsin Supreme Court race will shape the future of American democracy,” said Wikler.

Conservatives have had a majority on Wisconsin’s highest court for more than a decade, and during that time have largely sided with Republicans on a bevy of hot-button issues.

Before the 2022 election the court banned absentee ballot drop boxes; in 2014 it upheld a Republican-crafted voter identification law that studies indicate has suppressed the Black vote; and in 2011 it allowed Republicans’ deeply controversial law that gutted public-sector unions.

The justices narrowly ruled 4-3 against considering a Trump lawsuit that aimed to overturn his 2020 election loss in Wisconsin—but in most other cases the court has sided with the GOP. That includes a decision that ended Wisconsin Democratic Gov. Tony Evers’ COVID-19 emergency order early in the pandemic, as well as decisions that stripped him of other powers.

And voting rights will continue to come up. A conservative group is suing to ban mobile and alternate voting facilities in order to limit access to voting; the Democratic National Committee intervened in the lawsuit this Monday in a case that will likely wind up decided by the Wisconsin Supreme Court, and will likely hinge on who wins this race.

But conservative Justice Patience Roggensack’s decision to retire has given liberals their best chance in a generation to win back control.

“Everything is at stake, and I mean everything: Women’s reproductive rights, the maps, drop boxes, safe communities, clean water,” Protasiewicz told VICE News. “Everything is on the line.”

“Everything is at stake, and I mean everything: Women’s reproductive rights, the maps, drop boxes, safe communities, clean water. Everything is on the line.”

Arguably the most important decision the court made in recent years—and one that it will almost certainly revisit if liberals win a majority—is their 4-3 decision in 2022 to use GOP gerrymanders that give Republicans unchallenged control of the legislature even though Wisconsin is the swingiest of swing states.

The maps are so gerrymandered that Republicans hold six of Wisconsin’s eight House seats and nearly two-thirds of legislative seats in the state—even though Democrats won most statewide races last year. Republicans fell just short of a supermajority that would have allowed them to override any vetoes and govern the state as they saw fit, even though Wisconsin voters reelected a Democrat to the governorship.

Protasiewicz has called the maps “rigged,” and suggested to VICE News that she thought they should be struck down.

“We should have fair maps, and we should have a representative democracy that really represents all of the people,” she told VICE News. “You look at the way the maps [are drawn], and you just know something's just not right.”

She also told VICE News that she thought the Court’s decision upholding Act 10, the law that ended collective bargaining rights for most public-sector employees in Wisconsin, was wrongly decided. That act has greatly weakened organized labor in the state, and essentially broke the back of public-sector unions. The year the law passed, 334,000 Wisconsinites were union members; in 2022 that was down to 187,000, according to recent data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Protasiewicz has raised $2 million already for the race, more than double the amount the other three candidates have brought in combined, and is expected by everyone involved to be one of the two candidates who qualify for the final round of voting. Dorow and Kelly are fighting for the second slot. Dane County Circuit Judge Everett Mitchell, another liberal, is also running, but has badly trailed in fundraising and is expected to finish fourth.

The race is ostensibly nonpartisan—the judges don’t run as Democrats or Republicans. But for decades, judicial candidates have clearly run as liberals and conservatives. In recent years it’s become even less subtle, with the same national groups, megadonors, and strategists who fund and run regular political races taking control of these contests. Protasiewicz has been even more explicit about her views, which has drawn criticism from the right, but there’s little doubt where she or the other candidates will land on major hot-button issues.

Protasiewicz’s spokesman is a longtime Democratic strategist who most recently was an Evers adviser. Dorow’s campaign is being run by the same woman who ran the 2022 Republican campaign for attorney general; Kelly’s first campaign manager was Alex Walker, a veteran GOP operative and the son of Republican former Gov. Scott Walker. (He has since left for a job in the statehouse).

Kelly was appointed to the Wisconsin Supreme Court by Walker in August 2016, and served through 2020, when he lost his reelection by a double-digit margin in spite of an endorsement from then-President Donald Trump.

Kelly is a hardline conservative who almost never broke with Republicans on rulings. He wrote the majority opinion that struck down a law in the city of Madison prohibiting guns on public buses, and spent most of his career while not on the bench working for rightwing legal groups. During that period he defended Republicans’ 2011 gerrymander in court, described President Obama’s 2012 reelection a win for “socialism,” and said the U.S. Supreme Court was wrong to declare same-sex marriage a constitutional right. In 2022, he headlined “election integrity” events sponsored by the Republican National Committee that seemingly played on conservatives’ conspiracy theories about the 2020 election.

Dorow has a shorter political track record, but it’s clear where she’s coming from. She was appointed to her current role by Walker, describes herself as a “judicial conservative,” praised the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, and called the Supreme Court decision that struck down homophobic anti-sodomy laws “judicial activism at its worst.”

Her husband, Brian Dorow, twice ran unsuccessfully for state senate as a Republican, worked security for Trump campaign events, and was a political appointee at the Department of Homeland Security during the Trump administration.

Protasiewicz has support from numerous unions including the American Federation of Teachers, AFSCME, and the United Auto Workers. And she was recently endorsed by EMILY’s List, which backs pro-abortion rights Democratic women. This is the first time they’ve ever gotten involved in a judicial election.

“The rights and freedoms of millions of Wisconsinites hinge on a Wisconsin Supreme Court committed to reproductive freedom, democracy, and voting rights for all. Protasiewicz has been a champion for Wisconsinites for over 35 years, and we have full confidence in her dedication to fairly interpreting the law and standing up to extremism,” EMILY’s List President Laphonza Butler said in a statement announcing the endorsement.

They’re not the only deep-pocketed group that’s gotten involved.

Kelly is backed by a super PAC funded by billionaire rightwing mega donor Dick Uilhein, which has spent nearly $2 million in ads that tout Kelly’s deciding vote to end Evers’ stay-at-home order.

“Dan Kelly has a proven record of protecting our freedoms and cast the deciding vote to end the COVID lockdowns of our schools and businesses,” their ad says.

And an affiliate of the Susan B. Anthony List, the nation’s largest anti-abortion rights group, announced a six-figure spending campaign to boost Kelly on Tuesday.

“Lives will be saved or lost depending on the outcome of this election,”SBA Pro-Life America’s Director of State Public Affairs Kelsey Pritchard said in a statement announcing the effort, before warning that the court “is in danger of becoming a tool of the radical abortion lobby” if a liberal wins the race.

Regardless of which conservative comes through the all-candidate primary, the general election is expected to become the most expensive judicial election in Wisconsin history.

The contest for second place has grown tense in recent weeks. Kelly and his allies have accused Dorow of being an unreliable conservative with a thin track record, and he’s refused to say if he’ll endorse her if she finishes ahead of him in this race.

Kelly has a longer judicial track record and is getting more outside support, but Dorow has higher name recognition. She recently presided over the high-profile trial and subsequent life sentencing of a man who killed six and injured dozens of others when he drove into a Christmas parade in Waukesha in late 2021, a trial that drew national headlines and led the nightly local news for weeks.

That’s given her a platform to run as the tough-on-crime candidate—a potent issue, especially on the right. The Waukesha Christmas parade tragedy is just the latest high-profile, racially fraught case of violence in southeastern Wisconsin in recent years. When police shot and paralyzed Jacob Blake, a Black man, in nearby Kenosha during the summer of 2020, unrest and riots followed. Kyle Rittenhouse, a white right-wing teenager, killed two and wounded a third person during that unrest, but was found not guilty on all charges in late 2021.

Conservative outside groups have sought to make crime and safety the top issue of the race, and are on the air attacking Protasiewicz as soft on crime. She’s sought to neutralize the issue: Her latest ad claims Dorow “got rich defending predators for child sex crimes and pornography” while Kelly “defended child molestors posing as youth ministers.”

Conservatives are split over who would make the better general-election candidate, though many think Dorow would have a better shot at victory. Kelly is more explicitly conservative, lost his 2020 race by a double-digit margin, and struggled on the campaign trail in that race. Some, however, are concerned that Dorow’s past as a defense attorney and allegations that her son may be a drug dealer could hurt her campaign. Dorow’s and Kelly’s campaigns did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Democrats seem to be more worried about facing Dorow: A liberal outside group is spending nearly $1 million on ads attacking her for her work as a defense lawyer.

Regardless of which conservative comes through the all-candidate primary, the general election is expected to become the most expensive judicial election in Wisconsin history. More than $5 million has already been spent or reserved by the candidates and outside groups. Strategists in both parties expect that total spending could well double the previous all-time spending record of $10 million that was set during Kelly’s losing 2020 race.

Both sides know what’s at stake.

“Our democracy is on the line,” Protasiewicz told VICE News.

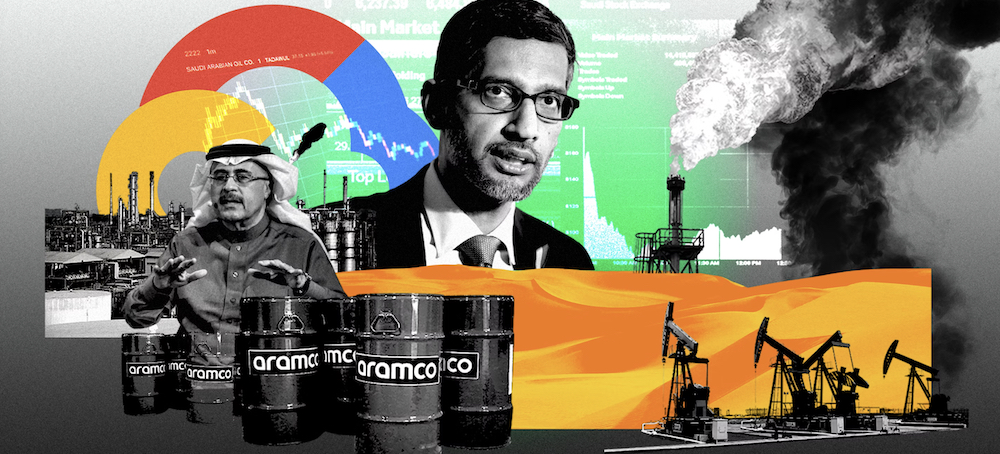

READ MORE  "The danger of what Google is doing lies in the company misleading the public." (image: Lucie Wimetz/The Intercept)

"The danger of what Google is doing lies in the company misleading the public." (image: Lucie Wimetz/The Intercept)

Google wants you to think that its work for Saudi Arabia will help save the planet.

“The science is clear: The world must act now if we’re going to avert the worst consequences of climate change,” Pichai wrote, and that meant phasing out Google’s use of fossil fuels in favor of clean, renewable power.

Two months later, Google announced it was partnering with Saudi Aramco. The internet giant maintains that the joint venture with Aramco — one of human history’s most prolific producers of oil and gas — is entirely green, but critics question whether it’s possible to work for a fossil fuel powerhouse without being complicit in the very dirty business of fossil fuels.

Google went into PR cleanup mode following the announcement, dispatching Thomas Kurian, head of the highly lucrative cloud-computing division, to deny allegations of climate hypocrisy. Yes, Google works with Big Oil, Kurian told Bloomberg TV’s Emily Chang, “but to the environmentally clean or green parts of these companies.” He added, “We have said that again and again that we don’t work with the oil and gas division within Aramco.”

Within months of Kurian’s denial, Aramco was using Google Cloud to transport methane gas more efficiently. When burned as fuel, methane is a leading source of carbon emissions.

This past November, Google Cloud hosted an “emissions hackathon” at the offices of Schlumberger, a Houston oil field services company. The winning team was none other than six Aramco oil and gas data scientists who’d devised a method of using Google Cloud’s machine learning features to detect and repair leaks in methane gas pipelines.

Google spokesperson Ted Ladd stood by the Aramco partnership in a statement to The Intercept, defending the collaboration as a means of helping Aramco “protect the environment.” The claim cuts to the heart of an ongoing debate among climate advocates and policymakers, in the halls of power and boardrooms alike: Can fossil fuel use be made meaningfully cleaner through technology, or does so-called decarbonization only “greenwash” the irredeemable pursuit of fossil fuels that must be cast aside to preserve life on Earth?

Whatever the Google-Aramco project offers in terms of environmental protection, this much is clear: The joint venture will be lucrative, bringing Google’s sophisticated cloud computing services to Saudi Arabia, an estimated $10 billion market, through the construction of a vast data center in Dammam — the very place where Saudi oil was first discovered in 1938 and where it continues to be pumped out by Aramco today.

The Decarbonization Myth

The notion that a company of Google’s immense influence can work with a world historical exporter of hydrocarbon fuels while championing a “carbon-free future” is controversial.

Some observers of such deals say that if Google is making money helping a firm like Aramco even slightly reduce its emissions, society stands to benefit. “The sooner the world ditches gas and goes 100% renewable, the better it is for the environment and public health, but the transition won’t happen overnight,” Johanna Neumann, a senior director with renewable energy advocacy group Environment America, told The Intercept. “In the immediate term, oil and gas companies need to be held accountable for their methane pollution and the sooner they find and seal methane leaks, the better.”

Others are less hopeful. “These efforts certainly sound like they are driven by the bottom-line and not the desire to align businesses with carbon free investments,” said Gregory Trencher, a professor of environmental studies at Kyoto University. “Not touching fossil fuels in any shape or form is generally expected by many divestment players, so helping lower the carbon intensity of transport does not come across as a very impactful action.” Still, he added that “methane leaks in existing infrastructure are very large source of anthropogenic methane emissions. So this is a difficult debate.”

Google’s claims to be helping Aramco decarbonize are complicated by the fact the Saudi-owned company has no apparent interest in doing so. Climate scientists routinely criticize Aramco’s green energy rhetoric as little more than talk, a PR smoke screen obscuring the firm’s role in perpetuating climate change — a role that’s made Aramco a $6.7 trillion company.

A recent New York Times investigation into Aramco found the firm’s eco-friendly initiatives are only part of a broader strategy to keep the planet addicted to Saudi fossil fuels for decades to come. The Times report noted that by reducing peripheral emissions, like methane leaks, Aramco gains the credibility needed to publicly pledge it will itself stop emitting greenhouse gases by 2050. All the while, the theory goes, the massive emissions caused by the continued global consumption of its chief products — oil and gas — will be ignored. “People would like us to give up on investment in hydrocarbons. But no,” Aramco CEO Amin Nasser told the Times.

Aramco even appears to be accelerating its oil and gas work, not moving away from it. According to a 2022 report by Oil Change International, Saudi Aramco greenlighted more new gas and oil projects than any other energy company last year; it is on track to rank No. 3 in the world in expanding its oil and gas operations through 2025.

While Google Cloud software may do what Kurian, the head of the division, says and help Aramco leak less methane into the atmosphere, it could also be helping the company push back on the global scientific consensus that fuel pipelines need to be ditched, not patched, to avoid a climate catastrophe.

“Kurian’s statement that his team is ‘helping oil and gas companies decarbonize in a variety of ways’ is concerning on two levels,” Collin Rees, a senior campaigner with anti-fossil fuel group Oil Change International, told The Intercept. “First, if so they’re pretty bad at their jobs — because we’ve seen almost no meaningful decarbonization in the sector — and second, it implies a continued existence for the sector or an ‘acceptable’ level of emissions, when we know that level must be near-zero.”

Working on ostensibly “green” projects for an oil giant like Aramco allows the company to pretend there is such a thing as eco-friendly fossil fuel, added Kelly Trout, research co-director at Oil Change International. While Google might help Aramco plug leaks, they’re also helping Aramco obscure its role in climate destruction. “The danger of what Google is doing lies in the company misleading the public that technology can render oil and gas ‘safe’ for the climate when only phasing it out can do that,” Trout said.

In other words, Google may be making Aramco’s operations more sustainable in terms of withstanding public relations pressure, not emissions.

There are further signs Google’s joint cloud venture is broadly courting the oil and gas sector; for one, they say it themselves. Google Cloud is sold to the Saudi market via CNTXT, a regional middleman Aramco co-founded with a Norwegian software company that works largely with oil and gas firms. CNTXT’s website directly advertises “cloud-driven digital transformation solutions for Public and Private Sectors and industrial digital transformation solutions asset-heavy industries including: Oil And Gas.”

In his statement to The Intercept, Ladd, the Google spokesperson, defended the entirety of the company’s work for Aramco, including the pipeline project. “This is entirely consistent with the type of work Google Cloud does with energy companies — in this case, helping them track emissions and gas leaks to protect the environment,” Ladd said. “We are not doing work in the exploration and production business with energy firms.”

This is a purported change from Google’s previous business strategy of engaging directly with the extraction portion of the chain. A landmark 2020 Greenpeace investigation accused Google of “helping Big Oil profit from climate destruction,” pointing to the company’s open courtship of upstream business. Prior to 2019, a now-deleted section of Google’s website touted a variety of ways in which the company had helped oil firms pump more oil, like Chevron using “Google’s AutoML Vision Al tools to parse Chevron’s vast data sets and revisit potential subsurface deposits that were previously passed over due to inconclusive or hard to parse data.”

Following the Greenpeace report, Google claimed it will no longer build custom artificial intelligence tools to aid drilling and pumping. The company remains, however, listed as a current member of the Open Subsurface Data Universe, a consortium of oil and tech companies that collaborate using data to improve oil and gas extraction. As of 2020, Google maintained a corporate email address specifically to field requests from consortium members, according to the OSDU’s official newsletter, “In The Pipeline.”

Upstream Versus

Downstream

Google’s defense is based on drawing a careful distinction between so-called upstream processes — pumping of oil and gas out of the ground — and mid- or downstream work, where oil and gas are moved down the supply chain, refined, sold, and eventually burned as fuel. Just a month after the emissions hackathon in Houston, CNTXT CEO Abdullah Jarwan pitched Google Cloud at the Aramco 2022 Downstream Technology & Digital Excellence Awards, according to a LinkedIn post.

Google’s contention that helping only to transport fossil fuels keeps their hands clean from the act of pumping them is a fallacy, according to Josh Eisenfeld of the environmental advocacy group Earthworks. After all, every ounce of methane gas that Google might spare from leaking into the atmosphere is still destined to be burned for fuel.

“Anything that looks at a specific part of the production supply chain without looking at whole chain is perpetuating this disconnect that allows the chain to look cleaner than it is,” Eisenfeld told The Intercept in an interview. “It’s like saying we don’t support the sale of tobacco but helping the transportation of it. You’re still helping that industry look better and exist longer than it should.”

Greenpeace campaigner Xueying Wu agreed, telling The Intercept that “Google’s collaboration with Aramco works against the company’s climate commitments,” and that “it remains unclear how this effort would be separate from Aramco’s oil and gas business. It’s like eating organic food at home while collecting dividends from a pesticide business – there is a contradiction that is impossible to ignore.”

There are other indications that Google’s refusal to aid the upstream supply chain isn’t quite ironclad. According to a LinkedIn post by Kera Gautreau, a senior director with a Houston-based oil consortium that helped judge the emissions hackathon, the involved “teams utilized BlueSky Resources, LLC datasets and Google’s geospatial analytics and machine learning pipelines to solve big decarbonization challenges in upstream oil and gas.”

In late November 2022, CNTXT hosted an informational event for “Aramco Affiliates” with the stated goal of “keeping our heads in the cloud by adopting Google Cloud.” Despite Kurian’s claims that his cloud division wouldn’t do business with the upstream “exploration and production” side of Aramco, the people doing that work appear to have been attendance. The very first comment on CNTXT’s LinkedIn post (“The event was very informative”) is from Mazhar Saeed Siddiqui, whose profile lists him as an exploration system specialist at Saudi Aramco. Also in attendance was Asem Radhwi, who, according to his LinkedIn profile, spent 16 years as a petroleum engineering systems analyst at Aramco.

The Phantom Division

Part of Kurian’s attempt to distance Google from images of blackened oil fields relied on his claim that while they were doing business with Aramco, it wasn’t the part trashing the planet. “We work with Aramco system integration division, not with the oil and gas division,” he told Bloomberg. “We have said that again and again that we don’t work with the oil and gas division within Aramco.” It’s an odd claim, muddled by the fact that there’s no evidence an Aramco system integration division has ever existed. The term appears nowhere on the company’s website, nor has it ever been mentioned in its press releases.

When asked for specific information about this division, Ladd, the Google spokesperson, told The Intercept, “Thomas was referring to a division within Saudi Aramco.” Ladd did not point to anything specific. Aramco’s media relations office, through an unnamed spokesperson, provided only a link to the company’s “digital transformation” webpage, which gives a loose overview of how the company uses various technologies to aid its oil and gas business. To the extent Aramco has any business operations whatsoever outside of directly pumping, transporting, and selling fossil fuels, they appear to be almost entirely technologies designed to aid the pumping, transporting, and selling of fossil fuels, such as developing corrosion-resistant pipeline materials.

In its original announcement of the joint venture, Aramco noted the deal was struck “between Saudi Aramco Development Company, a subsidiary of Aramco, and Google Cloud.” Even if this distinction were meaningful, it doesn’t help Kurian’s case. When the European Commission granted its approval for Cognite, the Norwegian software firm that co-founded CNTXT, to take part in the Saudi cloud deal, it described the Saudi Aramco Development Company as “engaged in the exploration, production and marketing of crude oil and in the production and marketing of refined products and petrochemicals.”

Google’s Aramco justifications require thinking of the energy firm as something other than what it is: a machine engineered to extract, refine, and sell hydrocarbon fuels around the world. Polishing up a portion of this machine may make it seem cleaner, environmentalists argue, but obscures the contraption’s entire purpose.

While it may be hard to walk away from billions of petrodollars in missed cloud services revenue, advocates like Earthworks’s Eisenfeld say there can be no compromise when it comes to averting worst-case climate disaster. “It’s hard to make the argument any oil and gas company can be part of the solution,” he said.

The fundamental business of an entity like Aramco, Eisenfeld explained, is incompatible with the scientific climate consensus. If Aramco wants to provide a “carbon-free future” for the planet of the kind Google is attempting internally, it will have to dismantle its pipelines, not simply keep them from leaking.

“If you’re talking about decarbonizing and not talking about decommissioning, you’re saying, ‘I’m going to drive the climate off a cliff,’” Eisenfeld said.

As Google CFO Ruth Porat put it in 2019, “It should be the goal of every business to protect our planet.”

READ MORE  An accident involving a commercial tanker truck that caused a hazardous material to leak onto Interstate 10 outside Tucson, Arizona, Feb. 14, 2023. (photo: Arizona Department of Public Safety/AP)

An accident involving a commercial tanker truck that caused a hazardous material to leak onto Interstate 10 outside Tucson, Arizona, Feb. 14, 2023. (photo: Arizona Department of Public Safety/AP)

The vehicle was found to be carrying liquid nitric acid, which, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), can cause eye and skin irritation, delayed pulmonary edema, pneumonitis, bronchitis and dental erosion depending on the amount and length of exposure. The chemical is frequently used for manufacturing plastics, dyes and ammonium nitrate for fertilizers, HuffPost reported.

The interstate was immediately closed down, and those within a half-mile radius of the incident were immediately evacuated. Those within a mile were told to shelter in place following the collision, although this order was lifted later that night and then reinstated the next morning. The Arizona Department of Public Safety reported that gassing occurred when crews tried to remove the load of nitric acid from the vehicle. The crews were later able to remove the nitric acid and used dirt to mitigate further gassing.

The evacuation order was lifted on the evening of Feb. 15, and the interstate also reopened at 6:45 p.m.

The Arizona Department of Public Safety has directed those who may have been exposed to toxic fumes from the spill to review guidance from Pima County Health Department.

“If an individual has met that 15 minute or more exposure within a mile of the incident and developed respiratory difficulties or new symptoms (wheezing, shortness of breath; difficulty breathing, exacerbations of COPD or asthma) they should seek medical evaluation,” the Pima County Health Department advised. “It is possible that individuals who lived within a mile of the exposure and sheltered in place but were using air exchange that pulled air from the outside may have met this threshold.”

Local residents are also advised to wipe down outdoor equipment with water for homes within a one-mile radius, although the Pima County Health Department noted, “Concentrations in the immediate area of the spill are low or undetectable. Contamination of objects that were left outdoors is unlikely.”

The cause of the collision is under investigation. The latest update from the Arizona Department of Public Safety identified the driver, who was killed in the incident, and reported that Landstar Inway Inc. was the operating authority of the load being hauled.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.