Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The two young agitators belonged to Just Stop Oil, an organization dedicated to opposing new fossil-fuel extraction, largely by means of nonviolent civil disobedience. “What is worth more, art or life?” they asked shocked spectators in London’s National Gallery. “Are you more concerned about the protection of a painting or the protection of our planet?”

Many observers rejected the notion that they needed to choose between preserving Earthly life and enjoying van Gogh’s sunflowers. Both in the gallery and online, the reaction to Just Stop Oil’s demonstration was largely negative. But the group is quite used to the public’s ire; it has spent much of this month blockading London’s central roads, much to the consternation of the city’s commuters.

In an interview with The Guardian, Just Stop Oil’s spokesperson Alex De Koning said that the organization did not wish to alienate people but that, ultimately, “We are not trying to make friends here, we are trying to make change, and unfortunately this is the way that change happens.”

De Koning is probably wrong about that. And his organization’s flawed theory of change is all too common within the broader world of climate nonprofits and philanthropies.

To be sure, Just Stop Oil’s work has its admirable aspects. The soup tossers should be commended for their readiness to subordinate personal comfort to the global good. When I was their age, the only cause I risked arrest for was getting stoned in public parks. And the action certainly succeeded in generating headlines about climate change at no actual cost to our collective artistic heritage; the van Gogh painting was behind glass, which caught all of the wayward soup.

And yet, it’s not clear that such headlines will do much to advance decarbonization at this point in time.

Awareness-raising efforts by climate activists may have paid some dividends over the past decade. Although it is difficult to isolate the impact of such activities, growth in philanthropic spending on climate advocacy has coincided with the fortification of an elite consensus behind action. That consensus helped persuade Democrats to prioritize climate change over competing objectives this year: Though Joe Biden’s domestic agenda shed myriad social-welfare policies on its route to enactment, the president’s proposals for green energy and technology made it through largely intact.

Yet there are hard limits on how much theatrical agitation against fossil-fuel extraction can accomplish. And the past year of high and rising energy prices has exposed them.

After the failure of Barack Obama’s “cap and trade” plan in 2009, climate philanthropists concluded that they had put too great a priority on technocratic problem solving and elite suasion, and not enough on seeding a social movement that would force elected officials to take action. But building a broad-based social movement takes more than the disposable income of guilty oil heiresses. And climate is an especially difficult issue to mobilize a mass constituency behind.

Those most immediately harmed by climate change are largely disenfranchised by their positions in space and time. Residents of low-lying island societies too poor to build seawalls know that climate change is no abstract hypothetical. But they also have scant power within the global order. Future generations of Americans, meanwhile, may come to experience the planet’s warming as a threat more dire than rising gasoline prices; current generations simply don’t.

Voters were reluctant to prioritize climate policy over competing concerns even in the era of relatively affordable energy that preceded the COVID pandemic. In a 2018 AP-NORC survey, less than half of working-class respondents said they would be willing to pay $1 more in monthly electric bills for the sake of combating climate change; when that sum was raised to $10 a month, opposition among all voters was overwhelming. That same year in the heavily Democratic state of Washington — amid a “blue wave” election that saw exceptionally high Democratic turnout — a carbon-tax referendum lost by a 56 to 44 percent margin.

This isn’t to say that American voters weren’t at all concerned about the climate. They very much were and are. In the AP’s poll, large majorities of voters favored government action on climate when the tradeoffs of such action were small or unmentioned. And among Democratic voters, climate consistently ranks as a high priority. But electorates have consistently failed to punish elected officials for presiding over rising carbon emissions, even as they quite reliably punish them for presiding over rising fossil-fuel prices.

In the present context of high energy prices, voters show little inclination to force action on climate. In a Gallup survey asking voters to name the most important problem facing the country, only 3 percent said anything to do with the environment, while 17 percent named “the high cost of living” (or variations on that phrase). Earlier this year, Pew asked voters whether they would prefer for the U.S. to “phase out the use of oil, coal and natural gas completely, relying instead on renewable energy sources such as wind and solar power only” or to “use a mix of energy sources including oil, coal and natural gas along with renewable energy sources.” Respondents preferred the latter approach by a 67 to 31 percent margin, a result that evinces concern for balancing the affordability of fossil fuels against the reduction of climate risk.

The public’s tendency to prioritize issues that immediately and clearly impinge on their personal finances over ecological sustainability can’t be attributed solely to conservative propaganda, misinformation, or lack of awareness. For working-class families on tight budgets, an increase in the cost of gas or electricity has immediate consequences for how they live their lives. When the government fails to keep energy cheap, such households are forced to buy less (or lower quality) food, save less for their children’s educations, fall behind on mortgage payments, or shiver in bed at night. By contrast, when the U.S. government fails to expedite emissions reductions, such households experience no direct privation. The consequences of such a policy failure manifest in the future, and in ways difficult even then to perceive: Green policy can’t actually prevent the climate from getting worse, it can only limit the extent of the damage. “A marginally less unfavorable climate a decade from now (so long as India and China emulate our government’s policies)” is never going to be as energizing a rallying cry to the general public as “cheaper energy now.”

To their credit, the Just Stop Oil protesters evinced some awareness of this reality. During their demonstration at the National Gallery, the activists tried to frame their cause as a crusade for more affordable energy, declaring, “The cost-of-living crisis is part-of-the cost of oil crisis. Fuel is unaffordable to millions of cold, hungry families.”

This argument is a bit more coherent than some commentators have allowed. The fossil-energy economy is probably more vulnerable to energy price shocks than a mature green-energy economy would be. But you cannot change the foundation of industrial modernity overnight. Eliminating the global economy’s reliance on fossil fuels for heating and electricity might spare future people from a cost-of-living crisis similar to today’s in Britain. But that is a longterm project. It requires the construction of wind and solar farms and transmission lines, along with the development of better technologies for battery storage and/or, more cost-effective approaches to nuclear and geothermal energy. In other words, it is not a solution that works at the speed of politics, which, in democratic countries, operates on short time horizons.

Meanwhile, we don’t need to speculate about what the short-term impact of realizing Just Stop Oil’s immediate objective – reducing fossil fuel production – would be. Thanks to years of underinvestment in production by fossil fuel companies, the Saudis’ geopolitical machinations, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, we are already running that experiment. And as the protestors’ own rhetoric suggests, the results have been lackluster: As demand for natural gas has exceeded supply, Western Europe has been plunged into a cost of living crisis while low-income developing countries have fallen into blackouts, with millions of their people effectively priced out of the global gas market. This is a disastrous outcome as a matter of social justice; increasing the cost of home heating and electricity in low-income countries kills low-income people. And the consequences of the supply squeeze for the climate haven’t been wholly positive either: Because there is no lever that governments can pull to immediately manifest a mature green economy, scarce natural gas has led many nations to increase their consumption of coal, a more carbon-intensive energy source.

None of this makes decarbonization any less imperative. But it does call into question a theory of change that deems “preventing fossil fuel extraction” the primary goal, and “raising awareness” the primary means. It is possible that restricting fossil fuel supply will expedite green energy development and deployment in the long-term by making alternative energy sources more cost-competitive. But by itself, this is a very inequitable and politically hazardous approach to the challenge. It is tantamount to a carbon tax that generates no revenue, and thus, includes no mechanism for offsetting the costs it imposes on working people.

In sum: You are not going to make the typical voter in Britain or the U.S. more acutely aware of climate change than they are of their household energy bills. And in the absence of other policies, obstructing fossil fuel extraction and infrastructure risks increasing those energy bills, thereby creating political opportunities for the least climate-conscious parties and actors in Western societies. This does not necessarily make new fossil fuel development projects good. But it does make blocking them a poor priority for climate action, especially since securing the permitting reforms necessary for building the green energy economy may, in the U.S. context, require abetting some fossil fuel projects.

In hindsight, the problem with climate philanthropy circa 2009 might have had less to do with its prioritization of technocracy over movement building than with its focus on carbon pricing over industrial policy. It is much harder to manufacture a mass social movement out of philanthropic dollars than it is to subsidize nascent industries with federal ones. And the latter strategy not only helps overcome technological obstacles to decarbonization, but also erodes political barriers: The larger the green sector of the economy grows, the more power it has to pressure the government “from below.” Creating workforces that owe their livelihoods to public investment in green technology, and capitalists who stand to profit off green policy, changes the political economy of climate in a way that astroturf green groups can only pretend to. Of course, green capital cannot be trusted to lobby for a just transition. Nonprofit advocacy groups have a role to play in helping marginalized communities make their voices heard. And organized labor is indispensable for ensuring that green jobs are good jobs. But industrial policies can change the politics of climate at a greater scale than nonprofits can.

Most critically, an approach to decarbonization centered on promoting the development and deployment of green technology reduces the tension between climate action and energy price stability, while activism focused on limiting fossil-fuel extraction does the opposite. This makes the former a more politically sustainable means of weaning the world off fossil fuels. If public policy can make carbon-free energy as cheap and broadly accessible as oil, fossil-fuel assets will be stranded. Contrary to the presumptions of a climate strategy that prioritizes “keeping it in the ground,” fossil-fuel infrastructure does not induce its own demand. When oil prices cratered during the COVID pandemic, refineries were abandoned.

Nevertheless, a large percentage of philanthropic climate funding remains dedicated to awareness raising and anti-fossil fuel extraction activities. Such activism is not wholly without merit. But its popularity with donors does not derive from its present necessity.

There is little reason to believe that Just Stop Oil’s plan of attack is the most equitable and effective way of combating the climate problem. We need more climate-conscious young people to dedicate themselves to tackling the technological barriers to decarbonization and formulating industrial policies that erode the political ones. For the moment, it is less clear that we need more people to obstruct London traffic or throw soup at paintings. Philanthropists should allocate funds accordingly.

READ MORE A view shows the city administration building hit by recent shelling in the course of Ukraine-Russia conflict, in Donetsk, Russian-controlled Ukraine, October 16, 2022. (photo: Alexander Ermochenko/Reuters)

A view shows the city administration building hit by recent shelling in the course of Ukraine-Russia conflict, in Donetsk, Russian-controlled Ukraine, October 16, 2022. (photo: Alexander Ermochenko/Reuters)

In televised remarks to members of his Security Council, Putin boosted the powers of Russia's regional governors and ordered the creation of a special coordinating council under Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin to step up the faltering war effort.

He said the "entire system of state administration", not only the specialised security agencies, must be geared to supporting what Russia calls its "special military operation".

The package of moves, nearly eight months into the war, marked the latest escalation by Putin to counter a series of major defeats at the hands of Ukrainian forces since the start of September. A Kyiv official said it would change nothing.

The published Kremlin decree ordered an "economic mobilisation" in eight regions adjoining Ukraine, including Crimea, which Russia invaded and annexed in 2014.

It placed them in a special regime one step below martial law and allowed for the restriction of people's movements.

Putin conferred additional powers on the leaders of all Russia's 80-plus regions to protect critical facilities, maintain public order and increase production in support of the war effort.

But it was far from clear how fast or how effectively the new measures might bolster Russia's military position on the ground, and what effect they would have on public opinion.

The Russian-installed acting governor of occupied Kherson, Vladimir Saldo, confirmed that he would hand power to the military, according to Russian news agencies. But several Russian regions including Moscow that were named in parts of the decree said nothing would change for them.

Putin's order came on the day that Russian-installed officials in Kherson told civilians to leave some areas as soon as possible in anticipation of an imminent Ukrainian attack.

Ukrainian presidential adviser Mykhailo Podolyak said on Twitter: "This does not change anything for Ukraine: we continue the liberation and de-occupation of our territories."

URGENT MEASURES

Ukrainian gains have forced Putin into a series of escalatory steps within the past month: the unpopular call-up of hundreds of thousands of extra troops, the unilateral annexation of the four Ukrainian regions - condemned as illegal by an overwhelming majority of nations at the U.N. General Assembly - and a threat to resort to nuclear weapons to defend what Russia sees as its own lands.

After months of assurances from the Kremlin that the campaign was going according to plan, the increasingly urgent measures have brought the reality of the war much closer to home for many ordinary Russians.

The failings of the military and the chaotic state of the mobilisation - which prompted hundreds of thousands of men to flee abroad - have drawn unprecedented criticism even from Putin allies.

Some regions have resorted to public appeals to provide newly mobilised soldiers with basic equipment to head to the front - a problem implicitly acknowledged by Putin.

"Our soldiers, no matter what tasks they perform, must be provided with everything they need. This applies to the equipment of barracks and places of deployment, living conditions, kit and gear, food and medical care," he said.

"We have every opportunity to resolve all the issues that arise here - and they do exist - at a modern level that is worthy of our country."

He said the steps he was ordering would increase the stability of the economy and industry and boost production in support of the military effort.

"We are working on solving very complex, large-scale tasks to ensure a reliable future for Russia, the future of our people," he said.

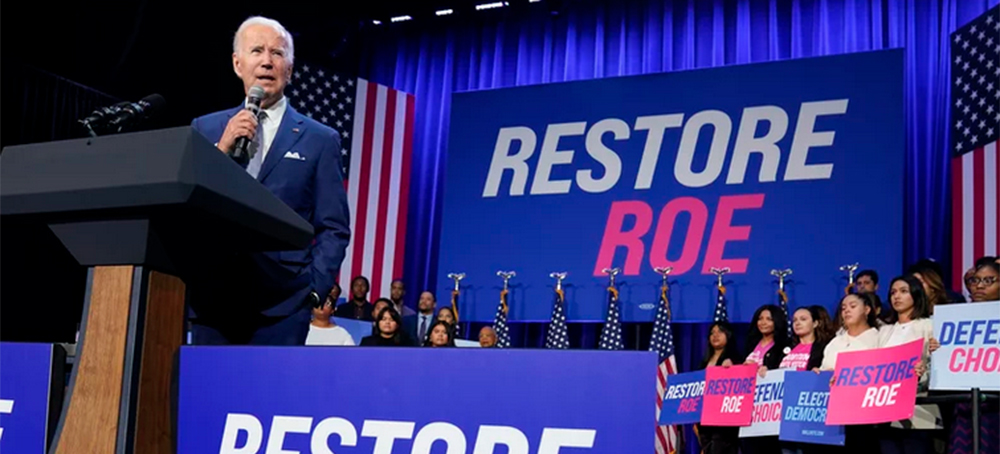

President Joe Biden speaks about abortion access during a Democratic National Committee event at the Howard Theatre in Washington, D.C., on Oct. 18. (photo: Evan Vucci/AP)

President Joe Biden speaks about abortion access during a Democratic National Committee event at the Howard Theatre in Washington, D.C., on Oct. 18. (photo: Evan Vucci/AP)

Biden doubled down on abortion rights as a voting issue for Democrats this November during a speech at a Democratic National Committee event in Washington, D.C.

"We're only 22 days away from the most consequential moment in our history in my view, in recent history at least — an election where the choice and the stakes are crystal clear, especially when it comes to the right to choose," Biden said Tuesday.

"Right now, we're short a handful of votes. If you care about the right to choose then you got to vote," he said. "That's why these midterm elections are so critical to elect more Democratic senators in the United States Senate and more Democrats to keep control the House of Representatives."

Since most legislation requires a 60-vote threshold to advance in the Senate due to the filibuster rule, Democrats would need to abolish the filibuster, which could allow the law to pass with a simple majority vote.

Yet Democrats currently lack the 50 votes in the Senate needed to remove the filibuster, with Democratic Sens. Joe Manchin and Krysten Sinema both expressing opposition to ending the procedure. This November, Democrats would need to elect at least two more candidates to the Senate who are willing to vote in support of ending the filibuster.

Biden said if such a bill to codify abortion protections is passed, he will sign it in January, the 50th anniversary of the Roe v. Wade decision.

Currently, Democrats hold an even 50 votes there, and control is likely to be decided in just a few races, with the House also facing slim margins.

The House previously passed a bill that would protect the right to abortion, but the vote in both chambers was largely symbolic because the Senate did not have enough support to pass it. Even Pennsylvania Democrat Bob Casey, who has previously voted for abortion restrictions, voted against the symbolic measure.

Then there is the threat of GOP efforts should Republicans win more seats. Sen. Lindsey Graham introduced a bill that would have created federal restrictions on abortion, a measure Biden said he would veto if passed.

Voters are weighing abortion rights as a top issue

Abortion rights emerged as a main campaign talking point for Democrats following the Supreme Court's reversal of the landmark Roe v. Wade decision, which prompted many states to enact abortion-restricting laws.

Although inflation has continued to be the top issue for both voters and Republican candidates, abortion rights have emerged as a top issue for voters as well.

It has been particularly energizing for younger voters, whose voter registration numbers increased following the Supreme Court's decision.

In his Tuesday speech, Biden specifically called out to younger voters who may have voted for the first time during the 2020 election.

"In 2020 you voted and delivered the change you wanted to see in the world. In 2022, you need to exercise the power to vote again for the future of our nation and the future of your generation," Biden said.

READ MORE Voting on the border. (photo: Intelligencer/Getty Images)

Voting on the border. (photo: Intelligencer/Getty Images)

Flores is a MAGA acolyte who once suggested the January 6 attack was “caused by infiltrators” and has frequently referenced QAnon on her Twitter account. Her election represented the culmination of a years-long trend: Despite Donald Trump’s endlessly hostile rhetoric toward Mexican immigrants — from labeling them “rapists” in his 2016 campaign kickoff to reportedly calling for them to be shot on sight in 2019 — he made major gains across South Texas in the 2020 election, cutting the margin by which Joe Biden won the state’s border counties to 17 percentage points, half of the 33-point margin Hillary Clinton posted in 2016. “When you take voters for granted like national Democrats have done in South Texas for 40 years, there are consequences to pay,” Congressman Filemón Vela told the Texas Tribune at the time; two years later, his retirement opened the door for Flores’s ascension.

Trump’s surprising performance in South Texas had major down-ballot implications, including helping Republican Tony Gonzales win the massive congressional district that covers most of Texas’s border with Mexico, from the outskirts of El Paso to Del Rio. When I spoke to him in August, Gonzales chalked up his success to the profile he cut, which is distinct from those of more famous, big-city Latino politicians like the Castro brothers. “It helped that I was Hispanic in a Hispanic district, and I’m Catholic in a district that has conservative views. I’m a 20-year military veteran,” Gonzales said. “The No. 1 thing is just showing up and being genuine. I didn’t show up two weeks before the election speaking broken Spanish and run some ads on Telemundo and call it a day. I showed up early and I showed up often. I put 70,000 miles on my pickup truck.”

As both parties gear up for the November midterms, Republicans feel they can make further inroads in the largely Mexican American communities that line the southern border, while Democrats are seeking to reconnect with a voting bloc that may prove decisive to control of Congress, given that some of the most competitive House races in the country are taking place in the Southwest. As co-chair of the RNC’s new Hispanic Leadership Trust, Gonzales has been campaigning alongside both Flores and Juan Ciscomani, a former aide to Arizona governor Doug Ducey who is running for the district that encompasses the state’s southeastern corner. At the same time, one of the region’s most vulnerable Republican incumbents, New Mexico’s Yvette Herrell, faces a difficult fight against Gabriel Vasquez, a former city councilor in the college town of Las Cruces who represents a different path for the future of Hispanic politics along the southern border. “Coming from a working-class, immigrant family, I think that resonates with folks,” Vasquez says. “We thrive in relationship and community building.”

As I traveled across the region this summer, two competing visions of the borderland’s future were coming into focus — visions that map more neatly on to the polarized landscape of national politics than Democrats would like to admit, given that the region is full of Latino voters whom they recently considered to be a bank of safe votes. On one side are progressives promising to bring improved access to health care, education, and water to impoverished rural communities, even as the party itself grows ever more urban and liberal on issues like green energy and criminal justice. On the other is an ascendant brand of MAGA conservatism that expresses hostility to new immigrants while channeling the deep patriotism of established Mexican Americans, those who share the same resentments, if not the skin color, of the disillusioned white working-class voters of the Rust Belt and other economically depressed regions where Trump’s movement first gained purchase. As Laura Gómez, a law professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, put it when I reached her at her home in Albuquerque, “From the Trump years on, the nation has gone through tremendous changes. Politically, ideologically. Why wouldn’t we expect that Latinos have also been changing?”

Much of the contemporary political culture of the borderlands is rooted in the profound transformation of the region that began in the 1990s with the passage of NAFTA, which paved the way for hundreds of billions of goods to move freely between the United States and Mexico, and accelerated after the 9/11 attacks, which ushered in an unprecedented tightening of the border for everyday people. More than $1 trillion was spent on the Department of Homeland Security between 2002, when the agency was founded, and 2020, a period that also saw its workforce balloon to 240,000. While the local economies that stretch across the 2,000 miles of the border may shade from agriculture in California to oil and gas in New Mexico to logistics in Texas, the presence of the military and federal law enforcement is universal.

Despite the massive cash infusion of the past three decades, generational poverty remains a fact of life in the borderlands. The low percentage of South Texans with health insurance translated to a COVID death rate that was twice as high as the rest of the state, while 135,000 New Mexicans remain sequestered in so-called colonias, rural communities that lack paved roads, electricity, and running water. For the region’s entrenched Mexican American communities, where “the border crossed us” is still a common refrain, federal jobs are typically the best gig available. Today, more than half of all Border Patrol officers are Hispanic; when I crossed the Bridge of the Americas into El Paso in June, the agents manning the port of agency were chatting with each other in the same Spanish accent I’d just heard on the streets of Juárez.

While national observers fixated on Mayra Flores’s extremist statements, voters in South Texas found plenty to connect with in her life story. Born in Tamaulipas, Flores came to the United States as a child and spent her summers as a teenager picking cotton in the Texas panhandle. Her upward mobility spoke to the bootstrapping mentality embraced by so many immigrants, while her marriage to one of the more than 3,000 Border Patrol agents stationed in the Rio Grande Valley signaled her commitment to the agency that is thought of as gateway to the middle class for many poor families. As one advertisement that ran on Flores’s behalf a few weeks before the special election put it: “She’s one of us.”

The district was considered Democratic territory, but Republicans flooded the race with money, helping Flores outraise her Democratic opponent 16-to-1. Mario Muñoz chairs the Democratic party of Kleberg County, best known as the home of the 825,000-acre King Ranch, the largest cattle operation in the United States. Although outreach to a rural county like Kleberg would seem to be less of a priority than motivating voters in populous Brownsville, Muñoz says that during the special election, busloads of Republican activists were coming into town from North Texas “to bust doors open, meet with people, spread the message on their terms.” The rush to boost Flores’s candidacy didn’t come out of nowhere. “They’ve been making headway,” Muñoz says. “The Republican party, at the state and federal level, has been inserting and funding headquarters in regions like ours.”

Despite the shock of Flores’s victory, national Democrats were quick to dismiss the result as an aberration. Not only did the odd timing of the election lead to miniscule turnout — fewer than 29,000 people voted in a district with a population of over 711,000 — but decennial redistricting means that Texas’s 34th district will be markedly different in November, with more of the urbanized Rio Grande Valley packed into it in order to free up the hill country near San Antonio to shore up conservative incumbents elsewhere.

Congressman Vicente Gonzalez, who currently represents the district next door to the 34 but is shifting into it to challenge Flores this fall, believes the record of the Biden administration should be enough to win back voters who may have drifted away from the party in recent years. “We want to have profound conversations about what we’ve accomplished,” he says, pointing to the $68 million included in last year’s infrastructure bill to deepen the port of Brownsville, a project which, once completed, will allow the facility to accommodate larger ships than anywhere else in the Gulf of Mexico.

Most independent prognosticators now peg Flores as an underdog. But that doesn’t mean her victory this summer was pointless. When I spoke to him in July, Gonzalez seemed almost perplexed about why the GOP invested so heavily in a district it seemed destined to control for such a short time. “I asked one of my Republican colleagues I’m close with, ‘Why would y’all do that? If the district changes from a D+4 to a D+16?’ And he didn’t bat an eye, he said, ‘Because we get to own the message of a Latina Republican for six months.’”

While the competition for TX-34 may be more symbolic than determinative, many other districts along the border could go either way in November. The sense of all-out political battle is most palpable in purpling Arizona, where the Republican who has emerged to contest the region that stretches from Tucson’s east side to the southern border is Juan Ciscomani. With no record as an elected official to fall back on, Ciscomani is running a campaign of personality that centers on the immigration of his parents to the United States and prominently features images of his wife and six children. While Democrat Ann Kirkpatrick has represented the area since 2013, the combination of her retirement and the reshaping of the district to trade the arty enclave of Bisbee for rural Graham and Greenlee counties has created a prime pick-up opportunity for Republicans.

Although Flores and Ciscomani have been equally explicit in invoking their humble upbringings in their campaigns, Ciscomani’s spin on the theme is tailored less to suggest “he’s one of us” than “he’s an immigrant who made good” — a reasonable distinction, given that Arizona’s sixth district is only 17 percent Hispanic compared to the 85 percent Hispanic TX-34. After being introduced by his daughter Zoe at the event celebrating his primary victory in August, Ciscomani reflected, “Now the story of this kid from an immigrant family, who grew up in East Tucson, graduated from Rincon High School, Pima Community College, and then the U of A, also includes to be the Republican nominee for the Sixth Congressional District in the state of Arizona. The American Dream is alive.” (Campaign staff for both Flores and Ciscomani declined to make their candidates available for an interview.)

The contrast between Ciscomani’s resume and that of his Democratic challenger is stark. Kirsten Engel, an environmental law professor at the University of Arizona, first ran for office in 2016, inspired, she says, by the lack of state resources devoted to her daughter’s elementary school in Tucson. She went on to serve in both the Arizona house and the senate, where education and water security have been her signature concerns.

Engel’s appeal, which is a natural fit in an overgrown college town like Tucson, is less obvious somewhere like Sierra Vista, a city of 45,000 where nearly every resident is connected to either the adjacent Fort Huachuca Army garrison or the local offices of the Border Patrol, DHS, DEA, or FBI.

Mark Rodriguez, who joined the City Council last year, grew up in San Antonio and spent nearly two decades in the Army before landing in Sierra Vista in 2014 and deciding to stay, partially because of the magnificent landscape that surrounds the city, including the dramatic Huachuca Mountains, which the torrential thunderstorms of this year’s August monsoon had painted a vibrant shade of green. Rodriguez says that an unexpected dimension of the job is addressing the unique public-safety concerns that tend to crop up when you live 12 miles from the border. “Right now, the cartels are recruiting teenagers on Snapchat,” he says. “They’re offering them $2,000 for each person they give a ride to.”

Both here and in more rural corners of the district, Engel says her background in environmental law has made it possible to bridge the gap between the big city and the borderlands. “Just last Friday we were at the farm bureau dinner here in Cochise County,” Engel said when I met with her in Sierra Vista. There, a pepper farmer expressed his anxiety about the dropping water table on his property, a microcosm of the regional aridification being driven by the climate crisis. “People are actually losing their homes and businesses,” Engel says. “There’s nothing less valuable in the desert than a farm without water. Our lack of management, its ruining lives, its ruining families. This is real; it’s going on right now.”

Just before our conversation, Engel made an appearance at a coffee hour organized by Elisabeth Tyndall, the chair of the Cochise County Democratic Party. The party office is located in a Spanish tile-roofed strip mall, right across Fry Boulevard from the local Republican headquarters, where a handwritten sign was advertising a screening of Dinesh D’Souza’s election conspiracy movie, 2000 Mules. Engel led off by sharing the results of a poll commissioned by her campaign that found her leading Ciscomani by two points, news that was greeted with applause by the 20 volunteers in attendance. That edge, she said, seemed rooted in the overturning of Roe v. Wade, as some 60 percent of district voters believed abortion should be legal. Engel soon turned to the opposition. “Here in Arizona, the Republican Party has nominated the most extreme slate of characters imaginable, from Kari Lake to Blake Masters to Mark Finchem.” At the mention of Finchem, a self-professed member of the Oath Keepers who is running for secretary of State, the crowd broke out into a mix of befuddled laughs and hisses of disdain.

The worst Engel could muster for her actual opponent was that he “has not disavowed this slate at all.” The problem posed by the cipherlike Ciscomani was underscored when an eager canvasser raised her hand. “We need to know how to come at your opponent,” she said. “He’s very smooth.” The volunteer’s question went unanswered, but I posed it again when I spoke to Engel afterward. Though she declined to discuss Ciscomani specifically, Engel was frank in criticizing what she sees as the current conservative playbook: “I think the Republicans are adopting a strategy where they have to be careful about making sure the candidates they are presenting really have a track record in representing the community that they’re going to serve, they’re not just checking off some boxes in terms of diversity.” Her point is well taken, even if I couldn’t help but note how it echoed the attacks Democrats typically sustain for recruiting minority candidates and officials, from Vice-President Kamala Harris to Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor.

While some Republicans may indeed be more interested in playing identity politics than building lasting partnerships with borderland communities, Democrats underrate the regional appeal of conservatism at their own peril. From 2015 to 2021, Will Hurd was the congressman for the sprawling border district now represented by Tony Gonzales. “In 2020, the number of Latinos voting for Republicans was not a surprise,” he asserts. Citing the high proportion of people across the borderlands who work in law enforcement and the concentration of oil and natural gas production in the Permian Basin that bridges West Texas and eastern New Mexico, Hurd believes it was the progressive embrace of criminal-justice reform and green energy that motivated many in the region to vote for Trump. “What was happening in 2020 was these initiatives within the Democratic party were impacting the livelihoods of people that lived along the border, that was the significant difference.”

This election cycle, those issues are again at the fore of the race for New Mexico’s second district, where the Republican incumbent, the former realtor Yvette Herrell, is engaged in a daunting fight for reelection. In New Mexico, unlike Texas or Arizona, redistricting was controlled by Democrats who passed an ambitious map designed to advantage progressives in all three of the state’s congressional districts by inserting the South Valley of Albuquerque, which is 80 percent Hispanic, into a rural district that previously constituted the southern two-thirds of the state. To meet the challenge of campaigning in the South Valley, Herrell has emphasized addressing the neighborhood’s alarmingly high crime rate. To boost her, the RNC recently opened a “Hispanic Community Center” next door to a paletería on Central Avenue, Albuquerque’s main artery. “It doesn’t matter what race, what culture, whatever you celebrate,” Herrell said when she appeared at the facility’s grand opening. “Let’s just remind each other that we should identify as Americans first” — a sly adaptation of Trump’s “America First” credo to a multicultural context. (Herrell’s campaign declined an interview request.)

Herrell’s challenger in the race is Gabriel Vasquez, a former city councilman in Las Cruces, the state’s second-largest city. Like Juan Ciscomani, Vasquez is a first-generation immigrant and was quick to invoke the American Dream when I spoke to him in July. But rather than casting himself as a golden boy, Vasquez seems more focused on how his story can help him connect with voters across southern New Mexico: “When I go talk to folks in Chaparral, or Sunland Park, or the South Valley, I share the same message of where I came from, how I got here, of the values that I’ll bring to Congress.” Vasquez’s greatest challenge will be making inroads in the southeastern corner of the state, where the oil and gas industry has boomed in recent years. His outreach to the region is centered on the low-wage workers who populate the boomtown of Hobbs, where the population jumped nearly 20 percent over the last decade as the state’s annual production of crude oil more than quadrupled.

Eduviges Hernandez is an organizer with the Hobbs chapter of the statewide advocacy group Somos Un Pueblo Unido. She says the city’s fast-growing Hispanic community is in dire need of basic health-care services, from doctors to a rehabilitation clinic. “Right now, when people need those things, they have to travel to Lubbock, Texas” — over 100 miles away. Education is also an area of concern, and Somos is coordinating most of its current voter outreach around a ballot question that would allocate $150 million to day cares and preschools throughout New Mexico. When I asked her about the congressional race, Hernández said, “Yvette Herrell, she doesn’t want to talk to us. We’re going to support Gabriel Vasquez because he’s one of our people. He wants to meet with us, to see what the plan for the community is going to be.”

Rather than engage local organizers such as Hernandez, Herrell’s campaign has focused on a pitched rhetorical battle with the Democrats who control both the state and federal governments, largely centered on Albuquerque’s surging violent crime (as the AP put it, the city’s homicide rate in 2021 ended up “shattering” the previous record by 46 percent). Herrell has called on the Department of Justice to drop the consent decree — a slate of court-ordered reforms that includes specific training programs for uniform officers and community-engagement measures — it has had in place with the Albuquerque Police Department since 2014, when the department was killing people at a rate eight times higher than the NYPD. It’s an issue that resonates throughout the state: In a September poll, the Albuquerque Journal found that 82 percent of likely voters across New Mexico describe violence as a serious issue, far more than are worried about education or the economy. “Our state’s largest city is worse-off following the enactment of this decree,” Herrell wrote in a letter to Attorney General Merrick Garland. “It is long past time that Albuquerque and our police department be allowed to govern themselves.”

However enticing law-and-order appeals may seem, it’s unclear how much ground Republicans can gain if they, like their counterparts elsewhere, remain trapped in an echo chamber of election denial. In June, officials in New Mexico’s Otero County — including Couy Griffin, the co-founder of a group called Cowboys for Trump — made national headlines when they refused to certify the results of a local primary election because it was conducted on Dominion voting machines. Two days later, I drove to the county seat of Alamogordo to meet with John Block, a conservative activist who had just defeated the region’s incumbent representative in the state house by 46 votes but now agreed that there was reason to be skeptical of the results. “If we have to do a hand count of the ballots, then I’m all for it,” Block said. “I do think their concerns about those machines are warranted, because there is wide reporting about how they can connect to the internet.”

Block and I spoke on the patio of a coffee shop in the foothills of the Sacramento Mountains, allowing us a grand view of the city that encompassed nearby Holloman Air Force Base and, beyond it, the glittering White Sands Missile Range, where the first nuclear weapon was tested in 1945. Though it has fewer than 32,000 residents, Alamogordo is an important proving ground for the state’s Republican Party — Yvette Herrell once held the seat in the state house that Block will likely take over in November. Although he has lived in Alamogordo for several years, Block is the scion of one of the old Hispaño families of northern New Mexico that claims Spanish colonial linage; both his grandfather and cousin once held elected office as Democrats. Block says he turned away from the party after the Affordable Care Act was passed and was so enraptured with Donald Trump that he showed up to the “Stop the Steal” rally on January 6, though he was wise enough to stay out of the Capitol itself.

“I think the Democrat Party has been very good at messaging themselves as being open-minded,” Block says. “That’s why I ran. We need to be better at messaging, at packaging what we have to sell to these voters … Hispanics go to church, they’re faithful people. And then immigration, they see there’s a problem with people flooding into this country and when they get here there’s no real job prospects for them because they don’t have the skills to be successful.” Ultimately, Block believes, “Hispanics are very conservative people. It just takes talking about the issues to push them in the right direction.”

The notion that Latinos are a bloc of “natural conservatives” dates back to Ronald Reagan, who once told the San Antonio advertising executive Lionel Sosa, “Hispanics are already Republican, they just don’t know it.” George W. Bush came the closest to proving his predecessor right, winning more than 40 percent of the Hispanic vote in a 2004 election that saw him eke out a victory in New Mexico by fewer than 6,000 votes.

“If we’re talking about Catholicism, why is it that we don’t assume that all white Catholics are conservative?” ask Laura Gómez, the UCLA professor whose most recent book, Inventing Latinos, traces how the extensive Latin American diaspora came to be thought of as a singular demographic. “There’s a great diversity among Catholics, and that exists among Mexican American Catholics, too.” To her point, both Vicente Gonzalez and Gabriel Vasquez identify as Catholic. “I’m a Democrat and I’m a Catholic and I also have an American flag in front of my home,” Gonzalez says. “The idea that we’ve allowed the Republican Party to own God and the Bible and patriotism is, I think, is just ridiculous.”

Patriotic appeals to Hispanics are particularly effective along the border because many Mexican Americans feel compelled to distance themselves from undocumented immigrants — which is to say, those who didn’t immigrate the “right” way. This is particularly true of people who hope to work in law enforcement or serve in the military. “You’re going to want to differentiate yourself from that group” of the undocumented, Gómez says. “Especially if you did immigrate or your parents immigrated.”

Although there are certainly signs that Republicans are more interested in stoking the narrative of Mexican Americans flocking to conservatism than they are in addressing the iniquities of the borderlands, it’s impossible to deny that the crosscurrents of the region are exposing the same bitter divisions that exist across the United States. For Republicans, calcifying that schism into a durable component of their electoral coalition may be as simple as canning the discriminatory rhetoric that characterized the Trump years and elevating more candidates, like Tony Gonzales, who pair “America first” appeals with traditional grassroots politicking.

Matching and then sustaining the level of support George W. Bush once enjoyed with Hispanics is all it would take for conservatives to put a stranglehold on Washington. For Democrats to prevail, each candidate will have to abandon the hackneyed ideas of what Hispanics or even Mexican Americans want and attend to the communities they hope to represent on a granular level. As Vicente Gonzalez put it: “You talk to a white American in West Texas, a white American in Austin, a white American in New York City, in Miami, in Los Angeles — you’re going to have five different stories. My Mexican American friends from L.A. and I are different. Even though we enjoy each other’s company and a common culture, our American experience has been very different. We’re as diverse as everyone else.”

READ MORE Several people challenging their status on government watch and no-fly lists say they have gotten delisted as their court cases gained traction. (photo iStock)

Several people challenging their status on government watch and no-fly lists say they have gotten delisted as their court cases gained traction. (photo iStock)

Those challenging the constitutionality of the ‘No-Fly List’ and Terrorist Screening Database say that when they sue, they get removed, making it impossible to have their concerns heard in court

Nine years of such troubles, he came to believe, all arose from his placement on a list of suspected terrorists banned from air travel in the United States. Long, a veteran and Muslim convert, filed a lawsuit in federal court in Alexandria, Va. But as his lawsuit started moving forward in 2019, the government told him he had been removed from the list.

Advocates say the reversal is part of a pattern from the government to evade scrutiny of the Terrorist Screening Database, a secret, FBI-maintained list of known or suspected terrorists subject to heightened security screening at borders, and of the smaller No Fly List of those barred from U.S. airspace.

Hundreds of thousands of people have been placed on the lists since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. For years, civil liberties groups have challenged the process of determining who is on the two lists as unconstitutional but say they’re often hampered by the government’s tactics.

“The Government removes people from their secret lists only when they fear that a court might impose restraint on their lawlessness,” said Gadeir Abbas, an attorney with the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) litigating Long’s case. “If the FBI has its way, delisting a person will become a kind of cheat code the federal government can use to deny people their day in court.”

The group has eight such examples, he said. The latest involves Abdulkadir Nur, a Somali-born U.S. citizen who lives in Virginia and says in court filings he had been subjected to extensive, intrusive searches at U.S. airports since 2008. That year, Nur was part of a United Nations relief convoy in Somalia that local insurgents raided; he was questioned in the subsequent investigation but never accused of wrongdoing.

Nur got no confirmation that he was ever on the terrorism watch list or taken off it. His attorneys say they can infer both from the scrutiny he consistently received at airports until this month, when he did not get searched or interrogated for the first time in 12 years.

“The Government ... merely has stopped violating the law against Nur, and only to wrangle out of a lawsuit it cannot win,” his attorneys wrote.

A spokeswoman for the Justice Department did not respond to a request for comment.

CAIR is arguing that Nur’s lawsuit should continue despite the apparent concession. But earlier this year, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit ruled that Long’s challenge to the No Fly List was moot because the government had taken him off. He can keep fighting his placement on the broader watch list.

Because of a 2015 ruling in another federal court, Long was able to learn that he was on the No Fly List. (Placement on the broader watch list remains a mystery.) He was told by the Department of Homeland Security that he was on the list because he had “participated in training that may make you a threat to U.S. national security,” and that an arrest in Turkey in 2015 was also “of concern to the U.S. Government,” according to court records.

Long says his only military training came from the U.S. government and that his arrest on a vacation in Turkey was a direct result of his placement on the No Fly List. Long served in the Air Force from 1987 to 1998. While stationed in Turkey, he converted to Islam and decided he could not be responsible for civilian deaths. Denied conscientious objector status, he ended up leaving the military with an “other than honorable discharge.” He stayed in the Middle East and became an English teacher.

The DHS letter said the government “withheld certain information” about Long’s placement because of “national security concerns.”

But in late 2020, when the case was before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit, he was informed he had been removed from the No Fly List and would not be put back on, absent new information; the Department of Justice made a similar guarantee in court.

Long’s attorneys argued that his removal from the list shows “the Government is willing to place and maintain people on these lists even when they pose no national security threat.”

A panel of 4th Circuit judges said they could not agree.

“While the government doesn’t concede constitutional error, we assume it removed Long from the list because, as he contends, he doesn’t belong on it,” the court ruled in June. “To say otherwise would be to suggest the government risked national security simply to moot a lawsuit. This we decline to do.”

The 9th Circuit ruled differently a month earlier, keeping alive a lawsuit from a man named Yonas Fikre, who alleges he spent years on the list for refusing to become an informant, even after he was removed.

“The government has not explained why it added him to the No Fly List in the first place and why, years later, it spontaneously took him off of it,” that court wrote in 2018. “Nothing prevents the government from putting him back on the list.”

The government subsequently issued a declaration similar to the one given to Long, saying Fikre would not go back on the list based on “currently available information.” But the 9th Circuit said that was not enough, because the government “has not ‘repudiated the decision’ to place Fikre on the list, nor has it identified any criteria for inclusion on the list that may have changed.” Without such disavowal, the court said in a unanimous decision this May, “Fikre remained stigmatized ‘as a known or suspected terrorist.’”

That was a “very powerful opinion,” said Jeffrey Kahn, a former Justice Department attorney who has studied the terrorism watch list as a law professor at Southern Methodist University. The goal of the government attorneys in these cases is “to end the case” before trial, he said, and just taking someone off the list “is an easy way to kill the lawsuit.” The government can track people in other ways and potentially put them back on the lists.

The same U.S. judge in the Eastern District of Virginia presiding over Nur’s case, Anthony J. Trenga, ruled in 2019 that the watch list system violates due process rights.

“The risk of erroneous deprivation of ... travel-related and reputational liberty interests is high,’” the George W. Bush appointee wrote in response to a suit filed by 23 Muslim Americans.

He noted that for an agency to nominate a name for the list requires only “reasonable suspicion” that someone is a “suspected terrorist,” which does not require any evidence of involvement or interest in criminal activity. Ninety-nine percent of nominations are accepted by the Terrorist Screening Center.

According to court filings, as of 2019 there are roughly 1.1 million people on the broader watch list, of which 81,000 are barred from flying.

“If there were that many terrorists in the world, we would be getting attacked all day long,” said Javed Ali, former senior director for counterterrorism at the National Security Council. “That’s not the way to use a tool like this — if people are in there in error, they should not be there in perpetuity.”

He suggested a court similar to the one that oversees secret surveillance orders could evaluate Americans’ placement on these lists.

The 4th Circuit overturned Trenga’s decision last year, saying “the delays and burdens experienced by plaintiffs at the border and in airports, although regrettable, do not mandate a complete overhaul.”

READ MORE Across Haiti, almost five million are struggling with malnutrition. (photo: EPA)

Across Haiti, almost five million are struggling with malnutrition. (photo: EPA)

The United Nations is warning that hunger in one of Haiti's biggest slums is at catastrophic levels, as gang violence and economic crises push the country to "breaking point".

Across Haiti, almost five million are struggling with malnutrition.

"Haiti is facing a humanitarian catastrophe," a top UN official said.

"The severity and the extent of food insecurity in Haiti is getting worse," Jean-Martin Bauer, the Haiti country director for the UN's World Food Programme added.

The poorest nation in the Americas is suffering acute political, economic, health and security crises which have fuelled a rise in violence and paralysed the country.

Powerful gangs have blocked Haiti's main fuel terminal, crippling its basic water and food supplies.

In the Cité Soleil neighbourhood, the UN said levels of food insecurity had reached the highest level on its classification system - Phase 5 - meaning residents have dangerously little access to food and could be facing starvation.

Mr Bauer said Haitians "have gone through the gauntlet".

Anger at the government's handling of the country's multiple crises have boiled over into anti-government protests. These have escalated to looting with at least one woman reportedly killed in clashes.

On Tuesday, the World Health Organisation said there had been 16 cholera deaths and 32 confirmed cases, three years after an epidemic of the water-borne disease killed 10,000 people.

Another UN official said 100,000 children under the age of five were severely malnourished and are especially vulnerable to cholera.

Prime Minister Ariel Henry has asked for foreign military help, but the call has been criticised by some Haitians who see it as foreign interference.

The UN has since called for the immediate deployment of a special international armed force to Haiti, but it is not yet clear which countries would provide the members of such a force and what its task would be.

Gangs have taken control of key highways and Varreux, Haiti's largest fuel terminal. With food and fuel deliveries suspended as a result, more and more Haitians are going hungry.

Several warehouses run by aid organisations have also been looted, resulting in the most vulnerable going without food and drinking water.

Haiti is one of the poorest countries in the world and has suffered a number of recent crises, most notably the assassination of its president, Jovenel Moïse, in July 2021 and a massive earthquake that left more than 2,200 people dead just a month later.

READ MORE Plastic in the ocean. (photo: Grist/Getty Images)

Plastic in the ocean. (photo: Grist/Getty Images)

Researchers worry that microplastics may be messing with an important carbon sequestration process.

Microplastics — tiny plastic fragments that are less than 5 millimeters in diameter, a little less than one-third the size of a dime — have become ubiquitous in the environment. They form when larger plastic items like water bottles, grocery bags, and food wrappers are exposed to the elements, chipping into smaller and smaller pieces as they degrade. Smaller plastic fragments can get down into the nano territory, spanning just 0.000001 millimeter — a tiny fraction of the width of a human hair.

These plastic particles do many of the same bad things that larger plastic items do: mar the land and sea, leach toxic chemicals into the food chain. But scientists are increasingly worried about their potential impact on the global climate system. Not only do microplastics release potent greenhouse gases as they break down, but they also may be inhibiting one of the world’s most important carbon sinks, preventing planet-warming carbon molecules from being locked away in the seafloor.

Matt Simon, a science journalist for Wired, details the danger in his forthcoming book on microplastics, A Poison Like No Other. He told Grist that it’s still early days for some of this research but that the problem could be “hugely important going forward.”

To understand the potential magnitude, you first have to understand an ocean phenomenon called the “biological carbon pump.” This process — which involves a complex network of physical, chemical, and biological factors — sequesters up to 12 billion metric tons of carbon at the bottom of the ocean each year, potentially locking away one-third of humanity’s annual emissions. Without this vital system, scientists estimate that atmospheric CO2 concentrations, which recently hit a new record high of 421 parts per million, could be up to 250 parts per million higher.

“The biological carbon pump helps to keep the planet healthy,” said Clara Manno, a marine ecologist at the British Antarctic Survey. “It helps the mitigation of climate change.”

The pump works like this: First, carbon dioxide from the atmosphere dissolves into water at the surface of the ocean. Using photosynthesis, tiny marine algae called phytoplankton then absorb that carbon into their bodies before passing it onto small ocean critters — zooplankton — that eat them. In a final step, zooplankton excrete the carbon as part of “fecal pellets” that sink down the water column. Once these carbon-containing pellets reach the ocean floor, the carbon can be remineralized into rocks — preventing it from escaping back into the atmosphere.

So where do microplastics come in? Unfortunately, at every step of the process.

Perhaps most concerning to scientists is the way microplastics may be affecting that final stage, the sinking of zooplankton poop to the bottom of the seafloor. Once ingested, microplastics get incorporated into zooplankton poop and can cause fecal pellets to sink “way, way more slowly,” said Matthew Cole, a senior marine ecologist and ecotoxicologist at the Plymouth Marine Laboratory in the U.K. In a 2016 paper he published in Environmental Science … Technology, he documented a 2.25-fold reduction in the sinking rate for the fecal pellets of zooplankton that had been exposed to microplastics. Other research has shown that plastic-contaminated krill fecal pellets can sink about half as quickly as their purer counterparts.

This reduced sinking rate is a result of microplastics’ buoyancy — especially those made of low-density polymers like polyethylene, the stuff used in grocery bags and likely the most common polymer in the surface ocean. Slower sinking rates mean fecal pellets may spend up to two or even three days more than usual drifting through the water column, presenting more opportunities to be intercepted.

“They’re more likely to break apart, they’re more likely to be eaten by other animals,” Cole said, making it less likely that the carbon will reach the seafloor and become permanently sequestered.

There are other worries too, about the way microplastics can affect phytoplankton and zooplankton health — potentially compounding the stresses already posed by rising carbon dioxide concentrations, which are making the oceans warmer and more acidic, and are contributing to the expansion of oxygen-depleted “dead zones.” High concentrations of microplastics in water are toxic to phytoplankton, and lab experiments have shown they can cause up to a 45 percent reduction in some species’ growth. Cole’s experiments on copepods, a common kind of zooplankton, have shown that ingested microplastics take up space in copepods’ guts, causing them to eat less real food, produce smaller eggs that are significantly less likely to hatch, and live shorter lives.

Researchers are still trying to come to grips with what all these laboratory observations could mean on a global scale. But the worry is that a planet-wide population of smaller, shorter-lived ocean algae and zooplankton may not be able to take up as much carbon as their ancestors — exacerbating the problems associated with buoyant fecal pellets.

“There is something there that we should worry about,” Manno said, stressing the need for more research. To that end, she’s working on a multiyear field study, with research expeditions planned for the microplastics-laden Mediterranean Sea and the moderately cleaner Southern Ocean. Manno said she’s hoping to collect real-world plastic and fecal pellet samples and get a better look at how microplastics interact with zooplankton in the open ocean.

The goal, Manno explained, is to quantify the decline in carbon sequestration related to microplastics and translate that into a dollar cost to society. “The ocean provides us this ecosystem service,” she said. “If something stresses these processes … this is a kind of social benefit that we cannot use anymore.”

If her hypothesis is correct — that microplastics are inhibiting the biological carbon pump — it will add even more weight to a growing recognition of plastic and microplastics as a major climate disrupter. Scientists already know that plastic production and incineration cause massive greenhouse gas emissions, and in A Poison Like No Other, Simon notes emerging research on the way microplastics release exponentially increasing amounts of planet-warming methane and ethylene as they break down.

“They continue emitting forever,” said Sarah-Jeanne Royer, the oceanographer and postdoctoral researcher at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography who is conducting that research.

To mitigate their damage to ecosystems and the climate, Royer called for policymakers to double down on removing microplastics from the ocean. But that’s a tall order. Despite some early-stage experiments involving plastic-eating mussels and bacteria, Simon said there are currently no viable, scalable ways to remove all the microplastics that have already accumulated in the environment.

“We have so much microplastic and nanoplastic in so many places on the planet — in the air and the land and the sea — that there’s just no way to pull it all out,” Simon said. “I wish there was a nice, happy solution like a magnet that you could drag through the environment and attract all the microplastics, but unfortunately that just doesn’t exist.”

Instead, he called for people to take steps to limit the release of microplastics into the environment — like by installing a filter on their washing machine — as well as government-mandated caps on plastic production. “We have to stop producing so much goddamn plastic,” he said. “It is out of control at this point.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.