Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

ALSO SEE: Lula’s Victory Likely Means Big Changes for Brazil,

Though His Specific Plans Are Vague

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the former leftist president, has reclaimed the leadership and vowed to reunify his country

With 99.97% of votes counted, Silva, a former factory worker who became Brazil’s first working-class president exactly 20 years ago, had secured 50.9% of the vote. Bolsonaro, a firebrand who was elected in 2018, received 49.10%.

Addressing journalists at a hotel in São Paulo, Lula vowed to reunify his country after a toxic race for power which has profoundly divided one of the world’s largest democracies.

“We are going to live new times of peace, love and hope,” said the 77-year-old, who was sidelined from the 2018 election that saw Bolsonaro claim power after being jailed on corruption charges that were later annulled.

“I will govern for 215m Brazilians … and not just for those who voted for me. There are not two Brazils. We are one country, one people – a great nation,” he said to applause. “It is in nobody’s interests to live in a country that is divided and in a constant state of war.”

A few streets away on Paulista Avenue, one of the city’s main arteries, ecstatic Lula supporters gathered to celebrate his victory and the downfall of a radical rightwing president whose presidency produced an environmental tragedy and saw nearly 700,000 Brazilians die of Covid.

“Our dream is coming true. We need to be free,” beamed Joe Kallif, a 62-year-old social activist who was among the elated throng. “Brazil was in a very dangerous place and now we are getting back our freedom. The last four years have been horrible.”

Gabrielly Soares, a 19-year-old student, jumped in joy as she commemorated the imminent victory of a leader whose social policies helped her achieve a university education.

“I feel so happy … During four years of Bolsonaro I saw my family slip backwards and under Lula they flourished,” she said, a rainbow banner draped over her shoulders.

Ecstatic and tearful supporters of Lula – who secured more than 59m votes to Bolsonaro’s 57m – hugged and threw cans of beer in the air.

“This means we are going to have someone in power who cares about those at the bottom. Right now we have a person who doesn’t care about the majority, about us, about LGBT people,” Soares said. “Bolsonaro … is a bad person. He doesn’t show a drop of empathy or solidarity for others. There is no way he can continue as president.”

There was celebration around the region too as leftist allies tweeted their congratulations. “Viva Lula,” said Colombia’s leader, Gustavo Petro.

Argentina’s president, Alberto Fernández, celebrated “a new era in Latin American history”. “An era of hope and of a future that starts right now,” he said.

Mexico’s president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, commemorated what he called a victory for “equality and humanism”.

Joe Biden issued a statement congratulating Lula on his election “following free, fair and credible elections”.

“I look forward to working together to continue the cooperation between our two countries in the months and years ahead,” the US president said.

Justin Trudeau said: “The people of Brazil have spoken. I’m looking forward to working with @LulaOficial to strengthen the partnership between our countries, to deliver results for Canadians and Brazilians, and to advance shared priorities – like protecting the environment. Congratulations, Lula!”

Brazil’s former president Fernando Henrique Cardoso, who governed before Lula’s historic election 20 years ago, tweeted: “Democracy has won, Brazil has won!”

The French president, Emmanuel Macron, said Lula’s election “kick starts a new chapter in Brazil’s history” while Spain’s prime minister, Pedro Sánchez, called Lula’s triumph a move towards “progress and hope”.

The speed of the international reaction reflected widespread fears that Bolsonaro, a former army captain who has spent years attacking Brazil’s democratic institutions, might refuse to accept defeat. In the lead up to the election he indicated he would contest a result he considered “abnormal”. He is yet to concede to his rival.

Outside Bolsonaro’s home in west Rio there was dejection and anger as the news sunk in. “I’m angry,” said Monique Almeido, a 36-year-old beautician. “I don’t even know what to say.”

João Reis, a 50-year-old electrician, said he was convinced the vote had been rigged.

“It’s fraud without a doubt, they manipulated the count. The armed forces must intervene,” he demanded.

And if they didn’t? “The population must take to the streets to demand military intervention so that we don’t hand power over to the communists.”

At Lula’s celebrations the mood was very different as the veteran leftist vowed to wage war on hunger, racism and to combat environmental destruction which has soared under Bolsonaro. “We will fight for zero deforestation in the Amazon … Brazil and the planet need the Amazon alive.”

“We are going to restart the monitoring and surveillance of the Amazon and combat any kind of illegal activity,” he vowed. “We are not interested in a war over the environment but we are ready to defend it from any threat.”

A team of Ukrainian soldiers armed a drone with bombs on Friday during a mission that destroyed a Russian armored personnel carrier on the front lines in the country’s southern Kherson region. (photo: Finbarr O’Reilly/NYT)

A team of Ukrainian soldiers armed a drone with bombs on Friday during a mission that destroyed a Russian armored personnel carrier on the front lines in the country’s southern Kherson region. (photo: Finbarr O’Reilly/NYT)

In the southern Kherson region, Ukraine now has the advantage in range and precision guidance of artillery, rockets and drones, erasing what had been a critical Russian asset.

"What a beautiful explosion,” said First Lt. Serhiy, a Ukrainian drone pilot who watched as his weapon buzzed into a Russian-controlled village and picked off the armored vehicle, a blast that was audible seconds later at his position about four miles away.

“We used to cheer, we used to shout, ‘Hurray!’ but we’re used to it now,” he said.

The war in Ukraine has been fought primarily through the air, with artillery, rockets, missiles and drones. And for months, Russia had the upper hand, able to lob munitions at Ukrainian cities, towns and military targets from positions well beyond the reach of Ukrainian weapons.

But in recent months, the tide has turned along the front lines in southern Ukraine. With powerful Western weapons and deadly homemade drones, Ukraine now has artillery superiority in the area, commanders and military analysts say.

Ukraine now has an edge in both range and in precision-guided rockets and artillery shells, a class of weapons largely lacking in Russia’s arsenal. Ukrainian soldiers are taking out armored vehicles worth millions of dollars with cheap homemade drones, as well as with more advanced drones and other weapons provided by the United States and allies.

The Russian military remains a formidable force, with cruise missiles, a sizable army and millions of rounds of artillery shells, albeit imprecise ones. It has just completed a mobilization effort that will add 300,000 troops to the battlefield, Russian commanders say, though many of those will be ill trained and ill equipped. And President Vladimir V. Putin has made clear his determination to win the war at almost any cost.

Still, there is no mistaking the shifting fortunes on the southern front.

Ukraine’s growing advantage in artillery, a stark contrast to fighting throughout the country over the summer when Russia pummeled Ukrainian positions with mortar and artillery fire, has allowed slow if costly progress in the south toward the strategic port city of Kherson, the only provincial capital that Russia managed to occupy after invading in February.

The new capabilities were on display in the predawn hours Saturday when Ukrainian drones hit a Russian vessel docked in the Black Sea Fleet’s home port of Sevastopol, deep in the occupied territory of Crimea, once thought an impregnable bastion.

The contrast with the battlefield over the summer could not be starker. In the Donetsk region of eastern Ukraine, Russia fired roughly 10 artillery rounds for each answering shell from Ukrainian batteries. In Kherson now, Ukrainian commanders say the sides are firing about equal numbers of shells, but Ukraine’s strikes are not only longer range but more precise because of the satellite-guided rockets and artillery rounds provided by the West.

“We can reach them and they cannot reach us,” said Maj. Oleksandr, the commander of an artillery battery on the Kherson front, who like others interviewed for this article gave only his first name for security reasons. “They don’t have these weapons.”

Falling rates of Russian fire also speak to ammunition shortages, he said. “There is an idea the Russian army is infinite, but it is a myth,” he said. “The intensity of fire has fallen by three times. It’s realistic to fight them.”

A main highway approaching Kherson city from the west has become a thoroughfare for Ukrainian artillery, with towed howitzers, truck-mounted howitzers and trucks laden with grad rockets rumbling by continually through the day.

American-provided M777 howitzers firing precision-guided shells and striking up to 20 miles behind Russian lines have forced the Russians to stage heavy equipment farther from the front. Ukrainian drones spot infantry but fewer tanks or armored vehicles near the front line, said First Lt. Oleh, the commander of a unit flying reconnaissance drones. “We hear a lot of rumors they are abandoning the first lines of defense.”

This firepower has tipped the balance in the south, raising expectations that a long-anticipated assault on Kherson is drawing near — though a swirl of apparent misdirection from military leaders on both sides has clouded the picture.

The terrain around the city — table-flat steppe with thin tree lines and little cover, and crisscrossed by irrigation canals that can be used as trenches — favors its Russian defenders. And Ukrainian commanders and officials have been dropping hints of an impending attack since the spring, only to have the fighting drag on.

But the city lies on the west bank of the Dnipro River, making its defenders reliant on bridges to Russian territory on the eastern bank that now lie within easy range of Ukrainian rocket artillery and, for the most part, are now unusable. That has made the Russian grip precarious. But President Putin has reportedly overruled his generals’ recommendations of a retreat to safer and more easily defended ground on the east bank.

A Ukrainian soldier passing the window of a school that was used as a base by Russian forces in Velyka Oleksandrivka, in the Kherson region of Ukraine. (photo: Ivor Prickett/NYT)

A Ukrainian soldier passing the window of a school that was used as a base by Russian forces in Velyka Oleksandrivka, in the Kherson region of Ukraine. (photo: Ivor Prickett/NYT)

Government spokesperson Steffen Hebestreit said during a regular government press conference on Monday that using “hunger as a weapon” by suspending grain deliveries is “deeply despicable,” calling on Russia to resume its participation and consider an extension of the deal.

The grain deal has made more than seven million tons of grain available on world markets according to government spokesperson Andrea Sasse.

“We are doing everything in our power to ensure that transport by sea remains possible,“ the spokesperson said, adding that land transport will be continued.

German Defense Minister Christine Lambrecht said in a tweet Monday that “Russia must not get away with this!“ and that Europe is “committed to stability - also in the food supply.”

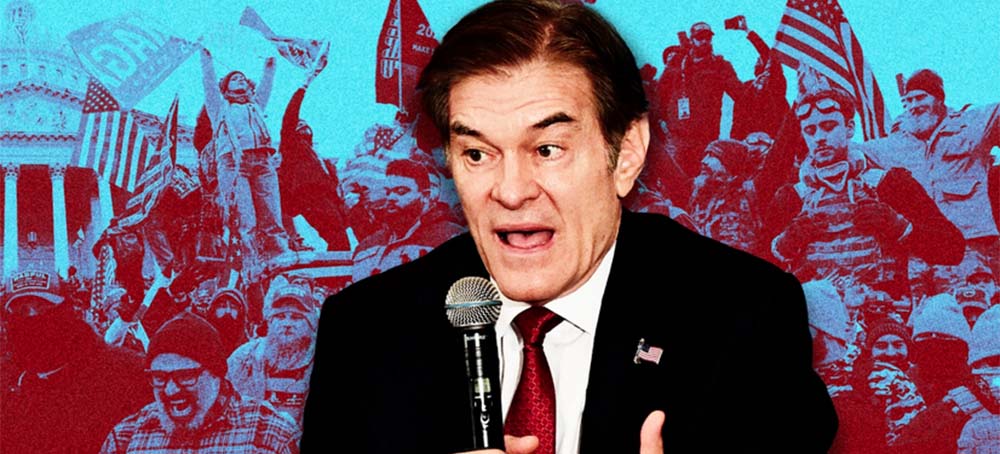

Dr. Oz. (image: Rolling Stone/Getty Images)

Dr. Oz. (image: Rolling Stone/Getty Images)

The Republican has kept his distance from the "stolen election" lie while running for Senate, but records obtained by Rolling Stone reveal some of his staffers have embraced it wholeheartedly — and even attended the Jan. 6 rally to overturn the election

Oz’s tact is a departure from the state’s other high-profile Republican, Doug Mastriano, who’s running for governor with a rapturous embrace of Trump’s election lies. But it’s Oz’s approach that appears to be working: While the polls show Mastriano floundering, Oz is running a close race against Democrat John Fetterman.

But while Oz pays lip service to the 2020 election results, he has quietly loaded up his 2022 campaign with true believers in Trump’s “Big Lie” — including ones who attended Trump’s infamous Jan. 6 rally aimed at nullifying Joe Biden’s victory.

According to records reviewed by Rolling Stone, at least two Oz campaign staffers attended Trump’s Jan. 6 “Stop the Steal” rally in Washington, D.C. The rally, in which Trump declared the election stolen and encouraged supporters to “fight like hell” to pressure Vice President Mike Pence to overturn it, directly preceded the deadly Capitol riot.

Lee Snover, described as Oz’s campaign coordinator for Northampton County, attended the Jan. 6 “Stop the Steal” rally on the mall and said she walked to the Capitol that day but did not trespass on Capitol grounds. “I got to the Capitol steps,” she told Lehigh Valley Live that day. “The only violence I saw were the police teargassing patriots for no reason.”

Neither Snover nor Oz’s campaign responded to multiple requests for comment.

Snover, who serves as Northampton County GOP chair, does not appear in Federal Election Commission records as a paid Oz staffer, but she has been identified as Oz’s local campaign coordinator in media reports.

Four days before she attended Trump’s “Stop the Steal” rally in D.C., Snover participated in a Zoom call with hundreds of state legislators from swing states where Trump, Rudy Giuliani, Peter Navarro, and John Eastman laid out plans on how to “decertify” their states’ results and stop the counting of electoral votes in Congress.

“It was an informative call. It was all fact-based, informative. It was really not even a political call,” Snover said in a conservative-talk-radio appearance two days before the insurrection. In the interview, Snover dismissed state election officials as unpersuadable and said that Republicans’ focus should remain on getting state legislators to urge Pence not to count their state’s votes. “That’s why we need the state legislators to do it. The secretaries of state are never going to change it.”

Another Oz staffer, Josh Bashline, who serves as a paid political adviser, also attended Trump’s Jan. 6 “Stop the Steal” rally, according to an interview he gave to a local newspaper. Bashline initially helped the Oz campaign as a volunteer poll watcher during his primary contest with David McCormack, but FEC records show the staffer stayed on the payroll at least as recently as Sept. 30.

The discrepancy between Oz and his staff on Trump’s election lies mirrors Oz’s own double-speak on what really happened in 2020.

During his narrowly won Republican primary run, Oz leaned heavily into rhetoric that the election still needed investigation — and that 2020 was an event “we cannot move on” from. But after the primary, the TV doctor said he wouldn’t have joined potential colleagues like Josh Hawley and Ted Cruz in trying to overturn Biden’s election victory. “I would not have objected to it,” Oz told a press conference about former Vice President Pence’s counting of electoral votes in the Senate.

Behind the scenes, there have been times, however, when Oz and his chief advisers have tried to assure some current and former Republican allies that the candidate supports American democracy.

In text messages obtained by Rolling Stone, Larry Weitzner, a top ad-maker for Trump’s presidential runs and a Team Oz consultant, debated Rabbi Shmuley Boteach, a media figure and player in conservative pro-Israel circles, on May 2 on whether or not Dr. Oz is truly a Trumpist election denier. The celebrity rabbi was once a close friend and adviser to Dr. Oz, but has since turned on the MAGA-fied doctor and calls the Senate campaign “grotesque, ”a waste,” and worse.

As Rabbi Boteach was repeatedly lambasting Dr. Oz for being an “election denier,” Weitzner shot back, “I live in [Pennsylvania], I saw firsthand the shit going on. But he is not denying the [2020] election.” When the rabbi replied, “Election fraud is an election denier. You’re playing games,” Weitzner texted, “Massive difference between saying their [sic] was fraud, which most Republican officials and voters believe as well as real evidence, [versus] saying the election was stolen or denying Biden won.”

According to these texts, Weitzner also messaged Rabbi Boteach: “[Oz] doesn’t deny the results of the election. Says we need to learn from it and make changes in how the elections are run. In [Pennsylvania] it was totally screwed up with unmanned drop boxes and paper ballots sent to millions of voters many of who had not voted in years and did not ask for them.”

“Not an election denier,” Weitzner insisted to Rabbi Boteach, sticking up for Oz, who has on-and-off publicly embraced Trump’s fabricated narrative of a “rigged” election.

In early September, the congressional committee investigating the Jan. 6 Capitol riot released a Dec. 8, 2020, email they said was sent by Trump ally and former House speaker Newt Gingrich, to Weitzner and senior Trump lieutenants. The email reads: “The goal is to arouse the country’s anger through new verifiable information the American people have never seen before,” and, “If we inform the American people in a way they find convincing and it arouses their anger, they will then bring pressure on legislators and governors.”

How Oz feels about democracy may prove critically important to its ongoing existence in the United States. His race with Fetterman is one of a handful that will decide control of the Senate in 2022. And if Oz wins, he’ll be a prominent Republican official in a state that Trump is already preparing as ground-zero for election-fraud claims in 2024. Rolling Stone reported last week that Trump and his allies plan to push fraud claims in Philadelphia during, and after, the midterms — and that Trump views that effort, in the words of one knowledgeable source, as a “dress rehearsal for Trump 2024.”

But Oz’s difficulty keeping a consistent position on the 2020 election illustrates the dilemma many candidates now face in reconciling their own rhetoric with Trump’s conspiracy theories. The former president’s lies have shaped state parties, which normally serve as a bench for campaign staff. And the ex-president and his allies have not hesitated to punish candidates who don’t share their view: When MAGA favorite Mo Brooks said his party needed to put 2020 “behind you,” Trump helped doom Brooks’ 2022 U.S. Senate primary run in Alabama — saying the candidate had turned “woke” and rescinding his endorsement.

In Pennsylvania, Republicans who endorse Trump’s election lies are ascendant. The state GOP has 10 election deniers running for office at the state and federal level, according to a count by FiveThirtyEight, and Republicans in the state legislature are still pursuing a conspiracy-theory-fueled investigation into the 2020 election nearly two years later. Chief among them is Mastriano, who organized bus trips to the Jan. 6 “Stop the Steal” rally and faces a subpoena from the Jan. 6 committee for his efforts to overturn the election.

Almost immediately after Trump stepped out of office early last year, the ex-president turned Republican acceptance and promotion of his election lies into a litmus test for, among other factors, earning his coveted endorsement ahead of the critical 2022 midterm races. Earlier this year, the former president became increasingly convinced that Oz would, as Rolling Stone reported, “fucking lose” in Pennsylvania, joining a chorus of prominent Republicans who were loudly sounding the alarm. One source of Trump’s annoyance with Dr. Oz at the time was that the ex-president did not feel his Senate candidate — unlike Mastriano — was being aggressive enough at defending Trump’s election propaganda.

However, as Oz has closed the public-polling gap with Fetterman in recent months, Trump and the GOP are now much more bullish on Oz’s chances. And the party, and its leader, have already started planning for possible 2022 election challenges and legal battles following Election Night in November, especially if there are tight races — with Pennsylvania cities and Democratic bastions like Philadelphia squarely in their sights.

Regardless of whether a court fight ultimately materializes, the Democratic Party is gearing up for war. The Daily Beast reported on Friday that this week, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee emailed the party’s candidates in the Keystone State to “identify a local attorney for your campaign,” to be at the ready on, as well as after, this year’s Election Day. According to FEC filings, the Fetterman 2022 campaign has retained the services of Marc Elias’ law firm. In the chaotic aftermath of the 2020 presidential contest, Elias was the prominent attorney for Team Biden and national Democrats in combating the multistate Republican legal effort to keep Trump in power.

“As we saw in 2020, and will certainly see in 2022, Republicans’ attack on voting will not stop after Election Day,” Elias predicted this month. “They will use every tool available to contest elections and avoid concessions.”

READ MORE Glacier National Park in Montana. (photo: Jeff Miller/Getty Images)

Glacier National Park in Montana. (photo: Jeff Miller/Getty Images)

Glacier National Park in Montana is a fisherman’s paradise. Hundreds of snow-fed lakes pepper the park, home to over 20 species of fish, including six kinds of trout. And, because it’s federal land, no license is required to cast a reel. But in a warming world, the National Park Service (NPS) is hoping to transform one of Glacier National Park’s coldest lakes into a refuge for a species of trout.

But it’s not as simple as translocating this species into the park. In order to create an environment for these fish, NPS first needs to get rid of the non-native trout that currently inhabit that lake.

The plan proposed by the park, which, if approved, would begin September 2023, recommends using a long-used pesticide and rat poison called rotenone. Despite being a naturally derived compound, it has been banned for use on rodents since 2005. While it is still a widely used fish toxin, or piscicide, as well as a widely used pesticide, researchers have unearthed strong epidemiological links with Parkinson’s Disease.

Like many lakes in the Western United States, Gunsight Lake was historically fishless. However, in the early 1900s, this picturesque body of water nestled between the towering peaks of Fusillade, Jackson, and Gunsight Mountains was artificially stocked with rainbow trout to improve recreational fishing opportunities. Since then, according to the scoping document, or the proposed plan, released by the NPS, the rainbow trout established a self-sustaining population in the lake. Through hybridization, i.e. the mixing of gene pools, they threaten the existence of native cutthroat trout within the same Saint Mary’s waterways (a listed species of concern for the state of Montana).

In order to help establish their population, the park is proposing to apply the fish toxicant via an inflatable boat and backpack sprayers with helicopters transporting materials. While rotenone naturally breaks down due to sunlight, to further limit potential contamination of the Saint Mary River and the rest of the Saint Mary water system, a neutralizing agent, likely potassium permanganate, would be used downstream. Once the non-native fish are eradicated, the park would then translocate (i.e. stock) the river with the cutthroat trout.

This is all to say, the park is proposing using poison to kill one fish in order to save another. And it’s not uncommon, either. In the Grand Canyon, the NPS is currently planning to use similar methods in order to save a native, endangered fish species in the park.

While environmentalists support the action being taken at the Grand Canyon, arguing that the case aims to protect a federally endangered species whose only habitat is that river, they insist that in the case of Glacier National Park, perhaps an alternative to poison should be considered.

Margaret Townsend, an attorney for the Center for Biological Diversity, a non-profit focused on conservation, urged the park to consider alternatives, something their scoping document did not discuss. “Because poison is indiscriminate, because it’d just kill everything in the lake, we’d prefer other options be explored in a situation like this one,” she said.

Townsend suggested a few alternatives: she cited the idea of electrofishing, a method which uses electricity in order to more effectively harvest undesirable fish. Another option to be explored, according to Townsend, is hosting a fishing derby, a contest that encourages anglers to catch as many fish as possible. She also suggested a hybrid model, perhaps one which utilizes both electrofishing, then tracking to ensure all of the fish are captured.

Chris Downs, a fisheries biologist for the park, argued that these methods take too long: “We’ve tried many of these other methods in the past and they haven’t been extremely effective,” he said. “They can take years and years and years, rotenone takes a week.”

However, Townsend argues that perhaps the poison should only be used in emergency situations. The main difference with the case in the Grand Canyon, is that the native species is listed as endangered and that lake is their only habitat in the world. “For the Grand Canyon, time is of the essence,” Townsend argued, “But for Glacier National Park, I’m not so sure.”

Beyond the issue of whether or not to poison these fish in order to protect another, Dana Johnson, a Staff Attorney for Wilderness Watch, a non-profit organization dedicated to protecting wilderness areas, argues that the way in which the park is planning to deploy the poison is a problem.

“The proposals run head-on into the Wilderness Act's "untrammeled" mandate, which says natural processes and conditions are supposed to dictate what type and how many species persist rather than intentional human control and manipulation,” Johnson said.

In short, Johnson argues that because most of Glacier National Park is recommended wilderness—it should be treated as such—and human interference should be limited.

It’s an ideology Townsend shares, and in her opinion, points to larger issues around conservation that need to be addressed. In her opinion, while the park is attempting to create a cold-water refuge for this species, it is a “Band-Aid solution,” one that does not address that waters are warming all over the West, and the world.

“Killing one species to save another is something we have to come to terms with,” Townsend said. “We’ve created these problems and then are trying to resolve them with a very quick fix, but there is so much more we could do to save cold water habitat.”

On the other hand, one could see this as the park attempting to take action and do their part in protecting wilderness in the face of a warming world. “We can’t control the changing climate,” Downs said, “we’re just trying to buy these fish more time to adapt.”

READ MORE Voting. (photo: Vice)

Voting. (photo: Vice)

Vigilantes, saboteurs, suppression... It’s already happening now, 12 days before Election Day, in plain sight.

All over the country, the rotten seeds of Donald Trump’s yearslong campaign of stolen-election lies are fruiting. In Arizona’s Maricopa County, masked and armed vigilante poll watchers loom over ballot drop boxes and in some cases follow and intimidate voters. They’re egged on by propaganda films like 2000 Mules and by Trump himself. Meanwhile, anonymous conspiracists target election officials and candidates with threats, putting law enforcement on alert for real-world versions of the violence that’s already all over the internet.

In Georgia, GOP officials refused to bend to Trump’s efforts to steal 2020, and have even provided key evidence for the criminal investigation in Fulton County. But they also teamed up with the state Legislature to pass some of the country’s most suppressive new voting laws, all in the name of “election integrity.” Now early-voting Georgians, many of them Black, are facing repeated, unlimited challenges to their status as they try to cast ballots. Emboldened Republicans are mounting the challenges by the thousands, and it’s all legal.

In Pennsylvania, where counting rules make it likely that close races won’t be called on election night, Trump himself is reportedly gearing up to rush in, cry fraud, and claim victory for his chosen candidates in an election where he’s not on the ballot. Trump, of course, is pursuing the strategy for himself, viewing the challenges as a “dress rehearsal for 2024,” according to one source in the piece.

But the most imminent fiasco could be Nevada, where election officials have been driven from office by election saboteurs, armed in some cases with antisemitic conspiracies. Four counties have spurned ballot tabulating machines for hand-counting, which experts warn is guaranteed to introduce more errors. Lawsuits are underway in Nye County, where watchdogs warn that “a historic disaster is brewing.”

And not to be outdone, Steven Bannon, soon due in prison for covering up his role in the attempted coup, this week appeared on InfoWars and encouraged the audience to volunteer as poll watchers.

That’s the same InfoWars that Alex Jones used to earn himself a recent billion-dollar judgment for the slander that the Sandy Hook massacre was fake and its murdered children were actors. Bannon’s appearance proves the obvious: that sops toward “election integrity” have nothing to do with integrity and everything to do with chaos.

Trump’s ability to spawn, spread, and perpetuate self-serving election mayhem derives from the fact that he’s faced no accountability for any of the other times he’s done it. In 2016, Russia interfered in the presidential election, and the Trump campaign enthusiastically accepted the help. After that, Trump acted to obstruct the investigation into that interference, probably criminally.

In 2020… well… you know.

Criminal investigations are underway in Georgia and D.C. looking at the 2020 coup attempt and Trump’s role at the center of it. I don’t know if those probes, or the one of top-secret documents at Mar-a-Lago, will result in any consequences for Trump or his allies. The consequences for the rest of us are already here.

Militias’ behavior

Last week we brought you some of VICE’s great new reporting on how political extremism is reinfecting America. This week, three more members of a right-wing militia in Michigan were convicted of supporting the plot to kidnap Gov. Gretchen Whitmer as revenge for her COVID policies. It’s all part of the Wolverine Watchmen conspiracy, which has already featured two federal convictions, a couple of guilty pleas, and some acquittals.

In this case, a jury in Jackson County found Paul Bellar, Joseph Morrison, and Pete Musico guilty of aiding terrorism and weapons charges that could get them 20 years at sentencing. Just last week, Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel said on the Breaking the Vote show that threats against her are so bad in her reelection campaign that she fears she won’t be able to stay in the state if she loses on Nov. 8.

T.W.I.S.™ Notes

- Crimin’ and stealin’

Jury selection got underway in the New York criminal trial where the Trump Organization is charged with multiple felonies, including tax fraud and grand larceny. Longtime CFO Allen Weisselberg already pleaded guilty to a fraud scheme where he and Trump Org entities hid nearly $1.8 million in income from the IRS. He refused to cooperate with prosecutors, but he has to testify truthfully in this trial if he wants the relatively breezy five-month jail sentence in his plea agreement. Donald Trump himself isn’t accused in the case and is unlikely to participate, though his company is at risk for $1.6 million in fines.

Remember, this is all separate from the civil case in which New York’s attorney general accuses Trump and his adult kids of manipulating real estate values to defraud taxpayers and banks. That’s the one where Trump sat for a deposition and claimed Fifth Amendment protection 440 times.

- Gimme clearance, Clarence

Who will save Sen. Lindsey “Count me out” Graham from having to appear before the Fulton County, Georgia, grand jury investigating the plot to overturn the 2020 election? Yep, it’s the only Supreme Court justice who voted to allow Donald Trump to hide evidence from the January 6 committee. Justice Clarence Thomas temporarily blocked an appeals court ruling this week that ordered Graham to honor a subpoena from the grand jury.

Graham sued to avoid testifying, claiming that the Constitution’s “speech and debate” clause immunizes him from having to appear. Last week, judges on the 11th Circuit said that while legit senatorial activities are protected, Graham still has to answer questions about not-senator things like coordinating with the Trump campaign to overturn Georgia’s election results, or “efforts to ‘cajole’ or ‘exhort’ Georgia election officials.” (Graham called Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger to ask about tossing out mail-in ballots from counties favoring Joe Biden.)

Thomas put a hold on the 11th Circuit, but only until the rest of the court has a chance to weigh in. So far, it has shown little interest in backing up Trump when it comes to stolen election claims.

- Mark-ed questioning

Former White House chief of staff Mark Meadows also very much does not want to testify in front of the Fulton County grand jury. But on Wednesday a South Carolina judge ordered him to answer his subpoena. But if Graham can take it all the way to SCOTUS, why not Meadows? Expect appeals.

BTW, the former prosecutors VICE News’ Greg Walters has been talking to in Fulton County think Trump is about to get charged.

- Awk-Ward

And will SCOTUS save Arizona GOP chair Kelli Ward from having to produce her phone records to the January 6 committee? She hopes so! Justice Elena Kagan also put a temporary stay on Ward’s subpoena and asked the committee to weigh in by today. It looks like Arizona Republicans ran one of the fake elector schemes at the center of the 2020 coup plot. Ward appeared in front of the committee, where she took the Fifth.

- The audacity of Hope

Trump adviser-turned-Fox-News-personality-turned-Trump-adviser Hope Hicks sat for an under-oath, transcribed deposition with the January 6 committee this week. Several post-coup books put Hicks in the large camp of advisers who repeatedly told Trump he lost the 2020 election.

- A sensible pair of Pats

DOJ prosecutors are asking a judge to compel former White House counsels Pat Cipollone and Patrick Philbin to talk about conversations with then-President Trump in front of a federal grand jury investigating the coup attempt. The Pats have so far refused to answer some questions that could be off-limits thanks to executive or attorney-client privilege. But prosecutors already busted those claims and got two of former Veep Mike Pence’s counsels to testify. Here’s how hard Trump was trying to stop that from happening.

The Mule-er retort

Clapping back for democracy! A Georgia man accused of illegal ballot harvesting in the propaganda film 2000 Mules is suing Dinesh D’Souza and a whole bunch of his election conspiracy friends in federal court. Mark Andrews’ lawsuit against D’Souza, True the Vote, and others claims their election conspiracies caused “immense harm” for election workers, ordinary citizens wrongly accused, and the democracy itself.

The suit states D’Souza showed Andrews on screen dropping ballots at a drop box in 2020 while intoning, “What you are seeing is crime. These are fraudulent votes.”

“In fact,” the suit continues, “the video of Mr. Andrews shows him legally dropping off ballots for himself and his family, a voting method expressly authorized by Georgia law.”

"He was your prey. He was your trophy." - U.S. District Judge Amy Berman, sentencing Capitol rioter Albuquerque Head to seven and a half years in prison for assaulting D.C. Police Officer Michael Fanone during the insurrection.

Leaving in droves — Regular BtV readers know well the story of harassment, intimidation, and downright inconvenience driving election workers away from the critical, unsung jobs of democracy. This piece does a great job of laying out the causes and the numbers. Election workers are fleeing service almost everywhere: In Utah, turnover between 2020 and 2022 is up 55 percentage points over 2016-2020; in the swing state of Georgia, it’s up 36 points.

Here’s one horrible scene from Nevada that caught my eye: “In another Trump-dominated county, Sandra Merlino retired in August in the middle of her term as county clerk in Nye County, after her commissioners gave in to the demands of an election-denying activist...

‘It was horrible, because I’ve been doing elections since January of 2000,’ said Merlino, who was immediately replaced by a clerk who has falsely said Trump won the election. The activist who pushed for the hand count, Jim Marchant, is now the Republican nominee for secretary of state and leading in the polls.”

Six years for registering — An activist and former mayoral candidate in Memphis is suing the state of Tennessee for a six-year voter fraud sentence that she says caused her significant emotional anguish before it was invalidated. Pamela Moses served close to three months in jail before a new trial was ordered on her conviction of illegally registering to vote. Moses was ineligible to vote because of previous felony convictions. She maintained she thought her right to vote had been restored, though activists say the judge who gave her six years was trying to intimidate Black voters.

“Twenty-nine Americans” — Ninety Florida residents have been charged in the Jan. 6 insurrection, more than from any other state. “If you live in Tampa Bay, an alleged insurrectionist likely lives somewhere nearby.”

tick tick tick tick tick — After the barrage of lies and conspiracies from Trumpists, Dominion Voting Systems now has eight defamation lawsuits totaling $10 billion in the field against Fox News, Rudy Giuliani, Mike Lindell, Sidney Powell, and a bunch of others (congrats to their lawyers on their no-interest-rate homes.) If you missed 60 Minutes’ interview with Dominion CEO John Poulos, catch it here.

President Biden and Chinese leader Xi Jinping visited a California school together in 2012 when they were both vice presidents. Biden's administration is now considering how to police TikTok, one of China's most prominent online hits. (photo: Damian Dovarganes/AP)

President Biden and Chinese leader Xi Jinping visited a California school together in 2012 when they were both vice presidents. Biden's administration is now considering how to police TikTok, one of China's most prominent online hits. (photo: Damian Dovarganes/AP)

The wildly popular app’s link to China has sparked fears over propaganda and privacy. It’s also exposed America’s failure to safeguard the web.

President Donald Trump’s top advisers had staged a raucous brawl in the Oval Office, shouting at each other over whether the app’s U.S. presence should be carved up and sold or banned for life.

Trump responded by ordering the app banished from the country within 45 days, signing its death warrant aboard Air Force One. Then, with his flair for messy drama, he changed his mind, demanding the company instead get sold to a U.S. buyer — provided, he said, that the United States got rewarded for its efforts by pocketing a “very large” cut of the sale’s proceeds.

The leaders of TikTok, owned by the Beijing-based tech giant ByteDance, had resigned themselves to selling to some stalwart of American capitalism, like Microsoft or Walmart, if it meant the app could survive, according to people familiar with the inner workings of the company who spoke on the condition of anonymity to describe sensitive matters.

But the Chinese government had the final say. Feeling protective of their powerful asset and antagonized by Trump, officials moved quickly to squash the takeover, adding the algorithms that drive TikTok’s growth to their list of banned exports and warning ByteDance through a state-owned news organ to “strongly and carefully” reconsider any deal.

The Chinese government “would rather have the company die than have it sold,” one of the people said. “They are not going to let the United States have one of their crown jewels — their algorithms. They would rather destroy it.”

The fight over TikTok has become one of the biggest standoffs of the modern internet: two global superpowers deadlocked over a multibillion-dollar powerhouse that could define culture and entertainment for a generation. Yet the battle has often played out like a farce, loaded with an almost comical level of contortions and contradictions — even as China’s power over the company has grown.

No piece of software has ever stirred so much angst in Washington. Once dismissed as a trivial teen craze, TikTok has been pummeled as a child-spying, data-crazy, “sophisticated surveillance tool” — what Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Tex.) once called “a Trojan horse the Chinese Communist Party can use to influence what Americans, see, hear and ultimately think.”

But if TikTok truly is the ultimate propaganda weapon, Washington has rarely treated it like one. Few of the expressions of federal dread — the dozens of congressional letters and agency bans and statements calling for someone to investigate something — have translated into actual action.

Trump ultimately decided against a TikTok ban before the 2020 election after being shown internal polls suggesting the move would hurt his standing with young people and suburban moms, a former Trump aide told The Post. TikTok is now bigger than ever: Since Trump left the White House, the app has been downloaded in the United States more than 100 million times.

For the Biden administration, TikTok has become a giant test of how to regulate a formidable and wildly popular cultural phenomenon while navigating the contours of U.S.-China relations and grappling with the new reality of an internet that American firms no longer dominate.

Federal officials have spent months negotiating a national security agreement that could reshape how the company operates in the U.S. But all of it could get blown up in an instant if Republicans retake Congress next month — or if Chinese government officials in Beijing balk at a deal.

The U.S. has failed to pass major social media regulations governing domestically run platforms that are committed, at least nominally, to American attitudes about freedom of speech. Now, the industry’s biggest hit in years comes from an authoritarian country with a radically different ideology on civil liberties and media control — and Washington is once again stalled on how to proceed.

The Biden administration, which vowed to evaluate TikTok’s risks in a “decisive and effective fashion,” launched a security review in June 2021 that has yet to publish its results. The Commerce Department’s months-old pledge to develop a new strategy for apps that foreign adversaries might exploit also still has nothing to show.

And a three-year, nine-agency investigation by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), a secretive government group with the power to veto international business deals, has taken so long — and involved so many lawyers — that even some TikTok employees have complained it feels like the government is in no hurry to get anything done.

The two sides have agreed on some initial terms — oversight from U.S. government specialists, new data-security rules — but the deal is still not close to a clear outcome, according to two officials who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the matter’s sensitivity.

The Biden administration is considering a broader data-security executive order that could limit how Americans’ data is shared with China, the officials said, but it will probably not publish until late this year or early next year.

TikTok spokeswoman Brooke Oberwetter said the company is “on a path to fully satisfy all reasonable U.S. national security concerns. … Our operations in the U.S. have been scrutinized from every angle, and we have willingly engaged in that process.”

A CFIUS spokesman declined to comment, saying only that the group is “taking all necessary actions … to safeguard U.S. national security.” The White House’s National Security Council also declined to comment.

The concerns about TikTok have been amplified by lingering questions in Washington about how the app is run. TikTok’s U.S. executives say they operate independently of ByteDance executives in Beijing, are not influenced by the Chinese government, have never been pressed for data by Chinese authorities and would refuse to provide it if they were asked.

TikTok officials insist decisions about data security, business strategy and content rules are handled by company executives in Dublin, Mountain View, Calif., and Singapore, where the app’s chief executive, Shou Zi Chew, lives. TikTok’s California-based chief operating officer, Vanessa Pappas, told a Senate committee last month that ByteDance is a “distributed company,” without an official headquarters in China or anywhere else.

But current and former TikTok employees say managers in Beijing, where many of the company’s executives and employees still work, have assumed an increasingly active role in the U.S. team’s operations, leading them to question what leverage they would have to resist unwanted interference. Chew, the Singapore-based CEO, also reports to ByteDance’s chief and board.

Although the U.S. offices have some independence, China remains the company’s central hub for pretty much everything, according to the current and former employees, most of whom spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of endangering their careers. Beijing managers sign off on major decisions involving U.S. operations, including from the teams responsible for protecting Americans’ data and deciding which videos should be removed. They lead TikTok’s design and engineering teams and oversee the software that U.S. employees use to chat with colleagues and manage their work. They’re even the final decision-makers on human resources matters, such as whether an American employee can work remotely.

There’s been “a full-blown recognition” inside the company that China’s efforts to control its tech giants extend even to TikTok, a service that can’t be seen inside China, said one person familiar with TikTok’s internal operations. Government officials “want to put their finger on the scale” of the nation’s tech industry, this person said.

Liu Pengyu, a spokesman for the Chinese Embassy in Washington, said in a statement that TikTok follows “international rules and abides by U.S. laws and regulations.”

The U.S., Liu said, has “frequently used state power to unreasonably suppress” foreign-owned companies “under the pretext of national security” in what he called “a blatant act of bullying.”

“We urge the U.S. side to … refrain from politicizing economic issues,” he said, “and provide a fair, just and nondiscriminatory environment for the normal operation and investment of companies from all countries.”

In Washington, TikTok has fueled an intense debate over how much operational leeway any Chinese company should get. Some in the Biden administration have backed a system of privacy commitments and regulatory checks, worried that an outright ban, based on vague national security concerns, would reek of nationalist protectionism — the same sin the U.S. has accused China of all along.

No one wants to repeat Trump’s failure; his orders collapsed in court after federal judges ruled he had shown little “substantial” evidence of TikTok’s threat. But some worry that nuanced technical measures won’t be enough to resolve the fact that one of America’s most dominant online megaphones is in the hands of its biggest ideological rival.

“It’s one of the very few areas where Donald Trump may have been right,” Sen. Mark R. Warner (D-Va.), head of the Senate Intelligence Committee, said in an interview.

Lacking coherent guidance, the official U.S. relationship with TikTok has been in a state of constant disorder. American soldiers banned from installing the app on military devices still use it all the time on personal phones. The White House said it was scrutinizing the app for national security risks, then gave special briefings to its biggest stars — as was first reported by The Washington Post, whose namesake TikTok account has 1.5 million followers.

The House of Representatives’ chief administrator warned House staff in August not to use the “high-risk” app. But the Democrats, who run the House, already employ a full-time TikTok content strategist to help run their 130,000-follower account. Stacey Abrams, Val Demings, Jon Ossoff and other rising Democratic stars are all regulars; so are both sides of the Pennsylvania Senate race, John Fetterman and Mehmet Oz. President Biden himself appeared in a TikTok influencer’s video on the same day last month that Pappas, the company executive, was getting grilled on Capitol Hill. (A DNC spokesperson said its TikTok videos are made on dedicated devices, isolated from the committee’s other business, to mitigate potential privacy risks.)

Even politicians who don’t have a TikTok presence acknowledge that many of their friends and family are users. “It seems like every day someone’s sending me a TikTok,” said Rep. James Comer (Ky.), the top Republican on the House Oversight Committee. He doesn’t have an account himself and said, “I don’t think it’s out of the question to suspect China may be up to no good.”

The federal government, however, has yet to provide actual evidence of harm or conspiracy for an app many Americans know and love. And American companies have shown plenty of problems of their own. Facebook paid a record $5 billion settlement to the Federal Trade Commission for violations of user privacy, while researchers have shown that political misinformation on the platform helped fuel the violence of the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection. Twitter recently was accused by its former security chief of major security failures and of harboring foreign-government spies.

When lawmakers have reached agreement over TikTok’s risks, they’ve focused on issues that technical experts view as irrelevant, like where Americans’ data is stored. TikTok argued for years that the risk to Americans’ data was low because the information was stored on servers in Virginia and Singapore. Then, as the negotiations with CFIUS continued, the company announced an initiative known as Project Texas that would move all U.S. user data to servers in Texas run by the tech giant Oracle.

But that concern and the solution has always struck independent technical experts as off point. It doesn’t matter where a server is plugged in, they argue, if someone still has access half a world away. TikTok executives say Chinese employees still will be able to access the data, rendering the solution effectively moot.

“These measures were completely undermined as soon as they were announced,” said Adam Segal, a cybersecurity expert at the Council on Foreign Relations, referring to Project Texas. More to the point perhaps, he said, “the data is not particularly high quality to begin with.”

Some lawmakers have voiced support for Oracle becoming an independent auditor of TikTok’s algorithms. But the company is not a public watchdog; it’s TikTok’s business partner — and was almost a part owner, had Trump’s sell-off push not failed. Co-founded by Trump ally Larry Ellison, Oracle has no social media experience and has shared no details of how its audits would work.

As a protector of Americans’ data, it’s also an unusual choice: Oracle runs massive businesses, known as data brokers, that sell Americans’ personal records by the billions — a practice that has triggered lawsuits over the company’s “global surveillance machine.” Oracle declined to comment.

The intense focus on TikTok, some technical experts argue, has overshadowed more problematic ways Americans’ data gets gathered and exploited in a country — the United States — without any basic data-privacy laws. And banning TikTok would do nothing to prevent buyers in China or around the world from collecting more sensitive information on Americans from unregulated companies, including data brokers, whenever they please.

“TikTok is this totally different animal that no one in the U.S. government really understands, and so there’s just been months of hand-wringing,” said Paul Triolo, senior vice president for China at the business strategy firm Albright Stonebridge Group.

“Is the worry that teens will do such idiotic videos when they’re 15 that they’ll be blackmailed by the Chinese government later in life? Or that the AI algorithm will be abused to serve up a bunch of anti-Joe Biden videos?” Triolo said. “These things aren’t impossible, but there’s no evidence that any of this is happening. And there are real consequences to taking action on the basis of potential future risk that you can’t quantify very well.”

TikTok has for years coached employees to downplay its “China association.” Pappas, a former YouTube executive who had worked with some of the video giant’s biggest creators, told The Post in 2019 that TikTok’s U.S. operation had “a large degree of autonomy” from Beijing and worked best “without executives 10,000 miles away involving themselves in their decisions.”

To underscore that independence, TikTok has said it limits which employees in China can see data from Americans’ profiles. But TikTok’s own employees have questioned those limits. In recordings of internal meetings first reported by BuzzFeed in June, and which a former TikTok employee provided to The Post, company employees in the U.S. can be heard saying some engineers in Beijing had “access to everything.”

TikTok executives disputed that interpretation, saying the recordings proved the company had been looking for problem spots in a giant organization and figuring out ways to firm them up. And many of the meetings did discuss new safeguards, with one employee in the recordings calling for all Chinese data-access privileges to be questioned with “additional … scrutiny.”

In any case, TikTok has now made it clear: The access by staff in China isn’t going away. U.S. executives have said that teams in China will retain access to Americans’ data for “engineering functions” and other “daily duties.” In a letter to nine Republican senators in June, Chew, TikTok’s CEO, said employees in China would continue working on the app’s most critical elements, including the “For You” algorithm that shapes what each user sees.

The revelations kicked up a fury among congressional Republicans, who accused the company of placing the “safety and privacy of millions of U.S. citizens in jeopardy.”

TikTok’s defenders argue that much of the data-privacy outrage is overwrought. The app collects people’s ages, locations, phone numbers, facial photos, voice recordings and search histories, its privacy policy shows — but that kind of data is gathered by most social networks, and America’s biggest ones collect even more.

Facebook has spent nearly two decades compiling people’s photos, work histories and relationship statuses for ad-targeting databases. Snapchat, criticized for its security promises, has operated under an FTC settlement order since 2014. And a Twitter whistleblower recently alleged in a federal complaint that Chinese entities could use that platform to punish users who had jumped the country’s firewall.

Jeremy Fleming, the head of the British cyberintelligence agency, said this month that he was unconcerned by children’s use of the app as long as they were attentive about what data they were sharing. “Make those videos, use TikTok, but just think before you do,” he said.

Some privacy advocates question why members of Congress critical of TikTok haven’t directed the same degree of outrage at data brokers, whose industry sells bulk details on Americans’ health and finances, including to foreign buyers. No one has accused TikTok of breaking federal data-privacy laws, because the U.S. doesn’t have any; a proposal for baseline privacy protections that would apply to all companies, not just Chinese ones, remains indefinitely stalled in Congress.

TikTok is more aggressive about collecting data than its competitors in some notable ways, however. The app will continuously ask for a user’s full contact list, even after they say no, the U.S.-Australia research team Internet 2.0 found in July. Another researcher, Felix Krause, discovered code that could record everything a user types into the app’s internal web browser, including passwords; the company said the code was never used to record keystrokes.

The gathering of such data, and its open flow to Chinese engineers, has alarmed some former employees. A former TikTok employee and a former security contractor told The Post they had spoken with the FBI separately about their concerns. The FBI declined to comment.

TikTok executives have argued that Americans’ information is not subject to Chinese laws, which can force tech companies to hand over data and cooperate with “national intelligence” work. TikTok, they note, isn’t even available in China, though ByteDance offers a similar service, Douyin, that looks and works just like it.

But Chinese authorities have some experience in back-channeling surveillance requests: Federal prosecutors in 2020 charged a Zoom executive in China with giving people’s data to government officials and disrupting video calls about Tiananmen Square; he remains wanted by the FBI.

Scott Kennedy, a senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a think tank, said TikTok would be limited in its ability to resist a government order. “When it comes to data access from the Chinese state,” he said, “there are always vulnerabilities.”

Since its close call with Trump-induced oblivion, TikTok and ByteDance have spent heavily to make new friends in Washington. They have paid more than $13 million for nearly 50 lobbyists to work the White House, the Pentagon and Capitol Hill, federal disclosures show, with a crew that includes two former U.S. senators and a state chief of both of Trump’s presidential campaigns.

Much of their outreach has focused on the political party whose members seem to despise them: TikTok has donated to the Republican Attorneys General Association and was listed among the attendees of the political influence group’s donor retreat this summer in Palm Beach, Fla., down the road from Trump’s Mar-a-Lago Club.

Inside the company’s U.S. offices, the connections to Beijing are hard to miss. Several employees said they had been surprised to find themselves called into weekly meetings with their Chinese counterparts to discuss intimate details of how the U.S. app runs. “As I get more senior at the company, I realize China has more control,” said an employee who works in U.S. content moderation and spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal matters.

TikTok last month banned all political-campaign fundraising and began requiring all candidates and political parties to go through a “mandatory verification” process, saying the move would help reduce “harmful misinformation.” The change expanded TikTok’s long-running ban on ads promoting any politician, partisan cause or “issue of public importance,” which its executives have argued is designed to protect the app as a place for “joyful” content.

A person familiar with the company’s corporate decision-making said TikTok’s approach to political content has been driven by its leaders’ eagerness to avoid political squabbles at all costs. The fear of Washington controversy, the person said, has also driven the company’s attitudes around which videos should be permitted or suppressed. TikTok officials deny that fear of political blowback has driven policy.

TikTok’s parent company faces similar strains in China. Authorities there in recent months have intensified a national crackdown on thousands of tech companies, including passing intricate new rules detailing how algorithms should run and what topics should be banned from discussion. Regulators have issued rules demanding that recommendation algorithms spread only “positive energy” and a creator “Code of Conduct” that bans content that promotes “immoderate” lifestyles or seeks to create “hot issues in public opinion.”

TikTok officials acknowledge that the app uses built-in measures to demote videos the company doesn’t want seen, marking videos so that they are visible to the creator and their followers but never shown on people’s “For You” feeds — an algorithmic kiss of death.

In TikTok’s early years, leaked guidelines showed that moderators were told to suppress videos about the Tiananmen Square massacre and other fraught topics, as well as videos showing people with disabilities or “ugly facial looks.”

TikTok executives have said that those guidelines were a “blunt instrument” to minimize conflict and have since been replaced. But questionable suspensions remain routine.

When a teenager’s account was suspended in 2019 after she discussed China’s detention of Uyghur Muslims, TikTok blamed a “human moderation error.” When phrases such as “I am a Black man” were flagged as inappropriate, TikTok blamed a “flaw” in its hate-speech detection software. When a famous Tiananmen Square clip was made invisible, the company blamed a misapplied ban on “military information.” And when, in February, its automatic-subtitle feature blotted out phrases such as “reeducation camps,” which China runs in its western province of Xinjiang, the company blamed an “outdated” system built to block profanity.

TikTok’s defenders say these were inadvertent mistakes, not attempts at mass censorship; Facebook and Instagram, they note, have been criticized for their handling of race and censorship, too. Citizen Lab, the University of Toronto research group, found only “inconclusive” evidence last year in a test of whether TikTok was censoring politically sensitive posts: Some posts vanished, while others stayed up, with no clear pattern of blame. And any TikTok viewer in the U.S. can now find hours of videos that discuss topics that would be banned on China’s internet, including about its mass detention camps and Tiananmen Square.

But the company’s internal debate over tolerable speech remains very much alive. A TikTok employee suggested censoring a Financial Times report in June about a ByteDance executive who had spoken dismissively of maternity leave, the newspaper found. TikTok said the idea was never considered.

TikTok said, in its most recent “transparency report,” that government authorities had asked it to remove or restrict more than 400 videos or accounts last year — but that none of those requests had come from China, one of the most censorious countries in the world.

Chinese companies, however, must routinely agree to Chinese government involvement, and ByteDance is no exception. In 2018, ByteDance’s founder responded to government punishment by pledging to help boost the Communist Party’s core values. Last year, the Chinese government took over one of the three board seats in a ByteDance subsidiary critical to its biggest apps. And in August, Chinese regulators said ByteDance had submitted the core “behavioral data” algorithm used in Douyin for registration and review.

If the U.S. government wanted to come down hard on TikTok, the punishment could resemble that meted out to another Chinese tech star, Huawei. The company was one of the world’s biggest sellers of telecommunications gear when U.S. officials blacklisted it as a national security threat; several sanctions, export restrictions and federal investigations later, the company’s global market share and revenue have dwindled, and its U.S. presence has effectively collapsed. (The company has said the claims are baseless.)

Some former U.S. employees of TikTok, however, said that much of the Washington fearmongering around the app appears overly dramatic. “Never once did I think, ‘Oh, no, the Chinese are going to come and set all our policies,’ ” one former TikTok manager said.

Still, some argue that the company’s internal secrecy and murky chain of command limit the U.S. team’s ability to know who in Beijing is really in control. One former employee, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation, said: “There was always this hierarchical culture from China. They had made these decisions, and we should just follow.” (TikTok officials said the company discourages corporate hierarchies.)

TikTok has previously promised to dispel all doubts about its independence, pledging in early 2020 to open physical “Transparency Centers” where experts could observe the company’s real-time moderation decisions and examine its algorithms’ code. But the company indefinitely shelved the plan soon after, citing the pandemic, and has instead offered guided virtual tours to journalists and political staff.

In August, Axios reported that Oracle officials had begun auditing TikTok’s algorithm and were using “regular vetting and validation” to ensure “the models have not been manipulated in any way.” But two people familiar with the matter, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss it, said the audits have not been started or closely planned.

TikTok officials said they chose Oracle based on its technical prowess and experience with government contracts. But both companies declined to answer questions seeking further details for how any of this oversight would work, including how much Oracle would be paid, what its auditors will do or how they’ll respond if they see anything wrong.

Oracle, which is publicly traded, has filed nothing with the Securities and Exchange Commission detailing the arrangement. For now, the people said, Oracle is functioning solely as TikTok’s server provider, a web-hosting role with no authority to police operations. Oracle has not been involved in TikTok’s negotiations with CFIUS, these people said, and no official national security agreement has outlined what a third-party TikTok auditor would even look for.

Graham Webster, a researcher with the Stanford Cyber Policy Center who studies China, said he wasn’t surprised that TikTok’s mystery and power had fueled people’s suspicions. But so much of the angst around TikTok, he said, has focused on anxieties about the internet that also remain unresolved for American companies: about data harvesting and political manipulation, about the fickle whims of screen-glued teens, about the unaccountable algorithms shaping our lives.

“Rather than confront head-on what’s happening in our own society … we have a multiyear convulsion about one company that happens to come from China,” Webster said. “China has become an avatar for fears that Americans reasonably have about ourselves.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.