Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

To end pregnancies, women are enduring clandestine medical procedures, gruelling travel, and fear of arrest.

Minutes after Luisa’s arrival, the Supreme Court issued its ruling overturning Roe v. Wade. Few of the patients knew that the Justices had the authority to take away women’s right to abortion. But when the clinic’s staff broke into tears, it became clear that the morning would not unfold as planned. Sitting alongside other patients, in a row of chairs set against a wall, Luisa looked around nervously. She spoke English haltingly and had never heard of Roe v. Wade. When one of the nurses kneeled by her side to offer an explanation, Luisa froze, in disbelief. Despondent, she left the clinic. As she waited for a ride outside, Luisa recalled that a friend of hers had told her, “If things don’t work out at the clinic, you can always call this man.” Luisa’s friend gave her his number and said that she had gotten an abortion at home with pills that he had provided. Already struggling to support her children, she felt that she was running out of options.

Since the fall of Roe, six months ago, at least sixty-six clinics in fifteen states have closed, limiting the choices of nearly twenty-two million women of reproductive age who reside in them. People from Texas who have the financial means have flown to states like New York or California, where abortion remains legal, to receive the procedure. Others, with fewer resources, have driven to New Mexico, Kansas, or Colorado, nearby states where abortion is also legal. But, for undocumented women, who do not have the resources to travel long distances, the fear of being criminalized, and potentially deported, has become far greater—and so has the need to use underground abortion networks, where the risk of exposure is less.

Several days after Roe was overturned, Luisa picked up her phone and called the man with the pills. She said that he initially asked for a hundred and fifty dollars, then raised the price to a hundred and eighty and eventually to two hundred. All Luisa knew about him was that he was from Mexico, but she agreed to pay the full price and gave him her address. At Luisa’s home, the man handed her seven pills, instructed her to take five of them orally and place two more in her vagina. She said that he offered to do so himself, but Luisa declined. She didn’t know if the man was a doctor or if he had any kind of medical training. After handing him the cash, she inserted some of the pills vaginally, then took the rest that same day. (The man, who declined to be interviewed, denied selling Luisa the pills.)

At first, Luisa felt nothing and went to sleep, but by the next morning she could barely walk. Her vision was cloudy, and she felt weak and dizzy. At home with two of her three children, she lost consciousness. Luisa didn’t know it at the time, but the man’s instructions deviated from those of the Food and Drug Administration. A medication abortion typically involves taking two hundred milligrams of mifepristone, which blocks progesterone, on the first day. On the second or third day, the patient follows up with eight hundred micrograms of misoprostol, which causes uterine contractions. The F.D.A. recommends that the pills be taken until ten weeks of gestation and under the supervision of a health-care provider. Luisa had no idea what medicine, nor what amount, she had taken.

Sitting at home on a recent Tuesday, Luisa recalled how it took her two days to fully recover, and the heavy bleeding continued for two more weeks—far longer than it should have. After a medication abortion, many women experience heavy cramps and bleeding for a few days. If the bleeding persists, or if they experience prolonged nausea, fever, or diarrhea, it is recommended that they visit a doctor to rule out any serious complications. But, with the overturning of Roe, people in Luisa’s situation fear that calling a doctor or visiting an emergency room could result in their arrest.

Luisa also lacked the money to pay a doctor. Beyond rent, her salary primarily went to paying someone to watch her children during the holidays: a woman who charged twenty-five dollars a day per child and, in addition to caring for Luisa’s sons, looked after three others. With her child tax credit, she had bought a used midsize car, and, to make ends meet, she and her children had recently moved to a small apartment in a complex where residents had complained of flooding and busted pipes, moldy surfaces, termites, bedbugs, and rats.

When I visited Luisa and her children in their new apartment, there were some boxes left to unpack, but she had just finished assembling the furniture that she had brought from her previous home—faux-leather sofas, a button-tufted headboard, two king-size mattresses and a glass dining set—which she had paid for in monthly installments over several years. The walls were decorated with large, glittery canvases inscribed with phrases printed in cursive: “Be Daring My Darling” and “She Lived a Life She Loved.” When I asked Luisa if she understood their meaning, she responded with an amused smile: “No.”

Her limited command of English made it hard for her to help her eight-year-old son with homework. This year, his school had nearly expelled him; he constantly disobeyed his teacher’s orders and seemed to be learning next to nothing in class. At home, she spent most of her evenings trying to get him to obey her. As we spoke, the boy, with brown eyes and a curly undercut, repeatedly stormed out of the apartment after she ordered him to stay home.

Halfway into our conversation, Luisa’s phone rang, and she rushed to answer the call. “What are you up to? Aren’t you coming?” she asked, in a hushed voice. When Luisa hung up, she explained that her boyfriend was the one on the other line. They had been dating for almost two years. At times, their relationship felt unsteady, she said. Having the child was never an option for her, but her boyfriend was of a different opinion. “He wanted it, as long as it was a girl,” she said. “But how could I have another child?” She let the question hang before adding, “Not in these conditions.”

A woman whom I’ll call Rosa has the benefits of citizenship, as well as family support. At twenty-seven, she still lives with her parents in the home where she grew up, in Texas. Her sisters, Rosa told me, were her confidantes. Every time she went on a date, they waved her goodbye with a “Cuídate”—“Take care of yourself.” So, when Rosa began to feel ill in mid-July, and nearly fainted at work, she asked her older sister for a pregnancy test. Sitting on the toilet of her home, her eyes fixed on the test’s results window, she watched two red lines emerge. It cannot be, she thought. She hoped that the test might have been too old to use, even though its expiration date had not passed. Rosa asked her sister, who was waiting outside the bathroom, to bring another test. The results were the same. Ya me chingué, she told herself—I’m fucked.

Rosa initially considered raising the child by herself, but she and her siblings had been on welfare as children, and those years weighed heavily on her. “I did not want to rely on the state’s help,” Rosa told me. “I’ve already lived through that.”

Rosa and her sisters huddled around her laptop, typing searches for abortion providers outside of Texas. They had considered trying to buy pills, but they were convinced that their sister could end up in jail, or be considered a murderer, for having an abortion in her home state—so convinced that they closed the laptop after a few minutes, out of fear that their searches would be tracked. Even typing the word “abortion” online seemed like a risk. What better way, the sisters thought, to go after women in Rosa’s situation than to follow their digital footprint.

An arrest in Texas terrified Rosa and her sisters. Lizelle Herrera, a woman roughly their age, had been briefly jailed in April, two months before the overturning of Roe, and charged with murder for causing “the death of an individual by self-induced abortion.” The hospital where Herrera had checked in after taking abortion pills had reported her to the sheriff’s office. In a county where the median household income was roughly thirty-three thousand dollars a year, Herrera’s bond had been set at half a million dollars.

The local district attorney eventually concluded that Herrera could not be prosecuted under Texas law for obtaining an abortion. After a few days, the charges against her were dropped, but fear and confusion surrounding the law remained. “It’s a feeling of helplessness,” Rosa told me. “A feeling of knowing that you have no place to go, so you begin to panic and ask yourself, Who do you trust? Where do you turn to? Who do you seek help from?”

Together with her sisters, Rosa agreed that crossing the border into Mexico and trying to obtain an abortion there was the best option. But the youngest of them had heard rumors that Texas law-enforcement officials were now planning to perform pregnancy tests at border crossings. The rumor, which turned out to be false, caused Rosa to panic. “I’m going to get caught,” she told her sisters, her voice breaking. “What happens if they find out?”

The following day, after a full night’s sleep, Rosa decided that being subjected to a pregnancy test at the border wasn’t as threatening as she feared. That afternoon, she and her older sister crossed the border and visited a Mexican doctor who confirmed that she was five weeks pregnant. When Rosa asked him if he could perform the abortion, the doctor shook his head and declined to name anyone who would, but offered some advice: “If you’re thinking about doing it, do it now.”

Rosa returned home, ultrasound results in hand, feeling ready to share the news with her parents. There was only one problem: she could not confidently say whose child it was. Rosa had recently broken up with a longtime boyfriend and started seeing someone else. To her knowledge, neither man was thinking about fatherhood, so she was at a loss for words when the first question her parents asked was “Y el papá?” For days, her parents refused to speak to her.

Rosa briefly considered going back to Mexico, where she could walk into what her friends called “narco-pharmacies,” which sold abortion pills without a prescription. The thought of travelling to another state, like New Mexico or Colorado, also crossed Rosa’s mind, but the costs of gas, food, and a place to stay seemed prohibitive. Plus, she wondered, what if she got pulled over in Texas and detained along the way? “Money was always the problem,” Rosa recalled. The only money that she had managed to save this year was her tax refund—eight hundred dollars—which she had set aside to straighten her teeth.

Now Rosa planned to spend all of it on her abortion. The problem was that most clinics she found charged six hundred dollars or more for a medical abortion—and that did not include travel costs. Rosa didn’t want to put a strain on her parents’ budget, and borrowing from a friend didn’t feel right either. Everyone she knew in the area lived paycheck to paycheck, and she worried that someone “who happens to be strapped for cash” could file a lawsuit against her, even though the laws in place did not target pregnant women. A Texas statute known as S.B. 8 encourages private citizens to sue individuals who provide, aid, or abet an abortion, and, if successful in court, rewards them with a bounty of at least ten thousand dollars.

Rosa’s oldest sister had heard of a clinic in Mexico City where surgical abortions were performed for less than three hundred dollars. She and Rosa figured that they needed a thousand dollars in total to cover their round trips and accommodations, plus a few hundred more for unforeseen expenses. With her savings, Rosa could only afford part of the trip. So she reached out to the man she was seeing at the time, who agreed that she should get the procedure and covered the rest. The two sisters quickly planned their journey: it was a night-long bus ride to Mexico City, so Rosa decided that they should leave a day early.

After crossing the border by foot, Rosa and her older sister boarded the bus, which made multiple stops along a route that spanned hundreds of miles. Upon their arrival, the sisters headed straight to a small Airbnb, where they spent the night. The following day, they went to a clinic downtown, where nurses prepped Rosa for the procedure and gave her an I.V. She donned a hospital gown and was asked to count to sixty before the anesthesia kicked in. When Rosa woke up, she was on her way to a recovery room where dozens of other patients rested. No one at the clinic questioned or judged her decision. After about an hour, as is typically the case after a surgical abortion, Rosa was discharged from the clinic and went straight back to the Airbnb with her sister to get some rest.

A day later, they boarded a bus back to the U.S. Around three in the morning, heavy abdominal cramps awakened Rosa. The painkillers that she had been given in Mexico City seemed to have worn off. “I kept turning and turning, but it made no difference,” she recalled. “I felt like using the bathroom, but I could barely stand up.” The bumps along the road made it hard to rest or move. And so did her mother’s warning that thieves, who often pose as passengers, could rob the bus at night and strip her of her belongings. Rosa tucked the little cash that she had left inside her bra and eventually fell asleep. By the time she and her sister arrived at the border, it was noon the following day. It took them two hours to cross through a U.S. checkpoint by foot—a wait that only intensified Rosa’s fear. She was carrying the clinic’s paperwork with her, but American immigration officials only asked her cursory questions; no pregnancy tests were ever performed.

At home, Rosa found her bed exactly as she had left it: with a line of pillows meant to ease her discomfort at night. She lay there alone for an hour, as tears streamed down her face. Rosa’s emotions were mixed. Part of her felt like grieving, but she also resented that the state had had a say in one of her most intimate decisions. “How are you feeling? Do you want to take a shower? Will you come eat with us?” her older sister asked, via text, from her own bedroom.

Rosa knew that she was lucky compared to friends who had lived through an abortion alone. Some looked online for instructions on how to take the pills and did so safely on their own. Others ran into complications, because they had used the wrong dosage or didn’t know what to expect. Rosa remembered one call, in particular, from a friend who had reached out to her in a panic, after purchasing pills across the border, before the overturning of Roe. Her friend had taken a set of abortion pills, started bleeding profusely, and worried that she could be hemorrhaging. But she didn’t dare tell anyone else. She, too, had heard of the arrest of Lizelle Herrera and was terrified of going to jail. Instead, she sat in her bathtub alone for several hours to relieve her pain. “Imagine,” Rosa said, “if women refused to seek care during those times, when the clinic was still open, what will become of them now?”

Inside Texas hospitals, doctors and medical personnel are also weighing the legal risks they now face. Shortly after the overturn of Roe, a nursing student who I’ll call Sandra enrolled in an obstetric-care class. Her professors explained how to perform a dilation and curettage, or D. … C., after a miscarriage, but rarely did they mention the word abortion. When state lawmakers visited the school grounds, students were told to not get into politics. “There were things we were not allowed to talk about, things we were not allowed to ask,” Sandra said.

In October, Sandra realized her period was two days late. Immediately, she feared that she was pregnant. Sandra had six months left before she would graduate from nursing school. For years, she had planned to attend law school and specialize in medical cases. After spending the better part of her twenties in an abusive relationship, she became a mom, went through a divorce, and managed to get her career back on track. She had also just started dating a man who was good-natured and shared her passion for health care. When Sandra told him that she had missed her period, he didn’t hesitate to go to the pharmacy and buy her a pregnancy test.

An hour later, in her boyfriend’s bathroom, the couple debated what to do about the test’s positive results. Neither of them felt capable of going through with the pregnancy. Combined, their student debt amounted to half a million dollars, and they had been in a relationship for only three months. Sandra’s boyfriend offered to order abortion pills online, so she didn’t have to leave her home for the procedure. But Sandra was keenly aware that anti-abortion laws in Texas targeted those who assisted pregnant women, and her boyfriend risked facing felony charges and life in prison for providing pills. “We can lose everything,” she warned him.

This was also not the first time that Sandra had faced an unexpected pregnancy: as a teen-ager, she had had an abortion without her parents’ knowledge. As a senior in high school, she felt woefully unprepared to have a child. She also feared her parents’ reaction. At the time, Texas law required minors to have the consent of their parents before undergoing an abortion, so Sandra decided to keep it a secret and wait a few weeks until she turned eighteen. By then, Sandra was past her tenth week—the recommended limit for medication abortions—and she had to find a clinic that would provide a surgical abortion. After a cursory Google search, she found one: a crowded, rickety building, where Sandra waited for half a day to get treatment.

Afterward, the doctor who performed the abortion sent Sandra home with a prescription for antibiotics. But she feared that, if she went to the pharmacy and handed over her insurance card, her parents might be notified. So Sandra decided to forgo the medication. Within a week, she came down with a high fever, and her parents rushed her to the emergency room. There, doctors diagnosed Sandra with a kidney infection. It took two weeks for her to recover from it and be discharged from the hospital. “It was traumatic,” Sandra told me of the experience.

Her understanding of reproductive care had since evolved, but her options were more limited now. Any doctor or person who performed a surgical abortion or provided abortion pills in Texas now faced the possibility of years in jail. Fearing prosecution, she and her boyfriend decided that they were better off travelling to a neighboring state where abortions were still legal. Including the procedure, driving or flying would cost them about a thousand dollars. “It’s a drop in the bucket compared to what we could lose,” Sandra recalled thinking at the time. When she called Planned Parenthood, she learned that the earliest appointment at a clinic in Kansas or New Mexico was weeks away. They suggested a smaller provider in southern New Mexico who offered better news: a doctor could see her within days.

Sandra made plans to fly to El Paso. From there, the couple would rent a car and drive to the clinic just across the border, in New Mexico. Before leaving, Sandra decided to get an ultrasound to confirm how far along her pregnancy was. She chose a clinic that someone she trusted recommended for its free services. After walking in, Sandra was reminded of the home she had grown up in. Abstract paintings hung on the walls, and the waiting room was neatly decorated with velvet sofas and cottage table lamps. A warm-looking woman greeted Sandra, holding her patient file in her arm.

As the woman took notes in a consultation room, Sandra explained to her why this was not the right time for her to have a child. “We’re bleeding money,” she recalled saying, referring to her and her boyfriend’s vast student debt. What would Sandra’s parent think of the abortion, the woman asked. What about her six-year-old son—did he know? Sandra was surprised by the questions, and she felt unsettled when the woman described an abortion that she had had at age twenty as the worst decision of her life. “It haunted me,” Sandra remembered her saying. Sandra was then instructed to lay supine on a table for an abdominal ultrasound. In an instant, the machine started emitting what the woman described as the embryo’s heartbeat.

Confused, Sandra wondered how this could be, since it appeared that she was five and a half weeks pregnant and she had learned in nursing school that health-care workers don’t usually try to detect an audible heartbeat until after the tenth week. And, to add to the confusion, a vaginal ultrasound would typically be used to obtain optimal images at that stage, not an abdominal scan. Sandra wondered, Is it my heartbeat that they’re hearing? She discreetly took her own pulse. “I felt like it was the same as what they were reading,” she said. It was only after Sandra left the office, and the staffer handed her a Bible and a collection of anti-abortion leaflets, that she learned the clinic was run by a Christian group. It was one of dozens of clinics in Texas that lure in unsuspecting women with offers of free medical care but are, in fact, operated by anti-abortion organizations.

Days later, Sandra and her boyfriend boarded a morning flight to El Paso. They drove to the clinic in New Mexico and arrived early for their eleven-o’clock appointment. After half an hour, they left the clinic carrying a set of abortion pills. Sandra took the first pill in New Mexico, before entering Texas. By the time their return flight landed that evening, Sandra had just started to feel the symptoms. “It feels like bad period cramps,” she recalled. Contrary to the predictions of the woman in the anti-abortion clinic, Sandra didn’t hate herself for the decision. It wasn’t a cause for celebration, either, but it felt like the right choice—her own choice. Within three days, she had fully recovered.

Until this year, Sandra had never registered to vote, and never felt that her ballot would make a difference. The Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe changed that. “It just represents women losing their right to make decisions on their own,” Sandra told me. “It feels like we’re going backwards in time.” She and her friends in nursing school had often wondered how much farther abortion restrictions in Texas would go and what other rights women might lose. After the Supreme Court’s ruling, the hands of medical providers in Texas were tied. They could no longer assist patients seeking abortions; it wasn’t even clear whether they could prevent the loss of a mother’s life due to pregnancy complications. For the first time in her life, Sandra voted, casting a party-line ballot of her own creation: all candidates that support a woman’s right to choose.

READ MORE  The January 6 2021, photo the President Donald Trump appears on large screens as supporters participate in a rally in Washington. (photo: John Minchillo/AP)

The January 6 2021, photo the President Donald Trump appears on large screens as supporters participate in a rally in Washington. (photo: John Minchillo/AP)

Committee says Trump’s conduct on January 6 warrants implementation of constitutional ban on him holding office again

ALSO SEE: What We Learned From the January 6 Committee Report

The former US president is again running for the White House and is seen as the leading contender for the Republican party’s 2024 nomination. However, his campaign has been a damp squib so far and his political fortunes battered by the poor performance of Trump-backed candidates in the November midterms and the emergence of rival figures within the party, notably Florida governor Ron DeSantis.

Across 814 pages of the report, published late Thursday night, the Democrat-led committee laid out findings that placed blame squarely on “one man” for the violent events that engulfed the legislative seat of the US government for several hours in 2020.

“The central cause of Jan 6 was one man, former President Donald Trump, whom many others followed,” said the report, released overnight, in a punchy two-sentence summary. “None of the events of Jan 6 would have happened without him.”

In extensive detail, the committee accused the former president of “a multipart plan to overturn the 2020 presidential election”. Trump’s conduct on that day, it says, warrants implementation of a constitutional ban on the New York real estate developer from holding elected office again.

Prior to Jan 6, it continued, Trump and his inner circle engaged in “at least 200 apparent acts of public or private outreach, pressure, or condemnation”, between Election Day and January 6.

On Monday, the committee voted to refer Trump to the Department of Justice on at least four criminal charges, including insurrection and obstruction of an official proceeding of Congress.

The committee also placed blame on domestic law enforcement agencies.

“Federal and local law enforcement authorities were in possession of multiple streams of intelligence predicting violence directed at the Capitol prior to January 6th,” the report says. “Although some of that intelligence was fragmentary, it should have been sufficient to warrant far more vigorous preparations for the security of the joint session.”

Among the evidence presented in the panel’s final report was that there had been 68 meetings, attempted or connected phone calls, or text messages aimed at pressuring state or local officials toward the goal of overturning the election’s results.

“President Trump’s decision to declare victory falsely on election night and, unlawfully, to call for the vote counting to stop, was not a spontaneous decision. It was premeditated,” the report states.

The committee also described how Trump, his campaign and Republican National Committee used claims that the election was stolen to collect more than $250m in political fundraising.

In a bombshell video deposition released earlier this week, former White House communications director Hope Hicks said that Trump knew the claims were false and had dismissed lawyer Sidney Powell’s theories of foreign interference in the election as “crazy”.

The committee, which conducted 1,000 interviews over nearly 18 months, cost taxpayers $3m to September this year, employed around 57 people, and spent hundreds of thousands more on outside consultants and services.

After the findings were published, Trump hit back on his own social media platform with a typically mis-spelt message. “The highly partisan Unselect Committee Report purposely fails to mention the failure of Pelosi to heed my recommendation for troops to be used in D.C., show the ‘Peacefully and Patrioticly’ words I used, or study the reason for the protest, Election Fraud”, Trump posted on Truth Social.

Trump concluded his appraisal of the committee’s work with a question: “WITCH HUNT?”

The January 6 committee’s report offers a clear analysis of the events leading up to that day and a path toward using the 14th amendment against insurrection to bar Trump and his allies from future office.

“Our country has come too far to allow a defeated President to turn himself into a successful tyrant by upending our democratic institutions, fomenting violence, and, as I saw it, opening the door to those in our country whose hatred and bigotry threaten equality and justice for all Americans,” said Mississippi Democratic congressman and committee chair Bennie Thompson in the foreword.

The findings, published days before Republicans take control of the lower legislative house, automatically dissolving the panel, offers the department of justice a comparative text to its own investigation.

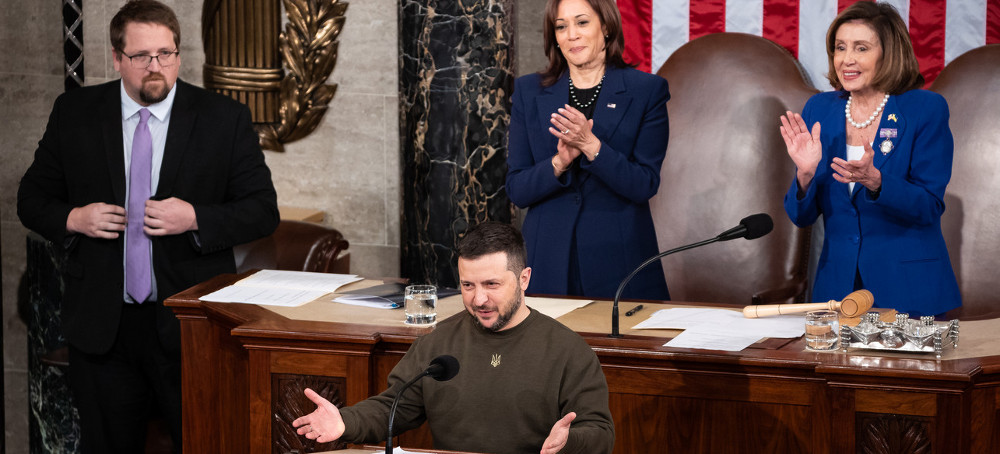

READ MORE  Ukraine president Volodymyr Zelenskyy addresses a joint session of Congress in the House chamber of the U.S. Capitol on Dec. 21, 2022. Behind him, Vice President Kamala Harris and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) applaud. (photo: Francis Chung/Poltico)

Ukraine president Volodymyr Zelenskyy addresses a joint session of Congress in the House chamber of the U.S. Capitol on Dec. 21, 2022. Behind him, Vice President Kamala Harris and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) applaud. (photo: Francis Chung/Poltico)

Fewer than half of House Republicans bothered to show up, and some of them spent much of the speech on their phones.

Reps. Matt Gaetz and Lauren Boebert spent part of the speech glued to their phones and barely paying attention. Several others remained seated for many of the portions of the speech where Zelenskyy received standing ovations, and more didn’t attend the speech at all.

One, Kentucky Rep. Thomas Massie, tweeted prior to the address that he was intentionally missing it while dismissing Ukraine’s war effort. “I’m in DC but I will not be attending the speech of the Ukrainian lobbyist,” Massie said.

In all, roughly 90 House Republicans out of 213—fewer than half—bothered to attend the speech, according to CQ Roll Call.

The response to Zelenskyy’s speech by some GOP politicians and pundits popular with the right-wing base highlighted divisions among Republicans over Ukraine and a host of other issues as they prepare to take control of the House of Representatives and purse strings to decide whether the U.S. continues to help bankroll Ukraine’s war effort.

During his speech before Congress, Zelenskyy was sure to appeal to members of both parties and not just Democrats, who have uniformly supported Ukraine since Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered a full-scale invasion earlier this year.

“I am glad to stress that President Biden supported our peace initiative today. Each of you, ladies and gentlemen, can assist in its implementation to ensure that America’s leadership remains solid, bicameral and bipartisan,” Zelenskyy said.

Anticipating GOP arguments against further funding the war, Zelenskyy described financial assistance to Ukraine as “not charity,” but rather “an investment in the global security and democracy that we handle in the most responsible way.”

But even before Zelenskyy’s speech, the hardline conservatives in the House were downplaying the Ukrainian president’s visit. “Of course the shadow president has to come to Congress and explain why he needs billions of American’s taxpayer dollars for the 51st state, Ukraine,” Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, who also did not attend the speech, tweeted Wednesday morning.

Zelenskyy received several standing ovations during the speech, but Boebert and Gaetz weren’t the only ones who largely remained seated. Reps. Jim Jordan, Andrew Clyde, and more repeatedly stayed in their seats while their colleagues around them jumped to their feet to applaud Zelenskyy, according to Axios.

At one point, Clyde, a George Republican, refused to stand even when encouraged by Jordan.

Some Republicans praised Zelenskyy’s speech, including Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick, who told The Hill that the Ukrainian president had “overwhelming support” from Congress and would “continue to have that.”

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell said in a floor speech before the address that he looked forward “to hearing from the Ukrainian people’s elected leader at a critical moment in their struggle for their safety and sovereignty against Russia’s unhinged aggression,” and he accompanied Zelenskyy on his way into the House chambers along with Democratic Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer.

Tucker Carlson, the in-house pundit of the far-right GOP, launched a full-throated attack on Zelenskyy during his Wednesday night broadcast. Carlson said the Ukrainian president, who wore a crewneck sweatshirt with the Ukrainain emblem, was “dressed like the manager of a strip club,” accused him of “waging a war against Christianity” in Ukraine, and compared him to Sam Bankman-Fried, the FTX cofounder indicted for fraud and money laundering who has nothing in common with aside from being Jewish.

After the speech, Boebert and Gaetz struck a more conciliatory tone than Carlson, applauding Zelenskyy for fighting for Ukraine while dismissing colleagues who are in favor of funding the war as anti-American.

“President Zelenskyy should be commended for putting his country first, but American politicians who indulge his requests are unwilling to do the same for ours,” Gaetz said in a statement following the speech. “He did not change my stance on suspending aid for Ukraine and investigating fraud in transfers already made.”

“President Zelenskyy is working to protect his country, his border, and his people. I get it,” Boebert said. “I really just wish our commander in chief would do the same right here at home.”

READ MORE Shipping containers topped with concertina wire, built on federal land by Republican Gov. Doug Ducey, along the U.S.-Mexico border in the Coronado National Forest near Hereford, Arizona, Dec. 20, 2022. (photo: Patrick T. Fallon/Getty)

Shipping containers topped with concertina wire, built on federal land by Republican Gov. Doug Ducey, along the U.S.-Mexico border in the Coronado National Forest near Hereford, Arizona, Dec. 20, 2022. (photo: Patrick T. Fallon/Getty)

After being shut down by local protesters, Ducey told a federal judge he would remove the shipping container wall.

State and federal officials, in a joint filing this week, informed a judge in Arizona’s U.S. district court that a process to dismantle the governor’s unlawful barrier would soon begin. Following weeks of fierce local resistance on the ground, the agreement will ironically make Ducey — a Republican who declared his state under invasion — the first U.S. lawmaker to initiate a large-scale border wall removal in modern American history.

Andy Kayner and Jennifer Wrenn, who live just north of the container wall, tempered their reactions to the news. The couple has been at the center of the battle to halt the governor’s project, fueled by outrage over the harm that was done to a landscape they treasure and the endless convoys of trailer-pulling trucks rumbling past their home day and night.

“Obviously, we’d love to see the wall totally gone,” Kayner told The Intercept. “Open that space back up for a wildlife corridor.”

On the one hand, Wrenn said, the agreement was clearly a win for the local residents who protested, as well as their wider network of supporters. On the other, she worried that Ducey, who leaves office at the end of the year, will slow-roll his deinstallation effort, leaving his Democratic successor, Gov.-elect Katie Hobbs, to clean up the mess. “How much can he remove before January 5?” Wrenn asked, referring to Hobbs’s inauguration date.

Precisely how much Ducey’s entire endeavor has — and will — cost Arizonans remains to be seen. In October, the governor’s office told The Intercept the installation of the wall in Coronado National Forest, south of Tucson, would cost $95 million. Combined with a separate, smaller, equally unlawful project in Yuma, total contracted costs for container wall installation in Arizona over the past year has been $123.6 million. Removal and remediation costs associated with taking the containers down could drive the overall total up even further.

Ducey should be the one footing the bill, Wrenn argued. “Taxpayers shouldn’t have to pay for putting it in, then taking it out,” she said, “and then restoring the land and restoring all the roads.”

Ducey first began stacking multi-ton shipping containers along the border in Coronado National Forest, in Cochise County, in late October despite being informed multiple times by federal officials in the U.S. Forest Service that his project was unauthorized and thus illegal.

In a lawsuit targeting the Biden administration’s top land management agencies, Ducey argued that a century’s worth of legal agreement that the border in Southern Arizona is federal property was wrong. The state had jurisdiction over the land, he contended, and because he declared a state of emergency resulting from a purported “invasion,” he was within his rights to disregard federal laws and authorization requirements surrounding construction in the national forest. (The litigation is ongoing).

In a span of a month and a half, Ducey placed nearly 4 miles of shipping containers across federally protected jaguar habitat entirely unimpeded. By all indications, he was on track to complete a 10-mile wall through the stunning San Rafael Valley when his march was halted by a network of local residents frustrated with the absence of a federal response. Kayner and Wrenn were among them, parking their pop-up camper near the contractors’ vehicles and spending several nights at the site with other local activists and allies.

Beginning on December 5, the demonstrators’ continued presence ended construction at the site. The week after the shutdown began, the Department of Justice filed a lawsuit against Ducey and Arizona’s Department of Emergency and Military Affairs over the container wall. In order to avoid the injunction that the suit called for, Ducey and the state entered into the agreement that was laid out in federal court this week.

The brief, two-page stipulation says that by January 3, Arizona “to the extent feasible” will remove all containers and equipment related to the much smaller installation in Yuma. The agreement calls for the same removal process for the much larger Coronado National Forest installation, though it does not include a target end date for those efforts.

In comments to the New York Times on Wednesday, Ducey’s press secretary, C.J. Karamargin, implied that the governor’s project had achieved its objective in pressuring the Biden administration to fill gaps in the border wall more quickly. “We’ll happily remove them if the federal government gets serious and does what they’re supposed to do, which is secure the border,” Karamargin said of the governor’s containers. “We now have indications that they’re moving closer, that they’re more serious.”

In a briefing in late July, Customs and Border Protection officials said that the Biden administration was beginning a “remediation” process along the border that would include filling “small” gaps in the border wall in select areas, in addition to various road and environmental repair projects. Contrary to Karamargin’s suggestion this week, a Customs and Border Protection public affairs officer John Mennell told The Intercept that the agency has made no changes to its plans because of Ducey’s Coronado project. Those plans, available online, do not describe erecting a border wall where the governor placed the containers.

For Kayner and Wrenn, the story of Ducey’s containers — how they came to cross Coronado National Forest and what stopped them from going any further — are linked to issues that go beyond the border and immigration. It’s the way in which the governor’s illegal wall, cleaving a vital desert ecosystem in half as it did, created yet another threat to biodiversity in an era of mass extinction. “We’d love to see dialogue about what we’re going to do with that area long term,” Kayner said. “Let’s just talk about being a little kinder to the wildlife, who’ve got no seat at the table.”

Wrenn, meanwhile, linked the container wall to events in Washington. “This was a perfect counterpoint to the insurrection and the January 6 Committee,” she said. “This was the politicians violating the rule of law, and ordinary citizens — being peaceful, lawful, and legal — taking it into their own hands and helping preserve democracy in our country.”

Ducey’s sudden reversal on the project raises a series of questions. What if the Department of Justice had sought an injunction sooner? How much money could have been saved? And how much damage to the environment — and the credibility of the U.S. Forest Service and the laws it’s meant to enforce — could have been prevented?

One thing that is clear, Wrenn said, is that Ducey’s wall became the catalyst for something unforgettable. “When we realized that this wasn’t just a protest, that we could actually sit down in the road and stop it, it was this biggest eureka moment,” she said. “After hundreds and hundreds of protests I’ve been to in my life, I’ve never felt that — that this was real, that this had direct positive impact.”

READ MORE  Amazon Labor Union President Chris Smalls attends the premiere of Apple Original Films' "Emancipation" at Regency Village Theatre on November 30, 2022, in Los Angeles, California. (photo: Amy Susan/WireImage)

Amazon Labor Union President Chris Smalls attends the premiere of Apple Original Films' "Emancipation" at Regency Village Theatre on November 30, 2022, in Los Angeles, California. (photo: Amy Susan/WireImage)

"We're very well-prepared for the long haul of this battle," he said. "We understand the odds...of getting a company like Amazon to come to the table" are long. "At the same time, we're in a different point in history when it comes to organizing. Amazon, Apple, Starbucks, Trader Joe's, you name it – all these workers and industries are coming together now. Corporations have no choice but to realize this movement isn't going to stop and we're not going to rest until we rightfully get what we deserve."

The ALU won a historic victory at JFK8, a Staten Island, N.Y., warehouse, in April. However, the union's lost two elections since, one near Albany, and one at another Staten Island warehouse. These losses are "growing pains," Smalls told Yahoo Finance.

"The only way we're going to get Amazon to come to the table is by taking shots and taking risks, and that happens by workers being ready to organize in their respective facilities," said Smalls. "For us, whatever campaign is ready to go, the Amazon Labor Union is going to throw their support behind it, no matter what...We know that it's going to take collective action for Amazon to come to the table. So, for us, it's never unsuccessful. These are growing pains, and we're going to fight and continue to grow."

Meanwhile, Amazon spokesperson Kelly Nantel said in a statement to Yahoo Finance: “We strongly disagree, and as we showed throughout the JFK8 Objections Hearing with dozens of witnesses and hundreds of pages of documents, both the NLRB and the ALU improperly influenced the outcome of the election, and we don’t believe it represents what the majority of our team wants.”

'Same struggle, but a different mission'

When it comes to JFK8, the ALU's in a holding pattern, awaiting legal certification so that they can to go into bargaining.

"At the current moment, we're waiting to be certified," he said. "We've been in court ... Any time, any day that they certify us, we're going to immediately put in a bargaining order for Amazon to come to the table as soon as that happens. So, we're waiting."

Smalls, in the meantime, is expecting the ALU to continue its own union battles this year. But he insisted it will remain independent for now. Big labor organizations like the Teamsters and the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union have been involved unionization efforts at Amazon. But Smalls is planning on steering clear from partnerships.

He added: "The way we organize ... our culture was created and solely run by Amazon workers, putting them in the driver's seat. We have a different mission – the same struggle, but a different mission."

READ MORE  Convention president Elisa Loncon (right, standing beside vice president Jaime Bassa), calls for a moment of silence to honor those who lost their lives in the struggle for a better Chile, July 4, 2021. (photo: Rodrigo Garrido/Reuters)

Convention president Elisa Loncon (right, standing beside vice president Jaime Bassa), calls for a moment of silence to honor those who lost their lives in the struggle for a better Chile, July 4, 2021. (photo: Rodrigo Garrido/Reuters)

Two Constitutional Convention representatives reflect on the process of drafting the world’s most progressive constitution.

Ahead of the September 4 plebiscite, I spoke with two representatives to capture in their own words the momentous formation of the constituent assembly. Elisa Loncon is a Mapuche linguist and Indigenous activist who was elected as the Constitutional Convention’s first president. Alondra Carrillo Vidal is a psychologist, feminist activist, and vocera (spokesperson) of the Coordinadora Feminista 8M, one of the organizations that has spearheaded Feminist General Strikes coinciding with International Women’s Day on March 8. Loncon’s historic leadership came to represent the political possibilities of plurinationalism for the Mapuche, the largest Indigenous group in Chile, and other socially marginalized Indigenous groups from the Aymara to the Rapa Nui. Carrillo participated in the formation of Movimientos Sociales Constituyentes (Social Movement Constitutionalists), a bloc within the Convention made up of representatives of multiple social movements.

In this interview, Loncon and Carrillo describe the significance of their work for their constituents and for their country as they sought to meet and mediate the possibilities of this historic process. Even though the national plebiscite rejected the draft constitution that they worked on, the rethinking of social rights and state organization articulated in the document’s 388 articles continues to inform public and political debate as Chileans negotiate the next phase of this process. This interview reflects not only what was possible but what is still possible, for the ideas produced in the 2022 draft constitution will not simply evaporate.

Romina Green Rioja: As movement representatives, what has been your experience in the Constitutional Convention?

Elisa Loncon: First, I must highlight the experience of being the first woman and Mapuche president of a constituent body. This resulted in great recognition of the Mapuche people on the part of Chileans and an unprecedented positioning of our historical demands within a democratic space.

Second, I must note that the convention stood out for being a democratic body that represented the various social sectors of Chile, in terms of gender parity, decentralization, and diversity of peoples, in a way we had never seen. All the political forces within the Convention were in the minority, and no one had veto power, which is why it became a space for dialogue and agreements between the different political groups, mostly independents from the left and center. Right-wing positions were always in the minority. And the pre-existing peoples or nations of Chile also participated in this dialogue for the first time.

As Indigenous peoples, we had the task of bringing into the new constitution the international agenda in terms of Indigenous rights. To enshrine rights, we carried out a cross-cutting political dialogue with various sectors working in support of human and social rights. The Right abstained and voted against the norms on the collective rights of the peoples.

Alondra Carrillo Vidal: The Coordinadora Feminista 8M, for which I am a spokesperson, held a long discussion process before deciding to run for the Convention. Once we decided to do it, and that we would do so through independent slates, our organizational trajectory intersected with the efforts of the territorial assemblies of electoral district 12, a district that I lived in until 2021. These assemblies, together with the Coordinadora and other territorial and social organizations in the district—such as the Movement for Water and the Territories (MAT), organizations of retirees fighting for decent pensions (No+AFP), and organizations representing youth and sexual and gender dissidents—put together a slate and decided that the candidates elected to the Convention had to be spokespersons of the organized territory. So that was my job.

We had an agenda: the Feminist Program Against the Precariousness of Life. I was responsible for defending and promoting that agenda within the Convention. Beginning during the campaign and then once elected to the Convention, I linked up with others who came from similar programmatic spaces to form Movimientos Sociales Constituyentes. And, to ensure feminist norms were drafted together with feminists from the different groups, I was part of the push for the formation of the Feminist Collective, a politically diverse space.

At the same time, from my position as spokesperson of the Coordinadora, I maintained constant connection with feminist organizations that presented popular proposals for constitutional norms, a mechanism for meaningful participation. And I tried to build bridges to bring together the efforts of the feminists in the Convention and the organizations in the movement.

RGR: Can you describe a specific special or challenging moment during Convention?

EL: As president, it was my responsibility to confirm the two-thirds majority vote on all constitutional norms. This threshold was a legacy of the 1980 Constitution, which is why it was highly resisted by those on the left. There was pressure from the Left, the Communist Party, and representatives from social movements to change the vote threshold. But my position was to be faithful to the constitutional mandate. We could not go against the mandate because then we would be acting unconstitutionally. We had to ratify with a two-thirds majority, and that’s what happened. It would have been a serious mistake to have done otherwise.

We Indigenous peoples participated in the Convention as independents, and we did not have longstanding political teams. We had to find the best lawyers and Mapuche and Indigenous scholars among our people to communicate our demands to a group of people who did not know about Indigenous peoples. As Convention president I had a very small team of people with political experience, unlike the members of political parties that were previously part of different governments, who had political thinktanks. Of course, these were not conditions of equality. But it was possible to influence the democratic dialogue, due to Indigenous peoples’ strategy. The Mapuche people, for instance, put one representative in each of the Convention’s drafting commissions and provided them with collective support and follow up.

ACV: There were certainly many challenging moments, and the ones that come to mind are similar to the ones that Elisa mentioned. I will mention two. The first was when I suddenly became aware, together with my neighbors, that, given the composition of the Convention, the task of drafting the constitution was real. It was not just a matter of going to put ideas on the table or present aspects of our agenda, but rather about being direct participants in drafting the constitution. I know it may sound a bit strange, but I think that as popular organizations we always imagined a deepening of the revolt’s spirit of tearing down the old, and we were not necessarily so clear about the leading role we would have to play in the Convention and its role in building the new.

A second challenging moment, perhaps more personally but also collectively, was when we broke into thematic commissions to write the text. As Movimientos Sociales Constituyentes members, we decided to distribute ourselves throughout all the commissions, and my task was to participate, together with Alejandra Flores, in the Political System Commission. For this commission, the social movement did not have a defined mandate. We had to build a democratic process to construct that mandate collectively. Imagining and organizing such a process, and building pedagogical texts to deliberate with residents on issues as far removed from everyday life as the political system, was undoubtedly a huge challenge.

RGR: Has the Convention changed and/or expanded the politics of the feminist and Mapuche movements?

EL: Yes. The Convention served to broaden Mapuche and Indigenous politics as well as the perspective of the political parties and leaders who were challenged by the peoples in terms of recognition of the rights of plurinationality and the collective rights of Indigenous peoples.

There were agreements with feminists, social movements, and parties to support the norms about Indigenous peoples. The Indigenous movement also faced the challenge of breaking with colonial traditions imposed on the Indigenous world and especially on women. A special case was recognizing the reproductive rights of Indigenous women as a non-patriarchalized form of traditional knowledge, and we voted to approve the norm referring to women’s right to sexual and reproductive health.

Coexisting with non-Indigenous women also allowed us to see that there are different feminist political positions, some of which are very conservative and indifferent to Indigenous women’s demands for collective rights. And, even with gender parity, not all women are feminists; right-wing women are so conservative that far from seeking social change, they hinder it.

READ MORE Cleaner trucks will mean better air and health for overburdened communities. (photo: Jose Luis Magana/Mom's Clean Air Force)

Cleaner trucks will mean better air and health for overburdened communities. (photo: Jose Luis Magana/Mom's Clean Air Force)

Cleaner trucks will mean better air and health for overburdened communities.

The agency’s new rule, part of its larger Clean Trucks Plan, is the first time pollution standards for semi trucks, delivery trucks, and buses have been updated in more than 20 years. It will go into effect when 2027 vehicle models are made available for purchase.

Although heavy-duty vehicles represent less than 5 percent of vehicles on the nation’s roads, they are major emitters of nitrogen oxides, a group of polluting gases that play a significant role in the formation of smog. In high concentrations, nitrogen oxides are known to contribute to heart disease, allergies, asthma, and other lung diseases.

The EPA’s rule will for the first time require manufacturers to adopt newer technology that reduces pollution from trucks when they are idle, driving at low speeds, or navigating stop-and-go traffic. By 2045, the agency estimates that heavy-duty vehicle nitrogen dioxide emissions will decrease by 48 percent as a result of the rule. The regulation is also expected to prevent up to 2,900 deaths by 2045.

Low-income people of color are more likely to live and work in neighborhoods close to major highways and roads, shipping corridors, and areas with large numbers of factories and warehouses — places where heavy-duty trucks create the most pollution. That’s because of the legacy of racist redlining and zoning laws that left many Black and brown families with few other housing options. The construction of the nation’s interstate highway system also targeted neighborhoods where communities of color were concentrated. And in some cities, bans on trucks on certain highways simply pushed them into already-burdened neighborhoods.

“These communities have waited decades for action,” Katherine García, the director of the Sierra Club’s clean transportation campaign, told Grist.

But in recent years, in spite of overall stricter emissions standards for personal vehicles, communities that have fought for years for cleaner, more breathable air have faced setbacks. The rise in global e-commerce — exemplified by online giants like Amazon — has led to an explosion in warehouses, and their attendant delivery trucks, across the country. These “logistics hubs,” designed to accommodate constant consumer demand, frequently end up in areas with loose zoning regulations, cheap land, and a high proportion of low-income people of color living nearby.

California’s Inland Empire, east of Los Angeles, is the home to the nation’s largest concentration of warehouses. The region is also infamous for having the nation’s worst ozone and particle pollution. Residents and advocates here have drawn a link between consumer demand for goods and the hundreds, if not thousands, of trucks that travel their roads on a daily basis. These trucks end up driving past and idling by schools, parks, and homes, exposing residents to more air pollution. Earlier this year, a cohort of the region’s cities extended moratoriums on warehouse construction to take time to assess the purported economic benefits and the very real environmental impacts of these developments.

“We need systemic change, and we need to just clean up these trucks, and we have the solutions,” Melody Reis, the senior legislative manager at Moms Clean Air Force, a national organization that advocates for cleaner air, told Grist.

“Inaction is injustice for these communities,” said Reis, “and this rule should make a tremendous amount of difference.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.